Analyzing the Effectiveness of Water Reclamation Processes in Terms of Costs and Water Quality in Taiwan

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To analyze the operational cost of the reclaimed water treatment process in three different treatment processes in Taiwan.

- Examine the water quality of reclaimed water treatment plants in Taiwan.

- Scenario A: Sand filtration → ultra filtration (UF) → reverse osmosis (RO) disinfection

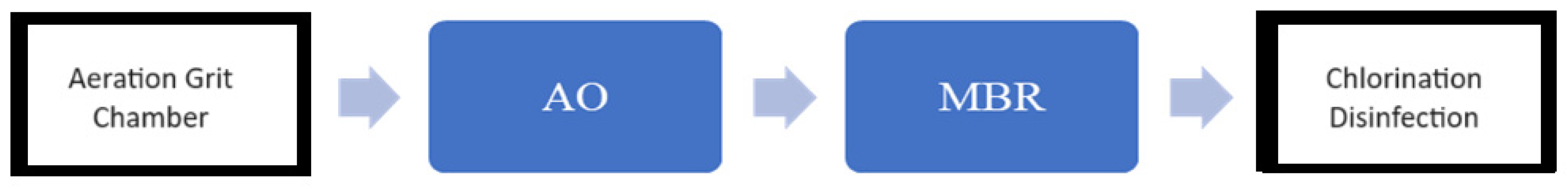

- Scenario B: Aeration and Grit Removal A/O membrane bioreactor (MBR) system disinfection

- Scenario C: Sand filtration disinfection

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting Scenario A

2.2. Setting Scenario B

2.3. Setting Scenario C

3. Economic Assumptions and Sensitivity Framework

3.1. Discounting and Capital Recovery

3.2. Escalation

3.3. Sensitivity Design

3.4. Summary

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Estimation of Operating Costs

4.1.1. Operating Cost Estimate for Scenario A

4.1.2. Operating Cost Estimate for Scenario B

4.1.3. Operating Cost Estimate for Scenario C

4.1.4. Summary of Costs for Scenarios A, B, and C

4.2. Comparison of the Quality of Recycled Water in Scenarios A, B, and C with Tap Water

4.2.1. Quality Standards

4.2.2. Suspended Solids (SS)

4.2.3. Ammonia Nitrogen

4.2.4. Turbidity

4.2.5. Total Hardness (CaCO3)

4.2.6. Total Organic Carbon (TOC)

4.2.7. Electrical Conductivity

4.3. Point-of-Use Pretreatment Costs in Scenarios A–C

4.4. Summary of Comparison in Scenarios A–C

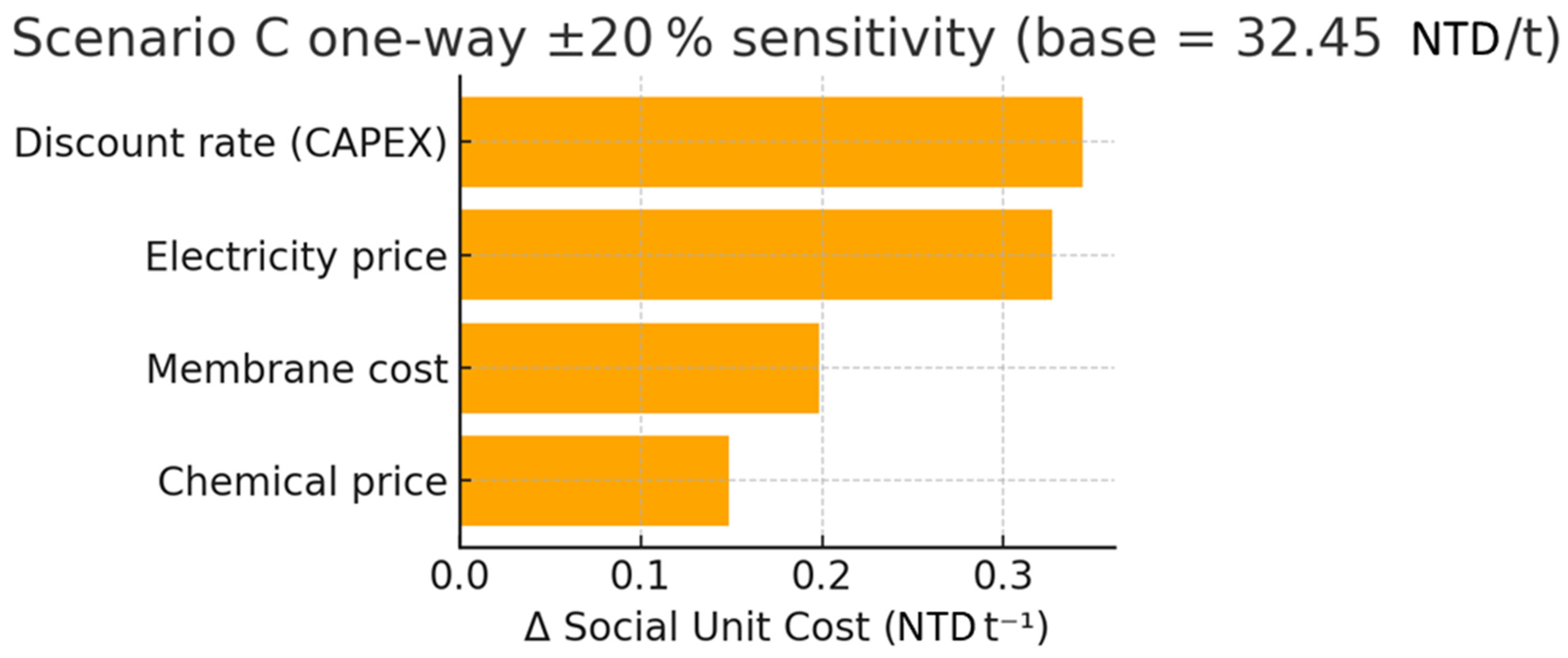

5. Sensitivity and Uncertainty Analysis

5.1. One-Way Sensitivity (Tornado Diagram)

- The discount rate (via CAPEX annualization) exerts the greatest leverage, shifting SUC by ±2.3 NT t−1 for a 20% change.

- The electricity tariff ranks second (±1.0 NT t−1), followed by membrane replacement cost of membrane replacement and the chemical price.

- The same exercise for scenarios B and C returns identical parameter ordering, confirming that capital discounting and power tariffs dominate cost uncertainty across all treatment trains.

5.2. Probabilistic Uncertainty (Monte Carlo Simulation)

- Discount rate: triangular (2%, 4.5%, 6%);

- Electricity price multiplier: triangular (0.9, 1.0, 1.2);

- Chemical price multiplier: triangular (0.85, 1.0, 1.20);

- Membrane replacement multiplier: triangular (0.80, 1.0, 1.30).

5.3. Managerial Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chang, H.-M.; Chen, S.-S.; Hsiao, S.-S.; Chang, W.-S.; Chien, I.C.; Duong, C.C.; Nguyen, T.X.Q. Water reclamation and microbial community investigation: Treatment of tetramethylammonium hydroxide wastewater through an anaerobic osmotic membrane bioreactor hybrid system. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 427, 128200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capodaglio, A.G.; Olsson, G. Energy issues in sustainable urban wastewater management: Use, demand reduction and recovery in the urban water cycle. Sustainability 2019, 12, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Water. Taiwan Water Corporation, Eighth District Management Office. Available online: https://www.water.gov.tw/dist8 (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Chiueh, Y.; Chen, H.H.; Ding, C.-F. The willingness of industrial water users for reclaimed water in Taiwan. In Current Issues of Water Management; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2011; pp. 261–270. [Google Scholar]

- Narvaez, L.; Janzen, S.; Eberle, C.; Sebesvari, Z. Technical Report: Taiwan Drought; United Nations University—Institute for Environment and Human Security (UNU-EHS): Bonn, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.W.; Tran, H.N.; Juang, R.-S. Reclamation and reuse of wastewater by membrane-based processes in a typical midstream petrochemical factory: A techno-economic analysis. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 5419–5430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.F.; Mao, C.-H. The current situation of water resources and future feasible plans in Taiwan. Int. J. Water 2021, 14, 240–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widianingtias, M.; Kazama, S.; Benyapa, S.; Takizawa, S. Assessment of the potential for water reclamation and reuse in Bali Province, Indonesia. Water 2023, 15, 2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, T.Y.; Perng, Y.H.; Liou, L.E. Impact and Adaptation Strategies in Response to Climate Change on Taiwan’s Water Resources. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2016, 858, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonazzi, D. Imminent Risk of a Global Water Crisis, Warns the UN World Water Development Report 2023; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/imminent-risk-global-water-crisis-warns-un-world-water-development-report-2023 (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Administration of Construction and Planning. Operations and Management Manual for Public Wastewater Treatment Plants—Fiscal Year 2018. 11 March 2018. Available online: https://www.nlma.gov.tw/uploads/files/83320fec359b5de471072414ca9933a8.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Zhang, G.; Xu, S.; Huang, M.; Li, M.; Jhang, W. Ammonia-Nitrogen Wastewater Treatment and Recovery Technologies and Case Studies. ITRI. 2013. Available online: https://www.itri.org.tw/ListStyle.aspx?DisplayStyle=01_content&SiteID=1&MmmID=1036233376167172113&MGID=620634556625725103 (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Bluewhalecorp. BlueWhalecorporation. 2024. Available online: https://www.bluewhalecorp.com (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Bogardi, J.J.; Bharati, L.; Foster, S.; Dhaubanjar, S. Water and its management: Dependence, linkages and challenges. In Handbook of Water Resources Management: Discourses, Concepts and Examples; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 41–85. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P. Unlocking policy effects: Water resources management plans and urban water pollution. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 365, 121642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awad, H.; Alalm, M.G.; El-Etriby, H.K. Environmental and cost life cycle assessment of different alternatives for improvement of wastewater treatment plants in developing countries. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 660, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Li, X.; Li, Y. Research on reclaimed water from the past to the future: A review. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 112–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.-S.; Liu, H.-C.; Lin, H.-C.; Lee, M.; Hou, C.-H. Synergizing MBR and MCDI systems as a sustainable solution for decentralized wastewater reclamation and reuse. Sustain. Environ. Res. 2024, 34, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linh, N.S.; Ahmed, F.; Loc, H.H. Applications of nature-based solutions in urban water management in Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam: A review. In Regional Perspectives of Nature-Based Solutions for Water: Benefits and Challenges; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 101–126. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Wang, J. Analysis and Evaluation of Taiwan Water Shortage Factors and Solution Strategies. Asian Soc. Sci. 2010, 6, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanchanapiya, P.; Tantisattayakul, T. Trends in wastewater reclamation in Thailand. Water Sci. Technol. 2022, 86, 2878–2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MFW. Environmental Forest Water Environmental. 2024. Available online: https://www.mfw.com.tw/ (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- National Land Management Agency, MOI. 2024. Available online: https://www.nlma.gov.tw/ch (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Cheng, H.-H.; Yu, W.-S.; Tseng, S.-C.; Wu, Y.-J.; Hsieh, C.-L.; Lin, S.-S.; Chu, C.-P.; Huang, Y.-D.; Chen, W.-R.; Lin, T.-F.; et al. Reclaimed water in Taiwan: Current status and future prospects. Sustain. Environ. Res. 2023, 33, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, K.C.; Kurniawan, T.A.; Goh, H.H.; Zhang, D.; Jiang, M.; Dai, W.; Khan, M.I.; Othman, M.H.D.; Aziz, F.; Anouzla, A.; et al. Strengthening Infrastructure Resilience for Climate Change Mitigation: Case Studies from the Southeast Asia Region with a focus on Wastewater Treatment Plants in the response to flood challenges. ACS EST Water 2024, 4, 3725–3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, D.A.; Chen, B.; Myers, C. Cooling water systems: An overview. In Water-Formed Deposits; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 239–267. [Google Scholar]

- Water Resources Agency. The Water Recycling Pilot Plant test Project of the Taichung Futian Water Resources Recycling Center. Available online: https://www.wra.gov.tw/wrapen/cp.aspx?n=2646 (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- James-Overheu, C.A. Recycled Water in Queensland: Building a Model for the Full Cost of Recycled Class A+ Water. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, Australia, 2016. Available online: https://research.usq.edu.au/item/q3878/recycled-water-in-queensland-building-a-model-for-the-full-cost-of-recycled-class-a-water (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Chen, T.-H.; Yeh, K.-H.; Lin, C.-F.; Lee, M.; Hou, C.-H. Technological and economic perspectives of membrane capacitive deionization (MCDI) systems in high-tech industries: From tap water purification to wastewater reclamation for water sustainability. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 177, 106012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Shou, Y.; Liu, B.; Li, H.; Liu, B.; Chen, S.; Dong, S. Exploring the Ecological Impacts and Implementation Strategies of Reclamation in Taiping Bay of Dalian Port as an Example. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2025, 166, 105023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taichung City Government Water Resources Bureau. Preliminary Planning Report and Construction and Financial Plan (Approved Version) for the BTO Project of the New Construction, Transfer, and Operation of Effluent Reclamation and Reuse at the Taichung Shuinan Water Resource Recovery Center; Taichung City Government Water Resources Bureau: Taichung, Taiwan, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hoinkis, J.; Deowan, S.A.; Panten, V.; Figoli, A.; Huang, R.R.; Drioli, E. Membrane bioreactor (MBR) technology: A promising approach for industrial water reuse. Procedia Eng. 2012, 33, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, C.; Lin, J. MBR Technology Applied in Industrial Wastewater Treatment and Reclamation-Twelve years of experience in Taiwan. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Membrane Bioreactors (MBR) for Wastewater Treatment of MBR Asia, Bangkok, Thailand, 21–22 January 2013. [Google Scholar]

| Water-Quality Parameter | Unit | Scenario A (UF + RO) | Scenario B (MBR) | Scenario C (Sand + UV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suspended Solids (SS) | mg/L | <2.5 | <2.5 | 1.9 |

| Ammonia Nitrogen (NH3-N) | mg/L | 0.13 | 1.33 | 7.1 |

| Turbidity | NTU | 0.07 | 0.46 | 2.1 |

| Total Hardness (as CaCO3) | mg/L | 2.7 | 146.2 | 148.4 |

| Total Organic Carbon (TOC) | mg/L | 0.22 | 3.93 | 2.9 |

| Electrical Conductivity (EC) | µS/cm | 51 | 606 | 477 |

| Module | Implementation Steps | Worked Example (for Inclusion in the Manuscript) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Unified discount rate and horizon | • Adopt a 20-year design life (per Water Reuse Operation Manual). • Baseline i = 4.5% i = 4.5%; sensitivity at 2% and 6%. | Baseline: n = 20 y, i = 4.5%. Sensitivity: −50 bp and +150 bp. |

| 2. Full CRF presentation + example | • Present the CRF formula and then work on scenario A. | P = 2.081 × 109 P = 2.081 × 109 NTD, n = 20, i = 4.5% → CRF = 0.0760 A = 158.3 A = 158.3 M NTD y−1. Unit CAPEX = A/(45,000CMD × 350)A/(45,000CMD × 350) = 10.0 NTD t−1. |

| 3. Electricity price and escalation | • Base tariff 2.62 NTD kWh−1 (2024). • Real increase 1.8% y−1. • List SEC values (A: 1.67; B: 1.41; C: 0.53 kWh t−1). | Year 1 power cost = 2.62 × SEC. Year y cost = prior-year cost × 1.018. |

| 4. CAPEX and OPEX sensitivity matrix | • Evaluate SUC for 3 discount rates × 3 power price shocks (10%, 0%, +20%). • Display as heat map/spider plot. | Example narrative: “With a +20% tariff, Scenario A’s OPEX of scenario A increases by 6.3 NTD t−1, increasing the SUC from 31.3 to 37.6 NTD t−1.” |

| Sr. | Parameter (s) | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Operating Days | 350 days/year, with 15 days of annual equipment check. |

| 2 | Water Production | 45,000 CMD. |

| 3 | Personnel Costs | Based on the staffing structure of the reclaimed water plant (data available per request), the salaries are graded accordingly. The total personnel cost is calculated as the base salary × 1.55. |

| 4 | Administrative Expenses | Determined by the complexity and amount of plant facilities and tasks, calculated as 10% to 15% of the total monthly base salary. This study sets it at 15% of the total monthly base salary. |

| 5 | Facility Maintenance Costs | Approximately 0.5% of the direct construction costs. |

| 6 | Water Treatment Chemical Costs | Included costs for acid-based chemicals, deodorants, disinfectants, and chemical dosing agents, individually set according to each plant’s treatment process. |

| 7 | Water Treatment Consumable Costs | Included costs for replacing activated carbon, UF/RO membranes, ozone equipment, UV equipment, and sand replenishment, individually set according to each plant’s treatment process. |

| 8 | In-House Water Quality Testing Costs | Included consumable fees costs at 3% of the base salary, instrument maintenance and calibration costs at 20% of consumable costs, and waste liquid disposal costs at 10% of consumable costs. |

| 9 | Waste Disposal Costs | Included costs for the removal and treatment of screenings, grit, and sludge. These are estimated based on market prices (data available per request), with scenarios A and C calculated to produce 1 ton of sludge cake, 0.01 tons of screenings (including plant waste), and 0.01 tons of grit per 10,000 tons treated sewage. Costs are estimated at the highest market price (screening removal cost: 3000 NTD/truck, treatment cost: 6000 NTD/ton; grit removal cost: 1000 NTD/ton, treatment cost: 9000 NTD/ton; sludge removal cost: 1000 NTD/ton, treatment cost: 8000 NTD/ton). Scenario B, which includes primary treatment, is estimated based on actual water plant data due to increased sludge production. |

| 10 | Mandatory and Regular Inspection Costs | Approximately 4% of the base salary. |

| 11 | Occupational Safety and Health Costs | Approximately 2% of the base salary. |

| 12 | Environmental Cleaning Costs | Approximately 5% of the base salary. |

| 13 | Insurance Costs | Included employer liability insurance, third party liability insurance, and public accident insurance, estimated at approximately 4000 NTD per person per year; commercial fire insurance, approximately 0.087% of the construction contract amount; additional insurance at 200% of the fire insurance rate. |

| 14 | Electricity Costs | Included basic electricity charges and variable electricity charges, individually set based on each plant’s electromechanical equipment. If historical electricity data are not available, the estimate can range from 0.4 to 1.5 NTD per ton of water treated. |

| 15 | Water Costs | Basic water charges and variable water charges included. Since reclaimed water plants do not install separate water meters, basic water charges are not considered. Variable water charges are estimated at 12 NTD per cubic meter, with an assumed daily water consumption of 90 L per person. |

| 16 | Management Fees and Profit | 8% of the total costs for items 1 to 15. |

| 17 | Value-added Tax | 5% of the total costs for items 1 to 16. |

| 18 | Unit Production Cost of Water (NTD/ton) | Total Annual Cost (NTD/year)/Total Water Volume (tons/year) (water production CMD × 350 days). |

| Item | Pretreatment Cost (NTD/ton) | Recycled Water Treatment Operation Cost (NTD/ton) | Total Treatment Cost (NTD/ton) | Construction Cost (NTD/ton) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario A | 5.56 | 13.31 | 18.87 | 11.07 |

| Scenario B | 16.16 | 16.16 | 9.67 | |

| Scenario C | 4.97 | 4.96 | 9.93 | 1.72 |

| Item | Unit | Tap Water Standard/Reference Value | Scenario A (UF + RO) | Scenario B (MBR) | Scenario C (Sand + UV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SS | mg L−1 | <2.5 | ○ < 2.5 | ○ < 2.5 | ▲ 0.3–3.4 |

| NH3-N | mg L−1 | <0.5 | ○ 0.13 | ▲ 1.33 | ▲ 7.1 |

| Turbidity | NTU | <4 (The water source is below 500 NTU) | ○ 0.07 | ○ 0.46 | ○ 0.8–3.3 |

| Total hardness (CaCO3) | mg L−1 | <400 | ○ 2.7 | ○ 146.2 | ○ 148.4 |

| TOC | mg L−1 | <4 | ○ 0.22 | ○ 3.93 | ○ 1.9–3.9 |

| EC | µS cm−1 | 105–307 | ◎ 51 | ▲ 606 | ▲ 457–497 |

| Sector | Rank | Water Consumption (Million m3) | Share of National Industrial Water Use (%) | Process Water (%) | Cooling Water (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Materials Manufacturing | 1 | 312.08 | 18.67 | 37.2 | 48.5 |

| Paper Products Manufacturing | 2 | 243.37 | 14.56 | 93.8 | 1.8 |

| Food Manufacturing * | 3 | 174.85 | 10.46 | 68.6 | 11.1 |

| Textile Industry | 4 | 144.38 | 8.64 | 84.7 | 6.8 |

| Fabricated Metal Products | 5 | 120.23 | 7.19 | 83.4 | 6.7 |

| Electronic Components Manufacturing | 6 | 94.10 | 5.63 | 81.9 | 12.0 |

| Plastic Products Manufacturing | 7 | 89.95 | 5.38 | 70.9 | 21.5 |

| Basic Metal Manufacturing | 8 | 81.12 | 4.85 | 28.2 | 65.5 |

| Petroleum/Coal Manufacturing | 9 | 63.99 | 3.83 | 28.2 | 56.6 |

| Non-metallic Mineral Products | 10 | 63.18 | 3.78 | 87.1 | 7.2 |

| Scenario | Chemical Materials | Paper Products | Textile Industry | Fabricated Metal Products | Electronic Components | Plastic Products | Basic Metals | Petroleum/Coal | Non-Metallic Mineral Products | Total (NTD/ton) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 16.57 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.33 |

| B | 8.25 | 18.64 | 17.59 | 17.59 | 33.14 | 14.58 | 19.00 | 6.32 | 17.55 | 16.10 |

| C | 9.03 | 20.41 | 19.25 | 19.25 | 34.71 | 15.96 | 20.80 | 6.92 | 19.21 | 17.50 |

| Scenario | Construction Cost | Operation Costs | Point-of-Use Pretreatment | Social Unit Cost | Water Quality (Rank) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 11.07 | 18.87 | 1.33 | 31.27 | 1 |

| B | 9.67 | 16.16 | 16.1 | 44.93 | 2 |

| C | 1.72 | 9.93 | 17.5 | 29.15 | 3 |

| Field | Definition/Formula |

|---|---|

| Construction Cost (CAPEX) | 1. First, convert the capital cost to an annualized value using the capital recovery factor (CRF): where years, . 2. Unit CAPEX: |

| Wastewater Pretreatment | Based on 2020 O&M data from the Fengshan/Futian public reclaimed water centers: . For Scenario B, this cost is already included in O&M, so the table shows “—" to avoid double-counting. |

| Reclaimed water O&M | |

| Extra On-site Treatment | Upper-bound additional UF/RO investment and operating costs at the user site: RO = 19 NTD/t, UF + RO = 20.8 NTD/t. If the plant effluent already meets the process/cooling requirements, the value is 0 NTD/t. |

| Social Unit Cost | |

| CP index | Inverse metric: Passes Social Cost; a higher value means more water-quality benefit per unit of social cost. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Abbas, S.; Chiang Hsieh, L.-H.; Yang, Y.-H.; Nawaz, I.; Lu, W.-L. Analyzing the Effectiveness of Water Reclamation Processes in Terms of Costs and Water Quality in Taiwan. Water 2026, 18, 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010062

Abbas S, Chiang Hsieh L-H, Yang Y-H, Nawaz I, Lu W-L. Analyzing the Effectiveness of Water Reclamation Processes in Terms of Costs and Water Quality in Taiwan. Water. 2026; 18(1):62. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010062

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbbas, Shahbaz, Lin-Han Chiang Hsieh, Yu-Hsien Yang, Irfan Nawaz, and Wen-Li Lu. 2026. "Analyzing the Effectiveness of Water Reclamation Processes in Terms of Costs and Water Quality in Taiwan" Water 18, no. 1: 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010062

APA StyleAbbas, S., Chiang Hsieh, L.-H., Yang, Y.-H., Nawaz, I., & Lu, W.-L. (2026). Analyzing the Effectiveness of Water Reclamation Processes in Terms of Costs and Water Quality in Taiwan. Water, 18(1), 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010062