Abstract

Drought is a natural phenomenon that has significant environmental and socioeconomic impacts. Drought indices are fundamental tools for quantifying and monitoring this hazard. In regions where ground data are scarce, hydrological modeling offers an alternative for drought monitoring and developing early warning systems. This study conducted a systematic literature review, following the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) protocol, to analyze the integrated application of the SWAT (Soil and Water Assessment Tool) model and the use of drought indices. A total of 803 articles published between 2011 and 2025 were identified in the Scopus and Web of Science databases, of which 115 met the eligibility criteria and were included in the review. The analysis revealed significant advances in the use of SWAT for drought monitoring and prediction, including the development of indices and forecasting systems. However, notable gaps remain, particularly the limited use of advanced statistical methodologies (e.g., machine learning and non-stationarity analyses) and the lack of harmonization and standardization across indices. Overall, this review establishes SWAT as a robust tool to support drought management strategies, while highlighting substantial untapped potential. Future research addressing these gaps is essential to strengthen drought indices and improve operational warning systems.

1. Introduction

Drought is one of the most destructive and globally significant natural hazards, affecting every region of the world and causing severe environmental and socioeconomic impacts [1,2]. Because of changes in precipitation and temperature patterns, this phenomenon has become increasingly frequent across the globe [3]. Drought is frequently classified into five main types: (i) meteorological drought, which occurs when precipitation remains below the average relative to the climatological reference period [4,5]; (ii) agricultural drought, related to the reduction of soil moisture due to water deficit, significantly compromising agricultural activities [4,6]; (iii) hydrological drought, which refers to anomalies in surface and subsurface water flows, resulting in reduced water availability [3,4,5]; (iv) socioeconomic drought, which arises from the combined impacts of the previous types and occurs when water demand exceeds supply capacity, affecting essential sectors of society [2,4,7]; and (v) ecological drought, when a prolonged water deficit exceeds ecosystem resilience, driving ecological systems into a critical state of vulnerability [8].

Monitoring drought events is essential for effective risk management. To this end, numerous studies and operational monitoring systems have employed standardized indices to quantify and categorize drought conditions [1,9,10,11,12]. These indices enable the identification, classification, and temporal analysis of drought events in diverse hydrometeorological contexts [13,14,15,16]. Among the most commonly used drought indices are the SPI (Standardized Precipitation Index) [13], the SPEI (Standardized Precipitation–Evapotranspiration Index) [15], the SSI (Standardized Streamflow Index [12], and the SRI (Standardized Runoff Index) [14]. The SPI is based solely on accumulated precipitation over different temporal scales and is widely applied due to its simplicity and the broad availability of precipitation data [17]. The SPEI, in turn, incorporates potential evapotranspiration in addition to precipitation, allowing for a more comprehensive assessment of the water balance [1,18]. Hydrological indices such as the SSI and SRI use streamflow or runoff data to identify water deficits in river systems and are more suitable for characterizing hydrological drought [5,14,19]. Each index has specific characteristics regarding input variables and spatial–temporal scale, and the choice of the most appropriate index depends on the study’s objectives and the availability of hydro-meteorological data.

Data availability is a critical factor in drought monitoring and early warning systems [20,21,22]. In many developing regions, the scarcity of long-term observational data, such as streamflow records exceeding 30 years, remains a major limitation for robust hydrological analyses [23,24,25,26]. Satellite-based products have been widely used to overcome these gaps particularly for precipitation and air temperature estimates [27,28,29,30,31]. However, their spatial and temporal resolution and potential biases may restrict applications for agricultural and hydrological drought assessments. Hydrological models, by contrast, provide a robust alternative for representing processes within the hydrological cycle and supporting the monitoring of agricultural and hydrological drought [32,33,34,35].

Drought impacts, as well as the effects of climate and land use changes on water resources, can be effectively assessed through hydrological modeling [36,37]. Hydrossedimentological models have been developed to simulate hydrological processes at varying spatial and temporal scales. When integrated with Geographic Information Systems (GISs), these models offer a physically based framework by enabling the spatially distributed representation of parameters across the landscape [38].

Among the different available models, the Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT), developed by the Agricultural Research Service of the United States Department of Agriculture (ARS-USDA), stands out for its widespread application worldwide [36,39,40,41]. SWAT is a free, open-source model designed to predict the impacts of current and future land use and management scenarios on water quantity and quality, sediment transport, nutrient cycling, and agrochemical yields within watersheds [39]). Its integration with geospatial tools enhances its effectiveness as a robust instrument for analyzing watershed-scale hydrological responses, including those related to drought conditions [10,42].

In this context, hydrological modeling, using tools such as the SWAT, emerges as a powerful alternative to fill gaps in observational data and simulate the hydrological balance of river basins. The integration of hydrological models and drought indices significantly enhances the potential of monitoring and early warning systems, particularly in regions with limited measurement stations or in future scenarios of land use/cover change and climate change.

Given the significant challenges associated with integrating SWAT and drought indices, it is essential to map the current state of the art in this research field. In this context, the systematic literature review stands out as a rigorous and transparent methodological approach for synthesizing existing knowledge. This approach enables the identification of critical research gaps, as well as the documentation of the scientific advancements achieved to date, thereby providing a foundation for guiding future directions in advancing knowledge in the field.

This study conducted a systematic literature review to combine application of the SWAT model and drought indices, with two main objectives: (i) to identify the key advances and limitations in this field, and (ii) to map the spatial distribution of studies applying this approach, thereby providing a comprehensive overview of current progress and research gaps in drought monitoring through hydrological modeling.

2. Materials and Methods

Data Acquisition

This study was based on a systematic literature review aimed at identifying research that applied the SWAT model in combination with drought indices, with the objective of evaluating the main advances and limitations in drought estimation using this hydrological model. The bibliographic search was conducted using the Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus databases in November 2024 and actualized in December 2025, covering the period from 2011 to 2025. The search strategy employed the following terms applied to all fields: ((“SWAT model” OR “Soil and Water Assessment Tool”) AND (“drought*” OR “water scarcity” OR “arid*”) AND (“SSI” OR “Standardized Streamflow Index” OR “SRI” OR “Standardized Runoff Index” OR “SDI” OR “Streamflow Drought Index” OR “SPI” OR “Standardized Precipitation Index” OR “SPEI” OR “Standardized Precipitation-Evapotranspiration Index”)). Only Open Access articles, specifically those categorized as Gold, Green, and Bronze access, written in English, classified as final research papers or review articles, were considered in this study. Publications of other types, such as book chapters, conference proceedings, and similar, were excluded from the review. It is important to acknowledge the limitations associated with restricting the selection exclusively to all open access articles. However, this choice was made to ensure that the systematic literature review was entirely transparent and reproducible. By including all open access publications, we aim to provide unrestricted access to all analyzed sources, thereby enabling other researchers to replicate and validate the findings of this study.

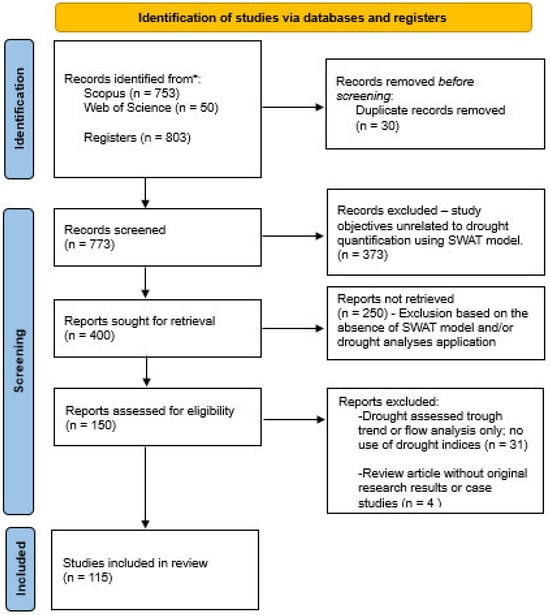

The screening of studies was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [43]. The process followed four main stages: identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion, as illustrated in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1). Bibliographic data processing, duplicate removal, and word cloud generation were performed using Bibliometrix (Version 5.1.0) R package [44]. The initial search yielded 803 articles. After export and processing in Bibliometrix for duplicate removal, the records underwent a two-phase screening process: (i) the first phase involved thematic relevance assessment based on titles and abstracts, which led to the exclusion of studies that did not employ the SWAT model for drought assessment or that addressed drought through methods other than hydrological modeling with SWAT; (ii) the second phase entailed a methodological evaluation through review of abstract and materials and methods sections, excluding articles that did not integrate SWAT with drought indices. The remaining 150 articles underwent full-text review, during which studies employing indirect drought analysis (e.g., without specific drought indices) and literature reviews lacking original results were excluded. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Figure 1), 115 studies were retained for full analysis.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram summarizing the systematic review process. The diagram illustrates the number of studies identified, screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review.

A keyword co-occurrence and linkage network analysis was carried out using VOSviewer Version1.6 [45], enabling visualization of thematic structures and research trends withing the selected literature. These tools were chosen for their robustness in performing bibliometric and network analyses, helping to provide a comprehensive understanding of the research scenario.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analysis of Scientific Production

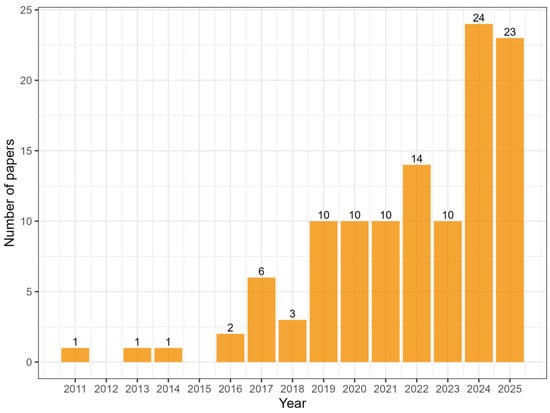

According to the bibliographic databases analyzed (Web of Science and Scopus), the earliest studies applying the SWAT hydrological model in combination with drought indices were published in 2011 (Figure 2). The starting point of this research line was the study by [10] which evaluated the impact of climate change on meteorological, agricultural, and hydrological droughts in central Illinois, USA.

Figure 2.

Number of papers published per year from 2011 to 2025.

In 2013, Ref. [46] published a study that assessed drought occurrence using the Palmer Drought Severity Index (PSDI), contributing to the advancement of drought-hydrological modeling integration. Subsequently, [47] evaluated the effects of forest fires and their impacts on the hydrological cycle, further expanding the applications of SWAT in drought-related studies.

Following this pioneering publication, there was a gap until 2016, when [48,49] published relevant studies. The first investigated the impact of climate change on streamflow and ecosystems, while the second proposed a new drought index aimed at assessing the impact of drought on the health of watercourses.

Over the analyzed period (2011–2025), the scientific literature accounted for 115 publications related to the use of the SWAT model in drought studies, totaling 1795 citations with an average of 15.60 citations per paper. Only 17 articles have not been cited to date. A total of 47 distinct drought indices were identified, although only two studies applied Machine Learning techniques in combination with SWAT, and very few publications adopted non-stationary approaches, indicating important methodological gaps that merit further investigation.

The increase in the number of publications on this topic, particularly from 2019, may be related to the intensification of research on the impacts of climate change across different sectors. Understanding the dynamics of droughts, in terms of their propagation, intensity, and duration, is essential for the development of mitigation and adaptation strategies, contributing to sustainable management in the context of climate variability.

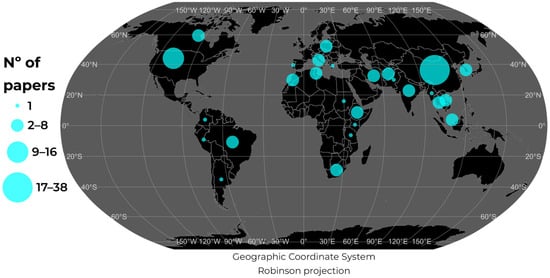

Regarding the spatial distribution of publications, China stands out with the highest number of studies published during the analyzed period, totaling 38 publications. This is followed by the United States, with 11 publications, and then Vietnam and Ethiopia, each with seven publications each (Figure 3). Conversely, countries such as Argentina, Colombia, Greece, Myanmar, Pakistan, Portugal, Peru, Kenya, Sudan, and Tanzania reported only one publication each. In Latin America, only four studies were identified, two of which were conducted in Brazil, highlighting the limited regional representation in the current body of literature. It is noteworthy that no studies were identified in Central America, Australia, or Russia, revealing regional gaps in the documented application of the SWAT model in conjunction with drought indices. However, this absence should not be interpreted as a lack of research activity in these areas. Instead, it likely reflects the stringent inclusion criteria adopted in this review; specifically, the focus on open access, peer-reviewed publications.

Figure 3.

Distribution of Papers by country (2011–2025).

In China, the studies addressed a variety of topics, including: the use of the SWAT model as a tool to support drought monitoring [50,51,52]; the development and application of new methodologies [50,52,53]; analysis of the impact of climate change on drought assessment [54]; and the investigation of drought propagation processes [55]. In the United States, studies focused on drought monitoring [10,24], the development and improvement of drought forecasting systems [56,57,58], and the development of new models for drought estimation [47].

In the other countries analyzed in this review, studies focused on the use of the SWAT model as a tool to support drought monitoring, with an emphasis on hydrological and agricultural droughts [48,59,60,61,62,63,64]. Topics related to drought propagation and the effects of climate change on drought duration, frequency, and intensity are also addressed. The limited number of studies in developing regions highlights the need to promote scientific production in vulnerable areas, where the impacts of drought may be even more severe [65,66].

3.2. Analysis of Keywords and Their Co-Occurrences

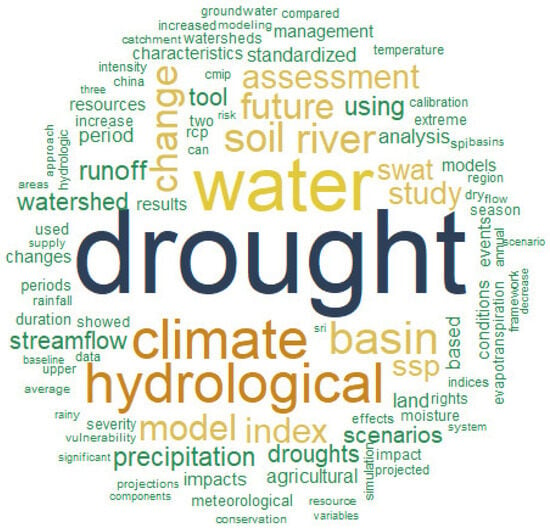

Based on the keywords extracted from the 115 analyzed articles, a word cloud was created (Figure 4) to identify the most recurrent terms and, consequently, the main topics addressed in the literature. There is a predominance of terms such as climate change, river basins, runoff, hydrological modeling, hydrological drought, soil moisture.

Figure 4.

Word cloud of the most frequent terms in the articles included in this review.

This analysis highlights a clear trend toward integrating drought studies within the context of climate change. The prominence of terms like soil moisture, runoff, precipitation, and streamflow reflects a strong focus on agricultural and hydrological droughts. Additionally, the frequent occurrence of words related to future indicates an increasing focus on projecting drought conditions under environmental drivers. Moreover, these findings reinforce previous results, emphasizing the key role of climate change in directing research on hydrological modeling associated with drought dynamics.

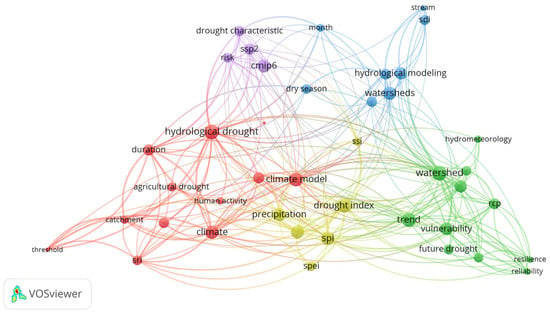

The keyword co-occurrence analysis resulted in the formation of four clusters representing thematic groups with strong interrelationships among the terms (Figure 5). Cluster 1 (red) groups keywords associated with hydrological drought and related concepts, including agricultural drought, duration, catchment, SRI, and climate model. This cluster reflects research focused on characterizing drought events and understanding their temporal dynamics and interactions with hydrological process. Cluster 2 (green) is related to watershed-scale assessment topics, including terms such as watershed, future drought, trend, vulnerability, reliability, resilience and RCP. Cluster 3 (blue) includes terms related to hydrological modeling, such as watersheds, stream, SDI. Cluster 4 (purple) includes terms such as climate scenarios and drought, including CMIP6, SSP2, risk, dry season, and drought characteristics. This cluster reflects the increasing use of global climate model projections to assess future drought risks and seasonal patterns. Cluster 5 (yellow-green) contains terms associated with drought indices and precipitation such as SPI, SPEI, SSI, drought index, and precipitation. This cluster highlights the central role of quantitative indicators in detecting, characterizing, and monitoring drought conditions.

Figure 5.

Keyword co-occurrence analysis in the reviewed articles.

This analysis highlights that, in this systematic literature review, most studies that have been conducted focused primarily on the impact of climate change on drought estimation and the assessment of the impacts of each type of drought.

The word clustering analysis indicates the main thematic lines in the literature, highlighting the strong connection between climate change, land use, drought types, and hydrological modeling, which reinforces the multidisciplinary approach adopted by studies in an effort to understand and predict the impacts of drought in different contexts.

3.3. Critical Appraisal of Literature

Table 1 presents the 20 most-cited articles among the 115 analyzed in this review. For each study, the research focus, as well as the main advances and limitations reported by the authors, are highlighted. The key themes of the studies focus on drought monitoring in historical and future scenarios, the development and improvement of drought indices, drought propagation, and the analysis of the impacts of climate change on the estimation and propagation of different drought types. Regarding the geographical distribution of the most-cited articles, China and United States stand out with five publications each among the top 20, followed by Ethiopia with three and Vietnam with two publications.

Table 1.

Top 20 most-cited articles: key advances and identified limitations.

All reviewed studies calibrated their hydrological models using streamflow as the primary reference variable. Given the substantial differences in the physical and climatic characteristics of the analyzed basins, the calibration procedures employed distinct parameter sets and value ranges. Despite this variability, a consistent pattern was observed: the most sensitive parameters were those associated with key hydrological processes, including surface runoff generation, baseflow dynamics, and soil water storage and movement. The calibrated parameters, corresponding ranges, and performance metrics used across studies are summarized in Table 1.

A significant limitation identified in the literature is the lack of standardization in the evaluation of model performance. Although the Nash–Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE) was the most frequently adopted objective function, many studies relied exclusively on this single metric, without employing multi-criteria evaluation approaches that more robustly capture model error structure and uncertainty. Additionally, inconsistencies in the terminology used to report performance metrics, such as the use of different acronyms for the same method, further complicate cross-study comparisons and hinder the establishment of a unified evaluation framework.

Several papers analyzed in this review focus on the study of climate change impacts on drought estimation (occurrence, duration, severity, and propagation), using different methodological approaches aimed at understanding how these changes influence drought. The pioneering study by [10] evaluated the reliability of global and regional climate models (GCMs and RCMs, respectively) in estimating different types of droughts and identified which type is most sensitive to the impacts of climate change. However, the study relied on the traditional stationary approach for calculating drought indices, as commonly adopted in many studies [72,73,74,75,76,77].

Similarly, Ref. [57] also adopted a stationary approach for drought estimation under climate change scenarios. The authors of [46] expanded the analysis of climate change impacts on streamflow and ecological effects in one of Africa’s largest natural reserves, being the first study to adopt this type of approach. Reference [70] also evaluated the impacts of climate change on drought estimates, but from the perspective of the probability of drought occurrence. They compared future probabilities with a reference period, enabling the identification of changes in drought frequency and intensity.

Regarding more complex approaches from a statistical perspective, Ref. [56] stand out by employing non-linear statistical analyses to investigate the influence of climatic, morphological, and basin-related variables on the duration and severity of hydrological droughts. The study tested different probability distributions applied to the Standardized Runoff Index (SRI), resulting in a more robust assessment of hydrological responses to multiple physical and climatic variables. This study highlights an important area of research focused on more complex and multivariate analyses. However, studies that integrate these analyses with hydrological models such as SWAT remain limited, representing a significant research gap for future investigations.

In the context of drought monitoring and forecasting, studies in this area have employed the integration of hydrological and climate models for this purpose. Sehgal and Sridhar [58] proposed the selection of the most appropriate probability distributions to capture soil moisture variability, which is crucial for representing agricultural drought. In addition to selecting the appropriate distribution, this study monitored agricultural drought on a weekly scale, enhancing the sensitivity of the monitoring system. Kang and Sridhar [35] advanced predictive modeling by integrating SWAT and the VIC (Variable Infiltration Capacity) model with CFSv2 (Climate Forecasting System version 2). The goal of this latter study was to simulate and forecast drought conditions in real time in the United States. This integration improved forecasting capability, contributing to the development of early warning systems. A similar approach was applied by [53] to drought monitoring and forecasting in the Mekong River Basin, using SWAT and CFSv2 data, which reinforce the feasibility of using these models as complementary tools for operational drought prediction.

The assessment of drought propagation, from meteorological anomalies to agricultural and hydrological impacts, is essential for understanding the temporal evolution, intensity, and spatial distribution of drought events. This type of analysis supports more accurate environmental planning and enhances the design of mitigation strategies, particularly in regions that are highly vulnerable to climatic extremes, several studies have addressed this topic [60,62,63,64]. Li et al. [55] employed an alternative approach, which replaces the traditional use of standardized drought indices by thresholds for drought categorization. Although this methodological approach is simple and easy to apply, it compromises comparability with other drought studies. Kamali et al. [60] provided an important contribution by evaluating drought propagation in the Karkheh River Basin using Drought Hazard Indices (DHIs) derived from the SPI, SRI, and SSWI, each representing different stages of drought development. By integrating historic and future projections from multiple bias-corrected GCMs within a SWAT-based modeling framework, the authors demonstrated how meteorological droughts may propagate into agricultural and hydrological droughts under changing climate conditions. The importance of understanding drought propagation is further illustrated by study [63], which investigated how meteorological drought conditions evolve into hydrological impacts under future climate scenarios in the Bouregreg watershed, a drought-prone Mediterranean basin in Northern Morocco. The study also identified spatial heterogeneity in drought propagation, showing that sub-basins influenced by coastal or high-altitude conditions exhibited greater hydrological resilience compared to inland areas. By coupling drought indices with distributed hydrological modeling, the authors demonstrated a robust framework for capturing how meteorological anomalies cascade into hydrological impacts, thereby offering valuable insights for water resource planning and drought risk management in climate-sensitive regions.

Among the studies proposing new approaches, Kim et al. [78] stand out as they developed an innovative method to forecast the future status of hydrological drought based on projected volumes of agricultural water withdrawal (AWW). This approach represents a significant innovation by integrating aspects of future water demand, which are often neglected in traditional modeling approaches that tend to focus on climatic and hydrologic variables.

Regarding the development of new drought indices using more robust statistical approaches, the study by [79] employed a non-linear approach through the Non-Linear Joint Hydrological Drought Index (NJHDI) to assess meteorological and hydrological drought risks under climate change scenarios. This index captures complex and non-linear relationships among different hydroclimatic variables, enhancing the ability to represent the interdependence between distinct types of droughts.

In relation to methodological innovations, study [67] developed a new hydrological drought index based on non-stationary statistical modeling. The authors proposed the Non-stationary Standardized Streamflow Index (NSSI), an extension of the classical SSI that explicitly incorporates climate-driven and human-induced non-stationarities in streamflow. The NSSI outperformed the traditional SSI by better capturing temporal variations in drought severity and spatial drought patterns under changing climatic and anthropogenic conditions, demonstrating its enhanced capability to characterize hydrological droughts in a non-stationary context.

The authors of [77] evaluated the propagation of meteorological and agricultural droughts using a non-stationary approach and developed a drought index that allowed the estimation of drought propagation time and propagation threshold through conditional probability. The results indicated that, under climate variability scenarios, there are changes in the frequency, intensity, and propagation thresholds of drought, showing that stationarity assumptions are inadequate for representing this process. The study provides valuable insights for the development of early warning systems and water resources management strategies in the context of climate variability.

Liang et al. [52] proposed a novel drought monitoring method by integrating the SWAT model with the empirical Kendall distribution function, aiming to overcome the limitations of observational data. Based on this approach, the multivariate integrated index named MAHDI (Meteorology–Agriculture–Hydrology Drought Index) was developed. This is a promising study, particularly because it enables a more integrated drought monitoring.

Guo et al. [80] proposed the Multivariate Standardized Drought Index (MSDI) through the application of a joint copula function, integrating the SPI and SSI (Standardized Soil Moisture Index). This approach enables a more comprehensive and robust assessment of drought characteristics by simultaneously accounting for the variability of both precipitation and soil moisture. Additionally, the authors employed wavelet analysis to investigate changes in the frequency of drought events over time, identifying trends and shifts in the periodicity of these events.

Aiming to understand the characteristics (duration, peak, and severity) of meteorological, agricultural, and hydrological droughts, Ref. [81] integrated the SWAT model with the SPEI, SSMI (Standardized Soil Moisture Index), and SWYI (Standard Water Yield Index) indices, which represent the meteorological, agricultural, and hydrological dimensions of drought, respectively. By applying copula functions, the authors constructed a three-dimensional joint distribution, which enabled the estimation of joint and concurrent return periods for the different types of droughts. This methodological strategy stands out to offer an innovative approach, allowing for a more integrated and accurate assessment of droughts, thereby supporting risk management in the context of watershed systems.

The authors of [82] conducted a pioneering study by applying explainable machine learning techniques, specifically, Multivariate Regression Trees (MVRT), to investigate the relationships between hydroclimatic variables and the severity of agricultural and hydrological droughts. The results demonstrated the model’s strong ability to identify key drought-driving factors and critical thresholds. For example, the study revealed that agricultural droughts are primarily triggered by the interaction between precipitation deficits and elevated evapotranspiration rates, whereas hydrological droughts are more directly associated with sustained precipitation deficits. Notably, this was the only study to integrate machine learning techniques with the SWAT model for drought assessment, highlighting its innovative contribution to the field.

In addition to the previous study, Arefin et al. [83] also incorporated machine learning techniques to assess drought-related vulnerability in Alabama watersheds. Their study integrated SWAT model with a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network to enhance streamflow simulations and support drought analysis by combining hydrological information, land use changes, and climate variability. This hybrid SWAT–Machine Learning approach demonstrated strong potential for improving vulnerability assessments based on drought indices in human-modified basins.

In relation to innovative topics, the pioneering study by [47] investigated the effects of forest fires on streamflow and the water balance, providing a detailed quantification of how forest fires alter the components of the hydrological regime. This was the only study identified that the employed such an approach. Nevertheless, a notable limitation in the reliance on hypothetical forest fire scenarios, which may constrain the applicability and representatives of the results under real conditions. Another innovative study was conducted by [84], which integrated the Comprehensive Drought Index (CDI) with SWAT+ to evaluate the effects of solar radiation management on drought hazards, vulnerabilities, and risks in the Kelantan River Basin, Malaysia. Although the study employed robust copula-based analyses, it presented some methodological limitations. Despites using CMIP6 climate projections and performing trend analyses for historical and future periods, the authors did not apply robust statistical techniques or non-stationary approaches to properly account for climate change induced shifts in hydrological regimes.

The study [68] was innovative in using the SWAT model to project future droughts and floods under climate change scenarios. By integrating SWAT with robust drought and flood indices, such as the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI), Standardized Streamflow Index (SSI), and the interquartile range method, the authors assessed the response of river flows in the Srepok River Basin (a major Mekong tributary) to future climatic conditions toward 2090. The results indicated an increase in flood occurrence, shifts toward more intense precipitation regimes, and strong links between climatic extremes and regional environmental characteristics. Overall, the study provided important scientific insights to support adaptive planning and enhance regional resilience to future drought and flood hazards.

Studies comparing the performance of different drought indices in monitoring drought events have also been identified, such as the work by [59]. In this study, six drought indices were evaluated in the monitoring of historical droughts in the Upper Blue Nile Basin. The findings indicate that the combined application of multiple indices enhances the robustness of drought detection and monitoring. Moreover, this approach is critically important for effective drought risk monitoring and management.

Most studies apply the SWAT hydrological model in regional contexts, focusing on the assessment and monitoring of droughts in major river basins. However, noteworthy contributions include the work of [35], who implemented SWAT across the contiguous United States for short-term drought forecasting, and [53] who applied the model in the Mekong River Basin for historical drought estimation and seasonal drought prediction. These studies underscore SWAT’s applicability as a robust tool not only at local basin scales but also in national and international contexts, demonstrating its capacity to support operational drought monitoring and forecasting systems.

3.4. Research Gaps and Future Directions

Among the main limitations identified in the analyzed literature are: (i) uncertainties related to the availability and quality of observational data; (ii) lack of harmonization in the terminology of drought indices; and (iii) the limited number of studies employing non-stationary statistical approaches, a factor particularly critical in analyses involving climate change. It was also observed that only a small number of studies use more complex statistical approaches for drought index estimation, and that only one study employed machine learning techniques to improve drought prediction. Furthermore, there is a gap regarding the selection of appropriate probability distributions for specific regions, which can enhance index estimation [1,12,75]. These points highlight opportunities for future research integrating hydrological modeling with advanced drought estimation, promoting more robust analyses applicable to water resources management.

A particularly relevant point is that most of the reviewed studies identify the availability and quality of observational data, especially meteorological and hydrological data, as a major limitation. Another notable gap concerns the limited discussion of the quality and spatial resolution of soil datasets used in hydrological modeling, despite the fact that soil properties, such as moisture dynamics, texture, and chemical characteristics, directly influence processes relevant to agricultural drought assessment. More broadly, the spatial resolution of input maps (e.g., soil, land use/land cover, topography) is critical for SWAT simulations, as it determines the model’s capacity to capture local variability in hydrological responses. The appropriate level of resolution is inherently linked to the study objectives and spatial scale: regional or watershed-scale analyses require more detailed and accurate datasets, whereas continental or global assessments may reasonably rely on coarser maps. However, when high-resolution data are unavailable—particularly in vulnerable or data-poor regions—reliance on outdated or overly generalized maps can impair the simulation of key processes such as infiltration, surface runoff, baseflow behavior, and soil-water dynamics, ultimately compromising the robustness of drought-related outputs.

In situations where ground observations are limited or unavailable, reanalysis products are often employed as an alternative; however, when these datasets cannot be validated against local observations, they may themselves become a significant source of uncertainty due to potential biases and coarse spatial resolution. This underscores the need to improve reanalysis data estimation and to develop robust statistical techniques for validating these datasets before their integration into hydrological models. A similar challenge arises with future climate projections from GCMs, which inherently carry model-dependent uncertainties that propagate through hydrological simulations. Without standardized validation protocols for selecting, bias-correcting, and applying GCMs, uncertainties in climate inputs can substantially distort the magnitude, frequency, and temporal dynamics of drought indices.

These data-related constraints also underscore an important weakness: drought indices become unreliable when poorly parameterized, as inadequate or biased input data, inappropriate probability distributions, or mischaracterized environmental variables can distort drought severity, duration, and frequency estimates [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Poor parametrization may lead to false drought signals, mask real events, or misrepresent drought propagation across meteorological, agricultural, and hydrological components, thereby compromising their usefulness for decision-making.

Since the quality of input data fundamentally constrains the robustness of model outputs, uncertainties in meteorological observations, soil attributes, reanalysis datasets, and climate projections directly affect the reliability of drought estimates. These considerations highlight the importance of improving soil mapping, expanding hydroclimatic observation networks, and strengthening validation procedures to enhance the accuracy of drought assessments using hydrological models such as SWAT. Regarding the soil maps used in hydrological modeling, these datasets play a fundamental role, as they significantly influence the simulation of key processes such as infiltration, surface runoff, and soil water storage [36], all essential variables for assessing agricultural and hydrological droughts. In this sense, promising future research would be to investigate how improving the resolution and quality of soil maps can contribute to enhancing the accuracy of drought assessments through hydrological modeling using SWAT model.

Regarding the lack of harmonization among drought indices, it was observed that, out of the 115 articles analyzed, 47 different drought indices were mentioned (Table 2). Although many of these indices are conceptually similar or even identical under different names, there is no global methodological standardization. This conceptual ambiguity is further complicated by the inconsistent application of terminology across studies. One of the major challenges in conducting comparative drought analyses is the lack of consistency in the naming and definition of drought indices. In many cases, identical acronyms are used to denote entirely different indices, leading to ambiguity and misinterpretation. For example, the acronym SSI may refer to the Standardized Streamflow Index, typically applied to hydrological drought characterization, while in other studies it denotes the Soil Moisture Stress Index, which is associated with agricultural drought. These terminological discrepancies create uncertainty about the type of drought being assessed and hinder the development of a common analytical framework. Consequently, cross-study comparisons become unreliable, meta-analyses are weakened, and the synthesis of regional or global drought patterns is substantially constrained. This lack of terminological harmonization highlights the need for clear definitions and standardized nomenclature to support robust and comparable drought assessments.

Table 2.

Overview of drought indices identified in this review.

Terminological inconsistencies also extend to broader drought categories, such as “vegetation drought” and “soil drought” which often refer to specific thresholds or impacts within agricultural drought but lack standardized definitions. This heterogeneity compromises the comparability between studies, hinders the execution of integrated analyses, and represents a significant challenge for the development of drought monitoring systems at regional or global scales. The absence of a unified protocol for the selection, calculation, and interpretation of indices also contributes to variations in results and limits the replicability of studies.

These limitations underscore the need for methodological advancements that promote the harmonization of drought indices, the broader use of non-stationary approaches, and the strengthening of hydroclimatic observation networks, to enhance the reliability and usefulness of drought analyses for water resources management, climate planning, and the efficient management of monitoring and early warning systems.

The SWAT model application in the assessment of drought indices stands out for enabling drought monitoring at the watershed scale, significantly contributing to the integrated water resources management. As a robust eco-hydrological model, when properly calibrated and validated, SWAT allows for the analysis of different types of droughts, meteorological, agricultural, and hydrological, enhancing the understanding of their impacts. The application of the SWAT model in drought index assessment is particularly valuable as it enables drought monitoring at the watershed scale, thereby supporting integrated water resources management. As a robust eco-hydrological modeling framework, SWAT, when appropriately calibrated and validated, facilitates the analysis of meteorological, agricultural, and hydrological droughts, improving our understanding of how drought impacts evolve across different system components. Such cross-type comparisons are essential for examining how precipitation deficits propagate through soil moisture and groundwater systems and ultimately affect streamflow. In this context, SWAT offers a powerful platform for investigating drought propagation processes, as it explicitly represents the continuum from climatic forcing to hydrological responses. Moreover, SWAT generates key environmental covariates, including land use and land-cover conditions, that can enhance the development and interpretability of drought indices, helping to explain variations in drought behavior across heterogeneous landscapes. Despite these strengths, important limitations, knowledge gaps, and research opportunities remain, particularly regarding improvements in cross-type drought comparisons, more refined representations of propagation mechanisms, and the integration of model outputs into operational early-warning systems. A synthesis of these challenges and perspectives, identified throughout the reviewed literature, is provided in Table 3. Finally, as a freely available and open-source tool, SWAT remains an accessible and cost-effective option for comprehensive drought assessment, especially when incorporated into multi-indicator monitoring frameworks.

Table 3.

Main gaps, limitations, and future perspectives identified in the literature.

3.5. Challenges and Advances in Tropical Regions: The Case of Brazil and the Future Research Agenda

The assessment of drought through hydrological modeling is particularly relevant in regions with high edaphoclimatic diversity, such as Brazil [158,159,160], where water demand is high and the impacts of climate change have intensified in recent years [75,161,162,163]. In this context, the integration of the SWAT model with drought indices represents a significant advancement in drought assessment and monitoring in tropical regions, which are highly vulnerable to hydroclimatic extremes and commonly affected by scarce observational data [91,92]. This approach is aligned with global recommendations for the enhancement of monitoring and early warning systems, as promoted by the Integrated Drought Management Programme (IDPM), developed by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) in cooperation with the Global Water Partnership (GWP). These frameworks emphasize the need for national policies focused on drought mitigation, monitoring and early warning, and risk and impact assessment [164].

In Brazil, these international guidelines are reflected in public policies such as the National Water Security Plan (Plano Nacional de Segurança Hídrica; PNSH), which aim to ensure an adequate water supply and the monitoring and control of floods and droughts, thereby reducing the country’s vulnerability to hydrological risks [164]. The integrated application of SWAT with drought indices can directly support these policies by providing watershed scale information, such as drought and flood estimates, as well as relevant environmental covariates (e.g., land use and land cover, soil moisture, among others), which are essential for agricultural and environmental planning. Despite the importance of this topic, only two studies applying drought indices combined with hydrological modeling were identified in the Brazilian context.

The first study, conducted by [64], evaluated the occurrence of meteorological and hydrological droughts in the Jaguari River basin (1027 km2), one of the headwater regions of the Cantareira system. The study presents advances by integrating observational and satellite data to calibrate and validate the SWAT model. The analyses indicate a potential temporary loss of resilience in the surface hydrological system, highlighting the vulnerability of the basin to climate variability.

The second study, conducted by [128], evaluated historical hydrological droughts in the Pandeiros River basin (3220 km2), a sub-basin of the São Francisco River. By using reanalysis data as a source of precipitation information, the study demonstrated the potential of these datasets in contexts with limited observational data coverage. This study represents an important advance in understanding droughts in a historical context.

Among the main challenges faced in Brazil are the scarcity of long and consistent time series of hydrological and meteorological data, as well as the low density of monitoring stations in several regions of the country [165]. This limitation directly affects the calibration and validation of hydrological models, compromising the accuracy of analyses. Nevertheless, the two studies cited here demonstrate the great potential for applying this type of research in Brazil, particularly in supporting integrated water resources management and drought monitoring.

Given the considerable methodological and contextual challenges in drought management research across Brazil’s climatic, hydrological, and socioeconomic diversity, there is a pressing need to develop more advanced approaches to drought monitoring, forecasting, and management. Based on the findings of this systematic review, the following future research agenda are proposed to address existing knowledge gaps and operational needs: (i) enhanced hydrological modeling capabilities by integrating remote sensing data and machine learning techniques to improve estimates of key hydrological variables in data scarce watersheds; (ii) development of research incorporating non-stationary drought indices and SWAT modeling; (iii) development of multivariate drought indices tailored to the country’s different biomes; (iv) systematically assess the impacts of the different drought types on Brazil’s biomes; (v) development of early systems for drought based on hydrological modeling; (vi) improvement of public policies related to drought risk management and resilience-building; (vii) investigation of drought propagation process in river basins; (viii) evaluating the influence of soil map resolution on agricultural and hydrological drought estimations using SWAT model; and (ix) establish standardized national protocols for drought index calculation, interpretation and communication to support decision-making. This agenda underscores the critical integration of scientific advances into operational frameworks, within the context of increasing climate variability and water scarcity challenges in Brazil.

4. Final Considerations

Based on the bibliometric analysis of 115 articles from the WOS and Scopus database, it can be stated that research on the use of the SWAT hydrological model for drought assessment has shown a steadily increasing trend from 2011 to 2025, reflecting the model’s applicability in multidisciplinary studies that integrate several drought indices.

Most studies employ multidisciplinary approaches, combining the SWAT model with various drought indices (meteorological, agricultural, and hydrological). Studies are predominantly concentrated in China and the United States, where substantial progress has been observed in terms of using the SWAT model to develop and improve drought forecasting and monitoring systems, to study drought propagation, and to advance new methodologies.

In regions with scarce data, the integration of the SWAT model with drought indices has proven to be a promising alternative for drought monitoring and the development of early warning systems, thereby supporting risk management in vulnerable areas. In tropical regions such as Brazil, advancements in this area remain limited. Only two studies have employed the SWAT model to monitor historical events, highlighting an underexplored but promising field for future research.

Despite considerable progress, significant research gaps remain. The application of more complex statistical methodologies, such as non-stationarity approaches or machine learning techniques to enhance drought index development, is still infrequent, representing a clear opportunity for future research. Moreover, a lack of harmonization among the use of drought indices has been identified, suggesting the need for more standardized protocols to facilitate comparative studies at regional and global scales.

In summary, the SWAT model stands out as a robust tool for deepening the understanding of drought phenomena. However, its potential remains underexplored, particularly concerning the application of innovative statistical methods and the development of integrated real-time monitoring systems. Future research should focus on bridging these gaps to enhance drought monitoring and mitigation strategies across regional and global scales.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L.M., J.F.L.d.M., É.L.B. and G.C.B. methodology, L.L.M.; software, L.L.M.; validation L.L.M., J.F.L.d.M., É.L.B. and G.C.B.; formal analysis, L.L.M.; investigation, L.L.M., J.F.L.d.M., É.L.B., G.C.B., W.A.M. and M.E.C.F.; resources, É.L.B.; data curation, L.L.M.; writing—original draft preparation, L.L.M.; writing—review and editing, L.L.M., J.F.L.d.M., É.L.B., G.C.B., W.A.M. and M.E.C.F.; visualization, L.L.M., J.F.L.d.M., É.L.B., G.C.B., W.A.M. and M.E.C.F.; supervision, É.L.B. and J.F.L.d.M.; project administration, É.L.B. and J.F.L.d.M.; funding acquisition, L.L.M., É.L.B. and G.C.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financed, in part, by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), Brazil. Process Number #2022/09319-9, #2024/08132-8 (L.L.M.); Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001 (W.A.M. and M.E.C.F.) and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq)/Research Productivity Fellowship Process Number #302963/2025-1 (É.L.B) and #304609/2022-6 (G.C.B.).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used DeepSeek for the purposes of reviewing the English grammar. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

Author É.L.B. Bolfe was employed by the public company Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Stagge, J.H.; Tallaksen, L.M.; Gudmundsson, L.; Van Loon, A.F.; Stahl, K. Candidate distribution for climatological drought indices (SPI and SPEI). Int. J. Climatol. 2015, 35, 4027–4040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevacqua, A.G.; Chaffe, P.L.B.; Chagas, V.B.P.; AghaKouchak, A. Spatial and temporal patterns of propagation from meteorological to hydrological droughts in Brazil. J. Hydrol. 2021, 603, 126902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teutschbein, C.; Jonsson, E.; Todorović, A.; Tootoonchi, F.; Stenfors, E.; Grabs, T. Future drought propagation through the water-energy-food-ecosystem nexus—A Nordic perspective. J. Hydrol. 2023, 617, 128963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhite, A.D.; Glantz, M.H. Understanding: The drought phenomenon: The role of definitions. Water Int. 1985, 10, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; López-Moreno, J.I.; Beguería, S.; Lorenzo-Lacruz, J.; Azorin-Molina, C.; Morán-Tejeda, E. Accurate computation of a streamflow drought index. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2012, 17, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blain, G.C. Revisiting the probabilistic definition of drought: Strengths, limitations and an agrometeorological adaptation. Bragantia 2012, 71, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laimighofer, J.; Laaha, G. How standard are standardized drought indices? Uncertainty components for the SPI & SPEI case. J. Hydrol. 2022, 613, 128385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crausbay, S.D.; Ramirez, A.R.; Carter, S.L.; Cross, M.S.; Hall, K.R.; Bathke, D.J.; Betancourt, J.L.; Colt, S.; Cravens, A.E.; Dalton, M.S.; et al. Defining Ecological Drought for the Twenty-First Century. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2017, 317, 2543–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svoboda, M.; LeComte, D.; Hayes, M.; Heim, R.; Gleason, K.; Angel, J.; Rippey, B.; Tinker, R.; Palecki, M.; Stooksbury, D.; et al. The Drought Monitor. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2002, 83, 1181–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Hejazi, M.; Cai, X.; Valocchi, A.J. Climate change impact on meteorological, agricultural, and hydrological drought in central Illinois. Water Resour. Res. 2011, 47, W09527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, J. Probabilistic projections of hydrological droughts through convection-permitting climate simulations and multimodel hydrological predictions. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2020, 125, e2020JD032914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieper, P.; Düsterhus, A.; Baehr, J. A universal standardized precipitation index candidate distribution function for observations and simulations. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2020, 24, 4541–4565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, T.B.; Doesken, N.J.; Kleist, J. The relationship of drought frequency and duration to time scales. In Proceedings of the 8th Conference on Applied Climatology, Anaheim, CA, USA, 17–22 January 1993; pp. 179–183. [Google Scholar]

- Shukla, S.; Wood, A.W. Use of a standardized runoff index for characterizing hydrologic drought. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2008, 35, L02405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Beguería, S.; López-Moreno, J.I. A multiscalar drought index sensitive to global warming: The Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index. J. Clim. 2010, 23, 1696–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zargar, A.; Sadiq, R.; Naser, B.; Khan, F.I. A review of drought indices. Environ. Rev. 2011, 19, 333–349. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/envirevi.19.333 (accessed on 20 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Svoboda, M.D.; Hayes, M.J.; Wilhite, D.A.; Wen, F. Appropriate application of the standardized precipitation index in arid locations and dry seasons. Int. J. Climatol. 2007, 27, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, V.R.; Blain, G.C.; de Avila, A.M.H.; Pires, R.C.d.M.; Pinto, H.S. Impacts of climate change on drought: Changes to drier conditions at the beginning of the crop growing season in southern Brazil. Bragantia 2018, 77, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.K.; Singh, V.P. A review of drought concepts. J. Hydrol. 2010, 391, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WMO (World Meteorological Organization). Drought Monitoring and Early Warning: Concepts, Progress and Future Challenges; WMO-No. 1006; WMO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pulwarty, R.S.; Sivakumar, M.V.K. Information systems in a changing climate: Early warnings and drought risk management. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2014, 3, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Yuan, X.; Xia, Y.; Hao, F.; Singh, V.P. An overview of drought monitoring and prediction systems at regional and global scales. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2017, 98, 1879–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannah, D.M.; Demuth, S.; van Lanen, H.A.J.; Looser, U.; Prudhomme, C.; Rees, G.; Stahl, K.; Tallaksen, L.M. Large-scale river flow archives: Importance, current status and future needs. Hydrol. Process. 2011, 25, 1191–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trambauer, P.; Maskey, S.; Winsemius, H.; Werner, M.; Uhlenbrook, S. A review of continental scale hydrological models and their suitability for drought forecasting in (sub-Saharan) Africa. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2014, 66, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masih, I.; Maskey, S.; Mussá, F.E.F.; Trambauer, P. A review of droughts on the African continent: A geospatial and long-term perspective. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2014, 18, 3635–3649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Meteorological Organization (WMO). State of Climate Services 2021: Water; WMO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Huffman, G.J.; Bolvin, D.T.; Nelkin, E.J.; Wolff, D.B.; Adler, R.F.; Gu, G.; Hong, Y.; Bowman, K.P.; Stocker, E.F. The TRMM Multisatellite Precipitation Analysis (TMPA): Quasi-global multiyear combined-sensor precipitation estimates at fine scales. J. Hydrometeorol. 2007, 8, 38–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, B.; Hirschi, M.; Jimenez, C.; Ciais, P.; Dirmeyer, P.A.; Dolman, A.J.; Fisher, J.B.; Jung, M.; Ludwig, F.; Maignan, F.; et al. Benchmark products for land evapotranspiration: LandFlux-EVAL multi-data set synthesis. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2013, 17, 3707–3720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Miao, C.; Duan, Q.; Ashouri, H.; Sorooshian, S.; Hsu, K.-L. A review of global precipitation data sets: Data sources, estimation, and intercomparisons. Rev. Geophys. 2018, 56, 79–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blain, G.C.; Rocha, G.S.; Martins, L.L. Elevações na frequência de ocorrência de secas meteorológicas no Estado de São Paulo sob condições de mudanças climáticas. Derbyana 2023, 44, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- José, R.V.d.S.; Martins, L.L.; Coltri, P.P.; Steinke, E.T.; Greco, R. Performance of meteorological data for drought monitoring in areas of the Brazilian Semi-Arid. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2024, 156, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xiong, L.; Dong, L.; Zhang, J. Effects of the Three Gorges Reservoir on the hydrological droughts at the downstream Yichang station during 2003–2011. Hydrol. Process. 2012, 27, 3981–3993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheffield, J.; Wood, E.F.; Roderick, M.L. Little change in global drought over the past 60 years. Nature 2012, 491, 435–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Loon, A.F. Hydrological drought explained. WIREs Water 2015, 2, 359–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Sridhar, V. Improved drought prediction using near real-time climate forecast and simulated hydrologic conditions. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, J.G.; Srinivasan, R.; Muttiah, R.S.; Williams, J.R. Large area hydrologic modeling and assessment part I: Model development. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 1998, 34, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriasi, D.N.; Arnold, J.G.; Van Liew, M.W.; Bingner, R.L.; Harmel, R.D.; Veith, T.L. Model evaluation guidelines for systematic quantification of accuracy in watershed simulations. Trans. ASABE 2007, 50, 885–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neitsch, S.L.; Arnold, J.G.; Kiniry, J.R.; Williams, J.R. Soil and Water Assessment Tool: Theoretical Documentation, Version 2009; (Technical Report); Grassland, Soil and Water Research Laboratory, Agricultural Research Service, Blackland Research Center, Texas AgriLife Research, Texas A&M-AgriLife: Temple, TX, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gassman, P.W.; Reyes, M.R.; Green, C.H.; Arnold, J.G. The Soil and Water Assessment Tool: Historical Development, Applications, and Future Research Directions. Trans. ASABE 2007, 50, 1211–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressiani, D.A.; Gassman, P.W.; Fernandes, J.G.; Garbossa, L.H.P.; Srinivasan, R.; Bonumá, N.B.; Mediondo, E.M. Review of Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT) applications in Brazil: Challenges and prospects. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2015, 8, 9–35. [Google Scholar]

- Abbaspour, K.C.; Rouholahnejad, E.; Vaghefi, S.; Srinivasan, R.; Yang, H.; Kløve, B. A continental-scale hydrology and water quality model for Europe: Calibration and uncertainty of a high-resolution large-scale SWAT model. J. Hydrol. 2015, 524, 733–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, L.L. Impact of climate and land use changes on water availability in the Piracicaba, Capivari and Jundiaí river basin. Ph.D. Thesis, Agronomic Institute of Campinas, Campinas, SP, Brazil, 2024; 167p. Available online: https://www.iac.sp.gov.br/areadoinstituto/posgraduacao/repositorio/storage/teses_dissertacoes/Leticia_Lopes_Martins.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Shi, X.; Yang, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhao, K.; Yuan, Y. Modified Palmer Drought Severity Index Based on Distributed Hydrological Simulation. Math. Probl. Eng. 2013, 2013, 327374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batelis, S.C.; Nalbantis, I. Potential Effects of Forest Fires on Streamflow in the Enipeas River Basin, Thessaly, Greece. Environ. Process. 2014, 1, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basheer, A.K.; Lu, H.; Omer, A.; Ali, A.B.; Abdelgader, A.M.S. Impacts of climate change under CMIP5 RCP scenarios on the streamflow in the Dinder River and ecosystem habitats in Dinder National Park, Sudan. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2016, 20, 1331–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfahanian, E.; Nejadhashemi, A.P.; Abouali, M.; Daneshvar, F.; Renami, A.A.; Herman, M.R.; Tang, Y. Defining drought in the context of stream health. Ecol. Eng. 2016, 94, 668–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Xia, J.; She, D. Drought characteristics analysis based on an improved PSDI in the Wei River Basin of China. Water 2017, 9, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Fan, J.; Deng, Q.; Wang, X. Spatiotemporal heterogeneity in meteorological and hydrological drought patterns and propagations influenced by climatic variability, LULC change, and human regulations. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Su, X.; Feng, K. Drought propagation and construction of comprehensive drought index based on the Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT) and empirical Kendall distribution function (KC’): A case study for the Jinya River basin in northwestern China. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 21, 1323–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Sridhar, V. A near-term drought assessment using hydrological and climate forecasting in the Mekong River Basin. Int. J. Climatol. 2020, 41, E2497–E2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yin, X.; Zhou, G.; Bruijnzeel, L.A.; Dai, A.; Wang, F.; Gentine, P.; Zhang, G.; Song, Y.; Zhou, D. Rising rainfall intensity induces spatially divergent hydrological changes within a large river basin. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lu, S.; Chen, X. Drought propagation patterns under naturalized condition using daily hydrometeorological data. Adv. Meteorol. 2018, 2018, 2469156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veetil, V.A.; Mishra, A.K. Multiscale hydrological drought analysis: Role of climate, catchment and morphological variables and associated thresholds. J. Hydrol. 2020, 582, 124533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Sridhar, V. Combined statistical and spatially distributed hydrological model for evaluating future drought indices in Virginia. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2017, 12, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehgal, V.; Sridhar, V. Watershed-scale retrospective drought analysis and seasonal forecasting using multi-layer high-resolution simulated soil moisture for Southeastern, U.S. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2019, 23, 100191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayissa, Y.; Maskey, S.; Tadesse, T.; Van Andel, S.J.; Moges, S.A.; Van Griensven, A.; Solomatine, D. Comparison of the Performance of Six Drought Indices in Characterizing Historical Drought for the Upper Blue Nile Basin, Ethiopia. Geosciences 2018, 8, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamali, B.; Kouchi, D.H.; Yang, H.; Abbaspour, K. Multilevel drought hazard assessment under climate change scenarios in semi-arid regions—A case study of the Karkheh River Basin in Iran. Water 2017, 9, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lweendo, M.K.; Lu, B.; Wang, M.; Zhang, H.; Xu, W. Characterization of droughts in humid subtropical region, Upper Kafue River Basin (Southern Africa). Water 2017, 9, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam, T.T.; Khoi, D.N.; Thao, N.T.T.; Nhi, P.T.T.; Quan, N.T.; Hoan, N.X.; Nguyen, V.T. Impact of climate change on meteorological, hydrological and agricultural droughts in the Lower Mekong River Basin: A case study of the Srepok Basin, Vietnam. Water Environ. J. 2019, 33, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouziyne, Y.; Abouabdillah, A.; Chehbouni, A.; Hanich, L.; Bergaoui, K.; McDonnell, R.; Benaabidate, L. Assessing hydrological vulnerability to future droughts in a Mediterranean watershed: Combined indices-based and distributed modeling approaches. Water 2020, 12, 2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, L.M.; da Rocha, H.R. Serial drought and loss of hydrologic resilience in a subtropical basin: The case of water inflow into the Cantareira reservoir system in Brazil during 2013–2021. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2022, 44, 101235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, M.R.; Matanó, A.; Van Loon, A.F.; Odongo, R.A.; Teklesadik, A.D.; Wamucii, C.N.; van dem Homberg, M.J.C.; Waruru, S.; Teuling, A.J. Linking reported drought impacts with drought indices, water scarcity and aridity: The case of Kenya. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2023, 23, 2915–2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baatz, R.; Ghazaryan, G.; Hagenlocher, M.; Nendel, C.; Toreti, A.; Rezaei, E.E. Drought research priorities, trends, and geographic patterns. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2025, 29, 1379–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Duan, L.; Liu, T.; Li, J.; Feng, P. A Non-stationary Standardized Streamflow Index for hydrological drought using climate and human-induced indices as covariates. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 693, 134278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, T.N.D.; Do, S.K.; Nguyen, B.Q.; Tran, V.N.; Grodzka-Łukaszewska, M.; Sinicyn, G.; Lakshmi, V. Investigating the Future Flood and Drought Shifts in the Transboundary Srepok River Basin Using CMIP6 Projections. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 3380514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emiru, N.C.; Recha, J.W.; Thompson, J.R.; Belay, A.; Aynekulu, E.; Manyevere, A.; Demissie, T.D.; Osano, P.M.; Hussein, J.; Molla, M.B. Impact of climate change on the Hydrology of the Upper Awash River Basin, Ethiopia. Hydrology 2022, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orke, Y.A.; Li, M.-H. Impact of climate change on hydrometeorology and droughts in the Bilate Watershed, Ethiopia. Water 2022, 14, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Sung, J.H.; Chung, E.-S.; Kim, S.U.; Son, M.; Shiru, M.S. Comparison of projection in meteorological and hydrological droughts in the Cheongmicheon Watershed for RCP4.5 and SSP2-4.5. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, S. An Introduction to Statistical Modeling of Extreme Values; Springer: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zwiers, F.W.; Li, G. Monte Carlo experiments on the detection of trends in extreme values. J. Clim. 2004, 17, 1945–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, S.; Dosio, A.; Sterl, A.; Barbosa, P.; Vogt, J. Projection of occurrence of extreme dry-wet years and seasons in Europe with stationary and nonstationary standardized precipitation indices. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2013, 118, 7628–7639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blain, G.C.; Sobierajski, G.R.; Weight, E.; Martins, L.L.; Xavier, A.C.F. Improving the interpretation of standardized precipitation index estimates to capture drought characteristics in changing climate conditions. Int. J. Climatol. 2022, 45, 5586–5601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blain, G.C.; Sobierajski, G.R.; Martins, L.L.; Sparks, A.H. The SPIChanges R-package: Improving the interpretation of the standardized precipitation index under changing climate conditions. Environ. Model. Softw. 2025, 192, 106573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.; Feng, P.; Li, J.; Shi, X.; Wang, H. Effects of land use/cover change on propagation dynamics from meteorological to soil moisture drought considering nonstationarity. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 312, 109452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Sung, J.H.; Shahid, S.; Chung, E.-S. Future hydrological drought analysis considering agricultural water withdrawal under SSP scenarios. Water Resour. Manag. 2022, 36, 2913–2930, Correction in Water Resour. Manag. 2022, 36, 2931. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-022-03210-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huang, Y.; Fan, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Deng, Q. Meteorological and Hydrological Drought Risks under Future Climate and Land-Use-Change Scenarios in the Yellow River Basin. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Chen, F.; Wang, B.; Liu, L.; Chen, X.; Huang, H.; Bai, H.; Liao, K.; Xia, Z.; Xiang, K.; et al. Developing a multivariate drought index to assess drought characteristics based on the SWAT-Copula method in the Poyang Lake basin, China. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 170, 113123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Niu, C.; Huang, N. Constructing the Joint Probability Spatial Distribution of Different Levels of Drought Risk Based on Copula Functions: A Case Study in the Yellow River Basin. Water 2024, 16, 3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paez-Trujillo, A.; Cañon, J.; Hernandez, B.; Corzo, G.; Solomatine, D. Multivariate regression trees as an “explainable machine learning” approach to explore relationships between hydroclimatic characteristics and agricultural and hydrological drought severity: Case study Cesar River basin. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2023, 23, 3863–3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefin, R.; Frame, J.; Tick, G.R.; Bussan, D.D.; Goodliffe, A.M.; Zhang, Y. SWAT Machine Learning-Integrated Modeling for Ranking Watershed Vulnerability to Climate Variability and Land-Use Change in Alabama, USA, in 1990–2023. Environments 2024, 12, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Tan, M.L.; Samat, N.; Chen, Z.L.; Zhang, F. Integrating a comprehensive index and the SWAT+ model to assess drought characteristics and risks under solar radiation modification. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 169, 113852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, X.; Lei, X.; Song, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, W. Impact of human activities on the propagation dynamics from meteorological to hydrological drought in the Nenjiang River Basin, Northeast China. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 58, 102214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, M.; Abiodun, B. Modelling the potential of land use change to mitigate the impacts of climate change on future drought in the Western Cape, South Africa. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2024, 155, 6371–6392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Cai, Y.; Cong, P.; Xie, Y.; Chen, W.; Cai, J.; Bai, X. Quantitation of meteorological, hydrological and agricultural drought under climate change in the East River basin of south China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimaru, A.N.; Gathenya, J.M.; Cheruiyot, C.K. The Temporal Variability of Rainfall and Streamflow into Lake Nakuru, Kenya, Assessed Using SWAT and Hydrometeorological Indices. Hydrology 2019, 6, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Wu, Z.; Xiao, P.; Sun, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z. Possible Future Climate Change Impacts on the Meteorological and Hydrological Drought Characteristics in the Jinghe River Basin, China. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tri, D.Q.; Dat, T.T.; Truong, D.D. Application of Meteorological and Hydrological Drought Indices to Establish Drought Classification Maps of the Ba River Basin in Vietnam. Hydrology 2019, 6, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemu, M.G.; Wubneh, M.A.; Worku, T.A.; Womber, Z.R.; Chanie, K.M. Comparison of CMIP5 models for drought predictions and trend analysis over Mojo catchment, Awash Basin, Ethiopia. Sci. Afr. 2023, 22, e01891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, M.; Azam, S.; Sauchyn, D.; Basu, S. Assessment of Meteorological and Agricultural Drought Indices under Climate Change Scenarios in the South Saskatchewan River Basin, Canada. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoi, D.N.; Sam, T.T.; Loi, P.T.; Hung, B.V.; Nguyen, V.T. Impact of climate change on hydro-meteorological drought over the Be River Basin, Vietnam. J. Water Clim. Change 2021, 12, 3159–3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Lee, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, S. Assessment of Water Supply Stability for Drought-Vulnerable Boryeong Multipurpose Dam in South Korea Using Future Dry Climate Change Scenarios. Water 2019, 11, 2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirauer, J.; Zhu, C. Drought in the twenty-first century in a water-rich region: Modeling study of the Wabash River Watershed, U.S.A. Water 2020, 12, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, M.; Rohith, A.N.; Cibin, R.; Aruffo, E.; Abouzied, G.A.A.; Di Carlo, P. Understanding future hydrologic challenges: Modelling the impact of climate change on river runoff in central Italy. Environ. Chall. 2024, 15, 100899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, C.G.; Masson, I.; Cazenave, G.; Vives, L.; Amábile, G.V. A Novel Approach for the Integral Management of Water Extremes in Plain Areas. Hydrology 2019, 6, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Huang, W.; Luo, X.; Guo, J.; Yuan, Z. The Spread of Multiple Droughts in Different Seasons and Its Dynamic Changes. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi, P.; Kharazi, H.G. Impact of climate change on droughts: A case study of the Zard River Basin in Iran. Water Pract. Technol. 2023, 18, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, R.P.; Dubey, S.K.; Gaurav, K. Streamflow of the Betwa River under the Combined Effect of LU-LC and Climate Change. Agriculture 2022, 12, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmany, B.; Visessri, S.; Pech, P.; Ekkawatpaint, C. The Impact of Climate Change on Hydro-Meteorological Droughts in the Chao Phraya River Basin, Thailand. Water 2024, 16, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tladi, T.M.; Ndambuki, J.M.; Salim, R.W. Meteorological drought monitoring in the Upper Olifants sub-basin, South Africa. Phys. Chem. Earth 2022, 129, 103273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, D.; Mall, R.K.; Raju, K.N.P.; Suryavanshi, S. Multivariate drought analysis for the temperature homogeneous regions of India: Lessons from the Gomati River basin. Meteorol. Appl. 2022, 29, 2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senbeta, T.; Napiórkowski, J.J.; Karamuz, E.; Kochanek, K.; Woyessa, Y.E. Impacts of water regulation through a reservoir on drought dynamics and propagation in the Pilica River watershed. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2024, 53, 101812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Tan, M.L.; Chun, K.P.; Zhang, F. Evaluation of four gridded climate products for streamflow and drought simulations in the Kelantan River Basin, Malaysia. Geocarto Int. 2025, 40, 2453615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasirabadi, M.S.; Khosrojerdi, A.; Musavi-jahromi, S.H.; Tabrizi, M.S. Simulating the climate change effects on the Karaj Dam basin: Hydrological behavior and runoff. J. Water Clim. Change 2024, 15, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeysingha, N.S.; Ray, R.L.; Tarkegn, T.G. Future hydro-climate extremes in the cypress creek watershed in Texas under different CMIP6 scenarios. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2025, 11, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H.; Vo, L.P. Impacts of climate change and reservoir operation on droughts: A case study in the Upper Part of Dong Nai River Basin, Vietnam. J. Water Clim. Change 2025, 16, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worqlul, A.W.; Dile, Y.T.; Schmitter, P.; Jeong, J.; Meki, M.N.; Gerik, T.J.; Srinivasan, R.; Lefore, N.; Clarke, N. Water resource assessment, gaps, and constraints of vegetable production in Robit and Dangishta watersheds, Upper Blue Nile Basin, Ethiopia. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 223, 105767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]