Physics-Consistent Overtopping Estimation for Dam-Break Induced Floods via AE-Enhanced CatBoost and TreeSHAP

Abstract

1. Introduction

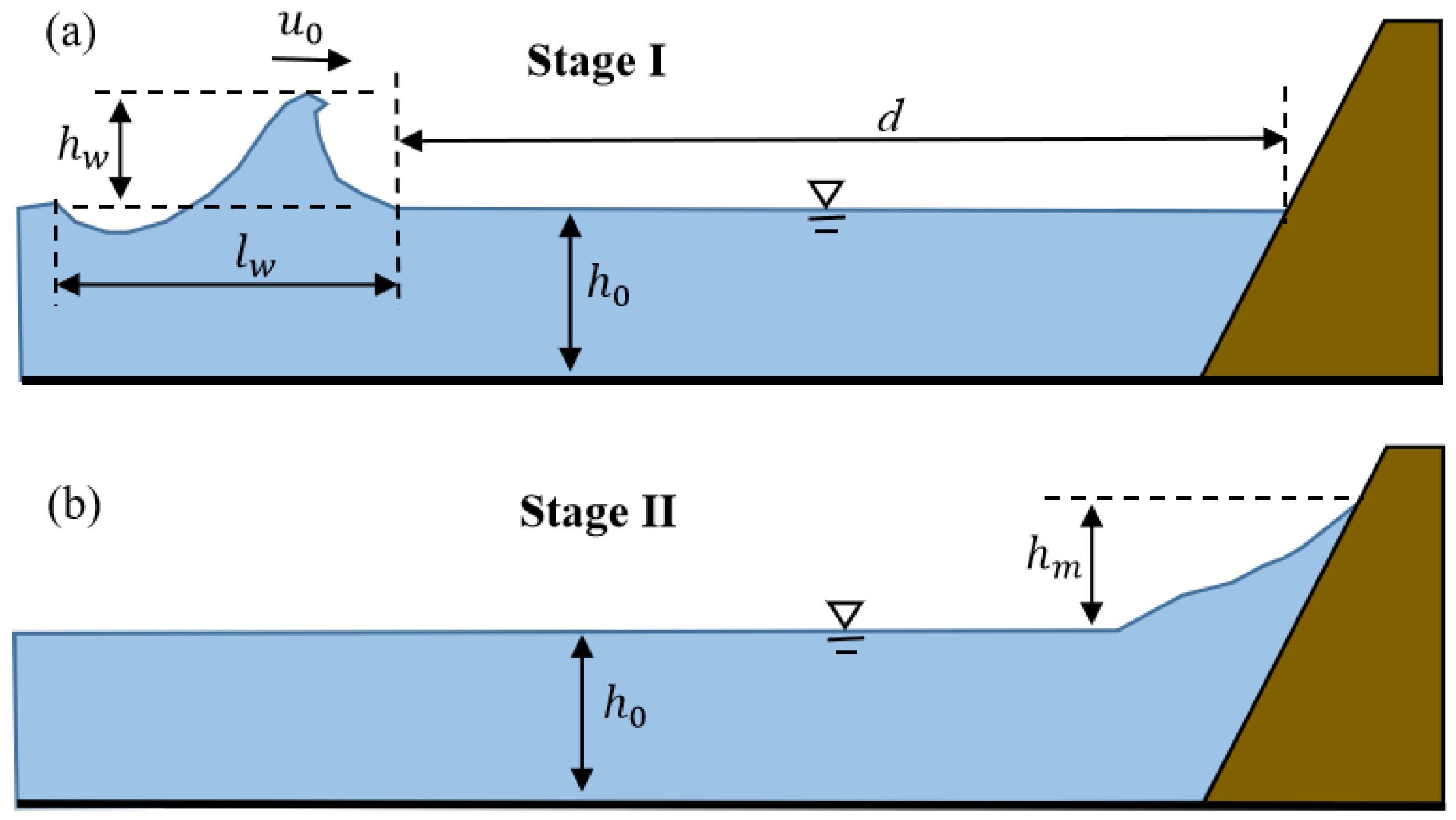

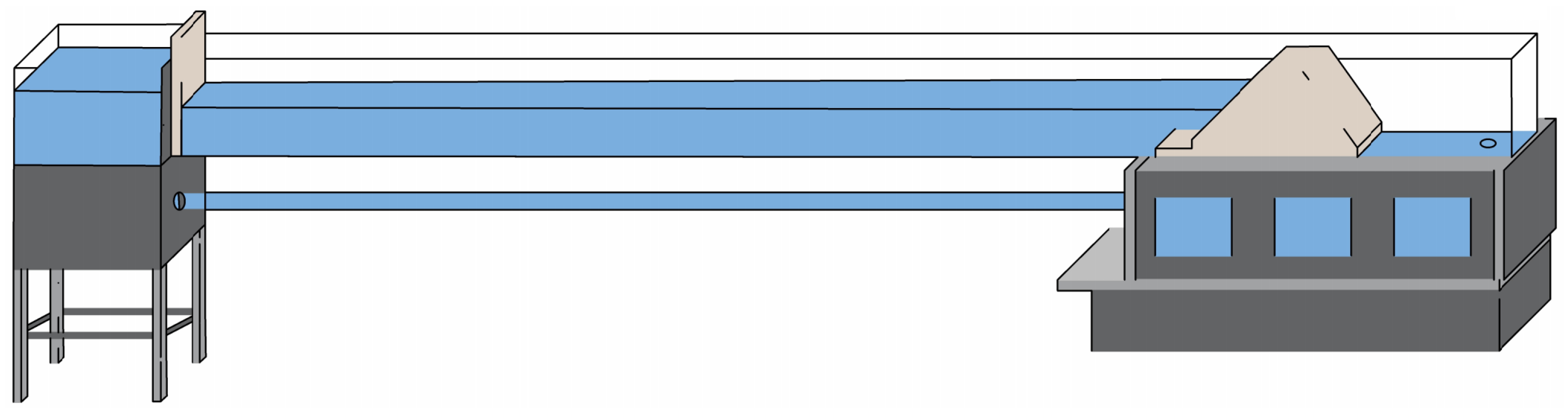

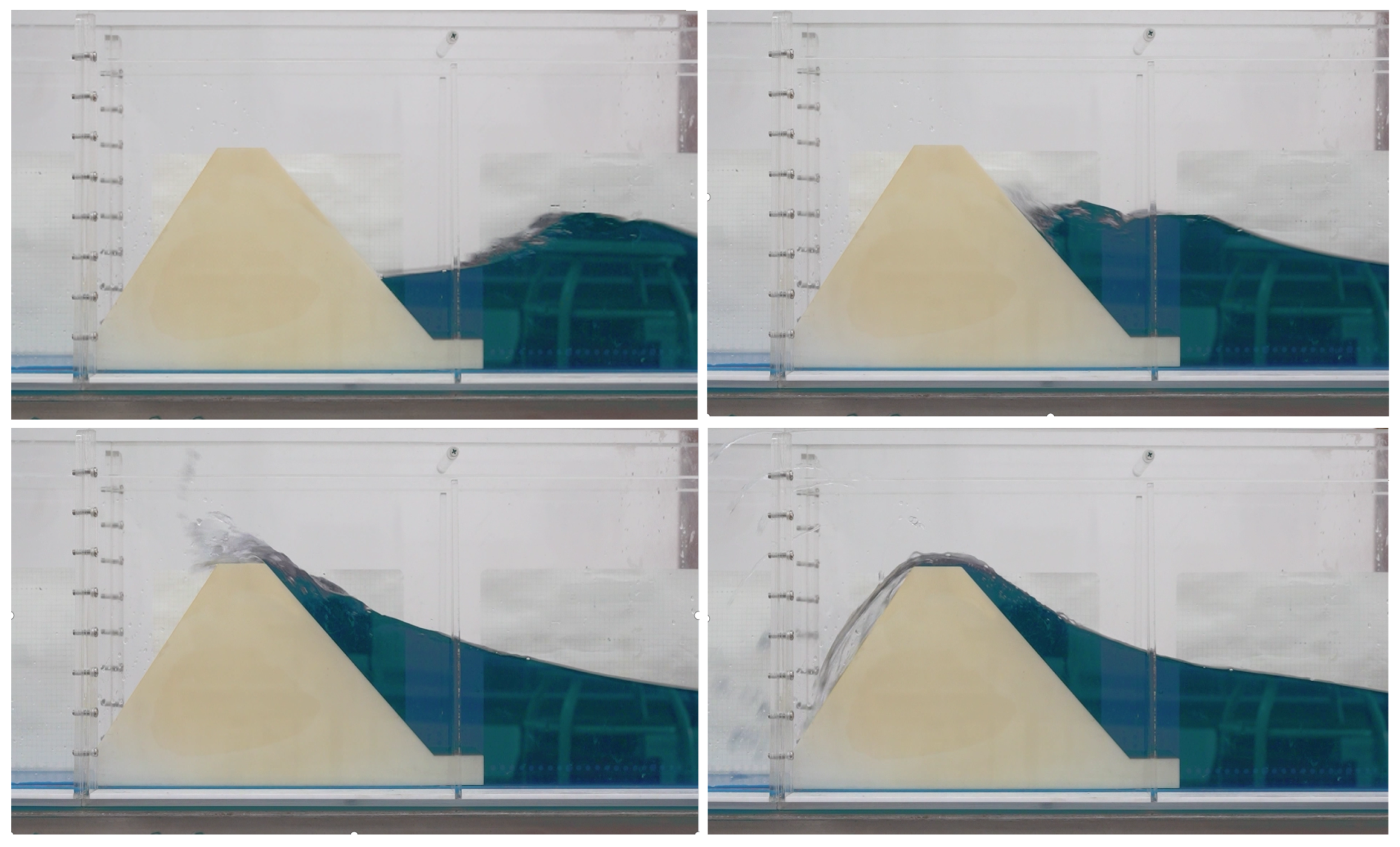

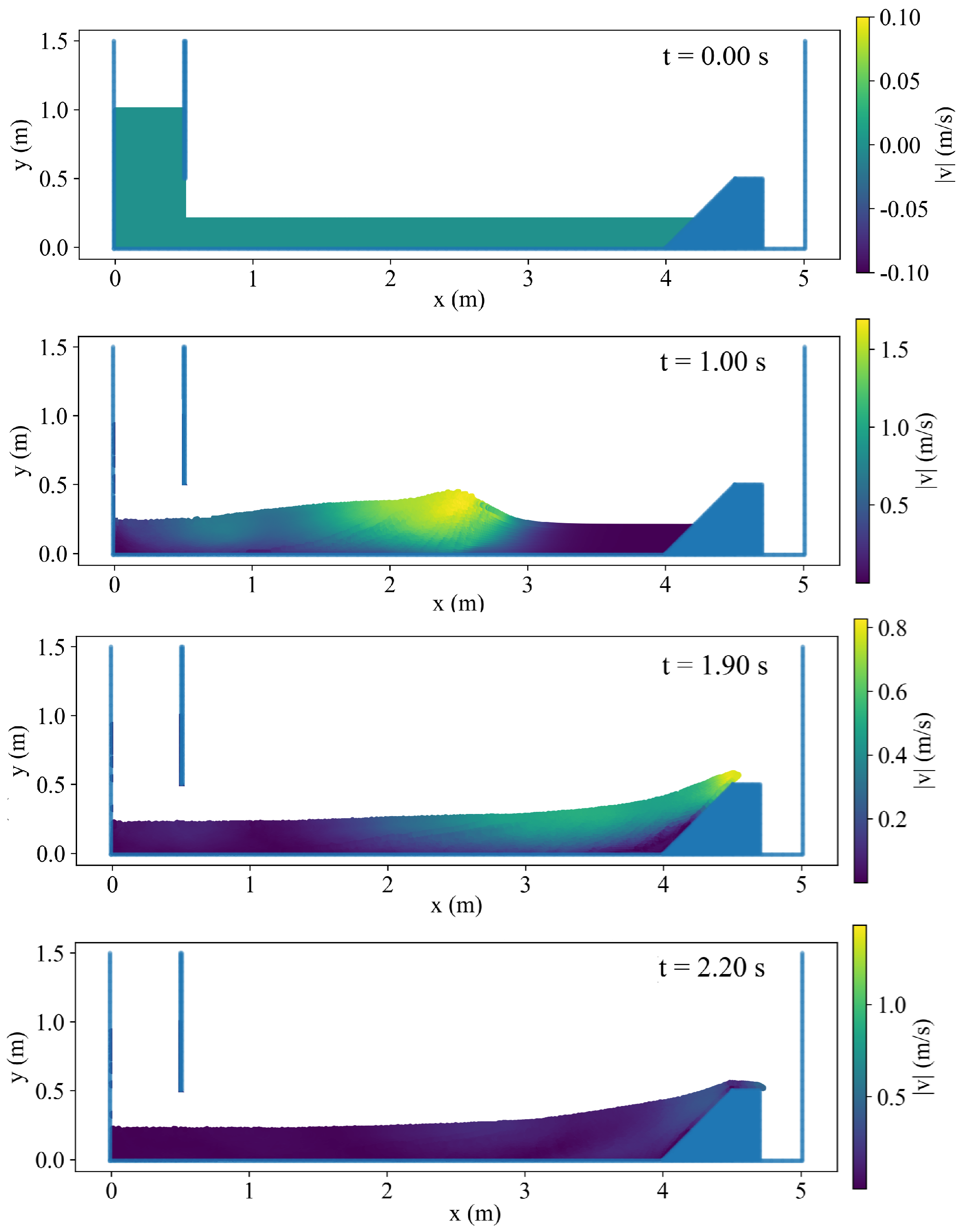

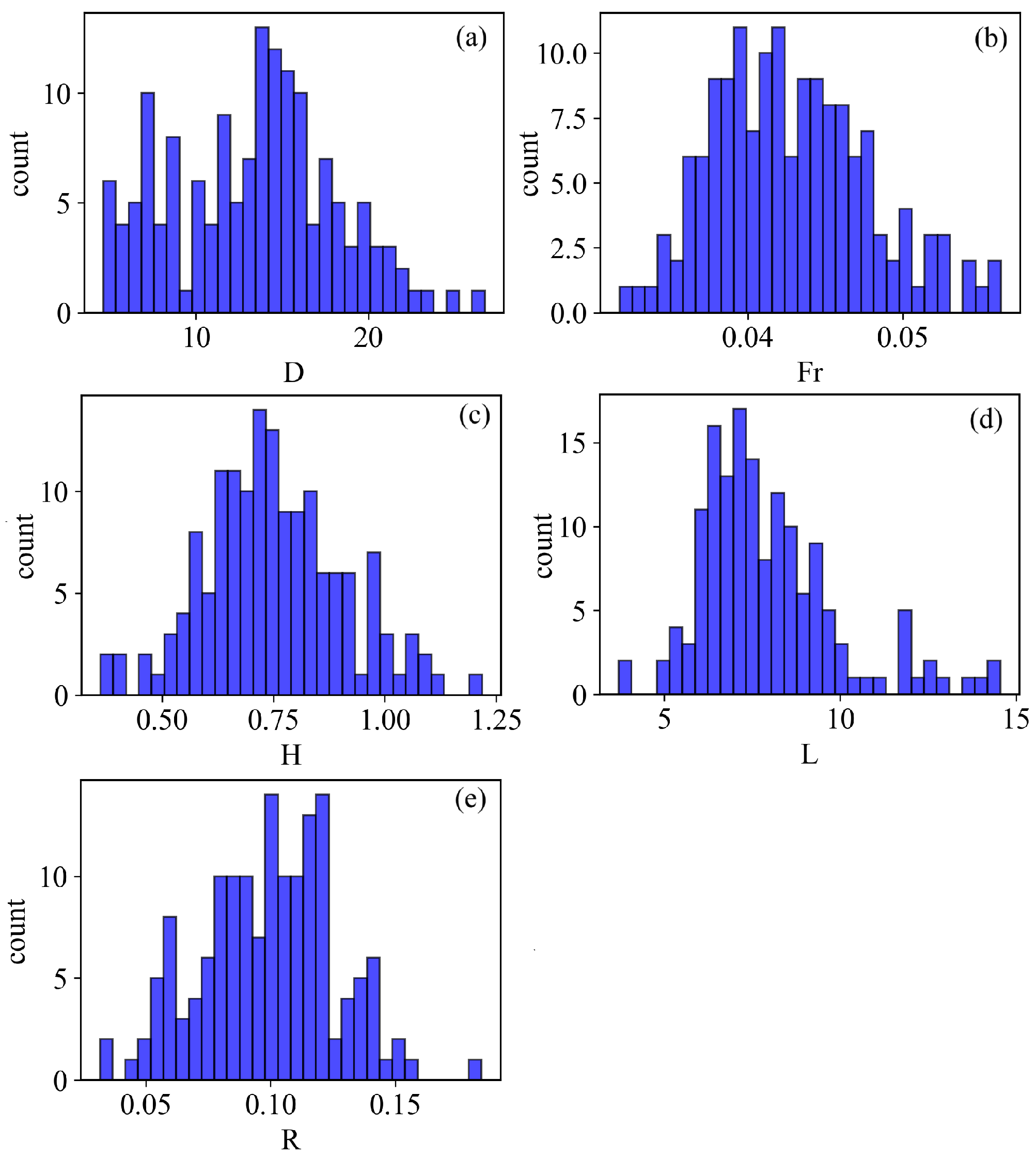

2. Dataset

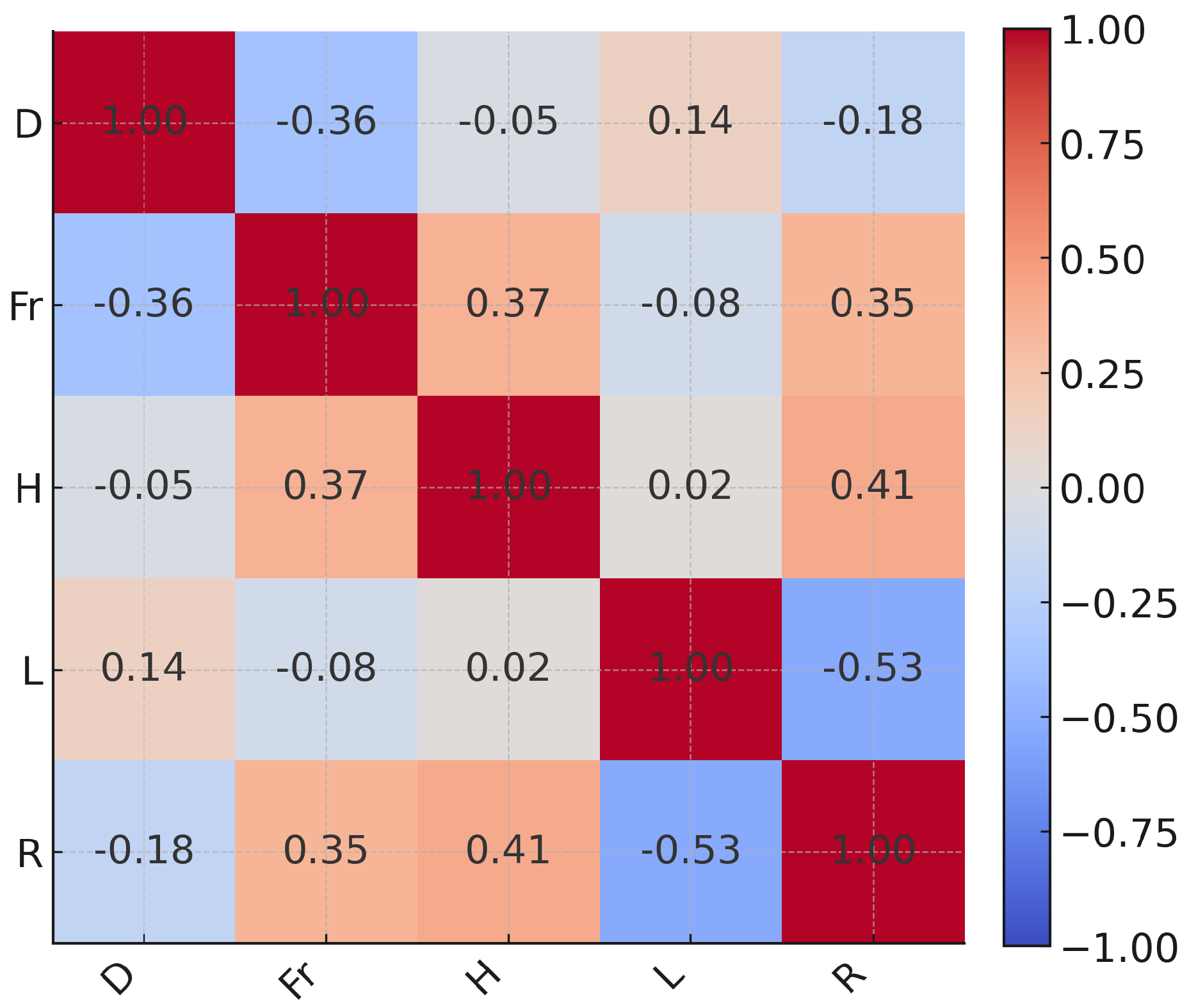

2.1. Variables and Dimensionless Analysis

2.2. Data Generation

3. Methods

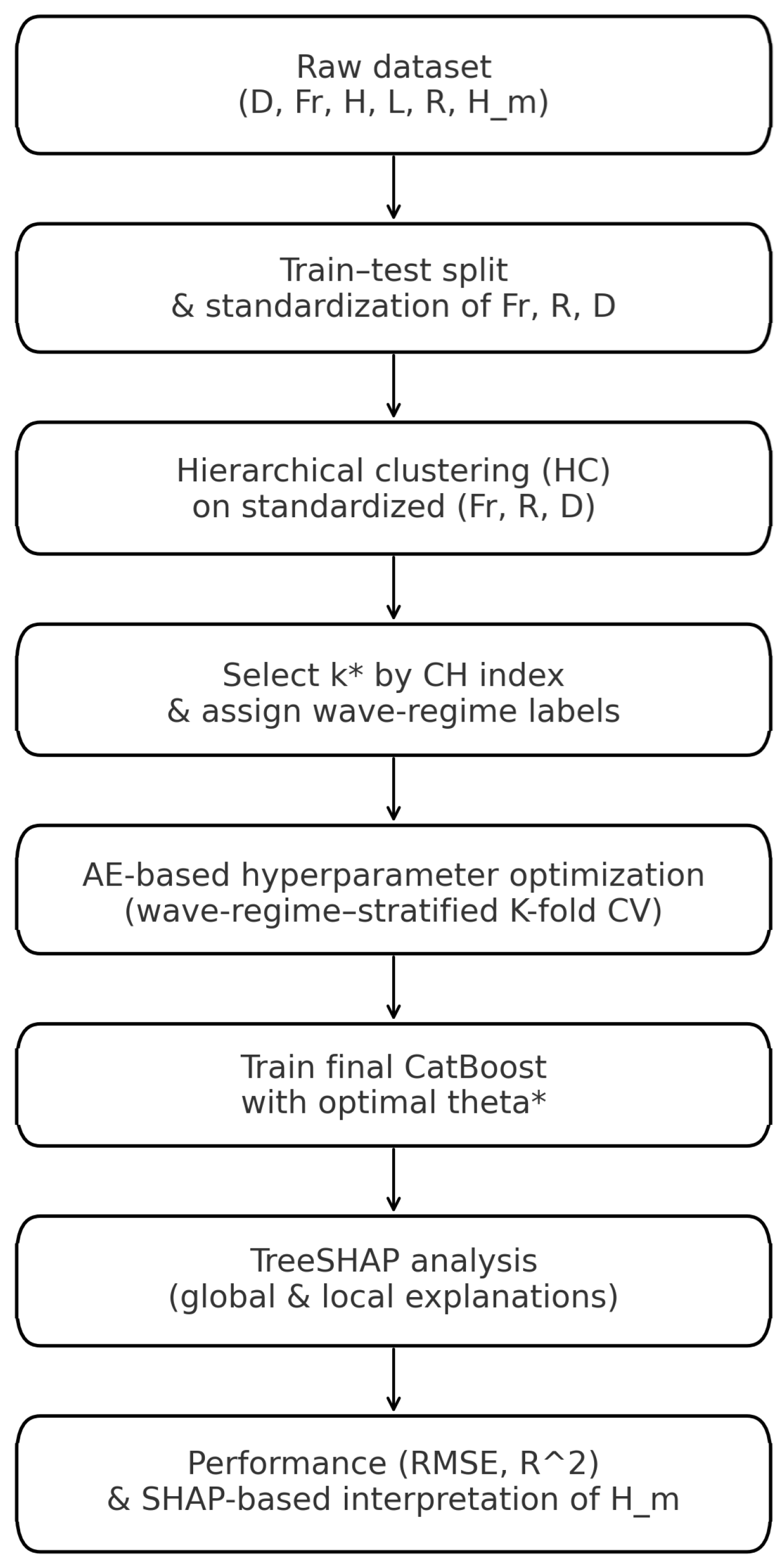

3.1. Modeling Framework

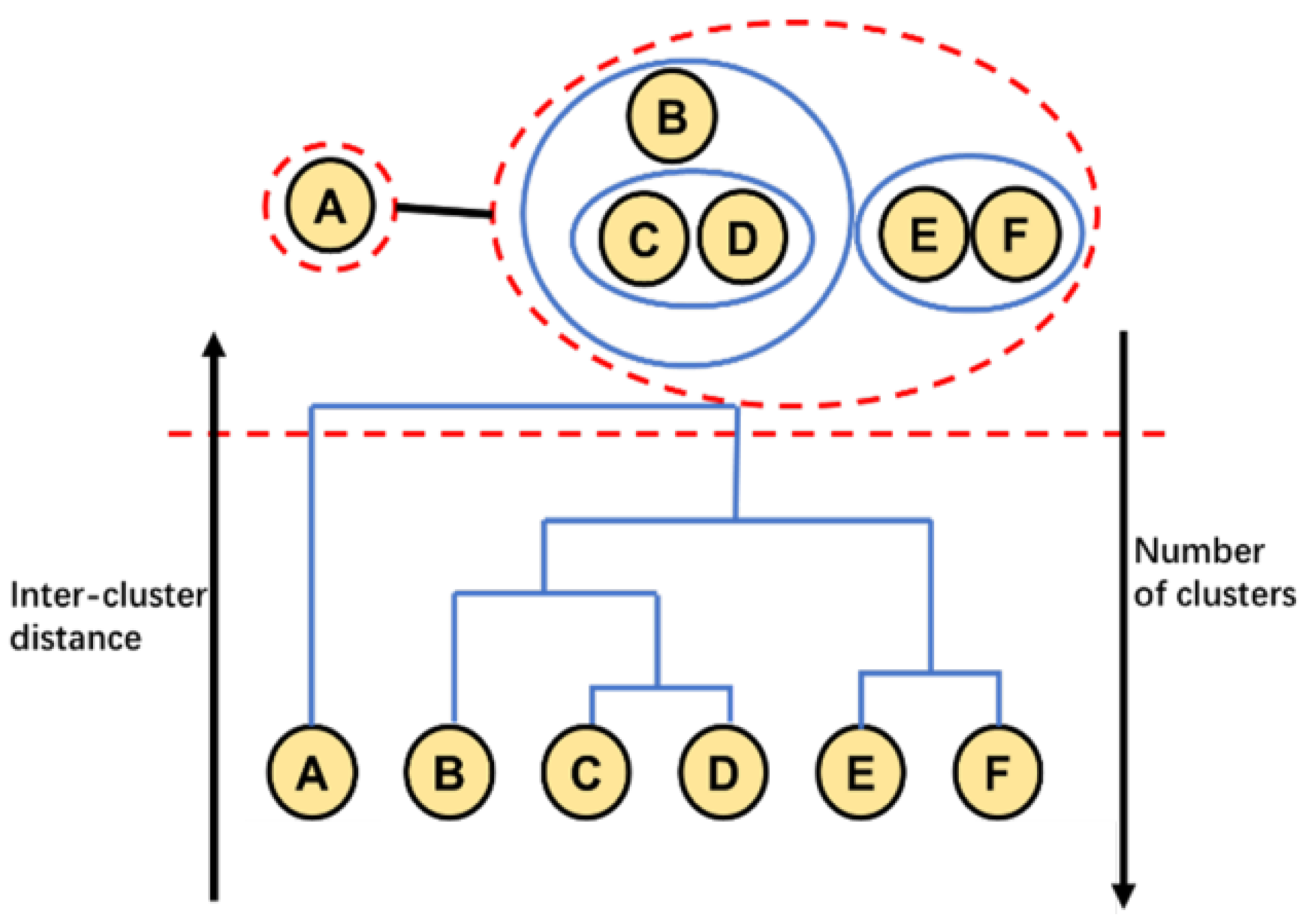

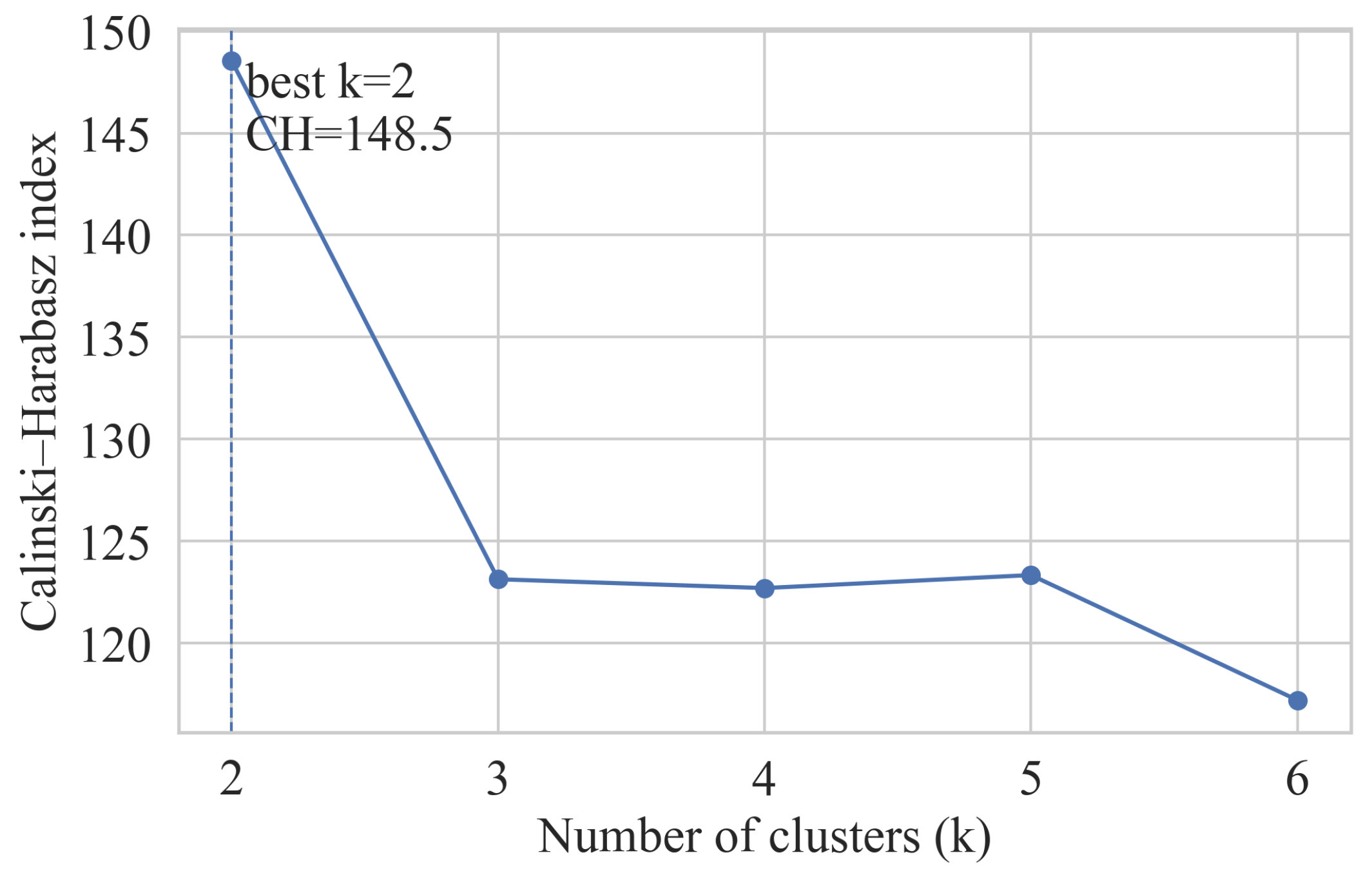

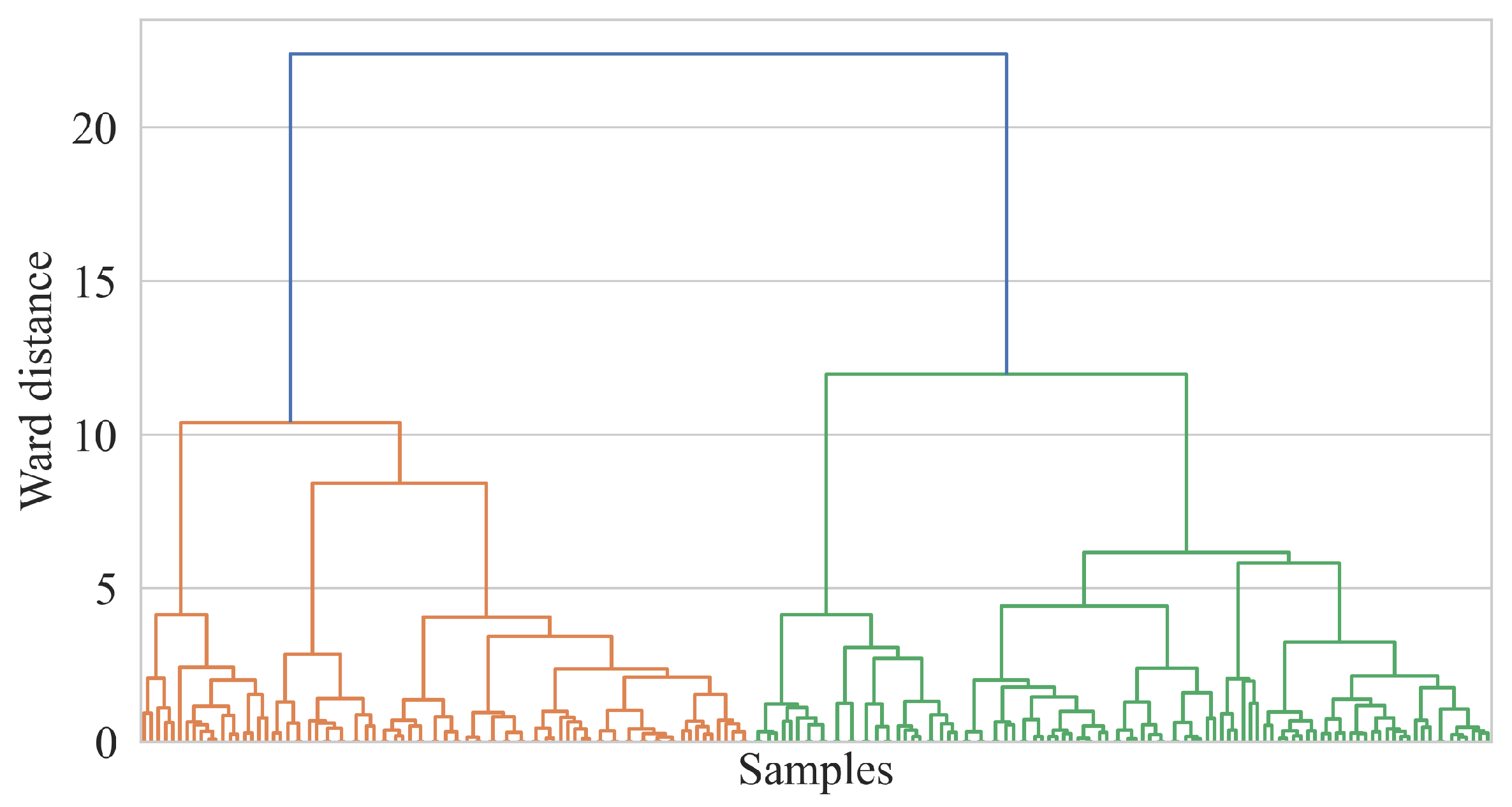

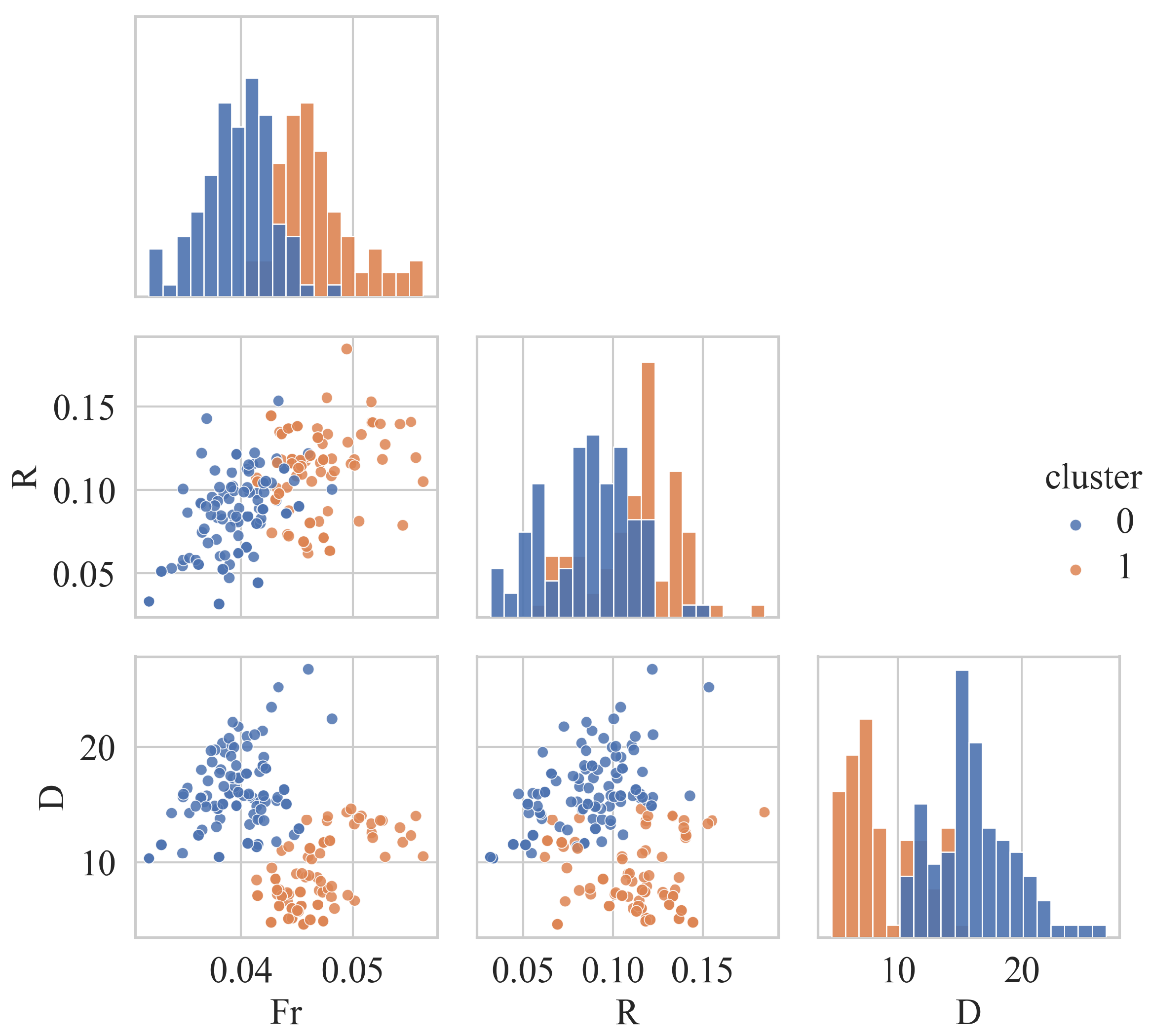

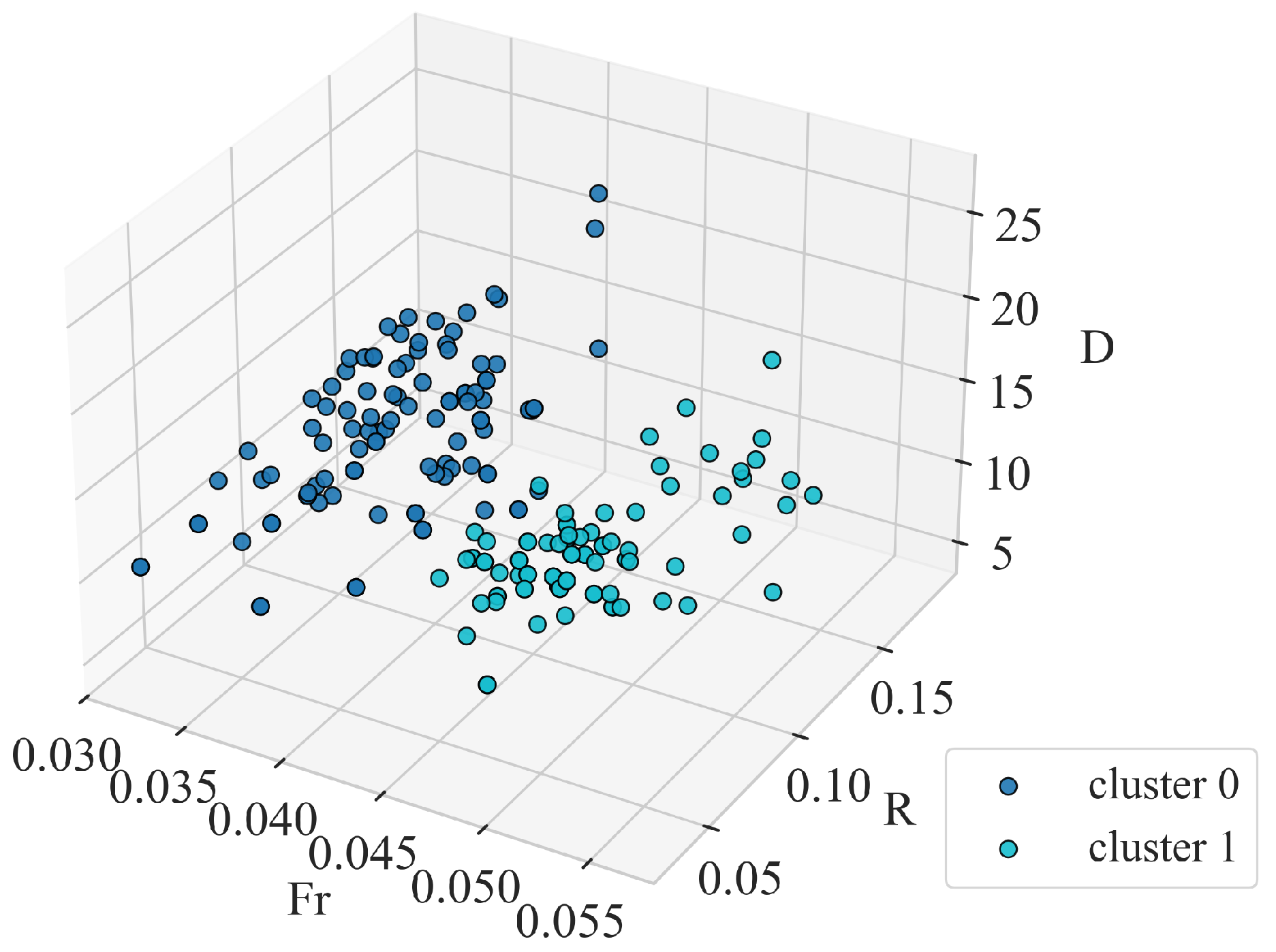

3.2. Hierarchical Clustering

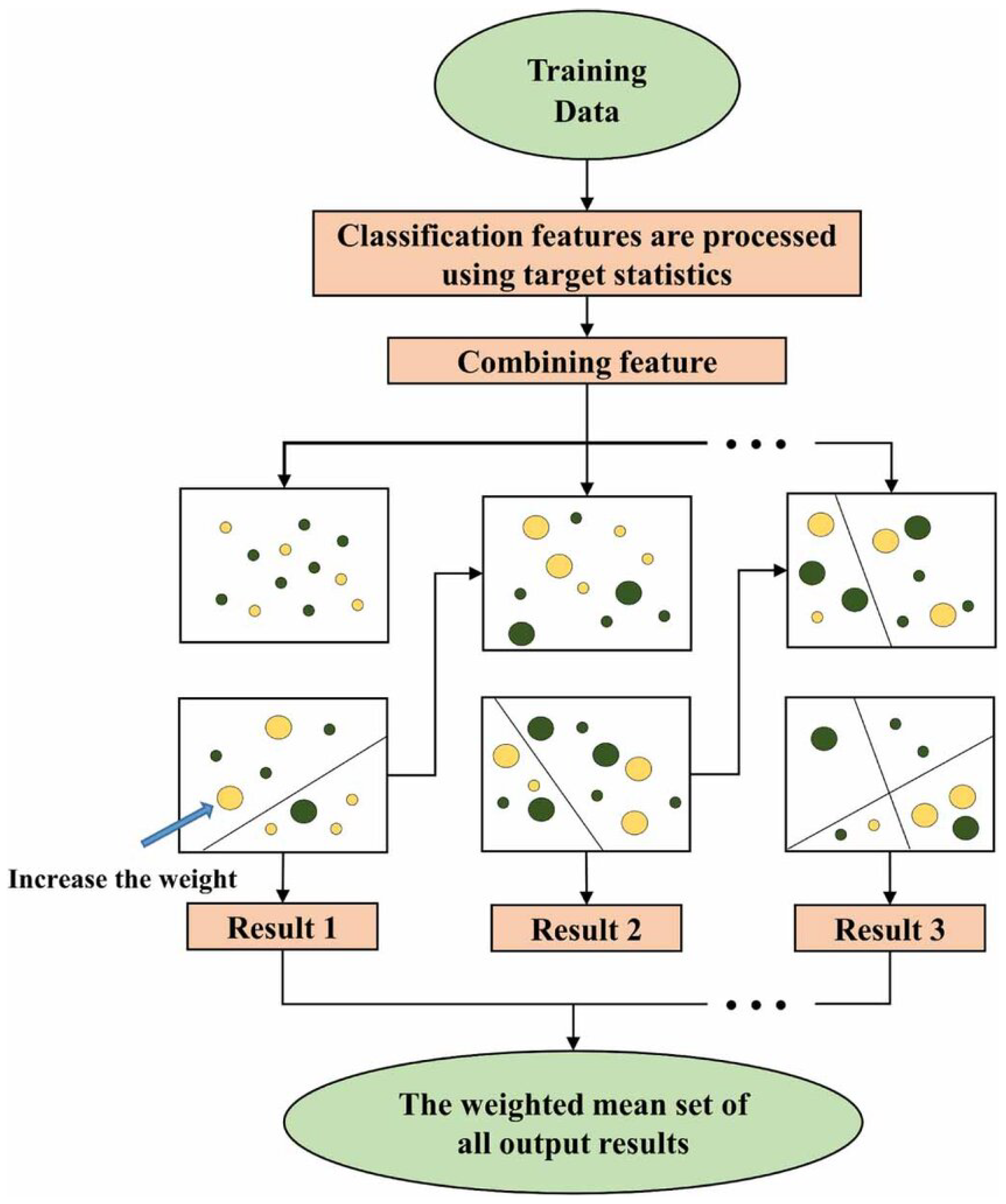

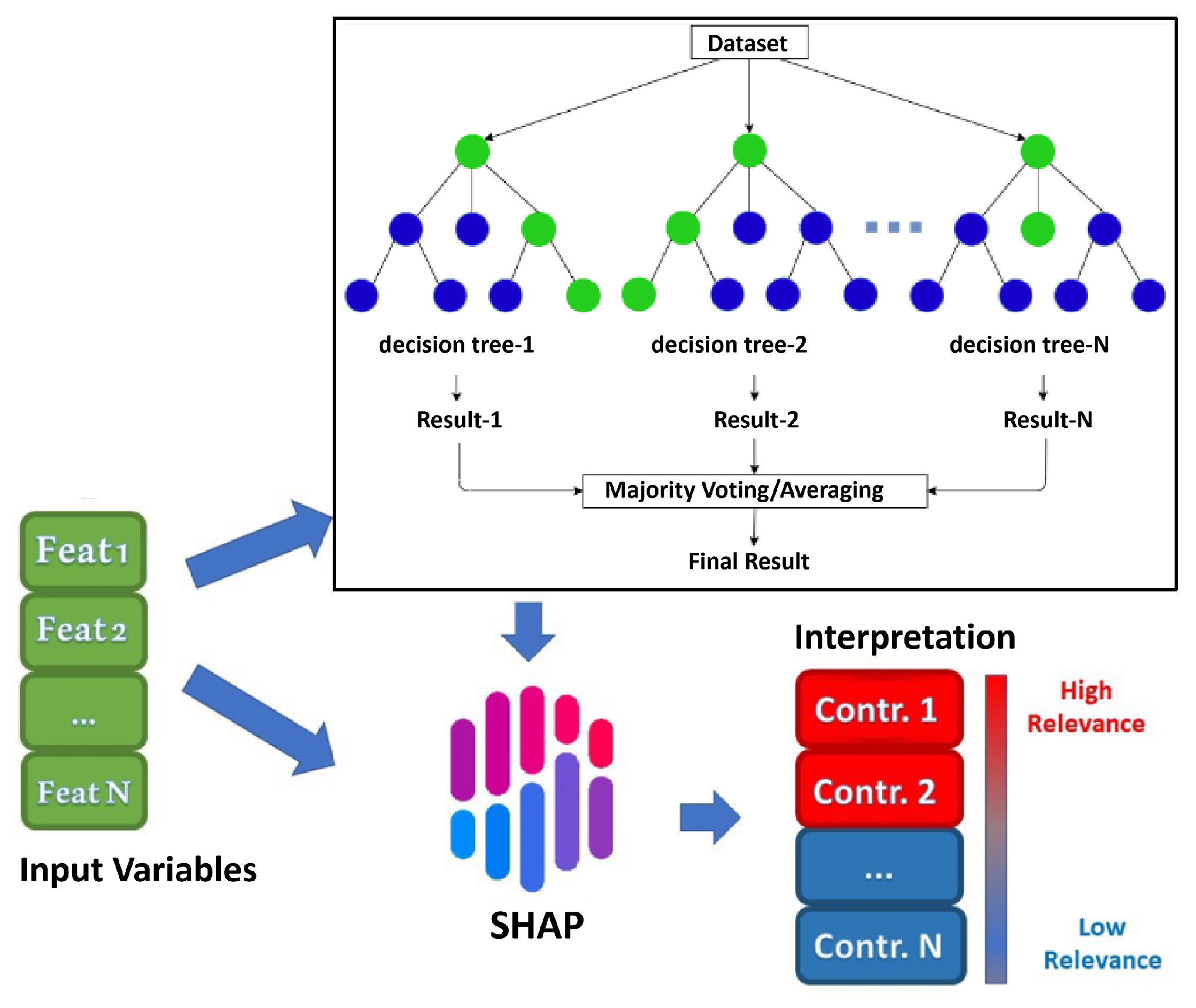

3.3. CatBoost Prediction

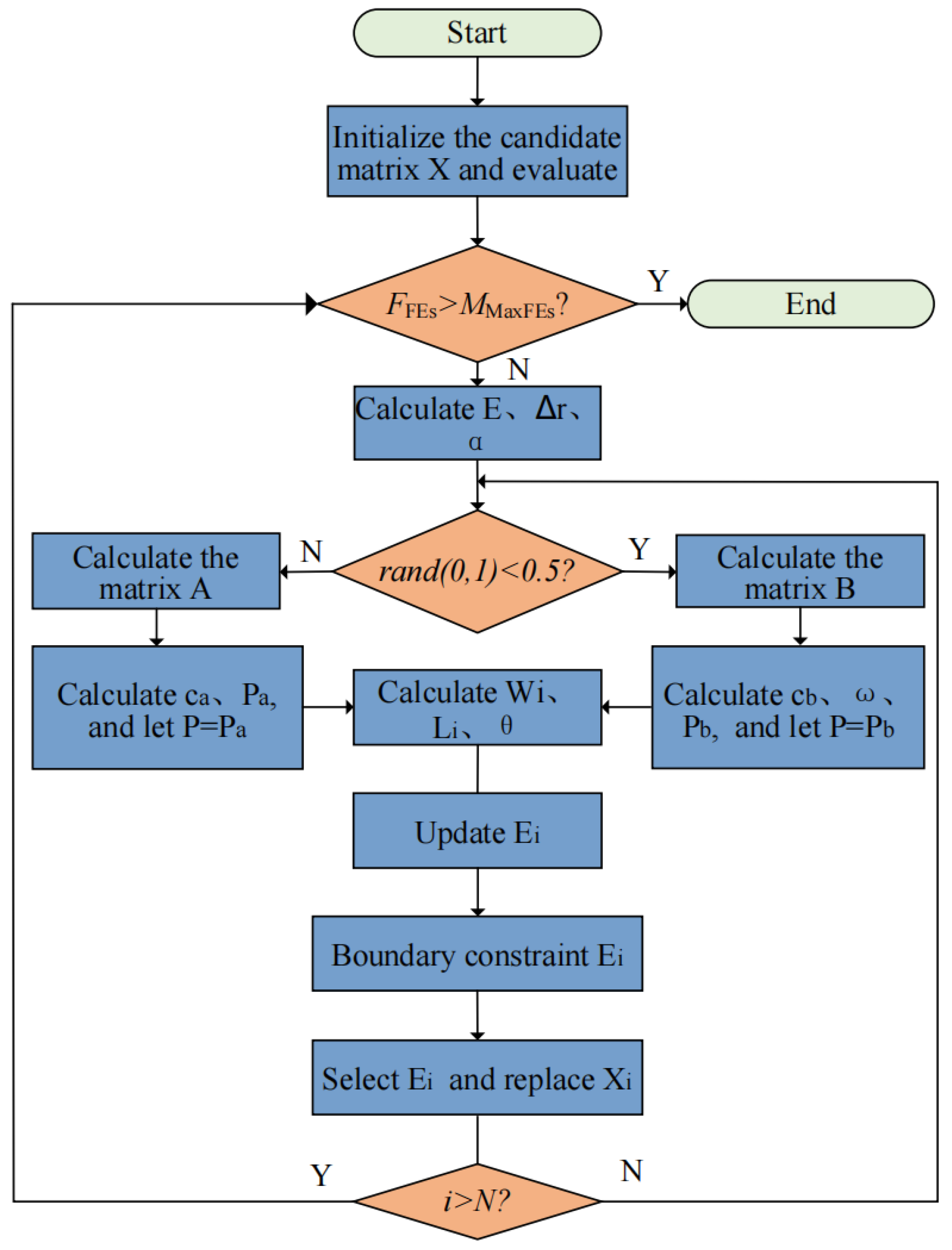

3.4. Alpha Evolution Optimization

3.5. TreeSHAP Analysis

4. Results

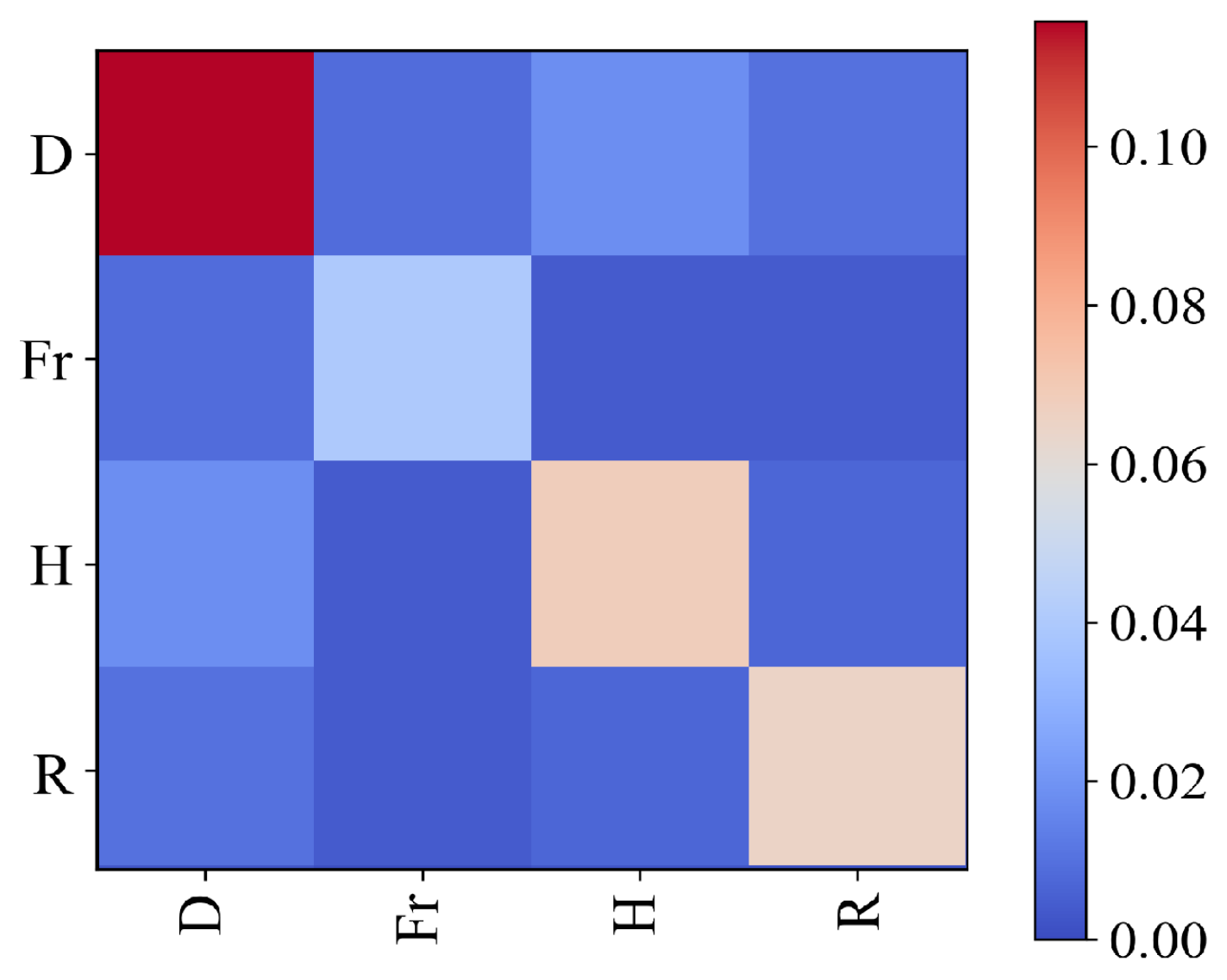

4.1. Clustering Results

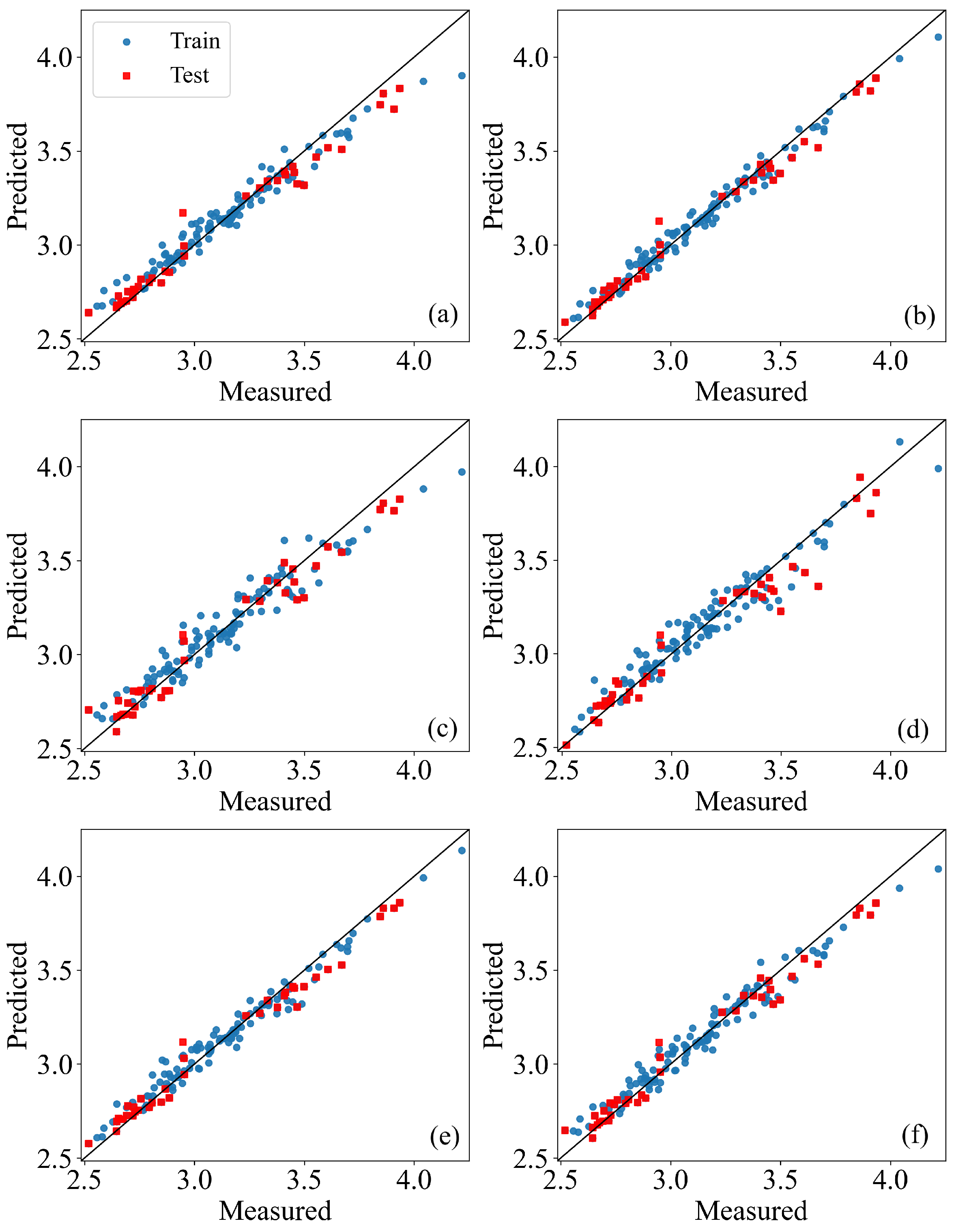

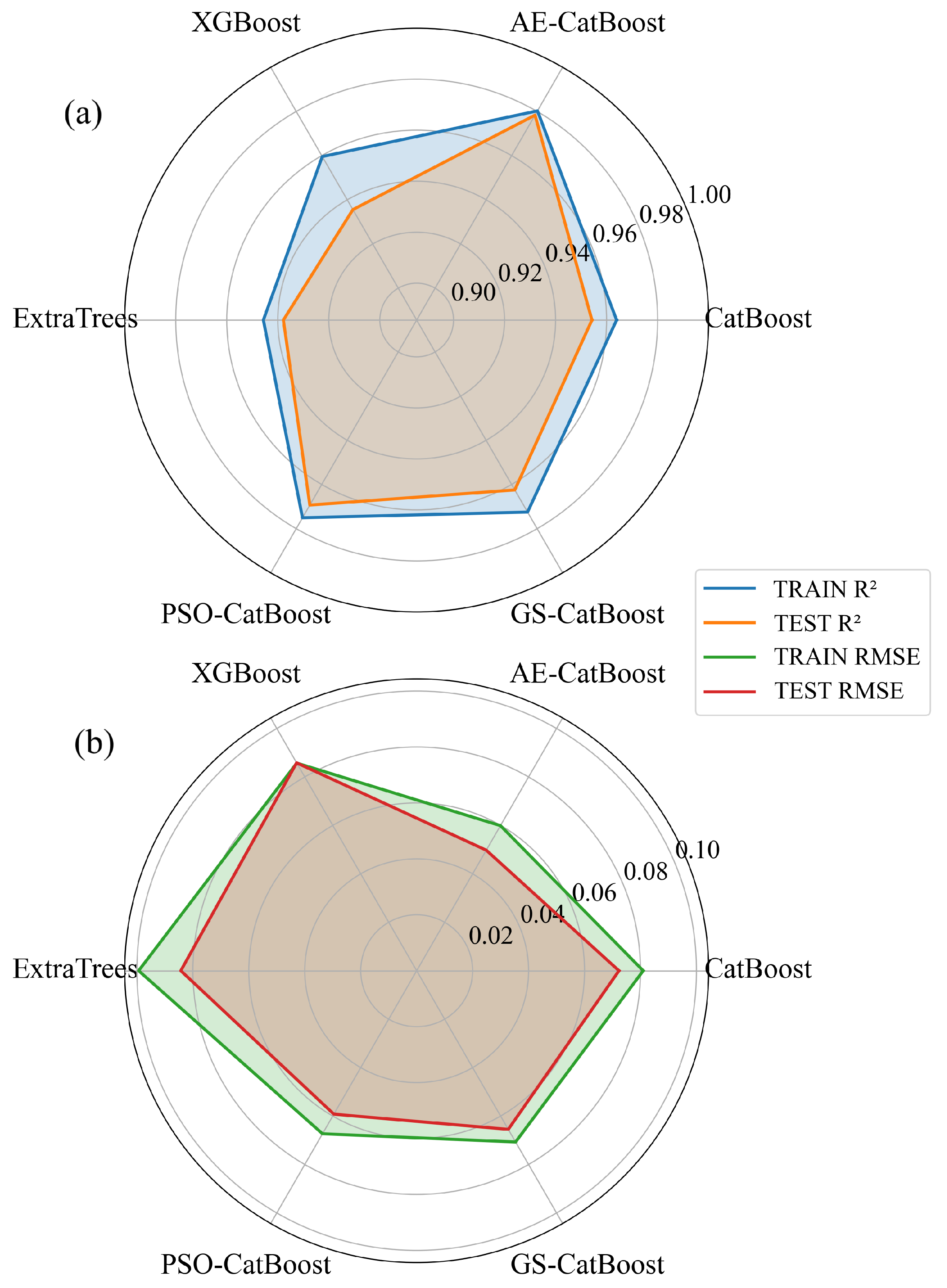

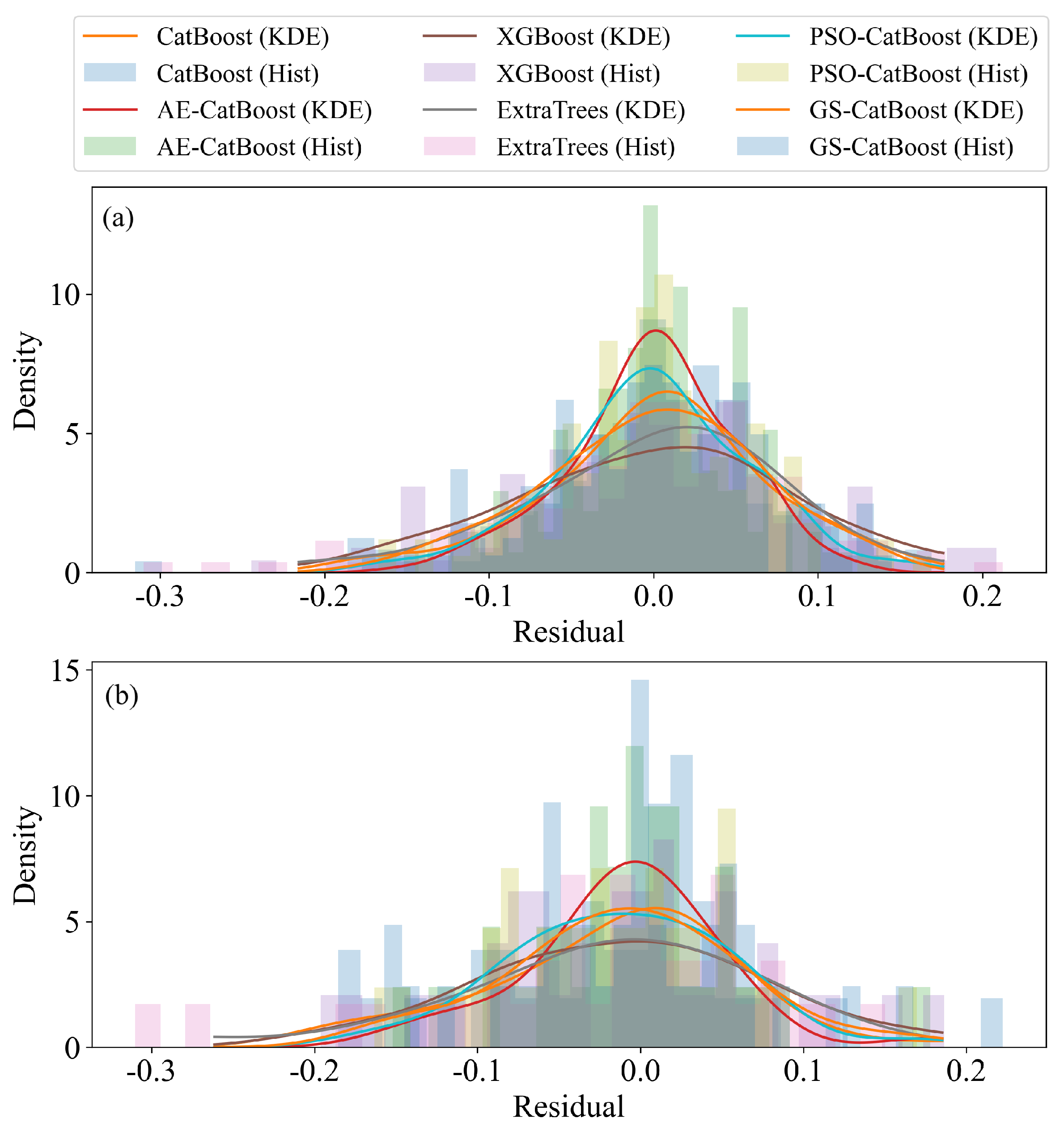

4.2. Prediction Results

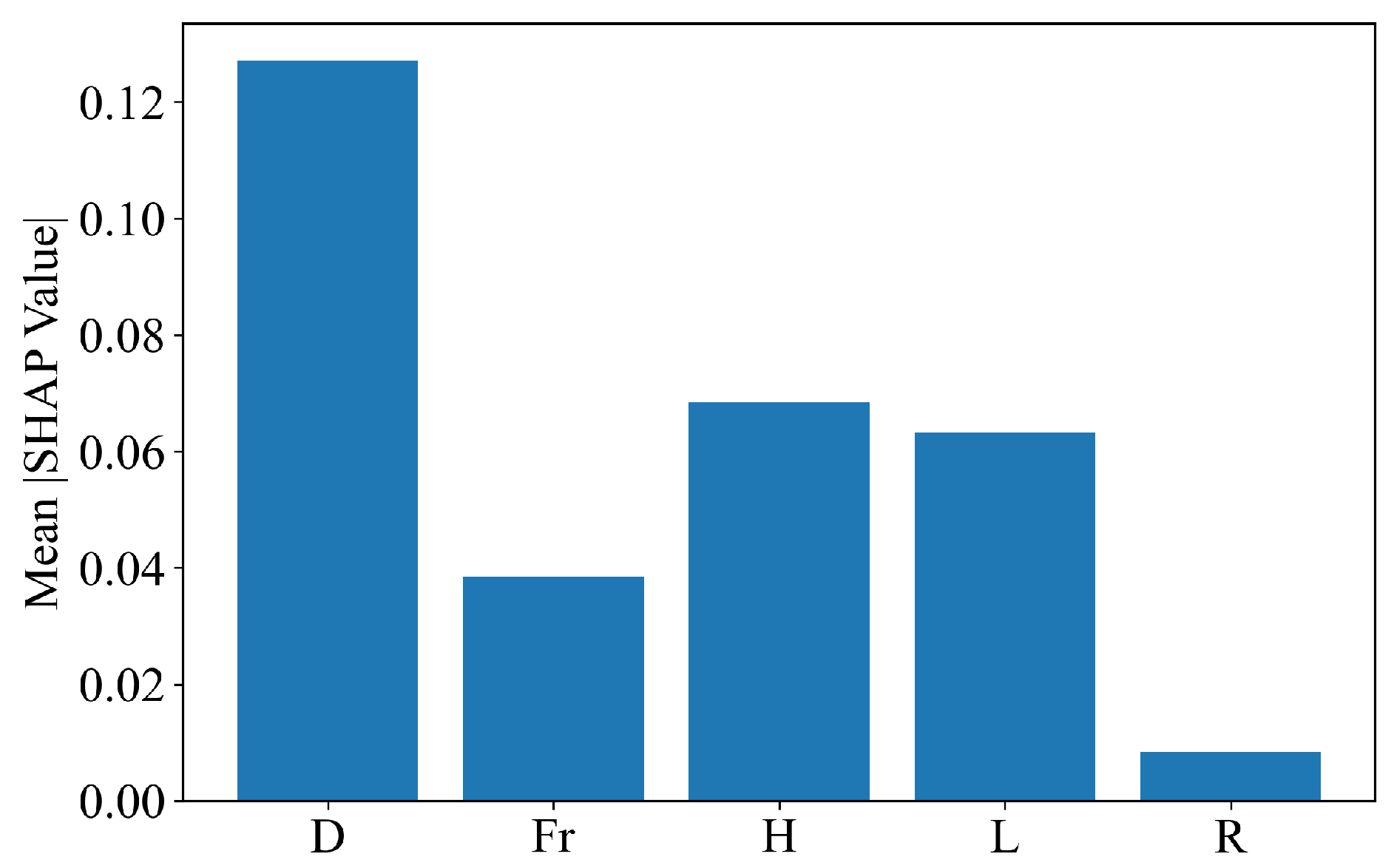

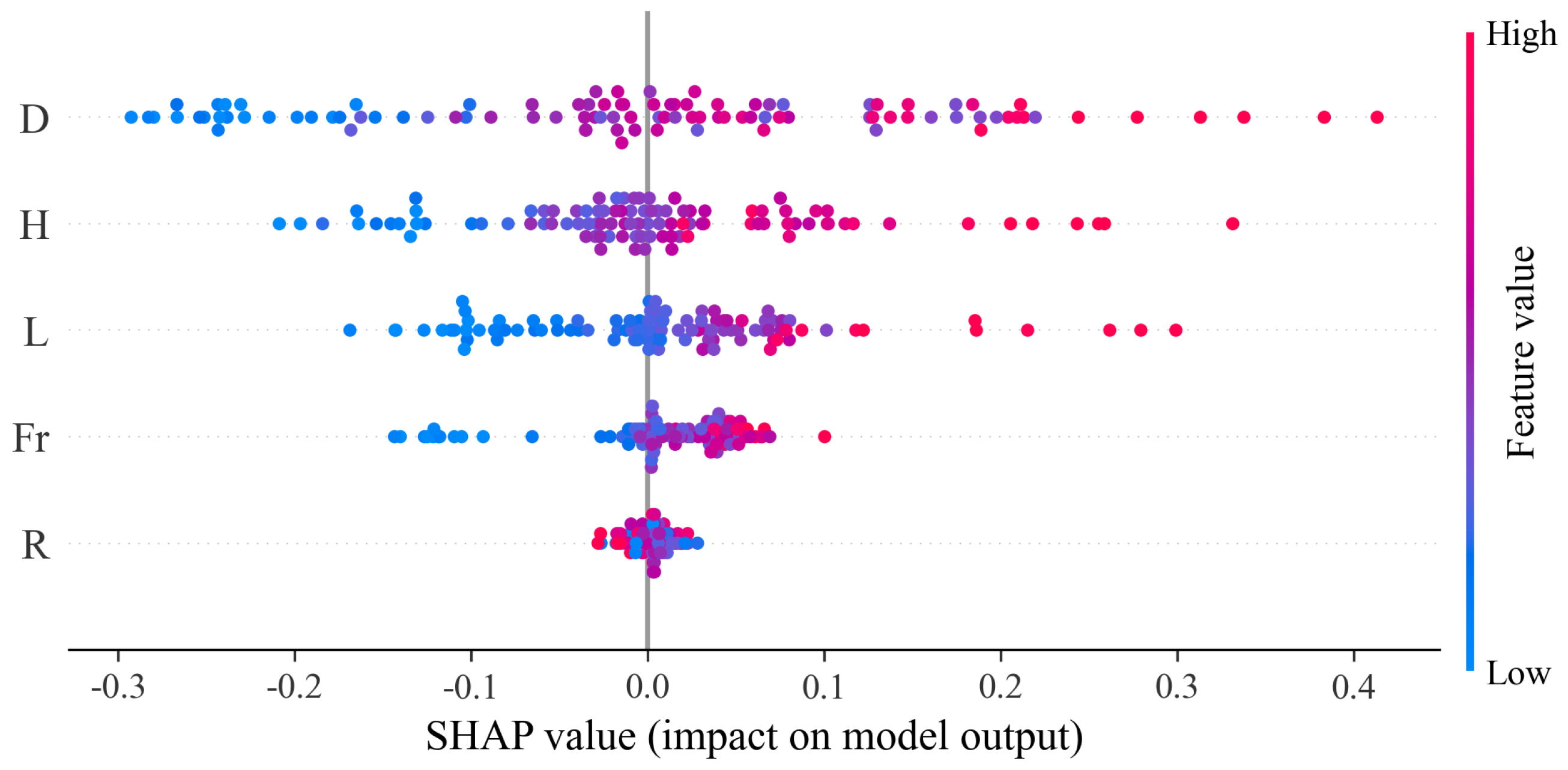

4.3. TreeSHAP Analysis Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Methodological Contribution

5.2. Physics-Consistent Interpretability

5.3. Implications for Practice

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Pseudocode of the Proposed Modeling Procedure

| Algorithm 1 HC–AE-CatBoost–SHAP pseudocode |

|

References

- Saville, T., Jr. Wave run-up on shore structures. J. Waterw. Harb. Div. 1956, 82, 925-1–925-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mather, A.; Stretch, D.; Garland, G. Predicting extreme wave run-up on natural beaches for coastal planning and management. Coast. Eng. J. 2011, 53, 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, A.; Pedersen, G.K.; Wood, D.J. An experimental study of wave run-up at a steep beach. J. Fluid Mech. 2003, 486, 161–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockdon, H.F.; Thompson, D.M.; Plant, N.G.; Long, J.W. Evaluation of wave runup predictions from numerical and parametric models. Coast. Eng. 2014, 92, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peramuna, P.; Neluwala, N.; Wijesundara, K.; DeSilva, S.; Venkatesan, S.; Dissanayake, P. Review on model development techniques for dam break flood wave propagation. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Water 2024, 11, e1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazeminezhad, M.H.; Etemad-Shahidi, A. A new method for the prediction of wave runup on vertical piles. Coast. Eng. 2015, 98, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titov, V.V.; Synolakis, C.E. Numerical modeling of tidal wave runup. J. Waterw. Port Coast. Ocean Eng. 1998, 124, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, R.C.; Hanif Chaudhry, M. A wave propagation model for two-dimensional dam-break flows. J. Hydraul. Res. 1992, 30, 467–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybkin, A.; Pelinovsky, E.; Didenkulova, I. Nonlinear wave run-up in bays of arbitrary cross-section: Generalization of the Carrier–Greenspan approach. J. Fluid Mech. 2014, 748, 416–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Zhang, J.; Hu, Y.; Ancey, C. Temporal Prediction of Landslide-Generated Waves Using a Theoretical-Statistical Combined Method. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paprotny, D.; Andrzejewski, P.; Terefenko, P.; Furmańczyk, K. Application of empirical wave run-up formulas to the Polish Baltic Sea coast. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocaman, S.; Evangelista, S.; Guzel, H.; Dal, K.; Yilmaz, A.; Viccione, G. Experimental and numerical investigation of 3d dam-break wave propagation in an enclosed domain with dry and wet bottom. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Cox, D.T. Empirical wave run-up formula for wave, storm surge and berm width. Coast. Eng. 2016, 115, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aureli, F.; Dazzi, S.; Maranzoni, A.; Mignosa, P.; Vacondio, R. Experimental and numerical evaluation of the force due to the impact of a dam-break wave on a structure. Adv. Water Resour. 2015, 76, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppikofer, T.; Hermanns, R.L.; Roberts, N.J.; Böhme, M. SPLASH: Semi-empirical prediction of landslide-generated displacement wave run-up heights. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 2019, 477, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Yang, W.; Qin, S.; Li, Q.; Yang, B. Numerical study on characteristics of dam-break wave. Ocean Eng. 2018, 159, 358–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girimaji, S.S. Partially-averaged Navier-Stokes model for turbulence: A Reynolds-averaged Navier-Stokes to direct numerical simulation bridging method. J. Appl. Mech. 2006, 73, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haltas, I.; Elçi, S.; Tayfur, G. Numerical simulation of flood wave propagation in two-dimensions in densely populated urban areas due to dam break. Water Resour. Manag. 2016, 30, 5699–5721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piomelli, U. Large-eddy simulation: Achievements and challenges. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 1999, 35, 335–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, D.; Andriolo, U.; Neves, M.G. Advances in wave run-up measurement techniques. In Advances on Testing and Experimentation in Civil Engineering: Geotechnics, Transportation, Hydraulics and Natural Resources; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 283–297. [Google Scholar]

- Muraki, Y. Field Observations of Wave Pressure, Wave Run-Up, and Oscillation of Breakwater. In Coastal Engineering 1966; American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE): Reston, VA, USA, 1966; pp. 302–321. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, C.; Sueyoshi, M. Numerical simulation and experiment on dam break problem. J. Mar. Sci. Appl. 2010, 9, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casella, E.; Rovere, A.; Pedroncini, A.; Mucerino, L.; Casella, M.; Cusati, L.A.; Vacchi, M.; Ferrari, M.; Firpo, M. Study of wave runup using numerical models and low-altitude aerial photogrammetry: A tool for coastal management. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2014, 149, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangoz, H.O.; Anilan, T. Two-dimensional modeling of flood wave propagation in residential areas after a dam break with application of diffusive and dynamic wave approaches. Nat. Hazards 2022, 110, 429–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Gu, C.; Wei, B.; Qin, X.; Xu, W. A high-performance displacement prediction model of concrete dams integrating signal processing and multiple machine learning techniques. Appl. Math. Model. 2022, 112, 436–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghosoun, A.; Gumus, V.; Seaid, M.; Simsek, O. Predicting morphodynamics in dam-break flows using combined machine learning and numerical modelling. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2025, 11, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Huang, S.; Qiu, H.; Xu, Y.P.; Teegavarapu, R.S.; Guo, Y.; Nie, H.; Xie, H.; Xie, J.; Shao, Y.; et al. Assessment of ecological flow in river basins at a global scale: Insights on baseflow dynamics and hydrological health. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 178, 113868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, K.; Sheikh Khozani, Z.; Hatamiafkoueieh, J. Prediction of embankments dam break peak outflow: A comparison between empirical equations and ensemble-based machine learning algorithms. Nat. Hazards 2023, 118, 1989–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, H.; Fan, Y.; Meng, Z.; Liu, D.; Pan, S. Optimization of Water Quantity Allocation in Multi-Source Urban Water Supply Systems Using Graph Theory. Water 2025, 17, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Xu, B.; Qiu, H.; Huang, S.; Teegavarapu, R.S.; Xu, Y.P.; Guo, Y.; Nie, H.; Xie, H. Adaptive assessment of reservoir scheduling to hydrometeorological comprehensive dry and wet condition evolution in a multi-reservoir region of southeastern China. J. Hydrol. 2025, 648, 132392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Hu, Y.; Jiang, S.; Zheng, S.; Zhang, J.; Yuan, Z.; Yao, S. Slope Deformation Prediction Combining Particle Swarm Optimization-Based Fractional-Order Grey Model and K-Means Clustering. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, H.E.; Gharabaghi, B.; Bonakdari, H.; Robertson, B.; Atkinson, A.L.; Baldock, T.E. Prediction of wave runup on beaches using Gene-Expression Programming and empirical relationships. Coast. Eng. 2019, 144, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, K.; Khan, H.; Cho, Y.S.; Hong, S.H. Incident wave run-up prediction using the response surface methodology and neural networks. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2022, 36, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Peng, T.; Xiao, L.; Wei, H.; Li, X. Wave runup prediction for a semi-submersible based on temporal convolutional neural network. J. Ocean Eng. Sci. 2024, 9, 528–540. [Google Scholar]

- Naeini, S.S.; Snaiki, R. A physics-informed machine learning model for time-dependent wave runup prediction. Ocean Eng. 2024, 295, 116986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xiao, L.; Wei, H.; Li, D.; Li, X. A comparative study of LSTM and temporal convolutional network models for semisubmersible platform wave runup prediction. J. Offshore Mech. Arct. Eng. 2025, 147, 011202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Meng, Z.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Yao, J.; Li, X.; Qin, P.; Liu, X.; Cheng, C. Prediction of Seawater Intrusion Run-Up Distance Based on K-Means Clustering and ANN Model. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liang, Q.; Hancock, J.T.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. Feature selection strategies: A comparative analysis of SHAP-value and importance-based methods. J. Big Data 2024, 11, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Broeck, G.; Lykov, A.; Schleich, M.; Suciu, D. On the tractability of SHAP explanations. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2022, 74, 851–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtagh, F.; Contreras, P. Algorithms for hierarchical clustering: An overview. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2012, 2, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, P.; Murtagh, F. Hierarchical clustering. In Handbook of Cluster Analysis; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015; pp. 103–123. [Google Scholar]

- Ran, X.; Xi, Y.; Lu, Y.; Wang, X.; Lu, Z. Comprehensive survey on hierarchical clustering algorithms and the recent developments. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 8219–8264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokhorenkova, L.; Gusev, G.; Vorobev, A.; Dorogush, A.V.; Gulin, A. CatBoost: Unbiased boosting with categorical features. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1706.09516. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, H.; Zhang, Q. Alpha evolution: An efficient evolutionary algorithm with evolution path adaptation and matrix generation. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 137, 109202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inan, M.S.K.; Rahman, I. Explainable AI integrated feature selection for landslide susceptibility mapping using TreeSHAP. SN Comput. Sci. 2023, 4, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopanja, M.; Hačko, S.; Brdar, S.; Savić, M. Cost-sensitive tree SHAP for explaining cost-sensitive tree-based models. Comput. Intell. 2024, 40, e12651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Extracting spatial effects from machine learning model using local interpretation method: An example of SHAP and XGBoost. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2022, 96, 101845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, H.; Fan, Y.; Meng, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L. Physics-Consistent Overtopping Estimation for Dam-Break Induced Floods via AE-Enhanced CatBoost and TreeSHAP. Water 2026, 18, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010042

Li H, Fan Y, Meng Z, Zhang X, Zhang J, Wang L. Physics-Consistent Overtopping Estimation for Dam-Break Induced Floods via AE-Enhanced CatBoost and TreeSHAP. Water. 2026; 18(1):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010042

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Hanze, Yazhou Fan, Zhenzhu Meng, Xinhai Zhang, Jinxin Zhang, and Liang Wang. 2026. "Physics-Consistent Overtopping Estimation for Dam-Break Induced Floods via AE-Enhanced CatBoost and TreeSHAP" Water 18, no. 1: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010042

APA StyleLi, H., Fan, Y., Meng, Z., Zhang, X., Zhang, J., & Wang, L. (2026). Physics-Consistent Overtopping Estimation for Dam-Break Induced Floods via AE-Enhanced CatBoost and TreeSHAP. Water, 18(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010042