Abstract

The effectiveness of manmade wetlands with four different macrophyte species (Arundo donax, Typha latifolia, Pistia stratiotes, and Eichhornia crassipes) in treating wastewater from the paper recycling industry, located in the Hattar Industrial Estate in Haripur, is reported. The findings show that each plant species has distinct pollutant removal capacities, which contribute to the overall treatment effectiveness of the system. Notably, Arundo donax performed exceptionally well in lowering chemical oxygen demand (COD) from 1013 mg/L to 119.66 mg/L and nitrate levels from 79.66 mg/L to 10.66 mg/L. In contrast, T. latifolia was successful in reducing biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) from 436 mg/L to 55 mg/L and total solids from 837.66 mg/L to 242.66 mg/L. The P. stratiotes species have high phosphate removal capacity, lowering values from 134.66 mg/L to 25.66 mg/L. RSM revealed that time, Arundo donax, and wetlands significantly enhance pollutant removal, while specific plant–treatment combinations yield variable efficiencies, highlighting synergistic effects crucial for optimal performance. Furthermore, all plant species have shown competency in removing heavy metals from effluent. This study’s findings highlight the potential of artificial wetlands as a natural and eco-friendly alternative for treating complex industrial wastewater, promoting the development of sustainable wastewater treatment methods in industrial settings.

1. Introduction

Recent innovations have had the greatest negative impact on the environment. Industrialization has contributed significantly to environmental pollution through the excessive release of harmful substances [1,2]. In terms of energy consumption, the paper industry is the world’s sixth largest generator of environmental pollution, trailing only cement, oil, textile, leather, and steel. Mechanical pulping, chemical pulping, and mechanical–chemical pulping combinations all require a large amount of fresh water and generate effluent [3]. Each ton of paper produced created 60 m3 of wastewater, which could contain harmful chlorinated chemicals, high chemical oxygen demand (COD), biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), suspended particulates, and color. Furthermore, around 11 tons of garbage are generated each year, potentially contributing to a substantial number of hazardous substances [4].

Numerous studies have shown that paper mill effluent contains heavy metals (Cd, Cu, Pb, and Ni, among others), organic materials (such as lignin), biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), chemical oxygen demand (COD), absorbable organic halogen (AOX), phytosterols, phosphorus, and extractives [5]. Because of the high pollutant content and volume of wastewater produced, advanced and high-capacity treatment systems are required [6]. Recently, membrane filtration, adsorption, and ozonation have been applied for the final discharge treatment of paper industry wastewater; however, due to persistence, some contaminants have seldom been decreased. As a result, the wastewater from this industry no longer meets local authority regulations. Consequently, removing these extremely harmful compounds from wastewater requires an efficient process [7].

Constructed wetlands (CWs) are simple and inexpensive wastewater treatment facilities that use natural processes to improve wastewater quality. These systems employ shallow (usually less than 1 m deep) beds or channels, helophytes, substrate (soil, sand, and gravels), and a diverse range of microorganisms [8]. CWs can remove inorganic materials, organic debris, hazardous chemicals, metals, and pathogens from a variety of wastewater streams [9]. Aquatic macrophytes such as Phragmites australis, Eichhornia crassipes, Typha domingensis, Panicum elephantipes, Scirupus americanus, Myriophyllum spicatum, and T. latifolia are commonly employed in artificial wetlands because they absorb pollutants directly in their tissues. These plants’ fibrous roots and rhizomes have a wide surface area, making it easier to absorb pollutants such as metals [10]. The primary variables driving the CW remediation process are sedimentation, flocculation, precipitation, complexation, oxidation and reduction, ion exchange, and phytoremediation [11]. Furthermore, pH, wastewater composition, retention period, and microbial activity all contribute significantly to treatment effectiveness [12]. The majority of CWs employ gravel, sand, soil, dirt, and crushed stone as substrates to promote plant development [13].

The purpose of this study was to assess the efficacy of a constructed wetland planted with A. donax, E. crassipes (water hyacinth), P. stratiotes (water lettuce), T. latifolia (cattail), and algae for the treatment of effluent from the paper recycling business. This study presents a novel approach to treating paper industry wastewater using constructed wetlands vegetated with A. donax, T. latifolia, P. stratiotes, and E. crassipes, marking a pioneering effort in Pakistan’s industrial wastewater management. The innovative aspect of this research lies in the utilization of these specific macrophyte species, previously unexplored in Pakistan’s paper recycling industry, to remove pollutants and heavy metals from wastewater. The study’s findings demonstrate the efficacy of these plants in treating paper mill effluents, offering a sustainable, eco-friendly, and cost-effective alternative to conventional treatment methods. By showcasing the potential of constructed wetlands as a viable solution for industrial wastewater management, this research contributes significantly to the development of greener and more sustainable industrial practices in Pakistan, aligning with global efforts to achieve carbon neutrality and environmental sustainability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Source and Characterization of Wastewater

The wastewater was obtained from the Zaman paper recycling industry and was later employed in this study. The samples were collected directly from the pipe’s end, with no post-processing. These effluents were characterized and analyzed for pH, electrical conductivity (EC), total suspended solids (TSS), total dissolvent solids (TDS), total solids (TS), nitrate, phosphates, and heavy metals (Hg, Pb, Cd, Cr, Cu) using the procedures described in Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater (Table 1).

Table 1.

Influent Characterization of PRI Wastewater.

It was evident that the majority of wastewater quality parameters were exceeding the National Environmental Quality Standards (NEQs) for industrial wastewater. The parameters mentioned in Table 1 were analyzed after the experiment to judge the efficiency of wetlands over the course of a month.

2.2. Experimental Setup

The experiment was performed in the Bioremediation Lab (Room A224, Abbottabad campus of COMSATS University, Pakistan.), Abbottabad campus of COMSATS University, Pakistan. The experimental setup consisted of five rectangular basins (depth: 40 cm, length: 120 cm, width: 90 cm,) made up of acrylic. The first wetland served as the control wetland, which only contained wastewater without any plant or substratum, while the other four wetlands were planted with macrophytes. The wetlands consisted of layers of coarse gravel measuring 3 cm, sand measuring 5 cm, and gravel measuring 1 cm. The wetland media like sand and gravels were added according to a design mentioned by a previous study [13].

Emergent and floating species such as T. latifolia (broadleaf cattail) were collected from Jharikass, E. crassipes (Water hyacinth) and P. stratiotes (Water lettuce) were collected from a waterway in the Sawabi suburb (Khyber Pakhtunkhawa, Pakistan), and A. donax was collected from (Plant Nursery) in COMSATS University Islamabad, Abbottabad Campus. After that, the collected plant species underwent a careful and intensive washing process before being grown in the laboratory using Hoagland solution. The plants grew from June to July after collection, with an average temperature of 35 °C and an average light and dark period of 13 h and 11 h, respectively. Later, the freshly grown plants were moved to constructed wetlands in the Environmental Technology Laboratory of the Department of Environmental Sciences at COMSATS University Islamabad, Abbottabad Campus.

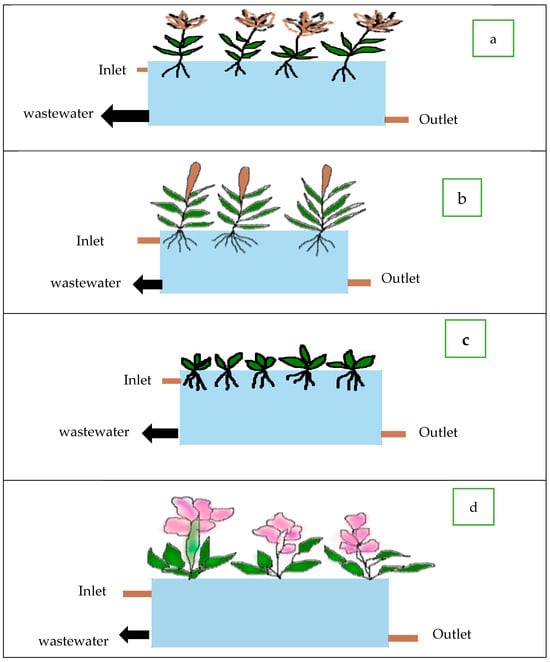

The floating species P. stratiotes and E. crassipes were planted in two reactors (Figure 1). Two emerging species, A. donax and T. latifolia, were planted in the third and fourth reactors. Two kg of biomass were planted in each constructed wetland.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagrams of (a) Arundo donax (b) Typha latifolia (c) Pistia stratiotes (d) Eichhornia crassipes in Constructed Wetland.

All wetland units were fed with the same influent wastewater, the characteristics of which are provided in Table 1 (Influent characterization of PRI wastewater). Wastewater from the original PRI fed into the constructed wetland. This allowed for a direct and meaningful comparison between influent and effluent parameters across all treatments. Given that the study’s objective was to evaluate the performance of wetlands planted with macrophytes under identical influent conditions—rather than to compare planted versus unplanted systems—a separate control reactor without macrophytes was also included. The uniform influent ensured that observed differences in treatment performance could be attributed to the macrophytes present in the wetland units. The experiment was operated for a hydraulic retention period of thirty days.

The experiment was conducted for thirty days. After every five days, wastewater samples were collected to analyze pH, total dissolved solids (TDS), total suspended solids (TSS), total solids (TS), chemical oxygen demand (COD), biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), nitrates, phosphates, and heavy metals including Hg, Pb, Cd, Cr, and Cu. The following procedures were investigated using the criteria specified in the [14] guidelines to evaluate water quality parameters. Pollutant removal rates (%) were calculated according to Equation (1).

Ci is the concentration (mg/L) of the considered parameter in the untreated WW (influent), and Cf is the concentration (mg/L) of the considered parameter in the treatment effluent [15,16]. The nutritional medium comprises 1 L of Hoagland solution per tank [17]. Table 2 shows the exact composition of Hoagland solution.

Table 2.

Composition of Hoagland solution.

At the laboratory scale, the wastewater quality parameters analyzed included chemical oxygen demand (COD), biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), total dissolved solids (TDS), total suspended solids (TSS), total solids (TS), nitrate, phosphate, pH, electrical conductivity, heavy metals (Hg, Pb, Cd, Cr, and Cu), and organic contaminants. All analyses were carried out following the Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater [18].

The chemical oxygen demand (COD) was determined using the closed reflux colorimetric method with a COD digester (HACH, LTG 082.99.40001). For each analysis, 2.5 mL of the wastewater sample was mixed with 1.5 mL of digestion solution and 3.5 mL of sulfuric acid reagent in a COD vial. The vials were digested at 150 °C for 2 h, and the COD concentration was measured using a COD spectrophotometer.

The pH of the wastewater samples was measured using a digital pH meter (Jenway model 520, Dunmow, Essex, England). Electrical conductivity was determined using a conductivity meter.

Phosphate concentration was analyzed using a UV–VIS spectrophotometer (IRMeCO UV-Vis, U2020, Geesthacht, Germany). Approximately 20 mL of the water sample was taken in a beaker, followed by the addition of 0.4 mL of stannous chloride and 1 mL of aluminum molybdate reagent. After the development of the blue color, the sample absorbance was measured at 680 nm, and phosphate concentration was recorded accordingly [18].

Nitrate concentration was also measured using a UV–VIS spectrophotometer (IRMeCO UV-Vis, U2020, Geesthacht, Germany). Twenty milliliters of the sample was taken, and 1 mL of 0.1 N hydrochloric acid was added and mixed thoroughly. The solution was transferred to a cuvette, and absorbance was measured at 220 nm. Nitrate concentration was calculated using a calibration curve [18].

Heavy metal concentrations (Hg, Pb, Cd, Cr, and Cu) were determined using an atomic absorption spectrophotometer (Perkin Elmer Analyst 700, Norwalk, Connecticut, USA) at element-specific wavelengths. Prior to analysis, wastewater samples were filtered and then analyzed following standard procedures [18].

Total suspended solids (TSS) were determined using the filtration method. A well-mixed wastewater sample was filtered through a pre-weighed filter paper, which was then dried in an oven at 105 °C until constant weight. After drying, the filter paper was reweighed, and TSS was calculated using Equation (2).

Total Suspended Solids = W2 − W1

W2 represents the end weight of the filter paper, while W1 denotes its initial weight [18]. To determine the total dissolved solids, 50 mL of the filtered sample was evaporated in a pre-weighed china dish on a heating plate. After the sample had fully evaporated, the china dish was reweighed. Total dissolved solids were determined using the formula presented in Equation (3):

Total Dissolved Solids = W2 − W1

W1 represents the initial weight of the china dish, while W2 denotes the end weight of the china dish [18]. Total solids were determined by summing TDS and TSS using Equation (4) [18]:

Total Solids = TDS + TSS

2.3. Statistical Analysis and Response Surface Models

Data was subjected to statistical analysis via a paired t-test utilizing Python software v. 2.3 in Collab environment. To study the comparative effects of different plant types and their interaction with treatment type and time, response surface models (RSMs) were developed from the experimental data for predicting removal of each pollutant type mentioned above. There were 252 experimental runs available for the model. A custom fractional factorial design was used for model development. There were six factors available for the prediction, some of which included plant species, treatment (wetlands), and time of treatment. The interactive effects were considered for Plant × Wetlands and Plant × Time. There were three (03) replications available for each combination. The design resolution is found to be suitable for estimating main effects and key interactions.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Variations of pH During Constructed Wetlands

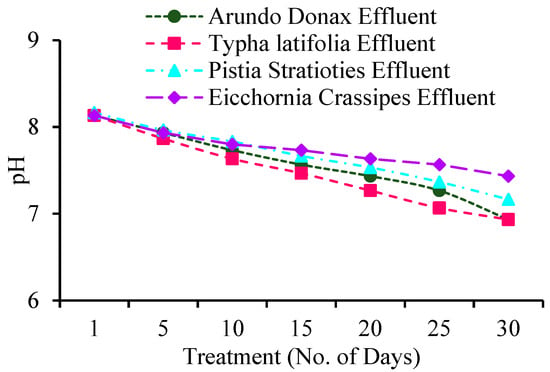

The pH levels of wastewater samples were analyzed prior to and following a five-day exposure to the constructed wetland process, as illustrated in Figure 2. The findings demonstrate a notable decrease in pH in the effluent relative to the influent across all plants. The pH of A. donax influent measured 8.166, while the effluent recorded values of 8.13 on Day 1, 7.93 on Day 5, 7.73 on Day 10, 7.56 on Day 15, 7.43 on Day 20, 7.26 on Day 25, and 6.93 after 30 days. The pH of T. latifolia influent measured 8.16, while the effluent values were 8.13 on Day 1, 7.86 on Day 5, 7.63 on Day 10, 7.46 on Day 15, 7.26 on Day 20, 7.06 on Day 25, and 6.93 after 30 days. The pH levels of P. stratiotes influent measured 8.166, while the effluent recorded 8.16 on Day 1. Subsequent measurements indicated a decline to 7.96 on Day 5, 7.83 on Day 10, 7.66 on Day 15, 7.53 on Day 20, 7.36 on Day 25, and 7.16 after 30 days. The pH of E. crassipes influent was recorded at 8.166, while the effluent pH values were 8.13 on Day 1, 7.93 on Day 5, 7.8 on Day 10, 7.73 on Day 15, 7.63 on Day 20, 7.56 on Day 25, and 7.43 after 30 days.

Figure 2.

Variations of pH during Constructed Wetland.

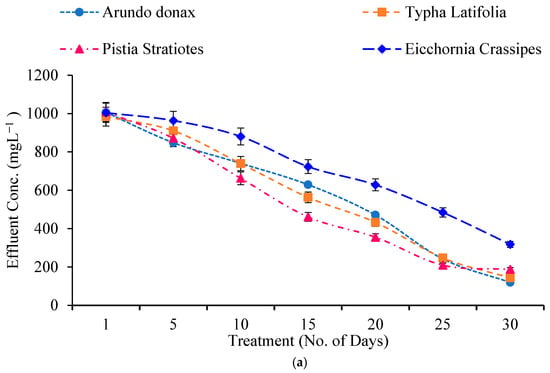

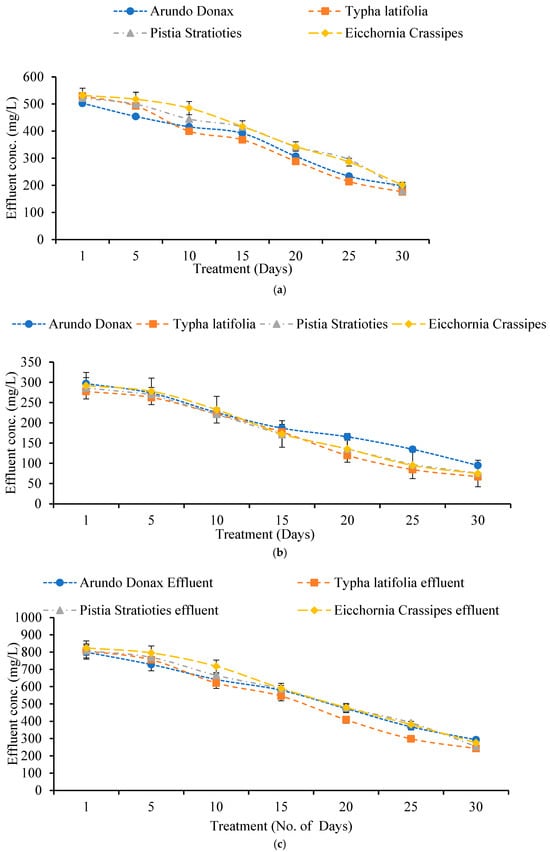

3.2. Impact of Constructed Wetlands on COD and BOD

Wastewater samples were tested for COD and BOD levels before and after treatment in built wetlands (Figure 3a,b). Pollutant concentrations declined consistently across all plant systems.

Figure 3.

(a) Effect of Constructed Wetland on COD. (b) Effect of Constructed Wetland on BOD.

For COD, the influent concentration was 1013 mg/L. After 30 days, effluent COD concentrations decreased to 119.66 mg/L for A. donax (88.18% elimination), 143.66 mg/L for T. latifolia (85.91%), 188 mg/L for P. stratiotes (81.57%), and 318 L forg/L for E. crassipes (68.83%). A. donax demonstrated the highest COD removal effectiveness, increasing from 0.69% on Day 1 to 88.18% by Day 30.

For BOD, the influent concentration was 436 mg/L. After 30 days, the effluent BOD levels were 55.66 mg/L for A. donax (87.23% clearance), 55 mg/L for T. latifolia (87.38%), 120 mg/L for P. stratiotes (72.47%), and 153.66 mg/L for E. crassipes (64.75%). T. latifolia had the greatest overall BOD reduction, increasing from 6.03% on Day 1 to 87.38% on Day 30.

The use of floating and emergent plant species such as water hyacinth (E. crassipes), duckweed (Lemna minor), water fern (Azolla sp.), water spinach (Ipomoea sp.), water lettuce (Pistia stratiotes), and bulrush (Typha spp., Scirpus sp.) is an effective strategy for industrial wastewater treatment. Previous research has shown that employing floating plants in palm oil mills [19] and dairy effluents [20] can reduce BOD and COD by up to 96% and 94%, respectively. These gains are ascribed to microbial–plant interactions, with oxygen-rich rhizospheres promoting microbial breakdown of organic matter [21]. Microbial biofilms on hydrophyte roots promote COD reduction, while adsorption, sedimentation, and microbial degradation aid in BOD removal [22].

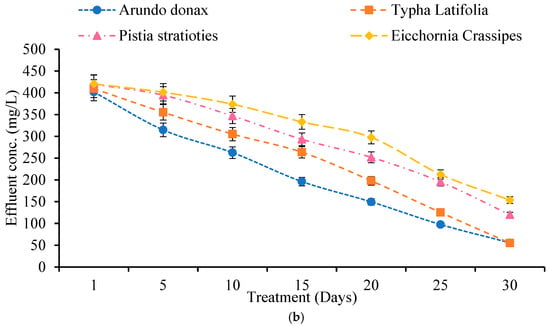

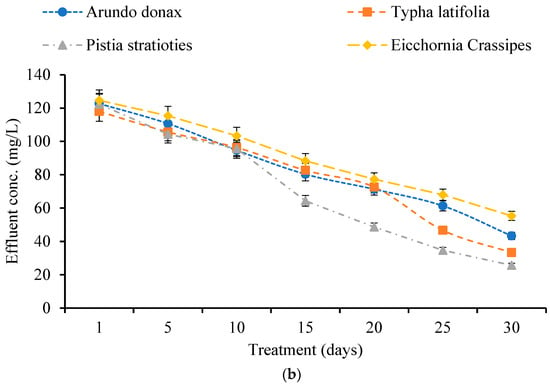

3.3. Effect of Constructed Wetlands on TDS, TSS, and TS Removal

Wastewater samples were tested for total dissolved solids (TDS), total suspended solids (TSS), and total solids (TS) before and after treatment with the constructed wetland system (Figure 4). Across all plant species, all measurements showed a consistent drop in the effluent when compared to the influent.

Figure 4.

(a) Effect of Constructed Wetland on Total Dissolved Solids (TDS). (b) Effect of Constructed Wetland on Total Suspended Solids (TSS). (c) Effect of Constructed Wetland on Total Solids (TS).

The initial influent TDS concentration was 536.66 mg/L. After 30 days of treatment, effluent TDS concentrations were reduced to 198 mg/L for A. donax, 175.66 mg/L for T. latifolia, 179 mg/L for P. stratiotes, and 201.33 mg/L for E. crassipes, resulting in removal efficiencies of 63.10%, 67.26%, 66.64%, and 62.48%, respectively. T. latifolia had the highest TDS removal effectiveness.

The influent TSS concentration was 301 mg/L. After 30 days, effluent TSS levels had been reduced to 95 mg/L (A. donax), 67 mg/L (T. latifolia), 75.66 mg/L (P. stratiotes), and 75 mg/L (E. crassipes), with removal efficiencies of 68.43%, 77.74%, 74.85%, and 75.07%, respectively. T. latifolia once again had the highest TSS elimination rate.

The influent TS concentration measured 837.66 mg/L. After 30 days, effluent TS concentrations were 293 mg/L (A. donax), 242.66 mg/L (T. latifolia), 254.66 mg/L (P. stratiotes), and 276.33 mg/L (E. crassipes), resulting in removal efficiencies of 65.02%, 71.03%, 69.59%, and 67.01%, respectively. T. latifolia again demonstrated greater performance.

Pollutant elimination in built wetlands is primarily achieved by plant transformation and root absorption [22]. Halophytic plants retain dissolved solids in their tissues, but aquatic macrophytes have physiological adaptations that improve TDS elimination [23]. Root structure influences nutrient uptake and filtration efficiency [24]. Physical filtration, sedimentation, and root uptake of suspended particles all lead to considerable reductions in TDS, TSS, and TS in artificial wetlands [25,26].

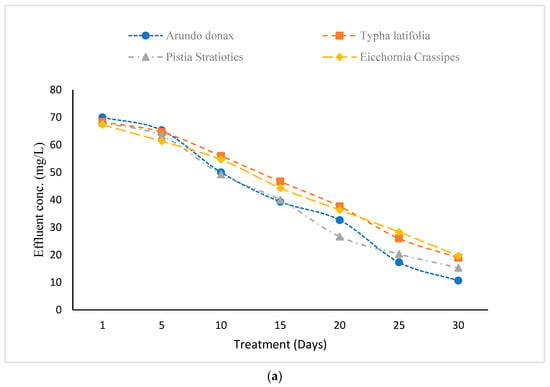

3.4. Effect of Constructed Wetlands on Nitrates and Phosphates

Nitrate concentrations in wastewater were measured before and after exposure to the constructed wetland process (Figure 5a). All plant species showed a progressive decrease in effluent nitrate levels over the 30-day period.

Figure 5.

(a) Effect of Constructed Wetland on Nitrates. (b) Effect of Constructed Wetland on Phosphates.

For A. donax, nitrate removal efficiency increased from 12.12% on Day 1 to 86.59% on Day 30, with influent and effluent concentrations of 79.66 mg/L and 10.66 mg/L, respectively. T. latifolia showed efficiencies ranging from 14.24% (Day 1) to 76.13% (Day 30), reducing nitrates from 79.66 mg/L to 19 mg/L. P. stratiotes achieved a range from 14.63% (Day 1) to 80.72% (Day 30) removal, lowering nitrates from 79.66 mg/L to 15.33 mg/L mg/L. E. crassipes ranged from 15.45% (Day 1) to 75.32% (Day 30) efficiency, reducing nitrates to 19.66 mg/L. Among the species, A. donax exhibited the highest nitrate removal efficiency.

Phosphate concentrations were similarly assessed (Figure 5b). All species showed substantial reductions over time. For A. donax, phosphate removal efficiency increased from 8.91% on Day 1 to 67.79% on Day 30, reducing concentrations from 134.66 mg/L to 43.33 mg/L. T. latifolia improved from 12.36% to 75.25%, reaching 33.33 mg/L by Day 30. P. stratiotes achieved the highest phosphate removal, rising from 9.14% to 80.93%, with an effluent concentration of 25.66 mg/L. E. crassipes showed the lowest performance, increasing from 7.42% to 58.90% over the period, with a final concentration of 55.33 mg/L. Overall, A. donax was most effective for nitrate removal, while P. stratiotes was superior for phosphate removal.

Industrial wastewater and effluents often exhibit elevated concentrations of nitrogen and phosphorus. Floating and emergent plants have been shown to effectively decrease total nitrogen and phosphorus levels, with plant uptake facilitating phosphorus removal, and denitrification and sedimentation aiding in nitrogen removal [27]. The results underscore the significant function of constructed wetlands in the sustainable treatment of industrial wastewater, offering efficient and environmentally friendly approaches to pollution reduction.

3.5. Findings and Discussion: Heavy Metal Removal by Wetland Plants

Effluents from recycled paper, deinking, and pulp and paper operations generally contain chromium, lead, zinc, copper, nickel, cadmium, and iron, with sporadic occurrences of arsenic, manganese, and cobalt. The observed concentrations demonstrate considerable diversity based on the feedstock (kind of recovered paper), pulping/deinking techniques, regional industrial practices, and whether the values refer to raw wastewater or treated effluent [28]. Chromium (Cr), lead (Pb), copper (Cu), and mercury (Hg) are commonly reported in concentrations ranging from less than 0.01 mg/L to several mg/L in raw and pulping wastewaters; Cr is regularly identified as a principal metal in investigations of recycled paper. The concentration of cadmium in wastewater from the paper sector is typically modest, ranging from 1 to 2 mg/L [29,30].

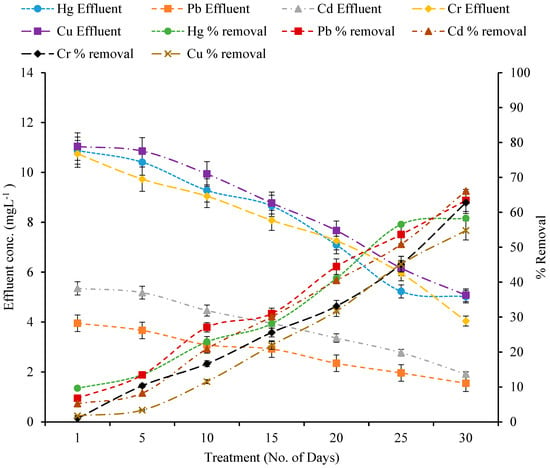

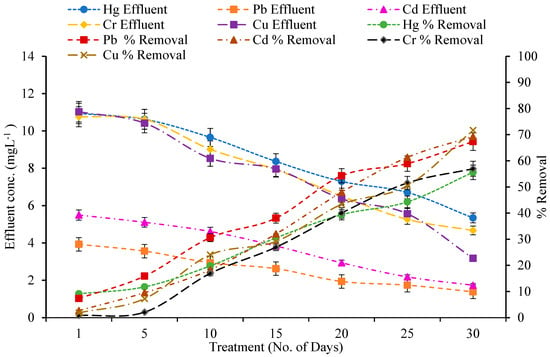

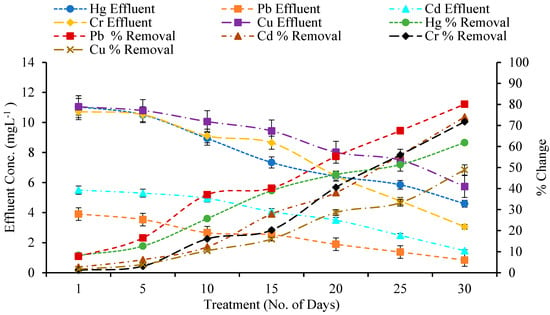

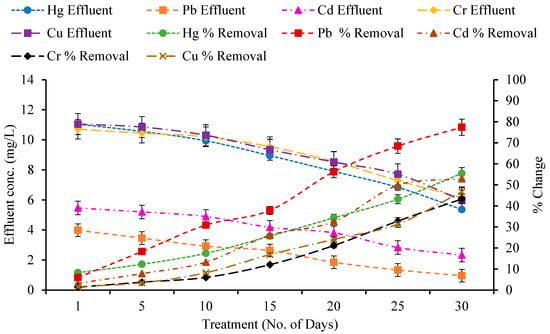

The removal efficiency of mercury (Hg), lead (Pb), cadmium (Cd), chromium (Cr), and copper (Cu) by various wetland plant species—A. donax, T. latifolia, P. stratiotes, and E. crassipes—was assessed over a 30-day period in a constructed wetland system (Figure A1, Figure A2, Figure A3 and Figure A4). Across all treatments, heavy metal concentrations in the effluent were much lower than in the influent, demonstrating the efficacy of these macrophytes in phytoremediation. A paired t-test showed that various macrophytes significantly absorbed metals from wetlands as compared to the control wetland (Table 3).

Table 3.

STATISTICAL COMPARISON: Control vs. All Planted Systems, Conservative Approach: Comparing Control to WORST-Performing Plants.

Mercury (Hg) Removal.

All treatments had initial Hg influent concentrations of 12.04 mg/L. Over the 30-day timeframe, removal efficiencies varied per plant species. P. stratiotes removed the most Hg (61.82%), followed by A. donax (58.31%), T. latifolia (55.61%), and E. crassipes (55.48%) (Figure A1, Figure A2, Figure A3 and Figure A4). The corresponding effluent values were 4.59, 5.02, 5.34, and 5.36 mg/L, respectively. The gradual rise in removal over time reflects the development of plant–microbe interactions and active metal uptake mechanisms via roots and rhizomes.

Lead (Pb) Removal.

Pb removal was very effective in P. stratiotes and E. crassipes, reaching 80.09% and 77.41% after 30 days, with effluent values of 0.84 mg/L and 0.95 mg/L, respectively. T. latifolia and A. donax both performed well, with removal rates of 67.35% and 63.41%, respectively. Floating macrophytes (P. stratiotes and E. crassipes) have increased Pb uptake due to their large root mats and direct contact to the water column, which allow for effective metal sorption and translocation [31,32].

Cadmium (Cd) Removal.

P. stratiotes had the maximum Cd removal (74.04%), followed by T. latifolia (69.32%), A. donax (66.07%), and E. crassipes (52.88%) (Figure A1, Figure A2, Figure A3 and Figure A4). Effluent Cd concentrations decreased from 5.65 mg/L to 1.46 mg/L, 1.73 mg/L, 1.91 mg/L, and 2.33 mg/L, respectively. Notably, A. donax demonstrated significant Cd removal compared to other metals, demonstrating its metal accumulator potential [33,34].

Chromium (Cr) Removal.

The influent Cr concentration was 10.85 mg/L across all treatments (Figure A1, Figure A2, Figure A3 and Figure A4). After 30 days, P. stratiotes had the highest removal efficiency (71.78%), followed by A. donax (62.78%), T. latifolia (56.98%), and E. crassipes (43.29%). P. stratiotes’ greater Cr removal is consistent with its ability to accumulate metals in both roots and leaves [35], whereas A. donax relies mostly on root uptake and phytostabilization mechanisms.

Copper (Cu) Removal.

Cu removal followed a slightly different trend, with T. latifolia obtaining the maximum efficiency (71.72%), lowering influent Cu levels from 11.23 mg/L to 3.17 mg/L (Figure A1, Figure A2, Figure A3 and Figure A4). This was followed by A. donax (54.82%), P. stratiotes (48.88%), and E. crassipes (46.78%). The ability of T. latifolia to efficiently remove Cu is consistent with the findings of [36,37], who showed considerable Cu, Pb, and Zn uptake by cattail rhizomes.

Comparative Performance and Mechanisms.

Overall, the four species’ relative heavy metal removal performance can be described as follows:

- Best mercury removal: P. stratiotes (61.82%).

- P. stratiotes (80.09%) and E. crassipes (77.41%) have the best lead removal rates.

- Best Cd removal: P. stratiotes (74.04%).

- Best Cr removal: P. stratiotes (71.78%).

- T. latifolia had the best Cu removal rate (71.72%).

Floating macrophytes (P. stratiotes and E. crassipes) were more effective at removing Pb and Cr, most likely due to direct metal uptake from the water column and the potential to accumulate metals in leaves and shoots [38]. A. donax showed high Cd removal and modest efficiency for other metals, consistent with its known activity as a phytostabilizer [39]. T. latifolia, a rooted emergent plant, showed especially robust Cu removal, likely due to its extensive rhizosphere and associated microbial population.

These discrepancies highlight the complimentary roles of various macrophyte types in artificial wetlands. Rooted emergent species such as A. donax and T. latifolia provide stable platforms for microbial communities, facilitating nutrient and metal transformations [40], whilst floating species (P. stratiotes and E. crassipes) allow direct and efficient uptake of dissolved metals. Plant uptake, microbiological activities, and physicochemical transformations work together to achieve high removal efficiency.

Some negative impacts on the growth of wetland macrophytes were also noted. When macrophytes were grown in wastewater from the paper industry for an extended period of time, they typically exhibited evident signs of poisoning. Lignin derivatives, chlorinated organics, dyes, and heavy metals induced chlorosis, necrosis, stunted development, and decreased biomass. The plants struggle with photosynthesis, have reduced chlorophyll, and have nutrient deficiencies. Long-term exposure causes oxidative stress, membrane damage, and a decrease in antioxidant enzymes at the biochemical level.

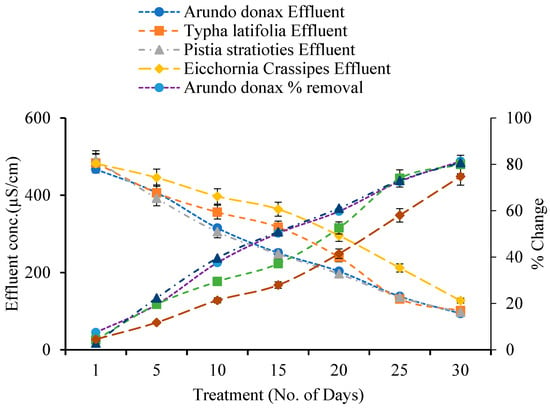

3.6. Effects of Constructed Wetland on Electrical Conductivity

The electrical conductivity (EC) of wastewater was measured before and after treatment in built wetlands for 30 days (Figure 6). All plant systems demonstrated a significant decrease in EC relative to the influent. A. donax’s EC removal efficiency gradually rose from 7.51% on Day 1 to 81.39% on Day 30, with influent and effluent concentrations of 505.33 µS/cm and 94 µS/cm, respectively.

Figure 6.

Effect of Constructed Wetland on Electrical Conductivity.

T. latifolia eliminated 4.28% on Day 1 and 79.94% by Day 30, lowering EC from 505.33 µS/cm to 143.66 µS/cm. P. stratiotes demonstrated 2.90% removal on Day 1 and 80.73% on Day 30, with an effluent EC of 97.33 µS/cm. E. crassipes had the lowest removal rate, rising from 4.55% on Day 1 to 74.80% on Day 30, with a final EC of 127.33 µS/cm.

Overall, A. donax had the highest EC removal effectiveness, followed by P. stratiotes, T. latifolia, and E. crassipes.

3.7. Response Surface Models

Variables with parameter values equal to zero (0.00) were eliminated during model construction since their coefficients fell below the chosen threshold (0.0000). As a result, these factors are considered insignificant and were not subjected to significance testing. Parameters with significant coefficients (p ≤ 0.05) are highlighted for clarity and interpretation (Table 4).

Table 4.

Response Surface Models for Wastewater quality parameters treatment in wetlands.

Influence of Experimental Factors

The RSM analysis results show that the number of days, A. donax, and wetlands are the most important variables for maximum pollution removal. While some plant-treatment combos, such as T. latifolia–wetlands and P. stratiotes–ozonation, show potential, others, such as E. crassipes, have little efficacy until supplemented with integrative treatments (Table 4).

The variable number of days emerged as a significant factor in most response variables, both alone and through interactions with plant species and treatment modalities. It has a considerable impact on the elimination of mercury, lead (Pb), cadmium (Cd), chromium (Cr), copper (Cu), and biochemical oxygen demand. Among the plant species, A. donax consistently had the greatest individual and interacting effects, particularly when combined with wetlands or time. In contrast, Eichhornia crassipes showed negligible or nonsignificant influence on most outcomes.

Model Adequacy

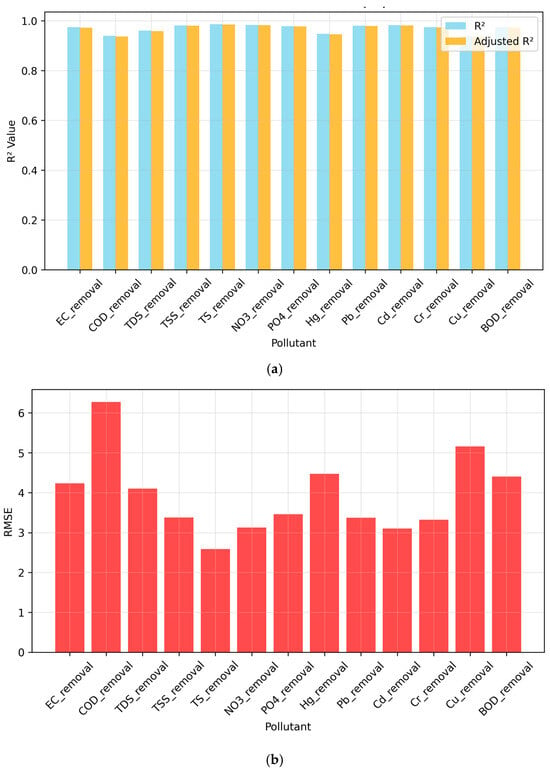

The model adequacy is measured in terms of various parameters. R2 and adjusted R2 are the primary indicators of model fitness, wherein the latter is adjusted for number of parameters in the model. The F test is used to determine the overall significance of the model by testing the null hypothesis at a 5% confidence level. Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) are statistical measures used for exhibiting the balance of the model between complexity and accuracy. Root mean square error (RMSE) is the practical measure of model accuracy providing the magnitude of the error directly in original units. These parameters are shown in Table 5 and Figure 7.

Table 5.

Model Adequacy with F-statistics, AIC, and BIC.

Figure 7.

(a) R2 values for RSM Models (b) RMSE values for RSM Models.

The average R2 (0.969) indicates good explanatory power, while the average adjusted R2 (0.967) accounts for model complexity showing approximately the same explanatory power as R2. All models satisfied the F-statistic (p < 0.05) test, demonstrating an excellent fit to experimental data. RMSE values also indicate acceptable prediction error with an average of 3.920.

Based upon the results, it can be said that models reliably predict pollutant removal efficiencies, identifying significant effects of plant species, wetlands, and time effects. Hence, they are found to be suitable for response surface analysis and system optimization for scientific design of constructed wetlands.

For mercury elimination, P. stratiotes–wetlands (6.155) is a very strong, highly significant positive interaction along with the number of days (1.536), which is also a highly significant factor. Wetlands_Days (−0.177 **) is a significant negative interaction, meaning the effect of wetlands diminishes over time for Hg. In the case of lead (Pb), several plants and wetlands (7.742) have significant impacts on the removal model, including A. donax (3.777 *), P. stratiotes (−2.906 *), and E. crassipes (−5.052). Moreover, the interaction E. crassipes–wetlands (9.581 *) has a highly significant positive impact on its removal. However, A. donax–wetlands (−8.496 *) has a highly negative interaction effect. Among the plant types, A. donax alone influenced cadmium (Cd) removal, and Days of treatment and all its interactions with plants are significant. A. donax–wetlands (−3.810 *) has a significant negative interaction impact on Cd removal, showing its detrimental impact on Cd removal. The positive effect of time is universal across plants, not specific to PS, EC, and wetlands. In terms of chromium (Cr) elimination, P. stratiotes–wetlands (4.759 ***) is a strong positive interaction. A. donax (2.474 *) has a significant impact, but T. latifolia (−0.089) does not. Wetlands alone is significant but negative (−2.187 *) in this case. T. latifolia–wetlands (6.973*) has a highly significant positive impact on Cu removal, providing evidence of the powerful synergy between T. latifolia and wetlands treatment. Only A. donax (2.709) has a positive significant impact, among the plants, on BOD removal. E. crassipes (−2.884) is also significant, but negatively. Wetland treatment (3.427 *) is also a significant parameter. Wetlands_Days (−0.225 *) has significant negative interaction. The interactions of A. donax–wetlands (7.317 *) and T. latifolia–wetlands (3.275) also have positive significant relationship with BOD removal.

The insights from these models can be used to gather several overarching principles that can be used for customized design and application of Constructed Wetlands. Time of treatment was found to be a universally critical factor with highly significant (p < 0.001) impact for removal of every pollutant without exception. This is a fundamental finding showing that longer treatment times consistently improve removal efficiency across all plant types, irrespective of the pollutant. Wetland was found to be a powerful treatment method with highly significant positive impacts on removal of most pollutants (EC, TSS, NO3, PO4, Hg, Pb, BOD). This provides evidence for its use as a highly effective treatment method for a broad spectrum of pollutants.

Wetland containing A. donax shows significant positive effects for most of the pollutants (EC, TDS, TSS, TS, PO4, Pb, Cd, Cr, BOD), showing its consistent removal performance over the control wetland. On the other hand, P. stratiotes has strong negative individual effects on several pollutants (EC, TSS, TS, PO4, Pb, Cd, Cr). However, its interaction with wetlands is powerfully positive for many pollutants, including some from the above list (EC, COD, NO3, PO4, Hg, Pb, Cr). This suggests that this plant is ineffective alone but becomes an effective removal agent in a constructed wetland system. E. crassipes has significant negative individual coefficients for EC, TDS, TSS, TS, Hg, Pb, Cd, and BOD. It suggests that it may be releasing compounds that hinder removal of pollutants or may even contribute to their retention with chemical processes. Crucially, it has a high positive interaction with wetlands for Pb removal, making it a suitable candidate for specialized treatment applications.

The T. latifolia and wetlands interaction for Cu (6.973 ***) demonstrated one of the largest coefficients in the entire study. This is a key finding for targeted removal of Cu. There was a dramatic contrast on Pb removal for the interaction effects of wetlands with E. crassipes (9.581 *—highly positive) and A. donax (−8.496 *—highly negative). This shows how crucial it is to select the appropriate plant types for wetland treatment in order to avoid severely detrimental effects.

The Wetlands_Days interactive coefficient was significantly negative for PO4, Hg, Cu, and BOD. This is a critical finding showing that, while wetlands are powerful, their relative effectiveness may decrease with time. The possible reasons for this trend could be saturation or changes in microbial communities. T. latifolia showed significant effects on few pollutants’ removal as an individual factor. However, its true value lies in its interactions with wetlands, as shown in the removal of TDS, TSS, TS, PO4, Cd, and, most notably, Cu.

4. Conclusions

- This study’s findings show that constructed wetlands planted with monoculture species, specifically Arundo donax, Typha latifolia, Pistia stratiotes, and Eichhornia crassipes, may effectively treat paper mill wastewater from the Hattar Industrial Estate. The macrophytes had diverse levels of removal effectiveness for several parameters such as COD, BOD, total solids, nitrates, phosphates, and heavy metals (Hg, Pb, Cd, Cr, and Cu). The use of inexpensive and locally available materials in created wetlands is a viable way to enhance wastewater treatment in the paper recycling industry.

- RSM indicated that retention time, A. donax, and wetlands greatly improve pollution removal, although various plant–treatment combinations provide varying efficiencies, emphasizing the need of synergistic effects for maximum performance. There was a diminishing impact of wetland treatment on the removal of pollutants over time. The study also identified specific plant types that can be used for customized removal of certain pollutants with wetlands.

- Furthermore, this study helps global efforts to achieve carbon neutrality by proposing a practical approach for implementation in developing nations. The findings of this study can be utilized to guide the design and operation of constructed wetlands for effective wastewater treatment, thereby reducing environmental pollution and supporting sustainable industrial practices.

- Based on the above results, it was recommended to examine how different hydraulic retention durations and seasonal changes affect treatment efficacy and vegetation performance in artificial wetlands. The nutrient removal efficiency and biomass output of A. donax, T. latifolia, P. stratiotes, and E. crassipes in the treatment of paper mill effluent should be determined.

- The viability of mixed plant species arrangements for pollution reduction, system resilience, and biological diversity should be evaluated. By implementing these recommendations, paper recycling industries can significantly improve the effectiveness of their wastewater treatment processes, ensuring environmental compliance and reducing the ecological impact of their operations.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Q.M., M.T.H. and B.S.Z.; Software, U.G.; Formal analysis, Q.M., U.G. and Y.-T.H.; Investigation, A.I. and M.S.; Resources, Q.M. and Y.-T.H.; Data curation, Y.-T.H.; Writing—review and editing, A.I., Q.M., M.I. and Y.-T.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Effect of Constructed Wetland on Heavy metals by A. donax.

Figure A2.

Effect of Constructed Wetland on Heavy metals by T. latifolia.

Figure A3.

Effect of Constructed Wetland on Heavy metals by P. stratiotes.

Figure A4.

Effect of Constructed Wetland on Heavy metals by E. crassipes.

References

- Ukaogo, P.O.; Ewuzie, U.; Onwuka, C.V. Environmental pollution: Causes, effects, and remedies. In Microorganisms for Sustainable Environment and Health; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 419–429. [Google Scholar]

- Iftikhar, A.; Hayat, M.T.; Zeb, B.S.; Siddique, M.; Bhatti, Z.A. Anaerobic biological treatment of wastewater from the paper recycling industry by a UASB reactor. Sains Malays. 2023, 52, 1087–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, M.N. Pulp mill wastewater: Characteristics and treatment. Biol. Wastewater Treat. Resour. Recover. 2017, 2, 119–139. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood, Q.; Shaheen, S.; Bilal, M.; Tariq, M.; Zeb, B.S.; Ullah, Z.; Ali, A. Chemical pollutants from an industrial estate in Pakistan: A threat to environmental sustainability. Appl. Water Sci. 2019, 9, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Muhamad, M.H.; Abdullah, S.R.S.; Hasan, H.A.; Rahim, R.A.A. Comparison of attached- versus suspended-growth SBR systems for treatment of recycled paper mill wastewater. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 163, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brix, H. Wastewater treatment in constructed wetlands: System design, removal processes, and treatment performance. In Constructed Wetlands for Water Quality Improvement; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Yusoff, M.F.M.; Rozaimah, S.A.S.; Hassimi, A.H.; Hawati, J.; Habibah, A. Performance of a continuous pilot subsurface constructed wetland using Scirpus grossus for removal of COD, colour, and suspended solids in recycled pulp and paper effluent. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2019, 13, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, A.K.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, C. Constructed wetlands: An approach for wastewater treatment. Elixir Pollut. 2011, 37, 3666–3672. [Google Scholar]

- Shravani, M.; Banerjee, R.; Pallavi, N. Natural and constructed wetlands: A review on water purification and ecosystem services. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2025, 16, 1245–1269. [Google Scholar]

- Arivoli, A.; Mohanraj, R.; Seenivasan, R. Application of vertical flow constructed wetlands for heavy metal removal from pulp and paper industry wastewater. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 13336–13343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautam, P.K.; Gautam, R.K.; Banerjee, S.; Chattopadhyaya, M.C.; Pandey, J.D. Heavy metals in the environment: Fate, transport, toxicity, and remediation technologies. Nova Sci. Publ. 2016, 60, 101–130. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, P.; Pei, H.; Hu, W.; Shao, Y.; Li, Z. Influencing factors and improvement measures for microbial degradation in constructed wetlands. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 157, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Ma, L.; Wang, J.; Zhao, X.; Jing, Y.; Liu, C.; Xu, M. Research progress on the removal of contaminants from wastewater by constructed wetland substrate: A review. Water 2024, 16, 1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APHA. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 21st ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, T.; Al-Muyeed, A.; Yadav, A.K.; Miah, M.J.; Hasan, M.R.; Zaman, T.; Ahmed, T. Influence of aeration, plants, electrodes, and pollutant loads on treatment performance of constructed wetlands: A comprehensive study with septage. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 892, 164558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeb, B.S.; Mahmood, Q.; Irshad, M.; Zafar, H.; Wang, R. Sustainable treatment of combined industrial wastewater using phytoremediation in biofilm wetlands. Int. J. Phytorem. 2025, 27, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoagland, D.R.; Arnon, D.I. The water-culture method for growing plants without soil. Calif. Agric. Exp. Stn. Circ. 1950, 347, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- APHA; AWWA; WEF. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 24th ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Darajeh, N.; Idris, A.; Masoumi, H.R.F.; Nourani, A.; Truong, P.; Sairi, N.A. Modeling BOD and COD removal in floating wetlands treating palm oil mill effluent. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 181, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, R.D.C.S.D.; Lôbo, I.P.; Ribeiro, V.D.S.; Rodrigues, L.B.; Almeida Neto, J.A.D. Phytoremediation potential of aquatic macrophytes in dairy wastewater treatment. Int. J. Phytorem. 2020, 22, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, S.; Vidhya, K.; Sivakumar, C.; Sugnathi, M.; Shanmugavadivu, V.; Devi, M. Textile wastewater treatment using natural coagulant (Azadirachta indica). Int. Res. J. Multidiscip. Technovation 2019, 1, 636–642. [Google Scholar]

- Shahid, M.J.; Al-Surhanee, A.A.; Kouadri, F.; Ali, S.; Nawaz, N.; Afzal, M.; Soliman, M.H. Role of microorganisms in the remediation of wastewater in floating treatment wetlands: A review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valipour, A.; Hamnabard, N.; Woo, K.S.; Ahn, Y.H. Performance of high-rate constructed phytoremediation process with attached growth for domestic wastewater treatment: Effect of high TDS and Cu. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 145, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Shahid, M.J.; Alnusairi, G.S.; Afzal, M.; Khan, A.; El-Esawi, M.A.; Ali, S. Implementation of Floating Treatment Wetlands for Textile Wastewater Management: A Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, V.; Hiwrale, I.; Dhodapkar, R.S.; Pal, S. Constructed wetlands: Insights and future directions. In Biological and Hybrid Wastewater Treatment Technology; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 303–343. [Google Scholar]

- Gabr, M.E.; Salem, M.; Mahanna, H.; Mossad, M. Floating wetlands for sustainable drainage wastewater treatment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangler, J.T.; Sample, D.J.; Fox, L.J.; Albano, J.P.; White, S.A. Nitrogen and phosphorus removal by plants in floating treatment wetlands. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 5751–5768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X.; Xu, Y.; Yin, L.; Wang, R.; Li, P.; Wang, J.; Liu, K. Sustainable utilization of pulp and paper wastewater. Water 2023, 15, 4135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Yue, B.; Meng, B.; Wang, T.; Liang, Y. Simulation of heavy metals and organic contaminants during waste paper recycling. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 63834–63846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furszyfer Del Rio, D.D.; Sovacool, B.K.; Griffiths, S.; Bazilian, M.; Kim, J.; Foley, A.M.; Rooney, D. Decarbonizing the pulp and paper industry: A critical and systematic review of sociotechnical developments and policy options. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 167, 112706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubenova, L.; Schröder, P. Effects of heavy metals on detoxification systems of Typha latifolia. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 996–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Xiang, Z.; Peng, T.; Li, H.; Huang, K.; Liu, D.; Huang, T. Effects of melatonin-treated Nasturtium officinale on cadmium uptake. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2021, 101, 2288–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaldi, P.; Silvetti, M.; Manzano, R.; Brundu, G.; Roggero, P.P.; Garau, G. Phytostabilization of arsenic and trace metals using Phragmites australis and Arundo donax. Geoderma 2018, 314, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Wang, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Sun, W. Human health risk assessment of heavy metals in soil and food crops in the Pearl River Delta urban agglomeration of China. Food Chem. 2020, 316, 126213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ugya, A.Y.; Imam, T.S.; Tahir, S.M. Removal of heavy metals using Pistia stratiotes from an industrially polluted stream. IOSR J. Environ. Sci. Toxicol. Food Technol. 2015, 9, 48–51. [Google Scholar]

- Hegazy, A.K.; Abdel-Ghani, N.T.; El-Chaghaby, G.A. Phytoremediation potential of Typha domingensis for industrial wastewater. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 8, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukumaran, D. Phytoremediation of heavy metals using constructed wetland technology. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2013, 1, 92–97. [Google Scholar]

- Sarwar, T.; Shahid, M.; Natasha; Khalid, S.; Shah, A.H.; Ahmad, N.; Bakhat, H.F. Heavy metal accumulation in soil–plant systems irrigated with wastewater. Environ. Geochem. Health 2020, 42, 4281–4297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leguizamo, M.A.O.; Gómez, W.D.F.; Sarmiento, M.C.G. Native wetland plants for heavy metal phytoremediation: A review. Chemosphere 2017, 168, 1230–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Zhang, B.; Peng, X.; Zhang, X.; Sun, B.; Sun, H.; Zhuang, X. Microbial community dynamics in constructed wetlands under varying ammonium concentrations. Process Biochem. 2020, 93, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.