Integrating Multi-Index and Health Risk Assessment to Evaluate Drinking Water Quality in Central Romania

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

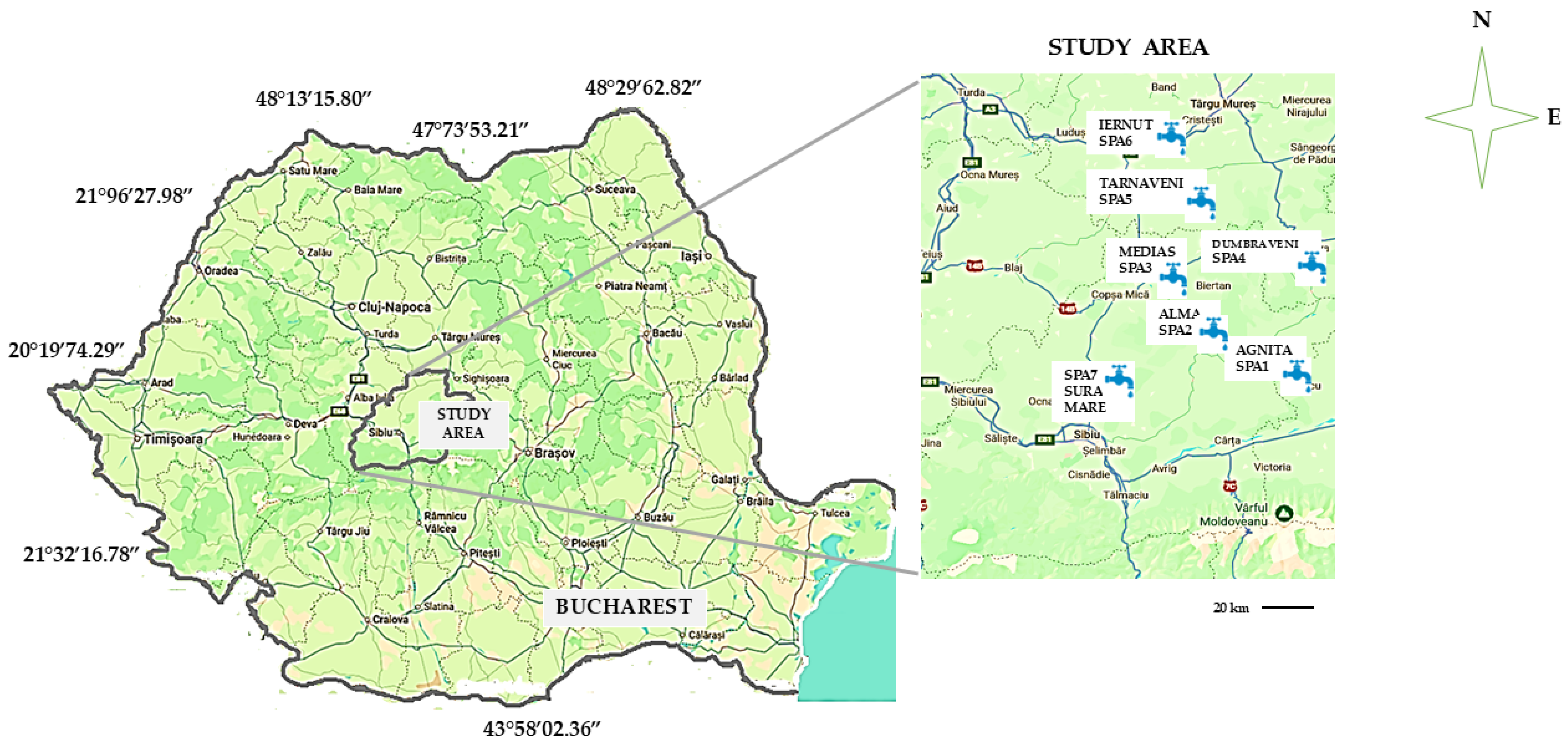

2.1. Area of Study and Sampling Procedure

2.2. Instrumentation Analysis

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Pollution Degree Estimation

2.5. Evaluating the Exposure at Potential Toxic Agents in Human Populations

3. Results and Discussion

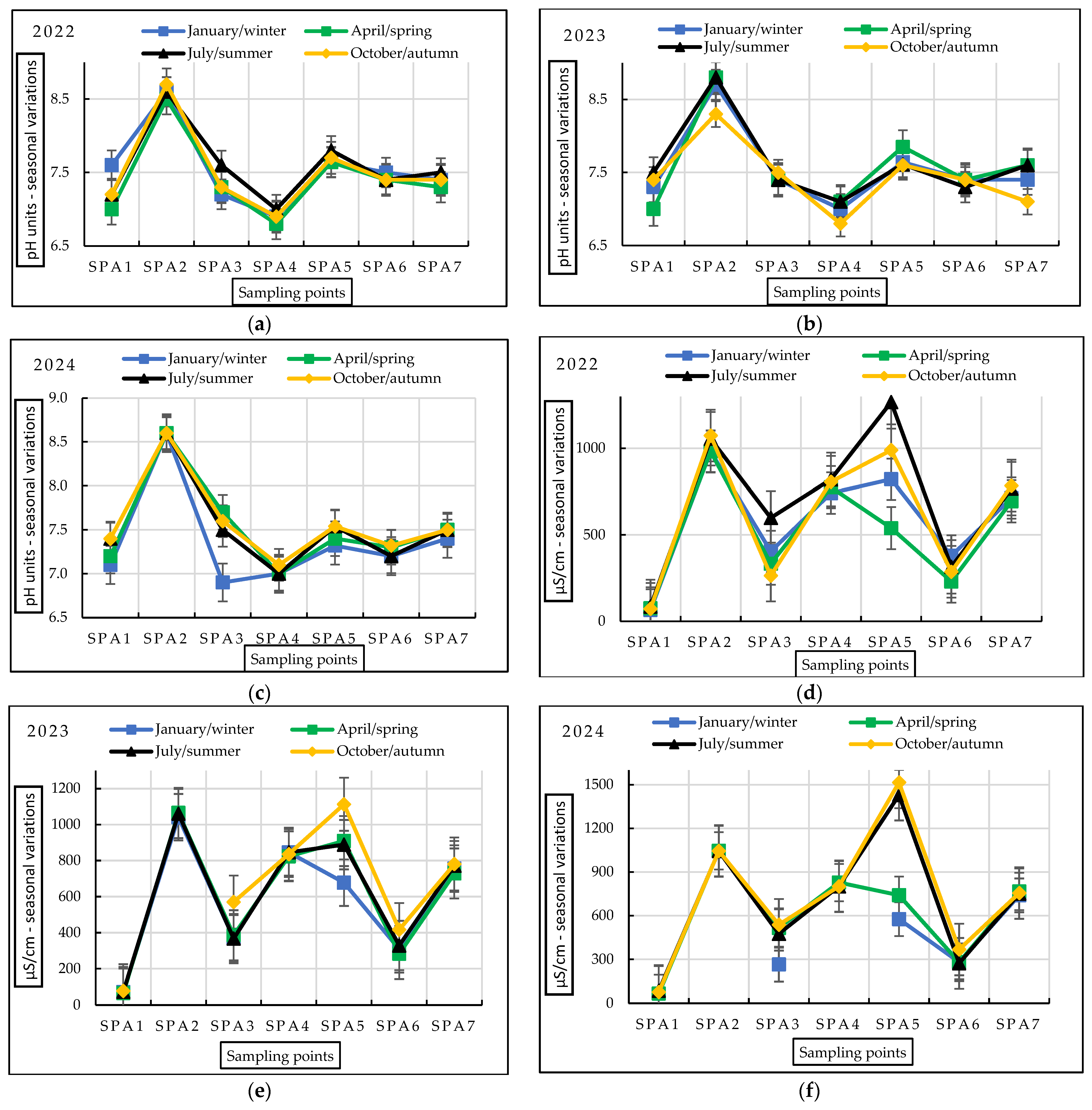

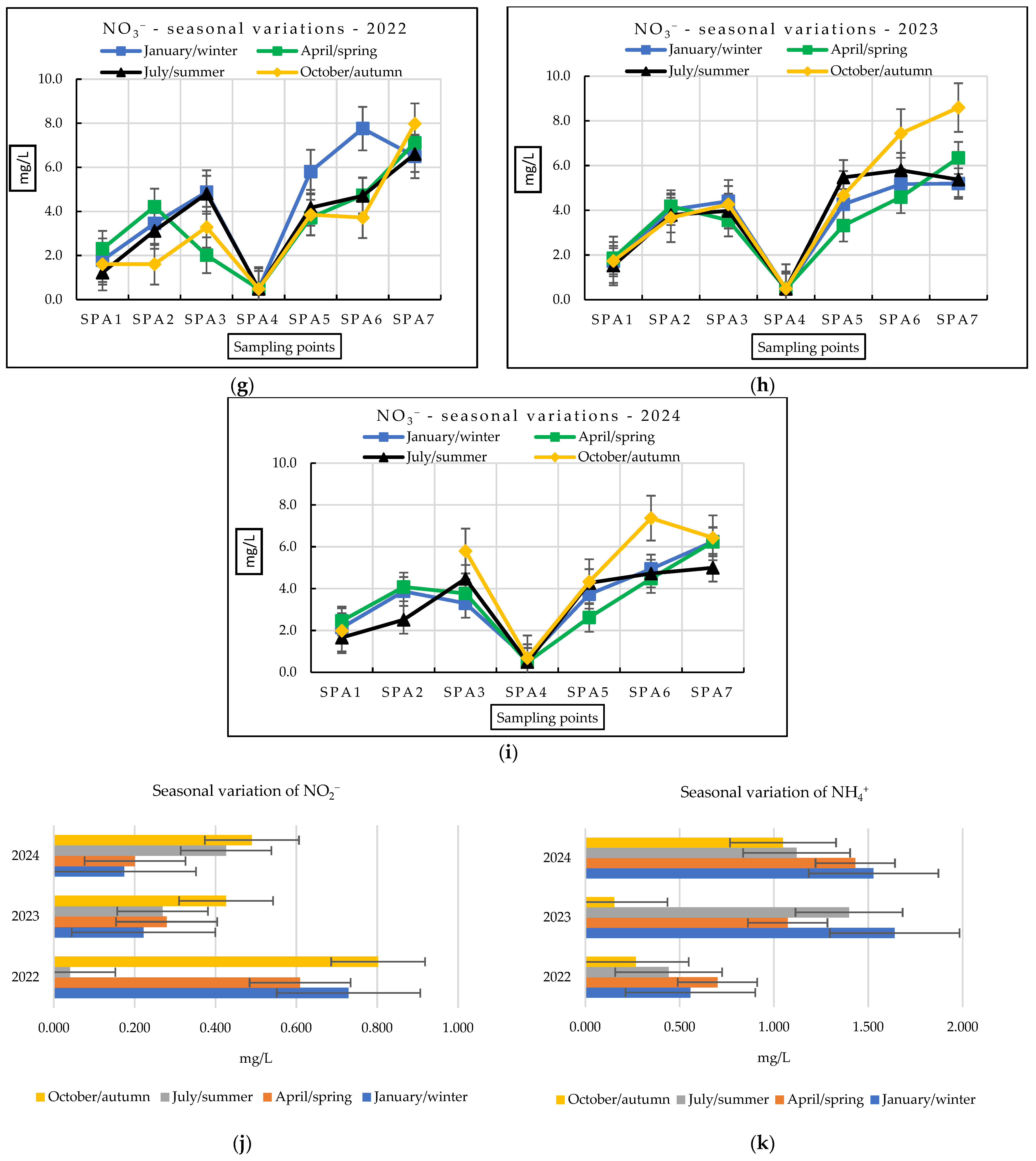

3.1. Assessment of Physicochemical Parameters in Water

3.2. Spatiotemporal Analysis of Water Pollution

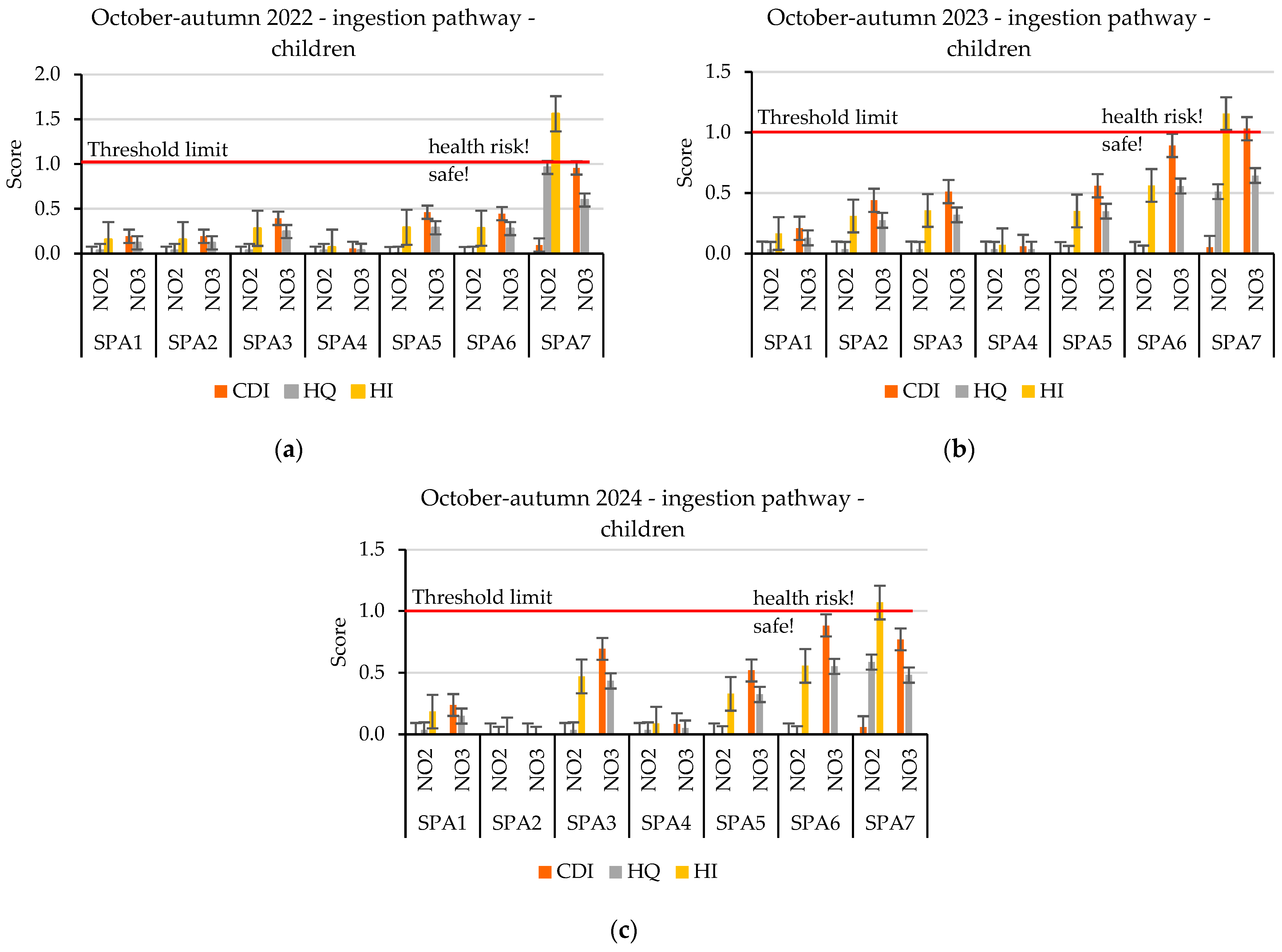

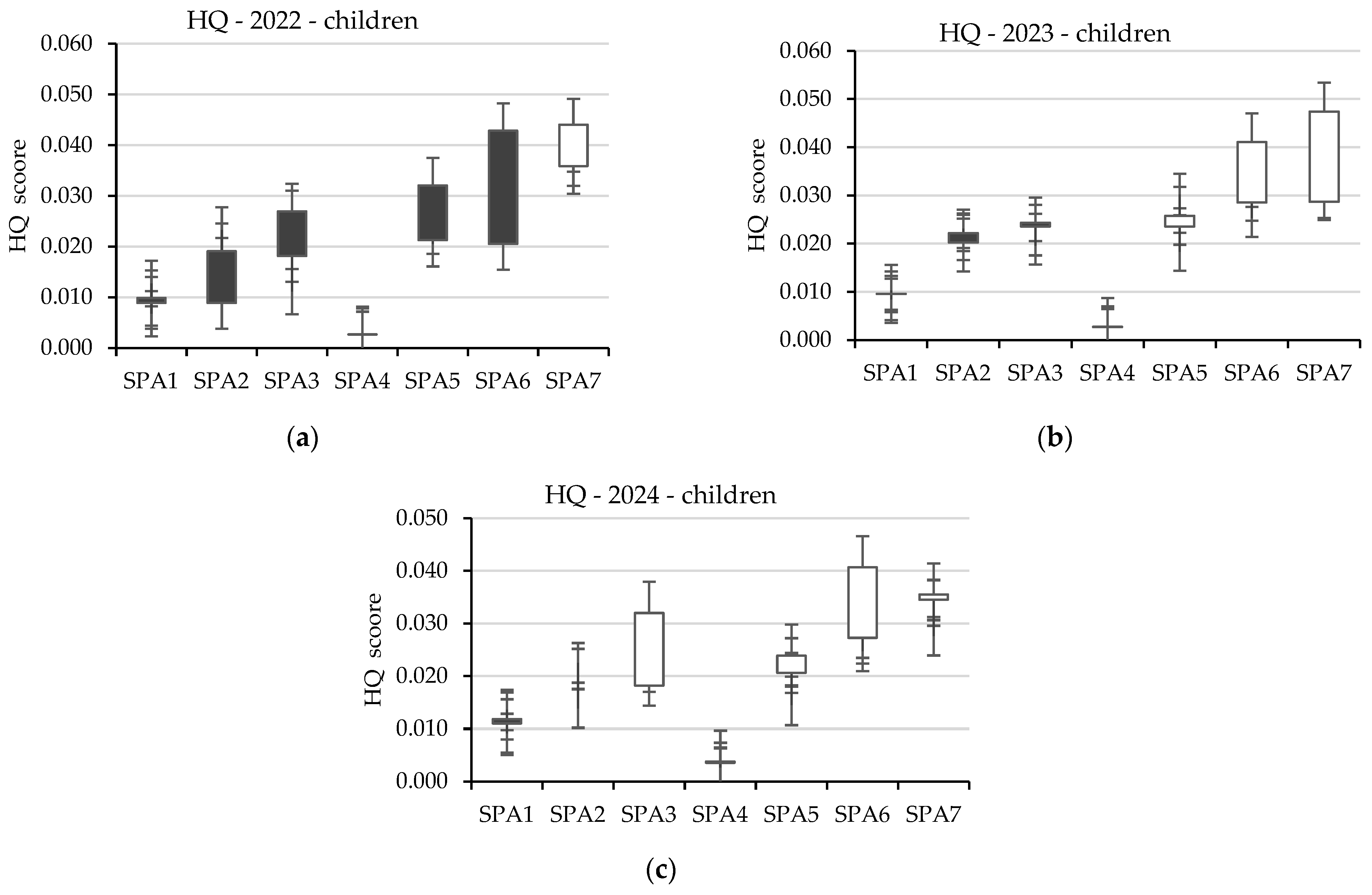

3.3. Risk Characterisation

4. Conclusions and Perspectives

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CDI | Chronic Daily Intake |

| EPA | U.S. Environmental Protection Agency |

| OPA | Overall Pollution Assessment |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| Cl | Chloride |

| EC | Electrical Conductivity |

| HI | Hazard Index |

| HQ | Hazard Quotient |

| NO2 | Nitrite |

| NO3 | Nitrate |

| NH4 | Ammonium |

| PI | Pollution Index |

| SO4 | Sulphate |

References

- WHO. Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality: Fourth Edition Incorporating the First and Second Addenda, 4th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; p. 614. [Google Scholar]

- UN. The Human Rights to Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation: Resolution/Adopted by the General Assembly. Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/4032820?v=pdf#files (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- WHO. Drinking-Water. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/drinking-water (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Ayejoto, D.A.; Egbueri, J.C. Human health risk assessment of nitrate and heavy metals in urban groundwater in Southeast Nigeria. Ecol. Front. 2024, 44, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarikar, S.; Vijaykumar, K. Assessment of Water Quality Index and Non-Carcinogenic Risk for Ingestion of Nitrate for Drinking Purpose of Bhosga Reservoir, Karnataka, India. Curr. World Environ. 2022, 17, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, T.; El-Sorogy, A.S. Health Risk Assessment of Nitrate and Fluoride in the Groundwater of Central Saudi Arabia. Water 2023, 15, 2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocca, D.; Lasagna, M.; Destefanis, E.; Bottasso, C.; De Luca, D.A. Human Health Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals and Nitrates Associated with Oral and Dermal Groundwater Exposure: The Poirino Plateau Case Study (NW Italy). Sustainability 2023, 16, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Singh, R.; Maurya, N.S. Modelling of corrosion rate in the drinking water distribution network using Design Expert 13 software. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 45428–45444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fetrat, S.; Islam, S. Investigation of the physicochemical parameters of drinking water in Herat province and its comparison with World Health Organization standards. Discov. Water 2024, 4, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, S.; Hailu, K.; Siraj, A.; Birhanu, B. Environmental isotopes (δ18O–δ2H, 222Rn) and electrical conductivity in backtracking sources of urban pipe water, monitoring the stability of water quality and estimating pipe water residence time. Front. Water 2023, 5, 1066055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sodani, K.A.A.; Maslehuddin, M.; Al-Amoudi, O.S.B.; Saleh, T.A.; Shameem, M. Efficiency of generic and proprietary inhibitors in mitigating Corrosion of Carbon Steel in Chloride-Sulfate Environments. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.G.; Nash, S.; Olbert, A.I. A review of water quality index models and their use for assessing surface water quality. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 122, 107218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapworth, D.J.; Baran, N.; Stuart, M.E.; Ward, R.S. Emerging organic contaminants in groundwater: A review of sources, fate and occurrence. Environ. Pollut. 2012, 163, 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijay, S.; Craswell, E. Fertilizers and nitrate pollution of surface and ground water: An increasingly pervasive global problem. SN Appl. Sci. 2021, 3, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Sanaullah, M.; Ullah, A.; Li, S.; Farooq, M. Nitrogen Pollution Originating from Wastewater and Agriculture: Advances in Treatment and Management. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2022, 260, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturwedi, A.K.; Kashyap, N.K.; Gupta, P.; Biswas, S.; Shriwas, S.K.; Vaishnav, M.M.; Hait, M. Industrial Effluents and their Impact on Water Pollution—An Overview. ES Gen. 2024, 5, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakida, F.T.; Lerner, D.N. Non-agricultural sources of groundwater nitrate: A review and case study. Water Res. 2005, 39, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasten-Zapata, E.; Ledesma-Ruiz, R.; Harter, T.; Ramirez, A.I.; Mahlknecht, J. Assessment of sources and fate of nitrate in shallow groundwater of an agricultural area by using a multi-tracer approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 470–471, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Nitrate and Nitrite in Drinking-Water. Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/wash-documents/wash-chemicals/nitrate-nitrite-background-document.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- de Vries, W. Impacts of nitrogen emissions on ecosystems and human health: A mini review. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2021, 21, 100249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossen Johnson, S. Methemoglobinemia: Infants at risk. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 2019, 49, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemmensen, P.J.; Schullehner, J.; Brix, N.; Sigsgaard, T.; Stayner, L.T.; Kolstad, H.A.; Ramlau-Hansen, C.H. Prenatal Exposure to Nitrate in Drinking Water and Adverse Health Outcomes in the Offspring: A Review of Current Epidemiological Research. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2023, 10, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, G.; Semprini, J. Early prenatal nitrate exposure and birth outcomes: A study of Iowa’s public drinking water (1970–1988). PLoS Water 2025, 4, e0000329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatseva, P.D.; Argirova, M.D. High-nitrate levels in drinking water may be a risk factor for thyroid dysfunction in children and pregnant women living in rural Bulgarian areas. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2008, 211, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, M.K.; Blount, B.C.; Valentin-Blasini, L.; Wapner, R.; Whyatt, R.; Gennings, C.; Factor-Litvak, P. CO-occurring exposure to perchlorate, nitrate and thiocyanate alters thyroid function in healthy pregnant women. Environ. Res. 2015, 143, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srour, B.; Chazelas, E.; Druesne-Pecollo, N.; Esseddik, Y.; de Edelenyi, F.S.; Agaesse, C.; De Sa, A.; Lutchia, R.; Debras, C.; Sellem, L.; et al. Dietary exposure to nitrites and nitrates in association with type 2 diabetes risk: Results from the NutriNet-Sante population-based cohort study. PLoS Med. 2023, 20, e1004149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitocco, D.; Zaccardi, F.; Di Stasio, E.; Romitelli, F.; Santini, S.A.; Zuppi, C.; Ghirlanda, G. Oxidative stress, nitric oxide, and diabetes. Rev. Diabet. Stud. 2010, 7, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, A.M. Nitrate and Nitrite in Drinking Water: A Toxicological Review. In Encyclopedia of Environmental Health; Nriagu, J.O., Ed.; Elsevier: Burlington, ON, Canada, 2011; pp. 137–145. [Google Scholar]

- Essien, E.E.; Said Abasse, K.; Cote, A.; Mohamed, K.S.; Baig, M.; Habib, M.; Naveed, M.; Yu, X.; Xie, W.; Jinfang, S.; et al. Drinking-water nitrate and cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health 2022, 77, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picetti, R.; Deeney, M.; Pastorino, S.; Miller, M.R.; Shah, A.; Leon, D.A.; Dangour, A.D.; Green, R. Nitrate and nitrite contamination in drinking water and cancer risk: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Environ. Res. 2022, 210, 112988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knobeloch, L.; Salna, B.; Hogan, A.; Postle, J.; Anderson, H. Blue babies and nitrate-contaminated well water. Environ. Health Perspect. 2000, 108, 675–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, K.H.; Jones, R.R.; Cantor, K.P.; Beane Freeman, L.E.; Wheeler, D.C.; Baris, D.; Johnson, A.T.; Hosain, G.M.; Schwenn, M.; Zhang, H.; et al. Ingested Nitrate and Nitrite and Bladder Cancer in Northern New England. Epidemiology 2020, 31, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M.H.; Jones, R.R.; Brender, J.D.; de Kok, T.M.; Weyer, P.J.; Nolan, B.T.; Villanueva, C.M.; van Breda, S.G. Drinking Water Nitrate and Human Health: An Updated Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schullehner, J.; Hansen, B.; Thygesen, M.; Pedersen, C.B.; Sigsgaard, T. Nitrate in drinking water and colorectal cancer risk: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 143, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. EPA. National Primary Drinking Water Regulations. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water/national-primary-drinking-water-regulations (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- WHO. Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality, 4th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; p. 631. [Google Scholar]

- Sailaukhanuly, Y.; Azat, S.; Kunarbekova, M.; Tovassarov, A.; Toshtay, K.; Tauanov, Z.; Carlsen, L.; Berndtsson, R. Health Risk Assessment of Nitrate in Drinking Water with Potential Source Identification: A Case Study in Almaty, Kazakhstan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 21, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.F.; Mitch, W.A. Drinking Water Disinfection Byproducts (DBPs) and Human Health Effects: Multidisciplinary Challenges and Opportunities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 1681–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neguez, S.; Laky, D. Byproduct Formation of Chlorination and Chlorine Dioxide Oxidation in Drinking Water Treatment. Period. Polytech. Chem. Eng. 2023, 67, 367–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backer, L.C.; Esteban, E.; Rubin, C.H.; Kieszak, S.; McGeehin, M.A. Assessing Acute Diarrhea from sulfate in drinking water. J.-Am. Water Work. Assoc. 2001, 93, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongpiachan, S.; Iijima, A.; Cao, J. Hazard Quotients, Hazard Indexes, and Cancer Risks of Toxic Metals in PM10 during Firework Displays. Atmosphere 2018, 9, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cankaya, S.; Varol, M.; Bekleyen, A. Hydrochemistry, water quality and health risk assessment of streams in Bismil plain, an important agricultural area in southeast Turkiye. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 331, 121874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golaki, M.; Azhdarpoor, A.; Mohamadpour, A.; Derakhshan, Z.; Conti, G.O. Health risk assessment and spatial distribution of nitrate, nitrite, fluoride, and coliform contaminants in drinking water resources of kazerun, Iran. Environ. Res. 2022, 203, 111850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goumenou, M.; Tsatsakis, A. Proposing new approaches for the risk characterisation of single chemicals and chemical mixtures: The source related Hazard Quotient (HQ(S)) and Hazard Index (HI(S)) and the adversity specific Hazard Index (HI(A)). Toxicol. Rep. 2019, 6, 632–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dippong, T.; Resz, M.A.; Tanaselia, C.; Cadar, O. Assessing microbiological and heavy metal pollution in surface waters associated with potential human health risk assessment at fish ingestion exposure. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 476, 135187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dippong, T.; Resz, M.A. Chemical Assessment of Drinking Water Quality and Associated Human Health Risk of Heavy Metals in Gutai Mountains, Romania. Toxics 2024, 12, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costea, M.; Gherasim, V. Anthropogenic changes in the geomorphological system. A case study: Sibiu depression (Sibiu–Tălmaciu sector), Transylvania, Romania. Acta Oecologica Carp. IV 2011, 4, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lazar, K. Tourism in the centre region, between statistical coordinates and master plan targets. Bull. Transilv. Univ. Braşov. Ser. V Econ. Sci. 2018, 11, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- SR ISO 5667-5:2017; Water Quality—Sampling—Part 5: Guidance for Sampling Drinking Water from Treatment Plants and Distribution Networks. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Greenacre, M.; Groenen, P.J.F.; Hastie, T.; D’Enza, A.I.; Markos, A.; Tuzhilina, E. Principal component analysis. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2022, 2, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanian Government. Regulation no. 7 from 25 January of 2023. Related to the Water Quality Destined for Human Consumption. Available online: https://www.dspbihor.gov.ro/legislatie/Ordonanta_7_din_%202023.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Dippong, T.; Török, I.; Tănăselia, C.; Resz, M.-A. Impact of water and sediment pollution in Valea Viseu river, Romania. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 195, 106796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panneerselvam, B.; Karuppannan, S.; Muniraj, K. Evaluation of drinking and irrigation suitability of groundwater with special emphasizing the health risk posed by nitrate contamination using nitrate pollution index (NPI) and human health risk assessment (HHRA). Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. Int. J. 2020, 27, 1324–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edet, A.E.; Offiong, O.E. Evaluation of water quality pollution indices for heavy metal contamination monitoring. A study case from Akpabuyo-Odukpani area, Lower Cross River Basin (southeastern Nigeria). GeoJournal 2002, 57, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Zhao, X.; Teng, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Wu, J.; Zuo, R. Groundwater nitrate pollution and human health risk assessment by using HHRA model in an agricultural area, NE China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2017, 137, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPA. Risk Assessment Guidance for Superfund Volume I: Human Health Evaluation Manual (Part E, Supplemental Guidance for Dermal Risk Assessment); EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; p. 156. [Google Scholar]

- EPA. Update for Chapter 3 of the Exposure Factors Handbook Ingestion of Water and Other Select Liquids; EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; p. 157. [Google Scholar]

- Zakir, H.M.; Sharmin, S.; Akter, A.; Rahman, M.S. Assessment of health risk of heavy metals and water quality indices for irrigation and drinking suitability of waters: A case study of Jamalpur Sadar area, Bangladesh. Environ. Adv. 2020, 2, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, C.; Ibrahim, S.; Sen Gupta, B. A survey of tap water quality in Kuala Lumpur. Urban Water J. 2007, 4, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Official Journal of the European Union. Directive (EU) 2020/2184 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2020 on the Quality of Water Intended for Human Consumption; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020; Volume 62, pp. 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.; Wang, S.; Wang, W.; Yin, S.; Lu, X.; Yu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X. Characteristic and spatial-temporal distribution of anthropogenic Chlorine emissions in Central China: An updated inventory. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 497, 145104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucheana, I.A.; Ihedioha, J.N.; Abugu, H.O.; Ekere, N.R. Water quality assessment of various drinking water sources in some urban centres in Enugu, Nigeria: Estimating the human health and ecological risk. Environ. Earth Sci. 2024, 83, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. EPA. 2018 Edition of the Drinking Water Standards and Health Advisories Tables. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2022-01/dwtable2018.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Schullehner, J.; Stayner, L.; Hansen, B. Nitrate, Nitrite, and Ammonium Variability in Drinking Water Distribution Systems. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Global Economy. Romania: Precipitation. Available online: https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/Romania/precipitation/#:~:text=The%20latest%20value%20from%202022,a%20liquid%20or%20a%20solid (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Trading Economics. Romania Average Precipitation. Available online: https://tradingeconomics.com/romania/precipitation (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Zheng, T.; Deng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, H.; Xie, X.; Gan, Y. Microbial sulfate reduction facilitates seasonal variation of arsenic concentration in groundwater of Jianghan Plain, Central China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 735, 139327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisht, M.; Shrivastava, M.; N Kumar, S.; Singh, R. Evaluation of the drinking water quality and potential health risks of nitrate and fluoride in Southwest Delhi, India. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2023, 104, 9652–9674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Yang, K.; Liu, T.; Yu, J.; Li, C.; Yang, D.; Hu, C.; Guo, L. Health risk assessment of nitrate pollution of drinking groundwater in rural areas of Suihua, China. J. Water Health 2023, 21, 1193–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnesota Department of Health. Nitrate Report for 2023–2024: Drinking Water Protection. Available online: https://www.health.state.mn.us/communities/environment/water/docs/contaminants/nitrpt20232024.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Ullengula, M.; Dhakate, R.; Gunnam, V.R.; Venkata, S. Appraisal of hydrochemistry and non-carcinogenic risk assessment for the distribution of Fluoride and Nitrate in a semi-arid region. Res. Sq. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 2022 | MAC * | SPA1 | SPA 2 | SPA 3 | SPA4 | SPA5 | SPA6 | SPA7 | Min | Max | Median |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | |||||||||||

| pH | 6.5–9.5 | 7.25 ± 0.25 | 8.60 ± 0.08 | 7.35 ± 0.17 | 6.90 ± 0.08 | 7.70 ± 0.07 | 7.43 ± 0.05 | 7.40 ± 0.08 | 6.80 | 8.70 | 7.40 |

| σ ** | 250 | 74.3 ± 8.30 | 1023 ± 48.2 | 400 ± 144 | 786 ± 35.1 | 904 ± 305 | 302 ± 61.8 | 740 ± 42.8 | 65.0 | 1268 | 703 |

| NO2 | 0.5 | 0.030 ± 0.0 | 0.030 ± 0.0 | 0.030 ± 0.0 | 0.030 ± 0.0 | 0.006 ± 0.003 | 0.004 ± 0.0 | 0.545 ± 0.35 | 0.004 | 0.80 | 0.03 |

| NO3 | 50 | 1.73 ± 0.45 | 3.10 ± 1.10 | 3.75 ± 1.37 | 0.49 ± 0.002 | 4.39 ± 0.97 | 5.23 ± 1.75 | 7.05 ± 0.67 | 0.49 | 7.98 | 3.72 |

| NH4 | 0.5 | 0.05 ± 0.0 | 0.05 ± 0.0 | 0.05 ± 0.0 | 0.06 ± 0.014 | 0.01 ± 0.004 | 0.01 ± 0.002 | 0.49 ± 0.18 | 0.007 | 0.70 | 0.05 |

| SO4 | 250 | 2.50 ± 0.43 | 45.0 ± 0.0 | 28.9 ± 13.9 | 104 ± 8.77 | 23.2 ± 7.84 | 20.1 ± 7.32 | 24.0 ± 0.0 | 1.88 | 113 | 22.1 |

| Cl | 250 | 3.07 ± 1.08 | 15.2 ± 0.0 | 41.1 ± 9.2 | 27.9 ± 1.47 | 197 ± 73.5 | 36.9 ± 10.7 | 8.13 ± 0.0 | 2.13 | 281 | 32.8 |

| 2023 | |||||||||||

| pH | 6.5–9.5 | 7.30 ± 0.22 | 8.65 ± 0.24 | 7.43 ± 0.05 | 7.00 ± 0.14 | 7.68 ± 0.12 | 7.38 ± 0.05 | 7.43 ± 0.24 | 6.80 | 8.80 | 7.40 |

| σ | 250 | 72.3 ± 4.92 | 1056 ± 12.8 | 423 ± 98.6 | 838 ± 10.4 | 897 ± 178 | 334 ± 58.3 | 760 ± 22.8 | 66.0 | 1113 | 729 |

| NO2 | 0.5 | 0.030 ± 0.0 | 0.030 ± 0.0 | 0.030 ± 0.0 | 0.030 ± 0.0 | 0.004 ± 0.001 | 0.004 ± 0.0 | 0.299 ± 0.09 | 0.002 | 0.43 | 0.03 |

| NO3 | 50 | 1.71 ± 0.14 | 3.91 ± 0.23 | 4.05 ± 0.38 | 0.49 ± 0.005 | 4.43 ± 0.89 | 5.75 ± 1.23 | 6.38 ± 1.56 | 0.49 | 8.59 | 4.10 |

| NH4 | 0.5 | 0.05 ± 0.0 | 0.05 ± 0.004 | 0.05 ± 0.0 | 0.05 ± 0.004 | 0.01 ± 0.003 | 0.01 ± 0.003 | 1.07 ± 0.65 | 0.007 | 1.64 | 0.05 |

| SO4 | 250 | 61.4 ± 0.85 | 54.8 ± 17.3 | 126 ± 16.6 | 26.9 ± 3.17 | 21.8 ± 2.33 | 139 ± 0.0 | 24.0 ± 0.0 | 19.8 | 139 | 30.4 |

| Cl | 250 | 1.78 ± 0.92 | 534 ± 733 | 42.36 ± 10.5 | 25.89 ± 0.50 | 174 ± 32.1 | 37.56 ± 10.2 | 5.75 ± 0.89 | 0.71 | 1053 | 31.8 |

| 2024 | |||||||||||

| pH | 6.5–9.5 | 7.28 ± 0.15 | 8.60 ± 0.01 | 7.43 ± 0.36 | 7.03 ± 0.05 | 7.45 ± 0.11 | 7.26 ± 0.06 | 7.48 ± 0.05 | 6.90 | 8.60 | 7.40 |

| σ | 250 | 76.7 ± 9.50 | 1045 ± 1.00 | 449 ± 125 | 811 ± 15.0 | 1066 ± 476 | 301 ± 44.9 | 754 ± 11.1 | 67.0 | 1516 | 740 |

| NO2 | 0.5 | 0.030 ± 0.0 | 0.030 ± 0.0 | 0.030 ± 0.0 | 0.030 ± 0.0 | 0.004 ± 0.0 | 0.004 ± 0.0 | 0.323 ± 0.16 | 0.004 | 0.49 | 0.03 |

| NO3 | 50 | 2.06 ± 0.33 | 3.49 ± 0.85 | 4.33 ± 1.09 | 0.58 ± 0.10 | 3.74 ± 0.79 | 5.38 ± 1.34 | 5.98 ± 0.66 | 0.49 | 7.37 | 3.87 |

| NH4 | 0.5 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.05 ± 0.008 | 0.05 ± 0.0 | 0.05 ± 0.0 | 0.01 ± 0.004 | 0.01 ± 0.002 | 1.28 ± 0.23 | 0.006 | 1.53 | 0.05 |

| SO4 | 250 | 4.3 ± 0.0 | 44.5 ± 0.0 | 62 ± 0.0 | 80.2 ± 0.0 | 19.6 ± 7.09 | 18.7 ± 1.97 | 20.0 ± 0.0 | 4.30 | 80 | 20.4 |

| Cl | 250 | 40.5 ± 55.9 | 524 ± 732 | 63.7 ± 0.0 | 406 ± 565 | 130 ± 1.06 | 30.2 ± 7.16 | 7.0 ± 0.0 | 0.96 | 1041 | 34.4 |

| 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PINO3 | PINO2 | PINH4 | PINO3 | PINO2 | PINH4 | PINO3 | PINO2 | PINH4 | |

| SPA1 | 0.965 ** | −0.940 * | −0.900 * | 0.966 ** | −0.940 * | −0.900 * | 0.959 ** | −0.940 * | −0.877 * |

| SPA2 | 0.938 ** | −0.940 * | −0.900 * | 0.922 ** | −0.940 * | −0.894 * | 0.945 ** | −0.940 * | −0.892 * |

| SPA3 | 0.925 ** | −0.940 * | −0.900 * | 0.919 ** | −0.940 * | −0.900 * | 0.913 ** | −0.940 * | −0.899 * |

| SPA4 | 0.990 ** | −0.940 * | −0.884 * | 0.990 ** | −0.940 * | −0.897 * | 0.988 ** | −0.940 * | −0.900 * |

| SPA5 | 0.912 ** | −0.989 * | −0.980 * | 0.911 ** | −0.993 * | −0.975 * | 0.925 ** | −0.992 * | −0.982 * |

| SPA6 | 0.895 ** | −0.992 * | −0.979 * | 0.885 ** | −0.992 * | −0.980 * | 0.892 ** | −0.992 * | −0.957 * |

| SPA7 | 0.859 ** | 0.090 ** | −0.017 * | 0.872 ** | −0.402 * | 1.133 *** | 0.880 ** | −0.355 * | 1.564 *** |

| Variables | OPA | EC | pH | Cl− | NH4 | NO2 | NO3 | SO4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPA | 1 | 0.264 | −0.115 | −0.340 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.694 | 0.030 |

| EC | 0.264 | 1 | 0.507 | −0.014 | 0.274 | 0.252 | 0.155 | 0.326 |

| pH | −0.115 | 0.507 | 1 | 0.067 | −0.126 | −0.102 | 0.411 | −0.569 |

| Cl | −0.340 | −0.014 | 0.067 | 1 | −0.347 | −0.333 | −0.156 | 0.035 |

| NH4 | 1.000 | 0.274 | −0.126 | −0.347 | 1 | 0.999 | 0.678 | 0.052 |

| NO2 | 1.000 | 0.252 | −0.102 | −0.333 | 0.999 | 1 | 0.712 | 0.005 |

| NO3 | 0.694 | 0.155 | 0.411 | −0.156 | 0.678 | 0.712 | 1 | −0.541 |

| SO4 | 0.030 | 0.326 | −0.569 | 0.035 | 0.052 | 0.005 | −0.541 | 1 |

| Children | Adults | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HQNO3 | HQNO3 | |||||

| average | min | max | average | min | max | |

| 2022 | 0.27575 | 0.00480 | 0.00048 | 0.0722 | 0.0096 | 0.1567 |

| 2023 | 0.2863 | 0.0365 | 0.64455 | 0.075 | 0.0096 | 0.1688 |

| 2024 | 0.2743 | 0.0365 | 0.5527 | 0.0718 | 0.0096 | 0.1448 |

| HQNO2 | HQNO2 | |||||

| 2022 | 0.11563 | 0.00480 | 0.96240 | 0.0303 | 0.0013 | 0.2521 |

| 2023 | 0.07311 | 0.0024 | 0.5112 | 0.0191 | 0.0006 | 0.1339 |

| 2024 | 0.0788 | 0.0048 | 0.5880 | 0.0206 | 0.0013 | 0.154 |

| CDINO3 (mg/kg × day) | CDINO3 (mg/kg × day) | |||||

| 2022 | 0.44119 | 0.00288 | 0.9574 | 0.11555 | 0.0153 | 0.2507 |

| 2023 | 0.4581 | 0.0584 | 1.0313 | 0.11998 | 0.0153 | 0.2701 |

| 2024 | 0.4389 | 0.0584 | 0.8844 | 0.11494 | 0.0153 | 0.2316 |

| CDINO2 (mg/kg × day) | CDINO2 (mg/kg × day) | |||||

| 2022 | 0.01156 | 0.00048 | 0.09624 | 0.00302 | 0.000126 | 0.0252 |

| 2023 | 0.00731 | 0.00024 | 0.05112 | 0.00191 | 6.286 × 10−5 | 0.01339 |

| 2024 | 0.00788 | 0.00048 | 0.0588 | 0.00206 | 0.000126 | 0.0154 |

| HI | HI | |||||

| 2022 | 0.39138 | 0.07252 | 1.5608 | 0.1025 | 0.01899 | 0.4087 |

| 2023 | 0.3594 | 0.07252 | 1.1557 | 0.0941 | 0.01899 | 0.3027 |

| 2024 | 0.3531 | 0.07252 | 1.0703 | 0.0925 | 0.01899 | 0.2803 |

| Dermal Contact Exposure in Children | Dermal Contact Exposure in Adults | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| average | min | max | average | min | max | |

| 2022 | ||||||

| Winter | 0.024192 | 0.002704 | 0.042819 | 0.008200212 | 0.000916479 | 0.014514028 |

| Spring | 0.019381 | 0.002687 | 0.039233 | 0.006569254 | 0.000910867 | 0.013298291 |

| Summer | 0.019807 | 0.002687 | 0.03644 | 0.006713807 | 0.000910867 | 0.012351886 |

| Autumn | 0.01777 | 0.002687 | 0.044022 | 0.007077238 | 0.000910867 | 0.014921767 |

| 2023 | ||||||

| Winter | 0.019925257 | 0.002687234 | 0.028676699 | 0.006753886 | 0.000910867 | 0.009720284 |

| Spring | 0.019181124 | 0.002687234 | 0.035000251 | 0.006501654 | 0.000910867 | 0.011863721 |

| Summer | 0.020819162 | 0.002687234 | 0.031948834 | 0.007056885 | 0.000910867 | 0.01082941 |

| Autumn | 0.024337239 | 0.002742413 | 0.047421119 | 0.008249376 | 0.000929571 | 0.016073912 |

| 2024 | ||||||

| Winter | 0.019617829 | 0.003581139 | 0.034514673 | 0.00664968 | 0.001213866 | 0.011699129 |

| Spring | 0.019022681 | 0.002703787 | 0.03438776 | 0.006447948 | 0.000916479 | 0.011656111 |

| Summer | 0.018228887 | 0.002687234 | 0.027589666 | 0.006178882 | 0.000910867 | 0.009351822 |

| Autumn | 0.024467436 | 0.003785302 | 0.040667168 | 0.008293507 | 0.00128307 | 0.013784586 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Resz, M.-A.; Blăjan, O.; Călugăru, D.; Crucean, A.; Kovacs, E.; Roman, C. Integrating Multi-Index and Health Risk Assessment to Evaluate Drinking Water Quality in Central Romania. Water 2026, 18, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010023

Resz M-A, Blăjan O, Călugăru D, Crucean A, Kovacs E, Roman C. Integrating Multi-Index and Health Risk Assessment to Evaluate Drinking Water Quality in Central Romania. Water. 2026; 18(1):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010023

Chicago/Turabian StyleResz, Maria-Alexandra, Olimpiu Blăjan, Dorina Călugăru, Augustin Crucean, Eniko Kovacs, and Cecilia Roman. 2026. "Integrating Multi-Index and Health Risk Assessment to Evaluate Drinking Water Quality in Central Romania" Water 18, no. 1: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010023

APA StyleResz, M.-A., Blăjan, O., Călugăru, D., Crucean, A., Kovacs, E., & Roman, C. (2026). Integrating Multi-Index and Health Risk Assessment to Evaluate Drinking Water Quality in Central Romania. Water, 18(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010023