Abstract

Coastal areas are strategically significant from an ecological, anthropic, and economic point of view, but they are also susceptible to forces causing inundations. Multiple forcings occurring in close succession in space and time amplify the effects of a single force and form a compound event. An example is an atmospheric disturbance that extends from the sea to the mainland, causing a sea storm and a river flood due to heavy rainfall. This condition can occur in geomorphological contexts where the sea and mountains are close to each other, and the river basins are small. Most research on compound events focuses on extreme events; detailed studies of compound events not associated with extreme events and generated by non-exceptional atmospheric disturbances are scarce. Furthermore, there are very few detailed studies focusing solely on compound river floods and sea storms. Consequently, this paper is focused on compound river floods and sea storms generated by atmospheric disturbances regardless of their exceptional or non-typical typology. This analysis includes their forcings, correlation, and effects and is carried out in Calabria, a region of Southern Italy that represents an interesting case study due to its geomorphological, climatic, and hydrological peculiarities, which favor the formation of compound events, and, due to the considerable anthropization of its coastal territories, increases their risk. The main findings concern confirming that the existence of this compound event between river floods and sea storms is generated by the same atmospheric disturbance, the geomorphological conditions under which it occurs, and the main driving forces behind it. Therefore, this study is only the first step in a more in-depth analysis that will also examine the quantitative aspects of these phenomena. This analysis is essential for the planning and management of coastal areas subject to compound events and for ensuring effective mitigation measures.

1. Introduction

To date, more than 600 million people live in coastal areas worldwide, and this number is expected to increase to 1 billion by 2050 [1]. Therefore, coastal areas are of the utmost relevance from ecological, anthropic, and economic points of view. These areas are often susceptible to river and marine hazards that lead to flooding, especially in areas characterized by a complex coastal orography with mountains very close to the coast [2]. The main marine forcings are tide excursions, storm surges, and sea storms, while the main river forcings are heavy rainfall, dams, and embankment collapse or breach. When more than one flood hazard occurs simultaneously in space and time or in close succession, it can be considered a compound event that can amplify the effects produced by a single force [3]. Zscheischler et al. [4] classified compound weather and climate events by typology. Some examples are related to atmospheric disturbances extending from the sea to the land, causing flood inundation induced by river flow and storm surges [5], heavy rainfall and storm surges [6], or river floods and sea storms [7]. In many cases, compound events are not extreme if they occur individually, but their combination becomes catastrophic [8,9]. The possible damage caused by compound events increases in the presence of inhabited centers and infrastructure and in the context of global climate change [10,11].

River and marine forcings have been separately studied by means of hydrodynamic models for marine forcings and hydrological/hydraulic models for river forcings [12]. Indeed, these models often neglect the interaction between these forcings [13]. Furthermore, recently, there has been a growing interest in the issue of compound flooding due to the increased occurrences of storms and heavy precipitation in coastal areas [14]. Many studies focus on extreme events such as tropical cyclones, typhoons, and hurricanes, which can cause rainfall, river flow, storm surges, and sea storms at the same time. For example, Silva-Araya et al. [15] proposed a dynamic modeling of surface runoff and storm surge during hurricane and tropical storm events. Valle-Levinson et al. [16] analyzed the compound flooding in Houston’s Galveston Bay during Hurricane Harvey. Liu et al. [17] assessed tropical cyclone compound flood risk in China using hydrodynamic modeling. Xu et al. [18] analyzed the compound flood impact of water level and rainfall during the tropical cyclone period in Shanghai. Di Bacco et al. [19] explored the compound nature of coastal flooding by tropical cyclones through a machine learning framework. Lin et al. [20] characterized the compound flood drivers due to Typhoon Hato (2017) in the Pearl River Estuary. Zeng et al. [21] analyzed the compound floods induced by rainstorms and storm tides during super typhoon events in China in the context of sea-level-rise scenarios. Zhang et al. [22] quantified the compound effects caused by the interactions between the inland river system and coastal processes in Hurricane Tal flooding through controlled hydrodynamic modeling experiments. In many cases, compound floods are analyzed from a statistical-probabilistic and numerical point of view [23,24,25]. Other widely analyzed topics concern the impact of compound floods in low-lying coastal areas, especially in the presence of river mouths and estuaries, and the generation mechanisms of the compound floods caused by two or more forcings, often to evaluate the relative flood risk. Among these, Hendry et al. [26] assessed the characteristics and drivers of compound flooding events around the UK coast; Zellou and Rahali [27] assessed the joint impact of extreme rainfall and storm surge on the risk of flooding in coastal areas; Fang et al. [28] analyzed dependence, drivers, and impacts of compound flood from storm surge and heavy precipitation in China; Leijnse et al. [29] analyzed fluvial, pluvial, tidal, wind- and wave-driven processes of compound coastal flooding; Lu et al. [30] assessed the compounding effects of fluvial flooding and storm tides on coastal flooding risk in China; Gao et al. [31] modeling the compound floods upon combined rainfall and storm surge events in a low-lying coastal city; and Wang et al. [32] assessed the compound effects in complex estuary under various combination patterns of storm surge and fluvial floods. Another important related topic concerns the interaction between water masses coming from opposite directions. Indeed, the runoff generated in rivers by precipitation generally flows to the sea while the waves move in opposite directions. However, in the presence of high tide, a jacking effect is generated, which hinders the regular river flow into the sea [33]. A significant consequence of this effect is that the intensity of coastal floods can be greatly increased by heavy precipitation and high tide occurring concurrently or in close succession, and the potential damage increases in the presence of infrastructure and inhabited centers [34].

The Mediterranean areas are susceptible to intense atmospheric disturbances, which, in some cases, are similar in terms of characteristics to hurricanes [35,36]. Among these areas, one of the most peculiar for these events is Italy, due to both its geographical location in the center of the Mediterranean and its complex geomorphology [37,38]. The events are more frequent in the autumn months, due to the strong temperature gradients between perturbations containing cold air fronts and the still very warm Mediterranean Sea surface [39], and are facilitated by the presence of tropical depressions in the subtropical Atlantic region [40]. Indeed, the Mediterranean climate is temperate, according to the Köppen climate classification. It is particularly dry in the summer and mild in the winter. Rainfall is concentrated from autumn to spring, and, during late summer and autumn, in the western Mediterranean Sea, there is a frequent and intense convective activity like that observed in tropical contexts, which is facilitated by a combination of complex topography and proximity to the sea and causes convective cells associated with intense rainfall events [41,42]. In addition to convective precipitation, the Mediterranean Sea is also subject to precipitation of an orographic nature, especially in areas with mountains very close to the sea, and to precipitation of a cyclonic nature due to the ease with which warm and humid air masses can collide with cold air masses. Indeed, coastal relief is important due to a combination of two main mechanisms: the orographic effects, which increase precipitation and facilitate convection, and the topographic effect, which favors a rapid concentration of the streamflow [43].

Regarding Italy, Sioni et al. [40] highlighted some important aspects of the development of extreme precipitation events, identifying important precursors and moisture sources. They analyzed the flood event of November 1966 and the Vaia storm of October 2018, which was triggered by a vast low-pressure center that extended over the western Mediterranean Sea and moved eastward, impacting with a rapid inflow of cold air from the northwest. These conditions caused cyclogenesis [44,45], which, in the examined cases, achieved baric minima of 994 hPa in 1966 [46] and 977 hPa in 2018 [47]. Cavaleri et al. [38] focused on the wave conditions related to the Vaia storm, which was characterized by very intense wind and high waves.

Considering compound events, an accurate knowledge of the mechanisms that trigger them and of the dependence and correlation between their forces is essential for the planning and management of coastal areas. In addition, identifying the areas subject to compound river floods and sea storm events allows us to obtain an overview of the anthropogenic elements most exposed to these events, which can act as points of possible crisis during future events. This information can be useful in emergency management planning, for the definition of prevention and mitigation measures, and to improve the consciousness of the population of the risks affecting the areas where they live [48].

Therefore, the existing literature focuses primarily on compound events associated with extreme events such as hurricanes, tropical cyclones, and typhoons [49]. In all of these cases, storm surge plays a significant role and has been widely studied. However, detailed studies of compound events not associated with extreme events and generated by non-exceptional atmospheric disturbances are lacking. Furthermore, there are very few detailed studies focusing solely on compound river floods and sea storms.

Consequently, the paper analyzes the issue of compound river floods and sea storms, analyzing the generation mechanisms and river and marine forcings and their correlation, considering the sea storms as the only marine forcing. The paper also analyses the effects of these compound events, especially at river mouths subject to the jacking effect caused not by high tide but by sea storm waves. These analyses are carried out in Calabria, a region of Southern Italy that represents an interesting case study due to its geomorphological, climatic, and hydrological peculiarities that favor the development of compound events and due to the considerable anthropization of its coastal territories.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area Description

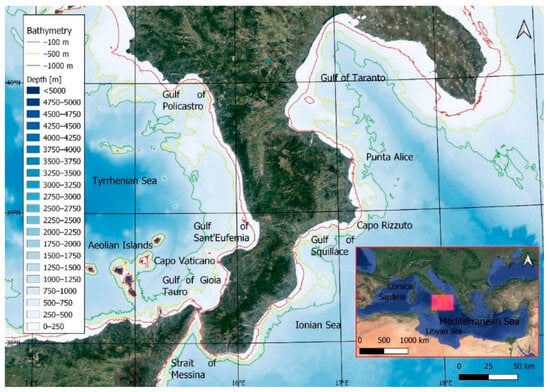

Calabria is a region of Southern Italy located at latitudes between 38° and 40° N and longitudes between 15° and 17° E in the center of the Mediterranean Sea, with an area over 15,000 km2 (Figure 1). Calabria is an interesting case study from the point of view of compound river floods and sea storms due to its geomorphological, climatic, hydrological, and anthropic peculiarities. A description of these peculiarities and how their interactions influence the compound river floods and sea storm events is provided below and in Section 4.

Figure 1.

Location of Calabria, which is in the center of the Mediterranean Sea.

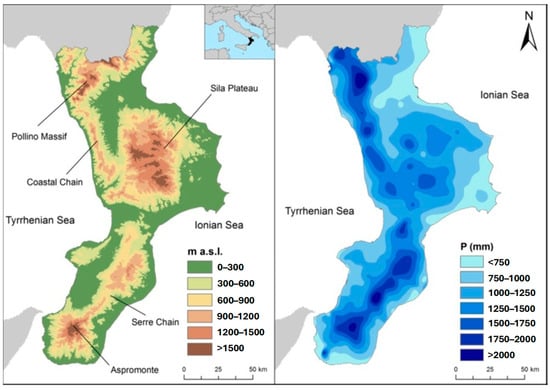

From the geomorphological point of view, Calabria is shaped like a peninsula with a notable coastal length, over 700 km, and a particularly rugged morphology, with numerous mountains very close to the sea and the Apennines dividing Calabria into two sides: Ionic to the east, and Tyrrhenian to the west. These two seas differ significantly in terms of bathymetry and depth. Indeed, the Tyrrhenian Sea is generally characterized by greater slopes than the Ionian Sea, especially nearshore. The rugged morphology is such that over 90% of the Calabrian territory is mountainous (>500 m a.s.l.) or hilly (50–500 m a.s.l.), and less than 10% of the Calabrian territory is flat (<50 m a.s.l.), with maximum and average elevations of over 2250 m and about 600 m. a.s.l., respectively (Figure 2 Left). The main massifs are the Pollino, the Sila, and the Aspromonte, located in the northern, central, and southern parts, respectively, and all with a maximum altitude of the order of 2000 m a.s.l.; the Serre Chain, located in the central–southern part and with a maximum altitude of the order of 1500 m a.s.l.; and the Costiera Chain which is located a short distance from the northern Tyrrhenian coast and has a maximum height of over 1500 m a.s.l. This morphology is caused by a still-active tectonic uplift that started in the Quaternary [50]. One consequence of this uplift concerns the formation of a very fragmented river system, with numerous small basins and a predominantly ephemeral hydrological regime, which will be described in detail below. In fact, in Calabria, there are about 900 river basins, of which only 2 have an area greater than 1000 km2, 23 have an area between 100 and 1000 km2, 120 have an area between 10 and 100 km2, and the remaining (about 750, over 80%) have an area of less than 10 km2. Therefore, the average area of the Calabrian basins is just over 1.5 km2.

From a climatic point of view, due to its geomorphological peculiarities, Calabria is characterized by a notable climatic variability with a mountain climate in the inland areas and a typically dry-summer subtropical climate, also known as the Mediterranean climate, along the coasts. Rainfall is frequent in winter, with snowfall at the highest elevations, but is less frequent during the summer, except for some occasional thunderstorms. The average annual rainfall is about 1100 mm, ranging between 1400 and 1800 mm in mountainous areas, with a maximum of about 2000 mm in the Serre, between 700 and 1000 mm on the Tyrrhenian coast, and about 500 mm on the Ionian coast, as shown in Figure 2, Right [51,52]. About the wave climate, both coasts are characterized by fetch lengths in the order of hundreds of kilometers up to a thousand, and the Ionian coasts are mainly exposed to the winds from Scirocco (southeast), and Grecale (northeast), while the Tyrrhenian coasts are mainly exposed to the winds of the Mistral (northwest). These different climatic conditions and exposure to winds cause considerable variability in terms of sea events affecting the various coastal areas. Indeed, in the Tyrrhenian Sea, the stormy wave conditions are concentrated along a few directions, coming mainly from the Mistral (northwest). Instead, in the Ionian Sea, the intense wave conditions can come from different directions, varying between northeast and southeast. From the seasonal point of view, in autumn on most of the Calabrian coasts, the maximum significant wave height values of sea storms are higher than in winter [53,54]. In addition, Calabria is a microtidal environment, so tidal excursion is negligible [55].

Considering the hydrological point of view, Calabrian rivers (also called “fiumare”) [56,57] are generally characterized by a hydrological regime typical of ephemeral rivers, which convey flow only during a rainfall event, often of the flash flood type. Only 20 rivers out of 900 have a fluvial hydrological regime, while the others have a hydrological regime typical of fiumare. In addition, Calabrian rivers are often characterized by coarse sedimentology. Thus, many beaches downstream of the fiumare are characterized by coarse sedimentology, especially on the Ionian coast. This hydrological regime, combined with this sedimentology, can cause solid transport of high number of entities. Consequently, this transport influences the shoreline evolution near river mouths.

From the anthropic point of view, after the end of the Second World War, a considerable migration from inland to coastal areas was observed in most of the coastal territories in the Mediterranean areas [58] and especially in Italy [59]. In this latter case, the anthropogenic pressure of the last 70 years in Calabria caused a considerable increase both in the number of inhabited centers near the shoreline, from 32 in the 1950s to 83 today, and in their area, from about 15 km2 in the 1950s to more than 250 km2 today. This anthropogenic pressure also caused disorganized and unplanned urban growth in various Calabrian coastal and river areas, especially along the northern Tyrrhenian coast and near the Strait of Messina, while on the Ionian coast, the main effect of anthropization concerns the construction of railways and highways very close to the sea [60,61].

Figure 2.

On the left: digital elevation model of Calabria. To the right: regional distribution of the average annual rainfall (P). Small box: localization of the Calabria region (in black) in Europe (in grey) and the Mediterranean Sea (in blue) (source: [62]).

2.2. Methodology

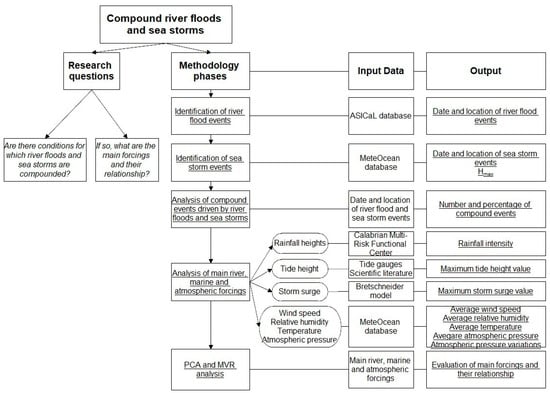

The methodology described below is a data-driven type and aims to provide answers to two research questions. The first concerns the assessment of existing conditions that lead to river floods and sea storms contemporarily. The second one concerns an evaluation of the main forcings, and their relationship, using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Multivariate Regression (MVR).

The applied methodology was divided into the following phases (Figure 3), with a previous data collection phase:

Figure 3.

Flowchart of the applied methodology. The main issues are bold, the research questions are italics, and the phases of the methodology and outputs are underlined.

- Identification of the river flood events.

- Identification of the sea storm events.

- Analysis of compound events driven by river floods and sea storms.

- Analysis of main river, marine, and atmospheric forcings.

- PCA and MVR analysis.

2.2.1. Data Collection

This section describes all the data used in the four phases of the methodology. In the first phase, the ASICal database of the National Research Council—Institute for Geo-Hydrological Protection (CNR-IRPI, Italian acronym) was examined. ASICal is a database that contains data on over 10,000 landslides and flood damage events that occurred in Calabria since the end of the 1700s, aggregated at the municipal scale [63]. These data are collected through different historical sources, including post-event field surveys, reports from public offices and agencies, and local and national newspapers. In many cases, no coding procedures have been defined. This database focuses on direct damage, defined as damage due to direct physical contact with the hazard, i.e., the physical destruction of buildings, infrastructure, or other assets at risk. Fatalities and human injuries are included in this definition [64,65]. For each event, the date, location, and qualitative information of the damage caused by the event itself are available, but quantitative information is missing.

In the second and third phases, the MeteOcean database developed by the University of Genoa research team (http://www3.dicca.unige.it/meteocean/hindcast.html, accessed on 20 September 2024) was examined to analyze sea storm events and the main marine and atmospheric forcings. This research team has performed a reanalysis of atmospheric and wave conditions, producing a hindcast database that starts from January 1979 until today. The MeteOcean database has been reconstructed from the Climate Forecast System Reanalysis (CFSR) database through a numerical model, which consists of a meteorological model for the reanalysis and the simulation of winds and atmospheric fields, and a third-generation model for the description of the generation and the propagation of wind and swell waves in the Mediterranean basin. In detail, the wind forcing provided by the 10 m wind fields was obtained using the non-hydrostatic mesoscale model Weather Research and Forecasting with the Advanced Research solver (WRF-ARW). The wave conditions were analyzed using the third-generation wave model WavewatchIII. In addition, the Mediterranean basin was discretized into a regular grid with a resolution of 0.1273 × 0.09 degrees, corresponding almost to 10 km at the latitude of 45° N [66]. Therefore, a time series of wave and climate parameters such as significant wave height, mean and peak periods, wave and wind direction, wind speed, temperature, pressure, humidity, etc., is available for each point of this grid.

At this stage, other data sources were also considered to analyze tide height and rainfall. In detail, the tide height was estimated based on recorded data and the scientific literature. The recorded data were analyzed from the tide gauges available in the study area, located at Reggio Calabria and Crotone. The data from the scientific literature were taken from Sannino et al. [55] and the Tide Tables of the Italian Marine Hydrographic Institute [67]. Regarding rainfall, the time series of hourly rainfall height data available in the Multi-Risk Functional Center of the Regional Agency for Environmental Protection of Calabria was analyzed. This database contains time series of rainfall and river discharge recorded by gauges in Calabria. Specifically, there are over 300 rainfall gauges with up to 100 years of data, ensuring adequate spatial and temporal coverage. However, there are only a few dozen river discharge gauges, each with only a few years of data, which does not represent a significant sample.

2.2.2. Identification of the River Flood Events

River flood events were identified starting from the ASICal database [62,63]. The point of interest in this database concerns river floods triggered by rainfall events. As described above, this database only includes events that cause damage. However, quantitative information regarding flow rates, total heights, intensity, and duration of the rainfall event and damage magnitude of the flood event is not available. From a spatial perspective, only coastal municipalities were considered, while from a temporal perspective, the analyzed time interval extends from 1979 to today, according to wave data availability, as explained below. Therefore, the output of this phase concerns only the date and location of river flood events that caused damage in the Calabrian coastal municipalities from 1979 to the present.

2.2.3. Identification of the Sea Storm Events

Sea storm events were identified from the MeteOcean database. Due to the considerable length of Calabria’s coastline, it was necessary to identify over 50 grid points located off the coast of Calabria (on average, 1 every 15 km of coast), each of them representative of the nearby coastal area. Time series of significant wave height and wave direction were analyzed for each point. To identify sea storms within the time series, the criterion of Boccotti [68] was adopted. This criterion states that a sea storm is a succession of sea states where the significant wave height exceeds a critical threshold and does not go below it for time durations greater than a critical threshold. The critical threshold of the significant wave height is equal to 1.5 times the average significant wave height of the analyzed locality [69], while the critical time threshold in the Mediterranean Sea is equal to 12 h [68]. Therefore, the output of this phase concerns the date and location of each sea storm and its maximum significant wave height Hsmax.

2.2.4. Analysis of Compound Events Driven by River Floods and Sea Storms

The analysis phase for compound river flood and sea storm events is based on input data from the first two phases and considers two conditions, geographic and temporal. The first one requires that river floods and sea storms occur in the same coastal area. The second one requires that a sea storm event occur on the same day as a river flood event or in the previous and following days. The choice to examine a time interval of 3 days is related to two main factors. The first of these relates to the temporal duration of sea storms, often of the order of days, which is generally greater than rainfall events. The second factor is related to the uncertainty in the encoding of rainfall event date in the ASICal database. These uncertainties are greater for past events, where scientific and homogeneous coding criteria were missing. An example of uncertainty is an event that started just before midnight and lasted a few hours, which, in the absence of a classification code, can be classified as occurring on the day when the event started or on the day when the event ended. The output of this phase concerns the number and percentage of compound events, aggregated on a regional scale and by Ionian and Tyrrhenian macro-area.

2.2.5. Analysis of Main River, Marine, and Atmospheric Forcings

In this phase, the main river, marine, and atmospheric forcings were analyzed to evaluate their importance and influence on river floods and sea storms and on the atmospheric disturbances that generate them.

Regarding river forcing, only rainfall was analyzed since, as described above, statistically significant time series of flow rates are not available in almost all coastal areas of Calabria. The output of this sub-phase concerns the rainfall intensity.

Considering marine forcings, high tide height and storm surge due to wind and the barometric effect were analyzed. In detail, the high tide height was analyzed through gauge recordings available in the study area and literature sources, while, as regards the storm surge, those caused by both the wind and the barometric effect were analyzed. The first one was estimated by applying the Bretschneider [70] model, which depends on the length of the wind fetch, the wind drag coefficient, and the depths at the shelf edge and near the coast. The second one depends on the minimum atmospheric pressure value recorded during an atmospheric disturbance, and it is estimated by observing that a decrease in the atmospheric pressure of 1 mbar, as compared with the normal value of 1013 mbar, causes a surge of 1 cm. The output of this sub-phase concerns the maximum tide height and the maximum storm surge values.

About atmospheric forcings, horizontal and vertical components of wind speed, relative humidity at 2 m, temperature at 2 m, and atmospheric pressure at 2 m were analyzed starting from the MeteOcean database for the same time interval as the wave data. The output of this sub-phase is the wind direction, obtained from the horizontal and vertical components of the wind speed, the average values, named average wind speed vw, average relative humidity Um, average temperature Tm, and average atmospheric pressure Pm, and the atmospheric pressure variation ∆P. This last parameter estimates the drop in atmospheric pressure during an atmospheric disturbance. Furthermore, all forcings were normalized.

2.2.6. PCA and MVR Analysis

The last phase was developed by applying the PCA and MVR techniques to analyze the relationship between the main forcings and to reduce their number by neglecting the redundant ones. Generally, PCA is a widely used statistical technique for analyzing large datasets containing a high number of dimensions/features per observation and reducing their dimensionality and redundant variables. PCA is accomplished by linearly transforming the data into a new coordinate system where most of the variation in the data can be described with fewer dimensions than the initial data. Therefore, by applying this technique, it is possible to identify relationships among the variables, which allows for defining a certain phenomenon, reducing their number by neglecting the redundant variables, and defining the new variables as a linear combination of the original variables, e.g., a multiple linear regression, giving a more comprehensive interpretation of the phenomenon [71]. MVR is a technique used to determine the relationship between independent and dependent variables and to explain the effect of several independent variables (predictors) on the dependent variable. Once the Multivariate Regression is applied to the dataset, this method is then used to predict the behavior of the response variable based on its corresponding predictor variables. Positive values indicate that the variable and principal components are positively correlated, and an increase in one causes an increase in the other. Negative values indicate a negative correlation. Large (either positive or negative) values indicate that a variable has a strong effect on that principal component.

In this case, as a representative river flood event forcing, rainfall intensity i was chosen, while, as a representative sea storm event forcing, maximum significant wave height Hsmax was chosen. Furthermore, two groups of forcings related to the atmospheric disturbances that generate river flood and sea storm events were considered to analyze their relationship. The first group included Um, ∆P, vw, and Tm, while the second group included Um, Pm, vw, and Tm. The two groups differ in a single forcing, the atmospheric pressure, which is considered in one group in terms of average value, and the other group in terms of variation. This choice is related to the importance of atmospheric pressure in atmospheric disturbance generation. In fact, the formation of clouds and precipitation occurs in areas subject to low-pressure fields, while the intensity of the atmospheric disturbance itself is directly proportional to the pressure variation between two surrounding areas.

3. Results

This section shows the results that allow us to answer the two research questions. The first one concerns the assessment of whether there are conditions for which river floods and sea storms are compounded. The second one concerns an evaluation of the main forcings and their relationship.

Regarding the assessment of whether there are conditions for which river floods and sea storms are compounded, the analysis showed that the total events analyzed were over 800, an average of 20 events per year, approximately two-thirds of which occurred on the Ionian coast. The overall percentage occurrence of compound events is very high, close to 90%. However, the Tyrrhenian coast has a percentage 20% lower than that of the Ionian coast (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of compound river floods and sea storm events.

Concerning the second research question, the high tide height is of the order of a few tens of cm, with values generally between 0.1 and 0.25 m. The highest values are observed in the Tyrrhenian Sea, especially in the central–northern part, while the lowest values are observed in the southern part of the Ionian Sea and the Strait of Messina. These results confirm that Calabria has a micro-tidal environment, so tidal effects on sea storms are negligible [55].

On the other hand, the storm surge due to the wind is generally a few cm, up to about 20 cm, while the storm surge due to the barometric effect is slightly higher than 40 cm and has been calculated considering that the minimum value of atmospheric pressure recorded during the atmospheric disturbance typical of the Mediterranean Sea is 970 mbar. These are also modest values, so their effect on sea storms is negligible.

As described above, the forcing river flow was not analyzed due to the scarcity of available measurements.

Therefore, as a representative river flood event forcing, rainfall intensity i was chosen, while, as a representative sea storm event forcing, maximum significant wave height Hsmax was chosen. These forcings were analyzed with atmospheric forcings, and four data matrices were obtained, two for each coastal area, as shown below. This analysis showed that rainfall intensity is most influenced by atmospheric pressure and humidity, while maximum significant wave height is most influenced by wind speed (Table 2).

Table 2.

Data matrix for rainfall intensity and maximum significant wave height of Ionian and Tyrrhenian coasts.

4. Discussion

The analysis described above highlights a strong correlation between river floods and sea storms, with a percentage higher than 85% throughout the entire Calabrian region, and with significantly different values between the two coasts. In fact, on the Ionian coast, the percentage increases to over 90%, while on the Tyrrhenian coast, it decreases to just over 70%.

The analysis carried out with the PCA/MVR techniques showed that the atmospheric forcing factors that have the greatest influence are atmospheric pressure and humidity for river flood events, represented by the rainfall intensity forcing, and wind speed for sea storm events, represented by the maximum significant wave height.

This highlights how the strong correlation between compound river floods and sea storms depends on the atmospheric disturbance that generates these events. The dependence of these compound events on atmospheric disturbance is also highlighted by inverting the order of analysis of the events. In fact, in the analysis described above, the river flood events were first identified, and, for each identified event, the presence or absence of a sea storm was verified on the same day as the river flood or in the days immediately preceding and following it. Instead, comparing the two databases described above, the number of sea storms is much greater than the number of river floods, so the relative compound percentage would be considerably lower.

This can be explained by analyzing the generation mechanisms of river floods and sea storms. River floods are almost always caused by atmospheric disturbances that cause heavy rainfall, except for exceptional events such as dams and embankment collapse or breaches. Sea storms, on the other hand, can be caused by atmospheric disturbances acting both in the area under examination and at considerable distances from it, where only the relative waves arrive, and by strong winds not associated with atmospheric disturbances but caused only by pressure gradients. Therefore, the generation process common to both river floods and sea storms is atmospheric disturbance. In the case of atmospheric disturbance, the two Calabrian coasts are characterized by different exposures, which explains the compound percentage difference observed between the two coasts.

Indeed, the interaction between orography and mesoscale circulation leads to a precipitation gradient between the Tyrrhenian and Ionian sides of Calabria. In general, orography plays a key role in the type of perturbations observed in Calabria, with enhanced rainfall in localized spots [72,73] and with forces of secondary cyclogenesis which persist over the Ionian side [74]. The Ionian coast has short and heavy precipitation and is influenced by African currents and mainly exposed to winds and atmospheric disturbances coming from the northeast, Grecale; east, Levante; southeast, Scirocco; south, Mezzogiorno; and southwest, Libeccio. On the other hand, the Tyrrhenian coast is subject to orographic precipitation due to the presence of numerous mountains very close to the sea [75] and is influenced by western air currents and thus mainly exposed to winds and atmospheric disturbances from the north, Tramontana; northwest, Mistral; west, Ponente; and southwest, Libeccio. Generally, the atmospheric disturbances affecting the Ionian coast are characterized by higher humidity, persistence, and extension than those affecting the Tyrrhenian coast. Furthermore, the greatest number of atmospheric disturbances affecting the Ionian coast is observed in the autumn months, especially between October and November, as shown by Caloiero et al. [62], and Aceto et al. [76], who analyzed the damaging hydrogeological events that occurred in Calabria in the last 100 years or so. This seasonal peculiarity is often generated by high thermal gradients between the still very warm surface of the Mediterranean Sea, which reaches its maximum value in July and August at 26 °C, remains around 22–23 °C until October, and then drops to 14 °C in winter, and cold fronts, and in many cases assumes the characteristics of a kind of hurricane, also called Medicane (Mediterranean hurricane) or tropical-like cyclones (TLCs), as seen in 2015 in Bruzzano on the southern Ionian coast [11]. On the Tyrrhenian coast, most of the events in which the compound events of river floods and sea storms were verified are related to events generated by atmospheric disturbances coming from the southwest, often followed by a cold front coming from the northwest. A similar situation is observed on the Ionian coast, where the few river flood events not followed by a compound sea storm are generally caused by perturbations from the northeast.

Another important result of this analysis is that the contemporaneity between river floods and sea storm events can occur if two conditions are satisfied. The first is that the atmospheric disturbance extension is such that it affects both the sea and the land. The second condition is that the river basins affected by the atmospheric disturbance are characterized by small areas. This condition is important because, if the disturbance affects only the sea or the land, it can generate, respectively, only sea storms or river floods, but not trigger compound events. Therefore, if the area of the river basins is high, e.g., in the order of thousands of square kilometers, it is unlikely that they could be subject to such extensive atmospheric disturbance as to satisfy the first condition. The Calabrian geomorphological, climatic, and hydrological peculiarities described above make it particularly suitable for satisfying both conditions.

Another very important issue of this analysis is that river mouths are highly critical points in the presence of river floods and compound sea storms due to the jacking effect. This effect can increase the effects of the river flood and sea storm events taken individually, e.g., making two ordinary single events into an exceptional compound event. All this is more evident in anthropized contexts in which, e.g., there are inhabited centers and road and railway infrastructures near the river mouths. An example of this occurred in 2015 in Bruzzano, in southern Ionian Calabria, due to a Medicane which generated a river flood and a compound sea storm. This event caused the collapse of the road and railway bridges near the river mouth, but the statistical analysis of the two events taken individually has highlighted that neither of them alone was an exceptional event. Indeed, the return period of this rainfall event is less than 30 years, while the return period of this sea storm is less than 10 years [11].

This research represents the first step of a more complex analysis. This step was useful to verify the existence of compound river floods and sea storms generated by atmospheric disturbances, together with the identification of the forcing factors that have the greatest influence, and the knowledge of the conditions that generated compound events. Furthermore, in this first phase, only flood events that caused damage to the territory and to structures and infrastructures were analyzed, without evaluating the quantitative aspects of these events that will be the subject of future in-depth studies. To overcome this limitation, future developments of the manuscript should include a quantitative analysis of rainfall and sea storm events, divided into classes of rainfall height and significant wave height, and an analysis of the influence of the river basin area on compound events.

5. Conclusions

Most previous research on compound river floods and sea storm events has focused on extreme events, so there is a lack of studies analyzing compound events generated by non-exceptional atmospheric disturbances.

Therefore, the main findings of this paper concern the verification, through a data-driven approach, of the existence of these compound events of river floods and sea storms generated by the same atmospheric disturbance, the geomorphological conditions under which they occur, and the main driving forces behind them. The paper also analyzes the effects of these compound events, especially at river mouths subject to the jacking effect caused not by high tide but by sea storm waves, which, especially in anthropized territories, are the areas most vulnerable to these events. These analyses were carried out in Calabria, a region of Southern Italy that represents an interesting case study for its geomorphological, climatic, and hydrological peculiarities and for the considerable anthropization of its coastal territories.

The main result is a strong correlation between compound river floods and sea storms that depend on the same atmospheric disturbance. The dependent variables are the rainfall intensity and the maximum significant wave height for river floods and sea storms, respectively. The forcing factors that have the greatest influence are atmospheric pressure and humidity for the rainfall intensity and wind speed for the maximum significant wave height. The percentage of compound events is higher than 85% in the whole Calabrian region. There are significantly different values between the two coasts, over 90% on the Ionian coast and over 70% on the Tyrrhenian coast.

Another important result is that compound events can occur if two conditions are satisfied. The first of them is that the atmospheric disturbance extension is such that it affects both the sea and the land. The second condition is that the river basins affected by the atmospheric disturbance are characterized by small areas.

Consequently, river mouths are highly critical points if river floods and compound sea storms occur, due to the jacking effect. This effect can increase the effects of the river flood and sea storm events taken individually, i.e., making two ordinary single events into an exceptional compound event. These areas are the most vulnerable to these events, especially in anthropized territories.

Finally, the aim of this analysis was only to confirm the hypothesis that river floods and sea storm events are compounded, and this is the first step in a more in-depth analysis that will also examine the quantitative aspects of these phenomena. This analysis is essential for the planning and management of coastal areas subject to compound events and for implementing effective mitigation measures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.C., G.B., O.P., F.M. and G.F.; methodology, C.C., F.M. and G.F.; software, C.C., F.M. and G.F.; validation, C.C., G.B., O.P., F.M. and G.F.; formal analysis, C.C., F.M. and G.F.; investigation, C.C., F.M. and G.F.; resources, C.C. and O.P.; data curation, C.C. and O.P.; writing—original draft preparation, C.C., G.B., O.P., F.M. and G.F.; writing—review and editing, F.M. and G.F.; visualization, C.C., F.M. and G.F.; supervision, G.B. and O.P.; project administration, G.B. and O.P.; funding acquisition, G.B. and O.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Merkens, J.-L.; Reimann, L.; Hinkel, J.; Vafeidis, A.T. Gridded population projections for the coastal zone under the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways. Glob. Planet. Change 2016, 145, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzzi, A.; Davolio, S.; Malguzzi, P.; Drofa, O.; Mastrangelo, D. Heavy rainfall episodes over Liguria in autumn 2011: Numerical forecasting experiments. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2014, 14, 1325–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, M.; Westra, S.; Phatak, A.; Lambert, M.; van den Hurk, B.; McInnes, K.; Risbey, J.; Schuster, S.; Jakob, D.; Stafford-Smith, M. A compound event framework for understanding extreme impacts. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2014, 5, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zscheischler, J.; Martius, O.; Westra, S.; Bevacqua, E.; Raymond, C.; Horton, R.M.; van den Hurk, B.; AghaKouchak, A.; Jézéquel, A.; Mahecha, M.D.; et al. A typology of compound weather and climate events. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-B.; Liu, W.-C. Modeling flood inundation induced by river flow and storm surges over a river basin. Water 2014, 6, 3182–3199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamouz, M.; Zahmatkesh, Z.; Goharian, E.; Nazif, S. Combined impact of inland and coastal floods: Mapping knowledge base for development of planning strategies. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2015, 141, 4014098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canale, C.; Barbaro, G.; Petrucci, O.; Fiamma, V.; Foti, G.; Barilla, G.C.; Puntorieri, P.; Minniti, F.; Bruzzaniti, L. Analysis of floods and storms: Concurrent conditions. Ital. J. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2020, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petroliagkis, T.I.; Voukouvalas, E.; Disperati, J.; Bildot, J. Joint Probabilities of Storm Surge, Significant Wave Height and River Discharge Components of Coastal Flooding Events; EUR 27824 EN; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Canale, C.; Barbaro, G.; Foti, G.; Petrucci, O.; Besio, G.; Barillà, G.C. Bruzzano river mouth damage due to meteorological events. Int. J. River Basin Manag. 2022, 20, 499–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, M.; Arabi, M.; Kao, S.; Obeysekera, J.; Sweet, W. Climate Change and Changes in Compound Coastal-Riverine Flooding Hazard Along the U.S. Coasts. Earth’s Futur. 2021, 9, e2021EF002055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhou, W.-H.; Shen, P. Flood risk assessment of loss of life for a coastal city under the compound effect of storm surge and rainfall. Urban Clim. 2023, 47, 101396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, J.; Jakeman, A.J.; Vaze, J.; Croke, B.F.; Dutta, D.; Kim, S. Flood inundation modelling: A review of methods, recent advances and uncertainty analysis. Environ. Model. Softw. 2017, 90, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Zhang, Y.J.; Yu, H.; Sun, W.; Moghimi, S.; Myers, E.; Nunez, K.; Zhang, R.; Wang, H.V.; Roland, A.; et al. Simulating storm surge and compound flooding events with a creek-to-ocean model: Importance of baroclinic effects. Ocean Model. 2020, 145, 101526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, T.; Jain, S.; Bender, J.; Meyers, S.D.; Luther, M.E. Increasing risk of compound flooding from storm surge and rainfall for major US cities. Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5, 1093–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Araya, F.W.; Santiago-Collazo, L.F.; Gonzalez-Lopez, J.; Maldonado-Maldonado, J. Dynamic modeling of surface runoff and storm surge during hurricane and tropical storm events. Hydrology 2018, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle-Levinson, A.; Olabarrieta, M.; Heilman, L. Compound flooding in Houston-Galveston Bay during Hurricane Harvey. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 747, 141272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Xu, H.; Wang, J. Assessing tropical cyclone compound flood risk using hydrodynamic modelling: A case study in Haikou City, China. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 22, 665–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Tian, Z.; Sun, L.; Ye, Q.; Ragno, E.; Bricker, J.; Tan, J.; Wang, J.; Ke, Q.; Wang, S.; et al. Compound flood impact of water level and rainfall during tropical cyclone period in a coastal city: The case of Shanghai. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 22, 2347–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bacco, M.; Contento, A.; Scorzini, A.R. Exploring the compound nature of coastal flooding by tropical cyclones: A machine learning framework. J. Hydrol. 2024, 645, 132262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Shi, L.; Liang, B.; Wu, G.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Y. Characterizing interactive compound flood drivers in the Pearl River Estuary: A case study of Typhoon Hato (2017). J. Hydrol. 2024, 645, 132270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Lai, C.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Chen, X. Future sea level rise exacerbates compound floods induced by rainstorm and storm tide during super typhoon events: A case study from Zhuhai, China. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 911, 168799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Shen, D.; Pietrafesa, L.; Gayes, P.; Bao, S. Quantify the Compound Effects caused by the interactions between inland river system and coastal processes in Hurricane Coastal Flooding through Controlled Hydrodynamic Modeling Experiments. Ocean Model. 2025, 194, 102506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, P.; Yuan, D.; Xiong, C. Copula-based joint probability analysis of compound floods from rainstorm and typhoon surge: A case study of Jiangsu Coastal Areas, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jane, R.; Cadavid, L.; Obeysekera, J.; Wahl, T. Multivariate statistical modelling of the drivers of compound flood events in south Florida. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2020, 20, 2681–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanim, A.H.; McKinnie, F.W.; Goharian, E. Coastal Compound Flood Simulation through Coupled Multidimensional Modeling Framework. J. Hydrol. 2024, 630, 130691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendry, A.; Haigh, I.D.; Nicholls, R.J.; Winter, H.; Neal, R.; Wahl, T.; Joly-Laugel, A.; Darby, S.E. Assessing the characteristics and drivers of compound flooding events around the UK coast. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2019, 23, 3117–3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellou, B.; Rahali, H. Assessment of the joint impact of extreme rainfall and storm surge on the risk of flooding in a coastal area. J. Hydrol. 2019, 569, 647–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Wahl, T.; Fang, J.; Sun, X.; Kong, F.; Liu, M. Compound flood potential from storm surge and heavy precipitation in coastal China: Dependence, drivers, and impacts. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 25, 4403–4416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leijnse, T.; van Ormondt, M.; Nederhoff, K.; van Dongeren, A. Modeling compound flooding in coastal systems using a computationally efficient reduced-physics solver: Including fluvial, pluvial, tidal, wind- and wave-driven processes. Coast. Eng. 2021, 163, 103796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Tang, L.; Yang, D.; Wu, H.; Liu, Z. Compounding Effects of Fluvial Flooding and Storm Tides on Coastal Flooding Risk in the Coastal-Estuarine Region of Southeastern China. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Du, H.; Huang, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, P. Modelling the compound floods upon combined rainfall and storm surge events in a low-lying coastal city. J. Hydrol. 2023, 627, 130476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Li, R.; Li, Z.; Li, X.; Lai, C. Compound effects in complex estuary-ocean interaction region under various combination patterns of storm surge and fluvial floods. Urban Clim. 2024, 58, 102186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; Xu, K.; Bin, L.; Wang, C.; Shen, R. Assessment of the jacking effect of high tide on compound flooding in a coastal city under sea level rise based on water tracer modeling. J. Hydrol. 2023, 627, 130474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Ma, C.; Lian, J.; Bin, L. Joint probability analysis of extreme precipitation and storm tide in a coastal city under changing environment. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e109341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansa, A.; Genoves, A.; Picornell, M.A.; Campins, J.; Riosalido, R.; Carretero, O. Western Mediterranean cyclones and heavy rain. Part II: Statistical approach. Meteorol. Appl. 2001, 8, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lionello, P.; Bhend, J.; Buzzi, A.; Della-Marta, P.M.; Krichak, S.O.; Jansà, A.; Maheras, P.; Sanna, A.; Trigo, I.F.; Trigo, R. Chapter 6 Cyclones in the Mediterranean region: Climatology and effects on the environment. In Developments in Earth and Environmental Sciences; Lionello, P., Malanotte-Rizzoli, P., Boscolo, R., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; Volume 4, pp. 325–372. [Google Scholar]

- Fiori, E.; Comellas, A.; Molini, L.; Rebora, N.; Siccardi, F.; Gochis, D.J.; Tanelli, S.; Parodi, A. Analysis and hindcast simulations of an extreme rainfall event in the Mediterranean area: The Genoa 2011 case. Atmos. Res. 2014, 138, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaleri, L.; Barbariol, F.; Bertotti, L.; Besio, G.; Ferrari, F. The 29 October 2018 storm in Northern Italy: Its multiple actions in the Ligurian Sea. Prog. Oceanogr. 2022, 201, 102715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grazzini, F.; Craig, G.C.; Keil, C.; Antolini, G.; Pavan, V. Extreme precipitation events over northern Italy. Part I: A systematic classification with machine-learning techniques. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2020, 146, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sioni, F.; Davolio, S.; Grazzini, F.; Giovannini, L. Revisiting the atmospheric dynamics of the two century floods over north-eastern Italy. Atmospheric Res. 2023, 286, 106662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducrocq, V.; Braud, I.; Davolio, S.; Ferretti, R.; Flamant, C.; Jansa, A.; Kalthoff, N.; Richard, E.; Taupier-Letage, I.; Ayral, P.-A.; et al. HyMeX-SOP1: The field campaign dedicated to heavy precipitation and flash flooding in the northwestern Mediterranean. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2014, 95, 1083–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llasat, M.C.; Marcos, R.; Turco, M.; Gilabert, J.; Llasat-Botija, M. Trends in flash flood events versus convective precipitation in the Mediterranean region: The case of Catalonia. J. Hydrol. 2016, 541, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Villanueva, V.; Borga, M.; Zoccatelli, D.; Marchi, L.; Gaume, E.; Ehret, U. Extreme flood response to short-duration convective rainfall in South-West Germany. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 16, 1543–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigo, I.F.; Bigg, G.R.; Davies, T.R. Climatology of cyclogenesis mechanisms in the Mediterranean. Mon. Weather Rev. 2002, 130, 549–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouroutzoglou, J.; Flocas, H.A.; Keay, K.; Simmonds, I.; Hatzaki, M. Climatological aspects of explosive cyclones in the Mediterranean. Int. J. Clim. 2011, 31, 1785–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malguzzi, P.; Grossi, G.; Buzzi, A.; Ranzi, R.; Buizza, R. The 1966 century flood in Italy: A meteorological and hydrological revisitation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2006, 111, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davolio, S.; Della Fera, S.; Laviola, S.; Miglietta, M.M.; Levizzani, V. Heavy precipitation over Italy from the Mediterranean storm Vaia in October 2018: Assessing the role of an atmospheric river. Mon. Weather Rev. 2020, 148, 3571–3588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papathoma-Köhle, M.; Zischg, A.; Fuchs, S.; Glade, T.; Keiler, M. Loss estimation for landslides in mountain areas—An integrated toolbox for vulnerability assessment and damage documentation. Environ. Model. Softw. 2015, 63, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeber, V.; Bricker, J.D. Destructive tsunami-like wave generated by surf beat over a coral reef during Typhoon Haiyan. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandaglio, G. Ricerche geologiche per la difesa del suolo e la pianificazione di bacino in provincia di Reggio Calabria. Artemis 2016, 416p. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari, E.; Caloiero, T.; Coscarelli, R. Influence of the North Atlantic Oscillation on winter rainfall in Calabria (southern Italy). Theor. Appl. Clim. 2013, 114, 479–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caloiero, T.; Buttafuoco, G.; Coscarelli, R.; Ferrari, E. Spatial and temporal characterization of climate at regional scale using homogenous monthly precipitation and air temperature data: An application in southern Italy (Calabria Region). Hydrol. Res. 2015, 46, 629–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caloiero, T.; Aristodemo, F.; Ferraro, D.A. Trend analysis of significant wave height and energy period in southern Italy. Theor. Appl. Clim. 2019, 138, 917–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foti, G.; Barbaro, G.; Besio, G.; Barillà, G.C.; Mancuso, P.; Puntorieri, P. Wave Climate along Calabrian Coasts. Climate 2022, 10, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sannino, G.; Carillo, A.; Pisacane, G.; Naranjo, C. On the relevance of tidal forcing in modelling the Mediterranean thermohaline circulation. Prog. Oceanogr. 2015, 134, 304–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabato, L.; Tropeano, M. Fiumara: A kind of high hazard river. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2004, 29, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorriso-Valvo, M.; Terranova, O. The Calabrian fiumara streams. Z. Für Geomorphol. 2006, 143, 109–125. [Google Scholar]

- Barragán, J.M.; De Andrés, M. Analysis and trends of the world’s coastal cities and agglomerations. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2015, 114, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, B.; Zullo, F.; Fiorini, L.; Marucci, A.; Ciabò, S. Land transformation of Italy due to half a century of urbanization. Land Use Policy 2017, 67, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorini, L.; Zullo, F.; Marucci, A.; Romano, B. Land take and landscape loss: Effect of uncontrolled urbanization in Southern Italy. J. Urban Manag. 2019, 8, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombino, G.; Barbaro, G.; D’AGostino, D.; Denisi, P.; Foti, G.; Zimbone, S.M. Relationships between torrent check dam systems and shoreline dynamics in semi-arid Mediterranean area: A sub-regional focus in Calabria, Italy. Geomorphology 2024, 458, 109259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caloiero, T.; Pasqua, A.A.; Petrucci, O. Damaging Hydrogeological Events: A procedure for the assessment of severity levels and an Application to Calabria (Southern Italy). Water 2014, 6, 3652–3670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrucci, O.; Versace, P. ASICal: A database of landslides and floods occurred in Calabria (Italy). In Proceedings of the 1st Italian-Russian Workshop New Trends in Hydrology, Rende, Italy, 24–26 September 2002; Pubblicazione CNR-GNDCI n. 2823. Gaudio, R., Ed.; Editoriale Bios: Cosenza, Italy, 2004; pp. 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, V.; Becker, N.; Markantonis, V.; Schwarze, R.; van den Bergh, J.C.J.M.; Bouwer, L.M.; Bubeck, P.; Ciavola, P.; Genovese, E.; Green, C.; et al. Review article: Assessing the costs of natural hazards—State of the art and knowledge gaps. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2013, 13, 1351–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrucci, O.; Pasqua, A.A. The study of past Damaging Hydrogeological Events for damage susceptibility zonation. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2008, 8, 881–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentaschi, L.; Besio, G.; Cassola, F.; Mazzino, A. Performance evaluation of Wavewatch III in the Mediterranean Sea. Ocean Model. 2015, 90, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istituto Idrografico della Marina. Tavole di Marea e Delle Correnti di Marea; Istituto Idrografico della Marina: Genoa, Italy, 2020; p. 144. ISBN 97888II3133. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Boccotti, P. Wave Mechanics and Wave Loads on Marine Structures; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, F.; Barbaro, G. Il Rischio Ondoso nei Mari Italiani; CNR-GNDCI num. 1965; Editoriale BIOS: Cosenza, Italy, 1999; pp. 1–136. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Bretschneider, C.L. Engineering Aspects of Hurricane Surge. In Estuary and Coastline Hydrodynamics; Ippen, A.T., Ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Joliffe, I.T. Principal Component Analysis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Federico, S.; Bellecci, C.; Colacino, M. Quantitative precipitation of the Soverato flood: The role of orography and surface fluxes. Nuovo C. 2003, 26, 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Federico, S.; Bellecci, C.; Colacino, M. Numerical simulation of Crotone flood: Storm evolution. Nuovo C. 2003, 26, 357–371. [Google Scholar]

- Federico, S.; Avolio, E.; Bellecci, C.; Lavagnini, A.; Walko, R.L. Predictability of intense rain storms in the Central Mediterraneanbasin: Sensitivity to upper-level forcing. Adv. Geosci. 2007, 12, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colacino, M.; Conte, M.; Piervitali, E. Elementi di Climatologia Della Calabria; IFA-CNR: Rome, Italy, 1997. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Aceto, L.; Caloiero, T.; Pasqua, A.; Petrucci, O. Analysis of damaging hydrogeological events in a Mediterranean region (Calabria). J. Hydrol. 2016, 541, 510–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.