A Spatially Explicit Physically Based Modeling Framework for BOD Dynamics in Urbanizing River Basins: A Case Study of the Chao Phraya River—Tha Chin River

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

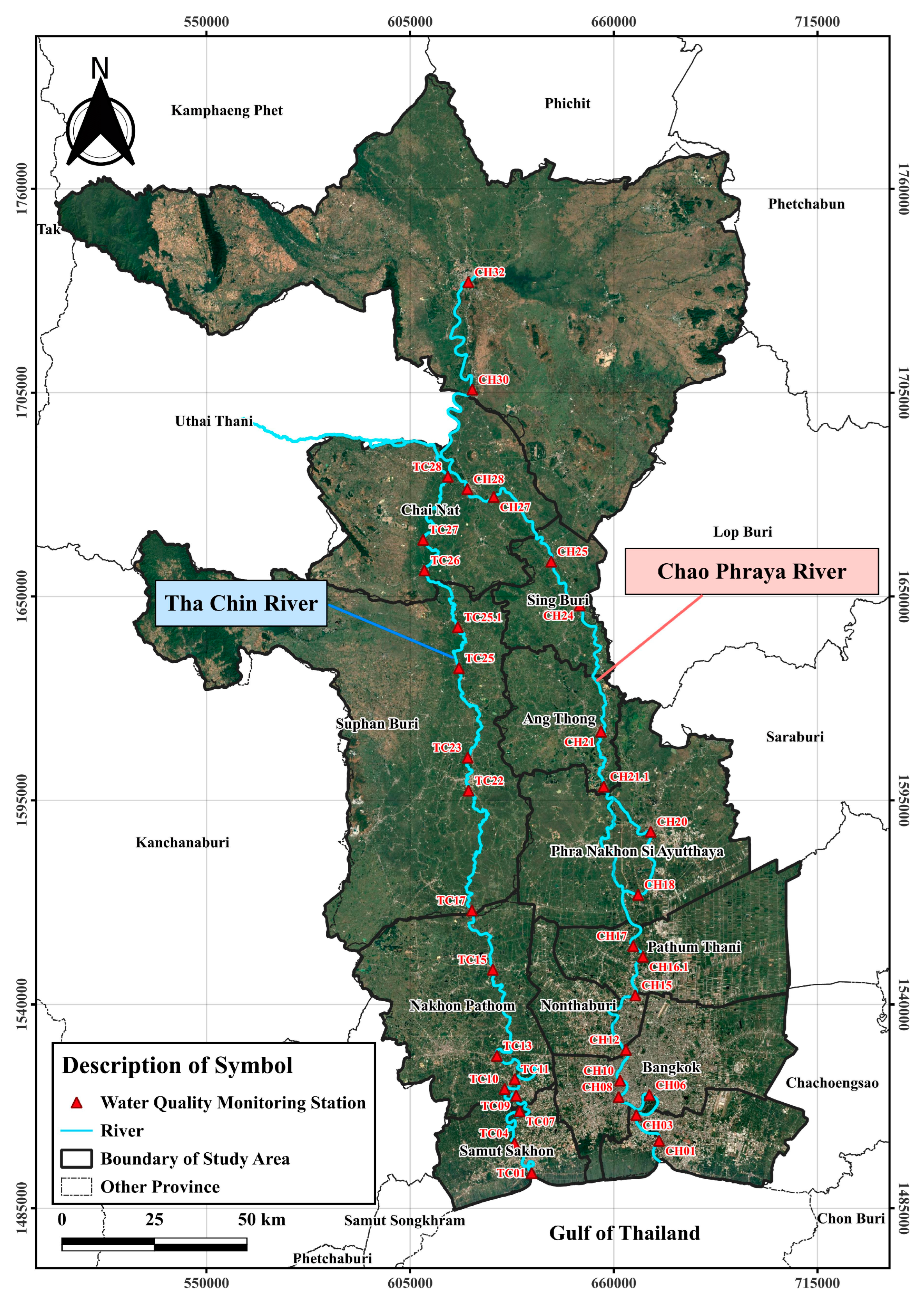

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Collection and Processing

- Domestic wastewater loads were estimated using district-level population data combined with per capita wastewater generation of approximately 200 L/person/day. Total wastewater volume for each district was then converted to pollutant loadings using standard BOD and nutrient generation factors, producing spatially aggregated domestic loads for model input [19].

- Industrial loads were derived from the Department of Industrial Works (DIW) factory registry, using reported discharge points, industry types, and wastewater characteristics. Sector-specific pollutant coefficients were applied to estimate loads, with adjustments based on compliance records where available. All discharge locations were spatially aligned with the river and canal network for model routing [58].

- Agricultural runoff was estimated based on production volumes from key agricultural sectors, including aquaculture, marine aquaculture, livestock (e.g., swine), and rice cultivation. Pollutant loads were calculated using sector-specific nutrient and organic matter generation factors, combined with information on feed usage and waste management practices. These loads were then spatially distributed across relevant agricultural zones and aggregated at the sub-catchment level for model input [19].

2.3. Model Description and Setup

2.3.1. Model Structure and Hydrologic Representation

- Explicit simulation of land use–specific rainfall–runoff generation, pollutant buildup, and wash-off processes was intentionally excluded to maintain a focus on basin-scale in-stream transport processes.

- The model objective is to evaluate relative management scenario performance driven by aggregated source loading and hydrodynamic behavior, rather than event-scale runoff dynamics.

- Incorporating detailed buildup and wash-off processes would require extensive site-specific monitoring and parameterization that are not currently available at the scale of the Chao Phraya–Tha Chin River system.

- Diffuse pollutant contributions are therefore implicitly represented through calibration against observed BOD concentrations, consistent with screening-level and TMDL-oriented modeling practice.

2.3.2. BOD Simulation and Pollutant Loading

- Non-point BOD loads were incorporated indirectly by calibrating initial estimates against observed monitoring data. When simulated BOD was consistently lower than observations, additional diffuse loads were added and distributed across sub-catchments until model outputs aligned with measured concentrations.

- In-stream BOD decay was represented using a first-order kinetic formulation, which assumes that the degradation rate is proportional to the existing organic concentration. This formulation is widely applied in riverine and urban water-quality models because of its computational efficiency and its ability to approximate microbial oxidation and biodegradation processes occurring during transport [71,72]. The governing equation is expressed as follows:

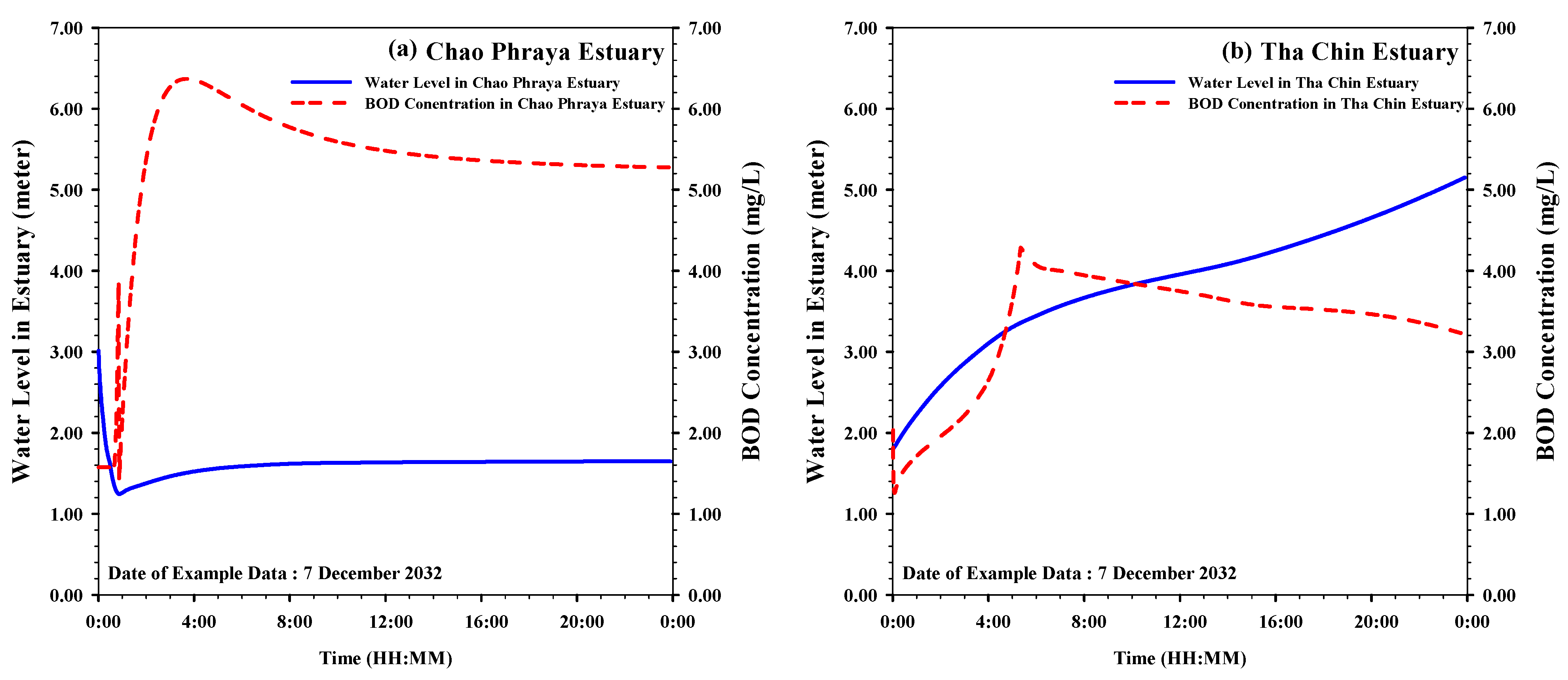

2.3.3. Estuarine Influence and Tidal Dynamics

2.4. Model Calibration and Validation

- Calibration phase: January 2022—December 2022;

- Validation phase: January 2021—December 2021.

2.5. Scenario Development and Analysis

Scenario Design

- Baseline Scenario: Assumes no additional interventions beyond existing policies, with projected demographic and wastewater growth.

- Moderate Reduction (MR-20%): Envisions modest improvements through expanded treatment coverage and partial implementation of pollution control measures.

- Enhanced Reduction (ER-30%): Represents comprehensive mitigation efforts, aligned with national water quality goals, involving full-scale infrastructure deployment and strict enforcement mechanisms.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Calibration and Validation Results

3.2. Scenario-Based BOD Simulation and Implications

3.3. Spatial and Temporal Patterns of BOD Concentration

3.4. Eutrophication Risk in the Upper Gulf of Thailand

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maúre, E.d.R.; Terauchi, G.; Ishizaka, J.; Clinton, N.; DeWitt, M. Globally consistent assessment of coastal eutrophication. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devlin, M.; Brodie, J. Nutrients and Eutrophication. In Marine Pollution–Monitoring, Management and Mitigation; Reichelt-Brushett, A., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 75–100. ISBN 978-3-031-10127-4. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, H.; Darby, S.E.; Zhao, N.; Liu, D.; Kettner, A.J.; Lu, X.; Yang, Y.; Gao, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.P. Anthropogenic eutrophication and stratification strength control hypoxia in the Yangtze Estuary. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damar, A.; Ervinia, A.; Kurniawan, F.; Rudianto, B.Y. Eutrophication in a tropical estuary: Is it good or bad? IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 744, 012010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh-Thu, P.; The, H.V.; Ben, H.X.; Hieu, N.M.; Phu, L.H.; Dung, L.T.; Ngoc, P.H.; Linh, V.T.T.; Mien, P.T.; Ha, T.T.; et al. Eutrophication Monitoring for Sustainable Development in Nha Trang Marine Protected Area, Vietnam. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.N.; Némery, J.; Gratiot, N.; Strady, E.; Tran, V.Q.; Nguyen, A.T.; Aimé, J.; Peyne, A. Nutrient dynamics and eutrophication assessment in the tropical river system of Saigon–Dongnai (southern Vietnam). Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 653, 370–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotto, L.P.A.; Beusen, A.H.W.; Villanoy, C.L.; Bouwman, L.F.; Jacinto, G.S. Nutrient load estimates for Manila Bay, Philippines using population data. Ocean Sci. J. 2015, 50, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotto, L.P.A.; Jacinto, G.S.; Villanoy, C.L. Spatiotemporal variability of hypoxia and eutrophication in Manila Bay, Philippines during the northeast and southwest monsoons. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 85, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerco, C.F.; Noel, M.R. Twenty-One-Year Simulation of Chesapeake Bay Water Quality Using the CE-QUAL-ICM Eutrophication Model. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2013, 49, 1119–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, G.; Nimmo-Smith, R.J.; Glegg, G.A.; Tappin, A.D.; Worsfold, P.J. Estuarine eutrophication in the UK: Current incidence and future trends. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2009, 19, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paerl, H.W.; Valdes, L.M.; Peierls, B.L.; Adolf, J.E.; Harding, L.W., Jr. Anthropogenic and climatic influences on the eutrophication of large estuarine ecosystems. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2006, 51, 448–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, D.; Xiao, W.; Zhou, P.; Tian, C.; Zhang, C.; Du, J.; Guo, H.; Wang, B. Coastal eutrophication in China: Trend, sources, and ecological effects. Harmful Algae 2021, 107, 102058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, Z.; Wang, G.; He, Y.; Mu, L.; Mao, X.; Bi, H.; Zhang, J. Delayed algal blooms to runoff surges in low-runoff estuaries: Hydrodynamic and nutrient driving mechanisms and early warning strategies. J. Hydrol. 2025, 662, 134057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buranapratheprat, A.; Morimoto, A.; Phromkot, P.; Mino, Y.; Gunbua, V.; Jintasaeranee, P. Eutrophication and hypoxia in the upper Gulf of Thailand. J. Oceanogr. 2021, 77, 831–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheevaporn, V.; Menasveta, P. Water pollution and habitat degradation in the Gulf of Thailand. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2003, 47, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srisunont, C.; Srisunont, T. Risk of red tide and eutrophication under climate change phenomena in Thailand. Int. Aquat. Res. 2025, 17, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuenyong, S.; Buranapratheprat, A.; Thaipichitburapa, P.; Gunbua, V.; Intacharoen, P.; Morimoto, A. Fluxes of Dissolved Nutrients and Total Suspended Solids from the Bang Pakong River Mouth into the Upper Gulf of Thailand. J. Fish. Environ. 2023, 47, 68–83. [Google Scholar]

- ONPE. Environmental Quality Management Plan 2023–2027 (Abridged Edition). Office of Natural Resources and Environmental Policy and Planning. 2024. Available online: https://www.onep.go.th/book/environmental-quality-management-plan-2023-2027-abridged-edition/ (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- PCD. Thailand Water Quality Annual Report 2022; Pollution Control Department: Bangkok, Thailand, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- RID. Hydrological Yearbook 2018–2022; Royal Irrigation Department: Bangkok, Thailand, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wattayakorn, G. Environmental Issues in the Gulf of Thailand. In The Environment in Asia Pacific Harbours; Wolanski, E., Ed.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 249–259. ISBN 978-1-4020-3655-2. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, W.-C.; Fu, T.-M. Turbulent transport and dry deposition of air pollutants over real urban surfaces: A building-resolving large-eddy simulation study. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 129, 106448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosse, P.; Lübken, M.; Wichern, M. Urban lignocellulosic biomass can significantly contribute to energy production in municipal wastewater treatment plants—A GIS-based approach for a metropolitan area. Biomass Bioenergy 2015, 81, 568–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.M.; Burkholder, J.M.; Cochlan, W.P.; Glibert, P.M.; Gobler, C.J.; Heil, C.A.; Kudela, R.; Parsons, M.L.; Rensel, J.E.J.; Townsend, D.W.; et al. Harmful algal blooms and eutrophication: Examining linkages from selected coastal regions of the United States. Harmful Algae 2008, 8, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvine, K.N.; Murphy, T.P. Assessment of eutrophication and phytoplankton community impairment in the Buffalo River Area of Concern. J. Great Lakes Res. 2009, 35, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, T.; Irvine, K.; Guo, J.; Davies, J.; Murkin, H.; Charlton, M.; Watson, S. New Microcystin Concerns in the Lower Great Lakes. Water Qual. Res. J. 2003, 38, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellner, K.G.; Doucette, G.J.; Kirkpatrick, G.J. Harmful algal blooms: Causes, impacts and detection. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2003, 30, 383–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Lee, S.; Yu, S.; Rhew, D. Relationships between water quality parameters in rivers and lakes: BOD5, COD, NBOPs, and TOC. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2016, 188, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustapha, A.; Aris, A.Z.; Juahir, H.; Ramli, M.F.; Kura, N.U. River water quality assessment using environmentric techniques: Case study of Jakara River Basin. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 5630–5644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cross, T.K.; Summerfelt, R.C. Bod Dynamics in Small Eutrophic Lakes in Relation to Artificial Mixing. Lake Reserv. Manag. 1986, 2, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallin, M.A.; Cahoon, L.B. The Hidden Impacts of Phosphorus Pollution to Streams and Rivers. BioScience 2020, 70, 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miltner, R.J. Eutrophication endpoints for large rivers in Ohio, USA. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2018, 190, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phu, S.T.P. Research on the Correlation Between Chlorophyll-a and Organic Matter BOD, COD, Phosphorus, and Total Nitrogen in Stagnant Lake Basins. In Sustainable Living with Environmental Risks; Kaneko, N., Yoshiura, S., Kobayashi, M., Eds.; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2014; pp. 177–191. ISBN 978-4-431-54804-1. [Google Scholar]

- Birkeland, S. An Agricultural Law Research Article: EPA’s TMDL Program. National Agricultural Law Center—The Nation’s Leading Source of Agricultural and Food Law Research and Information. 2001. Available online: https://nationalaglawcenter.org/ (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- USEPAO. Incorporating Green Infrastructure into TMDLs. 2008. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/tmdl/incorporating-green-infrastructure-tmdls (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Neilson, B.; Stevens, D. Issues Related to the Success of the TMDL Program. Water Resour. Update 2002, 122, 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- US EPA. Technical Guidance Manual for Developing Total Maximum Daily Loads; United States Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; Volume 2. Available online: https://19january2021snapshot.epa.gov/sites/static/files/2019-12/documents/technical-guidance-tmdl-book2.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Fan, C.; Chen, K.-H.; Huang, Y.-Z. Model-based carrying capacity investigation and its application to total maximum daily load (TMDL) establishment for river water quality management: A case study in Taiwan. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 291, 125251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, W.; Lott, R.C.; LaPlante, R.; Rose, F. Modeling for TMDL Implementation. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2019, 24, 05019010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawardana, C.; McDonald, W. The influence of socioeconomic and spatial variables on total maximum daily load progress in the United States. Water Policy 2023, 25, 1062–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.S.; Park, S.W.; Lee, J.J.; Yoo, K.H. Applying SWAT for TMDL programs to a small watershed containing rice paddy fields. Agric. Water Manag. 2006, 79, 72–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makanda, K.; Nzama, S.; Kanyerere, T. Assessing Feasibility of Water Resource Protection Practice at Catchment Level: A Case of the Blesbokspruit River Catchment, South Africa. Water 2023, 15, 2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, W.; Jiao, J.; Wang, M.; Zhang, M.; Li, Y.; Wu, J. TMDL for phosphorus and contributing factors in subtropical watersheds of southern China. Env. Monit. Assess. 2015, 187, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusof, F.M.; Jamil, N.R.; Sapia’e, S.; Ata, F.M.; Malik, N.K.A. Integration of Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) and Environmental Flow Assessment (EFA) Concepts as an Adaptive Approach to Pollutant Loading Management in Asia: A Review. Pertanika J. Sci. Technol. 2025, 33, 507–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrea, S.; Tudesque, L.; Chea, R. Comparative assessment of water quality classification techniques in the largest north-western river of Cambodia (Sangker River-Tonle Sap Basin). Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlaing, P.T.; Humphries, U.W.; Waqas, M. Hydrological model parameter regionalization: Runoff estimation using machine learning techniques in the Tha Chin River Basin, Thailand. MethodsX 2024, 13, 102792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laonamsai, J.; Julphunthong, P.; Chipthamlong, P.; Pawan, V.; Chomchaewchan, P.; Kamdee, K.; Tomun, N.; Kimmany, B. Hydrochemical Characteristics and Salt Intrusion in Groundwater of the Lower Chao Phraya River Basin: Insights from Stable Isotopes and Hydrochemical Analysis—ScienceDirect. 2023. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2352801X23001455 (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- Budhathoki, A.; Tanaka, T.; Tachikawa, Y. Assessing extreme flood inundation and demographic exposure in climate change using large ensemble climate simulation data in the Lower Chao Phraya River Basin of Thailand. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2023, 50, 101583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BMA. Wastewater management System Bangkok; Bangkok Metropolitan Administration: Bangkok, Thailand, 2025. Available online: http://wqmodatacenter.bangkok.go.th/ (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- Stuhldreier, I.; Bastian, P.; Schönig, E.; Wild, C. Effects of simulated eutrophication and overfishing on algae and invertebrate settlement in a coral reef of Koh Phangan, Gulf of Thailand. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 92, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matan, N.; Kongchoosi, N.; Sinthupachee, A.; Chaidech, P. Nutritional and bioactive compound analysis of mangosteen fruit in hill and flat land plantations, during both the season and off-season, in provinces along the Gulf of Thailand and the Andaman Sea. NFS J. 2024, 36, 100182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubkov, M.; Golubkov, S. The role of total phosphorus in eutrophication of freshwater and brackish-water parts of the Neva River estuary (Baltic Sea). Mar. Environ. Res. 2025, 209, 107232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratum, C.; Arunrat, N.; Sereenonchai, S.; Huang, J.C.; Xu, T. Water quality situation of the Tha Chin river and the riverbank community’s understanding. Nat. Environ. Pollut. Technol. 2019, 18, 1045–1051. [Google Scholar]

- Singkran, N.; Anantawong, P.; Intharawichian, N.; Kunta, K. The Chao Phraya River Basin: Water quality and anthropogenic influences. Water Supply 2018, 19, 1287–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongsupap, C.; Weesakul, S.; Clemente, R.; Das Gupta, A. River basin water quality assessment and management: Case study of Tha Chin River Basin, Thailand. Water Int. 2009, 34, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HII. Hydro Informatics in Chao Phraya and Tha Chin River; Hydro-Informatics Institute: Bangkok, Thailand, 2025; Available online: https://www.hii.or.th/en/home/ (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- LDD. Land Use Change and Application Dyna-CLUE Model Predicts Land Use Change in the Chao Phraya River Tributary Basin; Land Development Department: Bangkok, Thailand, 2025. Available online: https://lddnews.ldd.go.th/page_iframe (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- DIW. Wastewater Volume Data from Industrial Plants in Thailand Report; Department of Industrial Works: Bangkok, Thailand, 2022. Available online: https://www.diw.go.th/webdiw/home (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- Borah, D.K.; Ahmadisharaf, E.; Padmanabhan, G.; Imen, S.; Mohamoud, Y.M. Watershed Models for Development and Implementation of Total Maximum Daily Loads. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2019, 24, 03118001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitwatkulsiri, D.; Miyamoto, H.; Irvine, K.N.; Pilailar, S.; Loc, H.H. Development and Application of a Real-Time Flood Forecasting System (RTFlood System) in a Tropical Urban Area: A Case Study of Ramkhamhaeng Polder, Bangkok, Thailand. Water 2022, 14, 1641. [Google Scholar]

- Chitwatkulsiri, D.; Irvine, K.N.; Chua, L.H.C.; Teang, L.; Charoenpanuchart, R.; Likitswat, F.; Sahavacharin, A. Assessing Urban Resilience Through Physically Based Hydrodynamic Modeling Under Future Development and Climate Scenarios: A Case Study of Northern Rangsit Area, Thailand. Climate 2025, 13, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvine, K.; Sovann, C.; Suthipong, S.; Kok, S.; Chea, E. Application of PCSWMM to Assess Wastewater Treatment and Urban Flooding Scenarios in Phnom Penh, Cambodia: A Tool to Support Eco-City Planning. JWMM 2015, 23, 1–13. Available online: https://www.chijournal.org/C389 (accessed on 3 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Irvine, K.; Chua, L.; Ashrafi, M.; Loc, H.H.; Le, S.H. Drivers of Model Uncertainty for Urban Runoff in a Tropical Climate: The Effect of Rainfall Variability and Subcatchment Parameterization. 2023. Available online: https://www.chijournal.org/C496 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Teang, L.; Irvine, K.N.; Chua, L.H.C.; Usman, M. Dynamics of Runoff Quantity in an Urbanizing Catchment: Implications for Runoff Management Using Nature-Based Retention Wetland. Hydrology 2025, 12, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yu, C.; Xu, Z. Impacts of watershed nutrient loads on eutrophication risks under multiple socio-economic development scenarios in the Pearl River Estuary, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 496, 145133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashel, F.S.; Knightes, C.D.; Lupo, C.; Iott, T.; Streich, K.; Conville, C.J.; Bridges, T.W.; Dombroski, I. Using monitoring and mechanistic modeling to improve understanding of eutrophication in a shallow New England estuary. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 355, 120478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, G.; Sitzenfrei, R.; Kleidorfer, M.; Rauch, W. Parallel flow routing in SWMM 5. Environ. Model. Softw. 2014, 53, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmasena, T.; Chua, L.H.C.; Barron, N.; Zhang, H. Performance assessment of a constructed wetland using a numerical modelling approach. Ecol. Eng. 2021, 173, 106441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A.R. Storm Water Management Model User’s Manual Version 5.0; United States Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2019-02/documents/epaswmm5_1_manual_master_8-2-15.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Ansari, M.S.; Sharma, S.; Armstrong, F.P.; Delisio, M.; Ehsani, S. Exploring PCSWMM for Large Mixed Land Use Watershed by Establishing Monitoring Sites to Evaluate Stream Water Quality. Hydrology 2024, 11, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomann, R.V. Principles of Surface Water Quality Modeling and Control; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1987; Available online: http://archive.org/details/principlesofsurf0000thom (accessed on 12 December 2025)ISBN 978-0-06-046677-0.

- Bowie, G.L.; Mills, W.B.; Porcella, D.B.; Campbell, C.L.; Pagenkopf, J.R.; Rupp, G.L.; Johnson, K.M.; Chan, P.W.H.; Gherini, S.A. Rates, Constants, and Kinetics Formulations in Surface Water Quality Modeling, 2nd ed.; Environmental Research Laboratory, Office of Research and Development, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Athens, GA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Tuomela, C.; Sillanpää, N.; Koivusalo, H. Assessment of stormwater pollutant loads and source area contributions with storm water management model (SWMM). J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 233, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuruzzaman, M.; Al-Mamun, A.; Salleh, M.N.B. Experimenting biochemical oxygen demand decay rates of Malaysian river water in a laboratory flume. Environ. Eng. Res. 2018, 23, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lung, W.-S. Progression of river BOD/DO modeling for water quality management. Water Environ. Res. 2023, 95, e10864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zou, Z. Sensitivity Analysis of Parameters in Water Quality Models and Water Environment Management. J. Environ. Prot. 2012, 3, 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.S.; Reyes, N.J.; Jeon, M.; Kim, L.H. Characterization of pollutants and identification of microbial communities in the filter media of green infrastructures. Ecol. Eng. 2023, 193, 107012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaf, M.N.; Manenti, S.; Creaco, E.; Giudicianni, C.; Tamellini, L.; Todeschini, S. New optimization strategies for SWMM modeling of stormwater quality applications in urban area. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 361, 121244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamprom, W.; Jotaworn, S.; Iamsomboon, N.; Hussadin, A.; Siramaneerat, I.; Pongput, N. Circular economy and community participation in Chao Phraya river Conservation: Evidence from Thai urban riverside communities. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2025, 18, 100299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TMD. Provincial Climate Report 2022; Thai meteorological Department: Bangkok, Thailand, 2022. Available online: https://www.tmd.go.th/service/downloadableDocuments (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- Cheng, S.; Lin, Z.; Sun, Y.; Li, H.; Ren, X. Fast and simultaneous detection of dissolved BOD and nitrite in wastewater by using bioelectrode with bidirectional extracellular electron transport. Water Res. 2022, 213, 118186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debela, H.E.; Bidira, F.; Asaithambi, P. Removal of BOD, TDS, and phosphate from industrial parks wastewater by using a combined sono-pulsed electrocoagulation method. Sci. Afr. 2025, 28, e02741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaidis, N.P.; Poikane, S.; Bouraoui, F.; Salas-Herrero, F.; Free, G.; Varkitzi, I.; van de Bund, W.; Kelly, M.G. Comparison of eutrophication assessment for the Nitrates and water Framework Directives: Impacts and opportunities for streamlined approaches. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 177, 113375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DMCR. National Quality Status in Thailand-2021; Department of Marine and Coastal Resources: Bangkok, Thailand, 2021. Available online: https://warning.dmcr.go.th/th/knowledge?page=2 (accessed on 21 June 2025).

| Land Use Type | Decay Coefficient |

|---|---|

| Residential | 0.18 day−1 |

| Industrial | 0.22 day−1 |

| Agriculture | 0.12 day−1 |

| Scenario | Key Assumptions | Actions/Interventions | Reference Guidelines |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Baseline | - No changes in land use or wastewater treatment practices | - Status quo maintained | [19,58] |

| - Population growth at 1.2% annually | - Existing infrastructure only | ||

| - No new industrial treatment plants | |||

| 2. Moderate Reduction (MR-20%) | - 20% BOD load reduction | - Decentralized wastewater systems in peri-urban areas | [19] |

| - Targeting all major sources: domestic, industrial, agricultural | - Enforcement of effluent standards | ||

| 3. Enhanced Reduction (ER-30%) | - 30% BOD load reduction | - Expansion of centralized wastewater treatment (38% → 60%) | [19,77] |

| - In line with National Strategy targets | - Green infrastructure (wetlands, bioswales) promotion |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chitwatkulsiri, D.; Charoenpanuchart, R.; Irvine, K.N.; Theepharaksapan, S. A Spatially Explicit Physically Based Modeling Framework for BOD Dynamics in Urbanizing River Basins: A Case Study of the Chao Phraya River—Tha Chin River. Water 2026, 18, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010015

Chitwatkulsiri D, Charoenpanuchart R, Irvine KN, Theepharaksapan S. A Spatially Explicit Physically Based Modeling Framework for BOD Dynamics in Urbanizing River Basins: A Case Study of the Chao Phraya River—Tha Chin River. Water. 2026; 18(1):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010015

Chicago/Turabian StyleChitwatkulsiri, Detchphol, Ratchaphon Charoenpanuchart, Kim Neil Irvine, and Suthida Theepharaksapan. 2026. "A Spatially Explicit Physically Based Modeling Framework for BOD Dynamics in Urbanizing River Basins: A Case Study of the Chao Phraya River—Tha Chin River" Water 18, no. 1: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010015

APA StyleChitwatkulsiri, D., Charoenpanuchart, R., Irvine, K. N., & Theepharaksapan, S. (2026). A Spatially Explicit Physically Based Modeling Framework for BOD Dynamics in Urbanizing River Basins: A Case Study of the Chao Phraya River—Tha Chin River. Water, 18(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010015