Abstract

Understanding the spatiotemporal evolution of soil salinization is essential for elucidating its driving mechanisms and supporting sustainable land and water management in arid regions. In this study, the Alar Reclamation Area in Xinjiang, a typical desert–oasis transition zone, was selected to investigate the drivers of spatiotemporal variation in soil salinization. GRACE gravity satellite observations for the period 2002–2022 were used to estimate groundwater storage (GWS) fluctuations. Contemporaneous Landsat multispectral imagery was employed to derive the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) and a salinity index (SI), which were further integrated to construct the salinization detection index (SDI). Pearson correlation analysis, variance inflation factor analysis, and a stepwise regression framework were employed to identify the dominant factors controlling the occurrence and evolution of soil salinization. The results showed that severe salinization was concentrated along the Tarim River and in low-lying downstream zones, while salinity levels in the middle and upper parts of the reclamation area had generally declined or shifted to non-salinized conditions. SDI exhibited a strong negative correlation with NDVI (p ≤ 0.01) and a significant positive correlation with both irrigation quota and GWS (p ≤ 0.01). A pronounced collinearity was observed between GWS and irrigation quota. NDVI and GWS were identified as the principal drivers governing spatial–temporal variations in SDI. The resulting regression model (SDI = 0.946 − 0.959 × NDVI + 0.318 × GWS) established a robust quantitative relationship between SDI, NDVI and GWS, characterized by a high coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.998). These statistics indicated the absence of multicollinearity (variance inflation factor, VIF < 5) and autocorrelation (Durbin–Watson ≈ 1.876). These findings provide a theoretical basis for the management of saline–alkali lands in the upper Tarim River region and offer scientific support for regional ecological sustainability.

1. Introduction

Soil salinization is one of the major land degradation processes threatening global agricultural sustainability and ecological security [1]. In arid and semi-arid regions, intense evaporation and limited precipitation create favorable conditions for salt accumulation in surface soils [2]. Inappropriate human activities, such as irrigation with highly mineralized water, further exacerbate this process, resulting in declines in cropland quality, loss of biodiversity, and degradation of ecosystem services [3]. In northwestern China, arid inland basins have become typical and severely affected regions of soil salinization [4]. The Tarim River Basin, located along the southern foothills of the Tianshan Mountains, represents one of the most prominent examples, owing to its unique natural conditions and long-term oasis agricultural development [5]. Therefore, accurate monitoring and assessment of the spatiotemporal dynamics of soil salinization in this region are essential for sustainable land use. Elucidating the underlying driving mechanisms is also critical for maintaining regional ecological security.

In recent years, rapid advances in remote sensing technologies have enabled the use of multi-source datasets for large-scale and high-frequency monitoring of soil salinization [6,7]. Considerable progress has been achieved through the development of spectral indices, such as the salinity index (SI) and the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) [8,9]. At the same time, machine learning algorithms, including random forests and support vector machines, have been widely applied to directly or indirectly estimate soil salinity [10,11]. In typical oasis regions, such as the Alar Reclamation Area in the Tarim River Basin, these methods have been widely applied to map the spatial distribution of soil salinity and to preliminarily investigate its spatiotemporal dynamics [12]. Digital Soil Mapping (DSM) is widely recognized as an effective methodology for soil spatial prediction, as it emphasizes the role of multi-source environmental covariates in explaining and predicting the spatial variability of soil properties [13,14]. In studies of soil salinization, DSM has contributed to a transition from traditional qualitative descriptions toward quantitative spatial prediction [15]. A wide range of environmental covariates has been adopted, including topographic indices derived from digital elevation models (DEMs), optical and radar-based spectral indices (e.g., NDVI, SI, and SAR backscatter coefficients), and climate reanalysis data [16]. These variables are commonly integrated into modeling frameworks, such as geographically weighted regression and random forest models, to generate regional-scale maps of soil salinity [15]. However, most DSM-based studies on soil salinization still focus on static patterns or long-term trends, with the primary aim of improving the spatial prediction accuracy of soil salinity [17]. While these studies can identify factors associated with salinity distribution, including higher salinity in low-lying areas and regions with sparse vegetation cover, they provide limited insight into temporal processes and interactions among these factors [17]. One important reason for this limitation lies in the choice of driving variables. Many existing models rely heavily on surface spectral indicators that respond indirectly to salinization processes or exhibit a delayed response [9]. For example, NDVI mainly reflects vegetation condition and stress, rather than the physical processes governing water and salt movement in soils [18]. By contrast, key variables that directly influence water–salt transport, such as regional groundwater dynamics, are often unavailable at appropriate spatial and temporal scales owing to sparse ground-based monitoring networks [19,20]. As a result, these critical drivers are frequently excluded from DSM-based analyses [16]. Consequently, despite the large number of soil salinization mapping studies conducted in the Alar Reclamation Area, relatively few have addressed practical questions, such as the extent to which groundwater decline contributes to salinization mitigation or how vegetation restoration and water-saving irrigation practices jointly influence salinity patterns. At present, the role of groundwater storage in shaping soil salinization patterns remains insufficiently quantified.

Traditionally, the influence of groundwater has been characterized mainly through spatial interpolation of data from limited monitoring wells [21]. At the regional scale, such data often provide inadequate spatial and temporal resolution and insufficient accuracy. The Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) mission and its follow-on mission (GRACE-FO) monitor variations in the Earth’s gravity field and offer an effective means of obtaining large-scale and temporally continuous groundwater storage (GWS) data [22]. In recent years, GRACE-derived datasets have been widely used to assess global and regional groundwater change trends. These datasets have also been linked to drought conditions and land-use practices [23]. However, the systematic integration of long-term GWS variations derived from GRACE as key environmental covariates in analyses of soil salinization drivers remains at an early stage. Only a limited number of recent studies have begun to explore this relationship. For example, some studies have examined the temporal correlations between GWS and remotely sensed salinity indices to evaluate the potential role of groundwater depletion in alleviating soil salinization [24].

Overall, recent research has moved beyond qualitative analysis toward quantifying key drivers and clarifying how soil salinity responds across different ranges of influencing factors. For typical arid oasis systems such as the Alar Reclamation Area, research is shifting from pattern-oriented qualitative analysis toward analyses that explicitly consider driving processes [25]. This shift faces several practical challenges, including the quantification of driving variables, the representation of complex relationships, and the integration of multi-source datasets [2]. From a practical perspective, qualitative analysis alone is often insufficient to support targeted salinity management [1]. There is therefore a need for an analytical framework that integrates multi-source remote sensing information with relevant environmental covariates and applies appropriate modeling approaches to interpret the spatiotemporal evolution of soil salinization and its primary controls.

In this context, this study is conducted in the Alar Reclamation Area of the Tarim River Basin in Xinjiang. Multi-source datasets are integrated to quantitatively identify the key drivers of soil salinization and to assess their contributions to salinization processes at the regional scale. The findings are intended to support the management of saline–alkali lands and the optimization of water resource allocation. They also provide scientific support for maintaining ecological sustainability in arid oasis regions. This study aims to: (1) characterize the spatiotemporal patterns and evolution of soil salinization and its associated driving factors in the Alar Reclamation Area; (2) identify the dominant drivers controlling the spatiotemporal differentiation of soil salinization in the region; (3) quantify the responses of soil salinization to key influencing factors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

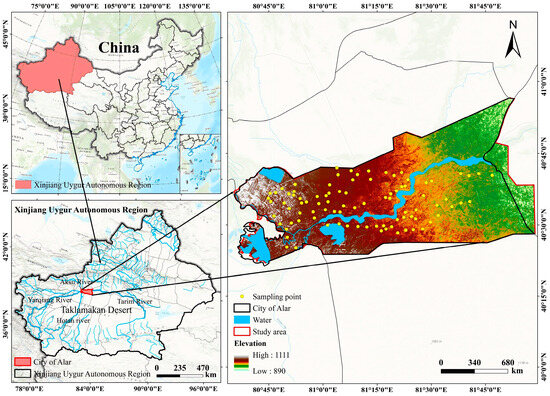

The Alar Reclamation Area (80°30′–81°58′ E, 40°22′–40°57′ N) is located in southern Xinjiang, China, on the southern flank of the Tianshan Mountains and along the northern margin of the Taklimakan Desert [26]. The region is situated on the fine alluvial plain of the Tarim River, the longest inland river in China. This geographical setting, together with long-term agricultural development, has shaped the area into a typical desert–oasis ecotone and one of China’s major regions of large-scale oasis agriculture [5]. The reclamation area has a total population of approximately 521,000 and covers an area of 4197.58 km2.

The terrain slopes from northwest to southeast (Figure 1). The Tarim River flows across the region from west to east, with three major upstream reservoirs (Shengli, Shangyou, and Duolang) located along its course. The climate is classified as warm temperate and arid desert nature. The region experiences large temperature fluctuations, very low precipitation, abundant sunshine, and intense evapotranspiration, resulting in high ecological vulnerability. The long-term mean annual precipitation ranges from 40.1 to 82.5 mm, while the mean annual temperature is 10–12 °C and mean annual evaporation ranges from 1876.6 to 2558.9 mm [27].

Figure 1.

Study area location and sampling sites.

Groundwater flow in the Alar Reclamation Area is consistent with the direction of surface water, moving from west to east. The Tarim River has formed an unconfined aquifer through alluvial deposition, with groundwater depths generally ranging from 2 to 5 m [28]. The soil texture is predominantly silty loam, characterized by strong capillary rise. Combined with the shallow groundwater table and relatively high mineralization, the region experiences severe soil salinization [29]. The local economy relies primarily on agricultural production, with major crops including cotton, wheat, jujube, and walnut. The area is also an important national production base for cotton.

2.2. Data Sources and Preprocessing

2.2.1. Soil Salinity and Irrigation Water Use

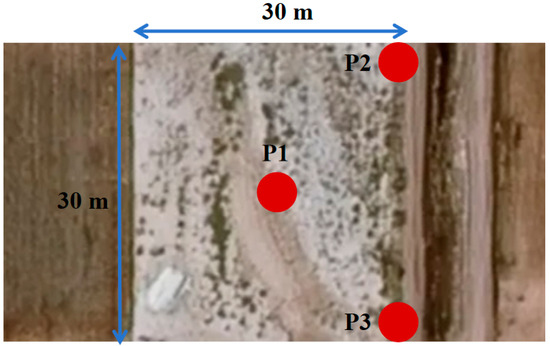

Surface soil samples (0–10 cm) were collected during the period from 5 April to 15 April 2024. A 10 km × 10 km grid sampling strategy was employed across the Alar Reclamation Area to ensure an approximately uniform spatial distribution of sampling locations. A total of 97 sampling sites were established. To ensure accuracy, repeatability, and reliability of the measurements, three parallel samples were collected at each site, yielding 291 soil samples in total. The three soil samples were systematically collected within a 30 m × 30 m area, and their mean value was used to represent the soil salinity at the corresponding pixel location. A schematic diagram of sampling design is shown in Figure 2. Parallel sampling strictly followed identical location, depth, and sampling procedures. Global Positioning System (GPS) coordinates were recorded for each sampling point. After collection with a soil auger, samples were placed in aluminum containers and transported to the laboratory. They were oven-dried at 105 °C for 8 h, after which plant roots, gravel, and other debris were removed, and the samples were passed through a 2 mm sieve. A soil–water suspension was prepared at a mass ratio of 5:1, thoroughly mixed, and allowed to settle for 5–6 h. The electrical conductivity of the supernatant extract was determined using a conductivity meter following filtration with qualitative filter paper.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the soil sampling layout within a single pixel. Soil samples were collected at three points (P1, P2, P3) within a 30 m × 30 m area corresponding to a single Landsat pixel. The mean value of the three samples was used to represent the soil salinity at that pixel location.

Historical data on the irrigation quota per mu was obtained from the Statistical Yearbook of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps for the Alar Reclamation Area. Monthly precipitation and potential evapotranspiration (PET) data were acquired from the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center of China (https://www.tpdc.ac.cn/home (accessed on 15 March 2024)) at a spatial resolution of 1 km. All historical datasets covered the period from 2002 to 2022.

2.2.2. Landsat ETM+/OLI Imagery and Soil Salinization Detection Indices

The Landsat series satellites, launched by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), rely on accurate ground control points and high-precision Digital Elevation Model (DEM) data for geometric correction [30]. They provide seasonally continuous global land coverage and observation, and acquire data across the visible, near-infrared, shortwave infrared, and panchromatic bands [31]. To characterize spectral responses sensitive to soil salinity and vegetation cover in arid regions, the blue and red bands were selected for index calculations based on surface reflectance [32,33,34]. Reflectance values typically range from 0 to 1 and describe the proportion of incident radiation reflected by a surface at different wavelengths.

Landsat ETM+/OLI imagery with cloud cover less than 10% and a spatial resolution of 30 m was selected, with acquisition dates in April. Satellite images were clipped to the boundary of the Alar Reclamation Area and subsequently normalized to eliminate dimensional differences among indices. The imagery was obtained from the Geospatial Data Cloud (http://www.gscloud.cn (accessed on 7 April 2024)). Data for the period 2002–2013 were extracted from the Landsat 7 ETM + C2 L2 dataset, while data for 2014–2022 and 2024 were extracted from the Landsat 8–9 OLI/TIRS C2 L2 dataset. All images corresponded to Path 147, Row 32. The data sources are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Temporal matching scheme of satellite imagery and field data.

- (1)

- Salinity Index (SI)

Soil salinization increases soil particle size and surface roughness, resulting in stronger reflectance in the blue and red spectral bands [33]. Based on the spectral response characteristics of saline soils, the SI was calculated using the blue and red bands. This index enhances the spectral contrast between saline and non-saline soils, with higher SI values indicating a greater potential risk of soil salinity [35]. The SI was computed as follows:

- (2)

- Normalized Different Vegetation Index (NDVI)

Soil salinization markedly suppresses vegetation growth, and vegetation cover can therefore serve as an indicator of soil salinization severity [36]. The NDVI calculated from the red and blue spectral bands was used as an indirect metric to quantify vegetation cover and reflect the degree of soil salinization [37]. The NDVI values typically range from −1 to 1, with negative values generally corresponding to unvegetated surfaces, while positive values increase with higher vegetation cover [38]. The NDVI was calculated according to the following equation:

- (3)

- Salinization Detection Index (SDI)

The SDI was constructed using the SI and the NDVI derived from Landsat 8–9 OLI/TIRS imagery acquired in April 2024. SDI was used to characterize the spectral contrast between salinized and non-salinized areas within the Alar Reclamation Area [32,39]. Higher SDI values indicate more severe soil salinization. The SDI could be constructed using the following equation:

This study evaluated the SDI model with electrical conductivity data from 97 field samples in April 2024. Soil salinization was delineated into five classes per the criteria in Table 2. To map the spatial distribution, the annual SDI layers from 2002 to 2022 were categorized according to these classes and overlaid onto the Alar Reclamation Area’s administrative boundary.

Table 2.

Classification of soil salinization grade.

- (4)

- Elevation Data

Elevation data for the Alar Reclamation Area were obtained from stereo imagery acquired by the Landsat 8/9 OLI sensors (Path 80 and 81, Row 40) to characterize the topographic variation in the region. Topographic variation within each sampling grid (10 km × 10 km) was represented by mean elevation, which was derived from the digital elevation model (DEM) using zonal statistics in ArcGIS 10.8. Mean elevation was then included as a candidate driving variable in the correlation and regression analyses to assess its association with soil salinity distribution.

2.2.3. Gravity Satellite Data and Groundwater Storage

As a joint endeavor between NASA and the German Aerospace Center (DLR), the GRACE mission maps temporal variations in Earth’s gravity field with unprecedented precision, utilizing a unique twin-satellite configuration [22]. Monthly terrestrial water storage (TWS), soil water storage (mm), and snow water equivalent (mm) can be retrieved from changes in the Earth’s gravity field. The GRACE gravity satellite data were obtained from the reanalyzed products released by the CSR laboratory, specifically the GLDAS Noah Land Surface Model L4 Monthly 0.25° × 0.25° V2.1 dataset (https://www2.csr.utexas.edu/grace/ (accessed on 25 March 2024)).

TWS denotes the total amount of water stored in terrestrial environments. It integrates various components, namely surface water, soil moisture, groundwater, and canopy water [40]. The Alar Reclamation Area is arid with minimal precipitation, limited surface water resources, and relatively small interannual variability in surface runoff, while canopy water is negligible [27]. Therefore, the groundwater storage (GWS) could be consequently estimated using a simplified water balance equation.

where TWSi is terrestrial water storage, mm; SMSi is soil moisture storage, mm; SWEi represents snow water equivalent, mm.

Groundwater storage anomalies (GWSA) indicate variations in groundwater reserves [40].

where GWSAi is groundwater reserve anomaly in year i (mm); GWSi and GWSi−1 are groundwater reserves in years i and i − 1, respectively (mm).

2.3. Selection of Driving Factors for Soil Salinization

Climate is a major factor influencing the vertical movement of soil salts [41]. In arid and semi-arid reclamation areas, evapotranspiration is intense, evaporation greatly exceeds precipitation, and in addition, leaching is weak, all of which contribute to the development of soil salinization [42]. Salts in shallow groundwater constitute the primary source of soil salinity in these regions. When the groundwater table is shallow, frequent exchanges of water and solutes occur between soil moisture and groundwater, and the upward capillary rise in groundwater to the soil surface is enhanced, leading to strong phreatic evaporation [2,43]. Topography also exerts substantial control on soil salt dynamics. In the downstream parts of the reclamation area, the flat terrain slows subsurface flow and restricts groundwater discharge, thereby increasing the likelihood of salinization [44]. In addition, anthropogenic activities, particularly irrigation, are key contributors to secondary salinization. High-salinity irrigation water and poor drainage in low-lying areas raise groundwater levels, further elevating salinization risk. Vegetation plays an important role in improving saline-alkali soils by reducing soil salt content through ion regulation and transpiration, weakening capillary water–salt transport, and soil water-holding and nutrient-holding capacity [45]. Accordingly, six driving factors affecting the spatiotemporal evolution of soil salinization were selected from four dimensions—topography, vegetation, climate, and human disturbance: surface elevation, potential evapotranspiration, precipitation, groundwater storage, irrigation quota per mu, and vegetation cover. Using the long-term dataset from 2002 to 2022, the correlations between these factors and the evolution of soil salinization were analyzed.

2.4. Data Analysis

- (1)

- Correlation Analysis

Pearson correlation analysis was used to quantify linear relationships between SDI and potential driving factors, including elevation, PET, precipitation, GWS, irrigation quota, and NDVI. Variables showing statistically significant correlations with SDI were retained as candidates for subsequent multivariate regression analysis. A measure of association, indicating both its strength and direction, between two variables, the Pearson correlation coefficient is derived from the following calculation [46]:

where r is the Pearson correlation coefficient; Xi and Yi are the variables, and , are their respective mean values.

- (2)

- Assessment of Multicollinearity

When multiple correlated factors are used as independent variables in a regression model, multicollinearity can inflate the variance of coefficient estimates and reduce model stability. To address this issue, the variance inflation factor (VIF) was calculated for all candidate variables to assess the severity of multicollinearity among them [47]. The VIF was calculated as follows:

where Ri2 is the coefficient of determination obtained when the i-th independent variable is treated as the dependent variable and regressed against the remaining independent variables.

- (3)

- Stepwise Regression

To address multicollinearity and obtain a parsimonious set of explanatory variables for SDI, stepwise regression was applied. This procedure iteratively adds or removes variables based on their statistical significance. Model selection was guided by maximizing explanatory power (R2), while reducing redundancy and multicollinearity, as indicated by the variance inflation factor (VIF) [48]. It was used here to identify the core, non-redundant drivers of soil salinization from the set of correlated candidate factors.

- (4)

- Autocorrelation Test

A key assumption of linear regression is the independence of model residuals, which may be violated in spatial or temporal data due to autocorrelation [49]. To validate the reliability of the final regression model, the Durbin–Watson (DW) test was applied to detect first-order autocorrelation in the model residuals. The DW statistic ranges from 0 to 4. A value close to 2 indicates no autocorrelation, a value toward 0 suggests positive autocorrelation, and a value toward 4 indicates negative autocorrelation [48].

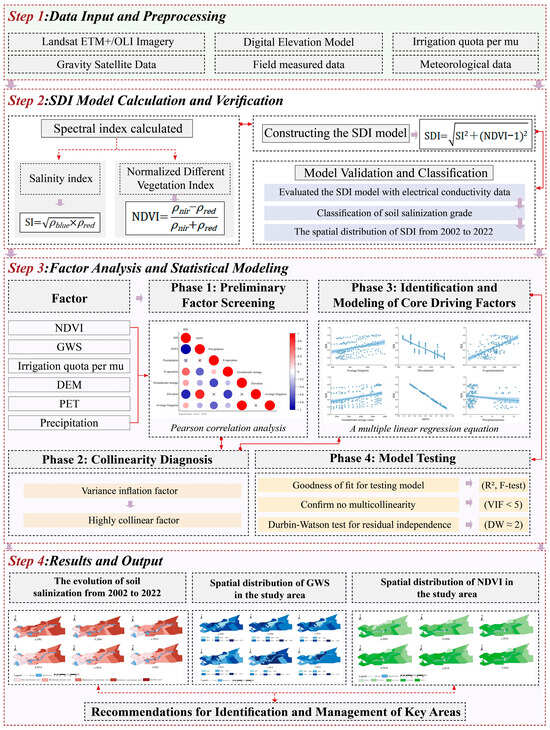

The data sources and research methods are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Methodology Flowchart.

3. Results

3.1. Spatiotemporal Distribution of Soil Salinization and Environmental Factors

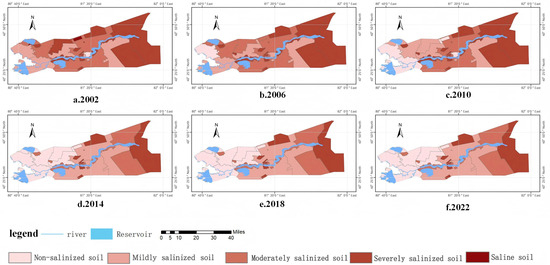

The spatiotemporal evolution of soil salinization from 2002 to 2022 at four-year intervals was illustrated in Figure 4. Area statistics of different soil salinization grades are summarized in Table 3. At the beginning of the study period, the Alar Reclamation Area was dominated by moderately and severely salinized soils, which were estimated to account for 75.0% of the total area in 2002. After 2010, a clear shift in salinization patterns was observed. Non-salinized and mildly salinized soils became the dominant classes, with their combined proportion increasing from 17.0% in 2002 to 76.3% in 2022. Over the same period, the proportion of moderately and severely salinized soils was reduced to 22.0%.

Figure 4.

Spatial distribution of soil salinization in the study area: (a) Spatial Distribution of Soil Salinization in 2002; (b) Spatial Distribution of Soil Salinization in 2006; (c) Spatial Distribution of Soil Salinization in 2010; (d) Spatial Distribution of Soil Salinization in 2014; (e) Spatial Distribution of Soil Salinization in 2018; (f) Spatial Distribution of Soil Salinization in 2022.

Table 3.

Area statistics of soil salinization grades in the Alar Reclamation Area from 2002 to 2022 (km2).

Spatially, soil salinity exhibited pronounced heterogeneity (Figure 4). Severely salinized soils were persistently concentrated in downstream low-lying areas in the eastern part of the region and along the Tarim River. Before 2010, the central and upstream areas were mainly occupied by moderately and mildly salinized soils. After 2010, an improvement in soil salinity conditions was observed in the upstream region, as reflected by a spatial transition from moderate to mild salinization and from mild to non-salinized conditions (Figure 4a–c). This change was most evident between 2010 and 2014, during which the proportion of severely salinized soils declined by approximately 30%, decreasing from 20.0% to 14.0%, while the proportion of non-salinized soils more than doubled, increasing from 11.9% to 24.3% (Table 3). After 2014, the spatial pattern of salinization grades remained relatively stable, with only minor fluctuations in the area proportions of each class, suggesting that soil salinity conditions approached a new dynamic equilibrium.

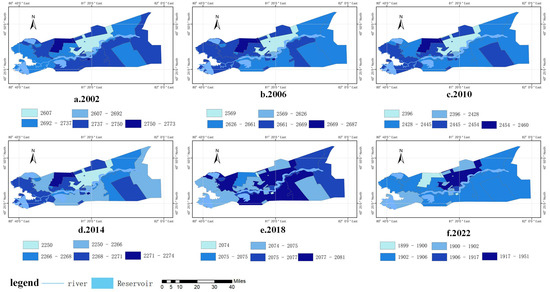

GWS in the study area exhibited a continuous decline from 2002 to 2022 (Table 4). In 2002, GWS reached its highest level, with a mean value of 2733.70 mm. By 2022, GWS had generally dropped below 2000 mm, with a mean value of 1906 mm. From 2002 to 2022, GWS in the Alar Reclamation Area decreased by 27%, corresponding to a mean annual decline rate of approximately 1.35%.

Table 4.

Statistical values of groundwater storage levels (mm) in the Alar Reclamation Area.

The spatial distribution of GWS exhibited pronounced heterogeneity (Figure 5). The central part of the reclamation area and the northern bank of the Tarim River showed the lowest GWS levels, while relatively high GWS occurred in the western delta front and other low-lying areas. In contrast, GWS was lower along the southern bank of the river and in the eastern part of the reclamation area. A comparison between Figure 4 and Figure 5 indicates clear spatial heterogeneity in the response of soil salinization to GWS decline. In 2002, 2006 and 2018, several small patches in the southeastern part of the reclamation area exhibited lower GWS yet higher salinization levels than the surrounding areas, showing a negative relationship. When GWS had declined to the 2014 level and continued to decrease thereafter, salinization intensity no longer changed in response to further reductions in GWS.

Figure 5.

Spatial distribution of GWS in the study area: (a) Spatial Distribution of GWS in 2002; (b) Spatial Distribution of GWS in 2006; (c) Spatial Distribution of GWS in 2010; (d) Spatial Distribution of GWS in 2014; (e) Spatial Distribution of GWS in 2018; (f) Spatial Distribution of GWS in 2022.

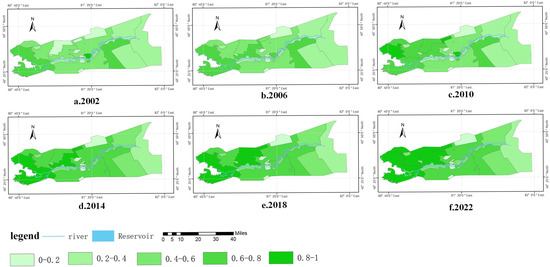

Over the past two decades, vegetation cover during the growing season in the Alar Reclamation Area has shown an overall increasing trend (Figure 6). Vegetation cover was lower in areas with relatively low elevation and higher in upland areas. In addition, regions with vegetation cover greater than 50% were largely associated with non-salinized and mildly salinized soils, whereas areas with vegetation cover below 50% were predominantly characterized by severe salinization. This indicates a negative association between vegetation growth and soil salinization at the same point in time.

Figure 6.

Spatial distribution of NDVI in the study area: (a) Spatial Distribution of NDVI in 2002; (b) Spatial Distribution of NDVI in 2006; (c) Spatial Distribution of NDVI in 2010; (d) Spatial Distribution of NDVI in 2014; (e) Spatial Distribution of NDVI in 2018; (f) Spatial Distribution of NDVI in 2022.

Statistical analysis of NDVI and GWS across different soil salinization levels was presented in Table 5. NDVI values decreased markedly with increasing salinization. The mean NDVI value was 0.822 in non-salinized areas but declined to 0.16 in saline areas. At the same time, the coefficient of variation (CV) of NDVI increased from 16.9% to 54.0%, indicating greater spatial variability of vegetation under higher salinity conditions. In contrast, GWS increased with salinization level, with mean values rising from 2386 mm in non-salinized areas to 2542 mm in saline areas. The CV of GWS showed a slight decline with increasing salinization, suggesting relatively more uniform groundwater conditions in areas with higher salinity.

Table 5.

Statistical Characteristics of NDVI and GWS under Different Soil Salinization Grades.

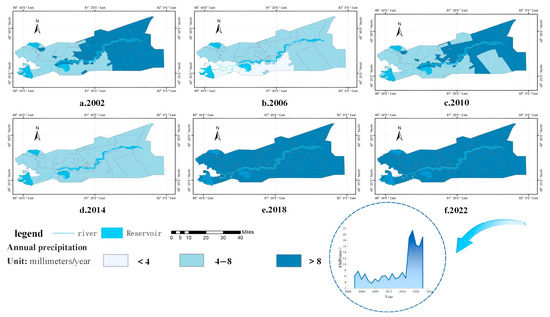

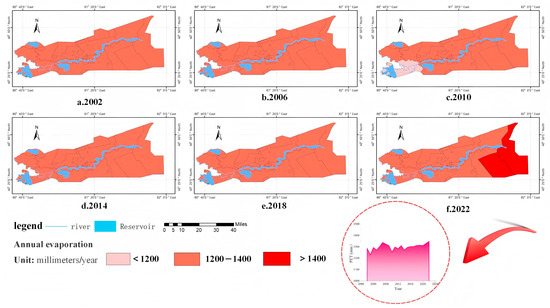

The climate changes in the Alar Reclamation Area over the past two decades are illustrated in Figure 7 and Figure 8. The results indicate that the annual potential evapotranspiration (PET) consistently remained above 1200 mm, demonstrating significant but stable interannual variation with no spatial heterogeneity. Annual precipitation was substantially lower than PET, showing uniform spatiotemporal distribution from 2002 to 2017. After 2017, precipitation experienced a slight increase without spatial variation. A comparison with Figure 5a–f in Figure 4 reveals that the observed climate patterns do not align with the evolution of soil salinization.

Figure 7.

Spatial distribution of precipitation in the study area: (a) Spatial Distribution of precipitation in 2002; (b) Spatial Distribution of precipitation in 2006; (c) Spatial Distribution of precipitation in 2010; (d) Spatial Distribution of precipitation in 2014; (e) Spatial Distribution of precipitation in 2018; (f) Spatial Distribution of precipitation in 2022.

Figure 8.

Spatial distribution of PET in the study area: (a) Spatial Distribution of PET in 2002; (b) Spatial Distribution of PET in 2006; (c) Spatial Distribution of PET in 2010; (d) Spatial Distribution of PET in 2014; (e) Spatial Distribution of PET in 2018; (f) Spatial Distribution of PET in 2022.

3.2. Model Development and Validation

3.2.1. Correlation Analysis

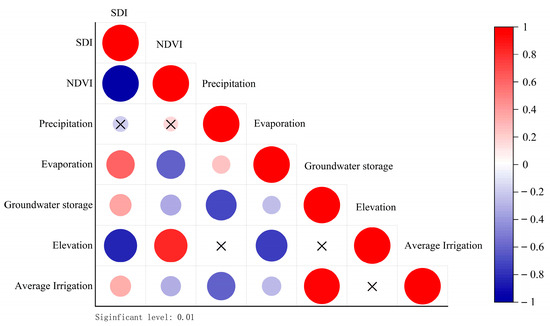

Figure 9 showed that SDI exhibited significant correlations with the different influencing factors. The correlation coefficient between precipitation and SDI was −0.18, indicating no significant relationship. For the remaining five factors, the absolute values of the correlation coefficients with SDI ranged from 0.34 to 0.98. SDI showed a strong negative correlation with NDVI and elevation, and a moderate positive correlation with irrigation quota per mu, GWS, and PET, indicating that these variables were suitable for subsequent regression analysis.

Figure 9.

Correlation heatmap of explanatory variables. Note: The ‘×’ in the figure indicates that the correlation coefficient is not significant at the α = 0.01 level (p > 0.01).

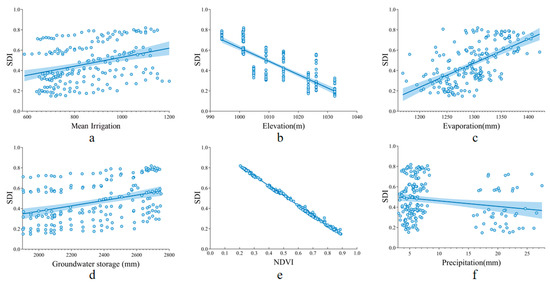

Linear correlation analyses were conducted sequentially between SDI and PET, precipitation, GWS, irrigation quota per unit area, NDVI, and elevation (Figure 10). The results showed that the factors influenced by human activities, NDVI, irrigation quota per unit area, and GWS, exhibited more pronounced linear relationships with SDI. In contrast, the climatic factors, including precipitation and PET, demonstrated weak linear relationships with SDI.

Figure 10.

Scatter plot of various influencing factors with the soil salinization index: (a) Scatter plot of mean Irrigation with the soil salinization index; (b) Scatter plot of elevation with the soil salinization index; (c) Scatter plot of evaporation with the soil salinization index; (d) Scatter plot of GWS with the soil salinization index; (e) Scatter plot of NDVI with the soil salinization index; (f) Scatter plot of precipitation with the soil salinization index.

3.2.2. Development of the SDI Regression Model

Multicollinearity among the variables was assessed using the VIF, and a VIF value below 10 indicated that multicollinearity could be ignored. The results (Table 6) showed that irrigation quota per mu and GWS exhibited moderate collinearity with the other variables. Combined with the correlation analysis results, irrigation quota per mu and GWS were found to be strongly positively correlated. Therefore, a stepwise regression model was employed to select variables and address the issue of multicollinearity among the independent variables.

Table 6.

Variance inflation factor of explanatory variables.

The results of the stepwise regression analysis are presented in Table 7. The R2 value was 0.998, indicating that 99.8% of the variation in SDI was explained by NDVI and GWS. The model passed the F-test, demonstrating its statistical validity. The resulting regression model was expressed as follows:

Table 7.

Stepwise regression analysis results (n = 97).

Multicollinearity diagnostics showed that all VIF values in the model were below 5, indicating the absence of multicollinearity. The DW value was close to 2, suggesting no autocorrelation and implying that the model parameters were independent and the model performed well. Comparison of the absolute values of the standardized regression coefficients indicated that vegetation cover was the most influential factor affecting SDI, followed by GWS.

Pearson correlation analysis was conducted for vegetation cover, GWS, and the other influencing factors (Table 8). The results showed that NDVI was significantly correlated with PET and elevation, whereas GWS was significantly correlated with precipitation and irrigation quota per mu. Therefore, vegetation cover and GWS were considered representative variables for these influencing factors and were used to construct the regression equation.

Table 8.

Pearson correlation coefficient between SDI and driving factors.

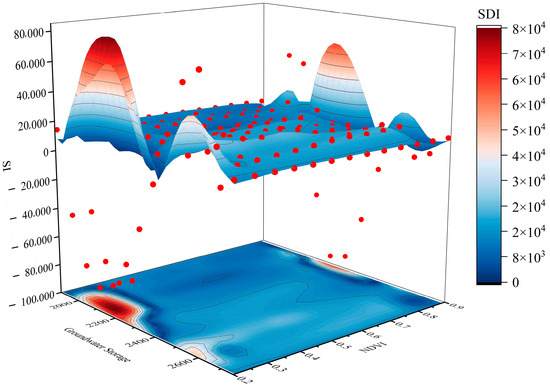

3.2.3. Model Validation

Based on the SDI values for 2002–2022 and the two variables retained by the stepwise regression model (NDVI and GWS), a three-dimensional surface and regression model were constructed (Figure 11). GWS, NDVI, and SDI were assigned to the X-, Y-, and Z-axes, respectively, to generate a GWS-NDVI-SDI three-dimensional scatter plot. Using 97 field samples collected in April 2024 for model fitting, the coefficient of determination was 0.8677, indicating a good level of agreement.

Figure 11.

Three-dimensional surface plot of soil salinization index.

4. Discussion

4.1. Factors Influencing the Evolution of Soil Salinization

A significant improvement in soil salinization was observed from 2002 to 2014 in the Alar Reclamation Area, after which the trend plateaued with minimal change up to 2022. This overall trajectory is corroborated by the findings of Dai et al. [50], who reported comparable conditions for the area from 2011 to 2021.

The Alar Reclamation Area is situated on the northern margin of the Tarim Basin, extending between the southern foothills of the Tianshan Mountains to the north and the northern limit of the Taklimakan Desert to the south. Groundwater in the region is primarily recharged by meltwater from high-mountain glaciers and snow. During downstream flow, the dissolution of soluble minerals in the underlying strata increases groundwater salinity. Shallow groundwater at depths of 2–5 m serves as the main source of surface salt accumulation, as long-term strong evaporation drives upward capillary rise [51]. The results showed that GWS in the Alar Reclamation Area continuously decreased from 2002 to 2022, accompanied by a persistent decline in groundwater levels. The correlation coefficient between SDI and GWS ranged from 0.89 to 0.97, indicating a strong positive relationship. This finding is consistent with studies by Chang [4], who reported that salt transport from shallow groundwater in irrigated farmland strongly influences soil salinity. As groundwater depth increased, the capillary rise in salts toward the soil surface weakened, thereby reducing the risk of secondary salinization. A comparison of the spatial patterns in Figure 4 and Figure 5 demonstrated that soil salinization in the Alar Reclamation Area was no longer strongly affected by declining groundwater levels after 2014. This is attributable to the groundwater depth exceeding the capillary rise threshold, which agrees with the findings of Li [52] and Xu [53] regarding capillary-driven water–salt transport. Due to severe freshwater scarcity in the region, slightly saline water has been widely used for irrigation. The predominant irrigation method, mulched drip irrigation, greatly reduces soil surface evaporation and suppresses upward capillary salt transport from groundwater. Consequently, with the large-scale adoption of drip irrigation, soil salinization has been effectively mitigated [54].

Analysis of the relationship between soil salinization, vegetation, and geomorphology showed that areas with vegetation cover greater than 50% were largely associated with non-salinized and mildly salinized soils, whereas regions with vegetation cover below 50% were predominantly characterized by severe salinization, indicating a negative relationship between the two. This pattern can be explained by the presence of xerophytic and halophytic species, such as Artemisia songarica, Alhagi sparsifolia, and Elaeagnus angustifolia, which are widely distributed in the Alar Reclamation Area. Ahmadi et al. [55] reported that halophytic species play an important role in improving saline–alkali soils. With deep root systems extending below 20–30 cm, halophytes extract soil moisture from deeper layers, weaken capillary-driven water–salt transport, and enhance soil water and nutrient retention.

The climatic factors influencing soil salinization in arid regions primarily include precipitation and PET. Correlation analysis based on the long-term dataset for the Alar Reclamation Area indicated that climate variables were not significantly associated with the evolution of soil salinization. As shown in Figure 7 and Figure 8, the annual mean PET in the Alar Reclamation Area remained above 1200 mm from 2002 to 2022, indicating consistently high evaporative demand. Annual precipitation was much lower than PET and showed no spatial heterogeneity across the region. Therefore, this study concluded that climate factors were relatively stable over the long-term period and had no significant effect on the evolution of soil salinization.

4.2. Analysis of the Soil Salinization Index Regression Model

Based on stepwise regression, the SDI regression model constructed in this study ultimately selected vegetation cover (NDVI) and groundwater storage (GWS) as the two core explanatory variables. The resulting regression relationship was SDI = 0.946 − 0.959 × NDVI + 0.318 × GWS. The model achieved a coefficient of determination of R2 = 0.998 and satisfied diagnostic criteria for multicollinearity (VIF < 5) and residual autocorrelation (Durbin–Watson ≈ 1.876), indicating a high level of fitting accuracy and statistical robustness. In addition, the consistency between the model results and field observations reached 86.77%, representing an improvement compared with the dual-index framework based on NDVI and SI (83.45%). These results not only identify the key driving factors of soil salinization processes but also provide a simplified and efficient quantitative tool for salinization monitoring and regulation in arid regions.

In the single-factor correlation analysis, soil salinization was significantly correlated with vegetation cover (NDVI), irrigation quota, groundwater storage (GWS), and surface elevation, whereas no significant associations were observed with climatic variables. Climatic variables were therefore excluded from the stepwise regression analysis. Based on the correlation results, the final regression model retained NDVI and GWS as the core explanatory variables, indicating that the effects of other correlated factors were effectively captured by these two variables and that multicollinearity was appropriately controlled. The positive correlation between GWS and SDI indicates that shallow groundwater provides an important pathway for salt transport toward surface soils. The strong collinearity between GWS and irrigation quota, reflected by high VIF values, further suggests that irrigation activities regulate groundwater dynamics and thereby indirectly influence the spatial differentiation of soil salinization. This pattern is consistent with the irrigation-dependent agricultural system of the Alar Reclamation Area [23,24]. The high contribution of NDVI in the regression model reflects both the inhibitory effects of soil salinization on vegetation growth and the potential role of vegetation in moderating salinity conditions. A pronounced negative covariation between NDVI and soil salinization was captured by the model. Moreover, the significant correlations of NDVI with surface elevation (r = 0.835 **, Table 8) and potential evapotranspiration (r = −0.619 **, Table 8) indicate that vegetation cover can indirectly represent topographic and climatic constraints, and their combined influence on soil salinization [16,18]. Taken together, GWS and NDVI capture the two key pathways governing soil salinization, namely water–salt transport and biological regulation, and thus serve as the most representative explanatory variables. The standardized regression coefficient of NDVI (absolute value 0.987) was substantially larger than that of GWS (0.305), indicating that vegetation cover was the dominant control on soil salinization. This result is consistent with the spatial coupling observed from 2002 to 2022 between increased vegetation cover (34.4%) and alleviated soil salinization in the Alar Reclamation Area (Figure 4 and Figure 6).

The linear regression model used in this study provides a concise and interpretable description of the relationships between soil salinization and its key drivers, facilitating the identification of dominant linear effects and supporting management-oriented analysis. However, its inherent linear assumption limits the representation of nonlinear responses and interactions, suggesting that future studies could incorporate machine learning approaches, such as random forests or gradient boosting models, to further explore more complex relationships.

This study provides a theoretical basis for the integrated utilization of saline–alkali lands in the Alar Reclamation Area and offers a reference for soil salinization studies in other arid oasis regions. However, it should be noted that the quantitative response relationships established in this study were derived under the specific geographical conditions and management practices of the Alar Reclamation Area, and their applicability should be evaluated with caution when extended to other regions. In addition, both the SDI and the soil salinization grades in this study were based on electrical conductivity determined using oven-dried soil, which primarily reflects relative salinization levels. Comparisons with studies employing different electrical conductivity measurement methods should therefore account for potential numerical shifts arising from methodological differences. Finally, the quantitative analysis relied on one year of ground observations. Longer time series are needed to assess the stability of the identified relationships and to support analyses of soil salinization dynamics over extended periods.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the spatiotemporal dynamics of soil salinization in the Alar Reclamation Area from 2002 to 2022 and identified its driving factors. Long-term analysis showed that soil salinization improved markedly over the study period. From 2002 to 2010, the region was dominated by moderately and severely salinized soils, whereas from 2010 to 2022, non-salinized and mildly salinized soils became predominant, with the areas of moderate and severe salinization declining substantially. The spatial distribution of salinization remained largely unchanged from 2014 to 2022. Spatially, soil salinity exhibited pronounced heterogeneity: severely salinized soils were mainly concentrated in downstream depressions and along the Tarim River, while non-salinized and mildly salinized soils were widely distributed in the central and upstream parts of the region.

Univariate correlation analysis showed that the soil salinization index (SDI) was highly negatively correlated with vegetation cover (NDVI) and highly positively correlated with irrigation quota per mu and GWS, whereas its correlations with precipitation and PET were relatively weak. The variance inflation factor analysis indicated strong collinearity between GWS and irrigation quota per mu. Subsequently, stepwise regression was applied to screen the independent variables, and NDVI and GWS were identified as the core driving factors explaining variations in SDI. The resulting regression model (SDI = 0.946 − 0.959 × NDVI + 0.318 × GWS) exhibited a high degree of goodness-of-fit (R2 = 0.998) and showed no significant multicollinearity (VIF < 5) or autocorrelation (DW ≈ 1.876), demonstrating its effectiveness for accurately retrieving soil salinization levels in the study area.

From 2002 to 2022, GWS in the Alar Reclamation Area declined by 27%, with a mean annual decrease of approximately 1.35%. When groundwater depth remained above the 2014 GWS level for an extended period, further increases in depth no longer contributed to continued reductions in soil salinization. Therefore, regulating irrigation intensity is recommended as a means to mitigate salinization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.H. and J.W.; methodology, R.G.; software, R.G.; validation, S.L. and D.F.; formal analysis, R.G.; investigation, Y.M. and F.L.; resources, Y.G.; data curation, R.G.; writing—original draft preparation, R.G.; writing—review and editing, R.G.; visualization, R.G. and J.W.; supervision, Y.G.; project administration, Y.G.; funding acquisition, Y.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Key Industry Innovation Development Support Program in Southern Xinjiang of Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps, grant number 2021DB017, Development and application of specialized membranes and equipment for the desalination of shallow saline water of Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps, grant number 2025AB077, Study on the Groundwater Level Threshold of Soil Salinization in Different Soils in the Alar Reclamation Area of Tarim University, grant number TDCR1202361.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in anyorganization or entity with any financial or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materialsdiscussed in this manuscript.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NDVI | normalized different vegetation index |

| SI | salinity index |

| SDI | salinization detection index |

| GWS | groundwater storage |

| GWSA | groundwater storage anomalies |

| VIF | variance inflation factor |

| D-W | Durbin–Watson |

| PET | Potential Evapotranspiration |

| NASA | National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

| DLR | Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt e.V. |

References

- Stavi, I.; Thevs, N.; Priori, S. Soil Salinity and Sodicity in Drylands: A Review of Causes, Effects, Monitoring, and Restoration Measures. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 712831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Gao, M.; Sun, Q.; Hou, G.; Zhao, Y. Formation and evolution of soil salinization based on multivariate statistical methods in Ningxia Plain, China. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1186779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Feng, Q.; Li, Y.; Deo, R.C.; Liu, W.; Zhu, M.; Zheng, X.; Liu, R. An interplay of soil salinization and groundwater degradation threatening coexistence of oasis-desert ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 150599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Yang, G.; Li, S.; Wang, H.; Song, Y. Spatial characteristics and critical groundwater depth of soil salinization in arid artesian irrigation area of northwest China. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 307, 109196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Sun, C.; Chen, Y.; Chen, W.; Xiang, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, Y. Recent Oasis Dynamics and Ecological Security in the Tarim River Basin, Central Asia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asfaw, E.; Suryabhagavan, K.; Argaw, M. Soil salinity modeling and mapping using remote sensing and GIS: The case of Wonji sugar cane irrigation farm, Ethiopia. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2018, 17, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohare, J.; Nair, R.; Pandey, S.K.; Sharma, S.K.; Ramakrishnan, R.S. Assessment of Classification and Accuracy of Land Use/Land Cover in Jabalpur District, Madhya Pradesh, India: An Analysis by Remote Sensing and GIS Application. Int. J. Environ. Clim. Change 2024, 14, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ding, J.; Yu, D.; Ma, X.; Zhang, Z.; Ge, X.; Teng, D.; Li, X.; Liang, J.; Lizaga, I.; et al. Capability of Sentinel-2 MSI data for monitoring and mapping of soil salinity in dry and wet seasons in the Ebinur Lake region, Xinjiang, China. Geoderma 2019, 353, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Chen, X.; Luo, G.; Ding, J.; Chen, X. Detecting soil salinity with arid fraction integrated index and salinity index in feature space using Landsat TM imagery. J. Arid. Land 2013, 5, 340–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, F.; Schillaci, C.; Keshavarzi, A.; Başayiğit, L. Predictive Mapping of Electrical Conductivity and Assessment of Soil Salinity in a Western Türkiye Alluvial Plain. Land 2022, 11, 2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, S.; Sertel, E.; Roscher, R.; Tanik, A.; Hamzehpour, N. Assessment of soil salinity using explainable machine learning methods and Landsat 8 images. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 130, 103879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Qin, J.; Kayumba, P.M. Historic and Simulated Desert-Oasis Ecotone Changes in the Arid Tarim River Basin, China. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Minasny, B.; Malone, B.P.; Mcbratney, A.B. Pedology and digital soil mapping (DSM). Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2019, 70, 216–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeraatpisheh, M.; Ayoubi, S.; Jafari, A.; Tajik, S.; Finke, P. Digital mapping of soil properties using multiple machine learning in a semi-arid region, central Iran. Geoderma 2019, 338, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaledian, Y.; Miller, B.A. Selecting appropriate machine learning methods for digital soil mapping. Appl. Math. Model. 2020, 81, 401–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chang, S.X.; Salifu, K.F. Soil texture and layering effects on water and salt dynamics in the presence of a water table: A review. Environ. Rev. 2014, 22, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Arrouays, D.; Mulder, V.L.; Poggio, L.; Minasny, B.; Roudier, P.; Libohova, Z.; Lagacherie, P.; Shi, Z.; Hannam, J.; et al. Digital mapping of GlobalSoilMap soil properties at a broad scale: A review. Geoderma 2022, 409, 115567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, H.; Quinn, N.; Horswell, M.; White, P. Assessing Vegetation Response to Soil Moisture Fluctuation under Extreme Drought Using Sentinel-2. Water 2018, 10, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajmohan, N.; Masoud, M.H.; Niyazi, B.A. Impact of evaporation on groundwater salinity in the arid coastal aquifer, Western Saudi Arabia. CATENA 2021, 196, 104864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokri-Kuehni, S.M.S.; Raaijmakers, B.; Kurz, T.; Or, D.; Helmig, R.; Shokri, N. Water Table Depth and Soil Salinization: From Pore-Scale Processes to Field-Scale Responses. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56, e2019WR026707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhao, D.; Zhou, P.; Qu, S.; Liao, F.; Wang, G. Hydrochemical Characteristics of Groundwater and Dominant Water–Rock Interactions in the Delingha Area, Qaidam Basin, Northwest China. Water 2020, 12, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wouters, B.; Bonin, A.; Chambers, D.P.; Riva, R.E.M.; Sasgen, I.; Wahr, J. GRACE, time-varying gravity, Earth system dynamics and climate change. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2014, 77, 116801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, N.A.; Haghighi, A.T.; Rossi, P.M.; Tourian, M.J.; Kløve, B. Monitoring Groundwater Storage Depletion Using Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) Data in Bakhtegan Catchment, Iran. Water 2019, 11, 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Qu, X.; Wang, L.; Tong, S.; Zhang, M.; Li, X.; Zhang, W. Impacts of groundwater storage variability on soil salinization in a semi-arid agricultural plain. Geoderma 2025, 454, 117162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Wortmann, M.; Duethmann, D.; Menz, C.; Shi, F.; Zhao, C.; Su, B.; Krysanova, V. Adaptation strategies of agriculture and water management to climate change in the Upper Tarim River basin, NW China. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 203, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Li, X.; Johnson, V.C.; Tan, M.L.; Kung, H.-T.; Shi, J.; Bahtebay, J.; He, X. Methodology for Mapping the Ecological Security Pattern and Ecological Network in the Arid Region of Xinjiang, China. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Yu, J.; Li, S.; Liu, J.; Yang, G.; Wang, G.; Wang, J.; Song, N. Evolution of Crop Planting Structure in Traditional Agricultural Areas and Its Influence Factors: A Case Study in Alar Reclamation. Agronomy 2024, 14, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N. Farmland Soilsalinization Monitoring and Management Zones Delineation Using Remote Sensing—A Case Study in the Alaer Reclamation Area, Southern Xinjiang. Ph.D. Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.D. The Study on Spatial Variability Characteristics of Soil Salinity and Management Zoning in Alar Reclamation Area. Master’s Thesis, Tarim University, Alar, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Franks, S.; Rengarajan, R. Evaluation of Copernicus DEM and Comparison to the DEM Used for Landsat Collection-2 Processing. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rengarajan, R.; Choate, M.; Hasan, N.; Denevan, A. Co-registration accuracy between Landsat-8 and Sentinel-2 orthorectified products. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 301, 113947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, X.; Chan, N.W.; Kung, H.-T.; Ariken, M.; Zhou, X.; Wang, Y. Regional suitability prediction of soil salinization based on remote-sensing derivatives and optimal spectral index. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 775, 145807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Jia, K.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; El-Hamid, H.T.A. Remote Sensing Inversion for Simulation of Soil Salinization Based on Hyperspectral Data and Ground Analysis in Yinchuan, China. Nat. Resour. Res. 2021, 30, 4641–4656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Zhou, C.; Zhou, C.; Ma, H.; Wang, Z. Soil Salinity Inversion Model of Oasis in Arid Area Based on UAV Multispectral Remote Sensing. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannari, A.; Musa, N.H.M.; Abuelgasim, A.; El-Battay, A. Sentinel-MSI and Landsat-OLI Data Quality Characterization for High Temporal Frequency Monitoring of Soil Salinity Dynamic in an Arid Landscape. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2020, 13, 2434–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, T.B.; Castanheira, N.; Oliveira, A.R.; Paz, A.M.; Darouich, H.; Simionesei, L.; Farzamian, M.; Gonçalves, M.C. Soil salinity assessment using vegetation indices derived from Sentinel-2 multispectral data. application to Lezíria Grande, Portugal. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 241, 106387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Guo, B.; Zhang, R. A Novel Approach to Detecting the Salinization of the Yellow River Delta Using a Kernel Normalized Difference Vegetation Index and a Feature Space Model. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.-A.; Liou, Y.-A.; Tran, H.-P.; Hoang, P.-P.; Nguyen, T.-H. Soil salinity assessment by using near-infrared channel and Vegetation Soil Salinity Index derived from Landsat 8 OLI data: A case study in the Tra Vinh Province, Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Prog. Earth Planet. Sci. 2020, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoud, A.A.; Koike, K.; Atwia, M.G.; El-Horiny, M.M.; Gemail, K.S. Mapping soil salinity using spectral mixture analysis of landsat 8 OLI images to identify factors influencing salinization in an arid region. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2019, 83, 101944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, V.; Rodell, M.; Eicker, A. Using Satellite-Based Terrestrial Water Storage Data: A Review. Surv. Geophys. 2023, 44, 1489–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, R.; Chevez, E.P. Spatial and Seasonal Variations of Water and Salt Movement in the Vadose Zone at Salt-Impacted Sites. Water 2018, 10, 1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.A.; Nauman, M.A.; Bashir, R.N.; Jahangir, R.; Alroobaea, R.; Binmahfoudh, A.; Alsafyani, M.; Wechtaisong, C. Context Aware Evapotranspiration (ETs) for Saline Soils Reclamation. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 110050–110063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Gao, X.; Li, S.; Bundschuh, J. A review of the distribution, sources, genesis, and environmental concerns of salinity in groundwater. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 41157–41174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nosetto, M.D.; Acosta, A.; Jayawickreme, D.; Ballesteros, S.; Jackson, R.; Jobbágy, E. Land-use and topography shape soil and groundwater salinity in central Argentina. Agric. Water Manag. 2013, 129, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, F.; He, L.; Li, Q.; Li, B.; Zhang, K.; Yang, H.; Zhang, C. Vermicompost Combined with Soil Conditioner Improves the Ecosystem Multifunctionality in Saline-Alkali Land. Water 2023, 15, 3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schober, P.; Boer, C.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation Coefficients: Appropriate Use and Interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.; Song, H.; Zhu, L. The iterated score regression estimation algorithm for PCA-based missing data with high correlation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, R.; Goodhew, J. The Robustness of the Durbin-Watson Test. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1981, 63, 136–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.d.S.; Paula, G.A.; Lana, G.C. Estimation and diagnostic for partially linear models with first-order autoregressive skew-normal errors. Comput. Stat. 2021, 37, 445–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Guan, Y.; Feng, C.; Jiang, M.; He, X. Extraction and analysis of soil salinization information of Alar reclamation area based on spectral index modeling. Remote Sens. Nat. Resour. 2023, 35, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ye, P.; Wu, Y.; Zhai, E. Experimental study on simultaneous heat-water-salt migration of bare soil subjected to evaporation. J. Hydrol. 2022, 609, 127710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Li, X.; He, X.; Yang, G.; Du, Y.; Li, X. Groundwater Dynamic Characteristics with the Ecological Threshold in the Northwest China Oasis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Sun, C.; Qu, Z.; Huang, Q.; Ramos, T.B.; Huang, G. Groundwater Recharge and Capillary Rise in Irrigated Areas of the Upper Yellow River Basin Assessed by an Agro-Hydrological Model. Irrig. Drain. 2015, 64, 587–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Liu, H.; Gong, P.; Li, P.; Li, L.; Xu, Q.; Xue, B.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, R. Model-Based Optimization of Design Parameters of Subsurface Drain in Cotton Field under Mulch Drip Irrigation. Water 2022, 14, 3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, F.; Mohammadkhani, N.; Servati, M. Halophytes play important role in phytoremediation of salt-affected soils in the bed of Urmia Lake, Iran. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.