Temporal Variability of Bioindicators and Microbial Source-Tracking Markers over 24 Hours in River Water

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

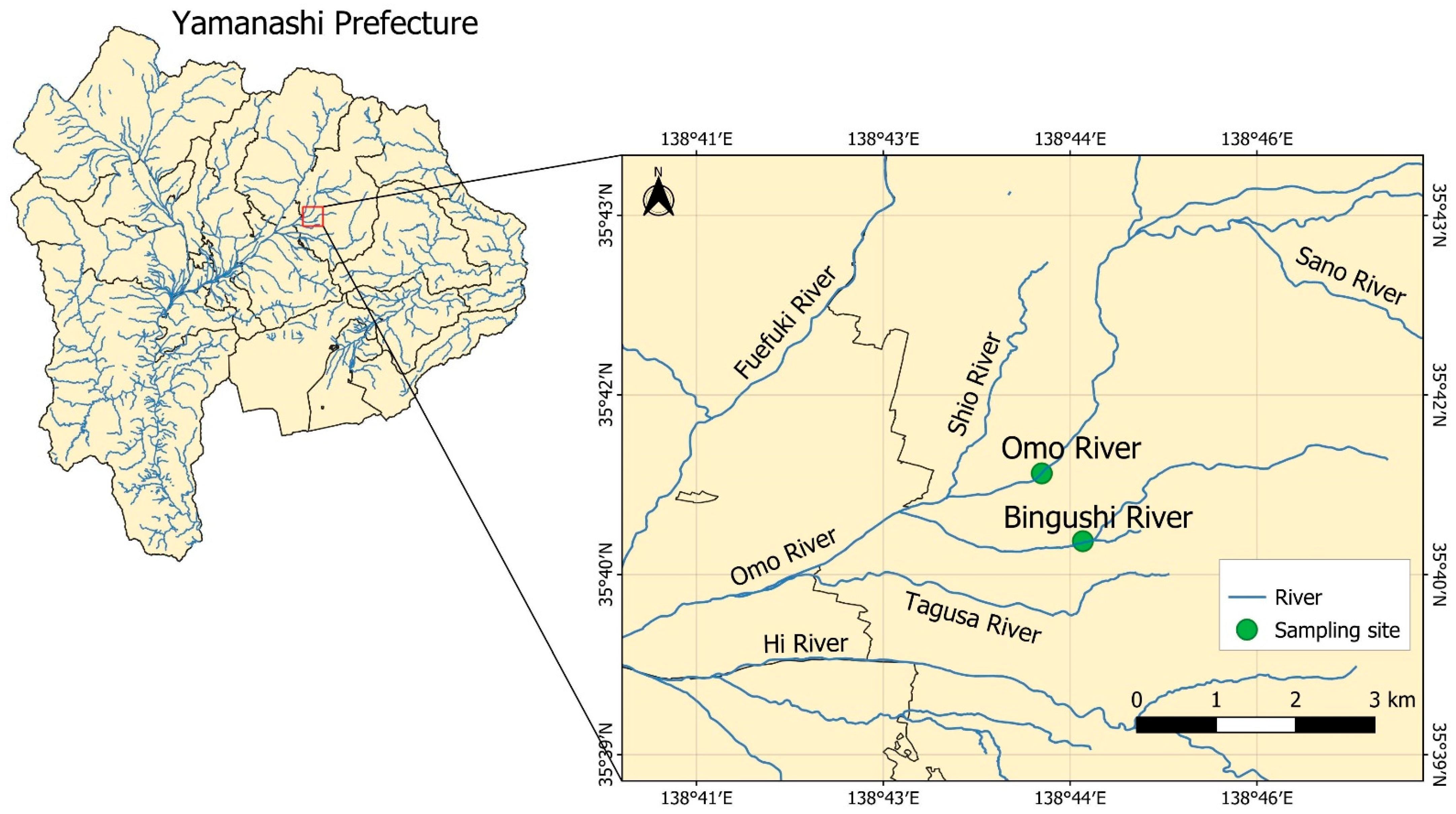

2.1. Collection and Filtration of River Water Samples

2.2. eDNA Extraction from River Water Samples

2.3. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) of Bioindicators, MST Markers, and E. coli

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

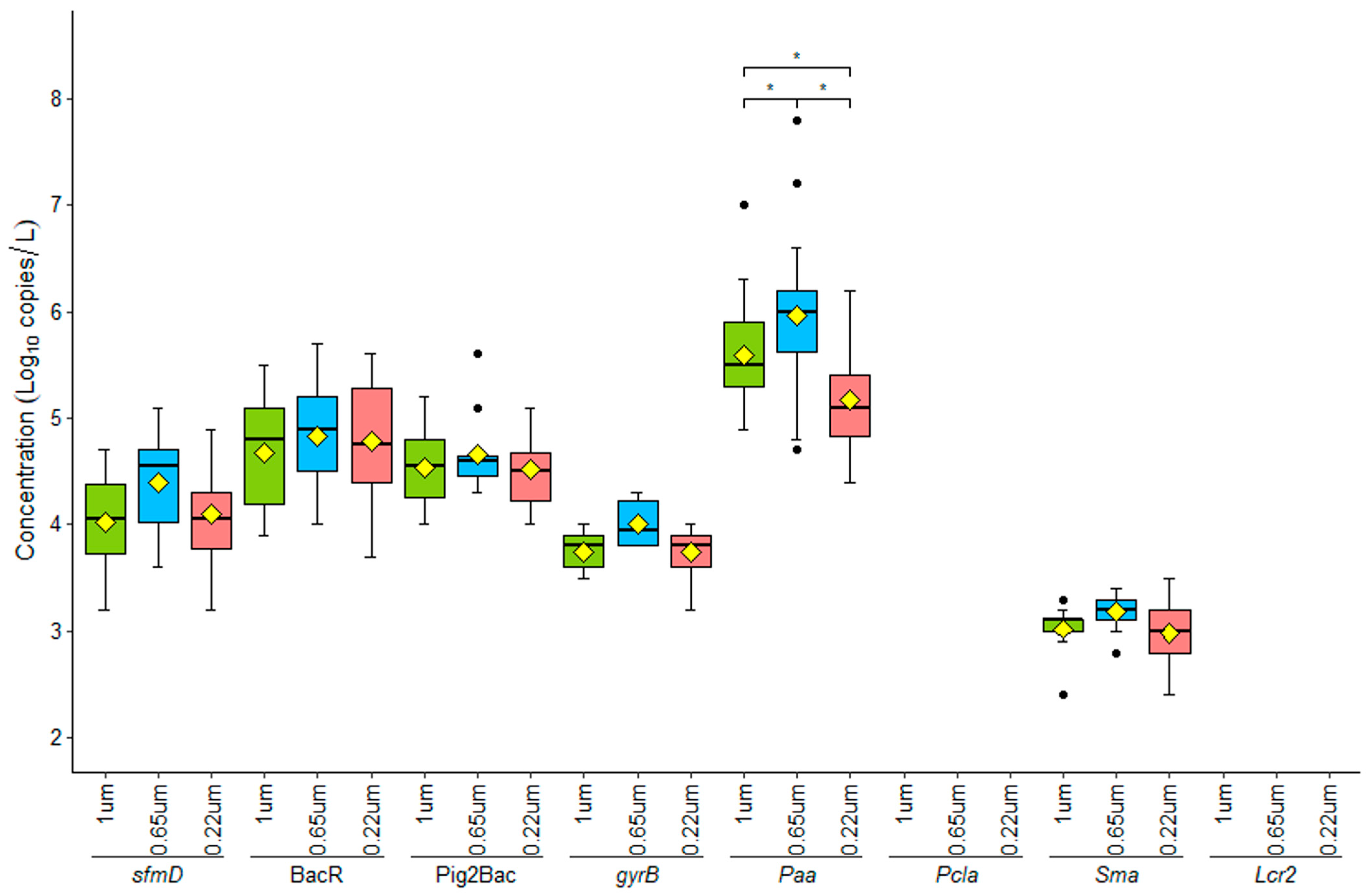

3.1. Assessment of Optimal Filter Pore Size for eDNA Collection

3.2. Detection of sfmD, MST Markers, and Bioindicators in the Omo and Bingushi Rivers

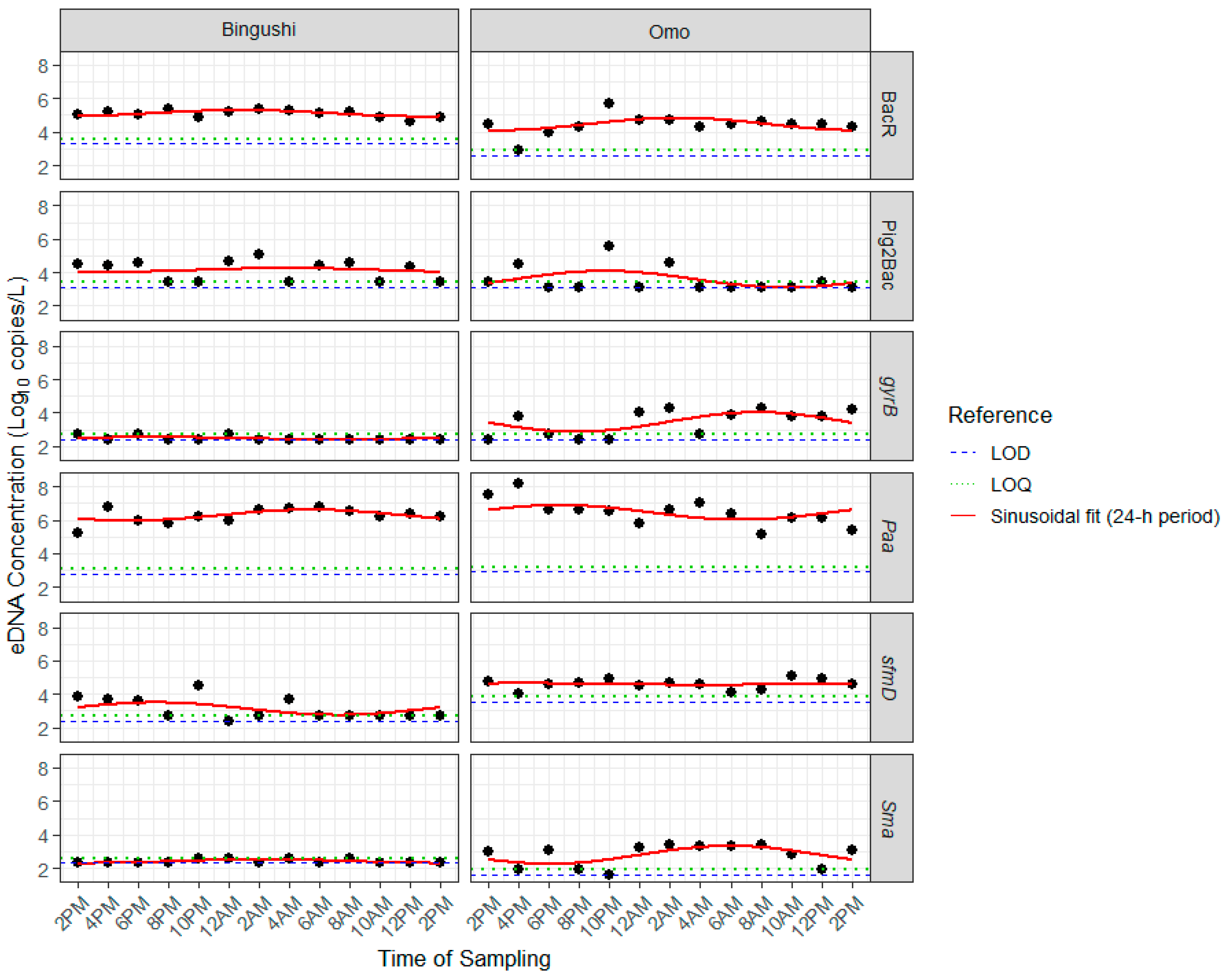

3.3. Variations in Concentrations of Bioindicators, MST Markers, and sfmD over 24 h

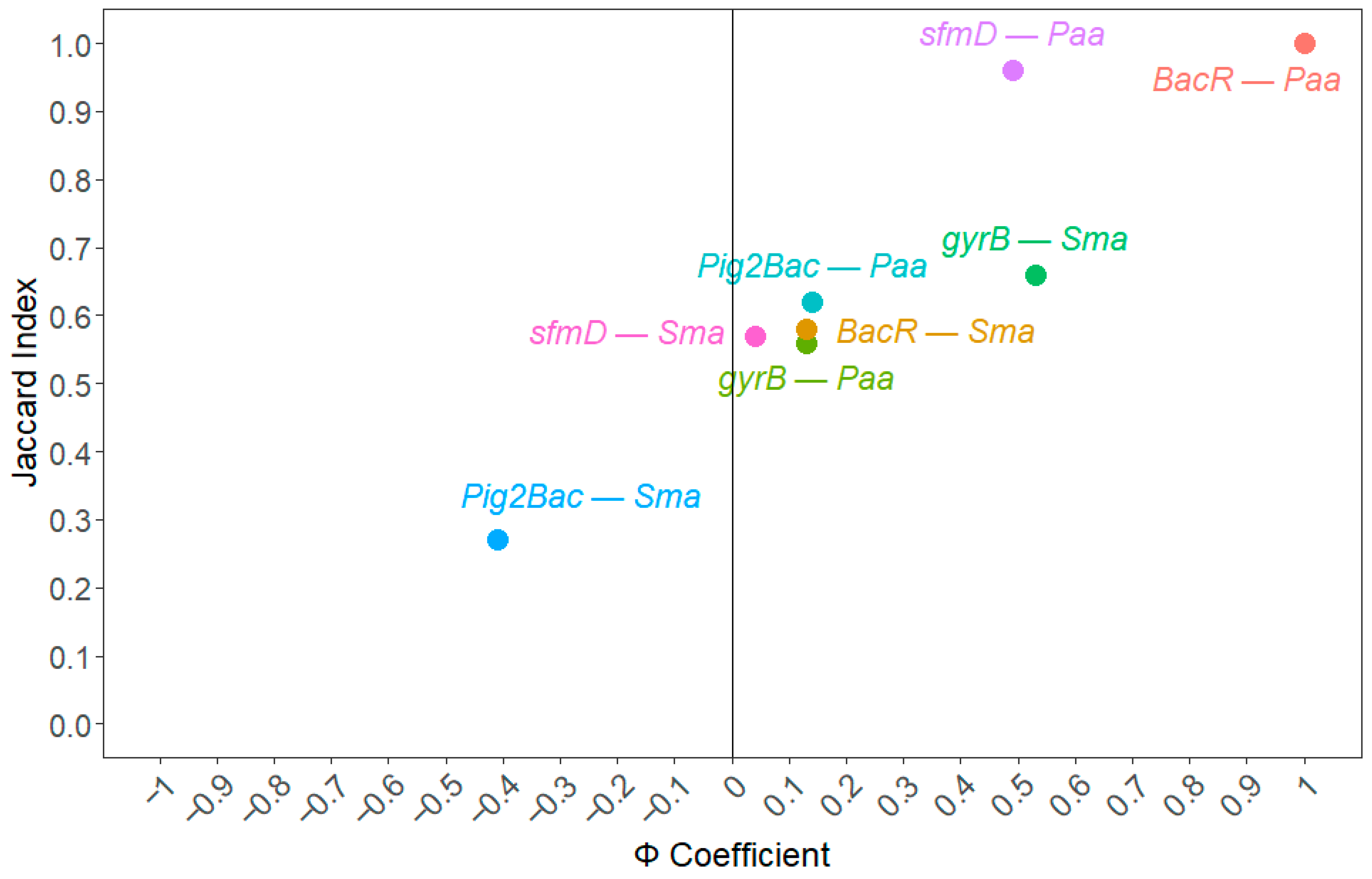

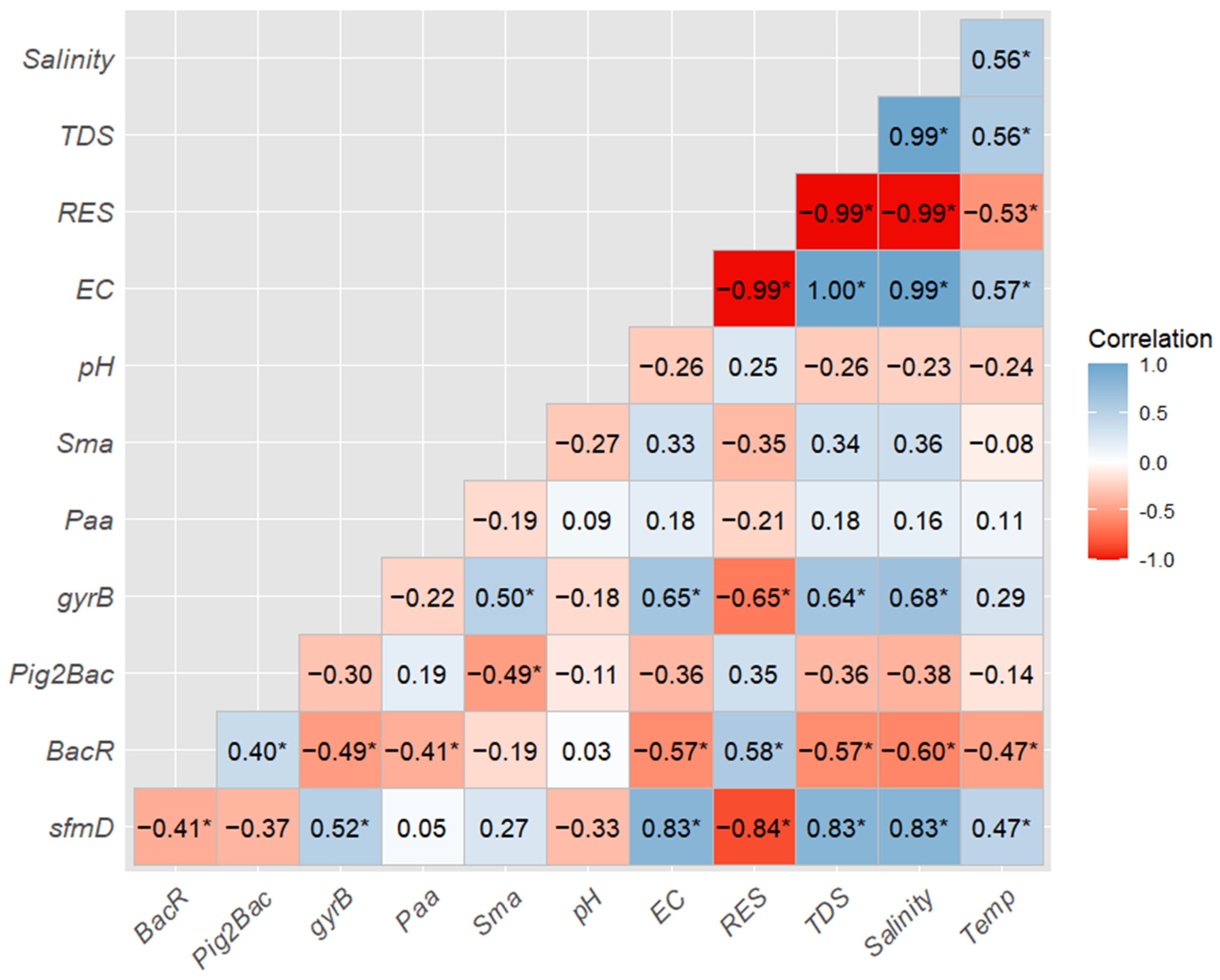

3.4. Correlation Analysis of sfmD, MST Markers, Bioindicators, and Water Quality Parameters

4. Discussion

4.1. Optimal Filter Pore Size for eDNA Capture

4.2. sfmD, MST Markers, and Bioindicators in the Omo and Bingushi Rivers

4.3. Variation in Bioindicators, MST Markers, and E. coli Concentrations over 24 h

4.4. Relationship of sfmD, MST Markers, Bioindicators, and Water Quality Parameters

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Garlapati, D.; Charankumar, B.; Ramu, K.; Madeswaran, P.; Ramana Murthy, M.V. A review on the applications and recent advances in environmental DNA (eDNA) metagenomics. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2019, 18, 389–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, H.M.; Leadley, P.W.; Proença, V.; Alkemade, R.; Scharlemann, J.P.; Fernandez-Manjarrés, J.F.; Araújo, M.B.; Balvanera, P.; Biggs, R.; Cheung, W.W.L.; et al. Scenarios for global biodiversity in the 21st century. Science 2010, 330, 1496–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dirzo, R.; Young, H.S.; Galetti, M.; Ceballos, G.; Isaac, N.J.; Collen, B. Defaunation in the Anthropocene. Science 2014, 345, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikitch, E.K. A tool for finding rare marine species. Science 2018, 360, 1180–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, P.F.; Willerslev, E. Environmental DNA—An emerging tool in conservation for monitoring past and present biodiversity. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 183, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentini, A.; Taberlet, P.; Miaud, C.; Civade, R.; Herder, J.; Thomsen, P.F.; Bellemain, E.; Besnard, A.; Coissac, E.; Boyer, F.; et al. Next-generation monitoring of aquatic biodiversity using environmental DNA metabarcoding. Mol. Ecol. 2016, 25, 929–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlowski, J.; Apothéloz-Perret-Gentil, L.; Altermatt, F. Environmental DNA: What’s behind the term? Clarifying the terminology and recommendations for its future use in biomonitoring. Mol. Ecol. 2020, 29, 4258–4264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Ezpeleta, N.; Zinger, L.; Kinziger, A.; Bik, H.M.; Bonin, A.; Coissac, E.; Emerson, B.C.; Lopes, C.M.; Pelletier, T.A.; Taberlet, P.; et al. Biodiversity monitoring using environmental DNA. Mol. Ecol. Res. 2021, 21, 1405–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, R.P.; Port, J.A.; Yamahara, K.M.; Crowder, L.B. Using environmental DNA to census marine fishes in a large mesocosm. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minamoto, T.; Yamanaka, H.; Takahara, T.; Honjo, M.N.; Kawabata, Z.I. Surveillance of fish species composition using environmental DNA. Limnology 2012, 13, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilliod, D.S.; Goldberg, C.S.; Arkle, R.S.; Waits, L.P. Factors influencing detection of eDNA from a stream-dwelling amphibian. Mol. Ecol. Res. 2014, 14, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahara, T.; Minamoto, T.; Yamanaka, H.; Doi, H.; Kawabata, Z. Estimation of fish biomass using environmental DNA. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahara, T.; Minamoto, T.; Doi, H. Using environmental DNA to estimate the distribution of an invasive fish species in ponds. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, P.F.; Kielgast, J.; Iversen, L.L.; Wiuf, C.; Rasmussen, M.; Gilbert, M.T.P.; Orlando, L.; Willerslev, E. Monitoring endangered freshwater biodiversity using environmental DNA. Mol. Ecol. 2011, 21, 2565–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, P.F.; Kielgast, J.; Iversen, L.L.; Møller, P.R.; Rasmussen, M.; Willerslev, E. Detection of a diverse marine fish fauna using environmental DNA from seawater samples. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e41732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saccò, M.; Guzik, M.T.; van der Heyde, M.; Nevill, P.; Cooper, S.J.; Austin, A.D.; Coates, P.J.; Allentoft, M.E.; White, N.E. eDNA in subterranean ecosystems: Applications, technical aspects, and future prospects. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 820, 153223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClenaghan, B.; Fahner, N.; Cote, D.; Chawarski, J.; McCarthy, A.; Rajabi, H.; Singer, G.; Hajibabaei, M. Harnessing the power of eDNA metabarcoding for the detection of deep-sea fishes. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, Z.T.; Stat, M.; Heydenrych, M.; DiBattista, J.D. Environmental DNA for biodiversity monitoring of coral reefs. In Coral Reefs of the World; van Oppen, M.J.H., Aranda Lastra, M., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 203–224. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, C.I.; Connell, L.; Lee, C.K.; Cary, S.C. Evidence of plant and animal communities at exposed and subglacial (cave) geothermal sites in Antarctica. Polar Biol. 2018, 41, 417–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, L.R.; Lawson Handley, L.; Carpenter, A.I.; Ghazali, M.; Di Muri, C.; Macgregor, C.J.; Logan, T.W.; Law, A.; Breithaupt, T.; Read, D.S.; et al. Environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding of pond water as a tool to survey conservation and management priority mammals. Biol. Conserv. 2019, 238, 108225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Dubey, V.K.; Choudhury, S.; Das, A.; Jeengar, D.; Sujatha, B.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, N.; Semwal, A.; Kumar, V. Insects as bioindicator: A hidden gem for environmental monitoring. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1146052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, T.K.; Rawtani, D.; Agrawal, Y.K. Bioindicators: The natural indicator of environmental pollution. Front. Life Sci. 2016, 9, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaegashi, S.; Watanabe, K.; Monaghan, M.T.; Omura, T. Fine-scale dispersal in a stream caddisfly inferred from spatial autocorrelation of microsatellite markers. Freshw. Sci. 2014, 33, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okwuosa, O.B.; Eyo, J.E.; Omovwohwovie, E.E. Role of fish as bioindicators: A Review. Iconic Res. Eng. J. 2019, 2, 1456–8880. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, G.; Nakajima, H.; Suzuki, K.; Kanzawa, Y.; Nakayasu, C.; Taguchi, K.; Kurata, O.; Sano, M. Decreased resistance to bacterial cold-water disease and excessive inflammatory response in ayu (Plecoglossus altivelis) reared at high water temperature. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1101491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, K.; Yajima, H.; Islam, M.T.; Pan, S. Assessment of spawning habitat suitability for Amphidromous Ayu (Plecoglossus altivelis) in tidal Asahi River sections in Japan: Implications for conservation and restoration. Riv. Res. Appl. 2024, 40, 1497–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thamsenanupap, P.; Seetapan, K.; Prommi, T. Caddisflies (trichoptera, insecta) as bioindicator of water quality assessment in a small stream in northern Thailand. Sains Malays. 2021, 50, 655–665. [Google Scholar]

- Wityi, H. Applicability of Stenopsyche (Trichoptera: Stenopsychidae) Species as an Indicator in Environmental Monitoring. Ph.D. Thesis, Saitama University, Saitama, Japan, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kocharina, S.L. Growth and production of filter-feeding caddis fly (Trichoptera) larvae in a foothill stream in the Soviet far East. Aquat. Insects 1989, 11, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritschie, K.J.; Olden, J.D. Disentangling the influences of mean body size and size structure on ecosystem functioning: An example of nutrient recycling by a non-native crayfish. Ecol. Evol. 2016, 6, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Qing, Z.; Lin, S. The impact of environment situation on fireflies and the contribution of fireflies on environment situation. Theor. Nat. Sci. 2023, 4, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanaka, H.; Minamoto, T. The use of environmental DNA of fishes as an efficient method of determining habitat connectivity. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 62, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, R.; Nakao, K.; Hiraishi, Y.; Tsuri, K.; Yamanaka, H.; Yuma, M.; Maruyama, A. Detection and quantitative possibility of firefly larvae (Luciola cruciata) using environmental DNA analysis. Ecol. Civil Eng. 2021, 23, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.Q.; Sthapit, N.; Haramoto, E.; Yaegashi, S. Diurnal variations of environmental DNA concentrations originated from Ayu fish Plecoglossus altivelis and macroinvertebrate Stenopsyche marmorata in Bingushi River. J. JSCE 2024, 80, 24–25021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yajima, M. Breeding fireflies at Tama Zoo: An ecological approach. Zool. Gart. 2007, 77, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, M.; Lee, H.; Kim, Y. Relationship between Coliform Bacteria and Water Quality Factors at Weir Stations in the Nakdong River, South Korea. Water 2019, 11, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aram, S.A.; Saalidong, B.M.; Lartey, P.O. Comparative assessment of the relationship between coliform bacteria and water geochemistry in surface and ground water systems. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, E0257715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reischer, G.H.; Kasper, D.C.; Steinborn, R.; Mach, R.L.; Farnleitner, A.H. Quantitative PCR method for sensitive detection of ruminant fecal pollution in freshwater and evaluation of this method in alpine karstic regions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 5610–5614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mieszkin, S.; Furet, J.P.; Corthier, G.; Gourmelon, M. Estimation of pig fecal contamination in a river catchment by real-time PCR using two Pig-Specific Bacteroidales 16S rRNA genetic markers. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 3045–3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kildare, B.J.; Leutenegger, C.M.; McSwain, B.S.; Bambic, D.G.; Rajal, V.B.; Wuertz, S. 16S rRNA-based assays for quantitative detection of universal, human-, cow-, and dog-specific fecal Bacteroidales: A Bayesian approach. Water Res. 2007, 41, 3701–3715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inui, R.; Akamatsu, Y.; Kono, T.; Saito, M.; Miyazono, S.; Nakao, R. Spatiotemporal changes of the environmental DNA concentrations of amphidromous fish Plecoglossus altivelis altivelis in the spawning grounds in the Takatsu River, Western Japan. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9, 622149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherardi, F.; Barbaresi, S.; Salvi, G. Spatial and temporal patterns in the movement of Procambarus clarkii, an invasive crayfish. Aquat. Sci. 2000, 62, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, S.; Traunspurger, W. Invasive red swamp crayfish (Procambarus clarkii) and native noble crayfish (Astacus astacus) similarly reduce oligochaetes, epipelic algae, and meiofauna biomass: A microcosm study. Freshw. Sci. 2017, 36, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuragi, M.; Igota, H.; Uni, H.; Kaji, K.; Kaneko, M.; Akamatsu, R.; Maekawa, K. Comparison of diurnal and 24-hour sampling of habitat use by female sika deer. Mammal Study 2002, 27, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, T.; Takahashi, H.; Yoshida, T.; Igota, H.; Matsuura, Y.; Takeshita, K.; Kaji, K. Seasonal variation of activity pattern in sika deer (Cervus nippon) as assessed by camera trap survey. Mammal Study 2015, 40, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicosia, G.; de Miguel, A.; Fumagalli, A.; Diego-Arnaldo, R.B.; Gürtler, R.E. Influence of COVID-19 lockdown and hunting disturbance on the activity patterns of exotic wild boar (Sus scrofa) and axis deer (Axis axis) in a protected area of northeastern Argentina. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2023, 69, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.R.; Sigsgaard, E.E.; Ávila, M.d.P.; Agersnap, S.; Brenner-Larsen, W.; Sengupta, M.E.; Xing, Y.; Krag, M.A.; Knudsen, S.W.; Carl, H.; et al. Short-term temporal variation of coastal marine eDNA. Environ. DNA 2022, 4, 747–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persaud, S.F.; Cottenie, K.; Gleason, J.E. Ethanol eDNA Reveals Unique Community Composition of Aquatic Macroinvertebrates Compared to Bulk Tissue Metabarcoding in a Biomonitoring Sampling Scheme. Diversity 2021, 13, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdier, H.; Konecny-Dupre, L.; Marquette, C.; Reveron, H.; Tadier, S.; Grémillard, L.; Barthès, A.; Datry, T.; Bouchez, A.; Lefébure, T. Passive sampling of environmental DNA in aquatic environments using 3D-printed hydroxyapatite samplers. Mol. Ecol. Res. 2022, 22, 2158–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamoroff, C.; Goldberg, C.S. An issue of life or death: Using eDNA to detect viable individuals in wilderness restoration. Freshw. Sci. 2018, 37, 685–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muha, T.P.; Robinson, C.V.; Garcia, D.L.C.; Consuegra, S. An optimised eDNA protocol for detecting fish in lentic and lotic freshwaters using a small water volume. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, E0219218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, A.; Kumar, N.; Singh, C.P.; Singh, M. Environmental DNA (eDNA): Powerful technique for biodiversity conservation. J. Nat. Conserv. 2022, 71, 126325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QGIS.org. QGIS Geographic Information System. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project. 2025. Available online: http://qgis.org (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Ogata, S.; Doi, H.; Igawa, T.; Komaki, S.; Takahara, T. Environmental DNA methods for detecting two invasive alien species (American bullfrog and red swamp crayfish) in Japanese ponds. Ecol. Res. 2022, 37, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaegashi, S.; Watanabe, K.; Monaghan, M.T.; Omura, T. Genetic structure and gene flow between altitudinally isolated populations of Stenopysche marmorata. In Proceedings of the 12th International Symposium of Ecohydraulics (ISE 2018), Tokyo, Japan, 19–24 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.S.; Lee, J. Evaluation of new gyrB-based real-time PCR system for the detection of B. fragilis as an indicator of human-specific fecal contamination. J. Microbiol. Methods 2010, 82, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaclı’kova’, E.; Pangallo, D.; Oravcova, K.; Drahovska’, H.; Kutcha, T. Quantification of Escherichia coli by kinetic 5′-nuclease polymerase chain reaction (real-time PCR) oriented to sfmD gene. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2005, 41, 132–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 27 December 2025).

- Turner, C.R.; Barnes, M.A.; Xu, C.C.Y.; Jones, S.E.; Jerde, C.L.; Lodge, D.M. Particle size distribution and optimal capture of aqueous macrobial eDNA. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2014, 5, 676–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majaneva, M.; Diserud, O.H.; Eagle, S.H.C.; Boström, E.; Hajibabaei, M.; Ekrem, T. Environmental DNA filtration techniques affect recovered biodiversity. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichmiller, J.J.; Miller, L.M.; Sorensen, P.W. Optimizing techniques to capture and extract environmental DNA for detection and quantification of fish. Mol. Ecol. Res. 2016, 16, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Z.; Keeley, A. Filtration Recovery of Extracellular DNA from Environmental Water Samples. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 9324–9331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Tan, J.; Wang, M.; Xin, N.; Qi, R.; Wang, H. Optimization of pore size and filter material for better enrichment of environmental DNA. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1422269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Kong, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, J.; Yao, M. Comparative evaluation of common materials as passive samplers of environmental DNA. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 10798–10807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haramoto, E.; Osada, R. Assessment and application of host-specific Bacteroidales genetic markers for microbial source tracking of river water in Japan. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e207727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malla, B.; Yamamoto, K.; Furukawa, K.; Haramoto, E. Performance evaluation and application of host-specific Bacteroidales and mitochondrial DNA markers to identify sources of fecal contamination in river water in Japan. PLoS Water 2024, 3, e0000210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorp, J.H.; Rogers, D.C. (Eds.) Chapter 25—Caddisflies: Insect Order Trichoptera. In Field Guide to Freshwater Invertebrates of North America; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011; pp. 219–227. [Google Scholar]

- Bonada, N.; Prat, N.; Resh, V.H.; Statzner, B. Developments in aquatic insect biomonitoring: A comparative analysis of recent approaches. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2006, 51, 495–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basaguren, A.; Orive, E. The relationship between water quality and caddisfly assemblage structure in fast-running rivers, the River Cadagua Basin. Environ. Monit. Assess. 1990, 15, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standring, S.; Heckenhauer, J.; Stewart, R.J.; Frandsen, P.B. Unraveling the genetics of underwater caddisfly silk. Trends Genet. 2025, 41, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatano, T.; Nagashima, T. The secretion process of liquid silk with nanopillar structures from Stenopsyche marmorata (Trichoptera: Stenopsychidae). Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 9237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumada, N.; Arima, T.; Tsuboi, J.I.; Ashizawa, A.; Fujioka, M. The multi-scale aggregative response of cormorants to the mass stocking of fish in rivers. Fish. Res. 2013, 137, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, A.; Iijima, T.; Kakuzen, W.; Watanabe, S.; Yamada, Y.; Okamura, A.; Horie, N.; Mikawa, N.; Miller, M.J.; Kojima, T.; et al. Release of eDNA by different life history stages and during spawning activities of laboratory-reared Japanese eels for interpretation of oceanic survey data. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shogren, A.J.; Tank, J.L.; Andruszkiewicz, E.; Olds, B.; Mahon, A.R.; Jerde, C.L.; Bolster, D. Controls on eDNA movement in streams: Transport, retention, and resuspension. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Yamamoto, Y.; Yamaguchi, S.; Minamoto, T. Spatiotemporal changes in environmental DNA concentrations caused by fish spawning activity. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 142, 109213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillotson, M.D.; Kelly, R.P.; Duda, J.J.; Hoy, M.; Kralj, J.; Quinn, T.P. Concentrations of environmental DNA (eDNA) reflect spawning salmon abundance at fine spatial and temporal scales. Biol. Conserv. 2018, 220, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeckle, B.C.; Beggel, S.; Cerwenka, A.F.; Motivans, E.; Kuehn, R.; Geist, J. A systematic approach to evaluate the influence of environmental conditions on eDNA detection success in aquatic ecosystems. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e189119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichmiller, J.J.; Bajer, P.G.; Sorensen, P.W. The relationship between the distribution of common carp and their environmental DNA in a small lake. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, E.; Åström, J.; Pettersson, T.J.R.; Bergstedt, O.; Hermansson, M. Decay of Bacteroidales genetic markers in relation to traditional fecal indicators for water quality modeling of drinking water sources. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 46, 892–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, A.; Layton, A.C.; McKay, L.; Williams, D.; Gentry, R.; Sayler, G.S. Factors influencing the persistence of fecal Bacteroides in stream water. J. Environ. Qual. 2009, 38, 1224–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okabe, S.; Shimazu, Y. Persistence of host-specific Bacteroides–Prevotella 16S rRNA genetic markers in environmental waters: Effects of temperature and salinity. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 76, 935–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raya, S.; Malla, B.; Thakali, O.; Angga, M.S.; Segawa, T.; Sherchand, J.B.; Haramoto, E. Validation and application of high-throughput quantitative PCR for the simultaneous detection of microbial source tracking markers in environmental water. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 940, 173604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample (No. of Tested Samples) | Pore Size | No. of Positive Samples (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | MST Markers | Bioindicators | |||||||

| sfmD (%) | BacR (%) | Pig2Bac (%) | gyrB (%) | Pcla (%) | Lcr2 (%) | Sma (%) | Paa (%) | ||

| Omo River (n = 13) | 1.0 μm | 12 (92) | 12 (92) | 3 (23) | 11 (85) | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | 12 (92) | 12 (92) |

| 0.65 μm | 13 (100) | 13 (100) | 5 (38) | 10 (77) | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | 12 (92) | 13 (100) | |

| 0.22 μm | 13 (100) | 13 (100) | 3 (23) | 12 (92) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 13 (100) | 13 (100) | |

| Bingushi River (n = 13) | 1.0 μm | 12 (92) | 13 (100) | 11 (85) | 4 (31) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (15) * | 13 (100) * |

| 0.65 μm | 11 (85) | 13 (100) | 13 (100) | 3 (23) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (31) * | 13 (100) * | |

| 0.22 μm | 12 (92) | 13 (100) | 13 (100) | 3 (23) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (38) * | 13 (100) * | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sthapit, N.; Xu, Y.; Siri, Y.; Haramoto, E.; Yaegashi, S. Temporal Variability of Bioindicators and Microbial Source-Tracking Markers over 24 Hours in River Water. Water 2026, 18, 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010132

Sthapit N, Xu Y, Siri Y, Haramoto E, Yaegashi S. Temporal Variability of Bioindicators and Microbial Source-Tracking Markers over 24 Hours in River Water. Water. 2026; 18(1):132. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010132

Chicago/Turabian StyleSthapit, Niva, Yuquan Xu, Yadpiroon Siri, Eiji Haramoto, and Sakiko Yaegashi. 2026. "Temporal Variability of Bioindicators and Microbial Source-Tracking Markers over 24 Hours in River Water" Water 18, no. 1: 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010132

APA StyleSthapit, N., Xu, Y., Siri, Y., Haramoto, E., & Yaegashi, S. (2026). Temporal Variability of Bioindicators and Microbial Source-Tracking Markers over 24 Hours in River Water. Water, 18(1), 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010132