Abstract

Irrigation effects on processing tomato have been comprehensively studied, whereas the integrated effects of irrigation and agronomic measures lack systematic investigations. This study employed a two-year field experiment to investigate the interactive effects of irrigation, fertilizer, and tillage practices on the crop growth, total yield, and fruit quality of processing tomato. The experimental treatments comprised three irrigation levels (full irrigation, mild water deficit, and moderate water deficit), combined with two fertilizer strategies (synthetic fertilizer only and partial substitution of synthetic fertilizer with manure), and two tillage practices (ridge planting and flat planting). It was found that the partial organic fertilizer substitution and the ridge planting significantly improved the total tomato yield by 13.11% and 75.54% on average, respectively, compared to the synthetic fertilizer application and flat planting, although they led to more salt accumulation in the top soil layer. However, the extent of the increase greatly varied over different irrigation levels and years. The mild water deficit led to a yield increase of 9.22% compared to full irrigation, while the moderate water deficit resulted in an obvious yield loss of 25.95%. Moreover, the ridge planting, the partial organic fertilizer substitution, and water deficit had strong positive effects on the fruit quality and the tillage–irrigation interaction had strong effects on the fruit quality, but it showed negligible effects on the tomato yield. In contrast, the tomato yield was very sensitive to the fertilizer–irrigation interaction, while the fruit quality showed nonsignificant sensitivity to the tillage–irrigation interaction. Finally, the combination of ridge planting, partial organic fertilizer substitution, and a mild water deficit was highlighted as a sustainable cropping production system for processing tomato to achieve an enhanced total yield and fruit quality.

1. Introduction

Tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum L.) are well-known for their rich nutrients and antioxidants such as lycopene, phenolic, and vitamin C, and they are widely consumed worldwide as fresh or processed food products [1,2]. China is one of the largest producers and exporters of processing tomatoes in the world, with a production of 11.0 million tones harvested from about 107,000 hectares in 2024, accounting for 23.3% of the world’s total production [3,4].

The growth of a processing tomato requires a high nitrogen and water supply. Numerous studies have demonstrated that both the yield and quality of processing tomato are strongly influenced by the amount of irrigation water [5,6,7,8], and a regulated water deficit during water-insensitive stages can improve fruit quality without compromising yield [9,10,11]. For example, a meta-analysis indicated that early water stress did not significantly reduce yield but instead increased the soluble solids content and vitamin C content of processing tomato [12]. Nitrogen application is another important factor for tomato growth and yield maintenance. The previous literature has reported that proper nitrogen management had varying positive effects on both tomato yield and fruit quality due to differences in experimental sites, average annual temperature, soil textures, and irrigation amounts [13,14,15]. In terms of tomato quality, a nitrogen supply above the optical nitrogen rate could significantly decrease the lycopene and Vitamin C [13,15], while nitrogen reduction had a non-significant influence on the fruit quality compared with that of the water effects for a greenhouse tomato [16]. Since long-term application of synthetic fertilizers may lead to problems such as soil compaction, acidification, and fertility decline, partial substitution of mineral fertilizers with organic alternatives is widely seen as a clean and sustainable technology for agriculture production [17]. Many studies have indicated that the application of organic fertilizer can enhance soil’s water retention capacity, organic matter, and particle stability, thereby promoting crop growth and increasing crop yield [18,19,20,21]. Compared to irrigation and nitrogen application, which directly affect crop growth, tillage practices influence the crop yield and fruit quality by altering the movement and vertical distribution of water, salts, and nutrients in the root zone. Ridge planting is one of the important tillage practices which could enhance the crop yield and crop water productivity [4]. In the literature, the interactions among multi-factors (i.e., irrigation, fertilizer, and tillage) have been discussed for staple crops (e.g., wheat, maize, and soybeans) [22,23,24,25]. However, for the processing tomato, a high-value economic crop, the integrated effects of irrigation and agronomic measures lack systematic investigations.

In this study, a two-year field experiment on the processing tomato was conducted in the Hetao Irrigation District (HID) of China (as shown in Figure 1), considering three factors at the same time: namely, irrigation, fertilization, and tillage practices. The HID is located in the arid and semi-arid regions of Northwestern China, in which water scarcity and soil salinization have greatly constrained local agricultural production [26,27]. Therefore, improving the yield and fruit quality of processing tomatoes through the integrated regulation of irrigation and agronomic practices is particularly essential for local farmers in the HID. The objectives of this study are as follows: (i) to investigate the effects of a water deficit, organic fertilization addition, and ridge planting on soil water–nitrogen–salt redistribution, crop growth, total yield, and fruit quality for the processing tomato under surface irrigation; (ii) to evaluate the interaction effects between irrigation and agronomic measures on tomato yield and fruit quality; and (iii) to propose a proper strategy for field management of the processing tomato in the HID, which is not only environment-friendly and sustainable for local development, but also can achieve great compromise between tomato yield and quality.

Figure 1.

Processing tomato production system in the Hetao Irrigation District of China.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site and Design

A two-year field experiment (2022–2023) was conducted during the processing tomato growing season (May–August) at the Hetao Experimental Station of China Agricultural University, situated in Inner Mongolia (40°44′ N, 107°17′ E). The experimental site experiences a semi-arid to arid continental climate, with mean temperatures of 25.0 °C and 25.1 °C and cumulative precipitation of 106.0 mm and 93.2 mm during the 2022 and 2023 growing seasons [26,28], respectively. The soil at the experimental site was sandy loam, with a pH of 8.52 and organic matter content of 7.78 g/kg in the 0–60 cm soil. Details about the soil properties can be found in Table S1.

Three regimes for surface irrigation were implemented: full irrigation (W0), mild deficit irrigation (W1), and moderate deficit irrigation (W2). The irrigation quota for the full irrigation was determined to replenish the crop root zone back to field capacity, while the irrigation quotas for mild deficit irrigation and moderate deficit irrigation were reduced by 20% and 40%, respectively. The timing for all irrigation events was determined by the soil moisture in the full irrigation treatment with the flat planting treatment, which was activated whenever the average soil moisture decreased to 70 ± 2% of the field capacity. Two nitrogen application strategies were considered: synthetic fertilizer only (F0) and partial substitution of synthetic fertilizer with organic fertilizer (F1). All treatments received equal applications of total nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium at rates of 300 kg N ha−1, 240 kg P2O5 ha−1, and 375 kg K2O ha−1, respectively. In the synthetic-fertilizer-only treatment, 2/3 of the urea (200 kg N ha−1) and all phosphorus and potassium fertilizer were distributed over the soil surface as a base fertilizer prior to plowing with a rotary spader to 20 cm deep. In the organic fertilizer treatment, half of the synthetic fertilizer (150 kg N ha−1) was substituted by well-rotted sheep manure (75 t ha−1, ~2% N). In this treatment, all organic fertilizer and 1/3 of the urea (50 kg N ha−1) were included in the base fertilizer. For all treatments, the remaining urea (100 kg N ha−1) was applied in two equal splits as a top-dressing fertilizer preceding irrigation at the flowering and fruiting stages, respectively. Two tillage methods were employed: conventional flat planting (T0) and ridge planting (T1), as shown in Figure S1. The flat planting adopted a wide–narrow row pattern with a width of 100 cm for wide rows and 40 cm for narrow rows. The ridge planting consisted of raised beds with a top width of 60 cm, a height of 20 cm, and a center-to-center spacing of 80 cm. To enhance the soil moisture retention and regulate the temperature, black plastic mulch was applied to the narrow rows in flat planting and the raised beds in ridge planting. Finally, nine treatments (as shown in Table 1) were obtained without combinations involving T0 and F0 across all irrigation levels, which have not been adopted by local farmers due to a low tomato yield.

Table 1.

Descriptions of the treatments combining irrigation amount, fertilizer type, and tillage practice.

The study employed “Tunhe No.5”, a widely cultivated processing tomato variety in the region, and the study was implemented using a split-plot design within a randomized complete block framework with three replications. Each experimental plot measured 10 m × 5 m (50 m2) and was surrounded by protective buffer zones to minimize edge effects and ensure the reliability of the results. Tomato seedlings at the 3–4 true leaves stage were transplanted onto mulched beds in dual rows, with a spacing of 40 cm between rows and 50 cm between plants within a row. To ensure crop establishment, all the treatments received an irrigation of 50 mm after transplanting. The total irrigation amounts for full irrigation, mild water deficit, and moderate water deficit treatments were presented in Table S2. Standardized field management practices were maintained across all treatments, including comprehensive weed, pest, and disease control measures.

2.2. Measurements and Data Processing

2.2.1. Soil and Crop Sampling

Soil samples were collected from the top soil layer (0–60 cm) at each growth stage of the processing tomato, and the sampling points were located at 5, 15, 30, and 50 cm in depth. When an irrigation event took place, the soil samples were collected immediately before and three days after irrigation. All soil samples were instantly transported to the laboratory to measure the soil’s water content, salinity, nitrate, and ammonium nitrogen levels. During the tomato growing period, three well-developed and representative tomato plants were randomly selected and tagged for each plot, and their key morphological parameters (i.e., plant height, stem diameter, leaf area, and fruit diameter), were measured at each growth stage. The plant height was measured with a tape measure, while the stem diameter was measured at a height of 3 cm above the soil surface. The leaf area index (LAI) was calculated as the ratio of the total leaf area to the overall plant-covering area. The fruit diameter was measured for the tomatoes in the first cluster by using a digital vernier caliper, and it was calculated by averaging the transverse and longitudinal diameters. Moreover, three representative plants in each plot were randomly selected for destructive sampling, and the dry matter weight of different organs above ground (stems, leaves, flower buds, fruits) were separately recorded using the drying method.

2.2.2. Fruit Yield and Quality

Fruit maturity assessment and quality analysis were conducted when more than 80% of tomatoes reached maturity. To minimize the border effects, five plants in each plot were randomly selected for the yield component measurements, including individual fruit weight, fruit number per plant, and fresh yield. Three representative ripe fruits in each plot were randomly collected for quality determination. The quality indexes included soluble solid content, fruit firmness, vitamin C, soluble sugars, titratable acidity, and lycopene content. The soluble solid content and fruit firmness were measured with a handheld digital refractometer (ATAGO PR-32α) and firmness tester (FHR-5), prior to tissue homogenization. The vitamin C content was determined by the 2,6-dichloroindophenol method, soluble sugars by the Fehling’s reagent method, titratable acidity by the acid-base titration method, and the lycopene content by UV spectrophotometry.

2.3. Data Analysis

Due to the absence of combinations involving flat planting and synthetic fertilizer only across all irrigation levels, the standard three-factorial ANOVA could not be employed to quantify the main effects and interactions of tillage, fertilizer, and irrigation. To address this limitation, a conditional subset analysis strategy was adopted. Specifically, the subset with organic fertilizer application was used to evaluate the tillage’s main effect, tillage × irrigation interaction, and their differences across years. Meanwhile, the subset under ridge planting was utilized to assess the fertilizer’s main effect, fertilizer × irrigation interaction, and their interannual variations. A full data model was implemented to estimate the overall main effect of the irrigation. All statistical analyses were conducted by using R software (version 4.5.2).

3. Results

3.1. Soil’s Water Content, Salt, and Nitrogen

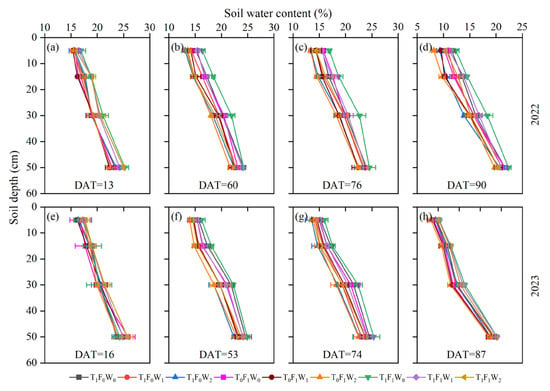

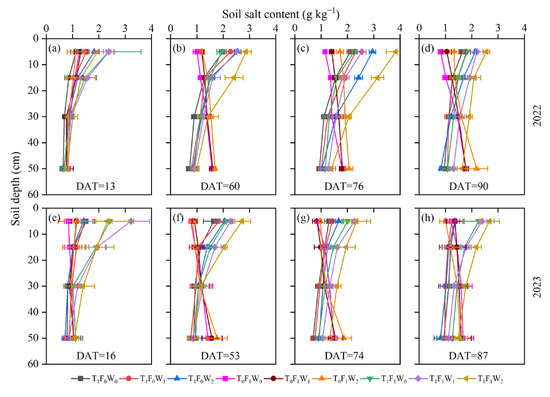

Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 show the dynamics of the soil’s water content, salinity, nitrate, and ammonium nitrogen levels on different days after transplanting (DAT) for processing tomatoes. Figure 2 shows that, under the ridge planting, partial organic fertilizer substitution obviously enhanced the soil water content in a 0–60 cm soil layer across all irrigation levels. Compared to the synthetic-fertilizer-only treatments, the soil’s water content for treatments with organic fertilizer application increased by 1.74~9.25%, 0.42~8.12%, 1.81~12.77%, and 2.30~21.22% at DAT = 13, 60, 76, and 90, respectively. Meanwhile, among the treatments with organic fertilizer application, ridge planting led to higher soil water contents than the flat planting on different observation dates during the growth period. However, Figure 3 shows that, under the ridge planting conditions, the average soil salt content in the 0–30 cm soil layer of treatments with synthetic fertilizer only, under different irrigation levels, were 1.24, 1.34, and 1.51 g·kg−1, respectively, which were obviously lower than the treatments with a partial organic fertilizer substitution (1.63, 1.84, and 2.11 g·kg−1, respectively). Similarly, the soil salt contents of synthetic-fertilizer-only treatments in the 30–60 cm soil layer (0.89, 0.95, and 0.97 g·kg−1, respectively) were also lower than those with partial organic fertilizer substitution (1.08, 1.61, and 1.37 g·kg−1, respectively). By contrast, among the treatments with organic fertilizer application, ridge planting led to more soil salt accumulation in the 0–30 cm soil layer compared to the flat planting, but it obviously alleviated that in the 30–60 cm soil layer. The average soil salt contents of treatments with organic fertilizer application under flat planting in the 0–30 cm soil layer under different irrigation levels were 1.13, 1.21, and 1.24 g·kg−1, respectively, while they were 1.36, 1.36, and 1.46 g·kg−1 in the 30–60 cm soil layer, respectively. Moreover, under the ridge planting, the soil salt content accumulated more in the top 0–10 cm than that in the other soil layers across all irrigation levels.

Figure 2.

Dynamics of soil water content at different days after transplanting (DAT) under various irrigation, fertilizer, and tillage treatments in 2022 (a–d) and 2023 (e–h).

Figure 3.

Dynamics of soil salt content at different days after transplanting (DAT) under various irrigation, fertilizer, and tillage treatments in 2022 (a–d) and 2023 (e–h).

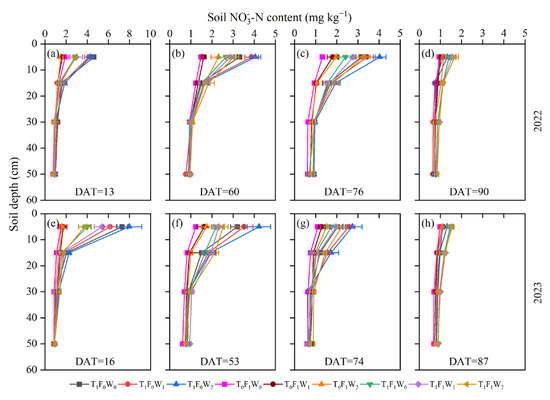

Figure 4.

Dynamics of soil nitrate content on different days after transplanting (DAT) under various irrigation, fertilizer, and tillage treatments in 2022 (a–d) and 2023 (e–h).

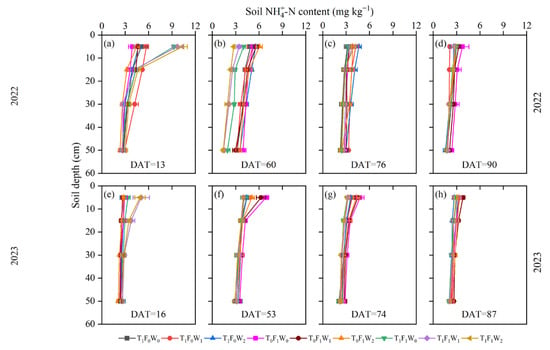

Figure 5.

Dynamics of soil ammonium content on different days after transplanting (DAT) under various irrigation, fertilizer, and tillage treatments in 2022 (a–d) and 2023 (e–h).

Figure 4 shows that the soil’s nitrate content in the 0–30 cm soil layer greatly varied with tillage practices, fertilizer types, and irrigation levels. Meanwhile, obvious variations in the soil ammonium were found in the 0–10 cm soil layer (Figure 5). For the soil nitrate, the treatments combining ridge planting and synthetic fertilizer only had the highest values, while the combinations of ridge planting and partial organic fertilizer substitution had moderate values, and the flat planting treatments had the lowest values across all irrigation levels. However, the differences among the treatments became relatively small at the late fruiting stage (Figure 4d,h), and the treatments combining ridge planting and partial organic fertilizer substitution had a higher soil nitrate content than other treatments. For the soil ammonium, the combinations of ridge planting and organic fertilizer application had obviously higher values than the other treatments at the seedling stage (Figure 5a,e), among which small variations were found. After the seedling stage, the soil’s ammonium content in the treatments under flat planting were relatively higher than that in the other treatments. Additionally, under all conditions of different tillage and fertilizer applications, the soil nitrate content in the 0–30 cm soil layer slightly increased with the reducing irrigation levels, while the soil ammonium in the 0–10 cm soil layer slightly decreased instead.

3.2. Crop Growth, Tomato Yield, and Fruit Quality

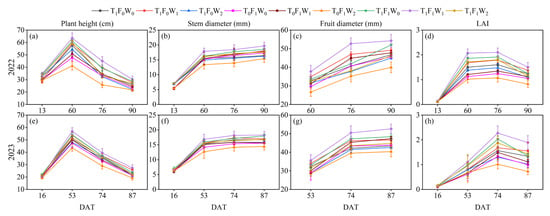

Figure 6 shows that, under the ridge planting, the partial organic fertilizer substitution improved the plant height, stem diameter, fruit diameter, and LAI at the late fruiting stage by 4.87~21.36%, 6.39~12.61%, 2.69~12.84%, and 0.43~40.89%, respectively, compared to the synthetic-fertilizer-only treatments under different irrigation levels. Similarly, under the organic fertilizer conditions, the ridge planting enhanced the above growth parameters by 11.40~23.62%, 7.05~16.88%, 10.33~15.59%, and 17.77~97.39%, respectively, compared to the flat planting treatments. By contrast, under the ridge planting and organic fertilizer condition, the mild water deficit led to increases in growth parameters over two years by 10.39%, 4.06%, 6.52%, and 30.51%, respectively, while a moderate water deficit resulted in decreases of 6.18%, 5.67%, 9.31%, and 0.94%, respectively. Similar irrigation effects were observed under other tillage and fertilizer conditions. Moreover, for the organic fertilizer application under the ridge planting, the mild water deficit had stronger positive effects on the crop growth than the synthetic-fertilizer-only application, and less negative effects were observed in the moderate water deficit condition. Meanwhile, under the organic fertilizer condition, the ridge planting had similar effects with the partial organic fertilizer substitution, but the overall effects were relatively lower in different water deficit conditions.

Figure 6.

Changes in growth parameters (plant height, stem diameter, fruit diameter, and LAI) of processing tomato on different days after transplanting (DAT) under various irrigation, fertilizer, and tillage treatments in 2022 (a–d) and 2023 (e–h).

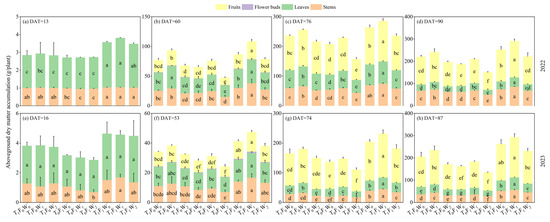

Figure 7 shows that, at the seedling stage, a water deficit had no significant effects on the dry matter weights of leaves and stems, while the fertilizer application and tillage practices had slight influences (Figure 3a,e). After the seedling stage, there were significant differences in the dry matter weights of different organs above ground among different treatments. In particular, at the late fruiting stage, under the ridge planting conditions, the partial organic fertilizer substitution increased the above-ground biomass by 12.71~34.69% compared to the synthetic-fertilizer-only application across different irrigation levels. Meanwhile, under the organic fertilizer condition, the ridge planting obtained an increase of 34.28~71.46% in the aboveground biomass compared to the flat planting. Moreover, among the ridge planting treatments, the mild water deficit under organic fertilizer conditions enhanced the above-ground biomass by 11.81~15.34%, while the moderate water deficit resulted in a decrease of 11.94~12.04%. Similar results to the irrigation effects were obtained under the synthetic-fertilizer-only condition and the flat planting condition.

Figure 7.

Dry matter of aboveground organs of processing tomato on different days after transplanting (DAT) under various irrigation, fertilizer, and tillage treatments in 2022 (a–d) and 2023 (e–h). Different letters on the bars denote significant differences at 0.05 level.

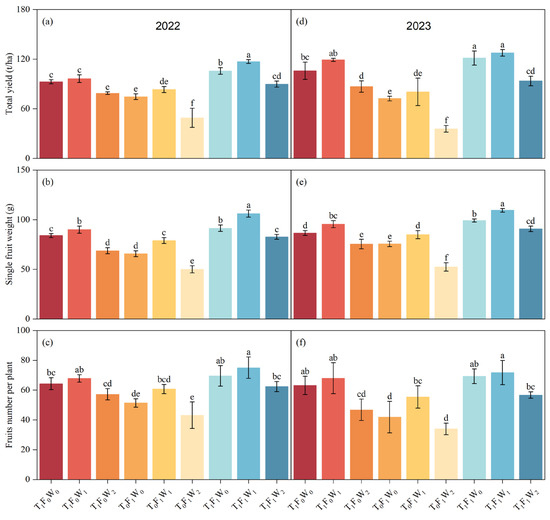

Figure 8 shows that the tomato yield in 2023 was generally higher than that in 2022 under the same treatment. The treatments with the ridge planting and partial organic fertilizer substitution obtained the highest total tomato yield across all irrigation levels, as well as single fruit weights and fruit numbers per plant. Meanwhile, the combinations of the ridge planting and synthetic fertilizer only had moderate results, and the flat planting treatments had the lowest values. Moreover, the total yield and single fruit weight significantly varied with different tillage and fertilizer applications across all irrigation levels, while the variation in the fruit numbers per plant was insignificant. Under ridge planting, the partial organic fertilizer substitution improved the tomato yield, single fruit weight, and fruit numbers per plant by 7.12~21.40%, 8.73~20.39%, and 5.59~21.26%, respectively, compared to the synthetic-fertilizer-only application across all irrigation levels. By contrast, among the treatments with partial organic fertilizer substitution, the ridge planting improved these yield parameters by 40.46~161.90%, 28.86~73.56%, and 23.63~66.99%, respectively, compared to the flat planting condition. The irrigation’s effects on the yield were similar to that of the above-ground biomass. For example, under the ridge planting and the organic fertilizer condition, the mild water deficit increased the yield parameters by 5.09~10.80%, 10.34~16.06%, and 3.66~7.97%, respectively, compared to the full irrigation. Meanwhile, the moderate water deficit led to decreases of 15.04~22.89%, 8.48~9.49%, and 10.27~18.11%, respectively. For the irrigation effects on the above-ground biomass and yield parameters, both the ridge planting and the partial organic fertilizer substitution enhanced the positive effects of the mild water deficit, while they reduced the negative effects of the moderate water deficit.

Figure 8.

Total yield, single fruit weight, and fruit numbers per plant under various irrigation, fertilizer, and tillage treatments in 2022 (a–c) and 2023 (d–f). Different letters on the bars denote significant differences at 0.05 level.

The results of fruit quality, including the soluble solids content, lycopene content, vitamin C content, fruit firmness, soluble sugar content, and titratable acidity of the processing tomato, are illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Effects of different irrigation and agronomic practices on fruit quality of the processing tomato in 2022–2023. Values within columns followed by different letters are statistically significant at the 0.05 level.

Table 2 showed that the fruit quality parameters varied greatly over different treatments. The soluble solid content, lycopene content, vitamin C content, fruit firmness, soluble sugar content, and titratable acidity ranges were 4.67~6.47%, 16.92~35.60 mg/100 g, 11.52~21.17 mg/100 g, 1.67~4.80 kg/cm2, 1.62~3.63%, and 2.21~4.42 g/kg, respectively. Generally, compared to synthetic-fertilizer-only treatments, the partial organic fertilizer substitution exhibited increased in the above fruit quality parameters by 3.19~13.57%, 14.48~47.50%, 10.23~34.72%, 14.81~67.92%, 41.27~68.11%, and 13.85~27.72%, respectively. Meanwhile, the ridge planting practice led to enhancements of these parameters by 1.81~6.01%, 18.62~70.36%, 13.40~35.09%, 14.49~65.52%, −5.22~32.38%, and 7.52~25.03%, respectively, compared to the flat planting treatments. Moreover, the values of the fruit quality parameters were found to increase with the degrees of water deficit. Compared to full irrigation, a mild water deficit exhibited significant increases in the fruit quality parameters by 6.29~8.59%, 5.07~39.69%, 13.87~43.89%, 11.59~43.4%, 11.83~42.86%, and 22.45~38.29%, respectively, under different tillage and fertilizer conditions. By contrast, a moderate water deficit resulted in overall improvements of the fruit quality parameters by 13.21~28.77%, 17.65~63.27%, 23.18~55.93%, 26.09~64.15%, 39.75~86.67%, and 49.32~67.43%, respectively. The positive effects of a water deficit on the fruit quality parameters were relatively reduced by the partial organic fertilizer substitution and the reduced ridge planting practice, compared to the synthetic-fertilizer-only and flat planting practice, respectively.

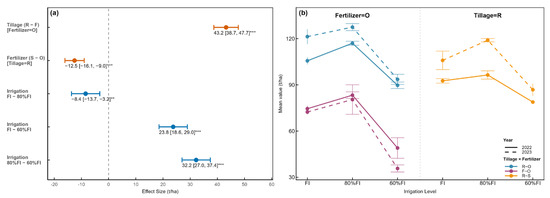

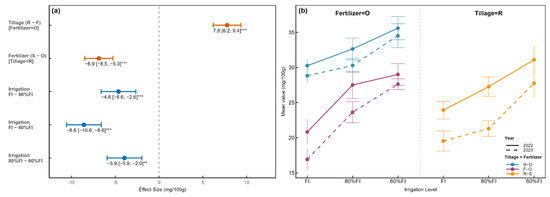

3.3. Interaction Effects Among Irrigation, Fertilization, and Tillage Practices

Figure 9 shows the main conditional effects of tillage, fertilizer, and irrigation and their interactions on the tomato yield. The mean difference with a 95% confidence interval (CI) was used to quantify the main effect size, and asterisks were used to represent significance levels. In Figure 9a, all the main effects were significant at the 0.01 level. The mild water deficit had a significantly positive effect on the tomato yield, but it was lower than that of the ridge planting and partial organic fertilizer substitution. Meanwhile, the moderate water deficit had a strong negative effect on the tomato yield. Under the organic fertilizer conditions, the ridge planting had the strongest positive effect on the tomato yield, while the interaction effects between the tillage and irrigation were relatively small (Figure 9b). Under the ridge planting condition, the partial organic fertilizer substitution had relatively stronger positive effects on the tomato yield than the mild water deficit, but it was lower than the negative effects of the moderate effects. Moreover, Figure 9b shows relatively strong interaction effects between the fertilizer and irrigation.

Figure 9.

Conditional main effects (a) and interaction effects (b) of fertilizer, tillage, and irrigation on the total tomato yield (R, ridge planting; F, flat planting; S, synthetic fertilizer only; O, partial organic fertilizer substitution; ns, insignificance; * significant at 0.05 level; ** significant at 0.01 level; and *** significant at 0.001 level).

Fruit quality stands as a pivotal commodity attribute of cash crops. Among the fruit quality parameters, the soluble solid content and lycopene content serve as crucial quality indicators for the processing tomato. Soluble solids constitute the primary dry matter in processing tomato fruits, making them essential for the processing tomato industry, which prioritizes high dry matter content to minimize energy consumption during water evaporation in pulp preparation [29,30]. Lycopene, on the one hand, imparts the red color required for tomato products, playing a pivotal role in human health. Its antioxidant properties mitigate the risk of diseases stemming from oxidative stress, thereby offering significant health benefits throughout all life stages. Moreover, when combined with other antioxidants, lycopene holds immense potential for further enhancing human health [31]. Therefore, we evaluated the main effects and interaction responses of the three factors on the content of lycopene, soluble solids, and Vitamin C in tomato fruit. Due to space limitations, the result for lycopene was presented in Figure 10, while the results for soluble solids and Vitamin C were shown in Figures S2 and S3. As shown in Figure 10, a water deficit had very strong positive effects on the lycopene content in the tomato fruit, and the effects increased with the extent of the water deficit. Under the organic fertilizer conditions, the ridge planting had a strong positive effect on the lycopene content in the tomato fruit, and the interaction effect between the tillage and irrigation was also very obvious (Figure 10b). Under the ridge planting condition, the partial organic fertilizer substitution also had a strong effect on the lycopene content in the tomato fruit, but the interaction effect between the fertilizer and irrigation was negligible (Figure 10b). Similar results for the soluble solids and Vitamin C were obtained from Figures S2 and S3.

Figure 10.

Conditional main effects (a) and interaction effects (b) of fertilizer, tillage, and irrigation on the lycopene content in the tomato fruit (R, ridge planting; F, flat planting; S, synthetic fertilizer only; O, partial organic fertilizer substitution; ns, insignificance; * significant at 0.05 level; ** significant at 0.01 level; and *** significant at 0.001 level).

4. Discussion

Previous studies have demonstrated that a regulated water deficit can enhance crop growth, total tomato yield, and water-use efficiency (WUE) [11,12,32]. When the water deficit exceeds a certain threshold, crops may experience severe water stress, which negatively impacts crop growth by reducing stomatal conductance and decreasing plant transpiration and photosynthesis [10,33]. However, the extent of the water deficit effects may fluctuate under different agronomic measures of fertilizer application and tillage practices. In our study, under the moderate water deficit condition, the treatment under flat planting was most likely to result in severe yield loss, followed by the treatment combining ridge planting and synthetic-fertilizer-only application, while the treatment using ridge planting with partial organic fertilizer substitution had the best ability to mitigate yield reduction due to water stress. Moreover, across all irrigation levels, the results indicated that both organic fertilizer and ridge planting tillage can obviously enhance the growth of plants and improve the crop yield and fruit quality, which is consistent with the results of previous studies [17,23,34]. The lowest yield of the flat planting treatment is mainly caused by a low nutrient supply in the root-zone soil. The soil’s nitrate content in the 0–30 cm soil layer under the flat planting was relatively lower than other treatments throughout the tomato growth period (Figure 4), while the soil ammonium content in the 0–10 cm soil layer was relatively higher (Figure 5), which increased the risk of nitrogen loss due to ammonia volatilization. By contrast, the positive effects of ridge planting and partial organic fertilizer substitution can be attributed to two reasons. On the one hand, the partial organic fertilizer substitution increases the organic matter content, enzyme activity, and microbial activity in the top soil [20,35,36]. This environment fosters a higher carbon input from plants and the accumulation of organic carbon in the soil [16,37]. The organic manure provides a sustained nutrient supply to plants (Figure 4 and Figure 5), which instantly satisfies their nitrogen demands while substantially reducing the leaching loss of mineral nitrogen [17,20]. Additionally, partial organic fertilizer substitution can substantially enhance crop productivity, primarily by improving the soil structure and soil nutrient availability, and sustaining soil fertility [18,38]. On the other hand, ridge planting practice can enhance the soil’s water storage capacity, thereby benefiting crop growth with improved nutrients and water availability [24,39,40].

It is worth noting that both the ridge planting and the partial organic fertilizer substitution led to more soil salt accumulation in the 0–30 cm soil layer (Figure 3), particularly in the top 0–10 cm of the soil, compared to the flat planting and the synthetic fertilizer only. However, under the ridge planting and organic fertilizer conditions, the enhanced soil water-holding capacity and soil nutrient supply may lead to a salinity dilution effect and maintain yield production [4].

Results indicated that the ridge planting, partial organic fertilizer substitution, and mild water deficit had strong positive effects on the tomato yield and fruit quality, whereas the moderate water deficit had strong negative effects on the tomato yield. Meanwhile, the water deficit’s effects on the fruit quality obviously increased with the reducing irrigation amount. However, the interaction effect between the tillage and irrigation was negligible on the tomato yield, but it was very strong on the fruit quality. On the contrary, the interaction effect between the fertilizer and irrigation was strong on the tomato yield, while it was inconspicuous on the fruit quality. The findings on the water deficit’s effects are consistent with those of previous studies [1,9,11,30,41]. The possible reason is that a decrease in the water content within the fruit leads to reduced fruit volume and dilution of solute concentration, consequently resulting in the accumulation of assimilates and thereby enhancing the quality parameters [7]. The fertilizer effects show some differences to those in the literature. Some studies have demonstrated that the organic fertilizer application had no significant impact on the fruit’s quality parameters, such as titratable acidity, total soluble solid content, and total acidity [42]. Conversely, some studies have reported that the utilization of organic fertilizer could enhance the total soluble solid content and lycopene content in fruits [43], which provides strong support for our results. These discrepancies may have resulted from variations in the type of organic fertilizer and the varieties of processing tomato under investigation.

5. Conclusions

A two-year field experiment indicated that ridge planting and partial organic fertilizer substitution could greatly enhance crop growth, tomato yield, and fruit quality by changing the soil’s hydraulic properties and nutrient redistribution, which benefit crop growth and improve quality. By contrast, flat planting was likely to have poor soil water-holding capacity and an insufficient nutrient supply in the late crop-growing stages, which were unfavorable for crop growth and fruit formation. The mild water deficit comprehensively improved the tomato yield and fruit quality, while the moderate water deficit resulted in a great yield loss, though the fruit quality was further improved. The tomato yield exhibited high sensitivity to the interaction effect between the fertilizer and irrigation, but it showed nonsignificant sensitivity to the interaction effect between the tillage and irrigation. However, the tillage–irrigation interaction has very small effect on the fruit quality, while the fertilizer–irrigation interaction showed a substantial influence. The combination of ridge planting, partial organic fertilizer substitution, and a mild water deficit was suggested as a promising option for widespread adoption in processing tomato cultivation, which was good for meeting the requirements for water conservation, enhancing production, and improving quality.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/w18010123/s1, Figure S1: Design of different tillage practices and irrigation methods; Figure S2: Main effects (a) and interaction effects (b) of fertilizer, tillage, and irrigation on the Vitamin C (VC) content in the tomato fruit (R, Ridge planting; F, Flat planting; S, Synthetic fertilizer only; O, Organic fertilizer addition; ns, insignificance; * significant at 0.05 level; ** significant at 0.01 level; *** significant at 0.001 level.); Figure S3: Main effects (a) and interaction effects (b) of fertilizer, tillage, and irrigation on the Soluble solid content in the tomato fruit (R, Ridge planting; F, Flat planting; S, Synthetic fertilizer only; O, Organic fertilizer addition; ns, insignificance; * significant at 0.05 level; ** significant at 0.01 level; *** significant at 0.001 level.); Table S1: Soil properties at the experimental site (0–60 cm soil layer); Table S2: Irrigation amounts of each treatment at different days after transplanting (DAT).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.Z. and J.T.; methodology, R.Z. and J.T.; software, R.Z.; validation, R.Z., J.T. and Z.H.; formal analysis, R.Z. and J.T.; investigation, R.Z.; resources, J.T. and G.H.; data curation, R.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, R.Z. and J.T.; writing—review and editing, J.T., Z.H. and G.H.; visualization, R.Z. and J.T.; supervision, J.T.; project administration, J.T.; funding acquisition, J.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Key Research Project of Science and Technology in Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region of China (2025YFHH0166, NMKJXM202105, NMKJXM202208).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank everyone who contributed to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lahoz, I.; Perez-De-Castro, A.; Valcarcel, M.; Macua, J.I.; Beltran, J.; Rosello, S.; Cebolla-Cornejo, J. Effect of water deficit on the agronomical performance and quality of processing tomato. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 200, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.Y.; Chen, R.; Wen, Y.; Zhang, J.Z.; Yin, F.H.; Javed, T.; Zheng, J.L.; Wang, Z.H. Processing tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Miller) yield and quality in arid regions through micro-nano aerated drip irrigation coupled with humic acid application. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 308, 109317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.Y.; Ren, Q.; Xie, Q.; Tan, J.W.; Huang, G.H. Spatial and temporal variability of irrigation water demand of processing tomato in the Northwest Arid Region of China. J. Irri. Drain. 2024, 43, 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, R.Y.; Tan, J.W.; Huo, Z.L.; Huang, G.H. Effects of Ridge Planting on the Distribution of SoilWater-Salt-Nitrogen, Crop Growth, and Water Use Efficiency of Processing Tomatoes Under Different Irrigation Amounts. Water 2025, 17, 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghannem, A.; Ben Aissa, I.; Majdoub, R. Effects of regulated deficit irrigation applied at different growth stages of greenhouse grown tomato on substrate moisture, yield, fruit quality, and physiological traits. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 46553–46564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusçu, H.; Turhan, A.; Demir, A.O. The response of processing tomato to deficit irrigation at various phenological stages in a sub-humid environment. Agric. Water Manag. 2014, 133, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nangare, D.D.; Singh, Y.; Kumar, P.S.; Minhas, P.S. Growth, fruit yield and quality of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) as affected by deficit irrigation regulated on phenological basis. Agric. Water Manag. 2016, 171, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.H.; Huang, G.H.; Jia, D.D.; Wang, J.; Mota, M.; Pereira, L.S.; Huang, Q.Z.; Xu, X.; Liu, H.J. Responses of drip irrigated tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) yield, quality and water productivity to various soil matric potential thresholds in an arid region of Northwest China. Agric. Water Manag. 2013, 129, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.T.; Shao, G.C.; Lu, J.; Keabetswe, L.; Hoogenboom, G. Yield, quality and drought sensitivity of tomato to water deficit during different growth stages. Sci. Agric. 2020, 77, e20180390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinkora, M.; Fanciullino, A.-L.; Page, D.; Giovinazzo, R.; Lanoe, L.; Boas, A.V.; Bertin, N. Tomato puree quality from field to can: Effects of water and nitrogen-saving strategies. Eur. J. Agron. 2023, 149, 126891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.M.; Xiong, Y.W.; Huang, G.H.; Xu, X.; Huang, Q.Z. Effects of water stress on processing tomatoes yield, quality and water use efficiency with plastic mulched drip irrigation in sandy soil of the Hetao Irrigation District. Agric. Water Manag. 2017, 179, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Shao, G.C.; Cui, J.T.; Wang, X.J.; Keabetswe, L. Yield, fruit quality and water use efficiency of tomato for processing under regulated deficit irrigation: A meta-analysis. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 222, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pascale, S.; Maggio, A.; Orsini, F.; Barbieri, G. Cultivar, soil type, nitrogen source and irrigation regime as quality determinants of organically grown tomatoes. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 199, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.H.; Wang, H.D.; Fan, J.L.; Xiang, Y.Z.; Tang, Z.J.; Pei, S.Z.; Zeng, H.L.; Zhang, C.; Dai, Y.L.; Li, Z.J.; et al. Effects of nitrogen supply on tomato yield, water use efficiency and fruit quality: A global meta-analysis. Sci. Hortic. 2021, 290, 110553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.H.; Liu, H.; Gong, X.W.; Li, S.; Pang, J.; Chen, Z.F.; Sun, J.S. Optimizing irrigation and nitrogen management strategy to trade off yield, crop water productivity, nitrogen use efficiency and fruit quality of greenhouse grown tomato. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 245, 106570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.X.; Gu, F.; Chen, J.L.; Yang, H.; Jiang, J.J.; Du, T.S.; Zhang, J.H. Assessing the response of yield and comprehensive fruit quality of tomato grown in greenhouse to deficit irrigation and nitrogen application strategies. Agric. Water Manag. 2015, 161, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.; Zhou, J.; Yang, X.; Jin, T.; Zhao, B.Q.; Li, L.L.; Wen, Y.C.; Soldatova, E.; Zamanian, K.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; et al. Long-term organic fertilizer-induced carbonate neoformation increases carbon sequestration in soil. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, F.L.; Sun, N.; Misselbrook, T.; Wu, L.H.; Xu, M.G.; Zhang, F.S.; Xu, W. Responses of crop productivity and reactive nitrogen losses to the application of animal manure to China’s main crops: A meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 850, 158064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.; Yang, S.; Luan, C.S.; Wu, Q.; Lin, L.L.; Li, X.X.; Che, Z.; Zhou, D.B.; Dong, Z.R.; Song, H. Partial organic substitution for synthetic fertilizer improves soil fertility and crop yields while mitigating N2O emissions in wheat-maize rotation system. Eur. J. Agron. 2023, 154, 127077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.Z.; Song, J.J.; Chen, D.Y.; Zhang, Z.H.; Yu, Q.; Ren, G.X.; Han, X.H.; Wang, X.J.; Ren, C.J.; Yang, G.H.; et al. Biochar combined with N fertilization and straw return in wheat-maize agroecosystem: Key practices to enhance crop yields and minimize carbon and nitrogen footprints. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 347, 108366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, R.; Zhou, J.; Chu, J.C.; Shahbaz, M.; Yang, Y.D.; Jones, D.L.; Zang, H.D.; Razavi, B.S.; Zeng, Z.H. Insights into the associations between soil quality and ecosystem multifunctionality driven by fertilization management: A case study from the North China Plain. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 362, 132265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajanna, G.A.; Dass, A.; Suman, A.; Babu, S.; Venkatesh, P.; Singh, V.K.; Upadhyay, P.K.; Sudhishri, S. Co-implementation of tillage, irrigation, and fertilizers in soybean: Impact on crop productivity, soil moisture, and soil microbial dynamics. Field Crops Res. 2022, 288, 108672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajanna, G.A.; Dass, A.; Singh, V.K.; Choudhary, A.K.; Paramesh, V.; Babu, S.; Upadhyay, P.K.; Sannagoudar, M.S.; Ajay, B.C.; Viswanatha Reddy, K. Energy and carbon budgeting in a soybean–wheat system in different tillage, irrigation and fertilizer management practices in South-Asian semi-arid agroecology. Eur. J. Agron. 2023, 148, 126877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, D.H.; Liu, S.J.; Wen, X.X.; Han, J.; Liao, Y.C. Quantifying the impacts of agricultural management practices on the water use efficiency for sustainable production in the Loess Plateau region: A meta-analysis. Field Crops Res. 2023, 291, 108787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, K.P.; Liao, P.; Xu, Q. Effect of agricultural management practices on rice yield and greenhouse gas emissions in the rice-wheat rotation system in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 916, 170307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, D.Y.; Xu, X.; Hao, Y.Y.; Huang, G.H. Modeling and assessing field irrigation water use in a canal system of Hetao, upper Yellow River basin: Application to maize, sunflower and watermelon. J. Hydrol. 2016, 532, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Herbst, M.; Chen, Z.J.; Chen, X.G.; Xu, X.; Xiong, Y.W.; Huang, Q.Z.; Huang, G.H. Long term response and adaptation of farmland water, carbon and nitrogen balances to climate change in arid to semi-arid regions. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 364, 108882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.J.; Xiong, Y.W.; Cui, Z.; Huang, Q.Z.; Xu, X.; Han, W.G.; Huang, G.H. Effect of irrigation and fertilization regimes on grain yield, water and nitrogen productivity of mulching cultivated maize (Zea mays L.) in the Hetao Irrigation District of China. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 232, 106065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favati, F.; Lovelli, S.; Galgano, F.; Miccolis, V.; Di Tommaso, T.; Candido, V. Processing tomato quality as affected by irrigation scheduling. Sci. Hortic. 2009, 122, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takacs, S.; Pek, Z.; Csanyi, D.; Daood, H.G.; Szuvandzsiev, P.; Palotas, G.; Helyes, L. Influence of water stress levels on the yield and lycopene content of tomato. Water 2020, 12, 2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caseiro, M.; Ascenso, A.; Costa, A.; Creagh-Flynn, J.; Johnson, M.; Simoes, S. Lycopene in human health. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 127, 109323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.K.; Yun, J.; Shi, P.; Li, Z.B.; Li, P.; Xing, Y.Y. Root growth, fruit yield and water use efficiency of greenhouse grown tomato under different irrigation regimes and nitrogen levels. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2019, 38, 400–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.Y.; Zhang, T.; Jiang, W.T.; Li, P.; Shi, P.; Xu, G.; Cheng, S.D.; Cheng, Y.T.; Fan, Z.; Wang, X.K. Effects of irrigation and fertilization on different potato varieties growth, yield and resources use efficiency in the Northwest China. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 261, 107351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, L.C.; Wang, Z.B.; Zhai, Y.C.; Zhang, L.H.; Zheng, M.J.; Yao, H.P.; Lv, L.H.; Shen, H.P.; Zhang, J.T.; Yao, Y.R.; et al. Partial substitution of chemical fertilizer by organic fertilizer benefits grain yield, water use efficiency, and economic return of summer maize. Soil Till. Res. 2021, 217, 105287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.H.; Dong, C.; Bian, W.P.; Zhang, W.B.; Wang, Y. Effects of different fertilization practices on maize yield, soil nutrients, soil moisture, and water use efficiency in northern China based on a meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaswar, M.; Huang, J.; Ahmed, W.; Li, D.S.; Liu, S.J.; Zhang, L.; Cai, A.D.; Liu, L.S.; Xu, Y.M.; Gao, J.S.; et al. Yield sustainability, soil organic carbon sequestration and nutrients balance under long-term combined application of manure and inorganic fertilizers in acidic paddy soil. Soil Till. Res. 2020, 198, 104569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.B.; Wang, J.Y.; Pu, S.Y.; Blagodatskaya, E.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Razavi, B.S. Impact of manure on soil biochemical properties: A global synthesis. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 745, 141003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.Y.; Turner, N.C.; Gong, Y.H.; Li, F.M.; Fang, C.; Ge, L.J.; Ye, J.S. Benefits and limitations to straw- and plastic-film mulch on maize yield and water use efficiency: A meta-analysis across hydrothermal gradients. Eur. J. Agron. 2018, 99, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Song, X.Y.; Li, F.C.; Hu, G.R.; Liu, Q.L.; Zhang, E.H.; Wang, H.L.; Davies, R. Optimum ridge-furrow ratio and suitable ridge-mulching material for Alfalfa production in rainwater harvesting in semi-arid regions of China. Field Crops Res. 2015, 180, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.Q.; Li, J.; Yang, Z.Y.; Yang, T.; Li, H.T.; Wang, X.F.; Peng, Y.; Zhou, C.J.; Wang, L.Q.; Abdo, A.I. The field mulching could improve sustainability of spring maize production on the Loess Plateau. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 279, 108156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valcarcel, M.; Lahoz, I.; Campillo, C.; Marti, R.; Leiva-Brondo, M.; Rosello, S.; Cebolla-Cornejo, J. Controlled deficit irrigation as a water-saving strategy for processing tomato. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 261, 108972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenbach, L.D.; Folina, A.; Zisi, C.; Roussis, I.; Tabaxi, I.; Papastylianou, P.; Kakabouki, I.; Efthimiadou, A.; Bilalis, D.J. Effect of biocyclic humus soil on yield and quality parameters of processing tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.). Sci. Hortic. 2019, 76, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Bilalis, D.; Krokida, M.; Roussis, I.; Papastylianou, P.; Travlos, I.; Cheimona, N.; Dede, A. Effects of organic and inorganic fertilization on yield and quality of processing tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.). Folia Hortic. 2018, 30, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.