Abstract

This study examines the critical water management crisis facing the Río Turbio Basin (RTB) in Mexico’s Bajío region, Guanajuato. The RTB’s challenges are driven by a convergence of environmental degradation, industrial pollution, groundwater over-extraction, and fragmented governance structures. Intensified by climate change, urban expansion, and rising industrial demands, these issues place the basin’s long-term sustainability at serious risk. Employing a qualitative approach, this research synthesizes insights from expert interviews and stakeholder perspectives, highlighting the social, economic, environmental, and institutional dimensions of the crisis. Key findings point to a lack of collaboration among governmental bodies, industry, and local communities, resulting in escalating water scarcity, economic vulnerability in agriculture, and rising social tensions over resource allocation. The RTB exemplifies broader regional water management issues, where institutional fragmentation and the absence of strategic, basin-specific policies undermine sustainable practices. Without coordinated, multi-sectoral interventions, projections indicate worsening declines in water quality and availability, with potentially irreversible effects on ecosystems and public health. This study underscores the need for integrated water resource management (IWRM) strategies, combining technological, regulatory, and community-driven solutions to address the unique socio-environmental challenges of the Bajío region.

1. Introduction

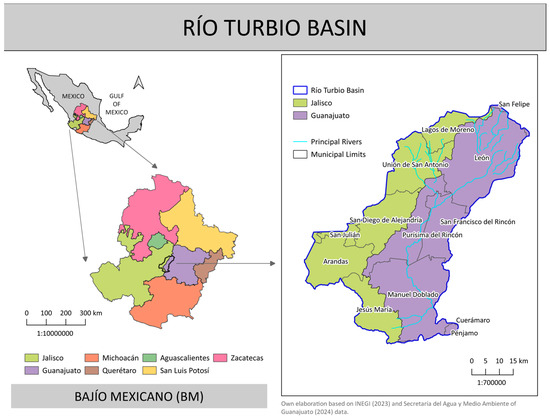

The Río Turbio Basin (RTB), located in the Bajío Mexicano (BM) region, exemplifies the complex challenges of water management in arid and semi-arid areas. As shown in Figure 1, the BM encompasses the states of Guanajuato, Jalisco (eastern region), Querétaro, Michoacán (northern region), Aguascalientes, San Luis Potosí (western region), and Zacatecas (southern region). The RTB is situated in the center of the BM, in the states of Guanajuato and Jalisco, with extreme coordinates between 20°32′42″ and 21°21′18″ north latitude and 101°27′82″ and 102°17′57″ west longitude [1]. Some authors, however, argue that this basin extends southwestward within the state of Guanajuato, following the main tributary of the Río Turbio (RT) [2,3].

Figure 1.

Maps of the Río Turbio Basin within the Bajío Mexicano region. The maps were created using QGIS software, version 3.10.9. Our own elaboration is based on INEGI (2023) and Secretaria del Agua y Medio Ambiente of Guanajuato (2024) data.

The term “crisis” in this research refers to a multidimensional state whereby water resources in the RTB are subject to severe stress due to environmental, social, economic, and institutional factors. Such a state is characterized by measurable phenomena such as aquifer depletion exceeding recharge rates, industrial contamination surpassing regulatory thresholds, and rising social conflicts over resource allocation. These elements collectively disrupt the basin’s ability to sustainably meet the water demands of its population and ecosystems.

The existing literature features extensive documentation of the environmental and hydrological aspects of the RTB, focusing on pollution from industrial sectors, notably the leather industry in León, and the impacts of excessive groundwater extraction. Historically, this basin served as a critical water source for agriculture, industry, and local communities. However, rapid urbanization, industrial expansion, and climate change have precipitated a multidimensional water crisis. The RTB now faces severe environmental degradation, groundwater over-extraction, and institutional fragmentation, all of which threaten the basin’s sustainability and the well-being of its dependent populations [4,5,6,7,8,9,10].

Despite the RTB’s strategic importance in terms of the region’s socio-economic development, current management approaches remain inadequate in addressing these escalating challenges. While these studies highlight the severity of water contamination and resource depletion, there is a noticeable gap in exploring the socio-political dimensions of the crisis. Institutional weaknesses, governance fragmentation, and the socio-economic implications of water scarcity have received limited attention.

This study addresses this critical gap by employing a qualitative methodology to analyze the interconnected social, economic, environmental, and institutional factors driving the crisis. Our research seeks to answer the following question: how can sustainable and integrated water management strategies be developed to address the multidimensional water crisis in the RTB? To address this question, the study combines a case study of the RTB with semi-directed interviews with key experts, including academic and research professionals, government officials, industrial representatives, and local community members. The findings reveal the critical role of institutional fragmentation, governance weaknesses, and social inequities in exacerbating water scarcity and environmental degradation. These insights contribute to the development of targeted interventions, including improved regulatory frameworks, technological innovations, and participatory governance models. Our research provides practical recommendations aimed at fostering sustainable water management while addressing the unique socio-environmental challenges of the RTB.

This manuscript is organized into several sections to ensure a clear and systematic presentation. The Introduction outlines the research context, significance, and objectives. The literature review provides an in-depth analysis of existing studies on water management in the RTB and the broader BM region, identifying key gaps. The Methodology section details the qualitative approach, including the case study design and data collection through expert interviews. The Results section presents the key findings across social, environmental, economic, and institutional dimensions, followed by a discussion that synthesizes these insights to propose actionable strategies. Finally, the Conclusion highlights the broader implications of the study and its contributions to the discourse on sustainable water governance in arid and semi-arid regions.

1.1. Literature Review

This section provides an overview of prior research on water management in the RTB and the broader BM region, highlighting the urgent need to address the region’s institutional, social, economic, and environmental challenges arising from water scarcity and mismanagement.

1.1.1. Water Management in the Río Turbio Basin

The multidimensional water crisis in the RTB is shaped by a complex mix of social, economic, and political factors [11]. Reliance on groundwater for agriculture, industry, and domestic use has led to significant aquifer depletion, driven primarily by industrial and agricultural over-extraction [1], more details on which can be seen in Appendix A. Additionally, untreated industrial waste—most notably from León’s leather industry—has severely contaminated the RT, reducing its capacity to support local populations and ecosystems that depend on the river’s resources [2].

The broader BM region is highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, including rising temperatures and irregular precipitation patterns that exacerbate water stress and increase the frequency of extreme weather events [12]. Some authors have reported that climate change is projected to reduce effective recharge in the RTB [13]. Although surface runoff may increase, water percolation within the basin is expected to decline. These environmental pressures, compounded by pollution and over-extraction, highlight the urgent need for sustainable water management approaches that integrate environmental protection with institutional reforms [8].

1.1.2. Institutional Framework and Governance Challenges in the Río Turbio Basin

Although integrated water resource management (IWRM) policies were adopted in the 1990s to balance economic development with environmental protection [14,15,16], the RTB’s water management framework remains fragmented. The inconsistent implementation of IWRM has resulted in weak coordination across government levels and the limited enforcement of environmental regulations [17,18,19].

Theoretically, the 2012 amendment to Article IV of the Mexican Constitution, which enshrines the human rights to water, sanitation, and a healthy environment, supports efforts to address unsustainable practices [20,21,22,23]. However, conflicting interests among agriculture, industry, and local communities hinder effective governance in the RTB. Large industries, especially in León, exert considerable control over water resources, resulting in an uneven distribution of water and escalating conflicts among stakeholders.

1.1.3. The Role of Actors in Water Management

The diversity of actors involved in water management—ranging from government agencies to non-governmental organizations, local communities, and private industries—complicates the governance of the RTB. Some authors highlight that these actors often have conflicting interests, with economic actors seeking greater access to water while local communities struggle to secure sufficient supply for their basic needs [14,17,24,25]. This dynamic is particularly evident in the BM region, where groundwater overuse by industry and agriculture has left rural communities vulnerable to water shortages and contamination [3,6].

Effective collaboration between governmental and non-governmental actors is essential for resolving the multidimensional water crisis in the RTB. Community involvement in water management decisions has become increasingly important, particularly as the impacts of climate change and industrial expansion continue to strain water resources [1,26,27]. However, the success of these initiatives depends on establishing robust institutional frameworks that support sustainable water management [28,29,30].

1.1.4. Toward Integrated and Sustainable Water Management

The future of water management depends on integrating environmental sustainability with economic development goals [31,32,33,34,35]. According to Schmieder et al. (2018), achieving sustainable water management will require addressing institutional weaknesses, improving regulatory enforcement, and promoting technological innovations in water use. Collaborative efforts among government agencies, local communities, and industrial stakeholders have shown promise for integrated water management programs capable of mitigating environmental degradation while addressing water scarcity [11,36,37,38]. Expanding these initiatives across the RTB will require more robust governance structures, enhanced institutional collaboration, and the adoption of advanced technologies to improve water efficiency within both the agricultural and industrial sectors.

2. Materials and Methods

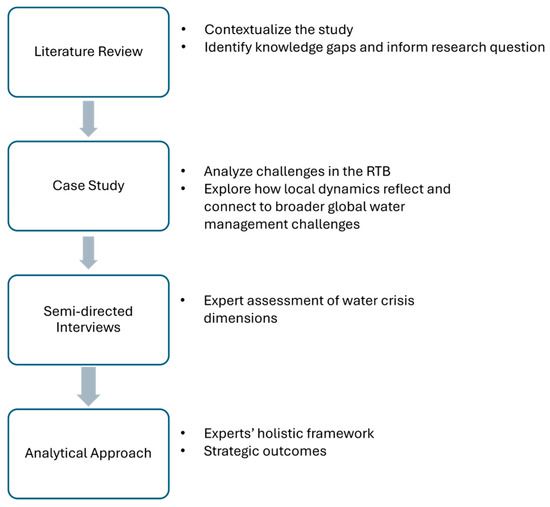

This study employs a qualitative methodology to explore the water management crisis in the RTB, focusing on the perspectives of experts involved in the governance and administration of water resources within the basin and the BM. The qualitative approach integrates a case study, a literature review, and semi-directed interviews to enable a comprehensive understanding of the social, environmental, and institutional challenges that the RTB faces. By analyzing expert opinions, this study generates specific recommendations aimed at addressing critical issues in water resource management (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Methodological framework (designed by the authors).

2.1. Literature Review

An exhaustive review of the academic literature, technical reports, and policy documents was conducted to contextualize the study and identify gaps in existing knowledge. The literature search was carried out using multiple academic and technical databases, including Web of Science, Scopus, Google Scholar, and ResearchGate. Additionally, governmental and institutional repositories such as CONAGUA, INEGI, and local water agencies were consulted to include policy reports and technical assessments relevant to the RTB.

The search strategy employed a combination of Boolean operators and targeted key-words to ensure comprehensive coverage of relevant topics. The primary search terms included are as follows:

- “water management” AND “Mexico” AND “Bajío region”;

- “Río Turbio Basin” AND “groundwater depletion”;

- “industrial pollution” AND “León leather industry” AND “water governance”;

- “climate change” AND “water scarcity” AND “aquifer over-extraction”;

- “institutional fragmentation” AND “water policy” AND “governance challenges”.

These keywords were refined through an iterative process, incorporating additional terms identified in preliminary searches. The findings from the literature review underscored the lack of integrated governance mechanisms, the socio-economic vulnerabilities linked to water scarcity, and the critical role of industrial actors in shaping water resource allocation.

2.2. Case Study

The case study approach is a vital method in social sciences, providing detailed insight into phenomena within their real-world contexts [39,40,41]. In this research, the RTB serves as a microcosm of the broader water management challenges faced in the BM. This case study enables a systematic examination of the key factors driving the multidimensional water crisis, including institutional weaknesses, industrial contamination, and the impacts of climate change. By documenting the interactions between these elements, this research offers a comprehensive picture of how social, environmental, and political dimensions interact and influence water management in the RTB. The selection of the RTB as a case study is grounded in the identification of several issues affecting the water crisis, such as groundwater over-extraction, pollution from industrial sectors, and institutional fragmentation. This approach allows for a focused examination of how local dynamics reflect broader global water challenges, providing a basis for developing tailored strategies to address these specific issues [42,43,44,45].

2.3. Semi-Directed Interviews

Semi-directed interviews were conducted during the last quarter of 2023 and the first three quarters of 2024, involving a total of 28 participants: 8 academics and researchers, 12 government officials, 3 industrial representatives, and 5 members of the local community. This diversity ensured a comprehensive representation of perspectives and expertise. The participants were selected based on their direct involvement in water management within the RTB and their ability to provide informed insights into the multidimensional crisis. These interviews provided in-depth insights into the institutional fragmentation, regulatory deficiencies, and social conflicts surrounding water governance in the basin [46,47,48]. The flexible format of the interviews allowed experts to express their opinions and share their experiences, while ensuring that discussions remained focused on the primary research questions.

The interviews focused on five critical dimensions of the water crisis:

- Climate Change: Participants discussed the exacerbation of water scarcity due to changing weather patterns, prolonged droughts, and extreme events.

- Social Terms: Interviewees addressed issues of inequity in water allocation, and the impacts on local communities were central topics.

- Economic Factors: The economic implications of water shortages, particularly for agriculture and industry, were examined.

- Environmental Impacts: Experts highlighted ecosystem degradation, biodiversity loss, and pollution as pressing concerns.

- Institutional Challenges: Weak regulatory frameworks and a lack of coordination across governance levels were identified as significant barriers.

The structure of the semi-directed interviews, including thematic categories and key questions, is provided in the Appendix B. To ensure participant anonymity and confidentiality, all identifiable information was meticulously excluded during data processing. Verbal confidentiality agreements were established with each participant to secure their trust and guarantee that their contributions would remain untraceable to specific individuals or organizations. All interviews were audio-recorded with consent, transcribed verbatim, and subjected to a rigorous manual coding process. This coding, conducted using Microsoft Office tools, systematically organized the data and facilitated the extraction of recurring themes and patterns. This approach enabled the construction of a coherent narrative reflecting the complex interconnections among institutional weaknesses, environmental challenges, and socio-economic dynamics impacting water management in the RTB.

2.4. Analytical Approach

The integration of the case study and semi-directed interviews provided a comprehensive framework for analyzing the intricate dynamics of water management within the RTB. This methodological combination facilitated a nuanced understanding of the multidimensional crisis, documenting its real-world implications and capturing the socio-political, environmental, and economic pressures affecting the basin. The research findings serve as critical inputs for crafting sustainable strategies to address these ongoing challenges, with a strong emphasis on integrated water resource management and enhanced cross-institutional collaboration. By highlighting the necessity of collaborative frameworks, this study underscores the importance of engaging diverse actors—ranging from local communities to government bodies and industrial stakeholders—in the pursuit of sustainable and equitable water governance. Such an approach is essential in navigating the escalating environmental and social pressures threatening the RTB.

3. Results

This section presents the key findings of our research, focusing on five critical dimensions shaping the water management crisis in the RTB: climate change, social dynamics, economic factors, environmental impacts, and institutional challenges. Insights are drawn from a qualitative analysis of expert interviews and stakeholder perspectives, offering a comprehensive view of the interconnected issues facing the region.

3.1. Current Situation of Water Management in the Río Turbio Basin

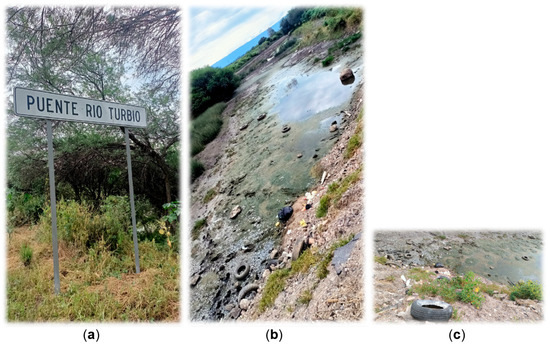

Characterized by severe industrial contamination, groundwater overexploitation, and fragmented governance, the RTB exemplifies a profound water management crisis. Industrial pollution, particularly from León’s leather industry, has led to the significant degradation of water quality [49,50,51]. As shown in Figure 3, the discharge of untreated, toxic wastewater directly into the river has compromised public health and severely impacted the basin’s ecosystems.

Figure 3.

The images (a–c) taken during fieldwork in 2024 illustrate the impact of untreated toxic wastewater discharged directly into the river in the municipality of Manuel Doblado.

Agricultural and industrial groundwater over-extraction has resulted in continuous declines in aquifer levels, exacerbating water scarcity across the basin. This pressure on groundwater supplies is heightened by resistance from certain industries to adopt water-saving technologies and sustainable practices, leaving local communities with limited access to clean water. Water resources have thus become highly contested, with industrial and agricultural sectors often securing priority access, which thus further marginalizes local populations.

Socially, this inequality in water access has intensified tensions within rural communities, where residents are increasingly competing with industrial stakeholders for dwindling resources. Local populations are disproportionately affected by both reduced availability and declining water quality, leading to escalating social conflicts and resentment toward industries perceived to have greater control over water resources.

Institutionally speaking, a lack of coordination between federal, state, and local authorities has compounded water management challenges in the RTB. Fragmentation among these governing bodies has resulted in reactive, short-term management practices rather than proactive, long-term planning. This institutional divide not only hampers efforts to address critical water issues but also perpetuates inequities in resource distribution, impeding the development of sustainable water management strategies across the basin.

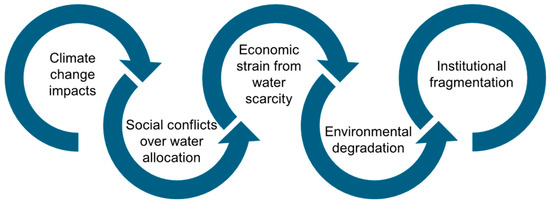

3.2. Factors Driving the Multidimensional Water Crisis

The water crisis in the RTB is driven by a combination of interrelated factors, each contributing to the increasingly precarious state of water management in the region (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Factors driving the multidimensional water crisis (designed by the authors).

- ❖

- Climate Change Impacts: Climate change is a significant driver of water scarcity, manifesting in extended droughts, irregular rainfall, and more frequent extreme weather events. These shifts intensify pressure on water resources, making resource allocation unpredictable and complicating management efforts. The increasingly common prolonged droughts in the RTB illustrate the strain that climate variability places on already limited water supplies, necessitating urgent adaptive measures.

- ❖

- Social Conflicts over Water Allocation: Unequal water access has led to significant social tensions, particularly between industrial stakeholders and local communities. The demands of expanding industrial activities often prioritize larger, better-resourced sectors, leaving local populations and agricultural users at a disadvantage. This disparity in access fosters resentment among residents, as they face reduced availability while competing with industries for dwindling resources, increasing the potential for conflict.

- ❖

- Economic Strain from Water Scarcity: Persistent water shortages place Guanajuato’s agricultural sector—which is highly dependent on consistent water access—at substantial risk. Reduced water availability threatens agricultural productivity, endangering local livelihoods and regional food security. As scarcity continues, the economic stability of the region grows increasingly dependent on sustainable water management practices that can equitably support agriculture alongside other high-demand sectors.

- ❖

- Environmental Degradation: Industrial discharges and unsustainable water extraction are critically impairing the RTB’s ecosystems. Ongoing pollution and over-extraction not only endanger biodiversity but also diminish the basin’s capacity to provide clean, usable water in the long term. As natural habitats degrade, their resilience weakens, reducing their ability to recover from both human-induced and climate pressures and pushing the region closer to ecological collapse.

- ❖

- Institutional Fragmentation: The RTB suffers from a fragmented governance structure, with disjointed oversight across federal, state, and local levels. This lack of cohesive governance results in inconsistent policy enforcement and insufficient coordination, undermining effective water management strategies. Addressing these structural weaknesses requires an integrative approach that aligns goals and actions across all levels of government, establishing the unified governance essential for sustainable water management in the basin.

3.3. Implications and Consequences

The water crisis in the RTB carries significant implications across social, economic, environmental, and institutional dimensions, highlighting the urgent need for comprehensive water management strategies (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Implications and consequences (designed by the authors).

- ❖

- Health Risks and Environmental Degradation: The pollution of the RT, which is primarily due to untreated industrial waste from the leather and other high-pollution sectors, poses severe health risks for communities dependent on this water supply. Contaminants in the water are linked to numerous health issues within local populations. Furthermore, the degradation of ecosystems disrupts biodiversity and destabilizes natural water cycles, exacerbating challenges in maintaining water quality and availability for both human and environmental needs.

- ❖

- Escalating Social Conflicts: The competition for limited water resources has intensified social tensions among industrial users, agricultural sectors, and local communities. Industrial demands, often prioritized due to economic influence, restrict water access for agricultural and community needs, leading to resentment and heightened conflict. Without equitable water allocation policies, these conflicts are expected to worsen, particularly in vulnerable rural communities where shortages are felt more acutely.

- ❖

- Economic Vulnerability: The region’s economic resilience, especially within its water-dependent agricultural sector, is closely tied to reliable water access. Persistent water scarcity jeopardizes the viability of local farming, threatening productivity and food security. This economic strain risks cascading through the region, impacting employment, local income, and overall economic stability across the RTB and surrounding areas.

- ❖

- Ecosystem Collapse: Unchecked pollution and water resource over-extraction have placed the RTB’s ecosystems at a critical tipping point. The unregulated exploitation of ground- and surface water disrupts essential ecological balances, risking the loss of biodiversity and natural processes vital for the region’s sustainability. Experts warn that without swift intervention, the RTB may lose its capacity to support both human populations and the ecosystems that depend on it, potentially leading to irreversible environmental degradation.

- ❖

- Institutional and Policy Gaps: Institutional fragmentation and weak policy frameworks have exacerbated the water crisis in the RTB. Ineffective enforcement and a lack of cohesive governance structures allow unsustainable practices, such as over-extraction and pollution, to persist. Experts underscore the need for a robust institutional framework with clearly defined accountability and coordination among all levels of government. Strengthened regulatory oversight, supported by enforceable policies, is essential for tackling the multidimensional challenges of water management in the RTB. Implementing these reforms would lay a foundation for sustainable practices and build resilience against ongoing environmental and social pressures in the basin.

3.4. Synthesis of the Current Situation in the Río Turbio Basin

The RTB’s water crisis represents a profoundly interconnected challenge, shaped by the combined forces of climate change, social inequities, economic pressures, environmental degradation, and fragmented governance. The crisis reveals critical vulnerabilities that extend beyond mere water scarcity, highlighting systemic issues within social structures and institutional frameworks. The findings emphasize that inconsistent policy coordination, insufficient regulatory enforcement, and a lack of unified, collaborative action among stakeholders have collectively intensified the basin’s fragility.

To address these complex challenges, an integrated approach is imperative. Sustainable water practices must be prioritized, alongside the development of more robust governance structures and active cooperation from all sectors—government agencies, industry, agriculture, and local communities. Each sector’s involvement is essential for forging an effective, resilient water management strategy that is adaptable to the basin’s unique socio-environmental context. The need for immediate, comprehensive intervention is critical. Without sustained, forward-thinking planning, the basin’s water resources will remain vulnerable to escalating pressures, jeopardizing the ecosystem’s health, regional stability, and the well-being of communities reliant on these essential resources.

4. Discussion

Building on the findings from the RTB, this discussion emphasizes the far-reaching implications of the multidimensional water crisis, with particular attention paid to the region’s unique challenges. Addressing these challenges demands a multi-level, context-sensitive public policy approach [52,53,54]. The complexity of the water crisis in the BM underscores that piecemeal or isolated interventions are insufficient. Instead, an integrated and regionally adapted strategy is essential, as highlighted by experts who stressed the importance of institutional coordination, sustainable practices, and participatory governance.

Although the number of interviews conducted was limited, their strategic selection ensured a representative and analytically robust understanding of the systemic challenges facing the RTB. The diverse range of participants—academics, government officials, industry representatives, and local community members—was deliberately chosen to capture the multidimensional and intersecting issues at play. This methodological approach prioritized depth over breadth, focusing on key informants with direct involvement and decision-making power in water governance, resource management, and industrial activities.

The constraints on expanding the number of interviews stemmed from institutional barriers, time limitations, access challenges, and security concerns in the region, particularly in engaging private sector stakeholders and certain government agencies with vested interests in water resource allocation. Some areas in the RTB are affected by socio-political tensions and security risks, posing additional challenges for fieldwork and limiting accessibility to certain communities and stakeholders. These factors influenced the feasibility of conducting a larger number of interviews, as ensuring the safety of researchers and participants was a priority.

Additionally, interview saturation was reached, as recurrent themes emerged consistently across the interviews, reinforcing the validity and robustness of the qualitative insights. Expanding the dataset could have introduced additional nuances, but it is unlikely that it would have significantly altered the core findings, given the convergence of perspectives across different stakeholder groups. To address this limitation in future research, a mixed-methods approach combining stakeholder interviews with participatory workshops and quantitative surveys could provide a broader empirical base while maintaining the depth of qualitative analysis.

A central theme that emerged from experts’ insights was the disconnect between national water policies and the realities faced by regions such as the RTB. This misalignment perpetuates practices that exacerbate the current water crisis [55,56,57]. Consequently, regionalizing water policy emerges as a critical necessity to reflect and respond to the unique socio-environmental conditions of Guanajuato [58] and the RTB.

National policies often overlook the complex interplay between environmental, economic, and social factors that characterize water crises in regions like the BM [11,59,60]. In the RTB, water scarcity is compounded by industrial pollution and fragmented governance, creating a crisis with distinct regional dynamics. Experts emphasize the need for policies that integrate robust environmental protection while addressing local economic priorities and embedding sustainable practices directly into water management frameworks.

Promoting sustainable water management in the RTB requires a shift from centralized, one-size-fits-all approaches to regionally adapted strategies. Such policies must address urgent challenges, including water scarcity, pollution, and governance fragmentation, while fostering long-term resilience [61,62,63]. By aligning water management frameworks with the RTB’s specific needs, these strategies can provide effective and enduring solutions, ensuring the basin’s sustainability and adaptability to future socio-environmental pressures.

4.1. Challenges and Proposed Solutions

The RTB faces a series of interconnected challenges that severely compromise sustainable water management. These challenges span environmental, social, economic, and institutional dimensions, creating a complex web of obstacles that requires immediate attention:

- Groundwater Over-Extraction: The excessive withdrawal of groundwater for industrial and agricultural purposes has led to significant aquifer depletion. This overuse places the region’s water security at risk, jeopardizing both short-term access and long-term sustainability.

- Industrial Pollution: Untreated wastewater, particularly from León’s leather industry, has severely degraded water quality in the basin. Toxic discharges into the RT affect public health and the viability of aquatic ecosystems, intensifying water scarcity and ecological vulnerabilities.

- Institutional Fragmentation: The lack of coordination among federal, state, and local authorities has resulted in disjointed water management practices. Fragmented governance frameworks hinder the implementation of integrated strategies and contribute to inequities in water allocation and enforcement failures.

Addressing these challenges requires targeted solutions tailored to the basin’s specific socio-environmental context:

- Regulatory Strengthening: Establish and enforce strict limits on groundwater extraction and implement pollution control measures to reduce industrial discharges.

- Technological Integration: Encourage the adoption of advanced water-saving and recycling technologies in both agricultural and industrial sectors.

- Institutional Coordination: Develop a unified water management authority for the RTB, tasked with aligning policies, enhancing enforcement, and promoting multi-stakeholder collaboration.

4.2. Opportunities for Improvement

Despite the pressing challenges in the RTB, numerous opportunities exist to transform its water management systems into a model of sustainability and resilience. These opportunities are grounded in innovation, community engagement, and strategic governance reforms:

- Technological Innovations: Advances in precision irrigation, wastewater recycling, and pollution control technologies present significant opportunities for reducing water demand and improving resource efficiency. These solutions are particularly relevant in water-intensive sectors such as agriculture and industry.

- Participatory Governance: The expansion of community-based water management models, such as the Technical Councils on Water (COTAS) in Guanajuato, underscores the potential for inclusive and accountable decision-making. Strengthening participatory frameworks can ensure equitable water allocation while fostering trust and cooperation among stakeholders.

- Climate Adaptation Strategies: Integrating climate resilience into regional water policies offers a pathway for mitigating the impacts of extreme weather events and prolonged droughts. Measures such as rainwater harvesting, aquifer recharge programs, and ecosystem restoration can enhance the region’s capacity to adapt to climate variability.

- Investment in Research and Education: Promoting research into sustainable water practices and raising public awareness about conservation can drive long-term behavioral changes and innovation. Public education campaigns and collaborative research initiatives should focus on equipping communities and industries with tools to reduce water stress.

By leveraging these opportunities, the RTB can address existing vulnerabilities while laying the foundation for sustainable and inclusive water management practices.

4.3. Recommendations for Water Management in the State of Guanajuato

To address the specific challenges of water management in Guanajuato, this section consolidates key recommendations into actionable strategies. These are organized to ensure coherence, eliminate redundancy, and provide a clear framework for sustainable water management:

- Integrated water planning through the following:

- Alignment with the socio-environmental context of Guanajuato;

- Incorporating comprehensive resource assessments and prioritizing interventions tailored to local needs.

- Promoting water efficiency through the following:

- Implementing modern irrigation systems to reduce water use in agriculture;

- Promoting wastewater recycling in industrial processes to reduce reliance on freshwater sources.

- Protection and restoration of water sources through the following:

- Establishing protected areas for key water sources;

- Strengthening regulatory frameworks for pollution control and extraction limits.

- Stakeholder engagement and participatory governance through the following:

- Expanding participatory governance models like COTAS;

- Ensuring equitable water allocation policies that integrate local perspectives.

4.4. Policy Recommendations for Water Policy in the Bajío Region

This section outlines policy recommendations specific to the BM region, emphasizing systemic improvements to address its unique water management challenges.

- Strengthening regional governance structures implies establishing regional water councils to achieve the following:

- Coordinate efforts among federal, state, and local authorities;

- Align water management strategies with regional needs and ensure accountability.

- Adopting participatory and inclusive governance models implies expanding the Technical Councils on Water (COTAS) to include diverse stakeholders, ensuring the following:

- Greater representation of marginalized communities in decision-making;

- Integration of local knowledge into policy development.

- Incentivizing sustainable practices in high-impact sectors implies encouraging water efficiency in agriculture and industry through the following:

- Tiered pricing systems that promote conservation;

- Subsidies for adopting advanced irrigation and wastewater recycling technologies.

- Enhancing climate adaptation measures suggests developing infrastructure and policies to mitigate climate-related risks, such as the following:

- Rainwater harvesting systems and aquifer recharge programs;

- Resilient water storage and flood control measures.

- Promoting transparency and accountability suggests implementing oversight mechanisms to ensure equitable water allocation through the following:

- Establishing an independent body to monitor water rights and combat corruption;

- Conducting regular audits and public reports on water resource use.

Adopting these policy recommendations offers the BM region a transformative pathway toward sustainable and equitable water management, ensuring the pressing needs of its communities, ecosystems, and industries are met with resilience and fairness.

4.5. Future Water Scenarios for Guanajuato

This section presents a forward-looking analysis of Guanajuato’s water resources, highlighting the consequences of action versus inaction. The scenarios are simplified into two contrasting pathways to avoid redundancy and emphasize the importance of immediate intervention:

Pessimistic Scenario (if challenges remain unaddressed): If groundwater over-extraction, industrial pollution, and governance fragmentation remain unaddressed, Guanajuato will face the following:

- Severe water scarcity, compromising agriculture and public health;

- Escalating social conflicts due to inequitable resource allocation;

- Irreversible ecological damage, leading to biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse.

Optimistic Scenario (if opportunities are leveraged): By implementing sustainable practices and robust governance, Guanajuato could achieve the following:

- Long-term water security, supported by efficient technologies and equitable policies;

- A healthier ecosystem, with improved water quality and biodiversity restoration;

- Economic resilience, ensuring the stability of water-dependent sectors such as agriculture and industry.

The juxtaposition of these scenarios highlights the need for immediate and sustained action. The decisions made today will determine whether Guanajuato moves toward a future of resilience and sustainability or one of crisis and instability.

5. Conclusions: From Local Water Crises to Global Lessons for Sustainability

The RTB exemplifies a unique case within the global context of water management challenges due to its specific combination of socio-environmental pressures, including acute industrial pollution from León’s leather industry, severe aquifer depletion driven by agricultural and industrial over-extraction, and pronounced governance fragmentation at federal, state, and local levels. Our research found that, unlike other regions, the RTB’s crisis is further exacerbated by the absence of basin-specific policies and industrial stakeholders’ disproportionate control over water resources, which intensifies social inequities and environmental degradation. Therefore, these dynamics highlight the RTB as a critical case for examining how regional governance weaknesses, coupled with localized environmental stressors, can undermine sustainable water management.

As a result, immediate and decisive actions are required to secure water resources for future generations, preserve critical ecosystems, and ensure resilience in communities and industries alike. Furthermore, these findings provide a strong foundation for advancing research on vulnerability, resilience, and adaptation to global change. This is particularly relevant in exploring the dynamics of water resources in arid and semi-arid regions, where environmental pressures, socio-economic complexities, political dynamics, and water scarcity demand innovative and sustainable strategies.

This research emphasizes how addressing the RTB’s water crisis is not merely a technical challenge but also a socio-political imperative that can be understood and measured through qualitative methods based on expert assessments. These methods provide critical insights into the multifaceted nature of the crisis by capturing the interplay of institutional fragmentation, social inequities, and environmental stressors—dimensions that quantitative metrics alone often fail to reveal. By leveraging the knowledge and perspectives of diverse stakeholders, qualitative assessments enable a nuanced understanding of governance gaps, stakeholder conflicts, and socio-political dynamics, thereby informing more context-sensitive and effective interventions.

In this context, this study highlights the RTB’s relevance not only as a microcosm of global water challenges but also as an illustrative example of the urgent need for tailored, regionally adapted strategies that integrate technological innovation, participatory governance, and robust regulatory frameworks. The findings provide actionable insights into how systemic issues such as institutional fragmentation and stakeholder conflicts can be addressed, offering lessons that extend beyond Guanajuato. By focusing on the unique socio-environmental characteristics of the RTB, this research contributes new perspectives to the literature on IWRM, while emphasizing the importance of adapting global frameworks with localized realities to achieve equitable and sustainable outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.F.N.; methodology, L.F.N.; software, L.F.N.; validation, L.F.N.; formal analysis, L.F.N.; investigation, L.F.N. and J.A.P.-B.; resources, L.F.N. and J.A.P.-B.; data curation, L.F.N.; writing—original draft preparation, L.F.N.; writing—review and editing, L.F.N. and J.A.P.-B.; visualization, L.F.N. and J.A.P.-B.; supervision, L.F.N.; funding acquisition, L.F.N. and J.A.P.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article and Appendix B.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the anonymous experts who participated in the interviews and shared valuable insights that enriched this study. We also extend our appreciation to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions, which significantly improved the quality of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Current Status of Groundwater in RTB Aquifers

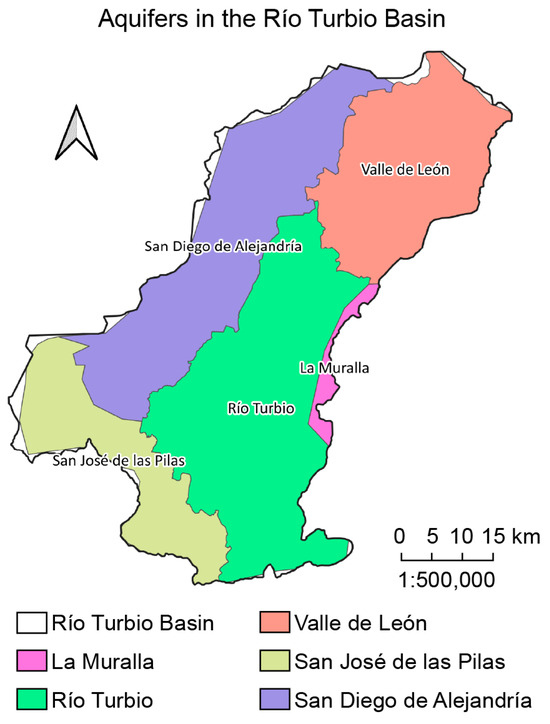

Figure A1 illustrates the aquifers located within the Río Turbio Basin (RTB), which include the Valle de León, Río Turbio, and La Muralla aquifers in the state of Guanajuato, as well as the San Diego de Alejandría and San José de las Pilas aquifers in Jalisco. According to the updated reports on average annual groundwater availability from CONAGUA (up to 2024) [source: [https://sigagis.conagua.gob.mx/dma230911/#, accessed on 13 February 2005. Please refer to the section Información/Descargar_datos]], the RTB aquifers are in a state of overexploitation. This means they face a deficit, leaving no available volumes for granting new water concessions. For additional details, refer to Table A1.

Figure A1.

Aquifers in the Río Turbio Basin. The maps were created using QGIS software, version 3.10.9. Our elaboration is based on CONAGUA (2023) data. Source: https://sigagis.conagua.gob.mx/dma230911/# accessed on 13 February 2025.

Table A1.

Parameters for water availability by aquifer.

Table A1.

Parameters for water availability by aquifer.

| Code | Aquifer | Recharge (R) | Committed Natural Discharge (DNC) | Groundwater Extraction Volumes (VEAS) | Average Annual Availability (DMA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1111 | La Muralla | 34.8 | 5.0 | 40.141518 | −10.341518 |

| 1113 | Valle de León | 124.5 | 0.0 | 186.138096 | −61.638096 |

| 1114 | Río Turbio | 110.0 | 0.0 | 164.256337 | −54.256337 |

| 1444 | San Diego de Alejandría | 36.5 | 0.0 | 46.106796 | −9.606796 |

| 1445 | San José de las Pilas | 19.8 | 6.3 | 15.066512 | −1.566512 |

Note: the units are expressed in cubic hectometers (hm3), equivalent to a million cubic meters per year.

Appendix B

Structure of Semi-Directed Interviews

Table A2.

Overview of the Structure of Semi-Directed Interviews.

Table A2.

Overview of the Structure of Semi-Directed Interviews.

| 1. Introduction | The semi-directed interviews conducted for this study aimed to explore the multidimensional water crisis in the Río Turbio Basin (RTB). The objective was to gain insights from key stakeholders regarding governance challenges, environmental degradation, social conflicts, and economic vulnerabilities linked to water management in the RTB. | |

| 2. Interview Format | The interviews followed a semi-structured format, allowing flexibility for participants to elaborate on key issues while ensuring consistency in data collection across different stakeholder groups. Interviews were conducted between Q4 2023 and Q3 2024 and lasted approximately 45–60 min each. | |

| 3. Stakeholder Groups | Interviewees were selected based on their expertise and involvement in water management within the RTB. The stakeholder groups included the following: |

|

| 4. Thematic Categories and Sample Questions | The interviews covered five thematic dimensions: |

|

| 5. Ethical Considerations and Confidentiality | All interviews were conducted under strict confidentiality agreements. Participants were informed of their right to anonymity, and no personally identifiable information was recorded. Consent was obtained for audio recording, and transcripts were anonymized before analysis. | |

| 6. Data Analysis Approach | Interviews were transcribed verbatim and manually coded to identify recurring themes. The qualitative analysis followed an iterative process, ensuring that emerging patterns reflected the perspectives of different stakeholder groups. |

References

- González-Leiva, F.; Ibáñez-Castillo, L.A.; Valdés, J.B.; Vázquez-Peña, M.A.; Ruiz-García, A. Pronóstico de caudales con Filtro de Kalman Discreto en el río Turbio. Tecnol. Cienc. Agua 2015, 6, 5–24. Available online: https://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/tca/v6n4/v6n4a1.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- González Santana, O. El reto de la gestión del agua en las regiones de México ante los efectos del cambio climático: El caso de la cuenca del río Turbio. Cuad. Geogr. Rev. Colomb. Geogr. 2013, 22, 125–144. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0121-215X2013000200008&lng=en&tlng=es (accessed on 26 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Orozco, I.; Martínez, A.; Ortega, V. Assessment of the Water, Environmental, Economic and Social Vulnerability of a Watershed to the Potential Effects of Climate Change and Land Use Change. Water 2020, 12, 1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Ecología y Cambio Climático (INECC). Impacto del Cambio Climático en Los Recursos Hídricos de México; INECC: Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Padilla, B.E.; Esquer-Peralta, J.; Munguía-Morales, H.E.; Esquer-Miranda, E.; García-Bedoya, D. Tanning leather environmental assessment: A case study in León, Mexico. Propues. Ambient. 2023, 1, 56–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores Casamayor, H.; Morales Martínez, J.L.; Mora-Rodríguez, J.; Delgado-Galván, X. Assessing industrial impact on water sustainability in El Bajío, Guanajuato State, Mexico. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Chávez, A.; Morton-Bermea, O.; González-Partida, E.; Rivas-Solorzano, H.; Oesler, G.; García-Meza, V.; Hernández, E.; Morales, P.; Cienfuegos, E. Environmental geochemistry of the Guanajuato Mining District, Mexico. Ore Geol. Rev. 2003, 23, 277–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocampo-Astudillo, A.; Garrido-Hoyos, S.E.; Salcedo-Sánchez, E.R.; Martínez-Morales, M. Alteration of groundwater hydrochemistry due to its intensive extraction in urban areas from Mexico. In Water Availability and Management in Mexico; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 77–97. [Google Scholar]

- Espejo, R.P. Water Pollution from Agriculture: Policy Challenges in a Case Study of Guanajuato. In Water Resources in Mexico: Scarcity, Degradation, Stress, Conflicts, Management, and Policy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 435–448. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión Nacional del Agua (CONAGUA). Estadísticas del Agua en México; CONAGUA: Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Triana, E.; Ortolano, L. Environmental impact assessment in Mexico: An analysis from a “consolidating democracy” perspective. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2005, 25, 439–463. [Google Scholar]

- Romero Lankao, P.; Qin, H. Conceptualizing urban vulnerability to global climate and environmental change: Insights from a study of climate hazards in Mexican cities. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2011, 3, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda Capacho, P.A.; Martínez Bárcemas, A.; Aguilera Rico, H.A.; Orozco Medina, I. Evaluación del impacto de la urbanización y el cambio climático sobre la recarga de aguas subterráneas y el balance hidrológico en la subcuenca del río Turbio, Guanajuato. Acta Univ. 2022, 32, e3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Water Partnership (GWP). Integrated Water Resources Management; TAC Background Papers No. 4; Global Water Partnership: Stockholm, Sweden, 2000; Available online: https://www.gwp.org (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Mitchell, B. Integrated water resource management, institutional arrangements, and land-use planning. Environ. Plan. A 2005, 37, 1335–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.K. Integrated water resources management: A reassessment. Water Int. 2004, 29, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armas Vargas, F.; Nava, L.F.; Gómez Reyes, E.; Olea-Olea, S.; Rojas Serna, C.; Sandoval Solís, S.; Meza-Rodríguez, D. Water and environmental resources: A multi-criteria assessment of management approaches. Water 2023, 15, 2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nava, L.F. La desafiante gestión integrada de los recursos hídricos en México: Elaboración de recomendaciones políticas. In Las Ciencias en Los Estudios del Agua: Viejos Desafíos Sociales y Nuevos Retosen; Ramirez, R., Pablo, J.J., Santana, O.G., Eds.; Guadalajara Editorial Universitaria: Guadalajara, Mexico, 2018; pp. 26–42. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez Serrano, J. El acceso al agua y saneamiento: Un problema de capacidad institucional local. Análisis en el estado de Veracruz. Gest. Política Pública 2010, 19, 311–350. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1405-10792010000200004&lng=es&tlng= (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Alpuche Álvarez, Y.A.; Nava, L.F.; Carpio Candelero, M.A.; Contreras Chablé, D.I. Vinculando ciencia y política pública. La Ley de Aguas Nacionales bajo la perspectiva sistémica y de servicios ecosistémicos. Gest. Política Pública 2021, 30, 133–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nava, L.F.; Medrano-Pérez, O.R.; Cáñez Cota, A.; Torres Bernardino, L. La seguridad hídrica en México: El derecho humano al agua. Una oportunidad. In Revista IAPEM, 2019, Temas de Administración Pública—Public Administration Topics, 103; Instituto de Administración Pública del Estado de México, Asociación Civil (AC): Tlalnepantla, Mexico, 2019; pp. 71–88. Available online: https://t.ly/bjBu0 (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Wilder, M.; Martínez Austria, P.F.; Hernández Romero, P.; Cruz Ayala, M.B. The human right to water in Mexico: Challenges and opportunities. Water Altern. 2020, 13, 28–48. [Google Scholar]

- Tagle-Zamora, D.; Caldera-Ortega, A.R. Regulation, public water management and market environmentalism in Mexico: An analysis from political projects. Tecnol. Cienc. Agua 2019, 10, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varady, R.G.; Albrecht, T.R.; Staddon, C.; Gerlak, A.K.; Zuniga-Teran, A.A.; Bogardi, J.J.; Gupta, J.; Nandalal, K.D.W.; Salamé, L.; van Nooijen, R.R.P.; et al. The Water Security Discourse and Its Main Actors. In Handbook of Water Resources Management: Discourses, Concepts and Examples; Bogardi, J.J., Gupta, J., Nandalal, K.D.W., Salamé, L., van Nooijen, R.R.P., Bhaduri, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mould, S.A.; Fryirs, K.A.; Howitt, R. The importance of relational values in river management: Understanding enablers and barriers for effective participation. Ecol. Soc. 2020, 25, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisfeld, S.C. Water Management: Prioritizing Justice and Sustainability; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.E. Managing water-related vulnerability and resilience of urban communities in the Pearl River Delta. In Climate Change, Security Risks, and Violent Conflicts; Hamburg University Press: Hamburg, Germany, 2020; p. 121. [Google Scholar]

- Nandineni, R.D.; Dash, S.P. Capacity Building in Water Resource Management in Developing Countries. In Clean Water and Sanitation; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 49–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ofori, A.D.; Mdee, A. Integrated water resource management. In Clean Water and Sanitation; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 344–357. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, S.L. Interventions to Strengthen Institutional Capacity for Peri-Urban Water Management in South Asia. In Water Security, Conflict and Cooperation in Peri-Urban South Asia: Flows across Boundaries; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 147–169. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, D.; Gain, A.K.; Giupponi, C. Moving beyond water centricity? Conceptualizing integrated water resources management for implementing sustainable development goals. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 15, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhao, W.; Liu, Y.; Cherubini, F.; Fu, B.; Pereira, P. Prioritizing sustainable development goals and linking them to ecosystem services: A global expert’s knowledge evaluation. Geogr. Sustain. 2020, 1, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenmenger, N.; Pichler, M.; Krenmayr, N.; Noll, D.; Plank, B.; Schalmann, E.; Wandl, M.-T.; Gingrich, S. The Sustainable Development Goals prioritize economic growth over sustainable resource use: A critical reflection on the SDGs from a socio-ecological perspective. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 15, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- lores Casamayor, H.; Morales Martínez, J.L.; Tagle-Zamora, D.; Delgado Galván, X.V. El modelo económico y su influencia en el desarrollo sustentable de cinco municipios de Guanajuato. Acta Univ. 2020, 30, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinoco, C.; Julio, N.; Meirelles, B.; Pineda, R.; Figueroa, R.; Urrutia, R.; Parra, Ó. Water resources management in Mexico, Chile and Brazil: Comparative analysis of their progress on SDG 6.5. 1 and the role of governance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittikhoun, A.; Schmeier, S. (Eds.) River Basin Organizations in Water Diplomacy; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shemer, H.; Wald, S.; Semiat, R. Challenges and solutions for global water scarcity. Membranes 2023, 13, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momen, M.N. Multi-stakeholder partnerships in public policy. In Partnerships for the Goals; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 768–776. [Google Scholar]

- Hartley, J. What is a case study. In Essential Guide to Qualitative Methods in Organizational Research; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; p. 323. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, Y.; Rashid, A.; Warraich, M.A.; Sabir, S.S.; Waseem, A. Case Study Method: A Step-by-Step Guide for Business Researchers. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2019, 18, 1609406919862424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, H.; Birks, M.; Franklin, R.; Mills, J. Case study research: Foundations and methodological orientations. Forum Qual. Sozialforsch. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2017, 18, 2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlak, A.K.; House-Peters, L.; Varady, R.G.; Albrecht, T.; Zúñiga-Terán, A.; de Grenade, R.R.; Cook, C.; Scott, C.A. Water security: A review of place-based research. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 82, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehn, U.; Montalvo, C. Exploring the dynamics of water innovation: Foundations for water innovation studies. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, S1–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl-Wostl, C. Transitions towards adaptive management of water facing climate and global change. Water Resour. Manag. 2007, 21, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagle-Zamora, D. Presa El Zapotillo: Una discusión de su pertinencia para León, Guanajuato, a una década del conflicto por el agua. Estud. Demogr. Urbanos 2003, 38, 247–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlan, C.L. Preparing for the Unanticipated: Challenges in Conducting Semi-Structured, In-Depth Interviews; SAGE Publications Limited: London, UK, 2020; pp. 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Naz, N.; Gulab, F.; Aslam, M. Development of qualitative semi-structured interview guide for case study research. Compet. Soc. Sci. Res. J. 2022, 3, 42–52. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, N.; Grant-Smith, D. In-depth interviewing. In Methods in Urban Analysis; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 105–125. [Google Scholar]

- Tagle-Zamora, D.; Caldera-Ortega, A.R. Agua, conflictos redistributivos y gobernabilidad: El caso de León, Guanajuato. In Estado y Ciudadanías del Agua: ¿Cómo Significar las Nuevas Relaciones? UAM-C y el Programa de Estudios Sobre la Ciudad UNAM: Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico, 2014; p. 175. [Google Scholar]

- Tagle-Zamora, D.; Caldera-Ortega, A.R.; Rodríguez González, J.A. Complejidad ambiental en el Bajío mexicano: Implicaciones del proyecto civilizatorio vinculado al crecimiento económico. Reg. Soc. 2017, 29, 193–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagle-Zamora, D.; Caldera-Ortega, A.R.; Villalpando Vázquez, V. Negociaciones fallidas en la cuenca del río Turbio 1987–2014: El caso de la industria curtidora y el deterioro del bien común. Argum. Mex. DF 2015, 28, 59–77. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, J.; Pahl-Wostl, C.; Zondervan, R. ‘Glocal’water governance: A multi-level challenge in the anthropocene. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2013, 5, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl-Wostl, C. A conceptual framework for analysing adaptive capacity and multi-level learning processes in resource governance regimes. Glob. Environ. Change 2009, 19, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco-Vega, R. Governing Urban Water Conflict through Watershed Councils—A Public Policy Analysis Approach and Critique. Water 2020, 12, 1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, C.L.; Cortado, A.P.; Ünver, O. Stakeholder Engagement and Perceptions on Water Governance and Water Management in Azerbaijan. Water 2023, 15, 2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teweldebrihan, M.D.; Dinka, M.O. Sustainable Water Management Practices in Agriculture: The Case of East Africa. Encyclopedia 2025, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axon, S. Unveiling Understandings of the Rio Declaration’s Sustainability Principles: A Case of Alternative Concepts, Misaligned (Dis)Connections, and Terminological Evolution. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nava, L.F.; Torres Bernardino, L.; Orozco, I. Crisis Water Management in Mexico. In The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Sustainable Resources and Ecosystem Resilience; Brears, R., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswald Spring, Ú. The water, energy, food and biodiversity Nexus: New security issues in the case of Mexico. In Addressing Global Environmental Challenges from a Peace Ecology Perspective; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 113–144. [Google Scholar]

- Maganda, C. The Politics of Regional Water Management: The Case of Guanajuato, Mexico. J. Environ. Dev. 2003, 12, 389–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosens, B.A.; Stow, C.A. Five. Resilience and water governance addressing fragmentation and uncertainty in water allocation and water quality law. In Social-Ecological Resilience and Law; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 142–175. [Google Scholar]

- Romano, O.; Akhmouch, A. Water Governance in Cities: Current Trends and Future Challenges. Water 2019, 11, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourad, K.A. A Water Compact for Sustainable Water Management. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).