Abstract

This study aims to investigate hydrogeochemical characteristics and groundwater quality in the Bashang Area in Chengde and to discuss factors controlling the groundwater quality. A total of 91 groundwater samples were collected and a fuzzy synthetic evaluation (FSE) method was used for assessing groundwater quality. Results show the groundwater chemistry in the study area is predominantly characterized by HCO3−-Ca type waters. Rock weathering processes dominate the hydrogeochemical processes within the study area, while also being influenced by evaporation and concentration effects. The results of the fuzzy evaluation indicate that 94.5% of groundwater samples are of good quality and suitable for drinking (Classes I, II, and III), while 5.5% are of poor quality and unsuitable for drinking (Class IV). Among these, bedrock fissure water exhibited superior quality. Within clastic rock pore water, elevated levels of NO3− and F− ions were observed in certain localized areas. The exceedance of NO3− concentrations stems from agricultural expansion, where the application of nitrogen fertilizers constitutes the primary driver of local nitrate pollution. Excessive F− levels correlate with the region’s indigenous geological background. Fluoride-bearing minerals such as fluorite and biotite are widely distributed throughout the study area. Intensive evaporation concentrates groundwater, while the region’s slow groundwater flow facilitates the accumulation and enrichment of F− within aquifers.

1. Introduction

Groundwater is a key part of the Earth’s hydrologic cycle and plays an irreplaceable role in the survival and development of human beings [1,2,3]. However, with the acceleration of industrialization and urbanization, the water environment is facing unprecedented challenges. The discharge of typical pollutants such as nutrients (e.g., nitrogen, sulfur, phosphorus, etc.), heavy metals, and new pollutants (e.g., microplastics, antibiotics) poses a serious threat to the water environment [4,5], as they are key components affecting human health [6]. Groundwater quality is one of the important factors to evaluate because some portion of groundwater may not meet up the adequate level to be utilized specifically for drinking purpose [7].

For a considerable period, numerous water quality assessment methodologies have emerged to enable precise monitoring of water conditions. Traditional approaches encompass the composite index method and single-factor evaluation techniques [8]. The composite index method quantifies overall water quality by constructing a composite index incorporating multiple water quality indicators. This approach comprehensively considers various factors, providing a relatively thorough assessment of water quality. However, the determination of indicator weights is subject to significant human interference, which can easily lead to biassed evaluation results [9,10]. The single-factor evaluation method classifies water quality based on the poorest individual indicator. While operationally straightforward and intuitive, highlighting the most unfavourable factor, it disregards the combined impact of other indicators. Consequently, evaluation outcomes tend to be overly conservative, failing to fully reflect the true state of water quality [11].

As environmental science research continues to advance, there is growing recognition of the profound complexity and uncertainty inherent in groundwater quality assessment. Water quality is not determined by a single factor but rather by the combined influence of physical, chemical, and biological elements. These factors are intertwined and undergo dynamic changes, rendering water quality conditions difficult to describe using simple deterministic models. The transition from ‘clean’ to ‘polluted’ is not instantaneous; numerous transitional states exist with blurred boundaries. Take chemical oxygen demand (COD) as an example: when approaching the threshold of a particular water quality category, minute concentration variations make it difficult to definitively assign its classification. This ambiguity poses significant challenges for traditional precise mathematical methods. Fuzzy mathematics emerges as a potent tool for addressing such complex, ambiguous problems. It transcends the binary logic limitations of traditional mathematics by introducing the concept of membership degrees, permitting elements to belong to multiple sets at varying levels. This enables the nuanced characterization of fuzzy boundaries within water quality classifications, quantifying ambiguous information to yield more realistic evaluation outcomes. Consequently, it provides a robust and reliable foundation for formulating scientifically sound water resource management and ecological conservation strategies [12,13].

In many European and American countries, the application of fuzzy mathematics in groundwater quality assessment commenced early and has developed rapidly. For instance, in the United States, large-scale river and lake water quality monitoring programmes employ fuzzy mathematics to construct refined water quality evaluation models. Through long-term, multi-point monitoring data collection, which comprehensively considers numerous factors such as flow velocity, water temperature, and microbial communities, fuzzy sets are employed to precisely define water quality grades across different seasons and regions. This provides crucial evidence for rational water resource allocation and the formulation of aquatic ecosystem conservation strategies [14]. Icaga et al. proposed a fuzzy logic-based surface water quality assessment index model, applied to Eber Lake water (in Turkey), demonstrating its feasibility [15]. Ocampo-Duque W et al. proposed a water quality assessment method based on a fuzzy inference system [16]. Domestic research on applying fuzzy mathematics to water quality evaluation continues to deepen and expand. On one hand, fuzzy comprehensive judgement methods are widely employed in the integrated assessment of major river systems. Researchers, considering practical factors such as industrial distribution within river basins, urban sewage discharge, and agricultural irrigation demands, selected key indicators including chemical oxygen demand (COD), ammonia nitrogen, and heavy metal content as evaluation factors. By rationally determining the weighting of each factor, they conducted comprehensive and dynamic assessments of water quality in basins such as the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers. This enabled timely detection of water quality trends, providing robust support for basin ecological governance [17]. Zhang et al. employed fuzzy mathematical methods to assess groundwater quality across different aquifers and urbanization levels within the Pearl River Basin [12], while Qian et al. utilized fuzzy mathematics to evaluate groundwater quality in the Hebei Plain [18].

The Bashang area of Chengde, situated at the confluence of agricultural and pastoral zones within a fragile ecological region, lies at the headwaters of the Luan River and upstream of the Miyun Reservoir. It serves as a water conservation functional zone for the Beijing region and an ecological support area for the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region. Functioning as Beijing’s natural ecological barrier and water source protection area, changes in the region’s natural elements—such as vegetation and water resources—directly impact the capital’s ecological environment and water security. The potential degradation of groundwater quality, particularly from geogenic contaminants like fluoride and anthropogenic inputs like nitrate, therefore poses a significant risk to this critical water source. In recent years, the area has faced ecological and geological challenges including varying degrees of lake and wetland shrinkage, soil erosion, and desertification around the Luan River basin. Consequently, this study aims to investigate the hydrogeochemical characteristics and groundwater quality status of the Bashang region, while exploring the key factors controlling groundwater quality in this area. A total of 91 groundwater samples were collected from the area. Piper diagrams and Gibbs plots were employed to analyze the hydrogeochemical characteristics of different aquifers, while the fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method was used to assess groundwater quality across these aquifers. Furthermore, principal component analysis was applied to identify the primary factors controlling groundwater chemical composition and quality within the study area.

2. Study Area

2.1. Geographical Conditions

The study area is situated in the Bashang region of Chengde, Hebei Province, belongs to Fengning County (Figure 1). It lies in the middle section of the northern agro-pastoral transition zone, forming part of China’s fragile northern agro-pastoral ecological belt. Located at the southern edge of the Inner Mongolia Plateau, it covers an area of 1471.56 km2. The region experiences a cold-temperate continental monsoon climate, characterized by persistently low annual temperatures. Winters are long and bitterly cold, while summers are cool and brief. The seasons are distinctly marked, with rainfall coinciding with the warm period and significant diurnal temperature variations. Summer maximum temperatures generally do not exceed 25 °C. The annual mean temperature is −1.2 °C, with an extreme minimum temperature recorded at −42.90 °C. The long-term average annual precipitation stands at 420 mm, exhibiting marked seasonal variation with uneven distribution throughout the year. Rainfall is concentrated in June, July, and August, accounting for approximately 65% of the annual total. This period features abundant rainfall, frequently accompanied by short-duration torrential downpours. Precipitation is scant from November to March, primarily occurring as snowfall. The long-term average measured annual evaporation stands at 1164 mm. Influenced by seasonal variations, monthly evaporation fluctuates considerably. From December to February, monthly evaporation averages below 50 mm, with a minimum of 32 mm. while monthly averages from May to July hover around 200 mm, peaking at 233 mm. Beyond seasonal influences, evaporation rates are significantly correlated with the prevalence of strong winds in the study area. The long-term average wind speed ranges from 1.9 m/s to 2.5 m/s, with gusts reaching up to 28 m/s. Winds exceeding force 6 occur on 69 days annually. The terrain predominantly consists of low volcanic rock hills and broad inter-hill valleys, generally arranged in a northwest-southeast orientation, interspersed with gentle slopes and volcanic hill areas. Elevations range between 1200 and 2000 m.

Figure 1.

Location map of the study area and sampling sites.

2.2. Geological and Hydrogeological Conditions

Based on hydrodynamic conditions and the distribution of aquifers and aquitards, groundwater within the region is primarily classified into three types: loose rock pore water, clastic rock fissure-pore water, and bedrock structural fissure water. The lithology of loose rock pore water aquifers predominantly consists of gravel, sandy pebbles, medium to coarse sand, medium to fine sand, and silt-fine sand. The total thickness of these aquifers generally ranges from 20 to 60 m, interbedded with two to three layers of sandy clay or clay, each 2 to 5 m thick. The lithology of clastic rock fissure-pore water aquifers is dominated by olivine basalt and andesite basalt. These aquifers predominantly overlie Cretaceous strata as rock caps, exhibiting primarily unconfined conditions with localized confined zones. Water yield is moderate to abundant. Bedrock structural fissure water is confined within Precambrian metamorphic rocks, Lower Proterozoic schists, and magmatic rock fractures of various ages. Water storage capacity is limited, with moderate water yield. Atmospheric precipitation remains the primary groundwater recharge source in the study area, followed by river water infiltration along riverbeds.

This heterogeneous hydrogeological setting, combined with the area’s climatic and land use patterns, forms the basis for the spatial variations in groundwater chemistry and quality investigated in this study.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Groundwater Sampling

A total of 91 groundwater samples in the study area were collected in August 2024, which corresponds to the wet season characterized by high rainfall and groundwater recharge. This single-season snapshot provides a valuable baseline of groundwater conditions but inherently limits the analysis of seasonal dynamics. For mobile pollutants like NO3−, wet-season concentrations may be influenced by dilution from rainfall or, conversely, by accelerated leaching from soils, and thus may not represent the annual peak or average conditions. Similarly, the concentrations of ions influenced by evaporation (e.g., F−) might be more pronounced in the dry season. The findings should therefore be interpreted as representative of the wet-season conditions. Sampling primarily targeted pore water from loose rock formations, with very few wells collecting water from bedrock structural fractures. A total of 88 samples of loose rock pore water and 3 samples of bedrock structural fracture water were collected, distributed uniformly across the study area (Figure 1). In order to ensure samples rep-resenting the in situ conditions were collected after pumping at least 3 well volumes or 20 min. Samples were filtered through 0.45 µm membrane filters to remove suspended solids in the field. Three bottles were used to store groundwater for the analysis of chemical components. Groundwater in a 200 mL brown glass bottle was used to analyze sulfide (S2−), while two 500 mL polyethylene bottles were used to store groundwater for the analysis of trace elements and other inorganic chemicals. One bottle used for trace elements analysis was acidified with nitric acid to a pH of less than 2. All samples were stored at 4 °C until laboratory procedures could be performed.

All analyses were conducted at the Groundwater, Mineral Water, and Environmental Monitoring Center of the Institute of Hydrogeology and Environmental Geology, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences. Field pH measurements were performed using a multi-parameter portable meter (HANNA, Shanghai, China). Bicarbonate (HCO3−) and carbonate (CO32−) concentrations were determined via volumetric titration, while total dissolved solids (TDS) were measured gravimetrically. Total hardness (TH) and chemical oxygen demand (COD) were analyzed using EDTA titration and the potassium dichromate titration method, respectively. Major cations (including Fe, Al, and Mn) were quantified by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-AES; ICAP6300, Thermo, New York, NY, USA). Trace elements (As, Pb, Hg, Cd, Cr(VI), Se, Ni, Ba, Zn, and Al) were analyzed using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS; Agilent 7500ce, Tokyo, Japan). Sulfide (S2−) was measured iodometrically, and ammonium (NH4+) along with other anions (NO3−, SO42−, Cl−, NO2−, F−, I−) were analyzed by ion chromatography (IC; Shimadzu LC-10ADvp, Kyoto, Japan). To ensure data quality, all groundwater samples were analyzed in triplicate. Standards and blanks were routinely inserted into sample batches, and instrument drift corrections were applied throughout the analysis. The relative errors for all measured indicators were maintained within ±5%.

3.2. Fuzzy Synthetic Evaluation (FSE) Method

In this study, a fuzzy membership function was used to assess groundwater quality according to the groundwater quality standards of China (General administration of quality supervision inspection and quarantine of the people’s republic of China [19]. Linear membership functions are in Equation (1). Fuzzy sets and fuzzy optimization provide a useful technique in addressing the imprecision of groundwater quality assessment [20]. To reduce the complexity of the model, the linear membership functions are used as follows:

where rij indicates the fuzzy membership of indicator i to class j, every indicator is characterized by five classes (I, II, III, IV, V) according to the groundwater quality standards of China [19], Ci stands for analytical value of groundwater quality indicator i, Sij stands for the allowable value of groundwater quality indicator. The fuzzy membership matrix R consists of groundwater quality indicators and classes.

The weight of water quality indicator is expressed as

where Wi is the weight of water quality indicator i, Ci is the analytical value of water quality indicator i, and Si is the arithmetic mean of allowable values of each class. The normalized weight of each indicator is calculated by the Formula (3)

where αi is the normalized weight of indicator i, is the sum of weight to all water quality indicators. The fuzzy A consists of weight of each water quality indicator. The water quality assessment by fuzzy membership is based on the matrix B,

The fuzzy B is the matrix of membership to each water quality class. Water sample is classified to the class with the maximize membership. Other details related to the FSE method could be found in [13,18,20].

3.3. Principal Components Analysis (PCA)

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is an effective method for reducing dimensionality, transforming numerous variables into a smaller number of principal components (PCs) through linear combinations [21]. In this study, PCA was employed to reduce the number of indicators and extract the primary influencing factors contributing to poor groundwater quality. These indicators were identified as key parameters with high loadings within the same principal component when combined with water quality assessment results. Furthermore, PCA was employed to extract groups of highly correlated variables, enabling inference of fundamental natural processes and/or anthropogenic sources governing groundwater quality [22]. Prior research indicates that parameters exhibiting positive loadings within the same principal component typically signify shared origins or analogous geochemical behaviour [23,24]. During analysis, we employed the Varimax method for principal component rotation, retaining only principal components with eigenvalues greater than 1 for subsequent analysis. To assess relationships between principal components and individual indicators, this study selected the loading with the largest absolute value in the rotated component matrix as the representative affiliation for each indicator. All PCA operations were performed using SPSS® software (version 23.0).

3.4. Spatial Analysis and Land Use Correlation

To elucidate the spatial relationship between groundwater contaminants and land use, the sampling points where NO3−-N and F− concentrations exceeded allowable limits were mapped using ArcGIS 10.8. The spatial distribution of these exceedance points was qualitatively compared against the general land use pattern of the Bashang area, which is characterized by widespread cropland (predominantly rain-fed agriculture) interspersed with grassland and forest in hilly regions, as derived from local land use surveys and satellite imagery interpretation. This comparative analysis aimed to identify if clusters of contamination correlate with specific land use types, such as intensive agricultural valleys versus forested uplands.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Characteristics of Groundwater Chemistry

The statistical analysis results for groundwater chemical parameters in the study area are presented in Table 1. The groundwater chemistry predominantly exhibits a HCO3−-Ca type. Total dissolved solids (TDS) ranged from 91.0 to 799.1 mg/L, with total hardness (TH) values between 49.2 and 580.6 mg/L (mean: 224 mg/L). Only four well samples exceeded the permissible total hardness limit (450 mg/L). pH values ranged from 6.59 to 8.08, with over 20% of groundwater samples exhibiting pH < 7 indicating acidity. The average pH was 7.282, indicating the groundwater is generally weakly alkaline. Both maximum and minimum pH values remained within Class III water quality standards. TDS values ranged from 91 to 800 mg/L. The substantial variation in TDS levels indicates that groundwater chemistry is influenced by multiple factors. With all TDS readings below 1000 mg/L, the groundwater in this area is suitable for drinking.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistical table of groundwater sample indicators in the study area.

The order of cation dominance in groundwater is as follows: Ca2+ > Na+ > Mg2+ > K+. Ca2+ is the predominant cation in this region, with concentrations ranging from 15.6 to 181.7 mg/L and an average concentration of 73.3 mg/L (Table 1). The relatively low Ca2+ concentration in this area is attributed to groundwater traversing rock formations with comparatively scarce calcium-bearing minerals, consistent with the region’s character as a low-lying hilly terrain dominated by siliceous igneous rocks. The second predominant cation is Na+, with concentrations in the study area ranging from 6.58 to 54.76 mg/L. Na+ plays a crucial role as a salinity indicator in groundwater; originating from various processes including ion exchange within glauconite and clay minerals, as well as feldspar weathering [24]. All samples met the Class I standard limits for Na+ specified in the People’s Republic of China Groundwater Quality Standards [19]. Mg2+ and K+ concentrations in the study area ranged from 1.49 to 30.82 mg/L and 0.41 to 16.68 mg/L, respectively.

The order of predominance for anions in groundwater is HCO3− > SO42− > Cl− > NO3− > F− > NO2−. HCO3− is the predominant anion, varying between 53.05 and 472.63 milligrams per litre, with an average of 189.87 milligrams per litre. The concentration range for SO42− is 4.65 to 113.14 milligrams per litre, with an average concentration of 23.35 milligrams per litre. Cl− content ranged from 3.25 to 141.49 mg/L (average 21.67 mg/L). Neither SO42− nor Cl− concentrations exceeded regulatory limits in any groundwater sample. The maximum NO3− concentration (expressed as N) in the study area groundwater was 60.58 mg/L, with an average of 10.72 mg/L, indicating an overall elevated level. Among 91 groundwater samples, 14 exceeded the standard, representing a non-compliance rate of 15.38%, which is a relatively serious situation. The maximum, minimum, and average concentrations of F− were 1.94, 0.113, and 0.58 mg/L, respectively. In 15.38% of samples, the F− concentration exceeded the permissible limit for Class III standards in groundwater quality standards.

At certain sampling points within this region, heavy metals Mn and Fe exceeded permissible limits. The coefficient of variation (CV) for Mn and Fe typically reflects spatial variability in water chemistry indicators; a higher CV indicates more pronounced spatial differentiation. Notably, K+, NO3− (expressed as N), and Cl− exhibited substantial spatial variability (CV > 100%), which, beyond natural conditions, strongly suggests a significant influence from anthropogenic activities. The patchy distribution of these ions likely stems from localized sources such as agricultural fertilization (potassium and nitrogen fertilizers) and associated irrigation return flows, reflecting pronounced human activity impacts [25]. K+, NO3− (expressed as N), NO2− (expressed as N), and Cl− exhibited substantial spatial variability, indicating influence from natural conditions. This may stem from severe local ion enrichment due to agricultural fertilization (potassium fertilizers), reflecting pronounced human activity impacts [25]. The coefficients of variation for heavy metal concentrations—Fe, Mn, Al, Cr6+, and As—exceeded 100%. Given that the coefficient of variation inherent to the heavy metal analytical methods themselves remained below 10%, this indicates substantial variation in heavy metal concentrations across sampling points.

The Piper three-line diagram is a commonly employed method for hydrochemical analysis, providing valuable insights into the geochemical evolution of groundwater and its hydrochemical characteristics, while comprehensively representing groundwater hydrochemical types [26,27,28]. As illustrated in Figure 2, Anions in groundwater predominantly distributed within Zone E, with 96% of water samples falling within this zone, indicating that HCO3− is the predominant anion under study. Among cations, only one water sample point fell within Zone B, indicating no single cation predominates; 99% of cations were distributed in Zone A, confirming Ca2+ as the dominant cation in the study area. The prevalence of Ca2+ in groundwater suggests carbonate minerals and basalt weathering may be the primary factors governing groundwater chemistry.

Figure 2.

Hydrogeochemical facies of groundwater in the study area.

The rhombic diagram illustrates the overall hydrochemical characteristics. Analyzing the hydrochemical types of the study area according to the Shukarev classification system, sampling points were predominantly distributed across Zones 1, 2, and 3 of the Piper diagram. Results indicate groundwater types comprising Ca-Mg-HCO3 (96%), Ca-Mg-Cl (2%), and Ca-Cl (2%), with Ca-HCO3 predominating overall. The minor but present Ca-Mg-Cl and Ca-Cl types, deviating from the dominant weathering-controlled facies, often signify an influence from external sources, potentially including anthropogenic contamination (e.g., from agricultural or domestic waste) which can introduce Cl− and other ions, altering the natural hydrochemical signature.

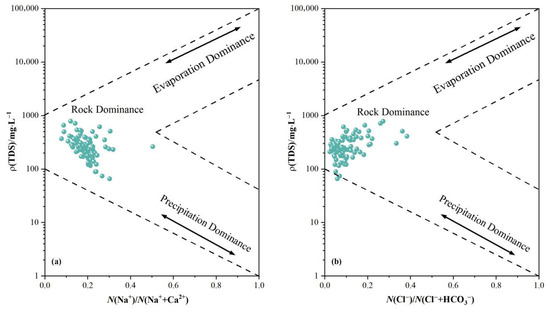

Gibbs diagrams may be employed to analyze groundwater chemical formation mechanisms within the study area, categorizing them into three types: evaporation-concentration, rock weathering, and atmospheric precipitation. The distribution of data points visually indicates which mode governs the water body. As illustrated in Figure 3. The majority of groundwater samples cluster within the rock weathering-dominated zone, distant from the atmospheric precipitation endpoint, indicating minimal influence from atmospheric precipitation. This confirms that rock weathering governs the hydrogeochemical processes within the study area. A minority of samples exhibit an upward shift, suggesting some influence from evaporative concentration, though this remains non-dominant. One sample point lies outside the Gibbs model, potentially due to anthropogenic interference (such as contamination from agricultural or domestic sources) or intense cation exchange processes. Compared to Figure 3a, the water body locations in Figure 3b are generally shifted to the left, indicating a smaller Cl−/(Cl− + HCO3) ratio relative to the Na+/(Na+ + Ca2+) ratio. This relates to ion exchange adsorption, as Ca2+ and Mg2+ in the water undergo exchange adsorption with Na+ in rock minerals, thereby relatively increasing the proportion of Na+ in the water body.

Figure 3.

Gibbs diagram of groundwater samples in the study area. ((a) Cation proportion; (b) Anion proportion).

Based on logarithmic scatter plots of Ca2+/Na+ versus HCO3−/Na+ and Ca2+/Na+ versus Mg2+/Na+ in hydrochemical data, it is possible to determine whether hydrochemical components under solution conditions originate from silicate rocks, evaporite rocks, or carbonate rocks [21]. In Figure 3, groundwater in the study area predominantly clusters near the silicate rock endpoint, distant from both the evaporite and carbonate rock endpoints. This indicates groundwater is primarily influenced by silicate rock dissolution, with minimal contribution from evaporite or carbonate rock dissolution.

4.2. Distribution of Groundwater Quality

Compared to standards for groundwater quality in China [19], proportions of ground-water samples with concentrations of chemical components exceeded allowable limits (PEAL) for drinking purposes are shown in Table 2. Of the 91 samples tested, the majority met Class III water standards for most parameters. The primary exceedances were for NO3−, TH, F− and Mn. NO3− contamination was particularly severe in certain areas, with the highest exceedance reaching 13.4 times the standard (Y3-005). Numerous outlets also exceeded F−, potentially linked to regional geological conditions.

Table 2.

Statistics for proportions of groundwaters with chemical concentrations exceeded allow- able limits.

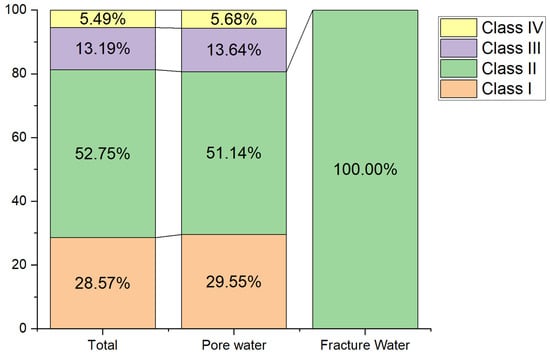

Groundwater quality was assessed using the FSE method and categorized into five classes according to China’s groundwater quality standards [19]. Within the Bashang area of Chengde, groundwater samples comprised 28.57% Class I, 52.75% Class II, 13.19% Class III, and 5.49% Class IV water; no Class V water was distributed within the study area. Among the total groundwater samples, 94.51% exhibited good quality and were potable (Classes I, II, and III), while 5.49% were of poorer quality and unfit for drinking (Class IV) (Figure 4). This study provides qualitative rather than quantitative groundwater quality results, with only approximately 91 samples collected within the study area. Furthermore, groundwater quality results were based on concentrations of 27 inorganic chemicals and 4 organic chemicals identified in this study.

Figure 4.

Statistical Results of Groundwater Quality Assessment in various aquifers.

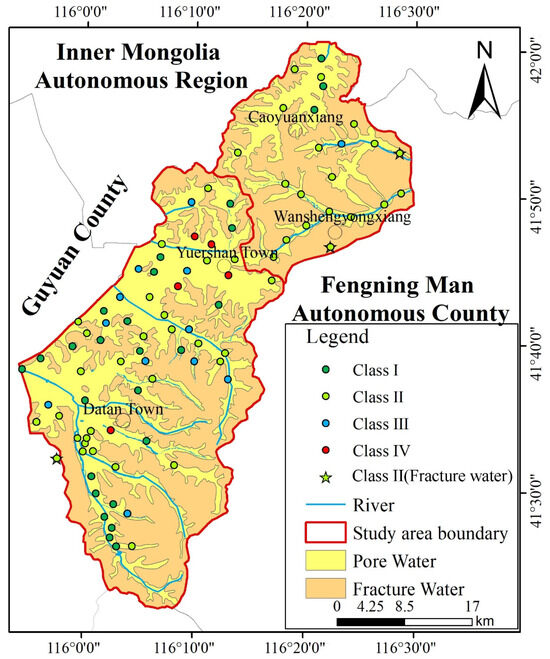

Based on groundwater types within the study area, samples can be categorized into two groups: loose rock pore water and bedrock structural fracture water. Only three samples were obtained from bedrock fracture water, all of which were classified as Class II water quality (as is shown in Figure 5). This indicates that bedrock fracture water throughout the study area is potable. Regarding loose rock pore water, samples I, II, III, and IV accounted for 30%, 51%, 14%, and 6%, respectively. The potability rate for loose rock pore water samples reached 95%. Overall, groundwater quality within the study area is generally favourable.

Figure 5.

Groundwater quality result in various aquifers.

4.3. Factors Controlling Groundwater Quality

PCA is a multivariate statistical method capable of analyzing multiple indicators within a single system. By reducing dimensionality to simplify the number of indicators, it holds significant importance for datasets with numerous research variables. In this study, the PCA was used to analyze the factors controlling groundwater quality in the study area. Here, parameters in the PCA include pH, major ions, and exceeding indicators that concentrations in one or more groundwater samples are higher than their allowable limits. As shown in Table 3, groundwater quality was mainly controlled by six factors.

Table 3.

Principal component (PC) loadings for groundwater chemical parameters.

PC1 (factor 1) is primarily composed of TDS, TH, Ca2+, Mg2+, Cl−, HCO3−, and SO42−, with a contribution rate of 39.29%. This reflects varying degrees of hydrogeochemical interaction between groundwater and minerals during the runoff process. Ions such as TH, Ca2+, Mg2+, Cl−, HCO3−, and Na+ primarily originate from water-rock interactions, largely associated with natural processes like mineral dissolution and evaporative concentration [26]. The study area is predominantly controlled by rock weathering, influenced by the dissolution of minerals such as carbonates and silicate gypsum. While PC1 overwhelmingly represents natural geogenic processes, it is important to note that ions like SO42− and Cl− can also have anthropogenic sources, such as fertilizers and wastewater, which may contribute to their loadings in this component. Consequently, PC1 is interpreted as representing the combined effect of water-rock interactions on groundwater quality.

PC2 (factor 2) is primarily composed of F− and As. As shown by the high exceedance rate in Table 1 (15.38%). The increase in F− is mainly influenced by sedimentary environments and hydrogeological conditions. Field investigations reveal widespread distribution of fluoride-bearing minerals such as fluorite and biotite in the study area. Over extended geological periods, the weathering of these rocks has provided groundwater with a stable and abundant source of fluoride. This constitutes the material basis for the formation of high-fluoride groundwater in this region. The study area exhibits a temperate semi-arid continental monsoon climate, where annual evaporation exceeds precipitation. This intense evaporation concentrates groundwater, leading to relatively elevated fluoride ion concentrations. This represents a key driver for fluoride enrichment [29,30,31]. The Bashang area predominantly comprises inland river headwaters and intermontane basins where groundwater flow is sluggish, with evaporation being the primary discharge mechanism. Concurrently, the average groundwater pH in this region is 7.28, indicating a weakly alkaline environment. Such alkaline conditions promote the release of fluoride from groundwater, contributing to F− exceedances in certain localized areas [28]. Arsenic (As) contamination is primarily associated with the weathering and release of arsenic-rich sulphides.

PC3 (factor 3) is primarily composed of Fe and Al, likely originating from iron ore deposits distributed within the study area. Fe is a characteristic contaminant of iron tailings, exhibiting elevated concentrations in mine water. Aluminum is a constituent element of iron ore. As mine water flows through mining areas and tunnels, it may dissolve and transport minerals, suspended solids, and potential contaminants, thereby altering water quality and leading to elevated concentrations of certain elements, such as aluminum [22,24]. This suggests that PC3 may be associated with mining operations.

PC4 and PC5: Agricultural Influence Factors. PC4 (factor 4) exhibits potassium (K+) as its primary loading factor, while PC5 (factor 5) is predominantly composed of NO3−. The strong association of these two ions in separate but related factors clearly highlights the significant imprint of agricultural activities on the groundwater chemistry. K+ is generally recognized as originating from natural minerals, yet its readily adsorbable nature to clay minerals and high availability for plant uptake result in relatively low concentrations within groundwater under natural conditions. The elevated levels and high spatial variability of K+ (Table 1) therefore point to an external source. Given the extensive distribution of cultivated land within the study area, K+ likely originates from the substantial application of potassium-based fertilizers. Similarly, the dominance of NO3− in PC5, coupled with the finding that 15.38% of samples exceeded the standard (Table 1), unequivocally identifies agricultural practices as a primary driver of groundwater chemical evolution in affected areas. Nitrate in the study area’s groundwater primarily originates from the application of nitrogenous fertilizers, with additional contributions from manure and soil organic nitrogen [24]. Through irrigation or rainfall leaching, these agrochemicals infiltrate the aquifer, directly influencing the ion composition by elevating concentrations of K+, NO3−, and also contributing to Cl− (as seen in PC1) and other associated ions.

PC6 (factor 6) is predominantly composed of manganese (Mn). Mn is governed by geological background conditions. The bedrock in the study area is primarily volcanic rock, with high Mn content in the parent material. Furthermore, Mn-bearing components have been deposited throughout all Quaternary periods within the watershed. Consequently, F6 reflects the influence of the geological environment.

4.4. Spatial Correlation of Contaminants with Land Use and Geology

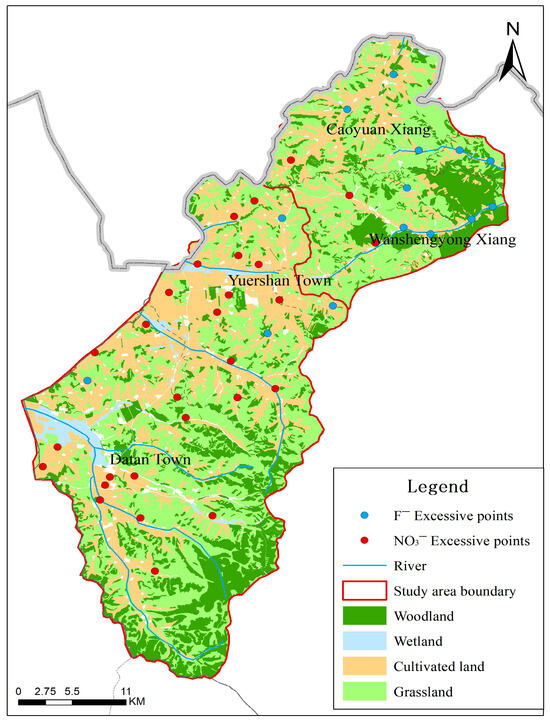

The spatial patterns of NO3− and F− exceedances, as visualized in Figure 6, provide critical insights that refine our understanding of their controlling factors beyond the generalized PCA results. For nitrate (NO3−), the exceedance points show a clear and non-random spatial clustering. These clusters are predominantly located within the broad, flat valleys of the study area. These valleys coincide with the region’s primary agricultural zones, characterized by cultivated cropland. This strong spatial correlation provides direct visual and geographical evidence supporting the interpretation of PC4 and PC5 as an “Agricultural Influence Factor.” The mechanism is straightforward: the application of nitrogenous fertilizers in these cultivated valleys leads to leaching, which is facilitated by the permeable nature of the loose rock pore aquifers prevalent in these areas. In contrast, sample points from bedrock structural fissure water (can be seen in Figure 5) showed no NO3− exceedance, further corroborating the link between nitrate pollution and valley-based agriculture. For fluoride ions (F−), their spatial distribution pattern differs from that of NO3−. Exceedance points are not densely clustered within cultivated land areas, but are primarily distributed in low-lying areas of mountainous river valleys surrounding fluorite mines. This distribution aligns with a geogenic, geology-controlled origin. The presence of fluoride-bearing minerals (e.g., fluorite, biotite) in the host volcanic and metamorphic rocks provides the primary source. The exceedances occur where groundwater flow paths have interacted extensively with these minerals, and where hydrogeochemical conditions (e.g., high pH, long residence time, strong evaporation as indicated in the Gibbs diagram) favour fluoride dissolution and concentration. The lack of a clear correlation with agricultural land use strengthens the conclusion that F− enrichment is primarily a natural background issue, as indicated by PC2.

Figure 6.

Land Use and Spatial distribution of groundwater sampling points and exceedances of NO3−-N and F− limits.

This spatial analysis underscores a key management insight: the risks from NO3− and F− are spatially distinct. Nitrate pollution is a point-of-source risk concentrated in and downstream of agricultural valleys, where targeted fertilizer management and protection of shallow aquifers are most needed. Fluoride contamination, conversely, is a point-of-use risk that can appear across wider areas dictated by geology and groundwater chemistry, necessitating water quality testing and treatment at the wellhead.

4.5. Implications for Water Resource Management

The identification of specific zones with elevated F− and NO3− concentrations, as revealed by this study, carries significant implications for water resource management, particularly given the Bashang area’s critical role as a water source functional zone for Beijing and the wider Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region. While the overall groundwater quality is good, the localized pollution requires targeted strategies to safeguard water security.

Firstly, for the geogenic F− contamination, management efforts should focus on identifying and delineating high-fluoride groundwater zones. In these delineated areas, the direct extraction of groundwater for drinking purposes should be restricted or prohibited. Public awareness campaigns should be implemented to inform local residents of the health risks associated with high fluoride intake. Alternatively, water supply authorities should consider developing centralized water treatment facilities equipped with defluoridation technologies (e.g., adsorption or precipitation methods) or seeking alternative, low-fluoride water sources to supply affected communities.

Secondly, to address the anthropogenic NO3− pollution stemming from agricultural activities, integrated agricultural-environmental policies are essential. This includes promoting precision agriculture to optimize the timing and quantity of nitrogen fertilizer application, thereby reducing nutrient leaching. Encouraging the use of slow-release fertilizers and the adoption of environmentally friendly farming practices should be prioritized. Furthermore, the construction and maintenance of sewage treatment facilities in rural settlements should be enhanced to prevent direct contamination from manure and domestic wastewater, which are additional sources of nitrogen.

Finally, a robust, long-term groundwater quality monitoring network should be established and maintained. This network should specifically target the parameters identified as key concerns in this study (F−, NO3−, and also Mn, Fe/Al where relevant). Regular monitoring will enable the early detection of pollution trends, evaluate the effectiveness of implemented management measures, and provide a scientific basis for adaptive water resource management policies. By integrating these targeted management strategies, the ecological function and water source security of the Bashang area can be effectively preserved for the long term.

4.6. Limitations and Considerations for Seasonal Variation

While this study provides a comprehensive snapshot of groundwater quality in the Bashang area during the wet season, the lack of multi-temporal sampling is a recognized limitation that affects the interpretation of certain results. Groundwater chemistry is not static and can exhibit significant seasonal fluctuations driven by variations in recharge, evaporation, and anthropogenic activity.

- Nitrate (NO3−): The concentrations reported here reflect conditions following the period of summer rainfall. This could lead to either an under- or over-estimation of the annual pollution risk. On one hand, heavy rainfall can dilute nitrate concentrations in shallow aquifers. On the other hand, it can facilitate the rapid leaching of fertilizers from the root zone into the groundwater, potentially causing a “flush” of high nitrate levels [32,33]. Without dry-season data, the persistence and potential concentration of nitrate pollution during periods of lower groundwater flow remain unknown.

- Fluoride (F−): The observed F− exceedances are linked to fluoride-bearing minerals, evaporation and Hydrogeological conditions. In arid and semi-arid regions, intense evaporation is the key factor driving the concentration and enrichment of fluoride ions (F−) in groundwater, particularly in shallow aquifers. During the dry season, the absence of precipitation for dilution coupled with persistent evaporation causes F− concentrations to peak. Conversely, rainfall infiltration during the wet season significantly dilutes F− concentrations within groundwater [34,35,36]. The process of evaporative concentration is typically strongest during the dry season when temperatures are higher and precipitation is low. Therefore, the F− concentrations reported in this wet-season study might represent lower bounds, with potentially more severe exceedances occurring in the dry season as the water table declines and evaporation intensifies. However, some literature indicates that F− concentrations may be higher during the rainy season than the dry season, as substantial rainfall infiltration reduces groundwater pH. At slightly lower pH levels, fluoride ions adsorbed onto the surfaces of fluoride-bearing minerals such as fluorite and clay minerals are more readily desorbed into the water body, thereby increasing F− concentrations [37,38,39].

- Overall Assessment: The fuzzy synthetic evaluation indicating that 94.5% of samples are of good quality may be optimistic if dry-season concentrations of NO3−, F−, and other parameters (e.g., Mn, TDS) increase significantly. Conversely, the wet season might present the greatest risk for bacterial or organic contamination. Therefore, the groundwater quality classification and the identified spatial patterns of pollution should be viewed as specific to the wet season. The true annual risk and the effectiveness of proposed management strategies can only be accurately assessed through long-term monitoring that captures the full hydrological cycle.

5. Conclusions

Hydrogeochemical characteristics and groundwater quality in pore water in loose rock formation sand and bedrock structural fracture water of the Bashang area of Chengde were investigated. The groundwater chemistry in the research area is predominantly characterized by HCO3−-Ca type waters. Rock weathering processes dominate the hydrogeochemical processes within the study area, while also being influenced by evaporation and concentration effects.

The results of the fuzzy evaluation indicate that 94.5% of groundwater samples are of good quality and suitable for drinking (Classes I, II, and III), while 5.5% are of poor quality and unsuitable for drinking (Class IV). Among these, bedrock fissure water exhibited superior quality. Within clastic rock pore water, elevated levels of NO3− and F− ions were observed in certain localized areas but with distinct spatial patterns. NO3− exceedances show a strong spatial correlation with cultivated valleys, providing clear evidence that agricultural expansion and fertilizer application constitute the primary driver of this localized pollution. In contrast, F− exceedances are more widely and diffusely distributed, correlating with the region’s indigenous geological background and hydrogeochemical conditions rather than land use.

The findings underscore the need for differentiated groundwater management strategies in the Bashang area. Protecting this critical water source requires targeted measures, including restricting groundwater use in identified high-fluoride zones, implementing sustainable agricultural practices to mitigate nitrate leaching, and establishing a long-term monitoring program to track water quality trends.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.T. and Z.C.; Methodology, Y.D., H.Z. and S.Q.; Software, H.Z. and S.Q.; Validation, S.Q.; Formal analysis, W.X. and X.T.; Investigation, Y.D., H.Z. and S.Q.; Resources, W.X., X.T. and Z.C.; Data curation, W.X., Y.D., X.T. and H.Z.; Writing—original draft, W.X. and S.Q.; Writing—review & editing, Z.C.; Visualization, Y.D.; Supervision, X.T. and Z.C.; Project administration, Z.C.; Funding acquisition, Y.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Key Projects of the Department of Natural Resources of Hebei Province grant number 13000024P00F2D4105681.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to personal privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sharma, K.; Raju, N.J.; Singh, N.; Sreekesh, S. Heavy metal pollution in groundwater of urban Delhi environs: Pollution indices and health risk assessment. Urban Clim. 2022, 45, 101233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subba Rao, N.; Dinakar, A.; Sun, A. Estimation of groundwater pollution levels and specific ionic sources in the groundwater, using a comprehensive approach of geochemical ratios, pollution index of groundwater, unmix model and land use/land cover—A case study. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2022, 248, 103990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramamoorthy, A.; Abhishek, B.; Zhang, Z.H.; Nusrat, N.; Li, F.J.; Zhang, C.J.; Huang, X.Z. Quantifying climate variation and associated regional air pollution in southern India using Google Earth Engine. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 909, 168470. [Google Scholar]

- Tanmoy, B.; Subodh, C.P.; Dipankar, R.; Asish, S.; Manisa, S.; Abu, R.M.; Towfiqul, I.; Aznarul, I.; Romulus, C. Evaluation of groundwater contamination and associated human health risk in a water-scarce hard rock-dominated region of India: Issues, management measures and policy recommendation. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 23, 101039. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, A.; Deshwal, A.; Priyadarshi, M.; Pathak, S.; Sambandam, G.; Chand, S.; Shukla, A.K. Landfill leachate analysis from selected landfill sites and its impact on groundwater quality, New Delhi, India. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 27, 12537–12562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.-J.; Liu, Y.; Nazir, N.; Ayyamperumal, R. Evaluating the influencing factors of groundwater evolution in rapidly urbanizing areas using long-term evidence. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2024, 136, 103728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, T.; Li, C.; Wang, Z.; Qi, C.; Chen, G.; Fu, Y.; Su, Q.; Xu, X.; Liu, W.; Yu, H. Hydrochemical characteristics and quality assessment of groundwater in Guangxi coastal areas, China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 188, 114564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, R.; Wu, X.; Mu, W. Hydrogeochemistry, identification of hydrogeochemical evolution mechanisms, and assessment of groundwater quality in the southwestern Ordos Basin, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 901–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkoyunlu, A.; Akiner, M.E. Pollution evaluation in streams using water quality indices: A case study from Turkey’s Sapanca Lake Basin. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 18, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, V.; Kamboj, N.; Bisht, A. An overview of water quality indices as promising tools for assessing the quality of water resources. Adv. Environ. Pollut. Manag. Wastewater Impacts Treat. Technol. 2020, 1, 188–214. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, W.; Wu, J.; Li, Z.; Cui, N.; Cheng, S. Water quality assessment of an urban river receiving tail water using the single-factor index and principal component analysis. Water Supply 2019, 19, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Huang, G.; Hou, Q.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q. Groundwater quality in the Pearl River Delta after the rapid expansion of industrialization and urbanization: Distributions, main impact indicators, and driving forces. J. Hydrol. 2019, 577, 124004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Huang, G.; Sun, J.; Jing, J.; Zhang, Y. A new evaluation method for groundwater quality applied in Guangzhou region, China: Using fuzzy method combining toxicity index. Water Environ. Res. 2016, 88, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanapathi, T.; Thatikonda, S. Fuzzy-based regional water quality index for surface water quality assessment. J. Hazard. Toxic Radioact. Waste 2019, 23, 04019010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Icaga, Y. Fuzzy evaluation of water quality classification. Ecol. Indic. 2007, 7, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocampo-Duque, W.; Ferre-Huguet, N.; Domingo, J.L.; Schuhmacher, M. Assessing water quality in rivers with fuzzy inference systems: A case study. Environ. Int. 2006, 32, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Zhang, Y.X.; Jing, Q.; Ning, G.F. Research on Groundwater Quality Evaluation with Fuzzy Mathematics. Adv. Mater. Res. 2012, 347–353, 2287–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Hou, Q.; Wang, C.; Zhen, S.; Yue, C.; Cui, X.; Guo, C. Hydrogeochemical Characteristics and Groundwater Quality in Phreatic and Confined Aquifers of the Hebei Plain, China. Water 2023, 15, 3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Administration of Quality Supervision Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China (GAQSIQPRC). Standard for Groundwater Quality; Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Song, X.; Zhang, Y.; Han, D.; Tang, C.; Yu, Y.; Ma, Y. Hydrochemical characteristics and water quality assessment of surface water and groundwater in Songnen Plain, Northeast China. Water Res. 2012, 46, 2737–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z. Groundwater is important for the geochemical cycling of phosphorus in rapidly urbanized areas: A case study in the Pearl River Delta. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 260, 114079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Hou, Q.; Han, D.; Liu, R.; Song, J. Large scale occurrence of aluminium-rich shallow groundwater in the Pearl River Delta after the rapid urbanization: Co-effects of anthropogenic and geogenic factors. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2023, 254, 104130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.; Chen, Z.; Liu, F.; Sun, J.; Wang, J. Impact of human activity and natural processes on groundwater arsenic in an urbanized area (South China) using multivariate statistical techniques. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 13043–13054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.; Zhang, M.; Liu, C.; Li, L.; Chen, Z. Heavy metal(loid)s and organic contaminants in groundwater in the Pearl River Delta that has undergone three decades of urbanization and industrialization: Distributions, sources, and driving forces. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 635, 913–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.; Guo, H.; Zhan, Y. Groundwater hydrochemical characteristics and processes along flow paths in the North China Plain. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2013, 70–71, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Guo, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, R.; Hou, C.; Shao, J.; Cui, Y. Evolution of groundwater major components in the Hebei Plain:Evidences from 30-year monitoring data. J. Earth Sci. 2014, 25, 563–574. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Li, M.; Ren, X.; Wang, C.; Yang, X.; Hao, Y.; Dong, S.; Yu, R. Unveiling sources and fate of sulfate in lake-groundwater system combined Bayesian isotope mixing model with radon mass balance model. Water Res. 2025, 282, 123648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, S.; Wang, J.; Zhang, K.; Fan, M.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, Z.; Gomes, H.; Gomes, R.; Duan, L.; et al. Fate and risks of potentially toxic elements associated with lacustrine groundwater discharge: Quantification, modeling, and biogeochemistry. Environ. Int. 2025, 202, 109707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Dong, D.; Lv, S.; Ding, J.; Yan, M.; Han, G. Spatial evolution analysis of groundwater chemistry, quality, and fuoride health risk in southern Hebei Plain, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 61032–61051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Hao, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Yin, S.; Qin, L.; Li, X. Investigating sources, driving forces and potential health risks of nitrate and fluoride in groundwater of a typical alluvial fan plain. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 802, 149909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, S.; Ren, X.; Zhao, Y.; Mao, H.; Dong, S.; Yu, R. Unveiling origin and enrichment of fluoride in the Daihai Lake basin, China, using a hybrid hydrochemical and multi-isotopic method. J. Hydrol. 2025, 656, 133030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Su, Y.; Zhang, R.; Xu, X.; Li, J. Spatio-Temporal Variations in Nitrate Sources and Transformations in the Midstream of the Yellow River Determined Based on Nitrate Isotopes and Hydrochemical Compositions. Water 2024, 16, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Wu, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, Q.; Lei, R.; Li, K. Identifying seasonal sources and processes controlling nitrate in a typical reservoir-type headwater watershed of eastern china using stable isotopes. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 386, 109615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaji, E.; Sarath, K.V.; Santosh, M.; Krishnaprasad, P.K.; Arya, B.K.; Babu, M.S. Fluoride contamination in groundwater:a global review of the status, processes, challenges, and remedial measures. Geosci. Front. 2024, 15, 101734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, C.; Wang, Y.; He, K.; Gui, H. Seasonal distribution of deep groundwater fluoride, geochemical factors and ecological risk for irrigation in the Shendong mining area, China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 1024797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvam, S. A preliminary investigation of lithogenic and anthropogenic influence over fluoride ion chemistry in the groundwater of the southern coastal city, tamilnadu, india. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2015, 187, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrajith, R.; Diyabalanage, S.; Dissanayake, C.B. Geogenic fluoride and arsenic in groundwater of sri lanka and its implications to community health. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 10, 100359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreedevi, P.D.; Ahmed, S.; Reddy, D.V. Mechanism of fluoride and nitrate enrichment in hard-rock aquifers in gooty mandal, south india. Environ. Process. 2017, 4, 625–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.; Zhai, P.; Shi, L.; Qu, X.; Bilal, A.; Han, J.; Yu, X. Distribution, enrichment mechanism and risk assessment for fluoride in groundwater: A case study of Mihe-Weihe River Basin, China. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2023, 17, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).