Abstract

Groundwater is one of the main sources of water supply in tropical developing countries; however, its integrated management is often constrained by limited hydrogeological information and increasing anthropogenic pressures on aquifer systems. This study presents the numerical modeling of groundwater flow in the Neogene–Quaternary aquifer system of the Middle Magdalena Valley (Colombia), focusing on the rural area of Puerto Wilches, which is characterized by strong surface–groundwater interactions, particularly with the Yarirí wetland and the Magdalena River. A three-dimensional model was implemented and calibrated in FEFLOW v.8.1 under steady-state and transient conditions, integrating both primary and secondary data. The dataset included piezometric levels measured with water level meters and automatic loggers, hydrometeorological records, 21 physicochemical and microbiological parameters analyzed in 45 samples collected during three field campaigns under contrasting hydrological conditions, 79 pumping tests, detailed lithological columns from drilled wells, and complementary geological and geophysical models. The results indicate a predominant east–west groundwater flow from the Eastern Cordillera toward the Magdalena River, with seasonal recharge and discharge patterns controlled by the bimodal rainfall regime. Microbiological contamination (total coliforms in 69% of groundwater samples) and nitrate concentrations above 10 mg/L in 21% of wells were detected, mainly due to agricultural fertilizers and domestic wastewater infiltration. Particle tracking revealed predominantly horizontal flow paths, with transit times of up to 800 years in intermediate units of the Real Group and around 60 years in shallow Quaternary deposits, highlighting the differential vulnerability of the system to contamination. These findings provide scientific foundations for strengthening integrated groundwater management in tropical regions under agroindustrial and hydrocarbon pressures and emphasize the need to consolidate monitoring networks, promote sustainable agricultural practices, and establish preventive measures to protect groundwater quality.

1. Introduction

Groundwater currently constitutes the main source of supply for human consumption and, in some regions, the only available source [1,2]. Excluding the water stored in glaciers and ice caps, groundwater accounts for nearly 96% of the freshwater available on the planet [3]. However, in recent decades its quality has been increasingly compromised by the intensification of agricultural, industrial, and domestic uses, which have amplified contamination processes [4,5]. In this context, it is essential to ensure the availability of groundwater through an integrated water resources management approach that explicitly incorporates anthropogenic contamination processes specific to each territory [6].

However, in many tropical developing countries, groundwater management is constrained by insufficient knowledge of the hydrogeological behavior of aquifer systems, a consequence of the scarcity of detailed information and the absence of systematic monitoring programs for groundwater quantity and quality [7,8,9,10]. This situation is further exacerbated by the weak articulation between management instruments and control mechanisms, as well as by the limited technical and institutional capacity of environmental authorities [11,12].

In this context, groundwater modeling emerges as a fundamental tool to understand the behavior of aquifer systems and to support decision-making in groundwater management [13,14,15]. Nevertheless, its implementation requires the development of an accurate conceptual hydrogeological model that integrates both field data and available secondary information, in order to graphically represent the aquifer system in terms of hydrogeological units, boundary conditions, flow conditions, hydraulic properties, and, when necessary, transport properties [16,17], and constitutes the foundation upon which the numerical model is built [17,18,19].

In addition to conventional field measurements, recent advances in satellite gravimetry offer an opportunity to complement groundwater assessments in data-scarce regions [20,21]. The GRACE and GRACE-FO missions provide regional terrestrial water-storage anomalies that reflect large-scale groundwater variations and seasonal hydrological dynamics [22,23]. In tropical developing countries, where groundwater monitoring networks are scarce, these satellite-derived signals represent an alternative for strengthening the validation of numerical models.

The implementation of numerical groundwater flow models makes it possible to analyze groundwater dynamics in greater detail and to evaluate the hydrodynamic behavior of aquifer systems, thereby reducing the uncertainty associated with understanding their functioning [24,25]. At the local scale, these models facilitate the integration of site-specific anthropogenic pressures into hydrogeological assessments, offering a more detailed understanding of their implications for groundwater flow and contamination [26,27].

In tropical developing countries, such as Colombia, traditional agricultural practices often involve the intensive use of fertilizers and pesticides, which increases the contaminant load in soils and enhances their leaching into water bodies, particularly during rainy periods [28,29,30,31]. This situation is compounded by the limited coverage of drinking water supply and sewerage systems in rural areas, characterized by scattered households where the population relies on individual solutions both for water supply and for the disposal of domestic wastewater, generally without adequate sanitary protection measures [30,32]. These conditions increase the vulnerability of aquifer systems to contamination, making the implementation of local-scale numerical models necessary to more accurately evaluate groundwater dynamics and the effects of these anthropogenic pressures on the system. Nevertheless, despite the growing interest in hydrogeological modeling in different regions of the world, studies applied to tropical aquifers under agroindustrial and hydrocarbon-related pressures remain scarce [25,32,33,34].

The water-quality analyses conducted in the study area reveal the presence of microbiological indicators and nutrients, such as coliforms and nitrates, which suggest local recharge processes and the infiltration of wastewater and agricultural activities [29]. These findings are associated with short groundwater travel times and indicate the vulnerability of the shallow aquifer units, factors considered in the construction of the conceptual model and that the numerical model seeks to represent through the simulation of flow patterns and recharge processes.

Therefore, this research addresses the hydrodynamic study of the Neogene–Quaternary aquifer system of the Middle Magdalena Valley (MMV), with a local-scale focus on the rural area of the municipality of Puerto Wilches, Colombia. This region is characterized by the coexistence of agroindustrial, livestock, and industrial activities, as well as by dispersed rural settlements and intermediate population centers [30,35,36]. In Puerto Wilches, in particular, the rural population relies mainly on shallow hand-dug wells without sanitary protection, while agroindustrial oil palm cultivation, hydrocarbon exploitation, and cattle ranching are also carried out in its territory [37,38]. In addition, the municipality borders the Magdalena River to the west and the Yarirí wetland to the northwest, which also gives it a fishing vocation [37]. These conditions make Puerto Wilches and its rural area a strategic location for the development of applied hydrogeological research aimed at generating inputs to strengthen integrated water resources management.

In this study, a numerical groundwater flow model, complemented with particle tracking techniques, is implemented to characterize surface–groundwater interactions, as well as local recharge patterns, seasonal discharge, and flow trajectories in the study area. Identifying these hydrodynamic processes is essential to understand the mechanisms of contaminant migration and dispersion in the subsurface, in a territory where agricultural, livestock, and industrial pressures converge. Therefore, the developed model enhancing the understanding of flow dynamics in a tropical aquifer system and provides technical inputs for the sustainable management of water resources. Beyond the local case, it also supports advances in groundwater flow modeling and in the evaluation of surface–groundwater interactions in contexts of high socio-environmental vulnerability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.1.1. Location

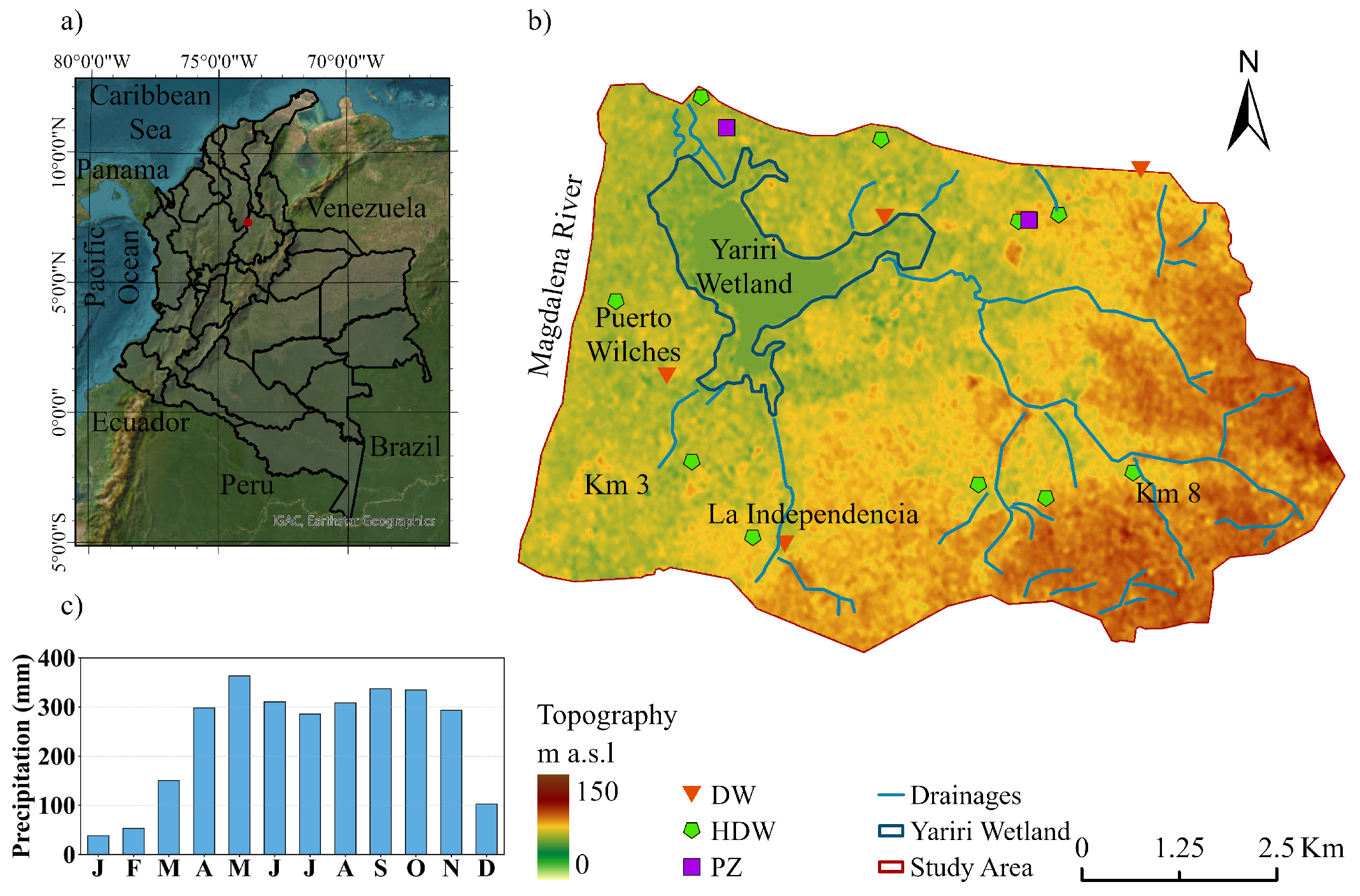

The study area (Figure 1) is located between latitudes 7° N and 7° N and longitudes 73°49′ W and 73°55′ W, within the municipality of Puerto Wilches, Santander Department, Colombia. It includes the urban core of Puerto Wilches while being predominantly rural in its overall extent. The study area covers approximately 53.38 km2 and lies in the central sector of the Middle Magdalena Valley (MMV). The terrain is predominantly flat, with elevations ranging from 55 to 105 m a.s.l., and exhibits a topographic gradient oriented east–west (Figure 1b). Land use is mainly characterized by agroindustrial activities associated with African oil palm monoculture, cattle and buffalo livestock farming, hydrocarbon extraction, fishing, and small-scale traditional agriculture [37,39].

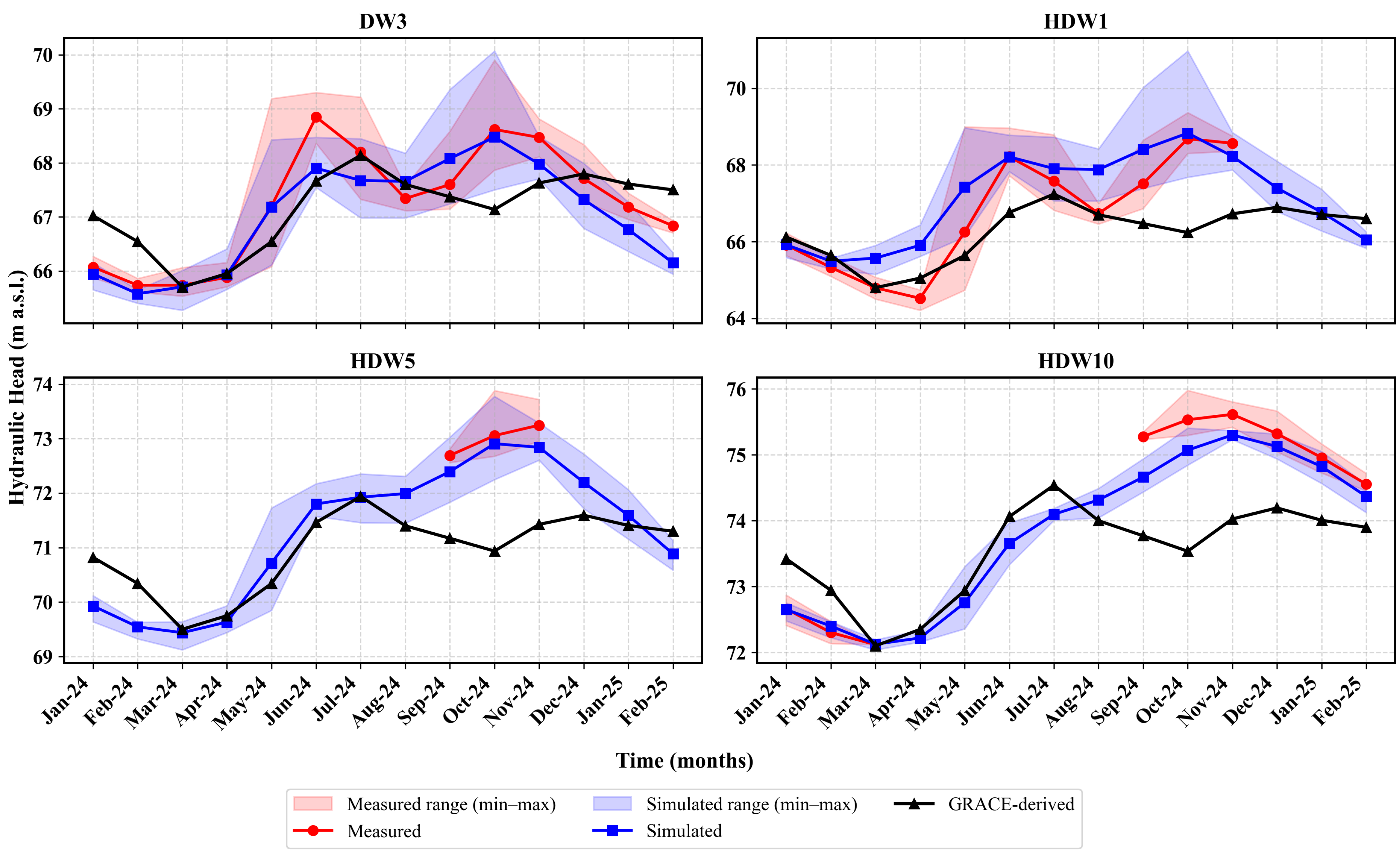

Figure 1.

Location and topographic setting of the study area in Puerto Wilches, Middle Magdalena Valley, Colombia. (a) Regional location of the study area within Colombia. (b) Detailed map of the study area showing topography (m a.s.l.), drainage network, Yarirí wetland, monitoring points (DW, HDW, and PZ), and the study area boundary. (c) Mean monthly precipitation regime representative of the study area. Sub-figures (a,b) were produced using ArcGIS Pro 3.5 based on the HydroSHEDS DEM (WWF, 2006–2013).

2.1.2. Geological and Geomorphological Setting

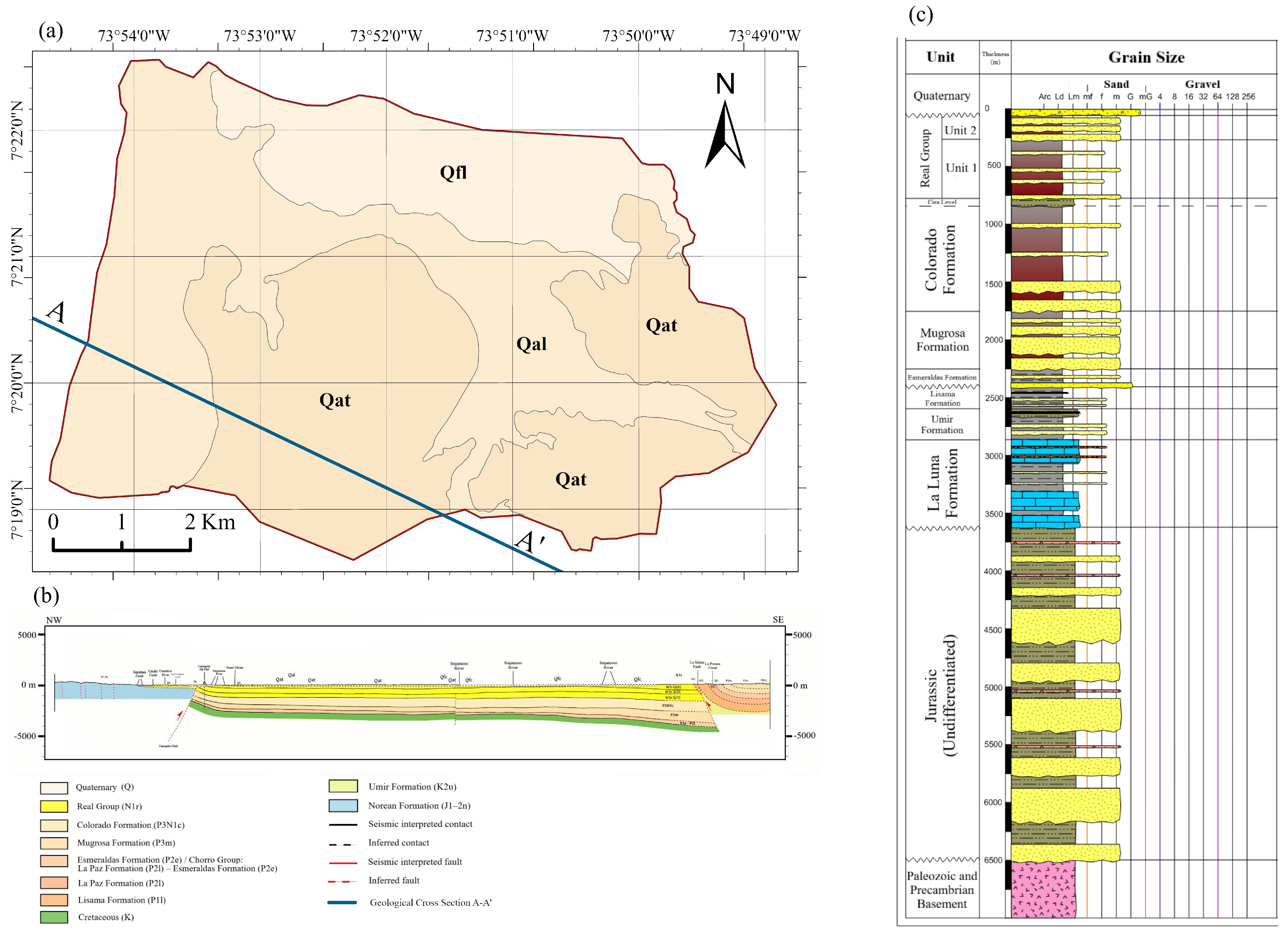

From a geological perspective, Quaternary deposits crop out in the study area and form three main landforms: fluvial, alluvial, and fluviolacustrine (Figure 2a). The fluvial deposits (QAl), associated with the Magdalena River and minor lotic systems, are composed of silts, medium- to fine-grained sands, and gravels with moderately sorted, rounded to subrounded clasts. The alluvial terraces (QAt), located in the southern sector, consist of pebbles and cobbles ranging from 5 to 25 cm in diameter, composed of igneous and sedimentary rocks with moderate sorting, embedded in a medium- to coarse-grained sandy matrix. Finally, the fluviolacustrine deposits (QFl), present in the northern sector around the Yarirí wetland, are composed mainly of gray clays, muds with high organic matter content, and fine sands [40,41].

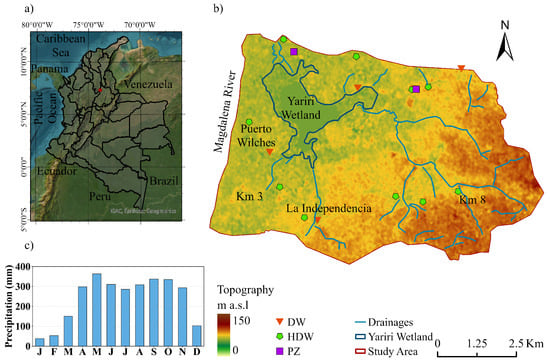

Figure 2.

Geological and geomorphological characterization of the study area showing (a) the map highlighting the outcropping Quaternary landforms in the Puerto Wilches area, (b) a simplified crosssection of the Middle Magdalena Valley illustrating the structural configuration and stratigraphic relationships between Neogene and Quaternary units, and (c) the representative lithological column derived from borehole and geophysical data.

Underlying the Quaternary deposits, the Real Group (Neogene) comprises four units (U4, U3, U2, and U1) (Figure 2b). The U4 unit, the most recent, consists of interbedded conglomeratic sandstones, conglomerates, and claystones, representing the most hydraulically conductive unit. The U3 and U2 units are dominated by fine- to medium-grained sandstones with intercalated claystones, while the U1 unit, the oldest, includes fine- to medium-grained sandstones interlayered with claystone and siltstone, and constitutes the least hydraulically conductive unit [36,42] (Figure 2c).

The Colorado Formation, a Paleogene unit underlying the Real Group, is composed of fine- to very fine-grained sandstones with abundant claystones and siltstones. It exhibits low hydrogeological potential and was considered the hydrogeological basement of the system in this study [36,40].

2.1.3. Rainfall and Surface Hydrology

The precipitation regime in the study area (Figure 1c), based on the records from the Puerto Wilches 23180020 station managed by the Institute of Hydrology, Meteorology and Environmental Studies of Colombia (IDEAM), exhibits a bimodal pattern associated with the seasonal displacement of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) [35,43]. The first rainfall maximum occurs between April and May, with a mean monthly precipitation of approximately 360 mm in May, while the second peak appears between September and October, with values close to 335 mm. The months of January and February correspond to the driest period, with averages below 60 mm, and an intermediate decrease is observed around July. Overall, the estimated mean annual precipitation reaches approximately 2970 mm/year.

The lotic water bodies identified in the study area display an intermittent behavior, primarily controlled by the seasonal variability of precipitation. In the northwestern sector, the Yarirí wetland, a lentic and permanent water body, acts as the main receptor of the intermittent drainage channels identified in the area, which converge toward it (Figure 1).

2.2. Materials

2.2.1. Groundwater Inventory

A groundwater inventory was conducted across the study area, encompassing deep wells, piezometers, and hand-dug wells. At each site, the depth to the water table and the elevation of the wellhead were measured, followed by a topographic leveling survey to accurately determine the piezometric head. A total of forty-five (45) groundwater points were identified, including twenty-seven (27) hand-dug wells, two (2) piezometers, and sixteen (16) deep wells. However, field access was granted for only seventeen (17) of these sites, consisting of five (5) deep wells, ten (10) hand-dug wells, and two (2) piezometers. Deep wells correspond to drilled and cased structures exceeding 15 m in depth, whereas hand-dug wells are shallow excavations less than 15 m deep and more than 10 inches in diameter. The descriptive information of the monitored sites is summarized in (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of monitored groundwater points and field measurements.

It is worth noting that piezometers PZ1 and PZ2 were constructed after the completion of the groundwater inventory as part of the monitoring nest designed for the study; nevertheless, they were included in Table 1 to provide a comprehensive summary of the monitored water points.

2.2.2. Water Sampling and Analytical Procedures

Three sampling campaigns for the physicochemical and microbiological characterization of groundwater were conducted within the study area. Additionally, one surface water point (Ciénaga Yarirí), located inside the study area and hydraulically connected to the aquifer system, was included due to its environmental and hydrogeological relevance. The sampling network was designed following the general groundwater flow direction, controlled by the topographic gradient from east to west, extending from the Eastern Cordillera toward the Magdalena River.

The first sampling campaign was conducted in February 2020, during the dry season, and included thirteen (13) samples collected from groundwater wells. The second campaign took place in November 2020, corresponding to the wet season of the hydrological year and influenced by the La Niña phenomenon, characterized by increased frequency and intensity of rainfall events [44], and comprised twenty-one (21) samples. The third campaign was carried out in March 2021, during the early transition to the wet season, with the collection of eleven (11) samples. Differences in the number of samples across campaigns were mainly related to variations in site accessibility and landowner authorization for field entry.

The selection of sampling sites was based on criteria of spatial representativeness, accessibility, safety, and available infrastructure. Priority was given to locations aligned with the groundwater flow direction, situated near the main road network to facilitate sample transport, and equipped with pumping systems that allowed proper well purging. Wells with known geometric design, total depth, and screened interval position were also preferred [30]. The inclusion of Ciénaga Yarirí aimed to provide complementary information on the interaction between groundwater and surface water within the local hydrogeological system. Table 2 summarizes the sampling points and the in situ parameters measured during the field campaigns. For sites sampled more than once, averaged values of the in situ measurements are reported to provide a representative and descriptive overview of field conditions.

Table 2.

Summary of monitored water points and field measurements.

Sampling procedures followed the protocols established in current Colombian technical standards [45,46]. Each well was purged until stabilization of the in situ measured parameters using a previously calibrated YSI ProQuatro multiparameter probe. Samples were collected in 2 L plastic bottles for physicochemical analyses, 1 L amber glass bottles for microbiological analyses, and 0.5 L clear glass bottles for fats and oils analyses. Samples were preserved with nitric acid or thiosulfate, as appropriate for each analysis, and kept at 4 °C in insulated containers with ice and cooling gels until laboratory processing. Laboratory analyses were conducted at the Chemical and Environmental Engineering Laboratory of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia, following the Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater [47].

2.2.3. Design of Monitoring Nests

Based on the information obtained from the inventory of groundwater points, the results of the physicochemical sampling, and the secondary geological data derived from the lithological column of the Middle Magdalena Valley (MMV) in the Puerto Wilches area, together with the lithological description of the Neogene–Quaternary units under study and the hydrogeological profiles of the basin estimated from regional-scale seismic interpretation, the need to construct a monitoring nest within the study area was identified.

The monitoring nest consists of two research piezometers: the first one (PZ1) with a total depth of 324 m, and the second one (PZ2) with a depth of 277 m. Both wells were cased down to 269.5 m and equipped with 36 m of screens distributed over five intervals, located in the zones with higher hydraulic conductivity. In each borehole, geophysical well logs (gamma ray, resistivity, and sonic) were recorded, and drill cuttings were recovered. These data were used to construct detailed lithological columns for each drilled well.

In addition, a compact meteorological station (Atmos 41) was installed to improve the accuracy of local climate monitoring, particularly precipitation, and to assess its relationship with infiltration and recharge processes within the study area.

Furthermore, four dataloggers were installed in existing wells within the study area where installation permits were obtained: HDW1, HDW5, HDW10, and DW3. However, due to logistical and financial constraints, continuous measurements could only be maintained in well DW3, where the piezometric evolution was recorded throughout the entire monitoring period.

2.3. Conceptual Model

Groundwater modeling is commonly based on the development of a single conceptual model [48,49,50]. In this study, a conceptual model was constructed from secondary information, including geological, lithological, hydrogeological, and geoelectrical analyses, and subsequently refined using primary data obtained from physicochemical, piezometric, and hydraulic measurements, as well as lithological analyses from boreholes drilled within the study area. This integration aimed to reduce parametric uncertainty and enhance the understanding of the geological structure and hydrodynamic behavior of the analyzed Neogene–Quaternary aquifer system.

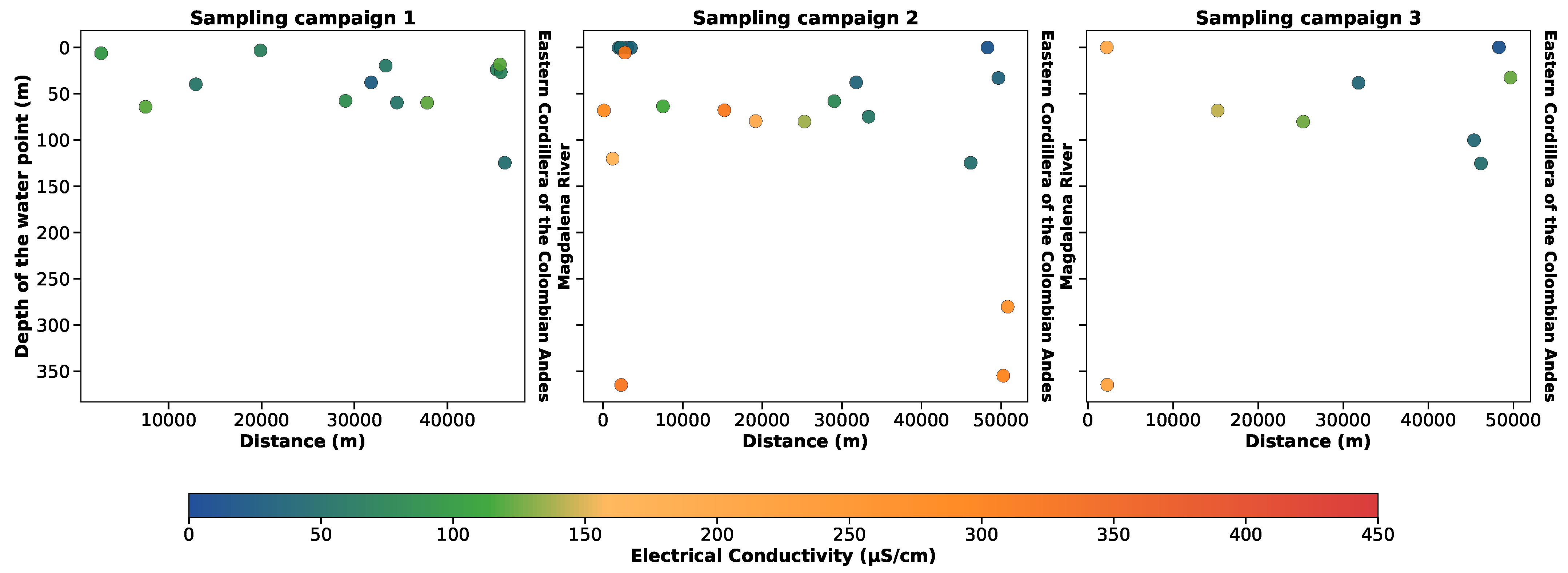

2.3.1. Physicochemical Analysis

The electrical conductivity (EC) behavior was analyzed across the three sampling campaigns to identify potential patterns associated with the hydrogeodynamic behavior of groundwater flow [51]. An increasing trend in EC was observed along the east–west direction, from the Eastern Andes Cordillera toward the Magdalena River (Figure 3), consistent with the regional topographic gradient and validating the main groundwater flow direction. This spatial pattern supports the hypothesis of a predominantly regional flow system oriented from east to west, a hypothesis that is further examined through the implementation of the numerical model.

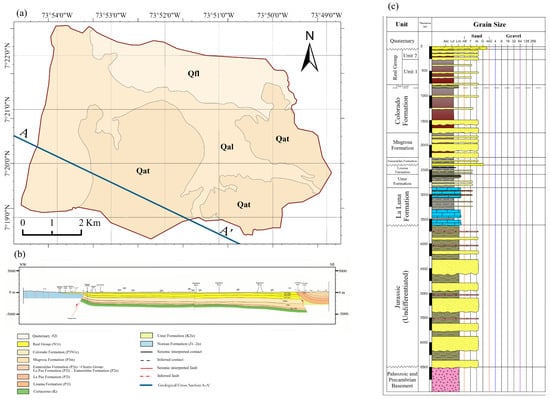

Figure 3.

Spatial variation of groundwater electrical conductivity (EC) during the three sampling campaigns along the main east–west flow path from the Eastern Andes Cordillera toward the Magdalena River.

This trend was particularly evident during the second sampling campaign, conducted in the wet season of 2020, when shallow wells (depths < 15 m) exhibited EC values below 50 µS/cm, suggesting local recharge processes associated with rainfall infiltration. In contrast, wells deeper than 150 m recorded EC values above 350 µS/cm, even in areas near the Eastern Andes. The increase in conductivity, and consequently in the degree of mineralization with depth, is attributed to longer groundwater residence times and enhanced water–rock interactions and mineral dissolution processes, reflecting the hydrogeochemical evolution of the aquifer system.

Additionally, twenty-one water quality parameters were analyzed in the laboratory (Table 3), including in situ pH measurements. The results for each sample and parameter were compared against the maximum permissible limits established by Colombian drinking water quality standards [52,53].

Table 3.

Summary of compliance of physicochemical and microbiological parameters with Colombian water quality standards.

Results showed that 69% of the samples did not comply with total coliform standards, indicating microbiological contamination. This outcome was expected, as the field inventory revealed that many wells and hand-dug wells are located near handmade pit latrines lacking adequate sanitary protection. Backyard livestock activities were also observed near several sampling sites. Hence, the presence of total coliforms serves as an indicator of local recharge processes influenced by surface anthropogenic sources.

Nitrate concentrations exceeded the maximum permissible limit of 10 mg/L in 21% of the samples. This finding is consistent with the presence of extensive African oil palm plantations in the study area, where the intensive use of nitrogen-based fertilizers promotes nitrate leaching into shallow aquifers [54,55].

Furthermore, 33% of the samples exceeded the permissible limits for iron in drinking water, likely due to the presence of iron oxide-rich soils in the region [30]. Similarly, 60% of the samples showed pH values outside the acceptable range, and 10% exhibited aluminum concentrations above the maximum permissible limit.

The water-quality results obtained in the study area, particularly the detection of coliforms and nitrates, indicate the direct influence of surface sources and agricultural practices on recharge processes. These parameters reveal the infiltration of wastewater and fertilizers, as well as short groundwater travel times within the shallow units, which corroborates the hypothesis of local recharge processes in the study area.

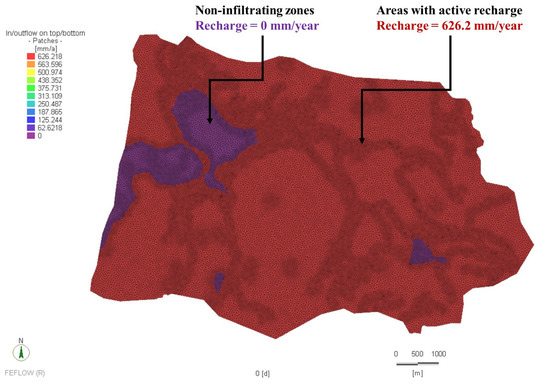

Based on this hydrochemical evidence, the conceptual model assumed a recharge surface covering the entire study area, except for permanent water bodies, both lentic and lotic. In the specific case of the Yarirí wetland, a historical analysis of satellite imagery from 1970 onward was conducted to delineate the area persistently covered by surface water. Within this zone, as well as in permanent lotic bodies, recharge was restricted and a seepage boundary condition was assigned, allowing only the discharge of baseflow from the aquifer to the surface–water system.

2.3.2. Hydraulic Head and Flow Direction

Based on the groundwater inventory, in which water table depths were measured and topographic leveling was performed to accurately determine piezometric heads, it was confirmed that the hydraulic gradient follows a general east–west direction, consistent with the topographic gradient. This finding supports the hypothesis that the main groundwater flow occurs along this orientation.

2.3.3. Groundwater Recharge

In the construction of the hydrogeological model, the existence of local recharge processes was assumed. The coexistence of agricultural activities, dispersed rural settlements, and point sources of surface contamination implies that recharge may transport contaminants toward the shallow aquifer units, increasing their vulnerability [56,57]. Since the probability of contaminant transfer to the aquifer tends to increase in areas with higher recharge rates, this parameter constitutes a critical element in the representation of the system [58]. Consequently, the estimation of recharge plays a central role in the construction of the groundwater flow model under anthropogenic pressure conditions in the Middle Magdalena Valley.

However, although recharge is one of the most relevant components in hydrogeological studies, it is also one of the least understood [57,59]. Currently, its precise estimation represents one of the major challenges in hydrogeological modeling, to the extent that no standards exist to reliably evaluate the accuracy of available estimates [58].

There are several methods available for estimating groundwater recharge, including water budget approaches, numerical modeling techniques, methods based on surface water and groundwater interactions, approaches that analyze processes within the unsaturated and saturated zones, and techniques that rely on natural or applied tracers [58,60,61]. Water budget methods provide preliminary estimates derived from precipitation, evapotranspiration, and changes in storage at the basin scale. Numerical modeling, through calibration and inverse modeling, refines these estimates using physically based simulations. Other approaches quantify recharge by examining exchanges between streams and aquifers through budget analyses, seepage measurements, or hydrograph interpretation. In the subsurface, recharge can be inferred from hydraulic responses and time series analyses within the unsaturated or saturated zones [62]. Tracer-based methods, including thermal, chemical, and isotopic indicators, offer independent evidence to quantify recharge by interpreting natural environmental signatures [63,64,65].

In this study, groundwater recharge was estimated through the calibration and inverse modeling processes of the numerical model. However, to initiate this procedure, a preliminary value was adopted based on the application of the empirical methods of Chaturvedi, Amritsar, and Krishna Rao [66], which yielded recharge percentages equivalent to 17.5%, 21.8%, and 27.7% of the annual precipitation, respectively.

Based on these results, an initial value corresponding to 21.8% of the annual precipitation was assumed for the steady-state simulation. This percentage, which matches the median of the empirical estimates, represents a recharge of 626.25 mm/year for the study area. This preliminary value served as the initial condition for the model and was subsequently refined through the calibration and inverse modeling procedures in order to obtain an estimate that more accurately reflects the local hydrogeological conditions.

2.3.4. Estimation of Hydraulic Parameters

To estimate the hydraulic parameters, 48-h pumping tests were conducted in the research piezometers installed as part of this study, using one well as the pumping well and the other as the observation well. The interpretation of the tests followed the methodology proposed by [67], which includes a data preprocessing stage aimed at removing outliers and noise through the application of a Butterworth digital filter implemented in the Hytool package V2.0.5) [68]. Subsequently, the most suitable flow model was selected based on the analysis of diagnostic plots proposed by [69], represented in logarithmic and semi-logarithmic scales. Finally, the quantitative interpretation of the pumping tests was performed using AQTESOLV Professional, version 4.5.

However, because the geometric design of the drilled wells included multiple screened intervals located in zones of higher hydraulic conductivity, the estimation of hydraulic parameters differentiated by hydrogeological unit was not feasible from these tests. To achieve such resolution, it would have been necessary to perform packer tests, which enable hydraulic isolation of specific stratigraphic intervals during testing [67]. Nevertheless, this approach could not be implemented due to logistical constraints and the limited availability of this technology in Colombia for telescopic well designs such as those used in this study.

Consequently, a set of 79 pumping tests conducted in different sectors of the Middle Magdalena Valley (MMV), outside the immediate study area but intersecting the various units of the Real Group and the Quaternary landforms (QAl, QAt, and QFl), was compiled to complement the analysis and improve the hydraulic characterization of the Neogene–Quaternary aquifer system.

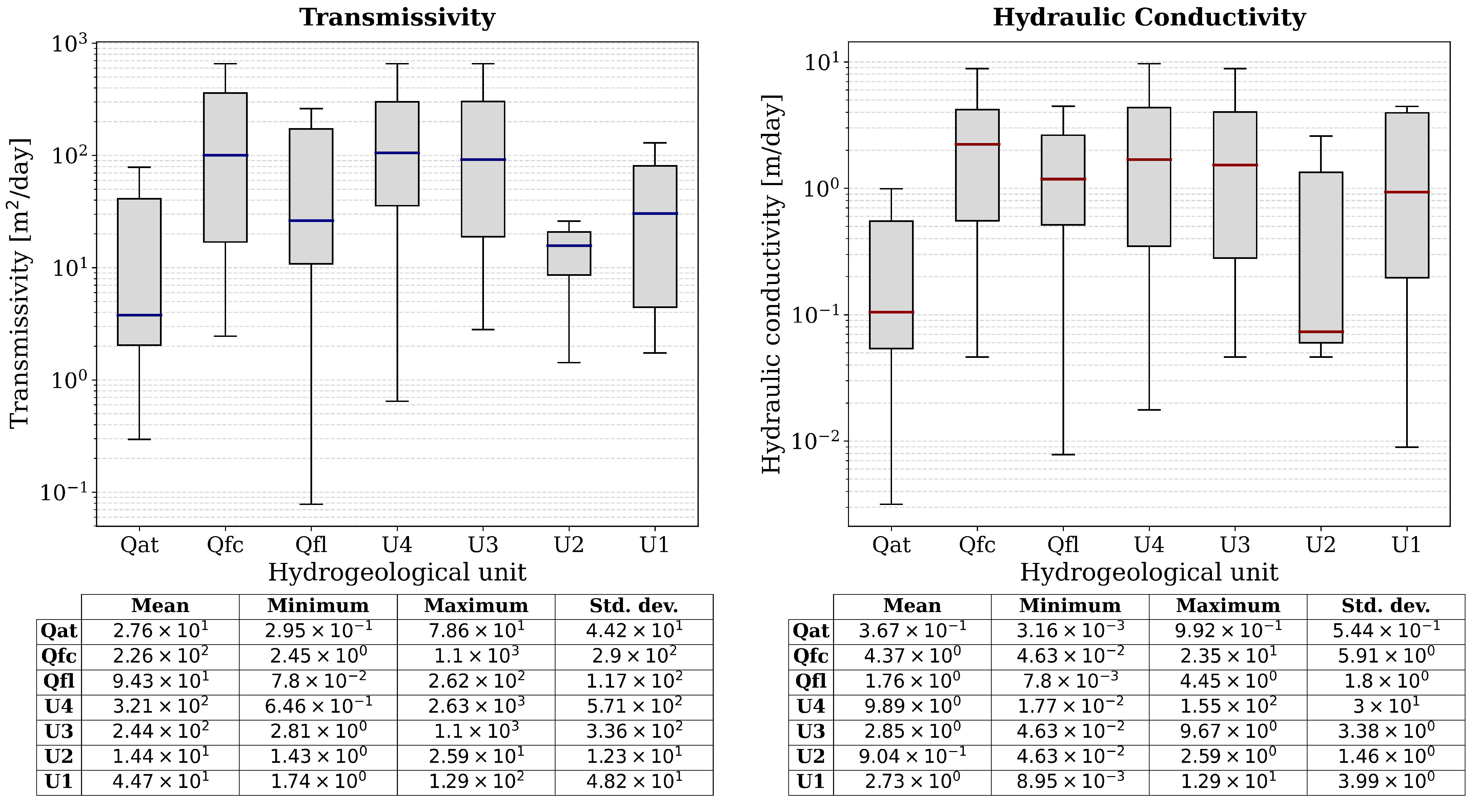

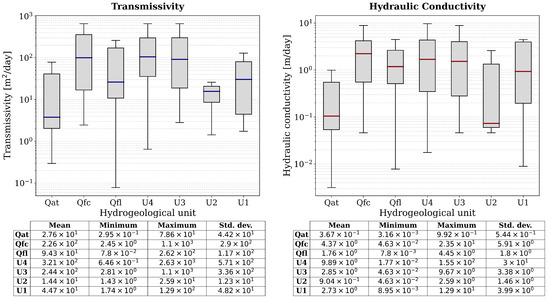

The analysis of these pumping tests revealed that hydraulic conductivity (K) varies by up to three orders of magnitude within the same hydrogeological unit, reflecting pronounced local-scale heterogeneity. This variability is consistent with the lithological descriptions from the boreholes, where interbedded fine- to coarse-grained sands and gravel layers with intercalated clays and silts were identified, particularly in the upper units of the Real Group and the Quaternary deposits. Nevertheless, the mean values of hydraulic conductivity and transmissivity remain within the same order of magnitude (Figure 4), indicating a relatively homogeneous hydraulic behavior among the Neogene–Quaternary hydrogeological units at the regional scale in the Middle Magdalena Valley.

Figure 4.

Boxplot of Hydraulic Conductivity (K) and Transmissivity (T) for the Quaternary and Neogene Hydrogeological Units in the Middle Magdalena Valley (MMV).

Among the Quaternary landforms, the QFc unit exhibits the highest hydraulic conductivity, while QAt presents the lowest values. Within the Real Group, units U4 and U3 display the highest conductivities and transmissivities, whereas U2 and U1 show the lowest, reflecting the transition toward finer-grained and less permeable facies.

2.3.5. Conceptual Model Formulation

The modeling domain considered in this study corresponds to the study area described in Section 2.1. Based on piezometric and hydrochemical information, a regional groundwater flow was defined in an east–west direction, from the Eastern Andes Cordillera toward the Magdalena River, with local discharges occurring in the Yarirí wetland and other surface water bodies. This flow pattern indicates an interaction between surface water and groundwater, which is controlled by the seasonal behavior of the system, characterized by drawdown during the dry period and recovery during the wet season. Additionally, local recharge processes associated with direct rainfall infiltration and contributions from fluvial systems were identified.

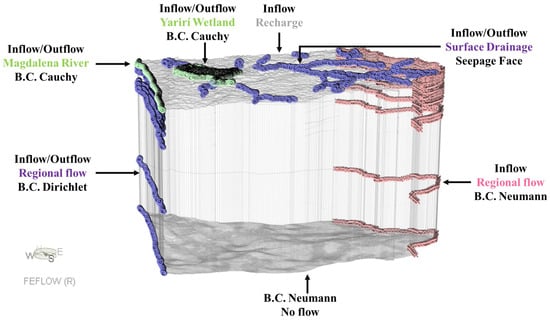

The conceptual model (Figure 5) focused on representing the Neogene–Quaternary deposits, considering the Colorado Formation, located beneath the U1 unit of the Real Group and predominantly composed of claystones and siltstones, as the hydrogeological basement of the system [70,71]. A no-flow (Neumann) boundary condition was assigned to this surface, defining the lower limit of the model domain. The western limit of the domain, corresponding to the Magdalena River, was represented by a Cauchy-type (general head) boundary condition; however, at depth and below the main riverbed, a Dirichlet-type (specified head) condition was defined to simulate the regional hydraulic connection. The eastern boundary was represented by a Neumann-type condition to reproduce the regional inflow from the Eastern Cordillera.

Figure 5.

Conceptual model of the Neogene–Quaternary aquifer system illustrating boundary conditions and surface–groundwater interactions. The model visualization was generated using FEFLOW V 8.1 (update 3).

At the top of the model, recharge was defined as the main input to the system, with an initial value equivalent to 21.8% of the mean annual precipitation across the entire domain, except over the settlements, the Yarirí wetland, and other surface water bodies during the wet season, where recharge was neglected. This parameter will be adjusted during model calibration. The Yarirí wetland was represented by a Cauchy-type boundary condition, whereas intermittent surface drainage features were simulated using a seepage face boundary condition, which allows aquifer discharge when the water table rises above the streambed elevation, ensuring a more realistic representation of intermittent and localized flow processes [72,73].

2.4. Numerical Groundwater Flow Model (NGFM)

To analyze the dynamics of groundwater flow and surface–groundwater interactions in a tropical aquifer subjected to multiple anthropogenic pressures, a local-scale numerical flow model was developed for the municipality of Puerto Wilches, based on the previously described conceptual model. This municipality, with a population of more than 30,000 inhabitants, relies heavily on groundwater resources, particularly in rural areas where shallow wells constitute the main source of domestic water supply. The model was implemented to represent the hydrodynamic behavior of the Neogene–Quaternary aquifer system and to improve the understanding of the flow mechanisms that control groundwater availability and vulnerability.

The numerical modeling was carried out using the FEFLOW v.8.1 software, developed by the DHI WASY Institute, which is based on the finite element method and allows the simulation of groundwater flow under saturated and unsaturated conditions, as well as solute transport and particle tracking in three-dimensional porous media [74]. The model was implemented and calibrated under both steady-state and transient conditions to reproduce the spatial and temporal dynamics of the groundwater system.

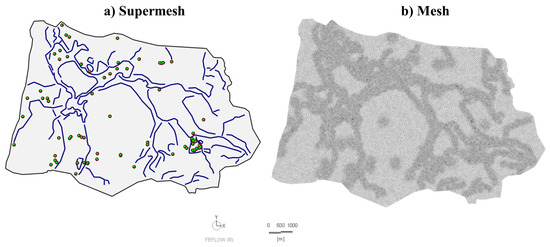

2.4.1. Meshing

A two-dimensional (2D) mesh was constructed explicitly incorporating the contours of the Yarirí wetland, the locations of inventoried groundwater points, the identified surface drainage, the outcrops of the Quaternary landforms, and populated centers (Figure 6a). The surface mesh was generated using the Triangle algorithm integrated into FEFLOW V.8.1 (update 3), which allows the creation of unstructured triangular-element meshes adaptable to complex geometries and capable of localized refinement according to the spatial distribution of geological and hydraulic data [75].

Figure 6.

Process of mesh generation: (a) supermesh definition explicitly incorporating the contours of the Yarirí wetland, the surface drainage network, the locations of inventoried water points (green dots), and the main Quaternary landforms and settlements; and (b) resulting triangular finite-element mesh generated in FEFLOW V 8.1 (update 3).

The final 2D mesh (Figure 6b) consisted of 73,882 elements and 37,271 nodes, with an average edge length of 45.65 m and a standard deviation of 11.82 m. In areas with higher hydrogeological data density, an adaptive refinement was applied, achieving an average edge length of approximately 16.49 m. This approach optimized the balance between spatial resolution and computational efficiency [17]. The geometric quality of the mesh was verified according to Delaunay and maximum internal angle criteria, ensuring numerical stability throughout the model domain [76].

Based on this surface discretization, a three-dimensional (3D) mesh was developed to represent the hydrogeological contacts between the units of the Real Group and the Quaternary deposits. The upper boundary of the 3D mesh corresponded to the topographic surface derived from NASA’s Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) digital elevation model, while the lower boundary was defined at the base of the Real Group. To represent surface–groundwater interactions, unsaturated and intermediate layers were incorporated, coinciding with the screened intervals of the drilled piezometers where lithological uncertainty was lowest. The final 3D mesh comprised 1,403,758 elements and 745,420 nodes distributed across 20 horizontal layers, providing an adequate spatial discretization for both steady-state and transient groundwater flow simulations.

2.4.2. Boundary Conditions

Figure 5 schematically illustrates the boundary conditions implemented in the NGFM. The western boundary of the model was defined based on the conceptual hydrogeological model, assuming that the Magdalena River acts as a local discharge zone of the groundwater system. A Dirichlet boundary condition (Hydraulic Head BC) was assigned along this boundary, with a constant hydraulic head equal to the river water level. At the eastern boundary, a Neumann boundary condition (Fluid-Flux BC) was imposed to represent the regional inflow [77,78], with flux values ranging between 0.0002 m/d and 0.0059 m/d, which were adjusted during model calibration. The northern and southern boundaries were defined as no-flow Neumann conditions, assuming that the regional groundwater flow direction is approximately east–west and parallel to these limits.

The top boundary was represented by an “in-/outflow on top/bottom” condition associated with recharge from infiltration, initially estimated as 21.8% of the mean annual precipitation and subsequently calibrated. Urban and settlement areas were treated as impermeable no-flow zones.

For the implementation of the hydrogeological model, recharge was treated as a second-type (Neumann) upper boundary condition, represented numerically as an “in-/outflow on top/bottom” condition, applied exclusively to those elements in the mesh that allow infiltration. Urban and settlement areas, as well as the permanently inundated zone of the Yarirí wetland, were defined as impermeable no-flow zones, and therefore excluded from the recharge domain. Given that the model was developed at a local scale and Quaternary deposits outcrop throughout the entire domain, recharge was assumed to be spatially uniform across the study area (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Spatial distribution of the upper recharge boundary condition defined in the hydrogeological model.The figure was generated in FEFLOW v8.1 (update 3).

As described in the conceptual model, the study area exhibits active surface–groundwater interactions among the Yarirí wetland, the Magdalena River, and minor drainage channels. These interactions vary seasonally in response to rainfall and regional groundwater dynamics, producing alternating gaining and losing conditions in surface water bodies. To represent these processes, a Cauchy-type boundary condition was implemented along the Yarirí wetland and the Magdalena River using the Fluid-Transfer BC option in FEFLOW [74]. This condition simulates a flux proportional to the hydraulic head difference between the surface water () and the aquifer (), multiplied by a transfer coefficient () that represents the hydraulic conductance of the riverbed, as shown in Equation (1):

A transfer coefficient of was adopted, consistent with values reported for tropical alluvial aquifer systems [79].

2.4.3. Hydraulic Parameterization

The parameterization of the numerical groundwater flow model (NGFM) consisted of assigning hydraulic properties to different zones of the domain according to the distribution and characteristics of the geological units and structures defined in the conceptual model [17,80,81].

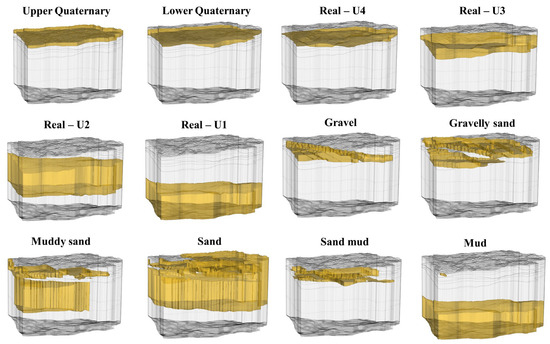

For the zonation, six main hydrogeological units were defined: the four units of the Real Group and the Quaternary deposits (Figure 8), the latter subdivided into Upper Quaternary and Lower Quaternary. The Upper Quaternary extends from the surface to approximately 75 m depth, coinciding with the base of the piezometer screens installed during this investigation and representing the most conductive portion of the hydrosystem. The Lower Quaternary extends from this depth to the top of the Real Group.

Figure 8.

Hydrogeological and lithologic zonation used for the parameterization of the numerical groundwater flow model (NGFM), generated using FEFLOW v.8.1 (update 3).

In addition, a regional lithological model of the Middle Magdalena Valley was employed, identifying six lithologic units within the study area: gravel, gravelly sand, muddy sand, sand, sandy mud, and mud (Figure 8). The intersection between the six hydrogeological zones and the six lithologic units resulted in 17 parameterization zones, defined as follows: Upper Q–Gravel, Upper Q–Gravelly sand, Upper Q–Sand, Lower Q–Gravel, Lower Q–Gravelly sand, Lower Q–Sand, Real U4–Gravel, Real U4–Gravelly sand, Real U4–Sand, Real U3–Gravel, Real U3–Gravelly sand, Real U3–Muddy sand, Real U3–Sand, Real U3–Sandy mud, Real U2–Muddy sand, Real U2–Sand, and Real U1–Mud.

The hydraulic conductivity values assigned to the 17 zones were based on average values derived from pumping test data (Figure 4). For the four units of the Real Group, mean horizontal hydraulic conductivity values from these tests were applied, without differentiating internal lithological variations. Similarly, all Quaternary deposits were assigned a uniform horizontal hydraulic conductivity of 3.4 m/d, corresponding to the mean value obtained from tests conducted in Quaternary materials, regardless of local geomorphological differences.

This assignment represents an initial step prior to model calibration, during which hydraulic parameters are individually adjusted for each of the 17 defined zones.

It is worth noting that hydraulic conductivity tends to increase with the scale of analysis; therefore, the values calibrated in the local-scale numerical model are expected to be slightly higher than those estimated at the well scale [82,83].

Finally, an anisotropy ratio of 10:1 between horizontal and vertical hydraulic conductivity was adopted, a common practice in the numerical modeling of alluvial aquifer systems when detailed anisotropy data are not available [84,85].

2.4.4. Sensitivity Analysis of Hydraulic Parameters

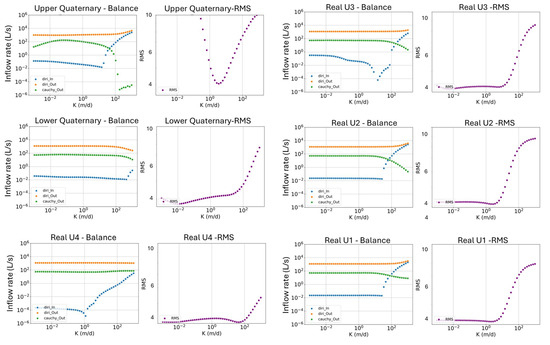

A sensitivity analysis was conducted to evaluate the effect of variations in specific hydraulic parameters on model performance and associated statistical metrics under both steady-state and transient conditions. The analysis focused on the six main hydrogeological units. The methodology consisted of varying the horizontal hydraulic conductivity (K) individually within each zone while keeping all other parameters constant across the model domain [86].

A total of 30 steady state simulations were performed for each hydrogeological unit, varying (K) over a range from 0.001 to 1000 m/d. The results (Figure 9) show the relationship between hydraulic conductivity, flow balance at the model boundaries, and variations in the root mean square error (RMS), which remained below 10 in all simulations, an acceptable threshold for model calibration. The Upper Quaternary and U4 units exhibit RMS curves with a characteristic “U” shape, indicating an optimal range of (K) that provides the best fit between simulated and observed heads. In contrast, the deeper units (U3, U2, and U1) show more pronounced nonlinear responses, reflecting the heterogeneity of the medium and the combined influence of local and regional flow components that characterize the modeled hydrogeological system [87,88].

Figure 9.

Results of the sensitivity analysis of the NGFM, showing the variation of the boundary flow balance and root mean square error (RMS) as a function of hydraulic conductivity for each hydrogeological unit. Figures were generated using Python 3.13.5.

2.4.5. Observation Points Used in Model Calibration

The observation points used for the calibration of the steady-state model correspond to the groundwater monitoring points inventoried within the study area (Table 1 and Figure 1b). In addition, the screened intervals of the research piezometers drilled as part of this study were included as control points. Although these intervals were represented in the model as a single observation point in plan view, that point integrates the hydraulic response associated with all screened intervals, reflecting the composite vertical behavior of the aquifer system at each site.

For the calibration of the transient-state model, the solution obtained in the steady-state model served as the starting point. However, the availability of information in the study area is limited, as only four wells are instrumented with automatic level sensors. Consequently, only these four control points could be used in the transient calibration, which reduces the ability to represent the spatial variability of the system. Moreover, the scarcity of instrumented points limits the possibility of evaluating the simulated flow fields through direct comparisons with measured water levels. Therefore, it becomes necessary to complement the modeling with validations using independent information sources.

In this regard, a complementary analysis was incorporated based on monthly groundwater-level variations derived from GRACE and GRACE-FO, which provide a regional hydrological signal and allow assessment of the temporal coherence of the simulated behavior beyond the local monitoring network.

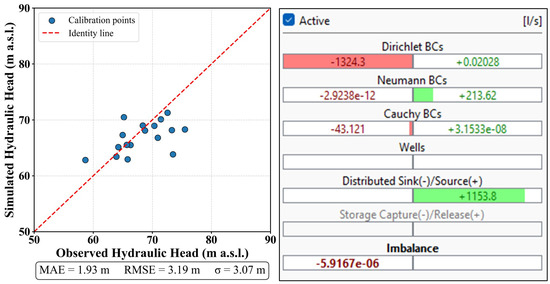

2.4.6. Steady-State Model Calibration

The steady-state calibration (Figure 10) was performed through an iterative process of successive adjustments combined with sensitivity analysis. To ensure consistency with the steady-state assumption, the calibration used hydraulic head measurements collected during the January 2023 groundwater-level inventory, a period corresponding to the dry season. Under these low-precipitation conditions, groundwater levels exhibit minimal short-term fluctuations associated with local recharge events, allowing the system to approximate quasi-equilibrium conditions. This approach follows methodological recommendations indicating that steady-state calibration should rely on observations representative of stable hydrodynamic conditions, avoiding measurements influenced by transient recharge processes [89,90]. The final calibration achieved an RMSE of 3.19 m and an MAE of 1.93 m, indicating a statistically acceptable level of agreement between simulated and observed hydraulic heads [91]. However, some uncertainty remains, associated with field measurement errors, the accuracy of the digital elevation model (DEM), the characterization of subsurface hydraulic properties, and the simplifying assumptions adopted in the conceptual model.

Figure 10.

Steady-state model calibration showing the comparison between observed and simulated hydraulic heads and the corresponding water-balance components. Figures were generated using Python 3.13.5.

2.4.7. Transient-State Model Calibration

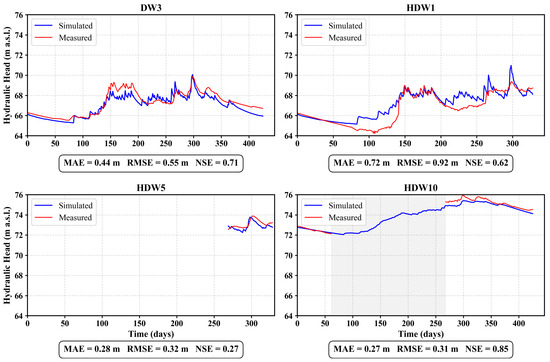

The transient state calibration was carried out using groundwater level records obtained from four observation wells (DW3, HDW1, HDW5, and HDW10) equipped with automatic water level loggers. The measured hydraulic heads were compared with those simulated by the numerical model, considering a modeling period extending from January 2024 to March 2025.

However, due to logistical constraints, continuous data acquisition could not be maintained throughout the entire monitoring period. Consequently, the available time series correspond to specific intervals within the simulation period, which were used for transient calibration. Only well DW3, the deepest of the instrumented wells, provided continuous records throughout the entire modeled period.

3. Results and Discusion

The numerical groundwater flow modeling provided a detailed characterization of the hydrodynamic behavior of the Neogene–Quaternary aquifer system in the Middle Magdalena Valley, with a local emphasis on the Puerto Wilches area. The simulations enabled the identification of dominant groundwater flow patterns, recharge and discharge processes, and groundwater–surface water interactions. These results were further supported by particle-tracking analyses, which revealed preferential subsurface flow paths and representative groundwater transit times.

Model results confirm the predominance of an east–west groundwater flow direction, with discharge toward the Magdalena River and the Yarirí wetland, consistent with the conceptual model. The steady-state water balance indicates that rainfall infiltration constitutes the main recharge mechanism, whereas discharge discharge occurs primarily into surface water bodies and through river-aquifer exchanges.

In the steady-state numerical model, the mass balance exhibited an imbalance of L/s, which is numerically negligible. This result confirms appropriate water mass conservation and demonstrates the internal consistency between the conceptual and numerical boundary conditions.

Groundwater inflows are mainly controlled by lateral regional flow (+213.62 L/s) and spatially distributed recharge from precipitation (+1153.8 L/s), whereas outflows occur through the Dirichlet boundary representing the Magdalena River (−1324.3 L/s) and through Cauchy-type boundaries that simulate exchange with surface water bodies such as the Yarirí wetland (−43.12 L/s). These fluxes indicate that the aquifer behaves predominantly as a discharge system toward adjacent hydrological features.

Additionally, the steady-state calibration yielded a recharge rate of 740 mm/year, equivalent to 25.7% of the mean annual precipitation. This estimate is practically consistent with the empirical value derived from the Krishna Rao method, which is based on the assumption of an unconfined aquifer that exhibits a rapid and direct response to precipitation inputs [92]. These assumptions align with the hydrostratigraphic and hydrodynamic characteristics of the study area, where the outcropping units are dominated by highly permeable Quaternary deposits that promote vertical infiltration.

Recharge processes are particularly relevant in this rural region, where limited water supply and sanitation infrastructure increase the vulnerability of the shallow aquifer to contamination. Physicochemical and microbiological analyses revealed total coliforms in 69% of samples and nitrate concentrations above 10 mg/L in 21%, suggesting contamination linked to domestic effluents and the use of nitrogen-based fertilizers.

Understanding the magnitude and spatial distribution of rainfall-driven recharge, and in general the vertical flow behavior of the shallow hydrosystem, is therefore essential for interpreting contaminant pathways and assessing the hydrodynamic response of tropical aquifers subject to anthropogenic pressures, a common situation in rural environments of developing countries such as Colombia.

The calibrated hydraulic parameters are summarized in Table 4. Vertical hydraulic conductivity () was assigned as one-tenth of the horizontal hydraulic conductivity (), following an anisotropy ratio widely used for alluvial aquifers [84,85].

Table 4.

Calibrated hydraulic parameters for the steady-state and transient numerical groundwater flow models.

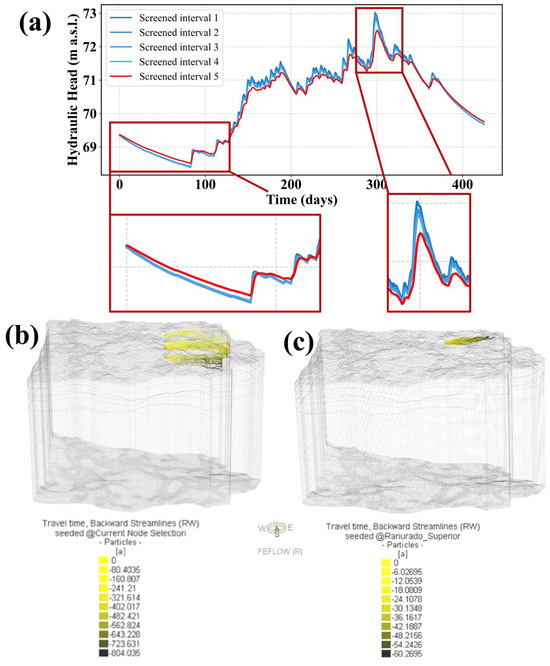

The transient-state calibration (Figure 11) confirmed that the numerical model is able to reproduce the dynamic response of the aquifer system to seasonal hydrological forcing. Simulated groundwater levels show good agreement with observations across the monitoring network, capturing both short-term fluctuations and long-term seasonal trends. Model performance ranges from acceptable to excellent, with NSE values between 0.27 and 0.85 and RMSE values between 0.31 and 0.92 m. Wells DW3 and HDW10 exhibit the highest overall agreement, reflecting the capacity of the model to replicate recharge-driven rises and subsequent recession periods. Although the monitoring record for HDW5 is limited, low MAE and RMSE values indicate that absolute differences between simulated and measured heads remain small.

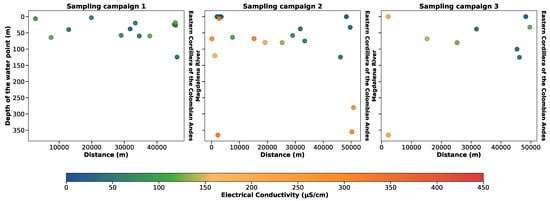

Figure 11.

Transient-state model calibration results showing the agreement between measured and simulated hydraulic heads at the monitoring wells. Figures were generated using Python 3.13.5.

Simulated hydraulic heads under transient conditions were analyzed for the five screened intervals of one of the research piezometers (Pz-1) (Figure 12a). During the first three months of simulation (January to March 2024) and again toward the end of the simulation period in early 2025, both characterized by dry climatic conditions and limited precipitation, the deepest screened interval (red line) maintained higher hydraulic heads than the shallow intervals (blue lines). This behavior indicates the presence of upward vertical flow from deeper units toward near-surface zones, suggesting that the groundwater system acts as a discharge source to surface water bodies. Consequently, the study area behaves as a regional discharge zone during the dry periods of the hydrological year, transferring groundwater toward the Yarirí wetland and the Magdalena River.

Figure 12.

Simulated hydraulic head and particle-tracking analysis results. (a) Temporal variation of simulated hydraulic head at the five screened intervals of the Pz-1 research piezometer. (b,c) Backward particle-tracking simulations illustrating preferential flow paths and groundwater travel times from the deepest and shallowest screened intervals, respectively.

In contrast, during the rainy months between April and November 2024, an inversion of the vertical hydraulic gradients was observed, with the shallow intervals recording higher piezometric levels than the deeper ones. This behavior indicates the occurrence of downward vertical flow consistent with local recharge processes associated with rainfall events.

The particle-tracking analysis revealed a predominantly horizontal flow pattern, with minor vertical components, suggesting lateral connectivity within the intercepted stratigraphic levels. This observation supports the hypothesis that horizontal hydraulic conductivity exceeds the vertical component. Regarding transit times, values greater than 800 years were identified for particles entering from the eastern boundary of the model and reaching the deepest screened interval, located between 260 and 266 m below the ground surface (Figure 12b). This interval corresponds to the deepest portion of unit U3 of the Real Group. In contrast, particles reaching the shallowest interval, located between 55 and 58 m within the most conductive zone of the Quaternary deposits, exhibited shorter transit times, with a maximum of approximately 60 years (Figure 12c). This behavior indicates that the captured groundwater is young, highlighting the vulnerability of the system to surface contamination and reinforcing the presence of active recharge processes that facilitate the infiltration of pollutants identified in the study area [93,94].

The results of the hydrochemical analyses conducted in the study area show correspondence with the simulated hydrodynamic behavior, particularly with the local recharge processes and short transit times that characterize the shallow Quaternary units. The presence of downward vertical gradients during the rainy season, together with the young groundwater ages estimated through the particle-tracking simulations, is consistent with the physicochemical and microbiological analyses performed in the area. This correspondence supports the interpretation that the shallow units respond rapidly to surface inputs through infiltration and emphasizes the need to incorporate vertical flow dynamics when assessing aquifer vulnerability under anthropogenic pressures.

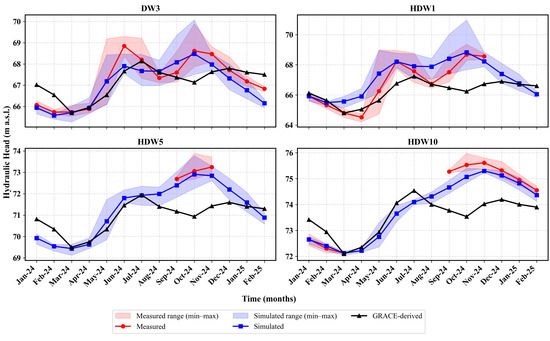

To complement the evaluation of the transient model and address the limitations derived from both the low temporal availability of piezometric records and the scarcity of instrumented wells in the study area, an additional analysis was incorporated based on monthly groundwater-level variations estimated from GRACE and GRACE-FO products. These estimates, derived from monthly total water storage (ΔTWS) anomalies and converted into groundwater-level variations following the methodology described in Section 2.4.7, provide an integrated hydrological signal at the regional scale that, although unable to capture local processes due to its spatial resolution (approximately 0.5°), constitutes an independent reference for assessing the temporal coherence of the simulated fluctuations.

The evaluation was conducted by comparing the following datasets: (1) groundwater levels measured daily by dataloggers and subsequently averaged to obtain a monthly series, including their observed range (minimum to maximum); (2) groundwater levels simulated by the numerical model, also expressed on a monthly basis and indicating their maximum and minimum values; and (3) groundwater-level variations derived from GRACE for wells DW3, HDW1, HDW5 and HDW10. Overall, a clear seasonal coherence is identified among the three datasets, with rising groundwater levels during the periods of higher precipitation (April to May and September to November) and declines during the dry months (January to February and July), consistent with the bimodal rainfall regime of the Middle Magdalena Valley. This seasonal coincidence between GRACE and the numerical model supports the ability of the model to adequately reproduce the temporal dynamics of the system at the regional scale (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Monthly comparison between measured groundwater levels (with observed minimum–maximum range), simulated groundwater levels (with simulated minimum–maximum range), and GRACE-derived groundwater-level variations for wells DW3, HDW1, HDW5 and HDW10.

The groundwater-level variations estimated from GRACE [95] clearly reflect the bimodal signal associated with the precipitation regime, which is consistent with its regional nature and with the behavior observed in wells intercepting deeper units connected to regional flow systems, such as DW3. A similar pattern is observed at HDW1, a well that is not routinely exploited and is located less than 400 m from the Yarirí wetland. Its hydrodynamic behavior is strongly influenced by the surface–water dynamics of the wetland, which explains its coherence with the bimodal cycle.

However, a relevant difference is identified in the synchronization of the second rainy-season peak. While the measured and simulated series show their maximum around November, the variations derived from GRACE exhibit a second peak shifted toward December. This lag may be attributed to the fact that the local series, both measured and simulated, reflect a faster response of the system to precipitation events, mainly associated with local recharge processes, whereas the GRACE signal integrates hydrological responses at the regional scale and exhibits an additional delay associated with storage in the unsaturated zone and with its spatial resolution. This behavior is also observed in the other analyzed wells, HDW5 and HDW10, and clearly highlights the local effects captured by the model in contrast to the integrated regional signal represented by GRACE.

4. Conclusions

In this study, a local numerical model was implemented under steady-state and transient conditions to simulate groundwater flow within the Neogene–Quaternary aquifer system of the Middle Magdalena Valley, focused on the Puerto Wilches sector. This area shows vulnerability to anthropogenic contamination processes, mainly from coliforms and nitrates, creating a risk scenario for groundwater quality, as confirmed by physicochemical analyses that detected the presence of these pollutants.

The numerical simulation of the aquifer system confirmed a regional groundwater flow pattern oriented east to west, with discharge into the main surface drainage features, particularly the Magdalena River and the Yarirí wetland. The steady-state water balance indicated that recharge mainly occurs through direct infiltration of precipitation, while discharge is related to surface outflows and river–aquifer exchange processes. The transient analysis revealed seasonal variations in vertical hydraulic gradients, indicating upward flow from deeper to shallower units during dry periods, and downward flow associated with local recharge during wet periods. This seasonal behavior demonstrates the system response to rainfall regimes and highlights the relevance of recharge processes in the dynamics of subsurface flow at the local scale.

The particle-tracking analysis showed predominantly horizontal flow paths with contrasting travel times among screened intervals. In the deeper intervals, associated with unit U3 of the Real Group, transit times were greater than 800 years, while in the shallow intervals values were close to 60 years. This behavior indicates that the Quaternary deposits, from which most of the rural population in the study area extracts groundwater for human consumption, are highly vulnerable to contamination caused by the infiltration of pollutants related to local recharge processes, particularly during the rainy periods.

This research represents an effort to evaluate the hydrodynamic behavior of a tropical aquifer system in a developing country subjected to anthropogenic pressures and used for human consumption as well as agricultural and livestock activities. However, institutional efforts for groundwater monitoring need to be strengthened at national and regional levels through the implementation of multipurpose networks that integrate systematic monitoring of both quantity and quality. These networks should include regular analyses of emerging contaminants and hydrocarbons, since the area has been proposed as a potential pilot site for unconventional hydrocarbon extraction activities, which increases the need for preventive groundwater quality monitoring.

In this context, additional studies are required to improve the understanding of the processes occurring in this area at different scales, through the application of stochastic modeling approaches that help to reduce predictive uncertainty. Such studies should include climate change scenarios that may alter hydrogeological patterns and, consequently, allow a more accurate assessment of the vulnerability of the aquifer system under these conditions. It is also necessary to implement contaminant transport models that address specific pollutants, including those associated with the oil and gas industry, as well as pesticides, herbicides, fertilizers, and organic matter derived from the inadequate disposal of fecal waste and domestic wastewater.

In this context, additional studies are required to improve the understanding of the processes occurring in this area at different scales, through the application of stochastic modeling approaches that help to reduce predictive uncertainty. Such studies should also incorporate climate change scenarios that may alter hydrogeological patterns and, consequently, enable a more accurate assessment of aquifer vulnerability under future conditions. Furthermore, it is necessary to implement contaminant transport models that address specific pollutants, including those associated with the oil and gas industry, as well as pesticides, herbicides, fertilizers and organic matter derived from the inadequate disposal of fecal waste and domestic wastewater.

The use of GRACE data represents a promising tool for the evaluation and validation of hydrogeological models in regions where the availability of continuous piezometric records is limited or the coverage of instrumented wells is insufficient. GRACE makes it possible to extend the temporal validation of the model beyond the periods covered by field-measured data. Although its spatial resolution does not allow these products to be used forrfffr the calibration of local hydrogeological models, the groundwater-level estimates derived from GRACE provide an additional input that can strengthen calibration processes in numerical models at regional scale, particularly those aimed at reproducing the general hydrological dynamics of systems where variations in groundwater storage dominate the hydrodynamic response.

The reduction of aquifer vulnerability to contamination is a key component for the sustainable management of groundwater in the region. The model results and the hydrogeological analysis demonstrate the need to complement scientific advances with concrete actions for mitigation, monitoring, and control. Strengthening rural sanitation infrastructure is a priority through the implementation of low-cost local drinking water treatment systems, expansion of sewerage coverage, and improvement of domestic wastewater treatment. In the agricultural sector, sustainable practices should be promoted to optimize the use of fertilizers and pesticides, reducing contaminant infiltration and runoff toward shallow aquifers. These measures, combined with continuous environmental education programs and community participation initiatives, are essential to enhance water governance and ensure the long-term sustainability of the aquifer system under current and future challenges.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization of the study. B.L.-A. prepared the original draft of the manuscript; B.L.-A., L.S.V., A.P. and J.P. developed the conceptual model; B.L.-A., M.V. and J.L. contributed to the development of the monitoring nest, particularly supporting the drilling and installation of the piezometers. B.L.-A. developed the numerical model. L.D.D. and B.L.-A. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was conducted as part of the MEGIA project—Multiscale Water Management Model with Uncertainty Analysis for the Strategic Environmental Assessment of the Hydrocarbon Subsector in the Middle Magdalena Valley. The project was funded by the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (MinCiencias) and the National Hydrocarbons Agency (ANH) of Colombia: FP44842-157-2018.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in this study are openly available at https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1479MttI0gCZegEym_8J2fb-WjZmwfKEc?usp=drive_link.

Acknowledgments

The researchers thank the MEGIA Research Project, Contingent Recovery Contract FP44842-157-2018 funded by Minciencias and the National Hydrocarbons Agency. Special thanks are extended to the members of the HYDS Research Group, particularly to Joshua Rendón, for his valuable support in the analysis of physicochemical information used in this study. The authors also thank DHI WASY for providing a student license for FEFLOW v.8.1, which supported the development of the numerical model.

Conflicts of Interest

This manuscript is an original work that has not been published previously and is not under review elsewhere. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version for submission to Water. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Carrard, N.; Foster, T.; Willetts, J. Groundwater as a source of drinking water in southeast Asia and the Pacific: A multi-country review of current reliance and resource concerns. Water 2019, 11, 1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Gun, J. Groundwater resources sustainability. In Global Groundwater; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 331–345. [Google Scholar]

- Vrba, J.; van der Gun, J. The World’s Groundwater Resources; World Water Development Report 2, Contribution to Chapter 4, Report IP 2004-1; International Groundwater Resources Assessment Centre (IGRAC): Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2004; Volume 2, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ravindiran, G.; Rajamanickam, S.; Sivarethinamohan, S.; Balamurugan, K.S.; Ravindran, G.; Muniasamy, S.K.; Hayder, G. A review of the status, effects, prevention, and remediation of groundwater contamination for sustainable environment. Water 2023, 15, 3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, N.; Ishak, M.I.S.; Bhawani, S.A.; Umar, K. Various natural and anthropogenic factors responsible for water quality degradation: A review. Water 2021, 13, 2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syafiuddin, A.; Boopathy, R.; Hadibarata, T. Challenges and solutions for sustainable groundwater usage: Pollution control and integrated management. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2020, 6, 310–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, N.; Folch, A.; Lane, M.; Olago, D.; Katuva, J.; Thomson, P.; Jou, S.; Hope, R.; Custodio, E. How does water-reliant industry affect groundwater systems in coastal Kenya? Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 694, 133634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Adesina, J.A. Integrated watershed management framework and groundwater resources in Africa—A review of West Africa sub-region. Water 2022, 14, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaye, C.B.; Tindimugaya, C. Challenges and opportunities for sustainable groundwater management in Africa. Hydrogeol. J. 2019, 27, 1099–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román-Chaverra, D.; Lora-Ariza, B.; Vargas, O.M.; Cubillos, C.E.; García, M.; Ramírez, J.M.; Niño, O.P.; Aguirre, S. Programa Nacional de Monitoreo del Recurso Hídrico; Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible; IDEAM; Universidad Nacional de Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2023; ISBN 978-628-7598-24-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ngendahayo, E.; Nilsson, E.; Barmen, G.; Wali, U.G.; Larson, M.; Nsabimana, A.; Persson, K.M. Current groundwater monitoring practices in Rwanda and recommendations for enhancing knowledge of groundwater resources. Hydrogeol. J. 2025, 33, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorza Ríos, D.A.; Torres Socha, A.M. Análisis de la Política Nacional para la Gestión Integral del recurso Hídrico con Relación a la Planificación y Manejo del Recurso Hídrico Subterráneo en Colombia; FAO: Dublin, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Norouzi Khatiri, K.; Nematollahi, B.; Hafeziyeh, S.; Niksokhan, M.H.; Nikoo, M.R.; Al-Rawas, G. Groundwater management and allocation models: A review. Water 2023, 15, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareta, K. Groundwater contamination modelling in Ayad River Basin, Udaipur. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliva, R.G. Aquifer Characterization Techniques; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- Izady, A.; Davary, K.; Alizadeh, A.; Ziaei, A.N.; Alipoor, A.; Joodavi, A.; Brusseau, M.L. A framework toward developing a groundwater conceptual model. Arab. J. Geosci. 2014, 7, 3611–3631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.P.; Woessner, W.W.; Hunt, R.J. Applied Groundwater Modeling: Simulation of Flow and Advective Transport; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bredehoeft, J. The conceptualization model problem—Surprise. Hydrogeol. J. 2005, 13, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushton, K.R. Groundwater Hydrology: Conceptual and Computational Models; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zarinmehr, H.; Tizro, A.T.; Fryar, A.E.; Pour, M.K.; Fasihi, R. Prediction of groundwater level variations based on gravity recovery and climate experiment (GRACE) satellite data and a time-series analysis: A case study in the Lake Urmia basin, Iran. Environ. Earth Sci. 2022, 81, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Cazenave, A.; Dahle, C.; Llovel, W.; Panet, I.; Pfeffer, J.; Moreira, L. Applications and challenges of GRACE and GRACE follow-on satellite gravimetry. Surv. Geophys. 2022, 43, 305–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xiang, L.; Steffen, H.; Wu, P.; Jiang, L.; Shen, Q.; Li, Z.; Hayashi, M. GRACE-based estimates of groundwater variations over North America from 2002 to 2017. Geod. Geodyn. 2022, 13, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solovey, T.; Śliwińska-Bronowicz, J.; Janica, R.; Brzezińska, A. Assessment of the effectiveness of GRACE observations in monitoring groundwater storage in Poland. Water Resour. Res. 2025, 61, e2024WR038888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, W. A review of regional groundwater flow modeling. Geosci. Front. 2011, 2, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano Hernández, B.L.; Marín Celestino, A.E.; Martínez Cruz, D.A.; Ramos Leal, J.A.; Hernández Pérez, E.; García Pazos, J.; Almanza Tovar, O.G. A systematic review of the current state of numerical groundwater modeling in American Countries: Challenges and future research. Hydrology 2024, 11, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebraheem, A.M.; Riad, S.; Wycisk, P.; Sefelnasr, A.M. A local-scale groundwater flow model for groundwater resources management in Dakhla Oasis, SW Egypt. Hydrogeol. J. 2004, 12, 714–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, G.; Lincker, M.; Sessini, A.; Carletti, A. Numerical Groundwater Model to Assess the Fate of Nitrates in the Coastal Aquifer of Arborea (Sardinia, Italy). Water 2024, 16, 2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, S.M.; Ray, A.K.; Barghi, S. Water pollution and agriculture pesticide. Clean Technol. 2022, 4, 1088–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe, N.; Srinivasan, R.; Corzo, G.; Arango, D.; Solomatine, D. Spatio-temporal critical source area patterns of runoff pollution from agricultural practices in the Colombian Andes. Ecol. Eng. 2020, 149, 105810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lora-Ariza, B.; Piña, A.; Donado, L.D. Assessment of groundwater quality for human consumption and its health risks in the Middle Magdalena Valley, Colombia. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Craswell, E. Fertilizers and nitrate pollution of surface and ground water: An increasingly pervasive global problem. SN Appl. Sci. 2021, 3, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranguren-Díaz, Y.; Galán-Freyle, N.J.; Guerra, A.; Manares-Romero, A.; Pacheco-Londoño, L.C.; Romero-Coronado, A.; Vidal-Figueroa, N.; Machado-Sierra, E. Aquifers and groundwater: Challenges and opportunities in water resource management in Colombia. Water 2024, 16, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agah, A.; Doulati Ardejani, F.; Shehab, M.; Butscher, C.; Taherdangkoo, R. Modeling Hydrocarbon Plume Dynamics in Shallow Groundwater of the Rey Industrial Area, Iran: Implications for Remediation Planning. Water 2025, 17, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radelyuk, I.; Naseri-Rad, M.; Hashemi, H.; Persson, M.; Berndtsson, R.; Yelubay, M.; Tussupova, K. Assessing data-scarce contaminated groundwater sites surrounding petrochemical industries. Environ. Earth Sci. 2021, 80, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piña, A.; Donado, L.D.; Silva, L.; Pescador, J. Seasonal and deep groundwater-surface water interactions in the tropical Middle Magdalena River basin of Colombia. Hydrol. Process. 2022, 36, e14764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lora-Ariza, B.; Silva Vargas, L.; Donado, L.D. Estimation of Hydraulic Conductivity from Well Logs for the Parameterization of Heterogeneous Multilayer Aquifer Systems. Water 2025, 17, 2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granados Cabrera, Ó.A.; Rincón Romero, V.O.; Arango Ospina, M.E.; Arias Arias, N.A. Palma de aceite en Puerto Wilches: Actores y procesos de transformación (1960–2016). Anu. De Hist. Reg. Y De Las Front. 2021, 26, 111–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vides Bossio, A.C.; Alarcón Arias, L.M. Análisis de las Consecuencias Ambientales por la Implementación del Fracking en Puerto Wilches, Colombia, del 2019 a 2022. 2023. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11349/40331 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Pérez García, C.A. Análisis del Sistema Agroalimentario Implementado en las Comunidades con Situación de Vulnerabilidad Socioeconómica para Determinar los Efectos en la Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutricional en Puerto Wilches. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Santo Tomás, Bucaramanga, Colombia, 2023. Available online: https://repository.usta.edu.co/items/5c81764d-ba6c-40c3-93e8-b26031b74a45 (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Fonseca, H.; Fuquen, J.; Mesa, L.; Talero, C.; Pérez, O.; Porras, J.; Gavidia, O.; Pacheco, S.; Amaya, E.; García, Y.; et al. Cartografía Geológica de la Plancha 108—“Puerto Wilches”; Servicio Geológico Colombiano y Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2012. Available online: https://recordcenter.sgc.gov.co/B13/23008010024507/mapa/pdf/2105245071300002.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Sarmiento, G.; Puentes, J.; Sierra, C. Evolución geológica y estratigrafía del sector norte del Valle Medio del Magdalena. Geol. Norandina 2015, 12, 51–82. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas Quintero, J.A. Modelamiento de la estructura resistiva del Valle Medio del Magdalena a partir de la interpretación de estudios magnetotelúricos. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, E.; Sánchez, I.; Duque, N.; Arboleda, P.; Vega, C.; Zamora, D.; López, P.; Kaune, A.; Werner, M.; García, C.; et al. Combined use of local and global hydro meteorological data with hydrological models for water resources management in the Magdalena-Cauca Macro Basin–Colombia. Water Resour. Manag. 2020, 34, 2179–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hu, Z.-Z.; Tseng, Y.-H.; Liu, Y.; Liang, P. A historical perspective of the La Niña event in 2020/2021. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2022, 127, e2021JD035546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto de Hidrología, Meteorología y Estudios Ambientales (IDEAM); Instituto de Investigaciones Marinas y Costeras José Benito Vives de Andréis (INVEMAR). Protocolo de Monitoreo y Seguimiento del Agua; IDEAM: Bogotá, Colombia, 2021; ISBN 978-958-5489-24-0.

- NTC-ISO 5667-1:2010; Calidad del Agua—Muestreo—Parte 1: Directrices para el Diseño de Programas y Técnicas de Muestreo. Norma Técnica Colombiana Equivalente a ISO 5667-1:2006. ICONTEC—Instituto Colombiano de Normas Técnicas y Certificación: Bogotá, Colombia, 2010.

- Rice, E.W.; Baird, R.B.; Eaton, A.D.; Clesceri, L.S. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 22nd ed.; American Public Health Association (APHA), American Water Works Association (AWWA), Water Environment Federation (WEF): Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Zeng, X. Review of the uncertainty analysis of groundwater numerical simulation. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2013, 58, 3044–3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]