Abstract

Treating wastewater with a low carbon-to-nitrogen (C/N) ratio remains a major challenge for conventional biological processes because insufficient organic carbon limits heterotrophic denitrification. To address this issue, microalgae-based photobioreactors offer a sustainable alternative that couples nutrient removal with biomass valorization. This study systematically evaluated the effects of four key operational parameters—initial inoculum density, aeration rate, light intensity, and photoperiod—on nutrient removal, biomass productivity, and metabolite accumulation of Auxenochlorella pyrenoidosa (A. pyrenoidosa) treating synthetic low C/N wastewater. Optimal operating conditions were identified as an initial OD680 of 0.1, aeration rate of 2 L air min−1, light intensity of 112 μmol m−2 s−1, and a 16L:8D photoperiod. Under these conditions, the photobioreactor achieved 86.35% total nitrogen and 98.43% total phosphorus removal within 11 days while producing biomass rich in proteins, polysaccharides, and lipids. Metagenomic analysis revealed a metabolic transition from denitrification-driven pathways during early operation to assimilation-dominated nitrogen metabolism under optimized conditions, emphasizing the synergistic interactions within algal–bacterial consortia. These findings demonstrate that optimized A. pyrenoidosa-based photobioreactors can effectively recover nutrients and produce valuable biomass, offering a viable and sustainable solution for the treatment of low C/N wastewater.

1. Introduction

The rapid expansion of global population and industrialization has placed mounting pressure on water resources and wastewater management systems. A particular challenge lies in the treatment of effluents with low carbon-to-nitrogen (C/N) ratios, commonly originating from advanced biological nitrogen removal processes in municipal wastewater treatment plants [1]. These effluents contain insufficient organic carbon to sustain conventional heterotrophic denitrification [2], necessitating alternative treatment strategies that are both environmentally sustainable and economically viable. Recent studies have highlighted that low-C/N wastewater treatment requires integrated biological processes capable of coupling nutrient removal with biomass recovery. For instance, Satiro et al. [3] demonstrated in a pilot-scale high-rate pond system that inoculation of a microalgae–bacteria consortium significantly improved nitrogen and phosphorus removal, providing practical evidence of the role of initial inoculum and community composition in driving system performance. This underscores the importance of operational and biological factors in shaping overall treatment efficiency.

Among the proposed solutions, microalgae-based photobioreactors have attracted significant attention for their dual role in nutrient removal and biomass valorization. Microalgae such as Chlorella spp. can directly assimilate inorganic nitrogen and phosphorus, eliminating the need for an external organic carbon [4]. Additionally, photosynthetic CO2 fixation during algal growth offers potential for carbon sequestration, enhancing the sustainability of algal biotechnology [5]. In particular, Chlorella species exhibit robust adaptability, high nutrient uptake efficiency, and tolerance to variable wastewater matrices [4,6,7]. Prior pilot-scale work has verified the feasibility of such systems for integrated nutrient removal and biomass production [8]. The industrial scalability and real-world relevance of algal-based treatment technologies have also been demonstrated in hybrid systems. Recent reported that integrating photobioreactors with constructed wetlands effectively treated complex paper-pulp industry effluents, achieving simultaneous nutrient recovery and effluent polishing [9]. These advances reinforce the potential of photobioreactors as core units in circular, nature-based wastewater management frameworks.

However, under low C/N conditions, limited organic carbon severely constrains cellular carbon flux and alters the metabolic balance between autotrophic, heterotrophic, and mixotrophic pathways. Insufficient carbon skeletons restrict the tricarboxylic acid cycle and amino acid biosynthesis, leading to reduced protein formation and a compensatory shift toward energy storage compounds such as lipids or carbohydrates. This imbalance disrupts the coordination between photosynthetic carbon fixation and nitrogen assimilation, ultimately diminishing growth and nutrient removal efficiency. Such conditions also intensify metabolic competition between algal and bacterial partners in mixed consortia, as both rely on overlapping carbon sources for growth and redox balance.

The interplay of key physical parameters—including aeration rate, light intensity, photoperiod, and inoculum density—plays a decisive role in mitigating these carbon-limiting effects. Aeration influences oxygen transfer, CO2 dissolution, and microbial respiration; light regulates energy supply and photosynthetic activity; while inoculum density governs self-shading, nutrient competition, and community stability. Prior studies have examined these parameters independently, yet few have comprehensively investigated their coupled effects under carbon-deficient conditions. Gao et al. [10] demonstrated that Chlorella growth and lipid accumulation vary with the total organic carbon to total nitrogen (TN) ratio, reinforcing the direct link between carbon availability and metabolic partitioning. Likewise, Diaz-Hernandez et al. [11] used data-driven modeling to predict optimal photobioreactor performance, underscoring the need for holistic parameter optimization. Furthermore, Chu et al. [12] recently showed that regulating operational symmetry between microalgae and bacteria in a membrane photobioreactor markedly enhanced nitrogen and phosphorus removal in low-C/N domestic wastewater while reducing antibiotic resistance gene propagation. Their findings emphasize that optimized physical parameters (light intensity, aeration, and photoperiod) can control microbial interactions and maintain consortium stability—principles directly relevant to the current study’s optimization strategy.

From a metabolic standpoint, low C/N stress amplifies competition for carbon skeletons between energy storage (lipid synthesis) and biomass growth (protein formation). This trade-off dictates whether assimilated nutrients are directed toward structural cell growth or stored macromolecules. Fine-tuning external conditions can steer this metabolic balance toward efficient nutrient assimilation and balanced biomass composition rather than excessive lipid accumulation. Understanding this metabolic plasticity provides the theoretical foundation for the multi-parameter optimization strategy employed herein. Light, in particular, is a dominant regulatory factor in algal–bacterial systems. Wang et al. [13] demonstrated that light intensity directly shapes community structure and metabolic pathways in algal–bacterial biofilm reactors, influencing both nitrogen conversion and photosynthetic capacity. Furthermore, recent proteomic and transcriptomic studies have revealed the molecular mechanisms underlying these physiological shifts. For instance, Chlorella vulgaris under nitrogen starvation exhibits upregulation of lipid biosynthesis genes while downregulating photosystem II and ribosomal protein pathways, reflecting reallocation of carbon and energy toward lipid accumulation [14,15]. Similarly, proteomic analyses of Auxenochlorella protothecoides (A. protothecoides) and Chromochloris zofingiensis (C. zofingiensis) have revealed the upregulation of triacylglycerol (TAG)–synthesizing enzymes and carbon fixation–related proteins under nutrient-limited conditions. In A. protothecoides, nitrogen starvation significantly upregulated diacylglycerol acyltransferase genes (ApDGAT1 and ApDGAT2b), which was closely correlated with enhanced TAG accumulation [16]. Likewise, in C. zofingiensis, nitrogen deprivation stimulated extensive TAG synthesis, accompanied by the enrichment of lipid metabolism–associated proteins within lipid droplets, including major lipid droplet proteins, caleosins, and lipases that facilitate TAG assembly [17]. These molecular insights provide a robust physiological basis for understanding carbon–nitrogen metabolic interactions in microalgae, reinforcing their suitability as model organisms for low C/N wastewater treatment.

Within algal–bacterial consortia, operational conditions further influence these molecular processes. Aeration and mixing affect oxygen dynamics and CO2 mass transfer, modulating bacterial nitrification–denitrification and algal photosynthesis coupling. Light intensity and photoperiod govern energy supply and circadian regulation, while inoculum density shapes the autotrophic–heterotrophic balance. Together, these parameters determine the degree of metabolic synergy within the consortium, ultimately affecting nutrient removal efficiency and biomass productivity under carbon limitation. From an application perspective, integration of optimized photobioreactors into wastewater treatment facilities offers a sustainable path toward nutrient recovery and resource reuse. Auxenochlorella pyrenoidosa (A. pyrenoidosa) stands out due to its high nutrient assimilation efficiency, stress tolerance, and capacity for simultaneous nutrient removal and value-added biomass generation [18,19]. This aligns with the recent shift toward nature-based engineered systems for industrial and municipal effluents [9], highlighting the relevance of optimizing operational parameters for scalability and environmental resilience.

This study addresses this knowledge gap by testing the hypothesis that under low C/N stress, microalgal cells experience intensified competition for carbon skeletons between energy storage (lipid synthesis) and biomass growth (protein formation). We further hypothesize that optimizing key operational parameters—including light intensity, aeration rate, inoculum density, and photoperiod—can modulate this metabolic balance, steering nutrient assimilation pathways and determining biomass composition and productivity. To validate this hypothesis, we systematically evaluate the interactive effects of these parameters on nutrient removal, biomass yield, and metabolite accumulation of A. pyrenoidosa treating synthetic low C/N wastewater. The results provide mechanistic insights into how environmental regulation can alleviate carbon limitation, enhance nutrient recovery, and promote sustainable wastewater treatment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microalgae Culture and Photobioreactors Construction

In this study, Auxenochlorella pyrenoidosa (A. pyrenoidosa, formerly Chlorella pyrenoidosa [20]) was obtained from the Algal Germplasm Bank at Shenzhen University. Seed cultures were maintained in Blue-Green 11 (BG-11) medium (250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks with 100 mL working volume) at 25 ± 1 °C under a 12L:12D photoperiod and 83 µmol m−2 s−1 illumination from daylight fluorescent lamps. Scaled-up cultivation was performed in 1 L sterile glass bottles containing 800 mL BG-11, continuously aerated with filtered air through electromagnetic pumps. Log-phase cultures (The optical density measured at a wavelength of 680 nm (OD680) ≈ 1.5) were harvested by centrifugation (5000 rpm, 5 min, 4 °C), washed twice with ultrapure water, and resuspended in synthetic wastewater to the desired OD680. To ensure realistic microbial interactions, all operations were intentionally conducted under non-sterile conditions, following the rationale of Satiro et al. [3] and Chu et al. [12], who emphasized that open or semi-open algal–bacterial systems better replicate environmental consortia and enable natural co-development of heterotrophic bacteria.

The photobioreactor consisted of transparent acrylic cylinders (20 cm diameter, 30 cm height), equipped with three adjustable 15 W LED tubes. Light intensity and photoperiod were monitored using an MQ-500 light meter (Apogee Instruments, Logan, UT, USA) and controlled by a programmable timer. Aeration was provided from the bottom via diffusers connected to glass rotameters and electromagnetic compressors (ACO-318, HAILEA, Raoping, China), ensuring homogeneous mixing and CO2 supply.

2.2. Operating Conditions

Photobioreactors were operated indoors under controlled temperature (25 ± 1 °C) to evaluate the effects of initial inoculum density, aeration rate, light intensity, and photoperiod on system performance. Synthetic wastewater simulating low C/N effluent was prepared by dissolving analytical-grade NH4Cl, NaNO3, KH2PO4, K2HPO4, and glucose in tap water, yielding ≈ 5 mg L−1 NH4+–N, 10 mg L−1 NO3−–N, 1 mg L−1 TP, and 30 mg L−1 COD. Although typical secondary effluents usually contain low ammonia and relatively high nitrate concentrations, the inclusion of a measurable NH4+–N fraction (5 mg/L) in this study was intentional. This adjustment aimed to simulate post-denitrification or partial nitrification effluents, where residual ammonium frequently coexists with nitrate, providing a more representative nitrogen spectrum for assessing algal–bacterial nitrogen transformation dynamics. Similar synthetic wastewater compositions have been employed in previous laboratory-scale studies investigating nitrogen metabolism in photobioreactor and algal–bacterial systems [12,21]. Each reactor contained 5.0 L working volume at start-up. The algal suspension was evenly distributed into triplicate reactors at target OD680 values (0.1, 0.2, 0.4) according to experimental design. Aeration rates (1, 2, 4 L min−1) were set using calibrated rotameters (LZB-3WB, Xinghua Xiangjin Flow Instrument Co., Ltd., Taizhou, Jiangsu, China). Light intensities (28 ± 1, 68 ± 4, 112 ± 4 µmol m−2 s−1) and photoperiods (8L:16D, 12L:12D, 16L:8D) were controlled by LED timers. The parameter effects were examined using a one-factor-at-a-time approach to isolate independent impacts under constant conditions. The chosen illumination range and photoperiod were supported by Wang et al. [13], who demonstrated that light intensity between 30 and 120 µmol m−2 s−1 optimizes photosynthetic activity and nitrogen removal in algal–bacterial reactors. Similarly, Satiro et al. [9] validated controlled photoperiod operation (12L:12D and 16L:8D) in industrial wastewater photobioreactors, providing an engineering precedent. The aeration rates of 1, 2, and 4 L min−1 were chosen based on their influence on CO2 availability and mass transfer efficiency. Previous studies have highlighted that moderate aeration rates (1–4 L min−1) optimize algal growth and nutrient removal, avoiding excessive CO2 stripping while maintaining sufficient oxygen supply for photosynthesis [22,23,24].

Although the wastewater medium was prepared using tap water and analytical-grade reagents, no sterilization was performed prior to inoculation. Continuous aeration through 0.22 µm filters minimized particle entry while allowing native microorganisms to colonize the system. Similar approaches have been reported in previous studies investigating algal–bacterial photobioreactors operated under open or semi-open conditions [21,25]. This design choice, mirroring Chu et al. [12], facilitates the spontaneous formation of algal–bacterial consortia typical of real treatment plants and supports dynamic co-metabolic processes such as nitrification and denitrification. The detailed construction and operation of the photobioreactor are described in our previously published study [26]. However, unlike that study, which focused on the microalga Tetradesmus obliquus, the present work investigates Auxenochlorella pyrenoidosa as the functional strain. The two species differ markedly in cellular morphology, metabolic regulation, and nitrogen assimilation capacity. Moreover, all data presented in this study are newly obtained, and the work specifically highlights the optimization of operational parameters and the metabolic transitions associated with algal–bacterial interactions under low C/N conditions, thereby providing new mechanistic insights distinct from our previous publication.

2.3. Sampling and Analytical Methods

2.3.1. Physicochemical Analysis

Daily, 100 mL of mixed liquor was collected from each reactor. Fifty milliliters were filtered (0.45 µm) for analysis of NH4+–N, NO2−–N, NO3−–N, TN, TP, and COD using Chinese Standard Methods [27]; the remaining portion was used to determine dry weight and chlorophyll a content (via freeze–thaw acetone extraction). OD680 was measured daily with a UV-5100 spectrophotometer (Metash, Shanghai, China). All tests were performed in triplicate. Dissolved organic carbon (DOC) was quantified by high-temperature catalytic oxidation (680 °C) using a Shimadzu TOC-LCPH/CPN analyzer (Kyoto, Japan). pH, DO, and conductivity were monitored in situ (Orion Star A329, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.3.2. Biomass and Biochemical Composition

A of algal suspension were filtered (0.45 µm membrane). The filter was folded and stored at −20 °C in darkness. Chlorophyll a was extracted in 90% acetone and quantified spectrophotometrically [28]. Dry weight was measured gravimetrically after drying filters at 65 °C to constant weight [29]. At the end of each run, biomass was centrifuged (4000 rpm, 5 min), oven-dried (60 °C), and ground. Protein content was determined via BCA assay (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China) [30]; carbohydrates via phenol–sulfuric acid method [31]; lipids by chloroform–methanol extraction [32]. Specific growth rate (μ, d−1) of T. obliquus was calculated according to Equation (1):

where N1 and N2 represent the biomass (dry weight) o at times T1 and T2 (days), respectively.

μ = (lnN2 − lnN1)/(T2 − T1)

2.4. Metagenomic Analyses

Biomass samples collected on days 1, 5, and 11 were centrifuged, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen (60 s), and stored at −80 °C. DNA was extracted and sequenced (Majorbio Bio-pharm Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). Sequencing integrity was checked via 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, and data were analyzed on the Majorbio Cloud Platform (https://cloud.majorbio.com/page/tools/, accessed on 2 August 2025).

2.5. Data Processing

Differences in nutrient removal, biomass production, and community composition across operational phases were analyzed by one-way ANOVA (SPSS v26.0, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Microbial taxonomic variance was evaluated using R (v3.3.1). Sequence clustering (CD-HIT v4.6.1) and KEGG annotation (DIAMOND v0.8.35) were used to calculate relative enzyme and KO abundances for N and P metabolism. Gene abundance was expressed as RPKM. Mantel tests (Spearman method) quantified correlations between pathway gene sets and seven environmental variables (pH, NH4+–N, NO3−–N, NO2−–N, TN, TP, DOC). Differential expression analyses were performed using the stats package in R (v3.3.1).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effects of Different Environmental Factors on the Algal Growth and Nutrient Removals

3.1.1. Initial Inoculation Concentration and Aeration Rates

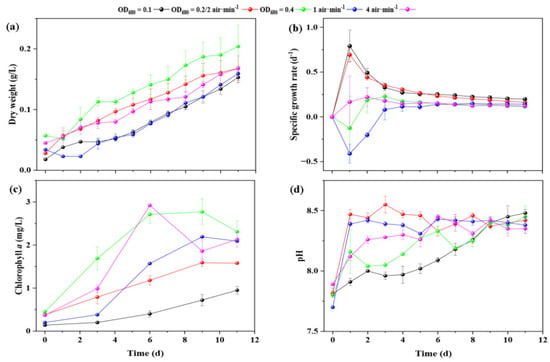

In this study, the effects of inoculum density and aeration rate on the growth of A. pyrenoidosa were evaluated. Parameters such as dry weight, specific growth rate, chlorophyll content, and pH were used to assess the microalgae’s response to these conditions (Figure 1). As shown in Figure 1a, both initial inoculum density and aeration rate significantly affected biomass accumulation. The initial dry weights were 0.018 g/L (OD680 = 0.1), 0.028 g/L (OD680 = 0.2), and 0.057 g/L (OD680 = 0.4). During cultivation, total biomass increased in all groups, with the highest final dry weight observed at OD680 = 0.4 (0.204 g L−1 on day 11), followed by OD680 = 0.2 (0.168 g L−1) and OD680 = 0.1 (0.153 g L−1). However, this higher final biomass mainly reflects the larger initial cell load rather than superior growth performance, as supported by the specific growth rate analysis described below. Aeration also influenced biomass productivity: cultures aerated at 2 and 4 L min−1 reached comparable dry weights (~0.168 g L−1), whereas 1 L min−1 yielded lower biomass (0.159 g L−1). This suggests that moderate aeration (2 L min−1) ensured adequate CO2 transfer and mixing without imposing shear stress or unnecessary energy use, indicating an optimal aeration threshold. The specific growth rate data (Figure 1b) revealed distinct physiological responses among inoculum groups. At day 1, the OD680 = 0.1 and 0.2 cultures exhibited rapid growth rate of 0.79 d−1 and 0.69 d−1, respectively, whereas the OD680 = 0.4 culture showed a negative growth rate (−0.13 d−1). The initial decline at high density indicates a lag phase caused by self-shading, oxygen supersaturation, and nutrient competition, which temporarily suppressed photosynthetic activity. After day 4, all groups approached similar apparent rates due to the onset of stationary conditions; however, the OD680 = 0.1 culture maintained a higher steady-state growth rate (0.20 d−1 on day 11) and more consistent nutrient removal efficiency, indicating sustained metabolic activity compared to high-density cultures. These results collectively indicate that while higher inoculum densities may accelerate early biomass accumulation through a larger initial population, they eventually experience growth inhibition due to restricted light penetration, local nutrient depletion, and oxygen oversaturation [33]. Therefore, the convergence in growth rates after day 4 likely represents a balance between nutrient limitation and self-shading effects across treatments, rather than a uniform physiological response. Moreover, the apparent increase in total biomass at OD680 = 0.4 could also partly arise from the proliferation of heterotrophic bacteria supported by organic exudates from stressed algal cells, rather than active algal growth per se. In contrast, lower inoculum densities facilitate uniform light distribution and sustained carbon and nitrogen uptake, thereby prolonging the exponential phase and enhancing long-term system stability.

Figure 1.

Temporal dynamics of biomass, specific growth rate, chlorophyll a, and pH in the algal–bacterial symbiotic system operated under varying initial inoculum densities and aeration rates. (a) Variations in dry weight; (b) variations in specific growth rate; (c) variations in chlorophyll a content; (d) variations in pH. “Time (d)” denotes the duration of reactor operation in days. The red line corresponds to the treatment with an initial inoculum density of OD680 = 0.2 and an aeration rate of 2 L min−1.

Chlorophyll a content (Figure 1c) followed a similar pattern. The OD680 = 0.4 group showed the highest absolute chlorophyll a concentration (2.31 mg L−1 on day 11), yet its normalized chlorophyll a per unit biomass declined in later stages, reflecting a shift from active photosynthesis to maintenance metabolism under nutrient depletion. This supports the interpretation that elevated chlorophyll levels at high inoculum density result from cell concentration rather than higher photosynthetic efficiency. For aeration, higher rates generally enhanced chlorophyll a accumulation owing to improved CO2 availability and gas–liquid mass transfer. At 4 L min−1, chlorophyll a reached 2.13 mg L−1, compared with 1.58 mg L−1 at 2 L min−1 and 2.09 mg L−1 at 1 L min−1. Beyond 2 L min−1, further aeration offered negligible benefits, indicating diminishing returns once CO2 saturation was achieved. This suggests that improved CO2 availability and enhanced mass transfer under suitable aeration rates contribute to more efficient photosynthesis [34]. The pH data (Figure 1d) increased gradually across all treatments, consistent with CO2 uptake and bicarbonate formation during photosynthesis. The rise was more pronounced in reactors with higher inoculum densities, indicating higher CO2 fixation rates early in cultivation. Conversely, cultures with lower aeration exhibited larger pH shifts, likely due to limited CO2 buffering. These findings align with prior reports that CO2 concentration modulates key enzymes such as carbonic anhydrase and Rubisco, thereby influencing photosynthetic efficiency [35,36]. As cultivation progressed, the pH values of all experimental groups gradually converged during the later phase. This convergence can be attributed to the stabilization of algal metabolic activity and the dynamic equilibrium established between CO2 fixation and release as the system approached steady-state conditions. In the early and middle stages, differences in inoculum density and aeration rate caused distinct CO2 dynamics and pH fluctuations; however, once nutrient availability declined and algal growth slowed, respiration and photosynthetic CO2 uptake became balanced, leading to similar final pH levels across treatments. This convergence therefore reflects a transition from active exponential growth to a quasi-stationary metabolic equilibrium rather than identical physiological behavior under all conditions.

Taken together, these observations demonstrate that an initial inoculum density of OD680 = 0.1, combined with an aeration rate of 2 L min−1, provides the most balanced condition—ensuring sufficient light and nutrient availability while minimizing mass-transfer limitations. This combination supports steady biomass growth, efficient nutrient removal, and prolonged photobioreactor stability under low C/N conditions.

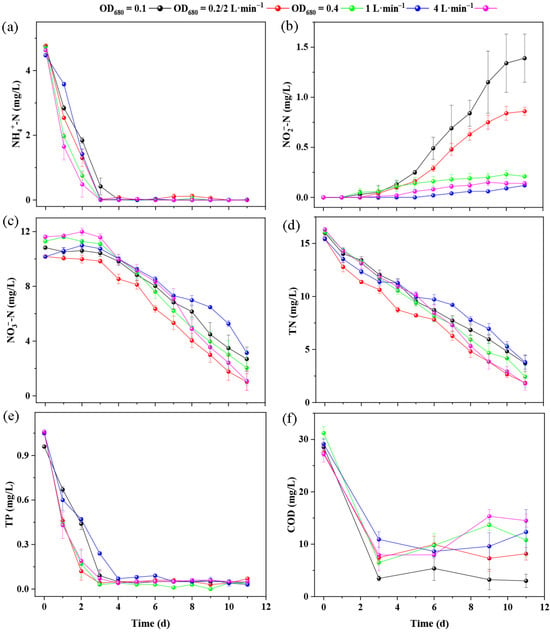

At OD680 = 0.2, NH4+–N was rapidly reduced to 0.02 mg L−1 by day 3, accompanied by a marked decrease in NO3−–N from an initial 10.17 mg L−1 to 1.02 mg L−1 on day 11, resulting in the highest total nitrogen (TN) removal efficiency of 87.54%. In contrast, the OD680 = 0.1 group showed delayed nitrification, with NO2−–N accumulation reaching 1.39 mg/L on day 11 (Figure 2b). TP removal was fastest at an inoculum density of OD680 = 0.2, with a residual concentration of 0.12 mg L−1 on day 2, although all groups ultimately achieved removal efficiencies greater than 93%. COD removal was greatest at OD680 = 0.1, suggesting that higher inoculum densities may have caused intracellular release. With respect to aeration, higher aeration (4 L min−1) accelerated NH4+–N removal, reducing its concentration to 0.48 mg/L by day 2, whereas 1 and 2 L min−1 still retained 1.42 and 1.30 mg/L, respectively. NO2−–N remained low (0–0.15 mg/L) under low (1 L min−1) and high (4 L min−1) aeration, but in the 2 L min−1 group it gradually increased to 0.86 mg/L by day 11. NO3−–N consumption was slower at low aeration, while medium and high aeration (2 and 4 L min−1) enhanced nitrogen conversion, resulting in the highest TN removal efficiencies (88.02% and 89.03%). Phosphorus removal was similar across treatments (~0.05 mg/L), whereas COD removal was less effective at 1 and 4 L min−1, with residuals up to 12.33–14.50 mg/L and rebound likely linked to cell lysis or extracellular release [37].

Figure 2.

Variations in inorganic nitrogen, TN, TP and COD concentrations in the algae–bacteria symbiotic photobioreactor system under different initial inoculation densities and aeration rates. (a) Variations in NH4+–N concentration; (b) variations in NO2−–N concentration; (c) variations in NO3−–N concentration; (d) variations in TN concentration; (e) variations in TP concentration; (f) variations in COD concentration. “Time (d)” denotes the duration of reactor operation in days. The red line corresponds to the treatment with an initial inoculum density of OD680 = 0.2 and an aeration rate of 2 L min−1.

It should be noted that at higher aeration rates and under alkaline conditions (pH > 8), a fraction of total ammonia nitrogen may exist as free ammonia (NH3) gas, which can be stripped from the culture medium due to increased air flow and turbulence [38,39]. Although this physicochemical mechanism was not explicitly considered in the present analysis, it may have contributed partially to the observed reduction in NH4+–N, particularly in the 4 L min−1 group. Accordingly, future studies should incorporate quantitative evaluation of ammonia volatilization under varying pH and aeration conditions to better distinguish biological assimilation from physicochemical stripping effects.

3.1.2. Light Intensity and Photoperiods

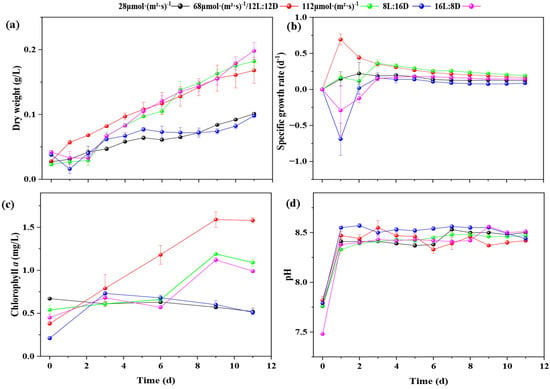

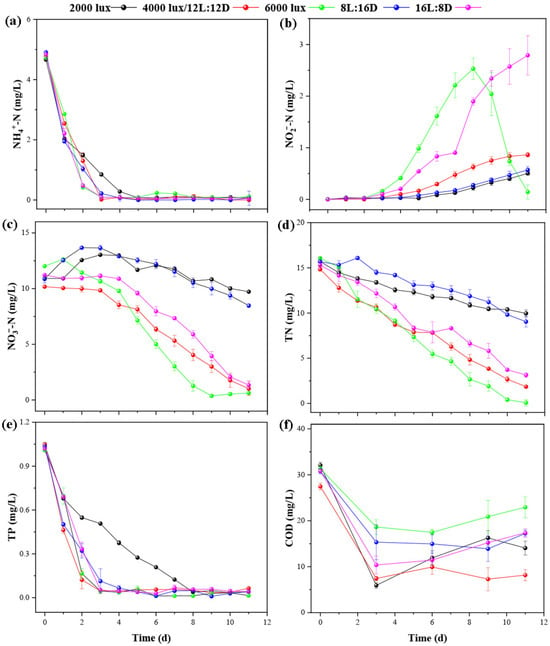

In the light intensity experiment, 112 μmol m−2 s−1 favored biomass accumulation, reaching a dry weight of 0.19 g/L on day 11, approximately 90% and 12% higher than the 28 μmol m−2 s−1 (0.10 g/L) and 68 μmol m−2 s−1 (0.17 g/L) treatments, respectively (Figure 3a). The specific growth rate peaked on day 3 in the high light intensity group (0.36 d−1) (Figure 3b), indicating a pronounced stimulatory effect of elevated light intensity during the mid-growth phase. In the photoperiod experiment, the longest light duration (16L:8D) yielded the highest biomass (0.20 g/L on day 11), 2.02- and 1.18-fold higher than the 8L:16D and 12L:12D treatments, respectively. Notably, the 12L:12D group exhibited the highest early-stage specific growth rate (0.69 d−1 on day 1), suggesting that a moderate light–dark cycle promotes growth initiation. Chlorophyll a content peaked under the 12L:12D photoperiod, reaching 1.58 mg/L on day 11 (Figure 3c), indicating that moderate light intensity combined with a balanced light–dark cycle favors pigment synthesis. pH increased steadily across all treatments, stabilizing between 8.40 and 8.50 (Figure 3d). Overall, high light intensity (112 μmol m−2 s−1) and extended illumination (16L:8D) promoted biomass accumulation, whereas moderate light (68 μmol m−2 s−1) with a regular light–dark cycle (12L:12D) enhanced pigment content and stabilized growth rates. These trends align with the typical microalgal response of boosting photosynthetic capacity under strong light while avoiding photoinhibition from continuous illumination [40,41].

Figure 3.

Temporal dynamics of biomass, specific growth rate, chlorophyll a, and pH in the algal–bacterial symbiotic system operated under varying light intensities and photoperiods. (a) Variations in dry weight; (b) variations in specific growth rate; (c) variations in chlorophyll a content; (d) variations in pH. “Time (d)” denotes the reactor operation period in days. The red line corresponds to the treatment condition with a light intensity of 68 μmol m−2 s−1 and a photoperiod of 12L:12D.

This study systematically examined the combined effects of light intensity and photoperiod on nutrient removal in an A. pyrenoidosa photobioreactor treating low C/N wastewater (Figure 4). Under 112 μmol m−2 s−1, TN removal was highest, reaching 0.90 mg/L on day 11, with NO3−–N fully consumed (0.63 mg/L); however, significant NO2−–N accumulation occurred, peaking at 2.53 mg/L on day 8, indicating that high light intensity may exacerbate nitrification imbalance. In contrast, 28 and 68 μmol m−2 s−1 treatments achieved rapid NH4+–N removal without notable NO2−–N accumulation, but final TN remained at 9.96 and 1.85 mg/L, respectively, suggesting that low to moderate light may limit coordinated nitrogen metabolism. In the photoperiod experiment, the 12L:12D treatment exhibited the most balanced denitrification, with lower NO2−–N accumulation (0.86 mg/L on day 11) and near-complete NH4+–N removal by day 3, highlighting that a moderate light–dark cycle stabilizes nitrification–denitrification. Although the 16L:8D group exhibited higher NO2−–N accumulation (2.79 mg L−1 on day 11), the TN and NO3−–N removal rates between the 16L:8D and 12L:12D groups showed no significant differences (p > 0.05). TP was effectively removed in all treatments, with concentrations below 0.07 mg/L by day 11, indicating that light conditions had minimal impact on phosphorus removal. However, during the initial phase (0–4 days), TP reduction was slower under the lower light intensity (28 μmol m−2 s−1) and milder operating conditions, which can be attributed to lower biomass accumulation and limited microbial activity at the early stage. Under these conditions, both algal and bacterial populations had not yet reached stable growth, leading to reduced phosphorus uptake through assimilation. As the cultures developed and photosynthetic activity increased, the algal–bacterial consortium became metabolically balanced, resulting in the accelerated TP removal observed in the later stage of operation. In contrast, COD removal varied more noticeably among treatments. All groups showed some COD rebound in the later stage; this effect was especially pronounced under 112 μmol m−2 s−1 and 16L:8D conditions, likely due to cell lysis and the release of dissolved organic matter under high light intensity or prolonged illumination.

Figure 4.

Variations in inorganic nitrogen, TN, TP and COD concentrations in the algae–bacteria symbiotic photobioreactor system under different light intensities and photoperiods. (a) Variations in NH4+–N concentration; (b) variations in NO2−–N concentration; (c) variations in NO3−–N concentration; (d) variations in TN concentration; (e) variations in TP concentration; (f) variations in COD concentration. “Time (d)” denotes the reactor operation period in days. The red line corresponds to the treatment condition with a light intensity of 68 μmol m−2 s−1 and a photoperiod of 12L:12D.

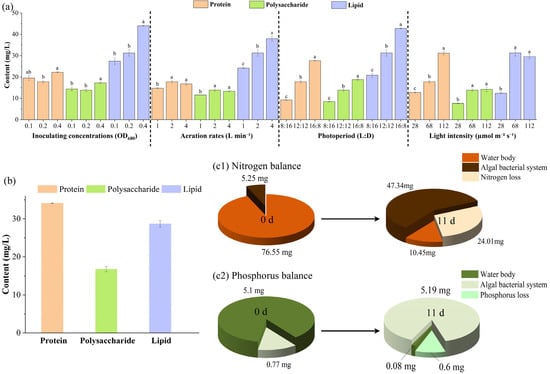

3.2. Chemical Compositions of Algal Biomass

This study systematically evaluated the effects of operational parameters on protein, polysaccharide, and total lipid production in an A. pyrenoidosa photobioreactor treating low C/N wastewater (Figure 5a). A higher initial inoculum (OD680 = 0.4) promoted total lipid accumulation, reaching 44.03 mg/L, while protein and polysaccharide yields were also highest at 22.23 mg/L and 17.24 mg/L, respectively, indicating that a higher biomass starting point favors energy-rich compound synthesis. Even at OD680 = 0.1, substantial biomass accumulation occurred, with protein and polysaccharide reaching 19.51 mg/L and 14.42 mg/L, slightly lower than the high-inoculum group. Aeration effects were more complex: total lipid production peaked at 4 L min−1 (37.98 mg/L), whereas protein and polysaccharide yields were higher at 2 L min−1 (17.77 mg/L and 13.83 mg/L), suggesting that moderate oxygen availability favors lipid synthesis, while protein and polysaccharide accumulation depends on a balanced metabolic state provided by intermediate aeration.

Figure 5.

Variations in protein, polysaccharide, and lipid contents, and nitrogen–phosphorus balance analysis in the algal–bacterial symbiotic system under single-factor and optimal operating conditions. (a) Changes in protein, polysaccharide, and lipid contents under different initial inoculum densities, aeration rates, and light conditions. (b) Temporal variations in active biomass content under optimal operating conditions. (c1) Nitrogenmass balance analysis under optimal operating conditions. (c2) phosphorus mass balance analysis under optimal operating conditions. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05).

Regarding light conditions, 112 μmol m−2 s−1 significantly enhanced protein synthesis, reaching 31.18 mg/L (p < 0.05), while total lipid and polysaccharide yields were also higher than those under moderate or low light, indicating that high light intensity promotes nitrogenous and energy-storage compound production. Extended illumination (16L:8D) will also significantly increased all target products, with protein, polysaccharide, and total lipid reaching 27.64 mg/L, 18.76 mg/L, and 42.79 mg/L, respectively, suggesting that longer light periods favor overall photosynthetic carbon fixation and energy metabolism. In contrast, low light (28 μmol m−2 s−1) and short photoperiods (8L:16D) markedly reduced the yields of all three compounds. These results indicate that higher light intensity and longer illumination enhance the accumulation of bioactive compounds in A. pyrenoidosa, likely by supplying sufficient energy to drive carbon flux and biosynthetic pathways [13], whereas inoculum density and aeration modulate product synthesis indirectly by affecting biomass accumulation and oxygen transfer efficiency, consistent with the metabolic characteristics of photoautotrophic microorganisms [22,37].

3.3. Performance of the A. pyrenoidosa Photobioreactor Under Optimal Operating Parameters

Considering both nitrogen and phosphorus removal as well as biomass production, the optimal operating conditions were identified as an initial inoculum of OD680 = 0.1, aeration rate of 2 L min−1, light intensity of 112 μmol m−2 s−1, and a photoperiod of 16L:8D. Under these conditions, the A. pyrenoidosa photobioreactor demonstrated outstanding nitrogen and phosphorus removal performance alongside efficient biomass production during low C/N wastewater treatment (Figure 5(c1,c2)). After 11 days of operation, TN and TP in the water phase decreased sharply, with TN dropping from 76.55 mg to 10.45 mg (86.35% removal) and TP from 5.10 mg to 0.08 mg (98.43% removal), demonstrating the system’s excellent nitrogen and phosphorus removal performance. At the same time, a clear mass balance was established between the aqueous and solid phases. Specifically, TN and TP accumulated within the algal–bacterial biomass increased from 5.25 mg to 47.34 mg (an accumulation of 42.09 mg) and from 0.77 mg to 5.19 mg (an accumulation of 4.42 mg), respectively. These increases in biomass-associated nitrogen and phosphorus closely matched the reductions observed in the aqueous phase, confirming that most of the removed nutrients were assimilated into the algal–bacterial biomass rather than lost through volatilization or precipitation. This consistency supports the overall process performance and validates the system’s nutrient removal efficiency through mass balance closure. Moreover, the strong correlation between nutrient removal and biomass accumulation highlights the superior inorganic nutrient fixation capacity of A. pyrenoidosa under optimized operating conditions. It should be noted that the optimized conditions for low C/N wastewater treatment provide a reliable and efficient strategy for resource recovery. Therefore, the simultaneous removal and conversion of nitrogen and phosphorus into algal–bacterial biomass demonstrate the system’s potential as a sustainable and integrated approach for the treatment and resource recovery of low C/N ratio wastewater.

Additionally, high light intensity (112 μmol m−2 s−1) and extended illumination (16L:8D) markedly enhanced photosynthetic efficiency and carbon–nitrogen flux, providing sufficient energy and carbon skeletons for protein, polysaccharide, and lipid synthesis. Moderate aeration (2 L min−1) maintained dissolved oxygen levels while avoiding excessive stripping of soluble nitrogen sources. A lower inoculum density (OD680 = 0.1) helped prolong the exponential growth phase, improving the conversion efficiency of nutrients into biomass. These findings are consistent with previous reports that microalgae enhance nutrient assimilation and biomass accumulation under high light intensity and extended illumination [13,42,43]. It should be noted that although the system’s performance under high C/N wastewater or other wastewater conditions requires further investigation, the results of the present study—particularly those obtained for low C/N wastewater—demonstrate the system’s strong potential for resource recovery and nutrient removal. These findings provide a solid foundation for future research to further evaluate and optimize the system’s applicability under diverse wastewater characteristics. They confirm that parameter optimization enables the simultaneous treatment of wastewater and production of high-value biomass, providing a reliable strategy for resource recovery from low C/N wastewater.

3.4. Metagenomic Analysis

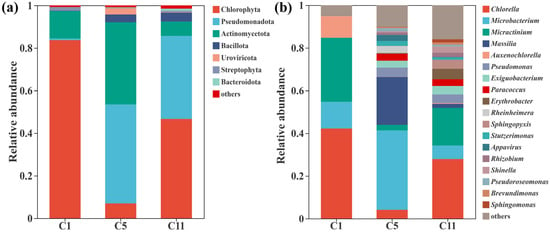

3.4.1. Microbial Community Structure Changes

Under the optimized operating conditions, the microbial community in the A. pyrenoidosa photobioreactor exhibited pronounced dynamics at the phylum level (Figure 6a). At the start of operation (C1), Chlorophyta overwhelmingly dominated (83.7%), indicating rapid niche occupation by the inoculated algae and active photosynthetic carbon fixation. By day 5 (C5), its relative abundance sharply decreased to 6.97%, while Pseudomonadota (46.5%) and Actinomycetota (38.6%) became predominant, suggesting a strong bacterial proliferation phase driven by the increasing availability of algal-released organic exudates. This transient bacterial dominance is a typical feature of early-stage algal–bacterial symbiosis, in which heterotrophic bacteria utilize photosynthate as carbon substrates while regenerating inorganic nitrogen and phosphorus for algal reuse [44]. The subsequent recovery of Chlorella by day 11 (C11)—with Chlorophyta abundance increasing to 46.7%—was closely linked to the optimized light and aeration conditions. The moderate light intensity (112 µmol m−2 s−1) and 16L:8D photoperiod ensured adequate photosynthetically active radiation without photoinhibition, maintaining effective carbon fixation and oxygen evolution. Simultaneously, the aeration rate of 2 L min−1 supplied sufficient CO2 and prevented oxygen oversaturation, thereby stabilizing pH and creating a favorable redox environment for both algae and aerobic bacteria (Pseudomonas, Sphingopyxis). This balanced gas exchange supported bacterial mineralization of organic compounds during the mid-phase, which in turn replenished dissolved inorganic nitrogen and phosphorus, facilitating Chlorella’s resurgence and biomass accumulation in the late phase. Notably, the moderate increase in Bacillota (4.2%) and the persistence of Uroviricota (0.19%) indicate the activation of spore-forming and viral populations, respectively, which are known to regulate microbial turnover and horizontal gene transfer in photobioreactor systems [45,46,47,48]. This observation aligns with recent findings that phage-driven lytic cycles and auxiliary metabolic gene transfer significantly enhance microbial adaptability in nutrient-limited environments [49,50].

Figure 6.

Microbial community composition at the (a) phylum level and (b) genus level across different operational stages.

At the genus level, community succession revealed distinct ecological shifts (Figure 6b). Initially, Chlorella (42.2%) and Micractinium (29.9%) dominated, consistent with the algal inoculum composition and early autotrophic growth. By day 5, green algal abundance dropped markedly (Chlorella to 4.1%), whereas bacterial genera such as Microbacterium (37.2%), Massilia (22.5%), and Pseudomonas (4.3%) proliferated, reflecting a transition toward bacterial dominance. These genera are known participants in organic matter degradation, nitrification, and heterotrophic denitrification, facilitating nitrogen turnover and maintaining nutrient availability under low C/N conditions [51,52,53]. By day 11, Chlorella recovered to 27.9% and Micractinium to 17.6%, accompanied by the persistence of denitrification-associated genera (Erythrobacter, Sphingopyxis, Paracoccus) at moderate abundance. These coexisting taxa indicate a stabilized metabolic partnership wherein oxygenic photosynthesis by algae sustained aerobic nitrogen oxidation, while bacterial mineralization and denitrification regenerated nutrients for continued algal assimilation. The observed rebound of Chlorella thus reflects the establishment of a cooperative steady state driven by light–aeration–nutrient coupling.

The microbial succession therefore represents a transition from an algae-dominated startup phase to a bacterial proliferation phase and finally to a balanced, mutually reinforcing consortium. The optimized physical parameters fostered a finely tuned exchange of oxygen, dissolved organic carbon, and nitrogen species between algae and bacteria, enabling sustained nutrient removal and biomass production. Such parameter-driven ecological stabilization underscores the feasibility of steering microbial community structure and function through controlled environmental conditions, thereby achieving efficient nutrient recovery and enhanced photobioreactor performance under low C/N constraints.

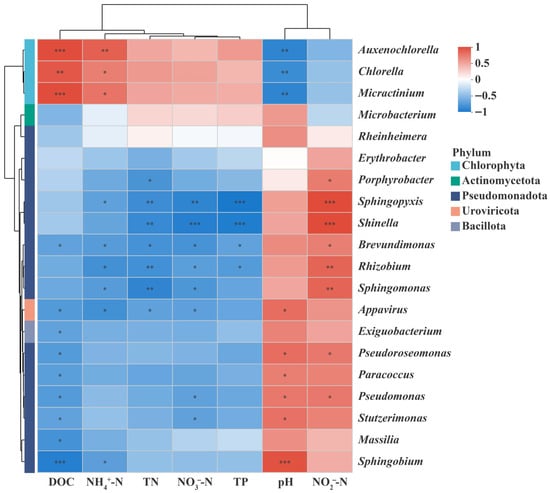

3.4.2. Correlation Analysis of Environmental Factors and Nitrogen–Phosphorus Metabolism

- (1)

- Correlation between microbe communities and environmental factors

Under optimal operating conditions, microbial community structure showed significant correlations with water-quality parameters (Figure 7), reflecting coordinated metabolic interactions in the algae–bacteria system treating low C/N wastewater. Chlorella and Micractinium were significantly negatively correlated with pH (r = –0.83, p < 0.01; r = −0.88, p < 0.01) and positively correlated with dissolved organic carbon (DOC) (r = 0.88, p < 0.01; r = 0.93, p < 0.001), indicates active photosynthetic CO2 uptake and the concurrent release of organic exudates, which elevate pH and DOC, consistent with algae-driven autotrophic metabolism. Both genera were also correlated positively with NH4+–N (r = 0.68, p < 0.05; r = 0.73, p < 0.05), supporting their strong NH4+–N assimilation capacity that contributes directly to protein synthesis and nitrogen removal.

Figure 7.

Heatmap of correlations between environmental factors and microbial community. Red boxes represent the positive correlations, while blue boxes represent the negative correlations. Significance codes are represented by asterisks: ‘***’ for p < 0.001, ‘**’ for p < 0.01, ‘*’ for p < 0.05.

Several bacterial genera exhibited linkages to nitrogen transformations. Pseudomonas, Rhizobium, Sphingomonas, Brevundimonas, and Stutzerimonas were negatively correlated with NO3−–N, suggesting active denitrification. Notably, the relative abundance of Sphingopyxis increased 3.7-fold from phase C1 to C11, coinciding with a 78% decline in NO3−–N and 87% reduction in TN, demonstrating its quantitative contribution to nitrate and total-nitrogen removal. Similarly, Shinella abundance rose in parallel with TP removal (97.6%), consistent with its reported polyphosphate-accumulating function. Furthermore, pH correlated positively (r > 0.67, p < 0.05) with denitrification-related genera such as Pseudomonas and Paracoccus, indicating that slightly alkaline conditions favored bacterial nitrogen metabolism. Algae fix inorganic carbon and assimilate NH4+–N through photosynthesis to promote biomass accumulation, while bacteria remove nitrogen and phosphorus to improve water quality, together achieving both wastewater treatment and resource recovery [21,25]. These relationships substantiate a cooperative division of labor: photosynthetic algae fix inorganic carbon and assimilate NH4+–N, while heterotrophic bacteria mediate complementary nitrate reduction and phosphorus uptake, jointly enhancing effluent quality.

- (2)

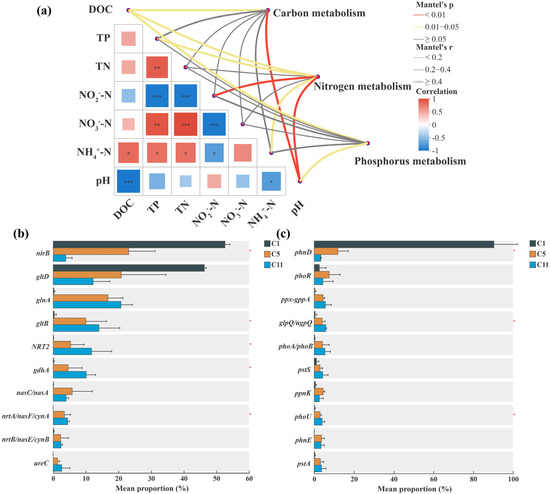

- Mechanistic analysis of nitrogen and phosphorus metabolism

Mantel tests confirmed significant correlations between functional pathways and environmental variables (Figure 8a). Nitrogen metabolism correlated positively with pH (r = 0.527, p = 0.004), NH4+–N (r = 0.493, p = 0.024), NO2−–N (r = 0.573, p = 0.002), TP (r = 0.456, p = 0.026), and DOC (r = 0.651, p = 0.011), highlighting the importance of carbon availability and alkalinity in promoting nitrification–assimilation coupling. Phosphorus and carbon metabolism were also significantly correlated with pH (r = 0.537, p = 0.015; r = 0.541, p = 0.008) and DOC (r = 0.504, p = 0.018; r = 0.466, p = 0.024), suggesting that pH and organic carbon availability in the photobioreactor can enhance microbial P and C metabolism by regulating microbial activity. These results highlight the critical role of pH and nutrient availability (NH4+–N, DOC) in shaping microbial C–N–P metabolic processes.

Figure 8.

Metagenomic analysis of algae-bacteria symbiotic system for treatment of low C/N ratio wastewater. (a) Correlation analysis of environmental factors and carbon-nitrogen-phosphorus metabolism and relative abundances of the top 10 key functional genes involved in (b) nitrogen and (c) phosphorus transformation based on metagenomic analysis in algae-bacteria symbiotic system. ‘***’ for p < 0.001, ‘**’ for p < 0.01, ‘*’ for p < 0.05.

Metagenomic data revealed a temporal shift in nitrogen-transformation dominance (Figure 8b). During the initial phase (C1), denitrification-related nirB accounted for 52.61% of nitrogen genes, whereas by phase C11 its abundance declined to 3.87%. In contrast, assimilatory genes glnA and gltB increased from 0.24% → 20.75% and 0.35% → 13.99%, respectively. The elevated expression of glnA (glutamine synthetase) and gltB (glutamate synthase) directly aligns with the observed 97.60% NH4+–N and 87.0% TN removal, confirming that algal assimilation became the dominant nitrogen-removal mechanism. Meanwhile, denitrification genes (narG, nirK, norB) remained below 2.50% abundance in C11, indicating minor bacterial denitrification. The co-occurrence of Pseudomonas and Sphingopyxis with low-level denitrification genes suggests their auxiliary role in reducing residual nitrate and maintaining redox balance, complementing algal nitrogen uptake. This metabolic shift underscores that under optimized light and aeration conditions, algal assimilation became the dominant nitrogen removal pathway [54], closely linked to the biomass synthesis requirements of photosynthetic microorganisms such as Chlorella and Micractinium.

Phosphorus-metabolism genes displayed a parallel functional transition (Figure 8c). In the initial phase, the key organic phosphorus mineralization gene phnD was highly dominant (90.35%), indicating that organic phosphorus decomposition was the primary mechanism of phosphorus mobilization. As operation progressed, its abundance decreased sharply (to 3.34% in C11), while several genes related to inorganic phosphorus uptake and transport were significantly upregulated. These included the high-affinity phosphate transport system genes pstS (increasing from 1.13% to 4.25%), pstA (0.29% to 3.71%), and pstC (0.33% to 1.92%), as well as the alkaline phosphatase gene phoA (0.25% to 5.40%) and the polyphosphate kinase gene ppk1 (0.26% to 2.80%). These shifts suggest a transition in metabolic emphasis from organic phosphorus degradation to active inorganic phosphorus uptake and intracellular storage [5], correlating with the consistently high removal efficiency of TP (97.6%) observed in water quality data. The enrichment of Shinella and Sphingopyxis—known polyphosphate-accumulating bacteria—provides a direct microbial explanation for these macroscopic results. Furthermore, increased abundances of glpQ (0.48% to 5.83%) and ppx (0.31% to 5.63%) indicated enhanced recycling capacity of organic phosphorus substrates under phosphorus-limited conditions. This metabolic strategy shift—from decomposition to absorption, and from inorganic transport to intracellular storage—reflects the efficient phosphorus utilization by the algal-bacterial system in a low-carbon-nitrogen-ratio wastewater environment and provides a molecular basis for phosphorus accumulation in microalgal biomass [55].

Together, these quantitative linkages between microbial composition, functional-gene abundance, and nutrient-removal data substantiate the synergistic role of algal–bacterial consortia: algae supplied organic carbon and oxygen, sustaining heterotrophic denitrifiers and phosphorus-accumulating bacteria, while bacterial mineralization regenerated inorganic nutrients for algal assimilation. This mutualistic exchange maintained high NH4+–N, TN, and TP removal and stabilized reactor performance under low-C/N conditions. The coordinated succession of nitrogen- and phosphorus-metabolism genes thus provides a molecular basis for the observed improvements in water quality and biomass productivity.

4. Conclusions

This study elucidated how operational parameter optimization governs the metabolic balance and functional dynamics of an Auxenochlorella pyrenoidosa-based photobioreactor treating low C/N wastewater. Inoculum density, aeration rate, light intensity, and photoperiod each exerted distinct but interdependent effects on algal growth, nutrient removal, and system stability. Among these, the combination of an initial OD680 of 0.1, aeration rate of 2 L min−1, light intensity of 112 μmol m−2 s−1, and a 16L:8D photoperiod achieved the best balance between efficient nutrient removal and sustainable biomass production. Metagenomic and water-quality analyses together revealed that optimized physical parameters did not merely improve reactor performance but actively redirected nitrogen metabolism—from bacterial denitrification toward algal nitrogen assimilation—by reshaping the algal–bacterial community and metabolic gene expression (notably glnA, gltB). This metabolic transition underpins the system’s high nitrogen removal efficiency and carbon utilization under limited organic-C conditions. These findings provide a broader conceptual insight: controlling operational parameters can strategically modulate microbial community function, allowing the co-optimization of wastewater treatment and biomass valorization in a single process. This demonstrates the feasibility of regulating microbial metabolism through engineering design, enabling carbon-efficient, resource-recovering wastewater treatment systems. Future research should integrate metabolomic and kinetic modeling approaches to further quantify carbon–nitrogen fluxes and evaluate the downstream valorization potential of the produced biomass in biorefinery applications.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Data analysis and visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Funding acquisition, L.Z.; Investigation, Data analysis and visualization, Y.X.; Investigation, T.T.; Investigation, Y.Z.; Investigation, G.H.; Supervision, Writing—review & editing, J.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32401412), Opening Foundation of Shenzhen Collaborative Innovation Public Service Platform for Marine Algae Industry (SQ202403), Key Project of Natural Science Research for Higher Education Institutions of Anhui Province (2024AH051458), Fuyang Normal University 2023 Doctoral Research Launch Fund (2023KYQD0025) to Lin Zhao.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, J. Application of multi-electron donor autotrophic denitrification (MEDAD) substrate in constructed wetlands for treating low carbon-to-nitrogen ratio wastewater: A feasible framework. Ecol. Eng. 2025, 217, 107648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Zhai, X.; Hu, M.; Chang, J.S.; Lee, D.J. Atypical removals of nitrogen and phosphorus with biochar-pyrite vertical flow constructed wetlands treating wastewater at low C/N ratio. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 422, 132219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sátiro, J.; dos Santos Neto, A.; Tavares, J.; Marinho, I.; Magnus, B.; Kato, M.; Albuquerque, A.; Florencio, L. Impact of inoculum on domestic wastewater treatment in high-rate ponds in pilot-scale: Assessment of organic matter and nutrients removal, biomass growth, and content. Algal Res. 2025, 86, 103923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Qin, L.; Feng, P.; Shang, C.; Wang, Z.; Yuan, Z. Treatment of low C/N ratio wastewater and biomass production using co-culture of Chlorella vulgaris and activated sludge in a batch photobioreactor. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 274, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, L.; Bi, R.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, Z. One-step bioremediation of hypersaline and nutrient-rich food industry process water with a domestic microbial community containing diatom Halamphora coffeaeformis. Water Res. 2024, 254, 121430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusuma, H.S.; Illiyanasafa, N.; Jaya, D.E.C.; Darmokoesoemo, H.; Putra, N.R. Utilization of the microalga Chlorella vulgaris for mercury bioremediation from wastewater and biomass production. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2024, 37, 101346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo, L.A.; Thorarinsdottir, R.I.; Bjornsson, S.; Palsson, O.P.; Skulason, H.; Johannsson, S.; Brynjolfsson, S. Remediation of Aquaculture Wastewater Using the Microalga Chlorella sorokiniana. Water 2020, 12, 3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayatollahi, S.Z.; Esmaeilzadeh, F.; Mowla, D. Integrated CO2 capture, nutrients removal and biodiesel production using Chlorella vulgaris. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 104763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sátiro, J.; Marchiori, L.; Morais, M.V.; Marinho, T.; Florencio, L.; Gomes, A.; Muñoz, R.; Albuquerque, A.; Simões, R. Integrating photobioreactors and constructed wetlands for paper pulp industry wastewater treatment: A nature-based system approach. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 71, 107237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Yang, H.L.; Li, C.; Peng, Y.Y.; Lu, M.M.; Jin, W.H.; Bao, J.J.; Guo, Y.M. Effect of organic carbon to nitrogen ratio in wastewater on growth, nutrient uptake and lipid accumulation of a mixotrophic microalgae Chlorella sp. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 282, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Hernandez, M.M.; Krebss-Kleingezinds, E.; Parra-Saldivar, R.; Alfaro-Ponce, M.; Chairez, I.; Melchor Martinez, E.M.; Kjellberg, K.; Soheil Mansouri, S. Bioprocessing sidestream valorization as culture stream for Chlorella vulgaris biomass accumulation: Neural data-driven design of experiments. Biofuels 2025, 16, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.; Li, X.; Li, P.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, H.; Yang, X.; Chen, S.; Zhou, M.; Wang, S.; et al. Enhanced treatment of low C/N domestic wastewater in a membrane photobioreactor: Operational control of microalgal-bacterial symbiosis for synergistic pollutant and antibiotic resistance genes removal. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 394, 127398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Chu, G.; Gao, C.; Tian, T.; Zhang, W.; Chen, W.; Gao, M. Effect of light intensity on performance, microbial community and metabolic pathway of algal-bacterial symbiosis in sequencing batch biofilm reactor treating mariculture wastewater. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 433, 132726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikaran, Z.; Suárez-Alvarez, S.; Urreta, I.; Castañón, S. The effect of nitrogen limitation on the physiology and metabolism of Chlorella vulgaris var L3. Algal Res. 2015, 10, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.F.; Chu, F.F.; Lam, P.K.; Zeng, R.J. Biosynthesis of high yield fatty acids from Chlorella vulgaris NIES-227 under nitrogen starvation stress during heterotrophic cultivation. Water Res. 2015, 81, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Li, J.; Xing, C.; Yuan, H.; Yang, J. Characterization of Auxenochlorella protothecoides acyltransferases and potential of their protein interactions to promote the enrichment of oleic acid. Biotechnol Biofuels Bioprod 2023, 16, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wei, H.; Mao, X.; Liu, J. Proteomics Analysis of Lipid Droplets from the Oleaginous Alga Chromochloris zofingiensis Reveals Novel Proteins for Lipid Metabolism. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2019, 17, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Lyu, X.; Zhu, Z.; Wu, C.; Xu, Z.; Li, W.; Liu, N.; Du, C.; et al. Phycospheric Bacteria Alleviate the Stress of Erythromycin on Auxenochlorella pyrenoidosa by Regulating Nitrogen Metabolism. Plants 2025, 14, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Jia, J.; Hu, H.; Li, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, C. Nitrogen and phosphorus limitations promoted bacterial nitrate metabolism and propagation of antibiotic resistome in the phycosphere of Auxenochlorella pyrenoidosa. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 468, 133786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, Y.; Sheng, Q.; Zhao, J.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, R. Effects of Intracellular Polysaccharides and Proteins of Auxenochlorella pyrenoidosa on Water Quality, Floc Formation, and Microbial Composition in a Biofloc System. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Xiaojuan, H.; Qin, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Chen, M.; Liao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, X. Optimizing nutrient removal of algal-bacterial symbiosis system for treating low C/N farmland drainage. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 306, 109149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.; Gao, K.; Qian, P.; Dong, J.; Gao, Z.; Liu, Q.; Chen, B.; Deng, X. Cultivation of Chlorella sorokiniana in a bubble-column bioreactor coupled with cooking cocoon wastewater treatment: Effects of initial cell density and aeration rate. Water Sci. Technol. 2021, 83, 2615–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Cheng, S.; Zhang, Y.; Teng, J.; Zhang, M.; Lin, H. Optimizing aeration intensity to enhance self-flocculation in algal-bacterial symbiosis systems. Chemosphere 2023, 341, 140064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, C.C.; Zuo, W.; Tian, Y.; Sun, N.; Wang, Z.W.; Zhang, J. Effect of aeration rate on performance and stability of algal-bacterial symbiosis system to treat domestic wastewater in sequencing batch reactors. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 222, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, C.C.; Tian, Y.; Liang, H.; Zuo, W.; Wang, Z.W.; Zhang, J.; He, Z.W. Enhanced nitrogen and phosphorus removal from domestic wastewater via algae-assisted sequencing batch biofilm reactor. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 250, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Huang, G.; Hu, Z.; Wu, C.; Tang, J. Performance and mechanisms of an algae-bacteria symbiotic system for treating low carbon-to-nitrogen ratio wastewater. Biochem. Eng. J. 2026, 226, 109995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Environmental Protection Administration of China. The Monitoring and Analysis Methods of Water and Wastewater (4th Version); China Environmental Science Press: Beijing, China, 2002; pp. 210–213. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey, S.W.; Humphrey, G.F. New spectrophotometric equations for determining chlorophylls a, b, c1 and c2 in higher plants, algae and natural phytoplankton. Biochem. Physiol. Pflanz. 1975, 167, 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.; Najafpour, G.D.; Mohammadi, M.; Seifi, M.H. Cultivation of newly isolated microalgae Coelastrum sp. in wastewater for simultaneous CO2 fixation, lipid production and wastewater treatment. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2018, 41, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhuang, J.; Ni, S.; Luo, H.; Zheng, K.; Li, X.; Lan, C.; Zhao, D.; Bai, Y.; Jia, B.; et al. Overexpressing CrePAPS Polyadenylate Activity Enhances Protein Translation and Accumulation in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben--Amotz, A.; Tornabene, T.G.; Thomas, W.H. Chemical profile of selected species of microalgae with emphasis on lipids. J. Phycol. 1985, 21, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.-Y.; Gao, K.; Zhang, R.-C.; Addy, M.; Lu, Q.; Ren, H.-Y.; Chen, P.; Liu, Y.-H.; Ruan, R. Growing Chlorella vulgaris on thermophilic anaerobic digestion swine manure for nutrient removal and biomass production. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 243, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohutskyi, P.; Kligerman, D.; Byers, N.; Nasr, L.; Cua, C.; Chow, S.; Su, C.; Tang, Y.; Betenbaugh, M.; Bouwer, E. Effects of inoculum size, light intensity, and dose of anaerobic digestion centrate on growth and productivity of Chlorella and Scenedesmus microalgae and their poly-culture in primary and secondary wastewater. Algal Res. 2016, 19, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kryvenda, A.; Tischner, R.; Steudel, B.; Griehl, C.; Armon, R.; Friedl, T. Testing for terrestrial and freshwater microalgae productivity under elevated CO2 conditions and nutrient limitation. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsenpour, S.F.; Willoughby, N. Effect of CO2 aeration on cultivation of microalgae in luminescent photobioreactors. Biomass Bioenergy 2016, 85, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Gao, K. Effects of CO2 concentrations on the freshwater microalgae, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, Chlorella pyrenoidosa and Scenedesmus obliquus (Chlorophyta). J. Appl. Phycol. 2003, 15, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Tang, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Song, Z.; Fu, G.; Hu, Z. A vertical-flow constructed wetland–microalgal membrane photobioreactor integrated system for treating high-pollution-load marine aquaculture wastewater: A lab-scale study. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 919, 170465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.-B.; Ma, J.; Zeb, I.; Yu, L.; Chen, S.; Zheng, Y.-M.; Frear, C. Ammonia recovery from anaerobic digester effluent through direct aeration. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 279, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guštin, S.; Marinšek-Logar, R. Effect of pH, temperature and air flow rate on the continuous ammonia stripping of the anaerobic digestion effluent. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2011, 89, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Guo, L.; Gao, M.; Zhao, Y.; Jin, C.; She, Z. Regulation of carbon source metabolism in mixotrophic microalgae cultivation in response to light intensity variation. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 302 Pt B, 114095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardo, F.M.; Khoo, K.S.; Ahmad Sobri, M.Z.; Suparmaniam, U.; Ethiraj, B.; Anwar, A.F.; Lam, S.M.; Sin, J.C.; Shahid, M.K.; Ansar, S.; et al. Modelling photoperiod in enhancing hydrogen production from Chlorella vulgaris sp. while bioremediating ammonium and organic pollutants in municipal wastewater. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 346, 123648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iasimone, F.; Panico, A.; De Felice, V.; Fantasma, F.; Iorizzi, M.; Pirozzi, F. Effect of light intensity and nutrients supply on microalgae cultivated in urban wastewater: Biomass production, lipids accumulation and settleability characteristics. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 223, 1078–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, A.; Bhatnagar, P.; Gautam, P.; Bisht, B.; Nanda, M.; Kumar, S.; Vlaskin, M.S.; Kumar, V. Enhancing the bio-prospective of microalgae by different light systems and photoperiods. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2023, 22, 2687–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ji, B.; Tian, J.; Liu, Y. Development, performance and microbial community analysis of a continuous-flow microalgal-bacterial biofilm photoreactor for municipal wastewater treatment. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 338, 117770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yan, X.; Qin, T.; Gan, Y.; Li, N.; Zheng, C. Applicability of blue algae as an activator for microbial enhanced coal bed methane technologies. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 123063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Li, H.; Duan, C.S.; Zhou, X.Y.; An, X.L.; Zhu, Y.G.; Su, J.Q. Metagenomic and viromic analysis reveal the anthropogenic impacts on the plasmid and phage borne transferable resistome in soil. Environ. Int. 2022, 170, 107595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Cao, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, W.; Sun, Y.; Li, Q.; Mi, J.; Deng, L.; Liao, X.; Feng, Y.; et al. Early life dynamics of ARG and MGE associated with intestinal virome in neonatal piglets. Vet. Microbiol. 2022, 274, 109575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Tang, A.; Jin, T.; Sun, D.; Guo, F.; Lei, H.; Lin, L.; Shu, W.; Yu, P.; Li, X.; et al. A panoramic view of the virosphere in three wastewater treatment plants by integrating viral-like particle-concentrated and traditional non-concentrated metagenomic approaches. Imeta 2024, 3, e188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X.; Yang, S.; Radosevich, M.; Wang, Y.; Duan, N.; Jia, Y. Bacteriophage-driven microbial phenotypic heterogeneity: Ecological and biogeochemical importance. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2025, 11, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassen, B.; Hammami, S. Environmental phages: Ecosystem dynamics, biotechnological applications and their limits, and future directions. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2025, 136, lxaf136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Thiri, M.; Wang, H. Simultaneous heterotrophic nitrification and aerobic denitrification by a novel isolated Pseudomonas mendocina X49. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 319, 124198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Peng, Q.; Jiang, R.; Yang, N.; Xing, C.; Wang, R. Mn-oxidizing microalgae and woodchip-denitrifying bioreactor system for recovering manganese and removing nitrogen from electrolytic manganese metal industrial tailwater. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 488, 137383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Yang, Z.; Jia, X.; Cabrera, J.; Ji, M. Bio-capture of Cr(VI) in a denitrification system: Electron competition, long-term performance, and microbial community evolution. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 432, 128697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Xu, Y.; Liang, C.; Peng, L.; Zhou, Y. Nitrogen removal by algal-bacterial consortium during mainstream wastewater treatment: Transformation mechanisms and potential N2O mitigation. Water Res. 2023, 235, 119890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, W.; Wang, S.; Jin, Y.; Wu, Z.; Liu, D.; Su, H. Insights into nitrogen and phosphorus metabolic mechanisms of algal-bacterial aerobic granular sludge via metagenomics: Performance, microbial community and functional genes. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 369, 128442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).