Abstract

This study presents a practical early-warning approach for heavy rainfall detection using the temporal dynamics of satellite-derived Cloud-Top Temperature (CTT). A rapid rise followed by a sharp fall in CTT is identified as a precursor signal of convective intensification. By quantifying the pattern and the -to- amplitude (), a window—representing a potential heavy-rainfall candidate period—is defined. The observed lead time between the onset of CTT decline and the subsequent radar-observed rainfall surge is calculated, while an estimated lead time is inferred from the steepness of CTT fall in the absence of a surge. Application to eight heavy rainfall events in Korea (July 2025) yielded a probability of detection (POD) of 87.5%, indicating that potential heavy rainfall could be detected approximately 1.3–8.6 h in advance. Compared with radar-based nowcasting, the CTT method retained predictive skill up to 3 h before numerical model guidance became effective, suggesting that satellite-based signals can bridge the forecast gap in short-term prediction. This work demonstrates a clear methodological novelty by introducing a physical interpretable, pattern-based metric. Quantitatively, the method improves early-warning capability by providing 1–3 h of additional lead time relative to radar nowcasting in rapidly evolving convective environments. Overall, this framework provides an interpretable, low-cost module suitable for operational early-warning systems and flood preparedness applications.

1. Introduction

Early warning of heavy rainfall is a crucial task in reducing social and economic damage. While weather radar systems are capable of directly detecting ongoing precipitation phenomena, they often fall short in identifying the precursor signals that appear just before the rapid intensification of convection leading to a heavy rainfall event. For this reason, satellite information is required as a complementary observation source that can capture those early convective developments. Among various satellite-derived variables, Cloud-Top Temperature (CTT) is strongly correlated with upper-cloud cooling processes and with the formation and collapse of convective cloud tops. The temporal rate of change in CTT—whether an increase or a decrease—as well as the total amplitude of variation, can serve as leading indicators of imminent rainfall surges [1,2].

Research on early detection of heavy rainfall and the forecasting of convective development has evolved continuously over the past several decades [3,4]. The earliest studies began with the so-called “ingredients-based approach”, which sought to understand precipitation initiation as the combined outcome of several key physical ingredients. Doswell, Brooks, and Maddox [5] represented this line of research by systematically diagnosing the three fundamental components—moisture, instability, and lifting motion—and integrating them to propose a structured methodology for flash flood forecasting. However, although effective as a conceptual framework, such an approach proved difficult to apply in operational forecasting because it did not allow for real-time tracking of the rapidly varying signals associated with actual cloud development. Subsequent research efforts therefore began to focus on the use of geostationary satellite infrared (IR) channels, which provide measurements of brightness temperature by detecting the longwave infrared radiation emitted from cloud tops. From these observations, CTT can be inferred and continuously monitored as a proxy for convection growth [1,2,6,7]. Mecikalski and Bedka [8] introduced a method for detecting the timing of convective initiation by analyzing trends in 10.7 µm brightness temperature. Bedka et al. [9] further advanced this concept by developing an objective method for automatically detecting overshooting tops (OTs) based on spatial gradients in satellite IR imagery, thereby enabling real-time identification of strong convective peaks. However, most of these studies focused on North America and mid-latitude regions [10,11,12], and they did not establish a clear quantitative temporal correspondence between satellite-based variables such as CTT and ground-observed rainfall intensification captured by radar. In other words, they were successful in identifying convection, but they did not explicitly measure how much earlier the satellite signal appears before the rainfall actually intensifies.

In a related context, Fritsch and Carbone [13] emphasized the need to improve the predictability of warm-season precipitation and pointed out the systematic “warm-season bias” problem of numerical weather prediction (NWP) models. They argued that improving precipitation forecasts requires the integration of dynamical, physics-based numerical models such as those representing convection, radiation, microphysics, and boundary-layer processes with real-world observational data—especially satellite and radar data—so that the rapidly changing signals of cloud physics and convection initiation can be properly represented. Despite continuous advancements, the fundamental limitation of NWP models persists, primarily due to their structural inability to resolve the fast-evolving microphysical processes (e.g., heterogeneous freezing, ice growth) that occur at the very beginning of intense convective growth [14]. Therefore, observational approaches remain essential for very short-term (nowcasting) high-impact weather warnings.

More recently, research on satellite–radar fusion for early detection of convection has become active [6,15,16,17]. Mecikalski et al. [17] and Jewett et al. [16] estimated the probability of convective initiation by combining satellite-observed CTT cooling rates with radar reflectivity patterns, while Marion et al. [18] attempted to distinguish storms with a high potential for extreme precipitation by integrating the area of overshooting tops with vertical cloud-structure information. Jewett et al. [16] represented that satellite-based detection of the transition from CTT cooling to convective growth can considerably enhance the early identification of convective initiation, leading to an approximate 50% reduction in false alarms. However, their framework remains primarily concerned with detecting satellite-derived convection signals that emerge prior to radar-identified convective initiation, without establishing any linkage between satellite-based convective development and the subsequent intensification or evolution of precipitation. Although these approaches represent important advances, most of them rely on complex detection algorithms or machine-learning-based probabilistic models, making them less transparent and harder to interpret for operational forecasters. In contrast, Houze et al. [19] in Cloud Dynamics theoretically described the thermodynamic linkage between upper-cloud cooling (i.e., CTT decrease) and rainfall intensification, providing a firm physical basis for using satellite CTT as an early indicator of convective development. Following this, Lee et al. [20] and Lee et al. [21] demonstrated that, using Himawari-8 AMI data, convection monitoring can be automated through a relatively simple threshold-based CTT fluctuation detection approach. However, even such simplified methods did not quantitatively specify the lead time between the satellite signal and the actual onset of radar-observed rainfall surges, leaving a crucial gap in practical application.

The recent advances have investigated the satellite microphysics predictability for an early-stage forecast [2]. Their assessment presented nowcasting capacity of using remote sensing cloud-top temperature and cloud effective radius evolution, reporting 93% with lead time of up to 6 h. Though results, the generalization of such findings is constrained by limitations to previous extreme rainfall studies that heavily rely on long-term reanalysis products such as ERA5 datasets. These studies primarily analyze post-event datasets collected after the occurrence of rainfall events, thereby offering understanding phenomenon rather than real-time prediction, which inherently limits their applicability to operational early warning systems. These approaches provide insights into the general behavior of convective systems but cannot resolve the rapid cloud-top transitions that precede severe rainfall events. Consequently, existing methods offer limited operational utility, particularly within the forecast gap between the decay of radar-based nowcasting skill and the effective lead time of NWP models.

Despite these advances, an important gap remains unaddressed in the literature. Most prior studies, whether grounded in dynamical reasoning or satellite-based detection of convective signatures, have primarily offered conceptual or qualitative indicators of potential heavy rainfall. They describe the physical plausibility of convective intensification such as strong updrafts, cloud-top cooling, or overshooting-top development but do not provide explicit, reproducible thresholds that allow forecasters to determine, in real time, whether a convective system will actually evolve into a heavy-rainfall event. Consequently, existing approaches remain interpretive and lack the operational clarity needed for decision-making under time-critical forecasting environments.

In contrast, the present study introduces a set of four statistically derived diagnostic criteria such as CTT rise, fall, swing, and rainfall-threshold conditions that function as explicit and objective decision rules for identifying imminent heavy rainfall. These empirically validated thresholds quantify the temporal evolution of cloud-top temperature and its relationship with radar-observed rainfall surges, enabling clear discrimination between mere convective development and true heavy-rainfall intensification. This represents a major advance over prior research, providing the first simple, operational, and threshold-based framework that can be directly applied to real-time early-warning systems.

2. Method and Input Data

2.1. Terminology and Symbols

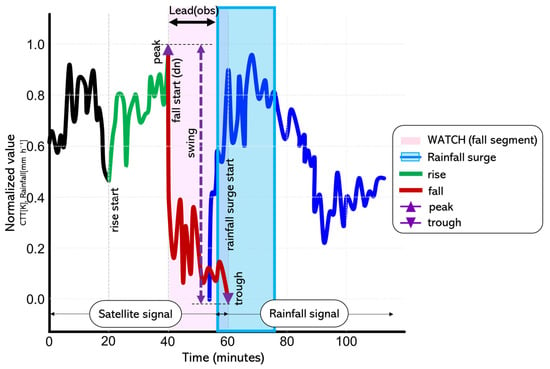

This section defines the principal terms and variables used in the operational framework for heavy-rainfall early warning proposed in this study. Figure 1 illustrates a schematic example of a preprocessed CTT time series, showing how the key pattern that precedes heavy rainfall is extracted from satellite-observed CTT variations. The green bold segment represents the stage, during which CTT continuously increases with a positive slope. The local maximum marking the end of this warming period is denoted as the . Immediately afterward, the time series enters the stage, depicted as a red bold segment with a pronounced negative slope, culminating at a local minimum called the . The difference between the and defines the amplitude. When the , , and simultaneously satisfy their respective thresholds, a window is activated from the onset of the () to the (). Blue hollow rectangles superimposed on the figure represent radar-observed rainfall surge periods, and the horizontal arrow between and the onset of the surge indicates the observed lead time . This conceptual behavior forms the basis of the definition and its interpretation in terms of pre-event detection.

Figure 1.

Concept of the CTT- method. Black line: synthetic preprocessed CTT signal; green thick segment: ; red thick segment: ; purple △/▽: and ; purple double arrow (↕): amplitude ( → ); pink shaded band: window [, ]; blue hollow rectangle: radar surge period; black top arrow (↔): observed lead time from the start of the () to the radar-surge onset.

2.2. Data Preprocessing and Selection

This study makes use of satellite and radar data obtained from the Geo-KOMPSAT-2A (GK-2A) geostationary meteorological satellite and the Hybrid Surface Rainfall (HSR) product of the Korea Meteorological Administration (KMA). The input datasets consist of two types of time-series variables: (i) satellite-derived parameters, including CTT and IWP, and (ii) radar-derived rainfall intensity. Table 1 summarizes the data sources and their spatial and temporal resolutions.

Table 1.

Satellite and radar data sources and variables used in this study.

The satellite data were obtained from the Advanced Meteorological Imager (AMI) onboard GK-2A, operated by the National Meteorological Satellite Center (NMSC) of KMA. CTT represents the brightness temperature at the cloud top and is used to track upper-cloud cooling and convective development. IWP provides column-integrated ice content and serves as a supplementary variable for interpreting the rainfall surge signal.

For both satellite and radar variables, preprocessing is applied to focus on convective-scale variability. A moving-average is first used to reduce high-frequency noise and linear trend removal or normalization to the [0, 1] range is performed to remove slow background tendencies and harmonize the amplitude of different variables. After preprocessing, the resulting time series and represent detrended, scaled residuals suitable for threshold-based analysis across multiple events.

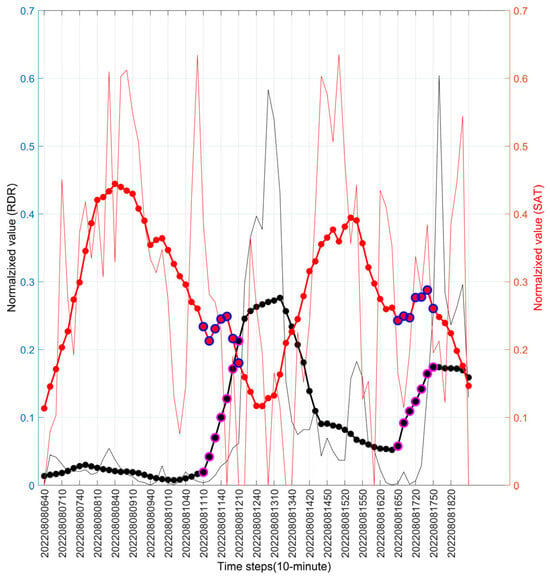

Before developing the criteria, the relationships between radar-observed rainfall intensity (RDR) and satellite-derived variables were examined. Figure 2 shows an example from a heavy rainfall event over Seoul on 8 August 2022, where the raw and smoothed IWP series are compared with radar rainfall.

Figure 2.

Relationship between RDR and satellite IWP for the Seoul area on 8 August 2022. The thin red line denotes IWP, the thin black line denotes radar rainfall, and the bold red and bold black lines represent their respective two-hour moving averages. The figure indicates that, despite amplitude differences, the two variables exhibit a consistent inverse tendency during active rainfall period.

Figure 3 presents a time-series comparison between RDR and CTT for a major heavy rainfall event in Seoul (3 August 2020). The CTT exhibits a robust inverse relationship with radar-estimated rainfall, reflecting the temperature dependency of precipitation processes. Time-series analysis conducted during periods of significant rainfall intensity consistently reveals that decreases in CTT systematically coincide with increases in rainfall intensity. When the inverted CTT series (blue line) is plotted alongside rainfall, a positive correlated behavior emerges. Notably, the increase in the inverted CTT series appears earlier than the corresponding increase in radar-estimated rainfall, indicating that decreases in the original CTT precede and contribute to the intensification of rainfall.

Figure 3.

Relationship between RDR and satellite CTT for heavy rainfall event in Seoul on 3 August 2020. Thin red line: CTT; thin black line: RDR; bold red/black lines: two-hour moving averages; blue line: CTT inverted around its mean trend for visualization.

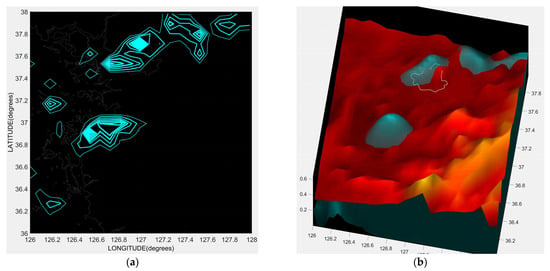

In addition to temporal variation, the spatial distribution of CTT provides valuable intuitive information about the evolution of rainfall systems. Figure 4 contrasts a map displaying only radar rainfall with a map in which the same rainfall field is overlaid on the corresponding CTT distribution. While the rainfall-only map reveals the current precipitation intensity, the combined CTT–rainfall map shows that low-CTT regions effectively bound the rainfall area, acting as an envelope that indicates where convection is most vigorous and where rainfall is likely to expand or propagate.

Figure 4.

Comparison between (a) radar rainfall only and (b) radar rainfall overlaid on CTT for the heavy rainfall event on 8 August 2022. The CTT field provides a physical and visual background that enhances the intuitive understanding of rainfall distribution, confinement, and movement. (a) Spatial Distribution of RDR. (b) RDR Distribution overlaid on CTT Background.

2.3. Definition of Characteristic CTT Variables for Detecting Heavy Rain-Fall Precursors

To detect precursor signals of heavy rainfall from satellite-derived CTT time series, several characteristic variables are defined: , , , , , , window, and lead time (). Together they constitute the essential components of the algorithm, transforming the temporal behavior of CTT into a set of physically interpretable parameters.

The of the CTT series represents the rate of change in CTT and is approximated by finite differences between adjacent observations. Negative values indicate cooling and reflect enhanced updrafts and deep convection. Based on the smoothed slope, four phases are identified: , , , and . The phase is defined as the interval during which the smoothed exceeds a minimum threshold () for a sustained duration, indicating persistent warming of the cloud top. The is the local maximum at the end of the . The phase begins when the smoothed drops below a negative threshold () and persists for the required duration, marking rapid cloud-top cooling associated with strong updrafts. The is the local minimum at the end of the .

The is defined as the temperature difference between the and the , . It quantifies the amplitude of the – transition and serves as a diagnostic measure of convective strength. Larger values indicate more vigorous thermodynamic transitions and are closely associated with the probability of a subsequent rainfall surge.

When the , , and all satisfy their respective thresholds, the interval from the onset of the () to the () is designated as a window. This interval represents a potential pre-warning period during which convective development is actively intensifying. The observed lead time, , is defined as the time difference between and the onset of the first radar-observed rainfall surge that exceeds a prescribed intensity threshold and duration. Positive values correspond to successful early detection; negative values indicate that rainfall intensification had already begun before activation.

2.4. Components and Implementation of the Method

The method is an operationally applicable procedure that issues an early warning when the CTT time series exhibits a specific sequence of rapid followed by sharp . When a distinct – transition with sufficient swing amplitude is detected, the system declares a candidate pre-rainfall event and evaluates its timing against radar-observed surges.

Table 2 provides a compact glossary of the main variables, parameters, and decision criteria used in the framework. The estimation is based on discrete differences with respect to time, smoothed over a specified window to suppress high-frequency noise. Detection of , , , and follows a sequential rule-based procedure: sustained positive slope above defines the ; the following local maximum is the ; sustained negative slope below defines the ; and the first local minimum defines the . Edge conditions are handled by using the final sample as a proxy when necessary.

Table 2.

Compact glossary of variables and decision criteria used in the framework.

Once the and segments are identified, the amplitude is computed and compared with a minimum threshold (). If , , and conditions are all satisfied, a window [, ] is activated. Radar rainfall surges are then identified as intervals in which exceeds for at least a minimum duration. For each window, the first subsequent radar surge onset is used to calculate . When no such surge occurs, may be inferred from the magnitude of the most negative during the interval.

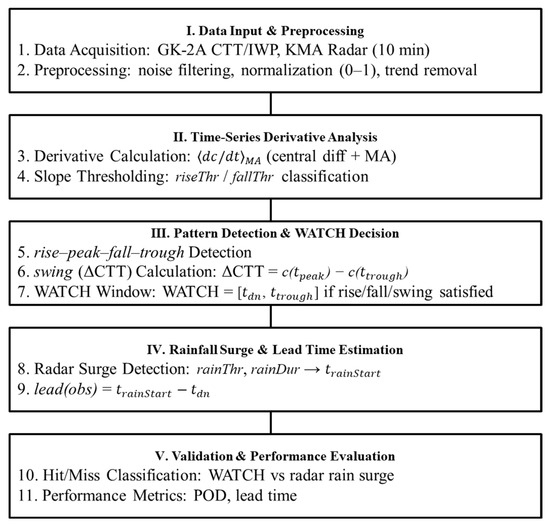

Figure 5 summarizes the overall implementation procedure as a flowchart, from initial data preprocessing and slope computation to phase detection, activation, and lead-time calculation. The algorithm is modular, transparent, and computationally lightweight, enabling both retrospective batch processing and real-time streaming applications.

Figure 5.

Flowchart of the CTT analysis procedure, showing the sequential steps of preprocessing, computation, phase detection (–––), activation, and lead-time calculation.

2.5. Determination of WATCH Thresholds and Estimation of Lead Time

To ensure that detections are both physically meaningful and operationally stable, specific quantitative thresholds are applied to the , , and variables. A window is activated only when all three conditions are satisfied simultaneously: (i) existence of a phase with sustained positive above , (ii) existence of a phase with sustained negative below , and (iii) amplitude exceeding . These conditions correspond to the three fundamental physical signatures of pre-rainfall convective intensification—growth, cooling, and amplitude.

Automatic thresholds for , , and are determined adaptively from each event’s characteristics using percentile-based rules. In general form, and are defined using positive and negative percentiles of the distribution, while the threshold is given by . The percentile-based approach minimizes the influence of outliers and ensures robustness against noise, whereas the dual constraint in combines an absolute minimum amplitude (0.12) with a relative fraction of the total variability.

Once a window is declared, the connection to lead time is established by searching for the first radar surge that occurs after . The observed lead time is defined as . Positive values indicate that the signal successfully anticipates rainfall intensification; negative values denote delayed detection. When no radar surge is found within a defined temporal horizon, an estimated lead time can still be derived from the steepness of the CTT fall using the magnitude of the minimum , , as a proxy for convective acceleration. This dual use of observed and estimated lead times enhances the operational flexibility of the framework, allowing it to provide useful guidance even in situations where radar data are incomplete or delayed.

3. Results

This section presents the performance of the model and compares its predictive characteristics with those of radar-based nowcasting. The analysis focuses on eight major heavy-rainfall episodes that occurred over the throughout South Korea during 16–20 July 2025.

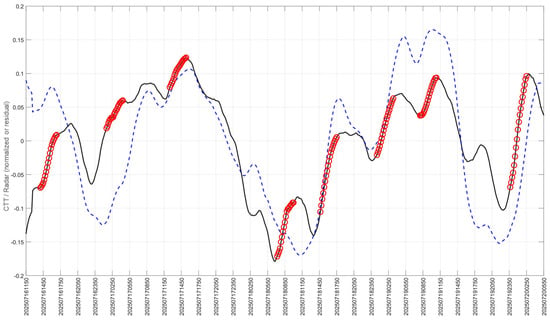

First, the predictive skill of radar-based short-term forecasts (RDR nowcasts) was evaluated. Correlation coefficients between observed radar rainfall and nowcasted fields were computed for multiple lead-time intervals. Across seven evaluation periods, the average correlation decreased rapidly with increasing lead time, dropping to approximately 0.17 at the 180 min horizon. This confirms the well-known limitation of extrapolation-based nowcasting methods, which lose skill beyond about three hours. In contrast, the partial correlation between CTT and observed radar rainfall remained high, with a mean value of about 0.95 for similar lead-time ranges (Table 3, Figure 6). This indicates that CTT retains statistically significant predictive information well beyond the effective range of radar nowcasts.

Table 3.

Comparison of correlation coefficients between observed rainfall, CTT, and RDR nowcasts for different lead-time intervals.

Figure 6.

Comparison of observed RDR rainfall and inverse CTT variations with respect to observed rainfall surge periods. The black solid line denotes the RDR rainfall time series, the red circles indicate the identified rainfall-surge periods, and the blue dashed line represents the inverse CTT variations.

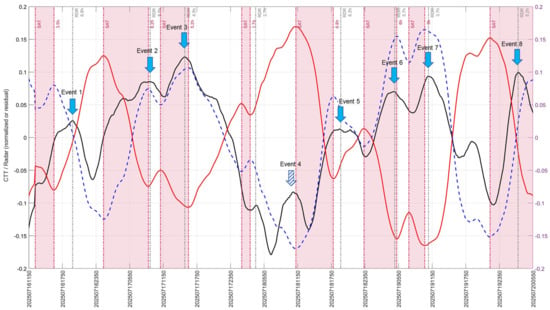

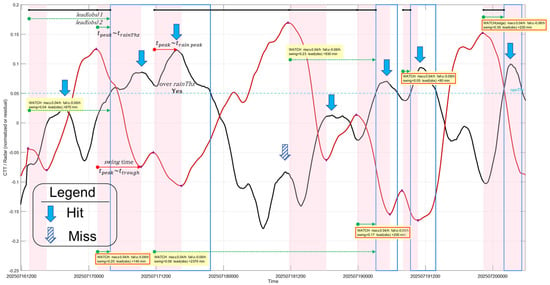

The detection performance was then evaluated using a fixed set of model parameters (Table 4). Verification was conducted over eight selected time intervals corresponding to distinct rainfall-peak episodes (Table 5). The model successfully detected seven out of eight episodes, corresponding to a Probability of Detection (POD) of 87.5%. In addition to event-based verification, continuous lead-time analysis was performed, demonstrating that signals consistently preceded radar-observed rainfall surges, with lead times ranging from 1.3 to 8.6 h depending on the model configuration. Partial correlations between CTT and observed rainfall were computed for all lead times, confirming the statistical significance of the signals. In examining individual events, the undetected case (Event 4) corresponded to the weakest rainfall episode among the eight events analyzed. This episode exhibited limited convective development and did not produce a sufficiently pronounced CTT rise–peak–fall structure for the criteria to be activated. Although some increase in rainfall was observed, its magnitude did not reach the threshold of a heavy-rain event, resulting in weak convective signatures. This outcome indicates that the approach is optimally suited for detecting well-organized deep convection leading to substantial rainfall, whereas its sensitivity to marginal or low-intensity precipitation events is inherently lower. From an operational standpoint, this characteristic is acceptable—and even desirable—because the method is primarily intended for early identification of high-impact heavy-rainfall events, where false alarms for minor precipitation should be minimized.

Table 4.

Main parameter settings used for the model applied to the 16–20 July 2025 heavy rainfall events.

Table 5.

Summary of lead times derived from model applications across eight rainfall-peak intervals.

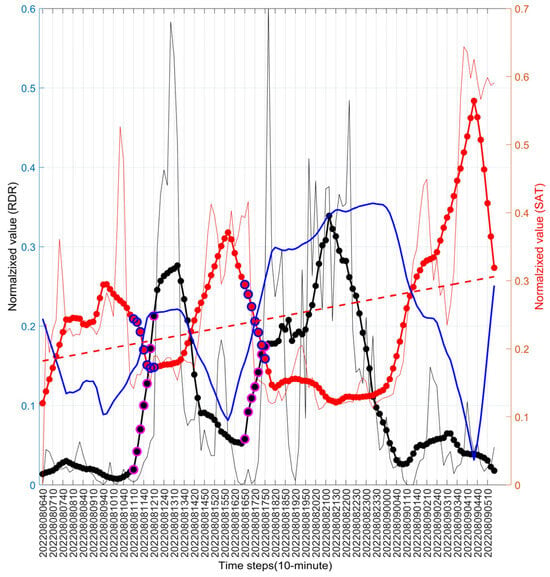

Two complementary configurations were examined. Model A relies solely on CTT-based criteria (, , ) and therefore detects events regardless of rainfall intensity. Model B adds a rainfall condition requiring that radar intensity exceeds a defined threshold () after activation. Under Model A, the lead times from to ( duration) and from to the rainfall peak ranged from approximately 3.0 to 8.6 h. Under Model B, which applied the additional rainfall threshold, detections were obtained for five events (2, 3, 6, 7, and 8), with shorter but more conservative lead times of about 1.3–3.6 h (Figure 7 and Figure 8). Thus, Model A provides broader, longer early-detection capability, whereas Model B offers more stringent but operationally robust warnings, suitable for issuing official alerts where false alarms must be minimized.

Figure 7.

Observed minimum lead times from CTT swing intervals to rainfall peaks for eight heavy rainfall events. The black solid line represents the RDR rainfall, the red solid line indicates the CTT time series, and the blue dashed line denotes the inverse CTT variations. Pink shaded regions denote CTT intervals that satisfy the conditions (). The hollow dotted black box indicates the period from the onset of the satisfying the WATCH conditions to the rainfall peak ().

Figure 8.

Observed lead times () from activation to rainfall-threshold exceedance (blue hollow boxes) for the same eight events. The black solid line represents the RDR rainfall, the red solid line indicates the CTT time series. Pink shaded areas correspond to rapid CTT decreases coinciding with radar-observed rainfall intensification. detections under the rainfall-threshold condition provide shorter but more reliable lead times.

Taken together, these results show that the CTT method can detect heavy rainfall precursors with lead times between approximately 1.3 and 8.6 h, depending on the configuration and the strength of the CTT signal. The combination of high POD and strong CTT–rainfall correlations indicates that WATCH is operationally practical. The comprehensive calibration and verification procedures applied here ensure that the method is rigorously evaluated and robust for operational use, providing confidence for its integration into real-time flood-warning and disaster-response systems.

4. Discussion

Results of this study suggest the intriguing CTT transitions for predicting short term heavy rainfalls. The gradual pattern that was reliably found before precipitation strengthening emphasizes the link between upper-tropospheric cloud development and the mesoscale convective growth modulating processes. The observed association of the rapid cooling stage with trailing radar-observed rain rate increases indicates that satellite infrared observations contain dynamic precursors with the potential for providing lead times that are longer than those that can be achieved through conventional nowcasting methods.

The interpretations of these CTT shifts align well with established theories on convective development. The cooling stage might signify the beginning of deep, active updrafts that transport hydrometers into the upper troposphere [2]. The strong partial correlations of CTT fall rates with radar-derived rainfall trends that persist at lead times of more than three hours show that signals based on CTT do capture at least some facets of mesoscale organization and latent-heating mechanisms that on the radar side become harder to detect with increasing forecast horizon. These findings further support that the CTT dynamics are physically based precursors and not statistical noise.

The correlation between satellite-retrieved cloud-top dynamics and following rain-rate surges is consistent with recent multimodal nowcasting reports that demonstrate that satellite information helps in predictions especially at longer lead times where radar-only methods degenerate. For example, Kassoumeh et al. [22] demonstrated that integrating satellite imagery with radar observations substantially improves the monitoring of heavy-rainfall patterns, yielding higher predictive skill and extending lead times to approximately 5–30 min relative to radar-only approaches. This result is consistent with our findings and further suggests that satellite-derived cloud-top evolution encapsulates thermodynamic precursors that remain robust across differing spatial and temporal resolutions as well as varying model architectures. Although multimodal deep-learning systems may implicitly capture these relationships, the WATCH framework offers a physically interpretable basis for understanding how satellite signals contribute to early convective detection. This coherence between empirical machine-learning outcomes and physically based satellite diagnostics reinforces both the generality and the robustness of the proposed framework.

Relative to previous satellite-based convective detection approaches, the WATCH suite introduces two methodological advancements. First, prior studies have primarily focused on cloud segmentation or broad assessments of convective potential [8,16], whereas explicitly quantifies the temporal offset between CTT variations and subsequent rainfall intensification. This temporal metric provides a direct and operationally meaningful measure of lead time. Second, in contrast to complex multivariate or machine-learning models that often function as opaque systems [3,7], WATCH relies on simple and physically grounded proxies directly linked to CTT dynamics. This reduces concerns regarding algorithmic opacity and extensive training-data requirements, thereby enhancing the practicality of WATCH, particularly in data-constrained or resource-limited environments.

The variability in WATCH lead time is largely governed by the rate at which CTT decreases during the convective-intensification stage. Rapid, steep CTT declines reflect the presence of vigorous and rapidly deepening updrafts that are typically associated with the development of heavy-rainfall systems, consistent with the findings of Nizar et al. [2]. Although such intense updrafts may temporarily delay the growth of cloud-droplet effective radius above the level of warm-rain initiation because the fast ascent provides limited time for condensational growth, the overall rapid intensification still shortens the temporal gap between the onset of cloud-top cooling and the occurrence of maximum surface rainfall. In contrast, slow CTT cooling characterizes gradually organizing convective systems and leads to longer operationally useful lead times. Because the CTT cooling rate directly governs the pace of precipitation development, the absolute magnitude of the negative CTT slope provides a physically interpretable indicator of both the acceleration of convective organization and the strength of the underlying updraft, thereby determining the effective warning time.

Although these findings are encouraging, the following observational and methodological limitations should be noted. CTT is cloud-top radiance temperature and is limited by the cloud optical depth, which means that it cannot be used to identify microphysical processes or latent heating in the deeper parts of a convective core [2]. Due to this WATCH may fail to detect elements of evolving storms from the inside. In addition, the employment of IWP as an ancillary information is restricted to daytime conditions, since it is derived from solar reflected channels, which may cause diurnal asymmetry of accessible information. The framework is responsive to observation errors as well: the measurements of cloud-top temperature (CTT) derived from satellite are subject radiometric, geometric and cloud phase uncertainties, and the estimation of precipitation by radar is affected by attenuation, beam blockage and bright band contaminations. These inaccuracies affect the timing and magnitude of the sequences.

To enhance operational reliability, future work should address these constraints by evaluating the diurnal sensitivity of the framework, incorporating nighttime-capable sensors, and developing adaptive thresholding schemes. In addition, formal error propagation analyses, multi-year validation datasets, region-independent or adaptive thresholds, and the integration of storm-motion vectors and multi-sensor variables would reduce uncertainty. Finally, broader validation encompassing diverse convective environments is required to compute robust quantitative skill metrics.

5. Conclusions

This study proposed and validated the CTT method, a physically interpretable and operationally efficient approach for the early detection of heavy rainfall based on the temporal dynamics of CTT observed by the GK-2A geostationary satellite. By identifying a characteristic ––– pattern and applying three simple yet physically grounded thresholds (, , ), the method detects precursor signals associated with upper-cloud cooling and convective intensification prior to the onset of heavy precipitation.

Evaluation across eight consecutive heavy-rainfall events in South Korea in July 2025 demonstrated that the model successfully detected seven events in advance, achieving a probability of detection of 87.5% with lead times ranging from 1.3 to 8.6 h. These results underscore the model’s capability to anticipate rainfall intensification prior to radar-based observations, thus extending the operational lead time for early-warning systems.

The analysis further revealed that the predictive skill of the method persisted after radar-based nowcasting lost correlation with observed precipitation, suggesting that satellite-derived CTT signals can effectively bridge the temporal gap between the decline of radar extrapolation skill and the onset of reliable numerical weather prediction outputs.

From an operational perspective, the simplicity and transparency of the thresholds render the method computationally efficient and readily interpretable, facilitating integration into automated multi-sensor platforms combining satellite thermal infrared, microwave, radar reflectivity, and ground-based hydrological measurements. Moreover, the framework can be enhanced through regional calibration, uncertainty quantification, and adaptive thresholding via machine learning, providing flexibility for diverse climatological contexts.

Nevertheless, this study is subject to certain limitations. The evaluation was restricted to eight events within a single season and geographic region, and the thresholds were empirically defined, potentially limiting generalizability under different climatic conditions. Future research should aim to validate the method across multiple seasons and regions, assess threshold sensitivity, and quantify associated uncertainties to ensure robustness and operational reliability.

In conclusion, the CTT method represents a significant advancement in early-warning systems for heavy rainfall, offering a scientifically grounded, operationally feasible approach that can support real-time flood and disaster-response management.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Data curation, formal analysis, methodology, and original draft writing were performed by H.P., J.S.Y. and N.K. Writing—review and editing were performed by S.H. Resources and research supervision were conducted by S.H. Research supervision, funding acquisition, and writing—review and editing were performed by S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Korea Planning & Evaluation Institute of Industrial Technology, funded by the Ministry of the Interior and Safety (MOIS), Republic of Korea, under the project “Development and Application of Advanced Technologies for Urban Runoff Storage Capability to Reduce Urban Flood Damage” (RS-2024-00415937).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the findings of this study are publicly available through the Korea Meteorological Administration’s API Hub (https://apihub.kma.go.kr/, accessed on 10 November 2025). All satellite and meteorological data used in the analysis can be obtained via the API services offered on this platform.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

List of Abbreviations

| AMI | Advanced Meteorological Imager |

| CTT | Cloud-Top Temperature |

| GK-2A | Geo-KOMPSAT-2A |

| HSR | Hybrid Surface Rainfall |

| IWP | Ice Water Path |

| KMA | the Korea Meteorological Administration |

| NWP | numerical weather prediction |

| OTs | Overshooting Tops |

| POD | Probability of Detection |

| RDR | Radar-observed rainfall intensity |

References

- Shukla, B.P.; Kishtawal, C.M.; Pal, P.K. Satellite-based nowcasting of extreme rainfall events over Western Himalayan region. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2017, 10, 1681–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizar, S.; Thomas, J.; Jainet, P.J.; Sudheer, K.P. A novel technique for nowcasting extreme rainfall events using early microphysical signatures of cloud development. PLoS Clim. 2025, 4, e0000497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Han, W.; Sun, H.; Lin, N.; Song, X.; Yang, Y.; Tian, J.; Liu, Y.; Wen, J.-R.; Zhang, X.; et al. Nowcast3D: Reliable precipitation nowcasting via gray-box learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2511.04659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starzec, M.; Mullendore, G.L.; Kucera, P.A. Using radar reflectivity to evaluate the vertical structure of forecast convection. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2018, 57, 2835–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doswell, C.A., III; Brooks, H.E.; Maddox, R.A. Flash flood forecasting: An ingredients-based methodology. Weather Forecast. 1996, 11, 560–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamarianakis, Y.; Feidas, H.; Kokolatos, G.; Chrysoulakis, N.; Karatzias, V. Evaluating remotely sensed rainfall estimates using nonlinear mixed models and geographically weighted regression. Environ. Model. Softw. 2008, 23, 1438–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Chen, S.; Chen, H. Estimating tropical cyclone intensity via deep learning and storm morphology recognition from satellite imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 4111113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecikalski, J.R.; Bedka, K.M. Forecasting convective initiation by monitoring 10.7 μm brightness temperature trends. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2006, 45, 435–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedka, K.; Brunner, J.; Dworak, R.; Feltz, W.; Otkin, J.; Greenwald, T. Objective satellite-based detection of overshooting tops using infrared window channel brightness temperature gradients. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2010, 49, 181–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedka, K.M. Overshooting cloud top detections using MSG SEVIRI infrared brightness temperatures and their relationship to severe weather over Europe. Atmos. Res. 2011, 99, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworak, R.; Bedka, K.; Brunner, J.; Feltz, W. Comparison between GOES-12 overshooting-top detections, WSR-88D radar reflectivity, and severe storm reports. Weather Forecast. 2012, 27, 684–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikuš, P.; Strelec Mahović, N. Satellite-based overshooting top detection methods and an analysis of correlated weather conditions. Atmos. Res. 2013, 123, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsch, J.M.; Carbone, R.E. Improving quantitative precipitation forecasts in the warm season: A USWRP research and development strategy. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2004, 85, 955–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Ma, L.; Hu, T.; Zhang, R. Impacts of microphysical parameterizations on banded convective system in convection-permitting simulation: A case study. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1149518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortelli, A.; Scafetta, N.; Mazzarella, A. Nowcasting and real-time monitoring of heavy rainfall events inducing flash-floods: An application to Phlegraean area (Central-Southern Italy). Nat. Hazards 2019, 97, 861–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewett, C.P.; Mecikalski, J.R. Adjusting thresholds of satellite-based convective initiation interest fields based on the cloud environment. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2013, 118, 12649–12660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecikalski, J.R.; MacKenzie, W.M.; König, M.; Müller, S. Cloud-top properties of growing cumulus prior to convective initiation as measured by Meteosat Second Generation. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2010, 49, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marion, G.R.; Trapp, R.J.; Nesbitt, S.W. Using overshooting top area to discriminate potential for large, intense tornadoes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019, 46, 12520–12526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houze, R.A. Cloud Dynamics, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Han, H.; Im, J.; Jang, E.; Lee, M.-I. Detection of deterministic and probabilistic convection initiation using Himawari-8 Advanced Himawari Imager data. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2017, 10, 1859–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Kummerow, C.D.; Zupanski, M. A simplified method for the detection of convection using high-resolution imagery from GOES-16. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2021, 14, 3755–3771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassoumeh, R.; Rügamer, D.; Oppel, H. Enhancing heavy rain nowcasting with multimodal data: Integrating radar and satellite observations. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2511.00716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).