Mesozooplankton Community Structure and Indicator Species in Relation to Seasonal Hydrography in the Yellow Sea and Northern East China Sea

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Surveys

2.2. Sample Analysis

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Hydrography and Water Masses

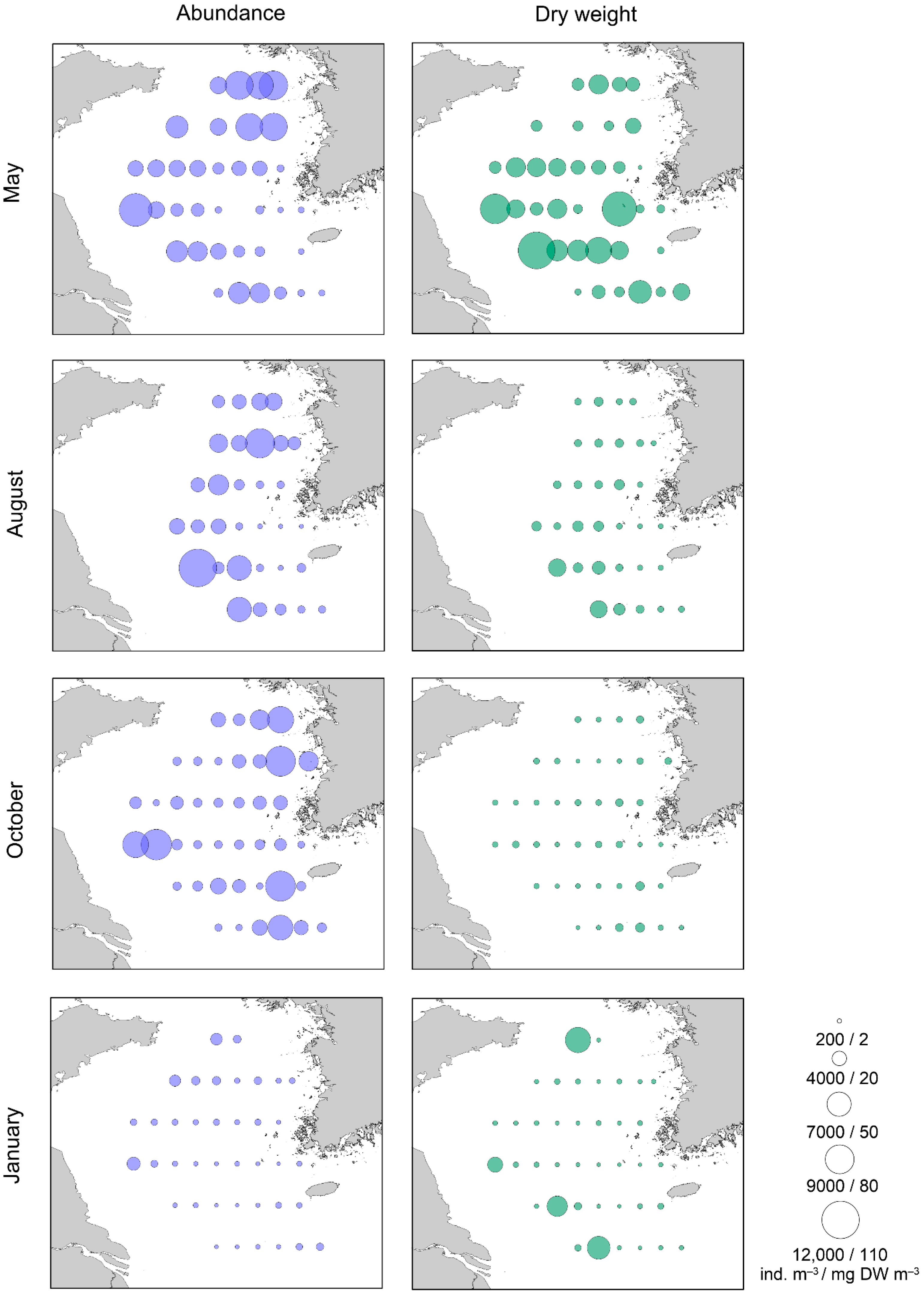

3.2. Mesozooplankton Abundance and Dry Weight

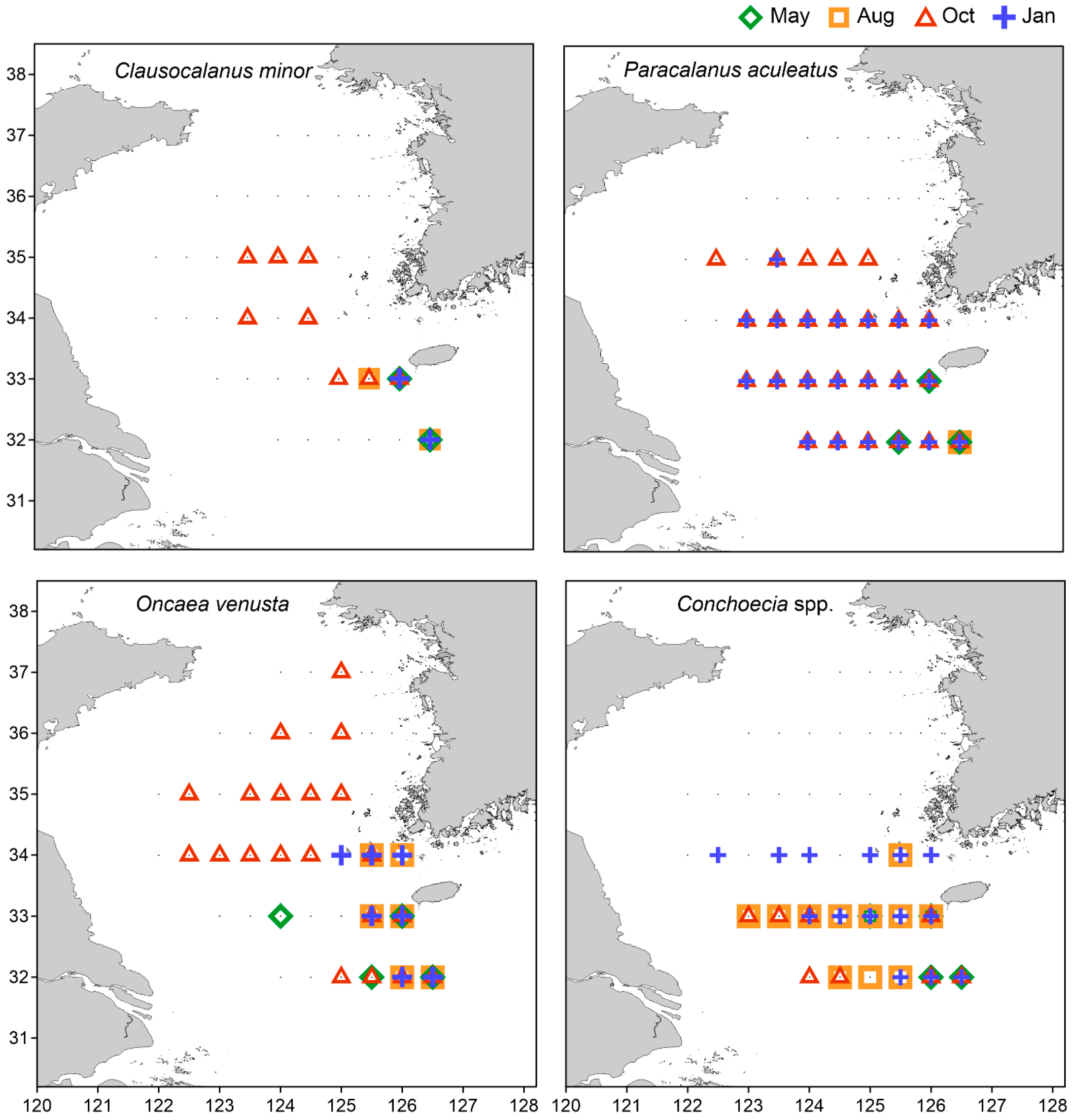

3.3. Dominant Species and Environmental Associations

3.4. Mesozooplankton Community Clusters and Indicator Species

4. Discussion

4.1. Environmental Drivers of Community Variability

4.2. Influence of Frontal Systems on Coastal Communities

4.3. Indicator Species of the YSBCW

4.4. Influence of Warm Currents near Jeju Island

4.5. Limitations for Interpreting Regional Variability

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Steinberg, D.K.; Landry, M.R. Zooplankton and the ocean carbon cycle. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2017, 9, 413–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaugrand, G.; Reid, P.C.; Ibanez, F.; Lindley, J.A.; Edwards, M. Reorganization of North Atlantic marine copepod biodiversity and climate. Science 2002, 296, 1692–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepin, P.; Johnson, C.L.; Harvey, M.; Casault, B.; Chassé, J.; Colbourne, E.B.; Galbraith, P.S.; Hebert, D.; Lazin, G.; Maillet, G.; et al. A multivariate evaluation of environmental effects on zooplankton community structure in the western North Atlantic. Prog. Oceanogr. 2015, 134, 197–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodama, T.; Wagawa, T.; Iguchi, N.; Takada, Y.; Takahashi, T.; Fukudome, K.I.; Morimoto, H.; Goto, T. Spatial variations in zooplankton community structure along the Japanese coastline in the Japan Sea: Influence of the coastal current. Ocean Sci. 2018, 14, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, S.R.; Bresnan, E.; Cook, K.; Eerkes-Medrano, D.; Machairopoulou, M.; Mayor, D.J.; Rabe, B.; Wright, P. Environmental drivers of a decline in a coastal zooplankton community. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2022, 79, 844–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastauer, S.; Ohman, M.D. Resolving abrupt frontal gradients in zooplankton community composition and marine snow fields with an autonomous Zooglider. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2024, 70, S102–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaugrand, G.; Reid, P.C. Long-term changes in phytoplankton, zooplankton and salmon related to climate. Glob. Change Biol. 2003, 9, 801–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiørboe, T. How zooplankton feed: Mechanisms, traits and trade-offs. Biol. Rev. 2011, 86, 311–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daewel, U.; Hjøllo, S.S.; Huret, M.; Ji, R.; Maar, M.; Niiranen, S.; Travers-Trolet, M.; Peck, M.A.; van de Wolfshaar, K.E. Predation control of zooplankton dynamics: A review of observations and models. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2014, 71, 254–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, A.J. In hot water: Zooplankton and climate change. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2008, 65, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, S.; Batten, S.D.; Martin, C.S.; Ivory, S.; Miloslavich, P.; Weatherdon, L.V. Zooplankton monitoring to contribute towards addressing global biodiversity conservation challenges. J. Plankton Res. 2018, 40, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichikawa, H.; Beardsley, R.C. The current system in the Yellow and East China Seas. J. Oceanogr. 2002, 58, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isobe, A. Recent advances in ocean-circulation research on the Yellow Sea and East China Sea shelves. J. Oceanogr. 2008, 64, 569–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lie, H.J.; Cho, C.H.; Lee, S. Tongue-shaped frontal structure and warm water intrusion in the southern Yellow Sea in winter. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2009, 114, C01003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.A.; Park, J.E.; Choi, B.J.; Lee, S.H.; Shin, H.R.; Lee, S.R.; Byun, D.S.; Kang, B.; Lee, E. Schematic maps of ocean currents in the Yellow Sea and the East China Sea for science textbooks based on scientific knowledge from oceanic measurements. Sea 2017, 22, 151–171. (In Korean) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.W.; Wang, Q.Y.; Lü, Y.; Cui, H.; Yuan, Y.L. Observation of the seasonal evolution of the Yellow Sea Cold Water Mass in 1996–1998. Cont. Shelf Res. 2008, 28, 442–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.H.; Van, S.P.; Choi, B.J.; Chang, Y.S.; Kim, Y.H. The physical processes in the Yellow Sea. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2014, 102, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teague, W.J.; Jacobs, G.A.; Ko, D.S.; Tang, T.Y.; Chang, K.I.; Suk, M.S. Connectivity of the Taiwan, Cheju, and Korea Straits. Cont. Shelf Res. 2003, 23, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lie, H.J.; Cho, C.H.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, S.; Tang, Y.; Zou, E. Does the Yellow Sea Warm Current really exist as a persistent mean flow? J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2001, 106, 22199–22210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wu, D.; Lin, X.; Ma, C. The study of the Yellow Sea Warm Current and its seasonal variability. J. Hydrodyn. 2009, 21, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Chu, P.C. Thermal and haline fronts in the Yellow/East China Seas: Surface and subsurface seasonality comparison. J. Oceanogr. 2006, 62, 617–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, T.; Wang, R.; Chen, Y.Q.; Gao, S.W.; Wang, K. Autumn net copepod abundance and assemblages in relation to water masses on the continental shelf of the Yellow Sea and East China Sea. J. Mar. Syst. 2006, 59, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Huo, Y.; Yang, B. Zooplankton functional groups on the continental shelf of the Yellow Sea. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2010, 57, 1006–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.J.; Liu, G.X. Zooplankton community structure in the Yellow Sea and East China Sea in autumn. Braz. J. Oceanogr. 2015, 63, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.Q.; Zuo, T.; Yuan, W.; Sun, J.Q.; Wang, J. Spatial variation in zooplankton communities in relation to key environmental factors in the Yellow Sea and East China Sea during winter. Cont. Shelf Res. 2018, 170, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Park, W.; Moon, S.Y.; Cha, H.K. Distribution and indicator species of zooplankton in the East Sea, Yellow Sea and Northern East China Sea in winter. J. Environ. Biol. 2019, 40, 871–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, G.; Sun, X.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, X. Temporal variability in zooplankton community in the western Yellow Sea and its possible links to green tides. Peer J. 2019, 7, e6641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhuang, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Chen, H.; Ge, R.; Liu, G. Zooplankton assemblages and indicator species in the Changjiang River Estuary and its adjacent waters. Cont. Shelf Res. 2023, 260, 105000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Wang, J.; Zuo, T.; Shan, X.; Jin, X.; Sun, J.; Yuan, W.; Pakhomov, E.A. Seasonal changes in zooplankton community structure and distribution pattern in the Yellow Sea, China. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Park, W.; Choi, D.H.; Kang, H.K. Seasonal variation in the mesozooplankton community structure and indicator species of the Yellow Sea. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2024, 73, 103454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chihara, M.; Murano, M. An Illustrated Guide to Marine Plankton in Japan; Tokai University Press: Tokyo, Japan, 1997; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, R.; Wiebe, P.; Lenz, J.; Skjoldal, H.R.; Huntley, M. (Eds.) ICES Zooplankton Methodology Manual; Academic Press: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- ter Braak, C.J.F.; Šmilauer, P. Canoco Reference Manual and User’s Guide: Software for Ordination, version 5.0; Microcomputer Power: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dufrêne, M.; Legendre, P. Species assemblages and indicator species: The need for a flexible asymmetrical approach. Ecol. Monogr. 1997, 67, 345–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PC-ORD. Multivariate Analysis of Ecological Data, version 7; MjM Software Design: Corvallis, OR, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.wildblueberrymedia.net/ (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Choi, H.U.; Jeong, Y.S.; Choo, S.; Soh, H.Y. Variation in the Occurrence of Salp and Doliolid Assemblages in the Northeastern East China Sea from 2019 to 2023. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornils, A.; Schulz, J.; Schmitt, P.; Lanuru, M.; Richter, C.; Schnack-Schiel, S.B. Mesozooplankton distribution in the Spermonde Archipelago (Indonesia, Sulawesi) with special reference to the Calanoida (Copepoda). Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2010, 57, 2076–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kas’yan, V.V. Distribution and seasonal dynamics of the abundance of Centropages abdominalis Sato and C. tenuiremis Thompson et Scott (Copepoda) in Amursky Bay, Sea of Japan. Russ. J. Mar. Biol. 2004, 30, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellani, C.; Licandro, P.; Fileman, E.; Di Capua, I.; Mazzocchi, M.G. Oithona similis likes it cool: Evidence from two long-term time series. J. Plankton Res. 2016, 38, 703–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noda, M.; Ikeda, I.; Ueno, S.; Hashimoto, H.; Gushima, K. Enrichment of coastal zooplankton communities by drifting zooplankton patches from the Kuroshio front. Mar. Ecol. Progr. Ser. 1998, 170, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.S.; Choi, S.Y.; Seo, M.H.; Lee, S.J.; Soh, H.Y.; Youn, S.H. Spatiotemporal distribution characteristics of copepods in the water masses of the northeastern East China Sea. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Beardsley, R.C. Influence of stratification on residual tidal currents in the Yellow Sea. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 1999, 104, 15679–15701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.M.; Sun, S.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, B.; Ji, P. Abundance of Calanus sinicus across the tidal front in the Yellow Sea, China. Fish. Oceanogr. 2003, 12, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zuo, T.; Wang, K.E. The Yellow Sea cold bottom water—An oversummering site for Calanus sinicus (Copepoda, Crustacea). J. Plankton Res. 2003, 25, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, X.M.; Sun, S.; Yang, B.; Ji, P.; Zhang, Y.S.; Zhang, F. The combined effects of temperature and food supply on Calanus sinicus in the southern Yellow Sea in summer. J. Plankton Res. 2004, 26, 1049–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.T.; Sun, S.; Zhang, F. Seasonal variation of reproduction rates and body size of Calanus sinicus in the Southern Yellow Sea, China. J. Plankton Res. 2005, 27, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.K.; Lee, C.R.; Kim, D.; Yoo, S. Effects of enhanced pCO2 and temperature on reproduction and survival of the copepod Calanus sinicus. Ocean Polar Res. 2016, 38, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, T.; Uchiyama, I. Seasonal changes in the density and vertical distribution of nauplii, copepodites and adults of the genera Oithona and Oncaea (Copepoda) in the surface water of Toyama Bay, southern Sea of Japan. Plankton Benthos Res. 2008, 3, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lie, H.J.; Cho, C.H.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, S.; Tang, Y. Seasonal Variation of the Cheju Warm Current in the Northern East China Sea. J. Oceanogr. 2000, 56, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lie, H.J.; Cho, C. Seasonal circulation patterns of the Yellow and East China Seas derived from satellite-tracked drifter trajectories and hydrographic observations. Prog. Oceanogr. 2016, 146, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isobe, A. On the origin of the Tsushima Warm Current and its seasonality. Cont. Shelf Res. 1999, 19, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, H.B.; Jacobs, G.A.; Teague, W.J. Monthly variations of water masses in the Yellow and East China Seas. J. Oceanogr. 2000, 56, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Kang, H.K.; Myoung, J.G. Seasonal and interannual variation in mesozooplankton community structure off Tongyeong, southeastern coast of Korea, from 2011 to 2014. Ocean Sci. J. 2017, 52, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| May | Ind. m−3 | % | August | Ind. m−3 | % |

| Paracalanus copepodites | 805 | 17.8 | Paracalanus copepodites | 849 | 22.6 |

| Oithona similis | 582 | 12.9 | Doliolum nationalis | 523 | 13.9 |

| Calanus copepodites | 518 | 11.5 | Paracalanus parvus | 468 | 12.5 |

| Paracalanus parvus | 514 | 11.4 | Oithona atlantica | 210 | 5.6 |

| Oithona copepodites | 395 | 8.8 | Penilia avirostris | 177 | 4.7 |

| Acartia omorii | 275 | 6.1 | Calanus copepodites | 172 | 4.6 |

| Centropages abdominalis | 265 | 5.9 | Oikopleura dioica | 169 | 4.5 |

| Acartia copepodites | 194 | 4.3 | Sagittoid juvenile | 130 | 3.5 |

| Oithona atlantica | 171 | 3.8 | Acartia copepodites | 111 | 3.0 |

| Ditrichocorycaeus affinis | 156 | 3.5 | Oithona copepodites | 110 | 2.9 |

| Centropages copepodites | 132 | 2.9 | Acartia omorii | 101 | 2.7 |

| Corycaeus copepodites | 72 | 1.6 | Oithona similis | 90 | 2.4 |

| Oikopleura dioica | 59 | 1.3 | Copepod nauplii | 79 | 2.1 |

| Acartia hongi | 48 | 1.1 | Ditrichocorycaeus affinis | 77 | 2.0 |

| Hyperiid juvenile | 47 | 1.0 | Bivalve larvae | 37 | 1.0 |

| Copepod nauplii | 46 | 1.0 | Gastropod larvae | 36 | 1.0 |

| Calanus sinicus | 43 | 1.0 | |||

| October | Ind. m−3 | % | January | Ind. m−3 | % |

| Paracalanus copepodites | 1466 | 39.5 | Paracalanus copepodites | 222 | 20.9 |

| Paracalanus parvus | 650 | 17.5 | Oithona similis | 176 | 16.6 |

| Oikopleura dioica | 212 | 5.7 | Oithona copepodites | 149 | 14.0 |

| Oithona copepodites | 172 | 4.6 | Paracalanus parvus | 124 | 11.7 |

| Oithona similis | 107 | 2.9 | Oithona atlantica | 85 | 8.0 |

| Paracalanus aculeatus | 96 | 2.6 | Oikopleura dioica | 51 | 4.8 |

| Calanus copepodites | 90 | 2.4 | Copepod nauplii | 39 | 3.6 |

| Sagittoid juvenile | 85 | 2.3 | Calanus copepodites | 33 | 3.1 |

| Doliolum nationalis | 82 | 2.2 | Gastropod larvae | 26 | 2.5 |

| Oithona atlantica | 73 | 2.0 | Ditrichocorycaeus affinis | 20 | 1.9 |

| Ditrichocorycaeus affinis | 63 | 1.7 | Corycaeus copepodites | 16 | 1.5 |

| Corycaeus copepodites | 49 | 1.3 | Euchaeta copepodites | 16 | 1.5 |

| Copepod nauplii | 48 | 1.3 | Paracalanus aculeatus | 15 | 1.4 |

| Calanus sinicus | 44 | 1.2 | Calanus sinicus | 11 | 1.1 |

| Euchaeta copepodites | 39 | 1.0 |

| Statistic | Axis 1 | Axis 2 | Axis 3 | Axis 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eigenvalues | 0.1054 | 0.0462 | 0.0245 | 0.2361 |

| Explained variation (cumulative) | 10.54 | 15.15 | 17.6 | 41.22 |

| Pseudo-canonical correlation | 0.6677 | 0.5569 | 0.3498 | 0 |

| Explained fitted variation (cumulative) | 59.85 | 86.07 | 100 |

| May | August | ||||

| Group | Species | IndVal | Group | Species | IndVal |

| MA | Centropages copepodites | 58.0 | AA | Ophiopluteus | 79.3 |

| Centropages abdominalis | 55.3 | Muggiaea sp. | 60.5 | ||

| Acartia omorii | 54.7 | Penilia avirostris | 51.2 | ||

| Acartia copepodites | 51.5 | Decapod zoea | 51.2 | ||

| MB | Oithona atlantica | 64.8 | Polychaete larvae | 45.1 | |

| MC | Mysid juvenile | 40.0 | Corycaeus copepodites | 41.4 | |

| MD | Clausocalanus minor | 100 | Cirriped nauplii | 41.0 | |

| Ctenocalanus vanus | 100 | AB | Acartia omorii | 58.3 | |

| Oncaea venusta | 95.7 | Oithona atlantica | 51.5 | ||

| Paracalanus aculeatus | 93.1 | AC | Euchaeta copepodites | 48.4 | |

| Conchoecia spp. | 92.0 | AD | Temora copepodites | 94.8 | |

| Decapod zoea | 71.4 | Conchoecia spp. | 63.1 | ||

| Euchaeta copepodites | 70.8 | Flaccisagitta enflata | 55.5 | ||

| Lucifer juvenile | 48.8 | ||||

| Liriope sp. | 48.3 | ||||

| Canthocalanus pauper | 44.4 | ||||

| Canthocalanus copepodites | 44.4 | ||||

| Euphausiid calyptopis | 44.4 | ||||

| Lucifer protozoea | 41.9 | ||||

| October | January | ||||

| Group | Species | IndVal | Group | Species | IndVal |

| OA | Polychaete larvae | 48.3 | JA | Themisto sp. juvenile | 77.8 |

| Corycaeus copepodites | 47.0 | Oithona atlantica | 62.4 | ||

| Liriope sp. | 46.7 | Euphausiid nauplii | 56.9 | ||

| Ophiopluteus | 42.4 | Calanus copepodites | 49.9 | ||

| Oikopleura dioica | 40.5 | Ditrichocorycaeus affinis | 49.1 | ||

| OB | none | Oithona copepodites | 45.2 | ||

| OC | Conchoecia spp. | 61.7 | Oikopleura dioica | 43.3 | |

| Eucalanus copepodites | 55.8 | Calanus sinicus | 43.0 | ||

| Centropages dorsispinatus | 50.0 | Oithona similis | 40.5 | ||

| Euchaeta copepodites | 44.7 | JB | Euphausia pacifica | 72.0 | |

| OD | Clausocalanus furcatus | 78.7 | Euchaeta plana | 51.4 | |

| Clausocalanus copepodites | 76.4 | JC | Oncaea venusta | 84.4 | |

| Oithona fallax | 66.4 | Paracalanus denudatus | 83 | ||

| Clausocalanus minor | 59.9 | Scolecithricella dentata | 79.7 | ||

| Oncaea venusta | 58.3 | Oithona fallax | 78.5 | ||

| Triconia conifera | 48.5 | Conchoecia spp. | 76.2 | ||

| Paracalanus aculeatus | 45.9 | Scolecithricella copepodites | 74.2 | ||

| Triconia conifera | 73.1 | ||||

| Lucicutia copepodites | 72.7 | ||||

| Oncaea copepodites | 61.5 | ||||

| Oithona longispina | 57.9 | ||||

| Macrosetella gracilis | 57.2 | ||||

| Temoropia mayumbaensis | 57.1 | ||||

| Paracalanus aculeatus | 56.7 | ||||

| Ctenocalanus vanus | 55.2 | ||||

| Euchaeta concinna | 54.5 | ||||

| Lucicutia curta | 54.0 | ||||

| Bivalve larvae | 48.2 | ||||

| Euchaeta copepodites | 45.3 |

| Area | Clusters | Key Hydrography | Key Indicator Species | Ecological Affinity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coastal | MA, AA, OA | Tidal fronts | Polychaete larvae Ophiopluteus | Neritic |

| Cold water | MB, AB, OB | YSBCW | Oithona atlantica | Cold oceanic |

| Warm water | MD, AD, OD, JC | JWC, YSWC | Clausocalanus minor Paracalanus aculeatus | Warm oceanic |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, G.; Kang, H.-K.; Choi, D.H. Mesozooplankton Community Structure and Indicator Species in Relation to Seasonal Hydrography in the Yellow Sea and Northern East China Sea. Water 2025, 17, 3547. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243547

Kim G, Kang H-K, Choi DH. Mesozooplankton Community Structure and Indicator Species in Relation to Seasonal Hydrography in the Yellow Sea and Northern East China Sea. Water. 2025; 17(24):3547. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243547

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Garam, Hyung-Ku Kang, and Dong Han Choi. 2025. "Mesozooplankton Community Structure and Indicator Species in Relation to Seasonal Hydrography in the Yellow Sea and Northern East China Sea" Water 17, no. 24: 3547. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243547

APA StyleKim, G., Kang, H.-K., & Choi, D. H. (2025). Mesozooplankton Community Structure and Indicator Species in Relation to Seasonal Hydrography in the Yellow Sea and Northern East China Sea. Water, 17(24), 3547. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243547