Abstract

Flooding is one of Africa’s most impactful natural disasters, significantly affecting human lives, infrastructure, and economies. This study examines the spatial and temporal distribution of historical flood events across the continent from 1927 to 2020, with a focus on fatalities, affected populations, and economic damage. Data from the Emergency Events Database (EM-DAT), the fifth generation of bias-corrected European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts Reanalysis (ERA5), and the Climate Hazards Group InfraRed Precipitation with Stations (CHIRPS) observational datasets were used to calculate extreme precipitation indices—Consecutive Wet Days (CWD), annual precipitation on very wet days (R95PTOT), and Annual Maximum Precipitation (AMP). Spatial analysis tools and the Mann–Kendall test were used to assess trends in flood occurrences, while Pearson correlation analysis identified key meteorological drivers across 16 African capital cities for 1981–2019. A flood frequency analysis was conducted using Weibull, Gamma, Lognormal, Gumbel, and Logistic probability distribution models to compute flood return periods for up to 100 years. Results reveal a significant upward trend with a slope above 0.50 floods per year in flood frequency and impact over the period, particularly in regions such as West Africa (Nigeria, Ghana), East Africa (Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania), North Africa (Algeria, Morocco), Central Africa (Angola, Democratic Republic of Congo), and Southern Africa (Mozambique, Malawi, South Africa). Positive trends (at 99% significance level with slopes ranging between 0.50 and 0.60 floods per year) were observed in flood-related fatalities, affected populations, and economic damage across Regional Economic Communities (RECs), individual countries, and cities of Africa. The CWD, R95PTOT, and AMP indices emerged as reliable predictors of flood events, while non-stationary return periods exhibited low uncertainties for events within 20 years. These findings underscore the urgency of implementing robust flood disaster management strategies, enhancing flood forecasting systems, and designing resilient infrastructure to mitigate growing flood risks in Africa’s rapidly changing climate.

1. Introduction

Floods rank among the most devastating natural disasters globally, with their frequency and intensity projected to escalate with global warming [1]. This is particularly evident in Africa, where floods not only result in substantial loss of life and damage to infrastructure but also disrupt ecosystems, livelihoods, and economic activities [2,3]. Between 1930 and 2020, flood events in Africa caused over $1.40 billion in economic damage, claimed more than 31,500 lives, and affected approximately 90.8 million people [4,5].

Despite their severity and increasing frequency, comprehensive studies that examine the spatial and temporal patterns of floods across the African continent remain scarce [6,7,8]. Most existing research is region-specific or focused on specific single flood types, such as riverine, flash, or coastal floods, often over relatively short timescales [9,10,11,12,13]. For instance, ref. [8] identified trends in annual maximum peak discharge associated with precipitation changes, while other studies correlated flood magnitudes with soil moisture dynamics rather than direct precipitation events [14].

Regional studies have reported mixed trends of flood events. In West Africa, there has been a significant increase in flood frequency, and intensity, attributed to intensified precipitation, land-use changes, and urban development [12,15,16,17]. Conversely, Northern Africa shows no significant trends in flood frequency or magnitude [18]. Using the European Flood Alert System (EFAS) method, ref. [19] achieved over 85% detection accuracy for East African flood events, while limited studies in Central Africa have investigated flood events. However, ref. [20] have highlighted the significant rainfall trends, irregular distribution, and the impact of low slopes on flooding in Cameroon. Southern Africa, despite its relatively arid climate, experiences frequent flooding events, particularly along its eastern coastline, with major impacts on vulnerable communities [13,21]. While these studies offer valuable insights, they do not consider continent-wide patterns or integrate long-term trends required for robust flood risk management. Recent assessments, such as Chapter 12 of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report by Working Group I, highlight more frequent and intense floods due to climate change. Additionally, rising temperatures, shifting rainfall patterns, and increased extreme weather event changes across Africa were categorized from medium to high confidence, depending on the region [22].

The role of climate drivers, such as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), in modulating flood risks across Africa has been extensively documented [7]. However, human-induced factors, such as unregulated urban sprawl in flood-prone zones, exacerbate the risks of flooding, particularly in rapidly urbanizing regions like West Africa [12]. While these studies provide valuable insights into regional flood dynamics, there is a critical gap in research that integrates spatiotemporal flood analyses with non-stationary flood frequency analysis (NFFA) across extended periods and scales remains. Integrating NFFA in this study offers a more accurate prediction of flood return periods, addressing one of the critical gaps in flood risk management. Such integrated analyses are essential for understanding continent-wide flood patterns and for developing actionable flood risk management strategies. The availability of reanalysis datasets, such as ERA5, and remote sensing data, including CHIRPS, offers an opportunity to address this gap. These datasets are particularly beneficial in regions with sparse observational networks, enabling high-resolution analyses of extreme precipitation events and their impacts [23,24,25].

This study aims to fill this gap by comprehensively analyzing the spatial and temporal distribution of flood events in Africa from 1927 to 2020. The specific objectives are to: (i) analyze the spatial distribution of flood events and associated fatalities; (ii) explore trends in flood events and extreme precipitation indices; (iii) establish relationships between flood events and key precipitation extreme indices; (iv) perform, and compare flood frequency analysis to predict future flood events across different climate zone, and (v) conduct the uncertainty analysis associated with the flood frequency analysis. By identifying the most significant meteorological triggers of floods and understanding their spatial and temporal distribution, policymakers and urban planners are equipped to develop more effective prevention and mitigation measures.

The findings of this study are crucial for advancing flood disaster management strategies and the design of resilient infrastructure across Africa. Accurate return period estimates are indispensable for long-term infrastructure planning, especially in rapidly urbanizing areas where population density and economic activities amplify vulnerability to flooding.

This document is structured to guide the reader through a logical sequence of analyses and results. The next section describes the data sets and methods. The results section presents a detailed analysis of spatial and temporal trends of flood and extreme precipitation indices. This section also discusses the results of the return period analysis. The discussion section contextualizes these results within the wider literature. Finally, the conclusion summarizes the main findings, highlighting their relevance for policymakers and urban planners, and suggests directions for future research. Through this structured approach, the study aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of flooding dynamics in Africa and support the development of targeted evidence-based solutions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Domain

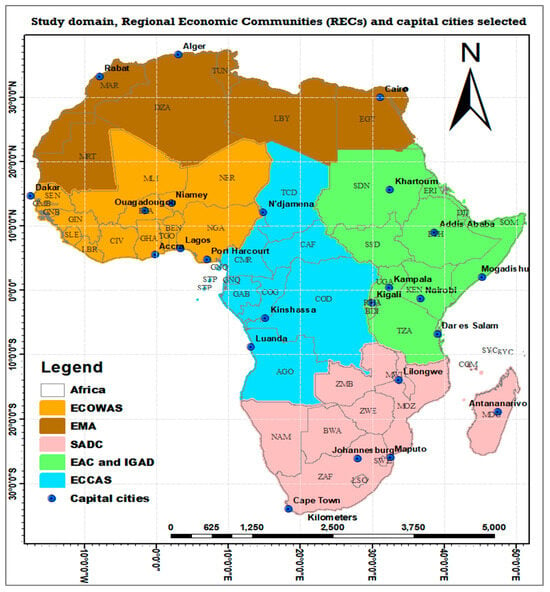

The study focuses on the African continent, spanning the latitudes 40° S to 40° N and longitudes 20° W to 60° E (Figure 1). Africa, the second largest and most populous continent, spans approximately 30.3 million km2, accounting for 6% of the Earth’s total surface and 20.4% of its land area [26,27]. The diversity of its topographical, meteorological, and hydrological conditions, the length of the rainy season, annual rainfall, and dominant vegetation cover, are well documented [28].

Figure 1.

Study domain includes the five Regional Economic Communities and 24 most flood-prone capital cities.

For this study, Africa is divided into five Regional Economic Communities (RECs; (https://au.int/en/organs/recs, accessed on 16 July 2024): The Economic Community for the West African States (ECOWAS) or Western Africa (WA), the Arab Maghreb Union (AMU) or Northern Africa (NA), Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) or Central Africa (CA), East African Community (EAC) combined with the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) or Eastern Africa (EA), and Southern African Development Community (SADC) or Southern Africa (SA) (Figure 1). This division allows for targeted analysis at the regional level, focusing on the most flood-prone areas, including 24 capital cities known for recurrent flood events.

2.2. Dataset Description

Flood event data for this study were sourced from the Emergency Events Database (EM-DAT), maintained by the Université Catholique de Louvain. EM-DAT provides a comprehensive historical record of flood hydrological disasters, spanning the period from 1927 to 2020 (www.emdat.be, accessed on 4 July 2023). It includes information on the total annual flood events (riverine, flash, coastal), fatalities, affected populations, and economic damages across 52 African countries. Despite the challenges in data quality and regional coverage, particularly in areas with sparse observational networks, the dataset is robust enough for a continent-wide analysis, with minimal missing values [29]. These records serve as a foundation for assessing spatial and temporal patterns in flood dynamics and their associated impacts. Socio-economic data, such as population figures, were obtained from the World Bank Database. The EM-DAT data were further categorized by RECs, individual countries, and capital cities to enable targeted analyses. This categorization allows for detailed insights into region-specific flood vulnerabilities and trends (Table S3). The EM-DAT data and socio-economic dataset ensure a comprehensive approach to understanding the impacts of flooding. This provides valuable information for disaster risk reduction and infrastructure planning in Africa.

Two precipitation datasets were used: The Climate Hazards Group InfraRed Precipitation with Stations (CHIRPS v2.0) and the ERA5 reanalysis. CHIRPS v2.0 has a spatial resolution of 0.05° and spans from 1981 to the near present. It combines satellite-derived precipitation estimates with in situ rain gauge observations [30]. CHIRPS is well-suited for extreme event analysis and climate trend studies due to its comprehensive spatial and temporal coverage. ERA5 is a global product from 1979 to 2019 at 0.5° × 0.5° spatial resolution. Bias-corrected daily precipitation estimates are used in this study [31,32]. These datasets were selected for their reliability in extreme event analysis, particularly in regions where ground-based observations are sparse [33,34].

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Spatial Analysis of Flood Events and Fatalities

Flood events, deaths, affected populations, and economic damage data from the EM-DAT database were analyzed across the five RECs, 52 countries, and 24 capital cities from 1927 to 2020. Countries and cities with flood events and fatalities exceeding the total flood and population median values were identified as the most exposed and were the focus of subsequent trend and frequency analyses.

2.3.2. Temporal Trend Analysis and Sen’s Slope Estimation

To assess the randomness and trends of flooding events and precipitation indices, auto-correlation functions (ACF) and partial auto-correlation functions (pACF) are applied to the time series data. Subsequently, the non-parametric Mann–Kendall (MK) test was used to identify monotonic trends in flood events and precipitation indices for the periods 1927–2020 and 1981–2019. These analyses provided insight into the data’s temporal structure and dependencies. The MK test, recommended by the World Meteorological Organization, is widely used in hydrological and meteorological studies due to its robustness and minimal reliance on underlying distributional assumptions [35,36]. To quantify the magnitude of identified trends, Sen’s slope estimator was applied, providing a measure of the rate of change. The MK rank test is a non-parametric, distribution-free method for trend analysis with minimal assumptions for time series [37]. More details on MK are presented in the SI document.

In this study, we used α = 99% and α = 95%. So, at a 5% significance level, the null hypothesis of no trend is rejected if |Zs| > 1.96 and rejected if |Zs| > 2.576 at a 1% significance level.

Finally, the MK statistic magnitude of the trend was calculated using Sen’s slope estimator. Ref. [38] developed a non-parametric procedure to estimate the slope of the trend in a sample of N pairs of data.

where Xj and Xk are the flood events or extreme precipitation indices value at tile j and k (j > k), respectively.

2.3.3. Extreme Precipitation Indices Computation and Relationship with Flood Events

Precipitation data were used to compute climate extreme indices CWD, R95PTOT, and AMP for the period 1981–2019. The relationship between these indices and flood events was analyzed using Pearson correlation coefficients, with a robust correlation threshold set for further non-stationary flood frequency analysis (NFFA).

2.3.4. Non-Stationary Extreme Values Distribution and Return Period

Given the variability in precipitation patterns across Africa, several probability distribution models were tested for flood frequency analysis (Table S1). This included the Weibull, Gamma, Lognormal, Gumbel, and Logistic distributions. These models were selected for their parsimony, computational stability, and established use in hydrological studies across Africa [39,40,41,42]. Notably, the Gumbel distribution is a special case of the Generalized Extreme Value (GEV) distribution widely used in extreme value theory. Parameters for all distributions were estimated using the Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) method (Equation (S6) in the Supplementary Materials). It is acknowledged that while MLE is asymptotically efficient, its performance can be sensitive to outliers and small sample sizes in the tails of the distribution [43]. The final model selection was based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), across all fitted distributions. Goodness-of-Fit (GoF) tests, including the Kolmogorov–Smirnov (K-S), Anderson-Darling (A-D) tests, were additionally applied to select the best-fitting model for each location [44].

The selected model was then used to estimate flood return periods ranging from 2 to 100. The variable (x) equals to or greater than a flood event of magnitude , occurs once in T years, then the probability of occurrence.

3. Results

3.1. Statistics and Spatial Distribution of Total Flood Events

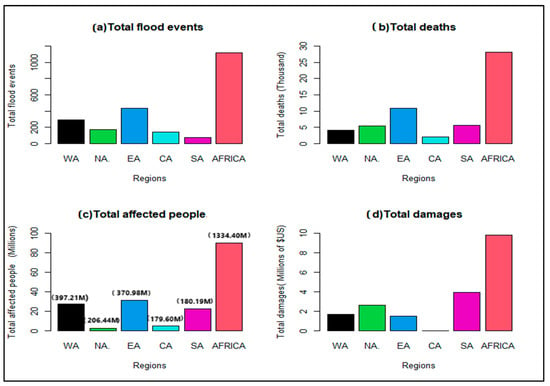

The bar plot of statistics and the spatial analysis underscore the urgent need for developing targeted flood risk management and mitigation strategies in these high-risk areas in the target RECs and countries. Figure 2 shows flood statistics and associated impacts, with the total 2020 population in brackets in the RECs. The EA (434), WA (292), and NA (171) regions recorded the highest occurrence of flood events out of the 1119 events in Africa over the period 1927 to 2020. Then, of the 28,136 total deaths in Africa, the EA (10,865), SA (5646), and NA (5374) regions also recorded a considerable number of deaths over the same period. The SA, NA, and WA regions experienced wide economic damage, about 3.92 million; 2.6 million; and 1.7 million dollars US, respectively. These results indicate that regions EA and WA are the most exposed to frequent flooding causing fatalities, while regions SA and NA are the most affected by economic loss and damage.

Figure 2.

Statistic bar plots in the Regional Economic Communities of Africa between 1927 and 2020 (WA: Western Africa; NA: Northern Africa; EA: Eastern Africa; CA: Central Africa; and SA: Southern Africa) of (a) total flood events, (b) total deaths, (c) total affected people within brackets above each region, the total population’s number of 2020 (in Millions), and (d) total damages.

It’s crucial to track flood occurrences, those affected, and fatalities in African countries. The spatial distribution (Figure 3a–d) highlighted the most exposed countries and the number of deaths and damage per capita in the Supporting Information (Table S3). By understanding this, we can create effective flood risk management plans, boost community resilience, and lessen the impact and loss of life from future floods. The results undergone that Kenya, Ethiopia, and Tanzania in EA; Nigeria, Ghana, and Niger in WA; Algeria and Morocco in NA; Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) in CA; and Mozambique, Malawi, and South Africa in SA are identified as the most occurrence of flood countries, with more than 30 flood events and with more than 170 deaths registered between 1927 and 2020 in each country. We also note that 0.03 and 0.61 people per capita were affected in Morocco, and Nigeria respectively. Moreover, South Africa, Mozambique, and Algeria more than 100 United States Dollar (USD) of loss and damage per person are registered respectively over this period. These countries have faced significant financial repercussions due to the frequency and severity of floods.

Figure 3.

Spatial distribution of (a) total flood events; (b) total deaths; (c) total affected people; and (d) total damage between 1927 and 2020.

The analysis identifies several countries as particularly exposed to flooding, with a high frequency of deaths and damage per capita.

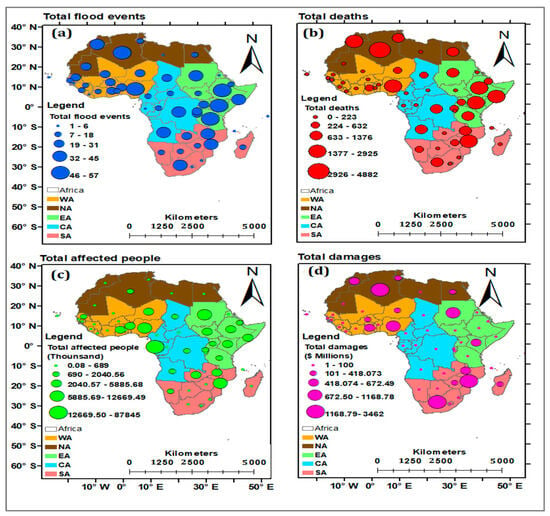

3.2. Temporal Analysis of Total Flood Events and Fatalities

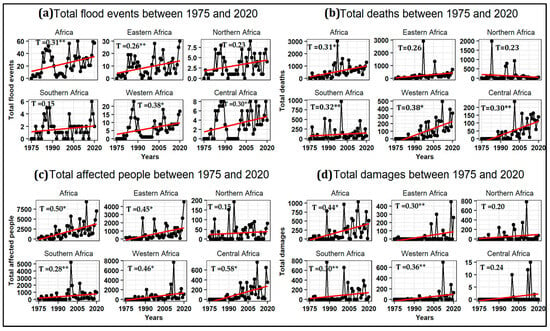

Floods have emerged as one of the most frequent and impactful natural disasters across Africa, posing significant challenges to urban resilience and infrastructure. The temporal analysis of floods, deaths, populations affected, and damage reveals the yearly patterns of these events in each REC and offers valuable insights to guide strategic decisions for long-term planning. The highly significant positives trends were detected in all RECs at the 99% confidence level (Figure 4). Trend slopes ranged from +0.50 to +0.67 per year for total flood events, deaths, and affected populations, while damages exhibited slightly lower trend slopes. Peaks in flood events and fatalities were observed in the years 2020, 2019, 2018, 2012, 2010, 2008, 2006, and 1986, particularly in EA, WA, and NA regions. Notably, specific years stand out for heightened flood activity: 2001, 2010, and 2015 in WA; 1997 and 2008 in NA; 2000, 2006, 2010, 2019, and 2020 in EA; 2010, 2015, 2019, and 2020 in CA; and 2000, 2003, 2007, 2010, and 2020 in SA, each recording more than five flood events.

Figure 4.

Temporal time series and trend values of the (a) total flood events, (b) total deaths, (c) total affected people, and (d) total damages in Western Africa, Northern Africa, Eastern Africa, Central Africa, Southern Africa and Africa between 1927 and 2020 [Ƭ = slope; + stands for positive trend; * p value < 0.01; the solid line in red is the trend line].

A known limitation of the EM-DAT database is the potential for under-reporting of events, particularly in the early part of the record and in regions with limited infrastructure and media coverage [5,45]. This is evident in Figure 4, which shows a marked increase in recorded events post-1975. This trend could reflect a genuine increase in flood frequency, but it is also conflated with improvements in international reporting, disaster awareness, and data collection methodologies over time.

To assess the potential impact of reporting biases on our trend analysis, a sensitivity analysis was performed. We re-calculated the Mann–Kendall trend statistic of flood events for the period 1975–2020, where the data record is more consistent. The results confirmed the significant increasing trend (S = 0.65, p < 0.01 in WA; S = 0.54, p < 0.01 in NA; S = 0.64, p < 0.01 in EA; and S = 0.64, p < 0.01 in SA), reinforcing the reliability of the main conclusion of increasing flood events (see Figure 5). The consistent increasing trend in this high impact subperiod provides additional confidence that the observed trend is not solely an artifact of improved reporting.

Figure 5.

Temporal time series and trend values of the (a) total flood events, (b) total deaths, (c) total affected people, and (d) total damages in Africa, Eastern Africa, Northern Africa, Southern Africa, Western Africa, and Central Africa, between 1975 and 2020 [Ƭ = slope; + stands for positive trend; * p value < 0.01; ** p value < 0.05; the solid line in red is the trend line].

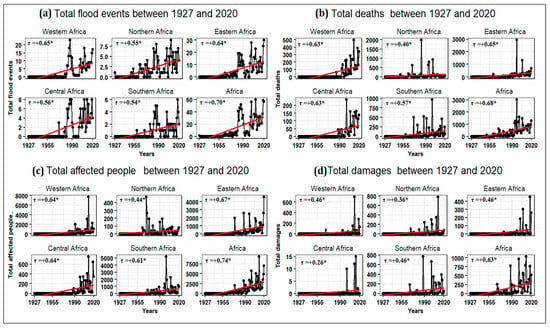

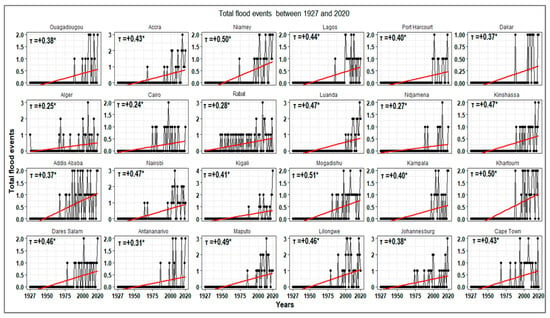

Figure 6 presents a comprehensive overview of the total flood events series in Africa’s most affected capital cities from 1927 to 2020. The analysis reveals highly significant positive trends in flood occurrences across numerous cities. For example, with Mogadishu (Ƭ = +0.51 *), Khartoum (Ƭ = +0.50 *), Niamey (Ƭ = +0.50 *), Maputo (Ƭ = +0.49 *), Nairobi (Ƭ = +0.47 *), Kinshasa (Ƭ = +0.47 *), Lilongwe (Ƭ = +0.46 *), and Dares Salam (Ƭ = +0.46 *) are experiencing the highest frequencies. These findings underscore the urgency of enhancing flood risk management strategies and implementing adaptive measures to mitigate the escalating impacts of flooding on urban populations across the continent.

Figure 6.

Temporal time series and trend values of the total flood events in the capital cities between 1927 and 2020 [Ƭ = slope; + stands for positive trend; * p value < 0.01; the solid line in red is the trend line].

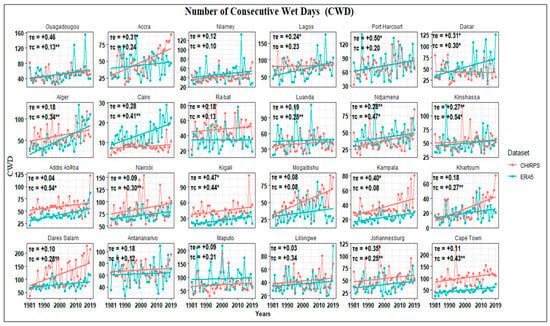

3.3. Trends in Extreme Precipitation Indices and Their Relationship with Total Flood Events

To develop robust climate information, it is crucial to understand the shifts in extreme rainfall patterns, including metrics like CWD, R95PTOT, and AMP. This information allows us to evaluate the effects of climate change on water resources and the risks of flooding. The analysis examines these changes from 1981 to 2019, utilizing comprehensive data from the ERA5 and CHIRPS datasets, illustrated in Figure 7 and Figures S2 and S3, to shed light on how extreme rainfall patterns are evolving across various regions. All the indices show a positive trend and none a negative trend. The trends are also significant with AMP observed at 30% (ERA5) and 25% (CHIRPS) of the stations. R95PTOT and CWD exhibited significant trends at 42% and 25%; 37% and 58% of the ERA5 and CHIRPS stations, respectively.

Figure 7.

Temporal time series and trend slope values Te(Tc) ERA5(CHIRPS) datasets respectively for the Consecutive Wet Days in the capital cities between 1981 and 2019. [+stands for positive trend, * p value < 0.01; and ** p value < 0.05].

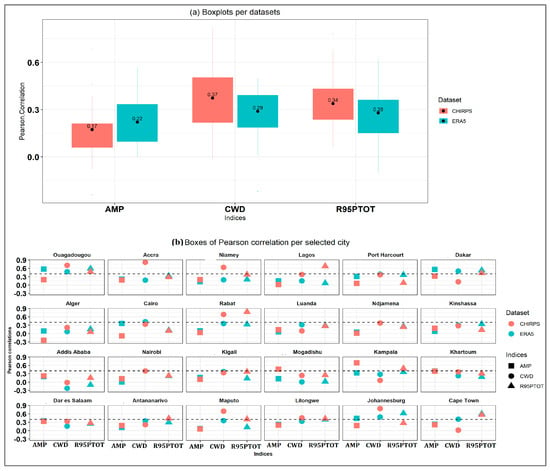

We examined how flood events connect to extreme climate indices to identifying the main driver of floods and enhancing predictions. Figure 8 looks at Pearson correlation values, which compare flood events with indices such as CWD, R95PTOT, and AMP (a). This analysis uses data from CHIRPS and ERA5, averaged for the entire continent and specific cities (b). The distribution in (a) shows that the R95PTOT index generally exhibits more variability in correlation compared to the AMP and CWD and indicating that the CHIRPS dataset indices generally strongly correlate with flood events compared to ERA5, and for CWD and R95PTOT. The mean values are indicated as black points with numerical annotations, indicating higher correlations for the CHIRPS dataset across most indices. Consequently, the maximum mean correlation value was used as a threshold for selecting 16 stations for further non-stationary flood frequency analysis (NFFA).

Figure 8.

Boxplots of Pearson correlations of the datasets with the average values in black circles inside each boxplot (a) and Boxes of the correlation values between total flood events and extreme precipitation indices between 1981 and 2019 (b). The dashed horizontal line represents the threshold of the maximum correlation between flood events and the indicated index.

Each box in (b) of Figure 8 represents a different city, showing variation in correlation strengths and patterns for each index. Generally, the CHIRPS and ERA5 datasets yield different correlations, highlighting regional differences in how these indices relate to flood events. Moreover, most cities show stronger correlations for the CWD and R95PTOT indices in both datasets compared to AMP the index. This indicates that consecutive wet days and R95PTOT are more reliably associated with observed data than the AMP index. The CWD index emerged as the most reliable predictor of flood events in many capital cities, making it a crucial metric for return period analysis. This is because, in many African cities, prolonged consecutive rainfall is a key indicator of potential flooding due to inadequate drainage infrastructure, rapid urbanization, and high soil saturation levels. The CHIRPS observation dataset was chosen for flood return period analysis due to its stronger correlation values with CWD.

For flood management, using CWD may provide better guidance for assessing flood risks, while R95PTOT, and AMP could complement these models when extreme rainfall events need to be considered in specific regions.

3.4. Non-Stationary Extreme Values Distribution and Return Period Analysis

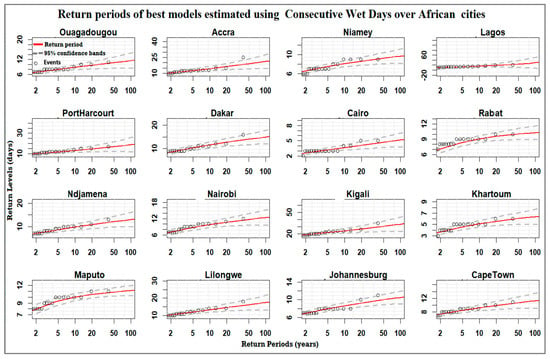

Flood return period is crucial for assessing flood risk and designing resilient infrastructure in urban environments. Figure 9 presents the estimated return periods of consecutive wet days (CWD) across various African cities, with return levels (in days) plotted against return periods (in years) on a logarithmic scale (more detail in Table S6). The red lines represent the best-fit models (Table S5), while the gray shading indicates 95% confidence bands, highlighting uncertainty in return period estimates. The observed events (black circles) show variability in wet day patterns, with notable differences in return levels and confidence intervals across cities.

Figure 9.

Non-stationary return period and return levels based on 39-year period of the Consecutive Wet Days events represented by the written circles in the cities.

This analysis underscores the complexities of non-stationary flood return period estimation. Cities such as Kigali, Accra, Lagos, and Port Harcourt exhibit high CWD values for return periods of 2, 20, and 100 years, emphasizing the need for infrastructure planning that accounts for at least a 20-year return period to mitigate flood risks. Notably, uncertainties increase significantly beyond a 20-year return period, suggesting that extreme flood predictions are less reliable due to limited historical data and potential gaps in flood monitoring. However, return periods between 2 and 20 years exhibit lower uncertainty, indicating that models for more frequent flood events provide more reliable estimates.

Given these findings, flood resilience strategies should prioritize adaptation measures for frequent, lower-magnitude flood events while improving data collection and modeling efforts to enhance the reliability of extreme flood predictions.

To elucidate the regional differences in non-stationary flood behavior, a comparative analysis was conducted for cities representing distinct climatic zones: Coastal Savanna (Accra), Semi-Arid (Dakar), and Mediterranean (Rabbat). The 100-year return level for Consecutive Wet Days (CWD) in Accra showed a 51.8% increase compared to the stationary model, likely due to a combination of climatic factors and rapid urbanization. Dakar exhibited a 45.9% increase, reflecting less intensified rainfall in semi-arid zone. In contrast, Rabbat showed a minimal change (36.4%), consistent with its mediterranean climate conditions (See Table S6). This analysis underscores that the impact of non-stationarity is not uniform across Africa and is surely modulated by local and regional drivers.

3.5. Uncertainty Analysis

A comprehensive uncertainty analysis was conducted to assess the reliability of the flood frequency estimates. This analysis addressed three primary sources of uncertainty [2,46]: Parameter Uncertainty: Confidence intervals (95%) for the parameters of the selected distributions were estimated using a bootstrapping procedure with 1000 resamples.

Model Uncertainty: The sensitivity of the return level estimates to the choice of the probabilistic model was assessed by comparing the results from the top three distributions ranked by AIC and BIC values [42,47]. The range of these estimates is reported in Table S5 of Supplementary Information.

Data Uncertainty: The impact of combining datasets with different spatial resolutions (EM-DAT vs. satellite-derived and reanalysis precipitation) was evaluated. A sensitivity test was performed by selecting the high correction values between flood events and precipitation dataset in the location, as discussed in Section 3.3. The findings indicate that while absolute values may shift, the selected threshold value remains robust.

4. Discussion

This study investigates the spatial and temporal distribution of flood events and their return periods across Africa’s RECs from 1927 to 2020, leveraging data from the EM-DAT and precipitation datasets (ERA5 and CHIRPS). The findings highlight that the most flood-prone countries include Nigeria, Ghana, and Niger in WA; Algeria and Morocco in NA; Sudan, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Tanzania in EA; Angola and the DRC in CA; and Mozambique, Malawi, and South Africa in SA. These countries’ vulnerability is strongly influenced by their locations within major river basins, such as the Niger, Volta, Nile, and Congo basins, as well as by region-specific factors like coastal monsoons, sea-level rise, extreme precipitation events, and low soil infiltration rates [48,49]. The spatial distribution of flood-related fatalities closely aligns with flood occurrences, disproportionately impacting populous countries such as Nigeria, Sudan, and Mozambique, while economic losses were most pronounced in Nigeria, Algeria, Sudan, Mozambique, and South Africa. These patterns underscore the uneven distribution of disaster risks, which are often exacerbated by poverty and inadequate infrastructure in less developed regions [50].

Temporal trends analyzed using the Mann–Kendall test revealed significant increases in flood events, fatalities, affected populations, and economic damage across all RECs, with EA reporting higher numbers of flood events and affected populations, and SA experiencing greater economic losses. These trends are driven by factors such as population growth, urbanization, and increasing precipitation intensity, in line with earlier studies [6]. The study further assessed extreme precipitation indices—CWD, R95PTOT, and AMP—revealing strong correlations with flood events, particularly when using CHIRPS observations. The higher accuracy of CHIRPS, which integrates satellite and station data with fine spatial resolution (0.05°), underscores its suitability for flood-related analyses in Africa [30].

Flood frequency analysis identified the Gumbel and Weibull models as the most appropriate for analyzing CWD across the continent, though regional variability precludes the adoption of a single probability distribution model. While shorter return periods yielded reliable results with lower uncertainties, longer periods (beyond 20 years) introduced significant variability, consistent with prior studies [51].

Despite the robustness of these results, the study acknowledges limitations, including uncertainties in EM-DAT, the scarcity of reliable observational flood data, and the inherent constraints of reanalysis datasets [52]. Furthermore, some vulnerable countries and cities, such as Ivory Coast, Cameroon, Chad, and Durban, were excluded due to data gaps, highlighting the need for greater investment in data collection, quality control, and accessibility. While univariate trends and correlation methods have faced criticism, their validity is supported by previous research [14,53]. Another limitation of this analysis is the exclusive use of CWD, R95PTOT, and AMP extreme precipitation indices, while excluding other relevant indices such as RX1day, RX5day, R10mm, and R20mm. These omitted indices may also serve as important flood triggers in Africa, potentially affecting the completeness of our flood risk assessment [54,55]. The minor influence of probability distribution models and estimation methods further supports the reliability of the findings, which were validated against existing studies [56]. This study emphasizes the need to address data limitations and improve flood risk management strategies to mitigate future impacts in Africa’s most vulnerable regions.

5. Conclusions

Flood events have profound negative impacts on the human population, arising from various hydro-meteorological conditions and climate extremes. This study offers a comprehensive analysis of the spatial and temporal distribution of flood events and associated fatalities across Africa, leveraging data from the EM-DAT to map these occurrences across African countries and capital cities within the RECs.

Mann–Kendall trend analysis was applied to time series data for flood events and extreme precipitation indices, including Consecutive Wet Days (CWD), the annual total precipitation on very wet days (R95PTOT), and Annual Maximum Precipitation (AMP), all computed from CHIRPS observation and ERA5 reanalysis datasets. These extreme climate indices were correlated with total flood events to identify potential flood triggers at each city location. Using a correlation threshold, 16 capital cities were selected for non-stationary flood frequency analysis, employing the best-fitting probability distribution model among Weibull, Gamma, Lognormal, Normal, and Logistic distributions.

Key Findings:

- Flood-Prone Countries: Nigeria, Ghana, and Niger in West Africa; Algeria and Morocco in North Africa; Ethiopia, Kenya, Sudan, and Tanzania in East Africa; Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) in Central Africa; and Mozambique, Malawi, and South Africa in Southern Africa are identified as the most flood-prone countries, with the highest numbers of total flood events and fatalities.

- Impacts and Damages: Significant impacts and damages per capita were observed in Nigeria and Niger (West Africa), Sudan and Ethiopia (East Africa), Gabon (Central Africa), and Mozambique and Zimbabwe (Southern Africa), with these regions experiencing the highest levels of affected populations and economic losses.

- Flood Event Distribution: Most of the flood events from 1975 to 2020 occurred in East Africa, West Africa, and North Africa. East Africa, Southern Africa, and North Africa also recorded the highest frequency of deaths and damage per capita.

- Trends in Floods and Fatalities: A highly significant positive trend in flood events and fatalities was observed across all RECs, although the magnitude of these trends varies by country and capital city. Significant trends were also noted in extreme precipitation indices in some regions.

- Main Triggers: The CWD index, particularly when computed using CHIRPS observation datasets, emerged as a major trigger for flood events in the capital cities.

- Non-stationary Flood Return Period: Non-stationary flood returns periods, calculated for up to 100 years, exhibited low uncertainties for return periods of less than 20 years, highlighting the reliability of these estimates for short-term infrastructure planning.

Flood risk affects the entire continent including drier regions. That flood-related deaths were highest in North Africa suggesting that arid regions are more vulnerable to flood deaths, likely because flooding occurs infrequently, and populations are not flood-adapted or resilient.

Increasing trends in heavy rainfall and flood metrics mean a continually growing urban and peri-urban population is exposed to increasing flood risk and consequent impacts.

As direct measurement of flooding is often not possible, CWD can serve as a valuable proxy for flooding in many regions of Africa due to their direct relationship with prolonged rainfall events, which are a primary driver of flood occurrences.

The insights provided by NFFA enable urban planners to prioritize investments in infrastructure that can withstand frequent and severe flood events, ensuring sustainability under changing climatic conditions.

These findings provide critical insights for policymakers and urban planners in African RECs. The results can guide the development of effective flood disaster control strategies and the construction of resilient infrastructure capable of withstanding the challenges posed by rapid population growth and global warming. The need to develop risk models and forecasting systems to manage these impacts in Africa is clear. These include strategies tailored to regional vulnerabilities, such as strengthening early warning systems, improving land-use planning, and incorporating climate-resilient infrastructure designs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/w17243531/s1, Figure S1: Flood events trend time series for the countries (1927–2020); Figure S2: Temporal time series and trend slop values Te(Tc) ERA5 (CHIRPS) datasets respectively for the total very wet day amount in the capital cities between 1981 and 2019. [+stands for positive trend, * is for p value < 0.01; and ** is for p value < 0.05]; Figure S3: Same as Figure 6 for the Annual Maximum Precipitation; Figure S4: Histograms and densities of CWD for probability distribution functions between 1981 and 2019. The X-axis scale is not fixed as the CWD value varies considerably across locations; Table S1: Probability density functions of the marginal distributions; Table S2: Total flood events, deaths, affected people, and damages statistics in the Regional Economic Commissions and the whole of Africa; Table S3: Total flood events, deaths, affected people, and damages statistics in the selected countries in Africa; Table S4: Flood events trend analysis statistics in the countries (1927–2020); Table S5: Model parameters and performance statistics; Table S6: Return period and return levels (days) values for 16 capital cities in Africa. References [57,58,59,60,61,62] are cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.K.H. and M.B.S.; methodology, D.K.H. and M.B.S.; software, D.K.H.; validation, D.K.H. and M.B.S.; formal analysis; investigation; resources.; data curation, D.K.H.; writing—original draft preparation, D.K.H.; writing—review and editing, D.K.H., M.T., A.D., J.S.P., C.L., P.W., W.M.-O. and B.H.; supervision, M.B.S. and B.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by a grant from the Government of Canada, provided through Global Affairs Canada, www.international.gc.ca, and the International Development Research Centre, www.idrc.ca and implemented at the African Institute for Mathematical Sciences, www.nexteinstein.org.

Data Availability Statement

Total flood events data and fatalities were obtained from the EM-DAT website (https://www.emdat.be/; accessed on 4 July 2023). CHIRPS precipitation data was downloaded from: https://www.chc.ucsb.edu/data/chirps; accessed on 4 July 2023. and ERA5- bias-corrected reanalysis were retrieved from the Copernicus Climate Change Service Climate Data Store: https://climate.copernicus.eu/climate-data-store; accessed on 4 July 2023.

Acknowledgments

Authors acknowledge the developers of EM-DAT, CHIRPS, and ERA5 for providing flood datasets, precipitation observation, and reanalysis datasets.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript.

| EM-DAT | Emergency Events Database |

| ERA5 | European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts Reanalysis |

| CHIRPS | Climate Hazards Group InfraRed Precipitation with Stations |

| CWD | Consecutive Wet Days |

| R95PTOT | annual precipitation on very wet days |

| AMP | Annual Maximum Precipitation |

| MK | Mann–Kendall |

| RECs | Regional Economic Communities |

| EFAS | European Flood Alert System |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| ENSO | El Niño-Southern Oscillation |

| ECOWAS | Economic Community for the West African States |

| WA | Western Africa |

| AMU | Arab Maghreb Union |

| NA | Northern Africa |

| ECCCAS | Economic Community of Central African States |

| CA | Central Africa |

| EAC | East African Community |

| IGAG | Intergovernmental Authority on Development |

| EA | Eastern Africa |

| SADC | Southern African Development Community |

| SA | Southern Africa |

| NFFA | Non-stationary Flood Frequency Analysis |

| ACF | auto-correlation functions |

| pACF | partial auto-correlation functions |

| GoF | Goodness-of-Fit |

| K-S | Kolmogorov–Smirnov |

| A-D | Anderson-Darling |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| BIC | Bayesian Information Criterion |

| DRC | Democratic Republic of Congo |

| USD | United States Dollar |

References

- Doblas-Reyes, F.J.; Sörensson, A.A.; Almazroui, M.; Dosio, A.; Gutowski, W.J.; Haarsma, R.; Hamdi, R.; Hewitson, B.; Kwon, W.-T.; Lamptey, B.L.; et al. Linking Global to Regional Climate Change. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S.L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; p. 233. [Google Scholar]

- AghaKouchak, A.; Chiang, F.; Huning, L.S.; Love, C.A.; Mallakpour, I.; Mazdiyasni, O.; Moftakhari, H.; Papalexiou, S.M.; Ragno, E.; Sadegh, M. Climate Extremes and Compound Hazards in a Warming World. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2020, 48, 519–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, V.O.; Ilori, O.W. Projected Drought Events over West Africa Using RCA4 Regional Climate Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2020, 4, 329–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dottori, F.; Szewczyk, W.; Ciscar, J.-C.; Zhao, F.; Alfieri, L.; Hirabayashi, Y.; Bianchi, A.; Mongelli, I.; Frieler, K.; Betts, R.A. Increased human and economic losses from river flooding with anthropogenic warming. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 781–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, V.; Sen, S. Disaster damage records of EM-DAT and DesInventar: A systematic comparison. Econ. Disasters Clim. Chang. 2020, 4, 295–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Baldassarre, G.; Montanari, A.; Lins, H.; Koutsoyiannis, D. Flood fatalities in Africa: From diagnosis to mitigation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2010, 37, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.J.; Chai, Y.Q.; Yang, L.S.; Li, H.R. Spatio-temporal distribution of flood disasters and analysis of influencing factors in Africa. Nat. Hazards 2016, 82, 721–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramblay, Y.; Villarini, G.; Zhang, W. Observed changes in flood hazard in Africa. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 1040b5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramblay, Y.; Amoussou, E.; Dorigo, W.; Mahé, G. Flood risk under future climate in data sparse regions: Linking extreme value models and flood generating processes. J. Hydrol. 2014, 519, 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aich, V.; Koné, B.; Hattermann, F.F.; Paton, E.N. Time Series Analysis of Floods across the Niger River Basin. Water 2016, 8, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapolaki, R.S.; Reason, C.J.C. Tropical storm Chedza and associated floods over south-eastern Africa. Nat. Hazards 2018, 93, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badou, F.D.; Hounkpe, J.; Yacouba, Y.; Ibrahim, M.; Bossa, A.Y. Increasing Devastating Flood Events in West Africa: Who is to Blame? In Regional Climate Change Series; WASCAL Publishing: Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 2019; pp. 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, K. Flooding trends and their impacts on coastal communities of Western Cape Province, South Africa. Geo. J. 2021, 87, 453–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramblay, Y.; Villarini, G.; El Khalki, E.M.; Gründemann, G.; Hughes, D. Evaluation of the Drivers Responsible for Flooding in Africa. Water Resour. Res. 2021, 57, e2021WR029595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aich, V.; Liersch, S.; Vetter, T.; Fournet, S.; Andersson, J.; Calmanti, S.; van Weert, F.; Hattermann, F.F.; Müller, E.N. Flood projections for the Niger River Basin under future land use and climate change. Sci. Total. Environ. 2015, 562, 666–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nka, B.N.; Oudin, L.; Karambiri, H.; Paturel, J.E.; Ribstein, P. Trends in floods in West Africa: Analysis based on 11 catchments. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2015, 19, 4707–4719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houteta, D.K.; Tall, M.; Nonki, R.M.; Patel, N.; Sylla, M.B.; Djaman, K.; Atchonouglo, K.; Hewitson, B. Flood frequency and amplitude analysis under changing climate scenarios in the Mono River Basin, West Africa. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2025, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramblay, Y.; El Khalki, E.M.; Khedimallah, A.; Sadaoui, M.; Benaabidate, L.; Boulmaiz, T.; Boutaghane, H.; Dakhlaoui, H.; Hanich, L.; Ludwig, W.; et al. Regional flood frequency analysis in North Africa. J. Hydrol. 2024, 630, 130678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiemig, V.; Pappenberger, F.; Thielen, J.; Gadain, H.; De Roo, A.; Bodis, K.; De Roo, A.P.J.; Bodis, K.; Del Medico, M.; Muthusi, F. Ensemble flood forecasting in Africa: A feasibility study in the Juba—Shabelle river basin. Atmos. Sci. Lett. 2010, 11, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denise, T.; Fozong, N.; Tiafack, O.; Tchakonte, S.; Guillaine, C.; Ngeumo, N.; Badariotti, D. Analysis of Weather Anomalies to Assess the 2021 Flood Events in Yaounde, Cameroon (Central Africa). Am. J. Clim. Change 2023, 12, 292–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashao, F.M.; Mothapo, M.C.; Munyai, R.B.; Letsoalo, J.M.; Mbokodo, I.L.; Muofhe, T.P.; Matsane, W.; Chikoore, H. Extreme Rainfall and Flood Risk Prediction over the East Coast of South Africa. Water 2023, 14, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranasinghe, R.; Ruane, A.C.; Vautard, R.; Arnell, N.; Coppola, E.; Cruz, F.A.; Dessai, S.; Islam, A.S.; Rahimi, M.; Carrascal, D.R.; et al. Climate Change Information for Regional Impact and for Risk Assessment. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S.L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylla, M.B.; Giorgi, F.; Coppola, E.; Mariotti, L. Uncertainties in daily rainfall over Africa: Assessment of gridded observation products and evaluation of a regional climate model simulation. Int. J. Clim. 2013, 33, 1805–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembélé, M.; Zwart, S.J. Evaluation and comparison of satellite-based rainfall products in Burkina Faso, West Africa. Int. J. Remote. Sens. 2016, 37, 3995–4014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Bright, J.M. Worldwide validation of 8 satellite-derived and reanalysis solar radiation products: A preliminary evaluation and overall metrics for hourly data over 27 years. Sol. Energy 2020, 210, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawere, M. Theorising Development in Africa: Towards Building an African Framework of Development; Langaa RPCIG; African Books Collective: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, T.; Bowyer, P.; Rechid, D.; Pfeifer, S.; Raffaele, F.; Remedio, A.R.; Teichmann, C.; Jacob, D. Analysis of Compound Climate Extremes and Exposed Population in Africa Under Two Different Emission Scenarios. Earths Futur. 2020, 8, e2019EF001473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiemig, V.; Bisselink, B.; Pappenberger, F.; Thielen, J. A pan-African medium-range ensemble flood forecast system. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2015, 19, 3365–3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.L.; Kharb, A.; Tubeuf, S. The untold story of missing data in disaster research: A systematic review of the empirical literature utilising the Emergency Events Database (EM-DAT). Environ. Res. Lett. 2023, 18, 103006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, C.; Peterson, P.; Landsfeld, M.; Pedreros, D.; Verdin, J.; Shukla, S.; Husak, G.; Rowland, J.; Harrison, L.; Hoell, A.; et al. The climate hazards infrared precipitation with stations—A new environmental record for monitoring extremes. Sci. Data 2015, 2, 150066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucchi, M.; Weedon, G.P.; Amici, A.; Bellouin, N.; Lange, S.; Schmied, H.M.; Hersbach, H.; Buontempo, C. WFDE5: Bias-adjusted ERA5 reanalysis data for impact studies. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2020, 12, 2097–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Hirahara, S.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Schepers, D.; et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2020, 146, 1999–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinku, T.; Funk, C.; Peterson, P.; Maidment, R.; Tadesse, T.; Gadain, H.; Ceccato, P. Validation of the CHIRPS satellite rainfall estimates over eastern Africa. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2018, 144, 292–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tall, M.; Bonan, B.; Zheng, Y.; Guichard, F.; Simina, M.; Gaye, A.T.; Sintondji, L.O.; Hountondji, F.C.C.; Nikiema, P.M. Towards a Long-Term Reanalysis of Land Surface Variables over Western Africa: LDAS-Monde Applied over Burkina Faso from 2001 to 2018. Remote. Sens. 2019, 11, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, A.I. Kendall Rank Correlation and Mann-Kendall Trend Test. R Package Kendall. pp. 1–10. 2005. Available online: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=2216873 (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Mann, H.B. Nonparametric tests against trend. Econometrica 1945, 13, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golshan, M.; Sciences, S.A.; Darabi, H.; Adamowski, J.F. Using the Mann—Kendall test and double mass curve method to explore stream flow changes in response to climate and human activities Uncorrected Proof. J. Water Clim. Chang. 2019, 10, 725–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A.K.; Niedzielski, T. Statistical Characteristics of Riverflow Variability in the Odra River Basin, Southwestern Poland. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2010, 19, 387–397. [Google Scholar]

- van der Spuy, D.; Plessis, J.A.D. Flood frequency analysis—Part 1: Review of the statistical approach in South Africa. Water SA 2022, 48, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.; Du, T.; Xu, C.Y.; Guo, S.; Jiang, C.; Gippel, C.J. Non-stationary annual maximum flood frequency analysis using the norming constants method to consider non-stationarity in the annual daily flow series. Water Resour. Manag. 2015, 29, 3615–3633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ologhadien, I. Comparative Evaluation of Probability Distribution Models of Flood flow in Lower Niger Basin. Eur. J. Eng. Technol. Res. 2021, 6, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paola, F.; Giugni, M.; Pugliese, F.; Annis, A.; Nardi, F. GEV parameter estimation and stationary vs. non-stationary analysis of extreme rainfall in African test cities. Hydrology 2018, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.L. Maximum likelihood estimation in a class of nonregular cases. Biometrika 1985, 72, 67–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, M.; Rasool, M.T.; Ahmad, M.I. Anderson Darling and Modified Anderson Darling Tests for. Pak. J. Appl. Sci. 2003, 3, 85–88. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, G.; Hwang, S.N. Spatial–Temporal snapshots of global natural disaster impacts Revealed from EM-DAT for 1900–2015. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2019, 10, 912–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papalexiou, S.M.; Koutsoyiannis, D. A global survey on the seasonal variation of the marginal distribution of daily precipitation. Adv. Water Resour. 2016, 94, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anghel, C.G.; Ianculescu, D. Application of the GEV Distribution in Flood Frequency Analysis in Romania: An In-Depth Analysis. Climate 2025, 13, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Mena, M.; Albaladejo, J.; Castillo, V.M. Factors influencing surface runoff generation in a Mediterranean semi-arid environment: Chicamo watershed, SE Spain. Hydrol. Process. 1998, 12, 741–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aich, V.; Koné, B.; Hattermann, F.F.; Müller, E.N. Floods in the Niger basin—Analysis and attribution. Nat. Hazards Eart Syst. Sci. 2014, 2, 5171–5212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlade, J.; Bankoff, G.; Abrahams, J.; Cooper-Knock, S.J.; Cotecchia, F.; Desanker, P.; Erian, W.; Gencer, E.; Gibson, L.; Girgin, S. Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction 2019; UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, L.; AghaKouchak, A.; Gilleland, E.; Katz, R.W. Non-stationary extreme value analysis in a changing climate. Clim. Chang. 2014, 127, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delforge, D.; Wathelet, V.; Below, R.; Sofia, C.L.; Tonnelier, M.; van Loenhout, J.A.F.; Speybroeck, N. EM-DAT: The Emergency Events Database. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2025, 124, 105509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, S.K.; Luo, J.-J.; Masson, S.; Delecluse, P.; Gualdi, S.; Navarra, A.; Yamagata, T. Paramount impact of the Indian Ocean dipole on the East African short rains: A CGCM study. J. Clim. 2005, 18, 4514–4530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munzhedzi, L.; Mugari, E.; Nethengwe, N.S.; Gumbo, A.D. Trends in extreme rainfall and their relationship to flooding episodes in Vhembe district, South Africa. Environ. Res. Commun. 2024, 6, 095016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojara, M.A.; Yunsheng, L.; Babaousmail, H.; Wasswa, P. Trends and zonal variability of extreme rainfall events over East Africa during 1960–2017. Nat. Hazards 2021, 109, 33–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbert, K.; Nguyen, C.C.; Payrastre, O.; Gaume, E. Reducing uncertainty in flood frequency analyses: A comparison of local and regional approaches involving information on extreme historical floods. J. Hydrol. 2016, 541, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.D.; Murthy, D.N.P.; Xie, M. Weibull distributions. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Stat. 2011, 3, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, W.H. A gamma-distributed stochastic frontier model. J. Econom. 1990, 46, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldo, D.R.; Smith, L.W.; Cox, E.L.; Weinland, B.T.; Lucas, H.L., Jr. Logarithmic normal distribution for description of sieved forage materials. J. Dairy Sci. 1971, 54, 1465–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooray, K. Generalized gumbel distribution. J. Appl. Stat. 2010, 37, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atchison, J.; Shen, S.M. Logistic-normal distributions: Some properties and uses. Biometrika 1980, 67, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, J.D.; Asce, M.; Obeysekera, J.; Asce, M. Revisiting the Concepts of Return Period and Risk for Nonstationary Hydrologic Extreme Events. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2014, 19, 554–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).