Abstract

Identifying the dominant mechanisms of water and soil salinization in arid and semi-arid endorheic basins is fundamental for our understanding of basin-scale water–salt balance and supports water resources management. In many inland basins, mineral dissolution, evaporation, and transpiration govern salinization, but disentangling these processes remains difficult. Using the Barkol Basin in northwestern China as a representative endorheic system, we sampled waters and soils along a transect from the mountain front through alluvial fan springs and rivers to the terminal lake. We integrated δ18O–δ2H with hydrochemical analyses, employing deuterium excess (d-excess) to partition salinity sources and quantify contributions. The results showed that mineral dissolution predominated, contributing 65.8–81.8% of groundwater salinity in alluvial fan settings and ~99.7% in the terminal lake, whereas direct evapoconcentration was minor (springs and rivers ≤ 4%; lake ≤ 0.2%). Water chemistry types evolved from Ca-HCO3 in mountainous runoff, to Ca·Na-HCO3·SO4 in groundwater and groundwater-fed rivers, and finally to Na-SO4·Cl in the terminal lake. The soil profiles showed that groundwater flow and vadose-zone water–salt transport control spatial patterns: surface salinity rises from basin margins (<1 mg/g) to the lakeshore and is extremely high near the lake (23.85–244.77 mg/g). In spring discharge belts and downstream wetlands, the sustained evapotranspiration of groundwater-supported soil moisture drives surface salt accumulation, making lakeshores and wetlands into terminal sinks. The d-excess-based method can robustly separate the salinization processes despite its initial isotopic variability.

1. Introduction

Endorheic basins are widespread across arid and semi-arid regions. Their terminal lakes and wetlands respond sensitively to climate variability and human activities, and water–salt transport processes directly affect regional ecological security and the sustainable use of water resources [1,2]. Within such basins, salts accumulate because of catchment convergence, evapoconcentration, and mineral dissolution. Identifying which mechanism dominates in different hydrogeologic segments is therefore fundamental for understanding salinization patterns and designing effective control strategies [3,4,5]. In terminal lake wetlands, shallow groundwater-driven evapotranspiration and capillary rise often induce strong surface salinization, forming pronounced salt accumulation zones [6,7]. However, along the full source-to-sink continuum—from the mountain front, through rivers and spring discharge zones, to the terminal lake—it remains difficult to quantify the relative contributions of evapoconcentration and mineral dissolution to salinity increases [8]. This also makes it challenging to manage the salt budget at the basin scale.

Hydrogen and the oxygen-stable isotopes (δ18O, δ2H) of water are sensitive to phase changes, the effective tracers of water cycling pathways, and the origins of salinization. The Global or Local Meteoric Water Lines (GMWL/LMWL) provide references for diagnosing evaporative modification [9,10]. At the basin scale, however, evaporation cannot be robustly inferred from δ18O–δ2H relationships or from their correlation with total dissolved solids (TDSs) alone, because both are strongly affected by spatiotemporal variability in the initial isotopic composition [5,11]. Deuterium excess (d-excess), which integrates the information of non-equilibrium evaporation and moisture source, mitigates sensitivity to initial heterogeneity and responds more directly to evaporative processes [12]. Consequently, d-excess provides a useful basis for estimating the fraction of residual (post-evaporation) water and for separating evapoconcentration from non-fractionating salinity sources such as mineral dissolution [13,14]. In parallel, lake isotope mass-balance approaches have been widely applied to estimate lake surface evaporation fractions and residence times, underscoring the central role of evaporation in terminal lake water budgets [15,16].

Despite substantial global research on water–salt fluxes in endorheic systems, most studies emphasize water balance or salinity trends within single water bodies. Relatively few treat the sequence from mountainous runoff to terminal lake as an integrated water–salt continuum, and systematically quantify salt inputs, transport, and accumulation across segments [6]. Moreover, although evaporation and mineral dissolution are generally recognized as co-drivers of salinization, quantitative partitioning of their relative contributions at the basin scale remains limited. Many studies rely on qualitative assessments or end-member mixing and isotope mass balance for indirect inference, whereas direct quantification using d-excess remains scarce [17,18]. These gaps restrict our ability to diagnose dominant salinization mechanisms and to develop targeted regulation strategies in arid endorheic basins.

To address these gaps, we selected the Barkol Basin, a typical endorheic basin in northwestern China, and established observation points spanning the mountain front, the runoff reaches, the spring discharge belts, the wetlands, and the terminal lake. We integrated stable isotope and hydrochemical datasets to estimate evaporative fractions via a d-excess-based evaporation model and to quantitatively assess the contributions of evapoconcentration and mineral dissolution to salinity increases along the basin continuum.

2. Study Area and Data

2.1. Regional Setting

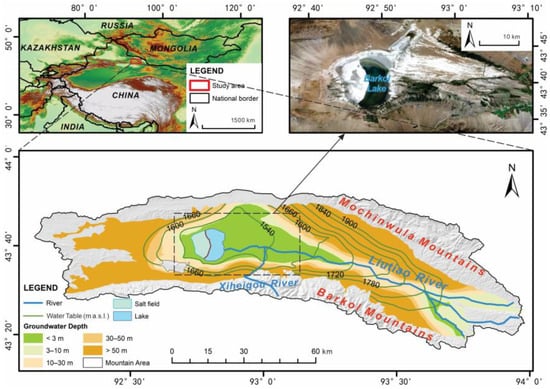

The Barkol Basin lies in the eastern segment of the Tien Shan Mountains, forming a fault-bounded endorheic depression surrounded by the Barkol and Mochinwula ranges (Figure 1) [19]. Basin elevations range from ~1500 to 2000 m, with an overall southeast-to-northwest topographic gradient. The total area is ~4515 km2. The climate is temperate continental arid, characterized by scarce precipitation and strong evaporation. The mean annual precipitation over the plains is 218 mm, with roughly 55% falling from June to August, whereas mean annual pan evaporation (E601) reaches 1027 mm. Mean annual air temperature in the plains is ~2 °C [20]. In the surrounding mountains, the snow season is long, and seasonal snow accounts for roughly 30% of annual precipitation, providing an important delayed water source to the basin.

Figure 1.

Location and overview of the study area.

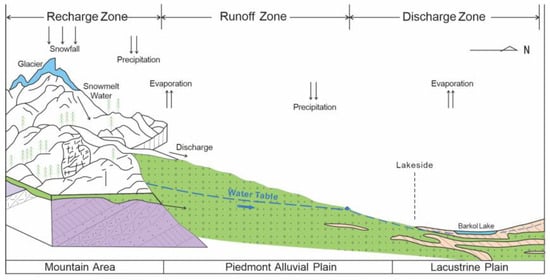

The rivers draining the basin have a combined annual runoff of ~1.70 × 108 m3 and form extensive alluvial fans at the mountain front. These fans constitute the primary recharge zones for groundwater via riverbed infiltration (Figure 2). Downstream, in the fine-grained plains and spring discharge belts, rising groundwater levels allow discharge as springs that reconstitute surface flow, forming a characteristic “river–groundwater–river” alternation. Barkol Lake, located at the terminal part of the basin, is a shallow, closed saline lake that functions as the ultimate water–salt sink. Over recent decades, the lake area has shrunk and now fluctuates between ~40 and 60 km2 [21]. A dike constructed in 1995 divides the lake into an eastern brine sector and a western mirabilite-extraction sector [22]. The lakebed is widely mantled by salt crusts, and the average water depth is <1 m.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of groundwater zoning and flow cycle in the Barkol Basin. In the recharge zone, precipitation occurs as snowfall in high elevation or in winter. Snowmelt water and direct precipitation recharge the river and form mountainous runoff, which is generally considered as the amount of water resources in the arid basin.

The geomorphology thus comprises mountain-front alluvial fans, fine-grained plains, and lacustrine plains around the lake. This setting provides a complete “mountain front–runoff reach–spring discharge belt–wetland–terminal lake” continuum that is well suited for investigating coupled water–salt processes in an arid endorheic system.

2.2. Samples Collection

Field sampling and subsequent laboratory analyses were carried out to obtain a spatially coherent dataset of water chemistry, stable isotopes, and soil salinity along the mountain–lake continuum. The main synoptic campaign was conducted in September 2024 so that surface water, groundwater, and soil data were temporally consistent. To better constrain terminal conditions, an additional lake water sample (sample W14) was collected in August 2025. This supplementary sample does not influence the interpretation of the basin-scale salinization mechanisms because Barkol Lake is shallow but well mixed, and has a large solute storage capacity, relative to its short-term variability.

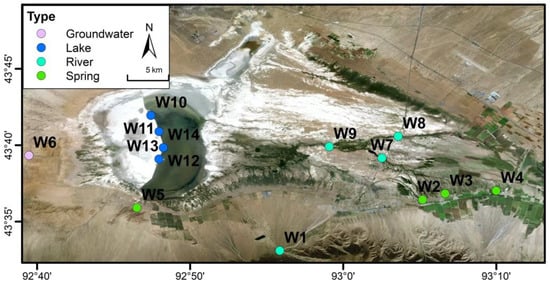

Along the hydrological continuum from the Xiheigou headwaters to Barkol Lake, 14 representative water sites (W1–W14) were selected, including mountain-front runoff, spring, groundwater, river, and lake water (Figure 3). At each site, water samples were collected using pre-rinsed polyethylene bottles. Field measurements included pH, temperature, electrical conductivity (EC) (using a multi-parameter device (HQ40d, HACH, Loveland, CA, USA)) and alkalinity, as assessed using titration (for the lake water samples, the alkalinity was not measured).

Figure 3.

Distribution of representative water sampling sites in the Barkol Basin.

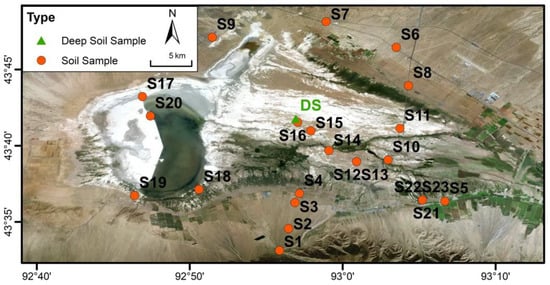

To investigate the spatial distribution of soil salinity, we established 23 soil profiles across major geomorphic units (alluvial fans, fine-grained plains, and lacustrine plains) and land-use types (Figure 4). In addition, three deep profiles (DSs) were excavated in the wetland area (depth 1.7 m; horizontal spacing of 2 m) (Figure 4), from which 51 samples were collected at 0.1 m intervals.

Figure 4.

Distribution of soil sampling profiles in the Barkol Basin.

The spatial distribution of water-sampling sites and soil profiles along the mountain–lake transect is shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4. Together, the sampling design captures both the longitudinal evolution of hydrochemistry and isotopes along the flow path and the two-dimensional pattern of soil salinization in the discharge-dominated lowlands.

3. Methods

3.1. Water and Soil Sample Analyses

All water samples (W1–W13) were analyzed to determine their basic physicochemical parameters and major ion concentrations. An additional lake water sample (W14), collected in August 2025, was only analyzed for stable isotopes (δ2H and δ18O) and therefore has no major-ion data. In the laboratory, a cations (Ca2+, Mg2+, Na+, K+) analysis was performed via inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES, iCAP PRO, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), with a detection limit of 0.05 mg/L; anions (Cl−, SO42−, NO3−) were measured with an ICS1100 Ion Chromatograph (Dionex Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) with detection limit of 0.05 mg/L at the Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences. The charge balance errors for the river, spring, and groundwater samples ranged from −2.4% to 3.3%. The total dissolved solids (TDSs) were calculated by sum all ions (note: half of HCO3 contribute to TDS, since half of the HCO3 would escape when the sample is evaporated to dryness). For sample W14, the field measurement for TDS was used.

The stable isotopes of hydrogen and oxygen in low-salinity water samples (TDS < 5 g/L) were analyzed at the Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, using a Picarro L1102-i isotopic water analyzer (Picarro, Santa Clara, CA, USA). High-salinity samples (TDS > 50 g/L) were analyzed at the Qinghai Institute of Salt Lakes, Chinese Academy of Sciences, by isotope ratio mass spectrometry (MAT253, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) via chromium reduction for hydrogen isotopes and CO2–H2O equilibration for oxygen isotopes. Results are reported as δ2H and δ18O (δ = (Rsample/Rstandard − 1) ×1000‰) using the Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (VSMOW) as standard. The analytical precision is ±1‰ for δ2H and ±0.1‰ for δ18O.

All soil samples were air-dried and then extracted at a water-soil ratio of 5:1 (50 mL deionized water to 10 g air-dried soil). After shaking and centrifugation, the TDS (mg/L) of the supernatant was determined using a multi-parameter device (HQ40d, HACH, Loveland, CA, USA) and used to calculate soil salt content using the following formula:

where Vextract = 0.05 L and msoil = 10 g. This 1:5 soil–water extract approach for assessing soil salinity from EC or TDS measurements has been widely used in previous studies and is recommended in the international guidelines [23,24,25].

3.2. d-Excess-Based Evaporation Model and Salinity Mass Balance

At the catchment scale, traditional methods that depend on the relationship between δ18O or δ2H and salinity (e.g., TDS) are limited by spatial and temporal variations in the initial isotopic composition of water [5]. In contrast, deuterium excess (d-excess) acts as a composite parameter. Once the initial d-excess of precipitation or mountain-front outflow in a basin is determined, it becomes a more reliable indicator for tracking water evaporation, regardless of changes in the initial δ18O or δ2H values [12,13].

This study uses the d-excess-based evaporation model proposed by Huang and Pang to estimate the residual water fraction (0 < f ≤ 1) of an evaporating water body. The model links d-excess (d) to the residual water fraction (f) under steady-state evaporation conditions. Its derivation is based on the Rayleigh distillation principle, with a core relationship that can be expressed by [13]:

In this model, and represent the stable isotope values of the initial water (any water mass sharing the same initial d-excess). αv−l denotes the vapor–liquid fractionation factor, which is the inverse of the liquid–vapor fractionation factor αl−v (i.e., αv−l = 1/αl−v).

The liquid–vapor fractionation factor (αl−v) is determined by the equilibrium fractionation factor (εl−v) and the kinetic fractionation factor (Δεbl−v) [18]:

The equilibrium fractionation factor (εl−v) is a function of temperature (T, in Kelvin), given by the following empirical formulae [26]:

The kinetic fractionation factor (Δεbl−v) is calculated using the equations provided by Gonfiantini [27]:

where h is atmospheric relative humidity. Given the evaporation conditions (T and h), the value of f can be determined by solving the equation.

Since neither plant transpiration nor mineral dissolution fractionates hydrogen and oxygen-stable isotopes or alters the d-excess of a water body, their combined contribution to salinization is grouped as mineral dissolution in the model [13,28]. After determining f, the relative contributions of evapoconcentration and mineral dissolution to the increase in water salinity are quantified. In this study, TDS is used as a proxy for salinity (S). The model assumes that salts are added linearly during mineral dissolution and that this process induces no isotopic fractionation. Based on salinity mass balance, the proportional contributions of different processes to the final salinity are calculated as follows [13]:

where Cinit, Cevap, and Cleavap represent the relative contributions of the initial water, evapoconcentration, and mineral dissolution (including transpiration) to the current salinity, respectively.

4. Results

4.1. Longitudinal Evolution of Hydrochemistry

Sampling along the Barkol Basin continuum—from the Xiheigou headwaters through the alluvial fan springs and Liutiao River to Barkol Lake—reveals a pronounced increase in salinity along the flow path. TDSs rise by several orders of magnitude from the mountain front to the terminal lake. At the Xiheigou headwater (W1), TDSs are at their lowest (99 mg/L), representing a low-mineralization end-member. Spring waters and shallow groundwater on the alluvial fans (W2–W6) exhibit elevated TDS values of 295–592 mg/L. In the Liutiao River (W7–W9), TDSs range from 353 to 429 mg/L, comparable to or slightly lower than the more mineralized springs and groundwater along the runoff reach. The terminal Barkol Lake (W10–W13, W14) shows a sharp rise in TDSs (69,577–135,222 mg/L), indicating extreme salinity in the final sink.

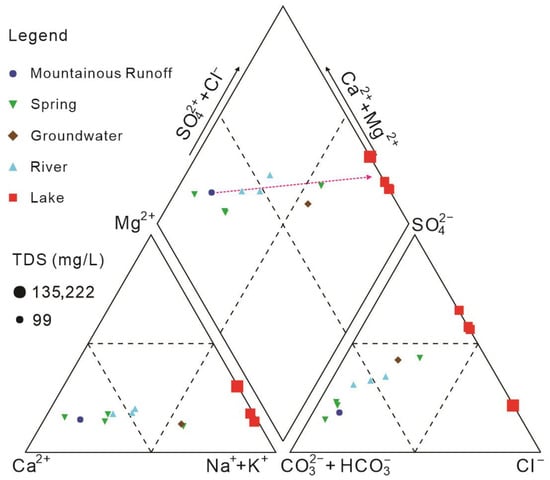

Major-ion compositions evolve coherently along the mountain–lake continuum (Table 1; Figure 5). At the mountain front (W1), water is dominated by Ca2+ and HCO3−, forming a Ca–HCO3-type low-salinity water typical of fresh mountain-front runoff. In the alluvial fan spring belt (W2–W5) and fan-edge groundwater (W6), Ca2+ and Mg2+ remain dominant cations, whereas SO42− increases relative to HCO3−, producing Ca·Na–HCO3·SO4-type compositions on the hydrochemical trilinear diagram. In the middle and lower reaches (Liutiao River, W7–W9), Ca2+ and Mg2+ still dominate, but Na+ and SO42− becomes more important, reflecting a progressive water–rock interaction along the flow path between the mountain-front and terminal lake end-members. In Barkol Lake (W10–W13, W14), the major-ion composition is characterized by high Na+, SO42−, and Cl−, corresponding to Na–SO4·Cl-type brines. Overall, the longitudinal pattern shows a transition from Ca–HCO3-type low-salinity water at the mountain front, through Ca·Na–HCO3·SO4-type springs and rivers, to Na–SO4·Cl-type terminal lake brines.

Table 1.

Major ion chemistry of water samples along the mountain–lake continuum in the Barkol Basin. W14 was only analyzed for isotopes and TDS; thus, no major-ion data are listed. (NM: not measured; UD = under detection.)

Figure 5.

Piper diagram of major ion compositions in water samples from the Barkol Basin. The dash line indicated the evolution of water chemical composition from mountainous runoff to terminal lake.

4.2. Stable Isotopes and Quantitative Identification of Salinization Mechanisms

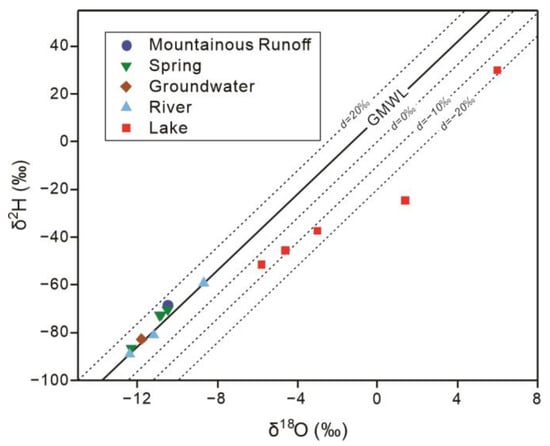

Building on the longitudinal hydrochemical trends described above, stable isotopes of hydrogen and oxygen further constrain the evolution of waters along the mountain–lake continuum and provide the basis for quantitatively partitioning salinization mechanisms. To evaluate evaporative effects on different water bodies, δ2H–δ18O values are compared with the Global Meteoric Water Line (δ2H = 8δ18O + 10) [9] (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Relationship between δ2H and δ18O for water samples in the Barkol Basin relative to the Global Meteoric Water Line (GMWL).

The river water at the Xiheigou headwater (W1) and at the springs in the alluvial fan belt (W2–W5) plot close to the GMWL, with only slight deviations. This indicates that these waters largely preserve the initial meteoric or mountain-front recharge signatures and have experienced only limited evaporative enrichment. In contrast, the Liutiao River samples (W7–W9) show moderate displacement away from the meteoric line, whereas the Barkol Lake waters (W10–W13) display a pronounced shift along a lower-slope evaporation trend, consistent with strong evaporative modification in the terminal lake.

The d-excess shows a clear downstream decrease (Table 2). At the Xiheigou headwater (W1), river water has the highest d-excess (+15.5‰), representing the initial, low-evaporation end-member. Springs in the alluvial fan belt (W2–W5) show slightly lower but still high d-excess values of +13.6‰ to +14.5‰, remaining close to the mountain-front runoff and indicating limited evaporative enrichment. In the Liutiao River (W7–W9), d-excess drops markedly to +8.5‰ to +9.9‰, reflecting moderate evaporation acting on the surface waters. The Barkol Lake waters (W10–W14) display the lowest and negative d-excess values (−36.0‰ to −5.5‰), consistent with strong evaporative modification in the terminal lake.

Table 2.

Quantitative assessment of the contribution rates of different salinization mechanisms.

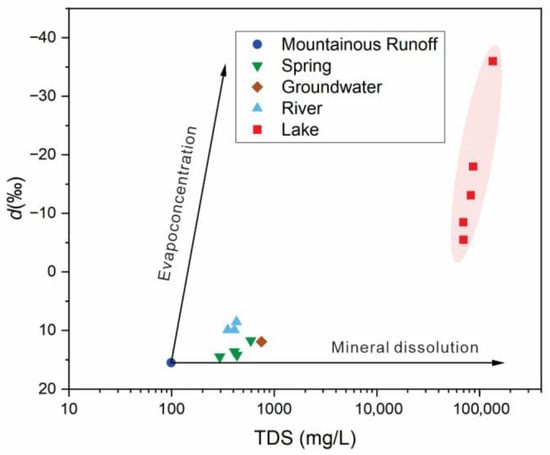

In arid inland basins, mountain-front outflow effectively represents the basin’s total water input. Using the Xiheigou River (TDS = 99 mg/L, d-excess = +15.5‰) as the initial end-member, the d-excess-based evaporation model was applied to partition the contributions of evapoconcentration versus mineral dissolution across water bodies; the summarized results are presented in Table 2 and Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Quantitative identification of salinization mechanisms in different water bodies based on the d-excess model.

The calculations reveal fundamental contrasts among hydrogeologic units. In alluvial fan springs, salinization is dominated by mineral dissolution, contributing 65.8–81.8%, whereas evapoconcentration is minimal (0.7–1.5%). In the Liutiao River, mineral dissolution contributes 68.1–73.2%, with a modest rise in evapoconcentration (3.3–3.8%) due to surface flow exposure; however, the direct evaporative contribution remains limited. In Barkol Lake, the mechanism shifts firmly toward mineral dissolution, which accounts for ~99.7% of salinity, while the direct evapoconcentration contribution is negligible (<0.2%).

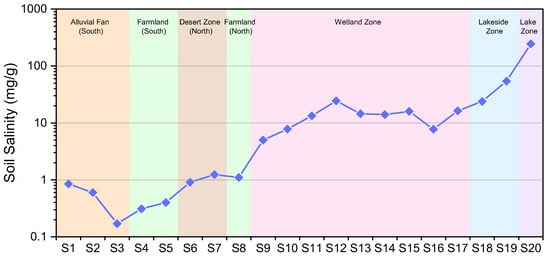

4.3. Spatial Distribution Patterns of Soil Salinity

Given that downstream wetlands and the terminal lake are the primary sinks of dissolved salts, soil salinity patterns provide an integrated record of water–salt interactions in the discharge area. Surface soil salinity (≤5 cm) increases systematically from the basin margins toward the center of Barkol Lake (Table 3; Figure 8). The southern mountain-front alluvial fans and croplands have the lowest surface salinities, generally <1.0 mg/g. Salinity rises slightly in the fine-grained plains, where surface soils reach 1.0–5.01 mg/g. The highest surface salinities occur around the lake margins, where soils reach 23.85–244.77 mg/g, forming pronounced salt accumulation zones around the terminal lake.

Table 3.

Soil salinity of representative profiles in the Barkol Basin.

Figure 8.

Spatial distribution of surface soil salinity (≤5 cm depth).

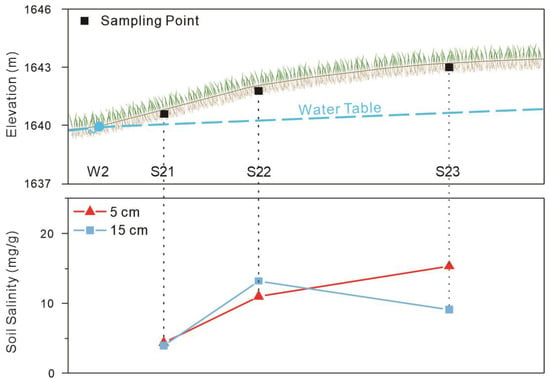

Within the spring discharge belt, soil salinity exhibits marked spatial heterogeneity along short transects (Figure 9). Local salinity maxima often occur a short distance upgradient from spring vents, rather than immediately at the spring outlets. For example, at profile S23, surface soil salinity peaks at 15.30 mg/g several meters upgradient of the springs, exceeding the values measured immediately adjacent to the vents (<5 mg/g). This pattern indicates that the interaction between capillary rise and evapotranspiration redistributes salts laterally around discharge points.

Figure 9.

Variation of soil salinity in the spring discharge zone.

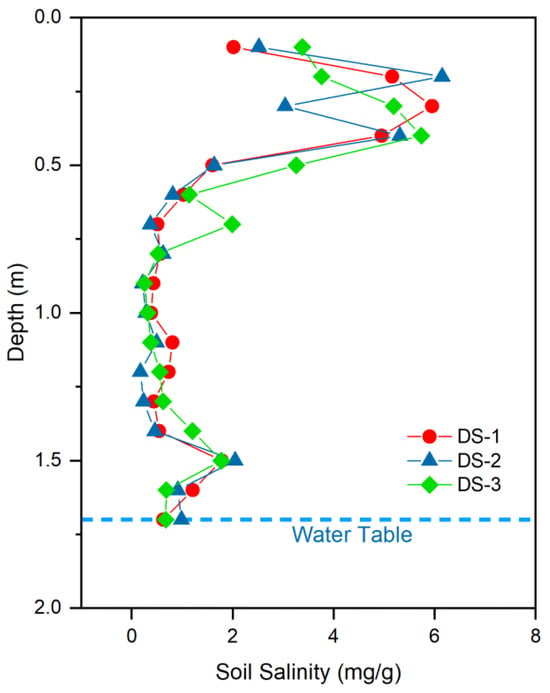

Vertically, the wetland soil profiles (DS-1, DS-2, DS-3) show distinct salinity stratification in the discharge area (Table 4; Figure 10). In the deepest parts of the profiles (below ~50 cm), soil salinity remains relatively low and stable (0.17–1.99 mg/g). In the upper part of the profiles, salinity is higher, with a pronounced enrichment zone at 20–40 cm depth where values reach up to 6.15 mg/g. Above and below this interval, soil salinity decreases toward both the soil surface and deeper layers. The vertical distributions indicate near-surface salt accumulation controlled by shallow groundwater, capillary rise, and evapotranspiration, superimposed on relatively low-salinity deeper layers that are less affected by evaporative concentration.

Table 4.

Soil salinity of deep profiles (DS-1 to DS-3) in the wetland area.

Figure 10.

Vertical distribution of soil salinity in the wetland profile.

5. Discussion

The results above document three key features of the Barkol Basin: (i) a strong longitudinal increase in TDS and systematic evolution of major-ion compositions from Ca–HCO3-type mountain-front water to Na–SO4·Cl-type terminal lake brine; (ii) a progressive decrease in d-excess along the mountain-front–lake continuum, which, when interpreted using a d-excess-based evaporation model, indicates that the non-fractionating processes grouped as mineral dissolution overwhelmingly control salinity increases, whereas direct evapoconcentration plays a comparatively minor role; and (iii) pronounced spatial gradients in soil salinity, with salt accumulation in lake margin and wetland soils that are strongly influenced by shallow groundwater and evaporative processes. In this section, we discuss the applicability and limitations of the d-excess approach, the dominant salinization mechanisms in the Barkol Basin compared with other arid endorheic basins, and the implications for water–salt management.

5.1. Applicability, Advantages, and Uncertainties of the d-Excess Model

The evaporation model based on d-excess reduces reliance on the absolute δ18O and δ2H values of source waters. At the basin scale, as long as the initial d-excess is similar across water bodies, the model robustly constrains evaporation fractions, thereby overcoming biases caused by spatiotemporal variability in initial isotope compositions for δ18O and δ2H.

In the study area, mountain-front runoff shows d-excess ≈ +15.5‰, markedly higher than the global mean of precipitation (+10‰) [12], mainly due to regional moisture conditions [29]. Consistent with other Central Asian records, Tien Shan ice-core data indicate annual d-excess variations of ~15–20‰ [30]. Spring waters have d-excess between +13.6‰ and +14.5‰, close to the mountain-front runoff, which supports our choice of an initial d-excess and indicates that the approach is appropriate for endorheic basins such as the Barkol Basin.

Nevertheless, several uncertainties remain. First, the choice of initial d-excess: although spring data support its representativeness, precipitation d-excess is affected by moisture sources and sub-cloud evaporation, implying potential spatiotemporal variability; using a fixed initial d-excess may thus introduce some bias. Second, the high-salinity effect: Barkol Lake exhibits extremely high TDS. Elevated ionic strength can lower the saturation vapor pressure at the solution surface (the ‘salt effect,’ effectively reducing ambient humidity) and may influence kinetic fractionation coefficients [31]. Finally, parameterization of model inputs (e.g., kinetic fractionation, temperature, and humidity at the evaporation interface) introduces additional uncertainty.

5.2. Causes for the Dominance of Mineral Dissolution

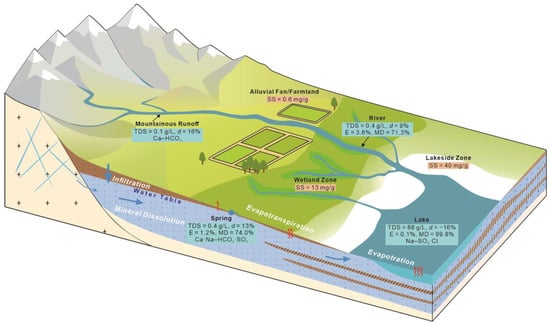

Groundwater chemistry in the Barkol Basin is dominated by mineral dissolution, owing to ample solute supply and hydrogeological flow paths. Solute concentrations in mountain-front runoff are generally low, controlled by precipitation chemistry and limited weathering. Along long flow paths and prolonged residence times within alluvial fans and fine-textured plains, water–rock interaction intensifies, enabling sustained increases in TDS without substantial water loss. This dissolution-dominated salinization mechanism has also been documented in other large arid endorheic basins, such as the Qaidam Basin [32]. In the terminal lake zone, intense evaporation primarily removes water and concentrates existing solutes rather than adding new ones; continuous external solute inputs via groundwater discharge and surface inflow lead to long-term accumulation in the lake (Figure 11)—a typical pattern in closed basins [33,34].

Figure 11.

Conceptual model of salinization in the Barkol Basin. Abbreviations: SS = soil salinity; E = evaporation contribution; MD = mineral dissolution contribution.

Although the direct contribution of evaporation to salinity budgets is small, its indirect influence via concentration is important. Evapoconcentration can (i) drive supersaturation and promote mineral precipitation, and (ii) maintain high-ionic-strength conditions that continually affect dissolution–precipitation equilibria [25].

The Barkol Basin typifies a mineral dissolution–accumulation salinization mode. This contrasts with shallow saline lakes (e.g., the Dead Sea), where intense evaporation and seasonal density stratification can trigger rapid halite precipitation; in Barkol, salinity is closely linked to catchment-scale mineral dissolution and groundwater discharge [35]. Relative to much larger systems such as Qaidam, Barkol’s smaller size and more concentrated tectonic framework and salt sources make the mineral dissolution signal easier to identify and quantify in isotope–hydrochemical space [32]. Compared with Lake Urmia, Barkol more clearly records the natural coupling between solute inputs and climatic evaporation, whereas Urmia is more strongly influenced by human water use [33].

5.3. Soil-Salinization Processes and Groundwater System Response

High-salinity zones constitute a dynamic belt driven by groundwater–vadose zone coupling. When the water-table depth lies within the sensitivity window for capillary rise and evapotranspiration, dissolved salts are transported upward and accumulate near the surface, forming a typical surface accumulation vertical pattern [36,37]. On the upgradient side of groundwater-discharge zones, the coexistence of suitable water-table depths, high evapotranspiration, and well-connected capillary pathways favors the development of salinity peaks [6].

This phenomenon is susceptible to vadose-zone texture and water-table variations: even small changes in depth, climate, or vegetation can shift the position of salinity maxima. Management should therefore intervene not only in the terminal wetlands and lake, where salts ultimately accumulate, but also in the upstream area, along the transport pathways. Recommended measures include the following: setting texture-dependent groundwater depth targets and strengthening dynamic monitoring; in shallow water table and spring belt areas, installing shallow drains or subsurface pipes to remove saline water early and reduce solute delivery to the lake; applying surface mulching or straw incorporation to suppress evaporation and slow near-surface accumulation [38,39,40]. Fine-textured, high-salinity zones should be prioritized for water-table control and surface cover. Pilot water–salt regulation projects should coordinate irrigation and drainage, particularly avoiding irrigation-induced rises of the water table to salinization-prone depths during spring–summer.

6. Conclusions

This study conceptualizes the sequence from mountainous runoff to the terminal lake of the arid Barkol Basin as an integrated water–salt continuum. By combining a d-excess-based evaporation model with a salinity mass balance, we quantify the relative roles of evapoconcentration and mineral dissolution along this continuum. From the mountain front to the terminal lake, TDS increases by several orders of magnitude and major-ion compositions evolve from Ca–HCO3-type mountain-front water, through Ca·Na–HCO3·SO4-type springs and rivers, to Na–SO4·Cl-type terminal brine; meanwhile, d-excess decreases systematically from +15.5‰ at the mountain front to strongly negative values in Barkol Lake. The model results indicate that non-fractionating processes grouped as mineral dissolution (including transpiration) account for 65.8–81.8% of salinity in alluvial fan springs and shallow groundwater, 68.1–73.2% in the Liutiao River, and ~99.7% in the terminal lake. In contrast, direct evapoconcentration contributes only up to 4.0% in springs and rivers and <0.2% in the lake. The Barkol Basin, therefore, typifies a mineral dissolution–accumulation salinization mode at the basin scale, rather than an evaporation-dominated mode.

Soil salinity patterns in the discharge area are consistent with this interpretation. Surface soil salinity generally increases from <1.0 mg/g on alluvial fans and croplands to 1.0–5.01 mg/g on fine-grained plains and 23.85–244.77 mg/g around the lake margins, forming a high-salinity belt near the terminal lake. Deep wetland profiles show relatively low salinity at depth, and a pronounced enrichment zone at intermediate depths (20–40 cm); local maxima in salinity occur in the slight upgradient of springs, reflecting the combined control of shallow groundwater, capillary rise, and evapotranspiration on near-surface salt storage. Together, these results demonstrate that, in the Barkol Basin and similar arid endorheic basins, salinization is governed mainly by mineral dissolution, groundwater circulation, and vadose-zone processes, implying that effective salinity management must focus on regulating groundwater flow paths, water-table depths, and salt mobilization along transport pathways, rather than solely reducing lake surface evaporation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.W. and T.H.; methodology, T.H.; validation, Y.Z. and C.Z.; formal analysis, Y.Z., C.Z. and T.H.; investigation, C.Z., Y.Z., B.X., R.L., X.W. and J.Z.; data curation, Z.W., Y.Z. and C.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.W. and T.H.; writing—review and editing, T.H.; funding acquisition, T.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42172277), the Investigation project of the Barkol wetland water–salt balance, and the IAEA Project (RAS7040/7043).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank Xusheng Wang, Ying Li, Yueqing Xie, and Fang Zhang for help in field sampling.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Wang, J.; Song, C.; Reager, J.T.; Yao, F.; Famiglietti, J.S.; Sheng, Y.; MacDonald, G.M.; Brun, F.; Schmied, H.M.; Marston, R.A.; et al. Recent Global Decline in Endorheic Basin Water Storages. Nat. Geosci. 2018, 11, 926–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, J.P.; King, S.L.; Silverman, N.L.; Collins, D.P.; Carrera-Gonzalez, E.M.; Lafón-Terrazas, A.; Moore, J.N. Climate and Human Water Use Diminish Wetland Networks Supporting Continental Waterbird Migration. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 2042–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, R.J. Mechanisms Controlling World Water Chemistry. Science 1970, 170, 1088–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yechieli, Y.; Wood, W.W. Hydrogeologic Processes in Saline Systems: Playas, Sabkhas, and Saline Lakes. Earth Sci. Rev. 2002, 58, 343–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, A.; Li, W.; Liang, Z. A method to determine contribution of Lixiviation and evaporation to groundwater salinization in arid river basins using TDS and δ18O. Hydrogeol. Eng. Geol. 2000, 27, 4–6. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokri, N.; Hassani, A.; Sahimi, M. Multi-Scale Soil Salinization Dynamics from Global to Pore Scale: A Review. Rev. Geophys. 2024, 62, e2023RG000804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhao, W.; Wen, Z.; Yang, Y.; Chang, X.; Yang, Q.; Meng, Y.; Liu, C. Mechanisms and Feedbacks for Evapotranspiration-Induced Salt Accumulation and Precipitation in an Arid Wetland of China. J. Hydrol. 2019, 568, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yapiyev, V.; Wade, A.J.; Shahgedanova, M.; Saidaliyeva, Z.; Madibekov, A.; Severskiy, I. The Hydrochemistry and Water Quality of Glacierized Catchments in Central Asia: A Review of the Current Status and Anticipated Change. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2021, 38, 100960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, H. Isotopic Variations in Meteoric Waters. Science 1961, 133, 1702–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gat, J.R. Oxygen and Hydrogen Isotopes in the Hydrologic Cycle. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 1996, 24, 225–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishan, G.; Prasad, G.; Anjali; Kumar, C.P.; Patidar, N.; Yadav, B.K.; Kansal, M.L.; Singh, S.; Sharma, L.M.; Bradley, A.; et al. Identifying the Seasonal Variability in Source of Groundwater Salinization Using Deuterium Excess- a Case Study from Mewat, Haryana, India. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2020, 31, 100724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dansgaard, W. Stable Isotopes in Precipitation. Tellus 1964, 16, 436–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Pang, Z. The Role of Deuterium Excess in Determining the Water Salinisation Mechanism: A Case Study of the Arid Tarim River Basin, NW China. Appl. Geochem. 2012, 27, 2382–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T. Comment on “Tracking Nitrate and Sulfate Sources in Groundwater of an Urbanized Valley Using a Multi-Tracer Approach Combined with a Bayesian Isotope Mixing Model by Torres-Martínez et al. [Water Research 182 (2020) 115962].”. Water Res. 2025, 276, 123271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J.J.; Birks, S.J.; Yi, Y. Stable Isotope Mass Balance of Lakes: A Contemporary Perspective. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2016, 131, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vystavna, Y.; Harjung, A.; Monteiro, L.R.; Matiatos, I.; Wassenaar, L.I. Stable Isotopes in Global Lakes Integrate Catchment and Climatic Controls on Evaporation. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 7224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosaffa, M.; Nazif, S.; Amirhosseini, Y.K.; Balderer, W.; Meiman, H.M. An Investigation of the Source of Salinity in Groundwater Using Stable Isotope Tracers and GIS: A Case Study of the Urmia Lake Basin, Iran. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 12, 100513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonfiantini, R.; Wassenaar, L.I.; Araguas-Araguas, L.; Aggarwal, P.K. A Unified Craig-Gordon Isotope Model of Stable Hydrogen and Oxygen Isotope Fractionation during Fresh or Saltwater Evaporation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2018, 235, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, C.-B.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Tao, S.; Dong, W.; Li, H.; Jin, M.; Wang, Z. A High-Resolution Record of Holocene Environmental and Climatic Changes from Lake Balikun (Xinjiang, China): Implications for Central Asia. Holocene 2012, 22, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Chen, Y.; Shen, Y.; Li, X.; Xu, J. Spatial and temporal trends of climate change in Xinjiang, China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2011, 21, 1007–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Miao, Y.; Fang, Y.; Li, Y.; Lei, Y.; Chen, X.; Dong, W.; An, C. Investigation of Factors Affecting Surface Pollen Assemblages in the Balikun Basin, Central Asia: Implications for Palaeoenvironmental Reconstructions. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 123, 107332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Bao, A.; Zhang, J.; Bai, J. Temporal variation in the area of Barkol Lake, Xinjiang, during 1995–2020 and its attribution. Arid Zone Res. 2021, 38, 1514–1523. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corwin, D.L.; Yemoto, K. Salinity: Electrical Conductivity and Total Dissolved Solids. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2020, 84, 1442–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; DeSutter, T.; Prunty, L.; Hopkins, D.; Jia, X.; Wysocki, D.A. Evaluation of 1:5 Soil to Water Extract Electrical Conductivity Methods. Geoderma 2012, 185–186, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.C.; de Souza, E.R.; de Melo, H.F.; Oliveira Pinto, J.G.; de Andrade Rego Junior, F.E.; de Souza Júnior, V.S.; Adriano Marques, F.; do Santos, M.A.; Schaffer, B.; Raj Gheyi, H. Comparison of Solution Extraction Methods for Estimating Electrical Conductivity in Soils with Contrasting Mineralogical Assemblages and Textures. Catena 2022, 218, 106581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majoube, M. Fractionnement En Oxygène 18 et En Deutérium Entre l’eau et Sa Vapeur. J. Chim. Phys. 1971, 68, 1423–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonfiantini, R. Environmental Isotopes in Lake Studies. In Handbook of Environmental Isotope Geochemistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1986; pp. 113–168. [Google Scholar]

- Stout, G.E. Isotope Techniques in the Hydrologic Cycle, 1st ed.; American Geophysical Union (AGU): Washington, DC, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, Z.; Kong, Y.; Froehlich, K.; Huang, T.; Yuan, L.; Li, Z.; Wang, F. Processes Affecting Isotopes in Precipitation of an Arid Region. Tellus 2011, 63, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreutz, K.J.; Wake, C.P.; Aizen, V.B.; Cecil, L.D.; Synal, H.-A. Seasonal Deuterium Excess in a Tien Shan Ice Core: Influence of Moisture Transport and Recycling in Central Asia. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2003, 30, 1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, C.; Herwartz, D.; Dorador, C.; Staubwasser, M. Triple Oxygen Isotope Systematics of Evaporation and Mixing Processes in a Dynamic Desert Lake System. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 25, 1211–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Shao, J.; Frape, S.K.; Cui, Y.; Dang, X.; Wang, S.; Ji, Y. Groundwater Origin, Flow Regime and Geochemical Evolution in Arid Endorheic Watersheds: A Case Study from the Qaidam Basin, Northwestern China. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 22, 4381–4400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurtsbaugh, W.A.; Miller, C.; Null, S.E.; DeRose, R.J.; Wilcock, P.; Hahnenberger, M.; Howe, F.; Moore, J. Decline of the World’s Saline Lakes. Nat. Geosci. 2017, 10, 816–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Pang, Z. Changes in Groundwater Induced by Water Diversion in the Lower Tarim River, Xinjiang Uygur, NW China: Evidence from Environmental Isotopes and Water Chemistry. J. Hydrol. 2010, 387, 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilberman, T.; Gavrieli, I.; Yechieli, Y.; Gertman, I.; Katz, A. Constraints on Evaporation and Dilution of Terminal, Hypersaline Lakes under Negative Water Balance: The Dead Sea, Israel. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2017, 217, 384–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusefi, A.; Farrokhian Firouzi, A.; Aminzadeh, M. The Effects of Shallow Saline Groundwater on Evaporation, Soil Moisture, and Temperature Distribution in the Presence of Straw Mulch. Hydrol. Res. 2020, 51, 720–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelsoud, H.M.; Habib, A.; Engel, B.; Hashem, A.A.; El-Hassan, W.A.; Govind, A.; Elnashar, A.; Eid, M.; Kheir, A.M.S. The Combined Impact of Shallow Groundwater and Soil Salinity on Evapotranspiration Using Remote Sensing in an Agricultural Alluvial Setting. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2023, 47, 101372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagage, M.; Abdulaziz, A.M.; Elbeih, S.F.; Hewaidy, A.G.A. Monitoring Soil Salinization and Waterlogging in the Northeastern Nile Delta Linked to Shallow Saline Groundwater and Irrigation Water Quality. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Ben-Gal, A.; Scudiero, E.; Kisekka, I.; Rengasamy, P.; Yao, R. Soil and Water Management to Prevent Salinization under Changing Climate Conditions. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 110002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarolli, P.; Luo, J.; Park, E.; Barcaccia, G.; Masin, R. Soil Salinization in Agriculture: Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies Combining Nature-Based Solutions and Bioengineering. iScience 2024, 27, 108830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).