A Comparative Study of the Adsorption of Industrial Anionic Dyes with Bone Char and Activated Carbon Cloth

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Adsorbents

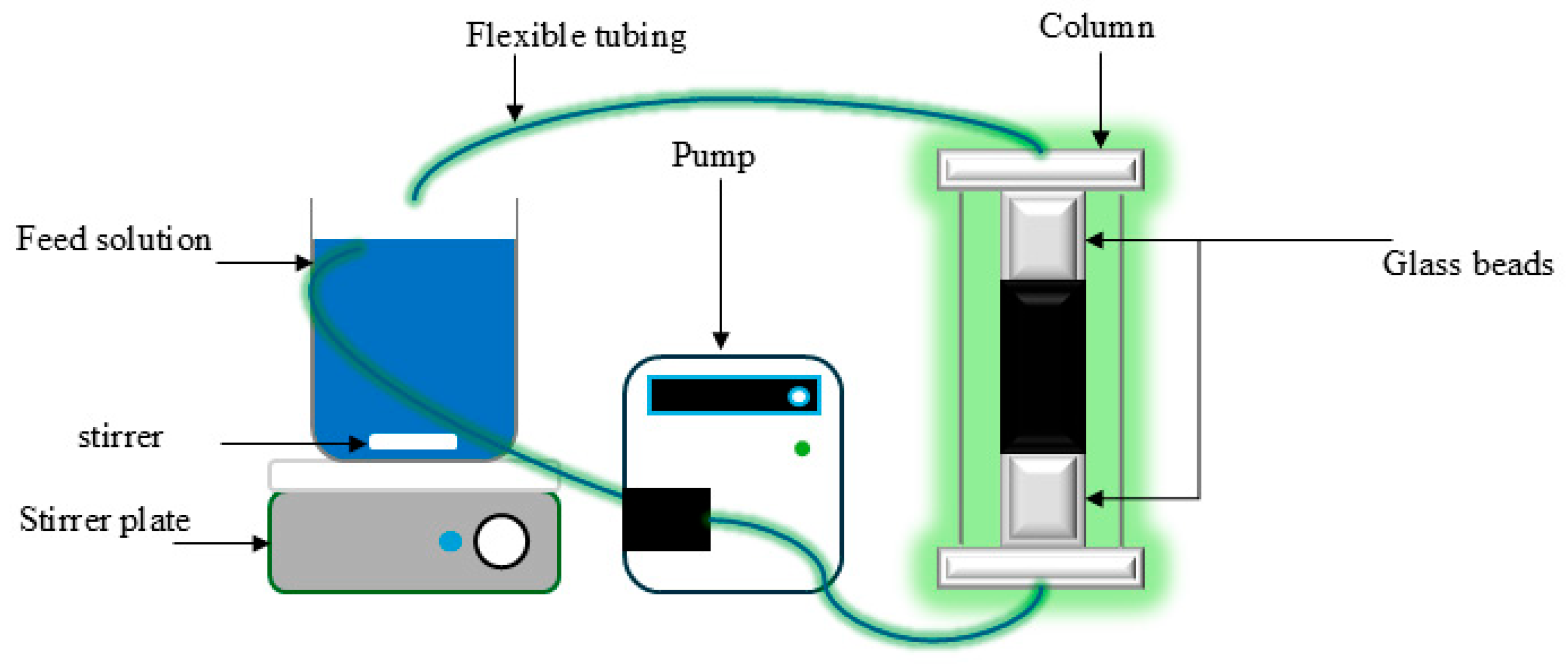

2.3. Experimental System

2.4. Mathematical Modeling of Equilibrium and Adsorption Rate

2.4.1. Equilibrium Adsorption

2.4.2. Adsorption Rate on BC

2.4.3. Adsorption Rate on ACC

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physicochemical Characteristics of BC

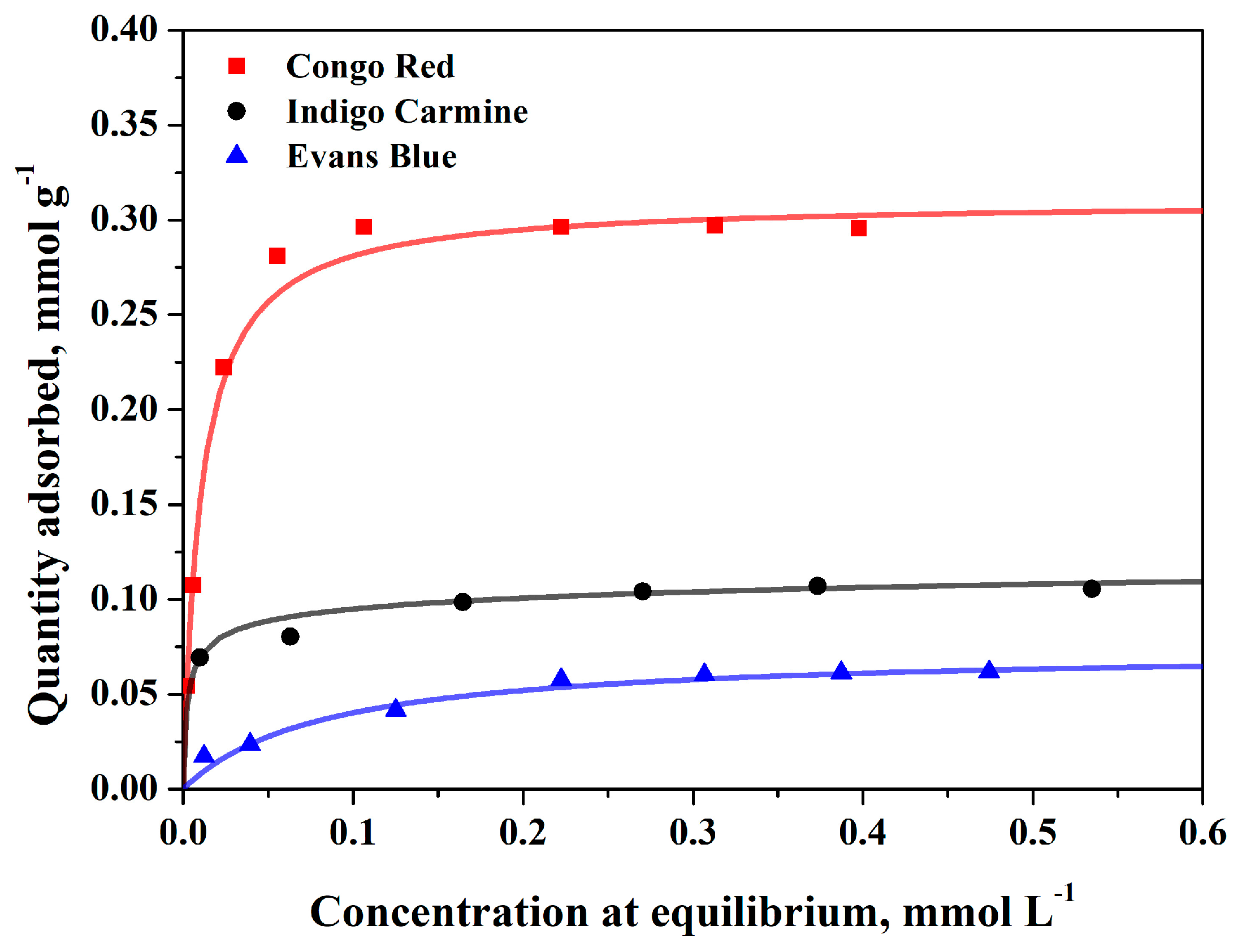

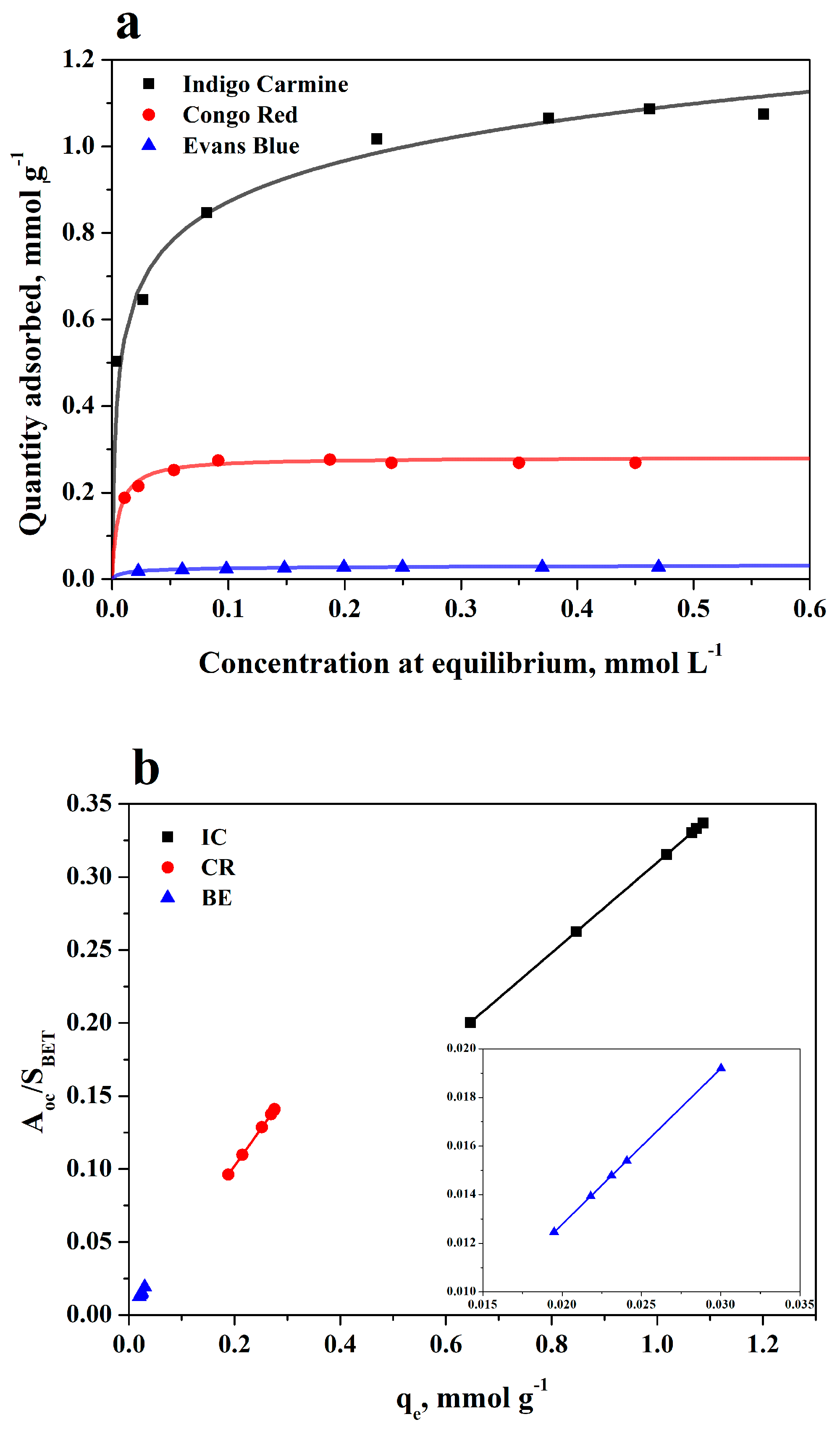

3.2. Adsorption Equilibrium on BC

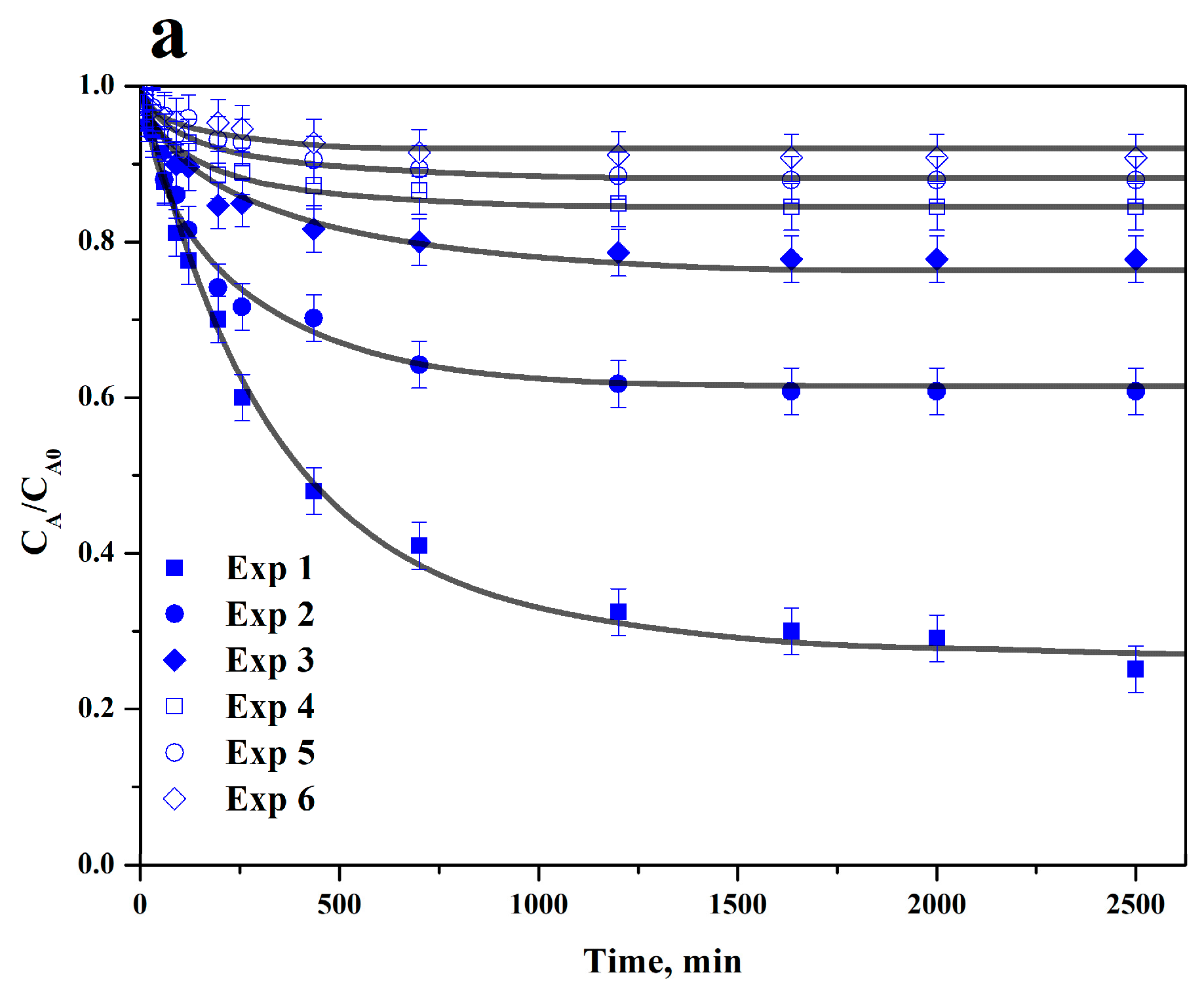

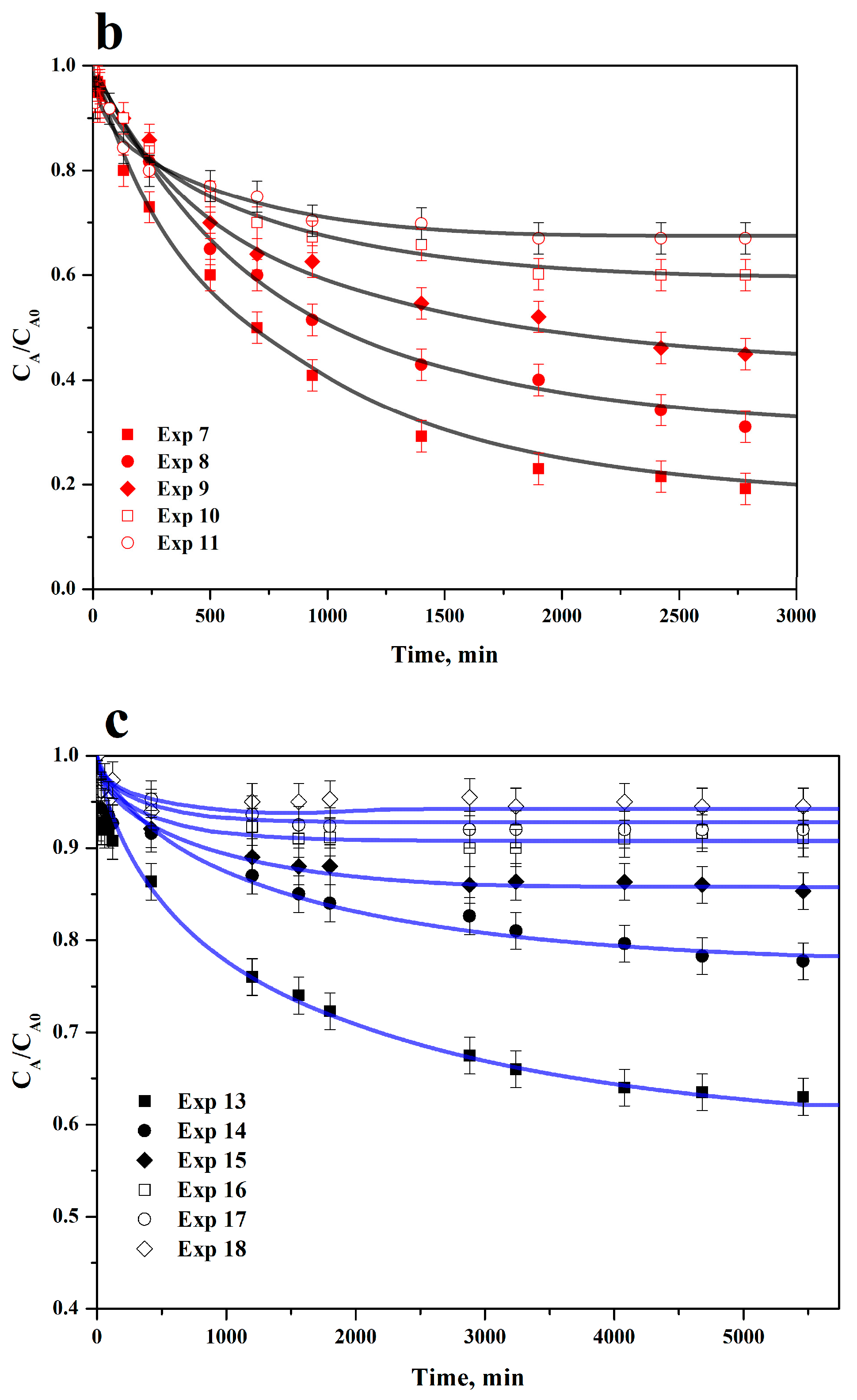

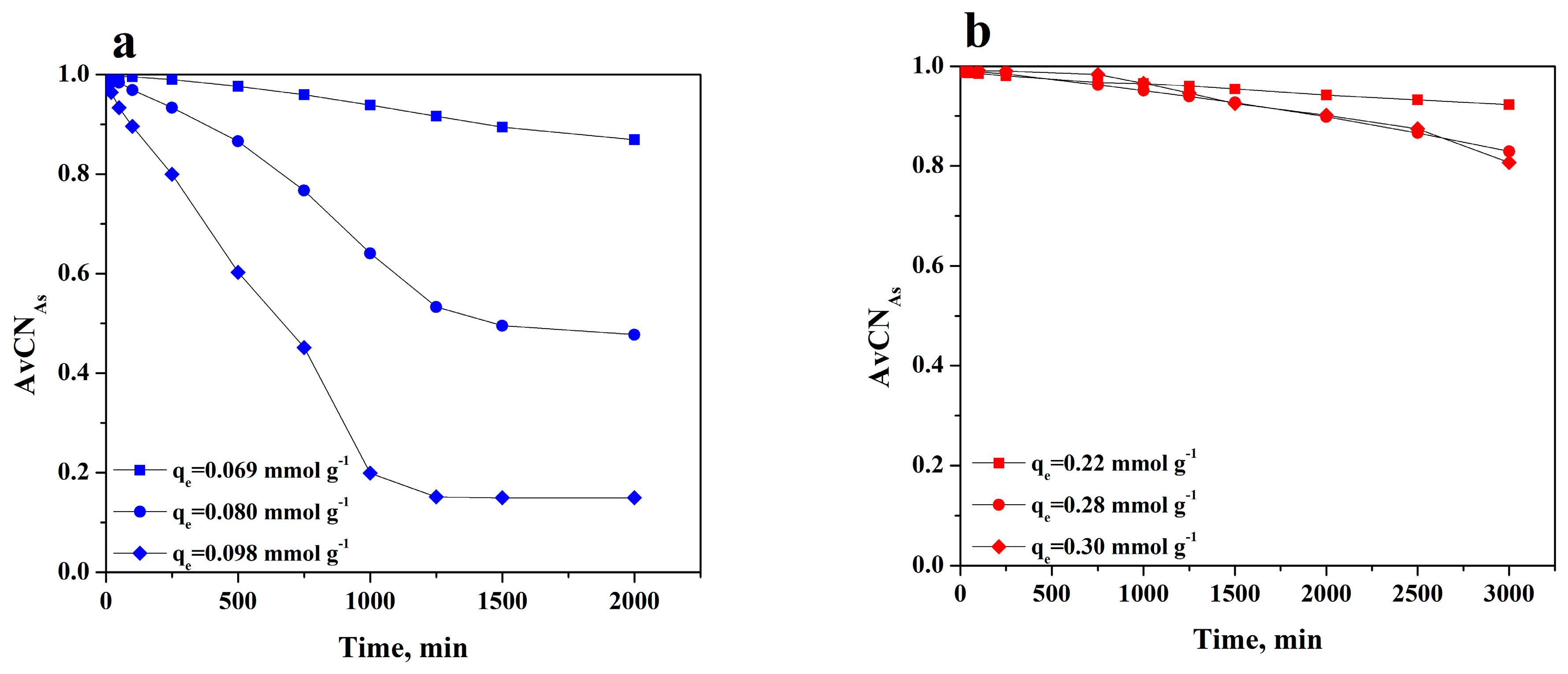

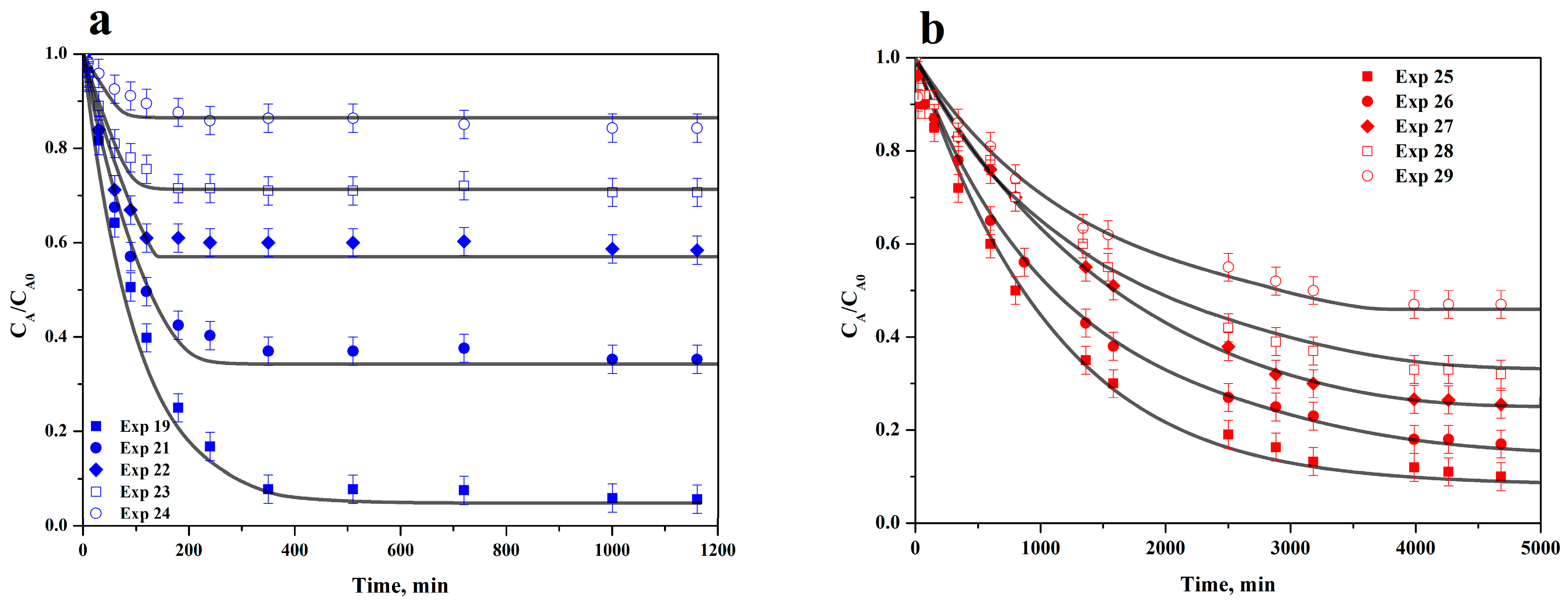

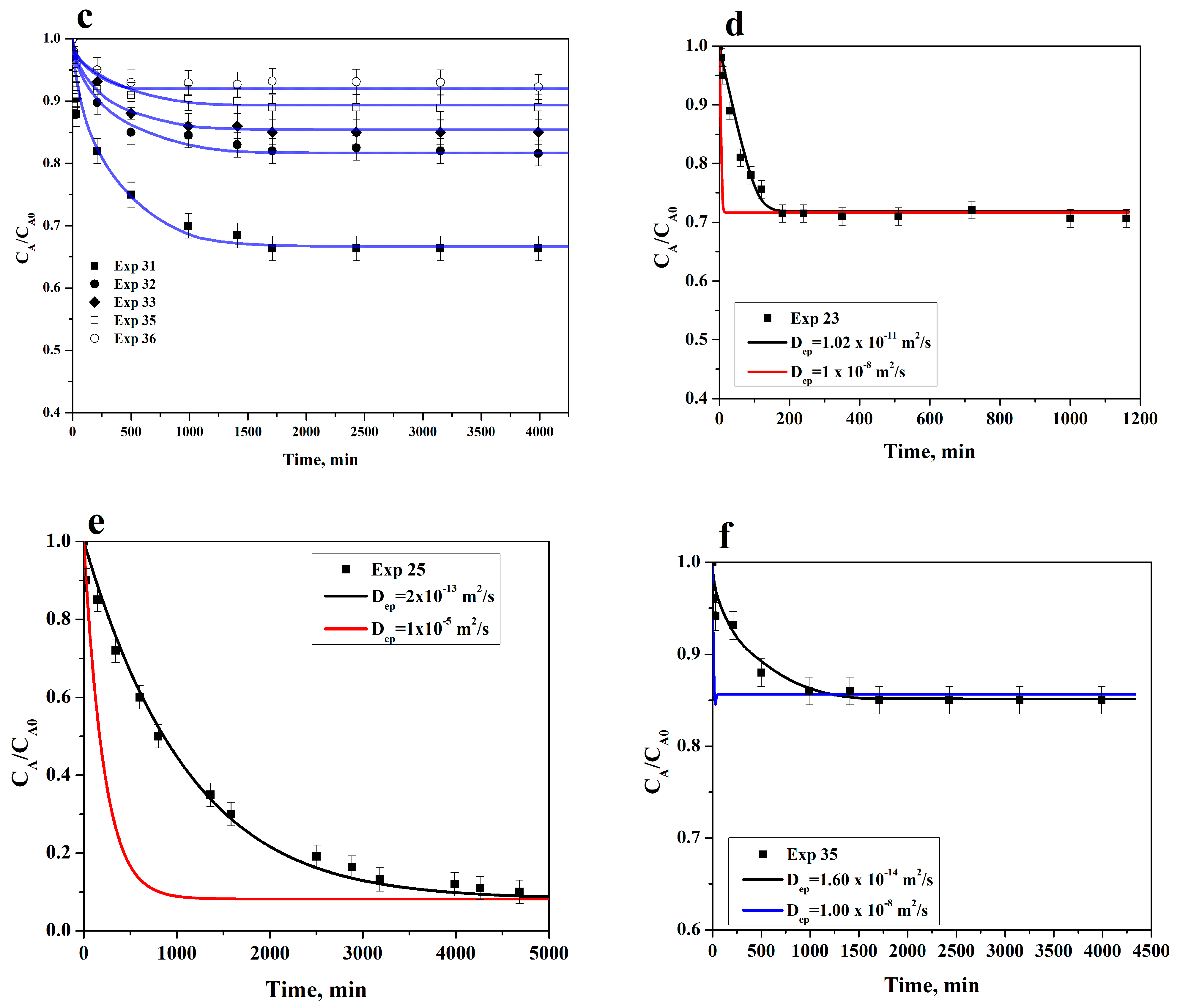

3.3. Adsorption Rate on BC

3.4. Adsorption Equilibrium on ACC

3.5. Adsorption Rate on ACC

3.6. Adsorption Comparison on BC and ACC

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Christian, D.; Gaekwad, A.; Dani, H.; Shabiimam, M.A.; Kandya, A. Recent techniques of textile industrial wastewater treatment: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 77, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Malik, A. Environmental and health effects of textile industry wastewater. In Environmental Deterioration and Human Health; Malik, A., Crohmann, E., Akhtar, R., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R.L.; Gupta, R.; Singh, R.P. Microbial degradation of textile dyes for environmental safety. In Advances in Biodegradation and Bioremediation of Industrial Waste; Chen, H., Gao, B., Wang, S., Fang, J., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R.P.; Singh, P.K.; Gupta, R.; Singh, R.L. Treatment and recycling of wastewater from textile industry. In Advances in Biological Treatment of Industrial Waste Water and Their Recycling for a Sustainable Future; Singh, R.L., Singh, R.P., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 225–266. [Google Scholar]

- Rana, S.; Sharma, R.; Chandra, S. Microbial degradation of synthetic textile dyes: A cost-effective and eco-friendly approach. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2013, 7, 2983–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.K.; Dash, R.R.; Bhunia, P. A review on chemical coagulation/flocculation technologies for removal of colour from textile wastewaters. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 93, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.-T.; Stevens, S.E.; Cerniglia, C.E. The reduction of azo dyes by the intestinal microflora. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 1992, 18, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doble, M.; Kumar, A. Biotreatment of Industrial Effluents, 1st ed.; Elsevier/Butterworth-Heinemann: Burlington, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T.-H.; Park, C.; Yang, J.; Kim, S. Comparison of disperse and reactive dye removals by chemical coagulation and Fenton oxidation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2004, 112, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üstün, G.E.; Solmaz, S.K.A.; Birgül, A. Regeneration of industrial district wastewater using a combination of Fenton process and ion exchange—A case study. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2007, 52, 425–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pormazar, S.M.; Dalvand, A. Adsorption of Direct Red 23 dye from aqueous solution by means of modified montmorillonite nanoclay as a superadsorbent: Mechanism, kinetic and isotherm studies. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 37, 2192–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praipipat, P.; Ngamsurach, P.; Khamkhae, P. Iron(III) oxide-hydroxide modification on Pterocarpus macrocarpus sawdust beads for direct red 28 dye removal. Arab. J. Chem. 2024, 17, 105514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.F.; Ashraf, M.; Javeed, A.; Anjum, A.A.; Sharif, A.; Saleem, M.; Mustafa, G.; Ashraf, M.; Saleem, A.; Akhtar, B. Association of textile industry effluent with mutagenicity and its toxic health implications upon acute and sub-chronic exposure. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2018, 190, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinola-Portilla, F.; Navarro-Mendoza, R.; Gutiérrez-Granados, S.; Morales-Muñoz, U.; Brillas-Coso, E.; Peralta-Hernández, J.M. A simple process for the deposition of TiO2 onto BDD by electrophoresis and its application to the photoelectrocatalysis of Acid Blue 80 dye. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2017, 802, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, S.; Mandal, A.K.; Behera, A.K.; Patra, S.; Nayak, R.; Behera, C.; Jena, M. A comprehensive review on phycoremediation of azo dye to combat industrial wastewater pollution. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 70, 107088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holkar, C.R.; Jadhav, A.J.; Pinjari, D.V.; Mahamuni, N.M.; Pandit, A.B. A critical review on textile wastewater treatments: Possible approaches. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 182, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, A.C.; Jadhav, N.C. Treatment of textile wastewater using adsorption and adsorbents. In Sustainable Technologies for Textile Wastewater Treatments; Muthu, S.S., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2021; pp. 235–273. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, R.; Shafiq, I.; Akhter, P.; Iqbal, M.J.; Hussain, M. A state-of-the-art review on wastewater treatment techniques: The effectiveness of adsorption method. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 9050–9066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nugraha, M.W.; Kim, S.; Roddick, F.; Xie, Z.; Fan, L. A review of the recent advancements in adsorption technology for removing antibiotics from hospital wastewater. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 70, 106960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Riaz, A.; Zeb, H.; Ali, A.; Mujahid, R.; Ahmad, F.; Zafar, M.S. Paving the path to water security: The role of advanced adsorbents in wastewater treatment. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 71, 107333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkurdi, S.S.A.; Al-Juboori, R.A.; Bundschuh, J.; Hamawand, I. Bone char as a green sorbent for removing health threatening fluoride from drinking water. Environ. Int. 2019, 127, 704–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, A.; Porbeni, D.W.; Omonmhenle, S.; Peretomode, E. Waste bone char-derived adsorbents: Characteristics, adsorption mechanism and model approach. Environ. Technol. Rev. 2023, 12, 175–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medellín-Castillo, N.A.; González-Fernández, L.A.; Thiodjio-Sendja, B.; Aguilera-Flores, M.M.; Leyva-Ramos, R.; Reyes-López, S.Y.; de León-Martínez, L.D.; Dias, J.M. Bone char for water treatment and environmental applications: A review. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 2023, 175, 106161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccirillo, C. Preparation, characterisation and applications of bone char, a food waste-derived sustainable material: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 339, 117896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Wei, B.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Han, L. A comprehensive review of bone char: Fabrication procedures, physicochemical properties, and environmental application. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medellin-Castillo, N.A.; Leyva-Ramos, R.; Ocampo-Perez, R.; Garcia de la Cruz, R.F.; Aragon-Piña, A.; Martinez-Rosales, J.M.; Guerrero-Coronado, R.M.; Fuentes-Rubio, L. Adsorption of Fluoride from Water Solution on Bone Char. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2007, 46, 9205–9212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinath, A.; Kadirvelu, K. Strategies to design modified activated carbon fibers for the decontamination of water and air. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2018, 16, 1137–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.F.; Sabri, M.A.; Fazal, H.; Hafeez, A.; Shezad, N.; Hussain, M. Recent trends in activated carbon fibers production from various precursors and applications—A comparative review. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2020, 145, 104715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, J.-H.; Kim, S.-H.; Kim, J.H.; Kang, H.-J.; Lee, J.H.; Jeon, H.J.; Jang, Y.H.; Lee, J.-H.; Lee, S.-Y.; Park, S.-J.; et al. Recent advances in activated carbon fibers for pollutant removal. Carbon Lett. 2025, 35, 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, F.J.; Sánchez− Albores, R.; Ashok, A.; Escorcia− García, J.; Cruz−Salomón, A.; Reyes− Vallejo, O.; Sebastian, P.J.; Velumani, S. Carica papaya seed− derived functionalized biochar: An environmentally friendly and efficient alternative for dye adsorption. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2025, 36, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, F.J.; Reyes-Vallejo, O.; Sánchez-Albores, R.M.; Sebastian, P.J.; Cruz-Salomón, A.; Hernández-Cruz, M.D.C.; Montejo-López, W.; González Reyes, M.; Serrano Ramirez, R.D.P.; Torres-Ventura, H.H. Activated Biochar from Pineapple Crown Biomass: A High-Efficiency Adsorbent for Organic Dye Removal. Sustainability 2024, 17, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyva-Ramos, R.; Diaz-Flores, P.E.; Leyva-Ramos, J.; Femat-Flores, R.A. Kinetic modeling of pentachlorophenol adsorption from aqueous solution on activated carbon fibers. Carbon 2007, 45, 2280–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Ramón, M.V.; Ocampo-Pérez, R.; Bautista-Toledo, M.I.; Rivera-Utrilla, J.; Moreno-Castilla, C.; Sánchez-Polo, M. Removal of bisphenols A and S by adsorption on activated carbon clothes enhanced by the presence of bacteria. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 669, 767–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M. Activated carbon fiber: Fundamentals and applications. Carbon 1994, 32, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Yang, X.; Huang, L.; Li, Y.; Hao, L.; Pei, Q.; Pei, X. A critical review of breakthrough models with analytical solutions in a fixed-bed column. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 59, 105065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Guo, X. Adsorption kinetic models: Physical meanings, applications, and solving methods. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 390, 122156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Cai, J.; Pan, B. Mathematically modeling fixed-bed adsorption in aqueous systems. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. A. 2013, 14, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Contreras, S.; Leyva-Ramos, R.; Ocampo-Pérez, R.; Aguilar-Madera, C.G.; Flores-Cano, J.V.; Medellín-Castillo, N.A. Mathematical modeling of breakthrough curves for 8-hydroxyquinoline removal from fundamental equilibrium and adsorption rate studies. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 54, 103967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudechiche, N.; Fares, M.; Ouyahia, S.; Yazid, H.; Trari, M.; Sadaoui, Z. Comparative study on removal of two basic dyes in aqueous medium by adsorption using activated carbon from Ziziphus lotus stones. Microchem. J. 2019, 146, 1010–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, V.D.; Tran, T.K.N.; Nguyen, A.-T.; Tran, V.A.; Nguyen, T.D.; Le, V.T. Comparative study on adsorption of cationic and anionic dyes by nanomagnetite supported on biochar derived from Eichhornia crassipes and Phragmites australis stems. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2021, 16, 100569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Hadi, P.; Joshi, R.; Alhamzani, A.G.; Hsiao, B.S. A Comparative Study of Mechanism and Performance of Anionic and Cationic Dialdehyde Nanocelluloses for Dye Adsorption and Separation. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 8634–8649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thanarasu, A.; Periyasamy, K.; Manickam Periyaraman, P.; Devaraj, T.; Velayutham, K.; Subramanian, S. Comparative studies on adsorption of dye and heavy metal ions from effluents using eco-friendly adsorbent. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 36, 775–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Wang, X.; Xu, Q.; Dhaouadi, F.; Sellaoui, L.; Seliem, M.K.; Ben Lamine, A.; Belmabrouk, H.; Bajahzar, A.; Bonilla-Petriciolet, A.; et al. Adsorption of methylene blue from aqueous solution on activated carbons and composite prepared from an agricultural waste biomass: A comparative study by experimental and advanced modeling analysis. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 430, 132801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiol, N.; Villaescusa, I. Determination of sorbent point zero charge: Usefulness in sorption studies. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2009, 7, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Utrilla, J.; Sánchez-Polo, M. Ozonation of 1, 3, 6-naphthalenetrisulphonic acid catalysed by activated carbon in aqueous phase. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2002, 39, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segovia-Sandoval, S.J.; Padilla-Ortega, E.; Carrasco-Marín, F.; Berber-Mendoza, M.S.; Ocampo-Pérez, R. Simultaneous removal of metronidazole and Pb (II) from aqueous solution onto bifunctional activated carbons. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 25916–25931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Merino, M.A.; Fontecha-Cámara, M.A.; López-Ramón, M.V.; Moreno-Castilla, C. Temperature dependence of the point of zero charge of oxidized and non-oxidized activated carbons. Carbon 2008, 46, 778–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Blancas, V.; Aguilar-Madera, C.G.; Flores-Cano, J.V.; Leyva-Ramos, R.; Padilla-Ortega, E.; Ocampo-Pérez, R. Evaluation of mass transfer mechanisms involved during the adsorption of metronidazole on granular activated carbon in fixed bed column. J. Water Process Eng. 2020, 36, 101303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyva-Ramos, R.; Geankoplis, C.J. Model simulation and analysis of surface diffusion of liquids in porous solids. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1985, 40, 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocampo-Pérez, R.; Leyva-Ramos, R.; Sánchez-Polo, M.; Rivera-Utrilla, J. Role of pore volume and surface diffusion in the adsorption of aromatic compounds on activated carbon. Adsorption 2013, 19, 945–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocampo-Pérez, R.; Aguilar-Madera, C.G.; Díaz-Blancas, V. 3D modeling of overall adsorption rate of acetaminophen on activated carbon pellets. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 321, 510–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyva-Ramos, R.; Rivera-Utrilla, J.; Medellin-Castillo, N.A.; Sánchez-Polo, M. Kinetic modeling of fluoride adsorption from aqueous solution onto bone char. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 158, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furusawa, T.; Smith, J.M. Fluid-particle and intraparticle mass transport rates in slurries. Ind. Eng. Chem. Fund. 1973, 12, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilke, C.; Chang, P. Correlation of diffusion coefficients in dilute solutions. AIChE J. 1955, 1, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudhoo, A.; Otero, M.; Chu, K.H. Insights into adsorbent tortuosity across aqueous adsorption systems. Particuology 2024, 88, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauletto, P.S.; Dotto, G.L.; Salau, N.P.G. Diffusion mechanisms and effect of adsorbent geometry on heavy metal adsorption. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2020, 157, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valderrama, C.; Gamisans, X.; de las Heras, X.; Farrán, A.; Cortina, J.L. Sorption kinetics of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons removal using granular activated carbon: Intraparticle diffusion coefficients. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 157, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medellín-Castillo, N.A. Remoción de Fluoruros En Solución Acuosa por Medio de Adsorción Sobre Varios Materiales. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Autónoma de San Luis Potosí, San Luis Potosi, Mexico, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Leyva-Ramos, R.; Ocampo-Perez, R.; Mendoza-Barron, J. External mass transfer and hindered diffusion of organic compounds in the adsorption on activated carbon cloth. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 183, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez-García, G.D.; Leyva-Ramos, R. Hindered diffusion of heavy metal cations in the adsorption rate on activated carbon fiber. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2023, 196, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satterfield, C.N.; Colton, C.K.; Pitcher, W.H. Restricted diffusion in liquids within fine pores. AIChE J. 1973, 19, 628–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechadilok, P.; Deen, W.M. Hindrance factors for diffusion and convection in pores. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2006, 45, 6953–6959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouquerol, J.; Rouquerol, F.; Sing, K. Adsorption by Powders and Porous Solids: Principles, Methodology and Applications; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sing, K.S.W. Reporting physisorption data for gas/solid systems with special reference to the determination of surface area and porosity (Recommendations 1984). Pure Appl. Chem. 1985, 57, 603–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, C.H.; Smith, D.; Huitson, A. A general treatment and classification of the solute adsorption isotherm. I. Theoretical. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1974, 47, 755–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ip, A.W.M.; Barford, J.P.; McKay, G. A comparative study on the kinetics and mechanisms of removal of Reactive Black 5 by adsorption onto activated carbons and bone char. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 157, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ng, D.H.L.; Song, P.; Kong, C.; Song, Y.; Yang, P. Preparation and characterization of high-surface-area activated carbon fibers from silkworm cocoon waste for congo red adsorption. Biomass Bioenergy 2015, 75, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.; Rodríguez-Reinoso, F. Activated Carbon; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 143–242. [Google Scholar]

- Gligorijević, B.R.; Vilotijević, M.; Šćepanović, M.; Vuković, N.S.; Radović, N.A. Substrate preheating and structural properties of power plasma sprayed hydroxyapatite coatings. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccirillo, C.; Moreira, I.S.; Novais, R.M.; Fernandes, A.J.S.; Pullar, R.C.; Castro, P.M.L. Biphasic apatite-carbon materials derived from pyrolysed fish bones for effective adsorption of persistent pollutants and heavy metals. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 4884–4894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristea, M.-E.; Zarnescu, O. Indigo Carmine: Between Necessity and Concern. J. Xenobiotics 2023, 13, 509–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coltre, D.S.C.; Cionek, C.A.; Meneguin, J.G.; Maeda, C.H.; Braga, M.U.C.; de Araújo, A.C.; Gauze, G.F.; de Barros, M.A.S.D.; Arroyo, P.A. Study of dye desorption mechanism of bone char utilizing different regenerating agents. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, M.; Liu, J.; Han, L.; Qin, Q.; Liu, X. Adsorption/desorption behavior of ionic dyes on sintered bone char. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2023, 297, 127405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, P.D.L.; Cruz, M.A.P.; Souza, C.R.; Santos, N.T.G.; Nucci, E.R.; Rocha, S.D.F. Removal of refractory organics from saline concentrate produced by electrodialysis in petroleum industry using bone char. Adsorption 2017, 23, 983–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyabe, K.; Takeuchi, S. Analysis of surface diffusion phenomena in liquid phase adsorption. J. Phys. Chem. B 1997, 101, 7773–7779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Flores, P.E.; Leyva-Ramos, R.; Guerrero-Coronado, R.M.; Mendoza-Barron, J. Adsorption of pentachlorophenol from aqueous solution onto activated carbon fiber. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 101, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.-S.; Zheng, T.; Wang, P.; Jiang, J.-P.; Li, N. Adsorption isotherm, kinetic and mechanism studies of some substituted phenols on activated carbon fiber. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 157, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrache, Z.; Abbas, M.; Aksil, T.; Trari, M. Thermodynamic and kinetics studies on adsorption of Indigo Carmine from aqueous solution by activated carbon. Microchem. J. 2019, 144, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, A.G.S.; Torres, J.D.; Faria, E.A.; Dias, S.C.L. Comparative adsorption studies of indigo carmine dye on chitin and chitosan. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2004, 277, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiwalak, N.; Rattanaphani, S.; Bremner, J.B.; Rattanaphani, V. Equilibrium and kinetic modeling of the adsorption of indigo carmine onto silk. Fibers Polym. 2010, 11, 572–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kammah, M.; Elkhatib, E.; Gouveia, S.; Cameselle, C.; Aboukila, E. Cost-effective ecofriendly nanoparticles for rapid and efficient indigo carmine dye removal from wastewater: Adsorption equilibrium, kinetics and mechanism. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2022, 28, 102595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kammah, M.; Elkhatib, E.; Gouveia, S.; Cameselle, C.; Aboukila, E. Enhanced removal of Indigo Carmine dye from textile effluent using green cost-efficient nanomaterial: Adsorption, kinetics, thermodynamics and mechanisms. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2022, 29, 100753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, R.M.; de Oliveira, N.M.; Lima, L.L.S.; Campista, A.L.D.M.; Stapelfeldt, D.M.A. Adsorption of indigo carmine on Pistia stratiotes dry biomass chemically modified. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 28614–28621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.A.; Brick, A.A.; Mohamed, A.A. An efficient adsorption of indigo carmine dye from aqueous solution on mesoporous Mg/Fe layered double hydroxide nanoparticles prepared by controlled sol-gel route. Chemosphere 2017, 174, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, H.; Wu, S.; Li, F.; Zhi, P. Adsorption of hazardous dyes indigo carmine and acid red on nanofiber membranes. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 900–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastgerdi, Z.H.; Meshkat, S.S.; Esrafili, M.D. Enhanced adsorptive removal of Indigo carmine dye performance by functionalized carbon nanotubes based adsorbents from aqueous solution: Equilibrium, kinetic, and DFT study. J. Nanostruct. Chem. 2019, 9, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadhri, N.; Saad, M.E.K.; ben Mosbah, M.; Moussaoui, Y. Batch and continuous column adsorption of indigo carmine onto activated carbon derived from date palm petiole. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 102775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harja, M.; Buema, G.; Bucur, D. Recent advances in removal of Congo Red dye by adsorption using an industrial waste. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimonses, V.; Lei, S.; Jin, B.; Chow, C.W.K.; Saint, C. Kinetic study and equilibrium isotherm analysis of Congo Red adsorption by clay materials. Chem. Eng. J. 2009, 148, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, N.; Zhang, H.; Baeyens, J. Adsorption of Congo red dye on FexCo3-xO4 nanoparticles. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 238, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ausavasukhi, A.; Kampoosaen, C.; Kengnok, O. Adsorption characteristics of Congo red on carbonized leonardite. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 134, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Moghaddam, L.; O’Hara, I.M.; Doherty, W.O.S. Congo Red adsorption by ball-milled sugarcane bagasse. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 178, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srilakshmi, C.; Saraf, R. Ag-doped hydroxyapatite as efficient adsorbent for removal of Congo red dye from aqueous solution: Synthesis, kinetic and equilibrium adsorption isotherm analysis. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2016, 219, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorencgrabowska, E.; Gryglewicz, G. Adsorption characteristics of Congo Red on coal-based mesoporous activated carbon. Dye. Pigment. 2007, 74, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purkait, M.K.; Maiti, A.; DasGupta, S.; De, S. Removal of congo red using activated carbon and its regeneration. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 145, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdy, A.; Mostafa, M.R.; Moustafa, S.A.; Mohamed, G.G.; Fouad, O.A. Kinetics and adsorption isotherms studies for the effective removal of Evans blue dye from an aqueous solution utilizing forsterite nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergis, B.R.; Kottam, N.; Hari Krishna, R.; Nagabhushana, B.M. Removal of Evans Blue dye from aqueous solution using magnetic spinel ZnFe2O4 nanomaterial: Adsorption isotherms and kinetics. Nano-Struct. Nano-Objects 2019, 18, 100290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, I.K.; Ju, Y.H.; Ayucitra, A.; Ismadji, S. Evans blue removal from wastewater by rarasaponin–bentonite. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 10, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiah, F.B.D.; Su, B.; Bettahar, N. Removal of Evans Blue by using Nickel-Iron Layered Double Hydroxide (LDH) Nanoparticles: Effect of Hydrothermal Treatment Temperature on Textural Properties and Dye Adsorption. Macromol. Symp. 2008, 273, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound Name | Molecular Structure | 1 Molecular Size Nm | M.W. g mol−1 | 2 Projected Area Å2 | 3 Diameter nm | 4 Log KOW | pKa | 5 Solubility g L−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indigo Carmine |  | X = 1.55 Y = 0.65 Z = 0.41 | 466.4 | 100.51 | 0.83 | 1.01 | 9.76 | 1 |

| Congo Red |  | X = 2.57 Y = 0.65 Z = 0.48 | 696.7 | 167.01 | 1.27 | 3.61 | 0.21 | 33 |

| Blue Evans |  | X = 2.61 Y = 0.80 Z = 0.57 | 960.8 | 208.80 | 1.47 | −4.15 | 3.42, 8.9 | 280 |

| Bone Char | Activated Carbon Cloth | |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon, % | 8–11 | 95 |

| Mineral (hydroxyapatite), % | 70–76 | - |

| pHPZC | 10.1 | 8.0 |

| Area BET, m2 g−1 | 90 | 2128 |

| Mean pore width, nm | 10.75 | 1.69 |

| Carbon area, % | 44–66 | 100 |

| Particle geometry | granular | fiber |

| Particle size | 0.22 mm | 4.5 µm |

| Dye | Adsorbent | Experimental Conditions | Mass Adsorbed, mg g−1 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC | Commercial AC | pH = 2, 298 K | 55 | [78] |

| IC | Chitosan | 298 K | 70 | [79] |

| IC | Silk | pH = 4, 303 K | 5 | [80] |

| IC | Nano water treatment residuals | pH = 5, 298 K | 173 | [81] |

| IC | Nano Moringa oleifera seeds | pH = 4, 303 K | 60 | [82] |

| IC | Activated Pistia stratiotes | pH = 5, 298 K | 41 | [83] |

| IC | Nano Mg/Fe DLH | pH = 9.5 | 62 | [84] |

| IC | Nano Fiber | pH = 2, 298 K | 267 | [85] |

| IC | Carbon nanotubes | pH = 6 | 136 | [86] |

| IC | AC Palm Petiole | pH = 8 | 54 | [87] |

| IC | Bone Char | pH = 7, 298 K | 50 | This work |

| IC | ACC | pH = 7, 298 K | 506 | This work |

| CR | Fly Ash | 298 K | 22 | [88] |

| CR | Sodium bentonite | pH = 7.5, 303 K | 20 | [89] |

| CR | FexCo3-xO4 nanoparticles | - | 127 | [90] |

| CR | Leonardite Carbon | pH = 7, 298 K | 60 | [91] |

| CR | Sugarcane bagasse | pH = 5 | 38 | [92] |

| CR | Ag-doped hydroxyapatite | No pH control | 267 | [93] |

| CR | Mesoporous AC | pH = 8, 298 K | 189 | [94] |

| CR | AC Fiber | pH = 2 | 512 | [67] |

| CR | Commercial AC | pH = 7, 303 K | 300 | [95] |

| CR | Bone Char | pH = 7, 298 K | 206 | This work |

| CR | ACC | pH = 7, 298 K | 187 | This work |

| EB | Fosterite Nanoparticles | pH = 3, 298 K | 42 | [96] |

| EB | ZnFe2O4 Nanoparticles | pH = 7, 298 K | 40 | [97] |

| EB | Bentonite | - | 34 | [98] |

| EB | NiFeCO3 HDL | 297 K | 44 | [99] |

| EB | Bone Char | pH = 7, 298 K | 59 | This work |

| EB | ACC | pH = 7, 298 K | 27 | This work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aguirre-Contreras, S.; López-Ramón, M.V.; Velo-Gala, I.; Álvarez-Merino, M.Á.; Aguilar-Aguilar, A.; Ocampo-Pérez, R. A Comparative Study of the Adsorption of Industrial Anionic Dyes with Bone Char and Activated Carbon Cloth. Water 2025, 17, 3422. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233422

Aguirre-Contreras S, López-Ramón MV, Velo-Gala I, Álvarez-Merino MÁ, Aguilar-Aguilar A, Ocampo-Pérez R. A Comparative Study of the Adsorption of Industrial Anionic Dyes with Bone Char and Activated Carbon Cloth. Water. 2025; 17(23):3422. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233422

Chicago/Turabian StyleAguirre-Contreras, Samuel, María Victoria López-Ramón, Inmaculada Velo-Gala, Miguel Ángel Álvarez-Merino, Angélica Aguilar-Aguilar, and Raúl Ocampo-Pérez. 2025. "A Comparative Study of the Adsorption of Industrial Anionic Dyes with Bone Char and Activated Carbon Cloth" Water 17, no. 23: 3422. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233422

APA StyleAguirre-Contreras, S., López-Ramón, M. V., Velo-Gala, I., Álvarez-Merino, M. Á., Aguilar-Aguilar, A., & Ocampo-Pérez, R. (2025). A Comparative Study of the Adsorption of Industrial Anionic Dyes with Bone Char and Activated Carbon Cloth. Water, 17(23), 3422. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233422