Optimization Design of Liquid–Gas Jet Pump Based on RSM and CFD: A Comprehensive Analysis of the Optimization Mechanism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Model Design

2.1. Jet Pump Theoretical Equations

2.1.1. Fluid Dynamics Equations

- (1)

- Continuity Equation

- (2)

- Momentum Equation

2.1.2. Basic Performance Equations of Jet Pumps

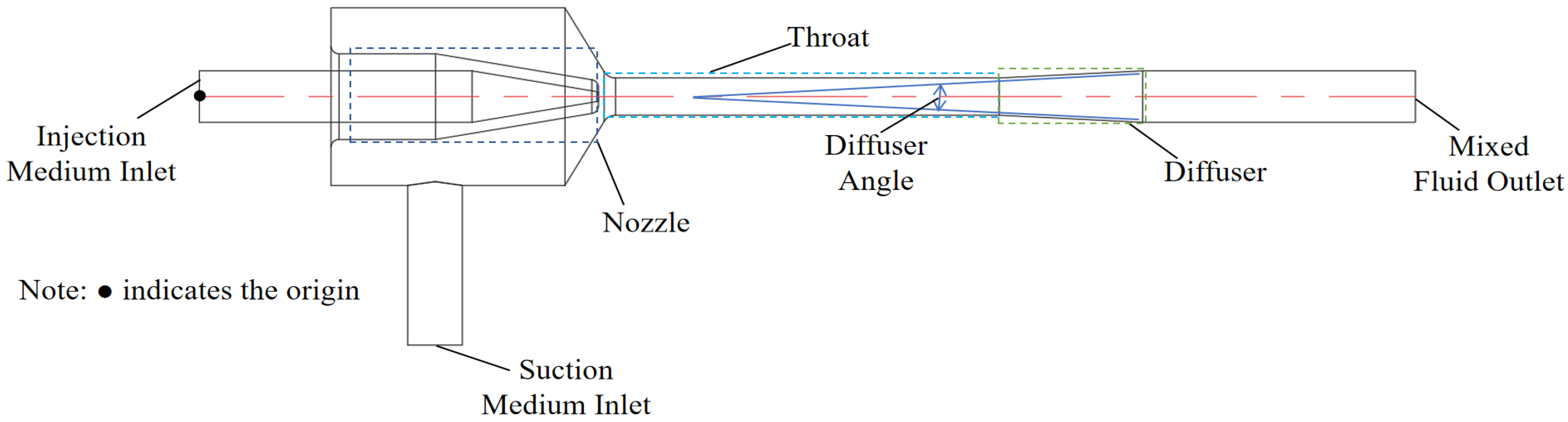

2.2. Geometric Model Establishment

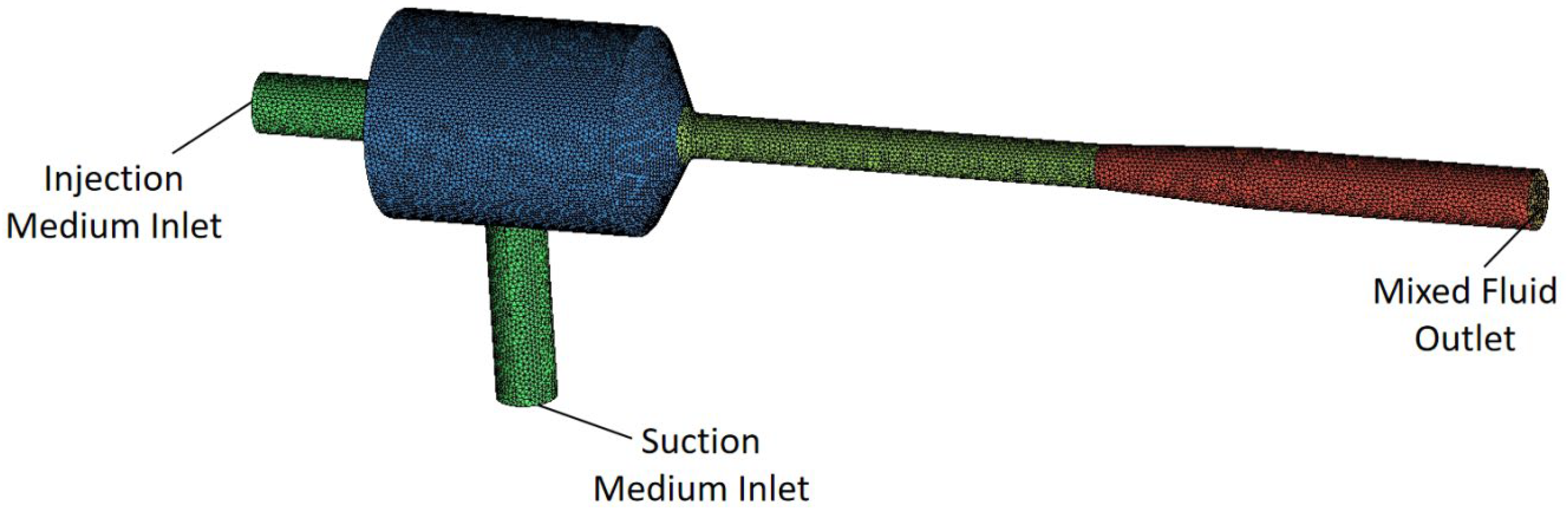

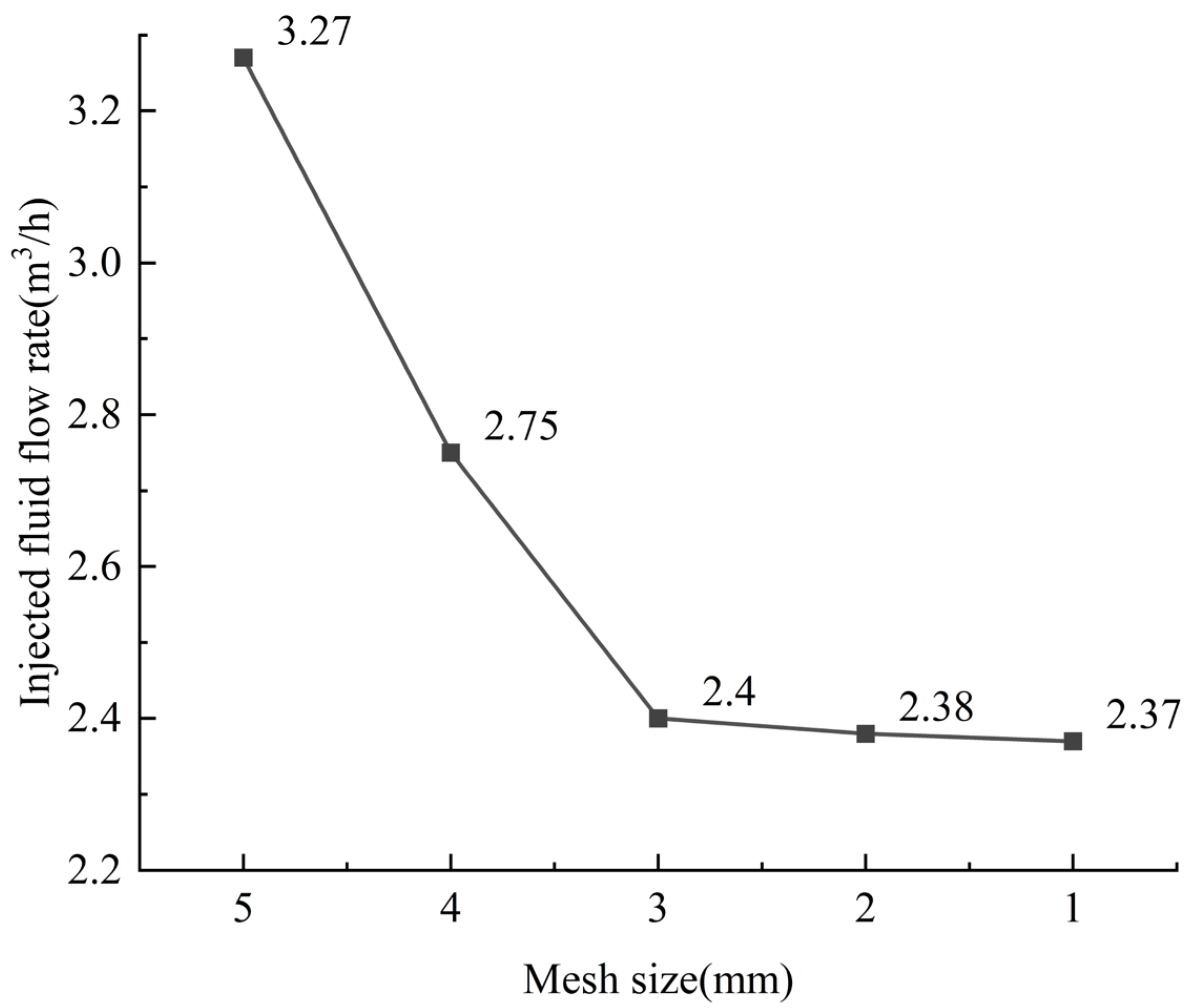

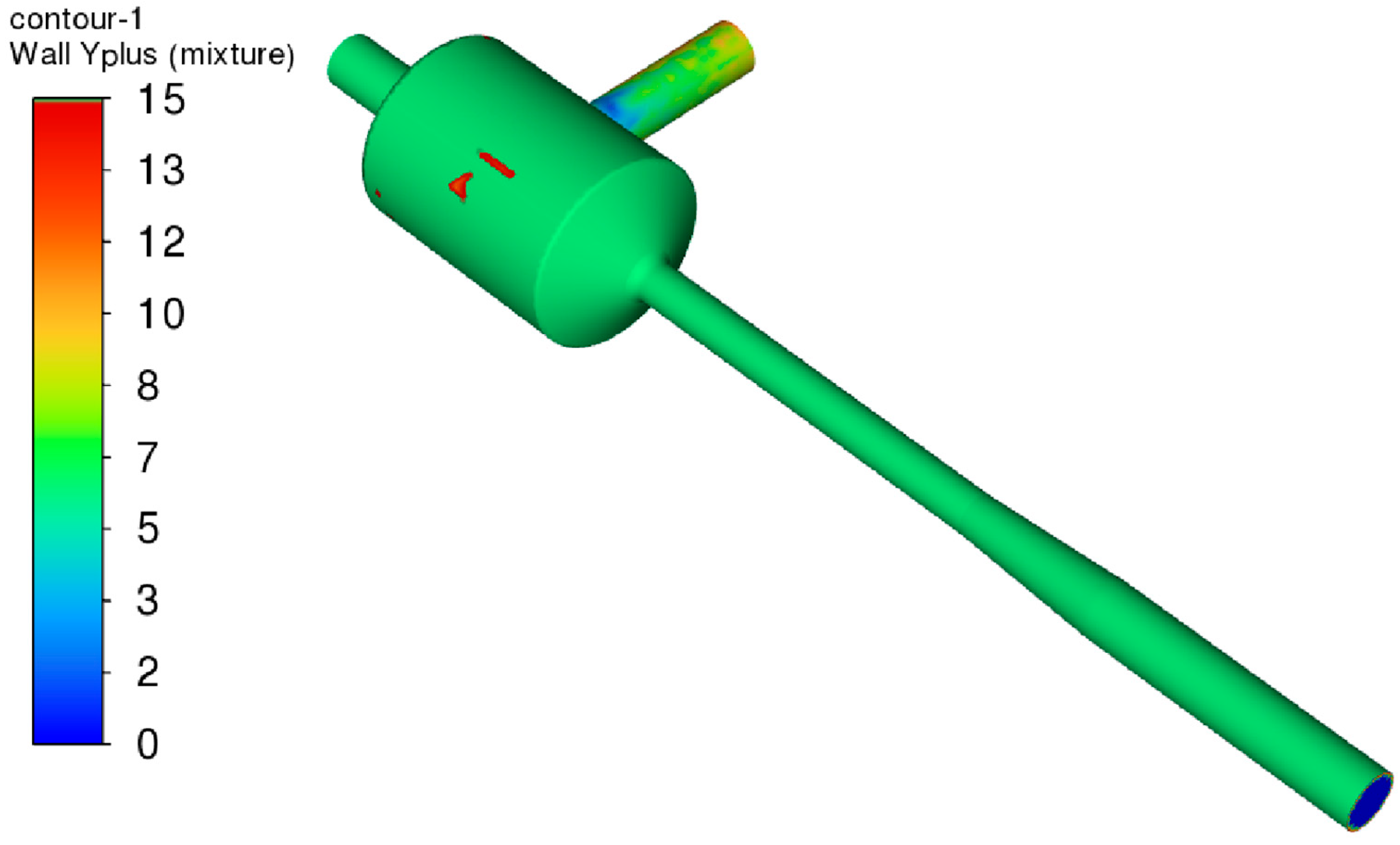

2.3. Mesh Generation and Boundary Condition Determination

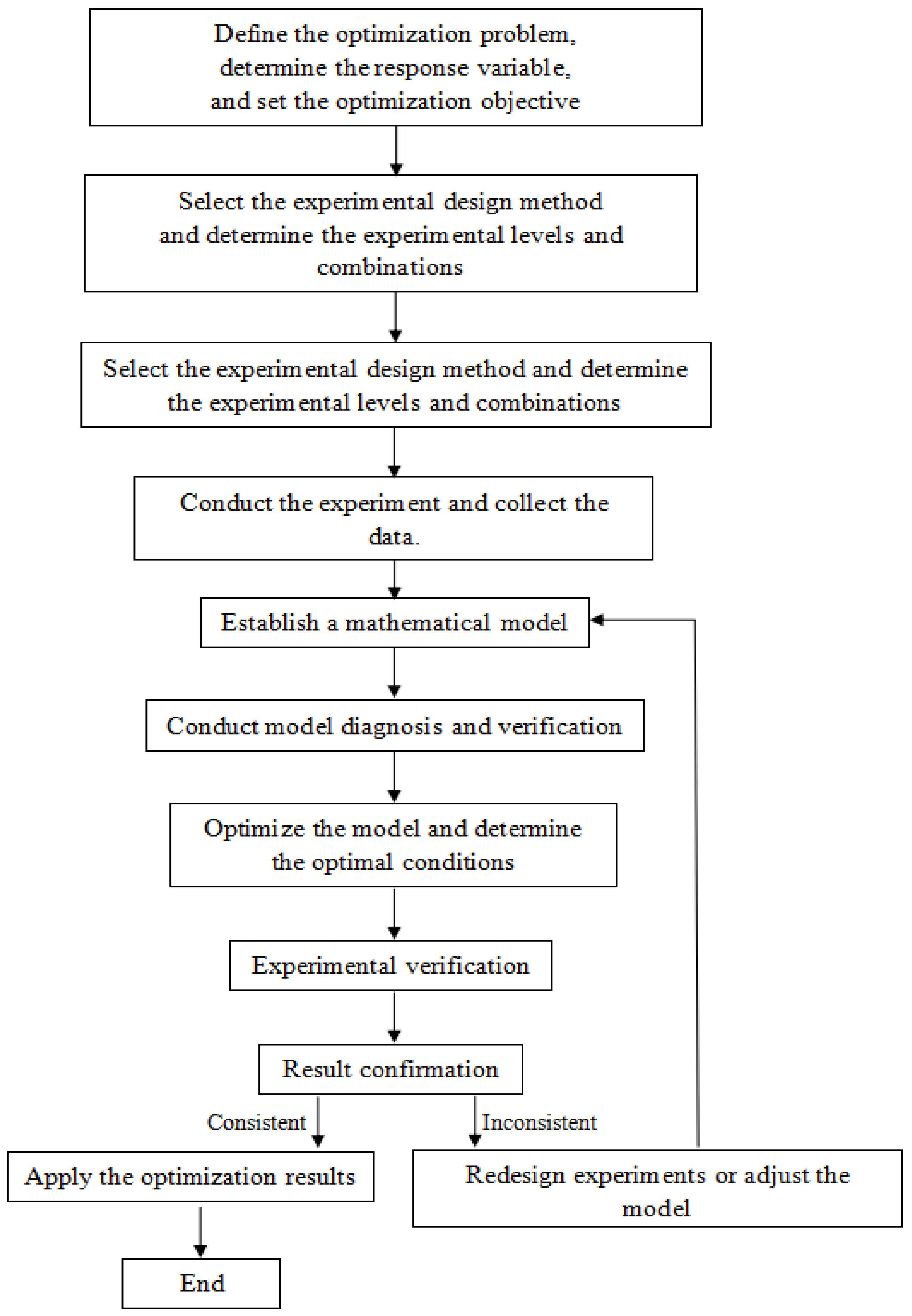

2.4. Principles of Response Surface Methodology (RSM)

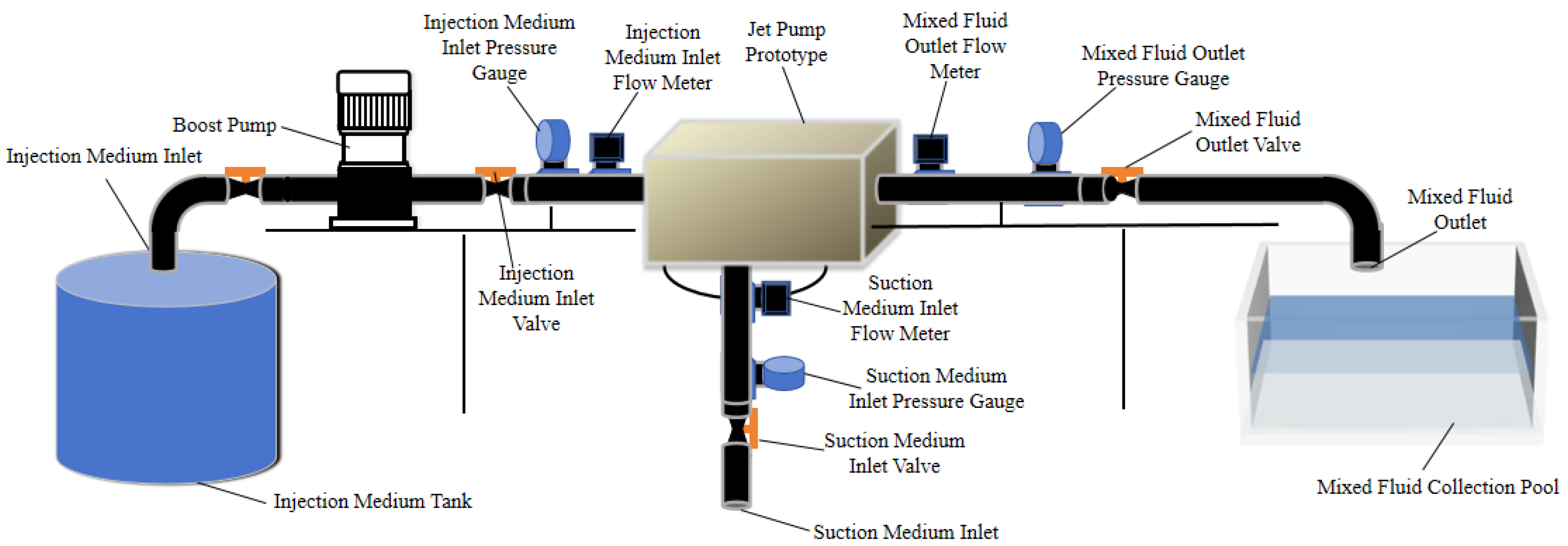

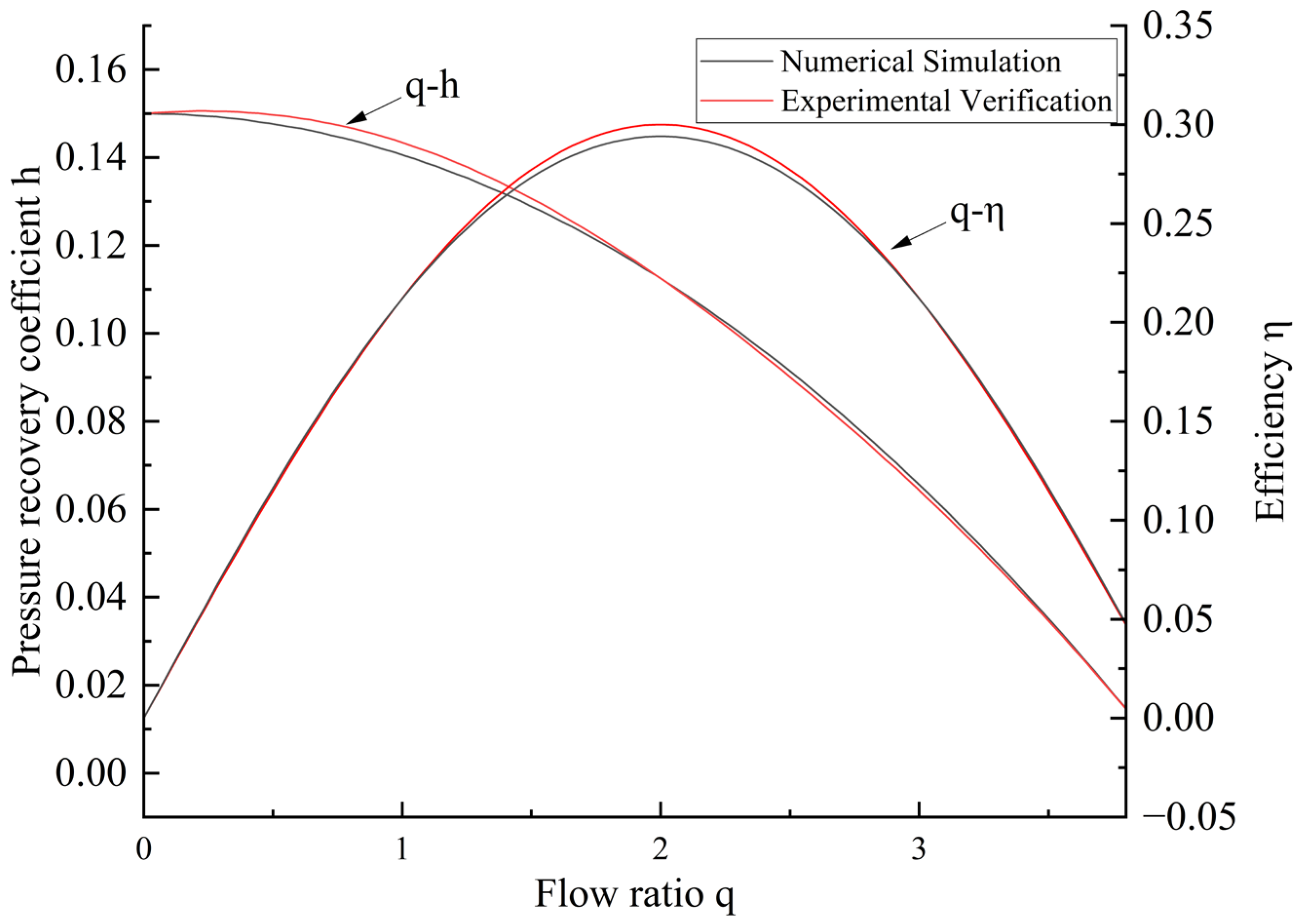

3. Experimental Verification

4. Analysis of the Influence of Single Factors on Ejector Performance

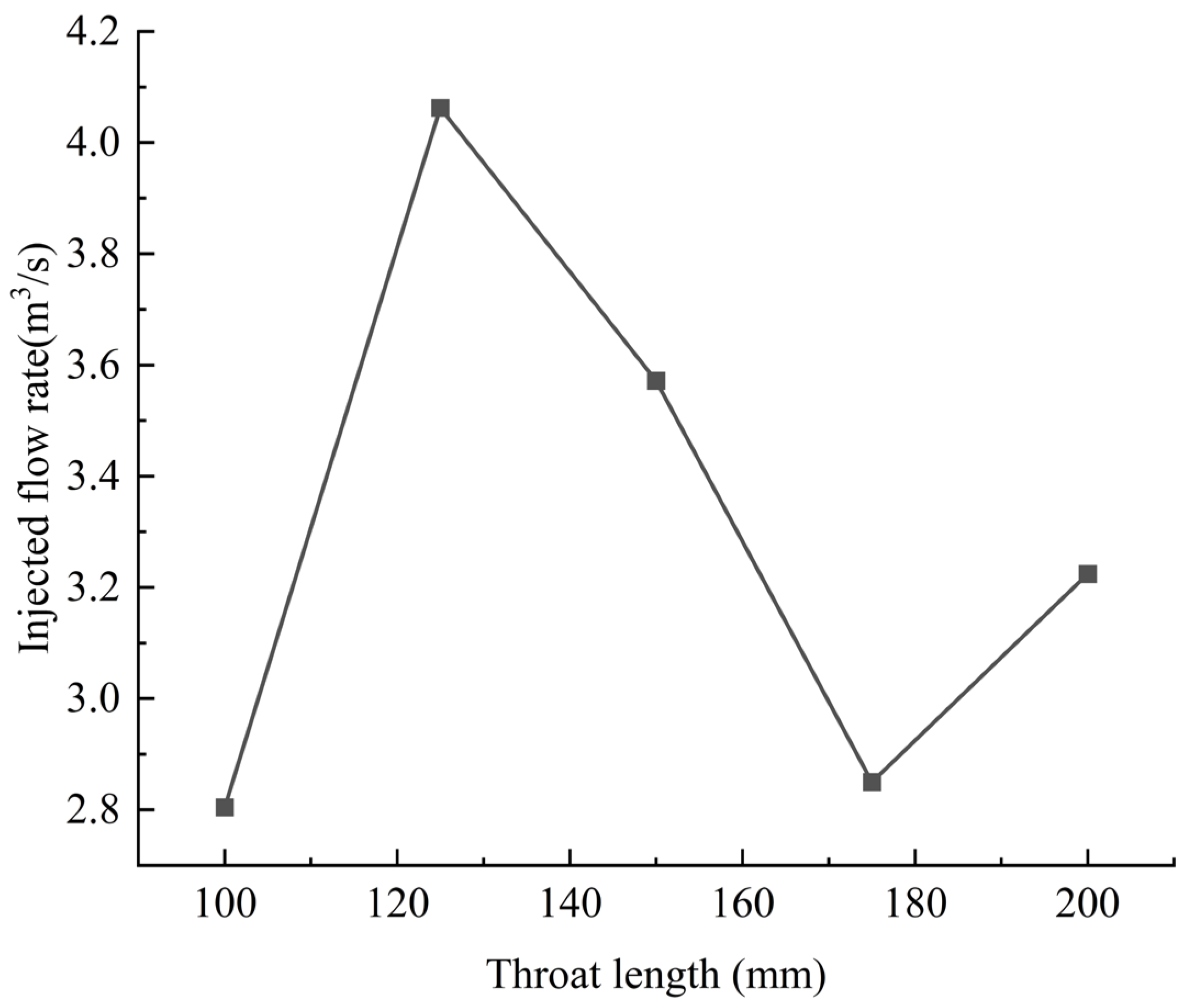

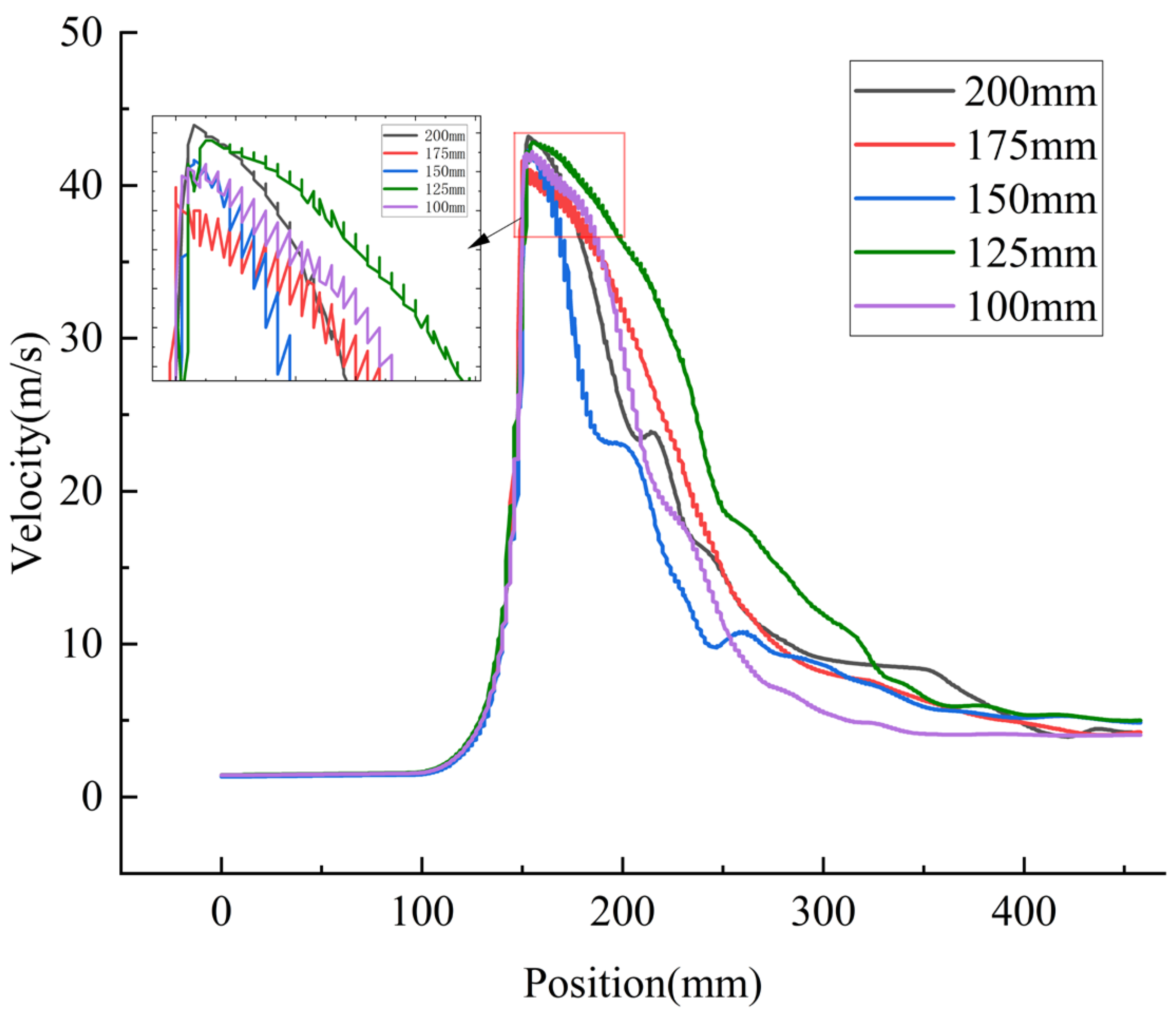

4.1. Influence of Throat Length (L) on Ejector Performance

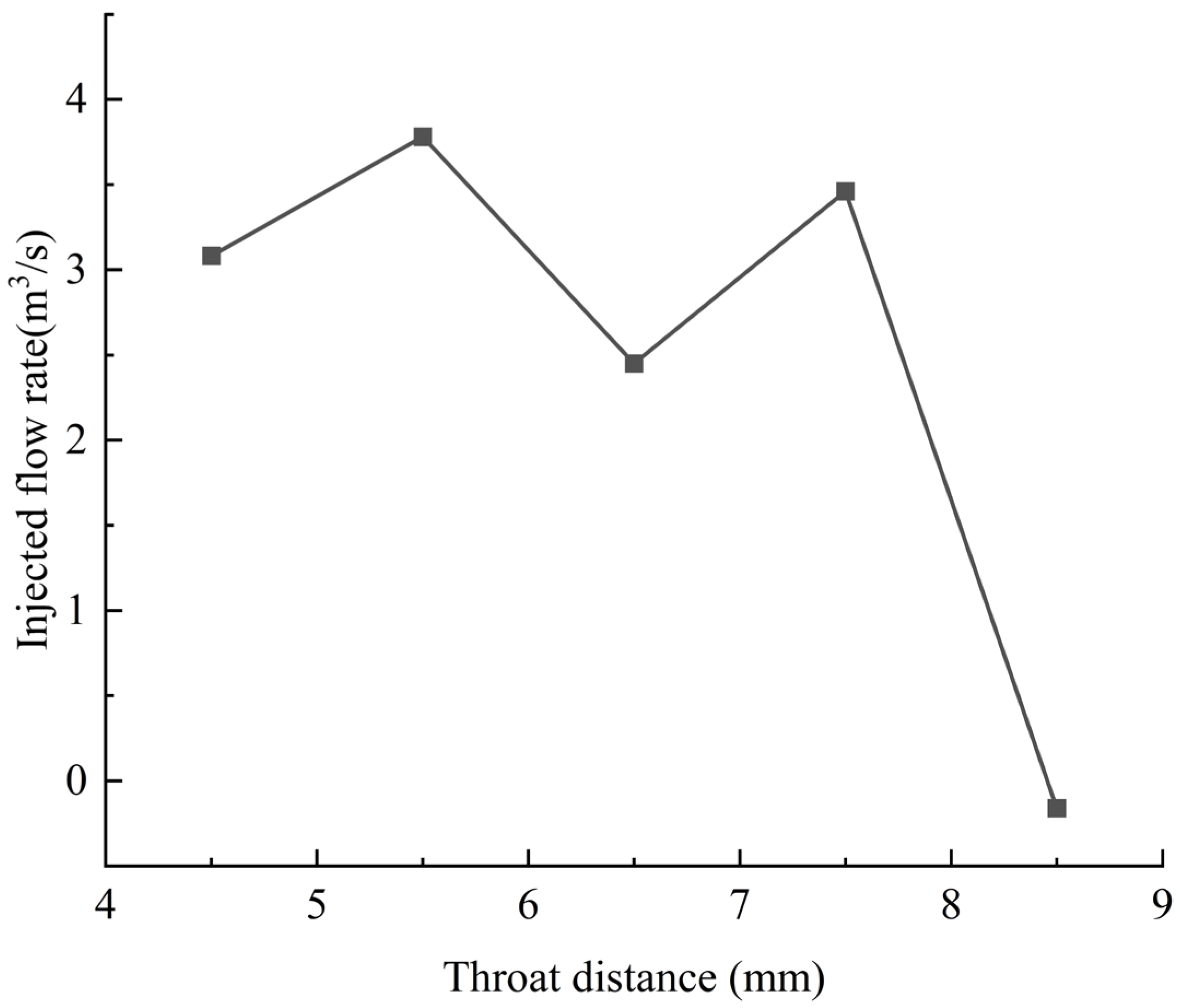

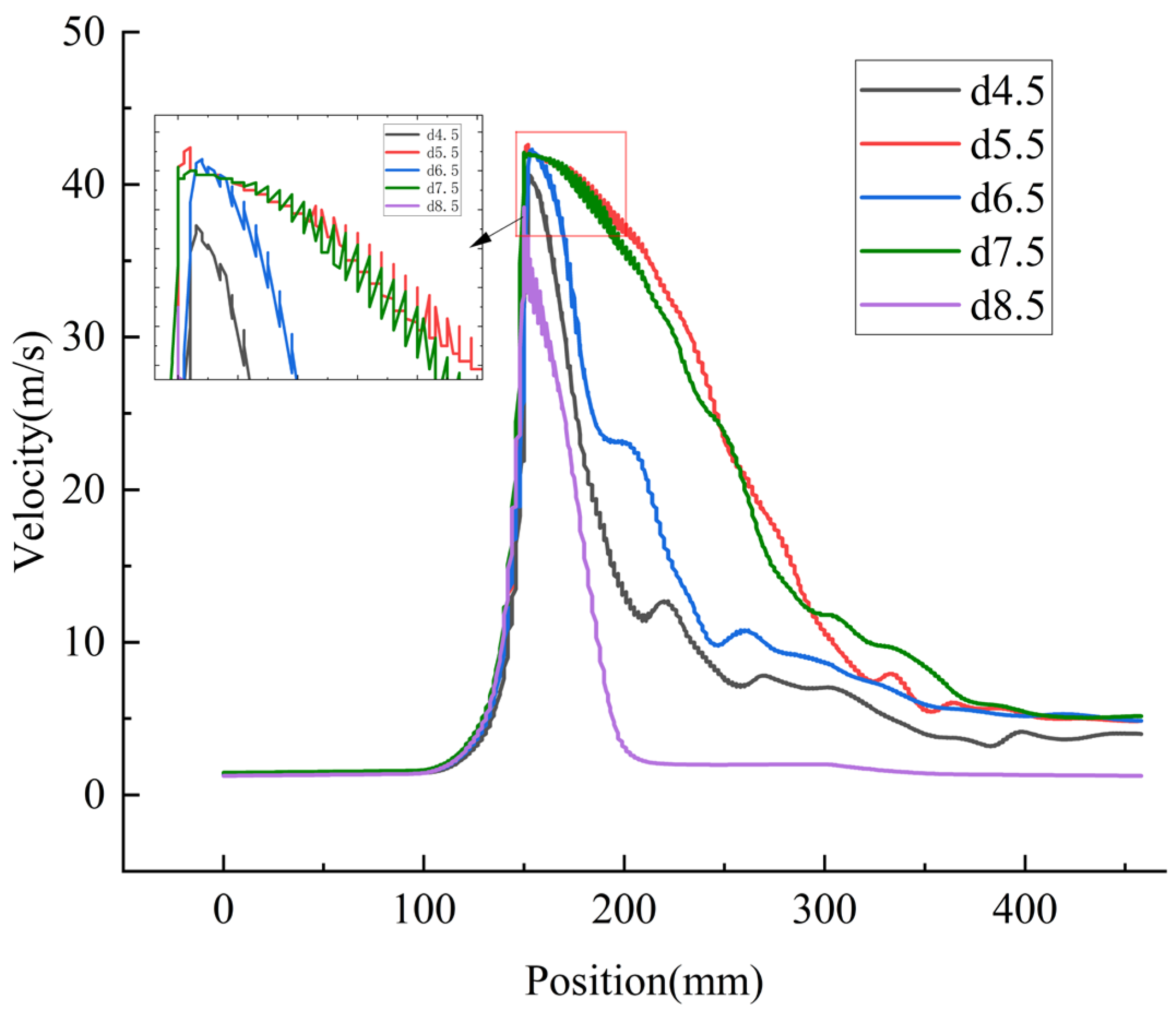

4.2. Influence of Nozzle-Throat Distance (d) on Ejector Performance

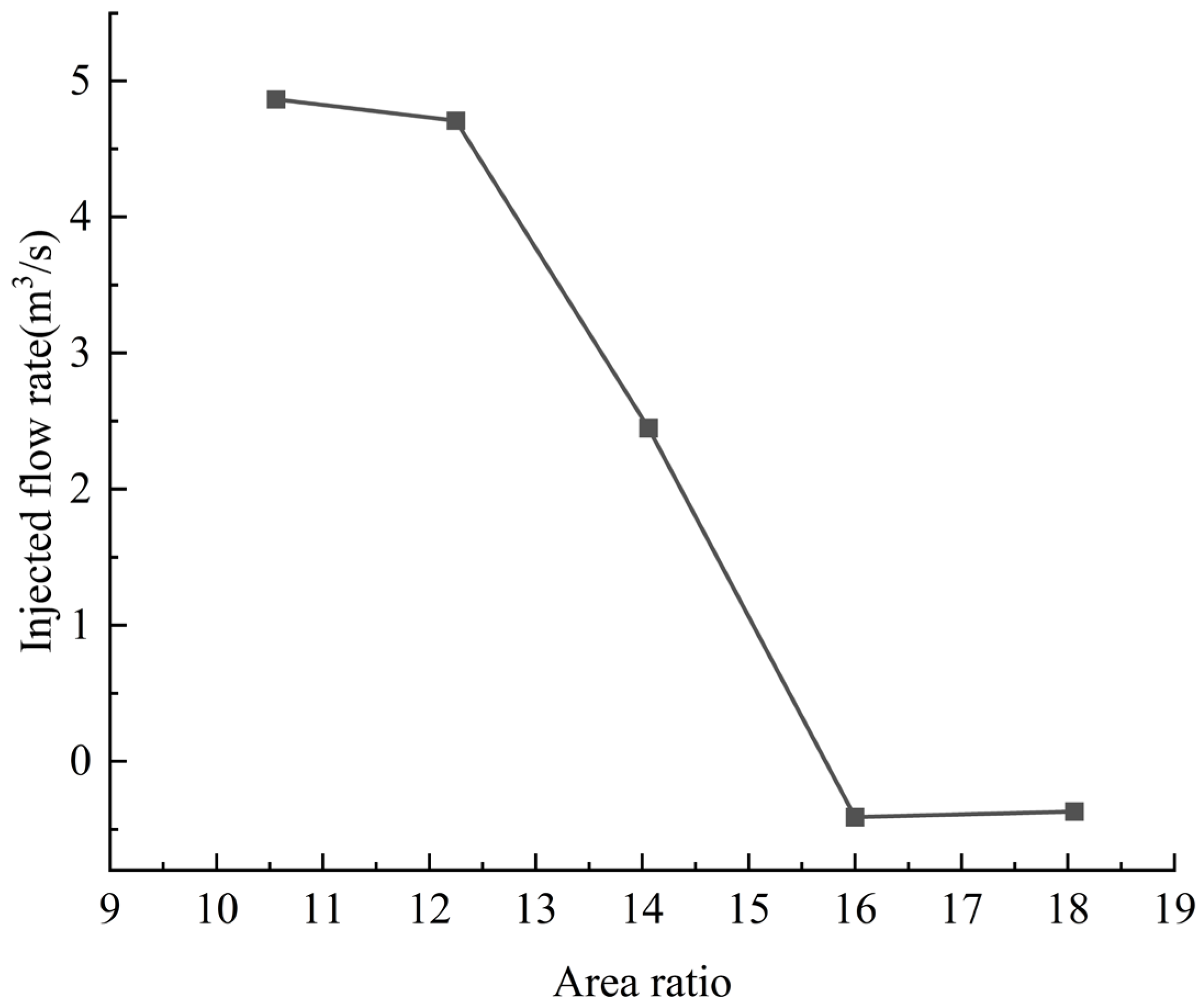

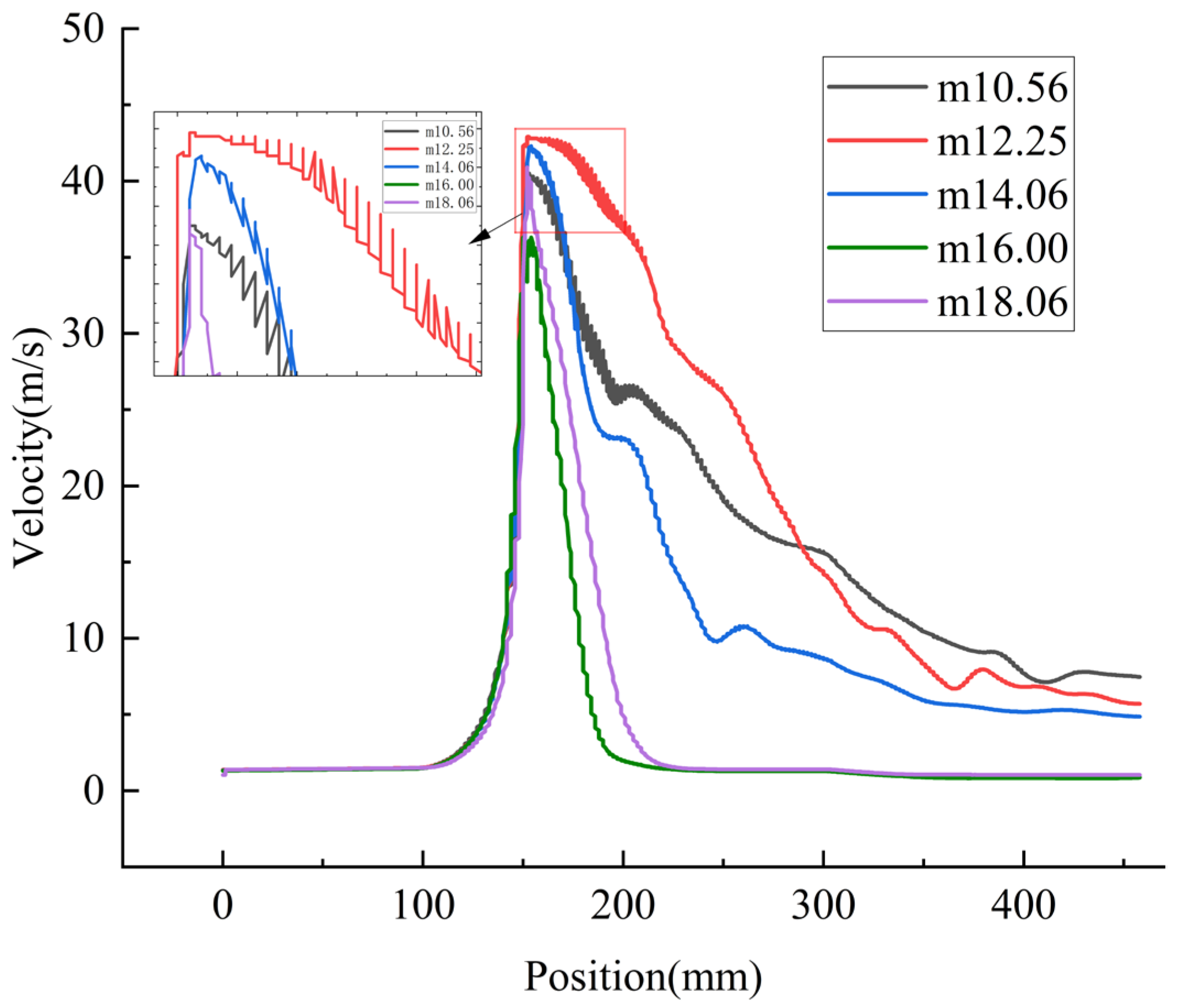

4.3. Influence of Area Ratio (m) on Ejector Performance

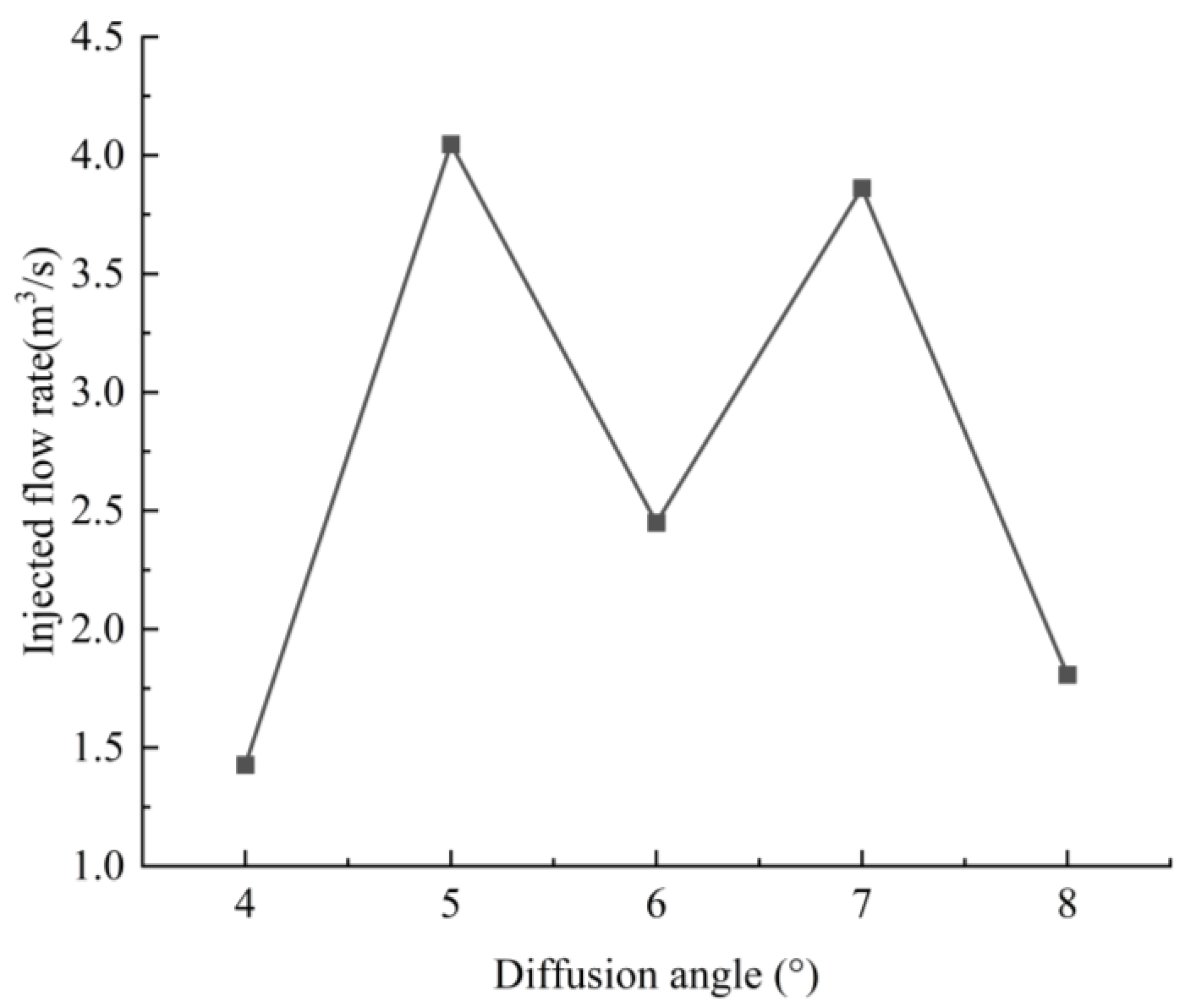

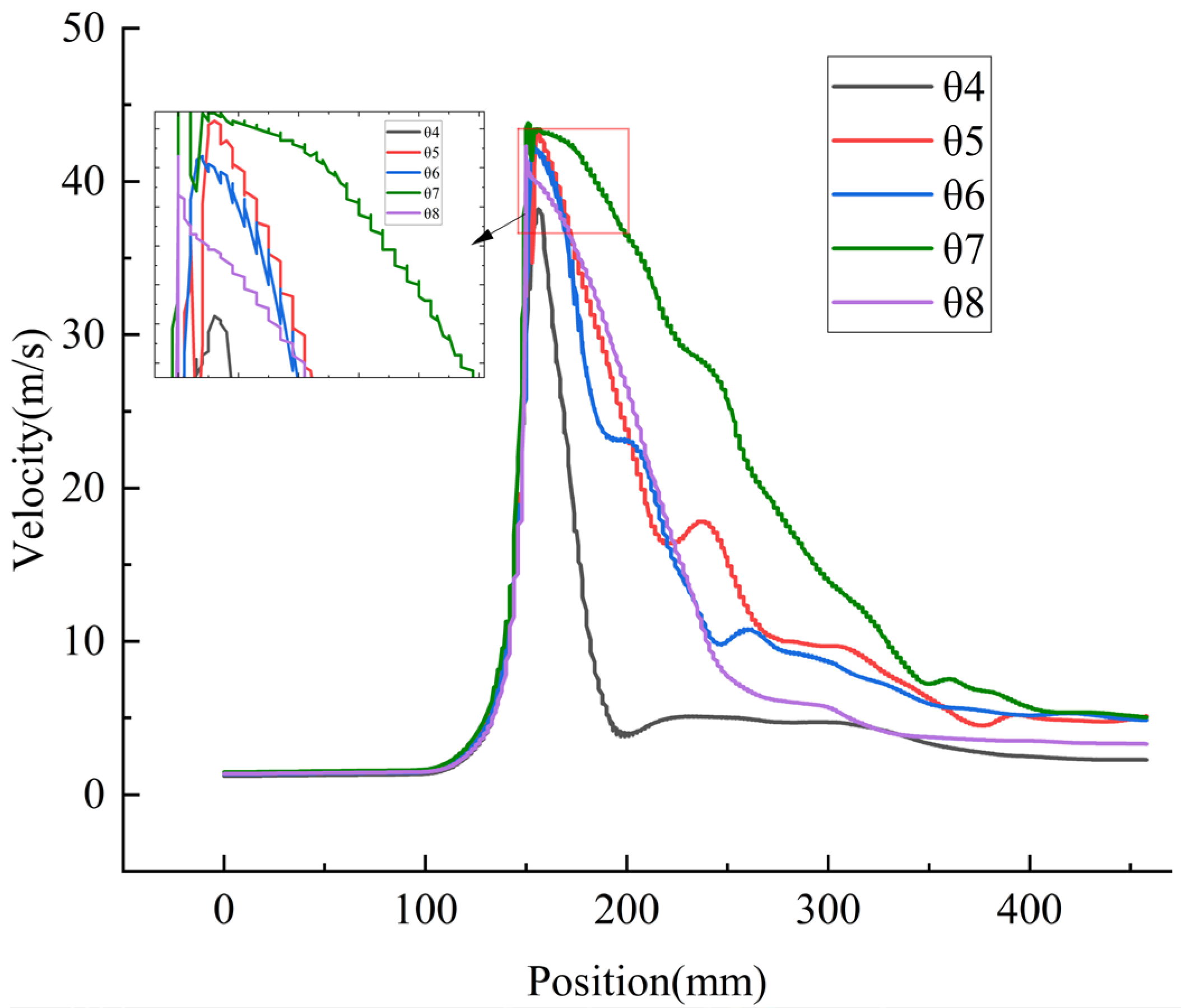

4.4. Influence of Diffuser Angle (θ) on Ejector Performance

5. Multi-Factor Analysis and Optimization Based on Response Surface Methodology

5.1. Design of Response Surface Optimization Methodology

5.2. Optimization Results

5.3. Analysis of Optimization Results

5.3.1. Analysis of Factor Significance

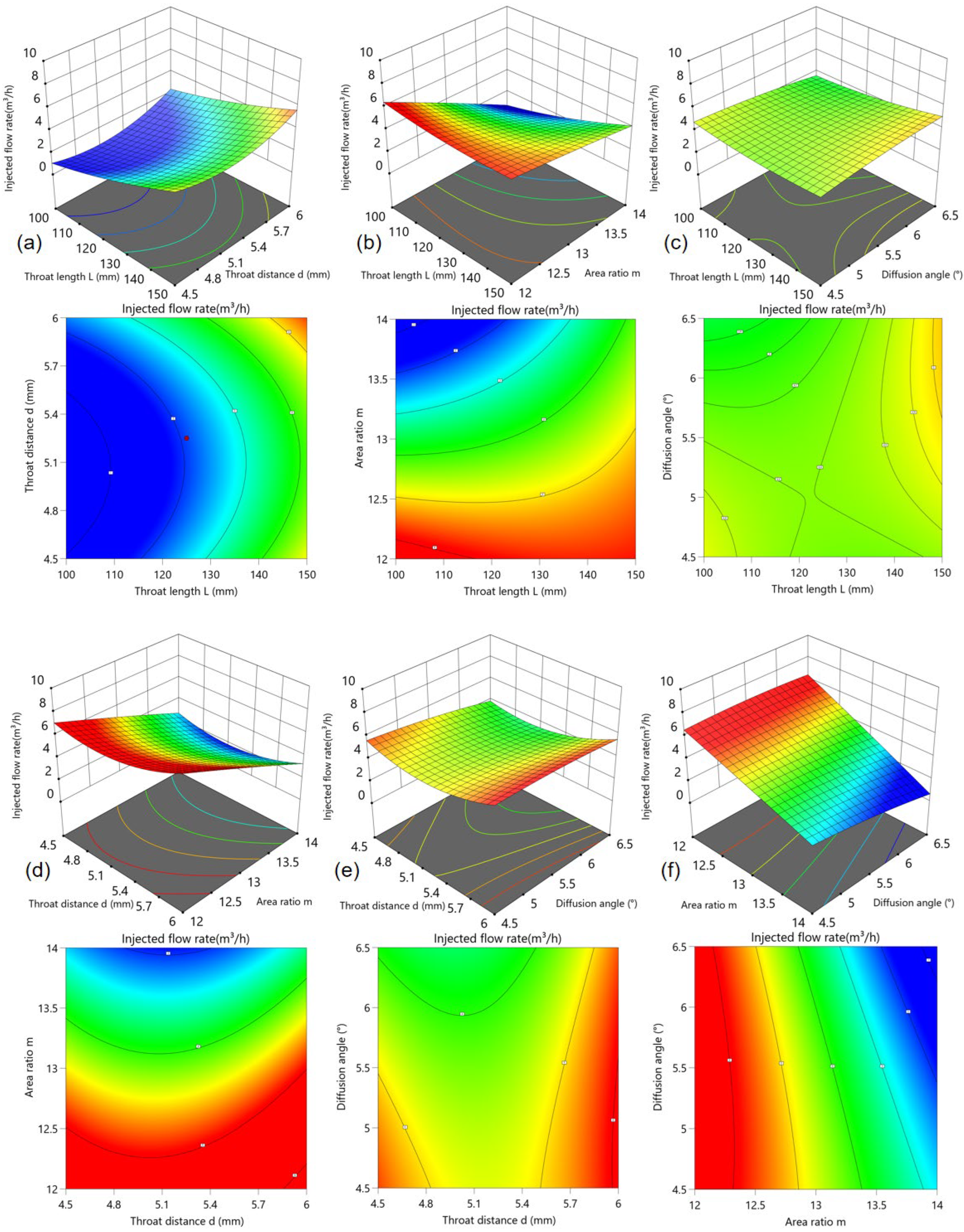

5.3.2. Analysis of the Interactive Effects of Factors on Suction Flow

5.4. Determination of the Optimal Combination Using Response Surface Methodology

5.5. Analysis of the Reasons for the Improvement in Jet Pump Suction Performance

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The four factors—throat length L, nozzle-throat distance d, area ratio m, and diffuser angle θ—all have a significant impact on the suction performance of the liquid–gas jet pump, and each has its own optimal value range. Through single-factor and combined multi-factor analysis, this paper determined the value ranges for the design factors as follows: throat length L in the interval [130 mm,150 mm]; throat distance d in the interval [5.4 mm,6 mm]; area ratio m in the interval [9,12.25]; and diffuser angle θ in the interval [5°, 6.5°].

- (2)

- The optimal parameter combination of the four factors was determined using response surface methodology, with the combined scheme as follows: nozzle-throat length L = 148.39 mm, throat distance d = 5.98 mm, area ratio m = 10.43, and diffuser angle θ = 5.25°. Based on this scheme, the structure parameters of the liquid–gas jet pump resulted in an increase in the driven medium flow rate to 7.129 m3/h, an increase of 4.679 m3/h, representing a 190.66% improvement over the original scheme, thereby achieving an enhancement in the suction performance of the liquid–gas jet pump.

- (3)

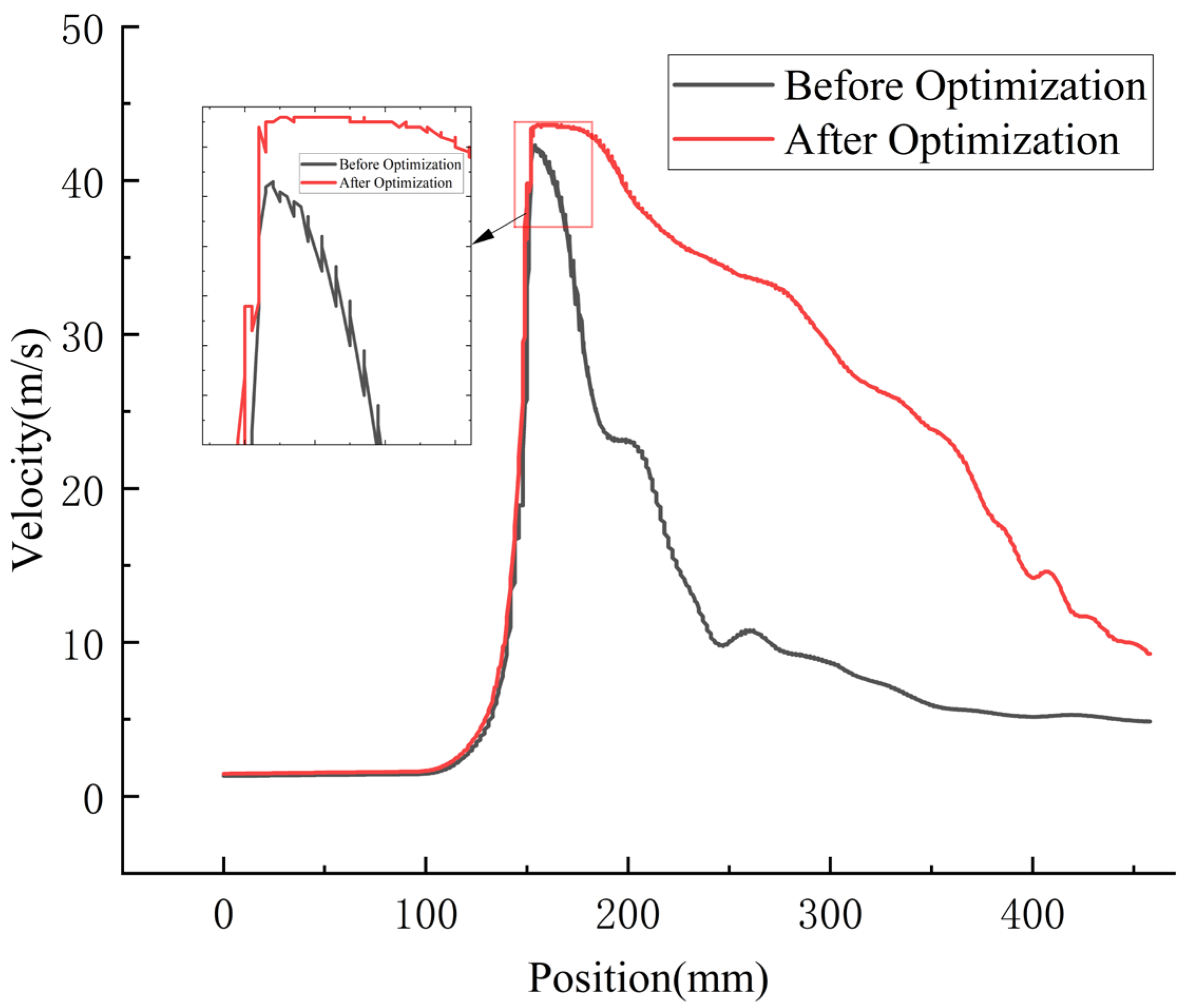

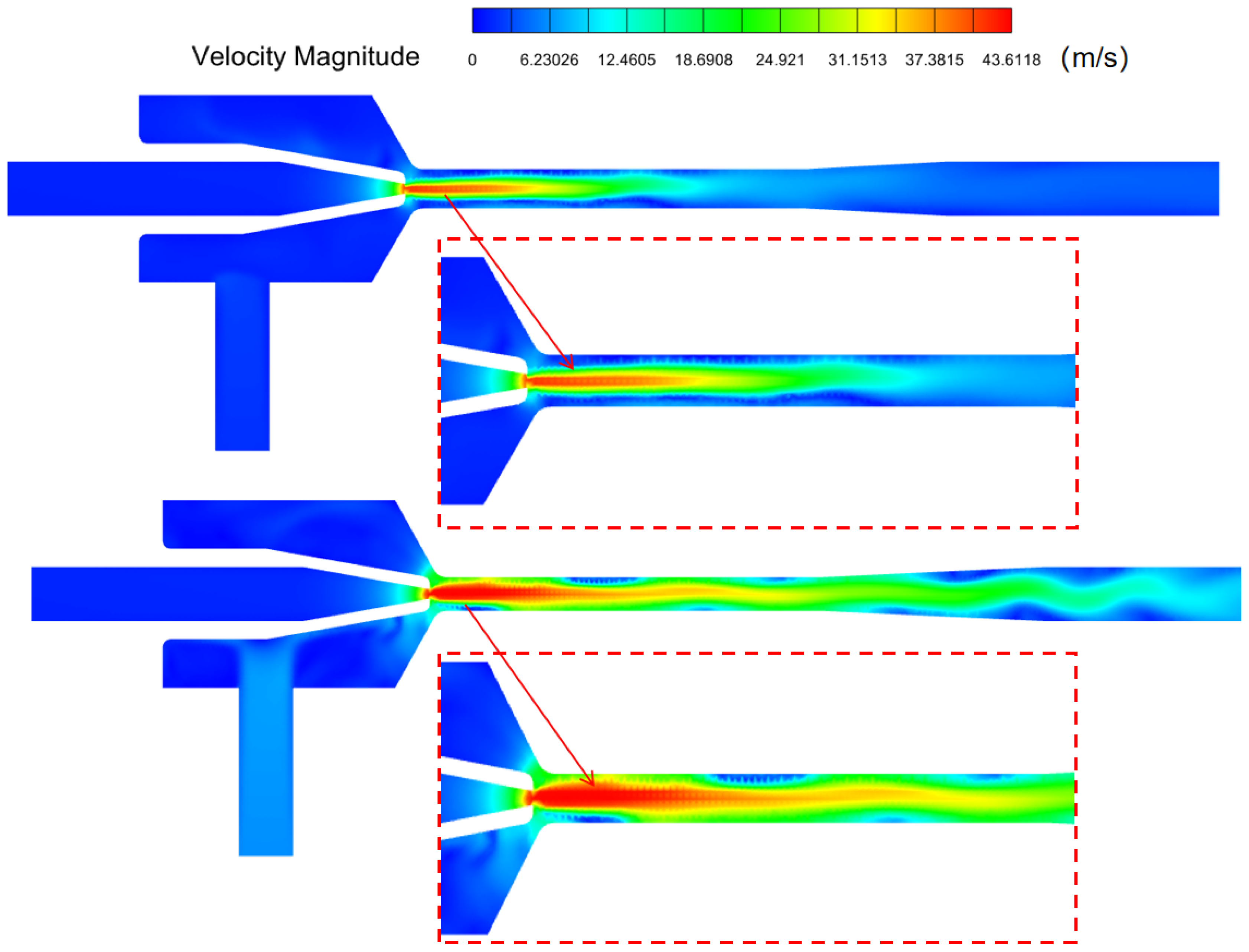

- The optimal scheme predicted by response surface methodology achieved a higher velocity peak at the nozzle exit, reaching 43.59 m/s, a 3.13% increase compared to the pre-optimization value. Additionally, it formed a sustained high-speed region of approximately 18 mm in the throat, which helps maintain fluid kinetic energy and reduce energy loss. The optimized scheme also improved fluid dynamic efficiency by reducing low-speed regions and increasing high-speed regions, enabling the jet pump to maintain velocity more effectively after ejection and decrease at a gentler trend, ultimately enhancing overall performance and efficiency.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, H.; Zou, D.; Yang, X.; Mou, J.; Zhou, Q.; Xu, M. Liquid–Gas Jet pump: A review. Energies 2022, 15, 6978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Chen, P.; Ma, R.; Qin, S. Numerical simulation of jet-pump performance using ANSYS Fluent. Chem. Eng. Mach. 2022, 49, 52–57, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Du, Z.; Chen, C.; Xu, G. Numerical investigation of spiral-flow effects on the performance of an annular jet pump. Mech. Sci. Technol. Aerosp. Eng. 2023, 42, 530–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Liu, B.; Zhang, F.; Diao, X.; Mo, R.; Shang, X.; Huang, F. Research on a negative-pressure jet device for rapid coal-powder removal in coal-bed-methane wells. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 2014, 43, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, L.; Xu, M. Influence of a control-ratio ring structure on the performance of an annular jet pump. Henan Sci. 2019, 37, 1584–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, B.; Xu, Y. Numerical simulation of the effect of central throat-nozzle distance on the performance of a compound jet pump. Water Resour. Hydropower Eng. 2019, 50, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, O.B.; Kim, M.K.; Kwon, H.C.; Bae, D.S. Two-dimensional numerical simulations on the performance of an annular jet pump. J. Vis. 2002, 5, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotak, V.; Pathrose, A.; Sengupta, S.; Gopalkrishnan, S.; Bhattacharya, S. Experimental investigation of jet pump performance used for high flow amplification in nuclear applications. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2023, 55, 3549–3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, K.; Sun, C.; Han, K.; Wang, C.; Sun, S.; Li, P.; Hu, J. Experimental/numerical investigation on the hydrodynamic and noise characteristics of pump-jet propulsion. Ocean Eng. 2024, 307, 117995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Gan, C.; Ning, P. Numerical study on throat tube inlet function of pulsed liquid jet pump. Adv. Mater. Res. 2012, 354, 650–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Mou, J.; Zhang, H.; Zou, D.; Yang, X.; Liu, X.; Qiu, Z.; Dong, B. Experimental study on performance of liquid-gas jet pump with square nozzle. Energies 2023, 16, 7951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Dai, Z.; Yang, D.; Fan, H. Investigation on optimization design of high-thrust-efficiency pump jet based on orthogonal method. Energies 2024, 17, 3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Weng, K.; Guo, C.; Chang, X.; Gu, L. Analysis of influence of duct geometrical parameters on pump jet propulsor hydrodynamic performance. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2020, 25, 640–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, R.H.; Montgomery, D.C.; Anderson-Cook, C.M. Response Surface Methodology: Process and Product Optimization Using Designed Experiments; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Baş, D.; Boyacı, İ.H. Modeling and optimization I: Usability of response surface methodology. J. Food Eng. 2007, 78, 935–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breig, S.J.M.; Luti, K.J.K. Response surface methodology: A review on its applications and challenges in microbial cultures. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 42, 2277–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadiyat, M.A.; Sopha, B.M.; Wibowo, B.S. Response surface methodology using observational data: A systematic review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 10663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenth, R.V. Response-surface methods in R., using RSM. J. Stat. Softw. 2009, 32, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X. Modern Pump Theory and Design; Aerospace Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.M.; Long, X.P.; Zhang, S.B.; Lu, X. Experiment on performance of adjustable jet pump. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2012; Volume 15, p. 062063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Li, H.; Yun, Q. The influence of oscillating jet on the liquid jet gas pump’s performance. In ASME Fluids Engineering Division Summer Meeting; ASME: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wu, Y.; Ning, P.; Gan, C. Numerical study on performance parameter of pulsed liquid jet pump. Adv. Mater. Res. 2012, 346, 793–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterhuis, J.P.; Timmer, M.A.G.; Buhler, S.; van der Meer, T.H.; Wilcox, D. On the performance and flow characteristics of jet pumps with multiple orifices. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2016, 139, 2732–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H. Theory and Application of Jet Technology; Wuhan University Press: Wuhan, China, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.H.; Zhu, J.W.; Zhao, X.F.; Qi, X.; Hong, J. Numerical optimization of duration time for the gravitational sedimentation process of produced water in oilfield. Desalination Water Treat. 2024, 319, 100467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nataraj, M.; Singh, R.R. Analyzing pump impeller for performance evaluation using RSM and CFD. Desalination Water Treat. 2014, 52, 6822–6831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.S.; Kumaraswamy, S.; Mani, A. Experimental investigations on a two-phase jet pump used in desalination systems. Desalination 2007, 204, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.S.; Mei, J.; Zhao, R.J.; Huang, J.; Jin, Y. Response surface method-based optimization of impeller of fluoroplastic two-phase flow centrifugal pump. J. Drain. Irrig. Mach. Eng. 2020, 38, 898–903, 921. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S.; Hu, X. Optimization of impeller of deep-sea mining pump for erosive wear reduction based on response surface methodology. Mar. Georesources Geotechnol. 2023, 41, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, S.; Vala, H.; Patel, V.K.; Patel, R. Performance improvement of the sanitary centrifugal pump through an integrated approach based on response surface methodology, multi-objective optimization and CFD. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2021, 43, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, M.N.; Muthukrishnan, N. Investigation on surface roughness in abrasive water-jet machining by the response surface method. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2014, 29, 1422–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Zhang, X.; Gao, Z.; Wu, J.; Gong, Y. Research on cooperative optimization of multiphase pump impeller and diffuser based on adaptive refined response surface method. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2022, 14, 168781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawadhi, K.; Alzuwayer, B.; Mohammad, T.A.; Buhemdi, M.H. Design and optimization of a centrifugal pump for slurry transport using the response surface method. Machines 2021, 9, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Xiao, R. Multiobjective optimization design of a pump-turbine impeller based on an inverse design using a combination optimization strategy. J. Fluids Eng. Trans. ASME 2014, 136, 014501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Tian, C.; Zhu, R.; Yin, J.; Wang, D. Optimization of water-jet pump based on the coupling of multi-parameter and multi-objective genetic algorithms. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2024, 46, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Li, C.; Gu, Z.; Wu, C.; Shao, S. Research on multi-objective optimisation design of pump-jet propulsion. Ocean Eng. 2025, 322, 120086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Chen, H.; Liu, Y.-W. Application of response surface methodology and desirability approach to investigate and optimize the jet pump in a thermoacoustic Stirling heat engine. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 127, 1005–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, H.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y. Multi-objective optimization design and simulation for fuel centrifugal pump. J. Propuls. Technol. 2021, 42, 666–674. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Yun, L. Investigation on the effect of slot pulse jet on centrifugal pump performance. Int. J. Fluid Mach. Syst. 2018, 11, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourbakhsh, A.; Safikhani, H.; Derakhshan, S. The comparison of multi-objective particle swarm optimization and NSGA II algorithm: Applications in centrifugal pumps. Eng. Optim. 2011, 43, 1095–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Structure Name | Dimension |

|---|---|

| Nozzle Diameter | 4 mm |

| Nozzle-throat Distance | 6.5 mm |

| Throat Length | 150 mm |

| Throat Diameter | 15 mm |

| Area Ratio (m) | 14.06 |

| Diffuser Length | 54.38 mm |

| Diffuser Angle | 6° |

| Mesh Configuration | Scheme 1 | Scheme 2 | Scheme 3 | Scheme 4 | Scheme 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Mesh Size/mm | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Total Mesh Count | 59,107 | 110,811 | 255,428 | 847,299 | 6,564,120 |

| Name | Specific Introduction |

|---|---|

| Experimental Object | Jet pump prototype consistent with the numerical simulation model; key parameters refer to Table; material is stainless steel |

| Driving Fluid System | High-pressure water pump (maximum flow rate 2 m3/h, maximum pressure 2.0 MPa), electromagnetic flowmeter (range 0–10 m3/h, accuracy ±0.5%) |

| Suction Fluid System | Air compressor (maximum pressure 1.0 MPa, flow rate 0–0.2 m3/min), gas mass flowmeter (range 0–0.3 m3/min, accuracy ±1.0%) |

| Pressure Measurement | Piezoelectric pressure sensor (range 0–2.5 MPa, accuracy ±0.2% FS) |

| Data Acquisition | Data acquisition card (sampling frequency 100 Hz) and supporting analysis software, which records flow rate and pressure data in real time |

| Factors | Throat Length L/mm | Nozzle-Throat Distance d/mm | Area Ratio m | Diffuser Angle θ/° | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levels | |||||

| − | 100 | 4.5 | 9 | 4.5 | |

| 0 | 125 | 5.25 | 10.56 | 5.5 | |

| + | 150 | 6 | 12.25 | 6.5 | |

| Experimental Plan | Factors | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Throat Length L/mm | Nozzle-Throat Distance d/mm | Area Ratio m | Diffuser Angle θ/° | |

| 1 | − | − | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | + | − | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | − | + | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | + | + | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | − | − |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | + | − |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | − | + |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | + | + |

| 9 | − | 0 | 0 | − |

| 10 | + | 0 | 0 | + |

| 11 | − | 0 | 0 | + |

| 12 | + | 0 | 0 | + |

| 13 | 0 | − | − | 0 |

| 14 | 0 | + | − | 0 |

| 15 | 0 | − | + | 0 |

| 16 | 0 | + | + | 0 |

| 17 | − | 0 | − | 0 |

| 18 | + | 0 | − | 0 |

| 19 | − | 0 | + | 0 |

| 20 | + | 0 | + | 0 |

| 21 | 0 | − | 0 | − |

| 22 | 0 | + | 0 | − |

| 23 | 0 | − | 0 | + |

| 24 | 0 | + | 0 | + |

| 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 26 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 27 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 28 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Experimental Plan | Factors | Injected Flow Rate /h | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Throat Length L/mm | Nozzle-Throat Distance d/mm | Area Ratio m | Diffuser Angle θ/° | ||

| 1 | − | − | 0 | 0 | 4.8772 |

| 2 | + | − | 0 | 0 | 5.8919 |

| 3 | − | + | 0 | 0 | 5.826 |

| 4 | + | + | 0 | 0 | 5.8819 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | − | − | 5.2021 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | + | − | 2.5139 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | − | + | 5.8321 |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | + | + | 1.9945 |

| 9 | − | 0 | 0 | − | 4.8628 |

| 10 | + | 0 | 0 | + | 2.6336 |

| 11 | − | 0 | 0 | + | 3.6857 |

| 12 | + | 0 | 0 | + | 5.0701 |

| 13 | 0 | − | − | 0 | 4.2519 |

| 14 | 0 | + | − | 0 | 4.7529 |

| 15 | 0 | − | + | 0 | 3.9246 |

| 16 | 0 | + | + | 0 | 4.3422 |

| 17 | − | 0 | − | 0 | 5.6564 |

| 18 | + | 0 | − | 0 | 5.2147 |

| 19 | − | 0 | + | 0 | 1.8018 |

| 20 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 4.4576 |

| 21 | 0 | − | 0 | − | 5.1776 |

| 22 | 0 | + | 0 | − | 5.4855 |

| 23 | 0 | − | 0 | + | 4.395 |

| 24 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 5.9097 |

| 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.3732 |

| 26 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.3501 |

| 27 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.3501 |

| 28 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.3501 |

| 29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.3501 |

| Coefficient | Value | Coefficient | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| +0.3055 | −0.1917 | ||

| +0.4005 | +0.3017 | ||

| −1.39 | −0.5025 | ||

| −0.1396 | +0.2862 | ||

| −0.1291 | +1.11 | ||

| +1.04 | −0.0574 | ||

| +0.4467 | −0.1790 |

| Factor | Sum of Squares | Degrees of Freedom | Mean Square | F-Value | p-Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Equation | 24.83 | 14 | 1.77 | 99.62 | <0.0001 | Significant |

| Throat Length (A) | 0.5147 | 1 | 0.5147 | 28.91 | 0.0007 | Significant |

| Nozzle-to-Throat Distance (B) | 0.9275 | 1 | 0.9275 | 52.1 | <0.0001 | Significant |

| Area Ratio (C) | 8.53 | 1 | 8.53 | 478.98 | <0.0001 | Significant |

| Diffuser Angle (D) | 0.1352 | 1 | 0.1352 | 7.6 | 0.0248 | Marginally significant |

| AB | 0.0377 | 1 | 0.0377 | 2.12 | 0.1836 | Non-significant |

| AC | 2.37 | 1 | 2.37 | 133.18 | <0.0001 | Significant |

| AD | 0.429 | 1 | 0.429 | 24.09 | 0.0012 | Significant |

| BC | 0.0546 | 1 | 0.0546 | 3.07 | 0.118 | Non-significant |

| BD | 0.3641 | 1 | 0.3641 | 20.45 | 0.0019 | Significant |

| CD | 0.5749 | 1 | 0.5749 | 32.29 | 0.0005 | Significant |

| 0.3697 | 1 | 0.3697 | 20.76 | 0.0019 | Significant | |

| 5.13 | 1 | 5.13 | 288.34 | <0.0001 | Significant | |

| 0.0124 | 1 | 0.0124 | 0.6942 | 0.4289 | Non-significant | |

| 0.1171 | 1 | 0.1171 | 6.58 | 0.0334 | Marginally significant | |

| Residuals | 0.1424 | 8 | 0.0178 | |||

| Error of Fit | 0.142 | 4 | 0.0355 | 332.63 | <0.0001 | |

| Pure Error | 0.0004 | 4 | 0.0001 | |||

| Total Sum | 24.97 | 22 |

| Reference Coefficient | Value |

|---|---|

| Mean | 4.60 |

| Coefficient of Variation (C.V.) | 2.90 |

| Coefficient of Determination (R2) | 0.9943 |

| Adjusted Coefficient of Determination (R2adj) | 0.9843 |

| Predicted Coefficient of Determination (R2pre) | 0.8585 |

| Adeq Precision | 38.1853 |

| Test Count | Simulation Result (m3/h) | Test Result (m3/h) | Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Time | 7.129 | 7.044 | 1.23 |

| Second Time | 7.128 | 6.997 | 1.89 |

| Third Time | 7.132 | 6.949 | 2.56 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Lu, H.; Tang, Y.; Chen, Z. Optimization Design of Liquid–Gas Jet Pump Based on RSM and CFD: A Comprehensive Analysis of the Optimization Mechanism. Water 2025, 17, 3423. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233423

Chen Z, Jiang Y, Lu H, Tang Y, Chen Z. Optimization Design of Liquid–Gas Jet Pump Based on RSM and CFD: A Comprehensive Analysis of the Optimization Mechanism. Water. 2025; 17(23):3423. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233423

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Zijun, Yue Jiang, Hongzhong Lu, Yong Tang, and Zhuo Chen. 2025. "Optimization Design of Liquid–Gas Jet Pump Based on RSM and CFD: A Comprehensive Analysis of the Optimization Mechanism" Water 17, no. 23: 3423. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233423

APA StyleChen, Z., Jiang, Y., Lu, H., Tang, Y., & Chen, Z. (2025). Optimization Design of Liquid–Gas Jet Pump Based on RSM and CFD: A Comprehensive Analysis of the Optimization Mechanism. Water, 17(23), 3423. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233423