Abstract

The remediation of contaminated sites necessitates robust and objective sustainability assessment frameworks to guide decision-making, yet prevailing methods often rely on qualitative or semi-quantitative metrics susceptible to subjectivity. This study establishes a comprehensive, fully quantitative evaluation system integrating environmental, economic, and social dimensions, comprising 13 objective indicators derived from Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), economic documentation, and publicly accessible social data—including nighttime light intensity, Point of Interest (POI) data, and social media sentiment analysis. The system employs the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) for weight assignment, ensuring methodological rigor and expert consensus. Validated through three case studies of remediated contaminated sites in Shandong Province, China, the framework reveals distinct sustainability profiles: Site 1 achieved the highest composite score (0.1030), demonstrating balanced performance across all dimensions, whereas Sites 2 and 3 yielded negative scores (−0.2490 and −0.1069, respectively), reflecting trade-offs between remediation efficiency, secondary environmental impacts, and socio-economic outcomes. The key findings underscore the dominance of environmental health indicators—notably Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs)—in overall weighting and highlight the critical influence of remediation technology selection on lifecycle impacts. The study validates the utility of a quantitative, multi-criteria approach in identifying optimal remediation strategies, facilitating cross-project comparability, and supporting the transition from cost-centric remediation toward value-driven, sustainable redevelopment.

1. Introduction

The remediation of contaminated sites represents a critical nexus of environmental stewardship, economic investment, and social responsibility within the broader framework of sustainable development []. As global industrial legacies leave a pervasive footprint of land pollution, the imperative to restore these sites is undeniable []. However, the ultimate goal has progressively shifted from mere contaminant removal or risk containment to achieving holistic sustainability—balancing environmental safety with economic viability and social equity []. This paradigm shift underscores the need for robust, multi-dimensional assessment tools capable of guiding decision-makers toward truly sustainable outcomes. Despite this recognized need, a significant gap persists in the practical evaluation of remediation projects, particularly in the quantitative and objective integration of all three sustainability pillars [].

The environmental dimension of remediation has been the most systematically addressed, largely through the standardized methodology of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) [,,,]. LCA provides a comprehensive, quantitative framework for evaluating the potential environmental impacts associated with all stages of a remediation project, from material production to construction and long-term monitoring. This allows for the identification of trade-offs, such as a reduction in primary contamination at the expense of secondary impacts like greenhouse gas emissions or resource depletion. Yet, the prevailing assessment frameworks often exhibit a critical asymmetry: while environmental impacts are measured with quantitative rigor, the economic and social dimensions frequently rely on qualitative or semi-quantitative metrics. As noted by Hou [], the perceptions of decision-makers regarding social and economic sustainability are often subjective. Pioneering initiatives, such as the sustainability assessment framework developed by the UK Sustainable Remediation Forum (SuRF-UK) [], have been instrumental in advocating for a holistic view. However, their reliance on expert scoring systems, while valuable, is inherently susceptible to individual and institutional biases. This subjectivity introduces significant uncertainty into economic and social indicators, complicating the comparative analysis of remediation alternatives and potentially undermining the credibility of the overall sustainability assessment []. Consequently, there is an urgent need to develop a fully quantitative, transparent, and reproducible evaluation framework that minimizes subjective influence and enhances the reliability and comparability of sustainability assessments.

In China, the context for this study, the concept of Green and Sustainable Remediation (GSR) has evolved from academic discourse to an increasingly operational priority []. Driven by national policies like the “Action Plan for Soil Pollution Prevention and Control” and growing public environmental consciousness, the remediation industry is rapidly maturing. The focus is gradually expanding beyond technical efficacy and cost to encompass broader life cycle impacts and long-term land value []. Research on sustainability assessment indicators within China has correspondingly flourished. Numerous studies have proposed integrated indicator systems, often drawing on international models like SuRF-UK and adapting them to local regulatory and geographical contexts. For instance, previous studies have developed multi-criteria systems incorporating environmental, economic, and social factors [,,]. Despite certain progress in existing studies on constructing sustainability evaluation systems, several limitations remain. For example, although an evaluation system proposed in one study covers 14 indicators across three categories (environment, society, and economy), it adopts an equal weighting method for some indicators. Moreover, the importance of indicators relies entirely on expert scoring, making it difficult to scientifically and comprehensively reflect the actual importance differences among various indicators []. Another proposed indicator system includes 20 indicators across five categories (technology, resources, environment, economy, and society), integrating both quantitative and qualitative indicators. The qualitative indicators are graded based on severity. However, the existence of qualitative indicators affects the systematicness and objectivity of the evaluation to a certain extent []. In addition, the construction of an indicator system must be targeted. For instance, Hou [] specifically incorporated the “soil quality” indicator into their evaluation system, precisely because the evaluation object was agricultural land. Nevertheless, a common limitation persists: the social indicators, such as “community acceptance” or “local development,” often remain qualitative or rely on small-sample surveys, which are difficult to standardize and scale. This reliance creates a bottleneck for objective, large-scale application and cross-project benchmarking. The challenge, therefore, lies not in recognizing the importance of these dimensions but in quantifying them with a level of objectivity comparable to that of LCA.

Simultaneously, the dawn of the big data era presents unprecedented opportunities to overcome these methodological hurdles. The proliferation of spatially explicit, publicly accessible digital data offers a novel lens through which to observe and measure socio-economic phenomena. Nighttime Light (NTL) data, derived from satellites such as NPP-VIIRS, has been robustly validated as a proxy for human activity, economic vitality, and urbanization intensity [,]. Similarly, Point of Interest (POI) data, cataloged by digital maps, provides a detailed inventory of public service facilities and commercial infrastructure, enabling a granular analysis of urban functionality and accessibility []. Furthermore, the vast repositories of user-generated content on social media platforms offer a real-time, organic barometer of public sentiment. Through Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques, particularly sentiment analysis tools like VADER [], it is possible to quantitatively gauge resident satisfaction and perceptions regarding local projects, bypassing the costs and biases associated with traditional surveys []. These data sources are objective, reproducible, and temporally dynamic, making them ideally suited for constructing quantitative social indicators that can be systematically integrated with environmental and economic metrics.

In this context, this study develops a fully quantitative sustainability assessment framework for contaminated site remediation, integrating LCA, economic analysis, and social big data analytics. By leveraging objective datasets and employing the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) for weight assignment, the framework aims to provide a transparent, reproducible, and scientifically rigorous tool for evaluating remediation projects. The innovation of this study lies in establishing a fully quantitative comprehensive sustainability evaluation system for remediation projects, covering environmental, social, and economic dimensions. Meanwhile, it incorporates open data such as nighttime light intensity, POI data, and social media sentiment analysis into the evaluation—an approach rarely documented in existing literature. Through application to three case studies in China, this research demonstrates the utility of the framework in identifying optimal remediation strategies, facilitating cross-project benchmarking, and supporting the transition from cost-centric remediation to value-driven, sustainable redevelopment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sustainability Assessment Framework

This study establishes a comprehensive evaluation index system for contaminated site remediation across environmental, economic, and social dimensions (Table 1). The system design balances index quantity and quality to avoid undermining comprehensiveness with too few indicators or introducing excessive complexity with too many. An oversimplified system may fail to capture overall remediation benefits [], while an excessive number of indices increases data acquisition difficulty and cost, compromises data accuracy, and dilutes the weight of core indicators during assignment []. Consistent with prevailing practice, the system incorporates 14 fully quantitative secondary indices—all derived from objective data—to eliminate subjective judgment and enhance objectivity, reproducibility, and cross-project comparability. This approach aligns with typical index counts in related studies [,,], and excludes qualitative or technical factors to maintain a focus on measurable outcomes.

Table 1.

Sustainable indicator setting.

- (1)

- In the environmental dimension, Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is adopted to comprehensively evaluate environmental impacts from the perspectives of resources, ecology, and health; as a widely used tool for assessing the environmental impacts of remediation projects, LCA enables cross-study and cross-application comparisons due to its standardized methodology [].

- (2)

- In the economic dimension, the focus is placed on cost–benefit and efficiency, where cost–benefit analysis serves as the core for evaluating the financial feasibility and overall value of remediation projects to support the optimization of resource allocation efficiency, while efficiency considerations are directly linked to the intensive utilization of time and resources—an efficient remediation process can substantially shorten project duration and reduce operational costs []; specifically, data on total remediation costs and project duration are directly extracted from project documents, and land values are retrievable through government public information channels. Owing to insurmountable data limitations and methodological challenges (detailed in Section S3.2), the indicator “Surrounding housing price premium” was excluded from the final evaluation framework despite its initial inclusion.

- (3)

- In the social dimension, the assessment framework draws on that of the UK Sustainable Remediation Forum (SuRF-UK) [] and is adapted in light of local data availability, and to avoid potential negative public opinion associated with questionnaire surveys, this study employs publicly accessible social information to reflect social impacts: nighttime light data is used to characterize regional activity levels as it objectively reflects the intensity of human activities and economic vitality []; based on the Geographic Information System (GIS) platform (ArcGIS 10.4.1), changes in public service facilities are analyzed via spatiotemporal comparisons using Point of Interest (POI) data []. A POI search was conducted within a 1 km radius of the site using Gaode Map (https://ditu.amap.com/, accessed on 5 October 2025) to identify the surrounding public service facilities. The search targeted common public management and service structures, including hospitals, schools, kindergartens, shopping malls, libraries, police stations, and parks; resident satisfaction is derived from social media sentiment analysis, which allows for real-time capture of public opinions []; and complaint volumes are counted through government hotlines and online complaint systems to directly reflect public concerns. These indicators comprehensively cover multiple social aspects, and their data acquisition methods feature objectivity, thereby avoiding subjectivity and biases that may arise from direct surveys.

Data availability has been fully considered in the construction of the indicator system. All indicators can be obtained through actual remediation project data and public information, and have been verified in three actual site cases. If individual data missing is encountered during a specific evaluation process, parameter estimation can be conducted by referring to monitoring data of similar sites or industry research reports, based on the core characteristics of the site (such as geographical location, pollutant properties, remediation scale, etc.).

2.2. Quantitative Methodology

2.2.1. LCA-Based Environmental Impact Assessment

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is employed to evaluate the environmental impacts of remediation projects, which typically includes four core steps: goal and scope definition, inventory analysis, impact assessment, and interpretation, and relevant literature has provided in-depth elaboration on these methods []. In the comprehensive evaluation index system constructed in this study, the environmental dimension aims to quantitatively define the environmental impacts generated throughout the entire life cycle of remediation projects. To ensure the comparability of assessment results across multiple projects, the evaluation boundary is uniformly defined to cover all main engineering processes (such as soil excavation, chemical treatment, and wastewater disposal) and ancillary activities (such as material transportation and infrastructure construction) of the remediation project from initiation to completion, excluding preliminary investigation and personnel transportation. Inventory analysis is conducted using actual data obtained from construction records, and the ReCiPe 2016 endpoint assessment method is adopted to avoid the issue of excessive midpoint indicators that are difficult to integrate.

2.2.2. Social Sustainability Assessment

In the development of social dimension indicators, data acquisition from official sources or established databases is relatively straightforward. However, constructing indicators such as regional activity levels (derived from nighttime light data) and resident satisfaction (based on sentiment analysis) requires specialized data processing methodologies.

- (1)

- Nighttime light data processing and analysis

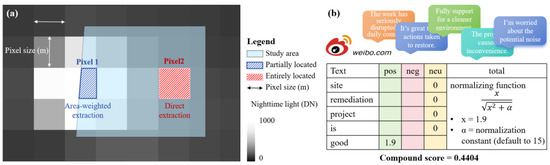

Nighttime light (NTL) remote sensing has emerged as a key indicator for monitoring socio-economic activities and energy consumption. NPP/VIIRS-based NTL data are extensively used in socio-economic research, including regional-scale assessment of atmospheric pollutant emissions [], analysis of residential electricity consumption [], and estimation of Gross National Product []. NTL data are stored in raster format, typically as GeoTIFF files, composed of pixels each containing a digital number (DN) value that represents radiance intensity per unit area at a given spatial resolution. This value reflects the nighttime brightness of the corresponding area. To analyze the data, the region of interest must first be delineated (e.g., a 1 km buffer around a site). All pixels within the boundary are extracted. For pixels partially outside the boundary, a weighted extraction based on the intersected area is applied. The average NTL intensity of the area is then calculated by summing the radiance values of all valid pixels and dividing by the total number of valid pixels (Figure 1a). This study utilizes annual nighttime light data of China from 2012 to 2021, with a spatial resolution of 0.0042°, derived from NPP-VIIRS satellite imagery and processed by Xu []. The dataset was obtained from the Environmental Science Data Platform.

Figure 1.

Date processing: (a) Extraction of raster cell data for nighttime light intensity in and around the study area; (b) sentiment analysis based on Valence Aware Dictionary for Sentiment Reasoning.

- (2)

- Acquisition and sentiment analysis of social media data

Sentiment analysis involves identifying, extracting, and processing subjective information from emotionally charged texts using natural language processing and text mining techniques. This study employs VADER (Valence Aware Dictionary for Sentiment Reasoning), a rule-based and lexicon-driven sentiment analysis tool recognized for its accessibility and low technical barriers []. Its lexicon, derived from established dictionaries, was further augmented to include social media-specific elements such as emoticons, acronyms, and slang. Each lexical entry is assigned a sentiment intensity value, which is adjusted based on punctuation, capitalization, and negation cues. VADER analyzes text by assigning weighted scores to sentiment-bearing words (e.g., “good,” “terrible”), intensifiers (e.g., “very,” “slightly”), and negations (e.g., “not,” “never”). These individual scores for positivity (pos), negativity (neg), and neutrality (neu) are then aggregated and normalized into a single, standardized compound score ranging from −1 (highly negative) to +1 (highly positive) [] (Figure 1b). VADER has been widely applied in social media sentiment studies across various disciplines, including aviation and consumer behavior [,,].

A keyword-based data collection strategy was implemented on the Weibo platform. Queries were constructed using keywords such as the site name and its prominent surrounding features to filter and extract large volumes of textual data. The retrieved posts include user evaluations, shared experiences, and references to the site’s contextual environment. All data were publicly available and no personally identifiable information was used. The collected textual data were cleaned to remove irrelevant elements such as URLs, and special characters []. Since VADER can directly analyze short texts, tokenization was not necessary during preprocessing. The cleaned texts were input into the VADER analyzer, and the resulting outputs were used to calculate the proportion of positive and negative sentiments for each contaminated site.

2.3. Comprehensive Evaluation (Weight Assignment)

This study establishes a three-tier evaluation index system structured along the “environment–economy–society” dimensions, comprising 3 environmental, 3 economic, and 6 social sub-indicators. The Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) is applied to assign weights. The AHP is a mature weight assignment method. Its core advantage lies in converting experts’ qualitative experience into computable quantitative data without requiring a large amount of sample data as the calculation basis. This method has been widely verified in multiple fields such as business management and public policy [,]. By decomposing the evaluation objective into a hierarchy (objective–criterion–index layers), the AHP converts subjective expert judgments into quantitative weights, effectively integrating qualitative and quantitative aspects in multi-criteria decision-making []. Furthermore, consistency testing ensures the logical coherence of expert judgments, reducing potential bias from subjective preferences. This approach is particularly suitable for weighting index systems that lack explicit data support.

Twenty experts were selected to participate in the weight assignment work, including 12 professors in the field of environmental science and engineering, 5 soil remediation engineers, and 3 environmental protection policy formulation and management staff. Referring to existing studies, the number of expert consultations for weight determination using the AHP is usually between 5 and 30 [,]. Some studies do not clearly indicate the specific number of experts, only presenting the final analysis results []. Combined with the actual implementation of this study, 20 experts can meet the application requirements of the analytic hierarchy process in general research scenarios.

To address the varying units of evaluation indicators, standardization is applied to transform all values into dimensionless scores within the [0,1] interval, thereby eliminating unit-induced bias in the composite scoring process. This study employs the min–max normalization method. Let x1, x2, …, xm represent the values of a given indicator across m restoration sites, with max(X) and min(X) denoting the maximum and minimum values, respectively. The standardized value x’ for the i-th site is computed using Equation (1) for positive indicators (where higher values indicate better performance), and Equation (2) for negative indicators. In cases where all values of an indicator are identical (i.e., max(X) = min(X)), all standardized values for that indicator are assigned 1 (for positive indicators) or −1 (for negative indicators) to prevent division by zero.

The AHP is implemented through the following key steps, with further methodological details available in the established literature [,]. Forming the judgment matrix: Experts perform pairwise comparisons of indicators within the same hierarchical level with respect to their parent objective, using a 1–9 scale to form the judgment matrix A = (aij)n×n, where n denotes the number of indicators. Each entry aij reflects the relative importance of indicator i over indicator j, adhering to the constraints aij = 1/aji and aii = 1. Weight calculation: The eigenvector corresponding to the maximum eigenvalue λmax of matrix A is computed and normalized to derive the weight vector W = (w1, w2, …, wn), such that = 1. This vector represents the relative weights of the indicators at the current level. Consistency verification: The consistency index is calculated as CI = (λmax − n)/(n − 1). The consistency ratio is then obtained as CR = CI/RI, where RI is the random index. If CR < 0.10, the matrix is considered consistent. Otherwise, the judgment matrix must be revised. Synthesis of global weights: The total weights of the sub-indicators relative to the goal layer are synthesized by multiplying the sub-indicator weights by the indicator weights, ultimately forming a complete system of indicator weights. The comprehensive evaluation score for each remediation site is computed via weighted summation, combining the standardized sub-indicator values with their corresponding total weights.

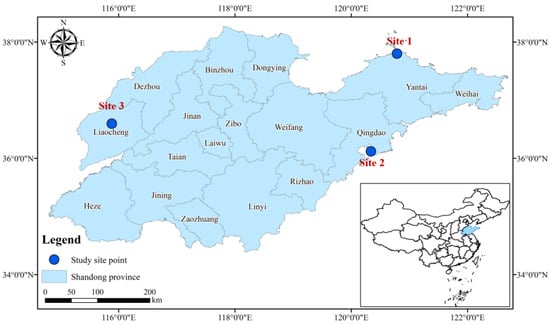

2.4. Demonstration Case Description

To validate the evaluation index system established in this study, three contaminated sites in Shandong Province that have completed remediation, restoration, and reuse were selected for the application of the proposed indices (Figure 2). All the remediation projects of these contaminated sites were carried out in 2018, and the original sites were all chemical enterprises. After the enterprises were closed and relocated, all the sites were redeveloped into non-industrial construction land. Relevant information about the sites is publicly available and retrievable. Images of the site prior to remediation and following redevelopment and reuse are provided in Figure S1. Materials and energy consumed during remediation activities are summarized in Tables S1–S3.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the geographical location of the study sites.

Site 1 is located in Yantai City, covering an area of 260,000 m2. Historically used for dye production, the site exhibited soil contamination primarily by heavy metals and VOCs, with a maximum contamination depth of 5 m. The estimated contaminated soil volumes were 35,000 m3 for heavy metals and 1600 m3 for VOCs. Remediation of heavy metal-contaminated soil was conducted using solidification/stabilization technology, while VOC-contaminated soil was treated via ambient temperature desorption. Additionally, 20,000 m3 of heavy metal-contaminated groundwater was remediated using pump-and-treat technology with a combination of flocculation-precipitation and activated carbon adsorption. The remediation project was completed within 200 days, with a total cost of 55 million CNY. Following remediation, the site is planned for redevelopment as residential land. Redevelopment according to the new land use plan began in the second year following the shutdown and demolition of the industrial enterprises.

Site 2 is situated in Qingdao City, with an area of 190,000 m2. Previous operations involved dye manufacturing, resulting in soil contamination by heavy metals and SVOCs up to a depth of 8 m. The total contaminated soil volume reached 120,000 m3, comprising 100,000 m3 contaminated by heavy metals and 33,000 m3 by SVOCs. Heavy metal-contaminated soil was treated with solidification/stabilization, while organic contamination was addressed through chemical oxidation. Excavation and ex situ treatment were applied to contaminated soil above 4 m, whereas in situ chemical oxidation was used for deeper contamination. The area of groundwater contamination is approximately 9900 m2, with a remediation depth of 8 m. Groundwater was treated ex situ using Fenton’s reagent after extraction. The project took 120 days to complete, with a total cost of 90 million CNY. The site is slated for future use as residential and educational land. After the industrial enterprises were dismantled in 2016, the site lay largely untouched for four years before residential construction commenced in 2020.

Site 3 is located in Liaocheng City, spanning 200,000 m2. The site was previously used for sulfuric acid production. Soil contamination was primarily caused by heavy metals, concentrated within the upper 2 m, with a total volume of 148,000 m3. Additionally, groundwater contamination by arsenic affected an area of 20,000 m2. The contaminated soil was remediated using solidification/stabilization, and long-term groundwater monitoring is being conducted through five monitoring wells. The remediation project lasted 180 days and incurred a total cost of 80 million CNY. The future planned land use for this site is public administration and public services. Redevelopment according to the new land use plan commenced concurrently in the same year the on-site enterprises were demolished.

3. Results and Discussion

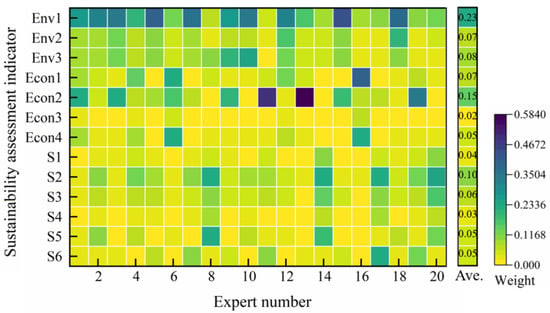

3.1. Weighting of Indicators in the Comprehensive Evaluation System

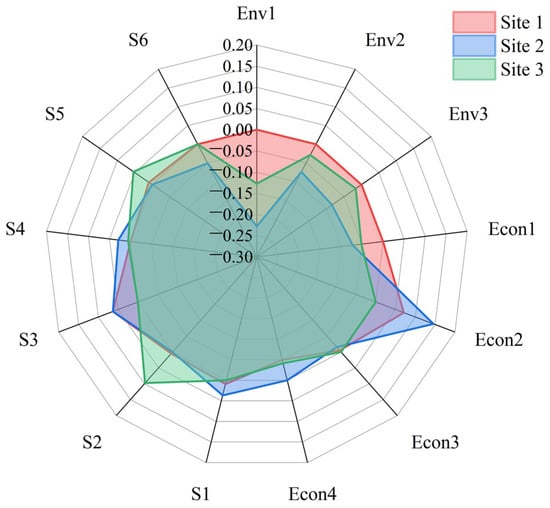

This study calculated the indicator weights for the comprehensive evaluation system of a brownfield regeneration project using the AHP, based on judgments from 20 experts. The analytical results reveal the relative importance consensus among the expert group for each dimension and specific indicator (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Results of the weight analysis of sustainable assessment indicators by experts using the Analytic Hierarchy Process.

At the macro-dimensional level, Environmental Benefits (Env, aggregate weight 38.56%) were assigned the highest overall importance, significantly surpassing Economic Benefits (Econ, aggregate weight 28.28%) and Social Benefits (S, aggregate weight 33.16%). This outcome indicates that in projects such as brownfield regeneration, which involve ecological restoration and public health, experts prioritize their long-term impacts on the environment and human health. Among these, “Env1 Disability-adjusted life years” emerged as the most important single indicator globally, with a weight of 22.79%, underscoring the paramount importance of the project’s impact on public health, far exceeding other environmental indicators (Env2 and Env3 both around 7.3%).

Within the Economic Benefits dimension, the weight for Land value appreciation (Econ2, 0.1457) is approximately double that of Direct remediation cost (Econ1, 0.0720) and substantially higher than the other two indicators. This finding strongly suggests that within the expert evaluation framework, the long-term economic benefits and asset appreciation potential generated by the remediation project are considered more important than the initial direct investment costs. This reflects a notable trend in contemporary environmental economic decision-making: a shift from a purely “cost-control” mindset towards a strategic perspective pursuing “value creation.” Experts evidently believe that a successful remediation can offset or even surpass its initial governance investment by significantly enhancing the land value, thereby achieving a net positive benefit for the project.

The Social Benefits dimension received an aggregate weight comparable to Environmental Benefits, but its internal weight distribution is relatively dispersed. Among these, “S2 Regional activity level” (9.78%) and “S3 Public service facility improvement” (6.32%) are the two highest-weighted social indicators, indicating that experts place great importance on the project’s role in stimulating regional vitality and functionality. In contrast, “S1 Official announcement frequency” (3.67%) has the lowest weight, reflecting that expert assessment focuses more on substantive social outcomes rather than promotional efforts. Furthermore, the positive indicator “S5 Resident satisfaction” (5.39%) and the negative indicator “S6 Complaint volume” (5.07%) have similar weights, suggesting that combining these two in subsequent evaluations could provide a more comprehensive measure of public feedback.

The results of this study show that the weight of environmental dimension indicators is 0.39, the weight of social dimension indicators is 0.33, and the weight of economic dimension indicators is 0.28. Some research conclusions are consistent with this study. For example, one study pointed out that the environmental dimension indicators have the highest weight, reaching 0.513, accounting for more than half of the total weight []. Another study did not distinguish the weights of social, economic, and environmental indicators but adopted an equal weight setting method—either unifying the weights of the three to 0.33 [] or regarding the weight of each dimension as 1 []. At the level of specific indicators in the economic dimension, some studies treat the importance of remediation costs and land value appreciation equally [], but the results of this study indicate that the importance of land value appreciation is twice that of remediation costs. It is worth noting that expert opinions may vary in different periods, which may be affected by the policy orientation of the current period. Considering that different regions may have differences in industrial structure, policy requirements, etc., in practical applications, each region can adjust the indicator weights in a targeted manner based on the evaluation index system of this study and combined with local actual conditions.

In summary, the weight analysis in this study establishes an evaluation value orientation for brownfield regeneration projects that prioritizes environmental health and substantive social outcomes while also emphasizing the consideration of time-related costs. When planning projects and comparing alternatives, decision-makers should prioritize the effectiveness of measures in reducing “Disability-adjusted life years” and focus on shortening the remediation duration. Simultaneously, the assessment of social benefits should transcend formalism, concentrating on whether the project genuinely enhances regional vitality, improves supporting facilities, and gains public support. This weight system provides a scientific basis for decision-making in the subsequent comprehensive performance scoring of multiple project alternatives. Additionally, despite individual cognitive differences on some indicators, the final composite weights, synthesized and averaged from the group’s opinions, demonstrate a relatively balanced and concentrated distribution. This validates the effectiveness of the AHP method in integrating diverse expert opinions and mitigating the extreme influence of individual preferences []. However, the evaluation framework and weight results constructed in this study focus on verifying the universal methodology. Considering potential differences in industrial structure, policy requirements, and other aspects across regions, local authorities can, based on the evaluation index system of this study, make targeted adjustments to indicator weights in combination with local actual conditions during practical application.

3.2. Case Analysis Results

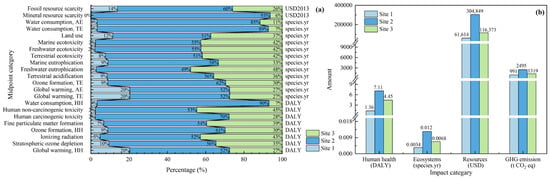

3.2.1. Environmental Dimension

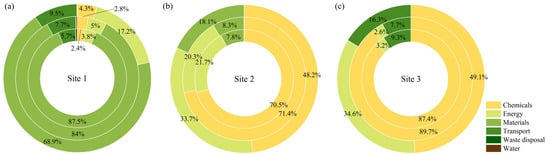

This study applied the ReCiPe methodology to systematically evaluate and compare the life cycle environmental impacts of three representative contaminated site remediation projects. The assessment results, analyzed across midpoint indicators, endpoint indicators, and weighted total scores, reveal significant differences in environmental benefits and costs among the different remediation strategies (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Life cycle impact assessment results for three site remediation projects: (a) midpoint categories, (b) endpoint categories and greenhouse gas emissions (HH: human health; TE: terrestrial ecosystem; AW: aquatic ecosystems in (a)).

At the midpoint level, resource consumption, human toxicity, and greenhouse gas emissions were identified as the dominant impact categories. The environmental impact profiles of the three sites exhibited distinct differences (Figure 4a). Site 2 demonstrated the highest environmental impact values for the vast majority of midpoint indicators. Its greenhouse gas emissions (2495 t CO2 eq), alongside impacts from global warming-human health, human carcinogenic toxicity, human non-carcinogenic toxicity, fossil resource scarcity, and mineral resource scarcity, were 2.5, 2.6, 29.8, 21.9, 4.3, and 429 times greater than those of Site 1, respectively. These findings are highly consistent with the project characteristics of Site 2, which featured the largest contamination volume, the greatest remediation depth, and the large-scale implementation of energy- and material-intensive technologies, such as chemical oxidation and pump-and-treat based on Fenton’s reagent. These processes require substantial electricity and chemical inputs, directly leading to elevated carbon emissions, resource consumption, and secondary pollutant releases []. In contrast, Site 1 exhibited the lowest greenhouse gas emissions (991 t CO2 eq) and overall environmental impact, attributable to its relatively smaller contamination volume and the use of low-energy consumption technology, specifically ambient temperature desorption for VOC treatment.

Regarding endpoint impacts and total weighted scores, Site 2 incurred the highest environmental cost (Figure 4b). Endpoint indicators aggregate various midpoint impacts into damage values for three main areas of protection. The results indicate that Site 2 substantially exceeded the other sites in all three damage categories and in the total damage score. Its total damage score (128.81 kPt) was 5.1 and 1.6 times higher than those of Site 1 and Site 3, respectively. Specifically, for damage to human health, the high value for Site 2 was driven not only by fine particulate matter formation and human toxicity but also significantly by the human health impacts associated with its substantial greenhouse gas emissions. Concerning resource consumption, the immense damage attributed to Site 2 was almost entirely contributed by mineral and fossil resource scarcity, directly linked to its high energy- and material-consumption technology choices, while the consumption of fossil fuels itself is a primary source of its greenhouse gas emissions.

Source tracing analysis of the life cycle endpoint impacts for the three remediation projects indicated pronounced differences in their primary environmental impact sources, profoundly reflecting the dominant role of remediation technology selection and project scale. For Site 1, environmental impacts (particularly in the human health category) primarily originated from the extensive use of quicklime (contributing 18.18 kPt), directly associated with the large-scale implementation of solidification/stabilization technology []; additionally, diesel and electricity consumption, as well as activated carbon usage, constituted significant contributions (Figure 5a). Site 2 exhibited the most prominent overall impact, with its overwhelming influence sources being the production and transportation of chemical oxidants. Among these, hydrogen peroxide (56.94 kPt) and ferrous sulfate (23.80 kPt) contributed substantially to human health damage, clearly identifying the Fenton’s reagent chemical oxidation process as the primary source of environmental cost; concurrently, material transport (21.84 kPt) and activated carbon usage (4.31 kPt) also generated significant impacts (Figure 5b). The impact profile of Site 3 was relatively concentrated, with its core source similarly being the iron-based materials required for the solidification/stabilization process (67.21 kPt), while the impacts from diesel consumption and material transport were comparatively secondary (Figure 5c).

Figure 5.

Environmental impact contributions of main engineering input categories to endpoint environmental impact categories for Sites 1 (a), Site 2 (b), and Site 3 (c). The inner, middle, and outer rings, respectively, represent the contribution ratios to Ecosystems, Human health, and Resources.

In summary, the environmental burden of the remediation projects is not uniformly distributed but is highly concentrated within the life cycle chains of a few critical materials (e.g., chemical oxidants, stabilization agents) and energy sources (e.g., diesel). This finding provides a basis for selecting targeted strategies to reduce the environmental footprint of remediation engineering, such as adopting cleaner energy sources and optimizing chemical dosage [,].

3.2.2. Economic Dimension

Significant disparities exist in land price levels among the three cities where the study sites are located, with the overall distribution pattern showing the highest value in the city of Site 2 and the lowest in the city of Site 3. As of the first quarter of 2024, the total estimated land values for the three sites were approximately 1846.26 million CNY, 2417.58 million CNY, and 861.80 million CNY, respectively (Figure S2). These figures represent multiples of 16.58, 19.39, and 10.16 times their values from the first quarter of 2018, when all sites were designated as industrial land. Although Site 1 has the largest area, the total land value of Site 2 significantly exceeds the others due to the higher land prices in its location. Conversely, Site 3 has the lowest total valuation, which can be attributed to its zoning for administrative and service use—a land use category typically associated with a lower average price compared to residential and commercial land.

The numerical values of the three remaining economic indicators can be directly obtained from the project documentation (Table 2). The differences in these directly acquired economic indicators, which are closely related to the site remediation projects, reflect the distinct pollution characteristics and remediation strategies of the different sites. Although Site 2 has a higher remediation cost and a longer idle duration, its shorter remediation duration indicates a certain advantage in remediation efficiency. In contrast, Sites 1 and 3 demonstrate better economic performance in terms of remediation cost and idle duration, but their remediation durations are relatively longer. These findings provide significant references for future site remediation projects, especially in the selection of remediation technologies and the assessment of project economic viability.

Table 2.

Statistics of comprehensive environmental impact assessment indicators for the three remediation projects.

3.2.3. Social Dimension

This study utilizes annual nighttime light data of China from 2012 to 2021, with a spatial resolution of 0.0042° (≈467 m), derived from NPP-VIIRS satellite imagery and processed by Xu []. The dataset was obtained from the Environmental Science Data Platform. According to the data provided, the total number of pixels for Site 1 was 33.10 in 2017 and 33.06 in 2021; for Site 2, it was 23.46 in 2017 and 26.23 in 2021; and for Site 3, it was 31.11 in 2017 and 31.84 in 2021 (Figure S3). The changes in the number of pixels reflect the subtle changes in the spatial coverage of the study area in different years, which may be related to changes in land use or data accuracy. There are the changes in nighttime light (NTL) intensity before and after the redevelopment of the study sites. The results indicate an increasing trend in NTL across all three sites, albeit with distinct characteristics. Site 3 (rural area) exhibited the lowest baseline luminosity but the most dramatic rate of increase, with its mean Digital Number (DN) surging from 0.98 to 3.60, a remarkable increase of 267.82% (Table 3). This suggests that its conversion into public service facilities has triggered a transformative, from-scratch emergence of nighttime economic activity. In contrast, Site 1 and Site 2 (both located in urban centers), which already had high initial light intensity, saw their mean DN values rise to 20.55 and 25.06, representing increases of 24.59% and 12.40%, respectively. This sustained growth is likely associated with continued prosperity driven by the change in land use (e.g., from industrial to residential/commercial) and the accompanying improvement in supporting infrastructure and resident nocturnal activity. Overall, the NTL data effectively reveal the differentiated socio-economic impacts of land redevelopment across different locational contexts.

Table 3.

Change in nighttime light intensity at the study site.

Based on searches conducted via official government websites and other public channels, relevant announcements related to site investigation, risk assessment, remediation design, performance evaluation, planning, and progress were retrieved. The number of records obtained is summarized in Table 2. The publicly available information for Site 2 is comprehensive, essentially covering the entire process from initial investigation through remediation to redevelopment. In contrast, the disclosed materials for Sites 1 and 3 primarily consist of remediation performance evaluation reports. POI-based analysis further revealed that the improvement in public service facilities around Site 2 is more substantial, both in terms of quantity and variety. In comparison, due to its rural location, only one essential type of public service facility—a hospital—was found within a 1 km radius of Site 3 (Figures S4–S6). No adverse public feedback has been documented regarding the remediation and redevelopment of Site 1 and Site 3. The development of Site 2 for residential purposes has experienced schedule delays, deviating from the planned timeline. This deviation has resulted in one registered public complaint.

3.2.4. Comprehensive Evaluation

This study constructed a comprehensive evaluation system encompassing environmental, economic, and social dimensions. Based on AHP-derived weights and standardized data, a quantitative assessment of the comprehensive performance of three candidate sites was conducted. The final composite scores clearly revealed the relative merits of the sites, with the ranking as follows: Site 1 (0.1030) > Site 3 (−0.1069) > Site 2 (−0.2490) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Comprehensive assessment scores of the three sites based on the sustainability evaluation indicator system developed in this study.

The composite scores exhibit significant hierarchical differentiation. Site 1, being the only site with a positive score, demonstrates performance substantially superior to the other two. This result clearly indicates that Site 1 represents the optimal solution for achieving the synergistic development of environmental, economic, and social benefits. Its success likely stems from a balanced and efficient development model: it effectively controlled environmental health risks during the remediation phase (e.g., lowest DALYs value) and successfully unlocked the land’s economic value (e.g., significant land value appreciation) and enhanced social well-being (e.g., improved public service facilities) during the reuse phase. The case of Site 1 proves that the redevelopment of contaminated sites can fully transform from a “burden” into a regional “asset.”

The composite scores for both Site 2 and Site 3 are negative, indicating that the overall benefits of these two redevelopment projects failed to fully offset the lifecycle costs and negative impacts. However, a noticeable performance gap exists between them, primarily attributable to differences in the management effectiveness of secondary environmental impacts generated by the remediation activities themselves. Site 2′s relatively lower composite score suggests that its remediation construction process likely generated relatively significant one-time environmental loads. Although the project subsequently achieved economic gains, such as land value appreciation, during the reuse phase, the high secondary impacts from the remediation works somewhat undermined its overall sustainability. In contrast, Site 3’s less negative score reflects relatively better management efficacy in controlling the secondary environmental impacts of its remediation engineering. Nevertheless, its ultimate failure to achieve a net positive benefit might be related to the economic drivers and social integration of the redevelopment model—for instance, its lower land value appreciation and mixed social feedback suggest room for improvement in translating the potential of the remediated land into sustained, broad positive externalities. The situation of Site 3 exemplifies a trade-off between environmental risk control and the maximization of comprehensive benefits.

Through the comparative analysis of the comprehensive performance of these three redeveloped sites, this post hoc assessment study derives the following core conclusion: the successful redevelopment of contaminated sites relies not merely on the technical completion of remediation works but more critically on the precise alignment of remediation quality, redevelopment positioning, and regional sustainable development needs. The successful paradigm of Site 1 highlights the possibility and importance of synergizing environmental safety baselines, economic value creation, and social welfare enhancement. In contrast, Site 2′s deeply negative performance is largely due to the high environmental load associated with its remediation works; Site 3 represents an intermediate state where major risks were averted, yet the full potential of the land was not fully unleashed. Therefore, for future contaminated site management, policymakers and project developers should look beyond the singular goal of “remediation completion” and commit to planning and evaluating the comprehensive performance across the entire lifecycle, ensuring that redevelopment projects genuinely contribute to net positive benefits and long-term sustainable development for the region.

These assessment results are derived within the specific indicator system and weight assignments established by this study, providing a systematic comparative perspective based on a defined framework. It is important to note that the outcomes of comprehensive evaluations are highly dependent on the selection of indicators and the assigned weights across dimensions. Should decision-making objectives or value orientations shift—for example, placing greater emphasis on economic stimulus or short-term social employment—the application of a different weighting structure could yield a different ranking. Consequently, the negative composite scores for Sites 2 and 3 should be interpreted as indicating that their net benefits fall short of the ideal state under the current evaluation framework, which prioritizes environmental health and comprehensive sustainability. This does not entirely negate the positive value these remediation and redevelopment projects may possess in specific aspects (e.g., Site 2’s land value appreciation or Site 3’s resident satisfaction). The results primarily reveal the potential trade-offs inherent in this multi-objective decision-making context of sustainable redevelopment, rather than constituting an absolute negation of the projects’ overall value.

4. Conclusions

This study developed and validated a comprehensive, quantitative sustainability assessment framework for contaminated site remediation, addressing the critical limitation of subjectivity in prevailing qualitative methods. By integrating fully quantitative indicators across environmental, economic, and social dimensions—powered by LCA, economic analysis, and innovative social big data (NTL, POI, sentiment analysis)—the framework establishes a robust and reproducible foundation for cross-project comparison. The application of this framework to three distinct case studies in China yielded several key insights. Firstly, the AHP-derived weights, which prioritized environmental health (particularly Disability-Adjusted Life Years) and substantive social outcomes over direct costs, reflect a value orientation aligned with long-term sustainable development. Secondly, the case study comparison conclusively demonstrated that the choice of remediation technology and project scale are primary determinants of lifecycle environmental impacts. The superior performance of Site 1 underscores the success of a balanced strategy that effectively controls primary and secondary environmental impacts while successfully unlocking socio-economic value during reuse. In contrast, the negative net benefits of Sites 2 and 3 highlight the potential trade-offs, where high secondary environmental loads (Site 2) or suboptimal redevelopment value-capture (Site 3) can undermine overall sustainability. The primary contribution of this research is a transparent and objective decision-support tool that enables project managers and policymakers to move beyond the singular goal of “contaminant removal” and towards a holistic optimization of remediation strategies. Ultimately, this study advocates for a paradigm shift in contaminated land management: the goal should not merely be to remediate but to execute remediation in a way that actively transforms these sites into net-positive assets for environmental health, economic prosperity, and social well-being. Future work could focus on expanding the framework’s applicability by incorporating spatial-temporal dynamics and integrating uncertainty analysis to enhance its robustness under data constraints.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/w17233416/s1, Figure S1: Satellite images of the site before and after remediation, comparing the state around 2017 before remediation with the state approximately 5 years after remediation. The green line delineates the 1-km buffer zone surrounding the site; Figure S2: Changes in land prices at the site location. Unit land prices are retrieved from the Department of Natural Resources of Shandong Province; Figure S3: Processing flow of nighttime light data for the study sites; Figure S4: Location of public service facilities within a 1-km radius of Site 1; Figure S5: Location of public service facilities within a 1-km radius of Site 2; Figure S6: Location of public service facilities within a 1-km radius of Site 3; Table S1: Inventory of material and energy consumption for the remediation of Site 1; Table S2: Inventory of material and energy consumption for the remediation of Site 2; Table S3: Inventory of material and energy consumption for the remediation of Site 3; Table S4: Sentiment analysis results of social opinion based on VADER.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L.; methodology, X.Y.; software, X.Y. and Q.H.; validation, Y.L., R.C. and X.Y.; formal analysis, X.Y. and X.L.; resources, R.C.; data curation, X.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L. and X.Y.; writing—review and editing, Y.L.; visualization, X.Y.; supervision, G.Z.; funding acquisition, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Evaluation Methods and Prevention/Control Modes for Zoning, Classification, and Grading of Soil-Groundwater Pollution in Operational Pharmaceutical and Chemical Industry Parks under the National Key Research and Development Program (2023YFC3707703) and Hebei Provincial Water Resources Science and Technology Program Project (HBSL2025-11).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bardos, R.P.; Bone, B.D.; Boyle, R.; Ellis, D.; Evans, F.; Harries, N.D.; Smith, J.W.N. Applying sustainable development principles to contaminated land management using the SuRF-UK framework. Remediation 2011, 21, 77–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cenci, J.; Becue, V.; Koutra, S.; Liao, C. Stewardship of industrial heritage protection in typical Western European and Chinese regions: Values and dilemmas. Land 2022, 11, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, D. Sustainable remediation in China: Elimination, immobilization, or dilution. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 15572–15574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeli, B.B.; Visentin, C.; Thomé, A. Design of a central tool for sustainability evaluation and weighting to decision-making support of contaminated soils remediation. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.C.; Tsai, Y.C.; Ma, H.W. Toward sustainable brownfield redevelopment using Life-Cycle thinking. Sustainability 2016, 8, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, D.; Gu, Q.; Ma, F.; O’Connell, S. Life cycle assessment comparison of thermal desorption and stabilization/solidification of mercury contaminated soil on agricultural land. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 139, 949–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Huo, M.; Yu, L.; Wang, P.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, C.; Wang, D.; Ding, A.; Li, F. Life cycle assessment-based decision-making for thermal remediation of contaminated soil in a regional perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 392, 136260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Tian, H.; Xing, T.; Yan, M.; Wen, C.; Sun, Y.; Tan, Q. Life cycle assessment and cost analysis of typical remediation technologies for cadmium-contaminated soil. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 118765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardos, R.P.; Bone, B.D.; Boyle, R.; Evans, F.; Harries, N.D.; Howard, T.; Smith, J.W. The rationale for simple approaches for sustainability assessment and management in contaminated land practice. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 563, 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, F.B.; Günther, W.M.R.; Philippi, A.; Henderson, J. Site-specific framework of sustainable practices for a Brazilian contaminated site case study. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 801, 149581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.; Zhu, L. Paving the way toward soil safety and health: Current status, challenges, and potential solutions. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2024, 18, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; He, L.; Zhang, B.; Yan, Y.; Jiao, W.; Ding, N. A comprehensive evaluation method for soil remediation technology selection: Case study of ex situ thermal desorption. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Wei, C.; Song, X.; Liu, X.; Tang, Z.; Liu, P.; Wei, Y. Thermal conductive heating coupled with in situ chemical oxidation for soil and groundwater remediation: A quantitative assessment for sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 423, 138732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, D.; Ding, Z.; Li, G.; Wu, L.; Hu, P.; Guo, G.; Wang, X.; Ma, Y.; O’COnnor, D.; Wang, X. A sustainability assessment framework for agricultural land remediation in China: Sustainability need for the remediation of agricultural land in China. Land Degrad. Dev. 2017, 29, 1005–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Li, S.; Gao, F.; Wang, F.; Lin, J.; Tan, Z. Evaluating the performance of LBSM data to estimate the gross domestic product of China at multiple scales: A comparison with NPP-VIIRS nighttime light data. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 328, 129558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Chen, Z. Global 500 m Resolution “NPP-VIIRS-like” Nighttime Light Dataset (2000–2024); National Earth System Science Data Center: Beijing, China, 2025; Available online: https://www.geodata.cn/data/datadetails.html?dataguid=8213124601985&docId=90 (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Rajabi, F.; Hosseinali, F.; Rabiei-Dastjerdi, H. An examination and analysis of the clustering of healthcare centers and their spatial accessibility in Tehran metropolis: Insights from Google POI data. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 117, 105845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutto, C.; Gilbert, E. VADER: A parsimonious rule-based model for sentiment analysis of social media text. ICWSM 2014, 8, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovera, F.; Cardinale, Y. An analytics approach to extracting location and sentiment insights from classified social media data. Decis. Anal. J. 2025, 16, 100624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Huo, Z.; Ma, F.; Gao, X.; Wu, Y. Application and selection of remediation technology for OCPs-contaminated sites by decision-making methods. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, G.H.; Lee, K.; Kim, G. Estimation of nighttime PM2.5 concentrations over Seoul using Suomi NPP/VIIRS Day/Night Band. Atmos. Environ. 2024, 338, 120861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, H. Forecasting electricity consumption in China’s Pearl River Delta urban agglomeration under the optimal economic growth path with low-carbon goals: Based on data of NPP-VIIRS-like nighttime light. Energy 2024, 294, 130970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X. China Nighttime Light Annual Dataset; Resource and Environmental Science Data Registration and Publication System: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandy, L.M.; Ivanitskaya, L.V.; Bacon, L.L.; Bizri-Baryak, R. Public health discussions on social media: Evaluating automated sentiment analysis methods. JMIR Form. Res. 2025, 9, e57395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, A.; Boldt, M. Using VADER sentiment and SVM for predicting customer response sentiment. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 162, 113746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isnan, M.; Elwirehardja, G.N.; Pardamean, B. Sentiment analysis for TikTok review using VADER sentiment and SVM model. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 227, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, R.; Rekha, A.P.; Nitish, N. Forecasting airline passengers satisfaction based on sentiments and ratings: An application of VADER and machine learning techniques. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2024, 120, 102668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehzadeh, R.; Ziaeian, M. Decision making in human resource management: A systematic review of the applications of analytic hierarchy process. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1400772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sipahi, S.; Timor, M. The analytic hierarchy process and analytic network process: An overview of applications. Manag. Decis. 2010, 48, 775–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D.; Xi, B.; Ren, J.; Wang, Y.; Jia, X.; He, C.; Li, Z. Sustainability assessment of groundwater remediation technologies based on multi-criteria decision making method. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 119, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, H.; Papyan, H.; Minasyan, A.; Wood, D.A.; Ghorbani, P.; Ghorbani, S.; Avagyan, E.; Badakian, S.; Minasian, N. A robust multi-criteria decision-making approach for selecting optimal drugs in epilepsy treatment using the analytic hierarchy process. Brain Disord. 2025, 20, 100292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Mao, P.; Wang, M.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Xia, K.; Chen, J.; Mo, H.; Wang, F.; Li, Z.; et al. Benefit evaluation of in-situ Cd immobilization with naturally occurring minerals using an analytical hierarchy process. Chemosphere 2024, 347, 140720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tameh, S.N.; Gnecco, I.; Palla, A. Analytic hierarchy process in selecting bioretention cells in urban residential settlement: Analysing hydrologic and hydraulic metrics for sustainable stormwater management. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 371, 123142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Hou, D.; Zhang, J.; O’Connor, D.; Li, G.; Gu, Q.; Li, S.; Liu, P. Environmental and socio-economic sustainability appraisal of contaminated land remediation strategies: A case study at a mega-site in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 610–611, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.Y.; Hung, W.T.; Vu, C.T.; Chen, W.T.; Lai, J.W.; Lin, C. Green and sustainable remediation (GSR) evaluation: Framework, standards, and tool. A case study in Taiwan. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 21712–21725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.A.A.; Qadir, Z.; Asad, M.; Kouzani, A.Z.; Mahmud, M.A.P. Environmental footprint assessment of a cleanup at hypothetical contaminated site. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).