Abstract

The purpose of this study is to determine the current state of angler knowledge, opinions, awareness, and use of catch-and-release (C&R) best practices and to identify the main socio-economic factors that determine attitudes and willingness to use C&R among Polish anglers. Knowledge of this issue contributes to more effective management of fisheries and fish stocks. The research was conducted through an online survey form using a technique called CAWI (Computer-Assisted Web Interview). The questionnaire used consisted of 25 questions, including basic socio-economic questions, questions about seniority, frequency, location and method of fishing, and specific factual questions related to knowledge and practices regarding C&R. A total of 1574 respondents participated in the survey. The majority of respondents were male (97.5%). The survey showed that Polish anglers are overwhelmingly willing to practice C&R: 48.8% of respondents always and 44.0% often voluntarily release the fish they catch. Statistical analysis revealed a significant relationship between the use of this practice and the age of the angler (r = 0.46; p = 0.0001). Anglers under the age of 55 were the most likely to use C&R (p = 0.0097). The majority of respondents believe that C&R is important for improving fish stocks, but their knowledge and practices in this area have serious shortcomings. Inadequate knowledge of issues such as barotrauma or safe hook types, as well as inappropriate practices such as photographing and unhooking fish, can negatively affect their survival and ultimately the status of living water resources and ecosystem quality. These shortcomings may be due to inadequate education of anglers and fishery managers.

1. Introduction

Recreational fishing is currently one of the most important forms of fishing, especially in inland fisheries in developed countries [1,2] and in developing countries, especially in the context of ecotourism development [3]. Anglers are one of the main social groups using water resources and are concerned with both good ecological status [4] and the proper condition of ichthyofaunal resources [5]. Recreational fisheries can have a significant impact on the health of both fish stocks [6] and entire aquatic ecosystems [7]. Recreational fisheries also raise significant animal welfare concerns, particularly in the case of catch-and-release fisheries [8,9].

Catch-and-release fishing existed and was promoted as early as the 19th century. The famous chemist and keen angler Sir Humphry Davy, who lived at the turn of the 18th century, wrote that “Every good angler, as soon as his fish is landed, either destroys it at once, if it is to be used for food, or returns it to the water” [10]. Currently, C&R is one of the strategies associated with the management of ichthyofaunal resources and angling fisheries [11,12]. The goal of this strategy is to minimize the negative effects of recreational fishing and its impact on living aquatic resources by reducing fishing mortality, while allowing relatively high levels of angling pressure to be maintained on fish stocks and fisheries [13]. Consistent with Smith’s theory [14] of a shift in the purpose of fishing towards recreation and conservation [2], C&R has already become an integral part of modern fisheries, particularly in inland waters. Farthing et al. [15] noted that the relationship between angling success and the goals of population conservation and environmental integrity can be conflicting, with C&R best practice guidelines drawing a fine line between what is possible, practical, and necessary.

However, for a C&R strategy to be as successful in practice as in theory, an important assumption must be met, namely that the post-release survival of fish should be high [8]. The survival of released fish is largely dependent on decisions made by anglers themselves, both before and during fishing [12,16]. This is particularly true for the choice of equipment, fishing method, and handling of the fish [13]. Assuming that angler knowledge and experience may be important for fish survival after release [17,18,19,20], it is important to know the state of angler knowledge and C&R practices [16,21]. There is still a lack of comprehensive angler knowledge on this topic [11,22], and socioeconomic studies of anglers are becoming increasingly important for the proper management of fish stocks and fisheries [23,24].

In different parts of the world and in different countries, motivations, knowledge, and practices of angling can vary, which may be due to different cultural, social, and economic conditions [2,25,26]. Recreational fisheries in Eastern Europe are deeply rooted in tradition and culture [27,28]. However, the practice of voluntary release of caught fish has not been very popular in the past, although recreational and sportive motivations of Polish anglers have always been important [13,29,30]. Today, angling in Poland is similar to that in other developed countries, and the acceptance of C&R by Polish anglers has become a reality [5,31]. One of the reasons for this situation is undoubtedly the improvement in the economic situation of the Polish population that has taken place during the economic transformation of the past years, which is consistent with Smith’s theory mentioned earlier [1,2,14].

The motivations that drive recreational anglers are already largely understood [2,16,32,33], including in Poland [5,31]. In contrast, we have relatively little information on the state of anglers’ knowledge in the context of C&R use, and this gap is not well filled [12]. The purpose of the present study is to determine the current state of anglers’ knowledge, attitudes, opinions, and levels of knowledge and use of best practices in recreational C&R fishing and what socioeconomic factors explain and determine the attitudes of Polish anglers toward C&R practices. Obtaining such information, together with understanding the socio-economic profile of anglers, will allow for more effective fisheries management and more effective planning of educational activities aimed at anglers and fisheries managers. Such actions should ultimately lead to improvements in fish stocks and aquatic ecosystems. Considering previous surveys conducted in Poland [5,30,31,34], the current survey included the largest number of anglers and the highest number of responses obtained. If the motivations and methods of fishing are found to be similar to those in other countries, the results and conclusions presented in this study can be applied, at least in part, to other angling populations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Tools

A web-based form—CAWI (Computer-Assisted Web Interview)—was used to conduct the research. For this purpose, the Google Forms application was used, which has a simple interface, the ability to adapt the survey for visually impaired people, mobility by adapting to computers and smartphone devices, and allows easy distribution of the survey through a link. The tool is also widely known, which helps to reduce the percentage of uncompleted surveys [31,34,35]. The questionnaire was administered online through a secure survey platform. Participants accessed the questionnaire through a web link and were able to complete it at their convenience. The survey was active for one month to ensure a high response rate.

The survey was distributed through Polish language websites and social networks, including angling associations and clubs, Facebook groups and fan pages, angling discussion groups, and online forums. Information about the survey was also published by the main Polish institutions and universities related to angling and the use of fish resources, such as the University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn, the Institute of Inland Fisheries—State Research Institute, and the Polish Angling Association. Participation in the study was anonymous and voluntary, no incentives were offered, and the only requirement was to be an angler. The survey followed ethical guidelines to ensure the privacy and confidentiality of respondents. All data collected were anonymized and analyzed in aggregate form. Informed consent was obtained at the beginning of the study, explaining the purpose of the study and the voluntary nature of participation. Additional ‘snowball sampling’ techniques [36] were used, where respondents were encouraged to circulate and share the survey link with their fishing friends, with the proviso that if someone saw it in more than one source, it would only be completed once. The full questionnaire was distributed between 3 March and 3 April 2023. The questionnaire took approximately 10 min to complete. A total of 1574 participants provided complete responses.

2.2. Structure of the Questionnaire

The survey consisted of 25 questions, including 5 basic socioeconomic questions on gender, age, education, residence, and income (Table 1); 4 questions on duration, frequency, location, and method of fishing (Table 2); and 16 specific C&R-related factual questions on the following: Opinions on whether the use of C&R improves fish stocks and the practical application of C&R; Photographing fish; Use of C&R for specific species; Incidence of deep hooking and how to deal with difficulties in removing hooks; Knowledge of bleeding and other damage to fish tissues and mortality of fish immediately after release; Knowledge of the concept of fish welfare and the phenomenon of barotrauma; Anglers’ opinions on the use of appropriate fishing gear; Knowledge and practical use of barbless hooks and circle hooks; Methods of finishing hooks and how to land fish; Use of special tools for unhooking fish; Assessment of the chances of fish survival. Those preferences and opinions are available in Table S1 (Supplementary Material).

Table 1.

Basic demographic and socio-economic information on Polish anglers.

Table 2.

Information on experience, frequency, location, and fishing method of anglers surveyed.

Pike, Esox lucius, pikeperch, Sander lucioperca, european catfish, Silurus glanis, asp, Aspius aspius and Eurasian perch, Perca fluviatilis were classified as predatory for the purpose of the analysis. Species identified as salmonids included all species in the family Salmonidae. Carp and grass carp included all fishes in the species Cyprinus carpio and Ctenopharyngodon idella. Large native cyprinids included tench Tinca tinca, bream Abramis brama, chub Squalius cephalus, barbel Barbus barbus, ide Leuciscus idus, common nase Chondrostoma nasus, and vimba bream Vimba vimba. Small native cyprinids include the following species: bleak Alburnus alburnus, roach Rutilus rutilus, white bream Blicca bjoerkna, gudgeon Gobio gobio, dace Leuciscus leuciscus.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as percentages (%) calculated from the total number of responses to a given question. Statistical analysis of the questionnaires (n = 1574) was performed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation; Redmond, WA, USA) and Statistica 13.3 (TIBCO Software Inc.; Palo Alto, CA, USA). Comparative analysis using Peterson’s nonparametric chi-squared (χ2) test of independence was used to show differences in respondent responses by age, education, location, and income (wealth). Bivariate tables were used to analyze two characteristics of the variables, and multivariate contingency tables were used to examine the correlation of three or more variables together. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used to determine the strength of the relationship (correlation) between two variables. The following criteria were used to determine the strength of reported correlations: <0.2—weak correlation; 0.2–0.4—low correlation; 0.4–0.6—moderate correlation; 0.6–0.8—high correlation; 0.8–0.9—very high correlation; 0.9–1.0—almost complete correlation [37]. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed using Statistica 13.3 software. In this study, a significance level of α = 0.05 was assumed (statistically significant differences were considered at p < 0.05).

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Economic Characteristics of Anglers

The majority of anglers surveyed were middle-aged males. The youngest anglers (under 18 years old) represented only 2.7% of the total, and the oldest anglers (over 75 years old) represented 1.5% (Table 1). The majority of respondents reported a high school education and a university degree (Table 1). The location of anglers varied, with the highest percentage of respondents living in small towns of up to 50,000 inhabitants (Table 1). The income of anglers, calculated as annual net income per family member, also varied, although most people (41.3%) reported a medium income, between 2001 and 4000 PLN (470–940 EUR) (Table 1). Most anglers were characterized by a long fishing experience, which was significantly correlated with the age of the respondents (r = 0.76 and p < 0.01). Anglers most often reported fishing 10–50 days or 51–100 days per year (Table 2). The majority of respondents fished in lakes and rivers, while only 8.4% of anglers fished in the sea (Table 2). The preferred fishing methods of Polish anglers are mainly spinning/casting and feeder and other ground methods (fishing from the bottom using a groundbait feeder, when the role of the float is taken over by a quiver tip [13]) (Table 2).

3.2. Use of C&R and Anglers’ Views on Its Effectiveness

The study showed that Polish anglers were overwhelmingly in favor of C&R, with 48.8% of respondents always and 44.0% of respondents often releasing the fish they caught under C&R (Table 3). Statistical analysis showed that the response to this question was related to the age of the angler (r = 0.46; p < 0.01). The most frequent use of C&R was among anglers under 55 years of age (p = 0.0097) (Table 4). It was also observed that the practical use of C&R was also related to income level (r = 0.34; p < 0.01), and in general those with the highest income were the most likely to release the fish they caught (Table 4; p = 0.0407). The majority of anglers did not demonstrate high selectivity and used C&R for various fish species, 24.8% of respondents declared releasing predators, while 22.4% of anglers declared releasing carp and grass carp.

Table 3.

Frequency of C&R practices and incidents reported by anglers.

Table 4.

Knowledge and application of C&R practices depending on selected socio-economic parameters of anglers.

The overwhelming majority of anglers surveyed (80.1%) stated that they believe C&R has improved fish stocks. There was a similar relationship with the age of the respondents (r = 0.46; p < 0.01). It appears that younger anglers are more convinced of the positive impact of C&R use on fish stocks than older anglers (Table 4). The belief in the positive role of C&R in conserving fish stocks is also related to income level; in general, those with higher incomes are more likely to release the fish they catch (Table 4).

The vast majority of respondents (82.2%) agreed that the use of appropriate gear increases the chances of fish survival and the success of the C&R strategy, again with a correlation, albeit weaker, with anglers’ age (r = 0.27; p < 0.01) and income level (r = 0.27; p < 0.01). Anglers under the age of 55 (p = 0.01) and those with a higher income (p = 0.03) were more likely to believe that the chances of fish survival depended on the use of appropriate fishing gear (Table 4).

3.3. Anglers Knowledge and C&R Practices

When asked about their familiarity with the concept of “fish welfare”, the majority of anglers indicated that they were familiar with the concept, and the same was true for familiarity with the concept of barotrauma, although in this case, 29.0% of respondents indicated that they were not familiar with the phenomenon (Table 5). The level of familiarity with both concepts depended on the level of education, although the correlation for familiarity with the concept of fish welfare was lower (r = 0.26; p < 0.01) than for familiarity with the phenomenon of barotrauma (r = 0.44; p < 0.01). Those with higher education were the most knowledgeable, especially for the phenomenon of barotrauma (Table 4). The same was true for those with the highest income (Table 4).

Table 5.

Anglers’ reported level of familiarity with the concept of fish welfare and the phenomenon of barotrauma.

Anglers often photograph fish before releasing them; more than half of the respondents reported doing so (Table 3). The frequency of this practice is moderately correlated with the age of the angler (r = 0.41; p < 0.01). Anglers rarely encounter a situation where a fish swallows the baited hook deep and there is difficulty in retrieving it (Table 3). The majority of anglers do not cut the line when a fish swallows the hook deeply and is difficult to retrieve; less than 15% always cut the line (Table 3), but there is a correlation with age (r = 0.40; p < 0.01), and in this case, older anglers are more likely to cut the line (Table 4). The vast majority of respondents rarely observed bleeding and/or other fish tissue damage as a result of hooking, and fish mortality immediately after release is rarely observed by anglers (Table 3).

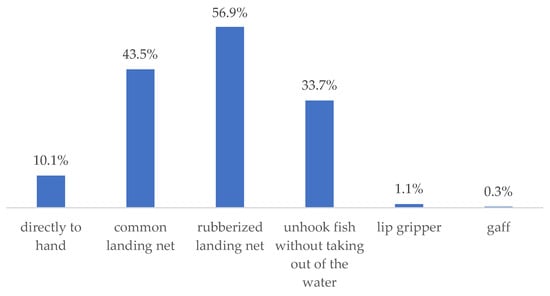

Among Polish anglers, barbless hooks are much more popular than circle hooks. More than 37.4% of anglers stated that they did not know and had never used circle hooks (Table 6). Anglers use different methods to finish the catching of the fish, but most often they use a landing net; the majority of them use a safe rubberized landing net for this purpose, while the gaff and the lip gripper are marginally used. Additionally, 33.7% of the respondents try not to take the fish out of the water at all and unhook it in the water (Figure 1). Regarding the use of hooking tools, the majority of respondents use pliers (88.4%), only 1.7% of respondents do not use any tools to unhook fish. Anglers surveyed assess the chances of a fish surviving before releasing it, but this assessment is overwhelmingly based on their own experience alone, with 68.6% of respondents stating this. In contrast, 27.2% of respondents do not make such an assessment at all, and very few anglers use an assessment based on the fish’s reflexes—Reflex Action Mortality Predictors (RAMP).

Table 6.

Knowledge and use of alternative hook types by anglers.

Figure 1.

Most common types of fish landings reported by anglers.

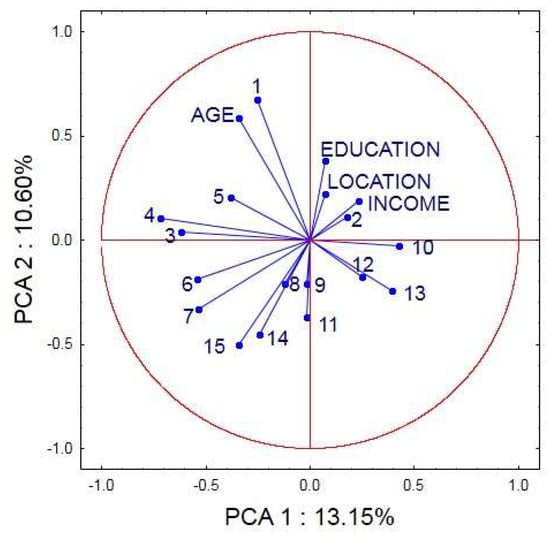

A PCA resulted in the first and second PCA axes explaining 13.1% and 10.6% of variation, respectively (Figure 2). The variables education, location, and income loaded positively on the first PCA axis, indicating their co-occurrence was important in responses. The variable age loaded positively on the second PCA axis and was independent from other variables (Figure 2, Table 7). The two principal components did not fully explain the variation in the data, but they did reveal some patterns in the relationships between the variables. The variables education, location, and income are strongly related to the first principal component (PCA 1), indicating that their co-occurrence is an important aspect in the structure of the data (Figure 2, Table 7). The variable age is more related to PCA 2 and less related to the other variables, indicating a separate behavior or independent influence on the results analyzed (Figure 2, Table 7). Questions on the impact of the use of C&R have a strong correlation with the first factor (PCA 1), which may indicate that this variable is one of the main differentiators among respondents (Figure 2, Table 7). The variable on the use of circle hooks and the assessment of the chances of fish survival has a moderate correlation with the second factor (PCA 2).

Figure 2.

Principal component analysis (PCA) showing correlations of variables to factors in the context of C&R, detailed description of variables and factors in Table 7.

Table 7.

Description of variables and factor loadings in the PCA in Figure 2.

4. Discussion

Most anglers surveyed were men, with women accounting for only 2.5% of the total. It appears that fishing, including recreational fishing, is predominantly a male activity [38,39,40,41,42,43]. Although in some countries the percentage of female anglers may be higher, for example, in Spain, it is about 7% [44], and in Canada, women account for between 15% and 21% of all anglers [39]. In contrast, in artisanal shellfish fisheries in Samoa, the proportion of men and women may even be equal [45]. According to some researchers, the proportion of female anglers may increase in the future [46], although recent data from Poland indicate a smaller number of female anglers than in previous studies, where the proportion of women was estimated to be 4.9% [5].

Recreational fishing can be practiced at virtually any age because it does not appear to require as much physical fitness as other sports and outdoor activities. In the present study, the majority of anglers were middle-aged. The situation was similar in Germany [47] and Canada, where there was a clear dominance of middle-aged people among anglers; however, the researchers also noted that the average age had increased to over 35 years [39]. Similar conclusions were reached by Aprahamian et al. [48], Van der Hammen and Chen [43], and Czarkowski et al. [5], who found that the average age of anglers has increased in recent years. Most Polish anglers declared a secondary or higher education. The opposite is true, for example, in the Netherlands, where the majority of anglers are those with the lowest level of education [43]. In terms of place of residence, the majority of respondents lived in rural areas and small towns, which is similar to the study by Czarkowski et al. [5]. Polish anglers were also characterized by long angling experience, which, not surprisingly, correlated strongly with angler age.

Respondents’ fishing intensity varied between 10 and 100 days per year, and most fished mainly in natural inland waters: lakes and rivers, i.e., similar to Karpiński and Skrzypczak [34] and Czarkowski et al. [5]. On the other hand, fishing in artificial ponds is becoming more popular among Polish anglers, with almost 37% of respondents already fishing there. The least popular angling activity is sea fishing, and in this respect, Poland compares quite poorly with typical marine countries such as the Netherlands, where about 40% of anglers fish in the sea [43]. In contrast, only 8.4% of anglers in Poland report fishing in marine waters.

Comprehensive reviews of C&R and its effectiveness as a method for protecting fish stocks and maintaining the attractiveness of angling fisheries have already been written, e.g., Muoneke and Childress [49], Bartholomew and Bohnsack [50], Casselman [51], Cooke and Suski [52], Arlinghaus et al. [53], Pelletier et al. [54], FAO [55], Brownscombe et al. [12], from which anglers can draw expert knowledge. The internet, especially scientist-driven websites [56] such as www.keepfishwet.org (accessed on 3 March 2025), can also help to disseminate knowledge on the topic. In contrast, angling organizations do not necessarily provide comprehensive knowledge on C&R [57]. It also seems that a lot of angling myths have grown up around this issue, leading some people to completely underestimate C&R as an effective conservation method, and others to overestimate the role of C&R, treating it as the only appropriate strategy, and perhaps even as an angling ideology [20]. This is not surprising given that some C&R issues are also poorly understood by the scientific community, and there is an urgent need for additional research [11]. However, in the present study, the vast majority—more than 80%—of anglers surveyed said that the use of C&R improves fish stocks. This is probably the reason why the vast majority of Polish anglers are willing to use C&R, which was not so obvious before [30]. It also seems that the practice of C&R has become even more popular in Poland in recent years. Compared to the study by Czarkowski et al. [5], where more than 55% of Polish anglers stated that they often release the fish they catch and more than 15% that they always do so, in the current survey, the values were 44% (often) and 49% (always). The most important factors influencing attitudes and willingness to use C&R among Polish anglers were age and income, with younger individuals and those with higher income levels demonstrating significantly greater openness toward sustainable angling practices, likely due to increased environmental awareness, broader access to ecological education, and the influence of social media promoting ethical fishing behaviors. According to Karpiński and Skrzypczak [34], this was further influenced by anglers’ association membership and degree of specialization, which tend to reinforce pro-conservation attitudes. Altogether, these findings suggest a gradual but meaningful cultural shift in Polish recreational angling toward more conservation-oriented practices.

Most anglers do not show any particular selectivity in releasing fish of the various species and in most cases apply C&R to all fish species. A similar lack of selectivity was previously observed in Poland by Czarkowski et al. [5]. This differs from the observed selectivity associated with angler specialization in other European countries, such as Germany [24,58,59] or North America [60,61]. The lack of selectivity in releasing fish observed among Polish anglers may be due to the relatively low attractiveness of most waters in Poland and the low selectivity of anglers in catching the dominant fish in these waters. In a large part of the fishing grounds, Polish anglers do not catch attractive fish that they would like to catch (e.g., large predators) because their numbers are significantly reduced in the ecosystems [5]. However, in the present study, some anglers reported relatively high levels of release of predators and carp and amur relative to other fish. Similar observations were made by Karpiński and Skrzypczak [34]. Anglers should be aware that the ill-considered use of C&R for some species, especially non-native species, can be dangerous to aquatic ecosystems and threaten rare native fish species [62,63] and lampreys [64].

Awareness of fish welfare and anglers’ knowledge of how certain C&R practices affect fish physiology and survival can be critical to the success of a C&R strategy. The vast majority of anglers surveyed said that using the appropriate fishing gear increases fish survival and the success of C&R strategies. It should be emphasized that it is mainly the autonomous decisions of anglers and their choice of appropriate equipment that determine the condition of fish after release [12,65]. In general, it should be noted that Polish anglers asked about their knowledge of the concept of so-called fish welfare were familiar with it, while in the case of barotrauma many anglers showed a complete lack of knowledge of the phenomenon. Barotrauma is a negative reaction of a fish’s body resulting from a rapid drag from deeper water to the surface [66,67]. It particularly affects closed-bodied fish fished at great depths [67,68], although it can occur in small freshwater species such as smallmouth bass Micropterus dolomieu or Eurasian perch P. fluviatilis when fished at depths of 5–7 m [69,70]. The level of knowledge regarding familiarity with these concepts depended on the educational level of the respondents. Anglers with higher levels of education were significantly more knowledgeable about these issues. This shows that the level of education of the public may also be important in the context of recreational fishing. Anglers’ awareness of the possible negative impacts of C&R should be as high as possible [12], so it seems reasonable to introduce educational programs for anglers.

Anglers like to brag about their fishing success, and the desire to release a trophy as part of C&R compels them to document it with images in the form of photographs or videos [12,56]. Our survey found that Polish anglers often photograph fish before releasing them, with more than half of respondents doing so frequently. Unfortunately, photography exposes fish to additional risks, on the one hand by significantly increasing handling time and exposure to air, and the timing of this exposure is critical for fish survival [47,71,72,73]. On the other hand, it increases the risk of mechanical injury if fish are mishandled (e.g., dropped), especially for large specimens that are prone to damage [74]. For this reason, anglers should minimize photography and not engage in prolonged photo shoots with the fish they catch.

Respondents rarely encountered a situation where a fish deeply swallowed a baited hook and had difficulty retrieving it. In general, deep hook swallows with bait are more common when fishing with organic, natural, and live baits than with artificial baits [51,75], and among artificial baits, deep hook swallows are more common with so-called soft baits than with hard baits and artificial flies [76,77], as well as with mixed ice lures [70]. Most anglers do not cut the line when a fish swallows the hook deeply and is difficult to remove, but rather try to get out and retrieve the hook with the bait. If a fish swallows the bait deeply and the angler wants or needs to release the bait, it is better to cut the line than to try to forcibly remove the hook, because fish survival rates are higher when the line is cut and the fish are able to get rid of the hook themselves [78,79,80,81,82]. It is difficult to identify the reasons why anglers do not follow the recommended procedures. It may be due to fear of damaging their equipment and losing the hook with the bait, or it may be due to a lack of knowledge. The vast majority of respondents also rarely encountered bleeding and/or other damage to fish as a result of hooking and hauling. This is a good sign, as damage resulting from hook penetration into fish body tissues, especially bleeding, is an important determinant of higher fish mortality [47,49,83,84].

When it comes to the use of alternative types of hooks to the classic barbless J-hook, barbless hooks are definitely more popular in Poland than round hooks. Many Polish anglers claim to use barbless hooks frequently, while almost 40% of respondents are completely unfamiliar with round hooks. This is consistent with previous observations and the lack of availability of this type of hook on the Polish market [13,85]. It is unfortunate that circle hooks are so unpopular in Poland, as research shows that they are safe hooks that hook fish at shallow depths [85,86,87,88,89,90,91]. Perhaps in the future, some form of popularization of circle hooks among anglers should be considered.

When anglers finally landing a fish, they most often use a safe, rubberized landing net, which is also to be welcomed as it is mostly safe for fish [92,93]. However, it would be good if anglers were more likely to unhook the fish while it is still in the water, rather than pulling it out of the water with a landing net [12,56]. Surveyed anglers assess the chances of survival of a fish before releasing it, but this assessment is mostly based only on their own experience; Polish anglers do not use the Reflex Action Mortality Predictors (RAMP) assessment. This method was developed for commercial fisheries [94] and later anglers started to use it [12]. This procedure can be greatly simplified and modified for angling needs [85]. In the future, proper angler education should also be provided in this regard.

5. Conclusions

The present study was non-probabilistic in nature, so the results should be interpreted with some caution. The authors of this paper are aware of certain limitations resulting from the electronic distribution of the survey, related to the possible over-representation of anglers who are very active on the Internet and the under-representation of people who do not use the Internet or are not very active online. In the case of studies involving groups that share a common hobby, it is difficult to achieve a fully representative sample. This is one of the reasons why the same research methodology is used by other authors in studies of anglers, including issues related to C&R [31,34,35]. Due to the fact that the results presented in this study are based on the opinions of anglers who use the Internet, great caution should be exercised when automatically extrapolating them to all Polish anglers. Nevertheless, the data obtained allow some assessment of the knowledge and attitudes of Polish anglers towards the concept of voluntary release of caught fish. In general, it can be said that Poland has become a country where the C&R concept is already well known and widely used, although the tradition of using this solution in Poland is short. It should also be noted that younger generations of anglers are more interested in using C&R and gaining knowledge in this area, as well as better-off anglers with higher incomes. On the other hand, better educated anglers have a better knowledge of some of the concepts and phenomena related to the release of caught fish. A positive sign from the study is that anglers rarely encounter deep critical anatomical hooking locations (AHL) and the occurrence of bleeding and tissue damage, as well as post-release fish mortality.

As the PCA analysis shows, technical aspects of fishing may be related to the age or education of anglers. Knowledge and practices related to C&R were found to be more correlated with socio-economic characteristics such as education, place of residence and income. The present results indicate that demographic factors (age, education, residence) and perceptions of C&R are the main determinants of differences in respondents’ responses. Despite the fact that the vast majority of respondents are convinced of the positive impact of C&R on the state of fish stocks, their knowledge and application of good C&R practices already show some gaps and deficiencies. As this study shows, there is a lack of knowledge about harmful phenomena occurring during fishing (e.g., barotrauma) or alternative safe hook types.

Furthermore, the practices used by a significant number of anglers to photograph fish, remove them from the water, unhook them, or assess their chances of survival leave much to be desired. The shortcomings and gaps we have shown are most likely due to the lack of proper education of anglers and fishery managers. The Polish Angling Association, the largest angling organization in Poland with more than 600,000 members [5], does not provide comprehensive education on C&R and the application of best practices related to it. State and local government institutions also do not provide any form of education in this area. Therefore, we recommend both social factors and public institutions to provide comprehensive education to anglers based on available scientific knowledge, taking into account issues related to fish physiology and ecology. However, the transfer of this knowledge to angling communities should not be purely academic but should be as simple and accessible as possible. Education and training must also take into account the different levels of education of anglers. We are aware that the transfer of knowledge and the education of anglers may face logistical, socio-economic and cultural problems. However, in our opinion, it is necessary to at least consider a solution to this problem that will comprehensively ensure an increase in the level of knowledge among Polish anglers.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/w17101448/s1, Table S1: The full survey questionnaire.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.K.C., A.K. and K.K.; investigation, T.K.C., A.K., K.K. and A.H.-B.; methodology, T.K.C., A.K., K.K., J.N. and A.D.; resources, T.K.C., A.K. and K.K.; data curation, T.K.C., K.K., A.H.-B. and J.N.; writing—original draft preparation, T.K.C., A.K., K.K. and J.N.; writing—review and editing T.K.C., A.K., K.K., A.H.-B., J.N. and A.D.; visualization, T.K.C., A.H.-B. and J.N.; supervision, T.K.C. and K.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Inland Fisheries Research Institute (research topic no. Z-003).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study has been ethically reviewed and accepted by the Ethical Review Board of the University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn. The number for this ethical statement is 2/2022. All research procedures used by the authors of this study comply with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments, as well as with the ethical standards of the Polish Committee for Ethics in Science.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cowx, I.G.; Arlinghaus, R.; Cooke, S.J. Harmonizing recreational fisheries and conservation objectives for aquatic biodiversity in inland waters. J. Fish Biol. 2010, 76, 2194–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arlinghaus, R.; Aas, Ø.; Alós, J.; Arismendi, I.; Bower, S.; Carle, S.; Czarkowski, T.K.; Freire, K.M.F.; Hu, J.; Hunt, L.M.; et al. Global participation in and public attitudes towards recreational fishing: International perspectives and developments. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2021, 1, 58–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.M.; Schneider, P.; Asif, M.R.I.; Rahman, M.S.; Arifuzzaman; Mozumder, M.M.H. Fishery-based ecotourism in developing countries can enhance the social-ecological resilience of coastal fishers—A case study of Bangladesh. Water 2021, 13, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampson, D.I.; Ferrini, S.; Rigby, D.; Bateman, I.J. River Water Quality: Who Cares, How Much and Why? Water 2017, 9, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarkowski, T.K.; Wołos, A.; Kapusta, A. Socio-economic portrait of Polish anglers: Implications for recreational fisheries management in freshwater bodies. Aquat. Living Resour. 2021, 34, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, S.J.; Cowx, I.G. The role of recreational fisheries in global fish crises. BioScience 2004, 54, 857–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlinghaus, R.; Cooke, S.J. Recreational fisheries: Socioeconomic importance, conservation issues and management challenges. In Recreational Hunting, Conservation and Rural Livelihoods: Science and Practice; Dickson, B., Hutton, J., Adams, M.W., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 39–58. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, S.J.; Sneddon, L.U. Animal welfare perspectives on catch-and-release recreational angling. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2007, 104, 176–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browman, H.I.; Cooke, S.J.; Cowx, I.G.; Derbyshire, S.W.; Kasumyan, A.; Key, B.; Rose, J.D.; Schwab, A.; Skiftesvik, A.B.; Stevens, E.D.; et al. Welfare of aquatic animals: Where things are, where they are going, and what it means for research, aquaculture, recreational angling, and commercial fishing. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2019, 76, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davy, H. Salmonia Or, Days of Fly Fishing in a Series of Conversations: With Some Account of the Habits of Fishes Belonging to the Genus Salmo, 4th ed.; John Murray: London, UK, 1851. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, A.J. Guidelines for evaluating the suitability of catch and release fisheries: Lessons learned from Caribbean flats fisheries. Fish. Res. 2017, 186, 672–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownscombe, J.W.; Danylchuk, A.J.; Chapman, J.M.; Gutowsky, L.F.G.; Cooke, S.J. Best practices for catch-and-release recreational fisheries: Angling tools and tactics. Fish. Res. 2017, 186, 693–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarkowski, T.K.; Kupren, K.; Hakuć-Błażowska, A.; Kapusta, A. Fish hooks and the protection of living aquatic resources in the context of recreational catch-and-release fishing practice and fishing tourism. Water 2023, 15, 1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.L. The life cycle of fisheries. Fisheries 1986, 11, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farthing, M.W.; Mann-Lang, J.; Childs, A.R.; Bova, C.S.; Bower, S.D.; Pinder, A.C.; Ferter, K.; Winkler, A.C.; Butler, E.C.; Brownscombe, J.W.; et al. Assessment of fishing guide knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours in global recreational fisheries. Fish. Res. 2022, 255, 106453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blyth, S.; Rönnbäck, P. To eat or not to eat: Coastal sea trout anglers’ motivations and perceptions of best practices for catch and release. Fish. Res. 2022, 254, 106412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunmall, K.M.; Cooke, S.J.; Schreer, J.F.; McKinley, R.S. The effect of scented lures on the hooking injury and mortality of smallmouth bass caught by novice and experienced anglers. N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. 2001, 21, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferter, K.; Borch, T.; Kolding, J.; Vølstad, J.H. Angler behaviour and implications for management: Catch-and-release among marine angling tourists in Norway. Fish. Manag. Ecol. 2013, 20, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delle Palme, C.A.; Nguyen, V.M.; Gutowsky, L.F.G.; Cooke, S.J. Do fishing education programs effectively transfer ‘catch-and-release’ best practices to youth anglers yielding measurable improvements in fish condition and survival? Knowl. Manag. Aquat. Ecosyst. 2016, 417, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarkowski, T.K.; Kapusta, A. The impact of angling experience on the efficiency of float fishing using different hook types. Fish. Aquat. Life 2019, 27, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holder, P.E.; Jeanson, A.L.; Lennox, R.J.; Brownscombe, J.W.; Arlinghaus, R.; Danylchuk, A.J.; Bower, S.D.; Hyder, K.; Hunt, L.M.; Fenichel, E.P.; et al. Preparing for a changing future in recreational fisheries: 100 research questions for global consideration emerging from a horizon scan. Rev. Fish. Biol. Fish. 2020, 30, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, A.J.; Murchie, K.J. Recreational fisheries as a conservation tool for mangrove habitats. Am. Fish. Soc. Symp. 2015, 83, 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Arterburn, J.E.; Kirby, D.J.; Berry, C.R., Jr. A survey of angler attitudes and biologist opinions regarding trophy catfish and their management. Fisheries 2002, 27, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fromherz, M.; Baer, J.; Roch, S.; Geist, J.; Brinker, A. Characterization of specialist European catfish anglers in southern Germany: Implications for future management. Fish. Res. 2024, 279, 107144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorow, M.; Beardmore, B.; Haider, W.; Arlinghaus, R. Winners and losers of conservation policies for European eel, Anguilla anguilla: An economic welfare analysis for differently specialised anglers. Fish. Manag. Ecol. 2010, 17, 106–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beardmore, B.; Haider, W.; Hunt, L.M.; Arlinghaus, R. The importance of trip context for determining primary angler motivations: Are more specialized anglers more catch-oriented than previously believed? N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. 2011, 31, 861–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cios, S. Fish in the Lives of Poles from the Tenth to the Nineteenth Centuries; Wydawnictwo IRS: Olsztyn, Poland, 2007; pp. 1–251. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Trapszyc, A. The fisher and the angler, one of us or one of them—Eternal opposition or transient stereotype? Reflections of a cultural anthropologist. In Sustainable Exploitation of Fisheries Resources and Their Status in 2014; Mickiewicz, M., Wołos, A., Eds.; Wydawnictwo IRS: Olsztyn, Poland, 2015; pp. 111–123. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Leopold, M.; Bnińska, M.; Hus, M. Angling, recreation, commercial fisheries and problems of water resources allocation. In Allocation of Fishery Resources. Proceedings of the Technical Consultation on Allocation of Fishery Resources n Vichy, France, 20–23 April 1980; Grover, J.H., Ed.; United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 1980; pp. 212–221. [Google Scholar]

- Kupren, K.; Czarkowski, T.K.; Hakuć-Błażowska, A.; Świszcz, B.; Rogulski, M.; Krygel, P. Socio-economic characteristics of anglers in selected counties of the Warmińsko-Mazurskie Voivodeship. Stud. Obsz. Wiej. 2018, 50, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrzypczak, A.R.; Karpiński, E.A. New insight into the motivations of anglers and fish release practices in view of the invasiveness of angling. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 271, 111055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, S.J.; Twardek, W.M.; Lennox, R.J.; Zolderdo, A.J.; Bower, S.D.; Gutowsky, L.F.G.; Danylchuk, A.J.; Arlinghaus, R.; Beard, D. The nexus of fun and nutrition: Recreational fishing is also about food. Fish Fish. 2017, 18, 201–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birdsong, M.; Hunt, L.M.; Arlinghaus, R. Recreational angler satisfaction: What drives it? Fish Fish. 2021, 22, 682–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpiński, E.A.; Skrzypczak, A.R. Environmental Preferences and Fish Handling Practice Among European Freshwater Anglers with Different Fishing Specialization Profiles. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawrylik, K.; Kiryluk, H. Fishing preferences of Poles and their impact on tourism development. Acad. Manag. 2024, 8, 359–382. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T.P. Snowball Sampling: Introduction. In Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanisz, A. An Accessible Course in Statistics; StatSoft Polska: Kraków, Poland, 2007. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Arlinghaus, R. Understanding recreational angling participation in Germany: Preparing for demographic change. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2006, 11, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownscombe, J.W.; Bower, S.D.; Bowden, W.; Nowell, L.; Midwood, J.D.; Johnson, N.; Cooke, S.J. Canadian Recreational Fisheries: 35 Years of Social, Biological, and Economic Dynamics from a National Survey. Fisheries 2014, 39, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, M.F.; Nicholas, L.; Lee, I.; Lee, J.H.; Scott, D. Social stratification in recreational fishing participation: Research and policy implications. Leis. Sci. 2006, 28, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, K.M.F.; Machado, M.L.; Crepaldi, D. Overview of inland recreational fisheries in Brazil. Fisheries 2012, 37, 484–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuehn, D.; Luzadis, V.; Brincka, M. An analysis of the factors influencing fishing participation by resident anglers. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2013, 18, 322–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Hammen, T.; Chen, C. Participation rate and demographic profile in recreational angling in The Netherlands between 2009 and 2017. Fish. Res. 2020, 229, 105592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Bote, J.L.; Roso, R. Recreational fisheries in rural regions of the South-Western Iberian Peninsula: A Case Study. Turk. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2014, 14, 135–144. [Google Scholar]

- Purcell, S.W.; Tagliafico, A.; Cullis, B.R.; Gogel, B.J. Understanding gender and factors affecting fishing in an artisanal shellfish fishery. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkett, E.M.; Winkler, R.L. Recreational fishing participation trends in Upper Great Lakes States: An age-period-cohort analysis. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2018, 24, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlinghaus, R.; Klefoth, T.; Kobler, A.; Cooke, S.J. Size selectivity, injury, handling time, and determinants of initial hooking mortality in recreational angling for northern pike: The influence of type and size of bait. N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. 2008, 28, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprahamian, M.; Hickley, P.; Shields, B.A.; Mawle, G.W. Examining changes in participation in recreational fisheries in England and Wales. Fish Manag. Ecol. 2010, 17, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muoneke, M.I.; Childress, W.M. Hooking mortality: A review for recreational fisheries. Rev. Fish. Sci. 1994, 2, 123–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, A.; Bohnsack, J.A. A review of catch-and-release angling mortality with implications for no-take reserves. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2005, 15, 129–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casselman, S.J. Catch-and-Release Angling: A Review with Guidelines for Proper Fish Handling Practices; Fish and Wildlife Branch, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources: Peterborough, ON, Canada, 2005; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, S.J.; Suski, C.D. Do we need species-specific guidelines for catch-and-release recreational angling to effectively conserve diverse fishery resources? Biodivers. Conserv. 2005, 14, 1195–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlinghaus, R.; Cooke, S.J.; Lyman, J.; Policansky, D.; Schwab, A.; Suski, C.; Sutton, S.G.; Thorstad, E.B. Understanding the complexity of catch-and-release in recreational fishing: An integrative synthesis of global knowledge from historical, ethical, social, and biological perspectives. Rev. Fish. Sci. 2007, 15, 75–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, C.; Hanson, K.C.; Cooke, S.J. Do catch-and-release guidelines from state and provincial fisheries agencies in North America conform to scientifically based best practices? Environ. Manag. 2007, 39, 760–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. FAO Technical Guidelines for Responsible Fisheries; No. 13. Recreational Fisheries; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Danylchuk, A.J.; Clark Danylchuk, S.; Kosiarski, A.; Cooke, S.J.; Huskey, B. Keepemwet Fishing—An emerging social brand for disseminating best practices for catch-and-release in recreational fisheries. Fish. Res. 2018, 205, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björkvik, E.; Blyth, S.; Blicharska, M.; Danley, B.; Rönnbäck, P. Informing obligations: Best practice information for catch-and-release in Swedish local recreational fisheries management. Fish. Manag. Ecol. 2023, 30, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlinghaus, R. Voluntary catch-and-release can generate conflict within the recreational angling community: A qualitative case study of specialised carp, Cyprinus carpio, angling in Germany. Fish. Manag. Ecol. 2007, 14, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlinghaus, R.; Beardmore, B.; Riepe, C.; Meyerhoff, J.; Pagel, T. Species-specific preferences of German recreational anglers for freshwater fishing experiences, with emphasis on the intrinsic utilities of fish stocking and wild fishes. J. Fish. Biol. 2014, 85, 1843–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aday, D.D.; Parkos III, J.J.; Wahl, D.H. Population and community ecology of Centrarchidae. In Centrarchid Fishes; Cooke, S.J., Philipp, D.P., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 134–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, M.P.; Sanderson, B.L.; Friesen, T.A.; Barnas, K.A.; Olden, J.D. Smallmouth Bass in the Pacific Northwest: A Threat to Native Species; a Benefit for Anglers. Rev. Fish. Sci. 2011, 19, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulêtreau, S.; Gaillagot, A.; Carry, L.; Tétard, S.; De Oliveira, E.; Santoul, F. Adult Atlantic salmon have a new freshwater predator. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulêtreau, S.; Fauvel, T.; Laventure, M.; Delacour, R.; Bouyssonnié, W.; Azémar, F.; Santoul, F. “The giants’ feast”: Predation of the large introduced European catfish on spawning migrating allis shads. Aquat. Ecol. 2021, 55, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulêtreau, S.; Carry, L.; Meyer, E.; Filloux, D.; Menchi, O.; Mataix, V.; Santoul, F. High predation of native sea lamprey during spawning migration. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, S.J.; Nguyen, V.M.; Murchie, K.J.; Danylchuk, A.J.; Suski, C.D. Scientific and stakeholder perspectives on the use of circle hooks in recreational fisheries. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2012, 88, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotshall, D.W. Increasing Tagged Rockfish (Genus Sebastodes) Survival by Deflating the Swim Bladder; California Department of Fish and Wildlife: Sacramento, CA, USA, 1964; Volume 50, pp. 253–260. [Google Scholar]

- Ferter, K.; Weltersbach, M.S.; Humborstad, O.-B.; Fjelldal, P.G.; Sambraus, F.; Strehlow, H.V.; Vølstad, J.H. Dive to survive: Effects of capture depth on barotrauma and post-release survival of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) in recreational fisheries. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2015, 72, 2467–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLennan, M.; Campbell, M.; Sumpton, W. Surviving the effects of barotrauma: Assessing treatment options and a ‘natural’ remedy to enhance the release survival of line caught pink snapper (Pagrus auratus). Fish. Manag. Ecol. 2014, 21, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, M.B.; Suski, C.D.; Esseltine, K.R.; Tufts, B.L. Incidence and physiological consequences of decompression in smallmouth bass after live-release angling tournaments. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 2005, 134, 1038–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarkowski, T.K.; Kapusta, A. Catch-and-release ice fishing with a mormyshka for roach (Rutilus rutilus) and European perch (Perca fluviatilis). Croat. J. Fish. 2019, 77, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, S.J.; Schreer, J.F.; Wahl, D.H.; Philipp, D.P. Physiological impacts of catch-and-release angling practices on largemouth bass and smallmouth bass. Am. Fish. Soc. Symp. 2002, 31, 489–512. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, L.A.; Cooke, S.J.; Donaldson, M.R.; Hanson, K.C.; Gingerich, A.; Klefoth, T.; Arlinghaus, R. Physiology, behavior, and survival of angled and air-exposed largemouth bass. N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. 2008, 28, 1059–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedemeyer, G.A.; Wydoski, R.S. Physiological response of some economically important freshwater salmonids to catch-and-release fishing. N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. 2008, 28, 1587–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, A.; Grace, B. Injuries to barramundi Lates calcarifer resulting from lip-gripping devices in the laboratory. N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. 2009, 29, 1418–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margenau, T.L. Effects of angling with a single-hook and live bait on muskellunge survival. Environ. Biol. Fishes 2007, 79, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meka, J.M. The influence of hook type, angler experience, and fish size on injury rates and the duration of capture in an Alaskan catch-and-release rainbow trout fishery. N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. 2004, 24, 1309–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stålhammar, M.; Fränstam, T.; Lindström, J.; Höjesjö, J.; Arlinghaus, R.; Nilsson, P.A. Effects of lure type, fish size and water temperature on hooking location and bleeding in northern pike (Esox lucius) angled in the Baltic Sea. Fish. Res. 2014, 157, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalbers, S.A.; Stutzer, G.M.; Drawbridge, M.A. The effects of catch-and-release angling on the growth and survival of juvenile white seabass captured on offset circle and J-type hooks. N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. 2004, 24, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuboi, J.I.; Morita, K.; Ikeda, H. Fate of deep-hooked white-spotted charr after cutting the line in a catch-and-release fishery. Fish. Res. 2006, 79, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fobert, E.; Meining, P.; Colotelo, A.; O’Connor, C.; Cooke, S.J. Cut the line or remove the hook? An evaluation of sublethal and lethal endpoints for deeply hooked bluegill. Fish. Res. 2009, 99, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weltersbach, M.S.; Strehlow, H.V.; Ferter, K.; Klefoth, T.; De Graaf, M.; Dorow, M. Estimating and mitigating post-release mortality of European eel by combining citizen science with a catch-and-release angling experiment. Fish. Res. 2018, 201, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litt, M.A.; Etherington, B.S.; Gutowsky, L.F.G.; Lapointe, N.W.R.; Cooke, S.J. Does catch-and-release angling pose a threat to American eel? A hooking mortality experiment. Endang. Species Res. 2020, 41, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyle, J.M.; Moltschaniwskyj, N.A.; Morton, A.J.; Brown, I.W.; Mayer, D. Effects of hooking damage and hook type on post-release survival of sand flathead (Platycephalus bassensis). Mar. Freshw. Res. 2007, 58, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huehn, D.; Arlinghaus, R. Determinants of hooking mortality in freshwater recreational fisheries: A quantitative meta-analysis. Am. Fish. Soc. Symp. 2011, 75, 141–170. [Google Scholar]

- Kapusta, A.; Czarkowski, T.K. Influence of hook type on performance, hooking location, injury, and reflex action mortality predictors in float recreational angling for cyprinids: A case study in northeastern Poland. Fish. Res. 2022, 254, 106390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alós, J.; Cerda, M.; Deudero, S.; Grau, A.M. Influence of hook size and type on short-term mortality, hooking location and size selectivity in a Spanish recreational fishery. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2008, 24, 658–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alós, J.; Mateu-Vicens, G.; Palmer, M.; Grau, A.M.; Cabanellas-Reboredo, M.; Box, A. Performance of circle hooks in a mixed-species recreational fishery. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2009, 25, 565–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- High, B.; Meyer, K.A. Hooking mortality and landing success using baited circle hooks compared to conventional hook types for stream-dwelling trout. Northwest Sci. 2014, 88, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennox, R.; Whoriskey, K.; Crossin, G.T.; Cooke, S.J. Influence of angler hook-set behaviour relative to hook type on capture success and incidences of deep hooking and injury in a teleost fish. Fish. Res. 2015, 164, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edappazham, G.; Thomas, S.N. Influence of hook types on hooking rate, hooking location and severity of hooking injury in experimental handline fishing in Kerala. Fish. Technol. 2016, 53, 284–289. Available online: https://epubs.icar.org.in/index.php/FT/article/view/65803 (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Garner, S.B.; Dahl, K.A.; Patterson, W.F. III. Hook performance and selectivity of Eurasian perch, Perca fluviatilis (Linnaeus, 1758) in the Åland Archipelago, Finland. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2016, 32, 1065–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthel, B.; Cooke, S.; Suski, C.; Philipp, D. Effects of landing net mesh type on injury and mortality in a freshwater recreational fishery. Fish. Res. 2003, 63, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colotelo, A.H.; Cooke, S.J. Evaluation of common angling-induced sources of epithelial damage for popular freshwater sport fish using fluorescein. Fish. Res. 2011, 109, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raby, G.D.; Donaldson, M.R.; Hinch, S.G.; Patterson, D.A.; Lotto, A.G.; Robichaud, D.; English, K.K.; Willmore, W.G.; Farrell, A.P.; Davis, M.W. Validation of reflex indicators for measuring vitality and predicting the delayed mortality of wild coho salmon bycatch released from fishing gears. J. Appl. Ecol. 2012, 49, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).