Engaging Stakeholders to Solve Complex Environmental Problems Using the Example of Micropollutants

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Multi-Stakeholder Dialogue as an Instrument

- The large number of relevant substances and substance groups

- The very different environmental effects, which are also only known to a limited extent, for example with regard to their combination effects, and whose assessment is therefore subject to uncertainties

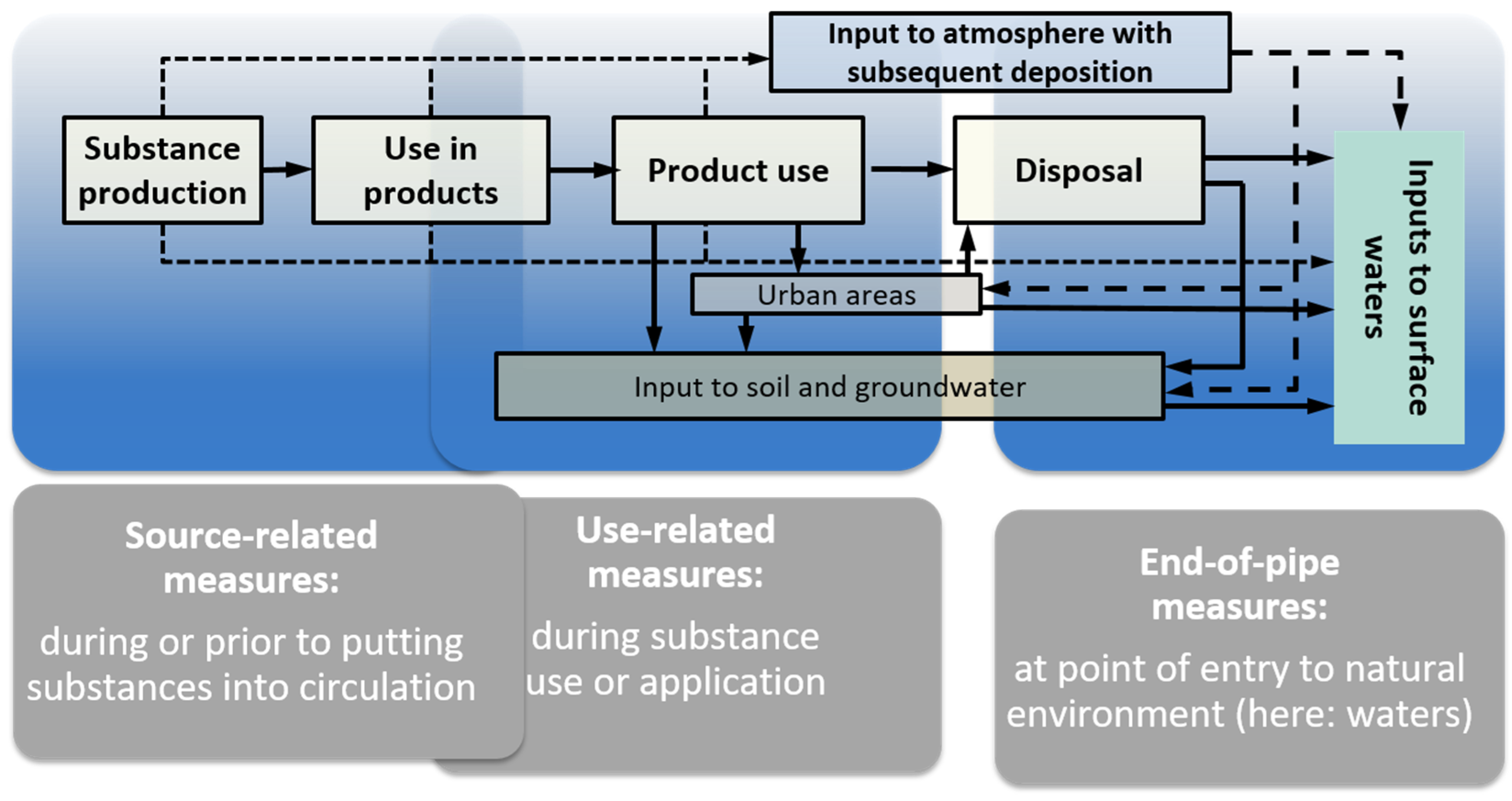

- The different areas of production, industrial use, application and entry paths

- The large number of actors involved and responsible for substance and product manufacturing and application, as well as for wastewater treatment and water protection measures, along with the large number of different areas of chemicals and water regulation

- Such a dialogue process makes it possible to involve all relevant stakeholders from the very beginning.

- Through the joint technical discussions, a common understanding of the problem can be achieved, even if the initial situations and general conditions differ significantly among the various groups of actors.

- Solutions developed jointly in a discourse also receive high levels of acceptance in terms of further implementation.

- A joint dialogue with the government and administration means that those involved are aware of political decisions at an early stage and can adapt to future developments at an early stage, for example, in product developments or investment decisions.

- If the dialogue process is successful, improvements can be achieved in the short term, for example, through voluntary measures that can be implemented quickly by the stakeholders.

- A dialogue process also provides opportunities to identify problems that cannot be solved within the framework of the process or starting points or measures for which no consensus can be reached, and to highlight the additional need for political action that may be associated with them.

- Separation of factual and relationship levels, supported by professional moderation

- High levels of transparency both within the process (interests of the stakeholders, processed, for example, in the course of preliminary discussions with the stakeholders; processing of internal information and materials) and outside the process (documentation and publication of agreed results)

- Competence: Technical support of the process to identify and describe new starting points and solutions, with additional involvement of external experts, if necessary, e.g., via the UBA

- Efficiency of the process: Ensuring the most efficient processing possible, e.g., by delegating detailed work to separate working groups and providing professional support for the overall process

- Legitimacy: Especially at the beginning, but also in the further course of the process, clarification of the mandate and the internal legitimacy for the individual stakeholder groups in order to ensure a binding nature of the solutions to be developed

- Fairness and mutual trust: Ensuring fair and appreciative interaction with each other through jointly developed rules and compliance with them via independent moderation; protected, non-public space for building trust within the framework of the dialogue

2.2. Stakeholder Dialogue: Process Design

2.2.1. Preparation Phase

- Preparatory interest analysis based on exploratory talks with target groups of the dialogue (cross-section of authorities, manufacturing and application companies and actors, trade associations, environmental and consumer protection associations and technical experts from the fields of action pharmaceuticals, plant protection, biocides, detergents/cleaning agents, cosmetics, industrial cleaning agents and surface treatment).

- Identify stakeholders’ concerns and interests and their potential contributions to achieve potential objectives (good water status, precautionary principle and state of the art/best available technology)

- Development of a catalog of fundamentally suitable measures for dealing with micropollutants on the basis of the expert discussions and supplementary literature evaluations. The list of suggestions served, among other things, as a basis for the selection of stakeholders. The stakeholders were also to be given the opportunity during the exploratory phase to contribute their own proposals for measures and to name taboo topics (measures that, from the point of view of individual stakeholders, are not negotiable).

- Involvement of all relevant stakeholders representing those responsible for causing or solving the problem, associations from the fields of civil society and environmental protection, as well as the federal states responsible for reducing pollution in administrative enforcement (business associations, health sector, environmental and consumer protection, companies, water management, municipalities, involvement of other authorities). In addition, the process was accompanied by other federal ministries.

- Establishing clear rules for communicating (interim) results and agreeing on proposed measures. The aim was to achieve a trusting approach to proposals and impact assessments as quickly as possible as part of the stakeholder dialogue.

- Monitoring of the process with strict separation of roles between Fraunhofer ISI (scientific support, background papers, technical support for work assignments and working groups) and IKU (process management in dialogue).

- The sector of water distribution and wastewater management via the representative German water associations (‘Water res. man.’ in Figure 3)

- Producers and professional users of substances that can lead to micropollutants if they are emitted into water bodies (human pharmaceuticals, biocides, crop protection products, industrial and household chemicals, personal care and laundry products) and products that contain said substances

- Local authorities with responsibility for the control of substance emissions and the German Working Group on Water Issues (Bund/Länder-Arbeitsgemeinschaft Wasser, LAWA) of the Federal States and the federal government represented by the Federal Environment Ministry

- NGOs as representatives for the environment and civil society (‘Civil society’ in Figure 3)

2.2.2. Phase 1

- Mitigation strategies at the sources (January 2017)

- Mitigation strategies in application (February 2017)

- Possibilities of downstream (“end-of-pipe”) measures (March 2017)

- An additional workshop was held in May 2017 to consolidate the results

2.2.3. Phase 2

2.2.4. Pilot Phase

- Preparations were made for the establishment of the German Centre for Micropollutants at the UBA to ensure the exchange of information and experience between the actors and to be able to support further steps and activities via a central coordinating body.

- An expert panel was established to issue final decisions on the relevance of micropollutants that are assessed by the UBA.

- The instrument of the roundtables was used to identify relevant prevention and reduction measures for specific substances or groups of substances within the framework of producer responsibility and to initiate their implementation. Roundtables were initiated for a total of three micropollutants/micropollutant groups.

- The developed “orientation framework” for advanced wastewater treatment was tested by the federal states.

- In order to achieve a common communication strategy, the BMUV prepared the consolidation of activities under the umbrella of the UN Water Decade (2018–2028) (https://wateractiondecade.org/, last accessed on 24 March 2022).

- The various activities of the different dialogue phases that have taken place up to this point were assessed as part of a comprehensive evaluation by the stakeholders involved in the development and implementation of the activities. A particular focus was placed on the entire process as well as on the expectations regarding the achievement of objectives and the evaluation of the results achieved.

2.2.5. Consolidation Phase

2.3. Evaluation

- End of 2020: Evaluation surveys (online) of the participants of the Round Table RKM, as it was the first roundtable to start, as well as of the Panel for the Assessment of the Relevance of Trace Substances

- February 2021: Comprehensive survey (online) of the participants of the different dialogue phases as well as of the members of the roundtables to evaluate the interim status of the process achieved at that time (with differentiation between process and result evaluation)

- March 2021: Presentation and discussion of the results as part of an event on the results of the pilot phase

- Continuation in 2022: Since only partial results of the roundtables were available at the beginning of 2021 and the work of the roundtables was continued very intensively in the further course of 2021, the evaluation of this instrument was extended. For this purpose, a workshop with representatives of all stakeholder groups and all roundtables was held on 4 March 2022. The results were presented and discussed at the review event on 22 March 2022.

- Federal states/environmental administration

- Manufacturers of relevant products (including business associations)

- Environmental associations and civil society

- Water management

- Others, including professional users, municipalities/communities (including municipal top associations), science/research

3. Results

3.1. Results of the Dialogue Process

- Implementation of The German Centre for Micropollutants (SZB):

- Implementation of an expert panel for the final decision on the relevance of micropollutants after assessment of the UBA:

- Installation of roundtables for selected micropollutants to engage responsibility of industry:

- X-ray contrast agents (Röntgen-Kontrastmittel, RKM): start date, December 2019

- Diclofenac: start date, November 2020

- Benzotriazole: start date, November 2020

- Information campaign(s) under the umbrella of the UN Water Action Decade:

- Application of the “orientation framework” for advanced wastewater treatment in the federal states:

- Funding:

- Open Government Partnership (OGP):

3.2. Results of Evaluation by the Engaged Stakeholders

- What is the relevance of current inputs into the environment or water bodies? To what extent are there information gaps that can be closed through cooperation between different stakeholders?

- To what extent do existing regulations already limit inputs to the environment or water bodies? Are currently existing gaps known?

- Are options for action known and how can they be assessed in terms of their effectiveness and feasibility? Are there opportunities to exert influence through information or awareness-raising measures, for example? Or are there known, specific obstacles to implementation that could be removed in the context of a roundtable?

4. Discussion and Recommendations

- The implementation of The German Centre for Micropollutants (SZB)

- The implementation of an expert panel for final decision-making on the relevance of micropollutants after assessment by the UBA

- The establishment of roundtables for selected micropollutants to engage responsibility of industry

- Information campaign(s) under the umbrella of the UN Water Action Decade

- The application of the “orientation framework” for advanced wastewater treatment in the federal states

- Discussing the topic of funding

- BMUV/UBA:

- Product manufacturers/industry:

- Federal states/environmental administration:

- Water management:

- Environmental associations/civil society:

- A dialogue process is an important and helpful instrument for complex issues, especially when there are a large number of stakeholders with very different interests and prior knowledge.

- As a result, a new approach and new instruments were developed so that flexible and short-term options for action are now available.

- It also makes sense to conduct an evaluation of the environmental improvements that have actually been achieved and to consolidate the process, in parallel to the further implementation of the measures. This may result in the need for further developments and adjustments of measures and instruments.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| ABL—Arbeitsgemeinschaft Bäuerliche Landwirtschaft e.V. |

| Landesapothekerkammer Baden-Württemberg |

| BAG SELBSTHILFE |

| BAH—Bundesverband der Arzneimittel-Hersteller e.V. |

| BASF SE |

| Bayer AG |

| BBU—Bundesverband Bürgerinitiativen Umweltschutz e.V. |

| BDEW—Bundesverband der Energie- und Wasserwirtschaft e.V. Niersverband für BDEW—Bundesverband der Energie- und Wasserwirtschaft e.V. |

| Currenta GmbH & Co. OHG für BDI—Bundesverband der Deutschen Industrie |

| BPI—Bundesverband der Pharmazeutischen Industrie e.V. |

| BUND—Bund für Umwelt und Naturschutz Deutschland |

| Umweltministerium Hessen für Bund-/Länderarbeitsgemeinschaft Wasser (LAWA) Umweltministerium Nordrhein Westfalen (MULNV) für Bund-/Länderarbeitsgemeinschaft Wasser (LAWA) Umweltministerium Baden-Württemberg für Bund-/Länderarbeitsgemeinschaft Wasser (LAWA) |

| Deutsche Krankenhausgesellschaft e.V. |

| Deutscher Bauernverband e.V. |

| Deutscher Landkreistag |

| Deutscher Städte- und Gemeindebund |

| Deutscher Städtetag Stadtentwässerung Braunschweig für Deutscher Städtetag |

| DIHK—Deutscher Industrie- und Handelskammertag e.V. |

| DVGW—Deutscher Verein des Gas- und Wasserfaches e.V. |

| DWA—Deutsche Vereinigung für Wasserwirtschaft, Abwasser und Abfall e.V. |

| Gesamtverband der deutschen Textil- und Modeindustrie e. V. |

| IKW—Industrieverband Körperpflege- und Waschmittel e. V. |

| IVA—Industrieverband Agrar e.V. Bayer AG für IVA—Industrieverband Agrar e.V. |

| Pro Generika e.V. |

| VCI—Verband der Chemischen Industrie e.V. |

| ver.di Vereinte Dienstleistungsgewerkschaft |

| Verbraucherzentrale Bundesverband e.V. vzbv |

| vfa—Verband forschender Arzneimittelhersteller |

| VKU—Verband kommunaler Unternehmen Emschergenossenschaft/Lippeverband für VKU—Verband kommunaler Unternehmen |

References

- Domingo-Echaburu, S.; Dávalos, L.M.; Orive, G.; Lertxundi, U. Drug pollution & Sustainable Development Goals. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 800, 149412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillenbrand, T.; Niederste-Hollenberg, J.; Tettenborn, F. Verbesserung der Wasserqualität durch verringerte Einträge von Spurenstoffen. In Aktuelle Ansätze zur Umsetzung der UN-Nachhaltigkeitsziele; Leal Filho, W., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 291–312. ISBN 978-3-662-58716-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EEA. EEA-Report 18/2018: Chemicals in European Waters. 2018. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/chemicals-in-european-waters (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- EEA. EEA-Report 09/21: Drivers of and Pressures Arising from Selected Key Water Management Challenges—A European Overview. 2021. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/drivers-of-and-pressures-arising (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Ahting, M.; Brauer, F.; Duffek, A.; Ebert, I.; Eckhardt, A.; Hassold, E.; Helmecke, M.; Kirst, I.; Krause, B.; Lepom, P.; et al. Background Paper: Recommendations for Reducing Micropollutants in Waters; Helmecke, M., Ed.; German Environment Agency (Umweltbundesamt): Dessau, Germany, 2018; Available online: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/1410/publikationen/180709_uba_pos_mikroverunreinigung_en_bf.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Gimeno, S.; Komen, H.; Jobling, S.; Sumpter, J.; Bowmer, T. Demasculinisation of sexually mature male common carp, Cyprinus carpio, exposed to 4-tert-pentylphenol during spermatogenesis. Aquat. Toxicol. 1998, 43, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodin, T.; Fick, J.; Jonsson, M.; Klaminder, J. Dilute Concentrations of a Psychiatric Drug Alter Behavior of Fish from Natural Populations. Science 2013, 339, 814–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benotti, M.J.; Trenholm, R.A.; Vanderford, B.J.; Holady, J.C.; Stanford, B.D.; Snyder, S.A. Pharmaceuticals and endocrine disrupting compounds in U.S. drinking water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotruvo, J.A. Organic micropollutants in drinking water: An overview. Sci. Total Environ. 1985, 47, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mompelat, S.; Le Bot, B.; Thomas, O. Occurrence and fate of pharmaceutical products and by-products, from resource to drinking water. Environ. Int. 2009, 35, 803–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zylka-Menhorn, V. Arzneimittelrückstände im Wasser: Vermeidung und Elimination. Dtsch. Ärzteblatt 2018, 115, 1054–1056. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Hollert, H.; Zhou, S.; Deutschmann, B.; Seiler, T.B. Toxicity of 10 organic micropollutants and their mixture: Implications for aquatic risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 666, 1273–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschke, S.; Franke, C.; Newig, J.; Borchardt, D. Clusters of water governance problems and their effects on policy delivery. Policy Soc. 2019, 38, 255–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschke, S.; Kosow, H. Designing policy mixes for emerging wicked problems. The case of pharmaceutical residues in freshwaters. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2022, 24, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaub, S.; Vogeler, C.; Metz, F. Designing policy mixes for the sustainable management of water resources. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2022, 24, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillenbrand, T.; Tettenborn, F.; Menger-Krug, E.; Marscheider-Weidemann, F.; Fuchs, S.; Toshovski, S.; Kittlaus, S.; Metzger, S.; Tjoeng, I.; Wermter, P.; et al. Measures to Reduce Micropollutant Emissions to Water—Summary; Texte 87/2014; Umweltbundesamt: Berlin, Germany, 2015; 25p, Available online: http://www.umweltbundesamt.de/publikationen/measures-to-reduce-micropollutant-emissions-to (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- UBA. Organische Mikroverunreinigungen in Gewässern Vierte Reinigungsstufe für weniger Einträge; Rechenberg, B., Ed.; German Environment Agency (Umweltbundesamt): Dessau, Germany, 2015. Available online: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/publikationen/organische-mikroverunreinigungen-in-gewaessern (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Hillenbrand, T.; Tettenborn, F.; Fuchs, S.; Toshovski, S.; Metzger, S.; Tjoeng, I.; Wermter, P.; Kerstin, M.; Hecht, D.; Werbeck, N.; et al. Measures to Reduce the Entry of Micropollutants into Surface Water—Phase 2 [In German: Maßnahmen zur Verminderung des Eintrages von Mikroschadstoffen in die Gewässer—Phase 2]; Texte 60/2016; Umweltbundesamt: Berlin, Germany, 2016; 235p, Available online: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/377/publikationen/mikroschadstoffen_in_die_gewasser-phase_2.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Dietz, T.; Stern, P.C. (Eds.) Public Participation in Environmental Assessment and Decision-Making. Panel on Public Participation in Environmental Assessment and Decision Making; National Research Council; National Academic Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2008.

- Newig, J.; Challies, E.; Jager, N.W.; Kochskämper, E.; Adzersen, A. The Environmental Performance of Participatory and Collaborative Governance: A Framework of Causal Mechanisms. Policy Stud. J. 2018, 46, 269–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachs, J.D.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Mazzucato, M.; Messner, D.; Nakicenovic, N.; Rockström, J. Six Transformations to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Environment. Global Environmental Outlook—GEO-6: Healthy Planet, Healthy People; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Eckerd, A.; Heidelberg, R.L. Administering Public Participation. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2020, 50, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, J. Zur Verantwortung für Spurenstoffe—Von den ethischen Grundlagen zur Herstellerverantwortung im Wasserrecht. Umweltrechtliche Beiträge Wiss. Prax. 2021, 11, 98–108. [Google Scholar]

- Metz, F.; Ingold, K. Politics of the precautionary principle: Assessing actors’ preferences in water protection policy. Policy Sci. 2017, 50, 721–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klauer, B.; Aicher, C.; Bratan, T.; Eberle, U.; Hillenbrand, T.; Kümmerer, K.; Reuter, W.; Schiller, J.; Schulte-Römer, N.; Schramm, E.; et al. Arzneimittelrückstände in Trinkwasser und Gewässern. Endbericht zum TA-Projekt. TAB-Arbeitsbericht Nr. 183. 2019. Available online: https://publikationen.bibliothek.kit.edu/1000134593/122591855(accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Aus der Beek, T.; Weber, F.; Bergmann, A.; Hickmann, S.; Ebert, I.; Hein, A.; Küster, A. Pharmaceuticals in the environment—Global occurrences and perspectives. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2016, 35, 823–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Pharmaceutical Residues in Freshwater: Hazards and Policy Responses; OECD Studies on Water; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, T. Regulierung im Dialog: Stakeholdermanagement bei Regierung und Verwaltung. Uwf UmweltWirtschaftsForum 2013, 21, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Van Fleet, D.D.; Cory, K.D. Raising rivals’ costs through political strategy: An extension of resource-based theory. J. Manag. Stud. 2002, 39, 707–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.; Ury, W.; Patton, B. Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement without Giving, 3rd ed.; Penguin Books: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 9780143118756. [Google Scholar]

- Riede, M. Determinanten erfolgreicher Stakeholderdialoge. Erfolgsfaktoren von Dialogverfahren zwischen Unternehmen und Nicht-Regierungsorganisationen. UWF 2013, 21, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillenbrand, T.; Tettenborn, F.; Bloser, M. Stakeholder-Dialog Spurenstoffstrategie—Organisation, Durchführung und Auswertung eines Stakeholder-Dialogs zur Deutschen Spurenstoffstrategie; UBA-Texte; Umweltbundesamt: Dessau, Germany, 2023.

- BMUB/UBA. Policy Paper. Recommendations from the Multi-Stakeholder Dialogue on the Trace Substance Strategy of the German Federal Government to Policy-Makers on Options to Reduce Trace Substance Inputs to the Aquatic Environment. Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz, Bau und Reaktorsicherheit: Bonn, Germany; Umweltbundesamt: Dessau, Germany, 2017; 33p. Available online: http://www.bmu.de/fileadmin/Daten_BMU/Download_PDF/Binnengewaesser/spurenstoffstrategie_policy_paper_en_bf.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- BMU/UBA. Ergebnispapier—Ergebnisse der Phase 2 des Stakeholder-Dialogs »Spurenstoffstrategie des Bundes« zur Umsetzung von Maßnahmen für die Reduktion von Spurenstoffeinträgen in die Gewässer; Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz und nukleare Sicherheit: Bonn, Germany; Umweltbundesamt: Dessau, Germany, 2019; 65p, (In German). Available online: https://www.dialog-spurenstoffstrategie.de/spurenstoffe-wAssets/docs/ergebnispapier_stakeholder_dialog_phase2_bf.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Schaub, S.; Tosun, J. Politikgestaltung im Dialog? Umweltgruppen und ihre Mitwirkung bei der Regulierung von Spurenstoffen in Gewässern. Z. Für Polit. 2021, 31, 291–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newig, J.; Jager, N.W.; Challies, E.; Kochskämper, E. Does stakeholder participation improve environmental governance? Evidence from a meta-analysis of 305 case studies. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2023, 82, 102705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaub, S.; Braunbeck, T. Transition towards sustainable pharmacy? The influence of public debates on policy responses to pharmaceutical contaminants in water. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2020, 32, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BMUV. National Water Strategy—Draft of the Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety; BMUV: Berlin, Germany, 2021. Available online: https://www.bmuv.de/fileadmin/Daten_BMU/Download_PDF/Binnengewaesser/langfassung_wasserstrategie_en_bf.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2023).

| X-ray Contrast Agents (RKM) | Diclofenac | Benzotriazole | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Addressing information deficits | Significance of emissions during production/processing Feasibility of the urine collection concept (→ Study) | Need for awareness-raising among doctors, pharmacists, users Emissions with topical application (→ Study) | Test procedure Stiftung Warentest Relevance of different application areas (Symposium, Cooling lubricant → Study) |

| Measures | (Measures during production/processing) Awareness-raising measures Pilot projects: broad application of the urine collection concept | Information measures regarding topical application (“wiping instead of washing”) Publications and awareness-raising activities Pilot studies with project advisory board | Further development of test procedures (with the involvement of manufacturers) until end of 2022 General awareness-raising measures Targeted information in application sectors |

| Implementation | Partly already being implemented, pilot projects from the end of 2022 | Partly already being implemented, three pilot studies from 2022/2023 onward | Partly already being implemented |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hillenbrand, T.; Tettenborn, F.; Bloser, M.; Luther, S.; Eisenträger, A.; Kubelt, J.; Rechenberg, J. Engaging Stakeholders to Solve Complex Environmental Problems Using the Example of Micropollutants. Water 2023, 15, 3441. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15193441

Hillenbrand T, Tettenborn F, Bloser M, Luther S, Eisenträger A, Kubelt J, Rechenberg J. Engaging Stakeholders to Solve Complex Environmental Problems Using the Example of Micropollutants. Water. 2023; 15(19):3441. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15193441

Chicago/Turabian StyleHillenbrand, Thomas, Felix Tettenborn, Marcus Bloser, Stephan Luther, Adolf Eisenträger, Janek Kubelt, and Jörg Rechenberg. 2023. "Engaging Stakeholders to Solve Complex Environmental Problems Using the Example of Micropollutants" Water 15, no. 19: 3441. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15193441

APA StyleHillenbrand, T., Tettenborn, F., Bloser, M., Luther, S., Eisenträger, A., Kubelt, J., & Rechenberg, J. (2023). Engaging Stakeholders to Solve Complex Environmental Problems Using the Example of Micropollutants. Water, 15(19), 3441. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15193441