Abstract

Watershed eco-compensation (WEC) is considered a significant environmental policy instrument for watershed ecological protection and management. However, in the legislation and practice of eco-compensation in China, the development of the WEC mechanism is still in the initial stages. In this paper, the institutional opportunities and challenges of WEC are analyzed from the existing policies, laws, and economical instruments. Theoretically, WEC in China has seen a combination of punitive-based “Watershed Ecological Damage Compensation (WEDC)” and incentive-based “Watershed Ecological Protective Compensation (WEPC)”. Through a comparative analysis of domestic and foreign watershed compensation practices, the results demonstrate that most of China’s WEC projects have an insufficient legal basis, a single compensatory subject, insufficient compensation funds, and an imperfect market-oriented compensation mechanism. To improve watershed eco-compensation in China, it is recommended to strengthen legislation, select diversified eco-compensation approaches, and establish a market-based and systematic eco-compensation mechanism for watersheds.

1. Introduction

The watershed’s ecological environment and water resources contribute significantly to agricultural production and the people’s well-being [1,2]. However, excessive exploitation and utilization of watersheds harm the watershed ecosystem environment. The reduction in biodiversity, water quality degradation, and decline in ecosystem stability have become severe [3,4,5]. Watersheds are typically public goods for both the upstream and downstream, evidently characterized by non-competitiveness and non-exclusiveness. Therefore, the externalities lie in the public goods, evidently characterized by non-competitiveness and non-exclusiveness. On one hand, for instance, soil conservation and afforestation may generate positive externalities in the watershed ecosystem; on the other hand, phenomena such as discharge pollution and excessive exploitation and utilization have negative externalities in the watershed ecosystem. It is unrealistic to achieve zero externalities [6,7].

Moreover, externalities are often overlooked in individual economic decisions [8]. Meanwhile, it is just for the two attributes of public goods that there will be the phenomena of “public tragedy” and “free-riding” during the use of watershed resources [9,10]. Watershed eco-compensation (WEC) is widely accepted as an effective method for internalizing environmental externalities of conservation and as an economic facilitator of ecological environment management [11,12,13,14,15,16]. Compensatory mechanisms protect natural resources, biodiversity, ecosystem balance, ecological function, ecosystem services, and other ecological values [17,18,19]. Take Xin’an River as an example; without WEC, developers may damage the ecosystem because they can benefit from the ecosystem and evade responsibility for their negative environmental externalities. Meanwhile, ecosystem protectors don’t have incentives to protect the environment from which they are unlikely to benefit [20]. Thus, ecological conservation has increasingly promoted the compensatory mechanism [21]. According to the statistics, at least 56 countries have laws and policies in place that are needed for compensatory environmental protection [22].

Eco-compensation is a combination of “Ecological Compensation (EC)” and “payments for ecosystem services (PES)” in China [23]. It can be seen in Table 1. EC is a required compensatory method to internalize negative environmental externalities, and its history is concise. EC of wetlands came into existence in the 1970s in America [24]. At present, ecological compensation is frequently applied worldwide [25]. For instance, the German Federal Nature Conservation Act required compensatory measures to be taken to keep the essential functions in nature and landscapes unaltered after a project in 1976. In 2011, there was a New Zealand ecological compensation proposal for Mt. Cass Wind Farm. In 2017, EC policy applied to the Fen River in Shanxi Province in China aimed to control water pollution. Meanwhile, PES are a voluntary deal between suppliers and purchasers through clearly defined environmental services for continuously secured provisions [26]. Additionally, PES are applied to internalize positive environmental externalities and carried out in other countries. However, they are a relatively new economic instrument. Moreover, PES are based on the principle that the beneficiary pays rather than the polluter [20,27]. In reality, most PES cases cannot be applied to all standards in the definition and are closer to the revised “PES-like” cases [28,29].

Table 1.

Comparison of theoretical backgrounds of punitive-based and incentive-based eco-compensation in China.

EC and PES have played an essential role in China’s environmental management [30]. At present, the focus of WEC research is on the governance compensation model for the water environment from upstream to a downstream area of the watershed [24,31]. The WEC instrument is classified into two types in China: watershed ecological damage compensation (WEDC) and watershed ecological protective compensation (WEPC). WEDC refers to ecological loss from development and utilization activities conducted according to the law and does not include damage caused by watershed pollution or illegal activities [32,33]. It was conceived as being punitive-based to internalize negative environmental externalities and follow the polluter-pays principle in China.

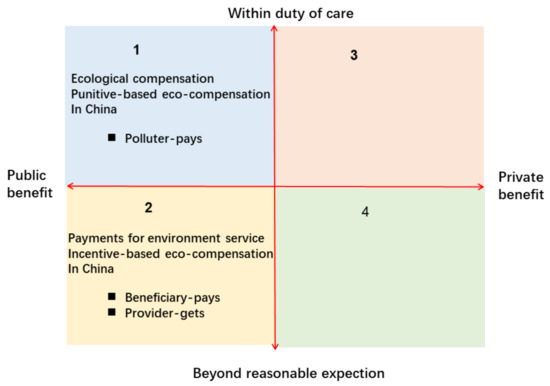

On the other hand, WEPC was designed as an incentive-based policy to internalize positive environmental externalities, following China’s beneficiary-pays and provider-gets principles (Figure 1) [34]. As a result, WEC has received wide attention as an innovative environmental protection policy. Well-designed policies and mechanisms will effectively reduce hitchhiking in the watershed environment and ameliorate water quantity and quality [12,16]. However, policies and laws relevant to WEC are still imperfect in China, especially the lack of economic policies, resulting in an unequal allocation of ecological and financial benefits among victims, protectors and beneficiaries [10]. In addition, the conflicts of interest in transboundary river basin pollution highlight China’s ecological governance strategies [35].

Figure 1.

The benefits flow and property rights matrix: interest distribution by property rights and obligations and major policy choices [34]. In China, on the one hand, EC and punitive-based eco-compensation are adopted in the first quadrant, following the polluter-pays principle. On the other hand, PES and incentive-based eco-compensation are adopted in the second quadrant, according to the beneficiary-pays and provider-gets principles.

Moreover, a few previous surveys and optimal pollution control policies have been combined with the trans-regional water environmental preferences by using different game methods [36,37], particularly with eco-compensation criteria, and it is challenging to effectively solve the problem of transboundary watershed pollution [38]. In response to this issue, the General Office of the State Council of China officially enacted the “Opinions on Improving Ecological Protection Mechanism” in May 2016. Hence, it is essential to construct a WEC mechanism conducive to dealing with the environmental protection and economic development relationships between upper and lower reaches, achieving sustainable development of the whole watershed.

This paper summarized and discussed the present policies, laws, and economic instruments relevant to WEC in China and PWES projects abroad based on the official documents and data. Moreover, the analysis of gaps and challenges in the existing institutional system also implicates the need and potential of the WEC mechanism for future development. Then, we conducted a comprehensive investigation of WEC practice from two aspects of WEDC and WEPC in China and discussed the fundamental impact factors—for instance, the mission, stakeholders, approaches, and modalities. At the end of the paper, it was proposed to explore new ideas and methods for bidirectional WEC research and construct diversified and market-based systematic WEC mechanisms in China.

2. Material and Methods

In recent years, the concept of EC has been applied widely as a state policy and legal regime in the governance of watersheds. This review first analyzed the primary federal policy and development planning files related to watershed protection in the last few years. Since the1990s, watershed pilot projects have been implemented in many provinces, including but not limited to the main streams and tributaries of major river basins, such as the Yellow River, Yangtze River, and Huai River, and crucial lakes [10]. However, these pilot projects have not had legal support until the revised Environmental Protection Law of 2014. One of them formally provided a legal basis and stipulated that “the State establishes a sound the ecological compensation policy”.

Meanwhile, the local and central governments must provide funding and encourage local governments to develop market-oriented cooperation [39]. In 2019, President Xi Jinping proposed that the Yellow River watershed’s ecological protection and high-quality development should rise as a national strategy. These analyses mainly concentrated on goals and management policies relevant to WEC (Table 2) and understanding the ecological situation as well as the highest level of compensation in the overall state policies for development goals. This critical legal backing would prepare for an even more comprehensive application of EWS or other eco-compensation policies in China.

Table 2.

Primary policy documents and contents related to the WEC.

Furthermore, provisions related to water environment protection were analyzed via collecting direct legal origins of EC, such as fundamental legislation and regulations for ecological protection of watersheds, to elaborate and summarize the legal infrastructure and implementation foundations of WEC (Table 3). Examining critical regulations and laws can illuminate the existing framework of the legal system, analyze the gaps between legislation and application, and determine the potential for future enhancements.

Table 3.

Overview of current laws and regulations concerning WEC.

Economic instruments play a role in improving and innovating ecological compensation methods in management practices [40]. The existing mechanism is essential for reconciling economic development and watershed environmental protection. Last but not least, this study investigates other management instruments concerning watershed eco-compensation, including water–pollution emission transactions, transboundary water pollution, water use rights transactions, water resource protection, green credit, pollution levy, pollution discharge rights trading, and the compensated use of emissions rights and environmental pollution responsibility insurance. The primary analysis factors include applicable principles, competent sectors, relevant regulations, calculation methods, and eco-compensation-relevant expenditures in watershed ecological system protection (Table 4). The leading systemic weaknesses and challenges are condensed and analyzed based on the information and the data of the laws mentioned above and relevant tools.

Table 4.

Economic instruments relevant to WEC in China.

To achieve a thorough understanding of the external circumstances for WEC system construction, this section also systematically lists information related to policy developments, reflecting the favorable political circumstances and development opportunities for constructing the WEC systems. Finally, we assess the advancements of China’s WEC practices and construct the WEC system. The authors have been closely followed the development of eco-compensation for watershed services pilot schemes in China since 2008, covering the significant policies and legislative documents, the funding sources for WEC, the principles and approaches of EWS, and requirements and measures (Table 5). However, some provinces have not enacted comprehensive policies and regulations. The authors collected related data and information employing field investigations and pilot schemes. This review analyzes the practice’s efficiency from some notable factors of the WEC system (covering goals and missions, stakeholders, approaches, and measures). The comprehensive analysis and arrangement of the information will contribute to the formulation of feasible responses and recommendations for improving the WEC system.

Table 5.

The WEDC pilot schemes in China.

3. WCE Policies, Legal Basis and Economic Instruments in China

3.1. Policies and Legal Framework of WEC in China

Compared with developed countries, China faces more handicaps for water quality management because of imperfectly designed regulations and policies [33,35] China has not yet drawn up special rules and laws on WEC. The related characterization of the crucial national policy files and regulations in the fundamental laws of watershed conservation can offer a legal basis, policy background, and political impetus for establishing the WEC mechanism.

3.1.1. Policies of WEC in China

The policy of WEC has gained popularity in watershed water quality management in China, which focused on relevant watershed pollution and ecosystem services and encouraged upstream and downstream cooperation [40]. Since 2012, establishing an EC mechanism has been formally confirmed as one of the critical goals for developing China’s ecological civilization system. The eco-compensation instrument is available in the primary policy files around the strategic planning for socio-economic development and the establishment of ecological civilization. The reports of the National Congress of the Communist Party of China provide an overview of eco-compensation mechanisms. The Decrees of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and Outline of the 13th and 14th Five-Year Plans of National Economic and Social Development of China have laid the policy foundation for constructing and improving the WEC mechanism.

The related concepts, methods, and priorities are elaborated on in the different policy files at the top level, illustrating orientations and goals of formulating future administrative and legislative measures from the above-mentioned significant files. In addition, WEC is considered an important measure to stimulate the establishment of China’s ecological civilization. Therefore, the development objectives and general framework for establishing WEC mechanisms are explicit and distinct. Therefore, the primary mission for improving management and legislation is to develop a government-led, public-participatory, and market-oriented WEC mechanism, which should have effective actions, fair results, and sufficient funding sources.

3.1.2. Legal Basis of WEC in China

The Environmental Protection Law (EPL), the Water Law, the Law on Prevention and Control of Water Pollution of the People’s Republic of China, and the Guiding Opinions on Accelerating the Establishment of River Basin Upstream and Downstream Lateral Ecological Compensation Mechanism provide a significant legal foundation for WEC. These fundamental laws stipulate the general duties of enterprises and individuals to mitigate, control, and prevent watershed environmental ecosystem destruction. Furthermore, the Law on Prevention and Control of Water Pollution of the People’s Republic of China highlights the river leader’s responsibility for managing and organizing water resource protection of rivers and lakes, water pollution prevention, waterfront management, and water environment management within the administrative region in stages. Generally, a series of related provisions in industry regulations and legislation on watershed ecosystem protection, management, and rehabilitation has constituted the legal infrastructure of WEC.

In short, attention should be paid to protecting river basin sources and transboundary river basins as well as planning and applying protection and governance methods for development activities in the functional protection zone. Furthermore, according to the Environmental Protection Law (2014) and the Law on Prevention and Control of Water Pollution (2018), the government has the leading role and primary responsibility in establishing and improving the eco-compensation system. Notably, a means of financial transfer payment with funds in compensation is also essential.

In the field of WEC development and utilization, WEC has been closely associated with the environmental impact assessment (EIA) system [41,42,43]. According to China’s watershed EIA system, large-scale water conservancy construction should be predicted and assessed for ecological security risks before the EIA to avoid causing ecological degradation. After its completion, a certain percentage of its profits should be used to repair the environment. If the conservation, restoration, or eco-compensation approaches ineffectively control and prevent the damage to the watershed ecosystem, in that case, the competent authorities will not approve the EIA. Regarding the restoration of ecological damage in the watershed, the main forms of statutory liability include restoration, civil compensation, criminal liability, and compulsory administrative measures.

According to the laws and regulations mentioned above, one can conclude that those who cause cross-basin water pollution must bear responsibility for compensation, which reveals the principle in the environmental legislation. In other words, whoever caused pollution must handle the pollution. The downstream economic loss should be compensated by upstream polluters, complying with the regulations mentioned earlier. Therefore, China’s WEC has a profound legal basis.

WEDC mainly focuses on the compensation mechanism for downstream environmental damage and pollution losses caused by upstream sewage discharge; this is an up-and-down compensation mode. On the other hand, WEPC is primarily concerned with the compensation mechanism for the upstream protection and governance of the watershed so that the downstream can enjoy good water quality. Therefore, it is a down-to-up compensation mode [44]. Thus, the combined use of WEDC and WEPC will positively impact the use of natural resources and minimize the externalities of the ecological environment.

3.1.3. Relevant Economic Instruments in WEC

The economic tools of WEC function mainly consist of the river occupation fee, the river engineering construction and maintenance fees, the sand mining management fee in a river, and the environmental protection tax (covering the costs of dumping and discharging pollutants) in China (Table 4). These economic tools are the primary sources of financial income.

Specifically, first, the river occupation fee refers to the units and individuals involved in engineering construction projects and other facilities paying fees to the water conservancy department for occupying water surface, river beach, and embankments within the scope of river management. The fee is calculated according to the actual area of the water surface, river beach land, and embankment land occupied by the project. Second, river engineering construction and maintenance management fees refer to the fees that industrial and commercial enterprises, farmers, and individual industrial and commercial households should pay to the river competent authority for the construction, maintenance, and management of river projects within the scope of benefits from embankments, revetments, irrigation and drainage sluice gates, dikes, and waterlogging drainage facilities. The levy standard shall be determined according to the project construction and maintenance management fees. The specific standards and methods of charging shall be determined by the people’s governments of provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities directly under the central government. Enterprises with sales and operating income shall be levied at 1‰ of monthly sales or operating income. For large commercial enterprises with a sales volume of more than CNY 10 million and a price difference rate of less than 10% in the previous year, it is calculated by 0.5‰ of the monthly sales volume. River engineering construction and maintenance management fees belong to local fiscal revenue, and the local tax rates are different. Third, the sand mining management fee in the river refers to the sand mining, earth borrowing, and gold panning within the scope of river management that must be carried out following the approved scope and operation mode, and the management fee must be paid to the river competent authority. The charging standard of the river sand mining management fee shall be reported by the water conservancy departments of all provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities directly under the central government to the price and financial departments at the same level for verification. For example, the Tianjin Water Resources Bureau will charge the unit issuing the river sand and soil sampling license at the standard of no more than CNY 0.70 per cubic meter, and the stone will be charged at 10–25% of the local sales price of the quarry. Fourth, the environment protection tax is formulated to protect and improve the environment, reduce pollutant emissions, and promote the construction of ecological civilization. According to the provisions of the environmental protection tax law, the tax basis for taxable air pollutants and water pollutants shall be determined according to the pollution equivalent converted by the pollutant emission, the tax basis for taxable solid waste shall be determined according to the emission of solid waste, and the tax basis for taxable noise shall be determined according to the decibel exceeding the national standard.

However, the principle, relevant regulations, competitive sectors, and calculation basis of fee amounts of each economic instrument are different (Table 4). The relevant subjects of obligations are directly reflected following the principles applicable to the four economic instruments. These economic tools with different focuses and goals are implemented according to various legal regulations. Each evaluation criterion is used for each economic instrument in terms of calculation methods. The calculation of the number of charges is mainly according to the elements of ecological environment management rather than integrating all the ecosystem elements. The effectiveness of eco-compensation will be affected by the difference in the fiscal revenues used for eco-compensation. Both the river occupation fees and the river’s sand mining management fees are natural resource revenue. A large portion of the revenue is used to conserve the ecological environment or resources of the watershed. This revenue cannot be spent on ecological compensation in other areas. The fiscal administration system manages the river area’s use fee and environmental protection taxes. Therefore, the expenditure should be assigned in accordance with the government budget rather than being dedicated to ecological rehabilitation such as the river sand mining management fee, river resource fee, and compensation for damage to river basin protection.

3.2. Discussion of Significant Challenges and Opportunities

3.2.1. Discussion of Significant Challenges in WEC

It will be impossible to construct watershed eco-compensation without investigating the effectiveness and adequacy of existing legislation and policies. According to the present and long-term political situation, the establishment and improvement of the WEC mechanism face many challenges.

Firstly, according to the present situation, China does not have complete regulations and laws, nor does it specialized and national-level legislation. It shows that the WEC regulations in the above-collected government files may not be faithfully carried out in reality. The regulations and policies of WEC are formulated mainly by administrative departments and regional governments according to their demands. Therefore, their authority and constraint are restricted. The requirements of present regulations and policies for WEC are prescribed in principle, but they can’t provide specific and direct guidance for WEC implementation. Therefore, relevant practices will inevitably face legality issues without sufficient legal foundation from upper-level law.

Second, compared with foreign PWES projects, China’s eco-compensation is still the government-led model and lacks market-led model eco-compensation in the watershed, and the WEC model is relatively rare [45,46,47]. The government-led eco-compensation model has deficiencies, as follows. First of all, the importance of eco-compensation is closely related to the recognition of local managers. Therefore, changes in managerial positions will affect the stability of eco-compensation-related policies and measures. Furthermore, the primary funds of WEC only relying on government financial transfer payments will lead to a shortage of compensation funds. Therefore, it is tough to maintain eco-compensation development and project construction in the watershed.

Thirdly, the existing economic tools are insufficient for WEC. On one hand, although the river occupation fee includes the cost of ecological environment damage, the proportion of funds for watershed ecological restoration is flexible. According to the financial management system for watershed environmental restoration, a complex approval process is required, from the assessment of the budget for watershed ecological damage to the implementation of watershed environmental restoration. Therefore, the time lag of WEC is not promptly beneficial to the rehabilitation of the damaged watershed ecological environment. On the other hand, since each type of economic instrument mentioned in Table 4 is adopted and managed by different watershed departments, the collection, management, and use of the special funds are restricted to a specific scope. Aspects such as the water resource revenue and taxation being included in the government’s revenue and expenditure budget management system should be planned in an integrated manner in terms of investment scope. Meanwhile, the proportion and scope of the watershed environmental protection expenditures change every year. In conclusion, the available sources of WEC funds cannot be managed in an overall manner, forming a steady and lasting WEC fund support rather than only playing a supplementary function.

Fourthly, the available economic instruments in China have developed their corresponding technical criteria, but the calculation basis and methods of the fees are not uniform (Table 4). On the one hand, because of the absence of comprehensive watershed-ecosystem-based assessment methods and compensation standards for ecological losses, the results for the demonstration practices are unsatisfactory, which must be adjusted and improved. On the other hand, it also reveals the flexibilities of the WEC mechanism, which requires careful consideration of natural conditions, the level of productivity, the intensity of utilization and development, the management level and capacity of the watershed, and other factors.

3.2.2. Political Dynamics and Opportunities in WEC

The WEC mechanism aims to solve the problems faced by ecological environment protection and governance of watersheds and adjust and balance the environmental and economic interests of the upstream and downstream of the river basin. Moreover, it can mobilize stakeholders’ enthusiasm for watershed protection and governance. The WEC mechanism has been incorporated into the national watershed ecosystem protection and strategic development layout. The Chinese government has put forward a scientific development concept. It insists on people-centered, integrated, coordinated, and sustainable development through various policies and measures, attaches great importance to ecological construction, and significantly contributes to improving the country’s environmental conditions [45]. From this point of view, the current national strategic concept of watershed management and administration will provide impetus and opportunities for constructing and developing the WEC mechanism.

Firstly, The Chinese government has promulgated many policies and regulations concerning ecological civilization construction in the watershed. For example, the Environmental Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China, which was revised and passed in 2014, clearly stated the construction of an improved eco-compensation system and provided legal support for the eco-compensation practice [46]. Furthermore, President Xi Jinping proposed at the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China that establishing a market-based and diversified eco-compensation mechanism pointed in the direction of developing the eco-compensation mechanism [47]. Therefore, the decision-making level has a strong political will and would like to place more emphasis on the exploration and demonstration practice of the environmental protection mechanism; it will be conducive to accelerating the process of the institutionalization of WEC.

Secondly, China is making new reforms to its watershed governance system. In 2019, nine departments, including the National Development and Reform Commission, the Ministry of Finance, and the Ministry of Natural Resources, jointly issued and implemented the “Action Plan for Establishing a Market-oriented and Diversified Ecological Protection Compensation Mechanism”, which designed and arranged the promotion measures and other aspects. It aims to realize the market-oriented operation and diversified participation of the eco-compensation system and promote the proper operation of WEC. Diversified participation and a coordinated watershed administration system will be more beneficial to constructing watershed mechanisms and the legislation of WEC [48].

Thirdly, weak enforcement is the main reason that most existing watershed environmental protection policies and regulations have little practical effect. However, on one hand, the national environmental and river leader supervision system has promoted implementing the environmental protection responsibility system in the watershed. On the other hand, the protection of watershed ecological governance has become an essential indicator of the effectiveness assessment of government management. It is conducive to strengthening the political motivation of the relevant authorities to ensure environmental safety and maintain sustainable ecological services.

Under the current situation, cross-regional and transboundary eco-compensation pilot schemes have achieved significant results. A diversified eco-compensation mechanism has been initially established, and entities have fulfilled environmental protection responsibilities [49,50,51]. The function of government has changed from micro-regulation to enhancing the guidance and planning of macro-regulation. The emphasis of management has also changed from pre-permitting restriction to post-permitting supervision of the overall procedure. The effect has promoted the further improvement of the WEC mechanism. In addition, the more coordinated interaction between the environmental protectors and the beneficiaries in the watershed has provided strong policy support.

4. Domestic WEC and Foreign WEPS Practices and Comparisons

Building a WEC mechanism is essential to considering the overall situation according to the ecological priority and green development from the perspective of the comprehensive protection and sustainable utilization of the watershed ecosystem as a precondition to meeting the watershed’s economic and social development needs [49]. In addition, WEC should be guided by the national long-term strategic plan, and regional governments should adjust implementation strategies and explore regionally appropriate measures according to their own circumstances. Thus, the desire to pursue an excellent ecological environment in the watershed can be realized.

4.1. Current Practice of WEC in China

WEC mechanisms and policies have received widespread attention from society. Large amounts of funds, material resources, and labor have been invested in protecting the watershed ecosystem to ensure the ecological security of the watershed and the sustainable use of water resources. WEC is mainly implemented by the local and central governments, including government financial subsidies for critical ecological functional regions such as protecting water sources. Following the “Polluter pays” principle, WEDC(Table 5) is negotiated on and determined based on the cost of water pollution control and the economic loss caused by water resource protection. Most WEDC mechanisms are carried out according to the environmental control measures supervision system or the environmental impact assessment (EIA) framework. Compensation is usually implemented through negotiation under the supervision and guidance of the competent authority. However, the inter-regional agreements and cooperation reflect the market-oriented mechanism to some extent. Nevertheless, purely market-oriented or economic approaches have not been entirely applied [52,53,54,55,56] The governmental “red-headed” documents are the main forms that the higher-level government uses to formulate payment requirements and related compensation regulations. They represent official regulations and are an essential and ordinary means by which eco-compensation schemes originate in China.

The positive incentives mainly include social honor, financial rewards, and promotion. The downstream beneficiary should compensate upstream residents for their sacrifices to preserve the water ecological environment. In China, the WEPC (Table 6) mechanism has mainly been applied to compensation in transboundary watersheds, mainly through signed agreements and financial transfers between governments to achieve ecological protection of the watershed. The scope of WEPC implementation includes two provinces or two cities of a transboundary river. For example, the Anhui and Zhejiang provinces established a horizontal eco-compensation mechanism in the Xin’an watershed in 2011, and the Shandong and Henan provinces established a horizontal ecological compensation mechanism in the Yellow River Basin in 2021. In practice, adhering to the “Beneficiary compensates” modality, most WEPC cases are usually implemented by governmental financial assistance and subsidies.

Table 6.

The WEPC pilot schemes in China.

The punitive-based WEDC for construction programs concerns watershed users and related government departments. The negative incentives involve mandatory punitive measures, with priority given to administrative or economic penalties. Administrative penalties mainly involve the removal of officials who fail to meet the assessment standards of the relevant departments, and economic penalties involve the reduction of financial transfers for poor local environmental protection. According to their conditions, most critical ecological functional areas have implemented various WEDC mechanisms. As a result, there are similarities and differences in the legislative progress or policy, such as the source of compensation obligation, compensation modality, implementation framework, and specific contents (Table 5), such as Qingshui River, Pinghu, and Nansi Lake.

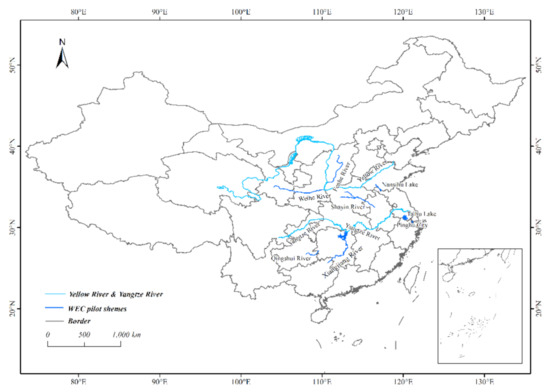

In existing WEC pilot practices (Figure 2), WEC is applied in a WEDC–WEPC mixed mode. On one hand, excessive discharge of upstream pollutants causes damage to or deterioration of the downstream water environment, which is the most intuitive and obvious phenomenon; therefore, the “up to down” and WEDC compensation modes are proposed, and related research results are abundant [50]. On the other hand, some protection facilities to maintain or improve water quality should be built in the upstream area so that the downstream can indirectly enjoy better water quality. Therefore, the downstream beneficiaries should provide reasonable compensation to the upstream, namely a “down to up” and WEPC mode [52,53].

Figure 2.

Geographical distribution of 10 pilot schemes for WEC in China.

In short, the local practice of WEC has the following characteristics: (1) In the current watershed EC, the improvement of watershed legislation or policies is considered an essential means and development goal to improve the water environment quality watershed at this stage. According to the analysis of local practices in China watersheds, it is proposed that no matter whether it is at the national or regional level, there is a lack of legal basis for EC in watersheds. Therefore, strengthening and improving legislation is considered the basis for establishing, developing, and improving the WEC mechanism [54]. (2) In current practice, WEC includes two basic types: WEPC and WEDC. The legislation of WEPC lags behind WEDC. (3) Most inter-provincial WEC practices are in the attempt stage. The compensation mechanism still has an insufficient legal basis and a lack of ecological compensation consultation platform and relevant financial system. Although it emphasizes implementing diversified ecological compensation methods, the implementation structure has not yet been developed [55,56,57]. (4) In the application model of WEC, the effectiveness of WEC has been mainly dependent on the leadership of the government and enterprises. The application of the WEC market-based mechanism is not yet sufficient. Though the report of the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China clearly stated that “The establishment diversified and market-oriented eco-compensation mechanism” is listed as one of the crucial objectives “To accelerate the reform of ecological civilization system and build beautiful China.”, such as “Measures for Eco-Compensation in the Nansi Lake Basin” in Shandong and “Framework Agreement of Environmental Protection” between Shaanxi and Gansu province, which propose exploring the market-based method, there are fewer practices available for reference [58]. It is still necessary to further examine the watershed eco-compensation theory and successful experiences in foreign countries. The main aspects of the payment for watershed ecosystem services’ (PWES) practices will be discussed as follows.

4.2. The Practices of PWES in Foreign Countries

The earliest payment for watershed ecosystem services (PWES) (Table 7) projects were watershed management and planning projects in foreign countries, such as the Tennessee Watershed Management Plan in 1986. More than 180 PWES projects have been carried out in at least 56 countries around the world [59,60]. There are about 40 are developing countries, and about two-thirds of the total number of cases are in developing countries. The number of successful cases is around 46. In addition, the marketization of PWES projects abroad was relatively quicker, had a wide range of products, covered a wide range of areas, and showed a strong link with other water management practices. These characteristics enabled foreign PWES practices to better address basin variability and improve the applicability and efficiency of PWES. Examples of typical overseas PWES cases are shown in Table 4.

Table 7.

Typical cases of Payment for Watershed Ecosystem Services (PWES) in foreign countries.

In brief, the analysis of typical foreign PWES products and projects shows that PWES practices are characterized by the following features: (1) Diversified and market-based compensation models. Most of PWES projects adopted payment for services mechanism in a market transaction model, supplemented by a government compensation model; (2) the sources of funding for PWES projects were diversified, with funds coming mainly from taxes and fees on the use of watershed services, fiscal expenditures, donations, loans, sewage charges, public debt, and trust funds; (3) compensation methods were diversified, mostly in the form of financial compensation (i.e., payments or compensation to watershed service providers and protectors), and to a lesser extent in the form of project-based compensation (i.e., investment of compensation funds or funds in watershed protection projects), complemented by policy compensation and Chilean technical compensation; (4) the abroad PWES funds were managed by private administrators and independent from the government, but the objectives of the fund’s operations were consistent with national planning, and various associations and NGOs played an important role in the implementation of PWES projects; and (5) the local community was widely involved, with various stakeholders participating in the PWES projects, and there was a high level of enthusiasm for the PWES projects.

4.3. Comparative Analysis of Domestic and Foreign Watershed Eco-Compensation

A comparative analysis of typical WEC practices in China and PWES projects abroad shows that there are significant differences. The main differences in the practice can be seen in the following aspects: (1) Different compensation models. The main mode of compensation is market transaction compensation in foreign countries, while the main mode of compensation is the government’s transfer payment in domestic. (2) Different sources of compensation funds. Foreign compensation funds come from a variety of sources, while domestic compensation funds are mainly government expenditures, which is relatively singular. (3) Different compensation approaches. Most domestic compensation is in the form of project compensation, while foreign compensation is mainly financial compensation, supplemented by project compensation, policy compensation, technology compensation, etc. (4) Different compensation criteria and methods of determining compensation standards. (5) The groups in WEC and PWES are different; there are many groups involved in PWES in foreign countries, including upstream and downstream residents, government, enterprises, NGOs, associations, communities, etc., while in China, the groups involved are mainly government and enterprises. (6) The beneficiaries of compensation are different (mainly water protectors in foreign countries, but fewer in China). (7) There is a large difference in the efficiency and effectiveness of compensation, with foreign PWES generally adopting a market-based trading model, which is efficient and effective. In contrast, WEC in China relies too much on the government, which has a heavy burden on the government, resulting in low efficiency and ineffectiveness.

The reasons for the difference are not limited to the late start of WEC practice in China and the lack of experience. Some other factors also constrain the practice of WEC in China, such as an inadequate legal system and inadequate compensation mechanisms.

5. Recommendation for Establishing WEC Mechanism in China

The central government has set targets for environmental quality and pollutants. The national policy proposes establishing a horizontal WEC mechanism for the upstream and downstream in the administrative regions of all provinces (autonomous regions, municipalities) by 2020. By 2025, the pilot scope of the upstream and downstream horizontal eco-compensation mechanism for the upstream and downstream of the watershed across multiple provinces will be further expanded, aiming to promote watershed ecology. They are establishing horizontal ecological protection and compensation mechanisms between upstream and downstream to improve the water environment, the well-being of the people, and the sustainability of socio-economic development in the watershed.

From the perspective of the structure of the WEC, its mechanisms are supposed to be established to perform the following functions: (1) Act as a balance-of-interests mechanism used to coordinate ecological environment protection and economic development, public and private interests. The ultimate goal is to “realize social justice and fairness” and promote sustainable development [58]; (2) furthermore, the beneficiaries or the governments should compensate the providers of ecological services, or the entities responsible for the water pollution should pay the entities damaged by the water pollution and urge the watershed users to undertake the external environmental costs and intensively utilize watershed natural resources [59]; (3) WEC should encourage the investment mechanisms of multiple subjects and stimulate and guide stakeholders to participate in environmental and ecological protection of watersheds [55]; and (4) the behavior restriction mechanism encourages watershed developers or users, and clarifies the substantive or procedural duties of watershed developers, to preserve the environmental rights of residents and ensure the regular supply of watershed services [56].

The integral protection, scientific management, and sustainable development of the watershed ecosystem require establishing a systematic WEC mechanism [61,62,63]. Besides the government’s guiding role, it is also essential to motivate the vitality of NGOs and market-based instruments [64]. The use of government, market, and society’s multi-party cooperative governance will provide a firm and stable social foundation and long-time support for WEC and ultimately achieve harmonious and sustainable development of society, the economy, and the environment [65]. This chapter mainly puts forward strategies for exploring and establishing a long-term operation of WEC mechanisms under China’s existing watershed practices and environmental protection requirements.

5.1. Promoting Diversified Approaches of WEC

5.1.1. Mixed Eco-Compensation Model in WEC

The primary forms of the WEC are as follows: (1) the critical functional areas are compensated by WEC funds from the government in terms of transfer payments and shared and co-construction; (2) the beneficiaries compensate the environmental protector or individual, who pays opportunity costs for development; (3) local governments and enterprises stimulate ecological protection through financial transfer payments and cross-regional horizontal compensation; (4) users or developers of the watershed resource bear the damage compensation for ecological damage, coordination of environmental benefits, and maintenance of social justice. The three modalities should be combined and promoted as mixed methods to construct a diversified compensation mechanism based on the main functions of supporting, coordinating, and motivating WEC.

5.1.2. Multi-Stakeholder Engagement in WEC

WEC is a policy tool to internalize the externalities of watershed ecological services by adjusting the interest relationships between stakeholders [66]. Stakeholders of the WEC mechanism are those who have an impact on the watershed environment or may be affected by the watershed’s utilization, development, and environmental protection. Identifying the significant stakeholders is critical to defining the rights and obligations of the eco-compensation participants. WEPC adheres to the principle of “protector gets” and “beneficiary pays” (BPP). The beneficiaries should compensate the protectors, enterprises, and individuals because of their contribution to protecting the environment. Therefore, the NGOs or other entities play a vital role in those buyers of watershed services rather than the central government [67,68,69].

For WEDC, the main stakeholders are government departments and watershed developers or users. WEDC adheres to the principle of “damager and developer pay”; the damagers should be responsible for the negative impact of their activities on the watershed. In general, the developers of watershed construction programs are responsible for paying compensation fees or compensatory measures. Although the amount and scope of compensation can be negotiated and determined, it still needs to be supervised by related competent authorities. In addition, the multi-stakeholder participation mechanism needs to be continuously improved during the compensation implementation process in current practice.

In general, considering China’s existing watershed management system, the multi-stakeholder of WEC mainly includes governments in pursuit of ecological benefits, market entities in pursuit of economic benefits, and public organizations on the quest for social services. Various environmental NGOs and public organizations can be developed by strengthening the negotiation process through information disclosure and the decision making of the progress and results of compensation approaches [64,67,70]. If proper attention is paid to the disclosure, reporting, and archiving of information, the accountability and transparency of implementing the WEC mechanism will be effectively improved.

5.1.3. Diversified Funding Sources of WEC

The primary target of the WEC institution is to reconcile ecological interests, stimulate social justice, and ensure the maximization of environmental, economic, and social benefits of the watershed. It is an essential mission of WEC to obtain sufficient, sustainable, and stable sources of funds. Undoubtedly, it is necessary to widely mobilize multiple financing channels to realize the purpose of WEC. In general terms, the primary source of funds for WEC is international loans or donations from organizations or environmental NGOs, beneficiary payments, and subsidies or government transfer payments. Diversified WEC aims to absorb other beneficiary market entities and public organizations effectively and, at the same time, fulfill the government’s eco-compensation responsibilities and promote the transformation of diversified compensation, which government public financial compensation transforms to government compensation, market compensation, and social compensation, from purely “blood transfusion” compensation to comprehensive “hematopoietic” payment, which adapts it to the long-term, systematic, and integrated characteristics of ecological protection. It aims to develop a long-term and sustainable mechanism of WEC. Integrating and coordinating the management of various types of special funds for environmental conservation of watersheds, such as river occupation fees and ecological protection taxes, is essential to guarantee the sustainability of compensation funds. The beneficiaries should increase the proportion of their investment in WEPC. Besides central government financial subsidies and financial assistance, it can also incorporate public welfare investments and social donations in the local area. Decentralized funding sources may fail to carry out ecological restoration in time [70]. Therefore, building a WEC fund pool is essential to fully absorbing government transfer payment funds, special ecological compensation funds, remittance funds, and social donation funds. It is conducive to comprehensive management and restoration of large-scale ecosystems across river basins.

5.2. Strengthening Market-Oriented Approaches in WEC

The market-oriented operation mechanism is designed to positively stimulate the market activities of watershed participants [61,62,64,70]. Marked-oriented methodologies mainly include direct payment transactions, third-party intermediary transactions, water rights transactions, trust funds, and PPP water funds in order to explore and apply market-based eco-compensation approaches, give full play to the role of market entities, and solve the problems of ecological environment destruction and unreasonable allocation of the watershed’s environmental resources through ecological resource market transactions [61]. It is different from the governmental financial system, which leans towards the role of essentially guaranteeing guidance and has many shortcomings concerning WEC (for instance, inefficient use of funds, lack of clear goals, and inadequate allocation of special funds). Therefore, it is urgent to implement the market-based mechanism that focuses on voluntary negotiation and paid transactions and to further enhance the effective distribution and economical utilization of eco-compensation through market means. Furthermore, it can relieve the governmental financial investment pressure to a certain extent.

5.2.1. Improving Laws and Regulations on Market-Oriented WEC

China does not have well-established rules and laws regarding the market mechanism, which indicates that the market-based methods must be further strengthened under the legal stipulations of environmental conservation and governance. The Environmental Protection Law explicitly declares that “under the guidance of the state, beneficiaries and environmentally protected areas shall implement eco-compensation through negotiation or by complying with market regulations.” The market rules in the government documents collected above may have already been applied in existing pilot eco-compensation schemes. There is an example of cross-administrative-boundary WEC between Anhui and the Zhejiang [58,68], Henan, and Shandong provinces of China. Clearly defining the rights and responsibilities of environmental or ecological administrative entities in neighboring waters is an essential precondition for effectively carrying out cross-administrative-boundary WEPC.

5.2.2. Establishing a WEC Mechanism for Ecological Products in the Watershed

Theoretically, ecological products and services have value attributes, making market transactions of eco-compensation possible, especially for developing and utilizing water resources in the watershed. The environmental damage and pollution caused by water resource developers and users can fulfill WEC through purchasing services and technologies from other market participants. The relevant qualified third parties provide technologies and services concerning WEC under the contract between the two partners. Eco-compensation for environmental damage and pollution caused by water resource developers and users to the watershed ecosystem can be achieved by purchasing services and technologies from other market participants. Under a contract, the relevant qualified third party provides the technologies and services concerning eco-compensation. However, the market-based transaction of WEC is theoretically feasible. It is difficult to quantify the essential elements of EC because of the absence of price mechanisms for environmental activities and imperfect ecological damage assessment methodologies.

Therefore, market participants’ negotiation relies on proposing a cost-effective ecological compensation method [69,70]. The adoption of market-oriented methodologies must be enhanced according to the following aspects: first, it is necessary to develop new industries of green agriculture, green industry, and green service industry and improve ecological damage evaluation technology; second, it is necessary to clearly define the legal obligations of the government, enterprises, are individuals for the environmental management and protection of the watershed, establish the water rights trading system, and implement water rights transactions; third, the upstream and downstream governments in the watershed are the organizers to try to establish enclave economic parks and innovate the ecological environmental protection market management model to promote transactional eco-compensation; fourth, the government must build a standardized supervision system and create a favorable market atmosphere, explore green financial models such as water funds, and formulate regulations for the development and administration of watershed resources, the conservation and construction of watershed ecological environments, and watershed investment and compensation to guarantee the smooth establishment of the WEC mechanism.

6. Conclusions and Future Prospects of WEC in China

WEC has been extensively accepted as an essential governance instrument to improve environmental conservation and sustainable utilization of river resources. Meanwhile, it is urgent to construct the WEC system in China. According to the current environmental policy, legislation, social environment, and legislative and social circumstances, the available pilot programs and the accumulated practices have provided valuable referrals for patterns, strategies, and methodologies to establish a complete WEC system. Constructing a diversified and market-oriented WEC mechanism will help solve many problems in the current WEC, especially the lack of compensation funds and single compensation methods. Besides, this mechanism design complies with the future development trend of eco-compensation and the goal of “building a market-based diversified ecological compensation mechanism” proposed by President Xi Jinping. It is in line with the national strategic plan for developing comprehensive protection and restoration of watershed ecosystems. We should encourage various environmental NGOs and public organizations to participate in WEC, broaden the sources of compensation funds, and build a diversified and market-based WEC mechanism to deal with problems (such as low stakeholder participation, lack of compensation funds, and insufficiency of compensation modality) in implementing WEC.

The rapid development and practice of the WEC system should be improved from the following aspects: (1) Improving eco-compensation legislation is crucial to constructing a WEC system. The key is to formulate specific laws and regulations following the available practice experiences in watersheds, supplemented by the related technical criteria and guidance, as a scientific basis to offer a legislative base for regional legislation and practices. Simultaneously, regional governments should adopt concrete management approaches and criteria based on their natural conditions and levels of utilization and development; (2) Establishing a diversified WEC mechanism needs technological support, including active surveillance and monitoring as well as integrated status evaluation and assessment. It can provide scientific bases and capability guarantees for achieving WEC; (3) The validity of market-oriented compensatory methods is grounded in clear ownership of watershed resources and a favorable policy context. Developing a market-oriented approach to WEC can be modeled after mechanisms such as water rights transactions and carbon emission trading; (4) Government and administrative departments will continue to take a predominant role in driving the efficient operation of WEC projects. Hence, it is vital to incorporate the effectiveness of water ecosystem management into the performance assessment and the objective responsibility regime of watershed eco-environmental conservation. In consequence, the political willingness and motivation for WEC will be strengthened.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.C.; methodology, X.C.; software, J.L.; formal analysis, L.M. and H.W.; data curation, X.C.; writing—original draft preparation, X.C. and L.M.; writing—review and editing, X.C. and L.F.; supervision, L.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Bösch, M.; Elsasser, P.; Wunder, S. Why do payments for watershed services emerge? A cross-country analysis of adoption contexts. World Dev. 2019, 119, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Brouwer, R. Is China affected by the resource curse? A critical review of the Chinese literature. J. Policy Model. 2020, 42, 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthington, A.H.; Bunn, S.E.; Poff, N.L.; Naiman, R.J. The challenge of providing environmental flow rules to sustain river ecosystems. Ecol. Appl. 2006, 16, 1311–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.C.; Zhang, H.N.; Ge, Y.X.; Jie, Y.M. Analysis Framework of Diversified Watershed Eco-compensation: A Perspective of Compensation Subject. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2019, 29, 131–139. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.A.; Xu, X.M. Research status and prospect of marine ecological compensation. Econ. Res. Guide 2016, 22, 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Bergh, J. Externality or sustainability economics? Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 2047–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benchekroun, H.; Chaudhuri, A.R. Transboundary pollution and clean technologies. Resour. Energ. Econ. 2014, 36, 601–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kosoy, N.; Martinez-Tuna, M.; Muradian, R.; Martinez-Alier, J. Payments for environmental services in watersheds: Insights from a comparative study of three cases in Central America. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 61, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Y.; Liu, G.H.; Wang, J.N. Policy and Practice Progress of Watershed Eco-compensation in China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2007, 17, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Dong, Z.; Xu, Y.; Ge, C. Eco-compensation for watershed services in China. Water. Int. 2016, 41, 271–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R.; d’Arge, R.; De Groot, R.; Farber, S.; Grasso, M.B.; Hannon, B.; Raskin, R.G. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 1997, 387, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R.; Groot, R.; De Braat, L.; Kubiszewski, I.; Fioramonti, L.; Sutton, P.; Grasso, M. Twenty years of ecosystem services: How far have we come and how far do we still need to go? Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 28, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Untied Nations. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2015 Revision; Untied Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC). Development and Planning Outline of the Yangtze River Economic Belt Officially Released; NDRC: Beijing, China, 2016. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yan, D.D.; Fu, Y.C.; Liu, B. Theoretical Study of Watershed Eco-Compensation Standards. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 301, 012100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Liu, M.; Guan, X.; Liu, W. Comprehensive evaluation of ecological compensation effect in the Xiaohong River Basin. China Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 7793–7803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, B.; Carroll, N.; Moore Brands, K. State of Biodiversity Markets: Offset and Compensation Programs Worldwide; Ecosystem Marketplace: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton, T.; Echavarria, M.; Hamilton, K.; Ott, C. State of Watershed Payments: An Emerging Marketplace. J. Sustain. For. 2010, 28, 497–524. [Google Scholar]

- OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development). Scaling-Up Finance Mechanisms for Biodiversity; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, S.; Pagiola, S.; Wunder, S. Designing payments for environmental services in theory and practice: An overview of the issues. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 65, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, U.; Phelps, J.; Garmendia, E.; Brown, K.; Corbera, E.; Martin, A.; GomezBaggethun, E.; Muradian, R. Social equity matters in payments for ecosystem services. Bioscience 2014, 64, 1027–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development). Biodiversity Offsets: Effective Design and Implementation—Policy Highlights; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, W.X.; Gong, Y.C.; Wang, Z.J.; Michael, J. Eco-compensation in China: Theory, practices and suggestions for the future. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 210, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.H.; Lant, C.L. The effect of wetland mitigation banking on the achievement of no-net-loss. Environ. Manag. 1999, 23, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, J.; Hobbs, R.J.; Valentin, L.E. Are offsets effective? An evaluation of recent environmental offsets in Western Australia. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 206, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wunder, S. The efficiency of payments for environmental services in tropical conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2007, 21, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SEPA. The Guidance on Implementation of Eco-Compensation Pilot; State Environmental Protection Administration: Beijing, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman-Benner, R.L.; Benitez, S.; Boucher, T.; Calvache, A.; Daily, G.; Kareiva, P.; Kroeger, T.; Ramos, A. Water funds and payments for ecosystem services: Practice learns from theory and theory can learn from practice. Oryx 2012, 46, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Suhardiman, D.; Wichelns, D.; Lestrelin, G.; Hoanh, C.T. Payments for ecosystem services in Vietnam: Market-based incentives or state control of resources? Ecosyst. Serv. 2013, 6, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, L.; Zhang, H. Payment for ecosystem services in China: An overview. Living Rev. Landsc. Res. 2011, 5, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marlene, N.; Gray, S.; Sharma, A.; Burn, S.; Muttil, N. Impact of water management practice scenarios on wastewater flow and contaminant concentration. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 151, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noerfitriyani, E.; Hartono, D.M.; Moersidik, S.S.; Gusniani, I. Impact of leachate discharge from Cipayung landfill on water quality of Pesanggrahan River, Indonesia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 120, 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jiang, Y.H.; Zhang, J.W.; Chen, K.L.; Xue, X.Z.; Michael, A.U. Moving towards a Systematic Marine Eco-Compensation Mechanism in China: Policy, Practice and Strategy. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2019, 169, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockie, S. Market Instruments, Ecosystem Services, and Property Rights: Assumptions and Conditions for Sustained Social and Ecological Benefits. Land Use Policy 2013, 31, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X. Water stress, water transfer and social equity in Northern China-Implications for policy reforms. J. Environ. Manag. 2008, 87, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.M.; Wang, J.N.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.L. Pollution control costs of a transboundary river basin Empirical tests of the fairness and stability of cost allocation mechanisms using game theory. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 177, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, B.; Sun, M. A differential oligopoly game for optimal production planning and water savings. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 269, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fünfgelt, J.; Schulze, G. Endogenous environmental policy for small open economies with transboundary pollution. Econ. Model. 2016, 57, 294–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standing Committee of the 12th National People’s Congress. Environmental Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China; Standing Committee of the 12th National People’s Congress: Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, M.T.; Zhang, Q.; Kannan, K.; Jin, L. Payments for Ecological Services and Eco-Compensation: Practices and Innovations in the People’s Republic of China; Asian Development Bank: Mandaluyong City, Philippines, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Palerm, J. The Habitats Directive as an instrument to achieve sustainability? An analysis through the case of the Rotterdam mainport development project. Eur. Environ. 2006, 16, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaissière, A.C.; Levrel, H.; Pioch, S.; Carlier, A. Biodiversity offsets for offshore wind farm projects: The current situation in Europe. Mar. Pol. 2014, 48, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Villarroya, A.; Puig, J. Ecological compensation and environmental impact assessment in Spain. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2010, 30, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.J.; Liu, M.; Meng, Y. A comprehensive ecological compensation indicator based on pollution damage -protection bidirectional model for river basin. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 126, 107708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. Practice and progress of the basin water environmental eco-compensation in watershed. Environ. Monit. China 2014, 30, 191–195. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Geng, X.Y.; Ge, Y.X.; Zhang, H.N. Study on Ecological Compensation Standard of Watershed Based on Reset Cost: A Case Study of Xiaoqing River Basin. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2018, 28, 140–147. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xi, J.P. Speech at the Symposium on Ecological Protection and Quality Development in the Yellow River Basin. Water Resour. Dev. Manag. 2019, 11, 1–4. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xi, Y.Q.; Wang, J.Q. Research on Ecological Compensation Mechanism of Watersheds in China from the Perspective of Marketization and Diversification. J. UESTC 2020, 22, 54–60. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, B.; Tian, R.; Dong, Z. Patterns and assessment of the watershed eco-compensation standard practices in China. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 4, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, T.; Rhodes, C.; Shah, F.A. Upstream water resource management to address downstream pollution concerns: A policy framework with application to the Nakdong river basin in South Korea. Water Resour. Res. 2015, 51, 787–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Xu, J.; Qin, F.; Wang, J.Y. Payments for Watershed Services and Practices in China: Achievements and Challenges. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2018, 28, 873–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wunder, S. Revisiting the concept of payments for environmental services. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 117, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.J. Evaluation on the pollution control of Qingshui River Basin in Guizhou Province. Environ. Prot. Technol. 2014, 20, 33–35. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, M.T.; Trends, F. Markets for Ecosystem Services in China: An Exploration of China’s “Eco-Compensation” and Other Market-Based Environmental Policies; Forest Trends: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, X.J.; Hou, S.; Meng, Y.; Liu, W. Study on the quantification of ecological compensation in a river basin considering different industries based on water pollution loss value. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 30954–30966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.C.; Wang, J. Developing Eco-Compensation Regulations in China: The Way Forward; Peking University Press: Beijing, China, 2013; pp. 301–308. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Jia, R.X. The implementation development of horizontal pilot eco-compensation policy in Xin’an River watershed in Anhui Province. China Econ. Trade Her. 2015, 13, 58–62. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.H. On the Mechanism of Ecological Compensation from the Perspective of Shared Development: A Case Study of Xin’an River Basin. Stud. Mao Zedong Deng Xiaoping Theor. 2017, 5, 51–56. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.J. Watershed Eco-Compensation Mechanism and Policy Study in China. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2010, 2, 1290–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Q.; Bennett, M.T. Eco-Compensation for Watershed Services in the People’s Republic of China; Asian Development Bank: Manila, Philippines, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wunder, S. Payments for Environmental Services: Some Nuts and Bolts; Center for International Forestry Research: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2005; Volume 42, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado-Quesada, I.; Hein, L.; Weikard, H. Market-based mechanisms for biodiversity conservation: A review of existing schemes and an outline for a global mechanism. Biodivers. Conserv. 2014, 23, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.Z.; Zhang, L. Revising China’s environmental law. Science 2013, 341, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Sun, F.Y.; Fu, B.T.; Deng, L.Z.; Yang, K.; Liu, Y.Y.; Che, Y. How to promote the public participation in eco-compensation in transboundary river basins: A case from Planned Behavior perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 313, 127911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Zhang, X.X.; Wang, Y.S. Stability and influencing factors when designing incentive-compatible payments for watershed services: Insights from the Xin’an River Basin, China. Mar. Policy 2021, 134, 104824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teets, J.C.; Gao, M.; Wysocki, M.; Ye, W.R. The impact of environmental federalism: An analysis of watershed eco-compensation policy design in China. Environ. Policy Gov. 2021, 31, 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.J.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Z.X. Quantification of eco-compensations based on a bidirectional compensation scheme in a water environment: A case study in the Jiangsu Province, China. Water Policy 2019, 21, 1162–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, J.C.; Qiu, W.G.; Han, X. China’s PES-like horizontal eco-compensation program: Combining market-oriented mechanisms and government interventions. Ecosyst. Serv. 2020, 45, 101164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.H.; Zheng, Q.; Fu, L.L. Multilevel Governments’ Decision-Making Process and Its Influencing Factors in Watershed Ecological Compensation. J. Coast. Res. 2019, 11, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Meijerink, S.; van der Krabben, E. Institutional Design and Performance of Markets for Watershed Ecosystem Services: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).