Abstract

Coronaviruses are pathogens recognized for having an animal origin, commonly associated with terrestrial environments. However, in a few cases, there are reports of their presence in aquatic organisms like fish, frogs, waterfowl, and marine mammals. None of these cases has led to human health effects when contact with these infected organisms has taken place, whether they were alive or dead. Aquatic birds seem to be the main group carrying and circulating these types of viruses among healthy bird populations. Although the route of infection for COVID-19 by water or aquatic organisms has not yet been observed in the wild, the relevance of its study is highlighted because there are cases of other viral infections known to have been transferred to humans by aquatic biota. It is encouraging to know that aquatic species, such as fish, marine mammals, and amphibians, show very few coronavirus cases. Some other aquatic animals may also be a possible source of cure or treatment against, as some evidence with algae and aquatic invertebrates suggest.

1. Introduction

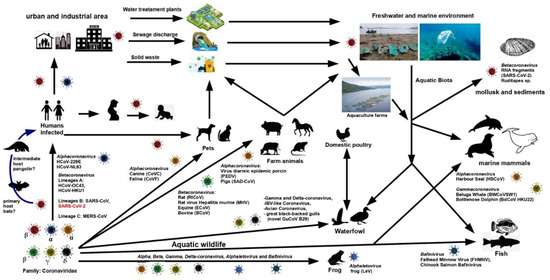

The current Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) or COVID-19 pandemic, as it is commonly known, brought society’s interest in one of the families of high-risk pathological-infectious viruses, known as Coronavirus (CoVs) [1]. The impact that COVID-19 has had on human dynamics is undoubtedly enormous. The mortality and public health impacts caused by COVID-19 caught the attention of scientists to try to slow down its effects and look for a vaccine. This virus is already present in every continent, and as with previous events with other viruses such as SARS or HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus), humans will have to learn how to live with it. However, this situation also makes us wonder about what other organisms may be subject to coronavirus infection. Which organisms can be vectors or reservoirs? They may have the virus in their body, transport it, and spread it in other areas or to other organisms without suffering the symptoms of the infection [2].

Moreover, can the coronavirus infect and affect aquatic organisms? Indeed, these questions in the scientific and non-scientific communities may eventually be answered in a particular way over time for SARS-CoV-2. However, at the moment, scientific efforts are focused on the public health aspects at the global level [3,4]. Thanks to previous studies on the subject, we can access information to understand more about the possible scenarios associated with these questions. In addition, it allows us to be able to make more specific approaches to the impact of SARS-CoV-2 on aquatic organisms, based on the general knowledge that is available on coronaviruses. Due to the above, this review aims to synthesize the information available in the scientific literature on the detection and presence of coronavirus in organisms and promote its study, not only for the ecological and public health impacts, but also its potential as treatment sources. This work has focused on the coronavirus’ basic features, presence in aquatic environments, detection in aquatic organisms (fish, marine mammals, waterfowls, amphibians, crustaceans, and mollusks), some viral infections on humans from aquatic organisms, and further considerations involving biological aspects or potential use of biomolecules produced by aquatic biota, in search of a treatment or control against coronavirus exposures. This review highlights the proven CoVs cases, discussing if their features could indicate future CoVs infections, taking into account previous infections from similar viruses, as well as the possible implications in its dispersion. It also mentions the potential that aquatic organisms can represent in searching for control or treatment against these highly pathogenic viruses. The importance of carrying out broad and specific studies on coronavirus presence, abundance, pathologies, dispersion, and affectations in aquatic biota is discussed.

This review was achieved by mainly identifying formal research articles published and available in different scientific databases such as Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, Google Academic, ResearchGate, and ScienceDirect. The studies included in this review were based on the following selection criteria: studies reporting the presence of coronavirus in aquatic organisms, including amphibians and birds. Those published in peer-reviewed journals were considered preferably due to the limitation of works. Search-engines included “coronavirus”, “SARS”, “CoV”, “fish”, “crustacea”, “marine mammals”, “birds”, “waterfowl”, “amphibian”, “treatment”, “source”, “substance”, “infection”, “disease “, ”host”, “health”, “mollusk “,” invertebrates “,” marine”, “freshwater “, “aquatic “,” biota “,” organism “, and their combinations. General information was collected for every eligible study, including author(s), year published, coronavirus type, order, family, gender, species, and host. The adverse or health effect was also recorded when possible, specifically whether this concerned coronavirus or a related virus.

3. Some Viral Infections to Humans from Aquatic Organisms

No published studies on the actual risk of SARS-CoV-2 contagion from aquatic organisms were found during this review. Neither have Betacoronavirus (genus to which SARS-CoV-2 belongs) been found in marine organisms; instead, it has been seen those other genera such as Gammacoronavirus (which were discussed in Section 2.2.4) and Alphacoronavirus prevail, which share little homology with the SARS-CoV-2 virus. However, according to Mordecai and Hewson, these two genera are associated with respiratory diseases in pinnipeds and cetaceans [90].

There is a history of other viral respiratory infections transmitted to humans from wild or captive animals [19,48]. That is the case with influenza-A, caused by the H7N7 virus, in people infected during a necropsy performed to a seal [59] or by coming into contact with the sneeze of a seal in captivity [48], causing conjunctivitis, rather than typical influenza or respiratory disease. A similar case has also been identified for Influenza B [6,48]. Moreover, a historical review carried out by Petrovic et al. [19] has shown numerous viral outbreaks (not CoVs related) associated with shellfish. These outbreaks included human enteric viruses, mainly those of type NoV (norovirus). HAV (hepatitis virus A), EV (Enterovirus), HAdV (human adenovirus), and HRV (human rotavirus) are reported in shellfish in different countries, but not CoVs. Oysters and clams have been associated with NoV and HAV between 1976 and 1999 in the United States alone. These viruses have also been identified in mollusks in Europe, both in fish and sea markets and oyster farms associated with human enteric viruses between 1990 and 2006 [91,92]. All are good examples of the food source of viral infections. For the World Health Organization and the Food and Agriculture Organization Joint Committee, coronaviruses related to Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS-CoV) are viruses of concern by contaminated food [93]. Other types of water viruses associated with birds, such as H5N1 avian influenza and avian influenza A1, are highly infectious and recognized for their transmission to humans from duck meat and blood [94,95]. Due to these examples, extensive monitoring studies are required since ducks are one of the main groups of birds capable of carrying CoVs (Table 2).

At the moment, as long as there are no more significant scientific elements to be certain of the non-spread of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic through natural waters and aquatic organisms, it is best to follow the indications that the health authorities have been issuing in this regard. These indications highlight those made by the World Health Organization [96], which recommends avoiding unprotected contact with wild and farm animals, and has even been recommended not to approach public markets where wild animals are under sale, both live and slaughtered [9].

4. Further Considerations about CoVs and Aquatic Biota

The efforts of the scientific community will continue over the coming years to learn more about COVID-19. Studying genetic adaptation, including mutation and recombination, identifying routes of zoonotic (animal) origin, new vector organisms (birds, mammals, fish, amphibians, mollusks or crustaceans), animal-human transmission events, wild natural storage, and contagion risks, will allow effective and realistic programs to control the transmission of coronaviruses, particularly SARS-CoV-2. It is recognized that viral genotypes with epidemiological potential can become exceedingly variable due to their genetic characteristics, which allow them to endure and survive and spread and even mutate along trophic chains [79].

As some studies suggest, the relationship between coronaviruses and aquatic biota is not limited to a pathogen–host relationship but also a pathogen–treatment relationship.

There is a universe of biologically active substances of marine origin, such as flavonoids, phlorotannins, alkaloids, terpenoids, peptides, lectins, polysaccharides, lipids, and other substances that can affect coronaviruses (Table 4). The penetration and entry stages of the viral particle into the host cell in viral nucleic acid replication and virion release from the cell can also act on the host’s cellular targets. These natural compounds could be a vital resource in the fight against coronaviruses [97]. Zaporozhets and Bedsenova [97] conducted a database search in 2020, identifying ~34 biologically active substances from sponges, echinoderms, mollusks, soft corals, bryozoans, and others.

Table 4.

Bioactive substances of marine origin have an antiviral activity to CoV and other viruses.

It is encouraging to know that even other aquatic organisms, such as seaweed or sponges, could play a key role in treating CoVs infections. It has been observed through laboratory tests with Halimeda tuna algae, a natural product known as diterpene aldehyde or halitunal [98], an antiCoV effect. Other examples are the sponge Mycale sp., which produces a substance called micalamide A, both with antiviral capacity against the A59-CoV of murine origin [99,100].

Another good example is the Axinella corrugata sponge that produces an ethyl ester of esculetin-4-carboxylic acid against SARS-CoV [103]. Natural marine compounds are being found to be inhibitors against the main protease of SARS-CoV-2 [109]. Eight antiviral compounds have been recently reported against SARs-CoV-2 protease, particularly a compound identified as Esculetin ethyl ester from A. corrugata, which has shown to be the most effective antiprotease [110]. These molecules are considered bioactive compounds that act as replication inhibitors to SARS-CoV in Vero cells (kidney cells from an African green monkey [103], among others that can act as effective antiviral drugs [110]. Other SARS-CoV-2 protease inhibitor compounds are pseudotheonamides, which have been isolated from the marine sponge Theonella swinhoei and have shown good inhibitory activity on serine protease [97]. Together with other products of natural origin [98,103], these substances could be the source of some control against coronavirus like SARS-CoV-2 in the future.

One species that has shown significant therapeutic potential against SARS-CoV-2 are sea urchins. The consumption of these organisms dates back to ancient times in Chinese medicine. Gonads, spines and shell powders are known for their beneficial effects on the heart, bones, blood, and impotence [111]. In the 1980s, Echinochroma A (polyhydroxy naphthoquinone molecule) from gonads, spines and shells showed cardioprotective action and healing properties for some eye diseases [111]. Recently, the antioxidant and antiviral activity of Echinochroma A against RNA viruses such as TVEB (tick-borne encephalitis virus) and DNA virus, HSV-1 (herpes simplex virus type 1) are being investigated with good results to develop drugs [107]. The antiviral effects of Echinochroma A that of its amino homologues, Echinamines A and B on the HSV-1 virus, have shown that they exert a response that inhibits the production of reactive oxygen species generated by HSV -1; in addition, these molecules reduce the adhesion of the virus to the host cell [106]. Recently Barbieri et al. [112] have evaluated the therapeutic potential of sea urchin pigments (Echinochroma A, Spinochromos A and B) on SARS-CoV-2, observing that it acts by blocking and inhibiting the protein S of the virus, which prevents it from entering the host cell. Rubilar et al. [113] evaluated the potential of the pigments (Spinochromo A, Echinochroma A, beta-carotene, Astaxanthin and Fucoxanthin). They found an inhibitory capacity and high affinity to the SARS-CoV-2 protease (which plays an active role in its replication process) from the Echinochroma A pigment. This result suggests that sea urchin pigments may be candidates for being antiviral drugs against the SARS-CoV-2. A disadvantage is that sea urchin pigments are found in low concentrations; however, there is high concentration of this pigment in eggs of the sea urchin Arbacia dufresnii [113].

Marine macroalgae, for example, those of the genus Sargassum sp. constitute a promising source of compounds with antiviral activity, motivating the search for new drugs against viruses [114]. Gentile et al. [104] carried out a promising and cutting-edge study where different compounds of natural origin with inhibitory activity for the SARS-CoV-2 protease have been selected, modelled, molecularly simulated, and evaluated from the data of a library of 3D chemical structures of natural marine products. According to the authors, the most promising SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors are mainly related to phlorotannins, oligomers of phloroglucinol (1,3,5-trihydroxy benzene), isolated from Sargassum spinuligerum. Phlorethols, fuhalols, and fucophlorethols are among phlorotannins found in other species of Sargassum [104]. It was also observed that the most active inhibitor compounds against SARS-CoV-2 are those belonging to the family of phlorotannins, isolated in the brown alga Ecklonia cava, which is an edible alga recognized as a rich source of bioactive derivatives [98].

Ponce Rey et al. [114] evaluated the in vitro antiviral activity of a hydroalcoholic extract of the brown seaweed Sargassum fluitans against Echovirus 9 (E9). This type of enterovirus causes severe systemic diseases such as aseptic meningitis and, to a lesser extent, infant mortality. There is no antiviral treatment or vaccination against this virus. As in most enteroviruses, the phytochemical screening showed quinones, proanthocyanidins, catechins, polar triterpenes, hydrolysable tannins, and proteins as main constituents. The extract was not cytotoxic at the concentrations evaluated, and it potently inhibited the replication of E9 in the cell line used with a high SI (selective index) of 95.05. Also, during the antiviral test, the hydroalcoholic extract of S. fluitans inhibits E9 multiplication in a dose-dependent manner [114].

Abdelrheem et al. [105] evaluated the inhibitory effect of the SARS-CoV-2 virus protease by different natural bioactive compounds with recognized biological activity as anticancer, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antiviral, among others. Some examples are hexadecanoic acid, oleic acid, saryngosterols, beta-sitosterol, glycoglycerolipids, Kjellmanianone, the terpene loliolide and the alkaloid caulerpin. These bioactive compounds are found in green, red, and brown macroalgae of marine origin (Sargassum platycarpum S. naozhouense, S. horneri, S. glaucescens, S. muticum, Ceramium virgatum, Fucus sp., Cladophora fascicularis, Acanthophora spicifera, Ulva fasciata, U. intestinalis, Eucheuma cottonii, Exophyllum wentii, Chondria armata, Caulerpa racemosa), including freshwater microalgae (Chlorella vulgaris, Nannochloropsis). The most outstanding results of the study allow us to conclude that caulerpin is very effective against SARS-CoV-2 by inhibiting the main protease and can be further explored for drugs against the COVID-19 pandemic [105].

Some issues faced by those developing new drugs to inhibit the SARS-CoV-2 and other viruses from natural products is that sources are not readily available or cannot be developed on a large scale. In this regard, it is worth mentioning that some coastal areas of the Caribbean Sea, as well as the coasts of Mexican state of Quintana Roo, from 2011 up to date, are facing massive Sargassum fluitans and S. natans arrivals. Other countries that have reported massive waves of Sargassum are Belize, Honduras, Jamaica, Cuba and Barbados [115]. This type of macroalgae proliferates, doubling its mass in less than 18 days. These algae eventually decompose and generate unpleasant odors and cause problems in coastal areas and beaches. It seems that Sargassum can interfere massively in the transmission of light down the water column, mainly affecting seagrasses. When Sargassum dies and decomposes, it consumes large amounts of oxygen, causing anoxia, affecting other species [115]. Therefore, it would be interesting to evaluate whether the Sargassum that reaches the shores can serve as a potential source of bioactive compounds (antivirals, antioxidants, among others) that can be used to combat SARS-CoV-2 or other viruses.

5. Conclusions

CoVs in aquatic environments are rare but also a reality, which has demonstrated its ability to be transmitted to organisms in wildlife, aquaculture farms, and animals under captivity. Its presence observed in farmed fish such as carp, or a frog, although they have not reported significant effects or consequences on human health, could be of potential risk in the near future for aquatic ecosystems. Knowledge of other cases such as marine mammals have shown to be carriers of respiratory infections, must be considered for other viruses like CoVs, particularly SARS-CoV-2. Waterfowl show to be a natural CoVs reservoir, mainly ducks, which deserve to be studied in more detail due to their migratory behaviors. This monitoring should be carried out jointly with new studies and biotechnological strategies to continue searching for alternative bioactive compounds of aquatic origin that can be used against the COVID-19 pandemic, among other diseases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.N.-N. and design G.N.-N., J.A.V.-Á., A.T.-G.; Methodology, G.N.-N., J.A.V.-Á.; Figure, J.A.V.-Á.; Formal Analysis and Investigation, J.A.V.-Á., A.T.-G., A.A.G.-B., E.R.-A., F.A.Z.-G. and G.N.-N.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, G.N.-N., J.A.V.-Á.; Writing—Review & Editing, G.N.-N., J.A.V.-Á., A.A.G.-B.; Funding, A.T.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work received no external funding, and Manzanillo University of Technology, Colima, Mexico funded the APC.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The author G.N.-N. recognizes the support provided by the PII SNI-UJAT program, comment, ideas and suggestions made by all reviewers and the assistance of Enrique Núñez-Jiménez and Elia Cornelio to improve this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Burki, T. Outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 292–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costagliola, A.; Liguori, G.; D’angelo, D.; Costa, C.; Ciani, F.; Giordano, A. Do animals play a role in the transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2)? a commentary. Animals 2021, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M.; Vaishya, R.; Deshmukh, S.G. Areas of academic research with the impact of COVID-19. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 38, 1524–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, G.; Li, X.; Hu, L.; Jiang, G. An Imperative Need for Research on the Role of Environmental Factors in Transmission of Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 3730–3732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, A.; Pintó, R.M.; Le Guyader, F.S. Viral contaminants of molluscan shellfish: Detection and characterisation. In Shellfish Safety and Quality; Shumway, S.E., Rodrick, G.E., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2009; pp. 83–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouseettine, R.; Hassou, N.; Bessi, H.; Ennaji, M.M. Waterborne Transmission of Enteric Viruses and Their Impact on Public Health; Elsevier Inc.: London, UK, 2019; ISBN 9780128194003. [Google Scholar]

- de Groot, R.; Baker, S.; Baric, R.; Enjuanes, L.; Gorbalenya, A.; Holmes, K.; Perlman, S.; Poon, L.; Rottier, P.; Talbot, P.; et al. Part II—The Positive Sense Single Stranded RNA Viruses Family Coronaviridae. In Virus Taxonomy: Ninth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses; King, A.M.Q., Adams, M.J., Carstens, E.B., Leftkowitz, E.J., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2012; pp. 806–828. ISBN 9780123846846. [Google Scholar]

- Avendaño-López, C. Aportaciones de las ciencias biomédicas en el estado de alarma motivado por la pandemia del virus COV-2. An. la Real Académia Nac. Farm. 2020, 86, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, Y.S.; Sircar, S.; Bhat, S.; Sharun, K.; Dhama, K.; Dadar, M.; Tiwari, R.; Chaicumpa, W. Emerging novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)—current scenario, evolutionary perspective based on genome analysis and recent developments. Vet. Q. 2020, 40, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, P.C.Y.; Lau, S.K.P.; Lam, C.S.F.; Tsang, A.K.L.; Hui, S.-W.; Fan, R.Y.Y.; Martelli, P.; Yuen, K.-Y. Discovery of a Novel Bottlenose Dolphin Coronavirus Reveals a Distinct Species of Marine Mammal Coronavirus in Gammacoronavirus. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 1318–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasmi, Y.; Khataby, K.; Souiri, A.; Ennaji, M.M. Coronaviridae: 100,000 years of emergence and reemergence. In Emerging and Reemerging Viral Pathogens: Volume 1: Fundamental and Basic Virology Aspects of Human, Animal and Plant Pathogens; Ennaji, M.M., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2019; pp. 127–149. ISBN 9780128194003. [Google Scholar]

- Bukhari, K.; Mulley, G.; Gulyaeva, A.A.; Zhao, L.; Shu, G.; Jiang, J.; Neuman, B.W. Description and initial characterization of metatranscriptomic nidovirus-like genomes from the proposed new family Abyssoviridae, and from a sister group to the Coronavirinae, the proposed genus Alphaletovirus. Virology 2018, 524, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granzow, H.; Weiland, F.; Fichtner, D.; Schütze, H.; Karger, A.; Mundt, E.; Dresenkamp, B.; Martin, P.; Mettenleiter, T.C. Identification and ultrastructural characterization of a novel virus from fish. J. Gen. Virol. 2001, 82, 2849–2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leong, J.C. Fish Viruses. In Encyclopedia of Virology; Mahy, B.W.J., Van Regenmortel, M.H.V., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2008; pp. 227–234. ISBN 9780123744104. [Google Scholar]

- Alexyuk, M.S.; Turmagambetova, A.S.; Alexyuk, P.G.; Bogoyavlenskiy, A.P.; Berezin, V.E. Comparative study of viromes from freshwater samples of the Ile-Balkhash region of Kazakhstan captured through metagenomic analysis. VirusDisease 2017, 28, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar-Oliveira, M.d.L.; Campos, A.; Matos, A.R.; Rigotto, C.; Sotero-Martins, A.; Teixeira, P.F.P.; Siqueira, M.M. Wastewater-based epidemiology (Wbe) and viral detection in polluted surface water: A valuable tool for covid-19 surveillance—A brief review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roa, V.C.; Melnick, J.L. Environmental Virology; Van Nostrand Reinhold Co. Ltd.: Berkshire, UK, 1986; ISBN 9788578110796. [Google Scholar]

- Melnick, J.L. Etiologic Agents and Their Potential for Causing Waterborne Virus Diseases. Monogr. Virol. 1984, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Petrović, T.; D’Agostino, M. Viral Contamination of Food. In Antimicrobial Food Packaging; Barros-Velázquez, J., Ed.; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 65–79. ISBN 9780128007235. [Google Scholar]

- Farthing, M.J.G. Viruses and the Gut; Farthing, M.J.G., Ed.; Smith Kline & French Ltd.: Walwyn Garden City, Hertfordshire, UK, 1989; ISBN 0948271086. [Google Scholar]

- Lesté-Lasserre, C. Coronavirus found in Paris sewage points to early warning system. Sci. News. 2020, 1. Available online: https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/04/coronavirus-found-paris-sewage-points-early-warning-system (accessed on 8 May 2020). [CrossRef]

- Macnaughton, M.R. Occurrence and frequency of coronavirus infections in humans as determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Infect. Immun. 1982, 38, 419–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feichtmayer, J.; Deng, L.; Griebler, C. Antagonistic microbial interactions: Contributions and potential applications for controlling pathogens in the aquatic systems. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.W.; Li, J.S.; Guo, T.K.; Zhen, B.; Kong, Q.X.; Yi, B.; Li, Z.; Song, N.; Jin, M.; Xiao, W.J.; et al. Concentration and detection of SARS coronavirus in sewage from Xiao Tang Shan Hospital and the 309th Hospital. J. Virol. Methods 2005, 128, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, L.; Rutala, W.A.; Weber, D.J.; Sobsey, M.D. Survival of surrogate coronaviruses in water. Water Res. 2009, 43, 1893–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.W.; Li, J.S.; Jin, M.; Zhen, B.; Kong, Q.X.; Song, N.; Xiao, W.J.; Yin, J.; Wei, W.; Wang, G.J.; et al. Study on the resistance of severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus. J. Virol. Methods 2005, 126, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prussin, A.J.; Schwake, D.O.; Lin, K.; Gallagher, D.L.; Buttling, L.; Marr, L.C. Survival of the enveloped virus Phi6 in droplets as a function of relative humidity, absolute humidity, and temperature. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasija, M.; Li, L.; Rahman, N.; Ausar, S.F. Forced degradation studies: An essential tool for the formulation development of vaccines. Vaccine Dev. Ther. 2013, 3, 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sharma, S.; Gray, D.K.; Read, J.S.; O’Reilly, C.M.; Schneider, P.; Qudrat, A.; Gries, C.; Stefanoff, S.; Hampton, S.E.; Hook, S.; et al. A global database of lake surface temperatures collected by in situ and satellite methods from 1985–2009. Sci. Data 2015, 2, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padisák, J.; Reynolds, C.S. Shallow lakes: The absolute, the relative, the functional and the pragmatic. Hydrobiologia 2003, 506–509, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heldal, M.; Bratbak, G. Production and decay of viruses in aquatic environments. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1991, 72, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wommack, K.E.; Hill, R.T.; Muller, T.A.; Colwell, R.R. Effects of sunlight on bacteriophage viability and structure. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1996, 62, 1336–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilhelm, S.W.; Weinbauer, M.G.; Suttle, C.A.; Jeffrey, W.H. The role of sunlight in the removal and repair of viruses in the sea. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1998, 43, 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnell, M.E.R.; Subbarao, K.; Feinstone, S.M.; Taylor, D.R. Inactivation of the coronavirus that induces severe acute respiratory syndrome, SARS-CoV. J. Virol. Methods 2004, 121, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratelli, A. Canine coronavirus inactivation with physical and chemical agents. Vet. J. 2008, 177, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, A.G.; Jackson, G.A. Viral dynamics: A model of the effects of size, shape, motion and abundance of single-celled planktonic organisms and other particles. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1992, 89, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, R.T.; Fuhrman, J.A. Virus decay and its causes in coastal waters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997, 63, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wartecki, A.; Rzymski, P. On the coronaviruses and their associations with the aquatic environment and wastewater. Water 2020, 12, 1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyer, A.; Şanlıdağ, T. The fate of SARS-CoV-2 in the marine environments: Are marine environments safe of COVID-19? Erciyes Med. J. 2021, 10–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, A.; Abad, F.X.; Pintó, R.M. Human pathogenic viruses in the marine environment. In Oceans and Health: Pathogens in the Marine Environment; Belkin, C., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 109–131. ISBN 9780387237091. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, H.W.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.; Kim, Y.; Kim, J.H.; Cho, J.Y.; Kim, S.; Kang, H.; Kim, S.; Park, S.; et al. Viable SARS-CoV-2 in various specimens from COVID-19 patients. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 26, 1520–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobsey, M.D.; Meschke, J.S. Virus Survival in the Environment with Special Attention to Survival in Sewage Droplets and Other Environmental Media of Fecal or Respiratory Origin; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003; p. 70. [Google Scholar]

- Geller, C.; Varbanov, M.; Duval, R.E. Human coronaviruses: Insights into environmental resistance and its influence on the development of new antiseptic strategies. Viruses 2012, 4, 3044–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraswat, R.; Kouthanker, M.; Kurtarkar, S.; Nigam, R.; Linshy, V.N. Effect of salinity induced pH changes on benthic foraminifera: A laboratory culture experiment. Biogeosciences Discuss. 2011, 8, 8423–8450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOAA. Why Is the Ocean Salty? Available online: https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/whysalty.html (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- NOAA. Ocean Acidification. Available online: https://www.noaa.gov/education/resource-collections/ocean-coasts/ocean-acidification.html (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- Natarajan, P.; Miller, A. Recreational Infections. In Infectious Diseases; Cohen, J., Powerly, W.G., Opal, S.M., Eds.; Elsevier Ltd.: London, UK, 2017; pp. 643–646. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, D.S. Infections Acquired from Animals Other Than Pets. In Infectious Diseases; Cohen, J., Powderly, W.G., Opal, S.M., Eds.; Elsevier Ltd.: London, UK, 2017; pp. 663–669. [Google Scholar]

- Polo, D.; Lois, M.; Fernández-Núñez, M.T.; Romalde, J.L. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in bivalve mollusks and marine sediments. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 786, 147534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sano, T.; Yamaki, T.; Fukuda, H. A novel carp coronavirus: Characterization and pathogenicity. In Proceedings of the Fishery Health Conference, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 19–21 July 1988; p. 160. [Google Scholar]

- Schütze, H. Coronaviruses in Aquatic Organisms. In Aquaculture Virology; Kibenge, F., Godoy, M., Eds.; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 327–335. ISBN 9780128017548. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, W. Aquaculture Production and Trade Trends: Carp, Tilapia and Shrimp Weimin Miao; FAO RAP: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Karnai, L.; Szucs, I. Outlooks and Perspectives of the Common Carp Production. Ann. Polish Assoc. Agric. Agribus. Econ. 2018, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batts, W.N.; Goodwin, A.E.; Winton, J.R. Genetic analysis of a novel nidovirus from fathead minnows. J. Gen. Virol. 2012, 93, 1247–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwanowicz, L.R.; Goodwin, A.E. A new bacilliform fathead minnow rhabdovirus that produces syncytia in tissue culture. Arch. Virol. 2002, 147, 899–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, S.D.; Raymond, M.J.; Krell, P.J.; Kropinski, A.M.; Stevenson, R.M.W. Novel chinook salmon bafinivirus isolation from ontario fish health monitoring. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Seventh International Symposium on Aquatic Animal Health; Portland, OR, USA, 31 August–4 September 2014, p. 242.

- Ahne, W. Viral infections of aquatic animals with special reference to Asian aquaculture. Annu. Rev. Fish Dis. 1994, 4, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, T.; Okamoto, H.; Kageyama, T.; Kobayashi, T. Viremia-associated ana-aki-byo, a new viral disease in color carp Cyprinus carpio in Japan. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 2000, 39, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossart, G.D.; Schwartz, J.C. Acute Necrotizing Enteritis Associated with Suspected Coronavirus Infection in Three Harbor seals (Phoca vitulina). J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 1990, 21, 84–87. [Google Scholar]

- Nollens, H.H.; Wellehan, J.F.X.; Archer, L.; Lowenstine, L.J.; Gulland, F.M.D. Detection of a respiratory coronavirus from tissues archived during a pneumonia epizootic in free-ranging pacific harbor seals Phoca vitulina richardsii. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 2010, 90, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihindukulasuriya, K.A.; Wu, G.; St. Leger, J.; Nordhausen, R.W.; Wang, D. Identification of a Novel Coronavirus from a Beluga Whale by Using a Panviral Microarray. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 5084–5088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youdao, N. Can freshwater fish transmit novel coronavirus? Chinese W. 2020, 19–20. Available online: https://covid-19.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202003/20/WS5e73f268a310128217280910.html (accessed on 6 August 2021).

- Casanova, L.M.; Jeon, S.; Rutala, W.A.; Weber, D.J.; Sobsey, M.D. Effects of air temperature and relative humidity on coronavirus survival on surfaces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 2712–2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araujo, M.B.; Naimi, B. Spread of SARS-CoV-2 Coronavirus likely to be constrained by climate. medRxiv 2020, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, R.; Randall, D.; Augustine, G. Fisología Animal: Mecanismos y Adaptaciones, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill-Interamericana: Madrid, España, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Peteri, A. Cyprinus carpio (Linnaeus, 1758). In Cultured Aquatic Species Fact Sheets; Crespi, V., New, M., Eds.; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2009; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Melero, M.; Rodríguez-Prieto, V.; Rubio-García, A.; García-Párraga, D.; Sánchez-Vizcaíno, J.M. Thermal reference points as an index for monitoring body temperature in marine mammals. BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuñez-Nogueira, G. Coronavirus en aves acuáticas. Kuxulkab' 2020, 26, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, D.K.W.; Leung, C.Y.H.; Gilbert, M.; Joyner, P.H.; Ng, E.M.; Tse, T.M.; Guan, Y.; Peiris, J.S.M.; Poon, L.L.M. Avian Coronavirus in Wild Aquatic Birds. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 12815–12820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Hu, Z. A review of studies on animal reservoirs of the SARS coronavirus. Virus Res. 2008, 133, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, C.M.; Durigon, E.L.; Thomazelli, L.M.; Ometto, T.; Marcatti, R.; Nardi, M.S.; de Aguiar, D.M.; Pinho, J.B.; Petry, M.V.; Neto, I.S.; et al. Divergent coronaviruses detected in wild birds in Brazil, including a central park in São Paulo. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2019, 50, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hepojoki, S.; Lindh, E.; Vapalahti, O.; Huovilainen, A. Prevalence and genetic diversity of coronaviruses in wild birds, Finland. Infect. Ecol. Epidemiol. 2017, 7, 1408360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Sales Lima, F.E.; Gil, P.; Pedrono, M.; Minet, C.; Kwiatek, O.; Campos, F.S.; Spilki, F.R.; Roehe, P.M.; Franco, A.C.; Maminiaina, O.F.; et al. Diverse gammacoronaviruses detected in wild birds from Madagascar. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2015, 61, 635–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhart, M.; Vanstreels, R.E.T.; Gallo, L.; Cook, R.A.; Karesh, W.B. Serological survey for select infectious agents in wild magellanic penguins (Spheniscus magellanicus) in Argentina, 1994–2008. J. Wildl. Dis. 2020, 56, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, K.M.; Karesh, W.B.; Majluf, P.; Paredes, R.; Reul, A.H.; Stetter, M.; Braselton, W.E.; Puche, H.; Cook, R.A.; Kristine, M.; et al. Health Evaluation of Free-Ranging Humboldt Penguins (Spheniscus humboldti) in Peru. Avian Dis. 2008, 52, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karesh, W.B.; Uhart, M.M.; Frere, E.; Gandini, P.; Braselton, E.; Puche, H.; Cook, R.A. Health evaluation of free-ranging rockhopper penguins (Eudyptes chrysocomes) in Argentina. J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 1999, 30, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- FAO. Food Chain Crisis Early Warning Bulletin; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kydyrmanov, A.I.; Karamendin, K.O. Viruses of Marine Mammals and Metagenomic Monitoring of Infectious Diseases. Bull. Natl. Acad. Sci. Repub. Kazakhstan 2019, 4, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, A.; Pintó, R.M.; Guix, S. Foodborne viruses. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2016, 8, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chantanachookin, C.; Boonyaratpalin, S.; Kasornchandra, J.; Direkbusarakom, S.; Ekpanithanpong, U.; Supamataya, K.; Sriurairatana, S.; Flegel, T.W. Histology and ultrastructure reveal a new granulosis-like virus in Penaeus monodon affected by yellow-head disease. Dis. Aquat. Org. 1993, 17, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Rosa-Velez, J.; Cedano-Thomas, Y.; Cid-Becerra, J.; Mendez-Payan, J.C.; Vega-Perez, C.; Zambrano-Garcia, J.; Bonami, J.R. Presumptive detection of yellow head virus by reverse transcriptasepolymerase chain reaction and dot-blot hybridization in Litopenaeus vannamei and L. stylirostris cultured on the Northwest coast of Mexico. J. Fish Dis. 2006, 29, 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, P.J.; Cowley, J.A.; Spann, K.M.; Hodgson, R.A.J.; Hall, M.R.; Withychumnarnkul, B. Yellow head complex viruses: Transmission cycles and topographical distribution in the Asia-Pacific region. In Proceedings of the the New Wave: Proceedings of the Special Session of Sustainable Shrimp Culture, World Aquaculture 2001, Baton Rouge, LA, USA, January 2001; Browdy, C.L., Jory, D.J., Eds.; World Aquaculture Society: Baton Rouge, LA, USA, 2001; pp. 292–302. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, P.J.; Winton, J.R. Emerging viral diseases of fish and shrimp. Vet. Res. 2010, 41, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, M. Climate Change and the Neglected Tropical Diseases, 1st ed.; Rollinson, D., Stothard, R., Eds.; Elsevier Ltd.: London, UK, 2018; Volume 100, ISBN 9780128151693. [Google Scholar]

- Al-taee, S.K.; Al-jumaa, Z.M.; Ali, F.F. Coronavirus and COVID-19 disease in aquatic animals´aspects. Vet. Pract. 2020, 21, 107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, Q.; Guo, D. Emerging coronaviruses: Genome structure, replication, and pathogenesis. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gheblawi, M.; Wang, K.; Viveiros, A.; Nguyen, Q.; Zhong, J.C.; Turner, A.J.; Raizada, M.K.; Grant, M.B.; Oudit, G.Y. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2: SARS-CoV-2 Receptor and Regulator of the Renin-Angiotensin System: Celebrating the 20th Anniversary of the Discovery of ACE2. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 1456–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fichtner, D.; Bergmann, S.M.; Dauber, M.; Enzmann, P.J.; Granzow, H.; Schmidt-Posthaus, H.; Et, A. Dituation of Fish Epidemics in Germany and Selected Case Reports from the National Reference Laboratory, in XII. Gemeninschaftstagung der Deutschen, der Österreichischen und der Schweizer Sektion der European Association of Fish Pathologists (EAFP); European Association of Fish Pathologists: Jena, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Damas, J.; Hughes, G.M.; Keough, K.C.; Painter, C.A.; Persky, N.S.; Corbo, M.; Hiller, M.; Koepfli, K.P.; Pfenning, A.R.; Zhao, H.; et al. Broad host range of SARS-CoV-2 predicted by comparative and structural analysis of ACE2 in vertebrates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 22311–22322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordecai, G.J.; Hewson, I. Coronaviruses in the Sea. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boxman, I.L.A.; Tilburg, J.J.H.C.; te Loeke, N.A.J.M.; Vennema, H.; Jonker, K.; de Boer, E.; Koopmans, M. Detection of noroviruses in shellfish in the Netherlands. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2006, 108, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxman, I.L.A. Human enteric viruses occurrence in shellfish from european markets. Food Environ. Virol. 2010, 2, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO/WHO. Viruses in Food: Scientific Advice to Support Risk Management Activities; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2008; Volume 13. [Google Scholar]

- EFSA. Scientific Opinion on an update on the present knowledge on the occurrence and control of foodborne viruses. EFSA J. 2011, 9, 1–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumpey, T.M.; Suarez, D.L.; Perkins, L.E.L.; Senne, D.A.; Lee, J.; Lee, Y.J.; Mo, I.P.; Sung, H.W.; Swayne, D.E. Evaluation of a High-Pathogenicity H5N1 Avian Influenza A Virus Isolated from Duck Meat. Avian Dis. 2003, 47, 951–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Advice for the Public; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zaporozhets, T.S.; Besednova, N.N. Biologically active compounds from marine organisms in the strategies for combating coronaviruses. AIMS Microbiol. 2020, 6, 470–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad Martinez, M.J.; Bedoya Del Olmo, L.M.; Bermejo Benito, P. Natural marine antiviral products. Stud. Nat. Prod. Chem. 2008, 35, 101–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehn, F.E.; Gunasekera, S.P.; Niel, D.N.; Cross, S.S. Halitunal, an unusual disterpene aldehyde from the marine alga Halmeda tuna. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991, 32, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donia, M.; Hamann, M.T. Marine natural products and their potential applications as anti-infective agents. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2003, 3, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakao, Y.; Masuda, A.; Matsunaga, S.; Fusetani, N. Pseudotheonamides, serine protease inhibitors from the marine sponge Theonella swinhoei. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 2425–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Archila, L.G.; Rugeles, M.T.; Zapata, W. Actividad antiviral de compuestos aislados de esponjas marinas. Rev. Biol. Mar. Oceanogr. 2014, 49, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lira, S.P.; Seleghim, M.H.R.; Williams, D.E.; Marion, F.; Hamill, P.; Jean, F.; Andersen, R.J.; Hajdu, E.; Berlinck, R.G.S. A SARS-coronovirus 3CL protease inhibitor isolated from the marine sponge Axinella cf. corrugata: Structure elucidation and synthesis. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2007, 18, 440–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, D.; Patamia, V.; Scala, A.; Sciortino, M.T.; Piperno, A.; Rescifina, A. Putative inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 main protease from a library of marine natural products: A virtual screening and molecular modeling study. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelrheem, D.A.; Ahmed, S.A.; Abd El-Mageed, H.R.; Mohamed, H.S.; Rahman, A.A.; Elsayed, K.N.M.; Ahmed, S.A. The inhibitory effect of some natural bioactive compounds against SARS-CoV-2 main protease: Insights from molecular docking analysis and molecular dynamic simulation. J. Environ. Sci. Health—Part A Toxic/Hazardous Subst. Environ. Eng. 2020, 55, 1373–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishchenko, N.P.; Krylova, N.V.; Iunikhina, O.V.; Vasileva, E.A.; Likhatskaya, G.N.; Pislyagin, E.A.; Tarbeeva, D.V.; Dmitrenok, P.S.; Fedoreyev, S.A. Antiviral potential of sea urchin aminated spinochromes against herpes simplex virus type 1. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedoreyev, S.A.; Krylova, N.V.; Mishchenko, N.P.; Vasileva, E.A.; Pislyagin, E.A.; Iunikhina, O.V.; Lavrov, V.F.; Svitich, O.A.; Ebralidze, L.K.; Leonova, G.N. Antiviral and antioxidant properties of echinochrome A. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, S.; Yousefzadi, M.; moein, S.; Rezadoost, H.; Bioki, N.A. Identification and antioxidant of polyhydroxylated naphthoquinone pigments from sea urchin pigments of Echinometra mathaei. Med. Chem. Res. 2016, 25, 1476–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.T.; Ali, A.; Wang, Q.; Irfan, M.; Khan, A.; Zeb, M.T.; Zhang, Y.J.; Chinnasamy, S.; Wei, D.Q. Marine natural compounds as potents inhibitors against the main protease of SARS-CoV-2—A molecular dynamic study. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021, 39, 3627–3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijayaraj, R.; Altaff, K.; Rosita, A.S.; Ramadevi, S.; Revathy, J. Bioactive compounds from marine resources against novel corona virus (2019-nCoV): In silico study for corona viral drug. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubilar, T.; Cardozo, D. Los erizos de mar y su potencial terapéutico para tratar Covid-19. Atek 2020, 1479, 375–384. [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri Elena, S.; Tamara, R.; Ayelén, G.; Marisa, A.; Seiler, E.N.; Mercedes, V.P.; Agustín, G.; Chaar, F.; Pia, F.J.; Lucas, S. Sea urchin pigments as potential therapeutic agents against the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 based on in silico analysis. ChemRxiv 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubilar Panasiuk, C.T.; Barbieri, E.S.; Gázquez, A.; Avaro, M.; Vera Piombo, M.; Gittardi Calderón, A.A.; Seiler, E.N.; Fernandez, J.P.; Sepúlveda, L.R.; Chaar, F. In silico analysis of sea urchin pigments as potential therapeutic agents against SARS-CoV-2: Main protease (Mpro) as a target. ChemRxiv 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce Rey, L.D.R.; del Barrio Alonso, G.D.C.; Spengler Salabarría, I.; Resik Aguirre, S.; Roque Quintero, A. Evaluación de la actividad antiviral del alga parda Sargassum fluitans frente a Echovirus 9. Rev. Cubana Med. Trop. 2018, 70, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, B. El sargazo. La Cienc. y el Hombre 2019, XXXII, 1. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).