Abstract

Currently, there is a lack of systematic and quantitative analytical tools for dust emission control in open-pit iron mines. To address this research gap, this study constructs a comprehensive evaluation index system by integrating the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) and the fuzzy comprehensive evaluation (FCE) method. The framework includes four first-level indicators, 12 s-level indicators and 30 third-level indicators. The structural design was informed by laws and regulations, the relevant literature and the principle of dust hierarchical control to ensure the theoretical and empirical basis for the selection of indicators. The evaluation process was based on on-site monitoring data and production ledgers from the open-pit iron mine of the Shuichang Mine, as well as the results of multiple rounds of consultation by the Delphi method group composed of 30 experts in related industries. The results show that the comprehensive score of the mine is 87.14 points, and the overall prevention and control is effective. But the performance of each dimension is unbalanced: fundamental data on production processes scored highest, while individual exposure and protection measures were relatively weak, indicating that the personnel protection link needs to be strengthened. Sensitivity analysis further verified the structural stability of the index system and identified the ventilation and dust removal system as a key driving factor. This framework can provide quantitative decision support for mine managers, enhancing the precision and overall effectiveness of dust control through the accurate identification of weaknesses and optimized resource allocation.

1. Introduction

As a primary method of mineral resource development, open-pit mining generates significant fugitive dust during drilling, blasting, loading, and transportation. This kind of dust has the characteristics of multi-source emission, complex composition and wide influence, and often contains toxic substances such as free silica, arsenic and cadmium. Its diffusion process is affected by the coupling of meteorological conditions and production technology, which not only causes damage to the ecosystem of the mining area but also increases the risk of workers suffering from pneumoconiosis and chronic respiratory diseases [1,2]. The inherent complexity of dust pollution, involving multi-factor coupling and multi-dimensional hazards, presents two key challenges for traditional single-index evaluation methods. Namely, it is difficult to determine parameter weights scientifically due to dynamic changes, and there is no universal method to normalize dimensional differences across indicators.

As the core bottleneck restricting the green and safe production of mines, the dust pollution of open-pit mines has been deeply explored in the aspects of the temporal and spatial distribution law and influencing factors of dust pollution, and dust health damage mechanisms, dust pollution prevention and control technologies, and systematic achievements have been formed, which provides important support for the construction of a dust risk assessment system in the future. In terms of the temporal and spatial distribution law and influencing factors of dust pollution, Deng et al. [3] found that the dustfall flux in spring and summer at the Wuhai open-pit mine far exceeded the annual average value and analyzed and confirmed that wind speed was the core factor affecting the dustfall flux. Luo et al. [4] built a multiple regression model based on the Haerwusu open-pit mine. Their results indicated that among meteorological factors influencing the PM concentration, humidity exhibited the greatest relative effect, while temperature inversion showed the least. Li et al. [5] found that the meteorological conditions in the mornings during winter at the Anjialing open-pit mine of Pingshuo, Shanxi, were stable, dust was easy to gather, and the dust exceeded the standard most seriously at the elevation of 1400. Zhang et al. [6] systematically analyzed the dust diffusion law under different vehicle speeds of mining trucks and built a high-precision dust concentration prediction model. Wu et al. [7] simulated the dust diffusion process of an open-pit mine in Inner Mongolia. The results showed that an increase in dust diffusion speed was inversely proportional to particle size, and the dust escape rate in the mining pit was negatively correlated with particle size. Tian et al. [8] took the Pingshuo open-pit coal mine as the research object and deeply discussed the coupling relationship between wind speed, air humidity and dust concentration. The study found that when the wind speed was about 1.5 m/s and the air humidity was about 45%, the dust mass concentration in the mine pit reached the lowest level. From the perspective of the health damage mechanism of dust, Entwistle et al. [9] pointed out that potential toxic elements, such as arsenic and cadmium, contained in the dust of metal mines can generate reactive oxygen species through the Fenton reaction, which can cause oxidative stress and DNA damage in the body. Jiao et al. [10] found that the proportion of inhalable particles, heavy metals and free SiO2 within the accumulated dust inside a rock shovel operator’s cabin exceeded that of the coal shovel. The health risk assessment results showed that the rock shovel cab was close to moderate harm. Liu et al. [11] pointed out that the content of free SiO2 is the key threshold affecting the risk of silicosis. When the content of free SiO2 exceeds 10%, the risk of silicosis will increase sharply. Myshchenko et al. [12] took the workers of Polish open-pit mines as the research object and found that worker exposure to respirable crystalline silica and noise directly involved in the mining process was higher than that of auxiliary workers. In terms of dust pollution prevention and control technology, Liu et al. [13] proposed a prevention and control scheme of “closed space + dust removal system” for the problem that the dust concentration increased sharply while unloading material at the Haerwusu mine crushing station. The on-site application data showed that the dust removal efficiency of PM2.5, PM10 and TSP reached 97%, 99.6% and 98.3%, respectively. Zhao et al. [14] developed a composite dust suppressant and confirmed that it has a high-efficiency dust suppression effect in the mining and loading process, which can reduce the diffusion range of burnt rock dust. Li et al. [15] took the Panzhihua open-pit–underground joint iron mine as the research object and used the AHP-FCE method to identify 36 key risk factors in six categories. The evaluation results showed that the mine was at a medium risk level, and geological conditions and environmental factors were the main sources of risk.

In summary, the existing research has notable limitations. Most studies focus on a single process link, failing to systematically reveal the internal mechanisms of multi-factor coupling effects, which limits risk assessment coverage across the entire mining process. Furthermore, there is often a disconnect between health risk assessments, engineering prevention, and control technologies, and a closed-loop management system integrating risk identification, control optimization, and effectiveness feedback has not yet been established. As a result, the guidance provided by assessment outcomes on field practice remains limited. Additionally, existing models often focus on a single dimension and lack a comprehensive, multi-dimensional assessment framework that integrates meteorological, technological, and health-effect factors. In order to make up for the above research gaps, this study takes the Shuichang Mine as an example to construct a comprehensive assessment model for dust pollution prevention and control. The contributions of this work are numerous. First, in the construction of the indicator system, it overcomes the limitation of single indices by establishing a multi-dimensional hierarchical structure. Indicator selection adheres to the principles of relevance, quantifiability, and practicality, with weights and criteria determined through expert demonstration and field investigation. Second, regarding application, this study bridges the gap from theoretical models to field verification and practical guidance. The model’s reliability is validated with on-site data from the Shuichang Mine, enabling accurate identification of key risk sources and prioritization of control measures. Ultimately, this study proposes an integrated “assessment–technology–management” solution, offering a replicable paradigm for precise dust control and occupational health management in open-pit mines.

2. Current Status of the Shuichang Open-Pit Iron Mine

2.1. Environmental Conditions

The Shuichang Mine is located in Qian’an City, Tangshan City, Hebei Province, at the southern foot of the Yanshan Mountains and on the left bank of the Luan River. The mine has a superior geographical location and convenient transportation. The surrounding highway and railroad networks are well developed, which facilitates the transportation of ore. There are many villages around the mining area, and the population is relatively dense. Therefore, the dust pollution caused by the mine directly affects the living environment of the surrounding residents. The area is located in the temperate monsoon climate zone, with distinct seasonal changes, cold and dry winters, and hot and rainy summers. The annual average wind speed is about 1.8 m/s, which has a certain impact on the dust diffusion mode.

2.2. Production Overview

The Shuichang open-pit iron mine operated by Shougang Mining Company (Tangshan, China) is an important supply base for iron ore raw materials. Its construction began in 1968, and it was put into operation in 1969. After decades of development and technological progress, it has developed into one of China’s large-scale comprehensive open-pit mining and mineral processing enterprises. It maintains stable annual production, handling a total of 48 million tons of mining and stripping, with an iron ore production capacity of 10 million tons. Despite declining resource reserves as mining depth increases, high production levels have been sustained through continuous optimization of the mining layout. The mining process involves medium-deep hole blasting, electric shovel loading, and material transport by dump trucks to the crushing station. The beneficiation process employs two-stage grinding and three-stage magnetic separation. The crushed ore is ground and magnetically separated, then filtered and dehydrated to produce iron concentrate.

2.3. Primary Sources of Dust

Dust generation in open-pit mines mainly occurs in four major operation stages: drilling and blasting, loading and unloading transportation, crushing and magnetic separation, and tailings treatment. During the drilling and blasting process, the rotary drill breaks and grinds the ore at high speed, and the generated rock chips escape through the gap between the drill rod and the drill hole wall and spread to the surrounding mining area through the airflow. During blasting, the high-energy shock wave pushes the smoke and dust in the gun hole out, causing them to spread rapidly into the environment. During the loading and unloading transportation stage, when the bucket is lifted from the stockpile, the change in the stress structure will cause local sliding and collapse, resulting in a large amount of dust. When the material falls from the bucket into the transport truck, the strong impact caused by the drop causes the dust to spread in a jet shape. The driving of the transport truck continuously generates dust through the friction between the tires and the road surface and the vibration of the vehicle. The amount of dust generated is directly proportional to the road roughness and vehicle speed. In the crushing and magnetic separation stage, dust is generated by mechanical compression and ore crushing in the crusher, and the height difference between the discharge port and the receiving point causes the dust to spread through the airflow disturbance. In the tailings treatment process, the surface moisture of the tailings residue after dehydration evaporates, making the material susceptible to wind erosion and subsequent dust generation.

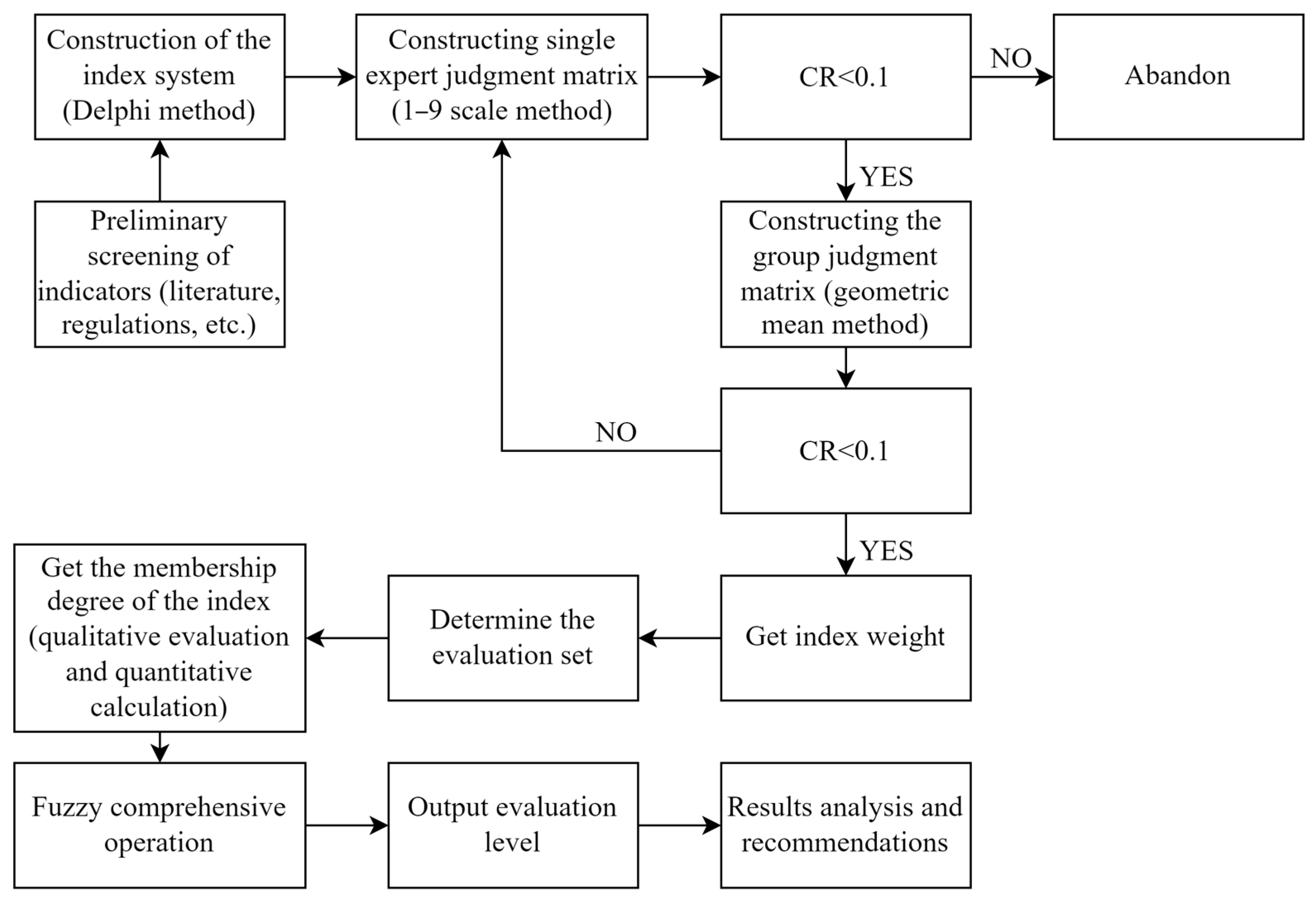

3. Construction of the Comprehensive Dust Risk Evaluation System

In this study, a comprehensive evaluation model combining AHP and FCE was used to systematically evaluate the dust control measures of open-pit iron mines. AHP was used to scientifically determine the weight of each evaluation index and effectively decompose the complex multi-factor decision-making problem. FCE was used to deal with the inherent fuzziness and subjectivity in the evaluation process and to transform the qualitative evaluation into quantitative analysis. The overall research process includes four main stages: index system construction, weight calculation, membership determination, fuzzy synthesis and result analysis. The specific process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of indicator weight determination and comprehensive evaluation.

3.1. Establishing the Hierarchical Structure

To ensure the scientific validity and practical applicability of the evaluation index system, the selection of indicators in this study was grounded in the following three aspects:

(1) Theoretical basis: The relevant domestic and international literature on dust control and occupational health risk assessment was referenced to ensure comprehensive coverage of dust generation sources, transmission pathways, and exposure risks to personnel.

(2) Legal basis: Legal and regulatory provisions, including the Occupational Disease Prevention and Control Law of the People’s Republic of China, the Classification Catalogue of Occupational Hazard Factors, and the Workplace Occupational Health Management Regulations, were strictly consulted. Principle-based stipulations in these documents were translated into quantifiable evaluation indicators.

(3) Empirical basis: Through field investigations and expert interviews conducted in multiple open-pit mines, key parameters that are both obtainable in actual production environments and capable of accurately reflecting the level of dust control were selected. This approach ensured the practical value of the indicator system.

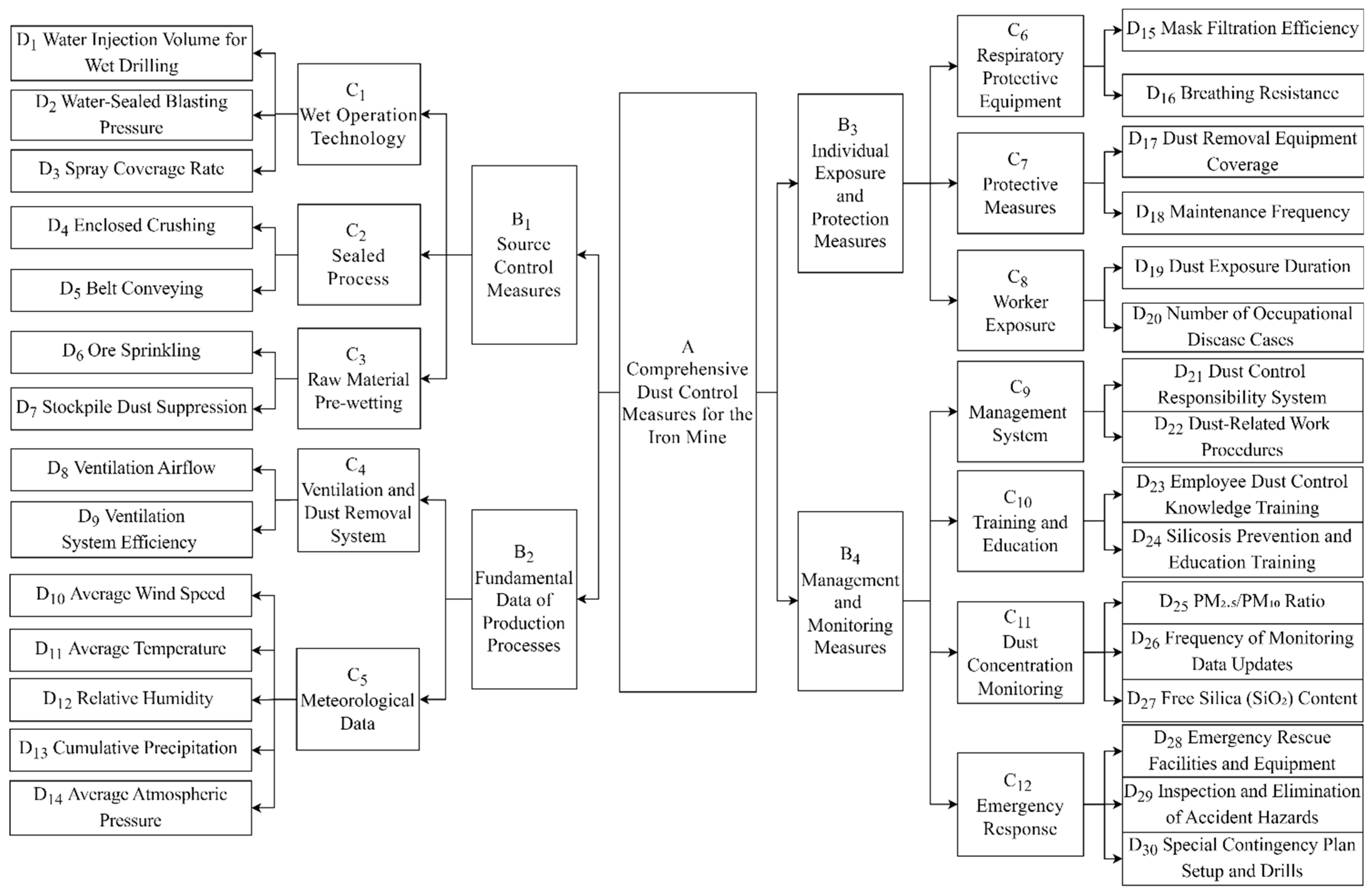

Indicator screening was implemented using the Delphi method. This study established a group of 30 experts, and the selection criteria were more than 10 years of practical or research experience in the mining industry, occupational health, safety management or environmental engineering. The expert group comprised 15 safety managers from large open-pit mines, five researchers from occupational hazard assessment institutions, and 10 university professors specializing in safety engineering. Through two rounds of questionnaire surveys, the final evaluation system was determined, consisting of four first-level indicators, 12 s-level indicators and 30 third-level indicators. The hierarchical structure is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Comprehensive dust risk prevention and control evaluation indicators for open-pit mines.

3.2. Weight Determination and Consistency Test

Based on the index system, the 1–9 scale method was adopted to compare the influence degree of the same-level index on the upper-level index. Among them, a value of 1 indicates that the two elements are of equal importance, whereas a value of 9 signifies that one element is of extreme importance compared to the other. The specific meanings corresponding to the scale are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Scale values and corresponding meanings.

According to the expert judgment matrix results, the geometric mean aggregation method was used to construct the group judgment matrix, and then the weight determination and consistency test were completed [16]. Taking the wet operation technology C1 as an example, the judgment matrix is set as , where represents the matrix’s order and represents the result of the importance comparison between element and element . The constructed judgment matrix is as follows:

(1) The weights were calculated based on the Normalized Geometric Mean. The detailed steps are outlined below:

a. Calculate the geometric mean of the elements in the i-th row of the judgment matrix:

b. Perform normalization processing to obtain the weight vector :

(2) The consistency test was performed. The steps are as follows:

a. According to the constructed judgment matrix, calculate the product of the matrix and the weight vector () by the characteristic root method, where the corresponding level weight vector is . The i-th element of the product is:

b. Solve for the maximum eigenvalue of the judgment matrix ():

c. Calculate the consistency index ():

d. Conduct a consistency check. This step necessitates determining the and the random consistency index (), where the value must be selected as a standard value according to the matrix order n. The specific values are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Random consistency index value.

According to the calculation results, , which means that the constructed judgment matrix meets the acceptable consistency standard, and the weight can reflect the true importance of the index; if the consistency requirement is not met, it means that the consistency of the judgment matrix is questionable. The judgment matrix requires readjustment until it successfully passes the consistency test. All indicators are weighted and tested for consistency according to this process, and the results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Evaluation factor set and corresponding weight set.

4. Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation

The core of fuzzy comprehensive evaluation is to clarify the degree of membership of each index in the comment set. According to the actual needs, the comment set was set as . The specific definitions are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Grade symbols and their corresponding descriptions.

4.1. Determination of Indicator Membership Degrees

The membership degree of the lowest-level indicators was determined by different methods according to the data type:

(1) Qualitative indicators. A questionnaire survey was conducted, inviting experts to directly specify the membership degree of each indicator for different evaluation levels based on their expertise. The final membership degree for each indicator was calculated as the arithmetic mean of all expert ratings. This approach effectively retained the fuzzy information inherent in qualitative assessments.

(2) Quantitative indicators. The selection of critical points for the membership functions was based on industry standards, regulatory limits, literature-recognized thresholds, or expert consultation, ensuring objectivity in the conversion process. For evaluation indicators that follow an upper-limit-type measurement, the corresponding distribution function was defined as follows, where represents the actual value of each index and represents its degree of membership in the fuzzy subset. For indicators that follow a lower-limit-type measurement, the distribution function takes the opposite form.

For higher-level indicators, the weighted average fuzzy synthesis operator was applied to calculate their memberships () by aggregating information from the underlying indicators layer by layer [16]. To ensure internal consistency in the calculation and accurately preserve the characteristics of the fuzzy operations, the membership vectors for intermediate levels retained four decimal places. This prevented the accumulation of non-negligible errors during the step-by-step synthesis process. Taking the wet operation technology C1 as an example, its weight set is , the sub-index membership matrix is expressed as , and the calculation is shown in Equation (18). The statistical results of the overall index membership are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Statistical results of indicator membership degrees.

4.2. Determination of Indicator Scores

This section calculates the indicator score based on the membership matrices of evaluation indicators at each level [16]. The score is divided into five intervals: 80–100 (), 60–80 (), 40–60 (), 20–40 (), and 0–20 (). Taking wet operation technology (C1) as an example, represents its corresponding weight set and represents the evaluation level vector assigned after quantitative conversion.

The final score for the wet operation technique indicator is 85.81. According to the corresponding scoring ranges, the comprehensive evaluation result is ‘’. All hierarchical indicators were scored using this evaluation process, and the results are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Comprehensive scores of indicators.

5. Sensitivity Analysis

To assess the robustness of the index system constructed in this study, and to accurately identify the key driving factors influencing the evaluation results, a systematic sensitivity analysis was conducted using the one-factor-at-a-time (OAT) method. This approach clarifies causal relationships by varying the weight of a single indicator while observing corresponding changes in the output. In order to improve efficiency and ensure rigor, the secondary indicators (C series) under each primary indicator (B1–B4) with the highest local weight were selected as the main disturbance objects because their contributions to the final result were the largest, and they were potential key leverage points.

During the analysis, the weight of each key indicator was increased and decreased by 10% relative to its benchmark value [16]. This range was chosen to simulate reasonable differences of opinion that may exist within the expert group. When the weight of an indicator was disturbed, the weights of all other indicators were normalized and adjusted in the original proportion to ensure that the sum of all weights is constant at 100%. The observed output variables included the overall evaluation score and grade, as well as the scores and grades of the four first-level indicators. The results are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Sensitivity analysis of key parameter perturbation on evaluation index scores.

As shown in Table 7, the selected key indicators have a significant asymmetric impact on the evaluation results. Among them, the ventilation and dust removal system (C4) has the most prominent impact on the fundamental data of production processes (B2) and the comprehensive dust control measures for the iron mine (A). A 10% increase in the weight of C4 leads to a rise of 1.44 points in the score of B2 and drives the overall score of A up by 0.25 points, indicating that this indicator serves as an important positive leverage point in the system evaluation. In contrast, variations in the weights of the other indicators mainly result in localized impacts on their respective upper-level indicators, with the magnitude of change remaining within 1 point, indicating that their regulatory effects are relatively limited. Overall, when the weight of each indicator is disturbed within the range of 10%, the rating level of all evaluated objects remains unchanged, demonstrating that the constructed index system possesses good structural stability. However, the high sensitivity of C4 indicates that in practical pollution prevention and control, precise management and optimization of the measures associated with this indicator should be strengthened to improve the overall control effectiveness.

6. Results and Discussion

The comprehensive score results show that the overall evaluation of dust control in the open-pit iron mine was ‘’ (87.14 points), reflecting the effective operation of the prevention and control system as a whole. However, the difference in scores between the first-level indicators also reveals the strengths and weaknesses within the system, which is highly related to the “continuous improvement” principle advocated by the International Occupational Hygiene Association (IOHA). Among them, the fundamental data of production processes is the most prominent, while the individual exposure and protection measures are relatively weak, and the difference between the two is obvious, indicating that the mine has achieved remarkable results in engineering control and management, but the final protective layer for safeguarding workers’ health requires further strengthening. These findings are consistent with the widely recognized “hierarchy of controls” principle in dust management, which prioritizes engineering control measures, followed by management means and individual protection. The current scoring structure confirms that the mine’s overall control strategy is moving in the right direction.

In terms of source control measures, the mine received a ‘’ rating (88.44 points), establishing a solid foundation for the entire dust control system. The high score primarily stems from the effective implementation of key measures, such as enclosed processes and raw material pre-wetting. These measures directly target the dust generated by mechanical disturbance and wind force during the crushing and transfer of ore and effectively suppress the spread of dust from the source. However, some third-level indicators also highlight specific areas for potential improvement. For example, the water injection volume of wet drilling only received a ‘’ rating. Insufficient water injection may lead to insufficient bonding of rock powder during the drilling process, increasing the risk of dust escape. It is recommended to establish a dynamic correlation between water injection volume, drill hole diameter, and drilling speed based on relevant operating specifications to achieve precise dust suppression. In addition, the score of stockpile dust suppression was only ‘’, exposing the problem of dust raising in static material piles under wind erosion. It is possible to consider evaluating the use of polymer dust suppressants or installing wind-proof and dust-suppression nets and other long-term measures to improve the ability of continuous dust suppression.

The category related to fundamental data on production processes achieved the highest score, mainly due to the performance of the ventilation and dust removal system. The key parameters, such as ventilation airflow and efficiency, showed that the system design was highly matched with the mine production scale and played a key role in dust collection and emission control. However, the meteorological data index performed poorly and became an obvious shortcoming. In particular, the scores of average temperature and relative humidity were low, indicating that the dynamic changes in external meteorological conditions were potential risk factors affecting the stability of the system. For example, the influence of temperature inversion on ventilation efficiency is completely consistent with the mechanism of the inversion layer, leading to pollutant retention in the study of urban air pollution [17]. At present, the system may lack the ability to adjust dynamically in real time according to meteorological conditions. It is suggested to introduce the intelligent linkage control mechanism between meteorological monitoring and the ventilation system to realize the automatic adjustment of fan operation parameters according to the changes in temperature and humidity, so as to enhance the adaptability to extreme working conditions.

In the category of individual exposure and protection measures, although the overall rating was ‘’, the worker exposure indicator only received ‘’, with particularly low performance in the sub-item of dust exposure duration. This constitutes a key risk point in the system. If respiratory protective equipment lacks sufficient comfort, resulting in a decrease in the wearing compliance of employees, even if the filtration efficiency of the equipment itself meets the standard, its actual protective effect will be greatly reduced. Long-term exposure to high dust will significantly increase the risk of occupational diseases such as silicosis. In this regard, a two-pronged improvement strategy is recommended. First, the job scheduling system should be optimized to strictly implement shift rotation and mandatory rest breaks, thereby reducing the continuous exposure time for workers. Second, priority should be given to procuring protective equipment with low breathing resistance and high comfort, which will enhance worker compliance at the hardware level.

In terms of management and monitoring measures, the mine was rated as ‘’, mainly reflected in the sound system and complete training system. Notable deficiencies persist in the dust concentration monitoring link; specifically, the two items of free silica content monitoring and data update frequency have low scores. The free silica content is the core toxicological index for assessing the risk of silicosis. The “Global Plan for the Elimination of Silicosis”, jointly launched by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Labor Organization (ILO), strongly recommends regular and high-frequency monitoring of respirable crystalline silica. If the data is not updated in time, it will be difficult to achieve refined management and early warning based on real risks. The current problem reflects the lack of real-time accuracy in the monitoring network. It is recommended to promote upgrading monitoring technology, give priority to the deployment of real-time online monitoring equipment, and build a centralized data management platform, so as to improve the timeliness and accuracy of key toxicological index data, and realize the advancement from a sound system to “data-driven, precise control”.

Overall, the assessment results are consistent with the actual situation of the mine and the recent occupational hazard monitoring report, which proves that the proposed assessment system can draw objective, scientific and effective conclusions.

7. Conclusions

Based on the Shuichang Mine, this study constructs and verifies a comprehensive evaluation system for dust pollution control in open-pit iron mines that integrates AHP and FCE. The empirical analysis shows that the dust control of the mine is generally effective (the comprehensive score is 87.14, and the evaluation level is V). However, the performance within the system is unbalanced: the “basic data of the production process” performs well (the comprehensive score is 90.65), while the “individual exposure and protection” is relatively weak (the comprehensive score is 83.78). This reveals that personnel protection measures remain a current shortcoming and an area for improvement. The sensitivity analysis further confirms the robustness of the index system and accurately identifies the ventilation and dust removal system as the core driving factor affecting the overall situation. A slight change in its weight will have a significant impact on the total score (an increase of 10% in weight can cause the fundamental data of production processes score to increase by 1.44 points), which provides a clear scientific basis for managers to prioritize the optimization of key measures.

Based on the above considerations, we recommend that resources be invested first in the systematic maintenance and upgrading of the ventilation and dust removal system. This includes implementing regular maintenance and carrying out technical improvements on such equipment to reduce failure rates and ensure continuous, stable operation. In addition, the existing scheduling mechanism should be optimized to shorten the continuous exposure time of workers. The upgrading and replacement of protective equipment should be promoted to effectively enhance the individual protection efficiency of front-line personnel. At the same time, high-sensitivity real-time monitoring sensors should be deployed to build a full-domain perception network, and the existing data transmission foundation should be further consolidated to provide strong support for safe production and risk early warning.

It must be admitted that the assessment system constructed by this study still has certain limitations. First, the determination of the weight of the core indicators of the system mainly depends on the judgment of experts. Although structured methods were used to consolidate consensus as much as possible, the process may still introduce a degree of subjectivity, which could affect the complete objectivity of the evaluation results. Second, the current model is largely based on normal production and typical meteorological conditions, and it has not yet fully incorporated key causal parameters, such as inversion intensity, or dynamic external variables, like extreme weather events. This may limit the accuracy of risk assessment under special working conditions. Therefore, future research can be further deepened from the following directions:

(1) Expand the sample size of experts and field surveys and explore more robust methods for determining weights to improve the universality and objectivity of the model.

(2) Introduce Internet of Things sensors and remote sensing technology to build a real-time data acquisition network, enhancing the dynamic monitoring and real-time early warning capabilities of the model.

(3) Incorporate multi-source data, such as terrain, mining depth, and meteorological changes, into a systematic optimization model. This integration will promote the system’s evolution toward digitization and intelligence. In this way, accurate and dynamic dust risk assessment and early warning can be achieved, fully unleashing its potential for long-term environmental management in mining operations.

Author Contributions

D.T.: Funding acquisition and conceptualization. K.Y.: Writing—original draft preparation. J.Y.: Formal analysis. W.Q.: Writing—review and editing and project administration. X.W.: validation. J.W.: Data curation. J.S.: Investigation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Outstanding Youth Science Fund Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51704118), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2018YFC0808200), the Ministry of Emergency Management of the People’s Republic of China (No. zhishu-0013-2016AQ) and the Central Universities Fund Support (Nos. AQ1201A and 3142015105).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data set files are available from the Zenodo database. Accession number: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17962096.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Tian, S.; Liang, T.; Li, K. Fine road dust contamination in a mining area presents a likely air pollution hotspot and threat to human health. Environ. Int. 2019, 128, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanka, K.S.; Shukla, S.; Gomez, H.M.; James, C.; Palanisami, T.; Williams, K.; Chambers, D.C.; Britton, W.J.; Ilic, D.; Hansbro, P.M.; et al. Understanding the pathogenesis of occupational coal and silica dust-associated lung disease. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2022, 31, 210250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.Y.; Wu, H.X.; Zhao, T.N.; Shi, C.Q. Characteristics of atmospheric dustfall fluxes and particle size in an open pit coal mining area and surrounding areas. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, H.T.; Zhou, W.; Jiskani, I.M.; Wang, Z.M. Analyzing characteristics of particulate matter pollution in open-pit coal mines: Implications for green mining. Energies 2021, 14, 2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, R.X.; Li, Q.S.; Zhang, K.; Liu, Z.G.; Ren, Z.C. Multidimensional spatial monitoring of open pit mine dust dispersion by unmanned aerial vehicle. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, R.X.; Fu, S.G.; Fu, B.T.; Ding, X.Q. Prediction of dust migration and distribution characteristics in open pits at different vehicle speeds. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Yang, Z.; Wang, A.A.; Zhang, K.; Wang, B. A study on movement characteristics and distribution law of dust particles in open-pit coal mine. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, D.M.; Qu, W.Y.; Wang, J.Y.; Yao, J.; Fu, H.Y. Investigation of dust distribution patterns in open-pit coal mines under varying wind speed and air humidity. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 18662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Entwistle, J.A.; Hursthouse, A.S.; Marinho Reis, P.A.; Stewart, A.G. Metalliferous mine dust: Human health impacts and the potential determinants of disease in mining communities. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2019, 5, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.L.; Zhou, W.; Zhu, J.P.; Zhao, X.L.; Yan, J.L.; Wang, R.X.; Li, Y.N.; Lu, X. Study on dust hazard levels and dust suppression technologies in cabins of typical mining equipment in large open-pit coal mines in China. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.M.; Xu, Q.Q.; Zhao, J.P.; Nie, W.; Guo, Q.K.; Ma, G.G. Research status of pathogenesis of pneumoconiosis and dust control technology in mine—A review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myshchenko, I.; Pawlaczyk-Luszczynska, M.; Dudarewicz, A.; Bortkiewicz, A. Health risks due to co-exposure to noise and respirable crystalline silica among workers in the open-pit mining industry—Results of a preliminary study. Toxics 2024, 12, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Ao, Z.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, B.; Niu, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, L.; Yang, Z.; Xu, K.; Lu, W.; et al. Research on the physical and chemical characteristics of dust in open pit coal mine crushing stations and closed dust reduction methods. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.L.; Zhao, X.Y.; Han, F.W.; Song, Z.L.; Wang, D.; Fan, J.F.; Jia, Z.Z.; Jiang, G.G. A research on dust suppression mechanism and application technology in mining and loading process of burnt rock open pit coal mines. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2021, 71, 1568–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.L.; Deng, C.C.C.; Xu, J.Y.; Ma, Z.J.; Shuai, P.; Zhang, L.B. Safety risk assessment and management of Panzhihua open pit (OP)-underground (UG) iron mine based on AHP-FCE, Sichuan Province, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, W.-Y. Dataset of Design and Analysis of an Open-Pit Iron Mine Dust Pollution Evaluation Model Based on AHP-FCE Method; Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.Y.; Yang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Ni, C.J. Evolution characteristics of boundary layer inversion and its pollution effects during haze events in the Sichuan Basin. China Environ. Sci. 2025, 45, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.