1. Introduction

Urban climate studies examine the interactions between the atmosphere and urban form, linking climatic processes with people, infrastructure, and activities [

1,

2]. Beyond well-known phenomena like urban heat islands, local topography is a determining factor in shaping microclimates, significantly influencing specific atmospheric phenomena such as cold-air pool formation in low-lying, terrain-confined areas [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. At the local scale, climatic elements are affected by features including relief, vegetation cover, built density, surface impermeability, and proximity to water bodies [

5,

16]. These factors can create distinctive thermal patterns and microclimatic zones within a city or its surroundings.

Goldreich et al. [

17] long ago emphasized an urban-topographic climatology, i.e., the interplay between urban areas and topography in forming accumulations of cold air in valleys. Identifying locations prone to cold-air polling is important because such pools often coincide with areas of pronounced thermal discomfort and pollutant buildup. From an urban and peri-urban planning perspective, a holistic, integrated approach is needed—balancing climatic, topographic, and land-use considerations—to ensure sustainable development and mitigate adverse microclimate effects [

5,

18].

While much of the urban microclimate research has traditionally focused on urban heat islands (e.g., [

18]), it is equally important to study other processes that impact thermal comfort and public health, especially given the complex morphology of many Portuguese cities. One such process is the formation of nocturnal cold-air pools (also referred to as cold-air lakes or cold pools). These occur under stable boundary-layer conditions, typically on cold, clear nights with high atmospheric pressure, when dense cold air accumulates in topographic depressions [

3,

4,

5,

6,

8,

9,

10,

19,

20]. Cold-air pools develop due to intense radiative cooling of the land surface or downhill (katabatic) drainage of cold air, and persist in valleys that offer shelter from wind and limit turbulent mixing [

10,

12,

20,

21]. Under ideal conditions—often clear, calm winter nights—cold air gradually fills the valley, forming a pool capped by a warmer layer above, i.e., a temperature inversion [

22,

23]. The pool typically persists through the night and into the early morning, then dissipates after sunrise as solar radiation warms the surface and lower atmosphere [

4,

13,

24].

The role of gravity-driven cold-air drainage along slopes in feeding valley cold-air pools has been debated [

3,

4,

20]. Some studies suggest that katabatic flows are not the primary contributor; rather, the key is the valley’s sheltering effect that reduces turbulence and prevents warmer air intrusion, allowing rapid cooling of air near the surface [

13,

25,

26]. In many cases, the valley’s topographic enclosure is the critical factor enabling strong radiative cooling and cold-air pooling, whereas significant drainage flows may or may not occur depending on regional wind, inversion strength, surface friction, and slope gradient [

24,

26]. Nevertheless, when cold air does drain from surrounding slopes, it will collect in valley bottoms, provided external winds are weak and the terrain creates a basin to trap the air [

27,

28].

Cold-air pool formation has important implications for human thermal comfort and health, especially in settlements located in or near valley bottoms downstream of pollutant sources [

5,

6,

25]. Extremely cold air pooling at night increases the likelihood of frost and fog and can create significant cold stress for residents, requiring greater attention to building insulation and heating needs [

7,

29,

30,

31]. Moreover, a persistent temperature inversion can act as a lid that impedes vertical dispersion of pollutants, causing contaminants from vehicular traffic, residential heating, or industry to accumulate near the ground [

9,

20,

32,

33]. Studies have documented cases where pollutants (e.g., particulate matter, smoke) become trapped beneath nighttime inversions, leading to degraded air quality until the inversion breaks [

34,

35]. This is especially problematic in valleys of urban areas, where emissions are high and ventilation is poor [

31].

In this context, building on previous investigations of microclimates in the northeastern sector of Coimbra [

5,

6,

36], the present study focuses on the Eiras Valley. A common feature of these study sites is their location immediately west of the Coimbra Marginal Massif—a small mountain ridge reaching elevations over 500 m. The Eiras Valley lies just downhill of this massif, where the valley opens out onto a relatively broad alluvial plain. The main objective of this paper is to identify and understand the formation of cold-air pools in the Eiras Valley under these topographic conditions. In particular, we seek to determine when during the year such cold-air pools occur and under what atmospheric conditions, and to characterize the development of the lower atmosphere during these events—including delimiting the height of the inversion layer. By combining morphological, climatic, and urban data, this research aims to improve our understanding of urban topoclimatic dynamics and to discuss implications for urban planning in a rapidly urbanizing area, as well as for the thermal comfort and health of the local population.

2. Study Area and Geographic Context

Coimbra is situated in the center-north coastal region of Portugal, occupying a transitional zone between the Pliocene coastal platform (with relatively low elevations in the western, northern, and southern parts of the municipality) and the higher relief of the Hesperic Massif to the east. This complex geological and geomorphological setting, shaped by tectonics and Quaternary fluvial processes of the Mondego River, gives rise to distinctive local climates and landforms [

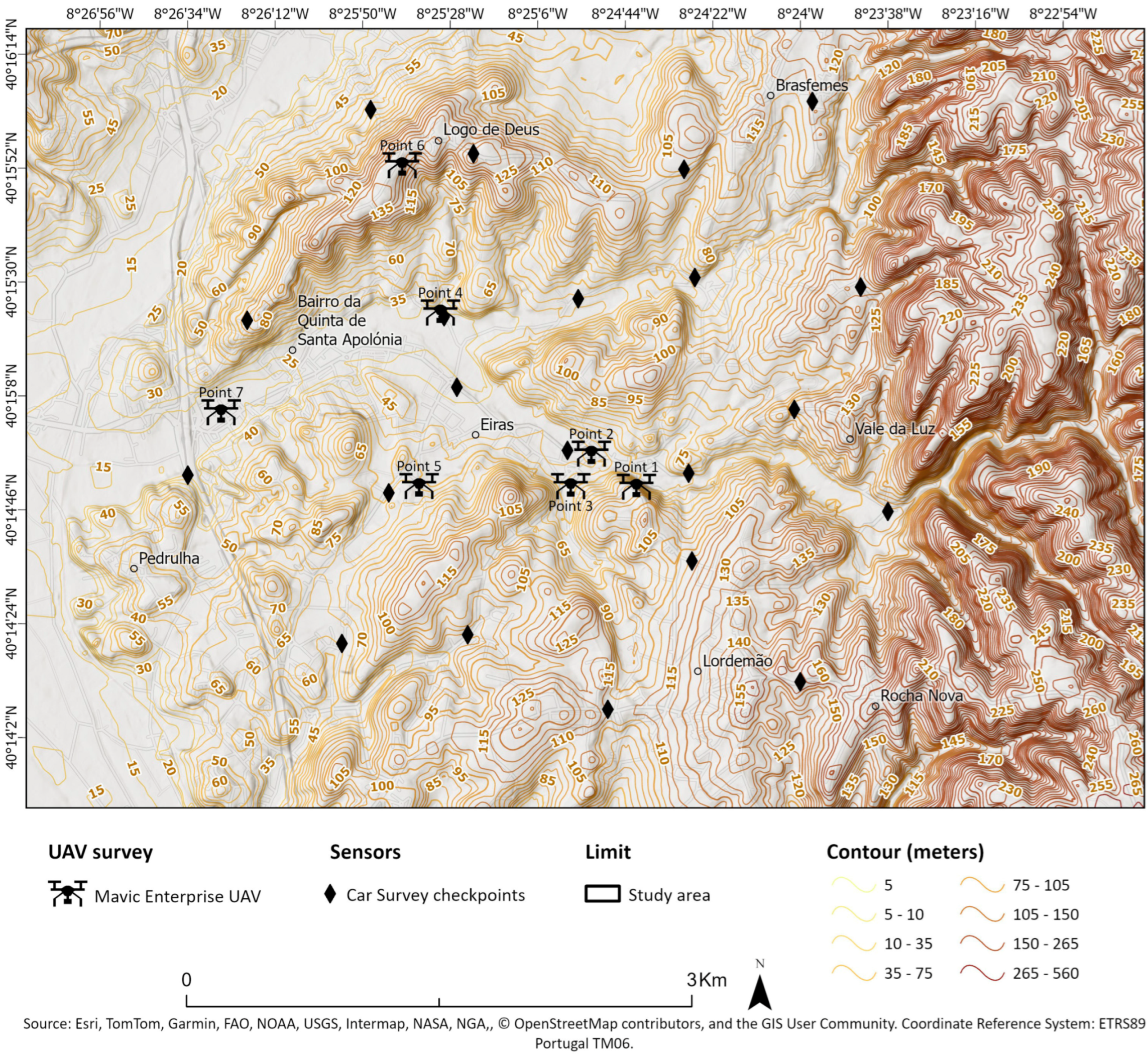

37]. The northeastern sector of Coimbra municipality, where the Eiras Valley is located (

Figure 1), is characterized by sharp terrain contrasts. Several small valleys run generally north–south along the western slope of the Coimbra Marginal Massif. The Eiras Valley is one such elongated depression, oriented roughly east–west and about 3 km in length. Valley floor elevations range from ~25 to 50 m in the central section, while the surrounding terrain rises considerably: the northern ridge (including the locality known as Logo de Deus) reaches ~100–150 m elevation, and further east, the Marginal Massif exceeds 500 m. The valley cross-section is asymmetric, with a steeper northern side and a gentler southern side.

Climatically, Coimbra experiences a Mediterranean-influenced temperate climate. It lies west of the first significant topographic barriers (the inland hills) encountered by oceanic air masses moving eastward, resulting in a climate with both maritime and Mediterranean characteristics [

38,

39,

40]. Winters are wet and mild, with an annual precipitation around 900–1000 mm and occasional incursions of cold continental air. Summers are typically dry and hot. In Köppen’s classification, the region is Csb (Mediterranean climate with dry, temperate summer). Local factors modify this baseline climate: to the east, the Coimbra Marginal Massif casts a rain shadow and influences temperature patterns, while in the central lowlands, the Mondego River and its floodplain have a moderating effect. Urban morphology in Coimbra further creates microclimatic variability [

39,

40].

Land use in the Eiras Valley (

Figure 2) reflects a mix of urban and peri-urban development. The western end of the valley (a relatively flat sector, including the southern part of the valley plain) is dominated by commercial areas and housing developments. In the eastern portion of the valley, up to the village of Eiras, land use is primarily low-density residential (single-family homes). There are also a few industrial zones, mainly logistics and commercial warehouses in Eiras and nearby Pedrulha. Notably, some older manufacturing industries persist in the area, which emit atmospheric pollutants; under cold-air pool conditions, these emissions could accumulate beneath the temperature inversion, exacerbating local pollution problems. In contrast, the steep slopes of the Coimbra Marginal Massif on the east side of the valley remain largely forested (pine and eucalyptus), owing to the terrain’s gradient and less intensive human use.

These particular climatic and morphological characteristics make the Eiras Valley an interesting case for analyzing cold-air pool formation. It is a peri-urban area experiencing strong growth, with significant daily traffic and activity due to its commercial and residential functions. The valley also hosts schools, meaning that children and young people (a vulnerable population group) are present in large numbers on a daily basis. Understanding microclimatic dynamics here is therefore important for urban planning and public health in this community.

3. Data and Methods

To investigate cold-air accumulation in the Eiras Valley, we collected empirical meteorological data within roughly the lowest 200 m of the atmosphere using complementary measurement and mapping methods. The methodology closely followed that of previous studies conducted in nearby valleys (Coselhas and Souselas) by Cordeiro et al. [

5] and Cordeiro [

6]. We employed Gemini Tinytag Plus 2 (TGP-4020, Gemini Data Loggers, UK) temperature data loggers and a DJI Mavic Enterprise dual-rotor, Unmanned Aerial Vehicle UAV (DJI Shenzen, China) as the primary instruments. The data loggers recorded air temperature at 1 min intervals with an accuracy of approximately ±0.01 °C and were used both for fixed-point near-surface measurements and for mobile (UAV-based) vertical profiling.

Surface measurements: To capture the horizontal temperature distribution along the valley, we performed a series of mobile traverse measurements at 1.5 m above ground level. A network of 21 predefined points (

Figure 3) spanning the valley (from the valley floor to the higher terrain of Logo de Deus and other surrounding slopes) was established, and a data logger was mounted on a vehicle to record temperature sequentially at each point. The vehicle stopped for ~60 s at each point to allow the sensor to stabilize, and the entire route was completed in approximately 90 min. These traverses were conducted at three times of day—early morning (08:00), mid-afternoon (15:00), and night (21:00)—in order to observe the diurnal evolution of temperatures. To examine cold-air pooling under contrasting seasonal conditions, measurements were taken on a cold winter day (14 December 2023) and a warm summer day (4 June 2024), both under anticyclonic weather (clear skies and weak pressure gradient). An additional winter survey was carried out on 11 January 2024 under cloudy, unsettled conditions (with intermittent light rain) to test how cloud cover might inhibit cold-air pool formation. After each field campaign, the temperature data were interpolated to produce continuous thermal maps of the valley. We used Empirical Bayesian Kriging (EBK) in ArcGIS Pro 3.4 (Esri) to generate these maps, a geostatistical method that has been shown to perform well for environmental variables mapping [

41]. The output was a set of georeferenced temperature maps for each time period and date, providing a spatial visualization of cold-air accumulation (if present) across the valley.

UAV-based vertical profiling: To investigate the vertical structure of the cold-air pool and identify the height of the inversion layer, we conducted UAV flights carrying a temperature logger. The logger was attached to the drone approximately 10 m below the rotors to minimize any thermal or turbulence interference from the UAV’s operation. For each profile, the UAV ascended to an altitude of about 200–250 m above the valley floor and then descended at a constant rate of ~1 m/s, while the sensor recorded temperature every second. Upon reaching the maximum altitude, the UAV would hover for ~2 min before descent to ensure the sensor readings had stabilized. Seven such vertical soundings were performed in the morning of 6 March 2024, under clear and cold conditions similar to the 14 December case. The profiles were taken at strategically chosen locations throughout the valley: several within the valley bottom (including near the downstream end of the valley and the wider mid-valley sector), and others on or near the higher terrain (e.g., on the northern ridge at Logo de Deus). This sampling design captures temperature stratification both inside the cold-air pool and at the valley edges. All UAV profiles on 6 March were conducted around 08:00 (just before sunrise) to capture the cold-air pool at its fullest extent, and prior to significant solar heating of the surface. Wind speed and direction data were also recorded during these UAV soundings (using the UAV’s on-board sensors and flight telemetry), enabling an assessment of atmospheric stability and flow within and above the cold-air pool.

During the winter field campaigns, both surface traverses and UAV profiles were carried out (in December 2023 and March 2024, respectively). In the summer (June 2024) and the additional cloudy winter case (January 2024), only surface measurements were performed (no UAV flights). All temperature data were quality-checked and time-synchronized. The weather conditions on the measurement days were documented with synoptic charts and local observations to contextualize the data. Below, we first describe the atmospheric conditions on the survey dates, followed by the results of the temperature measurements and analyses.

Time synchronization and temporal correction of measurements: All Tinytag Plus 2 data loggers used in this study were time-synchronized prior to deployment using a common reference clock. This ensured internal consistency between fixed-point, mobile traverse, and UAV-based measurements.

For the mobile traverse surveys, temperature data were temporally corrected to account for the sequential nature of the measurements. Each traverse was completed within approximately 90 min, and temperatures recorded at individual points were adjusted to a common reference time using a linear interpolation approach, assuming gradual atmospheric evolution during stable conditions. This method is widely used in urban and topoclimatic field studies where fully simultaneous measurements are not feasible.

For the UAV-based vertical profiles, the ascent and descent were conducted at a controlled and constant rate of approximately 1 m s−1. Temperature records were aligned with altitude using synchronized timestamps and flight telemetry data. Hovering periods of approximately two minutes at maximum altitude were included to allow sensor stabilization. This procedure ensured reliable vertical temperature gradients and minimized dynamic or sensor-lag effects.

4. Results

4.1. Atmospheric Conditions During the Campaigns

To understand the background conditions for cold-air pool formation, synoptic weather charts for each survey date were examined. The winter clear-sky case (14 December 2023) and the summer case (4 June 2024) both occurred under a high-pressure system centered between the Azores archipelago and the Iberian Peninsula. In the winter situation, this anticyclonic regime produced ideal conditions for nocturnal cold-air pooling: clear skies, very low overnight temperatures, and light winds. In summer, although a similar high-pressure pattern prevailed, the much warmer air temperatures significantly reduced the likelihood of cold-air pool formation. For operational reasons, the UAV-based vertical profiles could not be taken on 14 December; instead, they were conducted on 06 March 2024 under comparable winter anticyclonic conditions (with clear skies and cold pre-dawn temperatures).

In contrast, the cloudy winter case (11 January 2024) was influenced by more variable weather. During that month, weather alternated between frontal passages (Atlantic depressions) and transient ridges of high pressure. On 11 January, the morning was overcast with light precipitation (drizzle), associated with a weak frontal system, whereas by afternoon, the weather had improved to partly clear skies with no rainfall. This mix of cloud cover and rain followed by partial clearing provided a test of cold-air pool formation under non-ideal (i.e., not fully stable) conditions.

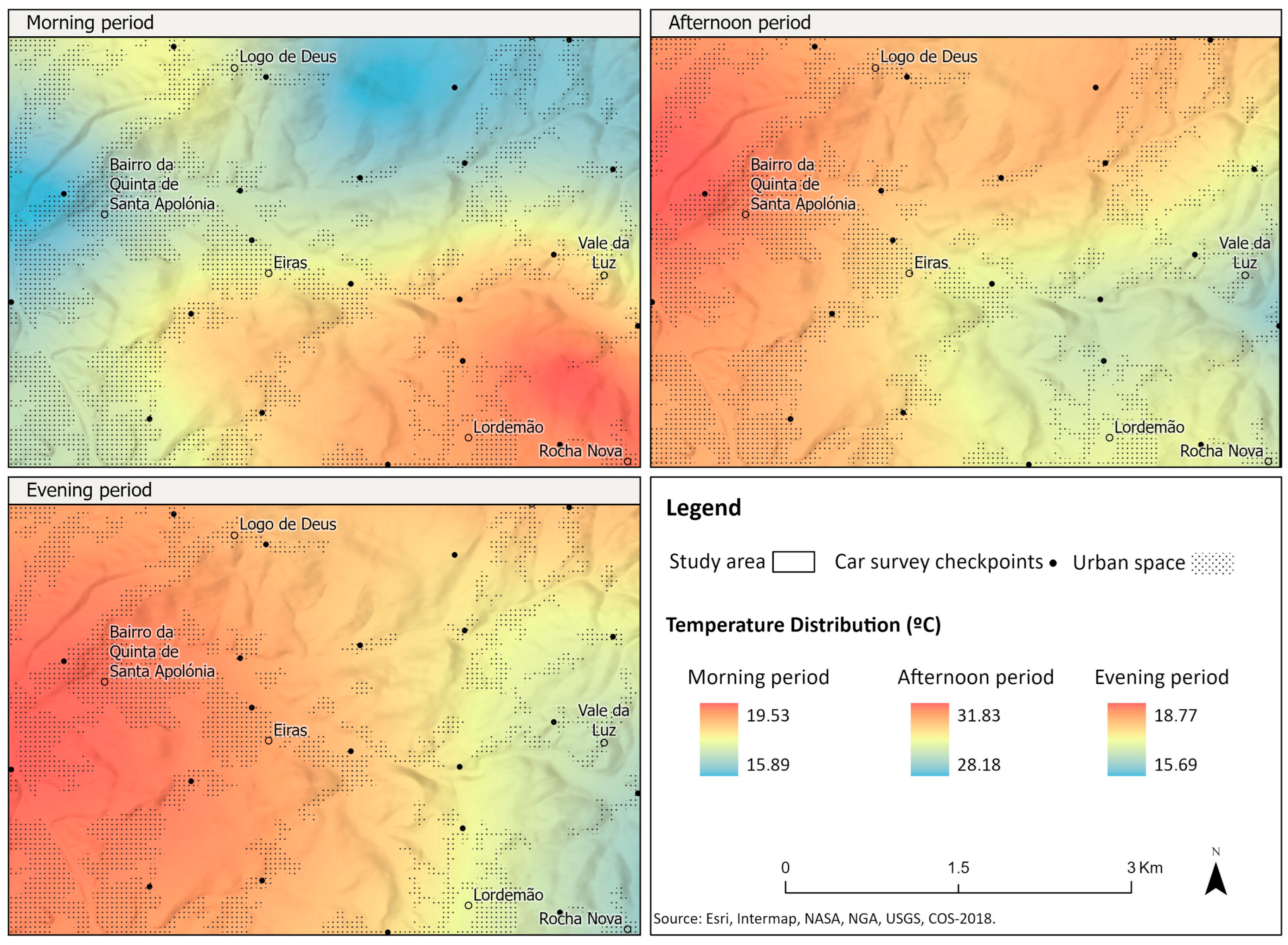

4.2. Cold-Air Pool Formation Under Winter Clear-Sky Conditions (14 December 2023; Figure 4)

Morning (08:00): The mobile traverse measurements on the winter morning revealed a well-developed cold-air pool occupying the entire valley depression. Air temperatures at 08:00 were markedly stratified by elevation: the higher points (e.g., on the northern ridge at Logo de Deus) recorded around 6 °C, while the lowest points along the valley bottom were near 3 °C. This ~3 °C thermal difference across the vertical relief of the valley indicates the presence of a temperature inversion. Spatially, the coldest air was found in the central and western parts of the Eiras Valley, aligning with the valley’s east–west orientation. The coldest spots corresponded to locations with greater shelter from airflow, suggesting that the valley’s topography protects the valley floor from mixing with warmer ambient air. Both the radiative cooling of the ground and gravitational drainage of cold air from the steep surrounding slopes appear to contribute to the formation of this cold-air lake. Similar observations have been made in other valleys of the region [

5,

6]. The cold-air pool in this case forms under the specific conditions of a clear, long winter night and remains intact through the early morning, only dissipating after receiving direct sunlight. Indeed, evidence from this and other studies shows that such cold-air pools begin to form soon after sunset under calm, clear conditions, persist through the night into the first few hours after sunrise, and then vanish as solar radiation heats the surface and lower atmosphere.

Afternoon (15:00) and evening (21:00): By afternoon on 14 December, as expected, solar heating had eroded the cold-air pool. Temperatures were substantially higher overall, reflecting the daytime warming. The spatial temperature differences nearly disappeared—all measurement points ranged within <1 °C of each other, and interestingly, the valley floor was no longer the coolest area; in fact, some of the highest temperatures were recorded at the lowest elevations. This indicates that during the day, the valley air had mixed and warmed thoroughly, with no remnant of the morning inversion. Consistently clear skies maintained strong solar insolation through the day, preventing any renewed cooling until sunset. By the beginning of the night (21:00), however, the cold-air pooling process had started again. The 21:00 measurements show cooler air re-accumulating in the valley: temperatures were about 7 °C on the valley floor and ~8 °C at the ridge (Logo de Deus), indicating the initial stage of inversion development. The nascent cold-air pool was somewhat more pronounced on the north side of the valley, likely due to the sharper slope and greater shadowing on that side (the higher northern ridge cools and drains cold air downslope more effectively). These observations at 21:00 represent the early formation phase of the nocturnal cold-air pool, which would continue to intensify later in the night under sustained radiative cooling.

Figure 4.

Spatial distribution of near-surface air temperatures in the Eiras Valley on 14 December 2023, based on mobile traverse measurements during the morning (08:00), afternoon (15:00), and evening (21:00) periods (local time). Cooler colors indicate lower temperatures, highlighting the cold-air pool in the valley during the morning and its dissipation by the afternoon.

Figure 4.

Spatial distribution of near-surface air temperatures in the Eiras Valley on 14 December 2023, based on mobile traverse measurements during the morning (08:00), afternoon (15:00), and evening (21:00) periods (local time). Cooler colors indicate lower temperatures, highlighting the cold-air pool in the valley during the morning and its dissipation by the afternoon.

4.3. Thermal Patterns Under Winter Cloudy Conditions (11 January 2024; Figure 5)

This survey was conducted to assess whether a cold-air pool would form under sub-optimal conditions (cloud cover and light precipitation) despite relatively low winter temperatures. In the morning of 11 January (08:00), the highest temperatures were observed in areas receiving the most sunlight (the western sector of the valley, which had some breaks in cloud by morning), whereas the eastern, more shadowed areas were cooler. However, in contrast to the clear-sky case, a defined cold-air pool did not establish in the valley during this cloudy morning. The presence of cloud cover overnight acted like a blanket, trapping heat and keeping near-surface temperatures from dropping as sharply. As reported in the literature, significant cloudiness and even slight precipitation tend to prevent or disrupt cold-air pool formation by limiting radiative cooling (e.g., by downward longwave radiation from clouds) and mixing the air. Thus, the valley atmosphere on this morning remained comparatively warm and weakly stratified, inhibiting the development of an inversion.

By the afternoon of 11 January, temperatures across the valley ranged roughly at 11–13 °C and were uniform spatially. The continued absence of a cold-air pool was expected, given that by day the clouds had partially cleared, allowing sunshine to warm the ground and promote convective mixing. Only minor temperature variations were seen, reflecting local differences in solar exposure, but overall, the valley experienced homogeneous warming similar to the clear-day scenario.

During the evening (21:00), conditions had changed: the sky was mostly clear after the earlier clouds had dissipated. Consequently, temperatures began to drop once the sun set. By 21:00, the valley bottom cooled to around 5 °C while the higher area at Logo de Deus remained about 8 °C. This ~3 °C difference indicates that a cold-air pool did begin to form after nightfall, once the inhibiting effect of clouds and rain was gone. Essentially, the initial cloudy conditions delayed the onset of cooling and pooling, but as the night became clear, the valley started behaving like the typical winter case with cold air accumulating in the low-lying areas. The measurements from this day confirm that under overcast or mixed weather, a cold-air pool is largely absent in the morning (and afternoon), but if skies clear by night, the process of cold-air pooling will commence, albeit later and perhaps weaker than on a fully clear night.

Figure 5.

Spatial distribution of near-surface air temperatures in the Eiras Valley on 11 January 2024. Image shows morning, afternoon, and evening conditions. The data illustrates the lack of cold-air pooling during the cloudy morning/afternoon, and the beginning of cold-air accumulation by night once skies cleared.

Figure 5.

Spatial distribution of near-surface air temperatures in the Eiras Valley on 11 January 2024. Image shows morning, afternoon, and evening conditions. The data illustrates the lack of cold-air pooling during the cloudy morning/afternoon, and the beginning of cold-air accumulation by night once skies cleared.

4.4. Thermal Patterns Under Summer Conditions (4 June 2024)

It is generally assumed that cold-air pools are a winter phenomenon and do not occur during the warm summer months. To verify this assumption, a campaign was carried out on 4 June 2024, a clear and calm summer day. Measurements were taken at the same hours (08:00, 15:00, 21:00) as in the winter surveys, under anticyclonic conditions analogous to the December case (i.e., clear skies and light winds). The results confirmed expectations as

Figure 6. In the morning (08:00) of 4 June, the temperature pattern was essentially the reverse of the winter scenario: higher elevations like Logo de Deus were actually cooler than the valley floor by roughly 4 °C. For example, if the valley bottom was around 19 °C, the hilltops might have been near 15 °C. This inverse gradient occurs because overnight cooling still affects the hilltops (which radiate heat to the clear night sky), but the valley did not trap cold air to the same extent due to the much warmer air mass and possibly a slight residual breeze. By the afternoon (15:00), strong summer solar heating produced high temperatures throughout the valley, and by night (21:00) the entire area cooled relatively uniformly with no sign of an inversion or cold pocket in the valley. Both afternoon and evening spatial patterns showed only minimal temperature differences from place to place, governed by even solar heating during the day and a broad, homogeneous cooling after sunset. In summary, the 4 June campaign did not exhibit any cold-air pooling at any time. The morning differences in temperature reflected normal elevation effects (cooler at higher altitude), and the overall thermal behavior suggests that in summer, nocturnal radiative cooling was insufficient to generate a distinct cold-air lake in the valley. These observations confirm that under typical summer thermal conditions—even with clear skies—the formation of a cold-air pool in the Eiras Valley is very unlikely. The valley atmosphere remains well mixed and largely decoupled from the ground cooling that, in winter, would produce an inversion.

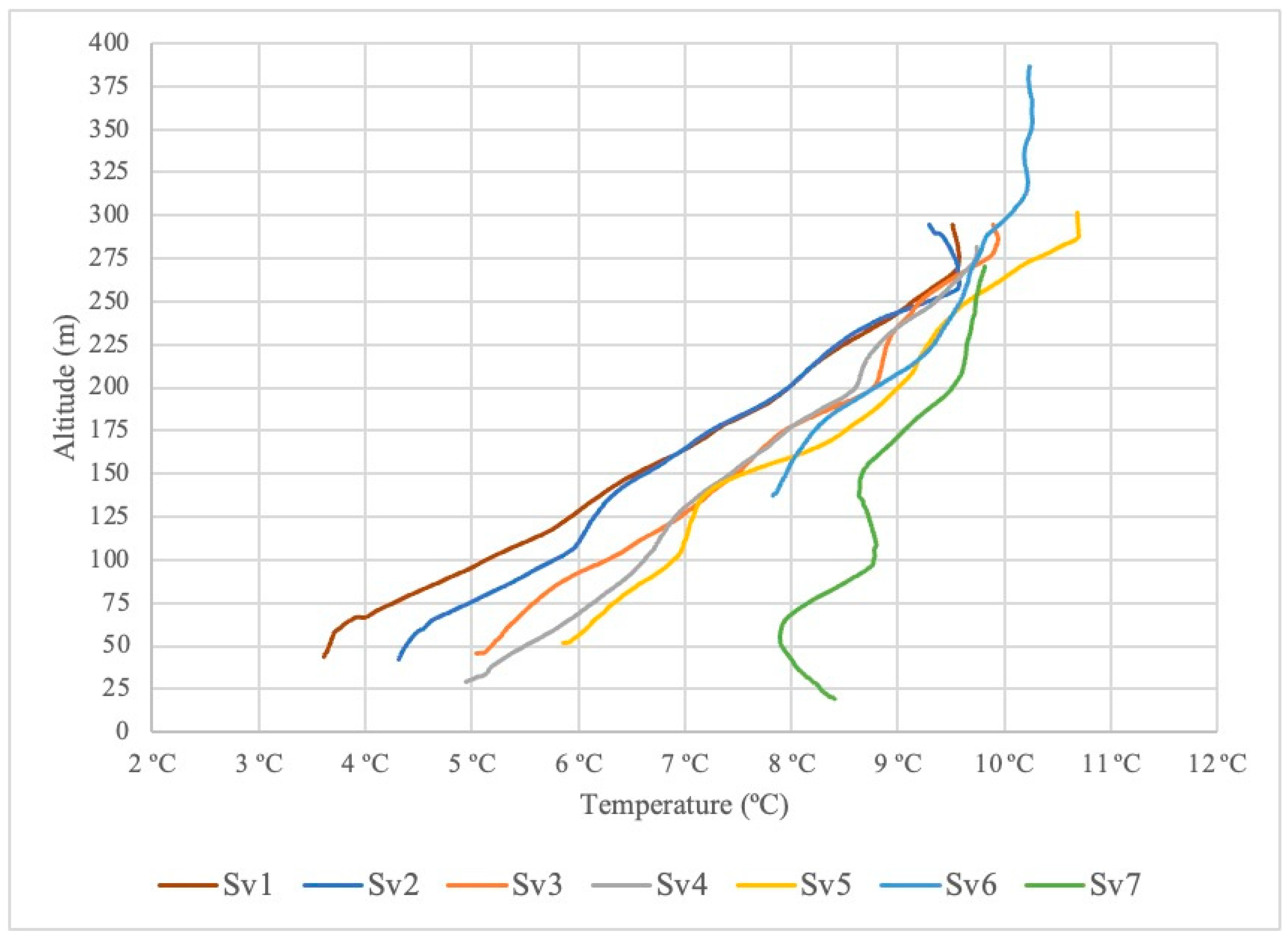

4.5. Vertical Temperature Structure in Winter (6 March 2024 Profiles)

To characterize the vertical structure of the cold-air pool, seven UAV-based temperature profiles were obtained on the clear morning of 6 March 2024 (a winter scenario). These soundings were taken at various positions along the valley, including both valley bottom locations (spanning from the narrow upstream section near the mountain to the broader mid-valley, and one near the valley’s downstream end) and one location on the higher northern ridge (Logo de Deus). Analysis of the temperature–height profiles highlights several key features of the cold-air pool and the capping inversion:

Valley floor temperature increases with height: The profiles collected in the valley bottom (all profiles except Sv6 and Sv7) showed a very uniform pattern: temperature increases with altitude from the surface up to roughly 275 m above sea level. In other words, the coldest air is at ground level in the valley and it warms with height, which is the hallmark of a temperature inversion. This trend continued until about the 275 m level, above which the profiles began to cool with further height, indicating the top of the inversion layer.

Ridge profile inversion height: The profile measured near Logo de Deus (Sv6), which started at an elevation of 137 m (on the slope above the valley floor), initially followed a cooling trend with ascent (since it begins within the already somewhat warmer air above the valley floor). Its temperature then leveled off and started warming higher up, indicating the inversion, but the inversion top for Sv6 was slightly higher (above 275 m) compared to the valley-floor profiles. The total temperature increase (inversion strength) in this Sv6 profile was about 2.4 °C from the bottom of the profile to the peak at the inversion layer.

Surface temperature differences along the valley: Near-surface temperatures in the lowest part of the valley (at the profile start points on the valley floor) ranged from approximately 3 °C to 6 °C in the early morning. Notably, these temperatures were slightly higher in the upstream (eastern) section of the valley compared to further downstream. This suggests that the coldest air pooled toward the middle or western end of the valley, with somewhat warmer (less cold) air in the upper valley—potentially due to the valley narrowing upstream or subtle terrain influences on air drainage. Aside from the one outlier profile (Sv7), temperature at the valley surface consistently increased from the downstream end toward the upstream end of the valley.

Inversion layer altitude: The temperature inversion (marked by an inflection from warming-with-height to cooling-with-height) was consistently observed at around 275 m altitude for nearly all profiles. This indicates that the top of the cold-air pool in the Eiras Valley on this morning was roughly at that height. Above 275 m, temperatures began to decrease with height, signifying a return to the “normal” lapse rate above the trapped cold air.

Anomalous profile (Sv7): One profile (Sv7), taken in the valley at a site that was measured slightly later in the morning, showed an anomalous pattern. In Sv7, the lowest ~50 m above ground showed a slight cooling with height (indicating that particular spot had already begun to warm at the surface, likely due to sunlight heating the ground, which in this case was asphalt). After that initial layer, the profile exhibited the expected inversion warming up to about 150 m, then above ~150 m, it paralleled the other profiles (cooling with further height). In essence, Sv7 captured a transitional state: the very surface had warmed (destroying the inversion right at ground level), but above 50 m, the cold-air pool structure was still present. This underscores how quickly morning solar heating can erode a shallow inversion at sun-exposed sites.

These vertical profile observations demonstrate that the cold-air pool in the Eiras Valley extended up to approximately 275 m elevation on the morning of 6 March.

Figure 7 plots the temperature profiles for all seven soundings, illustrating the inversion and the consistency among profiles (with the exceptions noted for Sv6 and Sv7). Importantly, the data confirm the presence of a pronounced temperature inversion capping the cold-air pool, which has implications for air quality as discussed below.

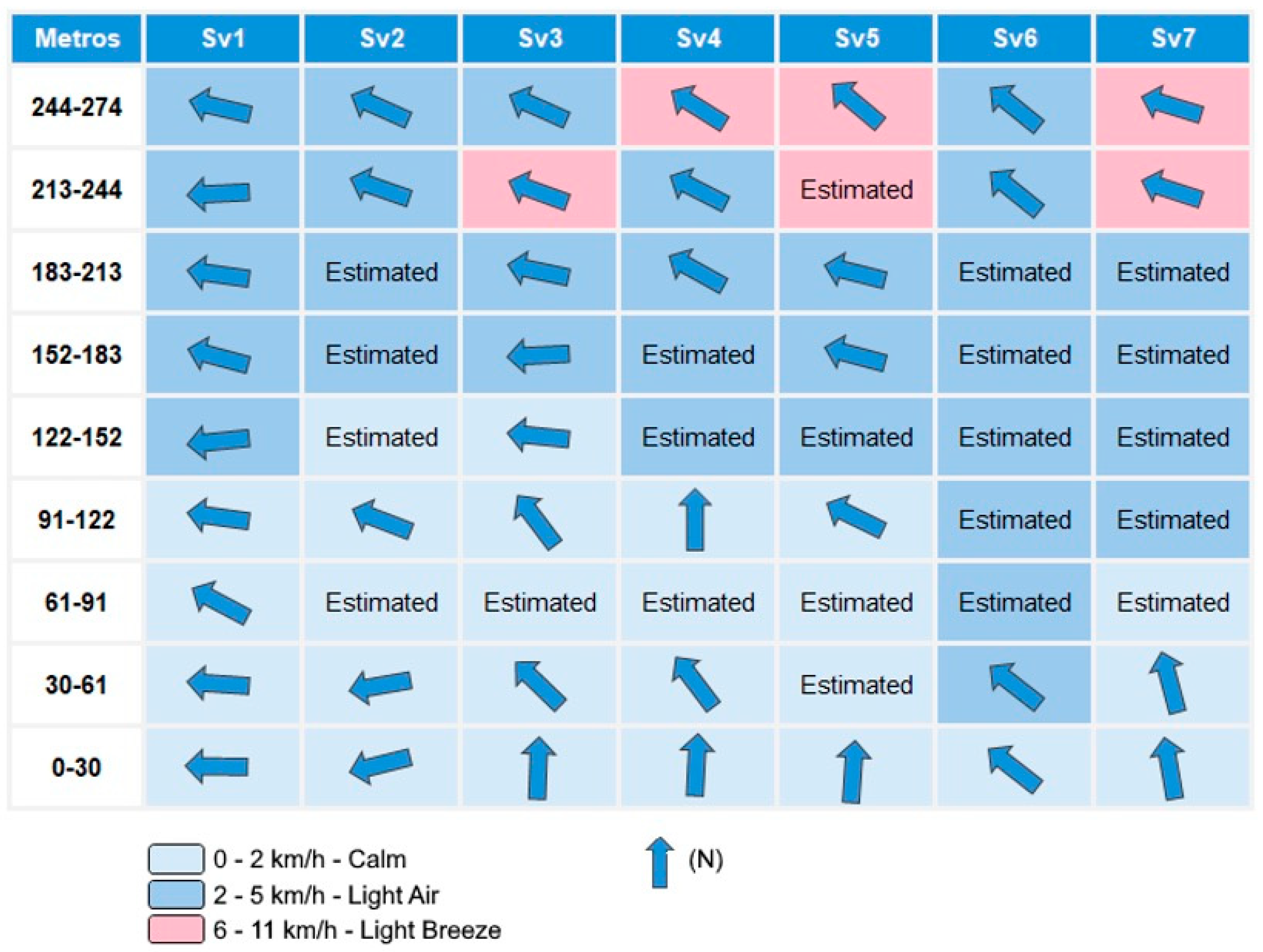

In addition to temperature, the UAV profiles provided insight into the wind field within and above the cold-air pool. Overall, the atmosphere was very stable with weak air motion during the cold-air pool event. Near the valley floor and within the pool, wind speeds were close to calm. Specifically, at the central valley sites, wind speeds from the surface up to about 180 m altitude were generally in the range of 0–2 km/h, indicating almost stagnant air in the core of the cold-air pool. In the other profile locations (including nearer the valley edges), gentle breezes of <5 km/h were observed in the low levels. Above roughly 180–200 m (near the top of the inversion), wind speeds increased slightly but remained low, not exceeding ~7 km/h at any profile’s highest levels. It is noteworthy that even at the valley outlet (profile Sv1) and at the elevated site on the ridge (Sv6), winds stayed very light (on the order of 3–4 km/h or less) throughout the layer sampled. These data indicate a very weak horizontal pressure gradient and efficient sheltering by the valley terrain during the observation period.

The wind directions during the cold-air pool conditions were predominantly from the east. This easterly flow reflects both the orientation of the Eiras Valley (which is aligned roughly E–W, so an east wind would blow along the valley axis) and the influence of the regional synoptic situation (easterly winds often occur in this region under winter high-pressure systems). The prevalence of light easterly winds suggests that any gentle drainage or background flow was channeled along the valley. There were a few exceptions to the dominant east wind in the lowest layers: for example, at some sites (profiles Sv3, Sv4, Sv5, Sv7) near the surface (up to ~60 m agl), winds with a southerly component were recorded. This could be due to very localized drainage flows off south-facing slopes or minor terrain channeling in sub-valleys. The Sv6 profile (on the northern ridge) showed a slight southeast breeze, consistent with its exposed location relative to the regional flow. Overall, however, the wind data confirms that atmospheric conditions were very stable and still, which, combined with strong radiative cooling, allowed the cold-air pool to form and persist. The valley’s topography clearly provided sheltering, reducing wind and thus limiting the mechanical breakup of the cold pool [

13]

Figure 8 summarizes the vertical profiles of wind speed and direction from the UAV measurements, highlighting the low wind speeds and gentle easterly flows.

5. Discussion

Understanding the role of valley morphology in cold-air pool formation in northern Coimbra is not only a climatological exercise but also relevant for urban planning and land-use management, given the rapid urban expansion in some peri-urban areas. Previous studies in the region examined a narrow valley [

5] and a broad tectonic depression [

6] in the vicinity of Coimbra. In the present paper, we analyzed an intermediate case: the Eiras Valley, an east–west oriented valley about 3 km long, with an asymmetric cross-section and northern flanks reaching ~140 m elevation. Despite differences in topographic scale and shape, all these valleys showed similar near-surface behavior (i.e., nighttime cooling and cold-air accumulation at the bottom), but significant differences in the vertical structure of the atmosphere above. This underscores that the general phenomenon of cold-air pooling is robust across various valley types, though the details (such as inversion height) can vary with topography.

Although the Eiras Valley is classified as a peri-urban environment, the results indicate that under winter anticyclonic conditions the local thermal structure is overwhelmingly controlled by topography rather than by classical urban heat island processes. Built surfaces, traffic, and anthropogenic heat sources may locally modulate near-surface temperatures; however, during cold-air pool events, these effects are secondary when compared to radiative cooling and terrain-induced sheltering.

The valley geometry promotes atmospheric decoupling from the regional flow, allowing cold air to accumulate efficiently at the valley floor. As a result, the typical urban tendency toward nocturnal warming is suppressed, and temperatures in the valley bottom become significantly lower than on adjacent higher terrain. This finding supports the interpretation of the Eiras Valley as a topoclimatically driven peri-urban system, where morphological controls dominate over urban thermal effects during stable winter nights.

In Eiras Valley, the cold-air pool forms in a relatively broad, gently sloping basin with floor elevations between roughly 20 and 40 m. The surrounding area is peri-urban with extensive residential and commercial development in the lower parts of the valley. We conducted measurement campaigns on four different days to verify the formation and behavior of cold-air pools under different weather conditions, addressing four key aspects:

Surface temperature mapping: Vehicle traverses provided temperature measurements at 1.5 m above ground across the valley at different times of day. Using Empirical Bayesian Kriging (EBK), we produced high-resolution maps of air temperature distribution along the valley for each survey, which clearly visualized the presence (or absence) of cold-air pools in the valley depression.

Three-dimensional profiling: By coupling temperature loggers to UAVs, we collected a series of seven vertical temperature profiles on the morning of 6 March 2024 (before sunrise, ~08:00). This allowed us to analyze the vertical dimension of the cold-air pool, identifying the inversion layer height and the temperature structure within the pool.

Climatic context variation: The study examined cold-air pool behavior under different climatic contexts—specifically comparing clear, cold winter conditions to cloudy winter conditions and to summer conditions. This approach aimed to deepen our understanding of how weather and seasonality affect cold-air pool formation and dissipation, as well as to observe the vertical structure of the pool in its fully developed state.

Topoclimatology and urban planning: We considered the implications of the cold-air pool dynamics for local planning of residential and commercial zones, especially in terms of regional wind patterns and local climatic effects on the population. This includes understanding how valley topography can exacerbate or mitigate climatic discomfort and pollution exposure for residents and commuters, information that is valuable for urban design and public health strategies.

The measurement campaigns under different atmospheric conditions yielded distinct outcomes regarding cold-air pool formation. During the winter clear-sky campaign (14 December 2023), a pronounced cold-air pool was observed in the valley during the morning and again in the evening/night, with the valley floor significantly colder than the surrounding higher terrain. By midday, solar heating destroyed the pool, as expected. These findings are consistent with the literature on stable boundary layer dynamics in valleys, confirming that cold-air pools form at night and persist into the early morning, then dissipate after sunrise due to surface warming. The presence of a ~3 °C temperature difference between the valley bottom and the plateau areas during the cold pool events in Eiras aligns with prior studies that have documented nighttime cold-air pooling in similar topographic depressions (e.g., [

14,

20]).

The other two campaigns were intentionally conducted under conditions that, according to prior research, are unfavorable for cold-air polling to empirically validate those expectations. As anticipated, no persistent cold-air pool formed during either the cloudy winter day (11 January 2024, influenced by cyclonic weather) or the summer clear day (4 June 2024). In the summer case, the much higher ambient temperatures and increased turbulence (even minimal, due to convective mixing) prevented any significant nocturnal cold pool, and in the cloudy winter case, the cloud cover and overnight drizzle kept temperatures from dropping sufficiently and introduced mixing that inhibited inversion formation. These results empirically confirm that cold-air pools in this region are primarily a feature of cold, radiative (anticyclonic) nights, and will not occur (or will be extremely weak and short-lived) under warmer or cloudy conditions. This matches broader climatological findings: strong cold-air pools tend to coincide with extended high-pressure, clear-sky periods in winter and are typically absent in disturbed or warm-weather conditions [

4,

30].

The vertical profile data collected in March 2024 offered important insights. First, the inversion layer was found at roughly 275 m altitude above the valley. This inversion height is relatively high compared to the ~150–200 m heights observed in the smaller Coselhas Valley and the broader Souselas basin in earlier studies [

5,

6]. The deeper cold-air pool in Eiras Valley could be attributed to its topographic configuration; a moderately wide valley might allow the cold pool to grow thicker than in a very narrow valley, until it reaches a point of equilibrium with the ambient conditions. Second, the valley floor profiles (except the anomalous late profile Sv7) were remarkably uniform, all showing temperature increasing with height through the depth of the pool. This indicates a well-mixed pool (in terms of being one air mass) with a consistent inversion cap. Third, near-surface temperatures in the lowest sector of the valley ranged from 3 to 6 °C among the profiles (again excluding Sv7), and notably these were always warmer upstream (toward the east) than downstream. This subtle spatial gradient within the pool could reflect drainage of the coldest air towards the lower, western end of the valley (or differences in radiative cooling rates along the valley). It illustrates that even within a single valley, micro-topographic variations can cause the cold pool to be slightly colder in some sub-areas than others.

The absence of cold-air pool formation during the summer campaign, even under clear and anticyclonic conditions, can be explained by a combination of higher background air temperatures, enhanced residual turbulence, and weak but persistent nocturnal airflow. In summer, radiative cooling after sunset is insufficient to generate a stable near-surface inversion capable of overcoming mechanical mixing within the valley atmosphere.

Although some cooling occurs at higher elevations during the night, the valley atmosphere remains relatively well mixed, preventing the accumulation of dense cold air at the valley floor. Measurements conducted at 21:00 already correspond to the early nocturnal cooling phase, and later inversion development was considered unlikely based on regional climatology and previous studies in comparable Mediterranean environments. These results confirm that cold-air pooling in the Eiras Valley is primarily a winter phenomenon linked to long nights, strong radiative losses, and very weak winds.

The wind measurements further support the interpretation that radiative cooling under calm conditions, aided by topographic sheltering, is the primary driver of the cold-air pool formation in Eiras Valley. Throughout the cold-pool events, wind speeds in the valley were extremely low—effectively near calm in the valley core and only a few km/h even at the inversion top. This quiescence is critical because stronger winds would break up the stratification or flush out the cold air. The fact that winds remained below ~3 km/h up to ~120 m agl and only reached ~7 km/h at higher altitudes demonstrates that the valley atmosphere was largely decoupled from the faster flows above. The dominant easterly wind direction observed aloft is consistent with a regional easterly flow under the high-pressure system; however, within the valley, this manifested only as a very light drift. In essence, the valley’s terrain created a microclimatic calm that allowed radiative cooling to proceed efficiently. These conditions—clear skies, long winter night, minimal wind—align perfectly with the canonical scenario for cold-air pool formation [

15,

19]. Our results reaffirm that the absence of wind (or presence of only weak, terrain-parallel breezes) and strong surface radiative cooling are indispensable for nocturnal cold-air pool development.

The vertical thermal profiles were largely consistent between different sites, indicating that the cold-air pool behaves as a coherent air mass filling the valley. Two exceptions were noted: the profile at Logo de Deus (Sv6) and the delayed profile Sv7. Sv6, taken on the higher slope, still showed an inversion but with slightly different characteristics (starting at a higher base elevation and slightly higher inversion top)—this is reasonable, as that location is at the periphery of the pool and might catch a bit of the ambient flow or have different cooling rates. Sv7’s anomaly highlighted the sensitivity of the cold pool to early morning solar heating. By the time Sv7 was measured, sunlight had warmed the immediate surface at that site, disrupting the lowest portion of the inversion. This underlines a practical point: even on clear nights, cold-air pools can begin to break up very quickly after sunrise, especially if the sun strikes the valley floor or sides, which is why profiling ideally should be done before direct sunlight reaches the valley. The identification of the inversion around 275 m was one of the main goals of this study, as it allows us to assess the impact of the cold-air pool on pollutant dispersion. An inversion acts like a lid, so knowing its height is crucial for understanding the volume within which pollutants can accumulate.

On nights when the cold-air pool formed, we indeed observed that pollutants (such as smoke from chimneys or exhaust from vehicles) became trapped below the inversion layer for extended periods the following morning.

Figure 9 provides a visual example of this phenomenon in the Eiras Valley: photographs taken on 6 March 2024 show a distinct layer of haze/fog hovering in the lower atmosphere, confined by the inversion. The smoke from residential chimneys and other particulates emitted in the valley can be seen accumulating and spreading out within the cold-air pool, rather than dispersing upward. This real-world evidence corroborates the measurement data and highlights a significant environmental health concern. While the cold-air pool persists (usually until mid-morning when the sun fully breaks the inversion), local pollutant concentrations remain elevated near the ground. This poses respiratory health risks to the population, especially vulnerable groups such as the elderly, children, or those with pre-existing conditions. In the case of Eiras, the situation can be aggravated by the presence of industrial facilities in the vicinity that emit pollutants; during stable nights, those emissions will also be trapped in the lower troposphere over the valley. Additionally, heavy automobile traffic through the area (commuters, commercial delivery vehicles, etc.) contributes to pollutant buildup during the evening and early morning hours when the inversion is in place. Thus, the cold-air pool effectively concentrates both point-source (industrial, residential heating) and mobile (traffic) pollution under the inversion “lid”. Apart from pollution, the cold-air pooling leads to very low temperatures near the ground, which, combined with high humidity, increases the likelihood of frost deposition and fog formation. These conditions, while short-lived, can impact transportation (slick roads, reduced visibility) and public health (cold stress).

Overall, our findings demonstrate how the interplay of topography and weather controls the formation of cold-air pools in a peri-urban valley and how these pools can amplify environmental challenges. In the Eiras Valley, the cold-air pool is essentially a product of the valley’s ability to radiatively cool and contain dense air under quiet conditions. When those conditions are met, the result is a pronounced stratification that has tangible effects on climate comfort (it gets much colder in the valley than surrounding areas) and air quality (pollutants concentrate). For urban planners and public authorities, this knowledge is vital. It emphasizes that valley bottoms in urban/peri-urban settings are microclimatically sensitive zones where extra care should be taken in terms of building design (insulation against cold), heating practices (to reduce emissions that would be trapped), and potentially traffic restrictions or other pollution mitigation during severe stable nights.

Figure 9 provides visual evidence of pollutant accumulation within the cold-air pool during stable winter conditions. The observed haze layer corresponds to smoke and particulate emissions from residential heating, traffic, and nearby industrial activities that become trapped beneath the temperature inversion.

During the documented event, wind speeds within the valley were near calm, with only very weak easterly flow aligned with the valley axis. As a result, plume movement was minimal and largely horizontal, preventing vertical dispersion. The low height and persistence of the haze are therefore a direct consequence of the inversion acting as an effective lid on the valley atmosphere.

Comparable summer conditions do not produce such visible accumulation, as the absence of a persistent inversion allows pollutants to disperse vertically. For this reason, summer imagery was not included, as it would not provide an equivalent or informative contrast to the winter cold-air pool situation.

6. Conclusions

This study highlights the importance of a topoclimatic approach in urban and regional planning, especially in areas with complex terrain and accelerated urban growth such as the northeastern sector of Coimbra (and specifically the Eiras Valley). Our empirical observations underscore the significant impact of topography on the formation of nocturnal cold-air pools, which in turn are primarily driven by processes of radiative cooling under stable atmospheric conditions. The cold-air pooling phenomenon in valleys can greatly influence thermal comfort, air quality, and public health in the communities residing there. In the case of the Eiras Valley, which hosts dense residential and commercial development and sensitive infrastructure like schools, these effects are particularly pertinent.

By utilizing modern monitoring techniques—high-precision data loggers and UAV-based measurements—we were able to collect detailed data both at the surface and vertically through the lower atmosphere. The results revealed marked differences between seasons and weather conditions. Cold-air pools were found to be much more intense and frequent in the winter months, when long nights, clear skies, and weak winds allow strong cooling of the valley air. Under these conditions, the valley experiences significantly lower temperatures than the adjacent terrain, and a distinct temperature inversion develops, capping the cold-air pool. During the warmer summer period, and under conditions of cloud cover or disturbed weather, no persistent cold-air pools were observed; instead, temperature patterns remained relatively homogeneous due to the lack of strong nocturnal cooling or due to mixing induced by clouds and wind.

The high-resolution thermal maps produced for the valley support the conclusion that local morphology plays a key role in spatial temperature variations. For instance, they show how the valley’s depressions accumulate cold air at night, and how even minor topographic variations can affect the pooling extent. These findings point to the need to consider micro-scale climatic dynamics in urban planning decisions. Incorporating topographic and climatic analyses (topoclimatology) into planning can help identify zones of potential discomfort or risk (such as cold-air accumulation areas or pollutant trap areas) and inform the design of mitigation measures.

From a policy and urban design perspective, our work aligns with broader sustainability and health objectives. It reinforces the goals of the United Nations Agenda 2030 and the European Urban Agenda (notably Sustainable Development Goal 11, which calls for sustainable and resilient cities and communities). In practical terms, we advocate for urban planning policies in Coimbra and similar cities that recognize valley bottoms as climate-sensitive areas. Measures could include promoting energy-efficient building practices (to reduce excess heat loss at night), controlling emissions from traffic and industry (especially during weather conditions prone to inversion), and managing urban expansion to avoid placing high-density developments in the most-affected zones without adequate mitigation. Traffic management during severe cold-air pool events and the development of green infrastructure (like strategic tree plantings which can sometimes help break up stagnation or at least absorb pollutants) are also potential strategies. Moreover, our findings call for enhanced monitoring and forecasting of cold-air pool events as part of local climate adaptation plans.

Future work should aim to expand the temporal and seasonal scope of cold-air pool monitoring in the Eiras Valley and similar peri-urban settings. This includes the deployment of permanent high-resolution temperature sensors along valley slopes and floors, repeated UAV-based profiling across different synoptic regimes, and the integration of observational data with numerical atmospheric modeling.

Additionally, coupling microclimatic measurements with air quality monitoring and health exposure data would allow a more comprehensive assessment of the environmental and societal impacts of cold-air pooling. Such approaches would improve the capacity of urban planners and public authorities to anticipate and mitigate climate-related risks in topographically complex urban areas.

In conclusion, this case study of the Eiras Valley provides a valuable contribution to understanding how topography can influence urban climate processes such as cold-air pooling. It emphasizes that even in a Mediterranean-climate city like Coimbra, with generally mild winters, microclimatic phenomena can create localized conditions comparable to much colder regions (e.g., very low night-time temperatures and air stagnation). Addressing these issues is part of building climate resilience and safeguarding quality of life. As cities seek to adapt to climate variability and change, balancing urban development with environmental considerations will be key. The insights gained here help chart a course for integrating microclimate knowledge into urban planning, ultimately aiming for a healthier and more sustainable urban environment.