Abstract

Accurate inversion of ionograms of the ionosonde is of great significance for studying ionospheric structure and radio wave propagation. Traditional inversion methods usually describe the electron density profile based on preset polynomial functions, but such functions are difficult to fully match the complex dynamic distribution characteristics of the ionosphere, especially in accurately representing special positions such as the F2 layer peak. To this end, this paper proposes an inversion model based on a Variational Autoencoder, named VSII-VAE, which realizes the mapping from ionograms to electron density profiles through an encoder–decoder structure. To enable the model to learn inversion patterns with physical significance, we introduced physical constraints into the latent variable space and the decoder, constructing a neural network inversion model that integrates data-driven approaches with physical mechanisms. Using multi-class ionograms as input and the electron density measured by Incoherent Scatter Radar as the training target, experimental results show that the electron density profiles retrieved by VSII-VAE are highly consistent with ISR observations, with errors between synthetic virtual heights and measured virtual heights generally below 5 km. On the independent test set, the model evaluation metrics reached = 0.82, RMSE = 0.14 MHz, = 0.94, outperforming the ARTIST method and verifying the effectiveness and superiority of the model inversion.

1. Introduction

The ionosphere refers to the atmospheric region that is 60 km to 1000 km above the ground, where atmospheric substances undergo partial ionization under the influence of solar radiation. The ionosphere contains a large number of free electrons, which can significantly affect the propagation of radio waves [1]. To study the impact of the ionosphere on radio wave propagation, various sounding methods have been used to monitor the ionosphere, among which vertical sounding is one of the oldest and most important ground-based sounding methods. Ionospheric vertical sounding employs a digital Ionosonde to transmit radio waves vertically upward. The radio waves of different frequencies are reflected to the ground by the ionosphere and then received by the Ionosonde [2]. By recording the propagation delay of radio waves, Ionosonde can obtain the virtual height corresponding to different frequencies, forming ionograms that reflect the relationship between virtual height and frequency. A typical ionogram displays clear trace curves, but complex structures such as diffusion or splitting may appear during ionospheric disturbances. However, vertical sounding cannot directly obtain the electron density profile that reflects the relationship between ionospheric electron density and height. We usually need to use inversion techniques on the ionogram to derive the electron density profile.

In previous studies, the inversion of vertical sounding ionograms was primarily based on the model method [3,4,5,6,7,8]. The idea of this method is as follows: it assumes that the distribution of ionospheric electron density has a certain mathematical form. Based on this assumed form, theoretical ionograms are synthesized and compared with real observed ionograms. By adjusting the model parameters to minimize the differences between the two, the optimal electron density distribution is obtained. Common model methods include: (1) the inversion method based on Chebyshev polynomials proposed by [6], which assumes that the distribution of electron density follows Chebyshev polynomials; (2) the multi-segment quasi-parabolic model method (QPS) proposed by Dyson and Bennett 1988 [7] based on the work of Croft and Hoogasian 1968 [4] and Dyson and Bennett 1988 [7], which assumes that the electron density distribution in each layer of the ionosphere follows a parabolic model; (3) the overlapping polynomial method [3,5], which treats the electron density distribution as an overlapping polynomial. The above methods have been widely applied in engineering and achieved good results. However, there are still some issues with the inversion of vertical ionograms. For example, when there are some missing or interfering frequency points in the ionogram trace, the error in the electron density profile obtained from the inversion can be quite large, making it difficult to accurately characterize the true distribution of electron density.

In recent years, deep neural networks have shown significant superiority in many fields, and they have also been applied to the solution of some inversion problems [9,10,11]. Scholars conducted some effective work in the field of ionospheric electron density inversion. For example, Smirnov et al. 2023 [12] combined multiple neural network modules to model and predict electron density in the topside ionosphere. Chen et al. 2023 [13] used deep learning to establish a global four-dimensional electron density distribution; Huang et al. 2022 [14] utilized recurrent neural networks to model global three-dimensional electron density, and Dutta and Cohen 2023 [15] used a machine learning method to simulate the electron density distribution in the topside ionosphere. Many studies also focused on the application of deep neural networks in the field of ionospheric Total Electron Content (TEC) modeling. For example, Yuan et al. 2023 [16] used a Variational Autoencoder neural network for better predictions of ionospheric TEC, and Xia et al. 2022 [17] proposed a new medium-term forecasting model for global ionospheric TEC called ED-ConvLSTM.

As a generative model, Variational Auto-Encoder (VAE) is widely applied in the field of geophysical inversion [18,19]. Traditional inversion methods rely on explicit physical models and prior assumptions, which cannot fully capture all the information in the data, while VAE provides a data-driven approach that can automatically learn the latent representations of data from a large amount of observational data. Moreover, the structure of the VAE encoder and decoder shows significant consistency with the forward modeling and inversion processes of the ionogram. Therefore, we employ a VAE to perform inversion of ionograms, following this specific workflow: First, in the encoder section, the input ionogram trace data is mapped to a latent space to obtain the corresponding electron density distribution representation. During training in the hidden variable space, we incorporate electron density profiles from Incoherent Scatter Radar (ISR) observations as labeled data to ensure that the inversion results align with actual physical observations [20]. Subsequently, the decoder reconstructs the ionogram based on the electron density profile output by the encoder. To achieve high-quality and physically consistent reconstruction results, we employ a decoder architecture that combines physical models with neural networks. Its working process is as follows: first, a theoretical ionogram is synthesized using a physical model, and then a neural network learns the residual between the ionogram synthesized by the physical model and the real ionogram. Then, the physical model synthesis result is fused with the residual to obtain a reconstructed ionogram. Finally, by minimizing the difference between the reconstructed ionogram output by the decoder and the measured ionogram, the entire network parameters are trained and optimized end-to-end.

Finally, we validated the effectiveness and superiority of the Vertical-Sounding-Ionospheric Inversion VAE (VSII-VAE) model using multiple types of ionograms recorded at the Wuhan and Hainan observation stations. The rest of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 introduces the dataset and preprocessing methods; Section 3 presents the construction and training process of the deep neural network inversion model; Section 4 provides the results and analysis of the experiments, and the conclusion is in Section 5.

2. Data

This study analyzes and inverts the electron density distribution below the peak height of the ionosphere’s F2 layer using ionogram data recorded by ionosonde. The selected observation stations include Sanya, Hainan (109.62° E, 18.35° N) and Qujing, Yunnan (25.60° N, 103.80° E). Both stations feature a 15 min temporal resolution, enabling the collection of 96 ionospheric maps per day. Regarding data acquisition, this study utilized 20 days of observation data from March to April 2015 and 16 days from April to May 2017 at the Qujing Station in Yunnan, along with 14 days in July 2023 and 7 days in August 2023 at the Sanya Station in Hainan, yielding a total of 5472 ionograms. The processing of the original ionogram data is based on automatically scaling the generated Standard Archiving Output (SAO) files, followed by a manual review of each ionogram by experienced ionogram measurement personnel, who then perform manual scaling corrections. At the same time, we trained the model using electron density profiles measured by ISR during the aforementioned time period as target data. The raw data were strictly screened to remove abnormal profiles caused by radar equipment failures or observation environment interference, and finally the valid profiles were selected for model training and inversion result verification. To evaluate model performance, the dataset was divided into a 70% training set and a 30% validation set. The final constructed dataset dimensions are (5472, N, 2), where 5472 represents the total number of samples (each ionospheric map constitutes an independent sample).

3. Theory and Methods

3.1. Basic Theory of Vertical Sounding Ionogram Inversion

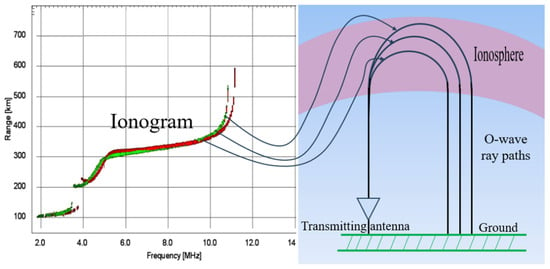

The Ionosonde transmits radio waves vertically upwards and receives the reflected signals at the same location. The reflection height can be obtained by measuring the time required for radio waves to propagate back and forth with frequency changes [21] (Scotto and Pezzopane, 2004). A schematic diagram of vertical sounding is shown in Figure 1, where the left side is the ionogram and the right side is the process of sounding by the Ionosonde. Since radio waves travel more slowly in the ionosphere than the speed of light, the reflected height obtained is not the true physical height of the ionosphere. This reflected height is called the virtual height. According to the theory of radio wave propagation, the virtual height is determined by the group refractive index of the ionosphere, which in turn is determined by the distribution of ionospheric electron density and the operating frequency. This relationship can be expressed as Equation (1):

The refractive index can be calculated using the Appleton-Hartree (A-H) formula, ex pressed as follows:

When radio waves propagate in the ionosphere, they split into O-wave and X-wave. For O-wave, the group refractive index is related to the refractive index by the equation .

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the process of vertical sounding of the ionosphere.

3.2. Selection of the Neural Network Model

VAE is a type of deep generative network based on a probabilistic graphical model, first proposed by Kingma and Welling 2022 [18]. As an unsupervised learning method, VAE inherits the basic architecture of traditional AutoEncoder neural network (AE) [22], which compresses high-dimensional input data into a low-dimensional latent space representation through an encoder, and reconstructs the original input from this latent representation through a decoder. Unlike AE, VAE not only pursues the minimization of reconstruction error but also introduces constraints on the distribution of latent variables to ensure that these variables can accurately reflect the main features of the observed data, thus enabling effective data generation.

The traditional ionogram numerical inversion process primarily consists of two steps: First, assume that the ionospheric electron density distribution follows a specific physical model (such as the Chebyshev polynomial model) and set the initial parameter values for this model. Second, based on the integral relationship between the ionogram’s virtual height and electron density, synthesize a theoretical ionogram by integrating the electron density physical model established in the first step. The theoretical ionogram is then compared with the measured ionogram. By continuously adjusting the model parameters to minimize the discrepancy between the two, the resulting electron density distribution represents the optimal inversion result. A thorough analysis of the conventional ionogram numerical inversion process reveals a high degree of similarity to the encoder and decoder functional structures of the Variational Autoencoder. Specifically, we utilize the encoder of the VAE to map ionograms to electron density, which essentially involves training the encoder to learn the distribution patterns of electron density. This process shares core logic with the first step of numerical inversion methods. The function of the VAE decoder is to reconstruct observed data, which aligns with the second step of numerical inversion methods: synthesizing theoretical ionograms through integral relations. Based on this analysis of functional similarity, we consider employing a VAE architecture to implement the inversion process for ionograms.

3.3. Construction of Network Model and Selection of Network Parameters

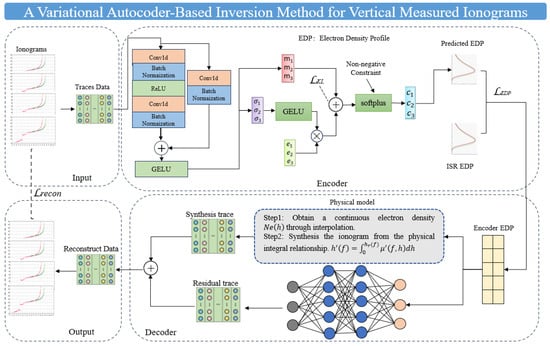

Figure 2 illustrates the schematic diagram of our designed inversion model framework, which consists of four components: The first component is the input layer, whose function is to extract frequency-virtual height data pairs from ionogram traces and thereby construct the dataset.

Figure 2.

Deep neural network inversion model framework.

The second part constitutes the encoder architecture, where we employ a ResNet network to map ionograms to electron densities. Since the VAE encoder outputs the parameter distribution of latent variables rather than concrete values, the ResNet structure provides the mean m and variance σ of these parameters. Subsequently, VAE’s resampling technique is utilized to derive the electron density values serving as latent variables. It should be noted that the encoder’s network architecture adopts the ResNet structure, while introducing the GELU activation function in the latent variable space. This ensures the smooth continuity of the electron density profiles output by the model, thereby aligning with the explicit physical characteristics of ionospheric electron density distribution. The Softplus function placed at the end of the encoder guarantees that the final output electron density profile values satisfy the non-negativity constraint. To enable the encoder to effectively learn the distribution of electron density, we compare the learned electron density with ISR observations. Electron density directly observed by ISR exhibits high reliability; using it as labeled data maximizes the encoder’s ability to learn the true distribution of electron density.

Part Three is the decoder. This study employs a hybrid decoder that integrates physical models with neural networks, operating as follows. First, based on the electron density profiles output by the encoder, a theoretical ionogram is synthesized using a physical model. Then, a lightweight neural network module is introduced to learn the residuals between the theoretical and measured ionogram, thereby correcting deviations in the physical model. This is because the physical model neglects factors such as electron collisions during the synthesis process, leading to certain errors in the results. Finally, the ionogram synthesized from the physical model is combined with the residual results corrected by the neural network to obtain the final reconstructed ionogram.

This decoder, which integrates physical models with neural networks, offers the following advantages. First, it ensures that reconstructed ionograms adhere to fundamental physical relationships, avoiding non-physical ionogram traces that may arise from purely data-driven approaches. Second, it enhances training stability. In traditional VAE, the Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence conflicts with reconstruction error. In this architecture, the decoder neural network learns only residuals, with significantly reduced parameter scale and learning complexity compared to a pure neural network generating entire ionograms from scratch. This mitigates the excessive suppression of the latent variable space by reconstruction error, alleviates the KL-Collapse problem, and enables more stable model training with faster convergence. The fourth component is the output layer, which updates the model parameters by comparing the reconstructed ionogram with the measured ionogram.

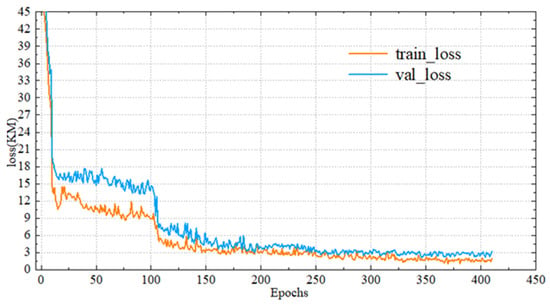

The error change curve during training is shown in Figure 3. It can be seen that with the increase in the number of training epochs, both the validation set error and the training set error show a gradual downward trend, eventually stabilizing at a flat level, indicating that the model training is effective and converged stably.

Figure 3.

Variation in training error with the number of rounds.

3.4. Loss Functions and Evaluation Metrics for Deep Neural Network Inversion Models

The loss function of the VSII-VAE inversion model consists of four components: the electron density distribution loss, the virtual height reconstruction loss, and the KL divergence loss. Specifically, it is expressed as follows:

is the true height output by the encoder at the frequency point; is the ISR observed height value corresponding to the frequency point; is the decoder’s reconstructed virtual height at frequency point ; is the observed height value at frequency point ; is the mean of the predicted height; is the variance of the predicted height, and is the corresponding empirical height value.

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the VSII-VAE model, four representative types of neural network architectures, namely Residual Network (ResNet), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), AutoEncoder neural network (AE), and Conditional Generative Adversarial Network (CGAN), were selected for comparative experiments. Meanwhile, we compare the following three aspects: (1) Root-Mean-Square Error (RMSE) of reconstructed virtual height; (2) inversion error of foF2; (3) inversion error of hmF2. The specific comparative results of model performance are presented in Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Performance of different neural networks on multiple ionogram inversion evaluation metrics.

4. Results and Analysis

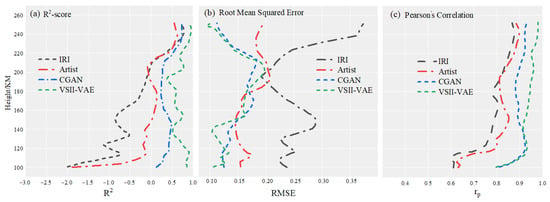

For the 1641 samples in the test set, we conducted a systematic statistical analysis of the electron density profiles inverted by the model and the ISR observations using three evaluation metrics: , , . The specific calculation process is as follows: First, select the altitude range from 100 km to 250 km, and divide the grid at intervals of 5 km, resulting in 30 altitude stratification nodes. Second, for each sample in the test set, extract the model-inverted electron density values and the ISR observations at each altitude node, and calculate the aforementioned three evaluation metrics separately at each altitude node. Finally, connect the index results of nodes at each height in sequence to obtain the variation curves of the three indices with height. Based on the above approach, we further compared the performance of the VSII-VAE model, the Automatic Real-Time Ionogram Scaler with True-height inversion (ARTIST) method, other representative neural network models such as CGAN, and the International Reference Ionosphere (IRI) model. The computational results of different methods were plotted as continuous curves, ultimately forming Figure 4a–c, to systematically evaluate the differences in inversion accuracy of each method at different ionospheric heights. The results show that the VSII-VAE model has better overall performance, with , , , significantly outperforming the IRI model and the CGAN neural network method. Although the metric results of the ARTIST method are partially comparable to those of the VSII-VAE, its performance in the F2 layer peak region and near the E layer trough area still falls short of the VSII-VAE model.

where denotes the total number of ionogram samples under a single height node; : ISR observed electron density value corresponding of the th sample; : VSII-VAE model-inverted electron density value corresponding to the th sample; is the mean of all sample true values; measures the degree of linear fit between the model’s inversion values and the true values.

Figure 4.

Analysis of Three Metrics for Different Methods on the Test Set.

RMSE is used to reflect the average magnitude of the error between the model’s inversion values and the actual values.

is used to measure the degree of linear correlation between the true value and the inversion value.

Further clarification is needed: we first uniformly grid the inverted electron density profile vertically to obtain 30 independent height nodes. Subsequently, for each height node, we separately calculate the three evaluation metrics (, RMSE, ) of the VSII-VAE model’s inversion results for the ionization pattern samples. Table 2 presents the average values of three performance metrics for different ionospheric electron density inversion models. These averages were calculated by averaging the metric results from all altitude nodes.

Table 2.

Comparison of average performance metrics for different inversion models.

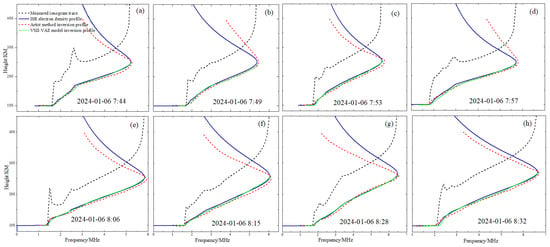

To further conduct a detailed analysis of the model’s inversion performance, we selected 30 sets of typical ionograms for in-depth validation. Figure 5 visually presents the inversion results of 8 of these sets. In Figure 5, the black dashed line represents the measured ionogram trace, the red dashed line represents the electron density profile inverted using the ARTIST method, the green solid line represents the profile inverted by the VSII-VAE model, and the blue solid line represents the ISR measured profile. By comparison, the inversion profile of the VSII-VAE model is highly consistent with the trend of the ISR measured profile. The overall fitting performance is good, fully demonstrating the effectiveness of the model’s inversion result.

Figure 5.

Inverted profiles of various types of ionogram using the VSII-VAE, and comparison with profiles obtained from other methods.

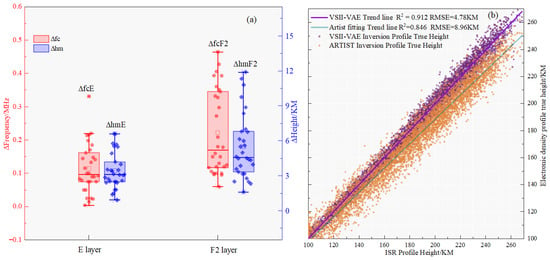

At the same time, the accurate inversion of the four characteristic parameters fcE, hmE, fcF2, hmF2 is crucial for the practical application of the electron density profile. Through statistical analysis of the inversion effectiveness of these characteristic parameters, the overall accuracy of the electron density profile can be assessed more comprehensively. Figure 6a shows the analysis results of the differences in the four key parameters between 30 sets of ionogram inversion profiles and ISR observation profiles, and we quantified the errors using box plots. The results show that the mean error of the E layer critical frequency is less than 0.1 MHz, and that of the F2 layer is less than 0.25 MHz; the mean error of the E layer peak height is less than 3 km, and that of the F2 layer is less than 6 km. All errors are within the effective range.

Figure 6.

(a) Error analysis of characteristic parameters for the selected 30 ionogram inversion profiles; (b) Comparison and error analysis of real heights between the VSII-VAE inversion profile and profiles obtained from other analysis methods.

Figure 6b further compares the consistency between the true heights corresponding to different frequencies and the ISR measured true height after inversion of 30 sets of ionograms using the VSII-VAE model and the ARTIST method, and reports the R2 and RMSE metrics for both. The data show that the VSII-VAE model has an of 0.9248 and an RMSE of 5.28 km, significantly outperforming the ARTIST method, which has an of 0.8142 and an RMSE of 8.796 km, indicating that the inversion results of the VSII-VAE model are closer to the ISR measured profile.

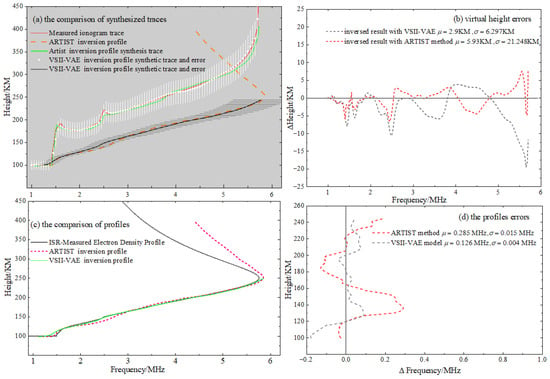

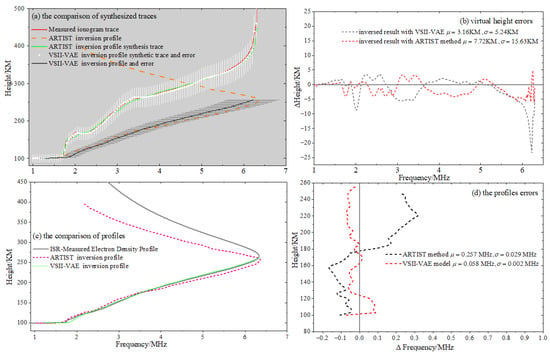

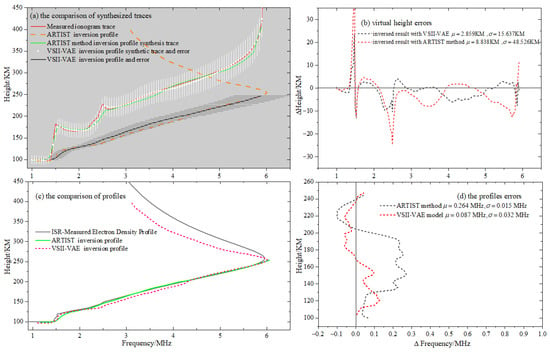

Third, in Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9, we conduct a point-by-point evaluation and analysis of the inverted electron density profiles from two core perspectives—“synthetic virtual height comparison” and “ISR profile comparison”. Figure 7a, Figure 8a and Figure 9a display the electron density profile obtained through model inversion and its corresponding probabilistic output of synthetic virtual height traces, and all key data are annotated with uncertainty intervals in the form of error bars. The black curve represents the optimal estimate of electron density output by the VAE model (i.e., the mean of the probability distribution). Formally, this black curve is similar in form to the results of traditional numerical inversion methods, but its essence is the central tendency of the posterior distribution. Additionally, the model outputs the variance of electron density at each height layer (indicated by grey horizontal lines) to quantify the uncertainty of the inversion results at that altitude: Areas with lower variance indicate more reliable inversion results, while areas with higher variance reflect greater ambiguity in the inversion process (e.g., regions with strong ionization noise, discontinuous traces). The white vertical line region indicates the optimal reconstruction result for the synthetic virtual height trace and its corresponding uncertainty range.

Figure 7.

6 January 2024, 8:02 UTC, ionogram observation and error analysis at Hainan Station.

Figure 8.

6 January 2024, 8:10 UTC, ionogram observation and error analysis at Hainan Station.

Figure 9.

6 January 2024, 8:20 UTC, ionogram observation and error analysis at Hainan Station.

Figure 7b, Figure 8b and Figure 9b shows the distribution of differences between the synthesized virtual height from the profile and the measured ionogram virtual height at different frequency points. It can be seen that the overall synthesized virtual height error for the profile inverted by the VSII-VAE model is smaller than that of the ARTIST method, and all error values are kept within a range of 5 km. Figure 7c, Figure 8c and Figure 9c visually compares the consistency between the inversion profiles from the VSII-VAE model, the inversion profiles from the ARTIST method, and the ISR measurement profiles. Figure 7d, Figure 8d and Figure 9d analyzes the differences between the electron density inversion values obtained by two methods and the ISR measured values at different altitudes. The results indicate that the differences are smaller within the 100–120 km altitude range; in the 120–150 km range, the errors tend to increase because this region corresponds to the valley layer, where inversion is more challenging; in the 230–260 km range, the errors increase again, as this region corresponds to the peak height of the F layer, where drastic electron density variations lead to higher inversion errors.

Based on the synthetic virtual height analysis from Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9 and the comparison with ISR measurements, it can be concluded that the electron density profiles inverted by the VSII-VAE model outperform those obtained using the ARTIST method and are closer to the actual distribution of ionospheric electron density.

We know that a valley region with low electron density exists between the E and F layers, creating a blind zone due to its inability to reflect radio waves. Currently, the electron density structure in this region is primarily obtained through sounding rockets and ISR observations. To enhance the model’s inversion capability for valley regions, we utilize ISR observation profiles as training labels. Since ISR profiles contain the true electron density distribution within valleys, training the model on data containing real valley information allows it to learn the physical structural characteristics of valleys. However, it must be objectively noted that achieving precise valley inversion using ISR data remains challenging. This difficulty primarily stems from significant variations in valley morphology across different latitudes, the limited coverage of ISR soundings, and the inherent complexity of model generalization.

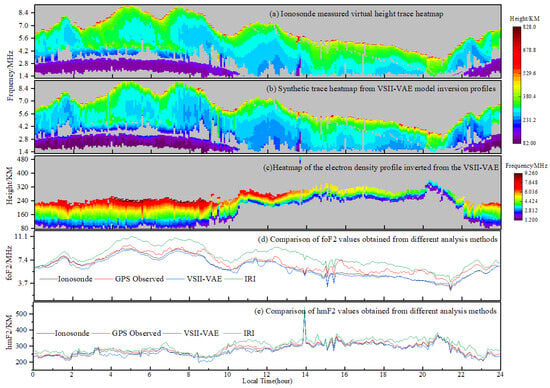

In order to further validate the performance of the VSII-VAE model on continuous sounding data, we test the inversion method using a large amount of continuous observed ionograms. Figure 10 shows the analysis results of the inversion model for the continuous observation ionogram from the Wuhan observation station on 2 June 2021. Among them, Figure 10a shows the original ionogram trace, Figure 10b shows the trace synthesized from the electron density profile obtained by the inversion model, and Figure 10c shows the electron density profile obtained through inversion. Due to the inability of the digital Ionosonde to sounding regions above the peak height of the F2 layer, Figure 10 and Figure 11 only provide the analysis results for the bottomside ionosphere (i.e., altitudes below the F-layer peak). Furthermore, to more intuitively analyze the validity of the electron density obtained from model inversion, we present the results for the key parameters foF2 and hmF2 of the electron density profiles obtained from the model inversion in Figure 10d,e and Figure 11d,e. For comparative analysis, we present the corresponding foF2 and hmF2 values derived from IRI model simulations, Global Positioning System (GPS) observations, and ionosonde measurements. Among these, the ionosonde serves as a crucial ground-based observation method for obtaining foF2 and hmF2. Its data are typically regarded as the ground truth for regional ionospheric electron density. Comparing with ionosonde data allows for direct assessment of the accuracy of model inversions. GPS represents a space-based detection method, and comparing it with GPS observation results can validate the consistency of model inversion results. As the most widely used empirical statistical ionospheric model internationally, the IRI model serves as a natural performance benchmark. By comparing results with the IRI model, the fundamental validity of model inversion results can be assessed.

Figure 10.

Analysis results of continuous observation ionograms at Wuhan Station (on 2 June 2021, LAT: 30.6, LON: 114.6).

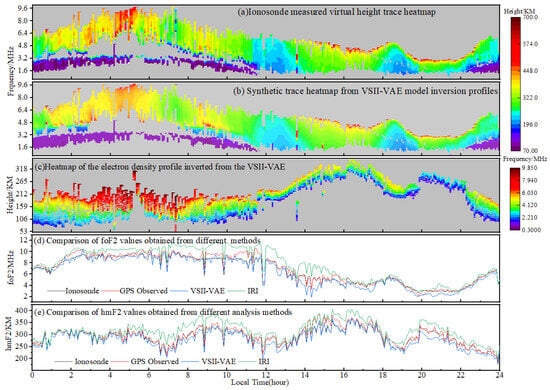

Figure 11.

Results of the analysis of the ionogram of continuous observations at Hainan Station (on 6 May 2021, LAT: 19.9, LON: 110.1).

Comparing Figure 10a,b, it can be seen that the ionograms synthesized based on the inversion profiles (Figure 10b) successfully restore the measured ionograms (Figure 10a), which indicates that the inversion profile of the VSII-VAE model can reflect the real electron density distribution more accurately. Similarly, Figure 11 shows the analysis results of the ionogram from the inversion model for the continuous observations at the Hainan observation station on 21 June 2021. Hainan is located in a low-latitude region, significantly affected by solar radiation, with dramatic variations in ionospheric electron density and a high peak in the F2 layer. As shown in Figure 11, the reconstructed ionogram traces from the inverted profiles of the VSII-VAE can fully reconstruct the measured ionogram traces between 12:00 and 22:00, demonstrating a high degree of consistency.

The results from Figure 10d,e and Figure 11d,e show that the model-inversion foF2 and hmF2 values are in good agreement with the ionosonde measurements. The foF2 and hmF2 results of the IRI model are significantly higher than those of the other three methods. This is because the IRI model, as an empirical model, inherently possesses substantial error. GPS observations also yielded slightly higher values than those from the ionosonde data and model inversion results, a phenomenon consistent with actual observational experience.

5. Conclusions

Existing ionogram inversion methods primarily rely on model-based methods, but such methods typically require explicit physical models or predefined assumptions, posing challenges for accurately characterizing electron density distributions. To address this limitation, this paper proposes a VAE-based inversion model, VSII-VAE. We validated this inversion algorithm using multiple types of ionograms recorded at various observation stations. Results demonstrate that the electron density distributions inverted by the VSII-VAE model closely match ISR measurement profiles. Furthermore, the virtual height synthesized from the model-inverted profiles exhibits good consistency with the measured virtual height. It is worth noting that the target data used for training this model consists of ISR-calibrated electron density rather than directly measured raw line-of-sight plasma density values, which introduces some error into the inversion process. In the future, this model could be trained directly using ISR-measured line-of-sight plasma density values as the target, which is expected to further enhance inversion performance. In addition, the neural network inversion model proposed in this paper ignores the effect of electron collisions. In future work, this physical factor can be integrated into the model to enhance the level of detail in the inversion results.

Author Contributions

L.N. and W.L. wrote the paper and conducted the experiments. N.W. verified the experiment. C.Z. processed the image data. Z.D. and G.H. guided the experiments and structure of the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2023YFA1009100).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original lidar data can be obtained from the Chinese Meridian Project (homepage: https://data.meridianproject.ac.cn/ (accessed on 18 October 2025)).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bilitza, D.; Pezzopane, M.; Truhlik, V.; Altadill, D.; Reinisch, B.W.; Pignalberi, A. The International Reference Ionosphere Model: A Review and Description of an Ionospheric Benchmark. Rev. Geophys. 2022, 60, e2022RG000792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, P.; Wei, N.; Guo, L.; Feng, J.; Li, X.; Yang, L. Numerical study of traveling ionosphere disturbances with vertical incidence data. Adv. Space Res. 2020, 65, 1306–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titheridge, J.E. The Overlapping-Polynomial Analysis of Ionograms. Radio Sci. 1967, 2, 1169–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croft, T.A.; Hoogasian, H. Exact Ray Calculations in a Quasi-Parabolic Ionosphere with No Magnetic Field. Radio Sci. 1968, 3, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titheridge, J.E. Single-Polynomial Analysis of Ionograms. Radio Sci. 1969, 4, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinisch, B.W.; Huang, X. Automatic Calculation of Electron Density Profiles from Digital Ionograms: 3. Processing of Bottomside Ionograms. Radio Sci. 1983, 18, 477–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, P.L.; Bennett, J.A. A Model of the Vertical Distribution of the Electron Concentration in the Ionosphere and Its Application to Oblique Propagation Studies. J. Atmos. Terr. Phys. 1988, 50, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.; Wen, L.; Zhou, C.; Deng, M. A Profile Inversion Method for Vertical Ionograms. AIP Adv. 2024, 14, 065034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Nakata, N. Geophysical Inversion versus Machine Learning in Inverse Problems. Lead. Edge 2018, 37, 894–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Alvis, J.; Laloy, E.; Nguyen, F.; Hermans, T. Deep Generative Models in Inversion: A Review and Development of a New Approach Based on a Variational Autoencoder. Comput. Geosci. 2021, 152, 104762. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Alvis, J.; Nguyen, F.; Looms, M.C.; Hermans, T. Geophysical Inversion Using a Variational Autoencoder to Model an Assembled Spatial Prior Uncertainty. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2022, 127, e2021JB022581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, A.; Shprits, Y.; Prol, F.; Lühr, H.; Berrendorf, M.; Zhelavskaya, I.; Xiong, C. A Novel Neural Network Model of Earth’s Topside Ionosphere. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; An, B.; Liao, W.; Wang, Y.; Tang, R.; Wang, J.; Deng, X. Ionospheric Electron Density Model by Electron Density Grid Deep Neural Network (EDG-DNN). Atmosphere 2023, 14, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Li, W.; Shen, X.-C.; Ma, Q.; Chu, X.; Ma, D.; Bortnik, J.; Capannolo, L.; Nishimura, Y.; Goldstein, J. Application of Recurrent Neural Network to Modeling Earth’s Global Electron Density. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2022, 127, e2022JA030695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Cohen, M.B. Topside Electron Density Modeling Using Neural Network and Empirical Model Predictions. Space Weather 2023, 21, e2023SW003501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Xia, G.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, C. Synthesis-Style Auto-Correlation-Based Transformer: A Learner on Ionospheric TEC Series Forecasting. Space Weather 2023, 21, e2023SW003472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, G.; Zhang, F.; Wang, C.; Zhou, C. ED-ConvLSTM: A Novel Global Ionospheric Total Electron Content Medium-Term Forecast Model. Space Weather 2022, 20, e2021SW002959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Welling, M. Auto-encoding variational bayes. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1312.6114. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Guan, Q.; Lin, Y. Making Invisible Visible: Data-Driven Seismic Inversion with Spatio-temporally Constrained Data Augmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 4507616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.; Wan, W.; Ning, B.; Jin, L.; Ding, F.; Zhao, B.; Zeng, L.; Ke, C.; Deng, X.; Wang, J.; et al. Development of the Sanya Incoherent Scatter Radar and Preliminary Results. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2022, 127, e2022JA030451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzopane, M.; Scotto, C. Software for the Automatic Scaling of Critical Frequency f0F2 and MUF (3000) F2 from Ionograms Applied at the Ionospheric Observatory of Gibilmanna. Ann. Geophys. 2004, 47, 1783–1790. [Google Scholar]

- Bourlard, H.; Kamp, Y. Auto-Association by Multilayer Perceptrons and Singular Value Decomposition. Biol. Cybern. 1988, 59, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.