Abstract

Open-pit coal mining is characterized by multiple pollution sources, diverse types, and extensive affected areas, leading to complex air pollution with wide diffusion. Traditional fixed monitoring methods cannot address these limitations. Taking a coal mine in Xinjiang as a case study, this study developed a drone-mounted mobile atmospheric monitoring system, focusing on nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and suspended particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10) to explore their distribution, diffusion patterns, and influencing factors. The results show distinct seasonal pollutant characteristics: NO2 and ozone (O3) dominate in summer, while particulate matter prevails in winter. The temporal distribution exhibits a bimodal pattern, with high levels in the early morning and evening hours. Spatially, higher pollutant concentrations accumulate vertically below ground level, while lower levels are observed above it. Horizontally, elevated concentrations are found along northern transport corridors; however, these levels become more uniform at greater heights. A spatiotemporal prediction model integrating convolutional neural network (CNN) and long short-term memory (LSTM) network was successfully applied to real-time pollutant prediction in open-pit coal mining areas. This study provides a reliable mobile monitoring solution for open-pit coal mine air pollution and offers valuable insights for targeted pollution control in similar mining areas.

1. Introduction

Coal plays a dominant role in the primary energy consumption structure of China, serving as a crucial component in maintaining the stable operation of the economy and society, as well as ensuring energy security [1,2,3]. Xinjiang is recognized as the region with the highest concentration of open-pit coal mines in China, housing numerous large-scale coal resource development bases. However, open-pit coal mining is characterized by multiple point sources, diverse pollutants, and exposure to open-air conditions. In general, the main component of particulate matter generated during open-pit coal mining activities is solid coal-based mineral particles, which form a complex multiphase mixture. Among them, PM2.5 and PM10 are the focus of environmental monitoring and pollution control due to their long suspension time and high inhalability. Sulfur-containing gases are produced by coal combustion or pyrite oxidation, while NOx is emitted from blasting or equipment exhaust. Trace amounts of amorphous liquid phase (in extremely low contents) are present, either encapsulating or adsorbing onto the surface of solid particles [4,5]. Additionally, Coal releases free polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) during processes such as mining, storage, and transportation. Particularly during the storage and stockpiling of coal waste residues, the thermal activity of these residues facilitates the release of PAHs into the atmosphere; with PAHs exhibiting significant genotoxic, mutagenic, and carcinogenic properties [6,7]. These pollutants can undergo chemical or photochemical reactions with inherent components in the atmosphere or other contaminants, resulting in secondary pollutants such as ozone and acid precipitation. On the other hand, the smaller the size of ambient dust particles, the larger their specific surface area, which enables them to adsorb higher concentrations of toxic and hazardous substances (e.g., polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, heavy metals, bacteria, and viruses). Moreover, these fine particles persist and accumulate in human target organs for extended periods, triggering chronic inflammation and subsequently inducing genotoxic effects such as DNA damage and gene mutations [8]. Such processes pose serious threats to both ecological systems and human health [9,10,11]. Therefore, accurate monitoring of real-time pollutant concentrations is essential for estimating the exposure of mine workers at different work locations [12].

Air pollution diffusion is a complex environmental process influenced by meteorological factors, topographical and geomorphological factors, and other variables. Under different meteorological conditions, the pollutant concentrations generated by the same emission sources vary extremely significantly [13]. After pollutants are discharged into the atmosphere, wind can transport them, and the air mixed in during the transport process dilutes them, thereby achieving the diffusion, dilution, and transmission of pollutants. The vertical distribution of air temperature affects the intensity of turbulent activities, which, in turn, influences the dispersion of air pollutants. The vertical temperature distribution in the lower layer is usually a nocturnal inversion, and a diurnal lapse and superadiabatic lapse rate may occur in the afternoon; near the ground, isothermal processes may appear around sunrise and sunset. When the air layer is in an unstable structure, it promotes the development of turbulent motion and enhances diffusion capacity; on the contrary, it inhibits turbulent motion and weakens diffusion capacity, especially in the presence of an inversion layer, which significantly suppresses pollutant diffusion [14,15]. Complex and variable topographies and geomorphologies exert dynamic and thermodynamic effects on air flow trajectories and meteorological conditions, thereby altering the transmission and diffusion patterns of air pollutants. Due to mining activities in open-pit coal mines, the stope and dump form mountain-like topographical characteristics, which are prone to forming atmospheric circulation and local circulation. Additionally, they are more likely to develop inversion layers with stronger inversion effects, further weakening pollutant diffusion [16].

In recent years, advancements in unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) remote sensing and high-precision sensors have significantly enhanced the spatial and temporal resolution of air quality monitoring in mining areas [17,18,19]. Compared with traditional measurement methods, UAVs provide increased safety, reduced costs, and improved efficiency, making them particularly suitable for high-risk mining applications [20,21,22]. Bui et al. [23] deployed sensors on a UAV to monitor environmental variables, including CO, CO2, and NOₓ, within coal mine pits. Their findings demonstrated that low-cost UAVs are well-suited for three-dimensional mapping and air quality monitoring in large, deep pits, achieving relatively high accuracy. Penchala et al. [12] deployed low-cost particulate matter sensors in a large open-pit mine, found that particulate matter concentrations exhibit an exponential distribution with depth attenuation, and predicted the particulate matter concentrations escaping the mine pit boundary. Furthermore, integrating advanced machine learning methods with unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) monitoring systems can further improve the accuracy of predicting the evolutionary trends of pollutants. Guo et al. [24] mounted a micro-detector on a UAV to acquire high-spatiotemporal-resolution PM2.5 data, systematically elucidating its vertical distribution and diffusion characteristics. The study provides valuable information for subsequent deep learning model development and pollutant concentration prediction. Moreover, high-precision forecasting of future atmospheric pollutant concentrations can provide environmental management authorities with scientifically grounded early warnings. This capability enhances the proactivity of air pollution prevention and control efforts and offers theoretical support for the development of targeted governance strategies, optimization of resource allocation, and mitigation of environmental and health risks [25,26,27].

With the increasing focus on the sustainable development of ecological civilization construction, accurate prediction of air pollution based on environmental monitoring data has become increasingly important. Modeling the complex relationships among these variables using advanced machine learning methods has emerged as a highly promising research field [28]. Taamté et al. [29] integrated intelligent multi-sensor modules, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), and ZigBee wireless transmission technology for air quality monitoring in industrial zones and large densely populated cities, providing a feasible solution to address the limitations of fixed monitoring stations in measurements. Augello et al. [30] proposed a UAV path optimization method suitable for air quality monitoring based on the multi-objective genetic algorithm and via numerical simulations conducted on synthetic data and real Air Quality Index (AQI) data of multiple pollutants. This method can dynamically adjust flight routes according to environmental variables such as wind speed changes and precipitation. Researchers [31,32,33,34] explored the spatiotemporal prediction of atmospheric pollutant concentrations, evaluating the performance of various deep learning models. Their findings indicated that enhancements to the long short-term memory (LSTM) method significantly improve prediction accuracy. Ketu [35] developed a predictive model using an LSTM network that incorporated factors such as wind direction and wind speed to accurately analyze their temporal and spatial effects on PM2.5 concentration variations in surrounding areas, ultimately achieving effective and precise predictions of PM2.5 levels. However, these forecasting methods still exhibit limitations in terms of temporal continuity and fitting accuracy.

Tracking work faces significant challenges due to the uncertain movement characteristics of air pollutants. The integration of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and long short-term memory (LSTM) provides a feasible solution for achieving an air quality monitoring mode with high temporal resolution [36]. Kim et al. [37] developed a deep hybrid neural network model combining a convolutional neural network (CNN) and long short-term memory (LSTM) for air quality prediction. They indirectly explored the importance of input features by sequentially perturbing input variables. The results showed that compared with the three-dimensional chemical transport model (3D CTM), the errors and biases of the newly developed hybrid model in predicting the ambient concentration of PM2.5 were 1.51 times and 6.46 times smaller than those of the 3D CTM simulation results, respectively. Similarly, Gilik et al. developed a supervised air pollution prediction model [28]. By tuning the model’s hyperparameters, they identified the architecture that achieved the lowest test error, leading to a significant improvement in the prediction performance for various pollutants.

In this study, a micro-detector mounted on an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) was employed to collect data on various atmospheric pollutants in an open-pit coal mine. The primary components of the pollutants were analyzed, and the spatiotemporal distribution patterns of these pollutants were explored, revealing the impact of environmental changes within the coal mine on pollutant concentrations and diffusion patterns. Additionally, based on the CNN-LSTM model, the concentrations of air pollutants in open-pit coal mines were predicted. This work provides a reliable data collection method and an accurate prediction tool for the characterization and prediction of air pollution in open-pit coal mines, offering important technical support to the precise prevention, control, and management decision-making of air pollution in such mines.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Setup

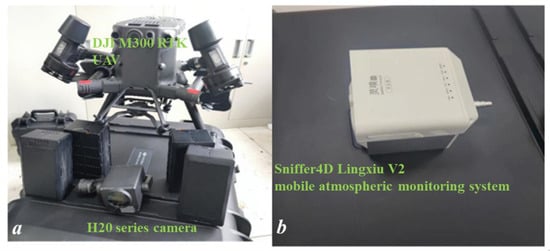

The UAV platform used in this study was the M300 RTK multi-rotor UAV (SZ DJI Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China), equipped with a DJI H20 series camera (SZ DJI Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China). The specific details of image acquisition can be found in Appendix A. With a maximum payload of 2.7 kg and excellent wind resistance, it can fly stably under wind speeds of up to 12 m/s. It offers a maximum image and data transmission range of 15 km and a flight endurance of up to 55 min per mission, which is sufficient to meet the data collection requirements. The mounted air quality monitoring device was the Sniffer4D Lingxiu V2 mobile atmospheric monitoring system by Kefei Technology (Jiaxing, China). Its lightweight design makes it well suited for UAV platforms. It features an active air intake system delivering an airflow rate of approximately 5 L/min under zero pressure difference. It is integrated with the DJI UAV system via the PSDK interface, allowing real-time concentration data to be displayed directly in the software application. The Sniffer4D Lingxiu V2 atmospheric mobile monitoring system is equipped with an automatic calibration function. Each detection module has a built-in dedicated data processing chip that can independently store calibration parameters. Simply place the device in an area with fresh air, power it on, and let it stand for 10 min before putting it into use for detection. Prior to deployment, a small-scale test should be conducted using the supporting Sniffer4D V2 Mapper software to verify whether the device’s signal transmission and detection functions are normal, ensuring stable operation after deployment. The average error of data from long-term comparison with scientific-grade air monitoring stations is within ±10%, with the long-term data correlation (R2) ranging from 0.81 to 0.95. Among these, the measurement error of gaseous pollutants can be controlled within ±5%, that of particulate matter within ±10%, and the module repeatability is less than 4% FS. The detection limit for inhalable particulate matter is 1 μg/m3, and the detection limit for NO2 and O3 is 5 ppb. The data acquisition setup is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the experimental system: (a) UAV; (b) Sniffer4D Lingxiu V2 mobile atmospheric monitoring system.

2.2. Measurement Method

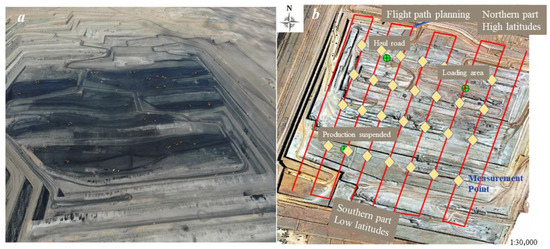

The open-pit coal mine measures 1.24 km from east to west and 1.5 km from north to south. Most of the mine is 30–50 m deep, and it reaches a maximum depth of approximately 60 m. The main route planning and sampling point locations are shown in Figure 2. During operation, the UAV flies at the same height as the top of the open-pit stope. In the horizontal direction, there are 28 measurement points in total, while a maximum of 7 measurement points are set along the vertical direction of the sampling pit. Each measurement point is sampled continuously three times, and each task execution lasts 45 to 50 min, depending on the different research objectives. Specifically, the monitoring of different heights in the sampling pit was conducted, focusing on elevations at 50 m below the pit, 30 m below the pit, at the top of the pit, and 50 m, 100 m, 150 m, and 200 m above it. The corresponding absolute altitudes are 515 m, 535 m, 565 m, 615 m, 665 m, 715 m, and 765 m, respectively. When reaching the target location, the UAV first hovers before descending to 50 m below ground level and then ascends slowly. Subsequently, the UAV proceeds along the preplanned flight path to the next sampling point at a speed maintained between 7 and 10 m/s.

Figure 2.

Open-pit coal mining and route distribution: (a) topography; (b) measurement points.

2.3. Measurement Principle

During monitoring, the concentrations of PM2.5 and PM10 were determined using laser (light) scattering technology. Specifically, a linear relationship exists between the mass concentration of particulate matter and the scattered light flux measured with the photometer. As the light beam traverses the particle-laden air, light scattering constitutes the dominant mechanism of light energy attenuation for particles whose dimensions are comparable to or exceed the wavelength of the incident light. Assuming constant particle properties, the mass concentration of particulate matter can be determined by measuring the intensity of scattered light. During field operations, airborne particles are drawn into the detector by a sampling pump and transported to the detection chamber via the airflow. Within the chamber, the particles are irradiated by a laser source, which induces light scattering. By quantifying the magnitude and intensity of this scattered light, the optical signal is converted into an electrical signal proportional to the particulate matter concentration. The embedded processor then computes the particle concentration based on this electrical signal.

Electrochemical detection is employed to measure the concentrations of NO2, O3, CO, and SO2, leveraging the electrochemical activity of these gases, which allows them to be oxidized or reduced via electrochemical reactions. A current signal proportional to the gas concentration is generated during the reaction process, and the concentration value of the corresponding gas can be converted by collecting and calibrating this current signal. The electrochemical detection device employs a three-electrode system, comprising a working electrode, a counter electrode, and a reference electrode. The working electrode is the primary site at which redox reactions of gases such as NO2 occur, the counter electrode serves to balance the reaction current at the working electrode, and the reference electrode provides a stable potential reference for the system. For example, as NO2 and other gases reach the surface of the working electrode through the diffusion hole, the following electrochemical reactions occur:

The current generated during these reactions exhibits a linear relationship with the concentration of NO2. By amplifying and converting the current signal, the concentration of NO2 can be precisely determined.

2.4. CNN-LSTM Model

2.4.1. Model Description

Accurately predicting the concentration of atmospheric pollutants is crucial for developing effective pollution control strategies and enhancing air quality warning and prevention capabilities. Based on atmospheric diffusion theory and meteorological principles, a common method for predicting post-diffusion concentrations involves utilizing diffusion formulas in conjunction with diffusion factors. However, this approach entails complex calculations and substantial computational demands. Therefore, it is essential to optimize artificial intelligence algorithm models to streamline the process of pollutant concentration prediction and improve forecasting accuracy.

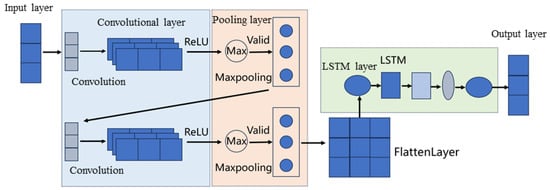

The CNN-LSTM architecture is a hybrid model that integrates convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, designed to process spatiotemporal sequence data, such as air quality time series monitoring, video analysis, and meteorological forecasting. This model leverages CNNs to extract spatial features from the input data while connecting LSTM layers at the output of the CNNs to further explore contextual information within the sequential data. This combination effectively captures semantic association features between images and text, thereby enhancing the expressiveness and performance of the model. Simultaneously, LSTM networks are adept at capturing dynamic patterns in time series data, allowing for effective modeling of complex nonlinear relationships in spatiotemporal contexts. The structure of the CNN-LSTM network model built in this study is illustrated in Figure 3, wherein a flatten layer is employed to prepare the data for normal operation within the LSTM layer. Other components and their functions remain consistent with those found in standard CNN and LSTM architectures.

Figure 3.

CNN-LSTM network model structure diagram.

2.4.2. Training Process

Comparative experiments were conducted with both CNN and LSTM models under identical training parameter settings to validate the accuracy of predictions made by the CNN-LSTM model on time series data. The training parameters were configured as follows:

An Adam optimization strategy was employed, with a maximum of 800 training iterations. The initial learning rate was set at 0.005, and the learning rate decay factor was 0.1, adjusting the learning rate once every 600 epochs. To enhance the clarity and reliability of the comparative results, no data shuffling was performed during training. The performance of different models was analyzed using RMSE (root mean square error) as a metric, with its calculation formula provided in Equation (3).

where Yi represents the predicted values, Ti denotes the true values, and n indicates the number of samples. The unit of RMSE is consistent with that of the original data, which enhances the intuitiveness and comprehensibility of error measurement. Given that RMSE involves squaring errors during its calculation process, it exhibits increased sensitivity to larger errors. This characteristic implies that significant discrepancies in model predictions are more pronounced in RMSE values, facilitating the identification and correction of forecasts that result in substantial errors.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Pollutant Main Components

Because of its widespread sources and the significant harm it causes to both the ecological environment and workers, dust has become a primary focus of air pollution research in open-pit coal mines. In addition to dust, open-pit coal mining operations generate other pollutants, such as NOx, during production processes. As shown in Table 1, monitoring data for major pollutants and their concentrations were collected for both summer and winter seasons. The concentration data presented in the table represent average values measured from 10:00 AM to 7:00 PM. In the assessment of concentration limit values for the Air Quality Index (AQI), a daily report standard is employed, specifically utilizing 24 h average concentration limits, while O3 is represented by a 1 h average concentration index. According to the data presented in the table, PM10 and other solid particulate matter are identified as the primary pollutants during winter, with their concentrations significantly higher than those observed in other seasons. Conversely, an analysis of pollutant concentration data collected from sampling points during both summer and winter reveals that overall concentrations in summer are lower; this can be attributed to meteorological conditions that favor the dispersion of pollutants during that season.

Table 1.

Summer and winter main pollutant concentrations.

To manage the infiltration of groundwater while simultaneously reducing dust pollution, multiple water trucks have been deployed in the mining area to utilize underground water for dust suppression on roads, work sites, and waste rock dumps. This approach has effectively lowered the concentration of particulate matter pollution. During summer, strong winds enhance dispersion effects, resulting in further reductions in pollutant concentrations. Conversely, during winter months, when temperatures remain below freezing for extended periods, watering operations may lead to ice formation on roads, increasing risks of vehicle skidding and posing serious safety hazards; thus, no dust suppression activities are scheduled during this season. Additionally, due to heating demands in the winter months, there is a substantial combustion of coal within the mining district. Coupled with low wind speeds that diminish dispersion effects and temperature inversion layers, among other factors, this results in slow dispersal rates for PM10 and other solid particulate pollutants. Consequently, winter sees an exacerbation of solid particulate matter pollution levels, leading to higher concentrations compared with other seasons. This often results in reduced visibility due to haze conditions within the mine site, which poses risks to both worker health and operational safety.

In addition to particulate matter, the relationship between NO2 and O3 also warrants further exploration. The primary sources of NO2 include emissions from operational vehicle exhaust and blasting activities. In contrast, O3 does not have a direct emission source; it is primarily produced via photochemical reactions involving NO2. This reaction is significantly enhanced under conditions of direct sunlight, high temperatures, intense solar radiation, and the presence of volatile organic compounds (VOCs). During the summer months, temperatures in mining areas often exceed 35 °C, accompanied by prolonged periods of strong sunlight. Moreover, the occurrence of photochemical reactions leads to an increase in O3 monitoring values. Simultaneously, a portion of NO2 is consumed, resulting in a decrease in the observed concentration levels of NO2. Consequently, during the summer months, there is a pronounced photochemical reaction between NO2 and O3, which results in lower NO2 measurements and higher O3 readings. In contrast, winter meteorological conditions give rise to opposing characteristics.

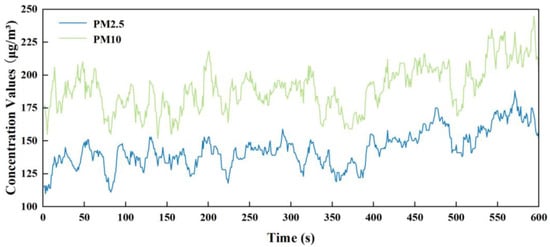

3.2. Variation in the Concentration of Suspended Particulate Matter

Real-time monitoring was conducted using a drone positioned directly above the work area to investigate the generation and dynamic variations in PM2.5 and PM10 particulate matter during loading operations. During the monitoring process, the drone was situated above the operational vehicles under clear skies with mild winds (the specific environmental parameters are detailed in Table 2). The time series changes in pollutant concentrations are illustrated in Figure 4. PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations exhibited significant fluctuations, and the average concentrations for PM2.5 and PM10 stabilized around approximately 160 μg/m3 and 220 μg/m3, respectively. Combining on-site workflow analysis indicates that mechanical disturbances during loading operations lead to instantaneous dust emissions; periodic loading actions trigger systematic increases in dust concentrations. However, due to open space conditions at outdoor mining sites and atmospheric diffusion effects, the raised dust quickly dilutes, resulting in rapid decreases in concentration levels. This phenomenon gives rise to unique cyclic fluctuations in the dust concentration characteristic of loading operations.

Table 2.

Environmental information of loading surface.

Figure 4.

Time variation diagram of dust concentration at 12:00.

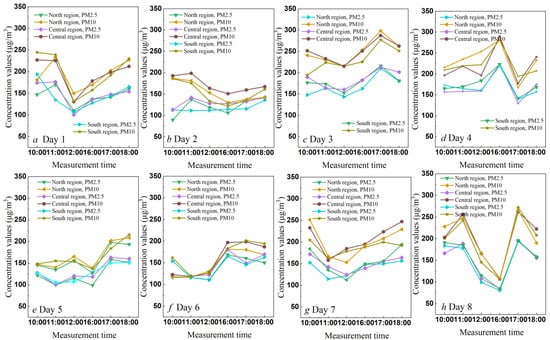

The monitoring process was further conducted on the north-side rock–soil excavation area, the central raw coal excavation area, and the south-side rock–soil excavation area using multi-regional comparative analysis. The monitored environmental parameters are detailed in Table 3, while the concentration variation characteristics are depicted in Figure 5. An analysis of the temporal distribution showed that during the period from 10:00 to 11:00 a.m., atmospheric vertical convection was significantly restricted due to morning temperature inversion layers, which resulted in a marked reduction in pollutant diffusion capacity; both PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations exhibited phase-specific high values during this time. Between noon and 16:00 p.m., as the inversion layer dissipates and atmospheric thermal convection intensifies, pollutants are diluted via vertical dispersion into higher altitudes, leading to a continuous decrease in concentration levels. During the period from 17:00 to 18:00 p.m., a deterioration of diffusion conditions occurs due to decreased solar radiation, causing surface cooling and increased atmospheric stability; consequently, pollutant concentrations experience a secondary increase illustrating typical cyclic alternating effects between temperature inversion and convection.

Table 3.

Environmental information from monitoring days.

Figure 5.

Variation in suspended particulate matter concentration at different dates and time points: (a–d) represent time samples collected before snowfall; (e,f) correspond to sampling on the day of snowfall; and (g,h) denote time samples taken after snowfall.

An examination of spatial distribution reveals significant spatial differentiation for PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations: The rock–soil excavation areas contain substantial amounts of silty debris where fine particulate matter easily forms a suspension under mechanical disturbance or wind action; hence, PM2.5 concentrations here exceed those at the central raw coal excavation area by approximately 22–35%. Conversely, the relatively dense coal–rock structure within the central raw coal excavation area generates fewer inhalable particulates throughout fragmentation processes, which results in overall lower concentration levels there. Additionally, the proximity of the northern rock–soil extraction site to main transportation routes leads vehicular operations’ generated secondary dust emissions to combine with primary dust from extraction activities, resulting in PM10 concentrations markedly exceeding those at central raw coal sites by around 40–55%.

The snowfall process significantly impacts the concentration of pollutants during mining operations. To investigate the impact of snowfall on particulate matter concentrations, the data collected in March 2025 were analyzed and categorized into three phases: pre-snowfall, during snowfall, and post-snowfall. Figure 5e,f illustrate that after snowfall, the concentrations of various suspended particulate matter exhibit a marked downward trend, with peak concentrations of PM2.5 and PM10 decreasing by 75% and 82%, respectively, compared with levels before the snowfall. This reduction is primarily attributed to the wet deposition effect associated with snowfall. As snowflakes fall, they collide with and adsorb airborne suspended particles; simultaneously, increased humidity from melting snow further enhances the hygroscopic settling efficiency of particulates. This phenomenon demonstrates the substantial mitigating effects of natural precipitation on dust pollution in open-pit mining areas.

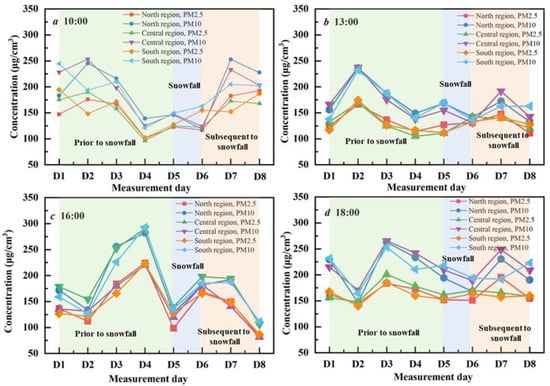

The monitoring of particulate matter concentrations at the same time points on different dates, as illustrated in Figure 6, reveals significant temporal periodic characteristics. At the typical time intervals of 10:00 a.m., 13:00 p.m., 16:00 p.m., and 18:00 p.m., the peak concentrations of PM2.5 and PM10 at D3 and D8 reached 285 μg/m3 and 268 μg/m3, respectively, significantly higher than those at D6 and D7, which recorded concentrations of 112 μg/m3 and 105 μg/m3 (measured two days after snowfall). This observation validates the short-term significant suppression effect of snow-induced wet deposition on the particulate matter concentration. Within one to two days following snowfall, the concentration of particles across various size fractions decreased by approximately 60–75% compared with sunny day averages.

Figure 6.

The concentration of suspended particulate matter at the same time point on different dates: (a) at 10:00; (b) at 13:00; (c) at 16:00; and (d) at 18:00.

Further analysis indicates that the concentrations of D1–D4 and D7–D8 show a significant increase during the morning and evening, with PM10 averages ranging from 240 to 260 μg/m3. Conversely, a trough is observed during midday, with average concentrations between 150 and 170 μg/m3. Specifically, radiation cooling near the ground before and after sunrise creates an inversion layer that inhibits vertical mixing in the atmosphere, resulting in pollutant accumulation near the sampling site. During midday, this inversion layer breaks down due to enhanced thermal convection, facilitating the upward dispersion of particulate matter. The above analysis further demonstrates that the variation in particulate matter concentrations is closely associated with the formation and dissipation processes of atmospheric temperature inversion. However, unaccounted anthropogenic activities may lead to an increase in particulate matter concentrations.

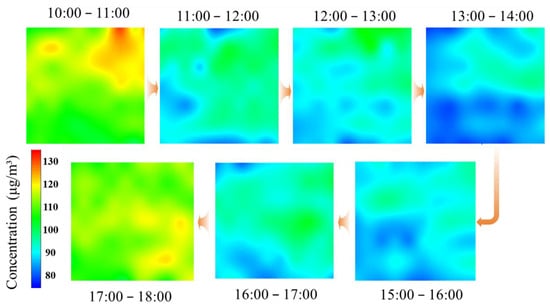

3.3. Temporal Variations in the Distribution of Pollutant Concentrations

The monitoring was conducted continuously at a height of 20 m above the working surface (relative to the ground). Monitoring took place from 10:00 a.m. to 18:00 p.m., with interruptions occurring between 14:00 p.m. and 15:00 p.m. The time-varying concentration patterns of NO2 are illustrated in Figure 7. From a temporal perspective, the concentrations of NO2 were notably elevated during the periods from 10:00 a.m. to 11:00 a.m. and from 17:00 p.m. to 18:00 p.m., with average concentrations recorded at approximately 108 μg/m3 and 105.5 μg/m3, respectively. Overall, there was a declining trend in NO2 concentrations from morning until midday, whereas an increasing trend was observed from midday into the evening hours; specifically, concentrations reached their minimum around noon, with an average level of about 85 μg/m3.

Figure 7.

Cloud images of NO2 concentration over time at a height of 20 m above the working surface.

From a horizontal distribution perspective, during the morning period, there is a notable enrichment phenomenon in the northeastern region, with peak concentrations reaching 131 μg/m3. Between 11:00 a.m. and 13:00 p.m., the distribution of NO2 is relatively uniform; however, overall levels are higher in both the eastern and northern parts. From 13:00 p.m. to 14:00 p.m., an enrichment phenomenon reappears in the northeastern area. During the hours of 15:00 p.m. to 18:00 p.m., NO2 distribution remains largely uniform; specifically, from 15:00 p.m. to 17:00 p.m., a pattern emerges where concentrations are generally higher in the northeast and lower in the southwest. Notably, between 17:00 p.m. and 18:00 p.m., elevated levels are observed in the southeastern region.

According to the information presented in Table 4, the concentration of NO2 exhibits a trend of initially decreasing followed by an increase. This observed pattern aligns with the daily variation characteristics of NO2 concentrations noted in relevant studies. During the period from 13:00 p.m. to 14:00 p.m., the NO2 concentration reaches its minimum value, which may be attributed to stronger solar radiation during this timeframe that enhances photochemical reactions, resulting in the conversion or dilution of NO2 within the atmosphere. In contrast, the concentration of solid particulate matter, such as PM10, demonstrates a pattern of first stabilizing and then gradually increasing. It peaks at 265 μg/m3 between 16:00 p.m. and 17:00 p.m. before subsequently declining. This variation is primarily influenced by phenomena such as temperature inversions and diurnal temperature changes affecting dispersion dynamics. Furthermore, concentrations of SO2 and CO remain relatively low at approximately 1.4–3.3 μg/m3 and 0.8–1.1 μg/m3, respectively; thus, their impact on environmental pollution is minimal, with overall fluctuations being insignificant.

Table 4.

Major pollutant concentrations over time.

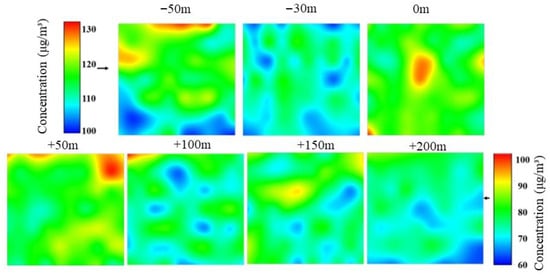

3.4. The Distribution of Pollutant Concentration Varies with Altitude

The NO2 distribution map obtained from this monitoring is illustrated in Figure 8. Additionally, Table 5 presents the variations in suspended particulate matter concentration with altitude. The data presented in the figure indicate that the concentration of NO2 is generally higher in the lower section of the mining pit compared with the upper section. Furthermore, as height increases, there is a downward trend in the NO2 concentration. This suggests that the ventilation conditions in the lower region of the mining pit are relatively poor, which hinders pollutant dispersion and results in elevated concentrations. Additionally, the NO2 levels in this area are significantly influenced by production activities, particularly in zones associated with major mining and transportation processes, where concentrations are notably high. These localized emission hotspots align with the core assumptions of Gaussian plume models, which describe how point/area sources of pollution disperse vertically under limited atmospheric mixing conditions. Moreover, it was observed that at the mine entrance, NO2 concentrations are higher than those measured 30 m below; this could be attributed to both ventilation conditions at the entrance and concentrated production activities. In contrast, within the upper region of the mining pit, NO2 concentration tends to be elevated toward its northern part but decreases gradually with increasing height while maintaining a more uniform distribution overall. This vertical pattern, characterized by gradual dilution with height, aligns with Gaussian plume predictions for pollutant dispersion in semi-confined environments (e.g., open-pit mines), and indicates that areas located at lower elevations within this section are heavily impacted by emissions from northern waste dumps and vehicular transport. Due to weak dispersion mechanisms coupled with high emission rates in these areas, an increase in the nitrogen dioxide concentration is detected specifically toward the north.

Figure 8.

Cloud images of NO2 concentration with height.

Table 5.

Variation in suspended particulate matter concentration with height.

As the altitude increases, the diffusion process intensifies, leading to a reduction in the NO2 concentration and a more uniform distribution. The dispersion patterns of PM2.5 and PM10 particulate matter exhibit similarities to those of NO2. In the area beneath the pit, where diffusion occurs at a slower rate, the concentrations of PM2.5 and PM10 are approximately 163–166 μg/m3 and 197–215 μg/m3, respectively, indicating relatively high levels; conversely, above the pit where diffusion is more rapid, the concentrations are around 90–136 μg/m3 for PM2.5 and 113–184 μg/m3 for PM10, reflecting comparatively lower levels. Furthermore, an inversion phenomenon is observed at the top of the pit, suggesting that a temperature inversion layer exists there. This layer disrupts the vertical turbulent mixing required for Gaussian plume dispersion and exponential concentration decay, thereby altering pollutant dispersion and distribution patterns. Additionally, given the safety hazards associated with UAV near-ground operations (0–2 m above ground level), this study did not implement experiments targeting this specific flight regime. In subsequent work, we plan to integrate a high-precision automatic obstacle avoidance system into the UAV platform, thereby enabling investigations into the spatiotemporal variation characteristics of near-ground atmospheric pollutants.

3.5. CNN-LSTM Model for Predicting Pollutant Concentrations

3.5.1. Interpretation

The superiority of the CNN-LSTM hybrid model stems from its ability to accurately model spatiotemporally coupled features: the CNN layer compensates for the deficiency of LSTM in extracting spatially heterogeneous features, while the LSTM layer overcomes the limitation of the CNN in capturing long-term temporal dependencies. The CNN-LSTM hybrid model integrates the spatial feature extraction capabilities of CNNs—achieved through multi-layer convolutional kernels that capture local concentration gradients—with the temporal dynamic modeling advantages offered by LSTMs, making it more suitable for complex environmental monitoring and prediction scenarios.

3.5.2. Results

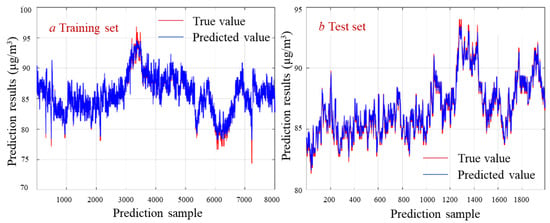

The predictive outcomes not only exhibit a higher degree of smoothness (with the proportion of outliers reduced to 3.1% and RMSE = 0.512) but also demonstrate an improved correlation coefficient with the actual concentration curve, reaching 0.971. This indicates that the architecture possesses a synergistic enhancement effect in learning spatiotemporal coupling features, as illustrated in Figure 9. The quantitative prediction results for each model are presented in Table 6.

Figure 9.

The prediction results of the CNN-LSTM model: (a) training set; (b) test set.

Table 6.

Model-predicted quantitative results.

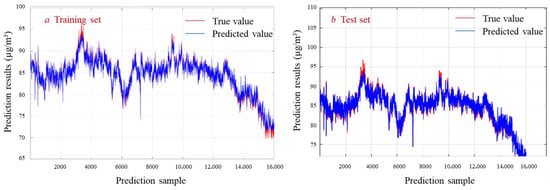

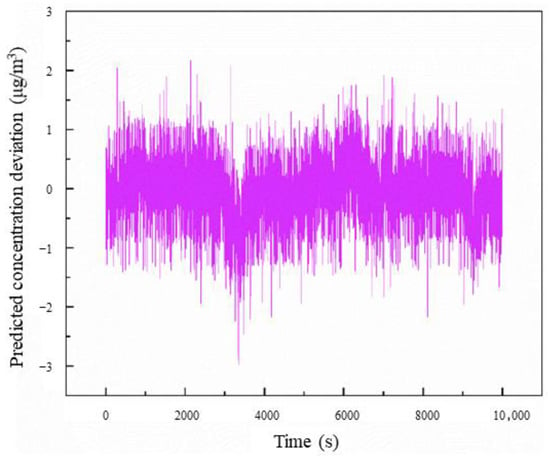

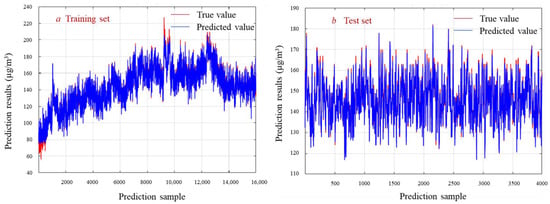

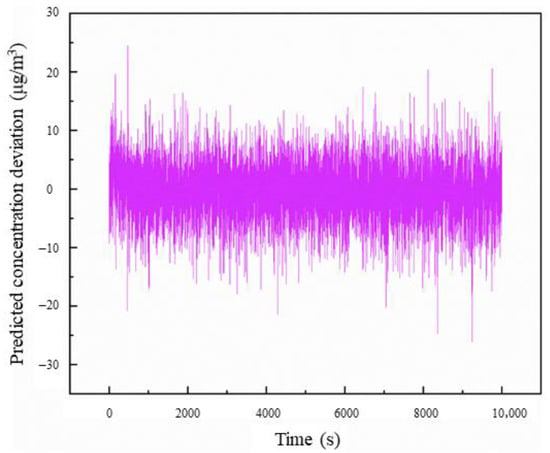

The concentrations of two typical atmospheric pollutants, NO2 and PM2.5, were predicted to compare the performance of the models in predicting different types of pollutants. The prediction results and concentration prediction deviations for the NO2 model are illustrated in Figure 10 and Figure 11, respectively. Correspondingly, the prediction results and concentration prediction deviations for the PM2.5 model are shown in Figure 12 and Figure 13.

Figure 10.

Prediction results of NO2 concentration: (a) training set; (b) test set.

Figure 11.

Prediction bias of NO2 concentration.

Figure 12.

Prediction results of PM2.5 concentration: (a) training set; (b) test set.

Figure 13.

Prediction bias of PM2.5 concentration.

The R2 value for the NO2 prediction time series reached 0.9918, with an RMSE of 0.5962. A comparison of predicted NO2 concentrations over a duration exceeding two hours revealed that the deviation values remained within the −3 to +3 μg/m3 range. The average actual concentration of NO2 during this prediction period was found to be 85.78 μg/m3, resulting in an error margin below 3.5%.

The R2 value for the PM2.5 concentration prediction time series reached 0.9574, with an RMSE of 4.516. The deviations between the predicted concentrations and the actual concentrations of PM2.5 over a duration of more than two hours primarily fell within the range of −10 to 10 μg/m3, while only a small fraction of error values exceeded 20 μg/m3. During the prediction period, the average actual concentration of PM2.5 was measured at 137.86 μg/m3, resulting in an error margin of less than 7.3%.

The model optimizes its ability to approximate the nonlinear dynamics of pollutant concentrations using an adaptive weight adjustment strategy during the training phase and demonstrates excellent extrapolation stability in the prediction phase. This remarkable predictive performance indicates that the deep learning architecture not only meets the demands for real-time analysis of environmental monitoring data but also provides a reliable mathematical basis for decision support systems related to pollution source tracing and emission control. Particularly in addressing compound atmospheric pollution events, the model’s capability for synergistic multi-pollutant predictions offers crucial technological support for formulating precise joint prevention and control strategies. This has significant practical value in enhancing the intelligent management of urban atmospheric environments. Notably, this work was limited to a specific region and did not fully consider the geographical characteristics among open-pit coal mines. Consequently, the prediction accuracy is prone to degradation when the model is directly transferred. Accordingly, future research should focus more on developing the model’s adaptive parameter adjustment module by integrating transfer learning methods to achieve rapid cross-region adaptation and accurate prediction.

4. Conclusions

The use of drones as monitoring tools has facilitated the analysis of pollutant concentrations and distribution patterns at various heights and times within the mining site. In summer, pollutants are primarily NO2 and O3. Due to ongoing dust suppression operations and favorable ventilation conditions during this season, suspended particulate matter, such as PM2.5 and PM10, both settles and disperses, leading to a reduction in their concentrations. In winter, the predominant pollutants are PM2.5 and PM10 particles. While loading activities may cause localized increases in particulate matter concentrations, dust disperses rapidly without leading to sustained accumulation. The concentration of NO2 exhibits a temporal pattern characterized by higher levels in the early morning and evening, with lower levels observed around noon. Pollutant dispersion is largely influenced by temperature inversion layers; meanwhile, concentrations of PM2.5 and PM10 initially increase and subsequently decrease throughout the day, peaking in the afternoon. NO2 concentrations are notably higher below extraction pits; they initially rise before gradually declining—this pattern is particularly pronounced in northern areas, where higher elevations show more uniform distributions despite slower decline rates with increasing altitude. Additionally, employing a CNN-LSTM model for predicting pollutant concentration data yields high-accuracy results; merely 3.1% of predictions are anomalies, with an RMSE value of 0.512 and an R2 value of 0.971.

In this work, the single flight duration of the unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) is subject to certain limitations, which may result in asynchrony in both temporal and spatial dimensions for the same observation point. One of the future research directions should be to explore the cooperative control of multi-UAV systems to reduce measurement lag. Meanwhile, in future work, the relationship between dust particle size distribution and toxicity as well as specific genotoxicity requires more in-depth study.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, T.W.; methodology, software, H.L.; investigation, resources, Q.W.; data curation, N.Z.; validation, B.M.; formal analysis, J.T.; conceptualization, L.C.; writing—review and editing, supervision, funding acquisition, X.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Jiangsu Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. BK20240105); Supported by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation under Grant Number 2025M771806.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Tengfeng Wan, Huicheng Lei, Qingfei Wang, Nan Zhou, Bingbing Ma, Jingliang Tan and Li Cao were employed by the company National Energy Group Xinjiang Chemical Energy Co., Ltd. The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADF | Augmented Dickey–Fuller |

| KPSS | Kwiatkowski–Phillips–Schmidt–Shin |

| LSTM | Long short-term memory |

| MAE | Average absolute error |

| RMSE | Root mean square error |

| R2 | Coefficient of determination |

| SE | Standard error |

| UAV | Unmanned aerial vehicle |

| PAHs | Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons |

Appendix A

Continuous image acquisition is performed using a high-resolution camera mounted on a UAV platform, enabling the capture of abundant ground information. The UAV captures imagery along a preset flight path, with the camera acquiring ground images at a specified overlap rate to generate a continuous image sequence. Subsequently, the real-world coordinates of objects in three-dimensional space are computed by leveraging the angular relationships between images and the coordinates of image points. The core principle underpinning this computation process is the collinearity condition equation, whose fundamental form is presented in Equation (A1):

where x is the position coordinates of the image point on the image plane; X is the positioning point of the object point in the ground coordinate system; XS is the position coordinates of the camera center (i.e., the lens center) in the ground coordinate system; f is the focal length of the camera; is the position coordinate of the principal point. These parameters collectively characterize the geometric relationship between image points and object points in photogrammetry, with specific technical parameters provided in Table A1.

Table A1.

Technical parameters of photogrammetry.

Table A1.

Technical parameters of photogrammetry.

| No. | Parameter | Values |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gimbal tilt angle (tilt) | 45° |

| 2 | Route altitude | 200 m |

| 3 | Route speed | 7~10 m/s |

| 4 | Flight route speed (tilted flight) | 15 m/s |

| 5 | Lateral overlap | 70% |

| 6 | Longitudinal overlap | 80% |

| 7 | Lateral overlap (tilt) | 60% |

| 8 | Longitudinal overlap (tilt) | 70% |

References

- Zhao, Y.M.; Li, G.M.; Luo, Z.F.; Zhang, B.; Dong, L.; Liang, C.C.; Duan, C.L. Industrial application of a modularized dry-coal-beneficiation technique based on a novel air dense medium fluidized bed. Int. J. Coal Prep. Util. 2017, 37, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Wang, S.; Xu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Dong, L.; Chen, Z. Particle flow characteristics in a gas-solid separation fluidized bed based on machine learning. Fuel 2022, 314, 123039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, D.; Jiang, H.; Dong, Y.; Gao, Z.; Hong, K.; Dong, L. Prediction of fluidization state in a pulsed gas-solid fluidized bed. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 517, 164471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhou, W.; Wang, Z.; Lu, X.; Zhang, Y. Characterization and Concentration Prediction of Dust Pollution in Open-Pit Coal Mines. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, U.; Usman, F.; Zeb, B.; Alam, K.; Huang, Z.W.; Shah, A.T.L.; Ahmad, I.; Ullah, S. In-Depth Analysis of Physicochemical Properties of Particulate Matter (PM10, PM2.5 and PM1) and Its Characterization Through FTIR, XRD and SEM-EDX Techniques in the Foothills of the Hindu Kush Region of Northern Pakistan. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 124. [Google Scholar]

- Howaniec, N.; Kuna-Gwozdziewicz, P.; Smolinski, A. Assessment of Emission of Selected Gaseous Components from Coal Processing Waste Storage Site. Sustainability 2018, 10, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.B.; Liu, K.L.; Xie, W.; Pan, W.P.; Riley, J.T. Soluble polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in raw coals. J. Hazard. Mater. 2000, 73, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellwanger, J.H.; Ziliotto, M.; Chies, J.A.B. Lung Deposition of Particulate Matter as a Source of Metal Exposure: A Threat to Humans and Animals. Toxics 2025, 13, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, L.; Luo, R. Spatiotemporal variations of PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations between 31 Chinese cities and their relationships with SO2, NO2, CO and O3. Particuology 2015, 20, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhavanam, B.P.R.; Ragam, P. LoRa Sense: Sensing and Optimization of LoRa Link Behavior Using Path-Loss Models in Open-Cast Mines. Cmes-Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2025, 142, 425–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.X.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, J.X.; Wang, S. Research analysis on the airflow-particle migration and dust disaster impact scope by the moving mining truck in the open-pit mine. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 184, 1442–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penchala, A.; Patra, A.K.; Santra, S.; Dubey, R.; Mishra, N.; Nazneen Pradhan, D.S. Assessment of vertical transport of PM in a surface iron ore mine due to in-pit mining operations. Measurement 2025, 240, 115580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.R.; Chen, J.L. An anomaly feature mining method for software test data based on bat algorithm. Int. J. Data Min. Bioinform. 2022, 27, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, E.V.; Rajeev, K.; Mishra, M.K. Effect of Clouds on the Diurnal Evolution of the Atmospheric Boundary-Layer Height Over a Tropical Coastal Station. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 2020, 175, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Russo, A.; Du, H.; Xiang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, C. Impact of meteorological conditions at multiple scales on ozone concentration in the Yangtze River Delta. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 62991–63007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, T.; Xia, J.; Wang, C.; Cao, L.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, Y.; Shen, L.; et al. Elevated 3D structures of PM2.5 and impact of complex terrain-forcing circulations on heavy haze pollution over Sichuan Basin, China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021, 21, 9253–9268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, M.; Jiang, D. Application of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles in logistics: A literature review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.F.; Zhi, X.D.; Pu, Y.C.; Zhang, Q.F. A multi-scale UAV image matching method applied to large-scale landslide reconstruction. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2021, 18, 2274–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, V.K.; Vallikannu, R. Air pollution prediction model for estimating and forecasting particulate matter PM2.5 concentrations using SOSE-RMLP approach. Int. J. Glob. Warm. 2023, 29, 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Zhao, Y.; Xiao, W.; Hu, Z. A review of UAV monitoring in mining areas: Current status and future perspectives. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2019, 6, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Qiu, X.; Ding, C. A Three-Dimensional Imaging Method for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle-Borne SAR Based on Nested Difference Co-Arrays and Azimuth Multi-Snapshots. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Kang, H.T.; Zhang, W.C.; Jia, Y.N.; Zheng, H. Application of UAV in open-pit mine monitoring. Bull. Surv. Mapp. 2020, 9, 85–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bui, X.N.; Lee, C.; Long, N.Q.; Ahmad, A.; Cao, X.C.; Nghia, N.V.; Canh, L.V.; Nguyen, H.; Thảo, L.Q.; Huong, D.T.; et al. Use of unmanned aerial vehicles for 3D topographic mapping and monitoring the air quality of open-pit mines. Inżynieria Miner. 2019, 21, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Yu, H.F.; Huang, G.D. PM2.5 monitoring technology based on unmanned aerial vehicle. Bull. Surv. Mapp. 2017, S1, 147–151. [Google Scholar]

- Shih, D.H.; To, T.H.; Nguyen, L.S.P.; Wu, T.W.; You, W.T. Design of a spark big data framework for PM2.5 air pollution forecasting. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, W.; Cui, Y.; Wang, X.; Shen, J. Optimization of Operational Parameters of Plant Protection UAV. Sensors 2024, 24, 5132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.Z.; Zhang, S.Y.; Zhang, K.; Yin, J.J.; Varela, M.; Miao, J.H. Developing high-resolution PM2.5 exposure models by integrating low-cost sensors, automated machine learning, and big human mobility data. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1223160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilik, A.; Ogrenci, A.S.; Ozmen, A. Air quality prediction using CNN plus LSTM-based hybrid deep learning architecture. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 11920–11938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taamté, J.M.; Noube, M.K.; Signing, V.R.F.; Hamadou, Y.A.; Masahiro, H.; Saïdou; Tokonami, S. Real-time air quality monitoring based on locally developed unmanned aerial vehicle and low-cost smart electronic device. J. Instrum. 2024, 19, P05036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augello, A.; Gaglio, S.; Lo Re, G.; Peri, D. Multi-Objective Optimization of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Three-Dimensional Paths for Air Quality Monitoring and Environmental Sensing. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 187504–187517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, P.; Zhang, J.K. Deep Learning Model for Spatiotemporal Distribution Prediction of Air Pollutant Concentrations. Comput. Mod. 2025, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, P.; Li, Y.; Wen, L.; Deng, X. Air quality prediction models based on meteorological factors and real-time data of industrial waste gas. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekula, P.; Ustrnul, Z.; Bokwa, A.; Bochenek, B.; Zimnoch, M. Random forests assessment of the role of atmospheric circulation in pm10 in an urban area with complex topography. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Hu, D.B.; Li, Q. Study on prediction model of atmospheric pollutant concentration based on wavelet decomposition and SVM. Acta Sci. Circumst. 2020, 40, 2962–2969. [Google Scholar]

- Ketu, S. Spatial air quality index and air pollutant concentration prediction using linear regression based recursive feature elimination with random forest regression (RFERF): A case study in India. Nat. Hazards 2022, 114, 2109–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, E.; Deo, R.; Prasad, R.; Parisi, A.; Raj, N. Deep Air Quality Forecasts: Suspended Particulate Matter Modeling With Convolutional Neural and Long Short-Term Memory Networks. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 209503–209516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Han, K.; Yu, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, K.; Kim, H. Development of a CNN plus LSTM Hybrid Neural Network for Daily PM2.5 Prediction. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).