A Time-Dependent Intrinsic Correlation Analysis to Identify Teleconnection Between Climatic Oscillations and Extreme Climatic Indices Across the Southern Indian Peninsula

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (i)

- To compute a suite of ETCCDI-based ECIs for SPI’s homogeneous monsoon region.

- (ii)

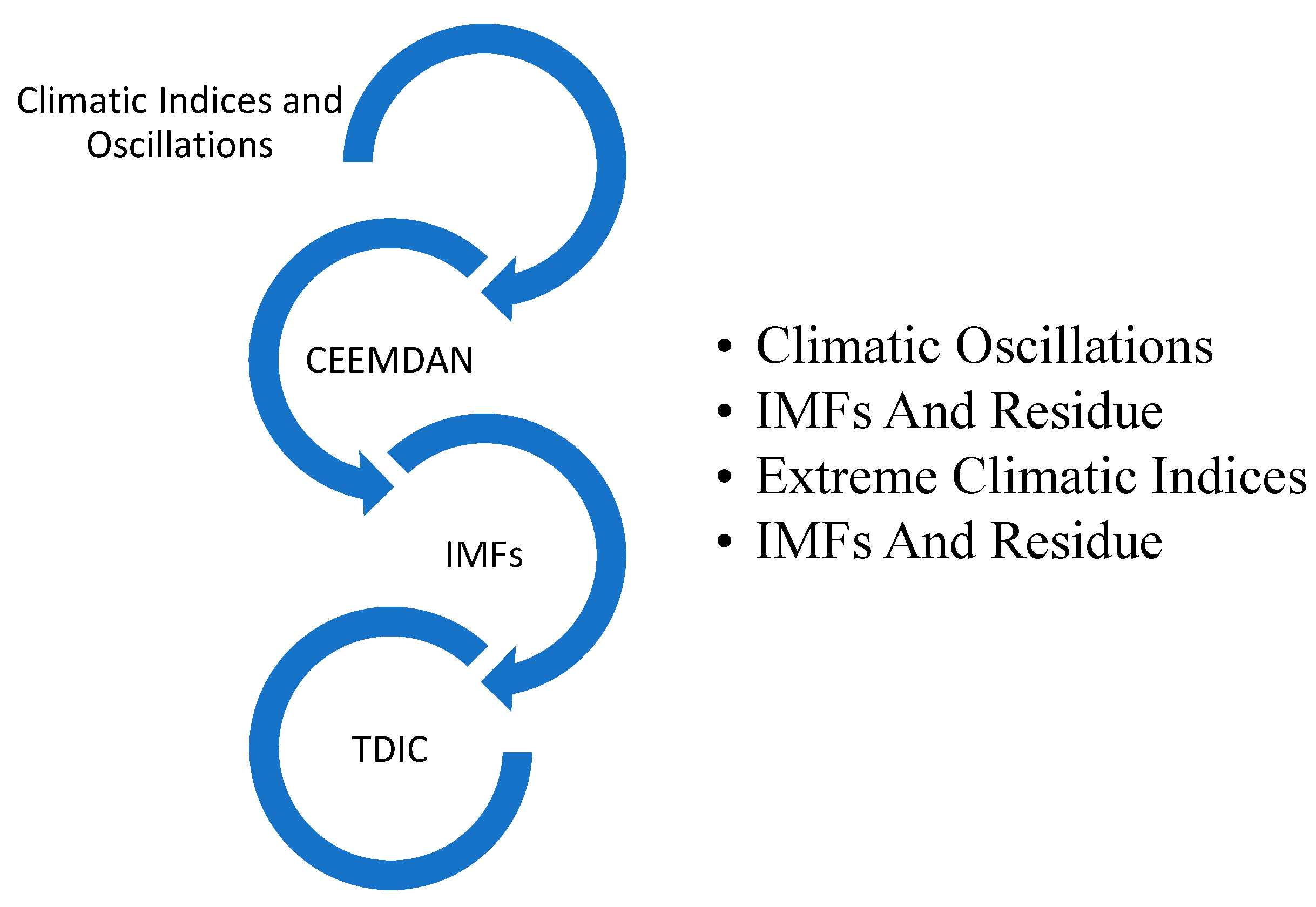

- To resolve the dominant periodicities of ECIs and COs using CEEMDAN.

- (iii)

- To quantify dynamic, scale-resolved associations between ECIs and COs via the CEEMDAN-TDIC framework.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. CEEMDAN

- Employ EMD for M resamples and extract the 1st componentwhere m = 1, 2, …, M is the noise measure for this initial stage.This step demonstrates that the first mode derived from CEEMDAN is identical to that obtained from EEMD.

- Find the initial residual as .

- Decompose the resamples, , until their first EMD component evolves. Subsequently, findwhere Ek(·) is the operation of kth component by EMD; is the noise measure for k = 1.

- Find the kth residue asfor k = 2, 3, …, K, where the IMFs are obtained by CEEMDAN.

- Estimate and

- Repeat from (4) for subsequent k-values until the residual is a monotonical trend or a single peak has evolved.The final residual becomes

2.2. TDIC Method

- Invoke CEEMDAN to decompose the pair of series to different modes.

- Select the IMF pairs with comparable periodicity.

- Determine the instantaneous frequencies (IFs) of IMF pairs using Hilbert spectral analysis and hence IPs.

- Compute the minimum moving window length (td) as the maximum of IPs at each instant tk, i.e., where and are IPs.

- Find the size of the moving window where n is chosen as unity.

- Assume IMF1 and IMF2 are two IMFs with comparable mean periods but belong to the different series in the pair. The TDIC measure can be estimated at any instant, , where Corr is Pearson correlation.

- Use Student t-test to find statistical significance of correlations.

- Repeat steps 4 to 7 in an iterative manner until the window crosses the end points of the signal.

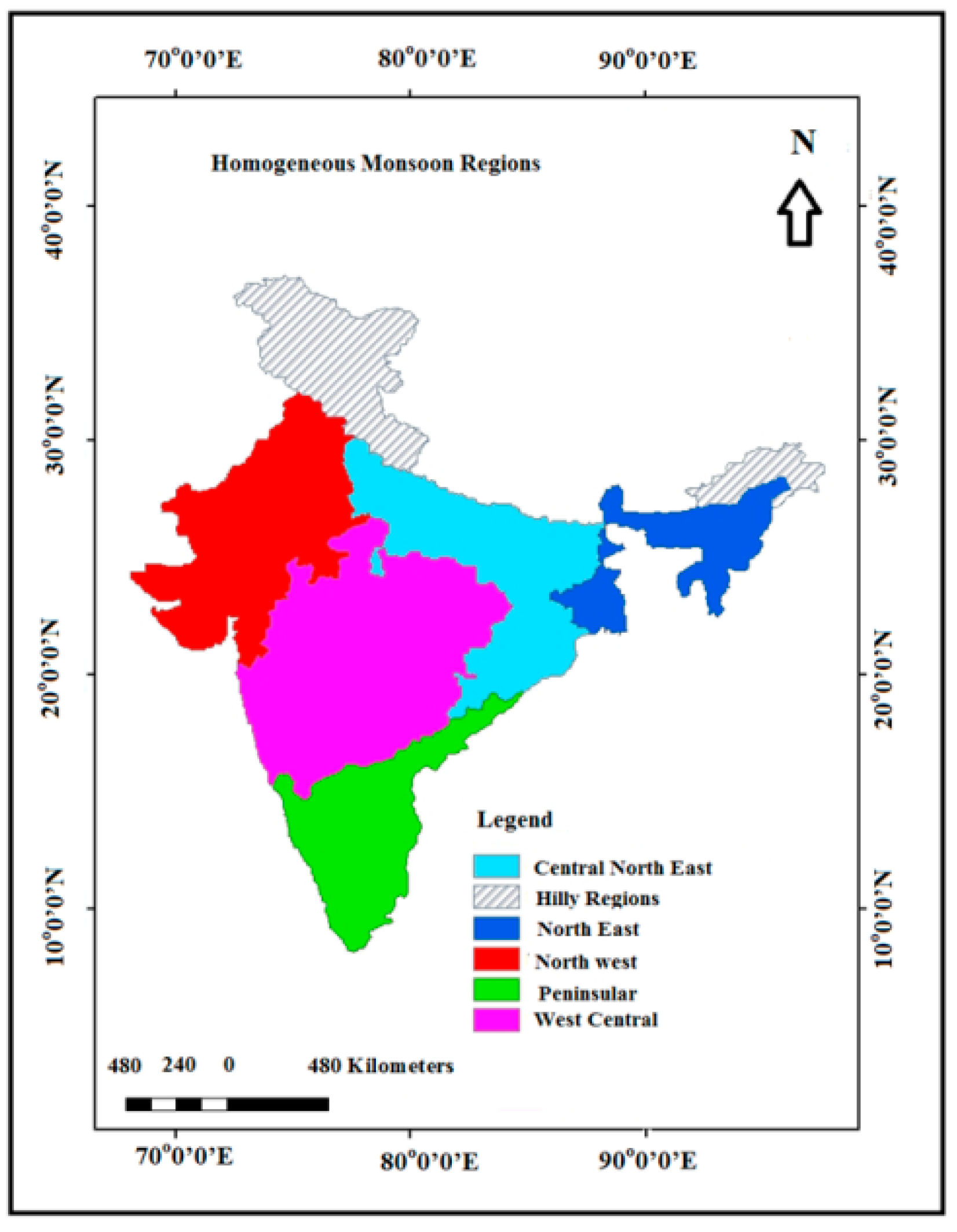

3. Study Area and Data

4. Results

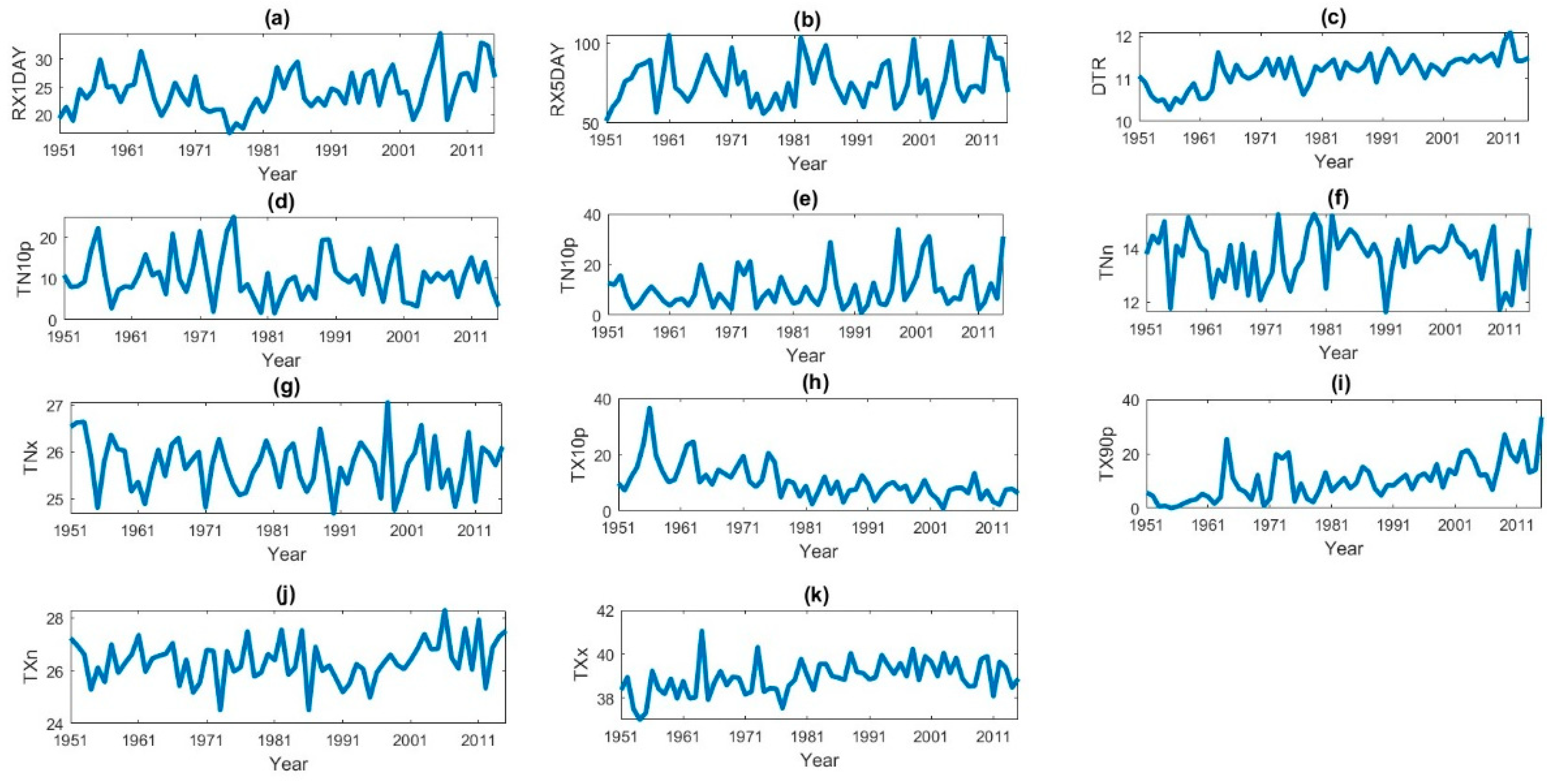

4.1. Extreme Climatic Indices

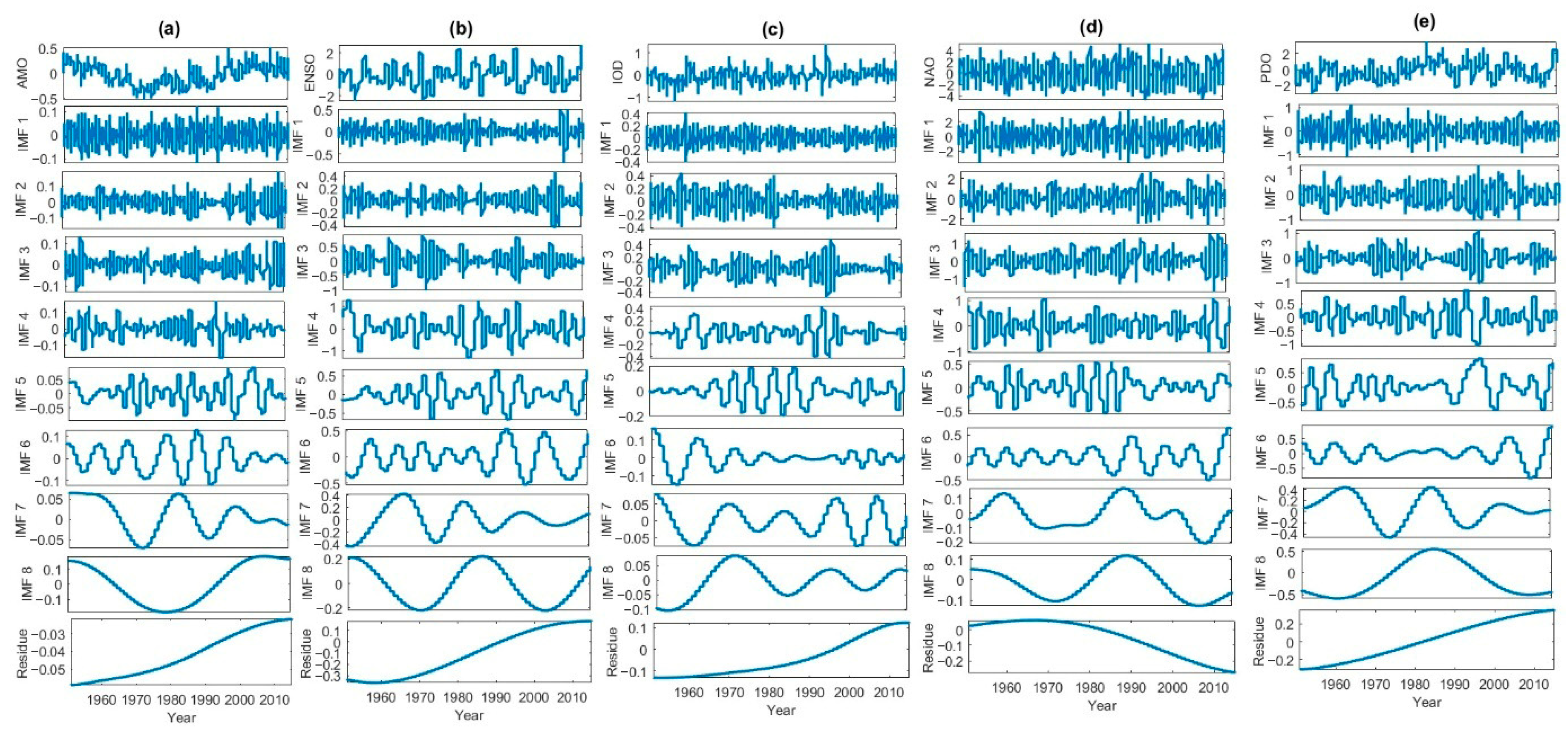

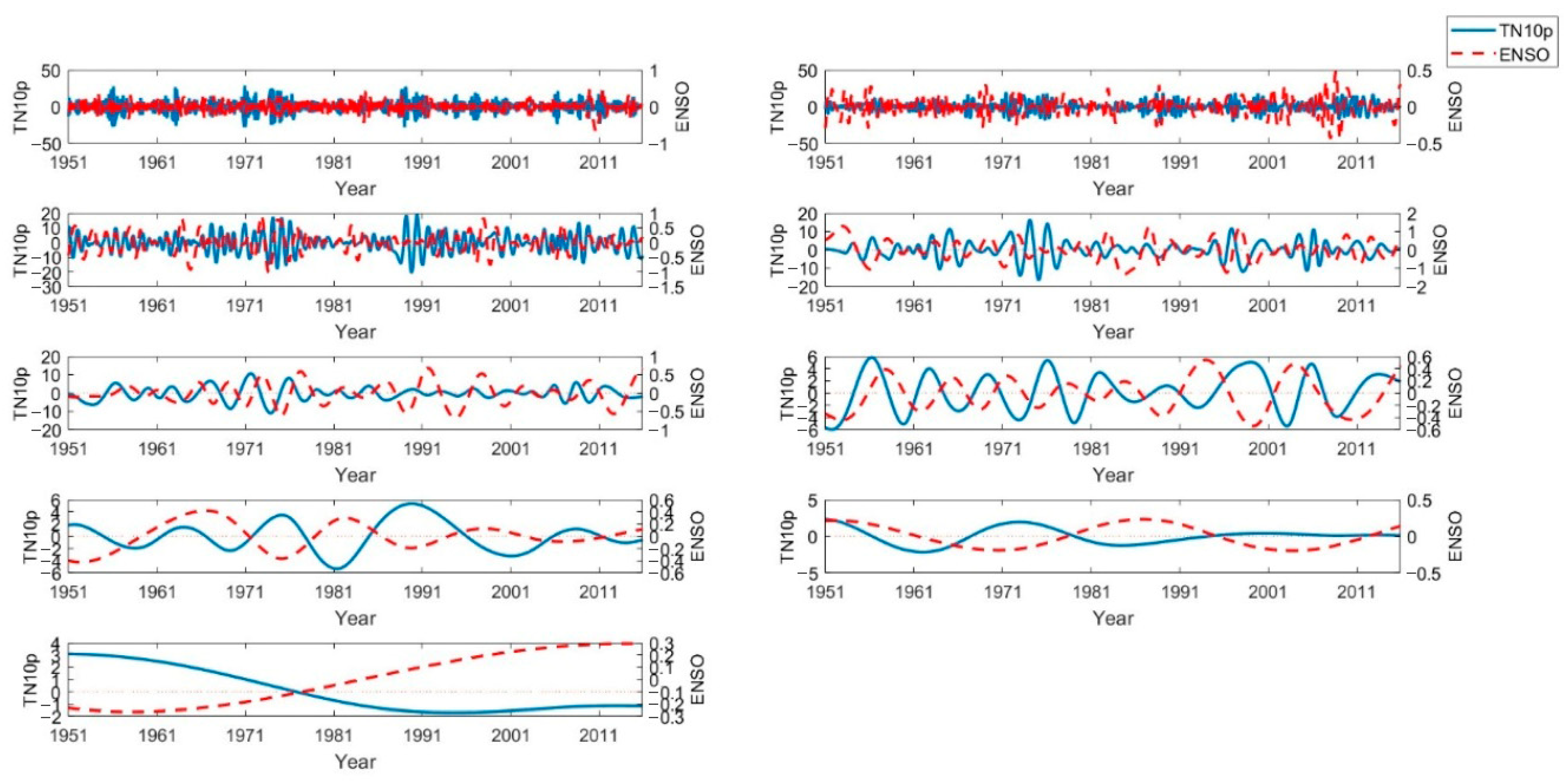

4.2. The Decomposition of the Data Signal

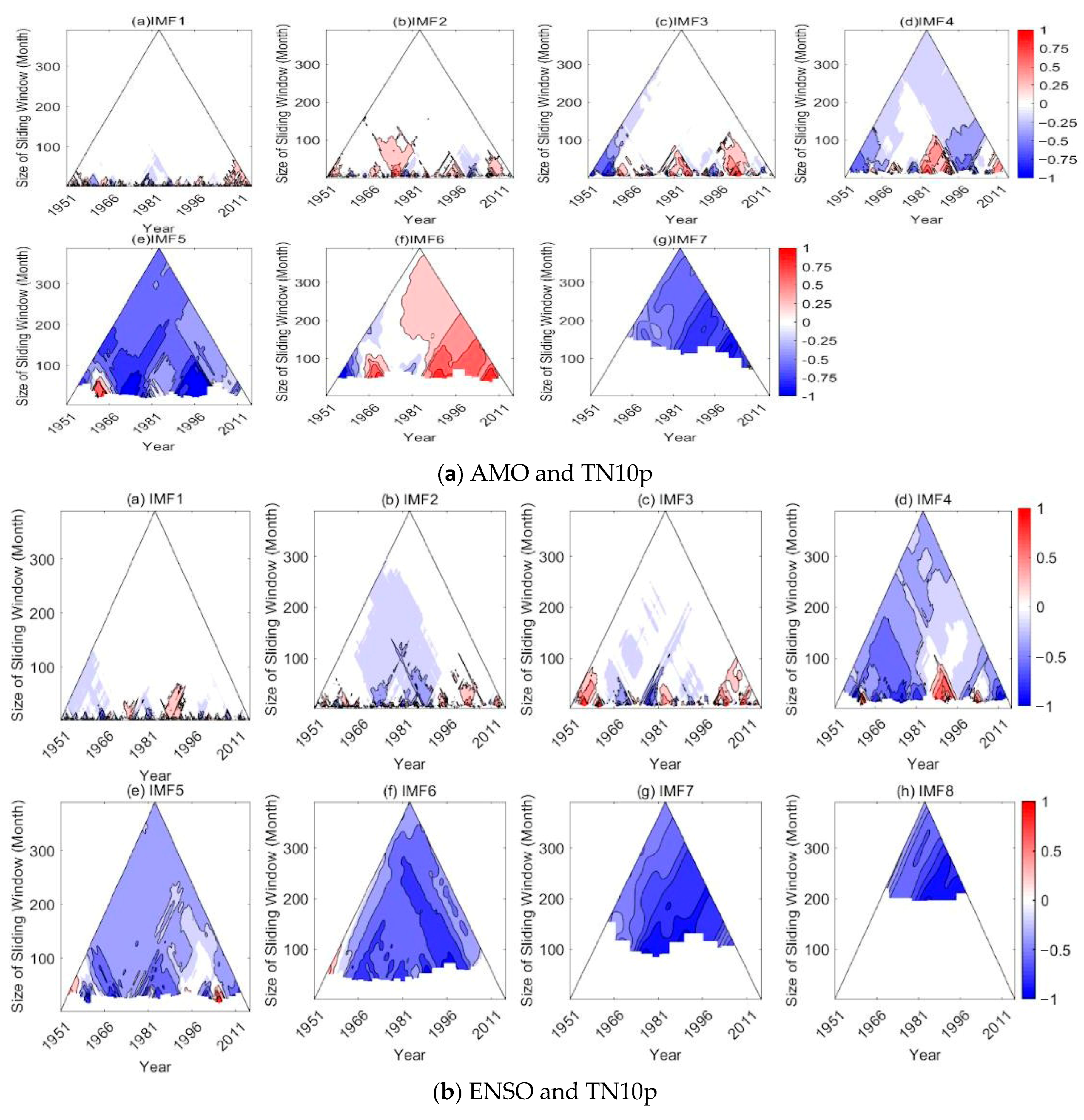

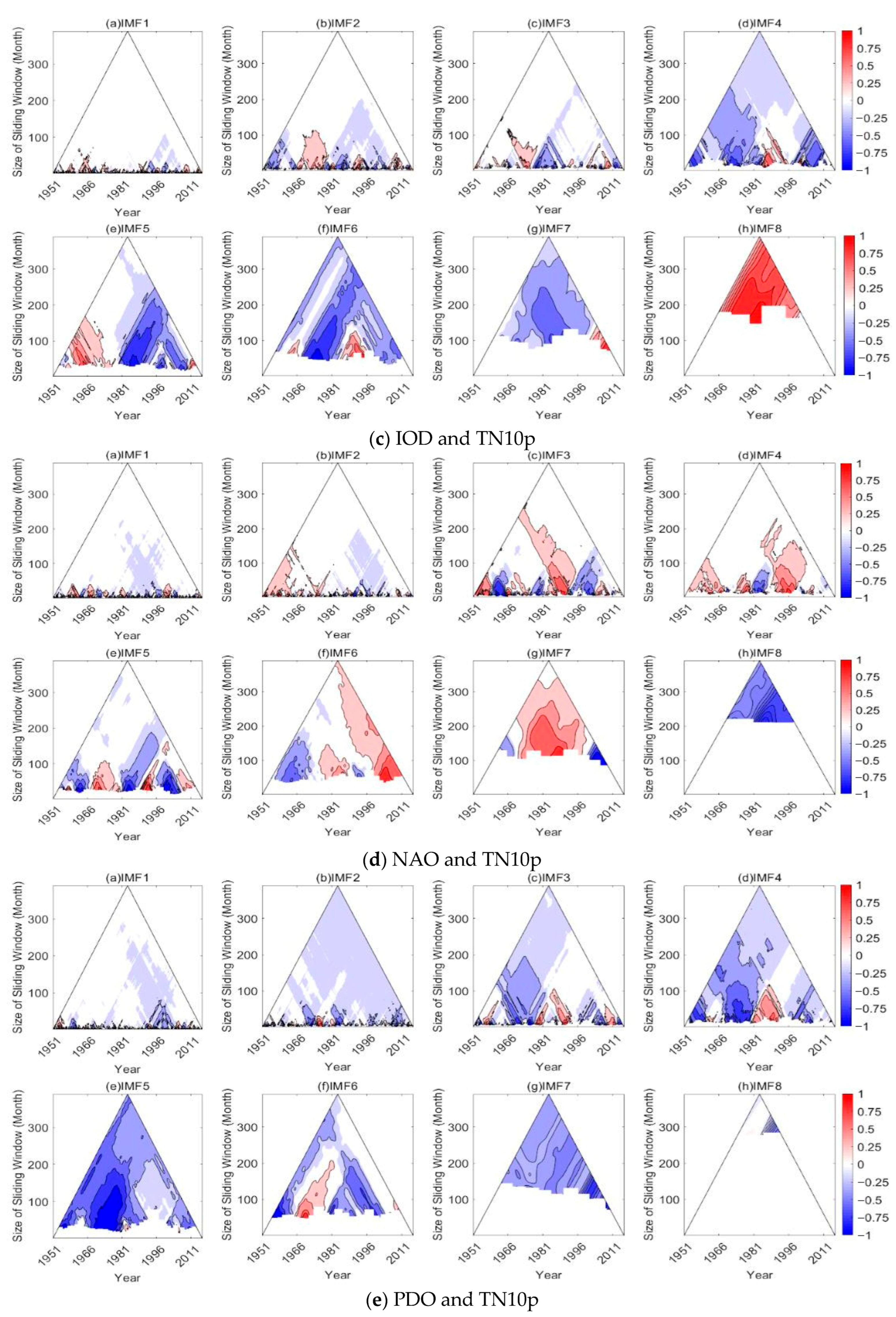

4.3. Correlation Analysis

Linear Correlation

5. Conclusions

- The PDO and AMO decrease the chance of cool nights in the SPI region, while no oscillations considered in this study increase the occurrence of low-temperature nights in SPI.

- The AMO diminishes the chances of achieving the maximum highest daily temperature.

- The NAO reduces the daily maximum temperature of SPI, while the ENSO increases the chances for one-day maximum rainfall in SPI.

- Overall, we concluded that the PDO and IOD must be given more importance when analyzing the correlations of climatic oscillations and ECOs across SPI.

- High-frequency IMFs (IMF1-3) showed variegated correlations and are downplayed by the presence of voids.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yan, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Yu, L. Biophysical feedback from earlier leaf-out enhances nonerosive precipitation in China. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.; Miao, C.; Gentine, P.; Mudryk, L.; Thackeray, C.W.; Berghuijs, W.R.; Wu, Y.; Fan, X.; Slater, L.; Sun, Q.; et al. Constrained Earth system models show a stronger reduction in future Northern Hemisphere snowmelt water. Nat. Clim. Change 2025, 15, 514–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Dai, A. Quantifying contributions of external forcing and internal variability to Arctic warming during 1900–2021. Earth’s Future 2024, 12, e2023EF003734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayathri, M.S.; Adarsh, S.; Shehinamol, K.; Nizamudeen, Z.; Lal, M.R. Evaluation of change points and persistence of extreme climatic indices across India. Nat. Hazards 2023, 116, 2747–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Alexander, L.; Hegerl, G.C.; Jones, P.; Tank, A.K.; Peterson, T.C.; Trewin, B.; Zwiers, F.W. Indices for monitoring changes in extremes based on daily temperature and precipitation data. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.-Clim. Change 2011, 2, 851–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.S.; Balling, R.C., Jr. Trends in extreme daily precipitation indices in India. Int. J. Climatol. 2004, 24, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, E.; Peterson, T.C.; Obando, P.R.; Frutos, R.; Retana, J.A.; Solera, M.; Soley, J.; García, I.G.; Araujo, R.M.; Santos, A.R.; et al. Changes in precipitation and temperature extremes in Central America and northern South America, 1961–2003. J. Geophys. Res. 2005, 110, D23107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Sun, Y. Characteristics of extreme temperature and precipitation in China in 2017 based on ETCCDI indices. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 2018, 9, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yosef, Y.; Aguilar, E.; Alpert, P. Is it possible to fit extreme climate change indices together seamlessly in the era of accelerated warming. Int. J. Climatol. 2021, 41, E952–E963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modaresi, F.; Danandeh Mehr, A.; Bajgiran, I.S.; Safari, M.J.S. Multi-level trend analysis of extreme climate indices by a novel hybrid method of fuzzy logic and innovative trend analysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaran, A.; Madhusudanan, S.G.; Ndehedehe, C.; Nair, A.N.G.R. Spatio-temporal Variability of Trends in Extreme Climatic Indices across India. KSCE J. Civil. Eng. 2024, 28, 2537–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaran, A.; Ahmed, A.N.; Elshafie, A.N.; Sherif, M.; Antony, A.M.; Anilkumar, K.; Raheena, L.N.; Purath, J.T. Deciphering the teleconnections of Extreme Temperature Indices with Local scale Meteorology using wavelet coherence. Phys. Chem. Earth 2025, 140, 104009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadgil, S.; Vinayachandran, P.N.; Francis, P.A.; Gadgil, S. Extremes of the Indian summer monsoon rainfall, ENSO and equatorial Indian Ocean oscillation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2004, 31, L12213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaran, A.; Reddy, M.J. Analyzing the Hydroclimatic Teleconnections of Summer Monsoon Rainfall in Kerala, India, Using Multivariate Empirical Mode Decomposition and Time-Dependent Intrinsic Correlation. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2016, 13, 1221–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adarsh, S.; Reddy, M.J. Links between global climate teleconnections and Indian monsoon rainfall. In Climate Change Signals and Response: A Strategic Knowledge Compendium for India; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi, B.; Vaheddoost, B.; Mehr, A.D. A spatiotemporal teleconnection study between Peruvian precipitation and oceanic oscillations. Quat. Int. 2020, 565, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrence, C.; Compo, G.P. A practical guide to wavelet analysis. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1998, 79, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Su, H.; Zio, E.; Zhang, Z.; Chi, L.; Fan, L.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, J. A data-driven approach to anomaly detection and vulnerability dynamic analysis for large-scale integrated energy systems. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 234, 113926. [Google Scholar]

- Kurths, J.; Agarwal, A.; Shukla, R.; Marwan, N.; Rathinasamy, M.; Caesar, L.; Krishnan, R.; Merz, B. Unravelling the spatial diversity of Indian precipitation teleconnections via a non-linear multi-scale approach. Nonlin. Proc. Geophys. 2019, 26, 251–266. [Google Scholar]

- Rathinasamy, M.; Agarwal, A.; Sivakumar, B.; Marwan, N.; Kurths, J. Wavelet analysis of precipitation extremes over India and teleconnections to climate indices. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2019, 33, 2053–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyan, A.V.S.; Ghose, D.K.; Thalagapu, R.; Guntu, R.K.; Agarwal, A.; Kurths, J.; Rathinasamy, M. Multiscale spatiotemporal analysis of extreme events in the Gomati River Basin, India. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourani, V.; Tootoonchi, R.; Andaryani, S. Investigation of climate, land cover and lake level pattern changes and interactions using remotely sensed data and wavelet analysis. Ecol. Inform. 2021, 64, 101330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, M.G.; Fathima, S.; Adarsh, S.; Baiju, N.; Nair, G.A.; Meenakshi, S.; Krishnan, M.S. Analyzing the streamflow teleconnections of greater Pampa basin, Kerala, India using wavelet coherence. Phys. Chem. Earth 2023, 131, 103446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Zio, E.; Zhang, J.; Xu, M.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z. A hybrid hourly natural gas demand forecasting method based on the integration of wavelet transform and enhanced Deep-RNN model. Energy 2019, 178, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, N.E.; Shen, Z.; Long, S.R.; Wu, M.C.; Shih, H.H.; Zheng, Q.; Yen, N.-C.; Chao, C.; Tung, C.C.; Liu, H.H. The empirical mode decomposition and the Hilbert spectrum for nonlinear and non-stationary time series analysis. Proc. R. Soc. London Ser. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 1998, 454, 903–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Someetheram, V.; Marsani, M.F.; Kasihmuddin, M.S.M.; Jamaludin, S.Z.M.; Mansor, M.A.; Zamri, N.E. Hybrid double ensemble empirical mode decomposition and K-Nearest Neighbors model with improved particle swarm optimization for water level forecasting. Alex. Eng. J. 2025, 115, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Huang, N.E. Ensemble empirical mode decomposition: A noise-assisted data analysis method. Adv. Adapt. Data Anal. 2009, 1, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, M.E.; Colominas, M.A.; Schlotthauer, G.; Flandrin, P. A complete ensemble empirical mode decomposition with adaptive noise. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Prague, Czech Republic, 22–27 May 2011; pp. 4144–4147. [Google Scholar]

- Colominas, M.A.; Schlotthauer, G.; Torres, M.E. Improved complete ensemble EMD: A suitable tool for biomedical signal processing. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2014, 14, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adarsh, S.; Plocoste, T.; Nourani, V. Application of Hilbert Huang Transform Framework for Characterizing the Multiscale Properties of Air Temperature in India over a Century. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2025, 182, 3341–3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wu, Z.; Huang, N.E. The time-dependent intrinsic correlation based on the empirical mode decomposition. Adv. Adapt. Data Anal. 2010, 2, 233–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Schmitt, F.G. Time dependent intrinsic correlation analysis of temperature and dissolved oxygen time series using empirical mode decomposition. J. Mar. Syst. 2014, 130, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashwini, K.; Pulak, G.; Savita, P.; Sulochana, G. Meteorological sub-divisions of India: Assessment of coherence, homogeneity and recommended redelineation. Mausam 2020, 71, 585–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adarsh, S.; Reddy, M.J. Multiscale characterization and prediction of monsoon rainfall in India using Hilbert–Huang transform and time-dependent intrinsic correlation analysis. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 2018, 130, 667–688. [Google Scholar]

- Adarsh, S.; Janga Reddy, M. Multiscale characterization and prediction of reservoir inflows using MEMD-SLR coupled approach. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2019, 24, 04018059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johny, K.; Pai, M.L.; Adarsh, S. Time-dependent intrinsic cross-correlation approach for multi-scale teleconnection analysis for monthly rainfall of India. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 2022, 134, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnell, Y. Relief and climate in South Asia: The influence of the western ghats on the current climate pattern of peninsular India. Int. J. Climatol. 1998, 17, 1169–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rilling, G.; Flandrin, P.; Gonçalves, P.; Lilly, J.M. Bivariate empirical mode decomposition. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2007, 14, 936–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, N.; Mandic, D.P. Empirical mode decomposition for trivariate signals. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2009, 58, 1059–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, N.; Mandic, D.P. Multivariate empirical mode decomposition. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2010, 466, 1291–1302. [Google Scholar]

- Yamuna, A.; Vyshnav, P.; Warrier, A.K.; Manoj, M.; Sandeep, K.; Kawsar, M.; Joju, G.; Sharma, R. Increasing frequency of extreme climatic events in southern India during the Late Holocene: Evidence from lake sediments. Quat. Int. 2024, 707, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, J.; Jha, S.; Goyal, M.K. On the relationship of climatic and monsoon teleconnections with monthly precipitation over meteorologically homogenous regions in India: Wavelet & global coherence approaches. Atmos. Res. 2020, 238, 104889. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, N.E.; Wu, Z. A review on Hilbert-Huang transform: Method and its applications to geophysical studies. Rev. Geophys. 2008, 46, RG2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, N.E.; Wu, Z.; Long, S.R.; Arnold, K.C.; Chen, X.; Blank, K. On instantaneous frequency. Adv. Adapt. Data Anal. 2009, 1, 177–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek, O.; Sankaran, A.; Şenol, H.İ. Multiscale investigations on RDI-SPI teleconnections of Çoruh and Aras Basins, Türkiye using time dependent intrinsic correlation. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2024, 136, 103787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valjarević, A.; Popovici, C.; Djekić, T.; Morar, C.; Filipović, D.; Lukić, T. Long-term monitoring of high optical imagery of the stratospheric clouds and their properties new approaches and conclusions. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2022, 25, 1037–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, S.; Wasko, C.; Peel, M.C. Atmospheric Rivers intensify extreme precipitation and flooding across Australia. Weather. Clim. Extrem. 2025, 50, 100812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Ke, C.-Q.; Cai, Y.; Li, H.; Xiao, Y.; Nourani, V.; Danandeh Mehr, A.; Sankaran, A. Abrupt decline and subsequent recovery of extreme precipitation associated with Atmospheric Rivers in the Southeastern Tibetan Plateau. Atmos. Res. 2025, 329, 108461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Index | Description |

|---|---|

| TX90p | Warm days |

| TN90p | Warm nights |

| TX10p | Cool days |

| TN10p | Cool night |

| TNn | Minimum of Tmin |

| TNx | Maximum of Tmin |

| TXn | Minimum of Tmax |

| TXx | Maximum of Tmax |

| DTR | Diurnal temperature range |

| Rx5 Day | Max 5-day precipitation |

| Rx1 Day | Max 1-day precipitation |

| Index | IMF1 | IMF 2 | IMF 3 | IMF 4 | IMF 5 | IMF 6 | IMF7 | IMF8/ Residue | IMF9/ Residue | IMF 10/ Residue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RX1Day | 0.446 | 0.614 | 0.585 | 0.067 | 0.057 | 0.055 | 0.068 | 0.044 | 0.031 | |

| RX5Day | 0.363 | 0.680 | 0.535 | 0.0588 | 0.0504 | 0.0318 | 0.0619 | 0.003 | −0.001 | 0.04 |

| TN90p | 0.452 | 0.498 | 0.467 | 0.355 | 0.339 | 0.273 | 0.0562 | 0.066 | 0.105 | |

| TNn | 0.309 | 0.459 | 0.233 | 0.154 | 0.083 | 0.118 | 0.120 | 0.054 | 0.078 | 0.085 |

| TNx | 0.48 | 0.851 | 0.127 | 0.063 | 0.041 | 0.0357 | 0.0154 | 0.01357 | ||

| TX90p | 0.520 | 0.398 | 0.486 | 0.376 | 0.298 | 0.212 | 0.164 | 0.121 | 0.312 | 0.294 |

| TXn | 0.406 | 0.671 | 0.613 | 0.091 | 0.066 | 0.077 | 0.022 | 0.031 | 0.096 | |

| TXx | 0.520 | 0.398 | 0.485 | 0.376 | 0.297 | 0.212 | 0.163 | 0.121 | 0.312 | 0.294 |

| DTR | 0.377 | 0.844 | 0.303 | 0.067 | 0.049 | 0.048 | 0.091 | 0.071 | 0.118 | |

| TN10p | 0.533 | 0.419 | 0.394 | 0.332 | 0.270 | 0.143 | 0.116 | 0.064 | 0.048 | |

| TX10p | 0.606 | 0.349 | 0.350 | 0.289 | 0.301 | 0.090 | 0.048 | 0.304 |

| Index | IMF | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 Residue | 9 Residue | |

| RX1 | 3.158 | 7.156 | 13 | 24.38 | 52 | 97.5 | 156 | 260 | 780 |

| RX5 | 3.49 | 7.96 | 13.93 | 26 | 48.75 | 86.67 | 195 | 260 | 390 |

| TN90p | 3.12 | 6.29 | 11.64 | 21.08 | 41.05 | 86.67 | 156 | 780 | |

| TNn | 3.64 | 10.68 | 12.19 | 20 | 41.05 | 70.91 | 130 | 260 | 780 |

| TNx | 4.51 | 11.14 | 11.64 | 26.90 | 65 | 195 | 390 | 780 | |

| TX90p | 3.25 | 6.046 | 11.64 | 21.08 | 37.14 | 65 | 111.429 | 260 | 780 |

| TXn | 3.35 | 7.22 | 13 | 24.38 | 48.75 | 78 | 156 | 260 | 780 |

| TXx | 3.88 | 10.99 | 17.33 | 32.5 | 70.91 | 78 | 390 | 780 | |

| DTR | 3.18 | 9.63 | 17.33 | 25.16 | 65 | 111.43 | 195 | 260 | |

| TN10p | 3.07 | 5.95 | 11.82 | 23.64 | 45.88 | 86.67 | 156 | 260 | 780 |

| TX10p | 3.07 | 5.95 | 11.82 | 23.64 | 45.8824 | 86.67 | 156 | 260 | 780 |

| Oscillation | Indices | CC | Oscillation | Indices | R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMO | RX1 | 0.112 | NAO | RX1 | −0.044 |

| RX5 | 0.105 | RX5 | −0.048 | ||

| DTR | −0.114 | DTR | 0.060 | ||

| TN10p | −0.089 | TN10p | 0.006 | ||

| TN90p | 0.096 | TN90p | 0.034 | ||

| TNn | −0.023 | TNn | −0.034 | ||

| TNx | 0.093 | TNx | −0.084 | ||

| TX10p | −0.068 | TX10p | 0.070 | ||

| TX90p | 0.024 | TX90p | −0.003 | ||

| TXn | 0.029 | TXn | −0.044 | ||

| TXx | 0.027 | TXx | −0.055 | ||

| ENSO | RX1 | 0.017 | PDO | RX1 | −0.794 |

| RX5 | −0.016 | RX5 | 0.950 | ||

| DTR | 0.023 | DTR | 0.033 | ||

| TN10p | −0.241 | TN10p | −0.017 | ||

| TN90p | 0.237 | TN90p | 0.017 | ||

| TNn | 0.015 | TNn | 0.185 | ||

| TNx | 0.012 | TNx | 0.149 | ||

| TX10p | −0.270 | TX10p | 0.074 | ||

| TX90p | 0.222 | TX90p | −0.086 | ||

| TXn | 0.066 | TXn | −0.390 | ||

| TXx | 0.037 | TXx | 0.179 | ||

| IOD | RX1 | −0.077 | |||

| RX5 | −0.091 | ||||

| DTR | 0.159 | ||||

| TN10p | −0.034 | ||||

| TN90p | 0.148 | ||||

| TNn | −0.037 | ||||

| TNx | −0.040 | ||||

| TX10p | −0.149 | ||||

| TX90p | 0.169 | ||||

| TXn | 0.076 | ||||

| TXx | 0.048 |

| AMO | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | Residue | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TN10P | ||||||||||

| 1 | 0.072 | −0.011 | 0.017 | −0.01 | −0.013 | −0.006 | 0.019 | −0.011 | 0.007 | |

| 2 | −0.026 | 0.109 | 0.041 | −0.047 | −0.039 | −0.008 | −0.002 | −0.009 | −0.004 | |

| 3 | 0.026 | 0.032 | −0.048 | −0.125 | 0.012 | 0.023 | −0.005 | 0.001 | −0.002 | |

| 4 | −0.015 | −0.008 | −0.016 | −0.124 | −0.054 | −0.054 | −0.015 | −0.024 | −0.001 | |

| 5 | −0.005 | 0.002 | −0.007 | −0.155 | −0.432 | −0.056 | 0.05 | 0.088 | 0.012 | |

| 6 | 0.017 | 0.009 | −0.015 | −0.067 | −0.071 | 0.126 | −0.212 | −0.064 | 0.022 | |

| 7 | −0.027 | 0.002 | 0.042 | −0.036 | −0.065 | 0.035 | −0.425 | −0.469 | 0.356 | |

| 8 | −0.018 | 0.008 | 0.023 | −0.021 | −0.052 | 0.042 | −0.124 | 0.06 | 0.074 | |

| 9 | 0.041 | 0.003 | −0.021 | −0.009 | 0.048 | 0.161 | −0.037 | 0.017 | −0.878 | |

| ENSO | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | Residue | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TN10P | ||||||||||

| 1 | 0.031 | −0.064 | 0.049 | −0.018 | 0.003 | −0.008 | 0.016 | 0.001 | 0.026 | |

| 2 | −0.007 | 0.008 | 0.124 | −0.029 | −0.003 | 0.009 | 0.006 | 0.007 | −0.001 | |

| 3 | 0.007 | 0.001 | 0.016 | −0.406 | −0.002 | 0.02 | −0.009 | 0.039 | 0.003 | |

| 4 | 0.012 | −0.005 | −0.039 | −0.211 | −0.42 | −0.187 | 0.096 | 0.163 | 0.162 | |

| 5 | −0.012 | 0.001 | −0.001 | −0.078 | −0.241 | −0.052 | −0.007 | −0.005 | −0.025 | |

| 6 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.022 | 0.051 | 0.139 | −0.182 | −0.075 | −0.141 | −0.089 | |

| 7 | 0.013 | −0.006 | 0.004 | 0.012 | 0.114 | 0.138 | −0.487 | −0.561 | −0.092 | |

| 8 | −0.004 | −0.002 | −0.037 | −0.029 | −0.109 | −0.041 | 0.238 | −0.303 | 0.096 | |

| 9 | 0.042 | 0.003 | −0.018 | −0.013 | 0.034 | 0.147 | −0.016 | 0.045 | −0.886 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Danandeh Mehr, A.; Ajith, A.; Sankaran, A.; Maghrebi, M.; Tur, R.; Saji, A.S.; Nizar, A.; Pottayil, M.N. A Time-Dependent Intrinsic Correlation Analysis to Identify Teleconnection Between Climatic Oscillations and Extreme Climatic Indices Across the Southern Indian Peninsula. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 1395. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121395

Danandeh Mehr A, Ajith A, Sankaran A, Maghrebi M, Tur R, Saji AS, Nizar A, Pottayil MN. A Time-Dependent Intrinsic Correlation Analysis to Identify Teleconnection Between Climatic Oscillations and Extreme Climatic Indices Across the Southern Indian Peninsula. Atmosphere. 2025; 16(12):1395. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121395

Chicago/Turabian StyleDanandeh Mehr, Ali, Athira Ajith, Adarsh Sankaran, Mohsen Maghrebi, Rifat Tur, Adithya Sandhya Saji, Ansalna Nizar, and Misna Najeeb Pottayil. 2025. "A Time-Dependent Intrinsic Correlation Analysis to Identify Teleconnection Between Climatic Oscillations and Extreme Climatic Indices Across the Southern Indian Peninsula" Atmosphere 16, no. 12: 1395. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121395

APA StyleDanandeh Mehr, A., Ajith, A., Sankaran, A., Maghrebi, M., Tur, R., Saji, A. S., Nizar, A., & Pottayil, M. N. (2025). A Time-Dependent Intrinsic Correlation Analysis to Identify Teleconnection Between Climatic Oscillations and Extreme Climatic Indices Across the Southern Indian Peninsula. Atmosphere, 16(12), 1395. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121395