Abstract

A series of multi-parameter, multi-layer observations was conducted to study possible electromagnetic precursors associated with the M 6.7 earthquake that struck Iburi, Hokkaido, Japan, at 18:07:59 UT on 5 September 2018. The most significant observation is seismogenic lower-ionospheric perturbations in the propagation anomalies of sub-ionospheric VLF/LF signals recorded in Japan and Russia. Other substantial observations include the GIM-TEC irregularities, the intensification of stratospheric atmospheric gravity waves (AGWs), and the satellite and ground monitoring of air temperature (T), relative humidity (RH), atmospheric chemical potential (ACP), and surface latent heat flux (SLHF). We have found that there were very remarkable VLF/LF anomalies indicative of lower-ionospheric perturbations observed on 4 and 5 September just before the EQ date and even after it from the observations in Japan and Russia. In particular, the anomaly was detected for a particular propagation path from the JJY transmitter (Fukushima) to a VLF station at Wakkanai one day before the EQ, i.e., on 4 September, and is objectively confirmed by machine/deep learning analysis. An anomaly in TEC occurred only on 5 September, but it is unclear whether it is related to a pre-EQ effect or a minor geomagnetic storm. We attempted to determine whether any seismo-related atmospheric gravity wave (AGW) activity occurred in the stratosphere. Although numerous anomalies were detected, they are most likely associated with convective weather phenomena, including a typhoon. Finally, the Earth’s surface parameters based on satellite monitoring seem to indicate some anomalies from 29 August to 3, 4, and 5 September, a few days prior to EQ data, but the ground-based observation close to the EQ epicenter has indicated a clear T/RH and ACP on 2 September with fair weather, but no significant data on subsequent days because of severe meteorological activities. By integrating multi-layer observations, the LAIC (lithosphere–atmosphere–ionosphere coupling) process for the Hokkaido earthquake appears to follow a slow diffusion-type channel, where ionospheric perturbations arise a few days after ground thermal anomalies. This study also provides integrated evidence linking concurrent lower-ionospheric, atmospheric, and surface thermal anomalies, emphasizing the diagnostic value of such multi-parameter observations in understanding EQ-associated precursor signatures.

1. Introduction

It is increasingly accepted that electromagnetic phenomena occur not only in the lithosphere but also in the atmosphere and ionosphere prior to earthquakes (EQs) [1,2,3,4,5,6]. The ionosphere is notably sensitive to pre-earthquake lithospheric disturbances, producing detectable perturbations in the lower ionosphere, as revealed through sub-ionospheric VLF/LF propagation measurements [7,8,9,10]. Similar variations occur in the upper F-region, as revealed by ionosonde data and GPS-based total electron content (TEC) measurements [1,2,3,4,5,6,11,12], usually appearing a few days to about a week before large earthquakes. Furthermore, the successful launch of the French satellite DEMETER in 2004, designed specifically for seismo-ionospheric investigations [13], marked a significant milestone and inspired many follow-up studies using various satellites, such as Swarm and China Seismo-Electromagnetic Satellite (CSES). The central scientific issue concerns the mechanisms through which the ionosphere becomes coupled to pre-earthquake lithospheric processes, an interaction conceptualized within the LAIC framework [14,15,16]. Over the past decade, numerous studies have examined LAIC, primarily through simultaneous observations of ionospheric parameters and surface-level geophysical or atmospheric variables [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. However, only a limited number of investigations have addressed the critical intermediate layers, namely the lower ionosphere and the stratosphere, where key energy transfer processes are believed to occur [23,24,30,31]. Although substantial progress has been made, the underlying physical mechanisms governing LAI coupling remain insufficiently resolved and require further comprehensive investigation.

Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the LAIC processes. One of the most widely discussed frameworks is the chemically and electrically mediated mechanism [2,42,43,44], in which increased radon emanation enhances atmospheric ionization, modifies near-surface conductivity, and perturbs the atmospheric electric field, eventually influencing ionospheric electron density. A related model, the electrostatic mechanism, proposes that tectonic stress activates positive hole charge carriers in rocks, leading to the formation of strong electric fields at the surface [45]. Although these models differ in their triggering processes (radon release versus stress-activated charge carriers), both fundamentally rely on the generation of upward-propagating electric fields. However, near-surface electric fields are typically too weak and spatially confined to penetrate the conductive lower atmosphere, and the timing of radon or stress activation is highly variable; moreover, the absence of high-resolution radon observations complicates empirical validation [46]. Kuo et al. (2011) [47] extended this approach by introducing an additional vertical atmospheric current based on the assumption that crustal conductivity increases significantly due to stress-activated positive holes [45], but this assumption is difficult to justify. Laboratory results indicate that such conductivity enhancements are highly localized and transient, and they do not scale to crustal dimensions where rocks remain dominantly resistive and lack continuous conductive pathways capable of sustaining large electric currents [48,49,50]. To address these limitations, Sorokin et al. [5,51] introduced an alternative formulation incorporating electromotive forces generated by the upward flux of charged aerosols.

A conceptually different mechanism is the atmospheric gravity wave (AGW) hypothesis [3,9,10,52,53,54], which posits that pre-seismic releases of gas, water vapor, or radon can generate AGWs in the lower atmosphere. These waves may propagate upward and obliquely, transferring energy and momentum into the lower ionosphere and producing detectable perturbations. Substantial indirect observational evidence supporting AGW involvement in LAI coupling has been reported in multiple studies [55,56,57,58], with a comprehensive summary provided in [56]. There has been continued debate regarding the AGW hypothesis, especially due to limited observational constraints on the potential near-surface excitation mechanisms. Our recent studies have presented evidence suggesting AGW generation and upward propagation in the stratosphere (15–50 km altitude), based on analyses of temperature profiles related to the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake [57].

Recently, Hayakawa and Hobara (2024) [30] summarized the LAIC channel for a particular EQ, and based on different EQ precursory impressions observed by different groups, they have concluded that there are two possible channels: one is called “fast” channel, and the other is “slow” channel. Fast channel is characterized by the observational facts that the ionospheric perturbation takes place nearly synchronously (of the order of within one day) with those on the Earth’s surface perturbation. The mechanism involved in this channel may be either chemical or acoustic channel, but there have been no definite observational evidence published in support of any one of those hypotheses. The slow channel involves a sequence of interconnected processes in which an initial disturbance triggers a chain of subsequent anomalies. In this mechanism, ionospheric disturbances emerge several days later, reflecting a diffusion-like delay following the initial perturbations at the Earth’s surface or in the lithosphere. The underlying process, however, remains poorly understood. In order to elucidate or better understand the mechanism of LAI coupling, we will pay a lot of attention to the intermediate regions such as the lower ionosphere and stratosphere (upper atmosphere) in the LAIC studies. It is highly required for us to accumulate case studies, like performed in [23,24,30,31], for any other EQs, and this paper will deal with a rather big 2018 Hokkaido Iburi EQ (we call it Hokkaido EQ hereafter). We already published some preliminary results [59], but in this paper, we have extended those results very much, such as the inclusion of application of AI (artificial intelligence) to our VLF data and we have also included the satellite monitoring and ground-based AMeDAS (Automated Meteorological Data Acquisition System) observation on the Earth’s surface information (T, RH, ACP, and SLHF) in order to increase the information for better understanding the coupling between the lithosphere and ionosphere.

2. Data and Methods

To investigate possible lithosphere–atmosphere–ionosphere coupling (LAIC) associated with the 2018 Hokkaido earthquake, we employ an integrated multi-parameter analysis. We first examine lower-ionospheric responses using sub-ionospheric VLF/LF propagation and validate these using an AI-based detection model. We then assess corresponding upper-ionospheric behavior via TEC, and analyze stratospheric gravity waves and surface thermal–humidity fields to identify intermediate atmospheric processes. This unified workflow allows us to explore a physically coherent LAIC scenario across multiple atmospheric layers.

2.1. EQ Treated in This Paper

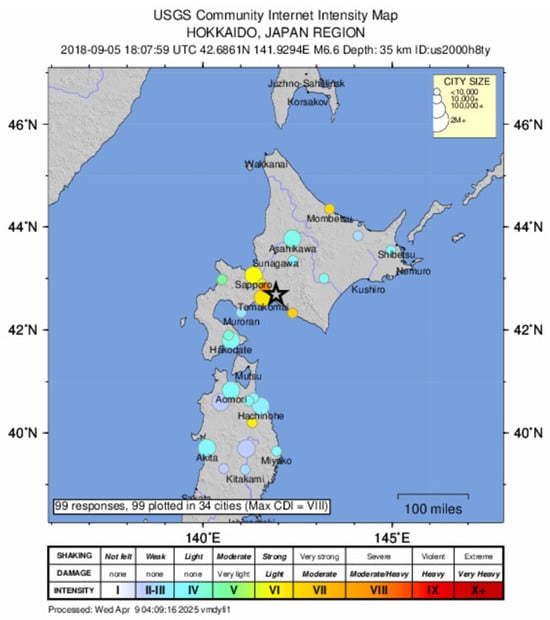

A large EQ happened in the Hokkaido Island at 3 h 7 m 59 s JST on 6 September 2018 (18:07:59 UT on 5 September 2018) with epicenter at 42.69° N, 142.01° E, as shown in Figure 1. The geomagnetic latitude and longitude of the epicenter were around 37° N and 135° E. Its magnitude (M) was 6.7, and its depth was 37 km. Focal mechanism analyses suggest that the rupture occurred either along a moderately dipping reverse fault striking northward or along a shallow to moderately dipping fault striking southeast. Considering both the depth and the focal mechanism, this earthquake most likely originated within the upper portion of the North American Plate rather than along the subduction interface between the Pacific and North American plates, which lie at approximately 100 km depth in this region. Despite its moderate magnitude, the seismic intensity reached a maximum level of 7, the highest ever recorded in Hokkaido.

Figure 1.

Location of Hokkaido Iburi EQ (abbreviated as Hokkaido EQ) indicated by a black star. Tomakomai is one AMeDAS meteorological station close to the EQ epicenter (which will be presented later) is also indicated.

2.2. Solar–Terrestrial Conditions

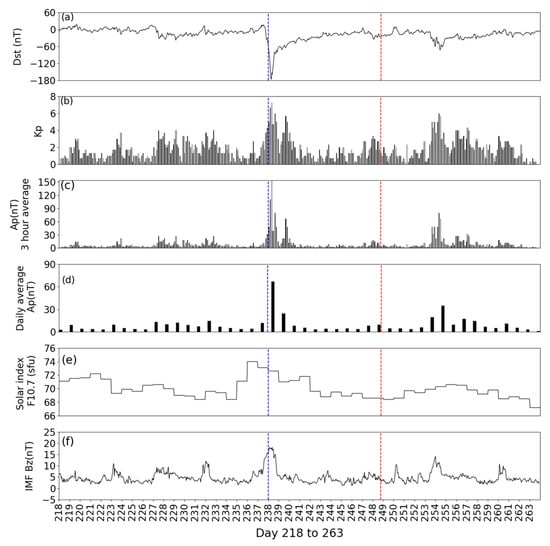

Figure 2 illustrates the solar–terrestrial conditions just around the EQ. The top four panels correspond to the temporal variation in geomagnetic activity (from the top, Dst (in nT), Kp index, and Ap index (in nT) (3 h averages and daily averages), and then solar flux variation, f10.7 and finally IMF (interplanetary magnetic field) Bz (in nT). The geomagnetic data indicate a clear storm event around (Day of the Year) DOY 238–239, during which the Dst index dropped sharply to approximately −150 nT, the Kp index peaked at 6–7, and the 3 h Ap index reached roughly 120 nT, with the daily Ap averaging around 70–80 nT. The IMF Bz component turned strongly southward to about −20 nT. At the same time, the solar F10.7 flux remained stable at around 72–74 sfu, confirming that the storm was driven by solar wind–magnetosphere interaction rather than a change in solar radiation. By contrast, at the time of the Hokkaido earthquake (DOY 248), the geomagnetic field had returned to quiet conditions, with Dst around −25 nT, Kp ≈ 1–2, Ap < 10 nT, and Bz varying mildly between +5 and −5 nT. Typically, storm conditions are considered for Dst ≤ −50 nT, Kp ≥ 5, ap, Ap ≥ 30. Thus, the values indicate that the EQ occurred during a geomagnetically quiet period, several days after the recovery from the preceding storm. Therefore, approximately one week before the EQ, the geomagnetic environment was relatively quiet.

Figure 2.

Solar–terrestrial conditions around the EQ date. The top four panels indicate the temporal evolutions of geomagnetic activity (a) Dst (in nT), (b) Kp index, (c) Ap index (3 h averages) (d) Ap index (daily averages), (e) solar flux radiation (f10.7) and finally (f) IMF (in nT), Bz (in nT). EQ day (DOY249) (5 September) is indicated by a vertical red line.

2.3. The Multi-Parameters Used for This EQ

In our multi-parametric and multi-layer approach, we first target the parameter that is most diagnostic in our dataset—anomalous sub-ionospheric VLF/LF signal propagation, interpreted as a lower-ionospheric response to seismogenic forcing. We quantify path-amplitude and phase departures using a conventional statistical filter (time-of-day referenced mean and standard deviation over a quiet-day baseline) to flag deviations that exceed empirical limits (e.g., >2–3σ), while masking intervals affected by geomagnetic storms or severe weather. To objectively validate these visually apparent departures, we then apply AI methods (supervised and unsupervised machine/deep learning models) trained on labeled “quiet” versus “disturbed” segments from multiple transmitter–receiver paths; model outputs (anomaly scores or class probabilities) provide path-independent confirmation and reduce operator bias. After establishing the lower-ionospheric disturbance, we examine the upper-ionospheric state using GPS TEC as a proxy for F-region plasma content, assessing whether event–time TEC perturbations (maps and slant-TEC along relevant great-circle arcs) are temporally consistent with the VLF/LF anomalies and not attributable to geomagnetic drivers. In parallel, we probe the middle-atmosphere link by detecting atmospheric gravity wave (AGW) fluctuations in ERA5 temperature fields (stratospheric bands where AGWs are best expressed), using band-pass filtering and background removal to isolate wave-like perturbations and compare their timing with the ionospheric signals. Finally, to evaluate a plausible near-surface driver in the LAIC chain, we analyze satellite-derived surface parameters—air temperature (T), relative humidity (RH), atmospheric chemical potential (ACP), and surface latent heat flux (SLHF)—for spatially coherent, short-lived anomalies over and around the epicentral region; these are complemented by ground observations of T/RH and ACP from a station near the epicenter (Tomakomai). The combined surface–stratosphere–ionosphere view enables us to test a diffusion-type LAIC scenario, in which shallow thermal/chemical perturbations—potentially linked to radon emanation or stress-activated processes—modulate atmospheric conductivity and circulation, seed AGWs, and ultimately imprint on the lower and upper ionosphere as the observed VLF/LF and TEC anomalies.

2.4. Investigation of Lower-Ionospheric Perturbations Through Sub-Ionospheric VLF/LF Signal Propagation Analysis

We have been continuously monitoring lower-ionospheric perturbations (e.g., [3,4,10]) using our Japanese VLF/LF Hi-SEM network, which consists of approximately ten receiving stations distributed across Japan. Each station is equipped with a standardized receiving system comprising VLF and GPS antennas, a preamplifier, a VLF receiver, a sound card, and dedicated signal-processing software. Detailed descriptions of the instruments and system configuration are provided in [8,9,10]. The details of the instruments are not given here to avoid redundancy. Every site in the network simultaneously records sub-ionospheric signals transmitted from two Japanese VLF/LF transmitters, JJY in Fukushima (40 kHz) and JJI in Miyazaki (22.2 kHz), as well as from three international transmitters: NLK (Jim Creek, Arlington, TX, USA), NPM (Hawaii, HI, USA), and NWC (Western Australia, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia). Among the various observation sites, the Wakkanai (WKN) station, located in northern Hokkaido (45.52° N, 141.95° E), was selected for this study because of its favorable position for propagation path analysis, as illustrated in Figure 1.

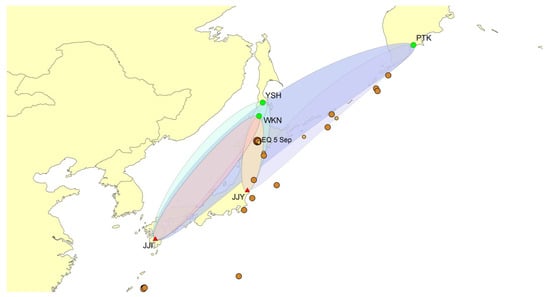

Our Russian collaborators have operated similar VLF/LF monitoring systems at two stations—Petropavlovsk-Kamchatka (PTK; 53.09° N, 158.55° E) and Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk (YHS; 46.95° N, 142.75° E)—using instrumentation nearly identical to that of our Japanese network. Figure 3 presents the geographic layout of the two Japanese transmitters (JJY and JJI; red triangles), the relevant receiving stations (WKN, PTK, and YHS), and all earthquakes (M ≥ 5) that occurred in August and September 2018. The target event—the 5 September 2018 Hokkaido earthquake—is highlighted on the map, and the Fresnel zones corresponding to different propagation paths are shown as ellipses. The Fresnel zone is defined by the region around the direct propagation path where most of the transmitted energy travels, and its radius can be approximated a y ≈ [(λx(l − x))/D + (λ2/4)]1/2, where λ is the wavelength, x is the position along the path, l is the total path length, and D is the transmitter–receiver distance. Due to unfavorable signal conditions at YHS during this period, the Fresnel zones for the JJY–YHS and JJI–YHS paths are not plotted. EQs with magnitudes greater than 5 that occurred during August and September 2018 are also plotted, with symbol size proportional to magnitude. The main EQ of interest is marked with EQ 5 September.

Figure 3.

The map displays the locations of two Japanese transmitters JJY (Fukushima) and JJI (Miyazaki) marked by red triangles, along with the VLF/LF observation stations: Wakkanai (WKN) in Japan, and Petropavlovsk-Kamchatka (PTK) and Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk (YHS) in Russia, shown as green circles. The corresponding Fresnel zones for the propagation paths JJY–WKN, JJI–WKN, JJY–PTK, and JJI–PTK are represented by ellipses. EQs with magnitudes greater than 5 that occurred during August and September 2018 are also plotted, with symbol size proportional to magnitude. The main EQ of interest is marked with EQ 5 September.

In this analysis we compute the conventional and well-used parameter “Trend”. The trend is defined as the deviation in the average nighttime VLF/LF signal amplitude from its long-term mean, expressed in normalized units. Specifically, for each day, the average nighttime amplitude is compared against the mean value calculated over the preceding one-month reference period, and the difference is then normalized by the corresponding standard deviation (σ) of that same period. This normalization effectively transforms the amplitude variation into a dimensionless measure of relative anomaly, allowing consistent comparison across different time intervals and signal paths. A positive or negative trend value therefore indicates whether the nighttime amplitude is unusually enhanced or depleted relative to the expected monthly baseline.

2.5. Application of AI (Machine/Deep Learning)

We have conducted a machine/deep learning analysis using the Nonlinear Auto-regressive Moving Average with eXogenous inputs (NARMAX (e.g., [60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67]) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) [68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83] for the same data. This is an upgraded method, nearly the same as NARX, but improved as in Hayakawa et al. (2025) [84]. Here we will repeat only the essential points for this study. Although both models have been widely applied in previous studies, they have typically been used independently. In this paper, we propose a combined application of the NARMAX and LSTM models, a promising approach in the field of artificial intelligence that offers strong potential for time series forecasting. By integrating the strengths of both methods, the combined model can achieve higher predictive accuracy. Specifically, the LSTM model excels at learning long-term dependencies, making it particularly effective for capturing relationships between data points separated in time—for instance, when patterns from the distant past influence future outcomes. On the other hand, NARMAX is a self-regressive model with external inputs, good at capturing short-term changes and clear causal relations by taking advantage of the fact that the current output depends on the past output and external inputs. NARMAX explicitly handles past data, while LSTM implicitly remembers features. This may improve feature selection and model interpretability.

A hybrid NARMAX–LSTM model was developed to capture nonlinear dependencies between geophysical drivers and ionospheric responses. Both exogenous features (e.g., Dst, Kp, IMF, F10.7) and autoregressive/difference features representing AR/MA dynamics were fed into a bidirectional LSTM network, followed by a fully connected output layer to generate a single predicted variable. The model was implemented in PyTorch (nn.LSTM(..., bidirectional = True) → nn.Linear) (https://pytorch.org/ used on 10 January 2025) and optimized using the Adam algorithm with mean squared error (MSE) as the loss function. Hyper-parameters were tuned through Optuna, exploring sequence lengths (5–30), hidden units (1–40), LSTM layers (1–20), and learning rates (10−5–10−1, log-uniform). Training proceeded for a maximum of 100 epochs with a batch size of 16.

The input features combined exogenous drivers and autoregressive terms [Dst, Kp, IMF, F10.7, Value1_lag1–2, error_lag1–2, diff1–4]. Data preprocessing involved replacing missing values (999.9) via linear interpolation, applying Min–Max normalization on training data only, and maintaining temporal integrity across splits: training (1 May 2017–30 April 2018), validation (1 May 2018–30 June 2018), and testing (1 August 2018–31 October). Model selection relied on validation MSE with early stopping after 25–50 stagnant epochs. The best configuration achieved a validation MSE ≈ 0.01076.

Performance on unseen data yielded MAE = 0.0782 and RMSE = 0.1036 (MSE ≈ 0.01073) in normalized space, showing consistent generalization across validation and test sets. Overfitting control was ensured through early stopping and constrained model capacity rather than dropout, which can impair temporal learning in LSTMs. For anomaly detection, residuals were evaluated within a rolling Bollinger band threshold (mean ± kσ, k = 2, 3; window = 40 samples). Incorporating space–weather indices as exogenous inputs further reduced false detections, ensuring the model’s residual anomalies corresponded primarily to seismogenic or non-magnetic influences.

One advantage of NARMAX is its ability to directly include external inputs, such as geomagnetic activity (Dst, Kp) and solar radiation flux (f10.7), which are factors that could influence the forecast target. We then apply Bollinger band analysis [85] to identify anomalies related to earthquakes. To improve the model’s accuracy, we optimize hyper-parameters, such as the number of LSTM units and delays in NARMAX, using the Optuna method [86]. The model’s performance is evaluated after training through metrics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Mean Squared Error (MSE).

In this study, we compute the residuals, which are the differences between observed values and those predicted by the combined NARMAX/LSTM model. Using Bollinger band analysis on the geophysical data helps us identify abnormal fluctuations and sudden events more clearly. We have prepared the time series data of daily nighttime average amplitude such as follows. The time series data of nighttime average amplitude data from 1 May 2017 to 30 April 2018 are used as training data, then the data during the period from 1 May 2018 to 30 June 2018 are used as validation data, and finally the period from 1 August to 31 October 2018 is the test data, which is our prediction target period.

2.6. Investigation of Ionospheric TEC

We next examine the behavior of electron density perturbations in the upper ionosphere, focusing on the F-region, where variations in plasma concentration can provide valuable insight into pre-seismic ionospheric responses. TEC is employed as the primary diagnostic parameter, representing the line-integrated electron density along the ray path between a GNSS satellite and a ground-based receiver. Owing to its high temporal resolution, global coverage, and accessibility from multiple international data repositories, TEC remains one of the most robust metrics for assessing ionospheric variability. In this study, we utilize the Global Ionosphere Map (GIM) produced by the Center for Orbit Determination in Europe (CODE), which assimilates dual-frequency GNSS measurements from a dense global network of receivers using spherical harmonic modeling and interpolation techniques. The CODE GIM provides global vertical TEC (VTEC) values at a spatial resolution of 5° in longitude and 2.5° in latitude, with a temporal cadence of one hour. The dataset, distributed in IONEX format, contains both absolute VTEC values and associated model error estimates, allowing quantitative evaluation of anomaly significance. Following the procedure described by Schaer (1999) [87], the GIM is generated by first converting dual-frequency GNSS phase and pseudorange data into slant TEC (STEC) values through the relation STEC = (f12f22/(f12 − f22)) × (ΔP12/40.3), where f1 and f2 are the carrier frequencies (Hz) and ΔP12 is the ionospheric delay (m). The STEC observations are then mapped to a thin-shell model at approximately 450 km altitude using the standard mapping function VTEC = STEC × cos(E′), where E′ is the zenith angle at the ionospheric pierce point. The resulting VTEC values are represented globally using a spherical harmonic expansion, VTEC(φ, λ, t) = Σn=0N Σm=0n (Anm cos mλ + Bnm sin mλ) Pnm(sin φ), where (φ, λ) are the geographic latitude and longitude, Pnm are the associated Legendre functions, and Anm, Bnm are the harmonic coefficients estimated through least-squares adjustment. This spherical harmonic representation allows for the reconstruction of the global ionospheric structure and its temporal evolution, while the interpolation process minimizes data gaps and ensures smooth spatial continuity. Together, these procedures enable high-fidelity monitoring of ionospheric behavior, providing a physically consistent framework for detecting transient electron density perturbations that may be associated with lithospheric- or atmospheric-forcing mechanisms.

2.7. Investigation of Stratospheric AGW

Atmospheric gravity wave (AGW) activity in the stratosphere was analyzed using temperature profiles derived from ERA5 reanalysis data provided by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF). The ERA5 dataset, with a spatial resolution of 1° × 1° and a temporal resolution of 6 h, was extracted over the earthquake’s epicentral region for altitudes between 15 and 50 km. To isolate small-scale wave perturbations, the temperature perturbation was obtained by subtracting a vertically smoothed background temperature from the original ERA5 temperature profile , i.e., . The smoothing was performed over a 10–15 km vertical window to remove synoptic-scale variations and retain mesoscale gravity wave fluctuations. The background atmospheric stability was then characterized by calculating the Brunt–Väisälä frequency , which defines the restoring force acting on vertically displaced air parcels and governs gravity wave propagation. It is expressed as , where is gravitational acceleration and is the potential temperature, with , the gas constant, and the specific heat at constant pressure. The potential energy per unit mass associated with AGWs, a measure of wave intensity, was then computed using . Enhanced values of indicate stronger wave activity, allowing identification of periods with elevated gravity wave energy possibly related to seismo-atmospheric or convective processes. Finally, the temporal and vertical variations of were visualized as altitude–time cross sections to assess the evolution of AGW activity above the epicentral area, following the analytical approach [88,89].

2.8. Investigation of Thermal Parameters

Satellite and reanalysis monitoring were conducted to investigate Earth’s surface parameters, namely air temperature (T), relative humidity (RH), atmospheric chemical potential (ACP), and surface latent heat flux (SLHF) [20,21,22,25,27,28]. The principal physical mechanism underlying these thermal anomalies involves the release of latent heat during the condensation of water vapor onto ions generated by the ionization of atmospheric gases, primarily induced by radon emanation from the lithosphere [2,3,5,84,90,91]. The analysis employed the NCEP/NCAR Reanalysis dataset from the NOAA Physical Sciences Laboratory (https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded accessed on 10 January 2025), which reconstructs the global atmospheric state by assimilating multi-source observations with numerical weather prediction outputs. The reanalysis provides global fields at 2.5° × 2.5° spatial resolution at four synoptic times per day (00, 06, 12, and 18 UTC). Daily averages of T, RH, and SLHF were derived by integrating these six-hourly data. The study domain extended from 32° N to 52° N and 131° E to 151° E, encompassing the Hokkaido earthquake epicentral region. After downloading the relevant variables in NetCDF format, data were converted into CSV files, and the 15 days surrounding the earthquake were extracted for analysis. The atmospheric chemical potential (ACP) was calculated from surface temperature and humidity as ΔU = 5.8 × 10−10 (20T + 5463)2 ln(100/RH) [92]. This formulation quantifies the thermodynamic energy potential of moist air and reflects the latent heat released during condensation in an ionized atmosphere, making it a sensitive indicator of pre-seismic thermodynamic perturbations. To emphasize seismically associated variations, a residual analysis was performed by subtracting the mean values from the same period in 2017 and 2019 from those in 2018, expressed as ΔX = X2018 − ⟨X2017,2019⟩. Finally, daily spatiotemporal maps of T, RH, ACP, and SLHF were generated to visualize the evolution of atmospheric anomalies and to identify potential pre-seismic thermodynamic responses.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Lower-Ionospheric Perturbation, VLF/LF Fluctuations

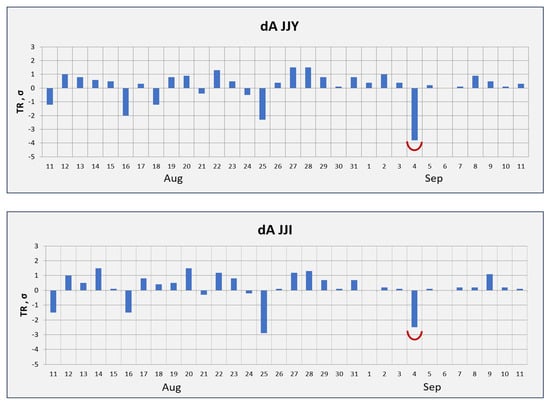

Figure 4 illustrates the VLF/LF propagation characteristics observed at WKN for the two propagation paths of JJY-WKN and JJI-WKN. Both panels refer to the results of “Trend”.

Figure 4.

Propagation characteristics at Wakkanai (WKN) within one month before and after the earthquake. The upper and lower panels show the JJY and JJI paths, respectively. Each plot presents the normalized nighttime amplitude deviation (dA/σ) from the monthly mean (“Trend”), where anomalies are defined by depletions exceeding –2σ.

The period of analysis covers VLF/LF data for about one month surrounding the earthquake. As reported by Hayakawa et al. [8,10], seismogenic VLF/LF anomalies are typically marked by amplitude depletions greater than −2σ. In this study, the JJY–WKN propagation path exhibited a clear amplitude decrease exceeding −3σ (−3.5σ) on 4 September (UT), one day before the earthquake. A corresponding but weaker anomaly, just above −2σ, was also observed along the JJI–WKN path on the same day. These concurrent anomalies likely share a common seismogenic source. The stronger depletion on the JJY–WKN path can be attributed to its closer proximity to the earthquake epicenter, which lies within its Fresnel zone (Figure 3). In contrast, the broader earthquake preparation zone [93] extended to the JJI–WKN path, producing a less pronounced anomaly. Another significant anomaly on 25 August was observed at both propagation paths of JJY-WKN and JJI-WKN, which is definitely of the origin of a rather big geomagnetic storm as seen from Figure 2.

The simultaneous occurrences of statistically significant amplitude decreases on both the JJY–WKN and JJI–WKN paths, which intersect the seismo-active region within their respective Fresnel zones, indicate that the perturbation originated within a common ionospheric volume above the impending epicentral area. Given the distinct transmitter frequencies and propagation azimuths, such coherent anomalies cannot be attributed to transmitter instability, diurnal variations, or meteorological disturbances, all of which would affect the paths independently. The spatial overlap of the perturbed zones and their timing within the pre-seismic window strongly support a localized seismogenic coupling mechanism affecting the lower ionosphere above the source region.

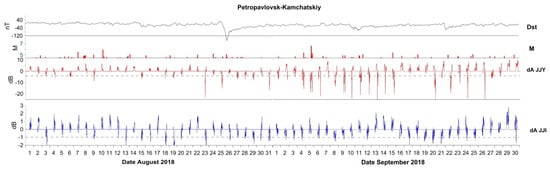

The VLF/LF outcomes from the Russian observation show that only the nighttime amplitude is presented in each hour in Figure 5 as observed at PTK, and Figure 6 shows the corresponding results at YSH. The bottom subpanels of Figure 5 illustrate the nighttime amplitude, dA(t): The upper and lower panels correspond to the JJY–PTK and JJI–PTK propagation paths, respectively. Horizontal dotted lines in both panels mark the −2σ threshold. For reference, the top subpanel in each figure shows geomagnetic activity (Dst index), while the bottom subpanel shows earthquake occurrences, as in Figure 3. Geomagnetic conditions were relatively quiet from early to late August, but became disturbed toward the end of August and into September due to several geomagnetic storms. Along the JJY–PTK path, a distinct anomaly exceeding −2σ was observed on 4–6 September, coinciding with and slightly preceding the earthquake. When combined with the Japanese results shown in Figure 4, these findings strongly suggest that the VLF/LF propagation anomalies on 4–6 September are likely precursory signatures of the earthquake. However, the anomalies on 5 and 6 September occurred during minor geomagnetic disturbances, making their seismogenic origin somewhat uncertain.

Figure 5.

VLF/LF propagation along the JJY–PTK (upper) and JJI–PTK (lower) paths. The −2σ threshold is shown by dotted lines. Distinct amplitude anomalies observed on 4–6 September, primarily before the earthquake, are likely seismogenic, though slight geomagnetic disturbances introduce some uncertainty.

Figure 6.

The same as Figure 5, but at the station of YHS.

Extended and more intense amplitude decreases were observed at PTK in September (10–16 and 20–26 September), as shown in Figure 5. Given that the PTK propagation path lies in the mid-latitudes, these anomalies could result from either heightened geomagnetic activity or increased seismic activity, as indicated in Figure 5.

As noted earlier, the YHS data are somewhat unreliable due to interruptions in observations caused by power supply failures; nevertheless, the VLF/LF data are presented in Figure 6. The third panel corresponds to JJY and the bottom panel to JJI. Consistent with observations at WKN and given the close proximity between YHS and WKN, similar anomalies can be identified on 4 and 5 September. This figure thus provides additional evidence for the presence of VLF/LF propagation anomalies on those days as indicators of seismogenic lower-ionospheric disturbances.

We give extensive importance to the effect of typhoons on VLF/LF propagation, because it is known that VLF/LF propagation anomalies can be identified within a few hours (mainly at night) only when a typhoon crosses the VLF/LF propagation path or within a few days when the typhoon passes close to the propagation path [94,95,96]. Unfortunately, we encountered a rather big typhoon, No. 21 # in Japan, during our seismic period. This typhoon was located in the south of Shikoku Island at UT = 00 h on 4 September, crossed the Osaka area, then passed into Japan Sea at UT = 12 h on 4 September, and moved to the north–west of Hokkaido Island at UT = 00UT on 5 September. The typhoon became closest to the most important propagation path of JJY-WKN at UT = 18 h on 4 September with distance of 250–300 km, far away from the JJY = −WKN propagation path, so we can expect and that the anomaly on 4 September as observed at WKN is highly likely to be unrelated to this typhoon, but to be of seismic origin. As an extension of this consideration, the VLF/LF propagation anomalies observed at Russian stations are, in principle, reflecting the same ionospheric perturbation as identified for the JJY-WKN propagation path.

To robustly establish the seismogenic origin of the observed VLF/LF anomalies, several cross-verification criteria must be satisfied. First, the anomalies appear synchronously across multiple propagation paths (JJY–WKN, JJI–WKN, and JJY–PTK) with overlapping Fresnel zones that intersect the EQ’s epicentral region, implying a common lower-ionospheric perturbation source rather than independent transmitter- or receiver-based effects. Second, these disturbances occurred under geomagnetically quiet conditions (Dst ≈ −25 nT, Kp ≤ 2) immediately before the EQ, which excludes global magnetic or ionospheric storm-related causes. Third, the amplitude depressions are statistically significant, exceeding −2σ to −3.5σ thresholds derived from multi-day baselines, and thus far beyond normal day-to-day ionospheric variability. Fourth, the temporal sequence of anomalies—first detected on 4–5 September—matches the typical lead time of pre-seismic lower-ionospheric perturbations reported in earlier studies as mentioned in the Section 1. Finally, the spatial coherence between Japanese and Russian observation networks further strengthens the argument for a lithosphere–atmosphere–ionosphere coupling (LAIC) process rather than localized instrumental or meteorological noise. Together, these lines of evidence provide a physically consistent and statistically defensible basis for interpreting the 4–6 September VLF/LF anomalies consistent with the LAIC scenario associated with the Hokkaido EQ.

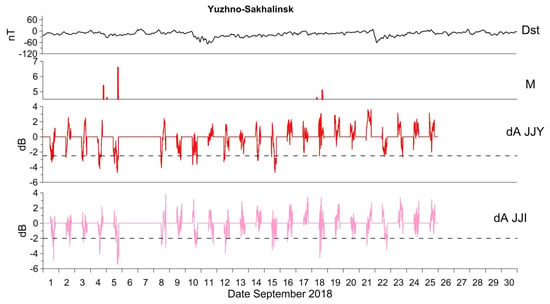

3.2. NARMAX/LSTM Outcomes

Next, we will present analysis results based on the application of AI (machine/deep learning) only to the nighttime average amplitude VLF data (JJY to WKN path) in order to confirm objectively the presence of the anomaly detected by the above conventional statistical method. Figure 7 illustrates the final NARMAX/LSTM result on the difference (residue) between the measured values and those predicted during our prediction target period from 1 August to 31 October 2018. Bollinger bands are derived from a moving average. Then, the standard deviation (σ) for that period is calculated, and the upper and lower bands are formed by adding or subtracting ±2σ or ±3σ from the moving average. We can learn from this figure that propagation anomalies of nighttime average amplitude for the propagation path of JJY-WKN are detected on 4 September, that is, one day before the Hokkaido EQ, with difference exceeding down below −2σ. We can confirm objectively that this anomaly is a conventional precursor-like signal to the EQ, which provides us with a further support to the presence of anomaly with the conventional statistical analysis. The two additional anomalies observed in mid-August and late September (Figure 7) coincide closely with periods of elevated geomagnetic activity shown in Figure 2. During mid-August (DOY 230–238), a geomagnetic storm occurred with Dst ≈ −150 nT, Kp = 6–7, and Ap(3h) > 100 nT, corresponding to the first VLF/LF amplitude depression. A similar though weaker disturbance in late September (DOY 257–260), marked by Dst < −50 nT and Kp ≈ 5–6, aligns with the second anomaly. These temporal coincidences confirm that both events originated from geomagnetic storms rather than seismogenic processes.

Figure 7.

Deviation in observed nighttime average amplitude values from NARMAX-LSTEM predicted values with Bollinger band analysis of ±2σ. The day of the EQ with magnitude M = 6.7 is indicated by EQ (5 September). Finally, the value exceeding −2σ is indicated with a red circle on the top of each bar, and the anomaly on 4 September is a definite precursor to the EQ.

From the standpoint of the AI analysis, the seismogenic nature of the detected anomaly is supported by the model’s ability to distinguish event-related deviations from background fluctuations through data-driven learning of nonlinear dynamics. The NARMAX/LSTM network was trained to predict the expected nighttime VLF amplitude from multi-source geophysical inputs (Dst, Kp, IMF, F10.7, and autoregressive terms), effectively modeling and compensating for known space–weather-driven variability. Therefore, residuals beyond the ±2σ or ±3σ Bollinger bounds represent deviations unexplained by any of these exogenous drivers. The appearance of such an outlier on 4 September 2018, one day before the earthquake, in both conventional statistics and the model-based residuals, confirms that the disturbance is not an artifact of model bias or geomagnetic forcing, but an anomaly plausibly consistent with a seismogenic lower-ionospheric perturbation.

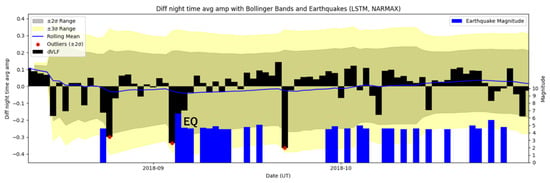

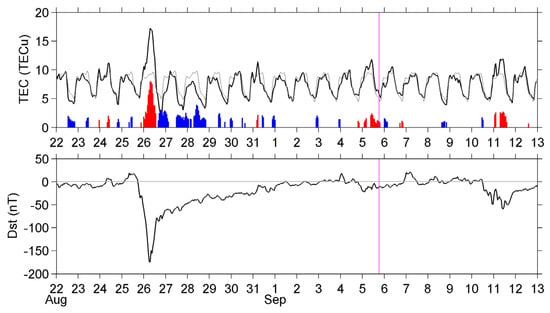

3.3. Upper-Ionospheric Perturbation, TEC Data

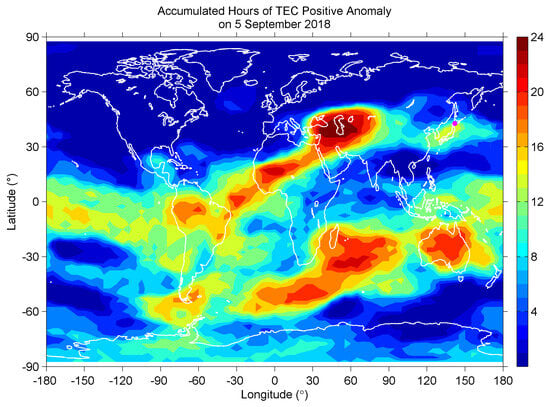

Figure 8 (top panel) shows TEC variation (black line), reflecting the upper F-region’s data, alongside the Dst index variation (bottom panel), since geomagnetic activity strongly influences the upper ionosphere. The mean variation over the previous month is shown with thin lines, and deviations from this mean (differential TEC or dTEC) are plotted above the x-axis: positive anomalies are in red, negative in blue; only those exceeding 1 σ are included. Notable geomagnetic storm effects on TEC are observed in late August and 11 September. The positive anomaly just before the earthquake on 5 September aligns with prior statistical findings of pre-earthquake TEC anomalies over Japan [97,98], with its polarity being positive. However, such positive anomalies also appear globally during weak geomagnetic disturbances, indicated by a Dst index around −20 nT. This is evident in Figure 9 which presents a global map showing the accumulated hours (h) during which TEC anomalies exceeded the +1σ (σ is the standard deviation) threshold on 5 September 2018. Around the earthquake epicenter, the anomaly persisted for approximately 13 h (>1σ), indicating a sustained deviation compared to surrounding regions. The anomaly in the Japanese sector (≈13 h) was more pronounced than in neighboring areas, suggesting localized enhancement. Globally, 23.9% (1240/5183) of all grid points recorded anomalies exceeding the +1σ level for more than 8 h, with certain regions (e.g., Western Asia) exhibiting continuous exceedance over the full 24 h period. Although the anomaly near the earthquake site is significant, it is not unique nor exclusively seismogenic, as similar >1σ anomalies occurred elsewhere, likely influenced by both regional and global drivers, including geomagnetic conditions. Compared with previous VLF/LF observations, which showed anomalies on 4–6 September, the TEC exceeded the +1σ level only on 5 September, making it difficult to conclusively separate geomagnetic effects from possible seismic contributions.

Figure 8.

Temporal variation in TEC values over the EQ epicenter with full black lines. The thin black line indicates the mean over the previous month, with the differential dTEC (increase in red, decrease in blue) shown above the x-axis. A magenta line marks the EQ date. The bottom panel reproduces Dst variation.

Figure 9.

Accumulated hours (h) of TEC anomalies exceeding the +1σ threshold on 5 September 2018. The color bar indicates the total duration (h) during which TEC > +1σ at each grid point. The earthquake epicenter and regional anomaly structure are highlighted for comparison.

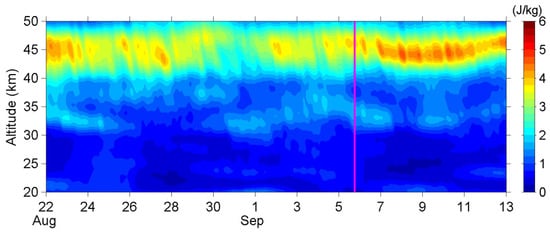

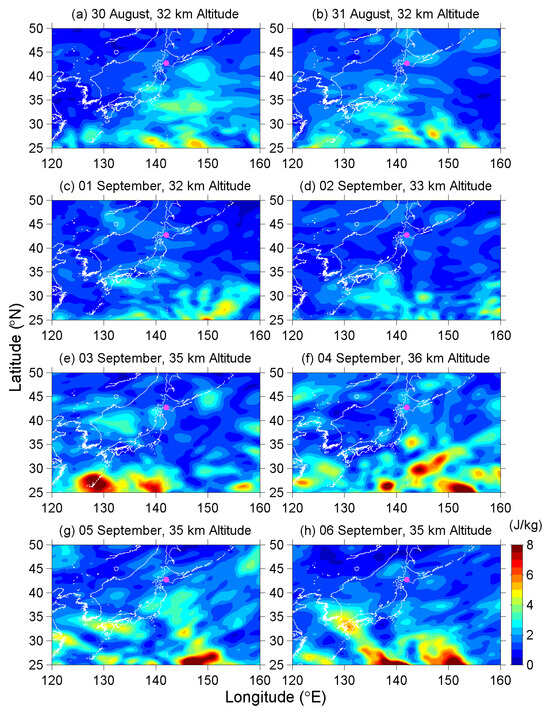

3.4. Stratospheric Effects AGW Effect

Figure 10 presents the AGW activity expressed as potential energy (Ep) from 22 August to 12 September, directly above the earthquake epicenter. A bright band of elevated Ep values appears near 45 km altitude, corresponding to the temperature inversion at the stratopause; this feature is not the focus here. Instead, attention is directed to another region of enhanced Ep between 32 and 35 km altitude. The AGW activity remained generally high throughout the period, except for a brief decrease between 26 and 29 August, and there is no clear evidence of enhanced AGW activity immediately before the earthquake. Figure 11 illustrates the daily variation in the spatial distribution of Ep activity in the height range of 32–35 km from 30 August to 6 September. AGWs are active around Japan during this period, but these waves are likely to be associated with meteorological phenomena. A cold front passed Hokkaido on 31 August, when another stationary front had remained around Japan for a long period from 24 August to 2 September. As mentioned earlier, a typhoon passed over western Japan on 4 September and subsequently transformed into an extratropical cyclone, while frontal systems redeveloped over Japan on 5 and 6 September. During the presumed earthquake preparation period, numerous convective weather systems were active around Japan, resulting in persistently high wave activity, as shown in Figure 9 and Figure 10. Consequently, meteorological influences during this time cannot be ruled out, making it difficult to determine whether any seismic effects were present. Even if such effects existed, they would likely have been minor compared with the dominant meteorological disturbances. Therefore, due to the intense weather activity—including the passage of a typhoon—no clear seismo-related AGW signatures were detected in the stratosphere, unlike those observed for the 2011 Tohoku earthquake [88] and the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake [89].

Figure 10.

Altitudinal–temporal variation in AGW Ep in the stratospheric height range of 20 to 50 km over the EQ epicenter. A vertical magenta line marks the day of the EQ.

Figure 11.

Temporal evolution during eight days from 30 August to 6 September 2018 of Ep spatial distributions in the height range of 32–35 km. The EQ epicenter is given by a small magenta circle.

3.5. Satellite and Ground Monitoring of Earth’s Surface Parameters (T, RH, ACP, and SLHF)

Satellite monitoring has been performed to investigate the following Earth’s surface parameters, such as T, RH, ACP, and SLHF [20,21,22,25,27,28]. Here, we have to describe briefly the data source and analysis method. The main process for this thermal anomaly is the emission of latent heat of evaporation during the condensation of water vapor on the ions induced by the ionization of atmospheric gas molecules by radioactive radon from the lithosphere [2,3,5,84,90,91]. The NCEP/NCAR Reanalysis system available from the NOAA Physical Sciences Laboratory represents one of the most comprehensive frameworks for reconstructing the historical state of the Earth’s atmosphere by integrating observational data with advanced numerical weather prediction. The assimilation is performed four times a day daily UTC (at 00, 06, 12, and 18 h), which generates high-resolution gridded fields by optimally merging observations from diverse sources with short-term model forecasts. The computation of daily average fields such as air temperature, etc., involves a temporal integration of these six-hourly reanalysis outputs. Here we use a typical 10° latitude by 10° longitude domain just around the Hokkaido EQ epicenter. Further, in this paper we have applied the following residue analysis to emphasize the difference (residue) of the data during our EQ period from the average value of the data in the same period of the years of 2017 and 2019.

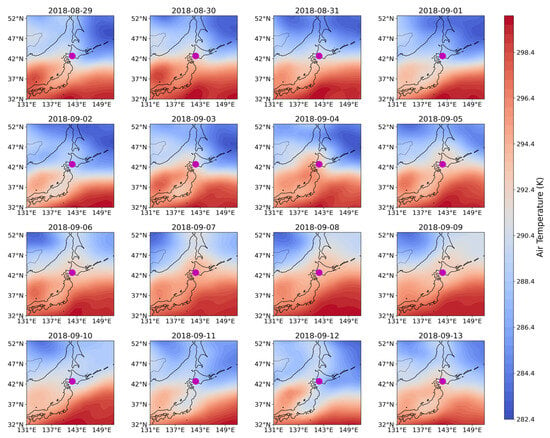

First, we show, in Figure 12, the daily residue plots of T about one week before and after the EQ (5 September). Redder in the figure means an increase in temperature, while more blue means a decrease in temperature. The EQ epicenter is indicated by a magenta circle. From 1 to 5 September, temperature patterns remain relatively stable across the Hokkaido area, with no significant anomalies visually apparent near the EQ epicenter.

Figure 12.

Daily evolutions of relative difference in temperature from the corresponding average in the years of 2017 and 2019. The time window is defined as one week before the earthquake (29 August 2025) and one week after the earthquake (13 September 2025). EQ epicenter is indicated by a magenta circle.

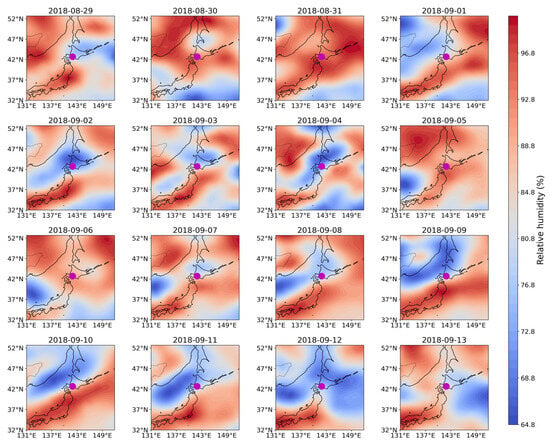

Then, Figure 13 is the corresponding results for RH for this EQ, which means that during the period of 29 August to 5 September, a noticeable reduction in RH is observed over the central and northern Hokkaido. This pre-seismic drying may be indicative of moisture divergence or suppressed atmospheric saturation.

Figure 13.

Daily evolutions of relative difference in RH from the corresponding average in the years of 2017 and 2019. The time window is the same as Figure 12.

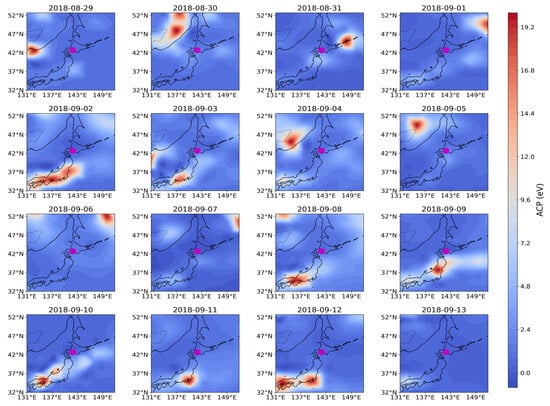

Then, ACP as a combinational function of T and RH in Figure 14 indicates elevated ACP values (above 14 eV) appear intermittently over Hokkaido and surrounding regions before the EQ, particularly on 30 August and 1 September (fair weather), suggesting unusual thermodynamic activity possibly associated with crust–atmosphere interactions.

Figure 14.

Daily evolutions of relative difference in ACP from the corresponding average in the years of 2017 and 2019. The time window is the same as Figure 12.

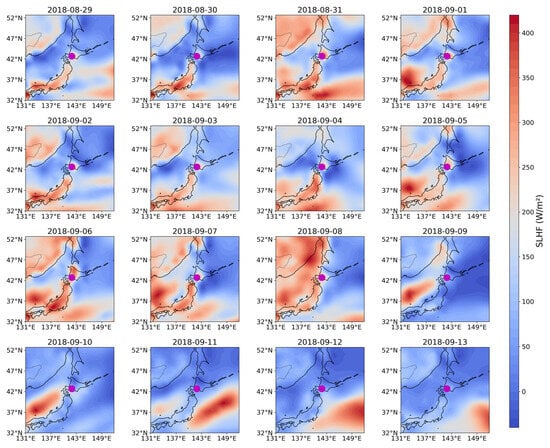

Figure 15 refers to the variation in SLHF. Elevated SLHF values (200–400 W/m2) are seen during 30 August to 1 September near the southern and coastal zones, including around the EQ epicenter, just before the EQ. This suggests a possible increase in latent heat release linked to enhanced evapotranspiration or subsurface vapor release. On 5 September (EQ day) and 6 September, there is a notable concentration of SLHF anomalies near the epicentral area. This might indicate atmospheric instability or localized energy redistribution due to tectonic stress release. Following the seismic event, SLHF values in the Hokkaido region decrease sharply, especially from 7 to 10 September, indicating a cooling and moisture loss phase possibly tied to reduced surface evaporation.

Figure 15.

Daily evolutions of relative difference in SLHF from the corresponding average in the years of 2017 and 2019. The time window is the same as Figure 12.

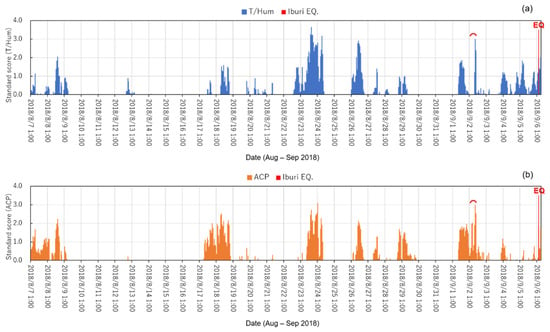

Lastly, we present the ground-based result using AMeDAS observation of T/RH and ACP [71,99]. Because the satellite monitoring provides us with the wide-range information but with lower spatial resolution, we here present the result of AMeDAS observation by Japan Meteorological Agency with dense network in Japan with much higher spatial resolution [84,100]. Only one AMeDAS station of Tomakomai (42 37.4′ N, 141 32.8′ E) is available for this study. We present in Figure 16 the temporal evolution of meteorological parameters (T/RH (in blue) in the upper panel and ACP (in red) in the lower panel during the month before the EQ. The values on the ordinate mean the detrended values normalized by the standard deviation during this one month, so 2 as an example indicates m + 2σ. The time axis on the abscissa is given in LT (local time, not UT) in the figure. As already described before, we have to pay attention to the meteorological conditions. We have carefully checked the weather maps (www.jma.go.jp accessed on 10 January 2025) during this period, and it is found that it was fair weather on 1 and 2 September, while we had severe weather conditions on the preceding and subsequent days. We could not obtain any significant results on T/RH and ACP on 3, 4, and 5, September, because there was an increase in T and a slow change in RH with a lot of fluctuations on 3–6 September, and the atmosphere seemed to be humid and muggy on these days. On other hand, we have meaningful results on 1 and 2 September, such that local enhancements on both parameters (T and RH) just around mid-day are seen as a typical diurnal variation on 1 September, but probably just due to the solar radiation effect. However, we have a completely different diurnal pattern on 2 September, in which we notice a small peak in both T/RH and ACP at LT = 1 h (T = 15.2 °C, RH = 86%) and a conspicuous peak at LT = 10 h. In particular, we look at an anomaly in a stable parameter of ACP (bottom) with red marking. These variations are likely to be precursors to the EQ.

Figure 16.

Ground-based monitoring of (a) T/RH (upper panel) and (b) ACP (lower panel) at a particular station of Tomakomai close to the EQ epicenter. The value on the ordinate means the detrended value normalized by standard deviation (σ).

4. Lithosphere–Atmosphere–Ionosphere Coupling (LAIC) Channel

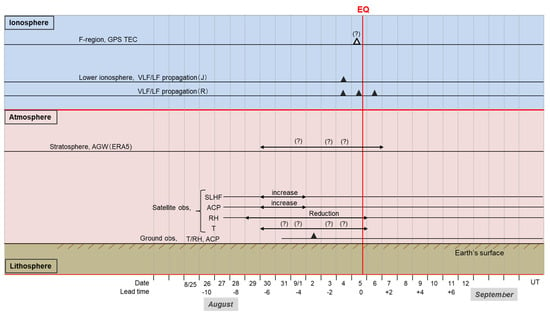

Based on the multi-parameter and multi-layer observational results, a consolidated summary is shown in Figure 17. In the ionospheric F-region (top layer), a possible anomaly was observed on 5 September; however, its significance is low, so it is marked with a white triangle, indicating low-confidence or uncertain detections. In contrast, perturbations in the lower ionosphere were identified with high confidence from both Japanese (denoted as J) and Russian (denoted as R) monitoring systems, and these strong detections are marked with black triangles in the figure. In the stratosphere, many AGW-like disturbances were observed, but these signals are most likely related to intense convective weather activity rather than seismic processes; therefore, they are marked with question marks to show ambiguity. At the Earth’s surface and within the lowest atmospheric layers, both satellite- and ground-based measurements were reviewed; however, due to the same severe weather conditions, no clear pre-seismic precursor signs could be identified. Still, the period from 29 August to 5 September, especially 30 August to 2 September, seems to be notably disturbed across multiple datasets, indicating a phase of increased geophysical variability.

Figure 17.

LAIC channel. From the top, we indicate the result of ionospheric F-region by GIM TEC, then lower-ionospheric precursors (as observed in Japan (J) and in Russia (R)). We observe plenty of stratospheric activities, but probably due to meteorological activities. Finally, Earth’s surface observations by satellites and ground observation are included, which suggests rather high perturbations during the period of 29 August to 5 September, with an emphasis on 30 August to 2 September.

The multi-parameter observations analyzed in this work reveal a coherent sequence of atmospheric and ionospheric disturbances preceding the 2018 Hokkaido earthquake. These include pronounced TEC enhancements, changes in VLF/LF signal amplitude, and surface thermal fluctuations, all of which occurred under geomagnetically quiet and meteorologically stable conditions. Such spatiotemporal consistency supports their interpretation as potential seismo-ionospheric precursor-type signals, reflecting the atmosphere–ionosphere’s sensitivity to lithospheric stress accumulation. However, it must be noted that the presence of these anomalies, though temporally aligned with the earthquake preparation phase, does not by itself confirm a direct causal mechanism. The atmosphere–ionosphere system is inherently variable, and similar fluctuations can occasionally emerge without seismic triggers. To mitigate this ambiguity, our analysis included multiple independent datasets and background controls, ensuring that the detected anomalies are not random or space–weather-induced. Therefore, the anomalies can be reliably considered as physically consistent and statistically significant indicators within the LAIC framework, representing a probabilistic association rather than deterministic prediction. Continued multi-event studies, long-term statistical validation, and numerical modeling are required to substantiate further the causal pathways linking these anomalies to lithospheric processes. Hence, by comparing these all parameters, we come to a conclusion that the LAIC channel for this Hokkaido EQ is more likely to be close to a slow channel as defined in [30]. That is, the perturbations on the Earth’s surface due to the pre-EQ activity in the lithosphere happens first as the origin of the LAIC, and those effects seem to drift up to the ionosphere with the delay of a few days. The mechanism of this kind of diffusion-type energy transfer is quite unknown at the moment.

5. Summary and Conclusions

Based on analyses of various parameter observations—including sub-ionospheric VLF data from Japan and Russia, GIM TEC data, ERA5 temperature profiles, and satellite and ground-based surface monitoring of T, RH, ACP, and SLHF, several key findings have emerged regarding the significant Hokkaido earthquake that occurred on 5 September 2018 (UT) with a magnitude of M = 6.7.

(1) The most consistent and reliable evidence comes from VLF/LF signal data recorded from two Japanese transmitters, observed at stations in both Japan and Russia. These observations reveal distinct precursory propagation anomalies on 4 September along the JJY–WKN and JJI–WKN paths in Japan, and on 4, 5, and 6 September along the JJY–PTK path. By comparing the anomalous days with the typhoon’s trajectory, we have ruled out meteorological influences during the earthquake preparation period. Therefore, the anomaly detected on 4 September, one day before the earthquake, is considered a strong seismogenic signature. The anomalies on 5 and 6 September are also likely seismogenic, although some caution is warranted due to the possible influence of a minor geomagnetic storm.

(2) The above propagation anomaly on 4 September for the propagation path of JJY-WKN has been checked objectively with the use of AI (machine/deep learning), and the anomaly was reconfirmed as crucial by comparing the actually observed values with those predicted, providing further support to the conventional statistical analysis.

(3) For the GIM TEC data in the upper ionosphere (F-region) above the EQ epicenter, we have detected an anomaly on 5 September, EQ day. Still, we cannot distinguish the origin of this anomaly clearly between the geomagnetic storm effect and seismic effect.

(4) The analysis of stratospheric AGW activity using ERA5 temperature profile data revealed numerous AGW anomalies. However, these are most likely caused by strong meteorological influences, including typhoon effects. Unlike the cases of the 2016 Kumamoto EQ [57,89] and the 2011 Tohoku EQ [88], where the AGW hypothesis supported the LAI coupling, we cannot definitively link any observed precursor activity in the lower ionosphere before the Hokkaido EQ to AGW phenomena. This uncertainty is compounded by adverse weather conditions, including a typhoon and a minor geomagnetic storm, during our EQ preparation period.

(5) The satellite monitoring together with assimilated data on the Earth’s surface information (T, RH, ACP, and SLHF) have indicated some anomalies from 29 August to 5 September; in particular, the period from 30 August to 2 September seems to be seismogenically perturbed. And ground-based AMeDAS data have indicated rather clearly the presence of T/RH and ACP on 2 September during the fair weather condition, a few days prior to the EQ date.

(6) By summarizing all information of multi-parameter and multi-layered observations, we can conclude that a slow channel of diffusion type is working for this Hokkaido EQ, in which the lower-ionospheric perturbation generated one day before the EQ, is probably due to the anomaly on Earth’s surface thermal anomalies with a delay of a few days, but this mechanism needs further extensive studies. A table containing dataset, source, spatial/temporal resolution, analyzed time window, main processing steps and thresholds are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of datasets and anomaly detection methods.

This study integrates ionospheric, atmospheric, and surface observations to investigate the temporal evolution of pre-earthquake disturbances associated with the 2018 Hokkaido event. The consistent anomalies detected across GIM TEC, VLF/LF propagation and ERA5 surface parameters occurred prior to several days of the main shock. They were centered near the epicentral region, under geomagnetically quiet and stable atmospheric conditions. Such coherence across multiple geophysical layers suggests that these signals represent potential seismo-ionospheric precursory responses, plausibly linked to LAIC processes. However, while the observed temporal and spatial correspondence support this interpretation, it does not alone confirm causality. The results thus reflect a consistent correlation with a credible physical context, rather than a deterministic predictive capability. Future efforts should focus on expanding the analysis to multiple seismic events, employing statistical validation and physics-based modeling, to better quantify the strength and reliability of these precursor-type signatures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.H.; methodology, M.S., S.H., S.S., K.N., G.K., S.-S.Y., K.M., H.H.; writing—original draft preparation, M.H.; writing—review and editing, M.S., S.H., S.S., S.-S.Y., K.M., H.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work had no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data of geomagnetic and solar activities can be downloaded from the OMNIWEB (https://omniweb.gsfc.nasa.gov/form/dx1.html (accessed on 1 April 2025)). AMeDAS data of JMA (Japan Meteorological Agency) are available from the site at https://www.data.jma.go.jp/risk/obsdl/index.php (accessed on 1 April 2025), and the NCEP/NCAR Reanalysis data which are available from the NOAA Reanalysis repository at https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.ncep.reanalysis.html (accessed on 15 January 2025). The ERA5 data are available in the Copernicus Climate Data Store at https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/ (accessed on 25 December 2024) implemented by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF). The CODE GIM TEC data can be downloaded from http://ftp.aiub.unibe.ch/CODE/ (accessed on 26 February 2019).

Acknowledgments

We thank CODE at University of Bern, Swiss for providing us with the GIM TEC data. The ERA5 data is processed and carried out by ECMWF within the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) to which we are thankful. Finally, S.S. is thankful to NICT (National Institute of Communications Technology) (Japan Trust program) for its financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

M.H., K.M., S.S. and H.H. are employees of Hi-SEM, and S.H. is an employee of HiSR Inc., but this paper reflects the views of the scientists and not the companies.

References

- Hayakawa, M.; Molchanov, O.A. Seismo-Electromagnetics: Lithosphere-Atmosphere-Ionosphere Coupling; TERRAPUB: Tokyo, Japan, 2002; p. 477. [Google Scholar]

- Pulinets, S.A.; Boyarchuk, K. Ionospheric Precursors of Earthquakes; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2004; p. 315. [Google Scholar]

- Molchanov, O.A.; Hayakawa, M. Seismo Electromagnetics and Related Phenomena: History and Latest Results; TERRAPUB: Tokyo, Japan, 2008; p. 189. [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa, M. Earthquake Prediction with Radio Techniques; John Wiley and Sons: Singapore, Singapore, 2015; p. 294. [Google Scholar]

- Sorokin, V.; Chmyrev, V.; Hayakawa, M. Electrodynamic Coupling of Lithosphere-Atmosphere-Ionosphere of the Earth; NOVA Science Pub. Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2015; p. 326. [Google Scholar]

- Ouzounov, D.; Pulinets, S.; Hattori, K.; Taylor, P. Pre-Earthquake Processes: A Multidisciplinary Approach to Earthquake Prediction Studies; Geophysical Monograph Series 234; AGU: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; p. 365. [Google Scholar]

- Rozhnoi, A.; Solovieva, M.S.; Molchanov, O.A.; Hayakawa, M. Middle latitude LF (40 kHz) phase variations associated with earthquakes for quiet and disturbed geomagnetic conditions. Phys. Chem. Earth 2004, 29, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, M. Probing the lower ionospheric perturbations associated with earthquakes by means of subionospheric VLF/LF propagation. Earthq. Sci. 2011, 24, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozhnoi, A.; Solovieva, M.; Hayakawa, M. VLF/LF signals method for searching of electromagnetic precursors. In Earthquake Prediction Studies: Seismo Electromagnetics; Hayakawa, M., Ed.; TERRAPUB: Tokyo, Japan, 2013; pp. 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa, M.; Asano, T.; Rozhnoi, A.; Solovieva, M. Very-low- and low-frequency sounding of ionospheric perturbations and possible association with earthquakes. In Pre-Earthquake Processes: A Multidisciplinary Approach to Earthquake Prediction Studies; Ouzounov, D., Pulinets, S., Hattori, K., Taylor, P., Eds.; AGU: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 277–304. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.Y.; Chen, Y.I.; Chuo, Y.J.; Chen, C.S. A statistical investigation of pre-earthquake ionospheric anomaly. J. Geophys. Res. 2006, 111, A05304. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.Y.; Hattori, K.; Chen, Y.I. Application of total electron content derived from the Global Navigation Satellite System for detecting earthquake precursors. In Pre-Earthquake Processes: A Multidisciplinary Approach to Earthquake Prediction Studies; Ouzounov, D., Pulinets, S., Hattori, K., Taylor, P., Eds.; AGU: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 305–317. [Google Scholar]

- Parrot, M. First results of the Demeter micro-satellite. Planet. Space Sci. 2006, 54, 411–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, M. Electromagnetic phenomena associated with earthquakes: A frontier in terrestrial electromagnetic noise environment. Recent Res. Dev. Geophys. 2004, 6, 81–112. [Google Scholar]

- Molchanov, O.; Fedorov, E.; Schekotov, A.; Gordeev, E.; Chebrov, V.; Surkov, V.; Rozhnoi, A.; Andreavsky, A.; Iudin, D.; Yunga, S.; et al. Lithosphere-atmosphere-ionosphere coupling as governing mechanism for preseismic short-term events in atmosphere and ionosphere. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2004, 4, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulinets, S.; Ouzounov, D. Lithosphere-atmosphere-ionosphere coupling (LAIC)- A unified concept for earthquake precursors validation. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2011, 41, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Santis, A.; Balasis, G.; Pavón-Carrasco, F.J.; Cianchini, G.; Mandea, M. Potential earthquake precursory pattern from space: The 2015 Nepal event as seen by magnetic Swarm satellites. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2017, 461, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Santis, A.; Cianchini, G.; Marchetti, D.; Piscini, A.; Sabbagh, D.; Perrone, L.; Campuzano, S.A.; Inan, S. A multiparametric approach to study the preparation phase of the 2019 M7.1 Ridgecrest (California, USA) earthquake. Front. Earth Sci. 2020, 8, 540398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhoondzadeh, M.; De Santis, A.; Marchetti, D.; Piscini, A.; Jin, S. Anomalous seismo-LAI variations potentially associated with the 2017 Mw = 7.3 Sarpol-e Zahab (Iran) earthquake from Swarm satellites, GPS-TEC and meteorological data. Adv. Space Res. 2019, 64, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzounov, D.; Pulinets, S.; Davidenko, D.; Rozhnoi, A.; Solovieva, M.; Fedun, V.; Dwivedi, B.N.; Rybin, A.; Kafatos, M.; Taylor, P. Transient effects in atmosphere and ionosphere preceding the 2015 M7.8 and M7.3 Gorkha–Nepal earthquakes. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 757358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrot, M.; Tramutoli, V.; Liu, J.Y.; Pulinets, S.; Ouzounov, D.; Genzano, N.; Lisi, M.; Hattori, K.; Namgaladze, A. Atmospheric and ionospheric coupling phenomena associated with large earthquakes. Eur. Phys. J. Spéc. Top. 2021, 230, 197–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasmal, S.; Chowdhury, S.; Kundu, S.; Politis, D.Z.; Potirakis, S.M.; Balasis, G.; Hayakawa, M.; Chakrabarti, S.K. Pre-seismic irregularities during the 2020 Samos (Greece) earthquake (M = 6.9) as investigated from multi-parameter approach by ground and space-based techniques. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, M.; Izutsu, J.; Schekotov, A.; Yang, S.S.; Solovieva, M.; Budilova, E. Lithosphere-atmosphere-ionosphere coupling effects based on multiparameter precursor observations for February-March 2021 earthquakes (M~7) in the offshore of Tohoku area of Japan. Geosciences 2021, 11, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, M.; Schekotov, A.; Izutsu, J.; Yang, S.S.; Solovieva, M.; Hobara, Y. Multi-parameter observations of seismogenic phenomena related to the Tokyo earthquake (M = 5.9) on 7 October 2021. Geosciences 2022, 12, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Arcangelo, S.; Regi, M.; De Santis, A.; Perrone, L.; Cianchini, G.; Soldani, M.; Piscini, A.; Fidani, C.; Sabbagh, D.; Lepidi, S.; et al. A multiparametric-multilayer comparison of two geophysical events in the Tonga-Kermadec subduction zone: The 2019 M7.2 earthquake and 2022 Hunga Ha’apai eruption. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 12677411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; De Santis, A.; Perrone, L.; Xiong, P.; Zhang, X.; Du, X. Lithoshere-atmosphere-ionosphere coupling associated with four Yutian earthquakes in China from GPS TEC and electromagnetic observations onboard satellites. J. Geodyn. 2023, 155, 101943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, D.; Zhu, Z.; Picsini, A.; Ghamry, E.; Shen, X.; Yan, R.; He, X.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Wen, J.; et al. Changes in the lithosphere, atmosphere and ionosphere before and after the Mw = 7.7 Jamaica 2020 earthquake. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 307, 114146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasmal, S.; Chowdhury, S.; Kundu, S.; Ghosh, S.; Politis, A.Z.; Potirakis, S.M.; Hayakawa, M. Multi-parametric study of seismogenic anomalies during the 2021 Crete earthquake (M = 6.0). Ann. Geophys. 2024, 66, SE646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianchini, G.; Calcara, M.; De Santis, A.; Piscini, A.; D’Arcangelo, S.; Fidani, C.; Sabbagh, D.; Orlando, M.; Perrone, L.; Campuzano, S.A.; et al. The preparation phase of the 2023 Kahramanmaras (Turkey) major earthquakes from a multidisciplinary and comparative perspective. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, M.; Hobara, Y. Integrated analysis of multi-parameter precursors to the Fukushima offshore earthquake (Mj = 7.3) on 13 February 2021 and lithosphere-atmosphere-ionosphere coupling channels. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; Sun, Y.Y.; Zhang, X.; Gao, Y.; Yisimayili, A.; Qing, H.; Yeh, T.K.; Lin, K.; Wang, F.; Yen, H.Y.; et al. Double resonance in seismo-lithosphere-atmosphere-ionosphere coupling. Ann. Geophys. 2024, 66, SE641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulinets, S. Lithosphere-atmosphere-ionosphere coupling (LAIC) model. In Electromagnetic Phenomena Associated with Earthquakes; Hayakawa, M., Ed.; Transworld Research Network: Trivandrum, India, 2019; pp. 235–253. [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti, D.; De Santis, A.; Campuzano, S.A.; Zhu, K.; Soldani, M.; D’Arcangelo, S.; Orlando, M.; Wang, T.; Cianchini, G.; Di Mauro, D.; et al. Worldwide statistical correlation of eight years of Swarm satellite data with M5.5+ earthquakes: New hints about the preseismic phenomena from space. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; De Santis, A.; Liu, J.; Campuzano, S.A.; Yang, N.; Cianchini, G.; Ouyang, X.; D’arcangelo, S.; Yang, M.; De Caro, M.; et al. Pre-Earthquake Oscillating and Accelerating Patterns in the Lithosphere–Atmosphere–Ionosphere Coupling (LAIC) before the 2022 Luding (China) Ms6.8 Earthquake. Remote. Sens. 2024, 16, 2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Santis, A.; Cianchini, G.; Perrone, L.; Soldani, M.; Rahimi, H.; Alimoradi, H. Foundations for an operational earthquake prediction system. Geosciences 2025, 15, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, L.; Picozza, P.; Sotgiu, A. A critical review of ground based observations of earthquake precursors. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 676766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picozza, P.; Conti, L.; Sotgiu, A. Looking for earthquake precursors from space: A critical review. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 676775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghamry, E.; Mohamed, E.K.; Abdalzaher, M.S.; Elwekeil, M.; Marchetti, D.; De Santis, A.; Hegy, M.; Yoshikawa, A.; Fathy, A. Integrating pre-earthquake signatures from different precursor tools. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 33268–33283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Han, P.; Hattori, K. Recent advances and challenges in the seismo-electromagnetic study: A brief review. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, D.; De Santis, A.; D’Arcangelo, S.; Poggio, F.; Piscini, A.; Campuzano, A.; Werneck, V. Pre-earthquake chain processes detected from ground to satellite altitude in preparation of the 2016–2017 seismic sequence in central Italy. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 229, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhao, X.; Yang, D.; Wu, Y.; Li, Q. A Study to Investigate the Relationship between Ionospheric Disturbances and Seismic Activity Based on Swarm Satellite Data. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 2021, 323, 106826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulinets, S.; Ouzounov, D.; Karelin, A.; Davidenko, D. Lithosphere-atmosphere-ionosphere-magnetosphere coupling—A concept for pre-earthquake signals generation. In Pre-Earthquake Processes: A Multidisciplinary Approach to Earthquake Prediction Studies; Ouzounov, D., Pulinets, S., Hattori, K., Taylor, P., Eds.; AGU: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 79–98. [Google Scholar]

- Pulinets, S.A.; Ouzounov, D.P.; Karelin, A.V.; Davidenko, D.V. Physical bases of the generation of short-term earthquake precursors: A complex model of ionization-induced geophysical processes in the lithosphere-atmosphere-ionosphere-magnetosphere system. Geomagn. Aeron. 2015, 55, 521–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimenko, M.V.; Klimenko, V.V.; Zakharenkova, I.E.; Pulinets, S.A.; Zhao, B.; Tzidilina, M.N. Formation mechanism of great positive TEC disturbances prior to Wenchuan earthquake on May 12, 2008. Advances Space Res. 2008, 48, 488–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, F. Stress-activated positive hole carriers in rocks and the generation of pre-earthquake signals. In Electromagnetic Phenomena Associated with Earthquakesl; Hayakawa, M., Ed.; Transworld Research Network: Trivandrum, India, 2009; pp. 41–96. [Google Scholar]

- Woith, H. Radon earthquake precursor: A short review. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2015, 224, 611–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.L.; Huba, J.D.; Joyce, G.; Lee, L.C. Ionosphere plasma bubbles and density variations induced by preearthquake rock currents and associated surface charges. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2011, 116, A10317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, F.T. Pre-Earthquake Signals—Part I: Deviatoric Stresses Turn Rocks into a Source of Electric Currents. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2007, 7, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, F.T. Pre-Earthquake Signals—Part II: Flow of Charges and Associated Electromagnetic Emissions. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2007, 7, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, F.T.; Kulahci, I.G.; Cyr, G.; Ling, J.; Winnick, M.; Tregloan-Reed, J.; Freund, M.M. Air Ionization at Rock Surfaces and Pre-Earthquake Signals. J. Atmos. Sol.-Terr. Phys. 2009, 71, 1824–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, V.M. Plasma and electromagnetic effects in the ionosphere related to the dynamics of charged aerosols in the lower atmosphere. Russian J. Phys. Chem. B 2007, 1, 138–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Zhao, B.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Hu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, W. An Investigation of Pre-Seismic Ionospheric TEC and Acoustic–Gravity Wave Coupling Phenomena Using BDS GEO Measurements: A Case Study of the 2023 Jishishan Ms6.2 Earthquake. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozuka, Y.; Matsumura, M.; Otsuka, Y.; Ogawa, T.; Miyoshi, Y. Earthquake Source Impacts on the Generation and Propagation of Atmospheric and Acoustic–Gravity Waves. Geophys. J. Int. 2024, 238, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manesh, F.M.; Singh, R.; Kumar, S.; Maurya, A.K. Observation and Simulation of Atmospheric Gravity Waves as Precursors to Large Earthquakes. J. Atmos. Sol.-Terr. Phys. 2024, 252, 106352. [Google Scholar]

- Lizunov, G.; Hayakawa, M. Atmospheric gravity waves and their role in the lithosphere-troposphere-ionosphere interaction. IEEJ Trans. Fundam. Mater. 2004, 124, 1109–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hayakawa, M.; Kasahara, Y.; Nakamura, T.; Hobara, Y.; Rozhnoi, A.; Solovieva, M.; Molchanov, O.A.; Korepanov, V. Atmospheric gravity waves as a possible candidate for seismo-ionospheric perturbations. J. Atmos. Electr. 2011, 31, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.S.; Potirakis, S.M.; Sasmal, S.; Hayakawa, M. Natural time analysis of global navigation satellite system surface deformation: The case of the 2016 Kumamoto earthquakes. Entropy 2020, 22, 105392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piersanti, M.; Materassi, M.; Battiston, R.; Carbonne, V.; Cicone, A.; D’Angelo, G.; Diego, P.; Ubertini, P. Magnetospheric-ionospheric-lithospheric coupling model. 1: Observations during the 5 August 2018 Bayan earthquake. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, M.; Rozhnoi, A.; Solovieva, M.; Yang, S.S. On electromagnetic precursors to the Hokkaido earthquake in September 2018 and consideration of lithosphere-atmosphere-ionosphere coupling. Int. J. Electron. Appl. Res. 2019, 6, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Horne, B.G.; Tino, P.; Giles, C.L. Learning long-term dependencies in NARX recurrent neural networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 1996, 7, 1329–1338. [Google Scholar]

- Billings, S.A. Nonlinear System Identification: NARMAX Methods In the Time, Frequency, and Spatio-Temporal Domains; John Wiley and Sons: West Sussex, UK, 2013; p. 555. [Google Scholar]

- Santosa, H.; Hobara, Y. One day prediction of nighttime VLF amplitudes using nonlinear autoregression and neural network modeling. Radio Sci. 2017, 52, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balikhin, M.A.; Boynton, R.J.; Walker, S.N.; Borovsky, J.E.; Billing, S.A.; Wei, H.L. Using the NARMAX Approach to model the evolution of energetic electron fluxes at geostationary orbit. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2011, 38, L18105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Wei, H.L.; Balikhin, M.A.; Boynton, R.J.; Walker, S.N. Machine learning enhanced NARMAX model for Dst index forecasting. In Proceedings of the 2019 25th International Conference on Automation and Computing, IEEE Xplore11, Lancaster, UK, 5–7 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, J.; Hagan, M.T. Comparison of neural network NARX and NARMAX nodels for multi-step prediction using simulated and experimental data. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 237, 121437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanoiu, D.; Culita, J.; Voinea, A.-C.; Voinea, V. Nonlinear identification for control by using NARMAX models. Mathematics 2024, 12, 2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]