1. Introduction

The characterization and interpretation of regional climatic behavior remain central challenges for watershed managers to optimize water resources planning worldwide [

1,

2,

3]. The variability in the different components of the water cycle depends on large-scale atmospheric circulation patterns [

4,

5,

6]. The climate as a whole can be described as comprising a set of “modes of variability” or subsystems that fluctuate across different spatiotemporal scales [

7,

8]. These modes arise from the interactions of linear and nonlinear processes between components of the climate system [

9]. A random climatic process is said to be strictly stationary when its probabilistic characteristics are invariant under any shift in the origin. However, such processes are not necessarily controllable or “sympathetic”, which can lead to abrupt climate shifts and, at times, extreme hydrological events [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14].

Associations between large-scale circulation phenomena and rainfall are widely discussed and debated by climate researchers worldwide [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Within this framework, several techniques and mathematical approaches have been employed to estimate these nonlinear and nonstationary relationships, thereby facilitating the interpretation of observed dry and wet episodes [

24,

25]. In Turkey, annual and seasonal normalized rainfall were analyzed in relation to the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) using Pearson’s correlation and composite analysis. The results revealed that the positive NAO phases generally correspond to drier conditions, except during summer [

26]. Over Europe, based on the self-calibrated Palmer Drought Severity index and the coupled manifold technique [

27], results indicate that summer climate and winter rainfall are mainly governed by the NAO regime, with the positive phase of the NAO being largely responsible for the occurrence of hot and dry summers. Links between daily rainfall variability, the NAO, and the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO) in the Southern European Alps were analyzed over the period 1890–2017. The findings revealed nonstationary correlations among rainfall, NAO, and AMO. Moreover, a climatic shift around 1940—with statistically significant changes from the 1950s onward—coincides with enhanced NAO influence, during which spring dry spells were predominantly controlled by the AMO [

18].

Studies examining the influence of large-scale climatic oscillations—such as the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD), Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), Multivariate ENSO Index (MEI), Southern Oscillation Index (SOI), Indian Summer Monsoon Index (ISMI), Arctic Oscillation (AO), Sea Surface Temperature (SST), and the NAO—have provided important insights into rainfall variability. Results from India (1951–2015) demonstrated significant influences of these oscillations on monthly and interannual precipitation variability across meteorologically homogeneous regions [

28]. NAO-related impacts on European rainfall and drought under historical (1951–2000) and projected (2001–2100) scenarios revealed dominant relationships at 3–4-year periodicities, with an increased likelihood of drought under persistent positive NAO phases [

29]. Tatli and Menteş [

30] used the Merged Analysis of Precipitation (CMAP) dataset from the Climate Prediction Centre (CPC) to assess the relationships between climatic events over Europe, the Mediterranean Basin, North Africa, the Middle East, and the Caucasus with the NAO during 1979–2016. The analysis demonstrates that the negative phase of the NAO modulates heavy rainfall over Europe. In addition, negative correlation coefficients were observed in the western Mediterranean, Africa, and the western coasts of Eastern Europe. Statistical relationships between the NAO, AMO, and the rainfall regime in a representative area of the Mediterranean Basin (Tuscany Region) were analyzed using the Dickey–Fuller test and Spearman correlation. The results indicated that the circulation of humid air masses over Northern Europe and the Mediterranean is linked to the pressure gradient between high and low latitudes (NAO phase) and the Atlantic Ocean temperature (AMO index) [

31,

32]. Espinosa et al. [

33] analyzed rainfall trends and their relationship with the NAO on Madeira Island (Portugal) using nonparametric statistical correlations for the period 1940–2017. The results revealed a statistically significant downward trend in rainfall that can be directly attributed to the NAO climatic driver. The physical mechanisms underlying the effects of large-scale climate phenomena on Taiwanese rainfall variability were analyzed in [

34]. Empirical orthogonal function (EOF) and statistical analyses indicated the significant influence and critical roles of the PDO and SST on rainfall variability in Eastern Asia and Taiwan, showing a marked negative correlation between October–November rainfall and PDO and SST, opposite to rainfall variability observed in March. Significant relationships between teleconnection patterns and the spatiotemporal variability of daily rainfall concentration over the Mediterranean region during 1975–2015 were reported in [

15]. An inverse relationship exists between concentration indices and the number of rainy days. Moreover, the analysis showed that rainfall in the northwestern Mediterranean was strongly controlled by the Mediterranean Oscillation (MO) and the Western Mediterranean Oscillation (WeMO), with negative rainfall trends observed associated with positive NAO phases during 1975–1995. Zerouali et al. [

16] investigated possible links between the NAO, SOI, MO, and WeMO and rainfall variability in a humid Mediterranean region—the Sebaou Basin—during 1972–2010. Cross time–frequency analysis revealed significant relationships between rainfall and the NAO at 1-year, 1–3-year, and 3–5-year periods, with variability modes around 1980–1999 corresponding to the downward rainfall trend observed in the study area. The SOI, MO, and WeMO affected rainfall only locally, with significant associations for low-frequency events.

With the advent of the digital era in the late 1970s and the subsequent development of wavelet theory during the 1980s, Grossmann and Morlet [

35] established the foundational principles of the wavelet transform, enabling simultaneous characterization of time- and frequency-domain information. Since then, wavelet analysis has been widely adopted across numerous scientific fields; however, its application in climatology has expanded more slowly due to the relatively complex mathematical framework required [

36]. The selection of an appropriate wavelet strongly depends on the analytical objectives and the user’s methodological familiarity, with approaches ranging from basic to cross-timescale techniques [

37]. In hydrology, wavelet analysis has become increasingly important for detecting nonlinear and nonstationary behaviors of hydrological phenomena in environmental time series such as temperature, rainfall, flow rates, and climatic indices [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]. For example, using continuous wavelet and discrete wavelet analyses, Labat et al. [

43] successfully characterized the nonlinear and nonstationary rainfall–runoff relationships of karstic springs in Larzac (Aveyron, France). According to Chinarro et al. [

44], wavelet analysis clearly characterized the temporal variability and nonlinear, nonstationary systems of the Fuenmayor–San Julián de Banzo karst aquifer in Huesca, Spain. Based on several wavelet approaches, Zerouali et al. [

16] concluded that the relationships among the NAO, SOI, MO, WeMO, and rainfall in northern Algeria were characterized by the dominance of short-term phenomena that obscure long-term processes, whose effects occur over distant (low-frequency) timescales. Wavelet coherence analysis has also revealed significant relationships between interannual rainfall variability in the Tensift and Ksob basins (Morocco) and the NAO during the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, particularly within the 6–8-year and 8–12-year energy bands [

45]. Nalley et al. [

46] applied a multiscale and multivariate analysis to assess rainfall and streamflow variability in relation to the NAO, PDO, and ENSO, demonstrating that the strongest coherence occurred at decadal components (128 months), with the positive phase associated with drier conditions and vice versa.

Advances in multiresolution wavelet tools have also led to the development of hybrid wavelet–artificial intelligence methods designed to predict the future hydrological characteristics of river basins [

47,

48,

49,

50]. Using different wavelet families, the neuro-fuzzy approach has been evaluated for daily flow rate forecasting. The results of the proposed models were very encouraging, with the Daubechies mother wavelet (db7) demonstrating superior performance [

48].

In the last five years, multiresolution wavelet analysis has increasingly been used to improve the precision of change-point and trend detection methods in hydroclimatic series. Zerouali et al. [

51] applied relatively new hybrid methods combining the Bayesian change-point approach (BA), Şen’s Innovative Trend Method (ITM), and its double (D-ITM) and triple (T-ITM) versions with the discrete wavelet transform (DWT) for detecting trends and change points in rainfall series across northern Algeria. The results revealed that the information obtained from the DWT increased the precision of these methods in identifying hidden trends and change points. In the Onkaparinga catchment (Australia), Rashid et al. [

52] applied the Mann–Kendall (MK) test in conjunction with the continuous wavelet transform (CWT) to annual and seasonal monthly rainfall data, showing that the periodic components derived from the CWT accounted for the largest share of trends compared with the original data.

Since the 1970s, the NAO phenomenon has predominantly remained in a positive phase, which is one of the factors responsible for the occurrence of dry conditions across the Mediterranean Basin, southern Europe, and northern Africa. These persistent dry periods can significantly affect agricultural yields and the sustainability of water resources. Despite its importance, investigations of NAO impacts in Algeria remain limited. For example, Zerouali et al. [

53] used canonical correlation analysis to assess rainfall and temperature trends in northern Algeria and their relationships with NAO, WeMO, MO, and SOI teleconnection patterns. The analysis showed that WeMOI and SOI were especially strongly correlated with rainfall and temperature, respectively. Taibi et al. [

54] reported that rainfall seasonality was relatively linked to the MOI, with a significant negative correlation with the winter NAO. Drought sequences in the Cheliff watershed (Algeria) and their relationships with MO, SOI, and AMO were analyzed in [

55], revealing that the western areas, characterized by the longest dry-spell durations, were strongly correlated with AMO, whereas total dry-day counts were negatively correlated with SOI.

In the present study, the nonlinear relationships between monthly NAO indices and rainfall in northern Algeria were analyzed for the period 1970–2009, scale by scale, using a cross-multiresolution analysis based on seven wavelet families—Daubechies, Biorthogonal, Reverse Biorthogonal, Discrete Meyer, Symlets, Coiflets, and Fejer–Korovkin—comprising a total of 106 wavelets. More than 700 cross-correlation computations were performed to identify the wavelet family that best represents NAO–rainfall interactions across scales.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. NAO Index

The NAO—first identified by Sir Gilbert Walker during his early investigations into large-scale climate teleconnections—is a principal pattern of atmospheric variability over the North Atlantic region. It reflects fluctuations in the atmospheric pressure difference between the subtropical Azores High and the subpolar Icelandic Low [

56,

57]. Variations in this pressure dipole regulate the strength and trajectory of the prevailing westerlies and their associated storm tracks, thereby shaping climatic conditions across Europe, the Mediterranean, and North Africa.

The NAO index, used to quantify this variability, is typically calculated from the standardized difference in sea-level pressure between representative stations in the Azores (e.g., Ponta Delgada) and Iceland (e.g., Reykjavik). During positive NAO phases, an enhanced pressure gradient strengthens westerly flow, producing warmer and wetter conditions over northern and central Europe, while causing drier conditions in the Mediterranean and North Africa due to a poleward displacement of storm systems [

19,

58,

59]. Conversely, the negative phase is associated with weakened gradient, leading to a southward displacement of storm systems, increased precipitation, and cooler temperatures in southern Europe and northern Africa, particularly Algeria. Given its pronounced influence on interannual to decadal climate variability, the NAO plays a critical role in shaping regional hydrological extremes, droughts, and water resource management across Mediterranean and semi-arid climates [

17,

45,

56,

60].

2.2. Study Area and Databases

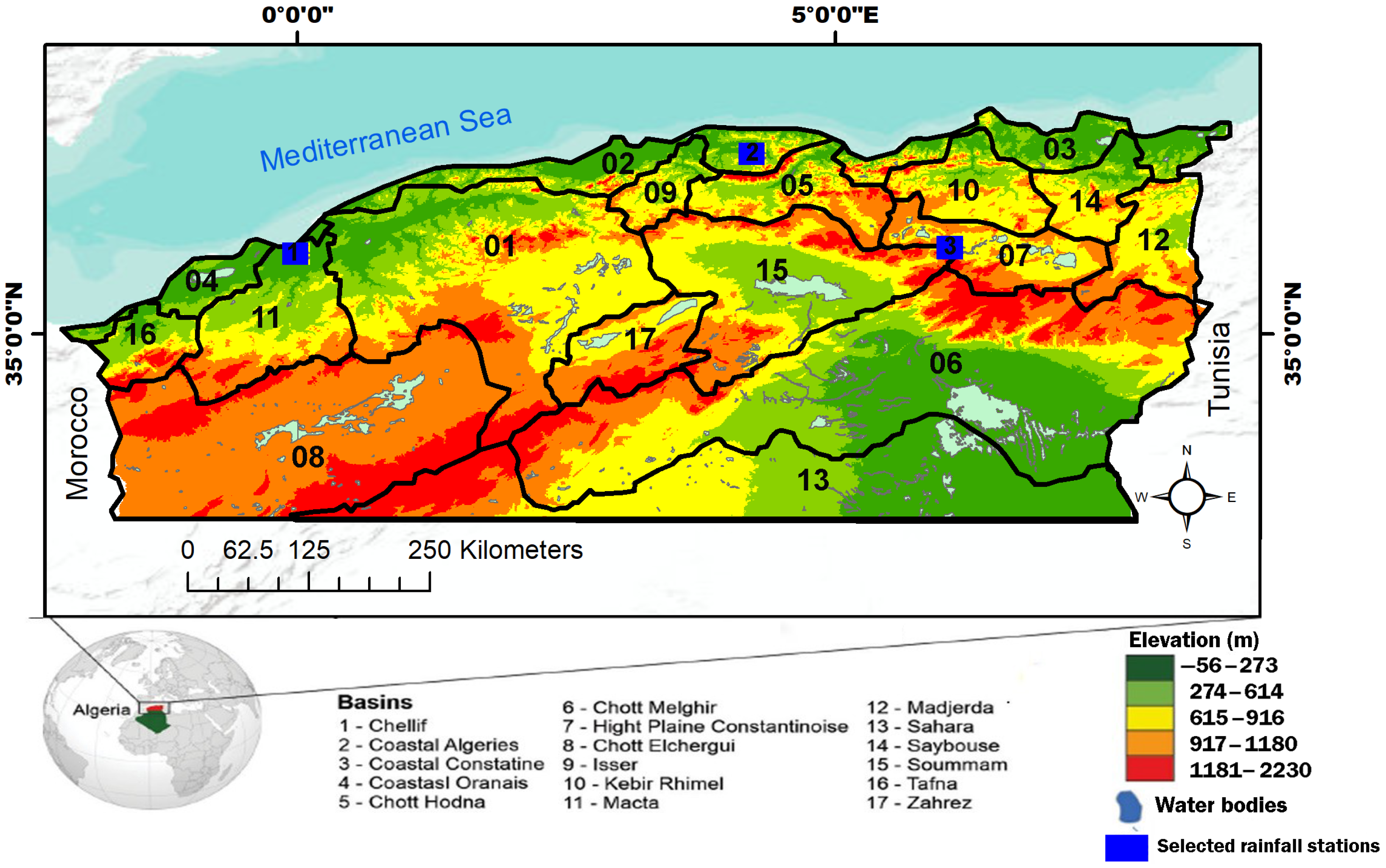

This study utilizes monthly rainfall data from 1970 to 2009, collected from three representative rain gauge stations located in the northern and northeastern regions of Algeria (

Figure 1 and

Table 1). Northern Algeria is characterized by a Mediterranean climate with mild winters, hot summers, abundant sunshine, and frequent high winds. Rainfall occurs only on a few days each year and is irregularly distributed throughout the year. Owing to Algeria’s large latitudinal and topographic extent, climatic conditions vary considerably, with Mediterranean influences dominating the northern belt, while the rest of the country predominantly exhibits arid desert climates.

Three rain gauge stations were selected for the monthly scale to evaluate rainfall variability and explore the possible drivers of recent changes in precipitation regimes in northern Algeria. This study also contributes to the limited number of research efforts focused on this specific geographic region. All data were provided by the National Agency of Hydraulic Resources (ANRH).

Mostaganem (SCM) Station: Located within the coastal Oran Basin, this station lies north of the Tafna, Macta, and Chott Chergui basins. It is bounded to the north by the Mediterranean Sea. Elevation ranges from 15 m (near the coast) to 1061 m in the Traras Mountains. The Oran Basin covers 5913 km2, representing 7.65% of the total surface area of the hydrographic region (ABH 2020).

Beni Yenni Station: This station is situated in the Oued Sebaou Basin (36°30′ N and 37°00′ N; and 03°30′ E and 04°30′ E), covering approximately 2500 km2. It is bordered by the Mediterranean coast to the north, the Djurdjura mountain chain to the south, the Akfadou and Beni Ghobri massifs to the east, and the Sidi Ali and Jebel Bounab Bouberak mountains to the west.

Timgad Station: Situated within the High Plains of Constantine watershed in the eastern steppe highlands (35°44′–36°15′ N; 5°57′–7°80′ E), this basin forms part of the Constantine–Seybous–Mellague system and spans over 9600 km2. It includes several saline continental depressions, such as chotts and sebkhas, and comprises seven sub-watersheds: Chott Beida, Medja Zana, Sebkhet Ez Zemoul, Oued Chemora, Garaet An Djamal, Oued Boulfreis, and Gareat El Tarf.

In northern Algeria, dry northwesterly winds originating over Spain and the Moroccan Atlas Mountains gain moisture from the Mediterranean Sea before reaching the Tell Atlas Mountains, where they produce substantial orographic rainfall. Rainfall intensity decreases from north to south but increases from west to east, making the Oued Sebaou Basin one of the most water-abundant systems in the region.

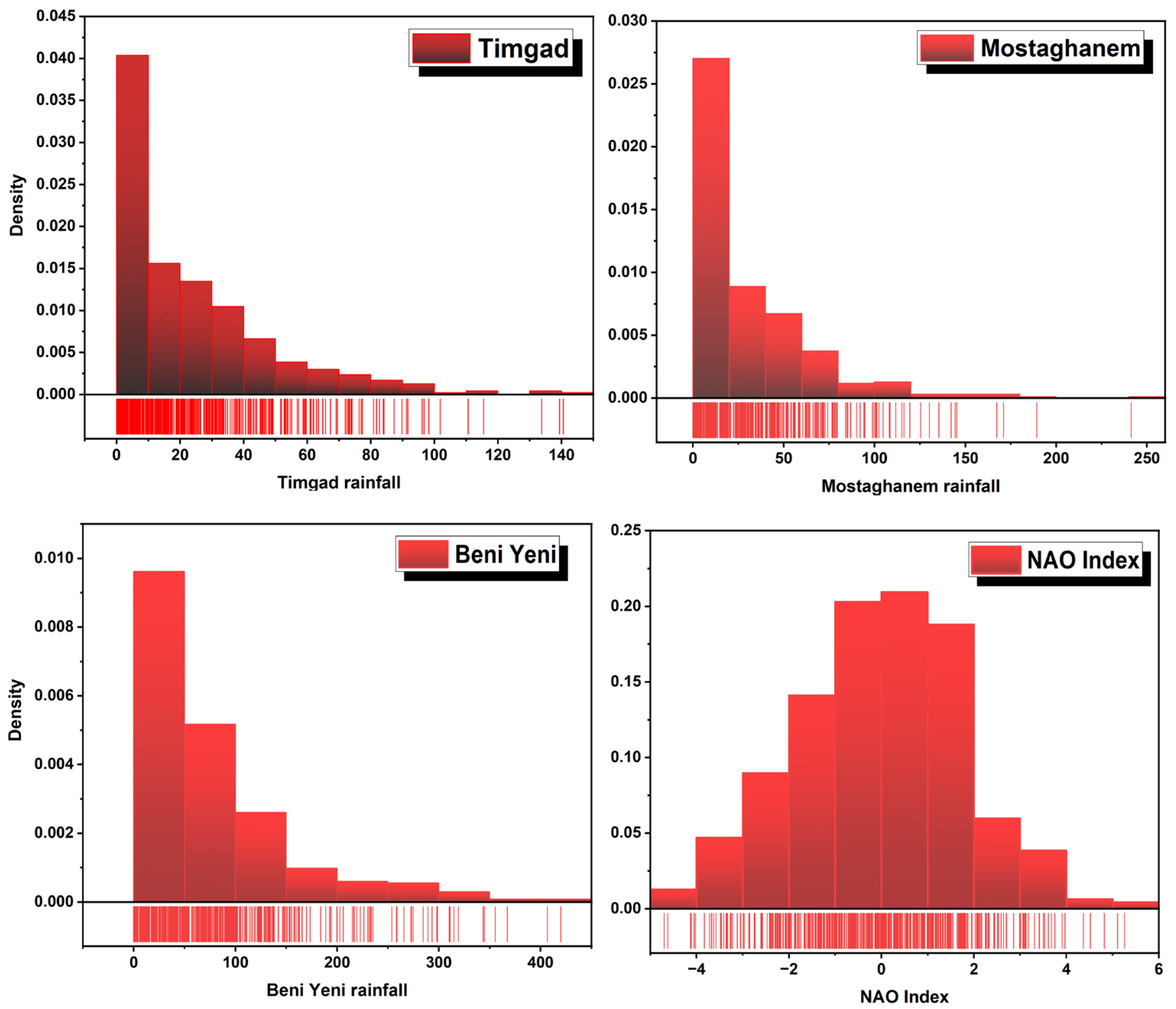

Figure 2 illustrates the density distribution of rainfall amounts at Timgad, Mostaganem, and Beni Yenni, alongside the NAO index. Timgad shows a peak at lower rainfall values, indicating that lighter rains are more common, with fewer instances of heavy rainfall. Mostaganem has a comparable distribution but with a slightly broader representation of heavier rainfall. In contrast, Beni Yenni displays a pronounced peak at moderate rainfall levels, suggesting a more balanced distribution of light and moderate precipitation, indicative of a consistent rainfall pattern. The NAO index distribution reveals a concentration around zero, suggesting that neutral NAO conditions are prevalent, which may correlate with typical weather patterns in the region. The spread of the NAO index highlights variability in atmospheric conditions that could influence regional rainfall. These findings imply that areas with higher rainfall variability, such as Beni Yenni, might be more susceptible to changes driven by specific NAO phases. Overall, the predominance of lower rainfall amounts across most areas suggests a dependence on seasonal weather patterns influenced by the NAO, emphasizing the importance of examining the interplay between NAO conditions and local precipitation to improve climate projection and water resource planning.

Table 2 summarizes the statistical parameters of rainfall records from Timgad, Mostaganem, and Beni Yenni, along with the NAO index, providing insights into the rainfall characteristics across these sites. Beni Yenni exhibits the highest maximum rainfall (420 mm), indicating significant extreme events compared to Timgad (140.6 mm) and Mostaganem (241.4 mm). This pattern is consistent with the mean rainfall, where Beni Yenni also shows the greatest average precipitation 74.63 mm), followed by Mostaganem (28.31 mm) and Timgad (23.55 mm), suggesting that Beni Yenni experiences more substantial average precipitation.

The variance and standard deviation metrics further reinforce this finding. Beni Yenni displays the highest variance (6028.645) and standard deviation (77.64), highlighting considerable variability in its rainfall amounts. Mostaganem shows a moderate variance of 1198.07 and a standard deviation of 34.61, while Timgad has the lowest variance (641.47) and standard deviation (25.33), indicating less variability in extreme rainfall events. The coefficient of variation (CV) is similar for Timgad (1.08) and Beni Yenni (1.04), suggesting consistent variability relative to their means, while Mostaganem, with a CV of 1.22, demonstrates a relatively greater degree of variation.

Distribution of distinct rainfall characteristics. Positive skewness values in Timgad (1.6) and Beni Yenni (1.04) exhibit right-tailed distributions dominated by low to moderate rainfall with occasional extremes. Mostaganem exhibits the highest skewness (1.98), indicating an even greater tendency towards extreme rainfall events. The kurtosis values further illustrate the nature of the distributions, with Mostaganem showing a kurtosis of 5.44, indicative of a distribution with heavy tails and a sharper peak, suggesting a higher frequency of extreme events compared to Timgad and Beni Yenni.

Conversely, the NAO index reveals a maximum of 5.26 and a minimum of −4.7, with a mean close to zero (−0.05), indicating oscillation around neutral conditions. Its low variance (3.19) and standard deviation (1.79) suggest stability in NAO variations, while a negative CV (−37.57) highlights an unusual distribution pattern. Overall, the statistical parameters emphasize the distinct rainfall characteristics across the three stations, with Beni Yenni showing the most substantial variability and extremes. Meanwhile, the relative stability of the NAO index suggests that additional climatic controls likely contribute to the spatial rainfall patterns observed in the region.

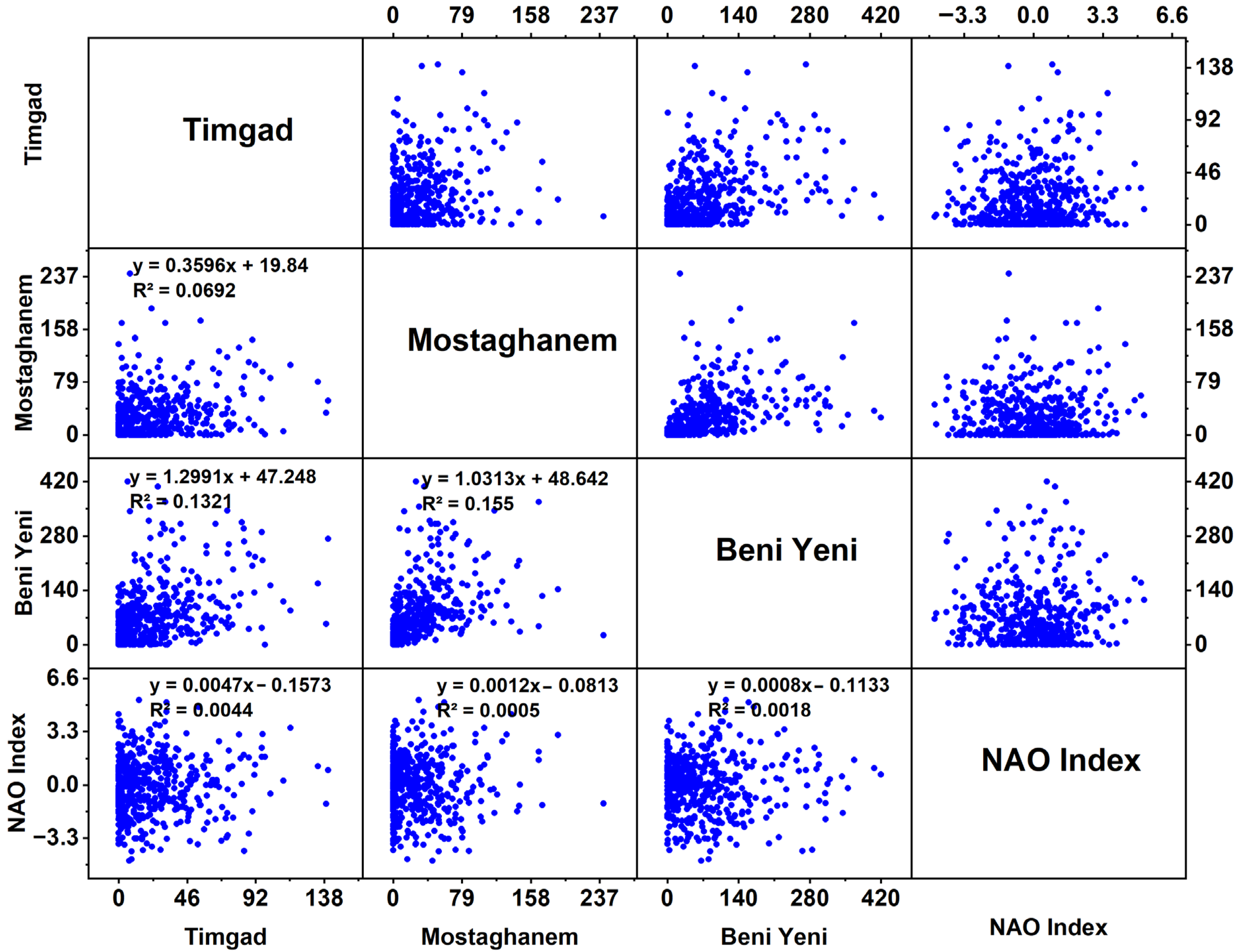

The scatter plot matrix (

Figure 3) illustrates the interrelationships among rainfall amounts at Timgad, Mostaganem, and Beni Yenni, alongside the NAO index. The correlation between Timgad and Mostaganem is weak (R

2 = 0.062), indicating that rainfall amounts in these two regions do not significantly influence each other. Similarly, Timgad and Beni Yenni also exhibit a weak correlation (R

2 = 0.131), suggesting limited interaction in rainfall patterns between these locations. In contrast, the correlation between Mostaganem and Beni Yenni is slightly stronger (R

2 = 0.155), indicating a minor relationship in their rainfall amounts. The scatter plots involving the NAO index show very weak correlations with the rainfall data from all three locations (R

2 values are close to zero), suggesting that variations in the NAO index do not significantly impact rainfall amounts in Timgad, Mostaganem, or Beni Yenni. Each scatter plot reveals a clustering of points, particularly at lower rainfall amounts, consistent with earlier findings of rainfall distribution across these stations. The presence of outliers in some plots may indicate occasional extreme rainfall events. Overall, the matrix underscores the weak correlations between rainfall amounts among the three stations and the NAO index, suggesting that other climatic or local factors may be more influential in determining rainfall patterns in these regions. Further investigation of these drivers could provide deeper insights into the mechanisms underlying spatial and temporal precipitation variability.

Our analysis, therefore, focuses on selecting an appropriate wavelet family to investigate the nonlinear relationships between the NAO and rainfall in northern Algeria. Given the weak correlations observed in the scatter plot matrix, it is essential to employ advanced analytical techniques capable of capturing nonlinear dynamics and intricate patterns that traditional methods may overlook. Through wavelet analysis, the underlying relationships between the NAO and regional rainfall can be revealed, thereby improving the understanding of climate-driven factors in this region. This approach enhances the ability to model and forecast rainfall patterns, ultimately supporting more effective water resource planning and climate adaptation strategies across northern Algeria.

2.3. Cross Discrete Wavelet Analysis

The DWT is a robust and widely used method for analyzing nonstationary time series by decomposing signals into a set of orthonormal basis functions known as wavelets [

61,

62,

63]. Unlike the continuous wavelet transform (CWT), which provides a redundant and highly detailed representation, the DWT offers a compact, no redundant representation that is computationally efficient and particularly suitable for large datasets. The DWT operates by successively applying a pair of filters—a high-pass filter to extract detail coefficients and a low-pass filter to extract approximation coefficients—followed by downsampling [

62]. This process, repeated across multiple levels, enables the decomposition of the original signal into different frequency components, each associated with a specific timescale. The approximation coefficients capture the long-term trends or low-frequency components, while the detail coefficients reveal short-term variations or high-frequency fluctuations. This multiscale framework is particularly advantageous for detecting discontinuities, trends, and hidden periodicities in climatological and hydrological time series [

64]. In this study, DWT was employed with various wavelet family functions, chosen for their high number of vanishing moments and ability to effectively capture both smooth and transient features in the data.

The discrete wavelet transform (DWT) is grounded in the principles of multiresolution analysis (MRA), wherein a signal

is projected onto a hierarchy of nested approximation spaces

and detail spaces

, such that

At each decomposition level

, the signal is represented as the sum of an approximation

, capturing low-frequency components, and details

, which capture the high-frequency fluctuations [

63]. These components are obtained through convolution with a low-pass filter

and a high-pass filter

, respectively, followed by downsampling:

The original signal can be reconstructed as

where

is the maximum level of decomposition. In this study, the Daubechies 20 (db20) wavelet was selected due to its compact support and high regularity, which enables precise localization of signal features across both time and frequency domains. This framework provides a robust basis for analysing climatological time series by isolating cyclical components, abrupt changes, and long-term trends at distinct temporal scales.

The integration of cross-discrete wavelet transform (XDWT) and cross-correlation analysis provides a robust framework for investigating multiscale interactions between nonstationary time series. While cross-correlation quantifies linear dependencies at fixed lags, XDWT localizes these relationships in time–frequency space, revealing scale-specific synchronizations [

65]. Given two signals

and

, their cross-correlation

at lag

is computed as

where

months in this study. A peak at

month (

Figure 4a) indicates that

systematically lags

by one month, likely reflecting hydrological delays (e.g., precipitation-to-runoff response). However, cross-correlation alone cannot discern whether this lag is uniform across temporal scales or driven by specific frequency bands.

To address this, XDWT decomposes both signals into orthonormal wavelet components using the various wavelet families’ basis, yielding approximation (

) and detail (

) coefficients at each level

. The cross-wavelet power

at scale

and time

is then derived as

where

and

are the DWT coefficients of

and

, respectively. Finally, cross-correlation identifies global lags efficiently. XDWT localizes these lags to specific processes (e.g., seasonal vs. decadal), avoiding misinterpretations from aggregated time-domain analysis. Cross-correlation gives a time-domain linear relationship, while XDWT provides time–frequency localized insights (

Table 3):

In the DWT, each decomposition level represents a dyadic scale that doubles in temporal width relative to the previous level, following . The corresponding time period is, therefore, directly related to the sampling interval of the input series. As the rainfall and NAO data in this study are monthly, the decomposition levels correspond approximately to 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, and 128 months for D1 through D7, respectively. This means that D1–D2 captures high-frequency fluctuations (2–4 months), while D6–D7 and D7–A7 represent decadal-scale variability (≈64–128 months). When applied to annual data, the same principle yields scales of 2–128 years, highlighting the generality of this dyadic framework.

The XDWT framework thus serves as a rigorous mathematical basis for exploring dynamic teleconnections and nonlinear interactions in hydrometeorological datasets.

Given the inherent complexity and nonlinearity of climatic processes, such as the interaction between the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) and regional rainfall patterns, wavelet analysis emerges as a powerful tool for time–frequency decomposition and multiscale analysis. However, the performance and sensitivity of the wavelet transform largely depend on the choice of the mother wavelet. Each wavelet family has distinct mathematical properties—such as symmetry, support width, regularity, and vanishing moments—that influence its ability to capture transient features and periodic structures in the data. This study focuses on selecting the most suitable wavelet family for assessing the nonlinear and nonstationary relationship between the NAO index and monthly rainfall over northern Algeria. We evaluate seven wavelet families with 106 wavelets in total (Daubechies, Biorthogonal, Reverse Biorthogonal, Discrete Meyer, Symlets, Coiflets, and Fejer–Korovkin), performing more than 700 cross-correlation analyses between each pair of NAO–rainfall (

Table 4). This comprehensive evaluation aims to identify the wavelet family that best explains the underlying relationships and provides the most robust representation of NAO–rainfall interactions. By systematically testing a wide range of wavelet families, this research addresses a significant methodological gap in climate teleconnection studies and supports the development of more accurate, region-specific climate models.

Table 5 summarizes the characteristics of seven wavelet families used to analyze the nonlinear relationships between the NAO and rainfall in northern Algeria. These families—Daubechies, Biorthogonal, Reverse Biorthogonal, Coiflets, Symlets, Discrete Meyer, and Fejer–Korovkin—differ in terms of orthogonality, biorthogonality, symmetry, compact support, and zero moments. While Daubechies is compact and orthogonal, Biorthogonal and Reverse Biorthogonal offer biorthogonality and symmetry. Coiflets and Symlets balance orthogonality and symmetry, and Discrete Meyer provides a combination of all key features. Fejer–Korovkin offers similar properties but is unique in its approach. For example, the Daubechies family (denoted as db) is known for its orthogonality and compact support but lacks symmetry. Its arbitrary zero moments make it versatile, although it might not perform optimally in capturing certain symmetrical features of the data. The Biorthogonal family (bior) offers biorthogonality, symmetry, and compact support, which can be advantageous in reconstructing the signal, especially for applications requiring accurate signal recovery. Similarly, the Reverse Biorthogonal family (rbior) shares these attributes, making it suitable for various signal processing tasks. Overall, these wavelet families offer a diverse set of tools, each with distinct advantages depending on the characteristics of the NAO and rainfall relationship. The choice of wavelet family plays a crucial role in capturing the underlying nonlinear dynamics and ensuring accurate representation of the data’s temporal and spatial structures. The detailed evaluation of these wavelet families will guide the selection of the most appropriate family for analyzing the NAO–rainfall interactions in northern Algeria.

Because the objective of this study is diagnostic comparison among wavelet families rather than independent significance testing, formal multiple-comparison corrections (e.g., Bonferroni or FDR) were not applied. Correlations between NAO and rainfall are interdependent across scales and wavelets, sharing overlapping frequency content. Robustness was evaluated instead by consistency of correlation patterns across scales, wavelet families, and stations, ensuring that only physically coherent relationships were interpreted as meaningful.

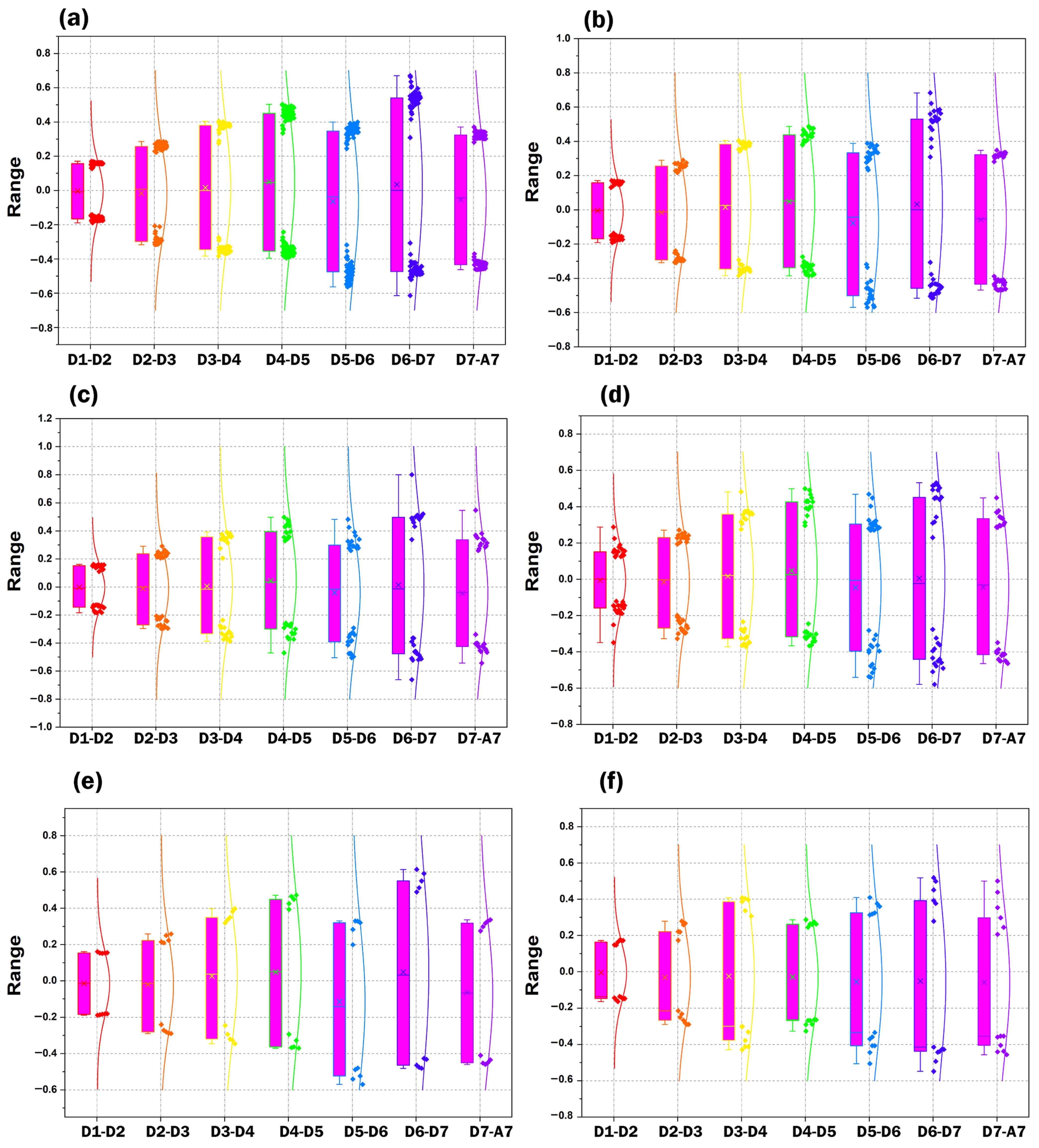

3. Results

The decomposition of the NAO and rainfall time series using the discrete wavelet transform (DWT) enables the extraction of distinct frequency-based components, each linked to specific climatic behaviors. The decomposition levels D1–D2 and D2–D3 reflect short-term seasonal fluctuations (2–4 and 4–8 months), respectively, while D3–D4 captures annual variations (8–16 months). Intra-annual and multiannual variabilities are represented by D4–D5 (16–32 months) and D5–D6 (32–64 months), respectively. Decadal-scale oscillations are observed in D6–D7 (64–128 months), and the D7–A7 component highlights long-term trends beyond 128 months (

Figure 4). The search for correlations between the NAO and rainfall was carried out across these multiscale components, facilitating the identification of localized, scale-dependent relationships. This multiresolution framework provides a robust basis for analyzing the temporal dynamics and co-evolution of the NAO–rainfall interactions, thereby offering valuable insights into the nonlinear climate-rainfall coupling mechanisms affecting northern Algeria.

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 illustrate the results obtained for the Beni Yenni rain gauge, which is presented as a representative example due to the similarity of the cross-multiresolution patterns observed across the three study stations. The NAO–rainfall correlation structures for Mostaganem (SCM) and Timgad exhibited comparable behaviors across all scales, differing mainly in amplitude rather than form. To avoid redundancy and to preserve clarity, only the Beni Yenni case is shown in detail, while

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 provide a synthesized summary of the optimal wavelet families and corresponding results for Mostaghanem and all sites, respectively.

The robustness of the wavelet-derived correlations was evaluated using a distribution-based approach, illustrated in

Figure 4. The boxplots show the variability of maximum positive and negative correlations across the seven decomposition-level pairs for each wavelet family. The coherent structure of these distributions—particularly the enhanced ranges observed in the D5–D7 bands—confirms that the detected NAO–rainfall couplings are systematic rather than random. If the relationships were noise-driven, the correlation ranges would fluctuate randomly and remain centered near zero. The observed stability across scales and wavelet families, therefore, provides an implicit nonparametric validation, indicating that the “hidden relationships” revealed by the cross-wavelet framework reflect genuine climatic coherence rather than stochastic artifacts.

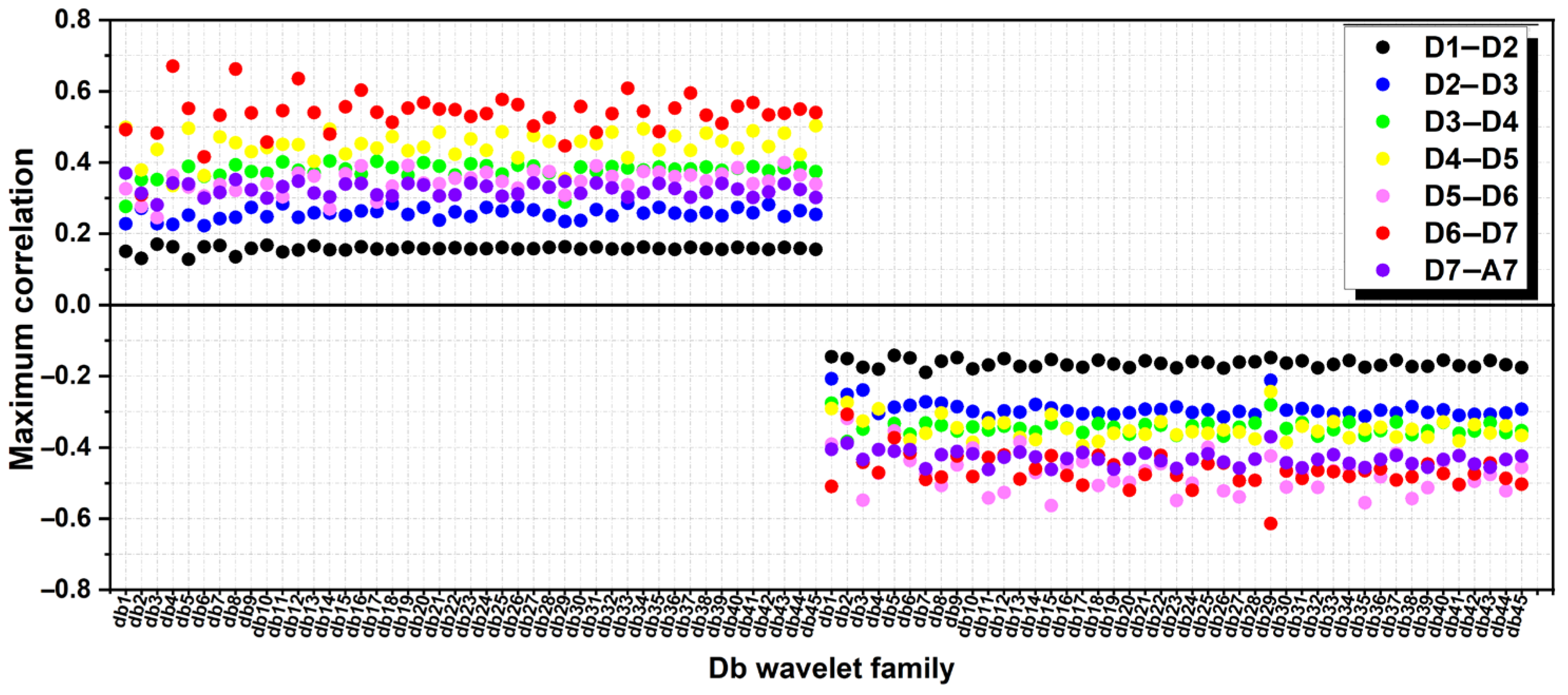

The cross-correlogram analysis presented in

Figure 5 highlights the scale-dependent relationship between the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) and rainfall at the Beni Yenni rain gauge using various Daubechies wavelets. Among the tested mother wavelets, Db7 emerged as the most effective, capturing a maximum positive correlation of approximately 0.67 at the D6–D7 scale (64–128 months), which corresponds to decadal variability. This indicates a strong temporal coherence between NAO fluctuations and rainfall during this timespan. Similarly, Db4 also demonstrated a robust correlation of around 0.60 at the D4–D5 scale (16–32 months), highlighting the relevance of intra-annual dynamics. Furthermore, Db34 to Db35 showed consistent performance across broader scales, particularly at the D5–D6 scale (32–65 months), reflecting its utility in capturing long-term decadal interactions. On the negative side, wavelets such as Db3, Db15, and Db29 exhibited strong inverse correlations at shorter seasonal scales (e.g., D2–D3, D5–D6, and D7–A7), indicating anti-phased behavior between the two signals. Overall, Db29 and Db30 stand out as the most suitable mother wavelets for analyzing the nonlinear and scale-dependent NAO–rainfall relationship in this region, where the intra-annual and decadal components are the most significant based on Daubechies wavelets.

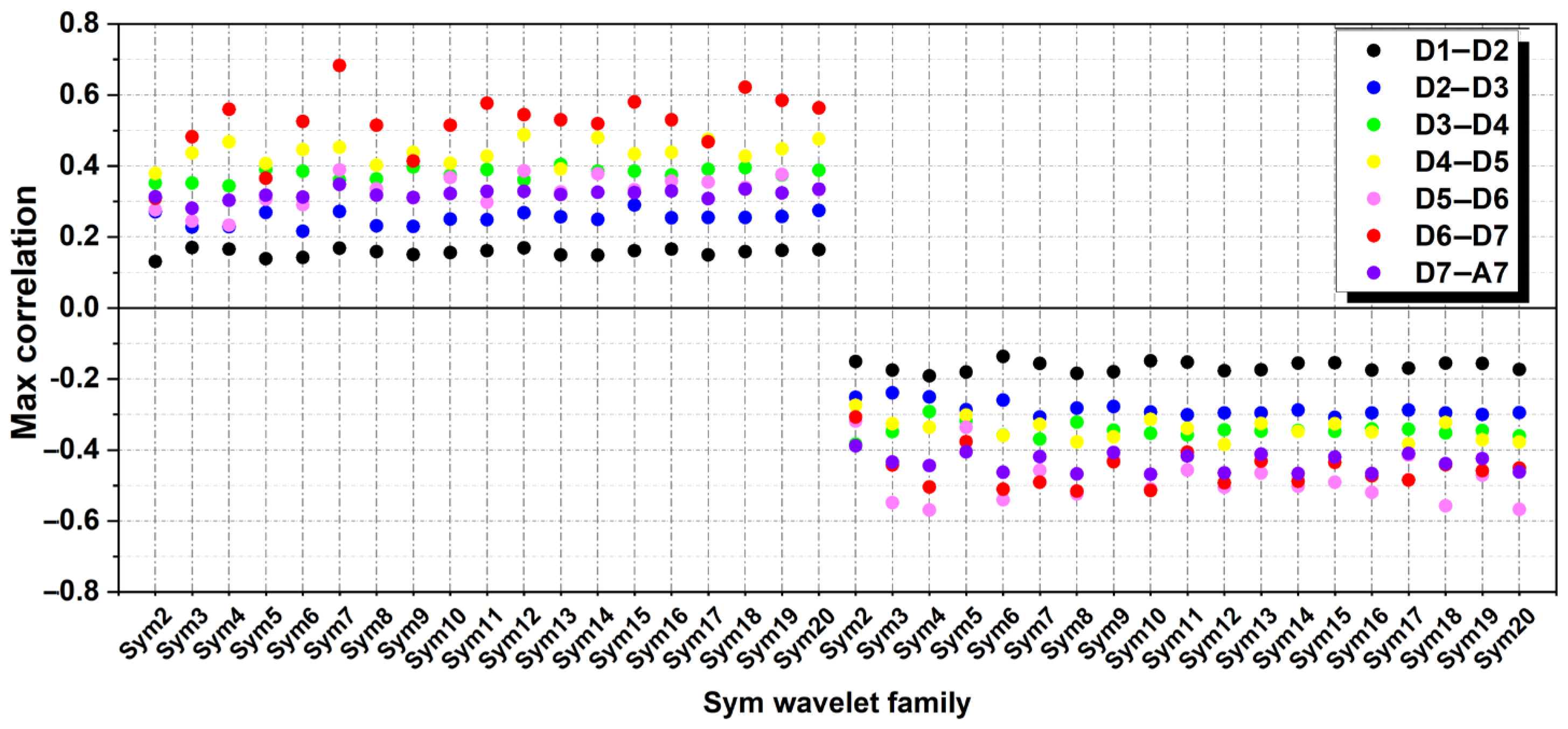

Based on the maximum values of cross-correlogram analysis across different temporal scales (

Figure 6) using Symlet wavelets for the Mostaganem rain gauge, clear scale-dependent correlations between NAO and rainfall were observed. At the seasonal scales (D1–D2 and D2–D3), correlations remained relatively weak across all Symlets, with values not exceeding ±0.19 for D1–D2, and ranging between 0.2 to 0.3 and −0.2 to −0.3 for D2–D3, indicating limited coupling during short-term fluctuations. More notable correlations begin to emerge at D3–D4 (8–16 months, annual scale), where Sym7 and Sym14 to Sym20 recorded positive correlations ranging from 0.35 to 0.4, while negative correlations reached −0.37. These results suggest that the influence of NAO on rainfall at the annual cycle is better captured with higher-order Symlets. A stronger relationship appears at D4–D5 (16–32 months), where Sym4, Sym12, and Sym14 produced a maximum positive correlation of 0.49 and a maximum negative correlation of −0.39, indicating significant intra-annual coherence. The most substantial coupling was observed at D6–D7 (64–128 months, decadal scale), particularly with Sym4, Sym6, Sym7, and Sym8, where the maximum positive correlation reached 0.69, while the negative correlation reached −0.52, highlighting this scale as critical for long-term NAO influence on rainfall. At the trend component D7–A7, correlations remained moderate (between 0.3 to 0.4 and −0.4 to −0.5) across all Symlet wavelets, reflecting more diffuse but still relevant long-term relationships. Overall, Sym4, Sym7, and Sym8 stood out as particularly effective mother wavelets, especially at the decadal and intra-annual scales, where the NAO–rainfall coupling was most pronounced.

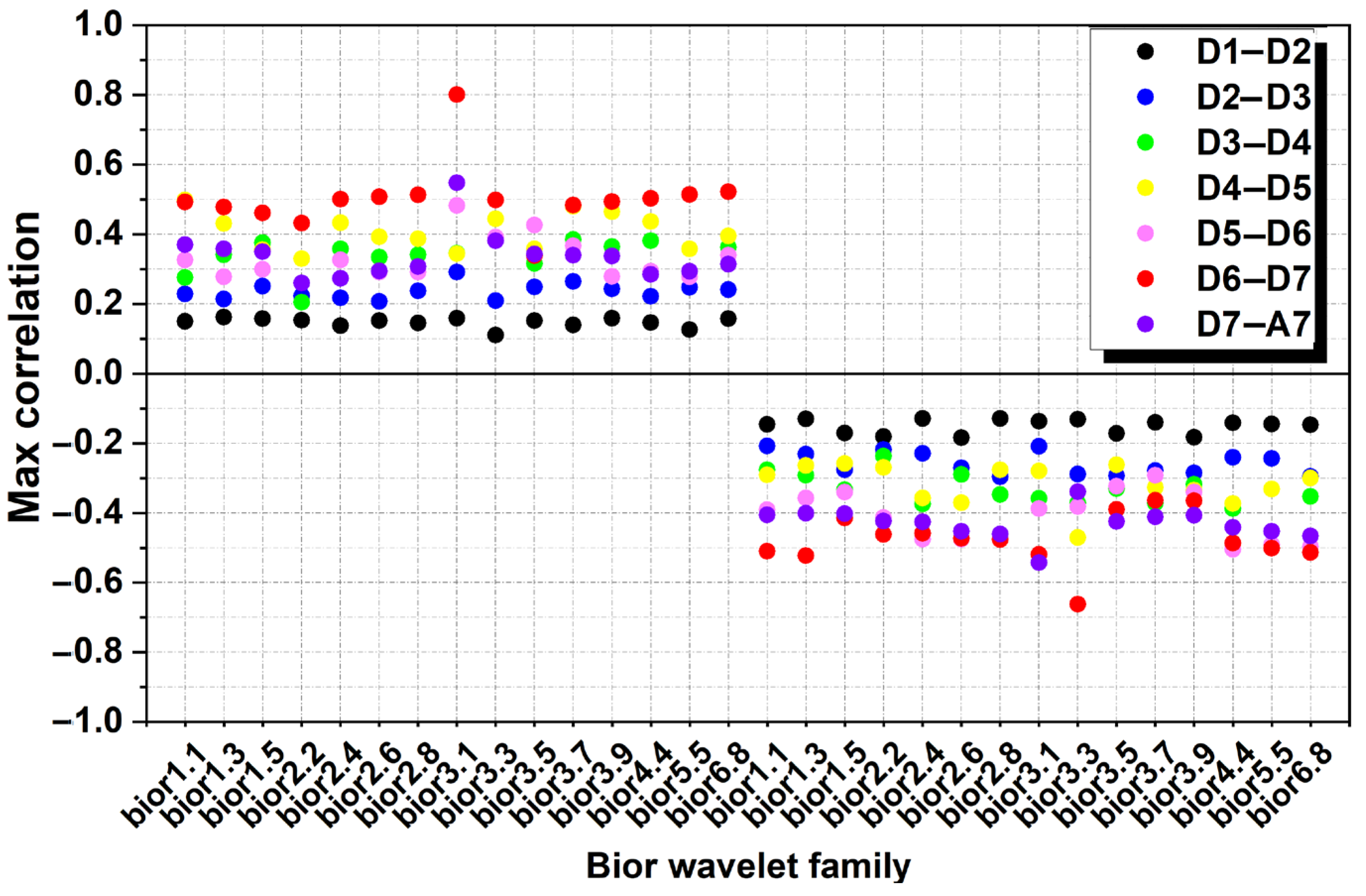

The cross-correlation analysis using biorthogonal wavelets at the Beni Yenni rain gauge reveals a distinct scale-sensitive behavior in the NAO–rainfall relationship (

Figure 7). At the shortest timescales (D1–D2), all biorthogonal wavelets exhibited low-to-moderate correlations, with both positive and negative values not exceeding ±0.2, reflecting weak seasonal coherence. Between D2 and D3 (4–8 months), specific wavelets like bior3.1, bior3.3, bior3.7, and bior3.9 showed modest correlations ranging from ±0.2 to ±0.3, again indicating limited but noticeable interactions at short-term seasonal fluctuations. Annual-scale coupling at D3–D4 was more significant with bior1.5, bior3.7, bior3.1, and bior4.4, yielding maximum correlation values around ±0.39. This highlights the growing importance of NAO influence over annual rainfall variability. Stronger correlations emerged at D4–D5 (intra-annual scale), particularly with bior1.3, bior2.4, bior2.6, bior3.3, bior3.9, and bior4.4, where positive and negative peaks reached ±0.49—an indication of increased coherence. A noteworthy result appeared at D5–D6, where bior1.3 alone showed strong correlation values up to ±0.49 (positive) and −0.40 (negative), suggesting its specificity in detecting multiannual patterns. The most remarkable correlations were recorded at the decadal scale (D6–D7) with bior1.3 and bior3.3, reaching a maximum positive correlation of 0.8 and a negative peak of −0.68. This marks the strongest coupling across all wavelet families analyzed, underscoring these wavelets’ potential to detect deep long-term dynamics between NAO and rainfall. Interestingly, at the long-term trend level (D7–A7), only bior3.3 displayed significant correlation, with both positive and negative values stabilizing around −0.52, revealing a persistent inverse trend relationship. In summary, bior1.3 and bior3.3 emerge as the most suitable mother wavelets within the biorthogonal family, particularly effective in capturing decadal and multiannual dynamics of the NAO–rainfall relationship.

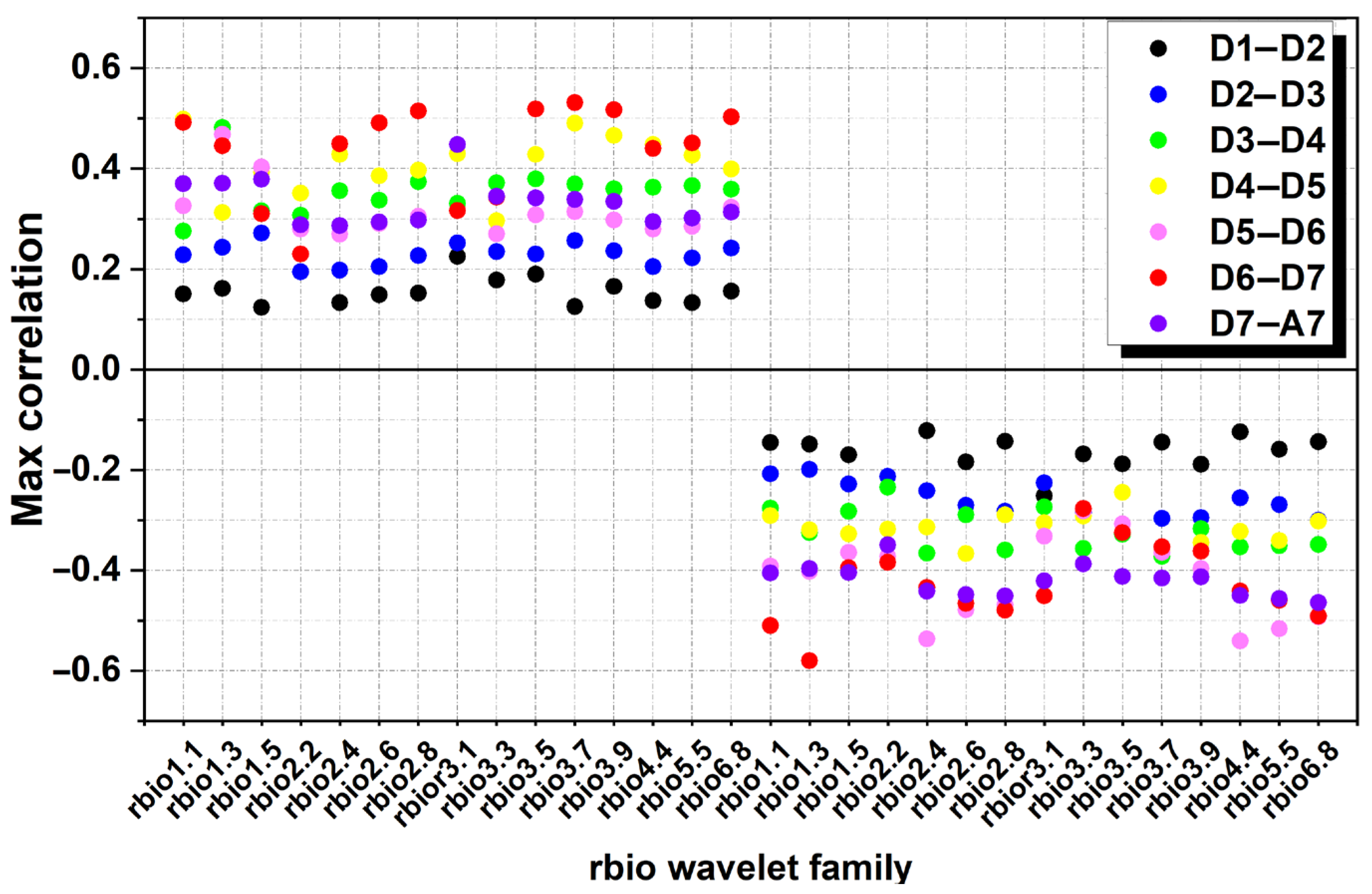

The analysis of the correlations between the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) and rainfall, utilizing various reverse biorthogonal wavelets, reveals significant insights into their interactions across different temporal scales (

Figure 8). At the short-term scales (D1–D2 and D2–D3), the correlations are relatively weak, with maximum positive values reaching only 0.22 to 0.28 and negative values around −0.27 to −0.30, indicating limited seasonal coherence. The mother wavelets used at these scales include rbio3.1 and rbio1.5 for D1–D2, and rbio1.5, rbio3.7, and rbio3.9 for D2–D3. However, as we move to the annual scale (D3–D4), a notable increase in positive correlations is observed, ranging from 0.30 to 0.39, alongside a negative correlation peaking at −0.37. This suggests a growing influence of the NAO on rainfall patterns during this period, with mother wavelets such as rbio2.4, rbio2.8, and rbio3.5 to rbio6.8 being particularly effective.

The intra-annual variability scale (D4–D5) displays even stronger coherence, with positive correlations peaking at 0.49 and negative correlations at −0.38, utilizing mother wavelets like rbio2.6, rbio3.7, and rbio3.9. This trend of increasing correlation continues into the multiannual (D5–D6) and decadal scales (D6–D7), where the strongest coupling is recorded, with maximum positive correlations of 0.48 and 0.52, respectively, and significant negative correlations of −0.52 and −0.59. The key mother wavelets for these scales include rbio3.1, rbio2.4, and rbio1.3. Finally, at the long-term trend level (D7–A7), moderate correlations of 0.45 and −0.49 reflect persistent relationships between NAO fluctuations and rainfall, with mother wavelets such as rbio3.1 and rbio6.8 being effective. Overall, this analysis underscores the varying degrees of influence the NAO exerts on rainfall across different scales, emphasizing the importance of selecting appropriate wavelet families to capture these complex climatic interactions effectively.

The analysis of the cross-correlogram results using Coiflets, Discrete Meyer (Dmey), and Fejer–Korovkin (fk) wavelets reveals scale-dependent relationships between the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) and rainfall (

Figure 9). At short-term scales (D1–D3), correlations remain relatively weak, generally not exceeding ±0.20, suggesting minimal coherence. However, from the annual scale (D3–D4) onward, a gradual strengthening is observed. Notably, Coif4 and Dmey wavelets demonstrate a maximum positive correlation of 0.4 and a negative correlation nearing −0.39, indicating increased NAO influence. This trend continues at the intra-annual (D4–D5) and multiannual (D5–D6) scales, with Coif4 consistently showing moderate positive correlations (up to 0.39) and corresponding negative peaks. At the decadal scale (D6–D7), the strongest coupling emerges, with coif5 achieving the highest positive correlation (0.6) and fk8 registering the lowest negative correlation (−0.58), emphasizing the strong suitability of the coif wavelets for capturing long-term dynamics. In contrast, Dmey also provides positive correlation values across most scales, highlighting its more alternative in detecting NAO–rainfall coupling. Finally, at the trend scale (D7–A7), moderate but persistent interactions are recorded, with Coif5, fk6, and Dmey contributing correlations around ±0.45. Overall, Coif4, fk22, and to a lesser extent Dmey, emerge as informative mother wavelets, with Coif, Dmey, and fk families proving most effective in identifying the intricate temporal interplay between NAO and rainfall, particularly at the decadal and long-term scales.

Figure 10 illustrates the relationship between the NAO and Mostaganem SCM rainfall across multiple temporal scales, using the optimal wavelet from each family through cross-multiresolution wavelet analysis. The original series exhibits generally weak correlations, not exceeding ±0.20, suggesting limited direct interaction over the full time span. At short-term scales (D1–D3), correlations remain low (ranging from −0.25 to 0.25), with wavelets such as Db6, Sym10, Coif2, and rbior3.1 highlighting minimal coherence. However, correlations strengthen at the annual scale (D3–D4), with peaks around ±0.4, particularly captured by bior3.1 and Dmey, indicating a moderate influence of the NAO. Intra-annual variability (D4–D5) reveals even stronger coherence, with correlations nearing ±0.40 using wavelets like Db3, Coif4, and fk6. The highest correlations are observed at the multiannual scale (D5–D6), reaching up to 0.48 and −0.5, emphasizing the significant impact of NAO patterns, effectively revealed by bior3.3 and coif1. At the decadal scale (D6–D7), the relationship becomes most pronounced, with fk18 yielding correlations of 0.75 and −0.68, underscoring the dominant role of long-term NAO variability. Finally, long-term trends (D7–A7) maintain moderate-to-strong correlations (up to 0.677 and −0.59), with wavelets like bior3.1 capturing persistent interactions. Overall, the analysis highlights that the NAO influence on rainfall increases with scale, with cross-wavelet methods proving effective in uncovering these complex, scale-dependent climate dynamics.

The analysis of

Figure 11 reveals intricate interactions between the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) and rainfall across various timescales and geographic locations, specifically Mostaganem, Beni Yenni, and Timgad.

Table 4 highlights the optimal mother wavelets selected for different timescales, with bior3.1 consistently chosen across multiple scales for Mostaganem and Timgad, indicating its effectiveness in capturing nonlinear relationships in these humid regions. In contrast, Beni Yenni exhibits more variability in wavelet selection, such as bior3.7 and bior3.3 at longer timescales, suggesting a more complex interaction influenced by its transitional climate. As observed in

Figure 10, correlation values remain relatively weak at short-term scales (D1–D2 and D2–D3), ranging from −0.20 to 0.33, indicating limited coherence between NAO fluctuations and rainfall. However, as the timescale lengthens to the annual scale (D3–D4), maximum positive correlations increase to approximately 0.50 for Mostaganem and 0.39 for Beni Yenni, reflecting a stronger relationship likely driven by seasonal climatic patterns. The intra-annual scale (D4–D5) shows moderate but significant correlations, particularly in Mostaganem, while the multiannual scale (D5–D6) exhibits the most substantial correlations, with positive values reaching 0.53 and negative values around −0.58, underscoring the critical role of NAO fluctuations over several years. Notably, the decadal scale (D6–D7) showcases the strongest correlations, peaking at 0.75 for Mostaganem and 0.80 for Beni Yenni, highlighting the profound impact of long-term NAO trends on rainfall dynamics. Finally, moderate correlations persist at the long-term trend level (D7–A7), with values around 0.68 for Mostaganem, indicating that while relationships may stabilize over extended periods, they remain significant. This comprehensive analysis underscores the necessity of selecting appropriate wavelets and considering timescales when examining climatic interactions, providing valuable insights into how NAO dynamics influence regional hydrology and informing water resource management and climate adaptation strategies.

Table 6 provides a comprehensive overview of the most suitable wavelet families and corresponding mother wavelets for assessing nonlinear relationships between the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) and rainfall across the three rain gauge locations: Mostaganem, Beni Yenni, and Timgad. The table categorizes wavelets according to different decomposition levels, highlighting the diversity of wavelet choices necessary to capture complex interactions at each timescale. For short-term scales (D1–D2 and D2–D3), wavelets such as Db3, Coif3, and bior2.4 are employed, indicating a tailored approach to local climatic conditions. As the timescale extends to the annual scale (D3–D4), the selection shifts to more sophisticated wavelets like Db6 and Coif4, reflecting the need for robust analytical frameworks to understand evolving rainfall dynamics. Intra-annual variability (D4–D5) sees the continuation of this trend, with wavelets like Db3 and rbio2.4 capturing both periodic and trend components influenced by NAO. The multiannual scale (D5–D6) emphasizes wavelets such as Db4 and bior3.1, effective in modeling long-term relationships, while the decadal scale (D6–D7) showcases a diverse array of wavelets that can handle intricate climatic interactions. Finally, at the long-term trend level (D7–A7), wavelets like Db1 and Coif5 converge on forms capable of summarizing long-term climatic trends, underscoring the necessity of flexible analytical approaches. This nuanced understanding of wavelet efficacy enhances the ability to accurately model climatic phenomena, offering valuable insights into the impacts of NAO on regional rainfall patterns.

The selection of different optimal wavelet families across the three rain-gauge stations is partially consistent with the contrasting rainfall statistics summarized in

Table 2. At Beni Yenni, the highest mean and variance indicate a strong low-frequency modulation combined with large multiannual fluctuations; biorthogonal and high-order Daubechies wavelets, which balance sensitivity to both smooth and intermittent variations, therefore yielded the most coherent results. Mostaganem, showing the greatest skewness and kurtosis, experiences more irregular and extreme rainfall episodes typical of a coastal climate; asymmetric, compact-support wavelets such as Daubechies effectively localize these abrupt transients [

66,

67]. In contrast, Timgad exhibits lower variance and smoother temporal behavior, favoring more regular and near-symmetric wavelets (Symlets, Coiflets) that emphasize persistent low-frequency oscillations [

68].

Overall, these differences demonstrate that optimal wavelet selection is intrinsically signal-dependent: the mathematical features of each wavelet (symmetry, regularity, vanishing moments) align with the statistical texture of the rainfall record. Thus, while the general framework is transferable, the specific “best” wavelet should always be reassessed according to local rainfall variability and climatic regime.

4. Discussion

This study investigates the nonlinear relationships between the NAO and rainfall patterns in northern Algeria over the period 1970 to 2009 using a comprehensive wavelet analysis approach. The findings highlight substantial complexity in these interactions, underscoring the necessity of advanced analytical techniques to capture nonlinear dynamics that traditional methods may overlook.

The wavelet analysis reveals that, while scatter plot matrices indicate weak overall correlations between NAO and rainfall across the three stations, significant variations emerge across different temporal scales. The application of multiple wavelet families—including Daubechies, Biorthogonal, and Coiflets—allows a detailed assessment of the scale-dependent interactions. The results show that correlations strengthen at longer timescales, particularly at the annual and multiannual scales, where peak correlations reach up to 0.75 at the decadal level. This suggests that the influence of NAO on rainfall is more pronounced over extended periods, highlighting the importance of considering time dynamics in climatic studies.

The consistent selection of specific wavelets, such as bior3.1 for Mostaganem and Timgad, indicates their efficacy in capturing the underlying patterns of rainfall influenced by NAO. Conversely, the variability in wavelet selection for Beni Yenni suggests a more complex interplay, likely due to its transitional climate characteristics. This finding emphasizes the need for tailored analytical approaches that consider local climatic conditions and the unique hydrological responses of different regions.

Beyond the wavelet analysis, the cross-correlation results reveal intricate relationships between the NAO and rainfall that vary significantly across different scales. At short-term scales (D1–D3), correlations remain low, ranging from −0.25 to 0.25, indicating limited direct interaction. However, as the timescale extends to the annual scale (D3–D4), the peak correlation values rise to around ±0.4, particularly influenced by wavelets like bior3.1 and Dmey. This shift underscores that while short-term fluctuations may not strongly correlate with NAO, longer-term patterns reveal a more substantial relationship, suggesting that immediate climatic factors may mask these connections.

The intra-annual variability (D4–D5) shows even stronger coherence, with correlations nearing ±0.40 using wavelets such as Db3 and Coif4. This finding indicates that seasonal factors may play a crucial role in mediating the relationship between NAO and rainfall. The most substantial correlations observed at the multiannual scale (D5–D6), reaching up to 0.48 and −0.5, emphasize the significant impact of NAO patterns over several years, effectively revealed by bior3.3 and coif1. At the decadal scale (D6–D7), the relationship becomes most pronounced, with fk18 yielding correlations of 0.75 and −0.68, underscoring the dominant role of long-term NAO variability. Furthermore, the analysis of long-term trends (D7–A7) shows moderate-to-strong correlations (up to 0.677 and −0.59), indicating that while relationships may stabilize over extended periods, they remain significant. Using the cross wavelet transform (XWT), Zerouali et al. [

16] reported that the rainfall of the study area has had a significant relationship with the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) for approximately 1 year, 1–3 years, and 3–5 years beginning in the early 1980s, corresponding to the dry period. Bezerra et al. [

69] utilized the continuous wavelet method over the study period from 1968 to 2013, revealing three significant discontinuities in the wavelet spectrum corresponding to the decades of the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. The analysis identified various modes of variability across different stations, including annual (1 year), interannual (2, 2–4, and 4–8 years), and multidecadal (8–16 years) cycles. The identified coherence patterns emphasize the NAO’s considerable potential as a predictive indicator for seasonal and interannual precipitation variability. Recent research supports this finding. For example, Zerouali et al. [

70] showed that including the NAO as a predictor variable significantly improves the performance of artificial intelligence (AI) systems employed in rainfall modeling and gap filling, especially in northern Algeria. This consistency across multiple scales reinforces the notion that NAO dynamics play a critical role in shaping regional hydrology, influencing rainfall patterns and, consequently, water resource management strategies.

Importantly, the analysis indicates that components D1 and D2 contain significant noise elements that may obscure existing relationships between the NAO and rainfall. The presence of noise in these components can mask the true interactions, making it challenging to identify meaningful correlations. This noise-based variability influence may hide or reduce the correlations obtained using Pearson’s correlation in previous studies, particularly those conducted in Algeria [

23,

53,

54,

71,

72]. However, the present study demonstrates that applying DWT significantly enhances the accuracy of detecting hidden relationships compared with those observed in the original series. This finding emphasizes the effectiveness of wavelet analysis in isolating relevant signals from noise, thereby providing clearer insights into the NAO–rainfall dynamics. For example, several studies have applied DWT as a denoising approach prior to performing trend and change-point detection analyses, such as the Mann–Kendall, Pettit, and innovative trend detection methods, including their double and triple versions [

51,

52,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78]

The physical interpretability of the wavelet families is closely tied to their mathematical properties. Symmetric and biorthogonal wavelets (e.g., bior, rbior) are particularly effective in capturing quasi-periodic and recurrent oscillations because their symmetry preserves the phase information of both positive and negative fluctuations within the NAO signal. This makes them well suited for representing the nearly cyclic pressure anomalies associated with alternating positive and negative NAO phases. In contrast, asymmetric wavelets such as the Daubechies family (db) are designed to localize sharp transitions and discontinuities, enabling them to better characterize abrupt and intermittent rainfall variations typical of convective storms or short-lived wet episodes, in agreement with previous findings [

16,

42,

73,

75,

78,

79]. Wavelets with high vanishing moments, such as Coiflets and Symlets, emphasize smooth, long-term variations and are, therefore, advantageous for isolating low-frequency, decadal rainfall modulations driven by persistent NAO phases. These correspondences suggest that the apparent superiority of the bior and db families at different scales (as shown in

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9) reflects not only numerical performance but also a physical coherence between wavelet form and climate process dynamics.

It is important to clarify that the wavelet decomposition in this study was limited to seven levels, corresponding to a maximum temporal scale of 27 = 128 months (approximately 10.6 years). Therefore, the analysis encompasses intra-annual to decadal variability but does not extend into multidecadal regimes. This choice reflects the temporal resolution and length of the available rainfall and NAO series (~40 years), within which longer cycles (20–30 years) cannot be robustly resolved. The focus on sub-decadal and decadal bands ensures that the detected correlations are statistically meaningful and not artifacts of insufficient record length. Furthermore, the prominent coherence observed at high-frequency components (D1–D3) reflects the seasonal modulation of the NAO signal—particularly its well-known winter dominance—aggregated within the monthly rainfall variability.

The present analysis did not employ formal inferential tests such as the Mann–Whitney U or permutation procedures, because these tests assume data independence and are not directly appropriate for nonstationary and scale-overlapping wavelet coefficients. Instead, a robustness-based validation approach was adopted, emphasizing reproducibility, consistency, and physical plausibility. Correlation structures were interpreted as meaningful only when they persisted across multiple decomposition scales, remained consistent among different wavelet families, and corresponded to the dominant NAO periodicities documented in the climatological literature (e.g., 2–4 and 8–12 years). The distributional analysis presented in

Figure 4 further supports this robustness, showing coherent and nonrandom correlation patterns across scales. Collectively, this strategy ensures that the “hidden relationships” revealed by the cross-wavelet framework represent genuine teleconnection signals rather than random coincidences or noise-driven artifacts.

The use of different “optimal” wavelet families across stations reflects genuine hydroclimatic contrasts rather than methodological inconsistency. Each site exhibits distinct rainfall variability characteristics shaped by its geographic context—coastal (Mostaganem), mountainous (Beni Yenni), or continental highlands (Timgad)—leading to differences in spectral smoothness and dominant oscillation modes. Consequently, the wavelet family that best captures NAO–rainfall coupling at one site may not be equally effective at another. The performance of each wavelet was therefore evaluated in terms of its internal stability across scales and physical interpretability, rather than through statistical prediction on independent data periods. This approach ensures that the selected wavelets represent authentic regional responses to large-scale atmospheric forcing rather than artifacts of a single calibration period.

The identification of the most suitable wavelet families was not based solely on maximizing correlation values but on evaluating the stability, coherence, and reproducibility of correlation structures across scales and rainfall stations. Although high correlations were used as a diagnostic indicator, a wavelet was considered “optimal” only when the resulting time–frequency patterns were physically plausible and consistent with known NAO periodicities. In some cases, the wavelet producing the highest correlation was also retained, but only when this maximum value coincided with stable and climatically coherent patterns observed across neighboring scales. Thus, the analysis avoids circular reasoning: correlations were not treated as validation criteria in themselves, but as one component of a broader comparative framework aimed at identifying wavelets that most faithfully capture the underlying NAO–rainfall teleconnection dynamics.

In this study, more than 700 cross-correlations were computed for each NAO–rainfall pair, resulting from the application of 106 mother wavelets across seven decomposition levels (D1–A7). It is essential to emphasize that these correlations do not represent independent statistical tests but, rather, interrelated diagnostic measures derived from overlapping time–frequency components. Consequently, the classical problem of inflated Type I error associated with multiple independent comparisons (e.g., Bonferroni or FDR corrections) does not apply in this context. Each wavelet family shares common spectral content, and the decompositions are hierarchically nested within the multiresolution framework. Therefore, the objective was not to test statistical significance at each wavelet–scale combination, but to identify stable, physically coherent correlation structures that persist across scales, wavelet families, and geographic locations. Only relationships that were consistent and reproducible across multiple configurations were interpreted as meaningful, ensuring that the findings reflect robust NAO–rainfall couplings rather than random statistical artifacts.

Although the dataset covers the 1970–2009 period, excluding the most recent 15 years, this choice was motivated by data quality and availability. The study relies exclusively on in situ rainfall records from the National Agency of Hydraulic Resources (ANRH), which offer reliable and homogeneous long-term observations. Extending the analysis beyond 2009 would require integrating satellite-based datasets such as TRMM or PERSIANN, whose differing spatial and temporal resolutions could bias the multiresolution wavelet framework. Consequently, the present work focuses on identifying the intrinsic nonlinear teleconnections between NAO and rainfall based on consistent ground observations. Future research should expand this approach using recent satellite and reanalysis data to assess whether the identified NAO–rainfall coupling patterns persist under current climatic conditions.

Future research should focus on integrating additional climatic factors, such as local topography and land use changes, to explore how these variables interact with NAO influences. Additionally, examining the spatial variability of these relationships across broader geographic areas could provide deeper insights into regional climate dynamics. Understanding the mechanisms driving rainfall variability in northern Algeria may enhance predictive models and inform effective climate adaptation strategies. Overall, this study underscores the importance of employing advanced wavelet analysis to unravel the complexities of climatic interactions, offering valuable contributions to the fields of hydrology and climate science.

5. Conclusions and Future Recommendations

This study successfully highlights the nonlinear relationships between the NAO and rainfall patterns in northern Algeria from 1970 to 2009, employing a comprehensive wavelet analysis utilizing various wavelet families. By assessing seven distinct wavelet families—Daubechies, Biorthogonal, Reverse Biorthogonal, Discrete Meyer, Symlets, Coiflets, and Fejer–Korovkin—the analysis reveals complex interactions that traditional linear methods may overlook. Notably, at short-term scales (D1–D3), correlations remain low, ranging from −0.25 to 0.25, with wavelets such as Db6, Sym10, Coif2, and rbior3.1 showing minimal coherence. However, correlations strengthen at the annual scale (D3–D4), peaking around ±0.4, particularly captured by bior3.1 and Dmey, indicating a moderate influence of the NAO. Intra-annual variability (D4–D5) reveals even stronger coherence, with correlations nearing ±0.40 using wavelets like Db3, Coif4, and fk6. The most substantial correlations are observed at the multiannual scale (D5–D6), reaching up to 0.48 and −0.5, emphasizing the significant impact of NAO patterns, effectively revealed by bior3.3 and coif1. At the decadal scale (D6–D7), the relationship becomes most pronounced, with fk18 yielding correlations of 0.75 and −0.68, underscoring the dominant role of long-term NAO variability. Finally, long-term trends (D7–A7) maintain moderate-to-strong correlations (up to 0.677 and −0.59), with wavelets like bior3.1 capturing persistent interactions. Overall, this research underscores the importance of considering temporal dynamics and employing sophisticated analytical techniques in climatic studies to better understand regional hydrology.

Although this study focused primarily on the nonlinear relationships between the NAO and rainfall, it is important to note that temperature variations, topography, and vegetation also influence the regional hydrological regime. Higher temperatures can intensify evapotranspiration and alter soil moisture dynamics, while the mountainous relief of northern Algeria and the spatial variability of vegetation cover contribute to marked differences in rainfall distribution. These factors should be further explored in future studies to better contextualize the large-scale atmospheric effects identified in this work.

Future studies should aim to integrate additional climatic and environmental variables—such as local topography, land use transformations, and atmospheric dynamics—to better understand their combined influence on the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO). Examining the spatial heterogeneity of these interactions across broader geographic scales would yield a more nuanced understanding of regional climate behavior. A deeper comprehension of the processes governing rainfall variability in northern Algeria could enhance predictive models and support the development of effective climate adaptation and water management strategies. This study highlights the value of advanced wavelet-based approaches for disentangling complex climatic relationships, thereby contributing significantly to hydrology and climate science.

Further research should also explore the comparative performance of different wavelet families and mother wavelets in characterizing NAO–rainfall linkages. Testing diverse wavelet types may uncover new perspectives on multiscale climatic variability. Incorporating additional predictors—such as land use change, topographic variation, and atmospheric circulation parameters—would enable a more comprehensive representation of these relationships. Expanding the analysis to include multiple climatic zones could help determine how regional variations influence the applicability and accuracy of various wavelet frameworks.

Combining wavelet analysis with machine learning methods offers promising potential for enhancing predictive performance. Algorithms such as neural networks and ensemble models could be trained on wavelet-derived features to improve forecasts of rainfall responses to NAO variability. Continued investigation into ocean–atmosphere interactions and regional climate mechanisms will be vital for advancing predictive understanding and guiding climate adaptation policies. Overall, this integrative approach can refine our knowledge of hydroclimatic dynamics and support the design of targeted strategies to mitigate climate-related impacts on water resources in northern Algeria and comparable semi-arid regions.