Abstract

Thermokarst lakes play a crucial role in regulating hydrological, ecological, and biogeochemical processes in permafrost regions. However, due to the limited spatial resolution of earlier satellite imagery, small thermokarst lakes—highly sensitive to climate change and permafrost degradation—have often been overlooked, hindering accurate spatiotemporal analyses. To address this limitation, five water indices—Modified Normalized Difference Water Index (MNDWI), Multi-Band Water Index (MBWI), Automated Water Extraction Index (AWEIsh and AWEInsh), and Red Edge Water Index (RWI)—were employed based on Sentinel-2 imagery from 2021 to extract thermokarst lakes in the Qinghai–Tibet Highway (QTH) region, China. Visual validation indicated that the Red Edge Water Index (RWI) yielded the best performance, with an error of only 10.21%, significantly lower than other indices (e.g., MNDWI: 41.36%; MBWI: 38.80%). Seasonal comparisons revealed that the applicability of different water indices varies, with autumn months (September to October) being the optimal period for lake extraction due to stable and unfrozen surface conditions. Using the RWI, 56 thermokarst lake drainage events were identified in the study area from 2016 to 2025 (as of September 2025), most occurring after 2019—likely associated with climatic factors—and small lakes were found to be more prone to drainage, accompanied by notable surface subsidence in drained regions. These findings are applicable across the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau (QTP) and provide a scientific basis for monitoring thermokarst lakes, delineating accurate lake boundaries, and exploring drainage mechanisms.

1. Introduction

The Qinghai–Tibet Plateau (QTP) is the world’s highest and largest plateau, characterized by extensive permafrost, lakes, rivers, and glaciers. The plateau hosts 32,843 lakes (all lake types included), covering a total surface area of 43,151 km2, glaciers occupying a total area of approximately 43,087 km2, and an extensive permafrost region covering an area of approximately 1.06 × 106 km2 [1,2,3]. A prominent warming trend has been observed on the QTP, where warming is notably more intense compared to the global average. Such a trend directly contributes to the thawing of permafrost [4,5]. Climate warming-induced increases in precipitation and the melting of glaciers and permafrost have resulted in significant changes in the water balance on the QTP. Notably, the lake count, lake area, water level (surface elevation), and water volume have increased by 344, 10 × 105 ha, 4 m, and 1.7 × 1011 tons, respectively, over the period from 1976 to 2018. Furthermore, global warming has accelerated the thawing of permafrost, leading to the emergence of thermokarst landforms, which are widespread across the permafrost region of the QTP and exert notable impacts on local hydrology and ecology [6].

Thermokarst lakes are prominent thermokarst landforms and are widely distributed in the Arctic and the QTP [7,8]. These lakes are typically smaller than tectonic lakes (which are formed by large-scale crustal movements, such as faulting), with surface areas usually less than 50 ha [9]. The total surface area of thermokarst lakes in the Northern Hemisphere exceeds 2.3 × 108 ha, accounting for 10% of the permafrost area in this hemisphere. Among these, there are 643,304 lakes larger than 1 ha, with a total area of 11,818,200 ha [10]. On the QTP, the permafrost region contains about 161,300 thermokarst lakes, covering a total area of 2825.45 km2 [11]. Permafrost thaw driven by rapid warming has accelerated the development of thermokarst lakes, with small-sized lakes showing higher sensitivity to temperature variations. From 1969 to 2010, the number of small thermokarst lakes (0.1–0.8 ha) in the Beilu River Basin increased by 365%, and their total area grew by 60%. In contrast, large thermokarst lakes (>2 ha) increased in number and area by only 48% and 12.9%, respectively [12]. This marked disparity underscores the importance of adopting detection methods with higher recognition capacity for small lakes in thermokarst lake monitoring. Nevertheless, recent research indicates that with intensified permafrost degradation, a decreasing trend in thermokarst lake area has appeared in both northern Alaska and the QTP [13]. This contradicts the conventional view that thermokarst lakes continuously expand due to ground-ice melting under global warming [14]. It suggests that, in some regions severely affected by permafrost degradation, the area exposed by thermokarst lake drainage exceeds that gained through glacial ablation [15]. Moreover, the exposed lakebeds become “new habitats” for vegetation, where pioneer species colonize and grow, altering the balance between permafrost carbon release and vegetation carbon sequestration. Notably, the QTP permafrost region stores 12.4–25.6 billion tonnes of organic carbon in the top 2 m of soil, and thermokarst lake drainage has been shown to halve the temperature sensitivity (Q10) of CH4 release from surface sediments—a reduction of approximately 56%. This response is primarily driven by changes in microbial communities (49.3%) and substrate availability (30.3%) [16]. Hence, thermokarst lakes serve not only as indicators of geomorphic evolution but also as key elements for accurate assessment of permafrost carbon dynamics and climate feedbacks. As a major engineering corridor, the QTH is influenced by both climate warming and human activities, leading to substantial permafrost degradation along its route [17]. Therefore, precise identification and dynamic monitoring of thermokarst lakes in this region, along with systematic investigation of drainage events, are essential for understanding permafrost degradation processes and their eco-environmental impacts.

With the continuous advancement of satellite technology and the proliferation of remote sensing datasets, methods for extracting surface water have become increasingly diverse. Commonly used techniques include the single-band method, inter-spectral relationship method, image classification method, and the water body index method, with the water body index method being widely utilized [18]. The Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) is typically applied for detecting large lakes but is less effective in urban areas [19]. The Modified Normalized Difference Water Index (MNDWI) is based on the NDWI, but it uses the Landsat TM short-wave infrared band (TM5) instead of the near-infrared band (TM4). This modification effectively minimizes the influence of soil and buildings, and the MNDWI is thus commonly used for detecting urban water bodies [20]. The Automated Water Extraction Index (AWEI) is a method based on TM image data and is designed to maximize the differentiation between water bodies and non-water bodies by operating between bands and assigning different coefficients to the bands. The AWEI has been shown to exhibit a higher separation accuracy than the MNDWI [4]. The water index 2006 employs the natural logarithm of each band in Landsat 7 ETM+ imagery to represent reflection coefficients and interaction conditions, and it has been used for wetland extraction in eastern Australia [21]. The Multi-Band Water Index (MBWI) effectively mitigates the effects of mountain shadows, dark image elements of buildings, and seasonal effects caused by changing solar conditions [22]. The Vegetation Red Edge-based Water Index (RWI) algorithm performs well in eliminating the effects of mountain and building shadows, cloud shadows, and mixed image elements, and it possesses a high degree of boundary differentiation for small water bodies [23]. Previous studies have also explored water extraction algorithms based on Sentinel-2. Yang et al. used MNDWI and AWEI for urban water detection using Sentinel-2 images, applying the Constrained Energy Minimization target detection algorithm to eliminate noise and enhance water extraction accuracy [24]. Wang et al. used four water indices, namely NDWI, MNDWI, AWEI, and Water Index 2015 (WI2015), for water identification in Poyang Lake using Sentinel-2 and Landsat 8 OLI data [25]. They compared the extraction results with visual interpretation results and found that AWEI and WI achieved the highest accuracy. Du et al. processed Sentinel-2 images using the panchromatic sharpening method, utilizing NDWI and MNDWI for water identification along the Venice coast [26]. Their results indicated that the 10 m NDWI produced more accurate water maps than the 20 m MNDWI.

Most previous studies of thermokarst lakes on the QTP typically use low and medium-resolution satellite data, such as Landsat and MODIS (Moderate-resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) data [5,27]. A main limitation of this approach is the difficulty in extracting small lakes, which results in an underestimation of both the number and area of these smaller water bodies. Although some studies have used high-resolution satellite imagery for the extraction of small thermokarst lakes, their extent has been limited to localized areas. For instance, Zhang et al. identified lakes larger than 0.1 ha on the QTP, overlooking smaller thermokarst lakes [1]. Luo et al. used SPOT imagery to produce a map of a single thermokarst lake (>0.1 ha) covering 251,360 ha [27]. Presently, most studies employing water indices focus on medium and large water bodies, with limited attention given to the extraction of small water bodies. Due to the spatial resolution of the images, small thermokarst lakes have a higher ratio of mixed pixels at their edges to pure lake pixels than medium-large lakes. This results in a larger error in calculating the mean relative area of small lakes when compared to medium-large lakes. Wei et al. extracted and analyzed all thermokarst lakes on the QTP and found that thermokarst lakes with areas ≤1 ha exhibited the largest error in mean relative area (35.1%) [28], whereas those with areas ≥10 ha exhibited the smallest error (4.4%). Small thermokarst lakes are more susceptible to temperature changes than their larger counterparts. Therefore, accurately determining the number and area of small thermokarst lakes is crucial for understanding global water resources and carbon emissions. Furthermore, most existing research has emphasized the expansion processes, driving mechanisms, and thermal effects of thermokarst lakes on surrounding permafrost [12,29], whereas limited attention has been given to the scale and spatiotemporal features of their shrinkage–drainage phenomena. Nitze et al. employed Sentinel-1 Synthetic Aperture Radar and Planet CubeSat optical remote-sensing data to analyze recently observed widespread lake drainage and reported that 192 fully or partially drained lakes occurred in northwestern Alaska between 2017 and 2018 [30]. Chen et al., using the Google Earth Engine platform and the LandTrendr algorithm [31], monitored thermokarst lake drainage events in northern Alaska since 2000 and identified 90 drained lakes, about 30% of which were completely drained. However, such studies remain largely confined to the circum-Arctic region, leaving a research gap for the QTP.

To overcome these limitations, this study detected thermokarst lakes larger than 0.05 ha along the QTH using Sentinel-2 imagery. The main objectives are as follows: (1) Compare and evaluate the accuracy of multiple water indices for detecting small lakes to determine the optimal method for small-water-body extraction on the QTP; (2) Assess the performance of the optimal index across different seasons; (3) Analyze the spatiotemporal variation trends of thermokarst lakes using the selected method; (4) Identify and screen drained lakes that meet specific criteria. The results provide a reliable methodological framework for high-precision remote-sensing monitoring of small thermokarst lakes on the QTP, with significant implications for understanding permafrost degradation, evaluating engineering safety along the QTH, and issuing early warnings of thermokarst-related geohazards.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The study targeted the Golmud-Lhasa section of the QTH (Figure 1). The study area consists of a 5000 m region on both sides of the QTH, situated at elevations ranging from 3953 m to 6191 m. The QTH starts from Golmud and ends at Lhasa, with a total length of 1142 km [32]. The study area features a variety of landscapes, including alpine meadows, alpine deserts, alpine grasslands, glaciers, and lakes. Permafrost in this region is highly sensitive and susceptible to climatic variations. The annual average ground temperature along the QTH has increased by 0.12–0.67 °C at a depth of 6 m from 1995 through 2005, and half of the permafrost temperatures exceed −1 °C [33,34]. The average active layer thickness was approximately 2.41 m, ranging from 1.32 m to 4.57 m between 1995 and 2007 [35]. The highest temperatures in the region occur in July and the lowest in January or December. The freezing period persists for 7–8 months. The combined effect of abundant sunshine, sparse cloud cover, and turbulent winds cause the average annual evaporation to be approximately 6–8 times greater than the average annual precipitation. Most parts of the study area receive an annual precipitation of 300 mm, with the rainy season spanning from May to September and the dry season from October to April.

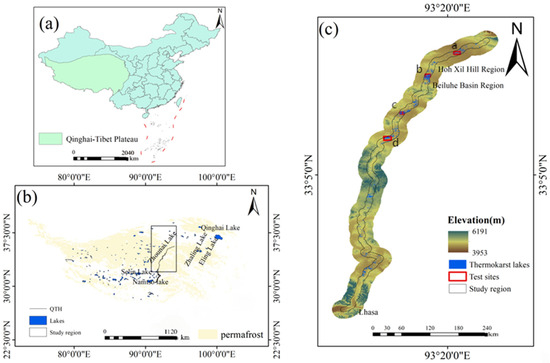

Figure 1.

(a) Map of China, (b) QTP, and (c) Study region and sub-region.

To evaluate the accuracy of the water extraction methods, four representative sub-regions (labeled a, b, c, and d in Figure 1c) were selected along the Qinghai–Tibet Highway. These sub-regions cover a range of elevations and lake sizes: Area a (average elevation 4502 m) is dominated by small thermokarst lakes; Area b (4564 m) contains medium-sized lakes; Area c (4566 m) also features predominantly small lakes; and Area d (4640 m) includes both small and medium-sized lakes. The selection of these areas was designed to incorporate diversity in both lake size and spatial distribution, thereby enabling a comprehensive assessment of the performance of different water indices across varying lake conditions.

2.2. Data Source

2.2.1. Satellite Images

A total of 156 Sentinel-2 satellite remote-sensing images from 2016 to 2025 (as of September 2025) were utilized for extracting drained lakes. The Sentinel-2 series is specifically designed for monitoring surface changes and provides much higher spatial resolution (up to 10 m) than earlier missions such as SPOT and Landsat. Image selection focused on the September–October period, when water bodies remain relatively stable [1]. The chosen images meet the criteria of cloud coverage < 5%, cloud shadow < 3%, and dark feature coverage < 2%. Additionally, imagery from May 2022, July–August 2022, September–October 2021, and January 2023 was used for seasonal analysis. The selected Sentinel-2 MSL2A dataset in this paper has undergone geometric and radiometric corrections, requiring no additional processing steps. All data products are freely available from the Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem (https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/, accessed on 1 October 2025).

For Small Baseline Subset Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (SBAS-InSAR) deformation monitoring, a total of 224 Sentinel-1A C-band Single Look Complex images were employed. All images, covering the period from June 2018 to June 2023 to guarantee temporal continuity, were acquired in the Interferometric Wide (IW) swath mode with an approximate spatial resolution of 5 × 20 m (range × azimuth). These data are accessible through the European Space Agency (https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/, accessed on 1 October 2025).

2.2.2. Other Datasets

In this study, SRTM-1 DEM data with a spatial resolution of 30 m were used to remove the topographic phase, providing high-accuracy elevation information. To ensure its accuracy for this purpose, we verified that there were no significant data voids over our study area and resampled it to match the coordinate system and resolution of the SAR data. The dataset can be obtained from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (http://www.nasa.gov/, accessed on 1 October 2025).

Given that the observed thermokarst lake drainage events are primarily concentrated in the Wudaoliang area, the Wudaoliang meteorological station was selected as the most representative data source for analyzing regional climate drivers. Accordingly, air temperature and rainfall data from this station, covering the study period from 2016 to 2024, were retrieved from the National Centers for Environmental Information under the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration of the United States (https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/search/data-search/, accessed on 1 October 2025).

2.3. Methods for Thermokarst Lake Extraction

2.3.1. Visual Interpretation

Visual interpretation serves as the core manual refinement method for obtaining the most accurate information on thermokarst lakes. This approach involves the comprehensive analysis of spectral and spatial characteristics from Sentinel-2A imagery, utilizing techniques such as direct identification, comparative analysis, and interdisciplinary logical reasoning. It enables meticulous verification of automatically extracted results, precise boundary correction, and effective exclusion of non-target water bodies like rivers and glaciers. Although time-consuming, this process effectively mitigates interference from complex plateau environments—such as clouds, snow, shadows, and interconnected water bodies—on automated identification. It is regarded as the most accurate and reliable technical solution currently available for ensuring high-precision extraction of thermokarst lakes.

2.3.2. Spectral Water Indices

MNDWI an improved water body index introduced by Xu. based on NDWI [20], possesses the capability to reduce the influence of soil and buildings, and demonstrates good performance in the removal of building shadows in urban areas. It is expressed as Equation (1):

MBWI, proposed by Wang et al. [22], is capable of attenuating the effects of mountain shadows, dark image elements of buildings, and seasonal effects arising from changing solar conditions. It is expressed as Equation (2):

AWEI introduced by Feyisa et al. is capable of maintaining consistent water detection accuracy in the presence of various environmental noises [36], while providing stable thresholds that improve classification accuracy for regions including shaded and dark surfaces. It is expressed as Equations (3) and (4):

Vegetation RWI, proposed by Wu et al. [23], can effectively eliminate the effect of mixed image elements at the boundaries of water bodies as well as within water bodies to some extent. It provides superior detection of water body boundaries, particularly in small lakes. The formula is expressed as Equation (5):

In Equations (1)–(5), each band corresponds to a different spectral band of the Sentinel-2 imagery, specifically: Band 2 (Blue, 0.490 μm), Band 3 (Green, 0.560 μm), Band 4 (Red, 0.665 μm), Band 5 (Red Edge 1, 0.705 μm), Band 8 (Near Infrared, 0.842 μm), Band 8A (Red Edge 3, 0.865 μm), Band 11 (Short-Wave Infrared 1, 1.610 μm), and Band 12 (Short-Wave Infrared 2, 2.190 μm). These indices, formulated as band ratios or combinations, incorporate normalization to mitigate the influence of background values to a certain extent.

To convert continuous water index values into binary classification results of water and non-water, this study established optimized thresholds for each index: the thresholds for MNDWI, AWEIsh, and RWI were set at 0.05, 0.10, and 0.017, respectively, to effectively suppress background noise while preserving genuine water bodies; whereas the thresholds for MBWI and AWEInsh were set at −0.02 and −0.024, respectively, to better adapt to their respective index response ranges. All thresholds were determined by analyzing the index distribution of validation samples combined with visual interpretation results, aiming to maximize classification accuracy. Following initial extraction based on the above thresholds, morphological opening and closing operations were further applied to remove small-area noise and fill holes, thereby obtaining the final water boundary map.

The thermokarst lakes identified through visual interpretation and spectral indices were subsequently classified by their surface area into three distinct size categories, namely small (0.05–1 ha), medium (1–10 ha), and large (10–300 ha).

2.4. Validation and Accuracy Assessment

In order to quantitatively analyze the accuracy of several water extraction methods, the following error analysis equations were used, as shown in Equation (6):

where represents the error result (%), t0 is the area obtained by the visual manual interpretation (ha), ti is the area obtained by the water index (ha).

To quantitatively evaluate the performance of the water extraction methods, a validation set consisting of 683 polygons (395 water bodies and 288 non-water bodies), all smaller than 300 ha in area, was established through meticulous visual interpretation of high-resolution Sentinel-2 imagery. Subsequently, we separately selected 513 thermokarst lakes smaller than 1 ha (including 310 water bodies and 203 non-water bodies) specifically for accuracy validation targeting small thermokarst lakes. This manual delineation served as the reference data (ground truth) for accuracy assessment [37].

The accuracy of each water index was rigorously evaluated using a suite of standard metrics derived from the error matrix (or confusion matrix), which is a cornerstone for assessing the performance of thematic map classifications [38].

To assess accuracy, we employed Producer Accuracy (PA) [38], User Accuracy (UA), Overall Accuracy (OA) [39], and the Kappa coefficient [40,41]. PA refers to the proportion of reference samples correctly identified, which is used to measure classification errors. OA indicates the proportion of randomly selected samples from the image that are accurately classified, while the Kappa coefficient is commonly used to describe the level of agreement between the classification results and the reference dataset. The accuracy of the classification results for each sub-study area was assessed based on the confusion matrix and its derived metrics including omission and misclassification error, OA and Kappa coefficient. OA, PA and UA were generated by the following Equations (7)–(9):

where OA is the Overall Accuracy (%); PA is the Producer’s Accuracy (%); UA is the User’s Accuracy, unit is percent (%); P represents true positives (corresponding to the water surface), N represents true negatives (representing other land cover types), TP denotes true positive instances, TN denotes true negative instances, FP is the number of false positive pixels, and FN stands for false negative instances [38].

The Kappa coefficient (K) was calculated using Equation (10):

where Pii denotes the relative observed agreement for class i (i.e., the proportion of instances where the classification and reference data agree on class i), pi+ denotes the proportion of instances assigned to class i by the classification map, p+i denotes the proportion of instances that truly belong to class i in the reference data, and n is the total number of classes. A higher Kappa value indicates a stronger agreement beyond chance, with the value typically ranging between 0 and 1.

This multi-faceted validation approach, employing both an error matrix and direct areal comparison, is well-established in remote sensing water body mapping and ensures a comprehensive evaluation of the indices’ performance concerning both categorical accuracy and geometric fidelity [25,37].

2.5. Thermokarst Lake Drainage Monitoring

This study employed a dynamic annual sliding benchmark analysis method to systematically identify significant thermokarst lake drainage events during the study period. The screening criterion followed the definition proposed by Chen et al. [15]: a thermokarst lake with an initial area greater than 1 ha and a subsequent drainage ratio of at least 50% was classified as a drained lake. The core of this method is to sequentially set each year in the time series (denoted as year t, where t ∈ {t0, t1, …, tn}) as the benchmark year. For each benchmark year t, all thermokarst lakes with an area larger than 1 ha were extracted to form the candidate lake set Lt. Subsequently, for each lake i in the set L, its Drainage Ratio (DR) in the subsequent year (where ≥ 1), and its calculation formula is defined as Equation (11):

where is the Drainage Ratio of lake in year relative to benchmark year (%); is the area of lake in the benchmark year (ha); is the area of lake in the subsequent year (ha).

By traversing all possible combinations of t and instances satisfying the condition in Equation (12) are finally selected:

For lakes experiencing multiple area fluctuations during the study period, this method records only the first occurrence that meets the drainage criterion (DR ≥ 50%) to prevent duplicate counting of individual lakes. A 50% area loss threshold is a relatively strict criterion. If a lower threshold were adopted, it might misclassify non-substantive drainage (such as temporary water level decline) as lake drainage events. This approach avoids missed detections caused by fixing a single benchmark year and, through full-period scanning, greatly enhances the comprehensiveness and accuracy of event identification.

2.6. SBAS-InSAR

To examine the relationship between surface deformation and thermokarst lake drainage, the SBAS-InSAR technique was used for data processing and analysis. This method effectively mitigates errors resulting from temporal-spatial decorrelation and atmospheric phase delays common in conventional D-InSAR by combining SAR image pairs with short spatiotemporal baselines, enabling high-precision, long-term monitoring of gradual surface deformation.

The processing was conducted using the SARscape module in ENVI 5.6.2 software. The processing workflow included: acquiring N + 1 Sentinel-1A images, selecting a master image, and co-registering slave images. Interferometric pairs were formed using spatiotemporal baseline thresholds, with a maximum temporal baseline of 90 days and a maximum spatial baseline of 120 m. Differential interferograms were generated after removing topographic phases using SRTM DEM data. Phase noise was reduced via Goldstein filtering, and phase unwrapping was performed using the Minimum Cost Flow algorithm. The deformation time series was derived through Singular Value Decomposition, and atmospheric or orbital errors were mitigated via spatiotemporal filtering. The final outputs—an average annual deformation velocity map and deformation time series—provided quantitative data for analyzing surface responses to thermokarst lake drainage.

3. Results

3.1. Accuracy Assessment of Water Body Classification

In this study, the Kappa coefficient, OA, PA, and UA of five water indices were calculated (Table 1). The results indicated that RWI exhibited the highest Kappa coefficient and OA values of 0.86 and 93.50%, respectively. Additionally, RWI demonstrated relatively high PA and UA values (both > 85%). Although MBWI had the highest UA value of 100%, its Kappa coefficient, OA, and PA values were the lowest among the five water indices. AWEIsh and MNDWI exhibited high Kappa coefficients (0.83 and 0.85, respectively) and OA (91.71% and 92.80%, respectively), along with good PA (>80%) and UA values (>90%). Similar to MBWI, AWEIsh had high UA values, but its Kappa coefficient, OA, and PA values were lower than those of AWEIsh, MNDWI, and RWI.

Table 1.

Kappa coefficients, OA, PA, and UA for five water body indices, along with the total number and area of water bodies extracted by each index.

RWI detected 3954 thermokarst lakes with a total area of 7668.59 ha (Table 1). Thermokarst lakes were primarily distributed in the central and northern parts of the study region, with significant variations among different permafrost. RWI detected a large number of thermokarst lakes in the continuous permafrost region, and a small number of lakes were distributed in the island and sporadic permafrost region. According to statistics, as the size of the thermokarst lakes increased, the number of lakes gradually decreased. Among them, small lakes account for 81.44% of the total number of lakes, but their area only makes up approximately 11.79% of the total lake area. Large thermokarst lakes, on the other hand, represent 1.75% of the total number of lakes, yet account for about 29.52% of the total lake area. Evidently, small thermokarst lakes were the major contributors to the total number of lakes identified, whereas large thermokarst lakes were the major contributors to the total area occupied by the lakes. Therefore, we conducted a specific accuracy evaluation focusing on small thermokarst lakes. The results confirm that the RWI method achieved superior performance with higher Kappa coefficient, OA, PA, and UA values compared to other water indices (Table 2).

Table 2.

Number and area of water bodies extracted by different indices and visual interpretation in the four test regions.

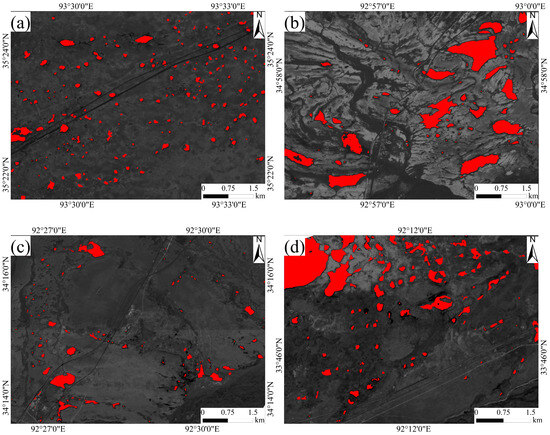

To quantitatively assess the accuracy of the fine water extraction, four areas (a–d) within the study region were designated as text sites for accuracy assessment (Figure 2). Subsequently, the accuracies of the extracted results were assessed against this benchmark. The total areas of water bodies derived from visual interpretation in these four areas (a, b, c, and d) were 71.94 ha, 400.04 ha, 82.34 ha, and 481.79 ha, respectively. In the four study areas, the disparity in the number and area of lakes obtained through RWI and AWEIsh was low and was in good agreement with the results of visual interpretation (Figure 2 and Table 2). RWI yielded 391 lakes occupying 1141.89 ha, differing from visual interpretation by 10.73% and 10.21%, respectively. AWEIsh yielded 399 lakes occupying 905.56 ha. In regions a, b, and c, the number of lakes obtained by RWI was close to that obtained by visual interpretation. However, in region d, the number of lakes extracted by AWEIsh was far greater than that extracted by RWI and was close to that obtained by visual interpretation. In region a, which was dominated by small lakes, small differences were observed between the lake areas obtained by AWEIsh and those obtained by RWI and the true value. The difference between the lake areas obtained by AWEIsh and RWI was 2.97 ha (4.13%), and the difference between the lake areas obtained by AWEIsh and the true value was 3.56 ha (4.95%). In region b, which had numerous medium-sized lakes with a total area of 400.04 ha, AWEIsh and RWI displayed the smallest differences from the true value: −41.67 ha (11.08%) and 35.53 ha (9.57%), respectively. In region c, which was similar to region a, small lakes predominated. RWI exhibited the smallest difference in lake area from the true value: 6.61 ha (8.03%), whereas the other four spectral water indices yielded results greater than 35%, with a maximum of 65.80%. In region d, which was characterized by small and medium-sized lakes with a true area of 481.79 ha, AWEIsh and RWI yielded the smallest deviation from the true value: −53.93 ha (11.19%) and 64.43 ha (13.37%), respectively.

Figure 2.

Results of visual interpretation in four regions. (a) region a, (b) region b, (c) region c, and (d) region d.

Despite the Kappa coefficient of the MNDWI reaching 0.85 (Table 1), there are still certain limitations in the identification of lake boundaries. When dealing with images that combine water bodies and aquatic vegetation, this index may incorrectly identify the entire area as a water body, thereby leading to an overestimation of the lake area. In regions a, c, and d, the areas of lakes extracted by MNDWI exceeded the true value by 50%. In contrast, the Kappa coefficient, OA, and PA values of MBWI and AWEInsh were smaller than those of the other water indices. MBWI exhibited the smallest Kappa coefficient among the five spectral water indices, resulting in smaller lake areas compared to the true values. AWEInsh yielded lake results that were smaller than the true values in four regions, with a maximum difference of 48.14%. The differences between the true lake values and the results of AWEIsh were smaller in regions a, b, and d than they were in region c, where the difference reached 35.61%. This suggests that while AWEIsh is generally applicable to most regions of the QTP, there may be a considerable error in a small portion of the region. Conversely, RWI lake detection results for the four regions deviated from the true values by less than 15%, with a minimum difference of 4.95%. Hence, RWI demonstrates high accuracy in delineating lake boundaries.

3.2. Influence of Seasonal Conditions on Surface Water Extraction

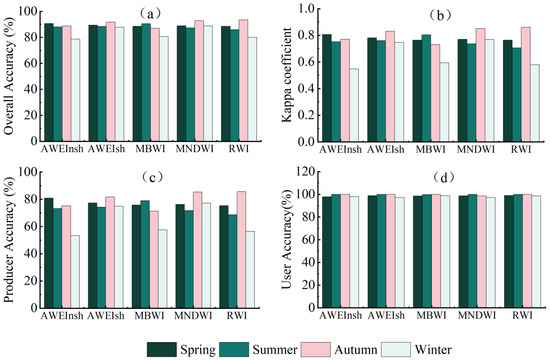

Seasonal conditions were a major factor negatively influencing lake extraction. Following the standard definition for the Northern Hemisphere, spring spans from March to May, summer extends from June to August, autumn extends from September to November, and winter spans from December to February. Variations in precision were observed among the five water indices across different seasons (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Four precision measurements of five water indices in different seasons (a) OA, (b) Kappa coefficient, (c) PA, and (d) UA.

In spring, AWEInsh exhibited superior performance, surpassing the other four water body indices in OA, Kappa coefficient, and PA, with values of 90.56%, 0.81, and 80.87%, respectively. In summer, MBWI demonstrated significantly higher water accuracy compared to the other indices, achieving OA, Kappa coefficient, and PA values of 90.46%, 0.8035, and 78.96%, respectively. In autumn, when thermokarst lakes along the QTH were completely melted, and the boundaries between lake and non-lake surfaces were distinct, RWI outperformed the other indices, yielding the highest values for OA, Kappa coefficient, and PA at 93.50%, 0.86, and 85.61%, respectively. However, in winter the thermokarst lakes froze with snow and ice cover, rendering the boundary between lakes and non-lakes difficult to distinguish. During this season, AWEInsh, MBWI, and RWI only achieved Kappa coefficient and PA values of 0.5 and 50%. MNDWI, however, yielded the best results, with OA, Kappa coefficient, and PA values of 88.74%, 0.77, and 77.12%, respectively. In different seasons, the accuracy of various water body indices varies. The AWEInsh index is suitable for spring, the MBWI is recommended for summer, the RWI is optimal for autumn, and the MNDWI performs most accurately in winter. The reason for this selection is that the reflective characteristics of water bodies and the surrounding ground differ across seasons, and these differences affect the extraction accuracy of each water body index in different seasons.

The QTP has a wide range of climatic and environmental conditions. Different watersheds on the QTP showed differences in lake area changes owing to the different drivers of changes in the area of each lake. Furthermore, different lakes can exhibit varied behavior under similar environmental conditions. Consequently, the optimal period for assessing inter-annual changes in lake area falls between September and November [41]. Hence, RWI, which possesses the highest accuracy, is often used in the fall for lake detection on the QTP.

3.3. A Comparative Examination of Research Outcomes

To further validate the accuracy and regional applicability of the RWI method, a generalization experiment was designed based on the work of Șerban et al. (Table 3). For a strict controlled variable comparison, the study area was selected as the same region investigated by Șerban et al.—the Chalaping area in the source area of the Yellow River, northeastern part of the QTP (34°13′ N, 97°48′ E, covering approximately 150 km2). This approach ensures an objective evaluation of the accuracy and adaptability of the RWI method under consistent geographical and data conditions.

Table 3.

Number and area of lakes obtained from RWI and MLC in Chalaping at the Sources Area of the Yellow River region.

Based on Sentinel-2 satellite imagery acquired during the same period (23 November 2015), this study employed visual interpretation as the benchmark (identifying 740 lakes with an area ≥ 0.04 ha and a total area of 386.33 ha) and compared the RWI against the Maximum Likelihood Classification (MLC) method used by Șerban et al. Șerban et al. had systematically evaluated multiple water extraction methods in this region, including spectral water indices, unsupervised classification (k-means clustering), supervised classification (density slicing, MLC), and machine learning algorithms (Random Forest, Support Vector Machines). They ultimately determined that the MLC method applied to visible and near-infrared bands delivered the best overall performance, extracting 966 thermokarst lakes with a total area of approximately 470 ha. However, the results based on MLC significantly overestimated both the number and area of lakes, with error rates reaching 30% and 22%, respectively. According to Șerban et al., MLC tends to overestimate the number and area of thermokarst lakes in detection. This could be attributed to the specific assumptions MLC makes about the statistical properties of the data; when these assumptions are not met, classification errors may occur. For example, MLC assumes that the data follows a normal distribution, and if the actual data distribution deviates from normality, the classification results may be biased. In contrast, using the RWI method for thermokarst lake identification in the same region, a total of 620 lakes were identified, with a total area of 433.97 ha. It can be observed that, contrary to the “over-extraction” by MLC, the errors of RWI are primarily concentrated in “omissions”, with error rates for the number and area of lakes being 16% and 12%, respectively. This indicates that the RWI method is relatively superior.

For lakes with areas ranging from 0.04 to 1 ha, MLC extracted 902 lakes with a total area of 196 ha. The error rates for the number and area of lakes were 25.83% and 19.21%, respectively. Compared with the results of visual interpretation, the RWI extraction missed 101 lakes, with a total area of 19.69 ha, accounting for 11.98% of the total lake area and 14.09% of the total number of lakes. This demonstrates that RWI also exhibits omission issues in the extraction of small thermokarst lakes, which is likely related to its lower sensitivity to the spectral signals of small water bodies, particularly those smaller than 0.1 ha. In contrast, although the MLC method used by Șerban et al. demonstrated outstanding classification accuracy, it significantly overestimated both the number and area of lakes compared to visual interpretation. Even in the 0.04–1 ha lake sub-category, the 902 lakes (with a total area of 196 ha) extracted by MLC still showed error rates of 25.83% in number and 19.21% in area. This overestimation stems from the mismatch between MLC’s specific assumptions about data statistical properties (such as the default assumption of normal distribution) and the actual spectral characteristics of the Chalaping region. More critically, the widespread presence of “lake-meadow-peatland” mixed pixels in the lake shoreline areas of this region leads MLC to frequently misclassify these non-water areas as water bodies, resulting in dual overestimation of lake number and area. In comparison, although RWI has issues with omitting small lakes, it shows no significant misclassification of non-water areas. Its accuracy in estimating the total lake area is slightly better than that of MLC, and it demonstrates greater advantage in controlling overall deviations in lake number statistics.

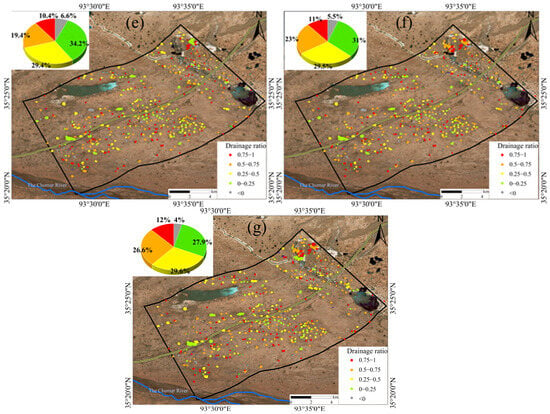

3.4. Spatiotemporal Distribution of Thermokarst Lake Drainage

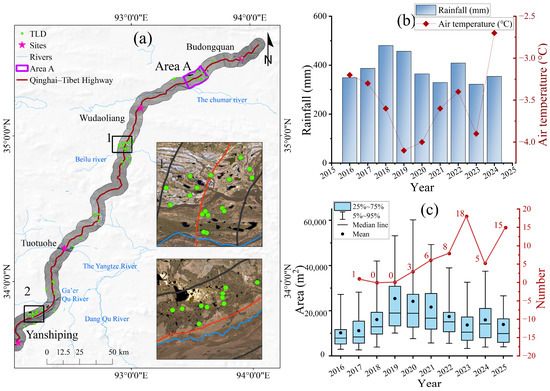

A total of 56 thermokarst lake drainage events meeting the criteria (area > 1 ha in the benchmark year and subsequent drainage ratio ≥ 50%) were identified. Along the QTH, there are 733 thermokarst lakes larger than 1 ha, yet only 7.64% of them satisfy the conditions for drained lakes. This indicated that the drainage phenomenon of thermokarst lakes is not widespread along the QTH, which is similar to the research results in the Arctic region [15]. All thermokarst lake drainage events were located north of Yanshiping; thus, only this region is illustrated in Figure 4. Spatial analysis revealed a pronounced clustering pattern, mainly concentrated south of Wudaoliang and north of Yanshiping. These drained lakes are spatially adjacent, implying the possible existence of interconnected drainage systems. Moreover, a high density of drained lakes was observed in the basins of major rivers such as the Chumar River and the Yangtze River and their tributaries, demonstrating strong fluvial dependence. This spatial pattern suggests that riverbank erosion, groundwater dynamics, and surface runoff convergence may jointly influence thermokarst lake drainage. River erosion may both weaken the stability of lake shores and provide potential outflow channels for lake water. Analysis of the initial lake size prior to drainage showed a clear concentration trend, with initial areas ranging from 1 to 3 ha, indicating that small and medium-sized thermokarst lakes are more susceptible to drainage. This phenomenon is likely linked to the lower stability of ice-wedge polygon structures surrounding small lakes, whose periglacial formations are more easily breached under thermal or hydraulic forces, leading to sudden drainage channels. This mechanism demonstrates that thermokarst lake drainage exhibits strong geomorphic and structural dependence.

Figure 4.

(a) Spatial distribution map of thermokarst lakes drainage (TLD), (b) Statistical chart of air temperature and rainfall, and (c) Changes in total area of thermokarst lake drainage.

To assess the impact of the RWI extraction error on the identification of drainage events, we conducted an uncertainty analysis. Given that the RWI has an area extraction error of approximately 10.21%, this error propagates into the drainage ratio calculation. We established a conservative scenario by raising the identification threshold from 50% to 60% (i.e., DR > 60%). Under this more stringent criterion, 52 events were still successfully identified, and their spatiotemporal patterns (e.g., predominance post-2019, concentration in the Wudaoliang-Yanshiping area) remained entirely consistent with the results using the 50% threshold. This demonstrates that while the absolute count of drainage events might be a conservative estimate, the main spatiotemporal trends we revealed are robust and not significantly influenced by index extraction errors.

Among the drained lakes, 51 (91.07% of the total) exhibited continuous area reduction over at least three years, indicating a persistent degradation trend. This finding suggests that most drainage events result from gradual, multi-stage degradation rather than a single catastrophic collapse. To further analyze temporal patterns, area distribution histograms of drained lakes were compiled for each year. The results show that the average area of drained lakes increased steadily from 2016 to 2019, declined after 2020, and slightly rebounded in 2024 and 2025. Meanwhile, the number of drainage events per year rose continuously after 2019, peaking in 2023, then slightly decreasing in 2024 before increasing again in 2025, reflecting distinct interannual fluctuations in thermokarst lake drainage frequency.

To explore the potential drivers behind the increasing drainage frequency, two climatic variables—annual average temperature and annual rainfall—were analyzed (Figure 4b,c). Preliminary correlation analysis revealed a weak and statistically insignificant negative correlation between temperature and the number of drained lakes (r = –0.14). However, interannual variations showed that abnormal temperature rises in 2022 and 2024 coincided with sharp increases in drainage events in 2023 and 2025, respectively. Given that permafrost thaw and its hydrological impacts often exhibit a lagged response to temperature increases, we specifically tested the effect of a one-year lag. When the temperature data lagged by one year, the correlation coefficient increased to r = 0.37, p < 0.1. This strengthens the observation that higher temperatures in the preceding year may promote thermokarst lake drainage in the following year, likely by accelerating permafrost thaw and destabilizing lake basins.

Conversely, rainfall exhibited a moderate negative correlation with the number of drained lakes (r = −0.57, p < 0.1), meaning that drainage events were more frequent during relatively dry years. This finding contrasts with the conventional notion that extreme rainfall triggers thermokarst lake drainage [43]. A detailed examination showed no drained lakes in 2018–2019; instead, lakes expanded with higher rainfall. This reflects the “recharge effect” of rainfall in intact permafrost zones: when permafrost structures remain stable, increased rainfall replenishes lake water storage and delays drainage by maintaining hydrological equilibrium [15]. In contrast, 2022 rainfall did not cause expansion but induced 2023 drainage surges. This “triggering effect” is linked to prior permafrost degradation: long-term warming had deepened the active layer and melted ice wedges, creating porous pathways in the permafrost. Under such conditions, rainfall accelerates drainage by eroding weakened shorelines and enhancing subsurface thaw [15,43]. In summary, thermokarst lake drainage is a complex process governed by the interplay of temperature and rainfall. Its occurrence depends not only on current climatic conditions but also on prior thermal accumulation and hydrological settings.

4. Discussion

4.1. Advantages of the RWI

In this study, five water indices were compared using four evaluation indicators—OA, Kappa coefficient, PA, and UA. The findings confirmed that the new water index RWI has three core advantages in surface water mapping and change analysis, which significantly enhance its application value.

First, the RWI excels in mapping accuracy. Its OA, Kappa coefficient, and PA values are significantly higher than those of the other four water indices, directly boosting the accuracy of surface water mapping and change analysis. This high accuracy stems from the RWI’s unique band combination: it incorporates the red edge band (B5) and short-wave infrared band (B12) of Sentinel-2 images. This combination enhances the spectral separability between water bodies and mixed pixels, and synergistically amplifies the “spectral contrast”—that is, water’s relatively high reflectance in the green-red edge region versus its strong absorption in the near-infrared-short-wave infrared region. For mixed pixels (common at water-non-water boundaries), this enhanced contrast makes their spectral response more similar to pure water than background features, enabling more accurate classification as water. Even for small lakes that traditional indices fail to extract precisely, the RWI can achieve high-precision identification through simple threshold segmentation, effectively addressing the limitation of traditional indices that often miss small lakes.

The RWI also benefits from a simpler, more stable methodology that is independent of sample data. It improves the separability of water and non-water classes through a straightforward, systematic approach: it maximizes the distinction between the two by leveraging their inherent differences in surface reflectance, specifically utilizing the intrinsic reflectance variations in water and non-water surfaces across all spectral bands of Sentinel-2 images. This ensures stable performance across test sites in four different regions while effectively enhancing contrast between the two classes. In contrast, traditional indices like AWEInsh and AWEIsh require complex iterative processes or statistical methods to determine their optimal coefficients. This not only increases operational difficulty but also makes these indices highly sample-dependent, which may compromise their effectiveness in different regions [36].

Beyond accuracy and methodological simplicity, the RWI also stands out for its independence from additional data—a trait that makes it well-suited for global-scale mapping. It does not require supplementary data like Digital Elevation Model (DEM) to eliminate noise from shadows and dark areas, which are often the primary sources of error in lake detection and classification. This greatly streamlines the lake detection workflow. By contrast, the six-step GeoCover Water Bodies Extraction Method proposed by Verpoorter et al. [44] requires integrating multiple classification techniques and leveraging DEM data to detect shadows, thereby removing water surfaces that overlap with shadowed areas. This not only increases reliance on DEM data but also complicates the operational process. The RWI’s “no additional data” characteristic means it is not constrained by the availability of auxiliary data, rendering it particularly suitable for lake mapping in diverse scenarios or on a global scale—especially in regions where auxiliary data are scarce or hard to acquire.

4.2. Small Thermokarst Lake Drainage

Most existing studies on thermokarst lake drainage focus on lakes with an initial area greater than 1 ha. However, on the QTP, the majority of thermokarst lakes are smaller than 1 ha. These small lakes dominate in number, and their dynamic variations are crucial for understanding regional hydrothermal processes and carbon cycling [45]. The RWI proposed in this study greatly improves the identification of small-scale water bodies, enabling accurate extraction of thermokarst lakes with areas exceeding 0.05 ha, thereby addressing the limitations of conventional methods in monitoring medium and extremely small thermokarst lakes. Based on this technical advancement, a key scientific question arises: Do small thermokarst lakes (0.05–1 ha) also undergo drainage? If so, how do their drainage mechanisms, frequencies, and environmental drivers differ from those of larger thermokarst lakes?

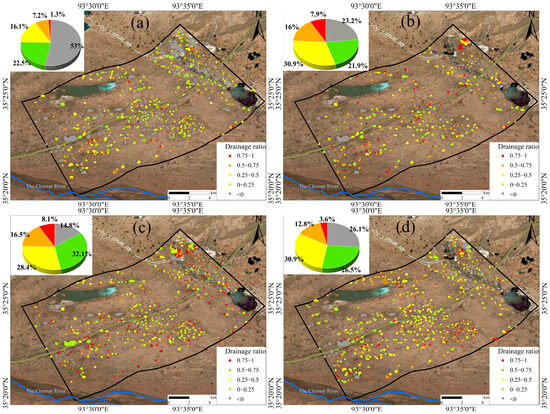

To investigate drainage in small thermokarst lakes, Area A (Figure 5)—representing the region with the highest concentration of such lakes—was selected. Preliminary observations revealed that compared with 2016 and 2017, most small thermokarst lakes in 2018 exhibited clearer morphologies and larger surface areas, facilitating more accurate identification and subsequent calculation of drainage ratios. Therefore, 2018 was chosen as the baseline year, and the evolutionary dynamics of small thermokarst lakes were analyzed for 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023, 2024 and 2025 (Figure 5). The results show that although some lakes expanded, the overall system displayed a pronounced trend of shrinkage and drainage. From 2018 to 2025, the proportion of significantly drained lakes (drainage ratio > 0.5) rose markedly from 8.5% to 38.6%, while the proportion of completely or nearly completely drained lakes (drainage ratio > 0.75) increased almost tenfold—from 1.3% to 12%. These findings confirm that drainage events are common and frequent among small thermokarst lakes, and that their drainage rates and intensities may even surpass those of larger lakes.

Figure 5.

Drainage ratio diagram of small thermokarst lakes in Area A for 2019 (a), 2020 (b), 2021 (c), 2022 (d), 2023 (e), 2024 (f) and 2025 (g) (Based on 2018).

This phenomenon is mainly attributed to their inherent size and fragility. Firstly, the small surface area and limited water volume make the hydrothermal balance of these lakes highly sensitive to disturbance. Unlike large lakes with greater heat capacity and stability, small thermokarst lakes respond quickly to short-term droughts or warm seasons, which can significantly disrupt their water balance and cause a rapid transition from a water-filled to a drained or dried state. Secondly, their shallow basins and unstable moraine or ground-ice foundations facilitate the formation of drainage channels [43]. These lakes typically form in shallow permafrost or ice-rich moraines, where the aquitard beneath the basin is thin and discontinuous. Under thermal erosion, the lake bottom or sidewalls can easily rupture, linking to nearby hydrological networks—such as ground-ice meltwater conduits or seasonal streams—and creating efficient drainage pathways that trigger “sudden drainage” [15]. In contrast, large thermokarst lakes require longer thermal accumulation and greater energy to penetrate thicker, more stable permafrost layers.

Therefore, this study confirms that drainage is not exclusive to large thermokarst lakes. It is widespread and often more intense among small thermokarst lakes, which are dominant in number. Their “small and fragile” characteristics make them the most sensitive indicators of permafrost hydrothermal changes. Frequent and rapid drainage-drying cycles accelerate local permafrost thermal disturbance and hydrological reorganization, exerting significant influence on regional carbon dynamics—for example, facilitating a rapid shift from methane emission to carbon sequestration.

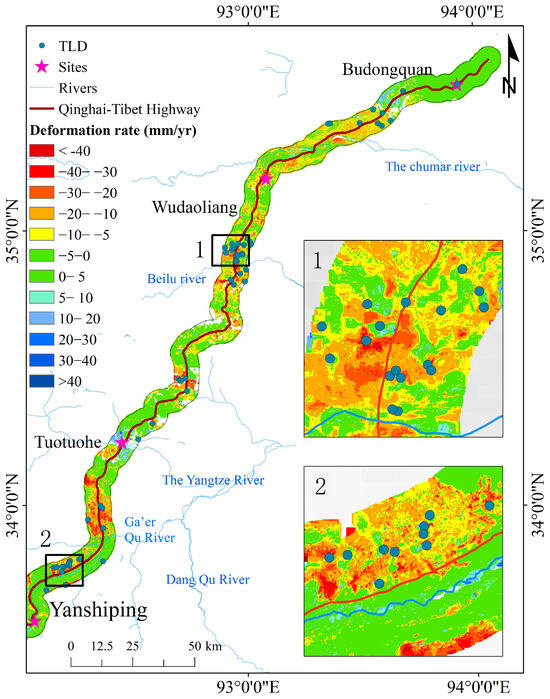

4.3. Thermokarst Lake Drainage and Surface Subsidence

Thermokarst lake drainage is a key geomorphic process in permafrost regions under climate warming. Its fundamental driver is permafrost degradation, while surface subsidence serves as an important indicator of this degradation. As two manifestations of permafrost thawing, the coupling mechanism between thermokarst lake drainage and surface subsidence warrants in-depth investigation. Yu et al. first proposed that surface subsidence acts as a critical precondition and triggering factor for thermokarst lake drainage and emphasized a positive feedback mechanism whereby both processes are coupled and mutually reinforced [43]. To verify this relationship and evaluate the accuracy of drained lake identification, an overlay analysis was performed between the SBAS-InSAR–derived surface deformation results and the identified thermokarst lakes drainage (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Overlay map of surface deformation and thermokarst lake drainage.

The spatial overlay analysis revealed a clear spatial correlation between thermokarst lake drainage and surface subsidence. As shown in the subsidence rate map, most drained lakes are located in high-subsidence-value zones. This spatial pattern demonstrates that thermokarst lake drainage events are strongly associated with intense permafrost degradation and subsidence, confirming subsidence as a precondition for drainage. To further quantify this relationship, we compared a series of average subsidence rates: the baseline for the entire study area (3.92 mm/yr), the rate for thermokarst lakes larger than 1 ha (9.05 mm/yr), and the rate specifically for drained lake sites (12.32 mm/yr). Comparison shows that areas affected by thermokarst processes subside faster than the regional average, with drainage events occurring preferentially in the most rapidly settling locations, confirming subsidence as a key precondition for drainage. Furthermore, we computed the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient between the drainage density of each pixel and the settlement rate. The results indicate a strong positive correlation between the two (Spearman’s rho = 0.78, p < 0.001), which further supports the close association between thermokarst lake development and localized significant settlement.

Surface subsidence primarily influences lake drainage by destabilizing lake shores and facilitating the formation of drainage channels. When permafrost thawing induces subsidence, the ice content in the lake shore foundation decreases, reducing its structural integrity and promoting the development of lateral drainage fissures or collapse zones that enable water outflow [46]. Additionally, subsidence caused by ice-water phase transitions raises lake water levels and internal pressure. Once the water level surpasses the minimum overflow threshold of the subsided lake shore, active overflow drainage occurs. Simultaneously, meltwater infiltration softens the permafrost at the lake bottom, promoting bottom-channel development and accelerating lake water infiltration [10].

Conversely, thermokarst lake drainage can further intensify surface subsidence. After lake water drains, the lakebed permafrost—previously insulated by water—is directly exposed to the atmosphere. Because the thermal conductivity of water is lower than that of air, this exposure enhances heat penetration, leading to accelerated thawing of ground ice and causing secondary subsidence [43]. Moreover, the lateral and basal drainage channels created during the drainage process act as “hydrological connectors”, directing meltwater toward surrounding permafrost areas. This facilitates the thawing of adjacent ice-rich zones, expanding the scope of subsidence outward from the lake margins [43].

This sequence forms a self-reinforcing positive feedback loop: initial subsidence triggers lake drainage, which subsequently induces further and more widespread secondary subsidence. Consequently, thermokarst lake drainage does not mark an end state but rather the onset of a new, more destructive subsidence phase. This ongoing process profoundly alters local hydrological, ecological, and geotechnical conditions, poses severe risks to infrastructure, and releases substantial amounts of organic carbon stored in permafrost, thereby amplifying climate change.

4.4. Limitations and Inspirations

Although this study has achieved effective results in extracting thermokarst lakes and identifying drainage events based on Sentinel-2 imagery, and has demonstrated the superiority of the RWI, several limitations remain. Firstly, the study area is concentrated along the buffer zone of the QTH, and the generalizability of its conclusions to different geomorphological and climatic regions across the entire QTP requires further verification. Secondly, when evaluating the performance of different water indices, we primarily focused on areal accuracy and failed to systematically investigate the impact of environmental factors such as topography and vegetation cover on the extraction results, potentially leading to an incomplete assessment. Furthermore, in analyzing the driving mechanisms of drainage events, we focused solely on meteorological elements like air temperature and precipitation, without incorporating key confounding factors such as active layer thickness, ground ice content, and human activities along the QTH. This limits a deeper understanding of the causes of drainage. Additionally, the results of this study rely entirely on remote sensing data inversion and lack validation from field observations, which somewhat affects the robustness of the conclusions.

Looking ahead, future research can be deepened and expanded in several directions. The primary task is to extend the methodology validated in this study to the entire QTP, evaluating its regional adaptability and generalizability by comparing the dynamics of thermokarst lakes across different geomorphological units. Methodologically, a more comprehensive evaluation framework should be established, integrating multi-source environmental data like topography, vegetation, and soil properties into the accuracy assessment of water body extraction to enhance the model’s robustness in complex environments. To more accurately reveal the driving mechanisms of thermokarst lake drainage, it is necessary to integrate multi-source data (e.g., geophysical surveys, long-term ground monitoring) to build a comprehensive model that incorporates thermal state, hydrological processes, and human activity factors. Particularly important is strengthening field validation work in typical areas, combining ground measurements with UAV remote sensing to provide solid ground truth support for the remote sensing inversion results. Simultaneously, actively exploring technical pathways that integrate advanced algorithms like machine learning with traditional remote sensing indices holds promise for breakthroughs in the intelligent identification and dynamic monitoring of thermokarst lakes. Ultimately, the outcomes of these research efforts will provide a more solid scientific foundation for engineering safety risk assessment on the QTP and early warning of thermokarst-related geohazards.

5. Conclusions

This study utilized Sentinel-2 imagery for surface water identification along the QTH, enhancing extraction accuracy by maximizing the spectral contrast between water and non-water surfaces. Five commonly used water indices—AWEInsh, AWEIsh, MNDWI, MBWI, and RWI—were comparatively analyzed under varying regional and seasonal conditions. The optimal index was then applied to identify thermokarst lake drainage events from 2016 to 2025. The main conclusions are as follows:

Within the study area, the RWI demonstrated the best overall performance, with Kappa coefficient, OA, and PA values of 0.86, 93.50%, and 85.61%, respectively. In thermokarst lake water-body extraction, the performance of RWI was markedly superior to other indices. When the automatically extracted water extents were compared with manually interpreted results, the error rates were 26.21% for AWEInsh, 12.60% for AWEIsh, 38.80% for MBWI, 41.36% for MNDWI, and 10.21% for RWI. These values highlight significant accuracy differences among indices in automatic water-body extraction. Additionally, the effectiveness of each index varied seasonally.

A total of 56 thermokarst lake drainage events (accounting for 7.64% of the total) were identified in the study area. These drained lakes displayed clustered spatial patterns, primarily concentrated in high-subsidence zones such as the southern Wudaoliang and northern Yanshiping regions. Their initial areas before drainage were mostly below 3 ha. Most drainage processes persisted for more than three years (91.07% of cases), and the majority occurred after 2019 (55 lakes), indicating a close association with climatic variability. Further analysis revealed that small thermokarst lakes exhibited more frequent and pronounced drainage due to their structural instability and high sensitivity to environmental change.

Overall, the findings of this study provide critical insights for thermokarst lake monitoring across the QTP. Given the crucial role of small thermokarst lakes in regulating regional hydrology, ecosystem stability, and engineering safety, future projections of climate change and global water resource management should explicitly account for the distribution and dynamic evolution of small thermokarst lakes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.L., G.Z. and W.L.; methodology, T.L. and G.Z.; software, T.L. and G.Z.; validation, T.L., G.Z. and W.L.; formal analysis, T.L. and G.Z.; investigation, T.L., J.Z., R.H. and H.Y.; resources, W.L. and H.L.; writing—original draft preparation, T.L. and G.Z.; writing—review and editing, T.L., W.L. and G.Z.; visualization, G.Z., T.L. and W.L.; supervision, W.L. and H.L.; project administration, W.L.; funding acquisition, W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was jointly supported by the Applied Basic Research Program of Qinghai Province (2025-ZJ-753) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42561008).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| QTP | Qinghai–Tibet Plateau |

| QTH | Qinghai–Tibet Highway |

| RWI | Red Edge Water Index |

| AWEIsh AWEInsh | Automated Water Extraction Index |

| MBWI | Multi-Band Water Index |

| MNDWI | Modified Normalized Difference Water Index |

| SBAS-InSAR | Small Baseline Subset Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar |

| PA | Producer Accuracy |

| OA | Overall Accuracy |

| UA | User Accuracy |

| MLC | Maximum Likelihood Classification |

References

- Zhang, G.; Yao, T.; Xie, H.; Zhang, K.; Zhu, F. Lakes’ state and abundance across the Tibetan Plateau. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2014, 59, 3010–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Liu, S.; Xu, J.; Wu, L.; Shangguan, D.; Yao, X.; Wei, J.; Bao, W.; Yu, P.; Liu, Q.; et al. The second Chinese glacier inventory: Data, methods and results. J. Glaciol. 2015, 61, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, D.; Zhao, L.; Sheng, Y.; Chen, J.; Hu, G.; Wu, T.; Wu, J.; Xie, C.; Wu, X.; Pang, Q.; et al. A new map of permafrost distribution on the Tibetan Plateau. Cryosphere 2017, 11, 2527–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, C.; Barros, V. Climate Change 2014–Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Regional Aspects; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Wang, M.; Zhou, T.; Chen, W. Progress in remote sensing monitoring of lake area, water level, and volume changes on the Tibetan Plateau. Natl. Remote Sens. Bull. 2022, 26, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokelj, S.; Jorgenson, M. Advances in thermokarst research. Permafr. Periglac. Process. 2013, 24, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Ma, K.; Jia, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, C.; Li, X. Community Assembly and Co-Occurrence Patterns of Microeukaryotes in Thermokarst Lakes of the Yellow River Source Area. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muster, S.; Roth, K.; Langer, M.; Lange, S.; Cresto Aleina, F.; Bartsch, A.; Morgenstern, A.; Grosse, G.; Jones, B.; Sannel, A.B.K.; et al. PeRL: A circum-Arctic permafrost region pond and lake database. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2017, 9, 317–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, F.; Luo, J.; Lin, Z.; Liu, M.; Yin, G. Morphological characteristics of thermokarst lakes along the Qinghai-Tibet engineering corridor. Arct. Antarct Alp. Res. 2014, 46, 963–974. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24551858 (accessed on 1 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Nitze, I.; Grosse, G.; Jones, B.M.; Romanovsky, V.E.; Boike, J. Remote sensing quantifies widespread abundance of permafrost region disturbances across the Arctic and Subarctic. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 5423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Zheng, Z.; Abbott, B.W.; Olefeldt, D.; Knoblauch, C.; Song, Y.; Kang, L.; Qin, S.; Peng, Y.; Yang, Y. Characteristics of Methane Emissions from Alpine Thermokarst Lakes on the Tibetan Plateau. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Niu, F.J.; Lin, Z.J.; Liu, M.H.; Yin, G.A.; Gao, Z.Y. Abrupt Increase in Thermokarst Lakes on the Central Tibetan Plateau Over the Last 50 Years. Catena 2022, 217, 106497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, E.; Liljedahl, A. Diminishing Lake Area Across the Northern Permafrost Zone. Nat. Geosci. 2023, 16, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turetsky, M.R.; Abbott, B.W.; Jones, M.C.; Anthony, K.W.; Olefeldt, D.; Schuur, E.A.G.; Grosse, G.; Kuhry, P.; Hugelius, G.; Koven, C.; et al. Carbon Release Through Abrupt Permafrost Thaw. Nat. Geosci. 2020, 13, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Cheng, X.; Liu, A.; Chen, Q.; Wang, C. Tracking Lake Drainage Events and Drained Lake Basin Vegetation Dynamics Across the Arctic. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, M.; Mu, C.; Liu, H.; Lei, P.; Ge, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Peng, X.; Ma, T. Thermokarst Lake Drainage Halves the Temperature Sensitivity of CH4 Release on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Wang, H.; Cui, P.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Wei, R.L.; Liu, Z.-X.; Li, C.-Y. Formation and Evolution of Thermokarst Landslides in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buma, W.G.; Lee, S.-I.; Seo, J.Y. Recent Surface Water Extent of Lake Chad from Multispectral Sensors and GRACE. Sensors 2018, 18, 2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFeeters, S. The Use of the Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) in the Delineation of Open Water Features. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1996, 17, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H. A Study on Information Extraction of Water Body with the Modified Normalized Difference Water Index (MNDWI). J. Remote Sens. 2005, 9, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danaher, T.; Collett, L. Development, Optimisation and Multi-Temporal Application of a Simple Landsat Based Water Index. In Proceedings of the 13th Australasian Remote Sensing and Photogrammetry Conference, Canberra, Australia, 20–24 November 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Xie, S.; Zhang, X.; Chen, C.; Guo, H.; Du, J.; Duan, Z. A Robust Multi-Band Water Index (MBWI) for Automated Extraction of Surface Water from Landsat 8 OLI Imagery. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. 2018, 68, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Wang, M.; Shen, Q.; Yao, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, Y. Small Water Body Extraction Method Based on Sentinel-2 Satellite Multi-Spectral Remote Sensing Image. Natl. Remote Sens. Bull. 2022, 26, 781–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Qin, Q.; Grussenmeyer, P.; Koehl, M. Urban Surface Water Body Detection with Suppressed Built-Up Noise Based on Water Indices from Sentinel-2 MSI Imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 219, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wang, S.; Huang, C. Comparison of Sentinel-2 Imagery with Landsat8 Imagery for Surface Water Extraction Using Four Common Water Indexes. Remote Sens. Land Resour. 2019, 31, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ling, F.; Wang, Q.; Li, W.; Li, X. Water Bodies’ Mapping from Sentinel-2 Imagery with Modified Normalized Difference Water Index at 10-m Spatial Resolution Produced by Sharpening the SWIR Band. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Niu, F.; Lin, Z.; Liu, M.; Yin, G. Thermokarst Lake Changes Between 1969 and 2010 in the Beilu River Basin, Qinghai–Tibet Plateau, China. Sci. Bull. 2015, 60, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Du, Z.; Wang, L.; Lin, J.; Feng, Y.; Xu, Q.; Xiao, C. Sentinel-Based Inventory of Thermokarst Lakes and Ponds Across Permafrost Landscapes on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Earth Space Sci. 2021, 8, e2021EA001950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Niu, F.; Fang, J.; Luo, J.; Yin, G. Interannual Variations in the Hydrothermal Regime Around a Thermokarst Lake in Beiluhe, Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Geomorphology 2017, 276, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitze, I.; Cooley, S.; Duguay, C.; Jones, B.; Grosse, G. The Catastrophic Thermokarst Lake Drainage Events of 2018 in Northwestern Alaska: Fast-Forward Into the Future. Cryosphere 2020, 14, 4279–4297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, A.; Cheng, X. Detection of Thermokarst Lake Drainage Events in the Northern Alaska Permafrost Region. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 807, 150828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, H.; Tang, Y.; Duan, W.; Dong, L. Freeze-Thaw Deformation Cycles and Temporal-Spatial Distribution of Permafrost Along the Qinghai-Tibet Railway Using Multitrack InSAR Processing. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Tang, T.; Huang, X.; Ding, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, D. Thermal Stability Investigation of Wide Embankment with Asphalt Pavement for Qinghai-Tibet Expressway Based on Finite Element Method. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 115, 874–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhang, T. Recent Permafrost Warming on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. J. Geophys. Res-Atmos. 2008, 113, D13108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Wu, T. Responses of Permafrost to Climate Change and Their Environmental Significance, Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 2007, 112, F02S03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyisa, G.L.; Meilby, H.; Fensholt, R.; Proud, S.R. Automated Water Extraction Index: A New Technique for Surface Water Mapping Using Landsat Imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 140, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekel, J.-F.; Cottam, A.; Gorelick, N.; Belward, A.S. High-Resolution Mapping of Global Surface Water and Its Long-Term Changes. Nature 2016, 540, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frantz, D.; Haß, E.; Uhl, A.; Stoffels, J.; Hill, J. Improvement of the Fmask Algorithm for Sentinel-2 Images: Separating Clouds from Bright Surfaces Based on Parallax Effects. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 215, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Jin, Y.; Zhu, W.; Lee, D. High Spatiotemporal-Resolution Mapping for a Seasonal Erosion Flooding Inundation Using Time-Series Landsat and MODIS Images. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deluigi, N.; Lambiel, C.; Kanevski, M. Data-Driven Mapping of the Potential Mountain Permafrost Distribution. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 590–591, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Li, J.; Zheng, G. Lake-Area Mapping in the Tibetan Plateau: An Evaluation of Data and Methods. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2017, 38, 742–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Șerban, R.-D.; Jin, H.; Șerban, M.; Luo, D.; Wang, Q.; Jin, X.; Ma, Q. Mapping Thermokarst Lakes and Ponds Across Permafrost Landscapes in the Headwater Area of Yellow River on Northeastern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2020, 41, 7042–7067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Hui, F.; Zhou, Y.; Cheng, X.; Ding, M. The Interaction Between Thermokarst Lake Drainage and Ground Subsidence Accelerates Permafrost Degradation. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 2025, 16, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verpoorter, C.; Kutser, T.; Tranvik, L. Automated Mapping of Water Bodies Using Landsat Multispectral Data. Limnol Ocean. Meth. 2012, 10, 1037–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muster, S.; Langer, M.; Heim, B.; Westermann, S.; Boike, J. Subpixel Heterogeneity of Icewedge Polygonal Tundra: A Multi-Scale Analysis of Land Cover and Evapotranspiration in the Lena River Delta, Siberia. Tellus B 2012, 64, 17301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.; Grosse, G.; Farquharson, L.; Roy-Léveillée, P.; Veremeeva, A.; Kanevskiy, M.; Gaglioti, B.V.; Breen, A.L.; Parsekian, A.D.; Ulrich, M.; et al. Lake and Drained Lake Basin Systems in Lowland Permafrost Regions. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).