Abstract

This study evaluates occupational exposure to respirable particulate matter (PM2.5) and crystalline silica (c-silica) among workers in five ceramic industries in Indonesia. Personal sampling revealed that 55.3% of workers were exposed to c-silica levels exceeding the Threshold Limit Value (TLV) of 50 µg/m3, with concentrations ranging from 1.5 to 1395.3 µg/m3. PM2.5 levels reached as high as 4152.4 µg/m3 in certain production zones. Health surveys identified frequent respiratory symptoms such as shortness of breath (27.1%) and chronic cough (14.6%), with 6.4% of workers showing lung abnormalities on chest X-rays. Risk assessments based on chronic daily intake (CDI), hazard quotient (HQ), and risk quotient (RQ) revealed that 63.8% of workers faced unsafe exposure, particularly those with longer job tenures, older age, and poor compliance with personal protective equipment (PPE). To mitigate risks, the study recommends engineering controls such as more local exhaust ventilation, improved PPE usage, and administrative measures including job rotation and regular health monitoring. These findings highlight the urgent need for improved occupational health strategies in silica-intensive industries and call for further research on long-term health impacts and effective intervention programs.

1. Introduction

The ceramic industry plays an essential role worldwide, producing a wide array of products from household items to construction materials [1,2]. Traditionally, ceramics were primarily used for basic applications, but advancements have led to their integration in fields such as electronics, engineering, and medicine, largely due to their durability and versatility [3,4]. Classical ceramic products are composed primarily of clay, feldspar, and sand [5]. Clay, a hydrated aluminum silicate derived from feldspar weathering, is central to ceramic production [6]. The ceramic manufacturing process involves multiple stages, including raw material preparation, forming, drying, firing, and glazing [7]. Each of these stages can generate significant quantities of airborne dust, especially fine particles such as PM2.5 (particles with an aerodynamic diameter of less than 2.5 µm), which often contain silica and pose serious occupational health risks [8,9,10]. PM2.5 can penetrate deeply into the human respiratory system and has been linked to various respiratory and cardiovascular diseases. Occupational environments with high PM2.5 levels, particularly in industries involving high-temperature processes and raw material handling, may present combined risks from both PM and silica exposure. Silica is primarily sourced from clay in the ground and, when exposed to high temperatures, becomes a major respiratory hazard for workers [11,12,13].

In the ceramic industry, silica dust exposure is a predominant hazard, especially once silica transforms into crystalline forms like quartz, tridymite, and cristobalite at high temperatures [14,15,16]. Silica, or silicon dioxide (SiO2), is one of the Earth’s most abundant minerals, existing predominantly in crystalline form with minor amorphous occurrences [17,18]. Crystalline silica is commonly found in rocks, sand, and soil and is prevalent in industrial processes such as mining, foundries, and ceramic production [19,20,21]. Inhalation of silica particles allows them to penetrate deeply into the respiratory system, leading primarily to silicosis, a progressive lung disease characterized by fibrosis and reduced lung function, particularly from chronic exposure [21,22,23].

Silicosis remains a common occupational health issue among workers exposed to high silica levels [24,25,26]. Industries involving stone, granite, coal, tin, iron, and ceramics are known for high incidences of silicosis among workers [20,27,28]. Previous studies indicate that the incubation period for silicosis ranges from 2 to 4 years, depending on exposure concentration [29]. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classifies crystalline silica as a Group 1 carcinogen due to its strong association with lung cancer [30]. Globally, studies have highlighted the severe health impacts of prolonged silica exposure [31,32,33,34,35,36]. For instance, research in China has shown that silica exposure can increase mortality rates from respiratory diseases, tuberculosis, and cardiovascular issues [36,37,38,39,40,41]. Estimates suggest that over 23 million workers in China and around 10 million in India are at risk from silica exposure, and similar occupational hazards are reported in other industrialized and developing nations, highlighting silica exposure as a significant global occupational health concern [42,43]. Silica exposure is associated not only with silicosis but also with lung inflammation, fibrosis, and systemic immune impairments [18,44].

Despite the well-documented health risks associated with silica exposure, Indonesia lacks comprehensive national data on silicosis prevalence [41,45]. Most existing information is derived from smaller studies with limited sample sizes. For instance, a study in a cement factory found that 0.5% of workers were suspected of having silicosis [46]. while a study in West Java reported a 2.06% silicosis rate from 1990 to 2003 [47]. Further epidemiological research suggests that current occupational exposure limits for silica may be insufficient to protect workers fully [48,49]. Studies from the United States, Canada, and South Africa reveal significant silicosis risks even at silica concentrations below established safety standards [50,51,52]. In accordance with the Regulation of the Minister of Manpower of the Republic of Indonesia Number 5 of 2018 concerning Occupational Safety and Health in the Work Environment (Ministerial Regulation No. 5/2018), in Indonesia, the permissible exposure limit for crystalline silica dust is set at 0.05 mg/m3 [53], may require reassessment to prevent irreversible lung damage, which remains incurable once fibrosis is established.

As a developing country, Indonesia hosts numerous ceramic industries, which are spread widely across the region. However, many workers neglect essential safety measures, such as using masks and protective eyewear, which exacerbates the health risks associated with silica exposure. Additionally, the scarcity of comprehensive data from previous studies underscores the need for further research in this area. This study aims to conduct a quantitative risk assessment of silica dust exposure among production workers in five ceramic industries (namely A–E) in Gresik, East Java, Indonesia. Specifically, the research objectives include analyzing worker characteristics (e.g., tenure, age, smoking habits, PPE usage), measuring silica dust concentration in production areas, assessing exposure-related risks, analyzing chest X-rays for silica-related effects, examining the relationship between worker characteristics and respiratory symptoms, and estimating the chronic exposure risk over a projected 30-year period. By examining these variables, the study seeks to provide critical insights into the occupational health risks faced by workers in Indonesia’s ceramic industry and offers recommendations to enhance workplace safety and reduce silica exposure.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Sites and Population

This study employs a cross-sectional design to assess occupational exposure to PM2.5 and silica among ceramic industry workers in Gresik, East Java, Indonesia. The study was conducted across five ceramic manufacturing industries in Indonesia, each with unique characteristics in terms of production capacity, focus, and employee size, providing a broad representation of the ceramic sector in the country. Industry A, established in 2002, is a ceramic manufacturing company specializing in products that feature traditional Indonesian batik patterns. It employs 745 workers and has achieved the Indonesian National Standard (SNI) certification for its products. This facility has a production capacity of 18.09 million square meters per year, reflecting its significant role in the local ceramic industry.

Industry B, founded in 2013, is recognized for producing high-quality ceramics. Equipped with four production machines, this company has a production capacity of 36 million square meters per year, positioning it as a leading manufacturer in terms of productivity and scale. Industry C, established in 1991, focuses on meeting national demand for ceramic tiles. This facility specializes in floor and wall tiles, offering nearly 1000 patterns in various sizes, finishes, and styles. With a production capacity exceeding 24 million square meters per year, Industry C plays a crucial role in the Indonesian ceramic market by providing diverse product options. Industry D, founded in 1971, has a long-standing history in the ceramic industry. It produces a wide range of ceramic products, including floor and wall tiles, which are distributed globally to millions of customers. With an impressive production capacity of approximately 53.2 million square meters per year, Industry D represents one of the most prominent players in the industry, catering to both domestic and international markets. Industry E, the most recently established company, was founded in 2016. Like Industry A, it incorporates traditional Indonesian batik patterns into its ceramic designs and holds SNI certification. This company employs 401 workers and has a production capacity of 11 million square meters per year, contributing to the cultural and aesthetic aspects of the Indonesian ceramic industry.

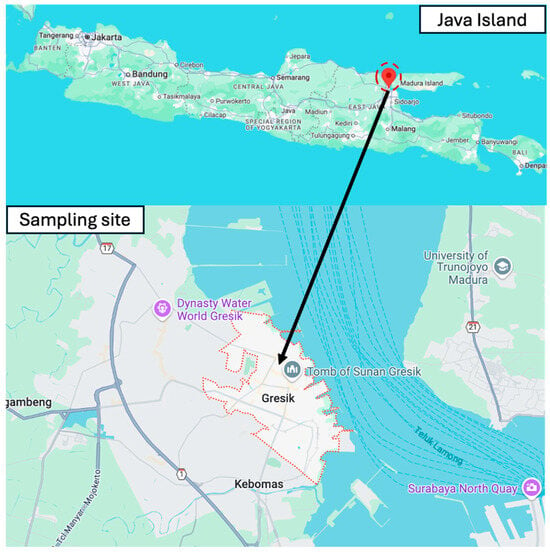

These five industries were selected to capture a diverse representation of ceramic manufacturing environments in Indonesia, encompassing various scales of production, company histories, and specializations in product design. The study population consisted of 234 workers, with 50 participants each from Industries A, B, and C, 48 from Industry D, and 36 from Industry E. Participants were selected from multiple job categories, including production, logistics, and administrative roles, to ensure coverage of different occupational environments and potential exposure scenarios. Selection prioritized workers involved in the production process, as these tasks typically involve direct or indirect exposure to dust, PM2.5, and crystalline silica particles. Demographic information, including age, gender, years of employment, and lifestyle factors, was also collected to analyze how these variables may influence exposure levels and health outcomes. Given that personal exposure measurements are resource-intensive and require worker cooperation during normal duties, this sample size is considered substantial and sufficient for reliable exposure characterization, in line with comparable occupational exposure studies. The details of the sampling area are displayed in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

Sampling location in Gresik city, East Java, Indonesia.

2.2. PM2.5 Exposure Sampling and C-Silica Component Analysis

As described in Section 2.1, personal exposure to PM2.5 and its crystalline silica (c-silica) component was assessed in five different ceramic industries. Personal air sampling was conducted within the breathing zones of workers using a 37 mm aluminum cyclone (Zefon International, Inc., Ocala, FL, USA; Ref. ZA0060) connected to a Gilian BDX II personal sampling pump (Sensidyne, USA), which separated coarser particles before allowing respirable dust (PM2.5) to be collected on the filter holder. A 37 mm polyvinyl chloride (PVC) filter was used, and the pump was operated at a flow rate of 2.5 L/min. Each worker wore a sampler for approximately 6–7 h, which represented the actual working period during dust-generating production activities, while also minimizing discomfort and avoiding excessive pump load, which also reduced the risk of filter clogging. Although slightly shorter than a full 8 h shift, this duration effectively captured exposure during dust-intensive tasks.

To ensure data quality, strict quality assurance and quality control (QA/QC) procedures were applied. Filters were equilibrated for 24 h in a desiccator under controlled conditions (temperature: 24–25 °C; relative humidity: 50–60%) prior to pre- and post-weighing using an analytical balance routinely calibrated with certified weights. Sampling pumps were calibrated before and after sampling. Field blanks were collected during each sampling period to check for background contamination, and all handling was conducted in clean laboratory conditions using anti-static tweezers and sealed containers to minimize contamination and particle loss. These measures ensured the reliability and accuracy of exposure measurements.

Following sampling, the filters underwent a laboratory preparation process to isolate and quantify the silica content. The PVC filters were ashed for two hours until only residual ash remained. This ash was mixed with 2-propanol to create a solution with a final volume of 15 mL. The mixture was subjected to ultrasonic agitation using a JP-010S Digital Ultrasonic Cleaner, Skymen, Shenzhen, China (2 L, 40 kHz, 60 W) to ensure even dispersion and eliminate clumps. The solution was then filtered through a 25 mm silver membrane filter using a vacuum-assisted glass funnel. To maximize recovery, the funnel was rinsed several times with 2-propanol, keeping the total volume of the filtrate below 20 mL. The silver membrane filter was subsequently dried and mounted onto a sample holder for further analysis by X-ray diffraction (XRD).

For this study, the sampling and analysis of respirable crystalline silica followed the NIOSH 7500 method (2003). XRD analysis was conducted on a horizontal axis at a 2-theta angle range of 10–80° using specialized software (version 4.9, Panalytical, Almelo, The Netherlands). Results were reported both as percentages and as concentrations (µg/m3) of crystalline silica in the sampled air. This standardized approach allowed for accurate quantification of silica in PM2.5 and provided robust data on worker exposure across various occupational settings.

2.3. Health and Questionnaire Data

To assess the health impact of PM2.5 and c-silica exposure among ceramic industry workers, this study also utilized a structured questionnaire to collect data on individual characteristics, workplace behaviors, respiratory health symptoms, and previous medical history. The questionnaire was designed to cover a broad range of factors that could influence workers’ susceptibility to respiratory issues. Key variables included the distance from home to the workplace (measured in kilometers) and transportation method, as these could affect exposure levels during commuting. Mask usage habits were also documented to understand the extent of personal protective equipment (PPE). Demographic data, such as gender, age, education level, and work unit, were collected to capture a profile of the workforce.

Occupational history was a critical component, encompassing years of work duration, daily exposure hours, and details of any previous jobs that could contribute to cumulative dust exposure. The questionnaire also investigated smoking habits, including smoking status and duration in years, as smoking can exacerbate respiratory issues related to dust exposure. In terms of health history, workers were asked whether they had ever been diagnosed with tuberculosis, a condition that could make them more vulnerable to respiratory diseases caused by dust. Respiratory symptoms were thoroughly documented, with questions about the frequency of phlegm production, time required to clear phlegm, shortness of breath, chronic cough, and nausea. These symptoms are often associated with prolonged exposure to respirable dust and silica, particularly in occupational settings. This combination of self-reported data and medical history allows for a detailed analysis of the occupational health risks faced by ceramic industry workers in Indonesia, supporting the development of targeted interventions to mitigate respiratory health risks.

2.4. X-Ray Analysis and Risk Assessment of Silica

The risk assessment of silica exposure in this study focused on two primary indicators, i.e., Chronic Daily Intake (CDI) and Hazard Quotient (HQ), following established guidelines for evaluating non-carcinogenic risks associated with inhaled pollutants. CDI represents the average amount of a pollutant, such as silica dust, that a worker is exposed to over a given period. CDI is calculated to understand the potential long-term exposure of individuals based on concentration levels of the c-silica, inhalation rate, exposure frequency and duration, body weight, and time-averaged exposure. The formula for CDI was calculated following the U.S. EPA Risk Assessment Guidance [54,55,56]:

where

CDI = Chronic Daily Intake (mg/kg-day).

C = Concentration, exposure concentration of c-silica (mg/m3).

IR = Inhalation Rate, men aged 19–65 years = 15.2 m3/day and women aged 19–65 = 10.8 m3/day (ATSDR, 2005).

ET = Exposure Time (hours/day; 8 h/day).

EF = Exposure Frequency (days/year; 250 days/year working days).

ED = Exposure Duration (years; 20 years).

BW = Body Weight (kg), men aged 19–65 = 65 kg and women aged 19–65 = 55 kg.

Lifetime = 70 years, based on the average human lifespan.

AT = Averaging Time (days) or lifetime × 365 days = 25,550 days.

This calculation provides an estimate of the amount of silica inhaled daily, allowing for a thorough understanding of cumulative exposure over time. Accurate data on worker behavior, daily exposure duration, and body weight were utilized to ensure the reliability of the CDI values.

The Hazard Quotient (HQ) is used to assess the risk of non-carcinogenic health effects by comparing the CDI of silica to a reference concentration (Rfc). The HQ calculation is as follows [54]:

where

HQ = CDI/Rfc

CDI: Chronic Daily Intake calculated as above (mg/kg/day).

Rfc: Reference Concentration for silica exposure, derived from toxicological studies and regulatory guidelines, representing the safe exposure threshold for non-carcinogenic effects. For silica, the Rfc has been established by regulatory agencies such as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The Rfc for respirable crystalline silica is typically set at 0.00003 mg/m3. This value represents the maximum safe daily exposure level for silica inhalation, below which adverse non-carcinogenic health effects are unlikely to occur. An HQ value of less than 1 indicates that the exposure level is unlikely to result in adverse health effects, suggesting that silica intake is within acceptable limits. In contrast, an HQ value greater than 1 implies a potential health risk, as the intake exceeds the reference concentration. This highlights the need for implementing risk management measures to reduce silica exposure among workers. Additionally, chest X-rays were conducted by certified radiologists in accordance with standard occupational health protocols to assess the lung condition of each worker. The results were interpreted for abnormalities related to occupational exposure, and any findings were documented while maintaining medical confidentiality.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

The study followed strict ethical standards for conducting research involving human participants. Prior to participation, all workers provided informed consent, ensuring they were fully aware of the study’s purpose, procedures, and any potential risks involved. Confidentiality was strictly maintained by handling data in an anonymized format, protecting the personal information of all participants. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Health Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Public Health at Airlangga University, under approval number 33-KEPK. This approval confirmed that the research protocol complied with ethical standards for occupational health research, particularly with regard to the protection of human rights and welfare. The ethics committee carefully reviewed and approved the study, ensuring that all research activities were conducted in an ethically responsible manner.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Demographic Profile of the Workers in Five Ceramic Industries

The demographic characteristics of workers across five ceramic industries (Industries A–E) are summarized in Table 1, which provides insights into their commuting behavior, occupational settings, and health status. Common patterns emerge, such as the predominance of motorcycles as the main mode of transportation and the male-dominated workforce, with over 90% of workers being male. However, notable differences are observed in commuting distances, education levels, work experience, and reported health symptoms. Workers in Industries A and B primarily commute from long distances, with 20% in Industry A and 36% in Industry B traveling more than 20 km. In contrast, Industry E has a higher proportion of workers commuting shorter distances, particularly within the 2.1–5 km range (35.8%), while Industry D has the highest percentage (33.3%) of workers commuting 5.1–10 km. Motorcycles are the dominant form of transport across all industries, used by 91–100% of workers. The use of cars, bicycles, and walking is minimal and primarily observed in Industries C and E.

Table 1.

Worker distribution and characteristics by various categories across different groups (I–A to I–E).

The worker sample distribution (Industry A: 50, B: 50, C: 50, D: 48, E: 36) was based on worker availability and willingness, rather than proportional to total workforce size, as detailed in the methodology. While this approach may limit proportional representativeness, the number of participants per facility is substantial for occupational exposure studies.

Mask usage is generally low, with only 8 (Industry A), 19 (Industry B), 13 (Industry C), 10 (Industry D), and 7 (Industry E) workers reporting consistent use. This low compliance may result from poor enforcement or an underestimation of respiratory risks. The workforce is overwhelmingly male, with female workers numbering only 2 in Industry A, 4 in Industry C, 1 in Industry D, and 2 in Industry E; no female workers were recorded in Industry B. Age distribution varies: Industry A shows a relatively even age spread, while Industry D has a high proportion (48%) of workers aged 25.1–35 years. Industry C has a significant concentration (56%) of older workers aged 35.1–45 and over 45 years. In terms of education, most workers have completed high school. Industry B has the highest number of college-educated workers (27), while Industry C includes five workers with only elementary or junior high school education, suggesting more diverse hiring practices.

Production is the dominant work unit in all industries. Office and logistic roles are more represented in WS–A and WS–B. WS–D has the largest number of production workers (41). Regarding work experience, Industry C stands out with 43 workers having more than 10 years of service. Daily exposure of 7–8 h is the standard, reported by the majority of workers in all industries. Smoking prevalence is high in WS–A, WS–B, and WS–C, where more than 65% of workers are smokers. Long-term smoking (>10 years) is especially common in WS–C (30 workers). These lifestyle factors, including high smoking prevalence and inconsistent PPE use, are important confounders that may have amplified the prevalence of respiratory symptoms and should be considered when interpreting health outcomes.

Frequent phlegm was reported by 17 (WS–C) and 14 (WS–A) workers. Shortness of breath was less common but present, particularly in WS–C (6 workers). Reports of nausea and coughing were scattered, with WS–A being the highest for both symptoms. Despite the reported symptoms, most X-ray results were normal across all industries. However, abnormalities were noted in a few cases, including 3 workers in WS–C and WS–D each. Additionally, rare findings such as cardiomegaly (WS–C) and old fractures (WS–E) were recorded. It should also be noted that respiratory symptoms were based on self-reported questionnaires, which may be subject to recall bias, although chest X-ray findings provided some supportive evidence.

3.2. PM2.5 and Airborne Silica Concentrations in Different Job Roles Across Industries

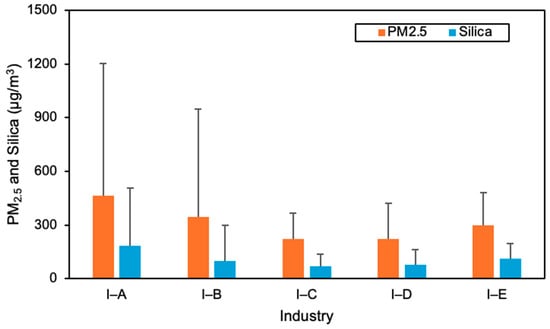

The PM2.5 and airborne c-silica concentrations across five ceramic industries reveals significant variability based on job roles and work environments as can be seen in Figure 2 and Table 2, Table 3 and Table S1. Workers in production roles consistently experience the highest exposure levels to PM2.5 and c-silica, underscoring the occupational risks associated with dust-generating tasks such as cutting, grinding, and handling raw materials [57,58,59]. For example, in Industry B, PM2.5 concentrations in production areas peak at 4152.4 µg/m3 (W7), while Industry A also shows notably high levels of 3243.2 µg/m3 (W25). These values significantly exceed permissible exposure limits and highlight the need for rigorous dust control measures. Similarly, silica concentrations in production roles often exceed 1000 µg/m3, posing severe health risks, including silicosis and long-term respiratory illnesses [60,61]. Although some industries had already implemented dust control strategies such as wet mixing and localized ventilation, the consistently high exposure levels indicate that existing systems were insufficient to reduce concentrations to safe levels.

Figure 2.

Average of PM2.5 and c-silica component in five ceramics industry in Surabaya, East Java, Indonesia.

Table 2.

PM2.5 and c-silica component in five ceramics industries in Gresik, East Java, Indonesia.

Table 3.

Average PM2.5 and c-silica component in five ceramics industry in Gresik, East Java, Indonesia.

While production workers face the most severe exposure, logistics and warehouse workers also encounter moderate PM2.5 and silica levels. In Industry B, logistics workers record PM2.5 concentrations exceeding 1000 µg/m3, which can be attributed to proximity to production zones or the handling of dusty materials. Similarly, warehouse workers in Industries C and D experience notable PM2.5 levels, suggesting the migration of PM from production areas into adjacent spaces. These findings emphasize the importance of isolating production zones and implementing air containment strategies, such as air curtains or localized ventilation systems, to reduce secondary exposure risks.

In contrast, office workers across all industries exhibit significantly lower exposure levels, highlighting the effectiveness of physical separation and ventilation in administrative areas. For instance, in Industry A, PM2.5 levels for office workers are as low as 53.3 (W8) µg/m3, a significant contrast to production areas. Similarly, in Industry E, office environments maintain low concentrations of silica (29.0 µg/m3), indicating the benefits of spatial segregation in mitigating occupational hazards.

The variability of PM2.5 and silica exposure within production roles across industries suggests inconsistent application of dust control measures or task-specific differences in dust generation. For example, in Industry C, production workers’ PM2.5 levels range widely, potentially due to variations in equipment and operational processes. Industries with highly concentrated exposures require targeted interventions, such as local exhaust ventilation and routine monitoring, to address these disparities effectively. It should also be noted that all values reported here reflect 6–7 h of active production periods, consistent with the sampling duration, and were not extrapolated to full 8 h time-weighted averages.

An interesting trend in Industry D shows that even roles traditionally removed from production, such as logistics and warehouse positions, encounter moderate PM2.5 exposure. This indicates inadequate containment of dust within production areas. Improved enclosures and dust suppression systems are necessary to limit particulate matter spread and protect non-production workers. Meanwhile, security and laboratory roles generally experience low exposure levels, reflecting their physical distance from production activities.

Mask usage remains inconsistent across industries, particularly among production workers, who are most vulnerable to high exposure levels. For example, in Industry B, despite extreme PM2.5 levels, many workers do not consistently wear masks. This indicates a need for stricter enforcement of PPE policies, alongside engineering and administrative controls. Consistent mask usage, coupled with localized exhaust systems and dust suppression, can significantly reduce exposure levels for high-risk roles.

3.3. Comparison to Other Studies

The concentrations of respirable PM and c-silica observed in this study align with, and in some cases exceed, those reported in other occupational environments worldwide, as summarized in Table 4. In the current study, PM2.5 concentrations in production areas reached up to 4152.4 µg/m3 (I-B), while airborne c-silica levels were observed as high as 1400 µg/m3 (I-A). These levels are considerably elevated when compared to several global benchmarks.

For example, respirable dust levels of 800 µg/m3 and c-silica of 60 µg/m3 were reported in the concrete industry in the Netherlands [62]. In Iran, PM concentrations of 2040 µg/m3 and c-silica of 70 µg/m3 were found in foundries [63]. In Kermanshah, Iran, respirable dust ranged from 1770 to 6120 µg/m3 and c-silica concentrations between 26 and 44 µg/m3 in cement factories [64]. These values are generally lower than those documented in the present study, especially for c-silica.

A particularly high silica exposure was reported in Egypt’s ceramic industry, with concentrations reaching 510 µg/m3 [65]. This value is higher than the average c-silica concentrations observed across all factories in the present study (98–347.3 µg/m3), but still lower than the maximum levels recorded in Industries A and B, which reached up to 1395 and 1391 µg/m3, respectively. In the construction and mining sectors, lower average silica concentrations were reported across various activities in Alberta, ranging from 7 to 90 µg/m3 [66]. Similar patterns of moderate exposure were observed in Turkey (450 µg/m3) among tile and ceramic workers, India (120–170 µg/m3) in stone mines, and Mongolia (12 µg/m3) in copper mining operations. Overall, PM2.5 and c-silica concentrations in the five ceramic industries in Indonesia tend to be higher than those reported in various industries worldwide, particularly among production workers.

Table 4.

Comparison of PM and c-silica components with previous studies worldwide.

Table 4.

Comparison of PM and c-silica components with previous studies worldwide.

| No. | Author | Location/Country | Industry | PM Concentration/Respirable Dust (µg/m3) | C-Silica (µg/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Meijer et al., (2001) [62] | The Netherlands | Concrete Industry | 800 | 60 |

| 2 | Radnoff et al., (2014) [66] | Alberta | Sand and Mineral Processing | 90 | |

| New Construction | 55 | ||||

| Aggregate Mining and crushing | 48 | ||||

| Abrasive Blasting | 27 | ||||

| Demolition | 27 | ||||

| Oil and Gas | 24 | ||||

| Foundry | 20 | ||||

| Manufacturing | 20 | ||||

| Mining | 17 | ||||

| Asphalt Plant | 16 | ||||

| Earth Moving/ Road Building | 13 | ||||

| Cement Plant | 10 | ||||

| Limestone Quarry | 7 | ||||

| 3 | Omidianidost et al., (2015) [63] | Iran | Foundries | 2040 | 70 |

| 4 | Mohamed et al., (2018) [65] | Egypt | Ceramic industry | 10,000 | 510 |

| 5 | Omidianidost et al., (2019) [64] | Kermanshah, Iran | Cement Factory | 1770–6120 | 26–44 |

| 6 | Salamon et al., (2021) [13] | Northern Italy | Artificial stone processing | 46–1154 | <3–98 |

| 7 | Surasi et al., (2022) [67] | California | Stone fabrication | 89 | |

| 8 | Tavakol et al., (2017) [68] | Iran | Construction workers | 8900 | 130 |

| 9 | Otgonnasan et al., (2022) [69] | Mongolia | Copper mine | 350 | 12 |

| 10 | Nourmohammadi et al., 2022 [70] | Turkey | Tile and ceramic workers | 450 | |

| 11 | Prajapati et al., (2020) [71] | India | Stone mines | 370–3280 | 120–170 |

| 12 | Prajapati et al., (2021) [72] | India | Mining sectors | 920–1070 | 15–80 |

3.4. Risk Assessment of C-Silica Component for the Worker

The health risk assessment of PM2.5 and c-silica across five ceramic industries (A–E) highlights substantial variability in exposure and associated non-carcinogenic health risks among workers. Detailed exposure and risk data for each worker and industry are provided in Table 5 and Tables S2–S6. The analysis, based on CDI, HQ, and RQ, indicates that production workers consistently face the highest exposure levels due to direct involvement in dust-generating processes such as material handling, grinding, and mixing. Industry A demonstrated the highest maximum HQ (76.25) and RQ (48.56), although its average CDI for PM2.5 and c-silica was 0.0069 and 0.0030 mg/kg/day, respectively. This suggests a concentration of high-risk exposure in specific job roles. Industry C followed with the highest average HQ (8.14) and RQ (4.41), and maxima of 38.58 and 33.23, indicating widespread but variable exposure even at moderate average CDI levels.

Table 5.

Statistical measures or average, minimum, and maximum of CDI, HQ, and RQ PM2.5 and its c-silica component in each workshop.

Industry B recorded the lowest average CDI (0.0021 for PM2.5 and 0.0006 for c-silica), with correspondingly lower average HQ (1.49) and RQ (0.70). Nonetheless, certain workers still exceeded the acceptable risk threshold (HQ/RQ > 1), suggesting that risk is not uniformly distributed across roles. Industry D presented moderate average HQ (2.59) and RQ (1.44), with peaks up to 11.98 and 9.60, emphasizing the need for localized controls. Although Industry E had a low average CDI for c-silica (0.0028), its maximum RQ reached 17.33, again pointing to task-specific exposure spikes. Overall, the data indicate that production zones are the primary risk areas, but dust migration also affects logistics and adjacent roles. Inconsistent use of PPE as explained in Section 3.1, further exacerbates exposure risks.

3.5. Recommendations and Limitations

The findings of this study indicate elevated occupational exposure to PM2.5 and crystalline silica, particularly among production workers, underscoring the urgent need for targeted control measures. Based on both the results of this research and evidence from similar high-exposure industries such as mining, foundries, and construction [73,74,75], effective strategies include installing local exhaust ventilation [76,77,78], enclosing dust-generating processes [79,80], implementing job rotation, and maintaining regular cleaning to prevent dust accumulation. Consistent use of certified respirators (e.g., N95 or higher) and routine health surveillance, including lung function tests and chest imaging, are also critical. Increasing worker awareness through targeted training can further improve compliance and enhance the effectiveness of these measures.

This study has several limitations. First, exact total workforce numbers for each facility were not available, which limited our ability to quantitatively assess the representativeness of the sample. However, the number of workers included per facility (n = 36–50) is substantial for personal exposure studies and covered multiple job categories, providing a reasonable reflection of workplace exposure conditions. Second, measurements were conducted during a single monitoring period for each worker, which may not capture seasonal or day-to-day variability in dust concentrations. Third, this study did not include simultaneous ambient workplace or outdoor measurements, which limits the ability to distinguish workplace-related exposures from background pollution. Fourth, the study did not perform dose–response modeling, and therefore health implications were discussed qualitatively using CDI, HQ, and RQ metrics. Finally, while we included both PM2.5 and crystalline silica, other potentially harmful airborne contaminants in ceramic production were not assessed.

4. Conclusions

Occupational exposure to respirable PM2.5 and crystalline silica is a critical health concern in the ceramic industry, where dust-generating processes are integral to production. This study assessed exposure levels among workers in five ceramic industries in Indonesia using personal air sampling combined with health risk assessment methods (CDI, HQ, and RQ) and worker questionnaires. The results revealed significant variability in exposure across job roles and industries. Production workers consistently experienced the highest exposure, with PM2.5 concentrations reaching up to 4152.4 µg/m3 (Industry B) and crystalline silica levels exceeding 1000 µg/m3 in several production zones—values that surpass recommended occupational limits. Risk assessment confirmed elevated health risks, with Industry A showing the highest individual HQ (76.25) and RQ (48.56), and Industry C recording the highest average HQ (8.14) and RQ (4.41). Even in Industry B, where average values were lowest, some workers exceeded acceptable thresholds, indicating localized high-risk conditions. Demographic analysis highlighted long daily exposure durations (7–8 h), high smoking prevalence, and low PPE compliance, especially in Industries A–C. Respiratory symptoms such as phlegm, coughing, and breathlessness were common, while chest X-ray findings in some workers suggested possible early signs of occupational lung impacts. These findings underscore the need for effective control measures, including engineering interventions, administrative policies, and improved PPE use, to mitigate exposure risks. The study contributes valuable data to understanding the occupational health burden in Indonesia’s ceramic sector.

This work has several limitations. Exact workforce sizes in each facility were unavailable, restricting assessment of sample proportionality. Measurements reflected single-shift sampling periods of 6–7 h rather than full-shift averages, and validation of self-reported health symptoms was limited. Ambient air monitoring was not conducted, preventing a distinction between workplace and background exposures. Future research should aim for multi-season sampling, full-shift monitoring, larger datasets with complete workforce profiles, and inclusion of other potentially harmful airborne contaminants to better capture long-term risks and guide effective prevention strategies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/atmos16101125/s1: Table S1. Average PM2.5, c-silica component and working units in five ceramics industry in Gresik, East Java, Indonesia. Table S2. Health risk assessment based on CDI, HQ and RQ of PM2.5 and c-silica Industry-A. Table S3. Health risk assessment based on CDI, HQ and RQ of PM2.5 and c-silica Industry-B. Table S4. Health risk assessment based on CDI, HQ and RQ of PM2.5 and c-silica Industry-C. Table S5. Health risk assessment based on CDI, HQ and RQ of PM2.5 and c-silica Industry-D. Table S6. Health risk assessment based on CDI, HQ and RQ of PM2.5 and c-silica Industry-A.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.; methodology, M.S.; validation, M.S. and M.A.; formal analysis, M.S. and M.A.; investigation, M.S.; resources, M.S.; data curation, M.S. and M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.; writing—review and editing, M.A., S.Y.A. and F.J.; visualization, M.A.; project administration, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Health Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Public Health at Airlangga University, under approval number 33-KEPK. This approval confirmed that the research protocol complied with ethical standards for occupational health research, particularly with regard to the protection of human rights and welfare. The ethics committee carefully reviewed and approved the study, ensuring that all research activities were conducted in an ethically responsible manner.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to all five ceramic industries in Gresik, East Java, for granting access and supporting the sampling activities throughout this study. We are also deeply thankful to all the workers who willingly participated and wore the personal samplers, making this research possible. Their cooperation and contribution are greatly appreciated.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Agrafiotis, C.; Tsoutsos, T. Energy saving technologies in the European ceramic sector: A systematic review. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2001, 21, 1231–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furszyfer Del Rio, D.D.; Sovacool, B.K.; Foley, A.M.; Griffiths, S.; Bazilian, M.; Kim, J.; Rooney, D. Decarbonizing the ceramics industry: A systematic and critical review of policy options, developments and sociotechnical systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 157, 112081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaiani, L.; Boccaccio, A.; Uva, A.E.; Palumbo, G.; Piccininni, A.; Guglielmi, P.; Cantore, S.; Santacroce, L.; Charitos, I.A.; Ballini, A. Ceramic Materials for Biomedical Applications: An Overview on Properties and Fabrication Processes. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randhawa, K.S. A state-of-the-art review on advanced ceramic materials: Fabrication, characteristics, applications, and wettability. Pigment. Resin. Technol. 2023, 53, 768–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.J.; Tulyaganov, D. Traditional Ceramics Manufacturing. In Ceramics, Glass and Glass-Ceramics; PoliTO Springer Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 75–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwueke, T.C.; Okonkwo, I. Clay Essential Material For Ceramic Production. Environ. Rev. 2024, 9, 107–117. [Google Scholar]

- Mezquita, A.; Monfort, E.; Ferrer, S.; Gabaldón-Estevan, D. How to reduce energy and water consumption in the preparation of raw materials for ceramic tile manufacturing: Dry versus wet route. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 1566–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merget, R.; Bauer, T.; Küpper, H.; Philippou, S.; Bauer, H.; Breitstadt, R.; Bruening, T. Health hazards due to the inhalation of amorphous silica. Arch. Toxicol. 2002, 75, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poinen-Rughooputh, S.; Rughooputh, M.S.; Guo, Y.; Rong, Y.; Chen, W. Occupational exposure to silica dust and risk of lung cancer: An updated meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanka, K.S.; Shukla, S.; Gomez, H.M.; James, C.; Palanisami, T.; Williams, K.; Chambers, D.C.; Britton, W.J.; Ilic, D.; Hansbro, P.M.; et al. Understanding the pathogenesis of occupational coal and silica dust-associated lung disease. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2022, 31, 210250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy, R.F.; Chambers, D.C. Silica-related diseases in the modern world. Allergy Eur. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 75, 2805–2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, P.A.; Bartley, D.L.; Key-Schwartz, R.J.; Rice, F.L.; Schlecht, P.C. Health Effects of Occupational Exposure to Respirable Crystalline Silica; NIOSH: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamon, F.; Martinelli, A.; Vianello, L.; Bizzotto, R.; Gottardo, O.; Guarnieri, G.; Franceschi, A.; Porru, S.; Cena, L.; Carrieri, M. Occupational exposure to crystalline silica in artificial stone processing. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2021, 18, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilabert, J.; Díaz-Canales, E.M.; Zumaquero, E.; Gazulla, M.F.; Blasco, E.; Gómez-Tena, M.P. Development of tridymite structure studied through crystal growth by X-ray diffraction: Influence of synthesis parameters. Boletín Soc. Española Cerámica Vidr. 2025, 64, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.P.; Harrison, P.T.C. Crystalline silica in heated man-made vitreous fibres: A review. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2014, 68, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, C.; Conte, S.; Dondi, M.; Zanelli, C. Content of crystalline silica phases in porcelain stoneware. Open Ceram. 2024, 19, 100650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castranova, V.; Vallyathan, V. Silicosis and coal workers’ pneumoconiosis. Environ. Health Perspect. 2000, 108, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.P.; Rushton, L. Mortality in the UK industrial silica sand industry: 2. A retrospective cohort study. Occup. Environ. Med. 2005, 62, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández García, L.C.; Monteiro, S.N.; Lopera, H.A.C. Recycling Clay Waste from Excavation, Demolition, and Construction: Trends and Challenges. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundt, K.A.; Thompson, W.J.; Dhawan, G.; Checkoway, H.; Boffetta, P. Systematic review of the epidemiological evidence of associations between quantified occupational exposure to respirable crystalline silica and the risk of silicosis and lung cancer. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1554006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuletaw, A.; Mihret, B. Physicochemical and mineralogical characterization of silica sand from the Lemi region, Blue Nile Basin, central Ethiopia: Evaluating industrial applications and resource potential. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, A.; Li, R.; Chen, G.; Chen, S. Impact of Respiratory Dust on Health: A Comparison Based on the Toxicity of PM2.5, Silica, and Nanosilica. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, C.; Song, Y.; Yen, S.; Southam, K.; Page, S.; Pisaniello, D.; Gaskin, S.; Zosky, G.R. Understanding the pathogenesis of engineered stone-associated silicosis: The effect of particle chemistry on the lung cell response. Respirology 2024, 29, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, A.I.; Shaheen, R.; Naveed, N.H.; Tabassum, T.; Rehman, M.F.U.; Naz, S.; Habib, S.S.; Mohany, M. Silica dust exposure and associated pulmonary dysfunction among mine workers. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part A 2025, 60, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, M. Does the current occupational exposure limit effectively prevent the risk of silicosis? Thorax 2025, 80, 408–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazio, J.C.; Viragh, K.; Houlroyd, J.; Gandhi, S.A. A review of silicosis and other silica-related diseases in the engineered stone countertop processing industry. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2025, 20, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Fu, P.; Wang, S.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, X. Occupational exposure to silica and risk of gastrointestinal cancers: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2024, 97, 231–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, P.; Gan, J.; Lesosky, M.; Feary, J. Relationship between cumulative silica exposure and silicosis: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Thorax 2024, 79, 934–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suma’mur, P.K. Higiene Perusahaan dan Kesehatan Kerja (Hiperkes), 2nd ed.; Sagung Seto: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- IARC. Silica, Some Silicates, Coal Dust and para-Aramid Fibrils. IARC Monogr. Eval. Carcinog. Risks Hum. 1997, 68, 1–475. [Google Scholar]

- Min, L.; Mao, Y.; Lai, H. Burden of silica-attributed pneumoconiosis and tracheal, bronchus & lung cancer for global and countries in the national program for the elimination of silicosis, 1990–2019: A comparative study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cite: Mishra, A.K.; Baniya, A. Establishing Effective Dust Exposure Limits in Nepal: A Global Imperative for Worker Safety and Health. J. UTEC Eng. Manag. 2024, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondayo, M.A.; Watts, M.J.; Mitchell, C.J.; King, D.C.P.; Osano, O. Review: Artisanal Gold Mining in Africa—Environmental Pollution and Human Health Implications. Expo. Health 2023, 16, 1067–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Kurmi, O.P.; Hariprasad, P.; Tyagi, S.K. Health implications due to exposure to fine and ultra-fine particulate matters: A short review. Int. J. Ambient Energy 2024, 45, 2314256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beigoli, S.; Amin, F.; Kazemi Rad, H.; Rezaee, R.; Boskabady, M.H. Occupational respiratory disorders in Iran: A review of prevalence and inducers. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1310040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morin, L.; Lecureur, V.; Lescoat, A. Results from omic approaches in rat or mouse models exposed to inhaled crystalline silica: A systematic review. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2024, 21, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Hnizdo, E.; Sun, Y.; Su, L.; Zhang, X.; Weng, S.; Bochmann, F.; Hearl, F.J.; et al. Long-term exposure to silica dust and risk of total and cause-specific mortality in Chinese workers: A cohort study. PLoS Med. 2012, 9, e1001206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurzu, I.L.; Handra, C.M.; Ghita, I.; Otelea, M.R. Unveiling the threat of crystalline silica on the cardiovascular system. A comprehensive review of the current knowledge. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 12, 1506846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qingsong, M.; Xiao, R.; Yang, W.; Wang, X.; Kong, Y.Z. Global burden of pneumoconiosis attributable to occupational particulate matter, gasses, and fumes from 1990~2021 and forecasting the future trends: A population-based study. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1494942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Li, C.; Zhou, S.; Li, C.; Meng, F.; Wang, X.; Xu, Q.; Liu, H.; Tang, Y. Pneumoconiosis and Chronic Diseases: A Narrative Review. Iran. J. Public Health 2025, 54, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Lin, J.; Xiang, J. Effects of occupational dust exposure on the health status of workers in China. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jutzi, P.; Schubert, U. Silicon Chemistry: From the Atom to Extended Systems; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; 494p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellamuthu, R.; Umbright, C.; Li, S.; Kashon, M.; Joseph, P. Mechanisms of crystalline silica-induced pulmonary toxicity revealed by global gene expression profiling. Inhal. Toxicol. 2011, 23, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Başaran, N.; Shubair, M.; Ündeǧer, Ü.; Canpinar, H.; Kars, A. Alterations in immune parameters in foundry and pottery workers. Toxicology 2002, 178, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teku, D. Geo-environmental and socio-economic impacts of artisanal and small-scale mining in Ethiopia: Challenges, opportunities, and sustainable solutions. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1505202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanto, A.D. Pneumokoniosis. J. Indones. Med. Assoc. 2011, 61, 503–511. [Google Scholar]

- Akbar, J. Kadar Serum Nephronectin (Npnt) Berdasarkan Lama Panjanan Debu Silika Pada Pekerja Industri Marmer Tugas Akhir Penelitian; Universitas Brawijaya: Malang, Indonesia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ofori, S.A.; Dwomoh, J.; Yeboah, E.O.; Martin, A.L.; Nti, S.; Philip, A.; Asante, C. A ecological study of galamsey activities in Ghana and their physiological toxicity. Asian J. Toxicol. Environ. Occup. Health 2024, 2, 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, A.J.; Mundt, K.A.; Maier, A. Risk characterization for silica-related silicosis and lung cancer in communities adjacent to sand and gravel extraction facilities: Examining limitations in our current risk methods. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1558778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kreiss, K.; Zhen, B. Risk of silicosis in a colorado mining community. Am. J. Ind. Med. 1996, 30, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenland, K.; Brown, D. Silicosis among gold miners: Exposure-response analyses and risk assessment. Am. J. Public Health 1995, 85, 1372–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OSHA. Occupational Exposure to Respirable Crystalline Silica—Review of Health Effects Literature and Preliminary Quantitative Risk Assessment; Docket OSHA’ 2010; Occupational Safety and Health Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; Volume 34, p. 483.

- Ministry of Manpower of the Republic of Indonesia. PER.05/MEN/2018; Peraturan Menteri Ketenagakerjaan Republik Indonesia tentang Batas Ambang Faktor Fisika dan Faktor Kimia di Tempat Kerja; Ministry of Manpower: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2018.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). Risk Assessment Guidance for Superfund (RAGS), Volume I: Human Health Evaluation Manual (Part A) (EPA/540/1-89/002); Office of Emergency and Remedial Response: Washington, DC, USA, 1989.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). Risk Assessment Guidance for Superfund (RAGS), Volume I: Human Health Evaluation Manual (Part F, Supplemental Guidance for Inhalation Risk Assessment) (EPA-540-R-070-002); Office of Superfund Remediation and Technology Innovation: Washington, DC, USA, 2009.

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). Toxicological Profile for Silica; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2005.

- Akbar-khanzadeh, F.; Milz, S.A.; Wagner, C.D.; Bisesi, M.S.; Ames, A.; Khuder, S.A.; Susi, P.; Akbar-Khanzadeh, M. Effectiveness of Dust Control Methods for Crystalline Silica and Respirable Suspended Particulate Matter Exposure During Manual Concrete Surface Grinding. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2010, 7, 700–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, S.; Woskie, S.R.; Holcroft, C.A.; Ellenbecker, M.J. Reducing Silica and Dust Exposures in Construction During Use of Powered Concrete-Cutting Hand Tools: Efficacy of Local Exhaust Ventilation on Hammer Drills. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2008, 6, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.; Hwang, E.; Yoon, C. Respirable Crystalline Silica Exposure among Concrete Finishing Workers at Apartment Complex Construction Sites. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2019, 19, 2804–2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keramydas, D.; Bakakos, P.; Alchanatis, M.; Papalexis, P.; Konstantakopoulos, I.; Tavernaraki, K.; Dracopoulos, V.; Papadakis, A.; Pantazi, E.; Chelidonis, G.; et al. Investigation of the health effects on workers exposed to respirable crystalline silica during outdoor and underground construction projects. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 20, 882–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Singh, R.K.; Singh, K.K.; Singh, S.R. Concentration, sources and health effects of silica in ambient respirable dust of Jharia Coalfields Region, India. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2022, 34, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, E.; Kromhout, H.; Heederik, D. Respiratory effects of exposure to low levels of concrete dust containing crystalline silica. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2001, 40, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidianidost, A.; Ghasemkhani, M.; Azari, M.R.; Golbabaei, F. Assessment of Occupational Exposure to Dust and Crystalline Silica in Foundries. Tanaffos 2015, 14, 208. [Google Scholar]

- Omidianidost, A.; Gharavandi, S.; Azari, M.R.; Hashemian, A.H.; Ghasemkhani, M.; Rajati, F.; Jabari, M. Occupational Exposure to Respirable Dust, Crystalline Silica and Its Pulmonary Effects among Workers of a Cement Factory in Kermanshah, Iran. Tanaffos 2019, 18, 157. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, S.H.; El-ansary, A.L.; El-Aziz, E.M.A. Determination of crystalline silica in respirable dust upon occupational exposure for Egyptian workers. Ind. Health 2018, 56, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radnoff, D.; Todor, M.S.; Beach, J. Occupational exposure to crystalline silica at Alberta work sites. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2014, 11, 557–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surasi, K.; Ballen, B.; Weinberg, J.L.; Materna, B.L.; Harrison, R.; Cummings, K.J.; Heinzerling, A. Elevated exposures to respirable crystalline silica among engineered stone fabrication workers in California, January 2019–February 2020. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2022, 65, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, E.; Azari, M.; Zendehdel, R.; Salehpour, S.; Khodakrim, S.; Nikoo, S.; Saranjam, B. Risk evaluation of construction workers’ exposure to silica dust and the possible lung function impairments. Tanaffos 2017, 16, 295–303. [Google Scholar]

- Otgonnasan, A.; Yundendorj, G.; Tsogtbayar, O.; Erdenechimeg, Z.; Ganbold, T.; Namsrai, T.; Damiran, N.; Erdenebayar, E. Respirable dust and respirable crystalline silica concentration in workers of copper mine, Mongolia. Occup. Dis. Environ. Med. 2022, 10, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourmohammadi, M.; Yari, S.; Rahimimoghadam, S. Effect of occupational exposure to crystalline silica on pulmonary indices in tile and ceramic workers. Asian Pac. J. Environ. Cancer 2022, 5, 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Prajapati, S.S.; Nandi, S.S.; Deshmukh, A.; Dhatrak, S.V. Exposure profile of respirable crystalline silica in stone mines in India. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2020, 17, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prajapati, S.S.; Mishra, R.A.; Jhariya, B.; Dhatrak, S.V. Respirable dust and crystalline silica exposure among different mining sectors in India. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health 2021, 76, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahmann, D.; Taeger, D.; Kappler, M.; Büchte, S.; Morfeld, P.; Brüning, T.; Pesch, B. Assessment of exposure in epidemiological studies: The example of silica dust. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2008, 18, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, D.; Leng, P.; Li, X.; Mao, G.; Wang, A.; Zhang, D. Characteristics and occupational risk assessment of occupational silica-dust and noise exposure in ferrous metal foundries in Ningbo, China. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1049111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudry, C.; Lavoué, J.; Sauvé, J.-F.; Bégin, D.; Rhazi, M.S.; Perrault, G.; Dion, C.; Gérin, M. Occupational exposure to silica in construction workers: A literature-based exposure database. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2013, 10, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, M.; Seixas, N.; Majar, M.; Camp, J.; Morgan, M. Silica Dust Exposures During Selected Construction Activities. AIHA J. 2003, 64, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A.; Jones, E.; Echt, A.S.; Hall, R.M. An evaluation of an aftermarket local exhaust ventilation device for suppressing respirable dust and respirable crystalline silica dust from powered saws. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2014, 11, D200–D207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morteza, M.M.; Hossein, K.; Amirhossein, M.; Naser, H.; Gholamhossein, H.; Hossein, F. Designing, construction, assessment, and efficiency of local exhaust ventilation in controlling crystalline silica dust and particles, and formaldehyde in a foundry. SciendoCom 2013, 64, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, M.R.; Susi, P. Engineering Controls for Selected Silica and Dust Exposures in the Construction Industry—A Review. Appl. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2003, 18, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkonen, A.; Linnainmaa, M.; Säämänen, A.; Kanerva, T.; Sorvari, J.; Kolehmainen, M.; Lappalainen, V.; Pasanen, P. Control of Dust Dispersion From an Enclosed Renovation Site Into Adjacent Areas by Using Local Exhaust Ventilation. Ann. Work Expo. Health 2019, 63, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).