Oxidation of Aminoacetaldehyde Initiated by the OH Radical: A Theoretical Mechanistic and Kinetic Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

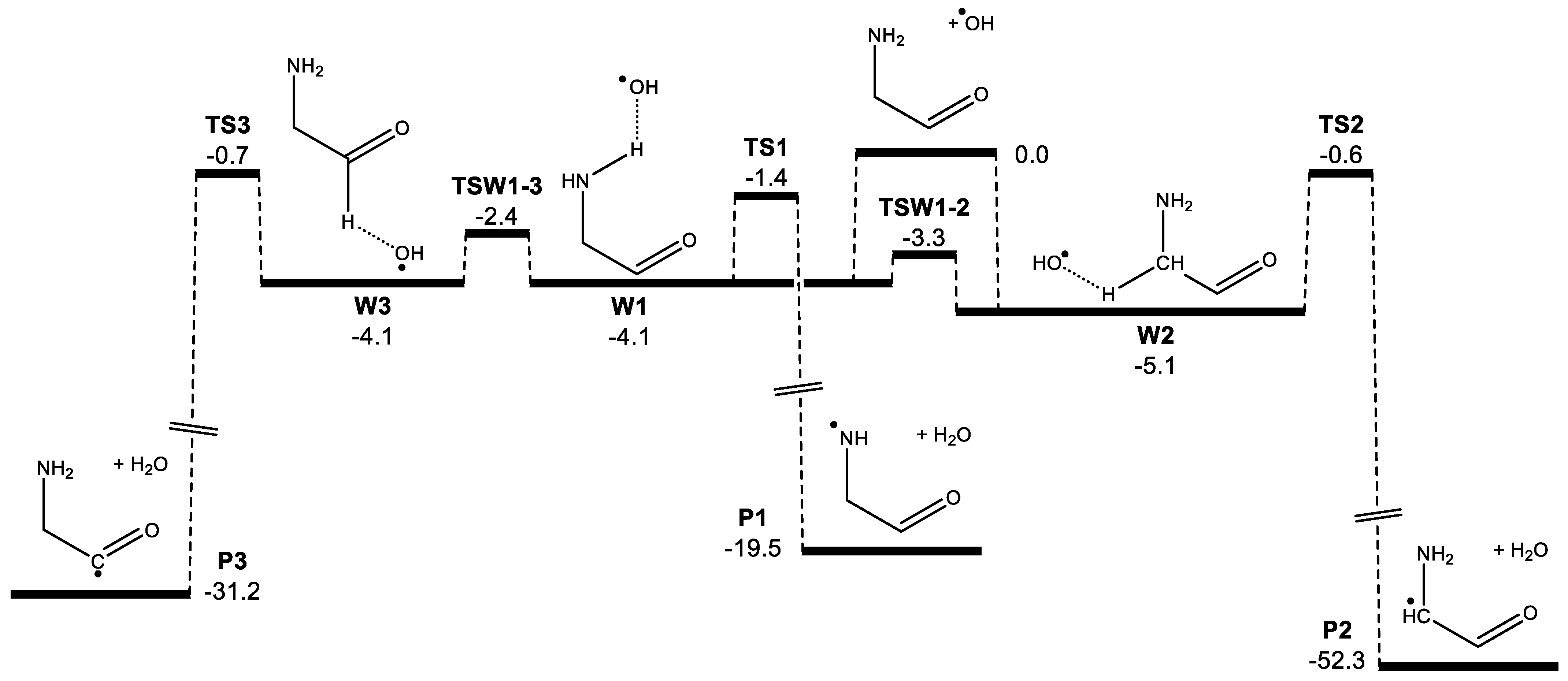

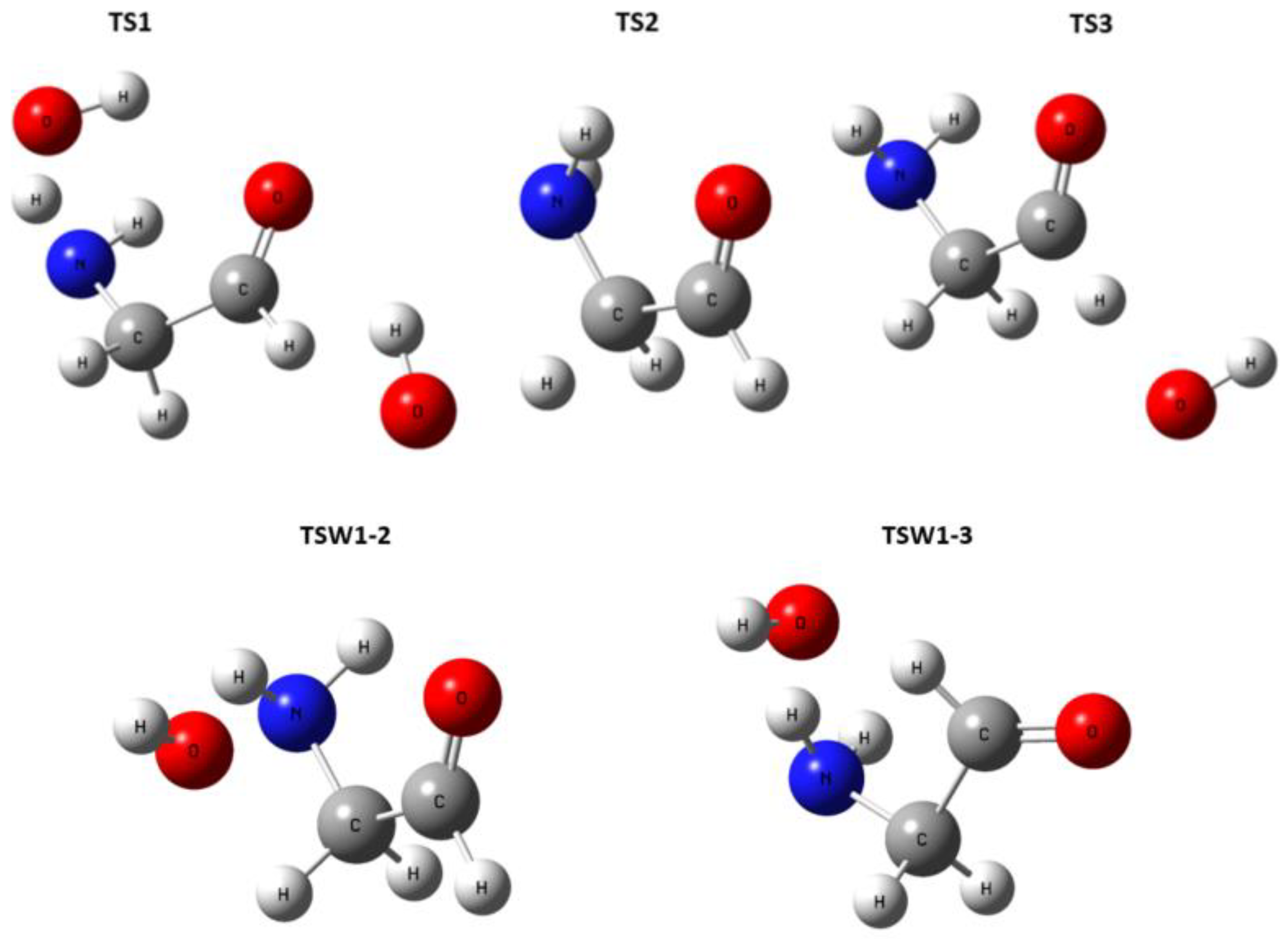

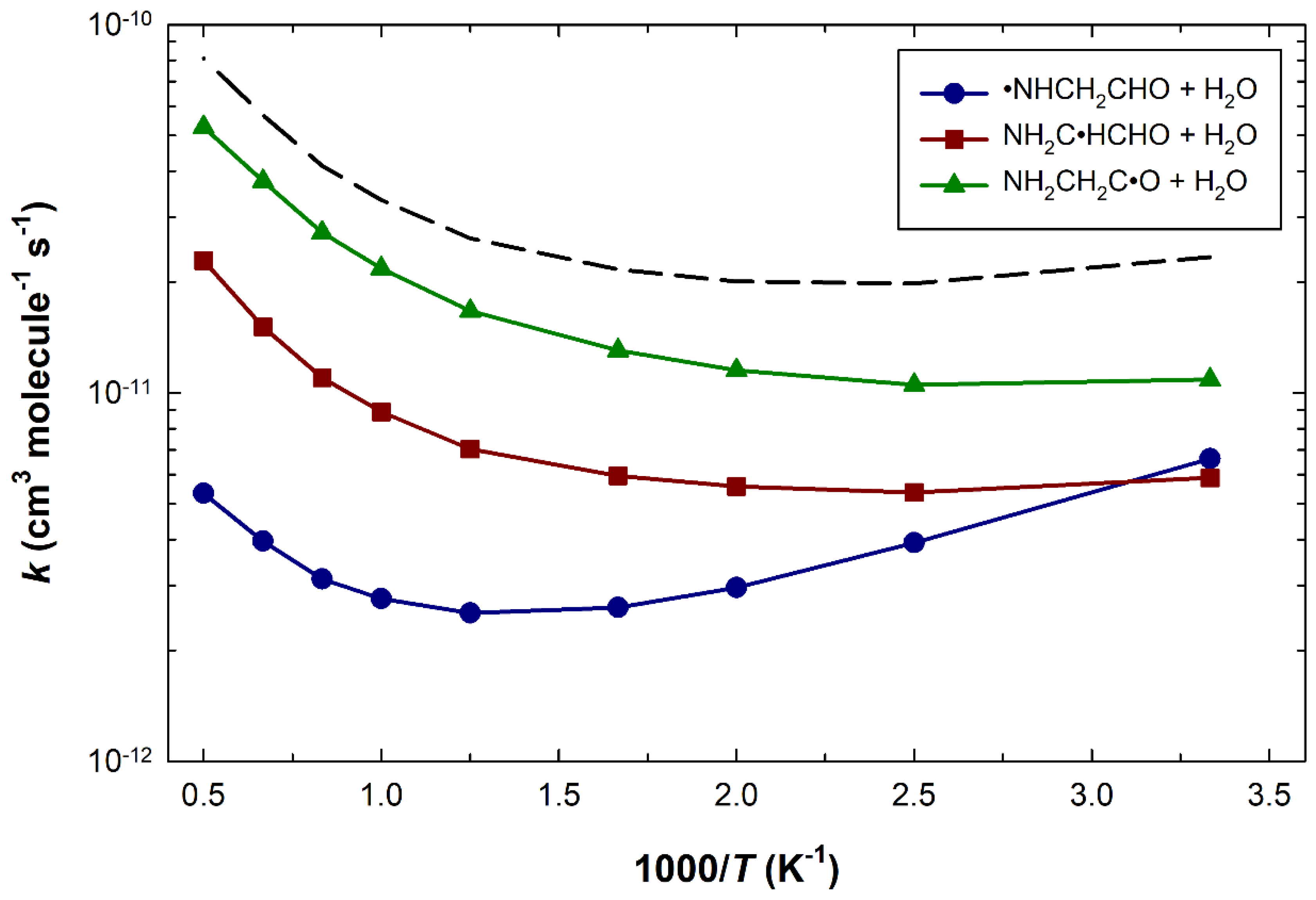

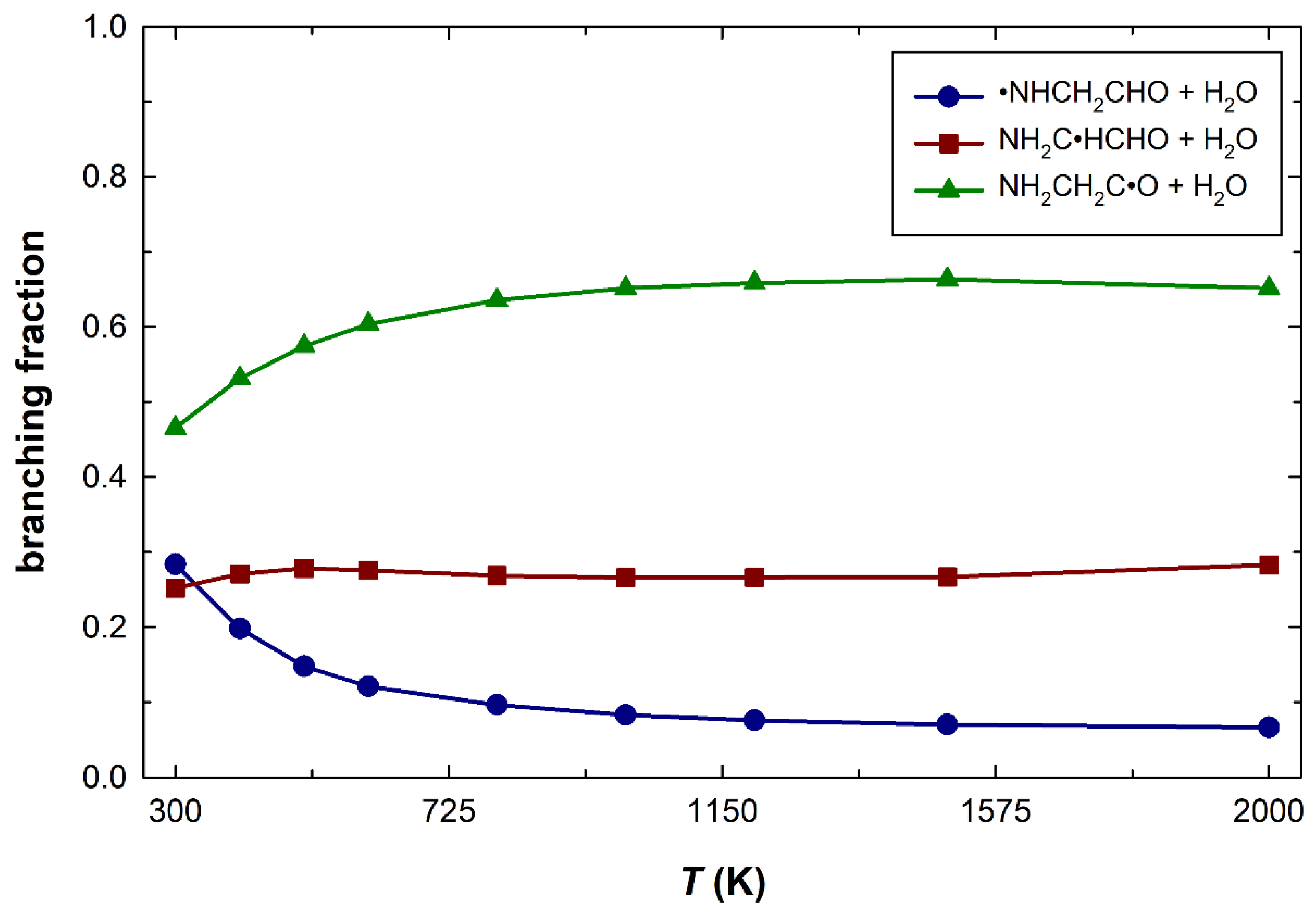

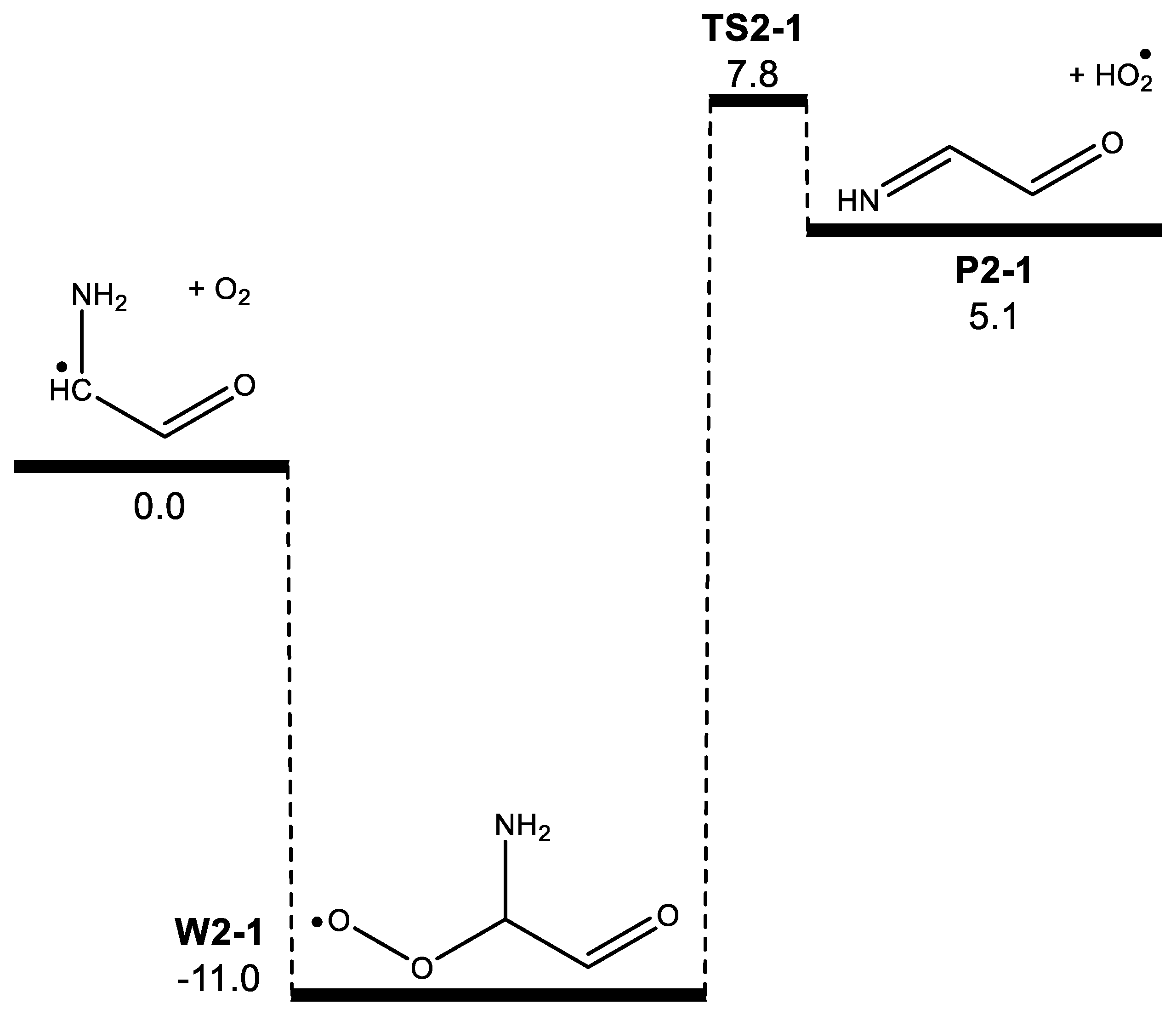

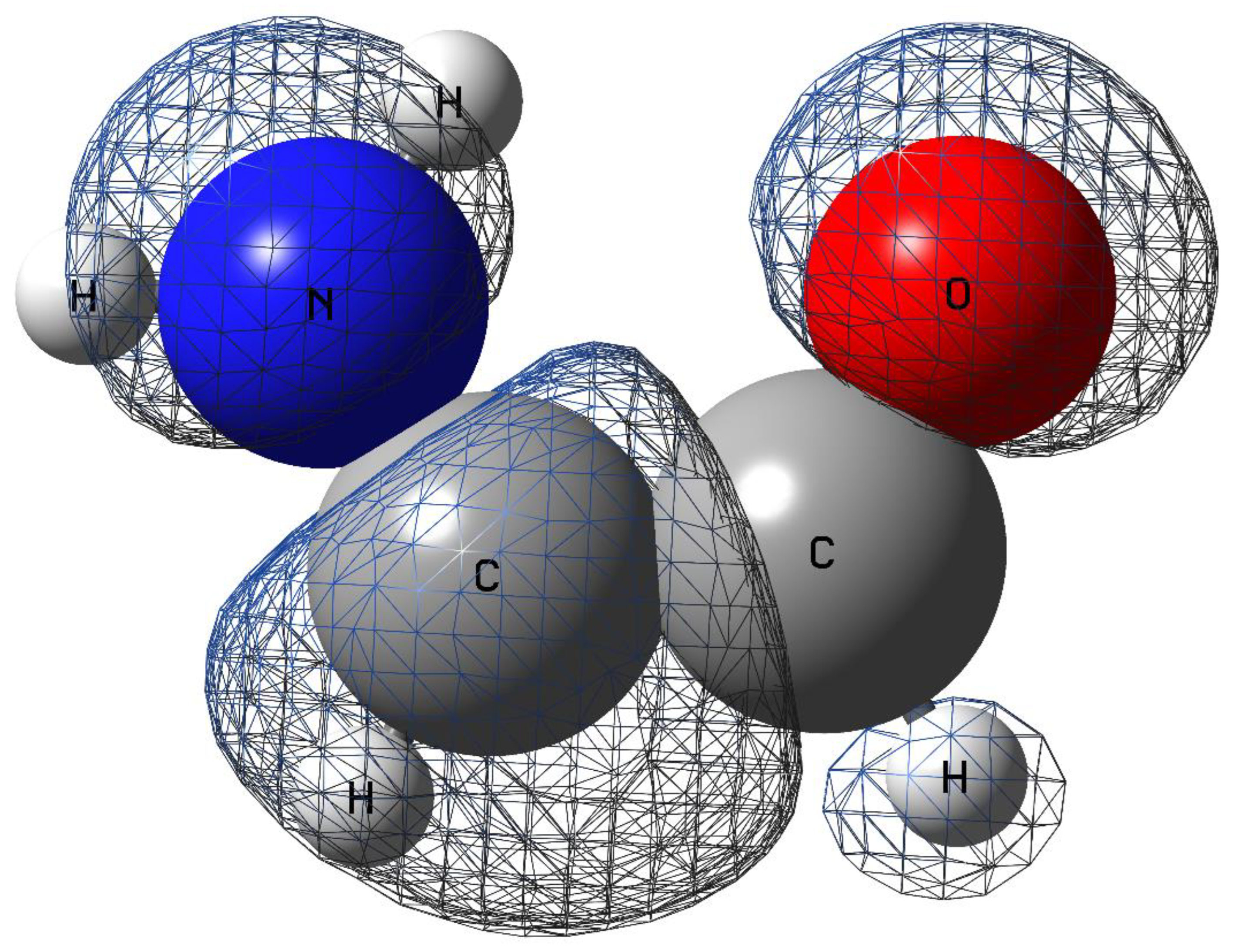

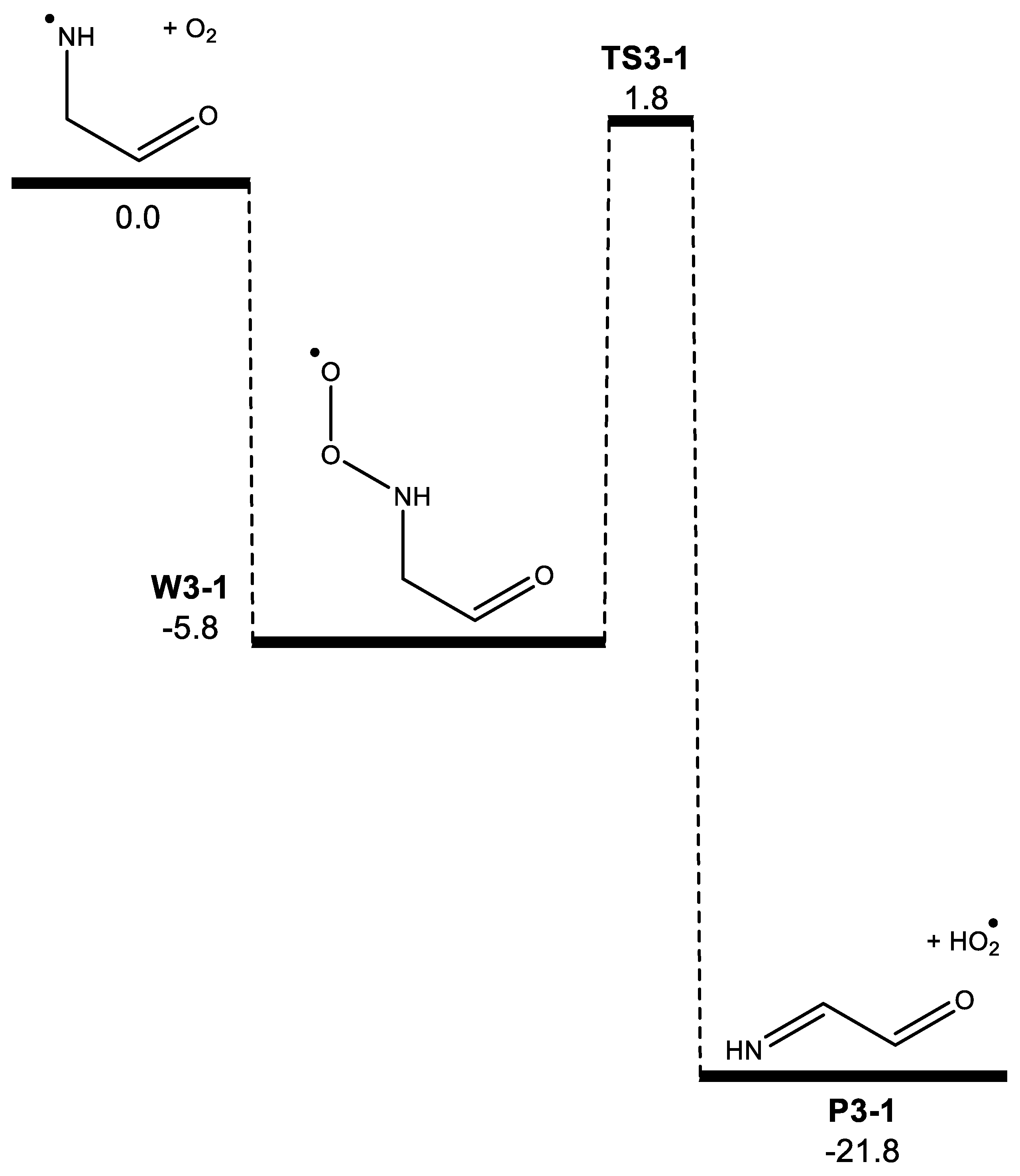

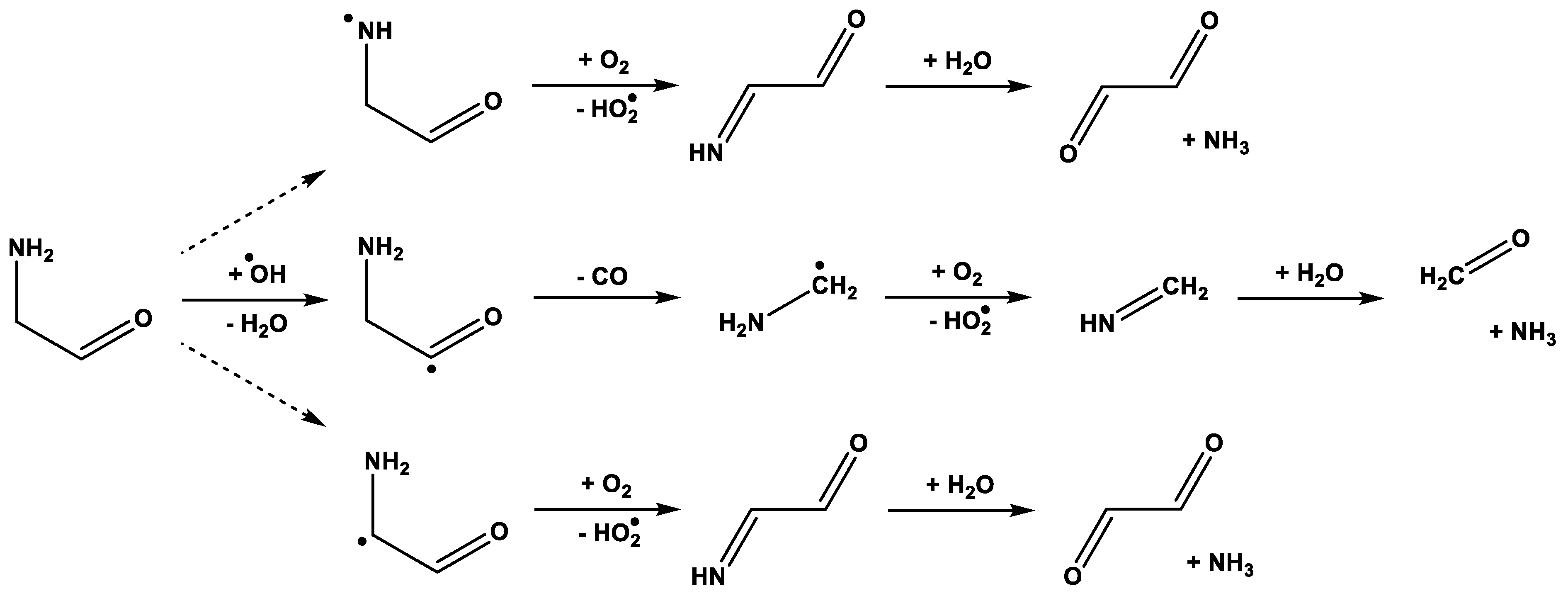

3. Results

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Veawab, A.; Tontiwachwuthikul, P.; Chakma, A. Corrosion behavior of carbon steel in the CO2 absorption process using aqueous amine solutions. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1999, 38, 3917–3924. [Google Scholar]

- Puxty, G.; Rowland, R.; Allport, A.; Yang, Q.; Bown, M.; Burns, R.; Maeder, M.; Attalla, M. Carbon dioxide postcombustion capture: A novel screening study of the carbon dioxide absorption performance of 76 amines. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 6427–6433. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, E.S.; Mantripragada, H.; Marks, A.; Versteeg, P.; Kitchin, J. The outlook for improved carbon capture technology. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2012, 38, 630–671. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, C.J.; D’Anna, B.; Dye, C.; Graus, M.; Karl, M.; King, S.; Maguto, M.M.; Müller, M.; Schmidbauer, N.; Stenstrøm, Y. Atmospheric chemistry of 2-aminoethanol (MEA). Energy Procedia 2011, 4, 2245–2252. [Google Scholar]

- Veltman, K.; Singh, B.; Hertwich, E.G. Human and environmental impact assessment of postcombustion CO2 capture focusing on emissions from amine-based scrubbing solvents to air. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 1496–1502. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Karl, M.; Wright, R.F.; Berglen, T.F.; Denby, B. Worst case scenario study to assess the environmental impact of amine emissions from a CO2 capture plant. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2011, 5, 439–447. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, A.J.; Verheyen, T.V.; Adeloju, S.B.; Meuleman, E.; Feron, P. Towards commercial scale postcombustion capture of CO2 with monoethanolamine solvent: Key considerations for solvent management and environmental impacts. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 3643–3654. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rochelle, G.T. Amine scrubbing for CO2 capture. Science 2009, 325, 1652–1654. [Google Scholar]

- Luis, P. Use of monoethanolamine (MEA) for CO2 capture in a global scenario: Consequences and alternatives. Desalination 2016, 380, 93–99. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.D.; Azzi, M. A critical review of existing strategies for emission control in the monoethanolamine-based carbon capture process and some recommendations for improved strategies. Fuel 2014, 121, 178–188. [Google Scholar]

- Pitts, J.N., Jr.; Grosjean, D.; Van Cauwenberghe, K.; Schmid, J.P.; Fitz, D.R. Photooxidation of aliphatic amines under simulated atmospheric conditions: Formation of nitrosamines, nitramines, amides, and photochemical oxidant. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1978, 12, 946–953. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, H.-B.; Li, C.; He, N.; Wang, C.; Zhang, S.; Chen, J. Atmospheric chemical reactions of monoethanolamine initiated by OH radical: Mechanistic and kinetic study. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 1700–1706. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Borduas, N.; Abbatt, J.P.; Murphy, J.G. Gas phase oxidation of monoethanolamine (MEA) with OH radical and ozone: Kinetics, products, and particles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 6377–6383. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Onel, L.; Blitz, M.; Seakins, P. Direct Determination of the Rate Coefficient for the Reaction of OH Radicals with Monoethanol Amine (MEA) from 296 to 510 K. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2012, 3, 853–856. [Google Scholar]

- Karl, M.; Dye, C.; Schmidbauer, N.; Wisthaler, A.; Mikoviny, T.; d’Anna, B.; Müller, M.; Borrás, E.; Clemente, E.; Muñoz, A. Study of OH-initiated degradation of 2-aminoethanol. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2012, 12, 1881–1901. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, G. Atmospheric chemistry of 2-aminoethanol (MEA): Reaction of the NH2•CHCH2OH radical with O2. J. Phys. Chem. A 2012, 116, 10980–10986. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- da Silva, G.; Bozzelli, J.W. Role of the a-hydroxyethylperoxy radical in the reactions of acetaldehyde and vinyl alcohol with HO2. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2009, 483, 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Bunkan, A.J.C.; Reijrink, N.G.; Mikoviny, T.; Muller, M.; Nielsen, C.J.; Zhu, L.; Wisthaler, A. Atmospheric chemistry of N-methylmethanimine (CH3N=CH2): A theoretical and experimental study. J. Phys. Chem. A 2022, 126, 3247–3264. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.; Schade, G.W.; Nielsen, C.J. Real-time monitoring of emissions from monoethanolamine-based industrial scale carbon capture facilities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 14306–14314. [Google Scholar]

- Venkata Nadh, R.; Syama Sundar, B.; Radhakrishnamurti, P.S. Kinetics of ruthenium(III) catalyzed and uncatalyzed oxidation of monoethanolamine by n-bromosuccinimide. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. A 2016, 90, 1760–1765. [Google Scholar]

- Nomoto, S.; Takasaki, M.; Sakata, N.; Harada, K. Flame-induced oxidation reaction of aliphatic amines in an aqueous solution. Tetrahed. Lett. 1983, 24, 3357–3360. [Google Scholar]

- Nomoto, S.; Shimoyama, A.; Shiraishi, S.; Sahara, D. Under-flame oxidation of amines and amino acids in an aqueous solution. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1996, 60, 1851–1855. [Google Scholar]

- Karl, M.; Svendby, T.; Walker, S.-E.; Velken, A.S.; Castell, N.; Solberg, S. Modelling atsmopheric oxidation of 2-aminoethanol (MEA) emitted from post-combustion capture using WRF-Chem. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 527–528, 185–202. [Google Scholar]

- Mestrom, L.; Bracco, P.; Hanefeld, U. Amino aldehydes revisited. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 7019, 7019–7025. [Google Scholar]

- Garrod, R.T. A three-phase chemical model of hot cores: The formation of glycine. Astrophys. J. 2013, 765, 60. [Google Scholar]

- Redondo, P.; Sanz-Novo, M.; Largo, A.; Barrientos, C. Amino acetaldehyde conformers: Structure and spectroscopic properties. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2020, 492, 1827–1833. [Google Scholar]

- Simmie, J.M. C2H5NO isomers: From acetamide to 1,2-oxazetidine and beyond. J. Phys. Chem. A 2022, 126, 924–939. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marks, J.H.; Wang, J.; Kleimeier, N.F.; Turner, A.M.; Eckhardt, A.E.; Kaiser, R.I. Prebiotic synthesis and isomerization in interstellar analog ice: Glycinal, acetamide, and their enol tautomers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202218645. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, G. G3X-K theory: A composite theoretical method for thermochemical kinetics. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2013, 558, 109–113. [Google Scholar]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, J.; Nguyen, T.; Stanton, J.; Aieta, C.; Ceotto, M.; Gabas, F.; Kumar, T.; Li, C.; Lohr, L.; Maranzana, A. MultiWell-2016 Software Suite; University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, G.; Golden, D. Application of RRKM theory to the reactions OH + NO2 + N2 → HONO2 + N2 (1) and ClO + NO2 + N2 → ClONO2 + N2 (2); a modified gorin model transition state. Int. J. Chem. Kinet. 1978, 10, 489–501. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, G. Reaction of methacrolein with the hydroxyl radical in air: Incorporation of secondary O2 addition into the MACR + OH master equation. J. Phys. Chem. A 2012, 116, 5317–5324. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ren, Z.; da Silva, G. Atmospheric oxidation of piperazine initiated by OH: A theoretical kinetics investigation. ACS Earth Space Chem. 2019, 3, 2510–2516. [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood, T.K.; Reid, R.C. The Properties of Gases and Liquids: Their Estimation and Correlation; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Ly, T.; Kirk, B.B.; Hettiarachchi, P.I.; Poad, B.L.J.; Trevitt, A.J.; da Silva, G.; Blanksby, S.J. Reactions of simple and peptidic alpha-carboxylate radical anions with dioxygen in the gas phase. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 16314–16323. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, G.; Kirk, B.B.; Lloyd, C.; Trevitt, A.J.; Blanksby, S.J. Concerted HO2 elimination from α-aminoalkylperoxyl free radicals: Experimental and theoretical evidence from the gas-phase NH2•CHCO2− + O2 reaction. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2012, 3, 805–811. [Google Scholar]

- Dash, M.R.; Ali, M.A. Can a single ammonia and water molecule enhance the formation of methanimine under tropospheric conditions? Kinetics of CH2NH2 + O2 (+NH3/H2O). Front. Chem. 2023, 11, 1243235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, G.; Dewispelaere, J.-P.; Benkadour, H.; Riffi Temsamani, D.; Wilante, C. Theoretical investigation of some evidences of the captodative effect. Bull. Soc. Chim. Belg. 1994, 103, 367–378. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, I.; Solignac, G.; Mellouki, A.; Becker, K.H. Aspects of the atmospheric chemistry of amides. ChemPhysChem 2010, 11, 3844–3857. [Google Scholar]

- Borduas, N.; da Silva, G.; Murphy, J.G.; Abbatt, J.P.D. Experimental and theoretical understanding of the gas phase oxidation of atmospheric amides with OH radicals: Kinetics, products, and mechanisms. J. Phys. Chem. A 2015, 119, 4298–4308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Borduas, N.; Abbatt, J.P.D.; Murphy, J.G.; So, S.; da Silva, G. Gas-phase mechanisms of the reactions of reduced organic nitrogen compounds with OH radicals. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 11723–11734. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M.A.; Ren, Z.; da Silva, G. Nitramine and nitrosamine formation is a minor pathway in the atmospheric oxidation of methylamine: A theoretical kinetic study of the CH3NH + O2 reaction. Int. J. Chem. Kinet. 2019, 51, 723–728. [Google Scholar]

- Yizhen, T.; Nielsen, M.; Jorgen, C. Do primary nitrosamines form and exist in the gas phase? A computational study of CH3NHNO and (CH3)2NNO. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 16365–16370. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, G. Formation of nitrosamines and alkyldiazohydroxides in the gas phase: The CH3NH + NO reaction revisited. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 7766–7772. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Ma, F.; Elm, J.; Fu, Z.; Tang, W.; Chen, J.; Xie, H.-B. Mechanism and predictive model development of reaction rate constants for N-center radicals with O2. Chemosphere 2019, 237, 124411. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, L.T.; Mai, T.V.-T.; Vien, H.D.; Nguyen, T.T.; Huynh, L.K. Ab initio kinetics of the CH3NH + NO2 reaction: Formation of nitramines and N-alkyl nitroxides. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25, 31936–31947. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Morse potential parameters | |||

| Vibrational frequency of cleaving bond (cm−1) | 152.07 | ||

| Dissociation energy (kcal mol−1) | 4.14 | ||

| Centre of mass distance between fragments (Å) | 2.5 | ||

| Capture rate (cm3 molecule−1 s−1) | 7.81 × 10−11 | ||

| Fitted Gorin parameters | |||

| η | 0.9964 (300)/0.9971 (600)/0.9973 (800)/0.9974 (1000) 0.9975 (1200)/0.9976 (1500)/0.9976 (2000) | ||

| Γ a | 0.0598 (300)/0.0540 (600)/0.0521 (800)/0.0509 (1000) 0.0501 (1200)/0.0494 (1500)/0.0493 (2000) | ||

| Moments of inertia (amu Å2) | |||

| adiabatic external rotor [2D] b | 303.5779 (300)/247.9012 (600)/225.6456 (800)/208.5839 (1000)/194.6673 (1200) 177.445(1500)/154.00 (2000) | ||

| A | Ea | |

|---|---|---|

| (cm3 molecule−1 s−1 or s−1) | (cal mol−1) | |

| NH2CH2CHO + OH → NHCH2CHO + H2O | 2.93 × 10−12 | −252 |

| NH2CH2CHO + OH → NH2CHCHO + H2O | 1.64 × 10−11 | 848 |

| NH2CH2CHO + OH → NH2CH2CO + H2O | 4.32 × 10−11 | 1060 |

| NHCH2CHO + O2 → NHCHCHO + HO2 | 4.46 × 10−14 | 3060 |

| NH2CHCHO + O2 → NHCHCHO + HO2 | 3.50 × 10−12 | 4990 |

| NH2CH2CO → CH2NH2 + CO | 3.84 × 1016 | 11,200 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alam, A.; da Silva, G. Oxidation of Aminoacetaldehyde Initiated by the OH Radical: A Theoretical Mechanistic and Kinetic Study. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1011. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos15081011

Alam A, da Silva G. Oxidation of Aminoacetaldehyde Initiated by the OH Radical: A Theoretical Mechanistic and Kinetic Study. Atmosphere. 2024; 15(8):1011. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos15081011

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlam, Ashraful, and Gabriel da Silva. 2024. "Oxidation of Aminoacetaldehyde Initiated by the OH Radical: A Theoretical Mechanistic and Kinetic Study" Atmosphere 15, no. 8: 1011. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos15081011

APA StyleAlam, A., & da Silva, G. (2024). Oxidation of Aminoacetaldehyde Initiated by the OH Radical: A Theoretical Mechanistic and Kinetic Study. Atmosphere, 15(8), 1011. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos15081011