Abstract

Background: Physical activity (PA) and weight regulation are influenced by both genetic and lifestyle factors. This study aimed to evaluate the predictive value of Polygenic Risk Scores (PRSs) for PA and weight outcomes, and their interaction with dietary habits. Methods: Baseline phenotypic data from 202 participants enrolled in the iMPROVE study were analyzed. The sample included 59 men and 143 women, aged 19–65 years. Based on baseline Body Mass Index (BMI), 75 participants were classified as having overweight and 126 as having obesity. Polygenic risk scores (PRSs) were calculated for 197 participants with available genetic data. PA was operationalized as metabolic equivalent of task minutes per week (MET-mins/week), derived from self-reported activity questionnaires. Weight-related outcomes included log-transformed weight loss from baseline to month 3 and change in BMI post-intervention. Interactions with diet were examined using both the randomized intervention dietary groups and previously extracted dietary patterns from the iMPROVE cohort. Correlation analyses and linear regression models were used to assess the main effects of PRSs and dietary patterns, as well as gene–diet interactions. Results: The measured PA PGS002254 presented a nominal significant interaction with diet group for weight loss post-intervention (B = 7.57, SE = 3.57 × 100, p = 0.04; R2 = 0.06). Similarly, the sedentary behavior PGS001923 presented a significant interaction with the “High in unsaturated fats and fruit juice consumption” pattern for baseline MET-mins/week (B = 1.51 × 103, SE = 4.135 × 102, p = 0.001; R2 = 0.091). Conclusions: Genetic predisposition influences short-term activity and weight outcomes, with dietary patterns moderating these effects. However, the multifactorial nature of lifestyle behaviors is being underscored by the modest variance explained.

1. Introduction

Obesity is identified as a multifactorial disease deriving from the interplay between genetic predisposition and environmental exposures. Heritability estimates from twin and family studies suggest that 40–75% of interindividual variation in body mass index (BMI) can be explained by genetic factors [1,2]. However, lifestyle risk factors, such as dietary and physical activity (PA) habits, remain central determinants of weight regulation and health outcomes. While PA is typically regarded as a modifiable behavior that can counterbalance obesity risk, growing evidence demonstrates that it itself is also partly influenced by increased genetic predisposition, raising important questions about its role as both an outcome of genetic liability and a modifier of obesity susceptibility [3,4].

Heritability estimates for PA behaviors, such as leisure-time PA, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA), and daily step count, range between 20% and 60%, highlighting a substantial contribution of genetic influences to their variability [3,4]. Recent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified loci associated with PA, implicating pathways related to motivation, energy balance, and even neurobehavioral regulation [5,6]. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within MC4R, TMEM18, and SH2B1, long recognized for their role in obesity susceptibility, are also associated with lower PA levels and greater sedentary behavior, suggesting pleiotropic effects that act through both metabolic and behavioral pathways [7,8,9,10]. The consequences of these genetic influences on PA extend directly to weight regulation. Reduced PA lowers energy expenditure and predisposes to positive energy balance, but it may also attenuate responsiveness to behavioral interventions targeting an increase in PA habits [11]. The current literature supports this interpretation, seeing as individuals with higher genetic risk for obesity not only engage in less spontaneous PA but also achieve smaller reductions in body weight and fat mass in response to structured exercise programs, despite demonstrating consistent adherence [12,13,14].

Recent studies suggest that physical activity levels are influenced by both genetic and environmental factors, with dietary habits playing a key role in modulating genetic risk and its subsequent effect on weight regulation. Evidence from behavioral genetics indicates that people genetically inclined toward lower levels of PA may not always exhibit this tendency, as environmental factors, such as dietary habits, can modify how and to what extent such genetic risks are expressed [15]. The latter can be mitigated by dietary habits via mechanisms of epigenetic regulation and metabolism. For example, dietary compounds such as folate, complex B vitamins, and polyphenols are important for regulating both DNA methylation and histone acetylation, which, in turn, regulate the expression of genes related to energy metabolism and neurobehavioral characteristics needed for PA [16]. In 2024, Zhang et al. noted that maintaining a healthy lifestyle, including adhering to a balanced diet, significantly reduced the genetic risk for decreased PA, suggesting that dietary habits can offset genetic susceptibility [17].

Simultaneously, sedentariness, which is often viewed as the behavioral equivalent of low levels of PA, has also demonstrated a heritable component whereby genetics can account for up to 30% of its variance [18]. Anti-inflammatory and nutrient-rich diets may help mitigate the genetic risk for sedentariness by modulating inflammation, energy metabolism, and neurobehavioral pathways [19]. For instance, Wang et al. (2025) found that people adhering to diets of low dietary inflammatory index (DII) values had a significantly lower risk of all-cause mortality despite high levels of sedentary behavior, indicating that diet can buffer the physiological consequences of inactivity [19]. Furthermore, epigenetic mechanisms may also contribute to this interaction. Nutrients, such as polyphenols, omega-3 fatty acids, and B vitamins, can alter gene expression related to the genetic predisposition toward motivation, fatigue, and energy regulation [20,21]. Although evidence directly linking diet to the attenuation of genetic risk for sedentariness has yet to be fully elucidated, these findings provide supportive information to the hypothesis that diet may attenuate the penetrance of risk to inactivity or sedentary behaviors, especially when paired with behavioral strategies. Such associations have also been displayed between dietary patterns and sedentary behavior amongst children and adolescents. In 2025, Trigueros and Aguilar-Parra (2025) emphasized that poor dietary habits during developmental stages can reinforce sedentary tendencies, whereas healthier diets may promote more active lifestyles through improved mood and energy levels [22]. These findings are further supported by evidence that inflammation-related variants have been previously associated with dietary patterns and sedentary behavior in adolescents. This suggests a potential gene–diet interaction whereby pro-inflammatory diets may exacerbate genetic predisposition toward inactivity during critical developmental periods [23].

Despite recent advances, whether genetic predisposition to PA itself influences weight loss outcomes under structured dietary interventions has yet to be fully elucidated. This distinction is critical, as individuals genetically predisposed to lower PA habits may experience greater difficulty in not only maintaining active lifestyles but also achieving weight loss, in the presence of adhering to hypocaloric dietary regimens. Addressing this gap is essential to advancing precision lifestyle interventions that integrate both behavioral and genetic dimensions of obesity risk.

In order to investigate these dynamics, we used data from the iMPROVE study, conducted in Greek adults with overweight or obesity [12,13,14]. Its initial phase assessed the baseline dietary and lifestyle components, capturing diet and PA behaviors [12], while subsequent findings demonstrated that dietary intervention led to significant weight loss and quality of life changes, irrespective of macronutrient composition [13,14]. Building on this foundation, the present study examines whether genetic predisposition for PA predicts activity levels and weight loss trajectories in response to a 6-month dietary intervention, and whether diet interacts with genetic risk for PA to shape these outcomes. By disentangling the dual role of PA—as both a genetically influenced phenotype and a behavioral modifier of genetic obesity risk—this work aims to clarify the pathways through which genes and lifestyle converge to influence weight regulation. Ultimately, it seeks to inform the design of precision-guided interventions, where diet and lifestyle strategies are tailored not only to metabolic profiles but also to genetic liability for PA behaviors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

The iMPROVE study was a dietary intervention conducted to examine the effects of adhering to hypocaloric diets of different macronutrient composition on weight loss in adults with overweight or obesity. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Harokopio University of Athens, and all participants provided written informed consent prior to participation. This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Harokopio University of Athens (protocol number 1800/13-06-2019, approval date: 13 June 2019).

The details of the study have been previously described elsewhere [12,13,14]. Participants were eligible if they were aged 18–65 years, had a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, and were generally healthy and weight-stable for at least 3 months prior to enrollment. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy or lactation at the time of enrolling in the study, diagnosis of diabetes or other chronic metabolic disease affecting weight or appetite, use of medications affecting weight or appetite, and current participation in a structured weight-loss program.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two hypocaloric diet groups: a high-carbohydrate (55–60% of total energy from carbohydrates, 15–20% from protein, and 20–25% from fat) or a high-protein diet (40% of total energy from carbohydrates, 25–30% from protein, and 30–35% from fat). Both diets were energy-restricted (~500–750 kcal/day below estimated energy needs) based on the resting energy expenditure and baseline activity levels of each individual. Meal plans, dietary guidance, and behavioral support were provided at baseline and reinforced through bi-weekly check-ins via telephone. Participants were advised to maintain their PA at their usual levels throughout the duration of their participation in the intervention.

The primary outcome was a change in body weight and BMI from baseline to the end of the 3-month period. Secondary outcomes included changes in body composition, biochemical indices, and other lifestyles characteristics (sleep quality and overall quality of life). Baseline data were included for participants with available measurements. Body mass index (BMI) and weight were collected for 202 participants. Information on physical activity, expressed as MET-minutes per week, was available for 181 participants. Participants were allocated to the dietary intervention groups as follows: 86 to the high-carbohydrate group and 95 to the high-protein group.

2.2. Assessment of Dietary Intake and PA Habits

In addition to allocating each participant to macronutrient-defined groups for the purposes of the intervention, baseline dietary intake data were recorded via a self-reported Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) [24] and were used to derive dietary patterns using principal component analysis (PCA). As previously described, five major dietary patterns were extracted, namely: the Mixed; Med-proxy; Eating-out; Traditional, vegetarian-like; and the High in unsaturated fats and fruit juice consumption [12].

PA was measured at baseline and at the end of each intervention month (months 1–3) using the short form of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ-SF) [25]. Responses were used to derive a physical activity level (PAL) score, which was categorized according to established IPAQ thresholds, namely, (i) sedentary (PAL = 1): <600 metabolic equivalent minutes per week (MET-mins/week); (ii) moderate (PAL = 2): 600–2999 MET-mins/week; and (iii) vigorous (PAL = 3): ≥3000 MET-mins/week. In addition to categorical PAL classification, continuous PA was operationalized as total MET-mins/week, calculated at each time point (baseline, end of month 1, end of month 2, and end of month 3).

2.3. Genetic Data and Polygenic Risk Scores (PRSs)

To investigate the impact of genetic predisposition on MET-minutes/week, we calculated already published PA-related Polygenic Risk Scores (PRSs), available in the PGS Catalog. We used genetic data for the iMPROVE study, and we have previously described the procedures of genotyping [13] and further imputed using the European Reference panel of the 1000 genomes Phase 3 panel via use of the plink (version 1.9; Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA, USA) [26] and IMPUTE (version 2; University of Oxford, Oxford, UK) [27] software packages. To ensure maximum coverage of the SNPs included in the candidate PRSs, we performed additional imputation was performed using the Michigan Imputation Server (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) with the Haplotype Reference Consortium (HRC) reference panel (version r1.1) [28,29].

Three polygenic risk scores (PRSs) were calculated from previously published GWAS. The first was a PRS for measured PA, constructed from accelerometer-derived activity phenotypes (PGS002255) [using accelerometer data for daily moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) and daily step count] [30]. The second was a PRS for self-reported PA, developed from leisure-time PA (MET score) derived from self-reporting in the UK Biobank. (PGS002254) [31]. The third was a PRS for sedentary behavior, based on genome-wide associations with device-measured sedentary time (i.e., time spent on watching television or using a computer) (PGS001923) [32]. These scores were selected to capture both objective and subjective dimensions of activity, as well as sedentary lifestyle patterns, enabling a comprehensive evaluation of genetic influences on physical activity and weight-related outcomes.

For each panel, we assessed the following: (i) variant coverage, defined as the proportion of SNPs from each of the selected PGS Catalog scores that were present and usable in our cohort after imputation, and (ii) predictive performance, as measured by the proportion of phenotypic variance explained (R2) in our cohort for each PRS, using linear regression models. This dual-panel approach allows for the comparison of both the technical feasibility (coverage) and biological relevance (predictive power) of PRSs derived from different imputation sources, thereby informing best practices for PRS implementation in diverse cohorts.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

For the present analyses, baseline measurements were obtained during the in-person assessment, while participant-reported data collected at the end of each subsequent month (up to three months) were used to evaluate changes from baseline. Due to the non-normal distribution of variables, descriptive statistics were reported as median and interquartile range (IQR). Baseline characteristics were compared between sexes and diet groups using the Mann–Whitney U test for independent samples and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for paired comparisons, as appropriate. Analyses were conducted on a per-protocol basis, including only participants who completed the 3-month intervention. No imputation of the missing PA data was performed; participants who discontinued the study or had incomplete follow-up data were excluded from the analysis.

To assess associations between genetic predisposition and PA, Pearson correlation coefficients were computed between each PRS and PA measures at baseline and three follow-up points (months 1–3). Furthermore, PRS low vs. high risk groups were created via dichotomization of the PRSs based on the sample’s reported median values (attribution of a value of 1 for scores below the sample’s median and a value of 2 for scores above the observed median). To evaluate the predictive performance of each of the PRSs based on the two imputation panels, we proceeded with fitting regression models with and without each PRS, adjusting for relevant covariates [i.e., age, sex, smoking (1 = Non-smoker and 2 = Smoker), and diet group]. The incremental r squared (R2) was calculated as the difference in explained variance between the full model (including the PRS) and the null model (covariates only).

To evaluate the effects of diet, PA PRSs, and their interactions on weight loss, linear regression models were fitted with weight change as the dependent variable. Independent variables included diet group (high carbohydrate vs. high protein), each of the respective PRSs, and their interaction term (diet × PA PRS), as appropriate. Linear regression models were adjusted for age, sex, and smoking status. Additionally, in order to further investigate the potential interactions with baseline dietary habits, we further examined associations between the interactions of said PRSs and the previously calculated dietary patterns. Variables not following the normal distribution were log-transformed when used as dependent variables. Model variance explained was estimated via R2.

All analyses were performed using R and Plink version 1.9, and significance was set at α = 0.05 (interaction analyses of the five dietary patterns and the six PRSs included an adjusted statistically significance threshold of α = 0.05/30 = 0.002).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

Overall, we used available baseline data for 202 participants for BMI and weight data and 181 participants for information on MET-mins/week (Table 1). Of the 181 participants enrolled at baseline, only 79 completed the 3-month intervention, reflecting a substantial dropout rate. We used the baseline vs. end-of-month 3 data to investigate the causes for dropout. The only significant baseline difference between participants who completed the 3-month study and those who dropped out was age, with dropout occurring more frequently among younger participants (p = 0.002), potentially suggesting a greater interest in well-being by participants who were older in age. The only significant difference observed between participants who completed the study at 3 months and those who dropped out was in age, suggesting dropout was more frequent in younger participants (p = 0.002). PA level (as shown in MET-min/week) differences between males and females were not statistically significant at any time point (p > 0.05). In contrast, weight and BMI demonstrated consistent reductions over time, with females showing significantly lower values than males at all measured intervals (p < 0.001 for weight; BMI differences were not statistically significant).

Table 1.

Changes in MET-minutes, weight, and BMI during the three months of the intervention, per diet group (adapted by [12]).

More specifically, PA as assessed by IPAQ-derived MET-mins/week, did not present statistically significant differentiations across the three time-points (Table 1), as instructed at baseline to the participants not to alter usual PA levels. Only participants in the high protein group demonstrated a slight decrease in MET-mins/week from baseline to the end of month 1 (p = 0.046). Within-diet group differences across the 3 months also presented no statistically significant changes. Regarding changes in BMI or weight change between groups, there were no significant differences, although both groups showed significant reductions in BMI and weight (p < 0.001 for all).

3.2. Predictive Utility of PRS for PA and Weight-Related Outcomes

Regarding the impact of imputation reference panels on PRS coverage, using the 1000 genomes phase 3 imputation panel, coverage for PGS002255 was 570,759 out of 1,140,081 SNPs (50%); for PGS002254, it was 571,001 out of 1,142,321 SNPs (49.9%); for PGS001923, it was 26,650 out of 50,583 SNPs (53%). In contrast, imputation with the HRC panel yielded higher coverage across all scores: 807,657 SNPs for PGS002255 (71%), 808,197 SNPs for PGS002254 (71%), and 36,787 SNPs for PGS001923 (73%).

To assess the predictive utility of PRS for baseline PA using MET-mins/week, we compared two linear regression models: a null model including standard covariates (age, sex, smoking status, and diet group), and a full model that additionally incorporated each PRS. Using genotype data imputed with the 1000 genomes phase 3 panel, the inclusion of PGS002255 increased the explained variance in baseline MET-mins/week from 0.9% (R2 = 0.009) to 1.76% (R2 = 0.0176), yielding an incremental R2 of 0.009. Similarly, the addition of PGS002254 and PGS001923 resulted in incremental R2 values of 0.008 and 0.011, respectively.

When using genotype data imputed with the HRC panel, predictive performance improved across all scores. The full model, including PGS002255, explained 2.2% of the variance (R2 = 0.022), corresponding to an incremental R2 of 0.013. Comparable gains were observed for PGS002254 (incremental R2 = 0.013) and PGS001923 (incremental R2 = 0.027), indicating that imputation with the HRC panel consistently enhanced the predictive power of PRSs for baseline PA levels. However, none of the PRSs were statistically significant predictors in the full models, and their overall model fits did not reach statistical significance.

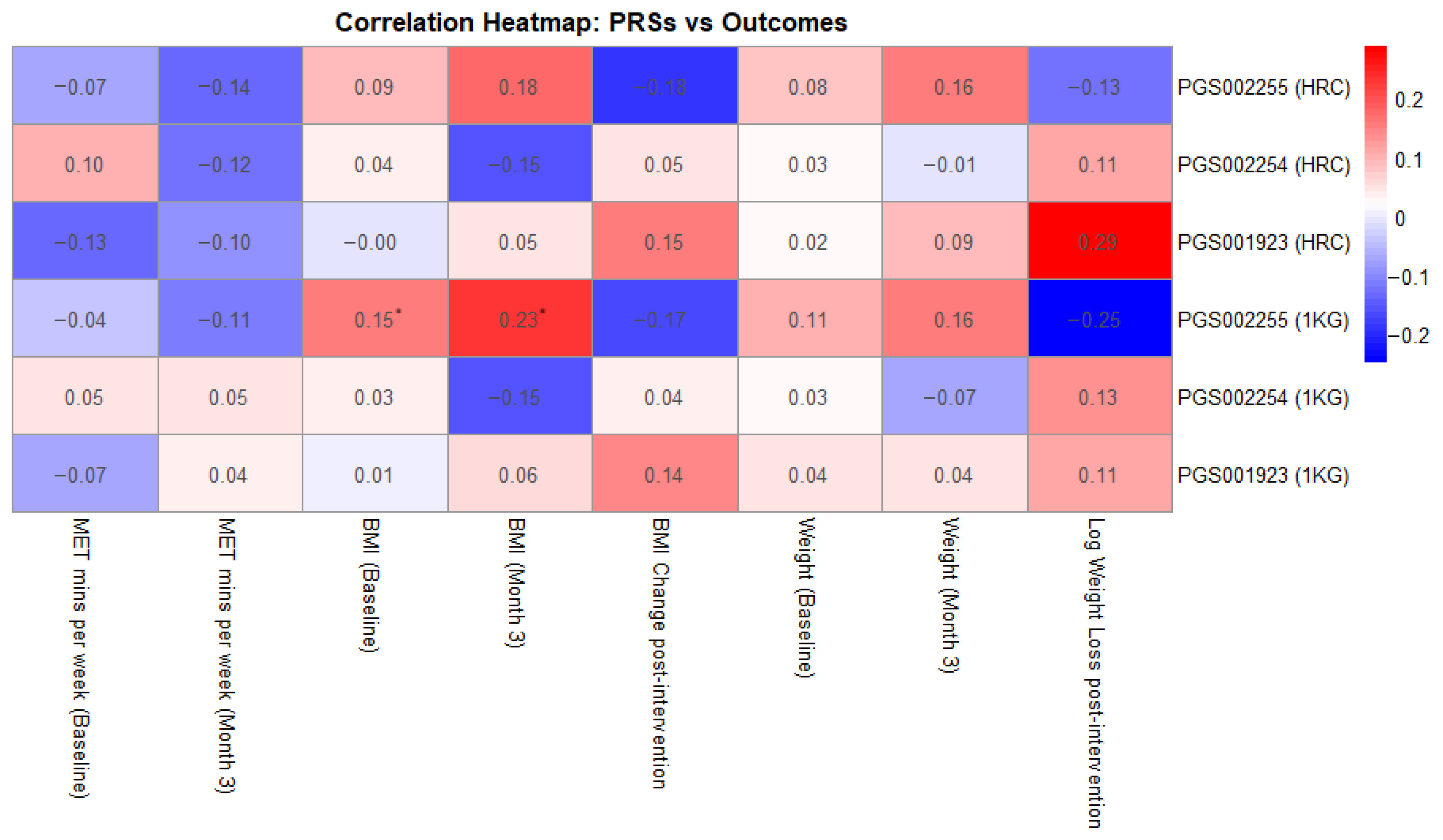

Additionally, as shown in Figure 1, we investigated correlations between the examined PRSs and MET-mins/week as well as weight loss across the 3-month intervention period. None of the PRSs showed statistically significant correlations with MET-minutes/week, either at baseline or post-intervention, with correlation coefficients ranging from −0.13 to 0.10, p-values exceeding 0.08, and confidence intervals crossing zero. Similarly, no statistically significant associations were observed between PRS and BMI change or weight loss, with coefficients ranging from −0.18 to 0.19. The strongest trend was observed for PGS001923 (HRC-imputed), which showed a weak positive correlation with weight loss (r = 0.187, p = 0.093), suggesting a potential association that warrants further investigation.

Figure 1.

Correlation heatmap between the examined PRSs and key intervention measurements (* showing statistically significant results).

The only statistically significant associations were observed for PGS002255 imputed with the 1000 Genomes panel, which showed a modest, positive correlation with baseline BMI (r = 0.154, p = 0.031) and with BMI at month 3 (r = 0.232, p = 0.036). Associations with baseline and post-intervention body weight were similarly weak and non-significant, with correlation coefficients ranging from 0.02 to 0.16 and p-values above 0.14.

3.3. Differences in Weight Loss per PRS Group

Participants with higher genetic predisposition for PA showed significant reductions in weight from baseline to month 3 across multiple PGS groups (e.g., PGS002255: Z = −5.022, p < 0.001; PGS002254: Z = −4.320, p < 0.001; PGS001923: Z = −4.015, p < 0.001), whereas participants with lower genetic predisposition did not demonstrate significant weight change (p = 0.655). These findings suggest that genetic predisposition for increased PA modulated the response to intervention with respect to weight change, while PA levels remained largely unchanged within diet groups (changes in PA are summarized in Appendix A).

3.4. PRS-Diet Effects on PA and Weight Change

Regarding PA outcomes (MET-mins/week), PGS002255 (HRC panel) showed a nominally significant negative association at the end of month 1 (Β = −3.73 × 107, p = 0.021) (Table 2), indicating that individuals with higher genetic risk scores were less likely to increase their activity levels during the early phase of the intervention. No significant main effect was observed for BMI change post-intervention (p = 0.174).

Table 2.

Associations of PRSs with PA (MET-mins/week) and weight loss post-intervention.

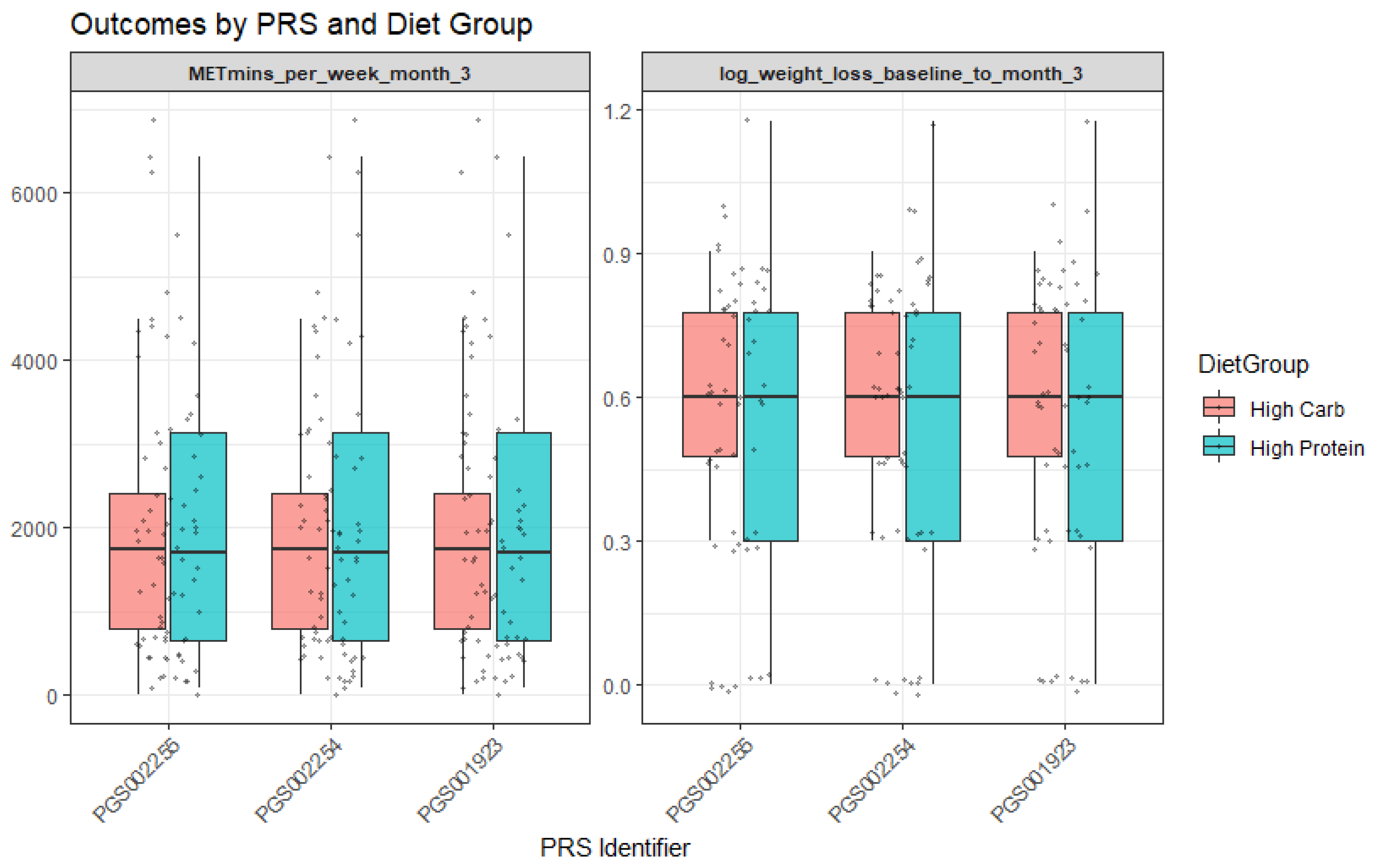

For PGS002254, baseline analyses revealed interactions with the diet group. More specifically, participants assigned to the high-protein diet group demonstrated greater log weight loss (Β = −1.17, p = 0.02). Moreover, the PGS002254 × diet group interaction was nominally significant (Β = 7.57, p = 0.04; R2 = 0.06), suggesting that genetic predisposition moderated the effect of dietary assignment on weight loss. In practical terms, individuals with higher PGS002254 values appeared to benefit more when allocated to the high-protein group (Figure 2). Finally, for PGS001923, a significant moderation effect was observed with the “High in unsaturated fat and fruit juice consumption” dietary pattern (interaction Β = 1.51 × 103, p = 0.001; R2 = 0.091). This indicates that adherence to this dietary pattern amplified the genetic influence on outcomes, with participants carrying higher genetic risk showing distinct responses when adhering to the dietary pattern rich in unsaturated fats and fruit juice.

Figure 2.

Outcomes by PRS and diet group.

4. Discussion

Using data from the iMPROVE three-month weight-loss dietary intervention, we sought to determine whether genetic predisposition for PA and sedentary behavior modifies weight loss under different macronutrient dietary regimens (high-carbohydrate vs. high-protein). Our results show that while diet remained the dominant predictor of weight loss, there were some modest gene–diet interactions, involving PRSs for PA behaviors (such as measured and self-reporting PA and time spent watching TV or on the computer) under the adherence to specific dietary patterns, although the genetic effects were small and explained little variance.

Although imputation with the HRC panel yielded higher SNP coverage across all PRSs, this did not translate into statistically significant predictive power when the scores were included in regression models alongside key covariates (age, sex, smoking status, and diet group). This outcome highlights an important nuance, referring to the fact that while higher coverage generally improves the fidelity of PRS construction, it does not guarantee stronger associations with complex traits like PA or weight loss [33]. The lack of statistical significance may reflect the modest effect sizes of individual SNPs, the multifactorial nature of the outcomes, or residual confounding [34].

Additionally, statistical significance in correlation does not always translate to meaningful variance explained in regression models, especially when effect sizes are small and confounding factors are present [35,36]. These findings underscore the importance of evaluating PRS performance not only by technical metrics like coverage, but also by their incremental contribution to explained variance and statistical robustness within multivariable models. Additionally, they underscore the complexity of PRS performance, where imputation quality, variant informativeness, and trait architecture all interact, as previously shown in PRS development using cohorts of various sizes [37,38].

The measured PA for PGS002255 showed gene–diet interaction signals with diet group at the end of month 1, suggesting that genetic predisposition for PA might be modulated by the dietary context, specifically in the allocation to the high-protein group. The self-reported PA for PGS002254 showed a significant interaction with diet group, highlighting that individuals with increased genetic risk for PA can benefit from adhering to a high-protein diet to achieve better weight loss. Mechanistically, diets high in protein could help compensate for genetic predispositions to low PA by increasing thermogenesis, satiety, and preserving lean body mass [39].

Importantly, sedentary behavior was analyzed as a distinct construct from PA, consistent with current consensus in the literature. The sedentary behavior for PRS001923 was based on hours spent watching television or using the computer, and it demonstrated an interaction with the “High in unsaturated fat and fruit juice consumption” dietary pattern in increasing baseline MET-mins/week. This distinction is critical, as individuals may simultaneously meet PA guidelines while engaging in prolonged sedentary time, and our findings reflect genetic predisposition specifically for sedentary time rather than a general “sedentary vs. active” lifestyle. Likewise, dietary patterns rich in unsaturated fats, fruit, and adhering to Mediterranean-type features may provide metabolic flexibility, reduce inflammation, or otherwise ameliorate the negative effects of sedentariness. These mechanisms are consistent with those proposed in the obesity genetics × diet quality literature [39].

Our results suggest that genetic risk for PA and sedentary behavior may more strongly interact with certain dietary patterns, namely those higher in protein or richer in unsaturated fats and fruit juice. This finding is in line with observational meta-analytic evidence showing that higher diet quality attenuates the effect of obesity polygenic risk on BMI and waist circumference [40]. Overall, dietary habits assessed via adherence to extracted dietary patterns have been previously shown to mediate or attenuate genetic predisposition for not only anthropometric but also inflammatory indices [23,41,42]. While many studies on diet and PRS interactions focus on obesity risk rather than weight loss trials per se, the current literature provides limited evidence for the effects of genetic background on PA as a lifestyle factor. For example, a systematic review and meta-analysis found that individuals with higher adherence to plant-based or high-quality dietary patterns had weaker associations between genetic risk and obesity-related anthropometric outcomes [42,43].

Although interaction signals were present, direct genetic effects masked very little weight loss, with diet group assignment remaining the most important predictor for weight change. This mirrors findings from trials in which macronutrient differences drive weight/fat mass loss more strongly than other modifiers when energy intake is controlled [43].

Despite the consistent-with-literature demonstrated findings, our study has several limitations: (i) the 3-month duration may be insufficient to detect longer-term gene × diet interactions or to assess sustainability of weight loss; (ii) our sample size, while usually adequate, may still limit power for detecting small genetic effects, especially interactions; (iii) the use of self-reporting for some PA metrics could introduce measurement error, weakening associations. Additionally, dietary-pattern factors are derived post hoc via factor analysis and may not align perfectly with standardized definitions of Mediterranean diet or unsaturated fat-rich diets in other studies.

5. Conclusions

In summary, our results suggest that while genetic predisposition for sedentary behavior or low physical activity does modestly interact with dietary patterns to influence weight loss, these interactions are small, and diet composition—especially higher protein intake and higher quality dietary patterns—is the more potent determinant. These findings support the potential value of personalizing weight loss interventions by dietary quality in addition to macronutrient distribution, especially for individuals with higher genetic risk for sedentariness. Future, longer, larger studies with richer phenotyping of behavior and activity are needed to clarify who benefits most from which diet in the context of genetic risk.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K. and G.V.D.; methodology, M.K. and P.S.; software, P.S. and P.M.; validation, M.K.; formal analysis, M.K.; investigation, M.K., I.P.K., P.S., and P.M.; resources, G.V.D.; data curation, M.K., P.S., P.M., and I.P.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K.; writing—review and editing, M.K., I.P.K., P.M., and P.S.; visualization, M.K. and G.V.D.; supervision, G.V.D.; project administration, G.V.D.; funding acquisition, G.V.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is co-financed by Greece and the European Union (European Social Fund-ESF) through the Operational Programme “Human Resources Development, Education and Lifelong Learning 2014–2020” in the context of the project “SUPPORT OF YOUNG RESEARCHERS—CALL B’, ESPA 2014–2020: 61109” (MIS 5048457). This research has also been completed in the context of the BETTER4U project, receiving funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement no. 101080117.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Harokopio University of Athens (protocol number 1800/13-06-2019, approval date: 13 June 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to participants’ privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their gratitude to all the healthcare professionals and students (dietitians/nutritionists) of the Department of Nutrition and Dietetics at Harokopio University of Athens, for their invaluable contributions during the volunteers’ recruitment and monitoring stages. Furthermore, the authors would like to sincerely thank all volunteers of the study for their effective and fruitful cooperation.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare no interests and no conflicts between their affiliations and this publication.

Appendix A. Differences in PA per Diet Group

Changes in physical activity, measured as MET-minutes per week, were examined across the three time points within each diet group using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Specifically, the Wilcoxon signed-rank tests showed that differences between month 1 and month 2 (Diet Group 1: Z = −0.598, p = 0.550; Diet Group 2: Z = −0.175, p = 0.861), month 2 and month 3 (Diet Group 1: Z = −0.184, p = 0.854; Diet Group 2: Z = −1.316, p = 0.188), and baseline and month 3 (Diet Group 1: Z = −0.384, p = 0.701; Diet Group 2: Z = −1.116, p = 0.264) were not statistically significant.

References

- Maes, H.H.; Neale, M.C.; Eaves, L.J. Genetic and environmental factors in relative body weight and human adiposity. Behav. Genet. 1997, 27, 325–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wardle, J.; Carnell, S.; Haworth, C.M.; Plomin, R. Evidence for a strong genetic influence on childhood adiposity despite the force of the obesogenic environment. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 398–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stubbe, J.H.; Boomsma, D.I.; Vink, J.M.; Cornes, B.K.; Martin, N.G.; Skytthe, A.; Kyvik, K.O.; Rose, R.J.; Kujala, U.M.; Kaprio, J.; et al. Genetic influences on exercise participation in 37,051 twin pairs from seven countries. PLoS ONE 2006, 1, e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Geus, E.J.C.; de Moor, M.H.M. Genes, exercise, and psychological factors. In Genetic and Molecular Aspects of Sport Performance; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimentidis, Y.C.; Raichlen, D.A.; Bea, J.; Garcia, D.O.; Wineinger, N.E.; Mandarino, L.J.; Alexander, G.E.; Chen, Z.; Going, S.B. Genome-wide association study of habitual physical activity in over 377,000 UK Biobank participants identifies multiple variants including CADM2 and APOE. Int. J. Obes. 2018, 42, 1161–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doherty, A.; Smith-Byrne, K.; Ferreira, T.; Holmes, M.V.; Holmes, C.; Pulit, S.L.; Lindgren, C.M. GWAS identifies 14 loci for device-measured physical activity and sleep duration. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 5257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradfield, J.P.; Vogelezang, S.; Felix, J.F.; Chesi, A.; Helgeland, Ø.; Horikoshi, M.; Karhunen, V.; Lowry, E.; Cousminer, D.L.; Ahluwalia, T.S.; et al. A trans-ancestral meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies reveals loci associated with childhood obesity. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2019, 28, 3327–3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huszar, D.; Lynch, C.A.; Fairchild-Huntress, V.; Dunmore, J.H.; Fang, Q.; Berkemeier, L.R.; Gu, W.; Kesterson, R.A.; Boston, B.A.; Cone, R.D.; et al. Targeted disruption of the melanocortin-4 receptor results in obesity in mice. Cell 1997, 88, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheutlin, A.B.; Dennis, J.; Karlsson Linnér, R.; Moscati, A.; Restrepo, N.; Straub, P.; Ruderfer, D.; Castro, V.M.; Chen, C.-Y.; Ge, T.; et al. Penetrance and Pleiotropy of Polygenic Risk Scores for Schizophrenia in 106,160 Patients Across Four Health Care Systems. Am. J. Psychiatry 2019, 176, 846–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Zhao, J.H.; Luan, J.; Ekelund, U.; Luben, R.N.; Khaw, K.-T.; Wareham, N.J.; Loos, R.J.F. Physical activity attenuates the genetic predisposition to obesity in 20,000 men and women from EPIC-Norfolk study. PLoS Med. 2010, 7, e1000332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.K.; Floegel, T.A.; Li, L.C.; Leese, J.; De Vera, M.A.; Beauchamp, M.R.; Taunton, J.; Liu-Ambrose, T.; Allen, K.D. Tailored physical activity behavior change interventions: Challenges and opportunities. Transl. Behav. Med. 2021, 11, 2174–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafyra, M.; Kalafati, I.P.; Katsareli, E.A.; Lambrinou, S.; Varlamis, I.; Kaliora, A.C.; Dedoussis, G.V. The iMPROVE Study. Design, Dietary Patterns, and Development of a Lifestyle Index in Overweight and Obese Greek Adults. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kafyra, M.; Kalafati, I.P.; Stefanou, G.; Kourlaba, G.; Moulos, P.; Varlamis, I.; Kaliora, A.C.; Dedoussis, G.V. A Dietary Intervention in Adults with Overweight or Obesity Leads to Weight Loss Irrespective of Macronutrient Composition: The iMPROVE Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kafyra, M.; Kalafati, I.P.; Varlamis, I.; Kaliora, A.C.; Moulos, P.; Dedoussis, G.V. A randomized clinical trial of a dietary intervention and mental health associations in adults with increased genetic risk for obesity. Sci Rep. 2025, 15, 14188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnurr, T.M.; Stallknecht, B.M.; Sørensen, T.I.A.; Kilpeläinen, T.O.; Hansen, T. Evidence for shared genetics between physical activity, sedentary behaviour and adiposity-related traits. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, L.; Knorr, S.; Antoniussen, C.S.; Bruun, J.M.; Ovesen, P.G.; Fuglsang, J.; Kampmann, U. The Impact of Lifestyle, Diet and Physical Activity on Epigenetic Changes in the Offspring-A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Peila, R.; Wang, T.; Xue, X.; Kaplan, R.C.; Dannenberg, A.J.; Qi, Q.; Rohan, T.E. Associations of Lifestyle and Genetic Risks with Obesity and Related Chronic Diseases in the UK Biobank: A Prospective Cohort Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 119, 1514–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zi, Y.; van der Ploeg, H.P.; de Geus, E.J.C. Genetics of sedentariness. In Sedentary Behaviour Epidemiology; Leitzmann, M.F., Jochem, C., Schmid, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, X.; Chen, Y. Anti-inflammatory diets might mitigate the association between sedentary behaviors and the risk of all-cause deaths. Nutr. Metab. 2025, 22, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mititelu, M.; Lupuliasa, D.; Neacșu, S.M.; Olteanu, G.; Busnatu, Ș.S.; Mihai, A.; Popovici, V.; Măru, N.; Boroghină, S.C.; Mihai, S.; et al. Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Human Health: A Key to Modern Nutritional Balance in Association with Polyphenolic Compounds from Food Sources. Foods 2024, 14, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesada-Vázquez, S.; Eseberri, I.; Les, F.; Pérez-Matute, P.; Herranz-López, M.; Atgié, C.; Lopez-Yus, M.; Aranaz, P.; Oteo, J.A.; Escoté, X.; et al. Polyphenols and metabolism: From present knowledge to future challenges. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 80, 603–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigueros, R.; Aguilar-Parra, J.M. Dietary and Sedentary Behavior in Children and Adolescents. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafyra, M.; Kalafati, I.P.; Gavra, I.; Siest, S.; Dedoussis, G.V. Associations of VEGF-A-Related Variants with Adolescent Cardiometabolic and Dietary Parameters. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bountziouka, V.; Bathrellou, E.; Giotopoulou, A.; Katsagoni, C.N.; Bonou, M.; Vallianou, N.; Barbetseas, J.; Avgerinos, P.; Panagiotakos, D. Development, repeatability and validity regarding energy and macronutrient intake of a semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire: Methodological considerations. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2012, 22, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). Revised in 2013. Available online: https://sites.google.com/site/theipaq/questionnaire_links (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Chang, C.C.; Chow, C.C.; Tellier, L.C.A.M.; Vattikuti, S.; Purcell, S.M.; Lee, J.J. Second-generation PLINK: Rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. GigaScience 2015, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howie, B.; Fuchsberger, C.; Stephens, M.; Marchini, J.; Abecasis, G.R. Fast and accurate genotype imputation in genome-wide association studies through pre-phasing. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 955–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; Forer, L.; Schönherr, S.; Sidore, C.; Locke, A.E.; Kwong, A.; Vrieze, S.I.; Chew, E.Y.; Levy, S.; McGue, M.; et al. Next-generation genotype imputation service and methods. Nat Genet. 2016, 48, 1284–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, S.; Das, S.; Kretzschmar, W.; Delaneau, O.; Wood, A.R.; Teumer, A.; Kang, H.M.; Fuchsberger, C.; Danecek, P.; Sharp, K.; et al. A reference panel of 64,976 haplotypes for genotype imputation. Nat Genet. 2016, 48, 1279–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catalog PGS. PGS002255: Polygenic Score for Accelerometer-Based Physical Activity (measured PA). PGS Catalog. 2021. Available online: https://www.pgscatalog.org/score/PGS002255 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Catalog PGS. PGS002254: Polygenic Score for Self-Reported Physical Activity. PGS Catalog. 2021. Available online: https://www.pgscatalog.org/score/PGS002254 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Catalog PGS. PGS001923: Polygenic Score for Device-Measured Sedentary Behavior. PGS Catalog. 2020. Available online: https://www.pgscatalog.org/score/PGS001923 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Chen, S.F.; Dias, R.; Evans, D.; Salfati, E.L.; Liu, S.; Wineinger, N.E.; Torkamani, A. Genotype imputation and variability in polygenic risk score estimation. Genome Med. 2020, 12, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzerova, J.; Hurta, M.; Barton, V.; Lexa, M.; Walther, D.; Provaznik, V.; Weckwerth, W. A perspective on genetic and polygenic risk scores-advances and limitations and overview of associated tools. Brief Bioinform. 2024, 25, bbae240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kullo, I.J. Clinical use of polygenic risk scores: Current status, barriers and future directions. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, D.; Eshetie, S.; Beckmann, K.; Benyamin, B.; Lee, S.H. Advancements and limitations in polygenic risk score methods for genomic prediction: A scoping review. Hum. Genet. 2024, 143, 1401–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giardoglou, P.; Gavra, I.; Amanatidou, A.I.; Kalafati, I.P.; Symianakis, P.; Kafyra, M.; Moulos, P.; Dedoussis, G.V. Development of a Polygenic Risk Score for Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease Prediction in UK Biobank. Genes 2024, 16, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kafyra, M.; Kalafati, I.P.; Dimitriou, M.; Grigoriou, E.; Kokkinos, A.; Rallidis, L.; Kolovou, G.; Trovas, G.; Marouli, E.; Deloukas, P.; et al. Robust Bioinformatics Approaches Result in the First Polygenic Risk Score for BMI in Greek Adults. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, E.M.; Mojtahedi, M.C.; Thorpe, M.P.; Valentine, R.J.; Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Layman, D.K. Effects of protein intake and gender on body composition changes: A randomized clinical weight loss trial. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 9, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.Y.; Masip, G.; Meng, T.; Nielsen, D.E. Interactions between Polygenic Risk of Obesity and Dietary Factors on Anthropometric Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. J. Nutr. 2024, 154, 3521–3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmaki, A.E.; Rayner, N.W.; Kafyra, M.; Matchan, A.; Ntaoutidou, K.; Feritoglou, P.; Athanasiadis, A.; Gilly, A.; Mamakou, V.; Zengini, E.; et al. A Dietary Pattern with High Sugar Content Is Associated with Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in the Pomak Population. Nutrients 2019, 11, 3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafyra, M.; Kalafati, I.P.; Kumar, S.; Kontoe, M.S.; Masson, C.; Siest, S.; Dedoussis, G.V. Dietary Patterns, Blood Pressure and the Glycemic and Lipidemic Profile of Two Teenage, European Populations. Nutrients 2021, 13, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotakis, C.; Amanatidou, A.I.; Kafyra, M.; Andreou, V.; Kalafati, I.P.; Zervou, M.; Dedoussis, G.V. Circulatory Metabolite Ratios as Indicators of Lifestyle Risk Factors Based on a Greek NAFLD Case-Control Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.