Abstract

Background: The ATP-binding cassette (ABC) G subfamily, a key member of the ABC protein family, mediates plant stress responses by transporting metabolites across membranes, but its mechanism of action in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) remains poorly understood. Methods: We systematically analyzed the evolutionary relationships, structural characteristics, stress-responsive expression patterns, and functional roles in response to saline-alkali stress of the SlABCG gene family in tomato, using a combination of approaches including phylogenetic analysis (MEGA), gene structure and motif analysis (GSDS, MEME), cis-acting element prediction, homology analysis, transcriptome analysis, protein-protein interaction prediction, and qRT-PCR validation. Results: We identified a total of 41 SlABCG genes from the tomato genome. These genes, together with 43 ABCG genes from Arabidopsis thaliana, were clustered into five distinct clades. There are 35 collinear gene pairs between the SlABCG gene family in tomato and the ABCG gene family in Arabidopsis, while 39 collinear gene pairs exist among ABCG genes within the tomato genome itself.The promoter regions of SlABCG genes contain cis-acting elements associated with responses to salicylic acid, low temperature, and gibberellin stresses. Transcriptome sequencing revealed that six SlABCG genes responded to saline-alkali stress. Gene regulatory network prediction revealed that multiple genes related to saline-alkali stress were regulated. Expression profile analysis of the 25 upregulated genes revealed that all of them were significantly upregulated during the saline-alkali stress treatment. Conclusions: In summary, our results provide deep insights into the characteristics of the SlABCG subfamily, facilitate the design of effective analysis strategies, and offer data support for exploring the roles of ABCG transporters under different stress conditions.

1. Introduction

The ATPase-binding cassette (ABC) proteins are composed of two conserved domains, including the nucleotide-binding domain (NBD) and transmembrane domain (TMD), and their subfamilies are ubiquitous in plants [1,2]. The main function of the membrane-bound transporters encoded by the ABC transporter gene family is to mediate the molecular transport of soluble proteins between different cells or across the plasma membrane [2]. To date, a large number of ABC transporters have been identified in various plants, including Arabidopsis thaliana, rice, Capsicum spp., soybean, Linum usitatissimum L., China rose, grape, and Camellia sinensis [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. The plant ABC transporter gene family is primarily categorized into eight subfamilies, designated as ABCA to ABCI, with ABCH excluded [12]. Unlike other subfamilies, the ABCG subfamily is arranged according to the structural organization of the nucleotide-binding domain (NBD)–transmembrane domains (TMDs) [13]. Based on the composition of the NBD and TMD, ABCG transporters can be divided into two categories, including the half-size molecular transporter (white–brown complex, WBC) with the NBD-TMD and PDR (pleiotropic drug resistance) arranged in the NBD-TMD-NBD-TMD structure [14,15].

As the largest subfamily of the ABC gene family, the ABCG is involved in various biological processes in plants, such as male reproduction and phytohormone transport [16,17]. During the salt stress treatment of rice, the ABCG7 mutant exhibits a high degree of leaf wilting, low survival rate, and reduced salt tolerance [18]. AtABCG36 contributes to salt resistance in Arabidopsis by a mechanism that includes the reduction of sodium content in plants [19]. Under salt stress conditions, the ABCG proteins in different tissues of Betula halophila responded differently. For instance, the expression of BhABC12 in the xylem and leaves was upregulated; BhABC14 in the xylem, roots, and leaves showed varying degrees of upregulation; and the expression of BhABC15 in the xylem and roots was downregulated [20]. The ABCC subfamily member ZmMRPA6 of maize can enhance its salt tolerance [21]. In transgenic tobacco, the overexpression of MsABCG1 can enhance plant drought tolerance by regulating the increase of osmolytes and the reduction of lipid peroxidation, and also has the potential to regulate stomata [22]. After double knockdown of the ABCG17 and ABCG18 genes, it was found that the transporters encoded by these genes can not only limit stomatal aperture, conductance, and transpiration, but also improve water-use efficiency. Additionally, they can regulate the translocation of abscisic acid (ABA) from the shoot to the root, thereby modulating lateral root development [23]. VvABCC1 regulates anthocyanin transport, thereby influencing the color of grapes [10]. These studies indicate that members of the ABCG subfamily play a crucial role in regulating plant stress tolerance, growth, and development. Although the ABCG gene subfamily in tomato has been identified, its functional mechanisms remain unanalyzed [24].

Abiotic stresses, as major adverse environmental conditions, can reduce plant yield and quality [25]. For tomato, the key factors affecting its yield and quality mainly include extreme temperatures, drought, and soil salinization [26]. Thus, the identification of key genes in tomato that respond to abiotic stresses not only facilitates the elucidation of its tolerance mechanisms but also provides a crucial theoretical basis and practical guidance for the breeding of stress-resistant plants, thereby holding significant importance. This study analyzed the characteristics of the ABCG subfamily in tomato, including their phylogenetic relationships, gene structures, cis-acting elements, and interaction networks. By detecting the expression of the ABCG gene under different abiotic stresses, we identified candidate genes with the potential to tolerate various abiotic stresses. This study contributes to revealing the potential functions of tomato ABCG genes under abiotic stresses and ultimately provides a theoretical basis and practical reference for the cultivation of tomato with broad-spectrum resistance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Treatments

This study used seeds of the Micro-Tom tomato, which were first germinated under conditions of 25~28 °C, approximately 75% relative humidity, 12/12 h (light/dark) photoperiod achieved with natural light and augmented with supplemental lights (400 W high-pressure sodium lamp) and 1400 μmol·s−1·m−2 average photosynthetic photon flux density across replications for daytime hours. After the seedlings developed 4~6 true leaves, those with uniform growth were transplanted into plastic containers containing new Hoagland nutrient solutions (pH 5.5~6.5), with their roots subjected to dark treatment. At this point, the tomato seedlings were randomly divided into two groups: the control group (CK) was cultured only with Hoagland nutrient solution; the treatment group (N) was supplemented with 300 mM mixed saline–alkali solution in Hoagland nutrient solution (the molar ratio of each component was NaCl:Na2SO4:NaHCO3:Na2CO3 = 1:9:9:1, pH = 8.6 ± 0.1). The solution was replaced every 2 d. Samples were collected at 0 h, 4 h, and 8 h after treatment, with 3 biological replicates set for each treatment.

2.2. RNA Extraction and RNA-seq

Total RNA was extracted from tomato seedlings under saline–alkali stress using the Trizol reagent (TaKaRa, Shiga, Japan), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used to analyze the integrity, quality, and concentration of the extracted RNAs. High-quality RNA samples were selected to construct cDNA libraries using the VAHTS Universal V10 RNA-seq Library Prep Kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China), and sequencing was performed on the Illumina HiSeq™ 2500 platform (Shanghai, China) based on the standard protocols.

2.3. Transcriptome Data Collection

In this study, tomato transcriptome data under different stress treatments were retrieved from the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). The BioProject numbers of the tomato transcriptome data under different treatments are as follows: ABA treatment is PRJNA947059 (the leaves of the tomato plants that had grown four true leaves were collected after being sprayed with 10 mL of 100 μM ABA). Light treatment is PRJNA270083—tomato plants underwent one of four treatments: control (mock, nightly dark environment with MgCl2 treatment), RL (nightly red light treatment with MgCl2 treatment), DC3000 (nightly dark environment with DC3000 inoculation), and RL + DC3000 (nightly red light treatment with DC3000 inoculation); leaves were collected from the plants at 5:00 AM the next day after treatment. Low-temperature treatment is PRJNA484882 (tomato leaves were treated at 4 °C) and SA treatment is PRJNA846581 (after 3 weeks of growth, when the tomato plants had 5 to 6 leaves, they were sprayed with 0.5 mM SA and the leaves were collected).

2.4. Transcriptome Data and Differential Expression Analysis

The collected and sequenced transcriptome data were analyzed in this study. Firstly, the Trimmomatic software (v0.39) was used to remove low-quality bases and adaptors [27]. All clean reads of the samples were aligned to the tomato reference genome (SL3.0) using HISAT (v2.1.0) [28]. The StringTie software (v2.1.3) was employed to assemble transcripts in each sample, which were then aligned to the tomato reference genome using Gffcompare (v0.11.2). The Salmon software (v0.14.1) was utilized to quantify all transcripts, with expression levels represented by TPM [29]. For differential expression analysis, the R packages DESeq2 (v1.30.0) and edgeR were used for data with and without biological replicates, respectively [30,31]. The identification criteria were set as false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 and log2 (fold change) > 1.

2.5. Phylogenetic, Gene Structure, and cis-Regulatory Element Analysis

An unrooted phylogenetic tree of ABCG protein sequences from tomato and Arabidopsis was constructed using the MEGA 7.0 software with the neighbor-joining method, and the bootstrap value was set to 1000 [32]. We modified the phylogenetic tree using Evolview [33]. In this study, genomic sequences and the corresponding coding nucleotide sequences were downloaded from the tomato genome database, and the intron–exon distribution of ABCG genes was analyzed using the Gene Structure Display Server (GSDS) [34]. Conserved motifs were predicted with the MEME server [35], and cis-regulatory elements in the promoter regions of the ABCG genes were predicted via the PlantCARE database [36]. In this study, the 2 kb sequence upstream of the ABCG genes on the chromosome was defined as the promoter region.

2.6. Chromosomal Distribution and Gene Duplication Analysis

The distribution of ABCG genes on tomato chromosomes was visualized using the TBtools software. To detect gene duplication events and collinear relationships, the TBtools software was also employed to analyze ABCG transporter genes in tomato, potato, and Arabidopsis [37].

2.7. Functional Enrichment and Prediction of Tomato ABCG Protein Interaction Network

The KOBAS server was used to perform a KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) enrichment analysis [38]. The online software STRING 12.0: https://cn.string-db.org/ (accessed on 1 April 2025) was used to predict the ABCG protein interaction network. The interaction network was visualized using the Cytoscape software (V3.10.3) [39].

2.8. Quantitative Real-Time PCR Validation

The synthesized cDNA templates were used to perform qRT-PCR with 25 gene-specific primers (Table S8) on a ViiA7 system (ABI) using the SYBR Green I (TB Green Premix Ex Taq II, TaKaRa). The cycling conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 30 s, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s, and 60 °C for 30 s. Melt curves confirmed specificity. The 2−ΔΔCt method (n = 3 biological replicates) was used to calculate relative expression levels, and GAPDH was used as the reference gene. Error bars represented the standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical differences were analyzed by the one-way ANOVA, which was used to analyze statistical differences on the GraphPad Prism 8.0 (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of SlABCG Genes

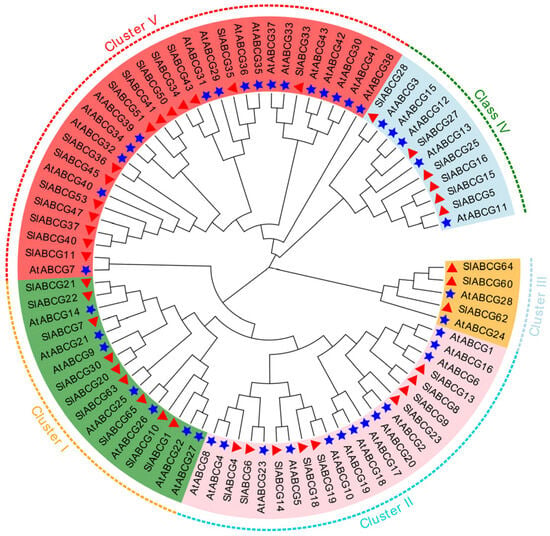

Based on previous research, we identified 41 genes belonging to the ABCG family from the tomato reference genome Solanum_lycopersicum.SL3.0 (Table S1). The lengths of proteins encoded by the tomato ABCG genes exhibited significant variation, ranging from 597 amino acids (SlABCG4) to 4249 amino acids (SlABCG50). Further analysis revealed that the molecular weights of these proteins were in the range of 66.46 kDa to 482.64 kDa, with isoelectric points distributed between 5.98 and 9.28 (Table S1). To clarify the evolutionary relationships among members of the tomato ABCG family, a phylogenetic tree was constructed in this study using full-length protein sequences of 41 tomato ABCG genes and 43 Arabidopsis ABCG genes. Phylogenetic analysis was performed via the neighbor-joining method with 1000 bootstrap replicates to assess branch reliability, and the results revealed that these ABCG family proteins could be divided into five distinct clusters (Figure 1). In all clusters, members of the tomato ABCG family showed conserved orthology, such as SlABCG8 and SlABCG9 in cluster II and SlABCG15 and SlABCG16 in cluster IV. In addition, cluster V exhibited the highest diversity, containing 16 Arabidopsis ABCG genes and 14 tomato ABCG genes (Figure 1). This phylogenetic topology indicated that the ABCG family has both lineage-specific diversification events and conserved evolutionary patterns.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic reconstruction of ABCG proteins. The evolutionary tree was obtained using the neighbor-joining method (MEGA7) with ABCG protein sequences from tomato and Arabidopsis. Bootstrap support values (1000 replicates) are displayed at branch nodes. Five-pointed stars represent Arabidopsis genes; triangles represent tomato genes.

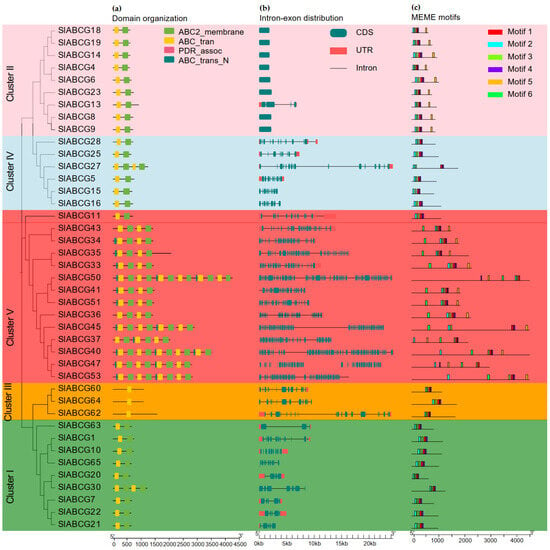

3.2. Analysis of Gene and Protein Structures of SlABCGs

An analysis of the conserved domains in ABCG transporters demonstrated that four conserved domains were present in the two complexes, among which, the first complex harbors either nucleotide-binding domains (NBDs), transmembrane domains (TMDs), or a combination of both (Figure 2a). These genes contain 1 to 58 exons and were distributed across multiple distinct chromosomes. The intron–exon distribution pattern indicates that closely related ABCG genes typically shared similar gene structures (Figure 2b). A motif analysis identified a total of six conserved motifs, and their distribution patterns were highly diverse, which verified their phylogenetic classification (Figure 2c). A MEME analysis also revealed that among the six conserved motifs, four overlap with the domains of ABC trans (NBD) and ABC membrane (TMD). Motif 2 and motif 3 belong to the ABC_trans domain, while motif 5 and motif 6 belong to the ABC2_membrane domain (Figure S1).

Figure 2.

Gene and protein structure analysis of the tomato ABCG transporter subfamily. (a) Identification of the conserved domain of SlABCG proteins. (b) Gene structure of the SlABCG genes, 5′ to 3′ direction indicates the orientation of the nucleotide sequence, and, at the bottom, the scale is the length of the nucleotides (bp). (c) Conserved motifs of the SlABCG proteins.

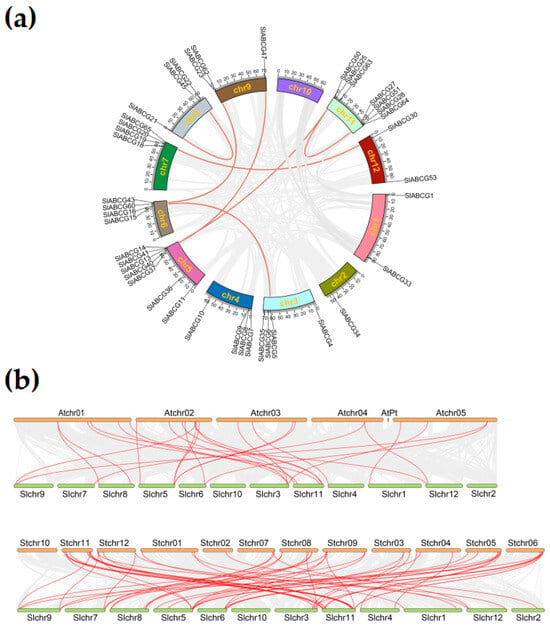

3.3. Synteny and Colinearity Analysis of SlABCG Genes

To further investigate the relationships among tomato ABCG genes, we performed a genome-wide collinearity analysis of duplication events within this family. The results revealed that the 41 SlABCG genes were unevenly distributed across 11 chromosomes, with the highest number of genes being found on chromosomes 5 and 11 (7 genes each). A total of seven segmental duplication pairs were identified in the tomato ABCG subfamily, randomly distributed across eight chromosomes (Figure 3a). This pattern suggested that segmental duplication events may have played a dominant role in driving ABCG gene expansion in the tomato genome. Furthermore, to further understand the duplication events of SlABCG genes, a collinearity map of the ABCG homologous genes among tomato, Arabidopsis, and potato was constructed. The results showed that 21 SlABCG genes formed 35 collinear gene pairs with 24 AtABCG genes, and 21 SlABCG genes formed 39 collinear gene pairs with 27 SlABCG genes (Figure 3b and Table S2). This finding contributed to exploring the evolutionary relationships among species and predicting gene functions.

Figure 3.

Gene duplication analysis of the SlABCG subfamily. (a) Synteny analysis of the tomato ABCG subfamily on different chromosomes. Different color lines represent segmental duplication pairs of SlABCG between chromosomes. (b) Synteny relationship analysis of SlABCG between tomato, potato, and Arabidopsis. The red lines represent collinear gene pairs and gray lines represent the collinear blocks.

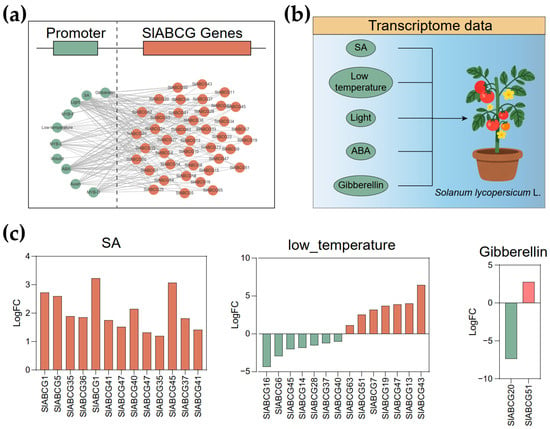

3.4. Expression Patterns of SlABCGs Under Abiotic Stress

To further elucidate the regulatory mechanism of ABCG genes, we analyzed the promoter sequences of all these genes using the PlantCARE software. A series of cis-elements associated with multiple abiotic stresses were identified, including those responsive to ABA, wound, auxin, gibberellin, light, low temperatures, and SA (Figure 4a and Figure S2). To further validate whether these abiotic stresses induce the expression of SlABCG genes, we obtained transcriptomic datasets of tomato plants treated with ABA, gibberellin, light, low temperatures, and SA from the NCBI database (Figure 4b). Subsequently, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of their expression patterns (Table S3). Differential expression analysis revealed that thirteen, seven, and one SlABCG genes were upregulated in response to SA, low-temperature, and gibberellin treatments, respectively (Figure 4c). In contrast, no SlABCG genes showed significant changes under light or ABA treatments. Intriguingly, seven and one SlABCG genes were downregulated during low-temperature and gibberellin treatments, respectively. These results suggest that SlABCG genes may play roles in tomato responses to low temperatures and SA.

Figure 4.

Expression patterns of SlABCGs under abiotic stress. (a) Cis-element prediction for the SlABCG gene. (b) The transcriptome data of tomato under different stresses, including salicylic acid (SA), low temperatures, light, gibberellin, and abscisic acid (ABA). (c) Differentially expressed SlABCG genes of tomato under the stresses of SA, low temperatures, and gibberellin.

3.5. Function of SlABCG in Tomato Under Saline–Alkali Stress

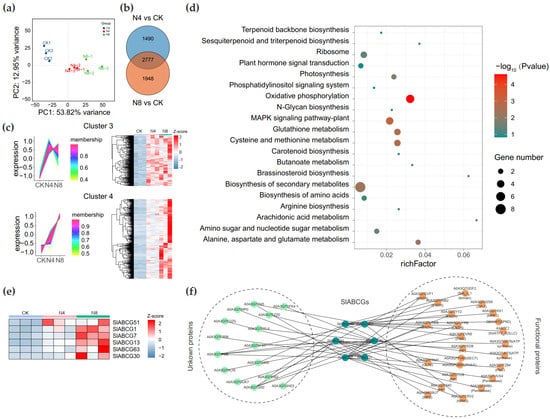

Studies have demonstrated that the ABCG family plays a crucial role in plant responses to salt stress. We performed transcriptome sequencing on saline–alkali stress-treated tomato plants. Specifically, we employed RNA-Seq technology to sequence the transcriptomes of tomato seedlings subjected to saline–alkali treatment for 0 h (control, CK), 4 h, and 8 h. This yielded 2.03 Gb of clean reads, with the percentage of Q30 bases exceeding 97.0% and the GC content being approximately 42.35% (Table S4). The correlation analysis revealed a high degree of consistency between replicate data at the same treatment time points (Figure 5a). After excluding genes with Transcripts Per Kilobase Million (TPM) < 1 in all samples, a total of 21,165 genes were retained (Table S5). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified with the criteria of FDR < 0.05 and |log2FC| ≥ 1. Compared with the control (CK), 1561; 2862 upregulated DEGs and 1216; 1863 downregulated DEGs were identified in the 4 h and 8 h groups, respectively (Table S6). A total of 2777 genes were differentially expressed in both the 4 h and 8 h groups (Figure 5b). After analyzing the expression trends of co-DEGs, four distinct expression patterns were identified (Figure S3). Among these, genes in cluster 3 and cluster 4 exhibited increased expression levels at 4 h and 8 h compared to those in the CK group (Figure 5c). The KEGG enrichment analysis revealed that genes in these two clusters were enriched in multiple pathways, including oxidative phosphorylation, the plant-specific MAPK signaling pathway, and glutathione metabolism (Figure 5d, Table S7). The two clusters contain a total of six SlABCG genes, with cluster 3 harboring one (SlABCG51) and cluster 4 containing five genes (SlABCG1, SlABCG7, SlABCG13, SlABCG63, and SlABCG30) (Figure 5e). To further characterize the functions of these six ABCG genes, we utilized the STRING database to predict their protein interaction networks. Results revealed that these ABCG proteins interact with multiple proteins. In particular, SlABCG7 exhibited interactions with 13 proteins, including peroxidases, ENTH domain-containing proteins, and cytochrome P450 enzymes (Figure 5f).

Figure 5.

Expression pattern analysis of SlABCG genes in tomato under saline–alkali stress. (a) Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of all samples. (b) The distribution of differential expression genes between N8 vs. CK and N4 vs. CK. (c) Expression trend analysis was performed using the R package TCseq and the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with sustained upregulation are displayed. (d) KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs with sustained upregulation. The size of the circles represents the gene number and from green to red represents −log10 (p value). (e) The heatmap represents the expression pattern of differential expression in SlABCG genes with sustained upregulation. (f) The String server was used to predict the interaction network of SlABCG genes. These interactions occur at the cell membrane.

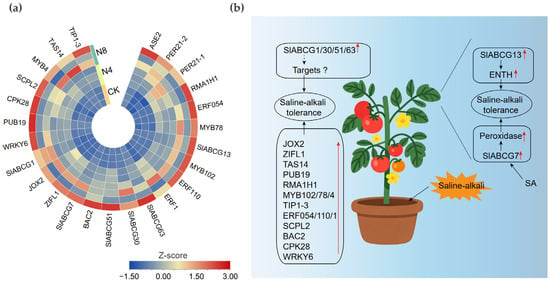

3.6. SlABCG Genes Regulating the Saline–Alkali Stress Response in Tomato

To further verify the gene response mechanisms to saline–alkali stress, we selected the upregulated SlABCG family genes, partial target genes, and other related genes for expression pattern analysis. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) results showed that all genes were upregulated during the saline–alkali stress treatment (Figure 6a and Figure S4). Transcriptome sequencing data revealed that four genes, namely SlABCG1, SlABCG30, SlABCG51, and SlABCG63, were significantly upregulated, while their predicted target genes showed no response to saline–alkali stress. This suggested that these SlABCG genes may enhance the saline–alkali tolerance of tomato by regulating other target genes. In addition, both SlABCG13 and its target gene ENTH exhibited upregulated expression patterns under saline–alkali stress, indicating that SlABCG13 might improve the saline–alkali tolerance of tomato by promoting the expression of ENTH. Notably, the SlABCG7 gene not only significantly increased the expression levels of two peroxidase genes but its own expression was also induced by salicylic acid (SA). This implies that SlABCG7 may be involved in the SA-mediated mechanism underlying the enhanced saline–alkali tolerance of tomato (Figure 6b).

Figure 6.

Verification of expression patterns and establishment of a saline–alkali tolerance model in tomato. (a) Heatmap of the relative expression levels of the upregulated genes in tomato at different times after saline–alkali treatment. Each column represents a sample, and each row represents a gene. Colors indicate standardized gene expression values (Z-score values), with blue and red denoting low and high transcript abundances, respectively. (b) A working model for tomato-responding saline–alkali tolerance. Red arrows indicate the upregulation of gene expression or protein activity.

4. Discussion

ABC transporters are a class of widely existing membrane-bound proteins, present in plants, animals, and prokaryotes [4,40,41,42]. From a phylogenetic perspective, the ABC gene family can be divided into different subfamilies, including the ABCA~ABCI subfamilies but excluding the ABCH subfamily [24,43,44]. Among them, the ABCG protein subfamily has a large number of members and plays a key role in multiple signaling pathways involved in plant responses to abiotic stress [18,22,44]. Previous studies have demonstrated that ABCG represents the largest subfamily within the plant ABC gene family, while its functional characterization remains to be addressed [2].

In this study, we identified the ABCG subfamily genes in tomato and conducted an in-depth analysis of their functional mechanisms in response to corresponding abiotic stresses in tomato. Previous studies identified 70 ABCG genes in the tomato reference genome [24]. However, using the IDs of these 70 genes, the present study retrieved only 41 ABCG genes in the new version of the tomato reference genome. This discrepancy may be attributed to the removal of false positive genes, non-functional pseudogenes, and redundantly annotated genes in the updated genome assembly. A phylogenetic analysis of the ABCG subfamily across plant lineages has revealed several intriguing insights [45]. Our evolutionary analysis classified tomato ABCG genes into five clusters based on the evolutionary relationships of Arabidopsis ABCG proteins. We hypothesize that proteins with a common ancestral origin may share similar functions. This suggests that SlABCGs clustered with Arabidopsis homologs may have certain functional similarities, which requires further verification.

Gene duplication within a single chromosome, between chromosomes, or even across the entire genome may be a major driver for the formation of genetic diversity during genome evolution [46]. Our results showed that in the tomato genome, segmental duplication events of the ABCG subfamily were relatively frequent. Furthermore, we also compared the gene duplication events of ABCG subfamily genes in the tomato genome with those in the Arabidopsis and potato genomes. A total of 35 segmental duplication pairs were identified between the tomato and Arabidopsis genomes, involving 21 SlABCG genes and 24 Arabidopsis ABCG genes. When comparing the tomato and potato genomes, 39 segmental duplication pairs were found, containing 21 SlABCG genes and 27 potato ABCG genes. The majority of the members in the ABCG transporter subfamily are generated through segmental gene duplication, which suggests that segmental duplication might be the main driving force underlying the evolution of ABCG transporters in the tomato genome.

In the process of plant response to abiotic stresses, members of the ABCG subfamily are involved in the regulation of numerous biological processes. Overexpression of the ABCG1 gene from Medicago sativa (MsABCG1) in tobacco can significantly enhance the drought tolerance of the plants, as well as increase stomatal density and reduce stomatal diameter [22]. In Cajanus cajan, low temperatures can induce the expression of the CcABCG28 gene, while drought and aluminum stress can induce the upregulated expression of the CcABCG7 gene [47]. The ABCG gene LkABCG40 from Larix kaempferi may enhance the resistance of transgenic tobacco by inhibiting the expression of WRKY genes [47]. Identifying transcriptional regulatory elements in the promoter region is a primary strategy for predicting gene function and regulation [48].

In this study, we identified multiple cis-regulatory elements that bind to the SlABCG gene promoter, such as light- and low-temperature-responsive elements, as well as ABA-, SA-, and gibberellin-responsive elements. We obtained transcriptome data of tomatoes treated with light, low temperature, ABA, SA, and gibberellin, respectively, and reanalyzed these data. Differential expression analysis revealed that SA, low temperatures, and gibberellin can induce an increase in the transcriptional level of the SlABCG gene. SA plays a key role in plant disease resistance, but research on abiotic stress is relatively scarce [49,50]. For instance, high air humidity can inhibit the SA signaling pathway and the expression of NPR1, thereby suppressing plant defense capacity [51]. Rice SA hydroxylase genes (OsSAHs) exhibit SA-catalyzing activity in vitro. The knockout of OsSAH2 and OsSAH3 enhances plant resistance to hemi-biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens, whereas the overexpression of each OsSAH gene increases plant susceptibility to these pathogens [52]. These reports indicated that the ABCG gene identified in this study—whose promoter contained SA-binding sites and which was differentially upregulated—may participate in the disease defense mechanism of tomato through the SA signaling pathway. We also found that low temperatures can induce increased transcriptional levels of seven ABCG genes. To date, there have been only a few studies on the mechanism of ABCG in plant tolerance to low temperatures. For instance, in Cajanus, low temperatures can induce the upregulated expression of CcABCG [46]. This suggested that these low temperature-induced ABCG genes, which have low-temperature binding sites in their promoters, were highly likely to be involved in plant responses to low-temperature stress, and their molecular mechanisms requires further verification. Furthermore, we found that gibberellin can induce the upregulated expression of one ABCG gene; however, the promoter region of this ABCG gene lacked gibberellin-responsive elements. Thus, the regulatory relationship between gibberellin and the SlABCG gene remains to be further explored.

Numerous studies have shown that ABCG genes play a crucial role in plant responses to salt stress. Therefore, we performed transcriptome sequencing on tomato plants subjected to saline–alkali stress. Compared with the CK group, there were 2777 common differentially expressed genes at 4 h and 8 h. Among these genes, 1563 DEGs showed a continuous increase in transcription levels during saline–alkali stress treatment. The KEGG enrichment analysis revealed that these genes are involved in multiple pathways, such as oxidative phosphorylation, MAPK signaling pathway–plant, and photosynthesis, indicating that these pathways are involved in plant responses to saline–alkali stress. There were six SlABCG genes in these continuously upregulated genes. A further interaction network analysis showed that these SlABCG proteins interact with various functional proteins, such as SlABCG7 with two genes encoding peroxidase, and SlABCG63 with MPK2. Studies have demonstrated that the WRKY107 gene in maize can regulate the expression of peroxidase (ZmPOD52) by directly binding to the promoter of maize ZmPOD52, thereby regulating the salt tolerance of maize [53]. In addition, MAPK cascades also play a key role in enhancing plant salt tolerance [54]. Under salt stress conditions, exogenous application of the MAPK phosphorylation inhibitor SB203580 reduces the levels of endogenous jasmonic acid (JA), ABA, and ethylene, while decreasing O2− and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and lowering the activity of antioxidant enzymes [55]. These findings suggested that SlABCG may form an interaction network with the aforementioned functional proteins to jointly regulate plant tolerance to salt stress. This study provides valuable insights for in-depth investigations of the response mechanisms of the tomato ABCG family to abiotic stress, which is of great significance for improving tomato tolerance and yield.

The present DEG analysis provides only an averaged view of transcriptional changes, which may obscure cell-type-specific and spatially resolved responses. Plant organ-level outcomes emerge from integrated cell-to-cell communication, and the effect of a treatment strongly depends on its position within the hormetic window. Therefore, while our results offer a useful overview, future studies should carefully define treatment conditions and employ more precise in situ approaches to capture the complex spatiotemporal dynamics of hormetic responses.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we systematically characterized the ABCG gene family using bioinformatics tools, encompassing analyses of evolutionary relationships, gene structures and protein-conserved motifs, chromosomal distribution, the prediction of cis-acting elements, and expression changes in each gene under different treatments. The 41 identified ABCG transporter genes could be divided into five clusters, and variations in their gene structural characteristics supported the evolutionary relationships revealed by phylogeny. The prediction of cis-acting elements indicated that SlABCG genes might be regulated by various stresses, which was further confirmed by transcriptome data showing that SlABCGs were regulated by gibberellin, low temperatures, and SA. The transcriptome sequencing analysis of tomato saline–alkali stress revealed that six SlABCG genes had the potential to regulate plant responses to saline–alkali stress, and the interaction network prediction demonstrated that these genes regulated multiple saline–alkali stress-related genes such as peroxidase and MPK2. This information was crucial for enhancing tomato breeding for resilience to short-term hydroponic failures under accidental saline–alkali stress.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/genes17010019/s1. Figure S1: Conserved protein sequences of 6 motifs identified in the SlABCG subfamily. Motif scans and sequence logos were generated in the MEME server. Figure S2: Cis-element prediction of the SlABCG gene. Figure S3: Expression trend analysis was performed using the R package TCseq. Figure S4: Gene expression of 6 SlABCG genes, 2 targets, and 17 other key genes in tomato at different times after saline–alkali treatment. Table S1: Characteristics of SlABCG genes and the encoded proteins. Table S2: ABCG homologous genes between tomato and Arabidopsis or potato. Table S3: The expression patterns of tomato genes under abiotic stress. Table S4: RNA-seq analysis of tomato under saline–alkali stress. Table S5: Expression levels of tomato genes. Table S6: Differentially expressed analysis of tomato under saline–alkali stress. Table S7: KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of common DEGs between N4 vs. CK and N8 vs. CK. Table S8: The gene-specific primers.

Author Contributions

Y.L., L.G., and R.X. led and coordinated the project. Y.L. and W.G. performed the saline–alkali treatment experiments on tomatoes. L.G. and G.L. conducted bioinformatics analyses. L.G. and Y.L. wrote the manuscript. R.X., W.C., and H.J. revised the manuscript. All authors read and agreed to the final manuscript. L.G. and R.X. are corresponding authors and are responsible for all contact and correspondence. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32372643), the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong of China (ZR2023QC089), and the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong of China (ZR2024QC019).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Eldridge, B.M.; Larson, E.R.; Mahony, L.; Clark, J.; Akhtar, J.; Noleto-Dias, C.; Ward, J.L.; Grierson, C.S. A highly conserved ABCG transporter mediates root-soil cohesion in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2025, 198, kiaf193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrier, P.J.; Bird, D.; Burla, B.; Dassa, E.; Forestier, C.; Geisler, M.; Klein, M.; Kolukisaoglu, U.; Lee, Y.; Martinoia, E.; et al. Plant ABC proteins—A unified nomenclature and updated inventory. Trends Plant Sci. 2008, 13, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Li, Y.; Zhao, L.; Hou, Z.; Yan, M.; Hu, B.; Liu, Y.; Azam, S.M.; Zhang, Z.; Rahman, Z.U.; et al. Genome-wide identification and expression profiling of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter gene family in pineapple (Ananas comosus (L.) Merr.) reveal the role of AcABCG38 in pollen development. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, O.; Bouige, P.; Forestier, C.; Dassa, E. Inventory and comparative analysis of rice and Arabidopsis ATP-binding cassette (ABC) systems. J. Mol. Biol. 2004, 343, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; You, F.M.; Datla, R.; Ravichandran, S.; Jia, B.; Cloutier, S. Genome-wide identification of ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporter and heavy metal associated (HMA) gene families in flax (Linum usitatissimum L.). BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Ortiz, C.; Dutta, S.K.; Natarajan, P.; Peña-Garcia, Y.; Abburi, V.; Saminathan, T.; Nimmakayala, P.; Reddy, U.K. Genome-wide identification and gene expression pattern of ABC transporter gene family in Capsicum spp. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0215901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, A.K.; Choi, J.; Rabbee, M.F.; Baek, K.H. In silico genome-wide analysis of the ATP-binding cassette transporter gene family in soybean (Glycine max L.) and their expression profiling. Biomed. Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 8150523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.N.; Moon, S.; Jung, K.H. Genome-wide expression analysis of rice ABC transporter family across spatio-temporal samples and in response to abiotic stresses. J. Plant Physiol. 2014, 171, 1276–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, G.; Wu, T.; Zhang, X.; Xu, X.; Han, Z.; Wang, Y. Genome-wide identification and characterization of ABC transporters in nine rosaceae species identifying MdABCG28 as a possible cytokinin transporter linked to dwarfing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francisco, R.M.; Regalado, A.; Ageorges, A.; Burla, B.J.; Bassin, B.; Eisenach, C.; Zarrouk, O.; Vialet, S.; Marlin, T.; Chaves, M.M.; et al. ABCC1, an ATP binding cassette protein from grape berry, transports anthocyanidin 3-O-Glucosides. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 1840–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, C.; Chen, L.; Zaripov, T.; Zhan, D.; Weng, J.; Lin, Y.; Lai, Z.; Guo, Y. Integrated Transcriptome, microRNA, and Phytochemical Analyses Reveal Roles of Phytohormone Signal Transduction and ABC Transporters in Flavor Formation of Oolong Tea (Camellia sinensis) during Solar Withering. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 12749–12767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banasiak, J.; Jasiński, M. ATP-binding cassette transporters in nonmodel plants. New Phytol. 2022, 233, 1597–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kos, V.; Ford, R.C. The ATP-binding cassette family: A structural perspective. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2009, 66, 3111–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewart, G.D.; Cannell, D.; Cox, G.B.; Howells, A.J. Mutational analysis of the traffic ATPase (ABC) transporters involved in uptake of eye pigment precursors in Drosophila melanogaster. Implications for structure-function relationships. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 10370–10377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarr, P.T.; Tarling, E.J.; Bojanic, D.D.; Edwards, P.A.; Baldán, A. Emerging new paradigms for ABCG transporters. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1791, 584–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghi, L.; Kang, J.; Ko, D.; Lee, Y.; Martinoia, E. The role of ABCG-type ABC transporters in phytohormone transport. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2015, 43, 924–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Shi, J.; Liang, W.; Zhang, D. ATP binding cassette G transporters and plant male reproduction. Plant Signal Behav. 2016, 11, e1136764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Hu, Y.; Tang, L.; Du, Y.; Mao, R.; Sheng, X.; Liu, H.; Liu, X.; Zhao, B.; Lei, D. ABCG transporters in the adaptation of rice to salt stresses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.Y.; Jin, J.Y.; Alejandro, S.; Martinoia, E.; Lee, Y. Overexpression of AtABCG36 improves drought and salt stress resistance in Arabidopsis. Physiol. Plant. 2010, 139, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, L.; Ma, Q.; Du, J.; Yu, M.; Li, F.; Luan, J.; Jiang, J.; Li, H. Preliminary classification of the ABC transporter family in Betula halophila and expression patterns in response to exogenous phytohormones and abiotic stresses. Forests 2019, 10, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Liu, X.; Yu, S.; Liu, J.; Jiang, L.; Lu, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, S. The maize ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter ZmMRPA6 confers cold and salt stress tolerance in plants. Plant Cell Rep. 2023, 43, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Yang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, B.; Liu, T.; Shao, Z.; Li, Y.; Yang, P.; An, J.; Cao, Y. MsABCG1, ATP-binding cassette G transporter from Medicago sativa, improves drought tolerance in transgenic Nicotiana tabacum. Physiol. Plant. 2024, 176, e14446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Kilambi, H.V.; Liu, J.; Bar, H.; Lazary, S.; Egbaria, A.; Ripper, D.; Charrier, L.; Belew, Z.M.; Wulff, N.; et al. ABA homeostasis and long-distance translocation are redundantly regulated by ABCG ABA importers. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabf6069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ofori, P.A.; Mizuno, A.; Suzuki, M.; Martinoia, E.; Reuscher, S.; Aoki, K.; Shibata, D.; Otagaki, S.; Matsumoto, S.; Shiratake, K. Genome-wide analysis of ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporters in tomato. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Xiong, L.; Shi, H.; Yang, S.; Herrera-Estrella, L.R.; Xu, G.; Chao, D.Y.; Li, J.; Wang, P.Y.; Qin, F.; et al. Plant abiotic stress response and nutrient use efficiency. Sci. China Life Sci. 2020, 63, 635–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.L.; Zhang, S.X.; Ding, F. Melatonin mitigates chilling-induced oxidative stress and photosynthesis inhibition in tomato plants. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertea, M.; Kim, D.; Pertea, G.M.; Leek, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. Transcript-level expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with HISAT, StringTie and Ballgown. Nat. Protoc. 2016, 11, 1650–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patro, R.; Duggal, G.; Love, M.I.; Irizarry, R.A.; Kingsford, C. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 417–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.D.; McCarthy, D.J.; Smyth, G.K. edgeR: A Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Tamura, K.; Nei, M. MEGA: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis software for microcomputers. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 1994, 10, 189–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, B.; Gao, S.; Lercher, M.J.; Hu, S.; Chen, W.H. Evolview v3: A webserver for visualization, annotation, and management of phylogenetic trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W270–W275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, A.Y.; Zhu, Q.H.; Chen, X.; Luo, J.C. GSDS: A gene structure display server. Yi Chuan 2007, 29, 1023–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, T.L.; Boden, M.; Buske, F.A.; Frith, M.; Grant, C.E.; Clementi, L.; Ren, J.; Li, W.W.; Noble, W.S. MEME SUITE: Tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, W202–W208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lescot, M.; Déhais, P.; Thijs, G.; Marchal, K.; Moreau, Y.; Van De Peer, Y.; Rouzé, P.; Rombauts, S. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Mao, X.; Huang, J.; Ding, Y.; Wu, J.; Dong, S.; Kong, L.; Gao, G.; Li, C.Y.; Wei, L. KOBAS 2.0: A web server for annotation and identification of enriched pathways and diseases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, W316–W322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.Y.; Park, J.; Eisenach, C.; Maeshima, M.; Lee, Y.; Martinoia, E. ABC transporters and heavy metals. In Plant ABC Transporters; Geisler, M., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliou, V.; Vasiliou, K.; Nebert, D.W. Human ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter family. Hum. Genom. 2009, 3, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- How, S.S.; Nathan, S.; Lam, S.D.; Chieng, S. ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters: Structures and roles in bacterial pathogenesis. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2024, 26, 58–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Fernández, R.; Davies, T.G.; Coleman, J.O.; Rea, P.A. The Arabidopsis thaliana ABC protein superfamily, a complete inventory. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 3023130244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, L.; Zhang, J.; Chen, H.; Luo, H. Genome-wide analysis of ATP-binding cassette transporter provides insight to genes related to bioactive metabolite transportation in Salvia miltiorrhiza. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.H.; Jang, S.; Choi, B.Y.; Hong, D.; Choi, D.S.; Choi, S.; Kim, H.; Han, S.K.; Kim, S.; Kim, M.S.; et al. Phylogenetic analysis of ABCG subfamily proteins in plants: Functional clustering and coevolution with ABCGs of pathogens. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 172, 1422–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Wang, J.; Lin, W.; Li, S.; Li, H.; Zhou, J.; Ni, P.; Dong, W.; Hu, S.; Zeng, C.; et al. The genomes of Oryza sativa: A history of duplications. PLoS Biol. 2005, 3, e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.; Li, H.; Song, Z.; Dong, B.; Cao, H.; Liu, T.; Du, T.; Yang, W.; Amin, R.; Wang, L.; et al. The functional analysis of ABCG transporters in the adaptation of pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan) to abiotic stresses. PeerJ 2021, 9, e10688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, W.A.; Lu, Z.; Ji, L.; Marand, A.P.; Ethridge, C.L.; Murphy, N.G.; Noshay, J.M.; Galli, M.; Mejía-Guerra, M.K.; Colomé-Tatché, M.; et al. Widespread long-range cis-regulatory elements in the maize genome. Nat. Plants 2019, 5, 1237–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, T.P.; Uknes, S.; Vernooij, B.; Friedrich, L.; Weymann, K.; Negrotto, D.; Gaffney, T.; Gut-Rella, M.; Kessmann, H.; Ward, E.; et al. A central role of salicylic acid in plant disease resistance. Science 1994, 266, 1247–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalpani, N.; Raskin, I. Salicylic acid: A systemic signal in induced plant disease resistance. Trends Microbiol. 1993, 1, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, L.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Hao, G.; Zhong, W.; Wan, S.; Xin, X.F. High air humidity dampens salicylic acid pathway and NPR1 function to promote plant disease. EMBO J. 2023, 42, e113499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B.; Wang, H.; Yang, C.; Wang, L.; Qi, L.; Guo, Z.; Chen, X. Salicylic acid is required for broad-spectrum disease resistance in rice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, R.; Yan, H.; Zhu, X.; Fang, X.; Zhao, D.; Zhang, X.; Min, Y.; Ma, Z.; Ma, Q. ZmWRKY107 modulates salt tolerance in maize plants by regulating ZmPOD52 expression. Planta 2025, 262, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Ding, Y.; Yang, Y.; Song, C.; Wang, B.; Yang, S.; Guo, Y.; Gong, Z. Protein kinases in plant responses to drought, salt, and cold stress. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 53–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Feng, L.; Liu, Y.; Liao, W. Mitogen-activated protein kinase is involved in salt stress response in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) seedlings. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.