Statistical Genetics of DMD Gene Mutations in a Kazakhstan Cohort: MLPA/NGS Variant Validation and Genotype–Phenotype Modelling

Abstract

1. Introduction

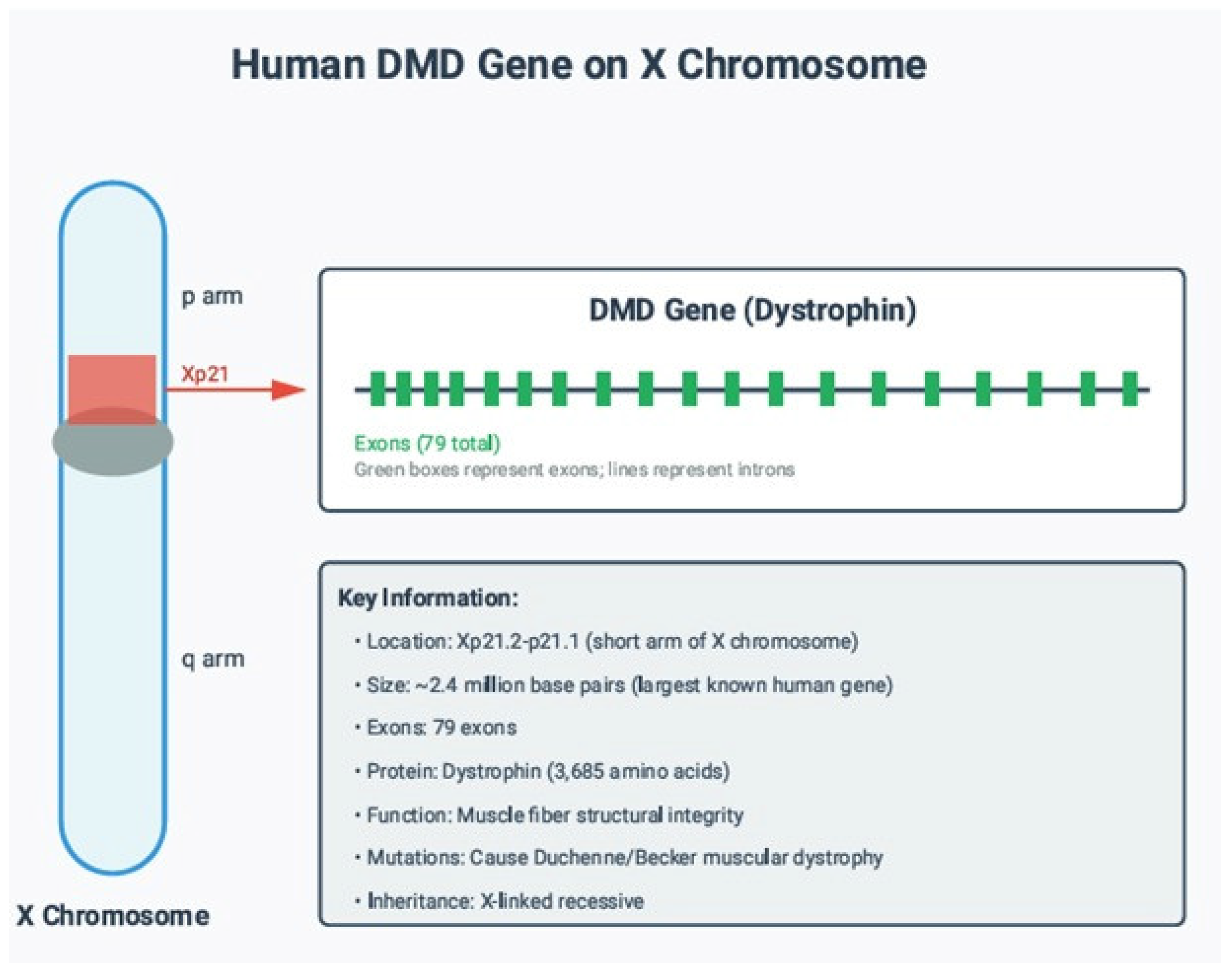

1.1. Normal Function of the DMD Gene Product

1.2. Pathogenic Mechanism of DMD Mutations

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Study Population and Clinical Data Collection

- age at diagnosis;

- age at last follow-up;

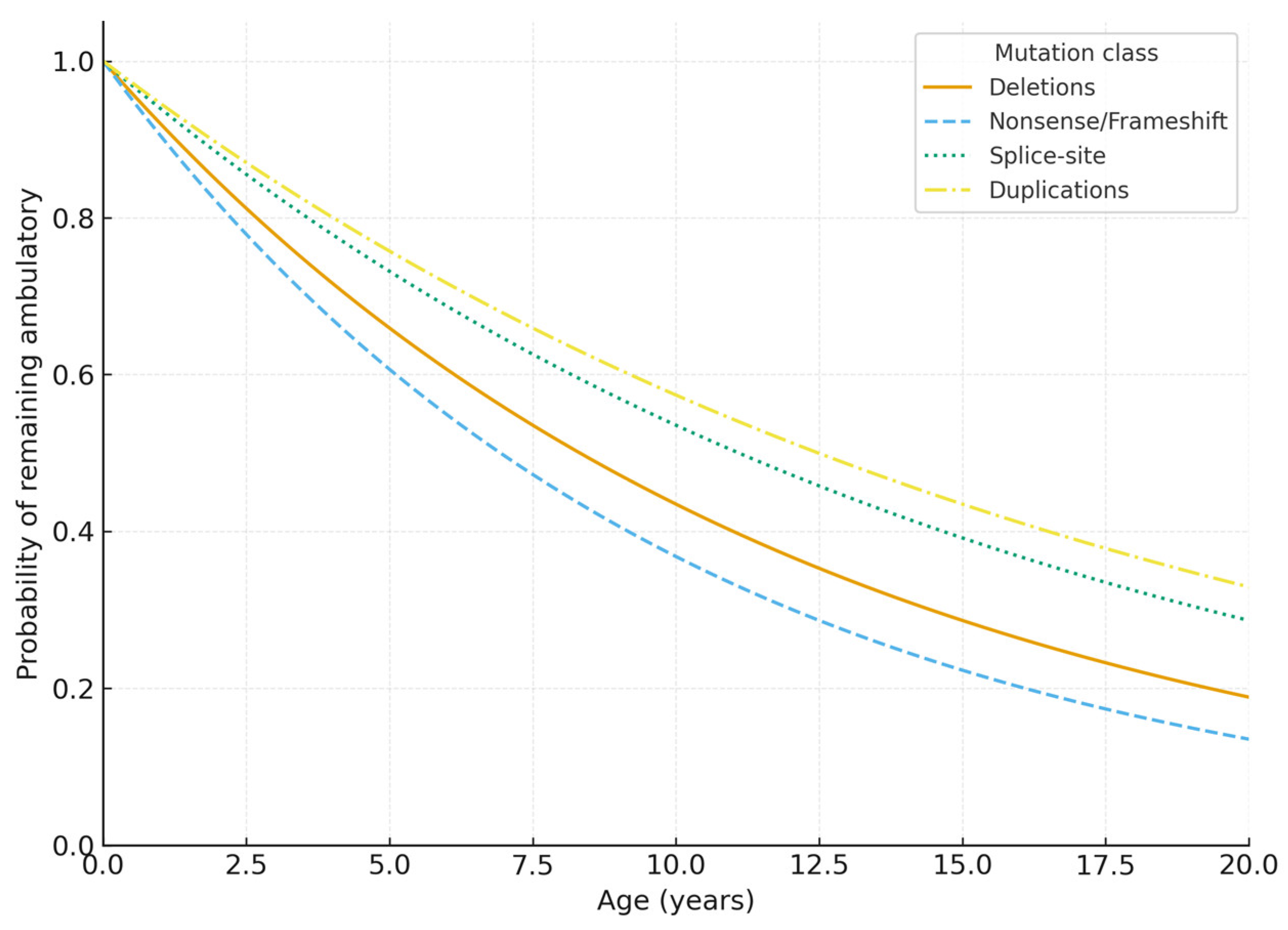

- ambulatory status (ambulatory vs. loss of ambulation);

- age at loss of ambulation (LOA), when applicable;

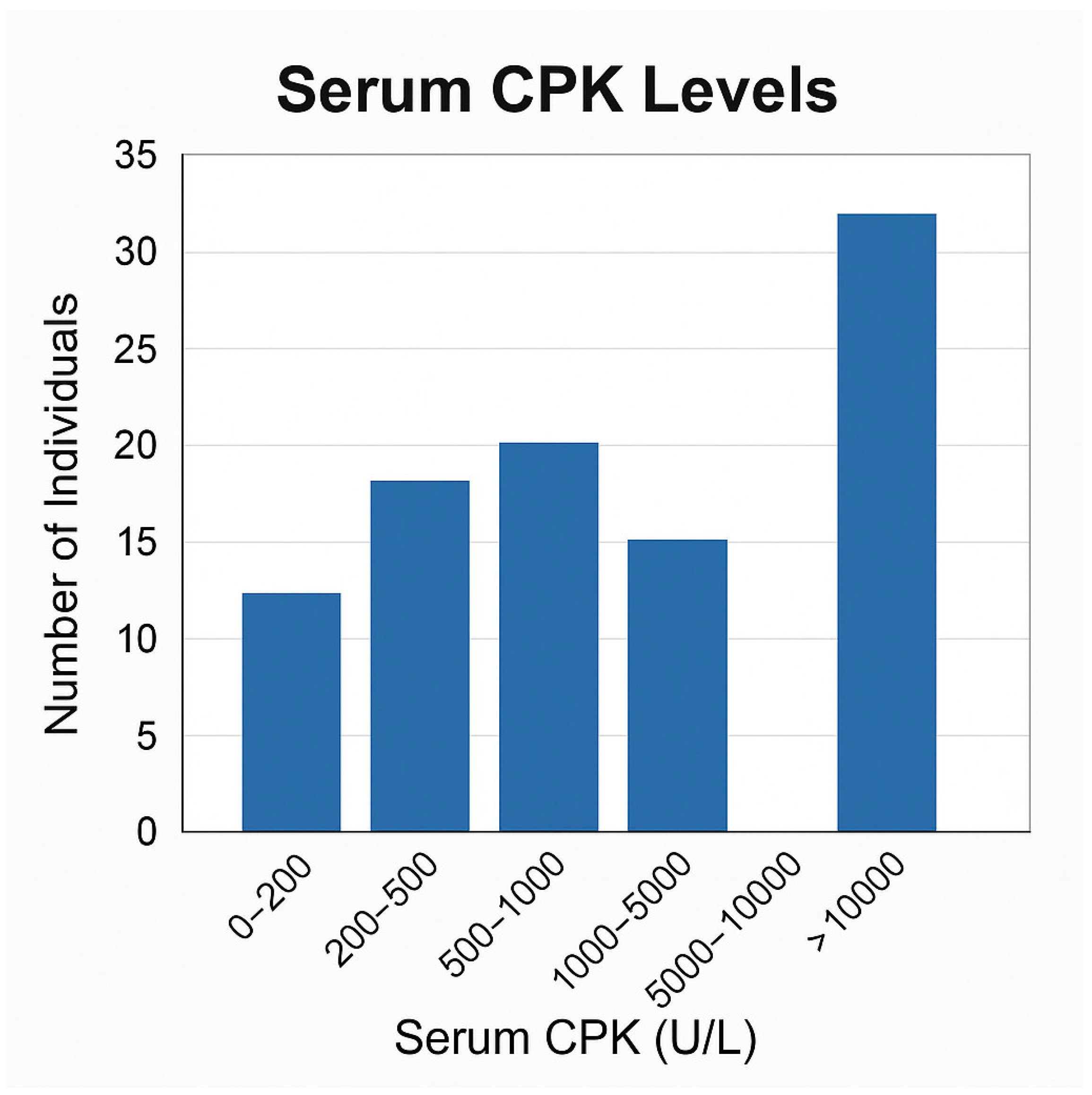

- serum creatine phosphokinase (CPK) levels;

- presence of skeletal or orthopaedic complications (when available).

2.3. Genetic Testing and Variant Validation

2.3.1. MLPA Analysis for Exon-Level CNVs

- deletion of exon 51

- deletion of exons 53–55

- deletion of exon 45

- deletion of exons 45–50

- deletion of exons 22–44

- All variants listed above were validated and classified by CENTOGENE GmbH (Rostock, Germany), a CAP/CLIA-accredited laboratory.

2.3.2. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) for Point Variants

- nonsense variant DMD c.3145A>T (p.Lys1049*) (Abylai Maratov)

- frameshift variant c.2579dup (p.Ser861Ilefs*7) (Madiyar Guder)

2.4. Variant Classification and Annotation

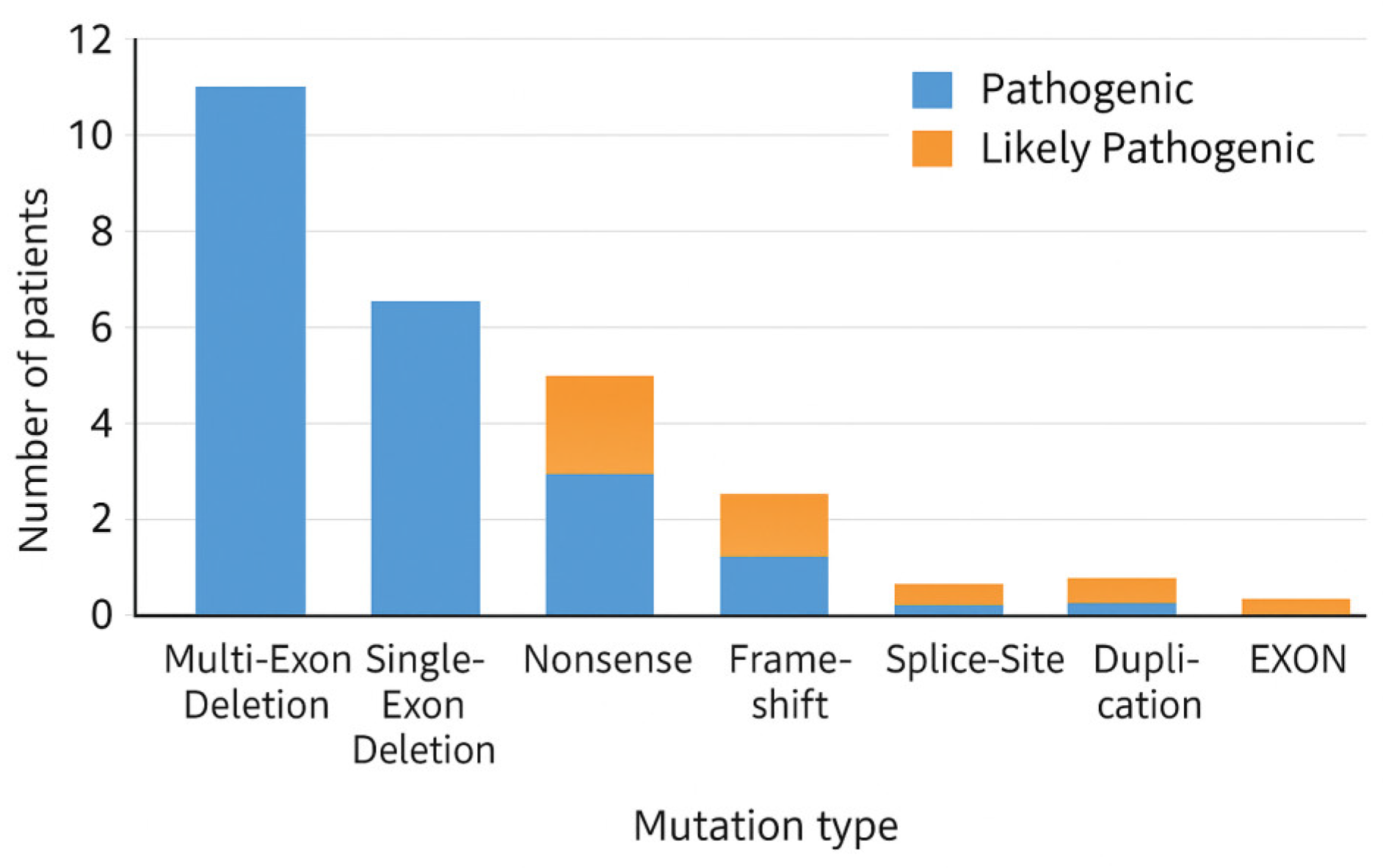

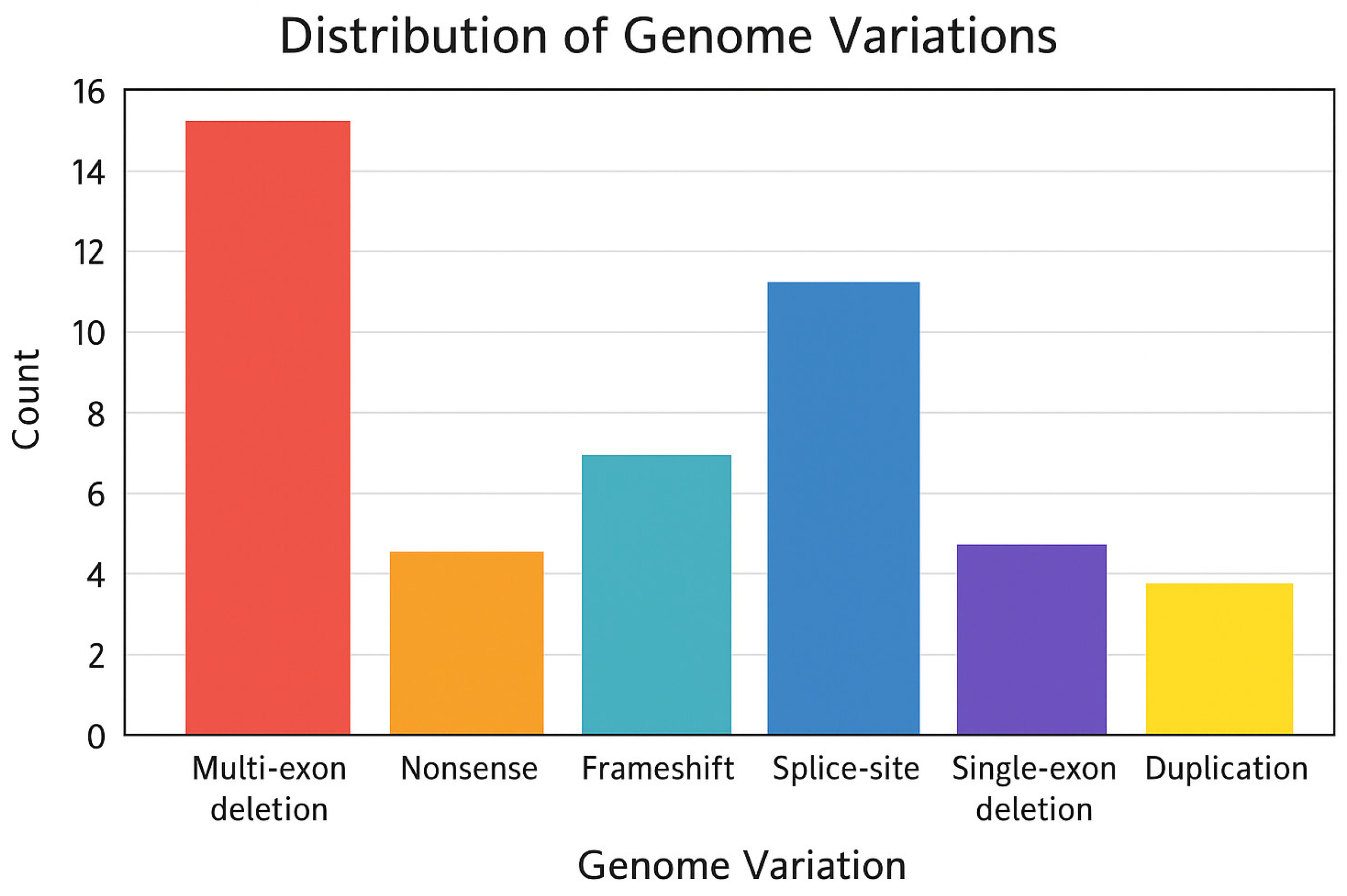

- mutation class (multi-exon deletion, single-exon deletion, nonsense, frameshift, splice-site, duplication);

- exon start and exon end coordinates;

- out-of-frame vs. in-frame effect based on the classical reading-frame rule [7];

- involvement in the deletion hotspot (exons 44–55) [5];

- recurrence (present in ≥2 unrelated patients);

- eligibility for exon-skipping therapies (exons 45, 51, 53) or stop-codon readthrough.

2.5. Data Engineering for Statistical Genetics Modelling

- Binary hotspot variable: 1 = mutation involving exons 44–55;

- Frame effect: 1 = out-of-frame, 0 = in-frame;

- Severity variable: 1 = loss of ambulation ≤12 years, 0 = ambulatory or later LOA;

- CPK categories (<5000, 5000–10,000, >10,000 U/L);

- Therapeutic relevance: 1 = exon-skipping candidate, 0 = non-candidate.

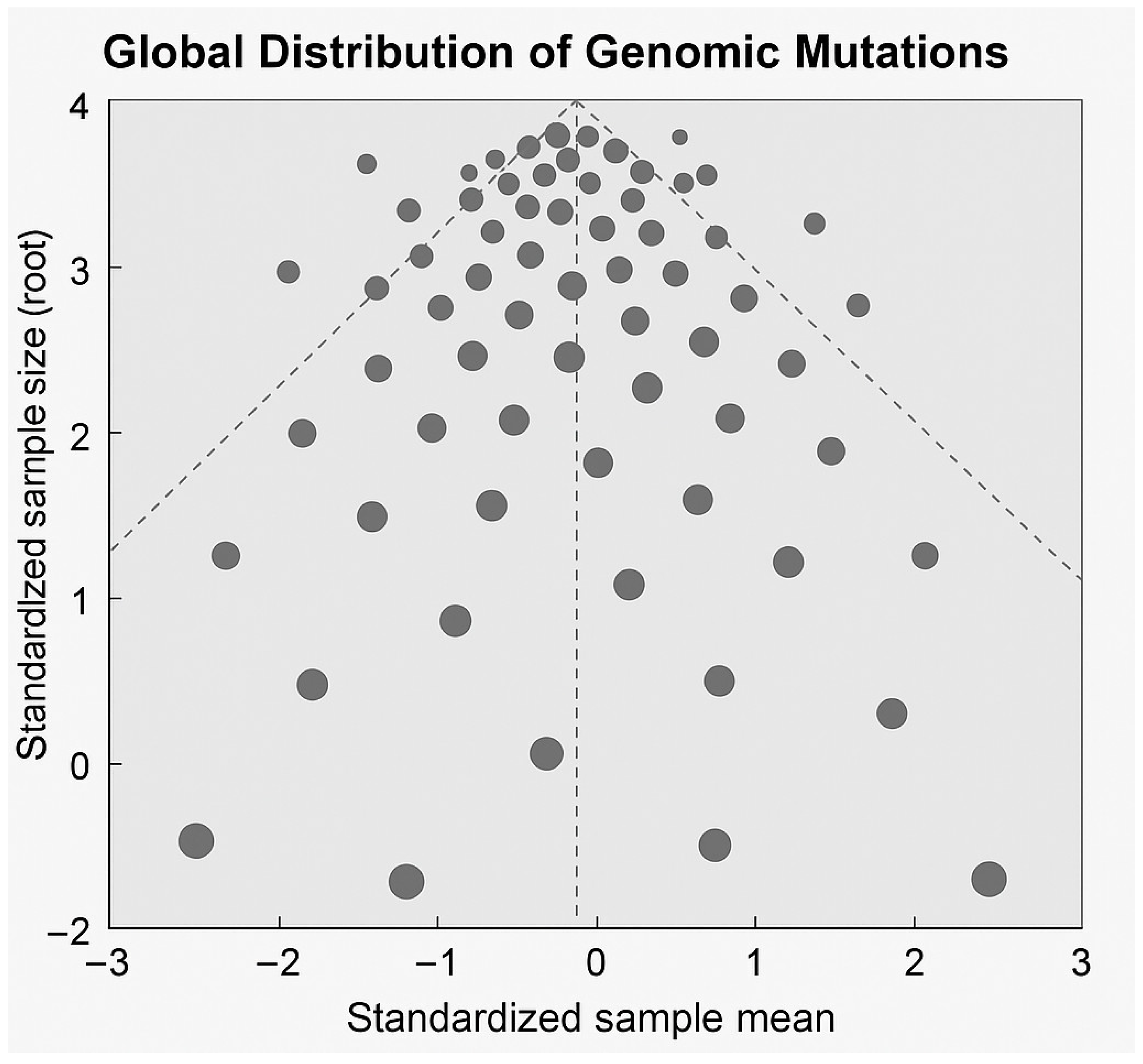

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.7. Data Availability

2.8. Generative AI Use Disclosure

3. Results

3.1. Cohort Characteristics

Clinical Variables

3.2. Phenotype

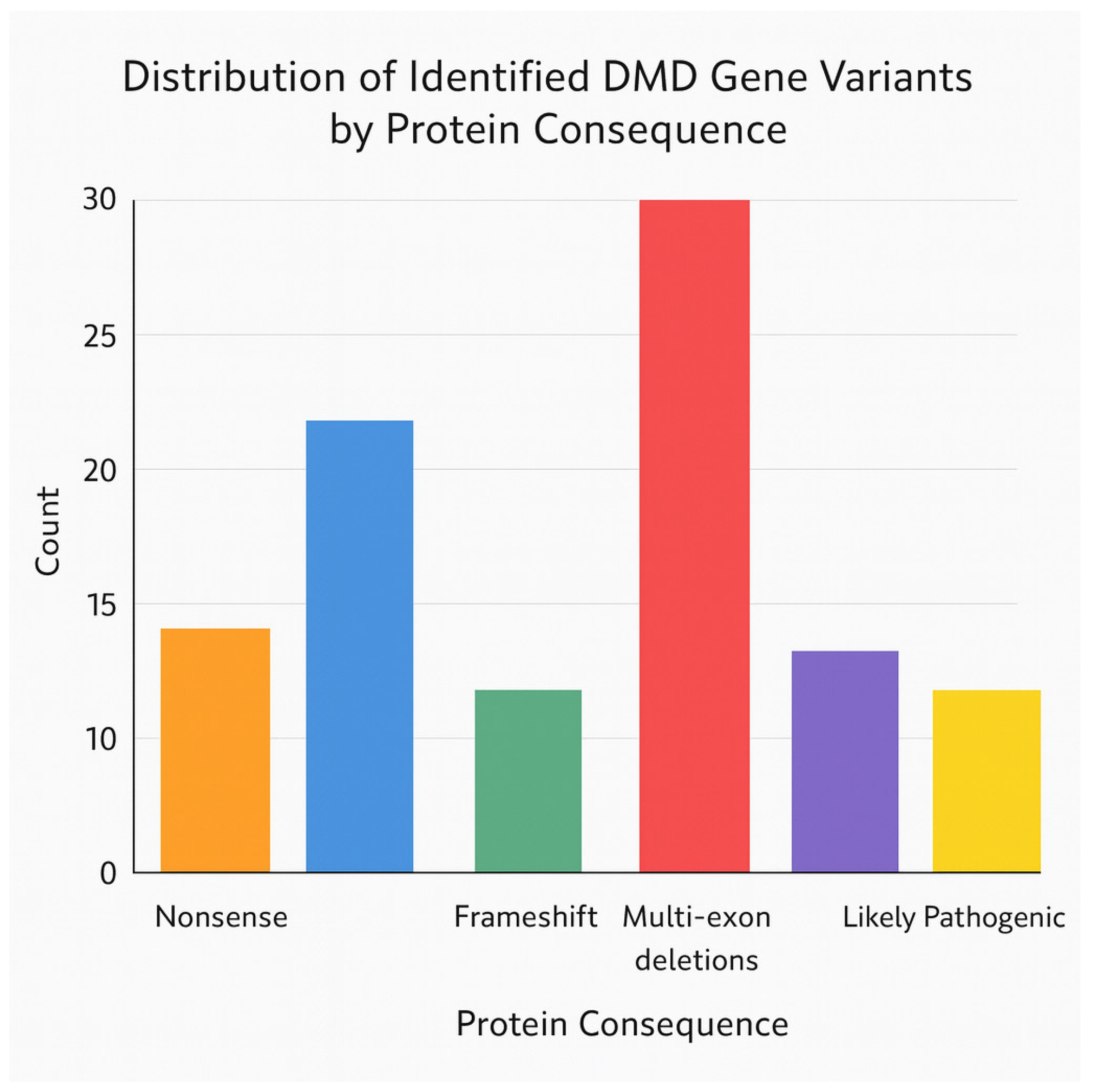

3.3. Genotype

3.4. Comparison with Phenotype

4. Discussion

- Exon skipping (45/51/53): 30 patients”

- “Stop-codon readthrough: 15 patients”

- “Gene replacement (micro-dystrophin): 25 patients”

- “Gene editing (exon rescue): 25 patients”

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACMG | American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics |

| BMD | Becker muscular dystrophy |

| CAP | College of American Pathologists |

| CK/CPK | Creatine kinase/Creatine phosphokinase |

| CLIA | Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments |

| cDNA | Complementary DNA |

| DMD | Duchenne muscular dystrophy/DMD gene |

| gDNA | Genomic DNA |

| HGMD | Human Gene Mutation Database |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| KM | Kaplan–Meier |

| LOA | Loss of ambulation |

| MLPA | Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification |

| NGS | Next-generation sequencing |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

References

- Koenig, M.; Hoffman, E.P.; Bertelson, C.J.; Monaco, A.P.; Feener, C.; Kunkel, L.M. Complete cloning of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) cDNA and preliminary genomic organization of the DMD gene. Cell 1987, 50, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, E.P.; Brown, R.H.; Kunkel, L.M. Dystrophin: The protein product of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy locus. Cell 1987, 51, 919–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aartsma-Rus, A.; Ginjaar, I.B.; Bushby, K. The importance of genetic diagnosis for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J. Med. Genet. 2016, 53, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emery, A.E.H. The muscular dystrophies. Lancet 2002, 359, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bladen, C.L.; Salgado, D.; Monges, S.; Foncuberta, M.E.; Kekou, K.; Kosma, K.; Dawkins, H.; Lamont, L.; Roy, A.J.; Chamova, T.; et al. The TREAT-NMD DMD Global Database: Analysis of more than 7,000 Duchenne muscular dystrophy mutations. Hum. Mutat. 2015, 36, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeshima, Y.; Yagi, M.; Okizuka, Y.; Awano, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yamauchi, Y.; Nishio, H.; Matsuo, M. Mutation spectrum of the dystrophin gene in Japanese patients with Duchenne/Becker muscular dystrophy. Hum. Genet. 2010, 127, 665–674. [Google Scholar]

- Monaco, A.P.; Bertelson, C.J.; Liechti-Gallati, S.; Moser, H.; Kunkel, L.M. An explanation for the phenotypic differences between patients bearing partial deletions of the DMD locus. Genomics 1988, 2, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimowski, J.; Cegielska, J.; Rzońca, T.; Ryniewicz, B.; Kaczorowska, M.; Zaremba, J.; Kostera-Pruszczyk, A.; Jędrzejowska, M.; Fidziańska, A.; Hausmanowa-Petrusewicz, I.; et al. Phenotype variability in dystrophinopathies: Exceptions to the reading-frame rule. Neurol. Neurochir. Pol. 2020, 54, 181–190. [Google Scholar]

- Flanigan, K.M. Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophies. Neurol. Clin. 2014, 32, 671–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, L.; Pegoraro, E. The “reading-frame rule” in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: Still valid? Neuromuscul. Disord. 2018, 28, 711–716. [Google Scholar]

- White, S.; Aartsma-Rus, A.; Flanigan, K.; Weiss, R.; Kneppers, A.; Lalic, T.; Janson, A.; Ginjaar, H.; Breuning, M.; Dunnen, J.D. Duplications in the DMD gene. Hum. Mutat. 2006, 27, 938–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ankala, A.; Kohn, J.N.; Hegde, S. Dystrophinopathies: Clinical and genetic testing strategies. Neurol. Genet. 2015, 1, e5. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, K.R.Q.; Sheri, R.; Yokota, T. Exon skipping applications in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6220. [Google Scholar]

- Aartsma-Rus, A.; Straub, V.; Hemmings, R.; Haas, M.; Schlosser-Weber, G.; Stoyanova-Beninska, V.; Mercuri, E.; Muntoni, F.; Sepodes, B.; Vroom, E.; et al. Development of exon skipping therapies for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: A critical review. Lancet Neurol. 2017, 16, 541–553. [Google Scholar]

- Mendell, J.R.; Sahenk, Z.; Lehman, K.; Nease, C.; Lowes, L.P.; Miller, N.F.; Iammarino, M.A.; Alfano, L.N.; Nicholl, A.; Al-Zaidy, S.; et al. Assessment of the safety and efficacy of ataluren for nonsense mutation DMD. Lancet 2013, 381, 451–457. [Google Scholar]

- Bushby, K.; Finkel, R.; Birnkrant, D.J.; Case, L.E.; Clemens, P.R.; Cripe, L.; Kaul, A.; Kinnett, K.; McDonald, C.; Pandya, S.; et al. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 1. Lancet Neurol. 2010, 9, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouten, J.P.; McElgunn, C.J.; Waaijer, R.; Zwijnenburg, D.; Diepvens, F.; Pals, G. MLPA: A novel multiplex PCR method for detection of deletions/duplications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, e57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants (ACMG-AMP). Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balding, D.J. A tutorial on statistical genetics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2006, 7, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goeman, J.J.; Solari, A. Multiple testing and survival analysis. Stat. Med. 2014, 33, 1946–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaidarov, S.; Hejran, A.B.; Moldakaryzova, A.; Izmailova, S.; Nurgaliyeva, B.; Beisenova, A.; Mustafaeva, A.; Nurzhanova, K.; Belova, Y.; Satbayeva, E.; et al. An Anti-HIV Drug Is Highly Effective Against SARS-CoV-2 In Vitro and Has Potential Benefit for Long COVID Treatment. Viruses 2025, 17, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.Y.; Lee, J.W.; Suh, M.R.; Choi, W.A.; Kang, S.W.; Oh, H.J. Correlation of Serum Creatine Kinase Level With Pulmonary Function in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Ann. Rehabil. Med. 2017, 41, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.-C.; Peng, Y.-S.; He, J.-B. Changes of serum creatine kinase levels in children with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi 2008, 10, 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Zatz, M.; Rapaport, D.; Vainzof, M.; Passos-Bueno, M.R.; Bortolini, E.R.; Pavanello, R.d.C.M.; Peres, C.A. Serum creatine-kinase (CK) and pyruvate-kinase (PK) activities in Duchenne (DMD) as compared with Becker (BMD) muscular dystrophy. J. Neurol. Sci. 1991, 102, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanigan, K.M.; Ceco, E.; Lamar, K.; Kaminoh, Y.; Dunn, D.M.; Mendell, J.R.; King, W.M.; Pestronk, A.; Florence, J.M.; Mathews, K.D.; et al. LTBP4 genotype predicts age of ambulatory loss in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Ann. Neurol. 2013, 73, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegoraro, E.; Hoffman, E.; Piva, L.; Gavassini, B.; Cagnin, S.; Ermani, M.; Bello, L.; Soraru, G.; Pacchioni, B.; Bonifati, M.D.; et al. SPP1 genotype is a determinant of disease severity in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurology 2011, 76, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosac, A.; Pesovic, J.; Radenkovic, L.; Brkusanin, M.; Radovanovic, N.; Djurisic, M.; Radivojevic, D.; Mladenovic, J.; Ostojic, S.; Kovacevic, G.; et al. LTBP4, SPP1, and CD40 Variants: Genetic Modifiers of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Analyzed in Serbian Patients. Genes 2022, 13, 1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, L.; Flanigan, K.M.; Weiss, R.B.; Dunn, D.M.; Swoboda, K.J.; Gappmaier, E.; Howard, M.T.; Sampson, J.B.; Bromberg, M.B.; Butterfield, R.; et al. Association Study of Exon Variants in the NF-κB and TGFβ Pathways Identifies CD40 as a Modifier of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2016, 99, 1163–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogarth, M.W.; Houweling, P.J.; Thomas, K.C.; Gordish-Dressman, H.; Bello, L.; Pegoraro, E.; Hoffman, E.P.; Head, S.I.; North, K.N. Evidence for ACTN3 as a genetic modifier of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, A.M.; Hammers, D.W.; Triplett, W.T.; Kim, S.; Forbes, S.C.; Willcocks, R.J.; Daniels, M.J.; Senesac, C.R.; Lott, D.J.; Arpan, I.; et al. Evaluating Genetic Modifiers of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Disease Progression Using Modeling and MRI. Neurology 2022, 99, e2406–e2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, A.-M.; Turner, C.; Astin, R.; Bianchi, S.; Bourke, J.; Cunningham, V.; Edel, L.; Edwards, C.; Farrant, P.; Heraghty, J.; et al. Development of respiratory care guidelines for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Thorax 2024, 79, 476–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, T.I.; Raucci, F.J.; Salloum, F.N. Cardiovascular Disease in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sales, T.L.S.; Pereira, D.N.; Gomes, V.M.R.; de Aguiar, G.G.; Marcolino, M.S. Efficacy of tenofovir on clinical outcomes of COVID-19: A review of clinical trials. BMC Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Total number of genetically confirmed patients (N) | 30 |

| Sex | 100% male |

| Variant type | Deletions 66.7%; SNV 30.0%; Duplications 3.3% |

| Hotspot region | Exons 45–55 |

| Mutation-negative cases (MLPA) | 2 (not included in primary cohort) |

| Study design | Retrospective cohort |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Moldakaryzova, A.; Dautov, D.; Khaidarov, S.; Ossikbayeva, S.; Kaidarova, D. Statistical Genetics of DMD Gene Mutations in a Kazakhstan Cohort: MLPA/NGS Variant Validation and Genotype–Phenotype Modelling. Genes 2026, 17, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010020

Moldakaryzova A, Dautov D, Khaidarov S, Ossikbayeva S, Kaidarova D. Statistical Genetics of DMD Gene Mutations in a Kazakhstan Cohort: MLPA/NGS Variant Validation and Genotype–Phenotype Modelling. Genes. 2026; 17(1):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010020

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoldakaryzova, Aizhan, Dias Dautov, Saken Khaidarov, Saniya Ossikbayeva, and Dilyara Kaidarova. 2026. "Statistical Genetics of DMD Gene Mutations in a Kazakhstan Cohort: MLPA/NGS Variant Validation and Genotype–Phenotype Modelling" Genes 17, no. 1: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010020

APA StyleMoldakaryzova, A., Dautov, D., Khaidarov, S., Ossikbayeva, S., & Kaidarova, D. (2026). Statistical Genetics of DMD Gene Mutations in a Kazakhstan Cohort: MLPA/NGS Variant Validation and Genotype–Phenotype Modelling. Genes, 17(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010020