Abstract

Background/Objective: Inherited retinal degenerations (IRDs) are the leading cause of blind registration in children and adults, yet 30–40% of cases remain genetically unresolved. Deep ophthalmic phenotyping may help to address this shortfall by identifying characteristic phenotypes. We describe the ophthalmic features of patients with stationary or progressive inherited retinal diseases other than outer retinal degeneration (i.e., secondary ophthalmic features, SOFs). Methods: This is a retrospective review of all patients attending an ophthalmic genetics clinic with a genetically confirmed IRD focusing on SOFs including refractive error, cataract, retinal detachment (RRD), cystoid macular lesions (CML) and epiretinal membrane (ERM). These features were assessed in the context of phenotype and genotype. Results: In a cohort of 429 genotyped patients, ≥1 SOFs were seen in 70.2% of patients, with 36.6% being affected by multiple SOFs. Refractive error (63.3%) and cataract (43.4%) were the most common secondary features, with a subset affected by CML (14.7%), ERM (10%) and RRD (4.7%). Conclusions: SOFs are common in patients with IRDs and most are amenable to therapeutic intervention even when no primary treatment (e.g., gene therapy) is available. We highlight patterns associated with genotypes and disease groups which may aid harmonisation of clinical and genetic diagnoses.

1. Introduction

Inherited retinal degenerations (IRDs) are a heterogeneous group of predominantly Mendelian genetic disorders which cause visual loss due to progressive outer retinal atrophy (e.g., retinitis pigmentosa, RP) or stationary dysfunction of synaptic activity (e.g., congenital stationary night blindness, CSNB). IRDs are the leading cause of blindness in children and working age adults in the Western world but, despite significant investment of resources, disease-modifying treatments are unavailable for most conditions [,].

Many IRDs have a final common pathway of outer retinal degeneration which may make correlation with a particular genotype difficult considering the >300 known genetic associations []. The extraocular features in syndromic IRDs may help to narrow the possible genetic aetiologies (e.g., hearing loss in Usher syndrome is associated with only 14 genes). Similarly, both syndromic and non-syndromic IRDs often have ophthalmic features other than those affecting the outer retina (i.e., photoreceptors and retinal pigment epithelium, RPE), which we refer to here as ‘secondary ophthalmic features’ (SOFs) []. These features (or constellations thereof) can be characteristic of phenotype groups (e.g., LCA, CSNB) or individual genotypes. Considering that 30–40% of IRDs currently remain unresolved, SOFs may significantly assist in discovery of new genetic associations and validation or exclusion of candidate variants in IRD-associated genes detected with next generation sequencing (i.e., pathogenic supporting, PP4, criteria of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics, ACMG) []. For example, cystoid macular lesions (CML) may occur in many IRDs [e.g., RP, X-linked (XL) retinoschisis (XLRS)], but if the patient also has high hyperopia, nanophthalmos and optic disc drusen, this significantly narrows the genotypic spectrum (e.g., MFRP, BEST1) [].

The holy grail of IRD treatment is genetic rescue of retinal function, yet only a single disease-modifying gene therapy (voretigene neparvovec-rzyl, Luxturna for biallelic RPE65-IRD) has been approved though over 50 clinical trials of novel therapies (gene-specific and gene-agnostic) are in progress [,,,,,,,]. As opportunities to treat IRDs increase, further defining natural history and increasing the proportion of genetically resolved cases is relevant and SOFs may play a role in this.

Further to helping refine the phenotype, many SOFs (e.g., refractive error, cataract, CML, amblyopia) are amenable to simple and low-cost treatments which may stabilise or even improve visual function. Such interventions can often be made from the first clinical visit before a genetic diagnosis has been reached. While successful gene therapy trial outcomes are eagerly awaited, such simple interventions, when placed alongside appropriate supports (e.g., mobility, low vision, educational, financial, employment), may cause meaningful differences in activities of daily living and quality of life [].

‘Target 5000’ is the Irish national registry of patients affected by IRDs which fulfils clinical (phenotyping, genetic testing, clinical management) and research (gene/variant discovery, therapy development) functions [,,,,,]. The goals of this paper are (1) to describe the SOFs of a large patient cohort with genetically confirmed IRDs, and (2) to identify any associations of SOFs with genotype or retinal phenotype and to discuss possible causes for these associations.

2. Materials and Methods

A retrospective cross-sectional review of patients with genetically confirmed IRDs was conducted with a focus on SOFs. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the Mater Misericordiae University Hospital (#1.378.1358) and follows the declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided informed consent.

The study considered patients recruited to the institutional IRD registry between July 2012 and July 2020. Patients were excluded if no genetic diagnosis was confirmed or if inadequate data were available. Of 540 patients with a clinical IRD diagnosis, genotype was confirmed for 429 (79.4%).

Assessed data included patient age, sex, clinical retinal diagnosis, genotype, best corrected visual acuity (BCVA), lens status (cataract or pseudophakia), refractive error (spherical equivalent and astigmatism, in dioptres, D), keratoconus (KC) diagnosis, presence of macular pathology [e.g., CML, epiretinal membrane (ERM)], retinal detachment (rhegmatogenous, Coats-like exudative vitreoretinopathy), amblyopia and glaucoma.

Patients were excluded from refractive error analysis if they had prior refractive surgery or were pseudophakic unless pre-operative refraction was available. BCVA was converted to LogMAR equivalent to facilitate analysis and FrACT equivalents were used for ‘counts fingers’ (1.9 LogMAR), ‘hand movements’ (2.3 LogMAR) and ‘perception of light’ (2.7 LogMAR) []. No light perception (NPL) vision was not quantified. Amblyopia was physician-reported in children (who represented the majority of cases with amblyopia) and self-reported in adults and validated by clinical findings. Refraction is specified as the spherical equivalent (SE, i.e., sphere power + 0.5 × cylinder power). Astigmatism was analysed independently based on cylinder power.

Phenotype groups were used for analysis, namely achromatopsia [ACHM, (CNGA3, CNGB3, PDE6H)], Bardet–Biedl syndrome [BBS (BBS1, BBS4, BBS10, SDCCAG8, TRIM32)], collagenopathies (COL2A1, COL11A1, COLA18A1), congenital stationary night blindness [CSNB (CACNA1F, NYX, RDH5, TRPM1)], Leber congenital amaurosis [LCA (AIPL1, CEP290, CRB1, CRX, GUCY2D, PROM1, RDH12, RPE65, TULP1)], non-syndromic RP [nsRP (EYS, PRPF31, RHO, RP1, RP2, RPGR, SNRNP200)] and Usher syndrome [USH (ADGRV1, ARSG, CDH23, CLRN1, MYO7A, USH1C, USH2A)]. All patients in this cohort with BEST1-associated retinopathy had autosomal dominant (AD) disease.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v20 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). As there was similarity between eyes for BCVA (p = 0.218), only right eye values were analysed. Descriptive statistics (mean ± standard deviation, SD) were used to present quantitative data for all genotype and phenotype groups. SOFs were compared between phenotype groups and the most prevalent genotypes. For normally distributed data, comparisons of means were used and for non-normally distributed data, non-parametric tests were used. The limit of significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics, BCVA and Amblyopia

The mean age of the 429 genetically characterised patients (from 317 pedigrees) was 39.8 ± 19.3 years, 44.7% were female and 81 different genotypes were represented (Table S1). Eight (1.9%) were carriers of XL IRD (CHM, RPGR), and the mean age of carriers was 42.9 ± 18.5 years. There were no significant age differences between sexes (p = 0.459).

Mean BCVA for the total cohort was 0.79 ± 0.73 LogMAR (Table 1 and Table S1). There were no significant BCVA differences between sexes (p = 0.236) but there was a correlation between worse BCVA and older age (r = 0.205, p < 0.001, Figure 1). The best BCVA was seen in the collagenopathy (0.20 ± 0.28 LogMAR) and CSNB (0.39 ± 0.37 LogMAR) groups while the worst BCVA was seen in the LCA (1.37 ± 0.85 LogMAR) and BBS (1.11 ± 0.91 LogMAR) groups. There was a significant BCVA difference between nsRP and BBS (p = 0.007) but not between nsRP and USH (p = 0.703). BCVA was similar between males and females for the CHM (p = 0.111) and RPGR (p = 0.340) genotypes. The blindness criteria for BCVA (≥1.0 LogMAR) were met by 31.0% and the driving standard (≤0.3 LogMAR) was met by 32.9%. Only four patients (0.9%, CEP290, COL2A1 ×2, RDH12) had NPL vision, suggesting that IRDs rarely extinguish vision altogether.

Table 1.

Age, sex and BCVA of the 10 most prevalent genotypes.

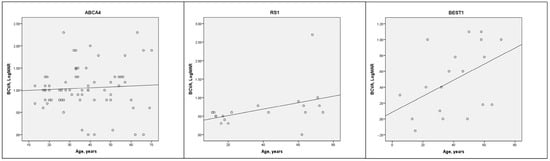

Figure 1.

Cross-sectional scatter plots of BCVA vs. age (with trend line) for the three most prevalent genotypes (ABCA4, RS1, BEST1). Pearson correlation: ABCA4 (r = 0.61, p = 0.617), RS1 (r = 0.447, p = 0.55), BEST1 (r = 0.425, p = 0.07).

Amblyopia was diagnosed in 88/429 (20.5%) and disproportionately affected females, 53/191 (27.7%), compared with males, 35/238 (14.7%), though this association was not significant (X2, p = 0.522). The IRD genotypes represented in the amblyopia group were those associated with retinitis pigmentosa (n = 30, 34.1%, MYO7A, PRPF31, RHO, RPGR, SNRNP200, USH2A), high myopia (n = 21, 23.9%, COL2A1, RPGR), LCA (n = 16, 18.2%, CRB1, GUCY2D, RDH12, RPE65) or significant hyperopia (n = 14, 15.9%, BEST1, RS1).

3.2. Cataract

Cataract and pseudophakia were diagnosed in 116 (27%) and 70 (16.3%) patients, respectively, together representing 43.4% of the cohort. There were no significant sex biases for cataract (p = 0.148) or pseudophakia (p = 0.977). Posterior subcapsular (n = 61, 52.6%), nuclear sclerotic (n = 24, 20.7%) and cortical (n = 17, 14.7%) cataract were similarly prevalent in either sex.

There were significant age differences between the cataract (47.5 ± 16.8 years) and pseudophakia (55.3 ± 14.4 years) groups when compared to the group without either (‘clear lens group,’ 30.3 ± 16.6 years, both p < 0.001). There was a significant BCVA difference between the clear lens (0.63 ± 0.58 LogMAR) and cataract (0.90 ± 0.86 LogMAR) groups (p = 0.017), but not between the clear lens and pseudophakia (0.86 ± 0.81 LogMAR, p = 0.071) groups. The combined group (i.e., cataract and pseudophakia together) was older (50.4 ± 16.4, p < 0.001) and had worse BCVA (0.89 ± 0.84, p = 0.003) than the clear lens group. There were also significant age (p < 0.001) and BCVA (p = 0.023) differences between the cataract and pseudophakic groups. One third of all cataracts in the cohort were identified in those ≤50 years, and 59% of the 41–50-year age group had cataract.

The USH and collagenopathy groups had the greatest rate of cataract (47.7%) and pseudophakia (40%), respectively, while ACHM had the lowest cataract (6.7%) and pseudophakia (0%) rate. No CSNB patient (CACNA1F, NYX, RDH5, TRPM1, mean age 26.7 ± 21.3 years) had cataract and only one (10%, RDH5, age 83 years) had pseudophakia. The relationship between lens status and genotype is summarized in Table 2 and Table S2.

Table 2.

Cataract, pseudophakia and refraction for the most myopic and hyperopic genotypes with ≥5 patients.

3.3. Refractive Error

Refraction data were available for 226 patients (52.7%, 67 genotypes, Table S2). The refraction group was significantly younger (mean age 37.6 ± 19.5 years) than both the cataract (47.5 ± 16.8 years, p < 0.001) and pseudophakia (55.3 ± 14.4 years, p < 0.001) groups. Myopia (SE ≤ −0.50D) was present in 114 (50.4%) and hyperopia (SE > +0.75D) was present in 86 (38.1%). Significant refractive error (SE < −2.0 D or > +2.0 D) was present in 63.3% (n = 57 > +2.00D and n = 86 <−2.00D). There were no statistically significant sex differences for SE (p = 0.980), astigmatism (p = 0.451), high myopia (p = 0.739) or high hyperopia (p = 0.463). Age was not correlated with SE (p = 0.508), but was with astigmatism (r = −0.142, p = 0.033). SE and astigmatism were closely related, with a greater degree of hyperopia being associated with less astigmatism (r = −0.205, p = 0.002). BCVA did not correlate with SE (p = 0.200) or astigmatism (p = 0.778).

High myopia (≤−6.00D) was twice as common (n = 35, 15.5%) as high hyperopia (≥+5.00D, n = 17, 7.5%). Mean SE refraction was −9.54 ± 3.54D for high myopes and +7.36 ± 2.42D for high hyperopes, with the degree of ametropia (i.e., absolute deviation from emmetropia) being significantly greater for high myopes (p = 0.027). The clinically relevant differences in mean BCVA between high myopes (0.73 ± 0.74 LogMAR) and high hyperopes (1.21 ± 0.89 LogMAR) were not statistically significant (p = 0.053). There were no significant correlations between BCVA and the degree of high hyperopia (p = 0.633) or high myopia (p = 0.140). High myopia was associated with the NYX (n = 4, −8.34 ± 1.75D), RPGR (n = 3, −8.63 ± 2.69D) and TRPM1 (n = 3, −8.92 ± 2.63D) genes. High hyperopia had the greatest representation from the BEST1 (n = 4, +6.69 ± 0.97D), RS1 (n = 4, +7.00 ± 2.00D), MFRP (n = 2, +12.31 ± 4.33D) and TULP1 (n = 2, +6.13 ± 1.24D) genotypes. The degree of ametropia associated with each genotype is described in Figure 2, Table 2 and Table S2.

Figure 2.

Bar chart of maximal refractive error stratified by genotype. SE = spherical equivalent refraction.

Among phenotype groups, there was a wide range of refractive error from extreme myopia to extreme hyperopia (Table 3). COL2A1-associated Stickler syndrome and the CSNB group had the most consistent refractive errors, with no patient being hyperopic.

Table 3.

Demographics, BCVA, lens status and refractive state of phenotype groups.

Considering female ‘carriers’ of XL conditions and males with classic disease, there were no significant differences in SE or astigmatism for RPGR (p = 0.843 and p = 0.839, respectively) or CHM (p = 0.229 and p = 0.390, respectively). Despite their variable retinal phenotype, RPGR ‘carrier’ females were, on average, as myopic as their fully penetrant male counterparts.

Keratoconus was rarely reported (n = 5/429, 1.2%, CEP290, GUCY2D, RHO) in the total cohort but was disproportionately (n = 3/53, 5.7%) co-diagnosed with LCA (CEP290 ×1, GUCY2D ×2). A history of corneal refractive surgery was documented in only two adults.

3.4. Macular Pathology

CML include both cystoid macular oedema and retinoschisis, which may be clinically difficult to distinguish despite their very different aetiologies. CML were present in 63 patients (14.7%). This was most prevalent in RS1 (n = 15/21, 71.4%) and AD-RP [(n = 15/49, 30.6%), particularly RHO (6/16, 37.5%)] but less frequent in ARRP (3/14, 21.4%) and XLRP (1/24, 4.2%). ERM was present in 43 patients (10%), and most commonly encountered in those with RP (76.7%, n = 33/43) [BBS (n = 10/21, 47.6%), USH (n = 12/44, 27.3%) and non-syndromic RP (n = 11/86, 12.8%)]. There were no sex biases for CML (X2, p = 0.078) or ERM (p = 0.313). BCVA was significantly better in patients with CML (0.41 ± 0.37 vs. 0.84 ± 0.74, p < 0.001), though age was similar (40.0 ± 19.7 vs. 40.5 ± 18.6 years, p = 0.997). There were no differences for age (p = 0.865) or BCVA (p = 0.558) for those with and without ERM. Only one patient (0.2%, female) was recorded as having choroidal neovascularisation (CNV) with an AD BEST1 phenotype (5% of BEST1 group).

3.5. Retinal Detachment

Twenty-one patients (4.9%) had rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RRD), with six having bilateral RRD. The most prevalent genotypes affected by RRD were COL2A1 (n = 7, 33.3%), FBN1 (n = 6, 28.6%) and RS1 (n = 3, 14.3%). Only three patients (14.3%) with photoreceptor degenerations (KCNV2, RDH12, USH2A) had RRD (unilateral only). The proportions of each genotype affected by RRD were COL2A1: 53.8% (n = 7/13); COL11A1: 100% (n = 1/1); COL18A1: 100% (n = 1/1); FBN1: 50% (n = 6/12); KCNV2: 33.3% (n = 1/3); RDH12: 14.3% (n = 1/7); RS1: 14.3% (n = 3/21); and USH2A: 5.3% (n = 1/19). Bilateral RRD was only seen in collagenopathies/vitreoretinopathies with COL2A1 (n = 2, 33.3%), COL11A1 (n = 1, 16.7%), COL18A1 (n = 1, 16.7%) and FBN1 (n = 2, 33.3%) genotypes. The only hyperopic RRD patients (mean +3.79 ± 5.39D, range +2.75–+9.63D) had RS1 genotypes (n = 3). Though only 25% of eyes with RRD had high myopia, the RRD group [−4.05 ± 8.01D (range −21.38–+9.63D)] was significantly more myopic than the non-RRD group (−0.87 ± 4.62D, p = 0.03). BCVA in eyes with treated RRD was not significantly worse than in those unaffected by RRD (0.98 ± 0.95 LogMAR vs. 0.79 ± 0.72, p = 0.813); however, two RRD eyes had NPL vision which was not quantified, thus underestimating the visual impact of RRD.

Twelve patients (2.8%) had documented retinal tears without RRD. These eyes had a mean refractive error of −4.50 ± 4.49D (range −0.25–−11.13D) and three of these patients (25%; ABCA4, COL2A1, KCNV2) had high myopia. Two female patients (0.5%; CEP290, CERKL) had a Coats-like exudative vitreoretinopathy (CLEVER) and one patient (0.2%, RS1) had retinal neovascularisation.

3.6. Glaucoma

Glaucoma was co-diagnosed in 18 patients (4.2%; BEST1 ×2, COL2A1 ×3, FBN1 ×2, FLVCR1, KIZ, MAK, MFRP, MYO7A, NR2E3, OAT, RHO ×3, RP1, USH2A). Interestingly, (high) hyperopia (MFRP, MYO7A, BEST1) was more common in this group than myopia. Details of glaucoma medications were not available but only two patients (BEST1, COL2A1) required surgical management (tube shunt).

3.7. Cumulative SOFs per Patient

One or more SOFs (range 1–6) were seen in 301 (70.2%) patients, with 157 (36.6%) affected by ≥2 SOFs (Figure 3A). Even if refractive error was excluded, these proportions would be 62.9% (n = 270) and 31.0% (n = 133), respectively. Older patients had more SOFs, though this association was non-significant (p = 0.647, Figure 3B). Syndromic conditions with non-congenital vision loss, including the collagenopathy, USH and BBS groups, had the most SOFs while congenital conditions (ACHM, CSNB, LCA) had the fewest (Table S3). BCVA did not significantly vary between those with differing numbers of SOFs. Patients with NPL vision had mean 2.5 ± 1.7 SOFs.

Figure 3.

(A) Number of SOFs per patient. (B) Age boxplots of patients with different numbers of SOFs.

4. Discussion

Secondary ophthalmic features are common in patients with IRDs, with 70% being affected by one or more SOFs. Refractive error (63.3%) and cataract (43.4%) were the most common secondary features, but a range of other vision-threatening secondary pathologies were also observed in this vulnerable group. Screening for and treatment of these SOFs may enable meaningful improvement in visual quality of life despite the lack of retinal disease-modifying therapies.

4.1. BCVA and Amblyopia

Considering the broad range of IRD genotypes included, BCVA varied widely. Expected BCVA differences between genotypes and phenotypes were corroborated [e.g., LCA has worse BCVA than RP; syndromic RP (BBS) has worse BCVA than nsRP] []. Female ‘carriers’ of pathogenic RPGR variants did not have significantly worse BCVA than males with classical disease, highlighting the fact that up to 1/3 of this group may have significant progressive visual disability [].

There are multiple potential risk factors for amblyopia in IRDs including high ametropia/anisometropia, strabismus, early-onset cataract and asymmetrical retinopathy (e.g., female carriers of X-linked diseases). Amblyopia may be part of the working diagnosis while a child is being investigated for an IRD. Even after molecular confirmation, coexistent amblyopia may be a treatable feature. Confidence in an amblyopia diagnosis is difficult in adult IRD populations considering the coexistent structural abnormalities in the retina and that asymmetrical disease may simulate amblyopia, though the cases described herein were supported by clinical evidence [].

4.2. Cataract

Cataract is a common SOF, diagnosed in 43.4% of the cohort studied here. A small central posterior subcapsular cataract may have a disproportionate impact on vision in the setting of visual field constriction (e.g., RP) or macular dysfunction (e.g., Stargardt disease) in which glare and defocus from cataract may compound image degradation []. The biological/metabolic dysfunction underlying lens pathology (i.e., cataracts or ectopia lentis) varies between retinal phenotypes. For instance, the posterior subcapsular cataract associated with RP may warrant surgery when gradual worsening causes reduced vision. In contrast, a patient with FBN1-associated Marfan syndrome may require lensectomy due to progressive lens subluxation despite having no ‘cataract’. Surgical treatment of cataract is commonly performed, seen in 16.3% of our total cohort. Cataract surgery in RP is often performed in the fifth to sixth decades, 20 years younger than in the general population [,]. In the current study, both the cataract and pseudophakia groups were significantly younger than the general population age at cataract surgery (range 60–80 years), highlighting the early onset of visually significant cataracts in IRDs. The optimal age for cataract surgery in IRDs is unknown but symptoms should guide case-by-case management. The one third of cataracts accounted for by the ≤50-year age group in the current cohort is 3× that of the general ≤50-year population (11%) [].

Considering concomitant macular pathology, it is difficult to accurately predict the degree of BCVA improvement following cataract surgery though BCVA outcomes < 1.0 LogMAR are seen in 84% and a three-line (15-letter) improvement may be achieved in ~40% [,]. Certain intraoperative (e.g., zonular dialysis, 5%) and postoperative (e.g., posterior capsular opacification, 38%; worsened CML, 5%; capsular phimosis) complications are more likely in RP and should be actively anticipated and managed at the time of surgery [,,].

Unlike the natural crystalline lens, most intraocular lens implants have no chromatic filtering capacity, and thus may allow transmission of more ultraviolet light, possibly accelerating oxidative stress and photoreceptor death. However, multiple reports describe improvement in function (BCVA and macular sensitivity) and no difference in disease progression compared with phakic counterparts [,,,,]. Most data discuss cataract surgery in RP, where prognosis may be predicted by pre-operative preservation of the foveal ellipsoid zone (e.g., >600 µm width may predict a better outcome) and control of CML [,,]. Tools such as patient-reported outcome measures may better clarify the additional qualitative benefits of cataract surgery in future studies [,].

4.3. Refractive Error

Significant refractive error is common in IRDs [,,,]. While the direct cause for this association has not been proven, degraded image quality due to photoreceptor degeneration is likely to disrupt normal emmetropization [,,]. Unfortunately, these adaptive changes in refractive state may not improve BCVA due to progressive macular photoreceptor atrophy. In addition, considering the heterogeneous nature of this group of diseases, other individual or composite genetic factors may contribute to disruption of normal refractive development. Over 400 genes influence refractive error, some of which may be inherited as a haplotype (e.g., in East and South Asian ethnicities) or be influenced by behavioural trends (e.g., urban environments, increased near activities) []. The genetic influences on the development of myopia have previously been categorised by which biological process is interrupted []. In the case of IRDs, several of these categories are accounted for, including collagen fibril organisation/catabolism (e.g., COL2A1), retinal/lens development (e.g., FBN1, RP genes), secretory proteins [i.e., extracellular matrix (e.g., IMPG1/IMPG2) and cell–cell junctions (e.g., RS1)] and perception of visible light (e.g., OPN1MW/OPN1LW, RHO). Some genes implicated in IRDs (e.g., BEST1, LRP5, MFRP) affect organogenesis, modulating ocular development in the foetal and early childhood phases, leading to early-onset myopic or hyperopic refractive errors.

High myopia was significantly over-represented in this IRD population (15.5% prevalence) compared with the general population (5.3%), though this may vary with geography and ethnicity (NB the current population was predominantly white Irish) []. This suggests that, although myopia development is contingent on a legion of background genetic and environmental factors, pathogenic variants in some IRD-associated genes strongly influence myopic drive []. Less deleterious/hypomorphic alleles in these same genes may manifest as refractive error without retinal degeneration (e.g., female carriers of pathogenic RPGR variants) [,,]. In fact, variants in IRD-associated genes are thought to underlie half of early-onset myopia cases []. Another marked example of IRDs and myopia is complete CSNB (~−6.8–−9.26D), which was replicated in the current cohort by NYX (−8.34 ± 1.75D) [,,]. Other notable myopia associations include RPGR (~80% of XLRP, −2.6–−9D), OAT (gyrate atrophy, −9D), RP1 (~1% of ARRP, −5.5D; 5–7% of ADRP, ~−1D) and IMPG2 (~−4D) [,,]. Our cohort largely concurred with these findings and highlights vitreoretinopathies (e.g., COL2A1, FBN1) as significant contributors to syndromic myopia parallel to photoreceptor and synaptic dystrophies. Hyperopia is common in some IRDs including AD BEST1-retinopathy, RS1 and some LCA genotypes (in the current cohort: AIPL1, ALMS1, CEP290, CRB1, CRX, TULP1) [,]. Several genes (e.g., BEST1, CRB1, MFRP, PRSS56 and TMEM98) which have roles in both foetal ocular development and post-natal outer retinal maintenance, can be associated with high hyperopia and short axial length [,,,].

Systematic assessment of refractive error not only enables correction of image defocus but may trigger investigations for IRDs (e.g., electroretinography, genetic testing) in children with high ametropia ±uncorrectable visual loss []. Additionally, a strong refractive phenotype paired with suggestive electrophysiological or fundus features may help to resolve candidate genetic variants (e.g., ACMG, PP4 criteria—highly suggestive phenotype for a single genetic aetiology) [,].

4.4. Keratoconus

Keratoconus (KC) can be considered a subtype of progressive refractive error, which may lead to corneal scarring, a further contributor to visual impairment. KC affects approximately 0.2% of the general population but its prevalence in IRDs is unknown, discussed only in infrequent case reports and an older (1968) genetically uncharacterised cohort study [,]. In the current cohort, KC was diagnosed in 1.2% (6× population risk). To our knowledge, this is the first study to estimate KC prevalence in a genetically characterised IRD population. Even if the implicated IRD gene has no direct corneal expression, developmental (e.g., mesenchymal differentiation) and behavioural (e.g., eye rubbing) factors may predispose to KC [,]. For example, in LCA the oculo-digital sign (i.e., eye rubbing to elicit visual sensations) may increase risk of corneal ectasia and its end stage sequelae (i.e., scarring) []. Another risk factor for KC which often overlaps with IRDs is intellectual disability, in which eye rubbing and/or atopy are common []. This refractive/media change further limits visual function and is a point of intervention, either in prevention by corneal collagen crosslinking or corneal transplantation where visual potential exists.

4.5. Macular Pathology

CML are well-described in RP and other IRDs (32% of paediatric and 59% of adult cohorts) [,,,]. In our study, the total CML rate was 14.7%—highest in XLRS (71.4%) and AD RP (30.6%). CML were less prevalent in severe early-onset disease (e.g., LCA, XLRP), in keeping with published reports []. The actual rate of CML may be higher as cystic spaces may resolve with treatment or collapse with disease progression and accurate visualisation/quantification may be limited (e.g., nystagmus, poor fixation, young children). The worse vision in those without CML is likely due to the higher prevalence of macular outer retinal atrophy in this group.

ERM is similarly common in RP (~20%) and the general population (10–28.9% of 45–84-year-olds), though RP patients with ERM were much younger (39.2 ± 18.1 years) [,]. Though RP has the best known association with ERM, 23.3% of the current cohort with ERM had non-RP genotypes. Whether this is directly related to the process of retinal degeneration or to usual ERM risk in the general population is unknown. ERM may be composed of fibroblasts, glial cells and/or RPE cells []. As the final stage of intraretinal pigment migration (i.e., bone spicules), RPE cells are thought to migrate transretinally (i.e., without retinal breaks) along the vasculature of the neurosensory retina to the inner retinal surface [,,]. Clinically, the vitreous in RP is inundated with copious pigmented cells which are histologically confirmed as RPE cells []. Considering ERM is often a sign of advanced retinal degeneration, surgical correction of retinal distortion by ERM may have limited benefit, as demonstrated by Ikeda et al. who reported structural benefit without significant BCVA gain []. Integrity of foveal photoreceptors may be a useful prognostic guide for symptom-based management decisions on a case-by-case basis [,]. Interestingly, Stargardt disease, particularly with restricted macular atrophy, is infrequently associated with ERM [], consistent with the current cohort where only 2.9% (n = 2/69, mean age 45.5 ± 29.0 years) of those with an ABCA4 genotype had ERM. Perhaps the pan-retinal nature of RP-associated photoreceptor/RPE death has a more profound impact on RPE cell migration and metaplasia.

4.6. Retinal Detachment

The rate of RRD in the general population without a known genetic predisposition is approximately 1:10,000 or 0.01%; thus, the rate in this IRD cohort (n = 20/429, 4.7%) is 470× higher []. If collagenopathies (COL2A1, COL11A1, COL18A1) and Marfan syndrome are removed, this figure (n = 3/401, 0.7%) remains 70× the population risk. Several RRD risk factors are common in IRDs, namely myopia and abnormal vitreous. In the general RRD population, myopia is seen in 50–80% (region- and ethnicity-dependent), with greater myopia/axial length being positively correlated with RRD risk []. For example, lifetime RRD risk increases 10× with −3.00 to −5.00D of myopia or ~2.2% absolute RRD risk with ≤−5.00D of myopia increasing to 36% with coexistent lattice degeneration [,,].

High myopia (≥−6DSE) was present in 15.5% of the current cohort, 3× the rate of the general population (5.3%) []. This does not match the 70–470× increased risk of RRD; thus, there are clearly other risk factors at play. Pruet et al. described a low incidence of RRD (1.8%) in an RP registry and postulated that early vitreous detachment, absence of lattice degeneration and unusually strong RPE-NSR adhesion might account for this relatively low rate (still 180×) []. The ‘adhesive’ force keeping the retina in place is derived from RPE pump function and thus diseases affecting the RPE may theoretically be more likely to incite RRD. However, RRD is clearly not exclusively Mendelian though strong family tendencies do occur, and a complex balance of risk factors (i.e., genetic and environmental) is at play [].

Certain phenotypes/genotypes predispose to RRD, including XLRS (10–12.8% RRD rate) and Stickler syndrome type 1 (up to 73% RRD rate) [,]. The phenotype of the RRD (e.g., non-traumatic juvenile RRD, giant retinal tear) or the non-detached fellow eye (e.g., radial lattice, membranous vitreous anomaly) may suggest an IRD/vitreoretinopathy and instigate appropriate investigation, patient education and prophylaxis []. Similarly, confirmation of a pathogenic variant(s) in certain IRD genes (e.g., COL2A1) in as-yet asymptomatic relatives should prompt patient education, careful clinical surveillance ± prophylaxis.

RRD is related to pathological mechanical changes in the vitreoretinal interface (e.g., posterior vitreous detachment, PVD; lattice degeneration, 30–46% of RRD); thus, genetic variants in collagen genes (e.g., COL2A1, COL11A1, COL18A1) are logically implicated in Stickler syndrome [,,]. Other genes have been associated with high myopia (e.g., MYP loci, RDH5, RPGR), axial elongation, lattice degeneration (e.g., COL4A4) and premature PVD [,]. The increased rate of cataract and higher rate of cataract surgical complications in IRD populations may further contribute to the risk of RRD. However, in this cohort, only 45% of patients presenting with RRD were pseudophakic but the design of this study precludes assessment of temporal associations.

Though the occurrence of RRD in RP is low, primary surgical success and visual outcomes may be poorer than expected due to coexistent macular pathology []. Additionally, conventional treatment strategies (e.g., laser, cryotherapy) may be more (e.g., pigmentary retinopathy) or less (e.g., albinism) successful. Reattachment in an eye with underlying IRD may be accompanied by a dramatic pigmentary reaction and marked reduction in vision, out of keeping with the expected rate and degree of progression of retinal degeneration (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Asymmetrical pigmentary retinopathy after reattachment of RRD. The right eye (images (A,C,E), which had undergone successful retinal reattachment surgery, exhibits typical features of retinitis pigmentosa with sparing of only the central macula. The left eye (images (B,D,F)) shows much less marked retinal degeneration.

4.7. Glaucoma

Glaucoma was co-diagnosed in 4.2% of patients. This is not significantly different from the 3.5% population risk but may be an underestimation as symptoms (e.g., visual field constriction) and signs (e.g., optic atrophy) of IRDs may mask those of glaucoma []. The risk of this second vision-threatening pathology, particularly angle closure glaucoma, may be higher than that of the general population (1.1%) in some IRD genotypes (e.g., BEST1, CRB1, MFRP) associated with microphthalmia/nanophthalmos []. Surgical management of aggressive glaucoma may be more prone to complications (e.g., malignant glaucoma, progression), and novel therapeutic approaches may be required [].

4.8. Rare SOFs

Several SOFs were noted extremely rarely in this population, namely CNV (0.2% vs. 7–50% in the literature), CLEVER (0.5% vs. 5% in the literature) and retinal neovascularisation (0.2% vs. 1–5% in the literature). However, diagnosis of these features may vary in different ethnicities or genotypes and detection depends on the investigations used (e.g., optical coherence tomography angiography is reportedly superior to fluorescein angiography for CNV detection) [,,,].

4.9. Limitations and Strengths

Limitations include the retrospective study design, low patient volumes for subgroup analyses and reliance on patient history and referral letters for ophthalmic and medical history. The creation of phenotype groups may be misleading as some genes are pleiotropic (i.e., associated with multiple phenotypes of varying severity). The study cohort was almost entirely of white Irish ethnicity; thus, the influence of the background genome on phenotype may differ in ancestrally distinct populations. This is a cross-sectional study including patients of varying ages and disease stages; thus, some secondary features may have not yet manifested (e.g., absence of cataract in early stage RP) or already resolved (e.g., CML resolution with topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitors), underestimating prevalence. CML may not have been present at the time of assessment, even in conditions known for CML (e.g., RP, NR2E3-retinopathy) as this cohort was not treatment-naïve. Disease duration is the ideal benchmark to measure SOF development, but this was not available in this dataset. The takeaway observation is that SOFs are common and often treatable and should be considered as a modifiable feature by clinicians.

Cataract surgery may be performed for reasons other than improving BCVA (e.g., angle closure, progressive ectopia lentis); thus, this may influence BCVA statistics for pseudophakic and phakic patients. Technical details of cataract surgery (e.g., intraoperative complications) were not available. BCVA was used as the main functional measure while visual field data (relevant in conditions affecting the retinal periphery) were not available; however, patient-reported outcome/experience measures may be more appropriate qualitative measures []. A strength of this study is that it reports on a large genetically resolved IRD population with a wide range of IRD genotypes and considers several clinically significant SOFs which may be amenable to treatment.

5. Conclusions

Secondary ophthalmic features of IRDs are common and may compound the visual impairment caused by primary retinal dysfunction, and multiple SOFs may overlap in a given individual. Although disease-modifying treatments for many of the common hereditary retinopathies are on the horizon, intervention for secondary features can start now to maximise visual function and quality of life. Patterns of these SOFs may enhance deep ophthalmic phenotyping to enable harmonisation with candidate genes and variants in line with existing advice (e.g., ACMG, ClinGen panels), aiding diagnosis.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/genes16121433/s1: Table S1: Genotype, demographics and BCVA of IRD cohort ranked by genotype prevalence. Table S2: Demographics, BCVA, lens status and refractive state of all genotype groups. Table S3: Secondary features for each per phenotype group.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, K.A.J.S., J.Z., D.I.F. and D.J.K.; methodology, K.A.J.S., J.Z., D.I.F. and D.J.K.; software, K.A.J.S., J.Z. and D.I.F.; validation, K.A.J.S., J.Z., M.C., B.M., A.D., L.W., J.T., J.J.O., D.I.F. and D.J.K.; formal analysis, K.A.J.S. and D.I.F.; investigation, K.A.J.S., J.Z., M.C., B.M., D.I.F. and D.J.K.; resources, K.A.J.S., D.I.F., A.D., J.J.O., G.J.F. and D.J.K.; data curation, K.A.J.S., J.Z., M.C. and D.I.F.; writing—original draft preparation, K.A.J.S., J.Z. and D.I.F.; writing—review and editing, K.A.J.S., J.Z., M.C., B.M., A.D., L.W., J.T., J.J.O., G.J.F., D.I.F. and D.J.K.; visualisation, K.A.J.S., G.J.F., D.I.F. and D.J.K.; supervision, J.J.O., G.J.F., D.I.F. and D.J.K.; project administration, K.A.J.S., J.Z., M.C. and B.M.; funding acquisition, G.J.F. and D.J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project received funding from Fighting Blindness Ireland (FB16FAR, FB18CRE, FB20DOC), The Health Research Board Ireland (POR/2010/97), Health Research Charities Ireland (HRCI-HRB-2020-007; MRCG-2013-8, MRCG-2016-14) and Science Foundation Ireland (16/1A/4452).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Mater Misericordiae University Hospital (#1.378.1358, approval date: 22 July 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to protection of confidentiality.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank their funders (Fighting Blindness Ireland, The Health Research Board Ireland, Health Research Charities Ireland, Science Foundation Ireland) and the Irish patients and families affected by IRDs.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BBS | Bardet–Biedl Syndrome |

| BCVA | Best corrected visual acuity |

| CML | cystoid macular lesions |

| CNV | choroidal neovascularisation |

| CSNB | congenital stationary night blindness |

| ERM | epiretinal membrane |

| IRDs | inherited retinal degenerations |

| KC | keratoconus |

| LCA | Leber congenital amaurosis |

| nsRP | non-syndromic retinitis pigmentosa |

| RP | retinitis pigmentosa |

| RRD | rhegmatogenous retinal detachment |

| SOFs | secondary ophthalmic features |

| USH | Usher syndrome |

| XLRS | X-linked retinoschisis |

References

- Liew, G.; Michaelides, M.; Bunce, C. A comparison of the causes of blindness certifications in England and Wales in working age adults (16–64 years), 1999–2000 with 2009–2010. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e004015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffery, R.C.H.; Mukhtar, S.A.; McAllister, I.L.; Morgan, W.H.; Mackey, D.A.; Chen, F.K. Inherited retinal diseases are the most common cause of blindness in the working-age population in Australia. Ophthalmic Genet. 2021, 42, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daiger, S.P. Summaries of Genes and Loci Causing Retinal Diseases (RetNet). 2020. Available online: https://sph.uth.edu/retnet/ (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Verbakel, S.K.; van Huet, R.A.C.; Boon, C.J.F.; den Hollander, A.I.; Collin, R.W.J.; Klaver, C.C.W.; Hoyng, C.B.; Roepman, R.; Klevering, B.J. Non-syndromic retinitis pigmentosa. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2018, 66, 157–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala-Ramirez, R.; Graue-Wiechers, F.; Robredo, V.; Amato-Almanza, M.; Horta-Diez, I.; Zenteno, J.C. A new autosomal recessive syndrome consisting of posterior microphthalmos, retinitis pigmentosa, foveoschisis, and optic disc drusen is caused by a MFRP gene mutation. Mol. Vis. 2006, 12, 1483–1489. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, S.; Bennett, J.; Wellman, J.A.; Chung, D.C.; Yu, Z.F.; Tillman, A.; Wittes, J.; Pappas, J.; Elci, O.; McCague, S.; et al. Efficacy and safety of voretigene neparvovec (AAV2-hRPE65v2) in patients with RPE65-mediated inherited retinal dystrophy: A randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017, 390, 849–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viriato, D.; Bennett, N.; Sidhu, R.; Hancock, E.; Lomax, H.; Trueman, D.; MacLaren, R.E. An Economic Evaluation of Voretigene Neparvovec for the Treatment of Biallelic RPE65-Mediated Inherited Retinal Dystrophies in the UK. Adv. Ther. 2020, 37, 1233–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cukras, C.; Wiley, H.E.; Jeffrey, B.G.; Sen, H.N.; Turriff, A.; Zeng, Y.; Vijayasarathy, C.; Marangoni, D.; Ziccardi, L.; Kjellstrom, S.; et al. Retinal AAV8-RS1 Gene Therapy for X-Linked Retinoschisis: Initial Findings from a Phase I/IIa Trial by Intravitreal Delivery. Mol. Ther. 2018, 26, 2282–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cehajic-Kapetanovic, J.; Xue, K.; Martinez-Fernandez de la Camara, C.; Nanda, A.; Davies, A.; Wood, L.J.; Salvetti, A.P.; Fischer, M.D.; Aylward, J.W.; Barnard, A.R.; et al. Initial results from a first-in-human gene therapy trial on X-linked retinitis pigmentosa caused by mutations in RPGR. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.R.; Drack, A.V.; Cideciyan, A.V.; Jacobson, S.G.; Leroy, B.P.; Van Cauwenbergh, C.; Ho, A.C.; Dumitrescu, A.V.; Han, I.C.; Martin, M.; et al. Intravitreal antisense oligonucleotide sepofarsen in Leber congenital amaurosis type 10: A phase 1b/2 trial. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1014–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanov, A.; Flannery, J.G. A Systematic Review of Optogenetic Vision Restoration: History, Challenges, and New Inventions from Bench to Bedside. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2023, 13, a041304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aleman, T.S.; Uyhazi, K.E.; Roman, A.J.; Weber, M.L.; O’Neil, E.C.; Swider, M.; Sumaroka, A.; Maguire, K.H.; Aleman, E.M.; Santos, A.J.; et al. Recovery of cone-mediated vision in Lebercilin associated retinal ciliopathy after gene therapy: One-year results of a phase I/II trial. Mol. Ther. 2025, 33, 4784–4798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelides, M.; Laich, Y.; Wong, S.C.; Oluonye, N.; Zaman, S.; Kumaran, N.; Kalitzeos, A.; Petrushkin, H.; Georgiou, M.; Tailor, V.; et al. Gene therapy in children with AIPL1-associated severe retinal dystrophy: An open-label, first-in-human interventional study. Lancet 2025, 405, 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, K.A.J.; Zhu, J.; Wynne, N.; Dockery, A.; Cairns, R.M.; Duignan, E.; Whelan, L.; Malone, C.P.; Dempsey, H.; Collins, K.; et al. Target 5000: A standardized all-Ireland pathway for the diagnosis and management of inherited retinal degenerations. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2021, 16, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dockery, A.; Stephenson, K.; Keegan, D.; Wynne, N.; Silvestri, G.; Humphries, P.; Kenna, P.F.; Carrigan, M.; Farrar, G.J. Target 5000: Target Capture Sequencing for Inherited Retinal Degenerations. Genes 2017, 8, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, L.; Dockery, A.; Wynne, N.; Zhu, J.; Stephenson, K.; Silvestri, G.; Turner, J.; O’Byrne, J.J.; Carrigan, M.; Humphries, P.; et al. Findings from a Genotyping Study of Over 1000 People with Inherited Retinal Disorders in Ireland. Genes 2020, 11, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrigan, M.; Duignan, E.; Malone, C.P.; Stephenson, K.; Saad, T.; McDermott, C.; Green, A.; Keegan, D.; Humphries, P.; Kenna, P.F.; et al. Panel-Based Population Next-Generation Sequencing for Inherited Retinal Degenerations. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, K.A.J.; Whelan, L.; Zhu, J.; Dockery, A.; Wynne, N.C.; Cairns, R.M.; Kirk, C.; Turner, J.; Duignan, E.S.; O’Byrne, J.J.; et al. Usher Syndrome on the Island of Ireland: A Genotype-Phenotype Review. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2023, 64, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Stephenson, K.A.J.; Dockery, A.; Turner, J.; O’Byrne, J.J.; Fitzsimon, S.; Farrar, G.J.; Flitcroft, D.I.; Keegan, D.J. Electrophysiology-Guided Genetic Characterisation Maximises Molecular Diagnosis in an Irish Paediatric Inherited Retinal Degeneration Population. Genes 2022, 13, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, C.; Feltgen, N.; Junker, B.; Schulze-Bonsel, K.; Bach, M. Resolving the clinical acuity categories “hand motion” and “counting fingers” using the Freiburg Visual Acuity Test (FrACT). Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2009, 247, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierrache, L.H.; Hartel, B.P.; van Wijk, E.; Meester-Smoor, M.A.; Cremers, F.P.; de Baere, E.; de Zaeytijd, J.; van Schooneveld, M.J.; Cremers, C.W.; Dagnelie, G.; et al. Visual Prognosis in USH2A-Associated Retinitis Pigmentosa Is Worse for Patients with Usher Syndrome Type IIa Than for Those with Nonsyndromic Retinitis Pigmentosa. Ophthalmology 2016, 123, 1151–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, A.; Salvetti, A.P.; Clouston, P.; Downes, S.M.; MacLaren, R.E. Exploring the Variable Phenotypes of RPGR Carrier Females in Assessing their Potential for Retinal Gene Therapy. Genes 2018, 9, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gocuk, S.A.; Edwards, T.L.; Jolly, J.K.; Chen, F.K.; Sousa, D.C.; McGuinness, M.B.; McLaren, T.L.; Lamey, T.M.; Thompson, J.A.; Ayton, L.N. Retinal Disease Variability in Female Carriers of RPGR Variants Associated with Retinitis Pigmentosa: Clinical and Genetic Parameters. Genes 2025, 16, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Li, H.; Sun, Y.; Ji, Y. A Review of Complicated Cataract in Retinitis Pigmentosa: Pathogenesis and Cataract Surgery. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 2020, 6699103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, X.T.; Thiadens, A.; Fiocco, M.; Tan, W.; McKibbin, M.; Klaver, C.C.W.; Meester-Smoor, M.A.; Van Cauwenbergh, C.; Strubbe, I.; Vergaro, A.; et al. Outcome of Cataract Surgery in Patients With Retinitis Pigmentosa. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 246, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, J.; Xu, F.; Guo, W.; Sun, C.; Peng, B.; Huang, Q.; Fan, W. Updated study on demographic and ocular biometric characteristics of cataract patients indicates new trends in cataract surgery. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, S.; Agrawal, D.; Agrawal, D.; Parchand, S.M.; Sahu, A. Cataract surgery in retinitis pigmentosa. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 69, 1753–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, K.; Hayashi, H.; Matsuo, K.; Nakao, F.; Hayashi, F. Anterior capsule contraction and intraocular lens dislocation after implant surgery in eyes with retinitis pigmentosa. Ophthalmology 1998, 105, 1239–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Rojas, J.O.; Schuerch, K.; Mathews, P.M.; Cabral, T.; Hazan, A.; Sparrow, J.; Tsang, S.H.; Suh, L.H. Evaluating Structural Progression of Retinitis Pigmentosa After Cataract Surgery. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 180, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, M.; Shakarchi, A.F.; Elhusseiny, A.M.; Michaelides, M.; Sallam, A.B. Cataract Surgery Outcomes in Retinitis Pigmentosa A Comparative Clinical Database Study. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2024, 262, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Song, H.; Meng, X.; Cao, K.; Liu, Y.X.; Wang, J.; Wan, X.; Jin, Z.B. Effects and Prognosis of Cataract Surgery in Patients with Retinitis Pigmentosa. Ophthalmol. Ther. 2022, 11, 1975–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Fujiwara, K.; Yoshida, N.; Murakami, Y.; Shimokawa, S.; Koyanagi, Y.; Ikeda, Y.; Sonoda, K.H. Long-term Outcomes of Cataract Surgery in Patients with Retinitis Pigmentosa. Ophthalmol. Retin. 2022, 6, 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikopf, M.S.; Chow, C.C.; Mieler, W.F.; Tu, E.Y. Cataract extraction outcomes and the prevalence of zonular insufficiency in retinitis pigmentosa. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2013, 156, 82–88.e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, D.; Takagi, S.; Hirami, Y.; Nakamura, M.; Kurimoto, Y. Use of ellipsoid zone width for predicting visual prognosis after cataract surgery in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Eye 2023, 37, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepworth, L.R.; Rowe, F.J.; Burnside, G. Development of a patient reported outcome measures for measuring the impact of visual impairment following stroke. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacy, G.D.; Abalem, M.F.; Musch, D.C.; Jayasundera, K.T. Patient-reported outcome measures in inherited retinal degeneration gene therapy trials. Ophthalmic Genet. 2020, 41, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieving, P.A.; Fishman, G.A. Refractive errors of retinitis pigmentosa patients. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1978, 62, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flitcroft, D.I.; Adams, G.G.; Robson, A.G.; Holder, G.E. Retinal dysfunction and refractive errors: An electrophysiological study of children. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2005, 89, 484–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igelman, A.D.; White, E.; Tayyib, A.; Everett, L.; Vincent, A.; Heon, E.; Zeitz, C.; Michaelides, M.; Mahroo, O.A.; Katta, M.; et al. Characterising the refractive error in paediatric patients with congenital stationary night blindness: A multicentre study. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2025, 109, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassin, S.H.; Wagner, N.E.; Khuu, T.; Schmidt, R.; Igelman, A.D.; Marra, M.; Schwartz, H.; Walker, E.; Nagiel, A.; Yang, P.; et al. Refractive Error in Inherited Retinal Disease. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2025, 269, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carricondo, P.C.; Andrade, T.; Prasov, L.; Ayres, B.M.; Moroi, S.E. Nanophthalmos: A Review of the Clinical Spectrum and Genetics. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 2018, 2735465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flitcroft, D.I.; Loughman, J.; Wildsoet, C.F.; Williams, C.; Guggenheim, J.A. Novel Myopia Genes and Pathways Identified from Syndromic Forms of Myopia. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2018, 59, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troilo, D.; Smith, E.L., 3rd; Nickla, D.L.; Ashby, R.; Tkatchenko, A.V.; Ostrin, L.A.; Gawne, T.J.; Pardue, M.T.; Summers, J.A.; Kee, C.S.; et al. IMI—Report on Experimental Models of Emmetropization and Myopia. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2019, 60, M31–M88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Y.; Chen, L.J.; Tham, C.C.; Yam, J.C.; Pang, C.P. Genes for childhood myopia. Asia Pac. J. Ophthalmol. 2025, 14, 100139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Saw, S.M.; Wong, T.Y.; Morgan, I.; Yang, Z.; Lan, W. Prevalence and temporal trends in myopia and high myopia children in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis with projections from 2020 to 2050. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2025, 55, 101484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, M.; Kolesnikova, M.; Kim, A.H.; Kowal, T.; Ning, K.; Mahajan, V.B.; Tsang, S.H.; Sun, Y. Clinical characteristics of high myopia in female carriers of pathogenic RPGR mutations: A case series and review of the literature. Ophthalmic Genet. 2023, 44, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurata, K.; Hosono, K.; Hayashi, T.; Mizobuchi, K.; Katagiri, S.; Miyamichi, D.; Nishina, S.; Sato, M.; Azuma, N.; Nakano, T.; et al. X-linked Retinitis Pigmentosa in Japan: Clinical and Genetic Findings in Male Patients and Female Carriers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Iglesias, E.; López-Vázquez, A.; Noval, S.; Nieves-Moreno, M.; Granados-Fernández, M.; Arruti, N.; Rosa-Pérez, I.; Pacio-Míguez, M.; Montaño, V.E.F.; Rodríguez-Solana, P.; et al. Next-Generation Sequencing Screening of 43 Families with Non-Syndromic Early-Onset High Myopia: A Clinical and Genetic Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, M.; Verhoeven, V.J.M.; Buitendijk, G.H.S.; Polling, J.R.; Meester-Smoor, M.A.; Hofman, A.; Kamermans, M.; van den Born, L.I.; Klaver, C.C.W. Development of Refractive Errors-What Can We Learn from Inherited Retinal Dystrophies? Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 182, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chassine, T.; Bocquet, B.; Daien, V.; Avila-Fernandez, A.; Ayuso, C.; Collin, R.W.; Corton, M.; Hejtmancik, J.F.; van den Born, L.I.; Klevering, B.J.; et al. Autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa with RP1 mutations is associated with myopia. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2015, 99, 1360–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurata, K.; Hosono, K.; Hotta, Y. Clinical and genetic findings of a Japanese patient with RP1-related autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Doc. Ophthalmol. 2018, 137, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartong, D.T.; Berson, E.L.; Dryja, T.P. Retinitis pigmentosa. Lancet 2006, 368, 1795–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coussa, R.G.; Binkley, E.M.; Wilkinson, M.E.; Andorf, J.L.; Tucker, B.A.; Mullins, R.F.; Sohn, E.H.; Yannuzzi, L.A.; Stone, E.M.; Han, I.C. Predominance of hyperopia in autosomal dominant Best vitelliform macular dystrophy. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 106, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, R.S.; Caputo, A.R.; Nelson, L.B.; Zanoni, D. High hyperopia in Leber’s congenital amaurosis. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1985, 103, 1507–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundin, O.H.; Dharmaraj, S.; Bhutto, I.A.; Hasegawa, T.; McLeod, D.S.; Merges, C.A.; Silval, E.D.; Maumenee, I.H.; Lutty, G.A. Developmental basis of nanophthalmos: MFRP Is required for both prenatal ocular growth and postnatal emmetropization. Ophthalmic Genet. 2008, 29, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, A.; Zhu, J.; Stephenson, K.A.J.; Whelan, L.; Dockery, A.; Turner, J.; O’Byrne, J.J.; Farrar, G.J.; Keegan, D. MFRP-Associated Retinopathy and Nanophthalmos in Two Irish Probands: A Case Report. Case Rep. Ophthalmol. 2022, 13, 1015–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinowitz, Y.S. Keratoconus. Surv. Ophthalmol. 1998, 42, 297–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karel, I. Keratoconus in congenital diffuse tapetoretinal degeneration. Ophthalmologica 1968, 155, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Hollander, A.I.; Roepman, R.; Koenekoop, R.K.; Cremers, F.P. Leber congenital amaurosis: Genes, proteins and disease mechanisms. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2008, 27, 391–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, J.T. Keratoconus and eye rubbing. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1984, 97, 527–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, B.; Neuhann, T.F.; Neuhann, I.M. Keratoplasty in patients with intellectual disability. Cornea 2014, 33, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Avi, R.; Rivera, A.; Hendler, K.; Sharon, D.; Banin, E.; Khateb, S.; Yahalom, C. Prevalence and associated factors of cystoid macular edema in children with early onset inherited retinal dystrophies. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 33, 11206721221136318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, G.; Strong, S.; Bradley, P.; Severn, P.; Moore, A.T.; Webster, A.R.; Mitchell, P.; Kifley, A.; Michaelides, M. Prevalence of cystoid macular oedema, epiretinal membrane and cataract in retinitis pigmentosa. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 103, 1163–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, G.; Moore, A.T.; Webster, A.R.; Michaelides, M. Efficacy and prognostic factors of response to carbonic anhydrase inhibitors in management of cystoid macular edema in retinitis pigmentosa. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2015, 56, 1531–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, S.; Liew, G.; Michaelides, M. Retinitis pigmentosa-associated cystoid macular oedema: Pathogenesis and avenues of intervention. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 101, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.H.; Cheung, N.; Wang, J.J.; Islam, A.F.; Kawasaki, R.; Meuer, S.M.; Cotch, M.F.; Klein, B.E.; Klein, R.; Wong, T.Y. Prevalence and risk factors for epiretinal membranes in a multi-ethnic United States population. Ophthalmology 2011, 118, 694–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Rossi, S.; Colucci, R.; Gallo, B.; Di Iorio, V.; della Corte, M.; Azzolini, C.; Melillo, P.; Simonelli, F. Macular abnormalities in Italian patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 98, 946–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, P.A.; Grierson, I.; Hiscott, P. Direct comparison of the migration of three cell types involved in epiretinal membrane formation. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2002, 43, 2749–2757. [Google Scholar]

- Vedantham, V.; Ramasamy, K. Pigmented epiretinal membranes caused by RPE migration: OCT-based observational case reports. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2007, 55, 148–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaissle, G.B.; May, C.A.; van de Pavert, S.A.; Wenzel, A.; Claes-May, E.; Giessl, A.; Szurman, P.; Wolfrum, U.; Wijnholds, J.; Fischer, M.D.; et al. Bone spicule pigment formation in retinitis pigmentosa: Insights from a mouse model. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2010, 248, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, K.; Ikeda, Y.; Murakami, Y.; Nakatake, S.; Tachibana, T.; Yoshida, N.; Nakao, S.; Hisatomi, T.; Yoshida, S.; Yoshitomi, T.; et al. Association Between Aqueous Flare and Epiretinal Membrane in Retinitis Pigmentosa. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2016, 57, 4282–4286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruett, R.C. Retinitis pigmentosa: Clinical observations and correlations. Trans. Am. Ophthalmol. Soc. 1983, 81, 693–735. [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda, Y.; Yoshida, N.; Murakami, Y.; Nakatake, S.; Notomi, S.; Hisatomi, T.; Enaida, H.; Ishibashi, T. Long-term Surgical Outcomes of Epiretinal Membrane in Patients with Retinitis Pigmentosa. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 13078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, G.A.; Maggiano, J.M.; Fishman, M. Foveal lesions seen in retinitis pigmentosa. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1977, 95, 1993–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitry, D.; Charteris, D.G.; Fleck, B.W.; Campbell, H.; Singh, J. The epidemiology of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: Geographical variation and clinical associations. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2010, 94, 678–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, A.; Tanaka, M. The relationship between refractive errors and retinal detachment—Analysis of 1166 retinal detachment cases. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 1988, 32, 310–315. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, T.C. The influence of refractive error and lattice degeneration on the incidence of retinal detachment. Trans. Am. Ophthalmol. Soc. 1989, 87, 143–155; discussion 155–157. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, T.; Chandra, A.; Hewitt, A.W. Current Understanding of the Genetic Architecture of Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment. Ophthalmic Genet. 2016, 37, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, A.; Poulson, A.V.; Goodburn, S.F.; Richards, A.J.; Scott, J.D.; Snead, M.P. Retinal detachment and prophylaxis in type 1 Stickler syndrome. Ophthalmology 2008, 115, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, M.; Finocchio, L.; Fujinami, K.; Fujinami-Yokokawa, Y.; Virgili, G.; Mahroo, O.A.; Webster, A.R.; Michaelides, M. X-Linked Retinoschisis: Deep Phenotyping and Genetic Characterization. Ophthalmology 2021, 129, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, P.; Fincham, G.S.; Brown, S.; Collins, D.; McNinch, A.M.; Poulson, A.V.; Richards, A.; Martin, H.; Wareham, N.; Snead, M.P. Cambridge Prophylactic Protocol, Retinal Detachment, and Stickler Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 1337–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, A.J.; Snead, M.P. Molecular Basis of Pathogenic Variants in the Fibrillar Collagens. Genes 2022, 13, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meguro, A.; Ideta, H.; Ota, M.; Ito, N.; Ideta, R.; Yonemoto, J.; Takeuchi, M.; Uemoto, R.; Nishide, T.; Iijima, Y.; et al. Common variants in the COL4A4 gene confer susceptibility to lattice degeneration of the retina. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e39300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.O.; Brennan, N.; Webster, A.R.; Michealides, M.; Muqit, M.M.K. Retinal detachment in retinitis pigmentosa. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2020, 5, e000454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham, Y.C.; Li, X.; Wong, T.Y.; Quigley, H.A.; Aung, T.; Cheng, C.Y. Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 2081–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Duan, X.; Chen, L.; Shi, J.; Liu, J.; Sun, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Tang, X. Combination of Trabeculectomy and Primary Pars Plana Vitrectomy in the Successful Treatment of Angle-Closure Glaucoma with BEST1 Mutations: Self-Controlled Case Series. Ophthalmol. Ther. 2022, 11, 2271–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uliss, A.E.; Gregor, Z.J.; Bird, A.C. Retinitis pigmentosa and retinal neovascularization. Ophthalmology 1986, 93, 1599–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, A.; Stephenson, K.A.J.; Zhu, J.; FitzSimon, S. Coats-like exudative vitreoretinopathy (CLEVER) in CEP290 inherited retinal degeneration. BMJ Case Rep. 2022, 15, e247229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moinuddin, O.; Sathrasala, S.; Jayasundera, K.T.; Branham, K.H.; Chang, E.Y.; Qian, C.X.; Recchia, F.M.; Fahim, A.T.; Besirli, C.G. Coats-like Exudative Vitreoretinopathy in Retinitis Pigmentosa: Ocular Manifestations and Treatment Outcomes. Ophthalmol. Retin. 2021, 5, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliyah, M.; Alshamrani, A.A.; Schatz, P.; Taskintuna, I.; Alzahrani, Y.; Nowilaty, S.R. Clinical spectrum, genetic associations and management outcomes of Coats-like exudative retinal vasculopathy in autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Ophthalmic Genet. 2021, 42, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).