Simple Summary

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is one of the most common cancers worldwide and is associated with tobacco use, alcohol consumption, and EBV or HPV infection. The treatment of HNSCC is improved with early detection by radiation and/or surgery, and immunotherapy. Unfortunately, many patients do not respond or develop resistance to these therapies. Here, we discuss the role of the tumor microenvironment and how cancer cells protect themselves by modulating key pathways, which may help in the development of novel therapeutics.

Abstract

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is a group of cancers arising in the oropharyngeal and laryngeal regions. Lifestyle choices such as smoking, tobacco chewing, alcohol consumption, and human papillomavirus (HPV) infection are key risk factors. Therapeutic options include surgical resection, chemoradiotherapy, EGFR-targeting therapy, and immunotherapy. However, the treatments are limited by drug resistance, relapses, and poor response to immunotherapy, especially in advanced diseases. The difference in tissue types and HPV infection status may lead to significant variations in their tumor microenvironment (TME). The heterogeneity contributes to poor treatment response and the development of therapeutic resistance. Therefore, it is critical to have a deeper understanding of the complexities and heterogeneity in TME and its role in treatment resistance. In this review, we focused on tumor heterogeneity and the role of cancer and non-cancer cells in therapeutic resistance. We discussed the studies on human HNSCC, especially HPV-negative, and presented the diversity in the tumor microenvironment and treatment response. Furthermore, we address the existing and experimental therapeutics that target therapy resistance and may lead to a better understanding of the disease and improve therapeutic outcomes.

1. Introduction

HNSCC is a group of cancers arising in the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, paranasal sinuses, nasal cavity, and salivary glands [1]. They originate in the squamous cells of the mucosa lining and often spread locally and to the surrounding lymph nodes. A recent study estimated almost 60,000 cases in 2025 and approximately 13,000 deaths in the United States [2]. In addition, GLOBACON estimates 890,000 cases and 450,000 deaths per year, making it seventh most common cancer [3]. Risk factors include alcohol and tobacco use, human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection, tobacco chewing betel leaves (paan), exposure to construction materials like asbestos, metal, ceramic, wood dust, formaldehyde, and radiation [3]. Furthermore, genetic disorders like Fanconi anemia are also associated with an increased risk of developing HNSCC [4]. Two major classifications of HNSCC are based on HPV infection status [5]. HPV-positive cancers primarily arise in lingual and palatine tonsils and are associated with a better prognosis. HPV-negative cancers occur in non-oropharyngeal sites. At the molecular level, TP53 inactivation or somatic mutation is a hallmark of HNSCC [6]. Furthermore, loss-of-function mutations in CDKN2A, PTEN, and NOTCH genes and gain-of-function mutations in HRAS and CCND1 also contribute to the malignant transformation of the cells. Such mutations often lead to the activation of major pathways such as the Ras/MAPK and PI3K-mTOR that drive proliferation [7].

The standard of care for HNSCC includes surgical resection, radiotherapy, and platinum-based chemotherapy. Targeted therapies such as EGFR inhibitors are used when patients cannot take chemotherapy. For Recurrent or Metastatic HNSCC, anti-PD1 antibody (pembrolizumab) is a standard first-line therapy, often with platinum-based chemotherapy. However, only approximately 15% to 20% of these patients achieve durable responses [8]. The treatment response in HNSCC patients largely depends on the HPV infection status. HPV-positive patients respond better to treatments like immunotherapy than HPV-negative patients. HPV infection alters the tumor microenvironment by upregulating immune infiltration and antigen presentation, and is associated with better prognosis [9,10]. Therefore, effective treatments are necessary, especially in HPV-negative HNSCC patients.

The development of therapeutic resistance in HNSCC is a complex, multi-step process that warrants a deeper understanding to improve treatment outcomes. In this review, we summarize the molecular basis of therapy resistance with a special focus on the role of the tumor microenvironment in HPV-negative patients. This will help deepen our understanding of tumor heterogeneity and may help overcome therapeutic resistance and improve treatment efficacy.

2. Tumor Microenvironment and Tumor Heterogeneity in HNSCC

HNSCC microenvironment consists of a diverse tissue composition that contributes to the tumor structure. The tumor stroma in HNSCC includes neoplastic cancer cells and non-neoplastic stromal cells such as immune cells, fibroblasts, mesenchymal cells, endothelial cells, and nerves [11]. Stomal cells comprise the majority of the TME and interact with cancer cells to modulate tumor progression. A whole-exome sequencing (WES) study from 2015 analyzed bulk tumor DNA from 300 HNSCC patient samples for intra-tumor heterogeneity [12]. They developed a method called mutant-allele tumor heterogeneity (MATH) that was able to predict the overall survival of patients. The values for individual tumors were calculated using tumor-specific mutations in a genomic locus. A higher MATH value was associated with lower survival and vice versa [12]. Here, we will discuss how cancer and non-cancer cells impact TME and contribute to tumorigenicity.

2.1. Cancer Stem Cells

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are pluripotent cells that drive the initiation, maintenance, and progression of tumors. They portray features of embryonic stem cells that retain or regain the potential of unlimited cell division and differentiation. The origin of CSCs is an area of active research, but it is widely believed that they originate from normal stem cells when they undergo several events, predominantly starting with alterations in the genome [13]. CSC populations are extremely rare in the TME, but they play a seminal role in tumor development [14]. One of the widely used CSC markers is octamer-binding transcription factor 4 (OCT4), which is primarily expressed in embryonic stem cells. In HNSCC patient samples, OCT4 was found to be differentially expressed and imparts stem-like properties to differentiated HNSCC cells. Furthermore, disruption of OCT4 attenuated the stem-like properties in these cells and limited tumor formation in vivo [15]. Nanog, CD44, CD133, and SOX2 expression were also higher in high-grade HNSCC samples compared to the low-grade tumors. The overexpression of these genes is associated with poor survival in HNSCC patients [16]. The CSC population contains cells expressing CD44 at the cell surface and BMI1 in the nucleus and possesses an extraordinary tumorigenic capacity. However, the abundance of CD44 expression in head and neck tissues made it difficult to use as a marker [17]. Interestingly, CD44 with c-met expression has been demonstrated as a very strong prognostic marker in a cohort of 105 patients [18]. High CD44 with c-met expression is associated with extremely poor clinical outcomes. Together, these studies lay a strong foundation to identify and study CSCs, especially using modern techniques such as spatial transcriptomics to delineate their role in the tumor microenvironment.

2.2. Immune Cells

The abundance and composition of immune cells in the TME have become a critical predictor of response to therapies, especially immunotherapy. The immune milieu is highly dynamic and varies significantly based on the tumor site, disease progression, and patient age, contributing to heterogeneity. Anti-tumor immunity is driven by immune cell-mediated cytotoxicity and antigen presentation. Cancer cells are usually flagged by our body to be targeted, but the tumors use a phenomenon called immunoediting to escape the surveillance [19]. Furthermore, cancers recruit immunosuppressive cells to limit the cytotoxicity from effector immune cells. Such modulations in the TME lead to dampened and dysfunctional immune responses. Hence, it is essential to understand the immune milieu and its crosstalk that leads to immune evasion to improve strategies for immunotherapy.

2.2.1. Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes

Higher tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte levels in HNSCC patients, particularly CD4 and CD8 T-cells, are associated with improved survival, and establishing them as a prognostic factor. Chemoradiation patients with high CD4 and CD8 presented a dramatic improvement in overall survival in a study involving 513 patients [20]. In the same study, high FoxP3 expression was also associated with improved overall survival in all patients, especially in chemoradiation patients. Another independent study on HNSCC patient samples presented improved overall survival associated with high cytoplasmic FoxP3 expression [21]. The authors reported FoxP3+ Treg as an independent prognostic factor in these samples, in combination with tumor stage and histological grade. This is in contrast with the general association of FoxP3+ regulatory T-cells (Tregs) with immune evasion and cancer progression in HNSCC. High FoxP3 transcript and protein levels in tongue squamous cell carcinoma patient samples have also been associated with poor survival [22]. However, the abundance of T-regulatory cells (Tregs) depends on the presence of lymphoid tissue around the tumor, and the role of FoxP3 Tregs in immune suppression may depend on the secretion of IL-12 and TGF-β in the tissues [23]. Interestingly, the subcellular localization of FoxP3 in Tregs may be vital in tumor progression. Immunofluorescence analysis of 49 OSCC patient samples revealed that subcellular localization of FoxP3 is essential to determine the clinical outcome, with cytoplasmic FoxP3 showing better survival than nuclear FoxP3 [24]. A nuclear vs. cytoplastic FoxP3 ratio can serve as a marker for recurrence in HNSCC. FoxP3, being a transcription factor, is generally located in the nucleus. However, the protein can also reside in the cytoplasm, which reduces its ability to regulate the Treg-associated gene expression and may affect its immunosuppressive functions [25]. A recent study on 354 clinical samples (including tumor and normal tissues) presented that high FoxP3 expression indeed associates with better survival in OSCC patients but such prediction requires several considerations [26]. FoxP3 expression regulates cell differentiation in cancer cells, and its role is not restricted to Tregs. The function of FoxP3 varies the isoform, subcellular localization, or the tissue origin, and may predict its clinical relevance. However, further research is needed to better understand the role of FoxP3 in HNSCC. The immune makeup within the HNSCC TME depends largely on the HPV infection status of the patients [27,28]. Partlova and colleagues analyzed 44 patient samples and demonstrated that HPV-positive tumors comprised elevated levels of CD8+ and CD4+ T-cells. CD8+ cells were isolated from the single cell suspension and stimulated in vitro, and it was demonstrated that CD8+ cells from HPV+ patients had greater potential to secrete IFNγ and IL-17. Furthermore, HPV-positive samples contained significantly higher myeloid dendritic cells (mDCs) and produced more chemokines when stimulated in vitro [27]. This demonstrates a strong immune phenotype in HNSCC patients based on HPV infection. Similarly, the analysis of 280 TCGA samples revealed increased CD8+ T-cell infiltration in addition to higher granzyme and perforin expression in HPV-positive samples [28]. The immune infiltration in HNSCC is inversely proportional to genomic instability, owing to increase immune surveillance in tumors containing chromosomally unstable cells. With the development of spatial-omics, recent studies are investigating the varying degrees of immune infiltration in HPV-negative HNSCC patients. A topological analysis of 53 HNSCC clinical samples revealed that intra-tumoral immune cells in HPV-negative HNSCC divulged varying infiltration of CD8+ T-cells. Based on the infiltration, the study classified tumors four categories—fully infiltrated, stroma-restricted, immune-excluded, and immune-desert. Fully infiltrated tumors expressed higher cytokine levels. The CD8+ T-cells were localized near tumor cells, whereas the B-cells remained isolated in exclusive niches [29]. In a separate study, tumor-associated B-cells were found to be more abundant in HPV-positive patients and were functionally involved in antibody-dependent immune responses [30]. Regulatory B-cells (Bregs) that produce adenosine (ADO) suppress T-cell function, regulated by Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) [31]. However, the abundance of ADO-producing Breg cells is less in the TME compared to the peripheral blood in patients. Further research is necessary to fully determine the role of Bregs in tumor progression and the modulation of immune responses. Together, the observations suggest that HPV status may affect immune cell infiltration. This attribute is associated with better prognosis and enhanced response to treatment in HPV-positive patients than in HPV-negative patients [32]. A summary with differences in immune composition in HPV-positive vs. HPV-negative HNSCC is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Differences in immune composition in HPV-positive and HPV-negative HNSCC.

2.2.2. Tumor-Associated Macrophages

The TME of HNSCC is characterized as immunosuppressive, dominated by the presence of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) [32,36]. In oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) patient samples, metastatic tumors had the highest percentage of CD68+ TAMs, followed by non-metastatic samples and the control. High-CD68 cells were associated with worse survival in these patients. Furthermore, the trend was similar for the expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β [37]. Such a population of TAMs is described as the M2 type, which promotes tumor progression. A study on primary nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) patient samples presented immune-cell-specific signatures using single-cell transcriptomics [38]. The authors used marker genes to compute the signatures and presented that higher scores for NK cells, dendritic cells, and macrophages were associated with better progression-free survival in these patients. Similarly, M2 polarization plays a key role in the malignant transformation of oral leukoplakia (OLP) and aids in tumor progression. OLPs without macrophage infiltration are less likely to undergo malignant transformation [39]. Macrophage polarization to M2-type is characterized by CD163 expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma, and the CD163/CD68 ratio can be used as a measure for M2 polarization [40]. A 2024 study on publicly available scRNA-seq data from 18 HNSCC samples constructed a prognostic signature with eight macrophage-related genes (MRGs) that could predict risk in HNSCC patients. Low-risk patients are more likely to respond better to immunotherapy, and vice versa [41]. This suggests that TAMs are crucial in HNSCC progression and can be used as a prognostic marker.

2.2.3. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) promote malignant progression in HNSCC. A study using 200 OSCC samples and 36 normal tissues demonstrated that MDSC infiltration was associated with poor prognosis [42]. MDSCs isolated from human tumors showed that the presence of tumor-associated MDSCs led to higher proliferation of OSCC cells in vitro. Additionally, they promoted the invasion and migration phenotype and upregulated EMT-related genes in OSCC cells. HNSCC patients also revealed higher MDSC levels in the blood, especially with gross tumors [43]. Similar observations were made in the tobacco-mimicking 4-NQO-induced oral cancer animal model, where a gradual increase in MDSCs was observed starting from hyperplasia to carcinoma. Furthermore, MDSCs impede T-cell proliferation in vitro, with a marked reduction in the presence of tumor cells. Targeting MDSCs with sunitinib improved T-cell-mediated anti-tumor immunity by promoting infiltration, reducing T-cell exhaustion, and upregulating PD-L1 expression, which sensitized the tumors to anti-PD1 therapy [44]. Hence, the successful targeting of MDSCs may help overcome resistance to immunotherapy in HNSCC.

2.2.4. Natural Killer Cells

Natural killer (NK) cell research has been in the limelight after the discovery of their significant role in anti-tumor immune response and the development of CAR-NK and NK-cell-based immunotherapy [45]. A single-cell RNA-seq study using human HNSCC samples revealed two distinct states—CD49a+ and CD49a− cells [46]. CD49a+ cells express granzyme and perforin and play an anti-tumor role, whereas CD49a− cells express NR4A2 that promotes Treg differentiation, leading to tumor suppression. A clinical trial with Metformin in combination with chemoradiotherapy induced NK-cell mediated cytotoxicity in HNSCC patients. It promoted NK cell infiltration and perforin expression via the mTOR/pSTAT1 pathway [47]. The analysis of PBMCs from HNSCC patients revealed increased TIM-3- and NKG2A-expressing exhausted NK cells compared to high CD56bright cells in healthy donors [48]. Furthermore, cetuximab, an anti-EGFR antibody, promotes IFN-γ secretion in peripheral NK cells but not in intra-tumoral NK cells. Targeting TIGIT, a co-inhibitory molecule, also improves NK cell response in vitro and in pre-clinical models. Combining allogenic NLK cells with cetuximab yielded promising anti-tumor effects in vitro and in the xenograft model [49]. A combination of chemoradiotherapy with cisplatin enhanced NK cell infiltration and cytotoxicity, and improved overall survival in HNSCC patients [50]. Furthermore, NK cells, in the presence of natural compound bitter melon, enhanced killing activity when co-cultured with HNSCC cells [51]. Bitter melon extract increased the expression of CD16, a marker for NK cell activation and granzyme B, in vitro. Additionally, Car-NK cells targeting EGFR demonstrated enhanced cytotoxicity and apoptosis induction in SCC cell lines and primary HNSCC tumor cells [52]. However, more research is needed to determine their effectiveness in animal models to determine their translational potential.

2.2.5. Antigen Presentation

In HNSCC, HLA class I antigen and associated antigen-presenting genes, such as TAP, are downregulated in primary and metastatic lesions in 25 clinical samples [53]. Histopathologic studies of HNSCC patients have revealed a significant reduction in HLA class I, TAP1, and TAP2 expression in metastatic lesions. Furthermore, lower HLA class I expression was associated with worse disease-free survival. In many cases, the antigen-presenting machinery presents functional defects despite the regular expression of antigen-presenting genes [54]. HPV infection alters antigen presentation in the TME. The analysis of TCGA data from HPV-positive oral tumors revealed an upregulation of MHC I and associated antigen presentation genes compared to HPV-negative samples. This was in contrast with in vitro studies that presented a reduction in the expression of antigen presentation genes. Despite contrasting observations, the author argued that the increase in viral-mediated antigen presentation was possibly due to the in vivo context [55]. Similarly, MHC II expressions are also upregulated in HPV-positive HNSCC patients, including both α and β chains. Additionally, associated antigen-presenting genes such as cluster of differentiation 74 (CD74), HLA-DM, HLA-DO, and their transcriptional regulators were overexpressed as well [10]. In a contrasting study, HLA-A expression was found to be significantly higher in HPV-negative patients, leading to higher clonal expansion of T-cells [56]. However, all the patients have been recipients of chemotherapy, and the difference in the HLA expression was barely significant. Overall, HPV-positive patients exhibit better antigen diversity due to the additional presence of virus-derived antigens, leading to a “hot” TME [57].

2.3. Stromal Cells

The cancer nests are protected inside a desmoplastic environment that is maintained by non-cancerous cells, including cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs), endothelial cells, and extracellular matrix [58]. Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are essential in tumor growth, with a more prominent role in extracellular matrix production [59]. CAFs originate from regular fibroblasts upon activation, primarily through transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1) from cancer cells, and comprise a significant portion of the TME [60,61]. CAFs are classified into myofibroblastic CAFs, inflammatory CAFs, and antigen-presenting CAFs [62]. In HNSCC, CAFs are predominantly myofibroblastic and are identified using alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) expression. CAFs have been reported to promote and suppress tumor progression, and such a contrasting nature is an attribute of the heterogeneity and tissue specificity, and the manner of their activation [63]. A study on 72 HNSCC patients revealed that AKT3 modulates CAF activity in the TME and is associated with poor prognosis. Loss of AKT3 in vitro resulted in a reduction in immunosuppressive activity, characterized by decreased CCL2 expression and the elevation of M1-like macrophage genes, such as IL12B and NOS2. Knockdown of PIK3CA, an upstream molecule of AKT3, drastically affected CAF viability [64]. Another study in OSCC patient samples demonstrated that CXCL12 expression by inflammatory CAFs promoted the infiltration of M2 macrophages, most likely via the CXCR4-CXCL12 axis [65]. This suggests that heterogeneous populations of CAFs alter TME and, accordingly, responses to therapies. In contrast, CAFs have also been reported to suppress stemness in cancer stem cells derived from oral tumors. CAFs from primary gingivobuccal oral tumors with low α-SMA expression reduced stemness in oral cancer stem cells through the upregulation of BMP4. These CAFs are referred to as “C1-type” and were characterized by low α-SMA and high BMP4 levels. CAFs with high α-SMA were C2 type, which promoted stemness [66]. CAFs are critical in tumor progression, and their heterogeneity and mechanisms in HNSCC need further investigation.

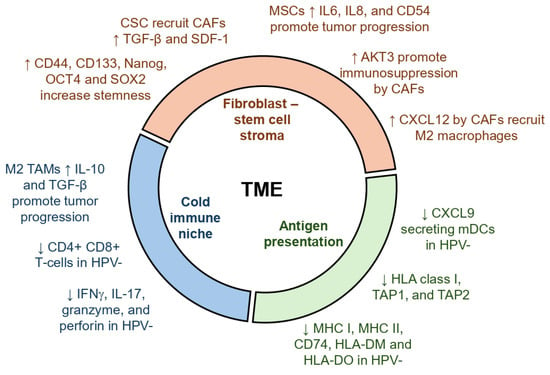

MSCs play a key role in maintaining cancer stem cells [67]. Bone marrow-derived MSCs may serve as a source for CAFs in the TME, especially in gastric cancer [68]. However, the validity of the concept in head and neck cancers is poorly studied. Nonetheless, analysis of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma patient samples revealed a greater abundance of MSCs compared to normal tissue [69]. Cell lines derived from tumors improved the migration of MSCs in vitro, driven by IL-6 and platelet-derived growth factor α (PDGFα), suggesting that a crosstalk between MSCs and cancer cells may promote desmoplasia in HNSCC. MSCs isolated from patients showed increased expression of IL6, IL8, and CD54 [70]. In a separate study, the upregulation of a connective tissue growth factor, CCN2, was identified in tongue squamous cell carcinoma samples. MSCs were the source of CCN2, and promoted cancer cell proliferation and cell migration [71]. Similarly, bone marrow-derived MSCs were reported to exhibit pro-tumorigenic properties on HNC cells in vitro, such as cell proliferation and migration, and inhibited cell death by activating the mTOR pathway [72]. In contrast, MSCs isolated from normal gingival tissue exerted anti-tumor effects in vivo and inhibited cancer cell growth through the JNK pathway in vitro [73]. The MSCs upregulated pro-apoptotic genes in cancer cells and downregulated cell cycle and proliferation genes. Hence, the role of MSCs in tumor growth may be tissue dependent in HNSCC. A summary of myriad roles of cells in the TME is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Role of various cells in the tumor microenvironment in HNSCC. Key events are broadly classified into three groups: stem cells and fibroblasts, immune cells, and antigen presentation. Up arrows indicate events upregulated and down arrows indicate events downregulated in the TME, which promote tumor progression.

3. Therapeutics and Development of Resistance in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Current therapeutics for HNSCC include the use of surgical interventions for early-stage cancers in addition to radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Advanced diseases are treated using targeted therapy and immunotherapy [74,75]. The most widely used chemotherapy in HNSCC is cisplatin, a platinum-based anti-cancer drug, combined with fluorouracil and taxanes like docetaxel and paclitaxel. However, a major limitation of chemotherapy is the development of resistance. Immunotherapies include nivolumab and pembrolizumab, which are anti-PD1 monoclonal antibodies that have demonstrated promising outcomes, especially in patients with a higher PD-L1 expression and a greater mutational burden [76,77,78]. Immunotherapy has been able to improve overall survival in HNSCC patients but the treatment is limited by severe adverse effects and a low response rate [75,79]. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is a tyrosine kinase present on the plasma membrane. The EGFR signaling pathway is fundamental for cell proliferation and is one of the most widely targeted signaling pathways. EGFR-targeting chimeric monoclonal antibody cetuximab has been approved by the FDA to treat HNSCC. Cetuximab sensitizes tumors to chemoradiation therapy and is used for locally advanced HNSCCs. However, it induces serious skin toxicity which limits its use in the clinic [79,80]. Gefitinib, a small molecule EGFR inhibitor, in combination with IFN-α, delayed tumor growth in a HNSCC xenograft model. Gefitinib suppressed EGFR activation and induced a pro-apoptotic effects of IFN-α [81].

Novel strategies under investigation include experimental therapeutics or FDA approved drugs which are being repurposed, with a special focus on combination therapies. EGFR inhibitor erlotinib with anti-VEGF antibody bevacizumab, in combination with radiation therapy, showed remarkable tumor inhibition in a xenograft model [82]. Conversely, the therapy failed to confer clinical benefits due to resistance via upregulation of nerve growth factor (NGF)-TrkA axis [83]. Recently, a pan-HER (HER is a part of the EGFR family) inhibitor, dacomitinib, and PI3K/mTOR inhibitor, gedatolisib, successfully attenuated tumor growth in combination with radiation therapy in xenograft models. Interestingly, they did not portray additional inhibition when used simultaneously, which suggested a complicated biology of dual inhibition of EGFR and PI3K/mTOR pathways [84]. Like bevacizumab, a dual VEGF-2 and FGFR1 inhibitor, lenvatinib targets angiogenesis and portrays robust anti-tumor properties in nasopharyngeal carcinoma [85,86]. Additional VEGF inhibitors, such as linifanib, accentuated radiosensitivity in radio-resistant HNSCC cells via STAT3 inhibition and the induction of apoptosis [87]. Fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) inhibitor AZD4547 could block the phosphorylation of MAPK and promote radiosensitivity in HNSCC cell lines. Furthermore, AZD4547 arrested tumor growth in xenograft and PDX models [88]. Other such molecules have been developed to target c-MET [89,90], MEK [91,92], JAK/STAT [93,94], and CDK4/6 [95] in HNSCC, but the efficacy was limited by therapeutic resistance. Furthermore, the oral administration of bitter melon extract (BME) reduced tumor growth in an oral cancer xenograft model by disrupting cell cycle genes [96]. A representative list of recent clinical trials targeting TME is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Recent and ongoing clinical trials with strategies targeting TME in HNSCC.

Strategies Targeting Therapeutic Resistance

Cancer is more than a mass of proliferating cells and is a complex heterogeneous tissue that includes cancer and non-cancer cells in its microenvironment. The tumor microenvironment supports tumor growth and aids in stress mitigation upon treatment [97]. Broadly, cancers exhibit two types of stress response—primary and adaptive. Primary stress responses include phenomena such as the Warburg effect, where cancer cells utilize glycolysis to generate energy more efficiently, even in the presence of oxygen, and the stress eliciting the primary response is predominantly innate and is generated due to the natural course of tumor growth. However, an adaptive response develops over time in the presence of external stress, such as therapies. Both tumor intrinsic (genetic) and tumor extrinsic (non-genetic) pathways drive the development of acquired resistance [98]. Hence, the mechanisms arise from dynamic evolutionary processes where the genotype (mutations) leads to epigenetic plasticity. As the tumor grows, it gathers mutations and becomes genetically heterogeneous. The heterogeneity results in distinct molecular signatures, leading to varying sensitivity to therapies [99].

In HNSCC, key pathways that contribute to the development of resistance are epigenetic modulations, the deregulation in DNA repair pathways, the evasion of programmed cell death, and the re-wiring of major cell signaling and metabolic pathways [100]. Such changes promote resistance to radiation therapies, chemotherapies, targeted therapies, and immunotherapies. Major pathways that contribute to resistance are histone acetylation and epigenetics, defects in DNA repair, evasion of cell death, and immunosuppression [100,101]. Epigenetic alterations that promote resistance are DNA methylation, histone modifications, and miRNA alterations [102]. For example, DNA methylation is profoundly associated with resistance to radiation therapy. A study using two HNSCC cell lines—one radiation sensitive and one radiation resistant—showed that radiation-resistant cells had increased DNA methylation and differentially expressed 84 related genes between the cells [103].

Cisplatin is one of the most widely used chemotherapies, but many patients develop resistance, leading to relapse. The resistance is attributed to increased DNA repair, decreased cellular uptake of cisplatin, and cytosolic inactivation of cisplatin [104]. In HNSCC, high levels of ERCC1, an endonuclease, are associated with the increased nucleotide excision repair (NER) pathway. NER promotes cisplatin resistance by upregulating double-strand break repair induced by radiation. A clinical study revealed that ERCC1 can be used as a predictor for treatment response in HNSCC patients [104,105,106]. Furthermore, accumulation of miR-21 upregulates the expression of PDCD4 which promotes resistance to cisplatin [107]. Similarly, miR-23a inhibits cisplatin-induced apoptosis in tongue squamous cell carcinoma cells via the upregulation of JNK-dependent Twist expression [108]. Wild-type p53 and high levels of Bcl-xl are also associated with cisplatin resistance. Bcl-xl inhibits programmed cell death and promotes cisplatin resistance. High Bcl-xl is associated with poor outcomes in HNSCC [109]. Targeting Bcl-xl and other BCL2 family proteins using small molecules has demonstrated anti-tumor properties in HNSCC, especially in association with MCL-1 blockers [110]. CSCs promote chemoresistance and tumor progression, attributed to their unlimited self-renewal capability and rapid proliferative potential. Small molecules such as ABT-737 have been used to target CSCs in HNSCC. ABT-737 is a BH3-mimetic molecule that inhibits anti-apoptotic BCL-2 proteins to induce programmed cell death [111]. This molecule specifically targets cancer cells and can be used as an adjuvant to radiotherapy.

EGFR-targeting agent cetuximab is the only EGFR-targeted therapy approved by the FDA. Studies using cetuximab resistance models revealed a nuclear translocation of EGFR in resistance cells, in addition to the upregulation of MAPK, Ras, and mTOR/AKT signaling. Furthermore, the upregulation of EMT markers such as CD44 was observed as well [112]. Interestingly, whole-exome and RNA sequencing of HNSCC biopsies pre- and post-cetuximab treatment identified a mutation in the extracellular domain of EGFR. The mutation disrupted cetuximab binding to EGFR, suggesting a novel mechanism of cetuximab resistance and potentially a general mechanism of acquired resistance against targeted therapies [113]. In addition, metabolic reprogramming also contributes to the anti-EGFR therapy resistance in HNSCC. Cetuximab-resistant cells display a reprogramming of lipid metabolism mediated by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα). Increased fatty acid uptake and stearoyl-CoA desaturase activity made the cells resistant to lipotoxicity, mediated by PPARα [114]. Momordicine-I (M-I) is a bioactive, stable, and non-toxic metabolite present in bitter melon [115]. M-I treatment suppresses HNSCC growth in vitro and in vivo by altering lipid metabolism and the induction of autophagy, leading to a reduction in tumor volume in animal models [116]. Resistance to EGFR therapies is attributed to reduced EGFR expression and the activation of compensatory pathways upon EGFR blocking [117]. Combining cetuximab with M-I may yield better outcome in HNSCC models and needs to be validated. Metabolic reprogramming contributes to the resistance of targeted therapies, and disrupting those pathways may provide a therapeutic window in HNSCC.

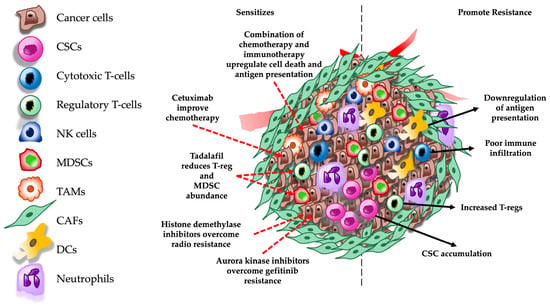

Resistance to immunotherapy is an area of active research in HNSCC. As mentioned earlier, HPV infection status plays a key role in defining the immune signature in the TME of HNSCC. HPV-positive patients generally present better tumor infiltration of immune cells, which is associated with better outcomes. However, HPV-negative tumors display an immunosuppressive environment characterized by poor tumor infiltration and the inadequate antigen presentation associated with lower mutational burden. Furthermore, TME also consists of higher immunosuppressive cells, such as T-regs and MDSCs [101]. Tumor galectin-1 (Gal-1) levels were inversely related to immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) treatment in HNSCC patients [118]. Gal-1 promoted immunosuppression by inhibiting T-cell infiltration. Likewise, the inhibition of Gal-1 resensitized the tumors to immunotherapy and significantly reduced tumor growth when combined with radiation therapy. To overcome the lack of antigen presentation, a combination of cisplatin and anti-PD1 immunotherapy was used under the rationale that cisplatin may enhance antigen presentation in the TME by inducing immunogenic cell death [119]. This study showed that sublethal doses of cisplatin in combination with anti-PD1 delayed tumor growth in animal models. Together, this suggests that the induction of immunogenic cell death and inhibiting molecules like Gal-1 may improve immunotherapy in HNSCC. M-I treatment displays robust anti-tumor effects in mouse HNSCC xenograft tumors by affecting the TAM population [120]. M-I treatment promotes a switch from M2 to M1 phenotype, as demonstrated by an inhibition of Arg1 expression. Furthermore, the study presented a reduction in the expression of myeloid cell differentiation factor Sfln4 and neutrophil chemoattractant Cxcl3. M-I treatment also downregulated the expression of PD1, PD-L1, and FoxP3 in the tumor, suggesting a strong candidate for immunotherapy in HNSCC [120]. Some key mechanisms promoting therapeutic resistance and strategies used to overcome resistance are listed in Table 3. Furthermore, a schematic representation of these mechanisms is depicted in Figure 2. Overall, poor immune infiltration with increased immune suppressive mechanisms such as an increase in T-reg and MDSC population and decrease in antigen presentation in addition to the accumulation of CSCs promote resistance to chemotherapy and immunotherapy. However, targeting these mechanisms using a combination of chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and/or targeted therapy such as cetuximab, tadalafil, and aurora kinase inhibitors have exhibited significant improvements in therapeutic outcomes.

Table 3.

Mechanisms of therapeutic resistance and strategies targeting resistance in HNSCC.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of molecular mechanisms involved in therapeutic resistance and pathways targeted to overcome resistance in the TME. Red dashed arrows indicate therapeutic targets and black dashed arrows indicate mechanisms that promote therapeutic resistance in the TME. CSCs = cancer stem cells; NK = natural killer; MDSCs = myeloid derived suppressor cells; TAMs = tumor-associated macrophages; CAFs = cancer associated fibroblasts; and DCs = dendritic cells.

4. Emerging Areas in HNSCC TME Research

The development of spatial technology and the integration of multi-omics are state-of-the-art methods that are providing novel insights that may help us improve existing therapies, especially immunotherapy [156,157]. Single-cell RNA-seq helped us study the gene expression in a specific cell type within the TME and adding spatial knowledge allowed us to visualize the proximity of such signatures. For example, a recent study using surgery samples from HNSCC patients revealed that CAFs overexpressing MHC-I in the stroma limits CD8+ cell infiltration by enriching galectin-9 production, which is the ligand for Tim-3 in CD8+ cells. This engages the CD8+ T-cells in the tumor stroma and inhibits immune infiltration into the tumor nest [158]. Similarly, a study using four male, HPV-negative HNSCC patient samples revealed that immunologically active tumors demonstrate a proximity of regions that are homogenous for immune cells, such as CD8+ T-cells. Furthermore, colocalization of PD1 high cytotoxic T-cells with cytotoxic T-cells demonstrate greater exhaustion, despite having high immune infiltration, leading to poor anti-tumor immune response [33].

The oral, gut, or tumor microbiome have a significant impact on the response to immunotherapy in HNSCC. A large study including 2724 patients demonstrated a significant decrease in the efficacy immunotherapy pembrolizumab when administered with antibiotics. The authors hypothesized that the difference was most likely due to a change in gut microbiome and warranted detailed microbiome study in a clinical setting [159]. Another study on early stage HNSCC patients treated with immunotherapy durvalumab revealed no change in the oral microbiome. The differences observed were owed to the presence of HPV infection [160]. The small sample size and the duration of the study may have different outcomes. However, the endogenous microbiome may play little role in the efficacy of immunotherapy, but the use of antibiotics and disrupting natural microbiome alter the response. Moreover, additional checkpoint blockers must be examined to achieve a more holistic understanding.

5. Future Perspectives

HNSCC is composed of a heterogeneous group of cancers with diverse anatomical locations which have distinct tumor microenvironments. Despite recent advances, HNSCC treatment is limited by the lack of effective targeted therapies, resistance to chemoradiation therapy, and the low response rate to immunotherapy, especially in HPV-negative patients. Therefore, targeting the tumor microenvironment to improve response and overcoming therapeutic resistance remain key challenges in head and neck cancers. A phase 3 clinical trial on patients with locally advanced HNSCC revealed that neoadjuvant and adjuvant administration of pembrolizumab in addition to chemoradiation therapy significantly improved event-free survival [161]. For patients unfit for chemotherapy, a combination of radiotherapy (RT) and pembrolizumab/cetuximab has been tested. However, RT + pembrolizumab did not improve tumor control in comparison with RT + cetuximab, but the RT + pembrolizumab combination appeared to be more tolerable [162].

In addition to PD-L1, which is most widely used biomarker, the identification of more novel biomarkers is necessary to predict the outcome of immunotherapy response. Secretome analysis of patient-derived HNSCC explants revealed transcriptome signatures that were defined as activation (Act) and infiltration (Inf) phenotypes [163]. The Act phenotype included expression of markers such as IFNγ, GZMH, and PD-L1, whereas the Inf phenotype included T-cell markers like CD4 and CD8. Both phenotypes were correlated with T-cell functionality and could predict survival and response to immunotherapy. Interestingly, the Inf phenotype was closely associated with HPV-positive patients, highlighting the importance of HPV status in treatment response. Nevertheless, a larger and more diverse cohort of patients may strengthen the observation and may be potentially used in the clinic. Recently, tertiary lymphoid structures (TLSs) are studied to predict immunotherapy outcomes. TLSs are generally described as an immune niche that replicates secondary lymphoid organs with CD20+ B-cells at the core surrounded by CD3+ T-cells, including CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells [164,165,166]. In 247 HPV-negative HNSCC, the presence of tertiary lymphoid structures (TLSs) correlated with better survival and an improved response to immunotherapy [167]. The immune stratification using transcriptomics and IHC data from patients provides a robust platform to develop immune subtypes and may serve as a promising strategy to improve immunotherapy, especially in HPV-negative patients. Furthermore, overexpressing TNFSF14 (also known as LIGHT) can improve vasculature and promote TLS formation in HNSCC-negative tumors via lymphotoxin β receptor (LTβR) signaling [168]. LIGHT induces chemokine production and boosts T-cell recruitment to tumors and helps overcome resistance to ICIs [169,170]. Additionally, BME and M-I treatment has exhibited robust anti-tumor effects in various HPV-negative HNSCC pre-clinical models, especially in immunotherapy resistant MOC2 tumors [120,171]. However, additional research is necessary to investigate the potency in combination with chemotherapy or ICIs, which may improve therapeutic outcomes in HPV-negative patients. Further, clinical studies will support the findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, writing, and editing, A.B. and R.B.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grant R01 DE024942 from National Institutes of Health.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| AKT3 | AKT Serine/Threonine Kinase 3 |

| BCL2 | B-Cell Lymphoma 2 |

| BME | Bitter Melon Extract |

| CAF | Cancer Associated Fibroblast |

| CCN2 | Cellular Communication Network Factor 2 |

| CCND1 | Cyclin D1 |

| CD | Cluster of Differentiation |

| CDK | Cyclin-Dependent Kinase |

| CDKN2A | Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Inhibitor 2A |

| CSC | Cancer Stem Cell |

| CTLA4 | Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte-Associated Protein 4 |

| CXCL9 | C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand |

| DMBA | 7,12-Dimethylbenz(A) Anthracene |

| EGFR | Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor |

| EMT | Epithelial-To-Mesenchymal Transition |

| FoxP3 | Forkhead Box P3 |

| GMDSC | Granulocytic Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cell |

| HER | Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor |

| HLA | Human Leukocyte Antigen |

| HNSCC | Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| HPV | Human Papillomavirus |

| HRAS | Harvey Rat Sarcoma Virus |

| IL | Interleukin |

| JAK/STAT | Janus Kinase/Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 Pathway |

| JNK | C-Jun N-Terminal Kinase |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| MATH | Mutant-Allele Tumor Heterogeneity |

| MCL | Myeloid Cell Leukemia |

| mDC | Myeloid Dendritic Cell |

| MDSC | Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cell |

| MRG | Macrophage-Related Gene |

| MSC | Mesenchymal Stem Cell |

| mTOR | Mammalian Target of Rapamycin |

| NER | Nucleotide Excision Repair |

| NGF | Nerve Growth Factor |

| NOS2 | Nitric Oxide Synthase 2 |

| NOTCH | Neurogenic Locus Notch Homolog Protein |

| NPC | Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma |

| OCT4 | Octamer-Binding Transcription Factor 4 |

| OLP | Oral Leukoplakia |

| OSCC | Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| PD-L1 | Programmed Cell Death Ligand 1 |

| PD1 | Programmed Cell Death Protein 1 |

| PDCD4 | Programmed Cell Death 4 |

| PDGF | Platelet-Derived Growth Factor |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase |

| PIK3 | Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-Bisphosphate 3-Kinase |

| PPAR | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and Tensin Homolog |

| SMA | Smooth Muscle Actin |

| SOX | SRY-Box Transcription Factor |

| T-Reg | Regulatory T-Cell |

| TAM | Tumor-Associated Macrophage |

| TAP | Transporter Associated with Antigen Processing |

| TGF | Transforming Growth Factor |

| TIL | Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocyte |

| TME | Tumor Microenvironment |

| TRKa | Tropomyosin Receptor Kinase A |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| WES | Whole-Exome Sequencing |

References

- Chow, L.Q.M. Head and Neck Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Kratzer, T.B.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2025, 75, 10–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barsouk, A.; Aluru, J.S.; Rawla, P.; Saginala, K.; Barsouk, A.; Barsouk, A.; Aluru, J.S.; Rawla, P.; Saginala, K.; Barsouk, A. Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Prevention of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Med. Sci. 2023, 11, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beddok, A.; Krieger, S.; Castera, L.; Stoppa-Lyonnet, D.; Thariat, J. Management of Fanconi Anemia patients with head and neck carcinoma: Diagnosis and treatment adaptation. Oral Oncol. 2020, 108, 104816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, S.I.; Westra, W.H.; Pai, S.I.; Westra, W.H. Molecular Pathology of Head and Neck Cancer: Implications for Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Treatment. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2009, 4, 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stransky, N.; Egloff, A.M.; Tward, A.D.; Kostic, A.D.; Cibulskis, K.; Sivachenko, A.; Kryukov, G.V.; Lawrence, M.S.; Sougnez, C.; McKenna, A.; et al. The Mutational Landscape of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Science 2011, 333, 1157–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parashar, P.; Hungyo, H.; Jain, A.; Ahmad, S.; Tandon, V. Unraveling molecular mechanisms of head and neck cancer. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2022, 178, 103778. [Google Scholar]

- Sim, E.S.; Nguyen, H.C.B.; Hanna, G.J.; Uppaluri, R. Immunotherapy in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2025, 151, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, R.; Chung, C.H. Advanced Human Papillomavirus–Negative Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Unmet Need and Emerging Therapies. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2024, 23, 1717–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gameiro, S.F.; Ghasemi, F.; Barrett, J.W.; Nichols, A.C.; Mymryk, J.S.; Gameiro, S.F.; Ghasemi, F.; Barrett, J.W.; Nichols, A.C.; Mymryk, J.S. High Level Expression of MHC-II in HPV+ Head and Neck Cancers Suggests that Tumor Epithelial Cells Serve an Important Role as Accessory Antigen Presenting Cells. Cancers 2019, 11, 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltanova, B.; Raudenska, M.; Masarik, M.; Peltanova, B.; Raudenska, M.; Masarik, M. Effect of tumor microenvironment on pathogenesis of the head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: A systematic review. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mroz, E.A.; Tward, A.M.; Hammon, R.J.; Ren, Y.; Rocco, J.W. Intra-tumor Genetic Heterogeneity and Mortality in Head and Neck Cancer: Analysis of Data from The Cancer Genome Atlas. PLoS Med. 2015, 12, e1001786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, Y.; Cao, D.; Bu, Y.; Cao, D. The origin of cancer stem cells. Front. Biosci. 2012, 4, 819–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maharajan, N.; Roufaeil, D.B.; Brown, R.A.; Portney, B.A.; Banerjee, A.; Zalzman, M. Cancer Stem Cell Mechanisms and Targeted Therapeutic Strategies in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2025, 634, 218015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, B.S.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, J.M.; Huang, S.; Kim, S.H.; Rho, Y.S.; Bae, W.J.; Kang, H.J.; Kim, Y.S.; Moon, J.H.; et al. Oct4 is a critical regulator of stemness in head and neck squamous carcinoma cells. Oncogene 2014, 34, 2317–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, S.-H.; Yu, C.-C.; Huang, C.-Y.; Lin, S.-C.; Liu, C.-J.; Tsai, T.-H.; Chou, S.-H.; Chien, C.-S.; Ku, H.-H.; Lo, J.-F. Positive Correlations of Oct-4 and Nanog in Oral Cancer Stem-Like Cells and High-Grade Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 4085–4095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wei, Y.; Hummel, M.; Hoffmann, T.K.; Gross, M.; Kaufmann, A.M.; Albers, A.E. Evidence for Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Cancer Stem Cells of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e16466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baschnagel, A.M.; Tonlaar, N.; Eskandari, M.; Kumar, T.; Williams, L.; Hanna, A.; Pruetz, B.L.; Wilson, G.D. Combined CD44, c-MET, and EGFR expression in p16-positive and p16-negative head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2017, 46, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, D.; Gubin, M.M.; Schreiber, R.D.; Smyth, M.J. New insights into cancer immunoediting and its three component phases—Elimination, equilibrium and escape. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2014, 27, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.; Bellile, E.; Thomas, D.; McHugh, J.; Rozek, L.; Virani, S.; Peterson, L.; Carey, T.E.; Walline, H.; Moyer, J.; et al. Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes and survival in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck 2016, 38, 1074–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seminerio, I.; Descamps, G.; Dupont, S.; Marrez, L.d.; Laigle, J.-A.; Lechien, J.R.; Kindt, N.; Journe, F.; Saussez, S.; Seminerio, I.; et al. Infiltration of FoxP3+ Regulatory T Cells is a Strong and Independent Prognostic Factor in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancers 2019, 11, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggioni, D.; Pignataro, L.; Garavello, W. T-helper and T-regulatory cells modulation in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. OncoImmunology 2017, 6, 1325066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, T.; Nishikawa, H.; Wada, H.; Nagano, Y.; Sugiyama, D.; Atarashi, K.; Maeda, Y.; Hamaguchi, M.; Ohkura, N.; Sato, E.; et al. Two FOXP3+CD4+ T cell subpopulations distinctly control the prognosis of colorectal cancers. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 679–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weed, D.T.; Walker, G.; Fuente, A.C.D.L.; Nazarian, R.; Vella, J.L.; Gomez-Fernandez, C.R.; Serafini, P. FOXP3 Subcellular Localization Predicts Recurrence in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magg, T.; Mannert, J.; Ellwart, J.W.; Schmid, I.; Albert, M.H. Subcellular localization of FOXP3 in human regulatory and nonregulatory T cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2012, 42, 1627–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, C.; Song, L.; Ma, Z.; Liu, H.; Su, Z.; Xia, M.; Li, J.; Jiang, L.; et al. Expression of FoxP3 in oral squamous cell carcinoma and its biological significance. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partlová, S.; Bouček, J.; Kloudová, K.; Lukešová, E.; Zábrodský, M.; Grega, M.; Fučíková, J.; Truxová, I.; Tachezy, R.; Špíšek, R.; et al. Distinct patterns of intratumoral immune cell infiltrates in patients with HPV-associated compared to non-virally induced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. OncoImmunology 2015, 4, 965570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, R.; Şenbabaoğlu, Y.; Desrichard, A.; Havel, J.J.; Dalin, M.G.; Riaz, N.; Lee, K.-W.; Ganly, I.; Hakimi, A.A.; Chan, T.A.; et al. The head and neck cancer immune landscape and its immunotherapeutic implications. JCI Insight 2016, 1, e89829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muijlwijk, T.; Nijenhuis, D.N.L.M.; Ganzevles, S.H.; Ekhlas, F.; Ballesteros-Merino, C.; Peferoen, L.A.N.; Bloemena, E.; A Fox, B.; Poell, J.B.; Leemans, C.R.; et al. Immune cell topography of head and neck cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2024, 12, e009550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechner, A.; Schlößer, H.A.; Thelen, M.; Wennhold, K.; Rothschild, S.I.; Gilles, R.; Quaas, A.; Siefer, O.G.; Huebbers, C.U.; Cukuroglu, E.; et al. Tumor-associated B cells and humoral immune response in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. OncoImmunology 2019, 8, 1535293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeske, S.S.; Brand, M.; Ziebart, A.; Laban, S.; Doescher, J.; Greve, J.; Jackson, E.K.; Hoffmann, T.K.; Brunner, C.; Schuler, P.J.; et al. Adenosine-producing regulatory B cells in head and neck cancer. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2020, 69, 1205–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.E.; Burtness, B.; Leemans, C.R.; Lui, V.W.Y.; Bauman, J.E.; Grandis, J.R.; Johnson, D.E.; Burtness, B.; Leemans, C.R.; Lui, V.W.Y.; et al. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2020, 6, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwing, N.; von Voithenberg, L.V.; Alberti, L.; Gabriel, S.M.; Rodriguez, J.M.M.; Feddersen, R.; Foy, J.-P.; Damiola, F.; Gadot, N.; Saintigny, P.; et al. Mapping immune activity in HPV-negative head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: A spatial multiomics analysis. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, e011851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seiwert, T.Y.; Burtness, B.; Mehra, R.; Weiss, J.; Berger, R.; Eder, J.P.; Heath, K.; McClanahan, T.; Lunceford, J.; Gause, C.; et al. Safety and clinical activity of pembrolizumab for treatment of recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (KEYNOTE-012): An open-label, multicentre, phase 1b trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 956–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, S.F.; Vu, L.; Spanos, W.C.; Pyeon, D.; Powell, S.F.; Vu, L.; Spanos, W.C.; Pyeon, D. The Key Differences between Human Papillomavirus-Positive and -Negative Head and Neck Cancers: Biological and Clinical Implications. Cancers 2021, 13, 5206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liao, J.; Chen, B.; Wang, Q. Heterogeneity of the tumor immune cell microenvironment revealed by single-cell sequencing in head and neck cancer. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2025, 209, 104677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, N.L.; Valadares, M.C.; Souza, P.P.C.; Mendonça, E.F.; Oliveira, J.C.; Silva, T.A.; Batista, A.C. Tumor-associated macrophages and the profile of inflammatory cytokines in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2013, 49, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-P.; Yin, J.-H.; Li, W.-F.; Li, H.-J.; Chen, D.-P.; Zhang, C.-J.; Lv, J.-W.; Wang, Y.-Q.; Li, X.-M.; Li, J.-Y.; et al. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals regulators underlying immune cell diversity and immune subtypes associated with prognosis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 1024–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M.; Wehrhan, F.; Baran, C.; Agaimy, A.; Büttner-Herold, M.; Öztürk, H.; Neubauer, K.; Wickenhauser, C.; Kesting, M.; Ries, J.; et al. Malignant transformation of oral leukoplakia is associated with macrophage polarization. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M.; Moebius, P.; Büttner-Herold, M.; Amann, K.; Preidl, R.; Neukam, F.W.; Wehrhan, F.; Weber, M.; Moebius, P.; Büttner-Herold, M.; et al. Macrophage polarisation changes within the time between diagnostic biopsy and tumour resection in oral squamous cell carcinomas—An immunohistochemical study. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 113, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Liu, Q.; Liu, L.; Liu, Q. Characterization of macrophages in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and development of MRG-based risk signature. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, X.; Fan, H.-Y.; Tang, Y.-L.; Wang, S.-S.; Cao, M.-X.; Wang, H.-F.; Dai, L.-L.; Wang, K.; Yu, X.-H.; Wu, J.-B.; et al. Myeloid derived suppressor cells contribute to the malignant progression of oral squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.-C.; Lai, C.-H.; Chuang, H.-C.; Lin, P.-Y.; Chen, M.-F. Inflammation-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cells associated with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Head Neck 2017, 39, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Lin, W.-P.; Su, W.; Wu, Z.-Z.; Yang, Q.-C.; Wang, S.; Sun, T.-G.; Huang, C.-F.; Wang, X.-L.; Sun, Z.-J. Sunitinib attenuates reactive MDSCs enhancing anti-tumor immunity in HNSCC. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 119, 110243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, S.; Zhao, M.; Zhu, J.; Li, T.; Yan, M.; Xing, K.; Liu, P.; Yu, S.; Ma, J.; He, H. Natural killer cells: A future star for immunotherapy of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1442673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Nieves, U.Y.; Tay, J.K.; Saumyaa, S.; Horowitz, N.B.; Shin, J.H.; Mohammad, I.A.; Luca, B.; Mundy, D.C.; Gulati, G.S.; Bedi, N.; et al. Landscape of innate lymphoid cells in human head and neck cancer reveals divergent NK cell states in the tumor microenvironment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2101169118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crist, M.; Yaniv, B.; Palackdharry, S.; A Lehn, M.; Medvedovic, M.; Stone, T.; Gulati, S.; Karivedu, V.; Borchers, M.; Fuhrman, B.; et al. Metformin increases natural killer cell functions in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma through CXCL1 inhibition. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e005632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mele, D.; Pessino, G.; Trisolini, G.; Luchena, A.; Benazzo, M.; Morbini, P.; Mantovani, S.; Oliviero, B.; Mondelli, M.U.; Varchetta, S. Impaired intratumoral natural killer cell function in head and neck carcinoma. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 997806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Han, M.; Kim, G.; Son, W.; Kim, J.; Gil, M.; Rhee, Y.-H.; Sim, N.S.; Kim, C.G.; Kim, H.R.; et al. Preclinical investigation of anti-tumor efficacy of allogeneic natural killer cells combined with cetuximab for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2025, 74, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, E.K.; Chu, T.-H.; Vo, M.-C.; Nguyen, H.P.Q.; Lee, D.H.; Lee, J.K.; Lim, S.C.; Jung, S.-H.; Yoon, T.-M.; Yoon, M.S.; et al. Natural killer cells have a synergistic anti-tumor effect in combination with chemoradiotherapy against head and neck cancer. Cytotherapy 2022, 24, 905–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Muhammad, N.; Steele, R.; Kornbluth, J.; Ray, R.B. Bitter Melon Enhances Natural Killer–Mediated Toxicity against Head and Neck Cancer Cells. Cancer Prev. Res. 2017, 10, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak, J.; Bentele, M.; Kutle, I.; Zimmermann, K.; Lühmann, J.L.; Steinemann, D.; Kloess, S.; Koehl, U.; Roßberg, W.; Ahmed, A.; et al. CAR-NK Cells Targeting HER1 (EGFR) Show Efficient Anti-Tumor Activity against Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (HNSCC). Cancers 2023, 15, 3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandoh, N.; Ogino, T.; Katayama, A.; Takahara, M.; Katada, A.; Hayashi, T.; Harabuchi, Y. HLA class I antigen and transporter associated with antigen processing downregulation in metastatic lesions of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma as a marker of poor prognosis. Oncol. Rep. 2010, 23, 933–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferris, R.L.; Whiteside, T.L.; Ferrone, S. Immune Escape Associated with Functional Defects in Antigen-Processing Machinery in Head and Neck Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 3890–3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gameiro, S.F.; Zhang, A.; Ghasemi, F.; Barrett, J.W.; Nichols, A.C.; Mymryk, J.S.; Gameiro, S.F.; Zhang, A.; Ghasemi, F.; Barrett, J.W.; et al. Analysis of Class I Major Histocompatibility Complex Gene Transcription in Human Tumors Caused by Human Papillomavirus Infection. Viruses 2017, 9, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saloura, V.; Fatima, A.; Zewde, M.; Kiyotani, K.; Brisson, R.; Park, J.-H.; Ikeda, Y.; Vougiouklakis, T.; Bao, R.; Khattri, A.; et al. Characterization of the T-Cell Receptor Repertoire and Immune Microenvironment in Patients with Locoregionally Advanced Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 4897–4907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conarty, J.P.; Wieland, A.; Conarty, J.P.; Wieland, A. The Tumor-Specific Immune Landscape in HPV+ Head and Neck Cancer. Viruses 2023, 15, 1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markwell, S.M.; Weed, S.A.; Markwell, S.M.; Weed, S.A. Tumor and Stromal-Based Contributions to Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Invasion. Cancers 2015, 7, 382–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; González-Maroto, C.; Tavassoli, M.; Li, X.; González-Maroto, C.; Tavassoli, M. Crosstalk between CAFs and tumour cells in head and neck cancer. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Hsueh, C.-Y.; Shen, Y.-J.; Guo, Y.; Huang, J.-M.; Zhang, Y.-F.; Li, J.-Y.; Gong, H.-L.; Zhou, L. Small extracellular vesicle-packaged TGFβ1 promotes the reprogramming of normal fibroblasts into cancer-associated fibroblasts by regulating fibronectin in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2021, 517, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, Y.; Acar, A.; Eaton, E.N.; Mellody, K.T.; Scheel, C.; Ben-Porath, I.; Onder, T.T.; Wang, Z.C.; Richardson, A.L.; Weinberg, R.A.; et al. Autocrine TGF-β and stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1) signaling drives the evolution of tumor-promoting mammary stromal myofibroblasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 20009–20014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Xia, C.; Ding, L.; Pu, Y.; Hu, X.; Cai, H.; Hu, Q. Integrated analysis of single-cell RNA-seq and bulk RNA-seq reveals distinct cancer-associated fibroblasts in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, C.; Huang, Q.; Hu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, C.; Huang, Q. Heterogeneity of cancer-associated fibroblasts in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: Opportunities and challenges. Cell Death Discov. 2023, 9, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, H.; Rokudai, S.; Kawabata-Iwakawa, R.; Sakakura, K.; Oyama, T.; Nishiyama, M.; Chikamatsu, K.; Takahashi, H.; Rokudai, S.; Kawabata-Iwakawa, R.; et al. AKT3 Is a Novel Regulator of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancers 2021, 13, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhai, Y.; Li, F.; Shi, X.; Ying, M. Single-Cell Profiling Reveals Heterogeneity of Primary and Lymph Node Metastatic Tumors and Immune Cell Populations and Discovers Important Prognostic Significance of CCDC43 in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 843322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.K.; Vipparthi, K.; Thatikonda, V.; Arun, I.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Sharan, R.; Arun, P.; Singh, S.; Patel, A.K.; Vipparthi, K.; et al. A subtype of cancer-associated fibroblasts with lower expression of alpha-smooth muscle actin suppresses stemness through BMP4 in oral carcinoma. Oncogenesis 2018, 7, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Ginestier, C.; Ou, S.J.; Clouthier, S.G.; Patel, S.H.; Monville, F.; Korkaya, H.; Heath, A.; Dutcher, J.; Kleer, C.G.; et al. Breast Cancer Stem Cells Are Regulated by Mesenchymal Stem Cells through Cytokine Networks. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 614–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quante, M.; Tu, S.P.; Tomita, H.; Gonda, T.; Wang, S.S.W.; Takashi, S.; Baik, G.H.; Shibata, W.; DiPrete, B.; Betz, K.S.; et al. Bone Marrow-Derived Myofibroblasts Contribute to the Mesenchymal Stem Cell Niche and Promote Tumor Growth. Cancer Cell 2011, 19, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, T.L.; Cui, R.; Szaniszlo, P.; Resto, V.A.; Powell, D.W.; Pinchuk, I.V.; Watts, T.L.; Cui, R.; Szaniszlo, P.; Resto, V.A.; et al. PDGF-AA mediates mesenchymal stromal cell chemotaxis to the head and neck squamous cell carcinoma tumor microenvironment. J. Transl. Med. 2016, 14, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansy, B.A.; Dißmann, P.A.; Hemeda, H.; Bruderek, K.; Westerkamp, A.M.; Jagalski, V.; Schuler, P.; Kansy, K.; Lang, S.; Dumitru, C.A.; et al. The bidirectional tumor—Mesenchymal stromal cell interaction promotes the progression of head and neck cancer. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2014, 5, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-L.; Li, H.-Y.; Zhao, X.-P.; Jiao, J.-Y.; Tang, D.-X.; Yan, L.-J.; Wan, Q.; Pan, C.-B. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived CCN2 promotes the proliferation, migration and invasion of human tongue squamous cell carcinoma cells. Cancer Sci. 2017, 108, 897–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Feng, X.; Wang, B.; Wang, X.; Wang, C.; Yu, M.; Cao, G.; Wang, H. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells promote head and neck cancer progression through Periostin-mediated phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin. Cancer Sci. 2018, 109, 688–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Zhang, Z.; Han, Y.; Song, J.; Xu, X.; Jin, J.; Su, S.; Mu, D.; Liu, X.; Xu, S.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cells derived from normal gingival tissue inhibit the proliferation of oral cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Int. J. Oncol. 2016, 49, 2011–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Han, J.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, N.; Qu, N. New advances in the therapeutic strategy of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: A review of latest therapies and cutting-edge research. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Rev. Cancer 2025, 1880, 189230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, P.; Sekaran, S.; Ramasamy, P.; Ganapathy, D. Systematic analysis of chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and combination therapy in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (HNSCC) clinical trials: Focusing on overall survival and progression-free survival outcomes. Oral Oncol. Rep. 2024, 12, 100673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, R.L.; Blumenschein, G.J.; Fayette, J.; Guigay, J.; Colevas, A.D.; Licitra, L.; Harrington, K.; Kasper, S.; Vokes, E.E.; Even, C.; et al. Nivolumab for Recurrent Squamous-Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1856–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, R.L.; Blumenschein, G.; Fayette, J.; Guigay, J.; Colevas, A.D.; Licitra, L.; Harrington, K.J.; Kasper, S.; Vokes, E.E.; Even, C.; et al. Nivolumab vs investigator’s choice in recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: 2-year long-term survival update of CheckMate 141 with analyses by tumor PD-L1 expression. Oral Oncol. 2018, 81, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argiris, A.; Li, S.; Savvides, P.; Ohr, J.P.; Gilbert, J.; Levine, M.A.; Chakravarti, A.; Haigentz, M., Jr.; Saba, N.F.; Ikpeazu, C.V.; et al. Phase III Randomized Trial of Chemotherapy With or Without Bevacizumab in Patients With Recurrent or Metastatic Head and Neck Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 3266–3274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Tie, Y.; Alu, A.; Ma, X.; Shi, H.; Li, Q.; Tie, Y.; Alu, A.; Ma, X.; Shi, H. Targeted therapy for head and neck cancer: Signaling pathways and clinical studies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, C.; Barone, C.A.; Girolomoni, G.; Russi, E.G.; Merlano, M.C.; Ferrari, D.; Maiello, E. Management of Skin Toxicity Associated with Cetuximab Treatment in Combination with Chemotherapy or Radiotherapy. Oncologist 2011, 16, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruzzese, F.; Di Gennaro, E.; Avallone, A.; Pepe, S.; Arra, C.; Caraglia, M.; Tagliaferri, P.; Budillon, A. Synergistic Antitumor Activity of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Gefitinib and IFN-α in Head and Neck Cancer Cells In vitro and In vivo. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozec, A.; Sudaka, A.; Fischel, J.-L.; Brunstein, M.-C.; Etienne-Grimaldi, M.-C.; Milano, G.; Bozec, A.; Sudaka, A.; Fischel, J.-L.; Brunstein, M.-C.; et al. Combined effects of bevacizumab with erlotinib and irradiation: A preclinical study on a head and neck cancer orthotopic model. Br. J. Cancer 2008, 99, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.; Ren, Z.; Yang, X.; Yang, R.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Z.; Dai, Z.; Zhang, Y.; He, Y.; Zhang, C.; et al. Nerve growth factor (NGF)-TrkA axis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma triggers EMT and confers resistance to the EGFR inhibitor erlotinib. Cancer Lett. 2020, 472, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, G.D.; Wilson, T.G.; Hanna, A.; Dabjan, M.; Buelow, K.; Torma, J.; Marples, B.; Galoforo, S. Dacomitinib and gedatolisib in combination with fractionated radiation in head and neck cancer. Clin. Transl. Radiat. Oncol. 2021, 26, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Wang, Y.; Ji, H.; Sun, X.; Xie, S.; Chen, L.; Li, S.; Zeng, W.; Chen, R.; Tang, Q.; et al. Lenvatinib for effectively treating antiangiogenic drug-resistant nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Y.; Matsui, J.; Matsushima, T.; Obaishi, H.; Miyazaki, K.; Nakamura, K.; Tohyama, O.; Semba, T.; Yamaguchi, A.; Hoshi, S.S.; et al. Lenvatinib, an angiogenesis inhibitor targeting VEGFR/FGFR, shows broad antitumor activity in human tumor xenograft models associated with microvessel density and pericyte coverage. Vasc. Cell 2014, 6, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.-W.; Gridley, D.S.; Kim, P.D.; Hu, S.; Necochea-Campion, R.d.; Ferris, R.L.; Chen, C.-S.; Mirshahidi, S. Linifanib (ABT-869) enhances radiosensitivity of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells. Oral Oncol. 2013, 49, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.M.; SenthilKumar, G.; Hu, R.; Goldstein, S.; Ong, I.M.; Miller, M.C.; Brennan, S.R.; Kaushik, S.; Abel, L.; Nickel, K.P.; et al. Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptors as Targets for Radiosensitization in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinomas. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2020, 107, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Han, S.; Sun, X.; Xu, Y.; Feng, J.; Shang, J. Radiosensitizing effect of c-Met kinase inhibitor BPI-9016M in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cells in vitro and in vivo. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Muramatsu, T.; Inazawa, J. Suppression of MET Signaling Mediated by Pitavastatin and Capmatinib Inhibits Oral and Esophageal Cancer Cell Growth. Mol. Cancer Res. 2021, 19, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Fan, L.; Wang, P. MEK inhibition by trametinib overcomes chemoresistance in preclinical nasopharyngeal carcinoma models. Anti-Cancer Drugs 2021, 32, 978–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Affolter, A.; Muller, M.-F.; Sommer, K.; Stenzinger, A.; Zaoui, K.; Lorenz, K.; Wolf, T.; Sharma, S.; Wolf, J.; Perner, S.; et al. Targeting irradiation-induced mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in vitro and in an ex vivo model for human head and neck cancer. Head Neck 2016, 38, E2049–E2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, Y.; Wang, W.; Zheng, X.; Yang, L.; Wu, H.; Hu, Z.; Li, Y.; Yue, J.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, X.; et al. NVP-BSK805, an Inhibitor of JAK2 Kinase, Significantly Enhances the Radiosensitivity of Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma in vitro and in vivo. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2020, 14, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, F.; Lu, F.-T.; Qiu, M.-Z.; Zhou, T.; Ma, W.-J.; Luo, M.; Zeng, K.-M.; Luo, Q.-Y.; Pan, W.-T.; Zhang, L.; et al. Gemcitabine and APG-1252, a novel small molecule inhibitor of BCL-2/BCL-XL, display a synergistic antitumor effect in nasopharyngeal carcinoma through the JAK-2/STAT3/MCL-1 signaling pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, Q.; Yuan, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Z.; Li, Z.; Lai, Y.; Gao, J.; Shen, L.; et al. CDK4/6 inhibitor-SHR6390 exerts potent antitumor activity in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by inhibiting phosphorylated Rb and inducing G1 cell cycle arrest. J. Transl. Med. 2017, 15, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajamoorthi, A.; Shrivastava, S.; Steele, R.; Nerurkar, P.; Gonzalez, J.G.; Crawford, S.; Varvares, M.; Ray, R.B. Bitter Melon Reduces Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Growth by Targeting c-Met Signaling. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e78006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrie, M.; Brugge, J.S.; Mills, G.B.; Zervantonakis, I.K.; Labrie, M.; Brugge, J.S.; Mills, G.B.; Zervantonakis, I.K. Therapy resistance: Opportunities created by adaptive responses to targeted therapies in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2022, 22, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soragni, A.; Knudsen, E.S.; O’Connor, T.N.; Tognon, C.E.; Tyner, J.W.; Gini, B.; Kim, D.; Bivona, T.G.; Zang, X.; Witkiewicz, A.K.; et al. Acquired resistance in cancer: Towards targeted therapeutic strategies. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2025, 25, 613–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagogo-Jack, I.; Shaw, A.T.; Dagogo-Jack, I.; Shaw, A.T. Tumour heterogeneity and resistance to cancer therapies. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 15, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauss, C.; Stone, L.D.; Ghafouri, M.; Quan, D.; Johnson, J.; Fribley, A.M.; Amm, H.M.; Gauss, C.; Stone, L.D.; Ghafouri, M.; et al. Overcoming Resistance to Standard-of-Care Therapies for Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinomas. Cells 2024, 13, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meci, A.; Goyal, N.; Slonimsky, G.; Meci, A.; Goyal, N.; Slonimsky, G. Mechanisms of Resistance and Therapeutic Perspectives in Immunotherapy for Advanced Head and Neck Cancers. Cancers 2024, 16, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castilho, R.M.; Squarize, C.H.; Almeida, L.O.; Castilho, R.M.; Squarize, C.H.; Almeida, L.O. Epigenetic Modifications and Head and Neck Cancer: Implications for Tumor Progression and Resistance to Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Liu, L.; Mims, J.; Punska, E.C.; Williams, K.E.; Zhao, W.; Arcaro, K.F.; Tsang, A.W.; Zhou, X.; Furdui, C.M. Analysis of DNA methylation and gene expression in radiation-resistant head and neck tumors. Epigenetics 2015, 10, 545–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amable, L. Cisplatin resistance and opportunities for precision medicine. Pharmacol. Res. 2016, 106, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, M.; Ulibarri, J.; Liu, K.J.; Mao, P.; Duan, M.; Ulibarri, J.; Liu, K.J.; Mao, P. Role of Nucleotide Excision Repair in Cisplatin Resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuelei, M.; Jingwen, H.; Wei, D.; Hongyu, Z.; Jing, Z.; Changle, S.; Lei, L. ERCC1 plays an important role in predicting survival outcomes and treatment response for patients with HNSCC: A meta-analysis. Oral Oncol. 2015, 51, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.-D.; Huang, T.-J.; Peng, L.-X.; Yang, C.-F.; Liu, R.-Y.; Huang, H.-B.; Chu, Q.-Q.; Yang, H.-J.; Huang, J.-L.; Zhu, Z.-Y.; et al. Epstein-Barr Virus_Encoded LMP1 Upregulates MicroRNA-21 to Promote the Resistance of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Cells to Cisplatin-Induced Apoptosis by Suppressing PDCD4 and Fas-L. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e78355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, F.; Zhang, H.; Du, Y.; Tan, P. miR-23a promotes cisplatin chemoresistance and protects against cisplatin-induced apoptosis in tongue squamous cell carcinoma cells through Twist. Oncol. Rep. 2015, 33, 942–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, J.A.; Kumar, B.; Cordell, K.G.; Prince, M.E.; Tran, H.H.; Wolf, G.T.; Chepeha, D.B.; Teknos, T.N.; Wang, S.; Eisbruch, A.; et al. Targeting Apoptosis to Overcome Cisplatin Resistance: A Translational Study in Head and Neck Cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2007, 69, S106–S108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ow, T.J.; Fulcher, C.D.; Thomas, C.; Broin, P.Ó.; López, A.; Reyna, D.E.; Smith, R.V.; Sarta, C.; Prystowsky, M.B.; Schlecht, N.F.; et al. Optimal targeting of BCL-family proteins in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma requires inhibition of both BCL-xL and MCL-1. Oncotarget 2019, 10, 494–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilormini, M.; Malesys, C.; Armandy, E.; Manas, P.; Guy, J.-B.; Magné, N.; Rodriguez-Lafrasse, C.; Ardail, D.; Gilormini, M.; Malesys, C.; et al. Preferential targeting of cancer stem cells in the radiosensitizing effect of ABT-737 on HNSCC. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 16731–16744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, I.N.F.; Silva-Oliveira, R.J.d.; Silva, L.S.d.; Martinho, O.; Evangelista, A.F.; Lengert, A.v.H.; Leal, L.F.; Silva, V.A.O.; Santos, S.P.d.; Nascimento, F.C.; et al. Comprehensive Molecular Landscape of Cetuximab Resistance in Head and Neck Cancer Cell Lines. Cells 2022, 11, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khattri, A.; Sheikh, N.; Agrawal, N.; Kaushik, S.; Kochanny, S.; Ginat, D.; Lingen, M.W.; Blair, E.; Seiwert, T.Y.; Khattri, A.; et al. Switching anti-EGFR antibody re-sensitizes head and neck cancer patient following acquired resistance to cetuximab. Cancer Gene Ther. 2024, 31, 1477–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bossche, V.; Vignau, J.; Vigneron, E.; Rizzi, I.; Zaryouh, H.; Wouters, A.; Ambroise, J.; Van Laere, S.; Beyaert, S.; Helaers, R.; et al. PPARα-mediated lipid metabolism reprogramming supports anti-EGFR therapy resistance in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sur, S.; Steele, R.; Isbell, T.S.; Venkata, K.N.; Rateb, M.E.; Ray, R.B.; Sur, S.; Steele, R.; Isbell, T.S.; Venkata, K.N.; et al. Momordicine-I, a Bitter Melon Bioactive Metabolite, Displays Anti-Tumor Activity in Head and Neck Cancer Involving c-Met and Downstream Signaling. Cancers 2021, 13, 1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandyopadhyay, D.; Tran, E.T.; Patel, R.A.; Luetzen, M.A.; Cho, K.; Shriver, L.P.; Patti, G.J.; Varvares, M.A.; Ford, D.A.; McCommis, K.S.; et al. Momordicine-I suppresses head and neck cancer growth by modulating key metabolic pathways. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeckx, C.; Baay, M.; Wouters, A.; Specenier, P.; Vermorken, J.B.; Peeters, M.; Lardon, F. Anti-Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Therapy in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Focus on Potential Molecular Mechanisms of Drug Resistance. Oncologist 2013, 18, 850–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]