Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Mechanical memory in the cell-matrix interactions appears to play a significant role at various levels in the metastatic cascade in cancer.

- The effect of mechanical memory influences the effectiveness of therapeutic approaches in cancer.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- Knowledge of mechanical memory can lead to improved tumor therapy by combining inhibitors of the altered mechanical properties of the tumor matrix, such as increased stiffness, with established drugs that can better reach the site of action.

- Common mechanical memory mechanisms of different types of cancer point to a universal phenomenon and as such need to be assessed in a dynamic manner to precisely predict the individual malignant potency of tumors.

Abstract

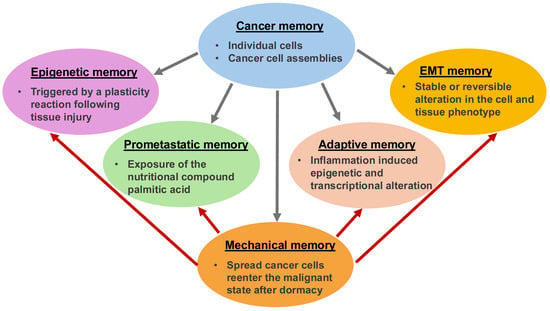

Besides genomic and proteomic analyses of bulk and individual cancer cells, cancer research focuses on the mechanical analysis of cancers, such as cancer cells. Throughout the oncogenic evolution of cancer, mechanical inputs are stored as epigenetic memory, which ensures versatile coding of malignant characteristics and a quicker response to external environmental influences in comparison to solely mutation-based clonal evolutionary mechanisms. Cancer’s mechanical memory is a proposed mechanism for how complex details such as metastatic phenotypes, treatment resistance, and the interaction of cancers with their environment could be stored at multiple levels. The mechanism appears to be similar to the formation of memories in the brain and immune system like epigenetic alterations in individual cells and scattered state changes in groups of cells. Carcinogenesis could therefore be the outcome of physiological multistage feedback mechanisms triggered by specific heritable oncogenic alterations, resulting in a tumor-specific disruption of the integration of the target site/tissue into the overall organism. This review highlights and discusses the impact of the ECM on cancer cells’ mechanical memory during their metastatic spread. Additionally, it demonstrates how the emergence of a mechanical memory of cancer can give rise to new degrees of individuality within the host organism, and a connection to the cancer entity is established by discussing a connection to the metastasis cascade. The aim is to identify common mechanical memory mechanisms of different types of cancer. Finally, it is emphasized that efforts to identify the malignant potency of tumors should go way beyond sequencing approaches and include a functional diagnosis of cancer physiology and a dynamic mechanical assessment of cancer cells.

1. Introduction to Mechanical Memory

The physical migration to and invasion of cancer cells of targeted tissue sides during cancer metastasis represents a clear sign of malignant cancer progression that often leads to cancer-related deaths. Cancer cell spreading has been extensively explored based on genetic [1,2], proteomic [3,4] and epigenetic cues [5,6,7,8,9]. However, the metastatic spread of cancer cells is still not fully understood. Thus, the current focus of epigenetic studies on cancer progression has been broadened to mechanical signals [9,10,11,12,13]. Cancer malignant progression compromises mechanical cues of the extracellular matrix (ECM) microenvironment, such as stiffness/softness and viscoelasticity, intercellular tension inside a solid tumor, contractility-driven stress evoked by tumor stromal cells [14], interstitial fluid pressure (IFP) [15], the direct interplay of cancer cells with endothelial cells or pericytes of the vascular system during their possible transmigration of the endothelial vessel lining [16,17], resistance toward blood flow forces, and the physical characteristics at the targeted tissue niche.

This review discusses and clarifies the significance of the mechanical signals to which cancer cells are exposed, as well as their responsiveness in each step in the metastatic cascade. It is also demonstrated how cancer cells can remember these mechanical stimuli. For example, stiffness-induced mechanical memory mechanisms are discussed, whereby the role of structural alterations in the cell’s cytoskeleton, the activity of transcription factors and epigenetic effects are highlighted. Moreover, the focus is placed on how mechanical memory affects cancer cells’ metastatic spread. The influence of mechanical memory on the various steps of metastasis has been proposed and discussed. The universal applicability of mechanical memory enabled by the ECM to various cancer cell types is debated. Finally, the influence of mechanical memory on future directions is also envisioned, with a special emphasis on biomechanical changes.

2. The Amount of Mechanical Memory Is Impacted by the Intensity and Length of the Mechanical Stress

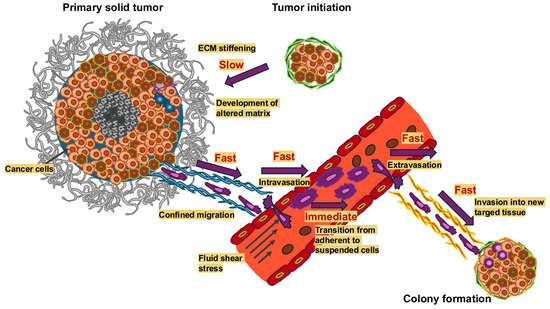

It has been established that cancer cells constantly sense and adjust to mechanical characteristics of the microenvironment, which impacts their functionality, such as through motility and invasiveness, as well as their metastatic capacity [18,19]. The timescales over which the mechanical signals change in the various steps of the metastasis cascade are depicted in Figure 1. In addition, the exposure time of cancer cells to these mechanical cues seems to also be a critical factor. Beyond that, there is limited knowledge about how cellular adjustments from past physical surroundings are preserved or how cells store mechanical memory on long (several days or weeks) or short (a few days) timescales.

Figure 1.

Mechanical alterations take place on vastly different timescales in the course of cancer metastasis. Dynamic alterations in the mechanical microenvironment throughout cancer metastasis arise with varying temporal scales. Important processes like ECM strengthening take a long time, from months to years, unlike fast processes like restricted migration and invasion into new targeted tissue, intravasation (usually 2 to 24 h) and almost fast processes, such as extravasation (typically 24 h to three days) and immediate processes like the transition from adhesion to suspension when cancer cells enter the circulatory system. The longer a mechanical signal lasts, the more probable it is that it serves as mechanical memory.

2.1. What Are the Timescales of Mechanical Memory?

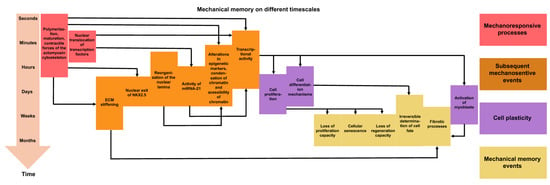

Current knowledge about mechanical memory can be summarized in two points [20]. First, the memory of retrograde stiffness is dose-dependent and grows with the priming time to the point where the effects begin to take on irreversibility. In many short-term mechanical priming events, the processes can be reversed, and the reversibility of different mechanical priming mechanisms has recently been extensively reviewed in [21]. The critical time-point prior to irreversibility probably relies heavily on the state of the cell such as its mechanosensitivity, differentiation capacity, and the cell cycle phase, as well as on the time-dependent signaling paths that become active when specific differentiation signals are received. There seems to be no systematic investigation yet into the extent to which mechanical memory relies on the magnitude of the stiffness mismatch, although this has been investigated on a theoretical basis [22]. It can be assumed that this phenomenon is nonlinear, as the mechanical stress on cells caused by the traction forces between cells and the extracellular matrix grows nonlinearly with the stiffness of the substrate [23]. Traction forces are defined as tangential forces exerted by cells either to the ECM or the underlying substrate [24]. The second point of convergence is that there are a number of effectors of mechanical memory whose activity varies depending on cell types and the nature of mechanical stress. The characteristic time constants relevant to mechanical memory are the period of the mechanical priming phase and the stability of proteins and epigenetic determinants, as well as the combined reaction time of the feedback circuits between the cytoskeleton and transcription (Figure 2). In current computer-based investigations, these factors on their own were all that was necessary for mechanical memory [25,26].

Figure 2.

Mechanical memory can manifest itself over very different periods of time. Overview of the processes that occur at the various phases of mechanical activation, mechanotransduction, and mechanical memory. The arrows point to the subsequent consequences. The different colors indicate the specific type of processes. The mechanoresponsive events that are directly triggered through mechanical stress are illustrated in red. The downstream mechanosensitive events are reversible under transient mechanical stress and are highlighted in orange. The cell plasticity events or instances of targeted phenotypic alterations are marked in purple. Mechanical memory events, which occur (in part) as a result of persistent mechanical stress, are shown in yellow.

2.2. Physical Priming Affects Mechanical Memory

The insight into mechanical memory lies in gaining an appreciation of how physical priming effects within a specific microenvironment will influence cellular function and destiny within a different, subsequent microenvironment [27,28,29]. In certain cases, when the amount of time spent in physical priming is somewhat restricted, the mechanical memory can be retained for a short period of time, such as 1 to 3 days, and it has no effect on the long-term behavior of the cells [30]. In contrary, the accumulated memory of this environment diminishes cellular plasticity when the duration of mechanical environment exposition exceeds a critical limit, leading to the reprogramming of cells into a condition with a sustained phenotype through the regulation of focal adhesion assembly and architecture [28,31,32]. Thereby, the long term mechanical memory keeper MicroRNA-21 has been identified [28]. On some occasions, this reprogrammed mode can be abnormal and exacerbate conditions like fibrosis [28,31,33], affect cell performance during cancer metastasis [34], or impair regenerative tissue processes [28,29,30]. Nonetheless, the mechanisms of mechanical memory are not yet fully comprehended, and it is crucial to explore how to perturb maladaptive mechanical memory for translational application purposes.

As the stimulation of mechanoreceptors, such as integrins, requires to be above a certain threshold [35], it seems to be likely that there also exists a threshold for mechanical memory stimulation. This would be necessary to avoid unnecessary information storage and to save only relevant changes. Thus, on short priming times the cells adapt temporarily to substrate stiffness, but mechanical signaling cannot increase reinforcement (transcriptional activity) sufficiently to generate mechanical memory. Consequently, there is no memory generated. Apart from exceeding a specific stiffness limit for generation of mechanical memory, the mechanical dosing plays a role as it has been previous demonstrated in human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs). Typically, many of the experimental investigations have centered on the influence of substrate stiffness and the impact of mechanotransduction on hMSCs, specifically how hMSCs perceive and assimilate mechanical signals from their rigid environment, which subsequently dictate their cellular fate [31,32,33]. For instance, hMSCs can memorize previous mechanical surroundings, which may impact long-term decision-making regarding cell fate or regenerative ability after transplantation [28,34]. It is assumed that cancer cells experience a similar change in their mechanical cues and memorize previous mechanical environments when they undertake the metastatic journey. This mechanical memory is featured by an irreversible nuclear homing of the co-transcription factor YAP and relies on the duration of hMSC cultivation on stiff substrates, which is referred to as mechanical dosing. The mechanical dosing may also play a role in cancer cells. In the past, the event of stress/strain stiffening has been described for cancer cells. The stiffening of cancer cells under stress has been delineated by a behavior in which the internal architecture of the cells, such as their actin cytoskeleton, becomes less flexible and stiffer under elevated mechanical stress [17,36,37,38]. Previously, it has still been interpretated as not fully relaxed cells that are mechanically stimulated several times. This strain stiffening enables these cells to both reshape themselves and squeeze through tight spaces to penetrate tissue, as well as generate force and adhere better to the ECM during invasion and metastatic spread. This strain stiffening process involves a complicated, nonlinear mechanical reaction in which the cell adjusts its stiffness depending on the strain to adapt to mechanical constraints. This stiffening is a kind of mechanoadaptation, which implies that the cell alters its mechanical characteristics to deal more effectively with the stresses and strains experienced in invasion, such as migration through constrained tissue and the ECM scaffold. Assuming these mechanical adjustments persist, they can be considered a form of mechanical memory. A brief cell cultivation period on stiff substrates (short-term mechanical dosage) leads to reversible mechanical memory, in which YAP can relocate from the cell nucleus to the cytoplasm with nominal modifications in gene expression. In contrast, prolongation of the mechanical dosing leads to irreversible mechanical memory, where YAP remains in the cell nucleus and induces significant alterations in gene expression [28,32,34,39,40]. It is widely accepted that YAP and some other transcription factors can modulate gene expression. However, it is common knowledge that epigenomics can likewise modulate gene expression, which points to its involvement in mechanical memory [41,42,43,44,45,46]. At intermediate priming times, the mechanical signaling increases reinforcement but leads to only temporary memory. The model predicts a continuous range of memory persistence times, from significantly shorter than priming time to longer than priming time, which relies on the time and stiffness of the priming phase. At long priming times, the reinforcement from mechanical signaling becomes strong enough to result in permanent memory in which the cell phenotype persists even if the substrate is switched back.

It has been discussed that chromatin remodeling, such as the architecture of chromatin, may serve as a mechanical memory keeper [29]. Chromatin rearrangement predominantly controls gene expression via epigenetic modifications involving acetylation, methylation, and phosphorylation at the amino-terminal ends of nucleosomal histones (see also Figure 1) [47,48,49,50]. The acetylation scene is super dynamic and is controlled by two types of enzymes, such as histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs). The acetylation of histones through HATs results in the expansion of chromatin, which facilitates gene expression [47,48,49,50]. As an alternative, the deacetylation of histones by HDACs leads to chromatin condensation and suppression of gene expression. HDACs and HAT1 have been demonstrated to fulfill tasks in reversible and irreversible remodeling of chromatin [29].

2.3. Mechanical Cues Evoked by Culture Conditions Impact the Response to Medication

Previous investigations have demonstrated that mechanical stimuli can impact the epigenomics of hMSCs [27,51,52,53,54,55]. For instance, it was revealed that in MSC-colonized scaffolds exposed to 10 percent tensile stretch, the condensation of chromatin was enhanced by about 80 percent in comparison to unstressed controls [51]. Moreover, the results indicated higher and sustained rates of condensation following multiple exposures of the scaffolds to stress, indicating that previous stress had affected the cell nucleus [27]. Similarly, it has been demonstrated that topology impacts epigenomics, as MSCs grown on 10 µm grooved polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) surfaces exhibited increased histone 3 acetylation levels and reduced nuclear HDAC activity when compared to cells grown on smooth surfaces [56]. Moreover, they showed that the adult fibroblasts were able to undergo EMT on these grooved substrates. Finally, it has been found that the expansion of MSCs on tissue culture plastic not only reduces secretory characteristics and multipotency, but also causes some localized genetic and epigenetic alterations, such as DNA methylation increasing over time [57]. Overall, these data imply that chromatin reorganization and the epigenetic map probably serve as key drivers in how hMSCs incorporate physical signals from their environment through time. Nevertheless, it is still uncertain whether these chromatin alterations can be reversed and what part integrated exposition to stiff microenvironments over time, such as mechanical dosing, can take in controlling these alterations. Therefore, the epigenomic and chromatin rearrangement that arises in expanding hMSCs hinges on the history of the cultivation and cumulative alterations in chromatin architecture over time result in a mechanical memory of the cell. Altogether, there seems to be a nonlinear coupling between mechanical signaling and transcriptional evolution that can explain the general features of mechanical memory. Nevertheless, further experimental studies are required to extend this model and include mechanistic details, this model may represent an important foundation for experimental studies and cell-based therapies that aim to engineer cell dynamics based on microenvironment mechanics.

The question arises as to how typical standard culture methods such as spheroids or feeder layers perform when modeling the various conditions of mechanical input. Spheroids constitute 3D cell clusters that are self-assembling and more closely resemble solid tissue compared to 2D tissue cultures. They enhance interaction between neighboring cells and between cells and the matrix, providing a physicochemical environment analogous to that found in living organisms. The spheroids retain their intrinsic phenotypic characteristics and promote the expression of stem cell markers. In addition, cytokines, chemokines, and angiogenic factors are secreted by spheroids, thereby increasing cell viability and proliferation [58]. An advancement is the possibility to include particles in spheroid cultures to govern mechanotransductional mechanisms inside the spheroid and increase viability and proliferation [59]. Modeling of the mechanical environment of solid tumors, incorporating the implications of cell–cell and cell-ECM interactions, is highly suitable for mechanical input modeling. Cells within spheroids are subjected to shear stress and compression, with mechanical characteristics, such as mechanical forces varying depending on cell type and size. Larger spheroids (>500 µm) generate metabolic gradients (hypoxia, dormancy, proliferation) that are reminiscent of those observed in tumors and are impacted through mechanical factors, which is another advantage of these models. An advantage of them is their resistance to drugs. In particular, their 3D structure and mechanical characteristics encourage drug resistance resembling that of solid tumors, which renders them useful for drug screening. A disadvantage is that they exhibit a diffusion gradient with increasing size of the spheroids and a deficiency of nutrients in the center of the spheroids [58]. Another limitation is that, although they represent a considerable advancement over 2D models, they simply do not possess the complexity and engineering framework of organoids, and visualizing their internal structure can be complicated. Feeder layer cultures consist of a layer of cells (the feeder layer) that serves as a substrate for the growth of other cells. Feeder layer models are of limited suitability for mechanical input modeling, as they primarily offer a 2D interface. Feeder layers transmit mechanical forces predominantly in a 2D plane. They can be coupled with other methodologies, such as 3D culture systems, to achieve a more advanced mechanical microenvironment. Feeder layers are somewhat limited, as they mainly model mechanical impacts in a 2D plane and may not completely reflect the intricate forces in 3D tissues that cells are exposed to in a real tissue microenvironment. Special culture systems are required to precisely regulate and accurately measure mechanical forces in 2D or 3D. In conclusion, spheroid and feeder layer methods provide distinct opportunities for applying mechanical influences, with spheroids being more suitable for modeling mechanical in vivo environments. Both are preferred as cell culture systems over simple 2D cell culture on plastic dishes. In this context, it can be cautiously said that standard monolayers on plastic are not very significant. The question arises as to which culture conditions (even xenografts, while inappropriate for large-scale trials) are more suitable than standard monolayer cultures for predicting the reaction to drugs in the context of drug screening. This question can only be answered in part, as there is currently insufficient literature on cancer drugs and mechanical effects, and further efforts are needed. Dynamic suspension cultures such as spinner cultures and rotary wall vessels exert mechanical forces by fluid flow and rotation, which can also enhance nutrient and oxygen delivery. Microfluidic devices enable accurate regulation of mechanical forces like fluid flow and shear stress and can be utilized to explore cell confinement and cancer progression. Specific culture or bioprinting techniques or lap-on-a-chip techniques can be used to regulate the mechanical stimulation [60] to create mechanical memory. Bioprinting is a type of technique that involves using hydrogels and other substances to build intricate 3D structures that permit accurate positioning of spheroids and the exertion of defined mechanical forces. Scaffolds can serve as materials that can be used to produce artificial tissue with controlled mechanical characteristics, enabling investigation into how mechanical forces impact cell performance. All these culture techniques may help to improve the in vitro high-throughput anti-cancer drug screening by also covering the aspect of mechanical cues. However, there is still a lot effort needed to develop a screening platform that is reliable. Considerable progress has been made in the field of mechanosensory and mechanotransduction research, leading to the identification of mechanical memory and its relevance to the malignant progression of tumors.

3. Mechanosensing, Mechanotransduction and Mechanical Memory at the ECM-Cell Interface

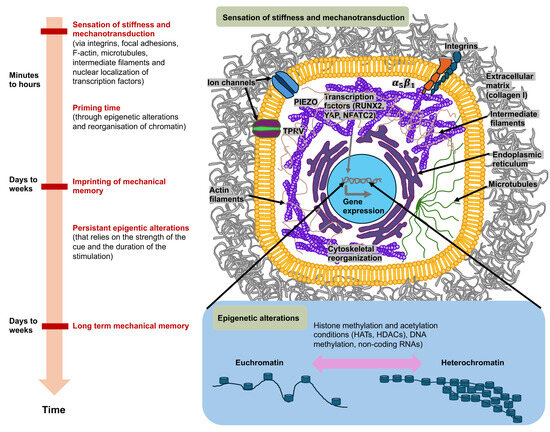

Cancer cells perceive mechanical signals that are generated either by direct forces, including tensile, compressive, and shear forces, or indirectly by alterations in the structure and mechanical features of the surrounding microenvironment, for instance, stiffness (elastic modulus) or the architecture of the ECM [5,36,61,62]. The sensing of mechanical forces involves mechanosensors, such as ion channels like PIEZO1 and TRPV4, integrins, that subsequently trigger the activation of molecular effectors in specific signaling routes [63] that can lead to modifications in gene expression and cell function [5,6,64,65]. This phenomenon is referred to as mechanotransduction [63]. For instance, these mechanical cues can facilitate a dynamic reorganization of the cell’s cytoskeleton, which can elevate either its stiffness or its deformability (softness), as it is reviewed in [36]. Through this reorganization of the cytoskeleton, it is transferred from a stiff or ordered state to an irregular or compliant network that can translocate from a cytoplasmic side to a perinuclear side during force exertion [66]. Thus, cells react to mechanical signals through alterations in their internal cytoskeleton and by triggering biophysical alterations to the ECM, comprising its composition, crosslinks, geometry, mechanical properties, and topology [17,67]. Their phenotypic adaptivity is important for the ability to survive and function under altered mechanical environments [15,68,69]. Intriguingly, cells not only perceive mechanical stimuli, but can also remember them after they are no more applied. This kind of long-term mechanotransduction [70] is referred to as “mechanical memory” and could have significant consequences for tissue development, differentiation, and disease progression, such as cancer metastasis, heterogeneity of the cancer and the responsiveness to therapeutic treatment (Figure 3).

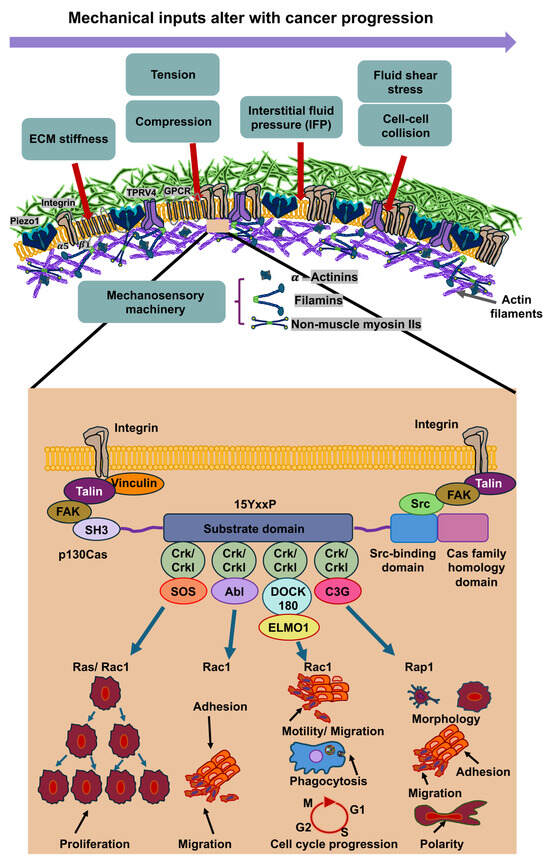

Figure 3.

Mechanosensory systems, mechanotransduction, and mechanical memory of cancer cells are characterized by ongoing epigenetic modifications in the most extensively studied context of matrix stiffness. Cancer cells perceive high matrix stiffness through integrin activation, which encourages cytoskeletal reorganization, which then facilitates the translocation of mechanotransducing transcription factors, runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2), and yes-associated protein (YAP), to the nucleus. These mechanosensory and mechanotransduction mechanisms arise in minutes to hours after encountering a rigid matrix. In the long term, mechanotransduction can result in epigenetic alterations, which include histone modifications by histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs), methylation of DNA (typically leads to gene silencing), and expression of non-coding RNAs, which initiate transcriptional gene silencing. When the level of mechanical stress and time of priming are severe enough (days to weeks), phenotypic adjustments are assumed to be preserved by the mechanical memory of cancer cells, which is enacted through sustained epigenetic alterations. Mechanical memory mechanisms appear to account for a key part of the metastasis pathway in that they directly couple the biophysical adaptations of cancer cells inherited from the primary cancer with the adaptations that propel the advancement of the disease to secondary cancer locations.

In cancer cells, the activation of PIEZO1 play a prominent role in the malignant progression of cancer. PIEZO1 constitutes a homotrimeric complex comprising a single cation-permeable pore [71,72]. Specifically, PIEZO1 in mice has a three-bladed, propeller-like architecture with three long intracellular arms that rotate together like a lever in reaction to mechanical force [73,74]. PIEZO1 is subject to reversible, flattening deformation upon exertion of force [75], which efficiently opens the pivotal pore for cation-selective permeation [75,76]. The PIEZO1 channel is mechanically driven through the actin cytoskeleton via a cadherin-ß-catenin-vinculin complex, indicating that a model considering forces originating from filaments can be combined with a model considering forces originating from lipids [77]. However, further research is required, particularly at the molecular and structural levels, to ascertain precisely how such forces are transmitted. Piezo channels also feature an inactivation gate, which is susceptible to membrane voltage and inhibits additional mechanical excitation until the channels are reset through outward permeation [78]. Apart from cancer cell mechanotransduction, there is also a judge impact of PIEZO1 signaling in immune cells, such as natural killer (NK) cells. The reactivity of NK cells is controlled by the stiffness of cancer cells. The killing efficacy of NK cells in 3D is compromised towards softened cancer cells, while it is increased towards stiffened cancer cells [79]. In T cells, it has been found that PIEZO1-driven mechanosensing of fluid shear stress enhances the activation of T cells [80]. These results indicate that the mechanophenotype of cancer cells is important for their survival, especially during the malignant progression of cancer.

Increased interactions between cancer cells and the ECM can therefore alter the mechanical response of cells through an interlinked hub of mechanochemical systems, including adhesion receptors like integrins, intracellular focal adhesions like talin-1, vinculin, focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and Crk-associated substrate (p130Cas or synonymously referred to as breast cancer anti-estrogen resistance 1 (BCAR1)), cytoskeletal networks such as actin, microtubules, and intermediate filaments, and molecular motors like myosin [17,81]. Talin-1 comprises at its N-terminus a FERM domain harboring four globular segments (F0 to F3), a disorganized connecting region, and a C-terminal rod consisting of 13 four- and five-helix bundles (R1 to R13) [82] which ends in a single α-helix that imparts homodimerization and therefore is designated as the dimerization domain [83].

The most extensively examined activation pathway of talin-1 relies on the small GTPase Rap1, which has an effector, Rap1-GTP-interacting adaptor molecule (RIAM), that connects with talin in R2-R3 in a direct, high affinity manner. There are additional RIAM binding sites in talin-1 that are located in R8 and R11 [82,84]. Rap1 can also bind directly to talin F0 [85,86]. Rap1/RIAM targets talin-1 to the plasma membrane [87,88] counteracts the autoinhibition of talin to encourage the engagement with integrin and actin. A minimum of 9 of the 13 rod domains harbor cryptic vinculin binding sites (VBSs) [89], which are uncovered through mechanical force, enabling vinculin engagement and strengthening of the adhesion. A head (F3) and R9 interaction autoinhibits talin-1, which needs to be liberated for actin and integrin attachment and its subsequent commitment to focal adhesions [90,91,92,93]. The interplay of talin-1 with the negatively charged phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate of the inner face of the plasma membrane also supports the activation of talin-1 and its interaction with the plasma membrane [94,95,96]. Talin-1 couples integrins to F-actin partly through the linkage of its N-terminal FERM domain to integrins’ cytoplasmic domains and partly through two locations of its C-terminal flexible rod domain that tethers to F-actin [97]. By sensing the extracellular stiffness, focal adhesion proteins unfold in specific regions/domains, such as talin-1 in its α helix bundles, named R1 to R13, that carry out reversible spring-like behavior (unfolding under tension and refolding when tension removed) [98]. Upon the unfolding of talin-1 vinculin binding is increased [99,100], which consequently rises the tension of talin-1 and strengthens focal adhesions that displays its mechanosensory functional role [83]. The latter finding indicates that talin-1 serves as a signaling hub for mechanotransduction. When vinculin is silenced in a migrating cell, the active localization of mitochondria at the cell front is disrupted, correlating with a reduction in migration velocity after leaving the matrix confinement, which implies a disturbance in cellular mechanical memory [101]. These mechanochemical systems trigger mechanotransduction routes in cancer via the activation of ERK signaling, rearrangement of the cytoskeleton, Rho-GTPase-driven cellular contractility, and cluster formation of integrins [67]. Consequently, the dynamic interaction of cancer cells and their ECM surroundings can impact the shape of the tissue. For example, aberrations in cell-to-cell and cell-to-ECM adhesion, as well as in cytoskeletal reorganization, cause the cancer cell to adopt an invasive shape that can penetrate the ECM, setting off the cascade of metastasis [102]. It has been shown that elevated ECM stiffness can upregulate lamellipodin expression [103]. This is conveyed through an integrin-dependent FAK-Cas-Rac signaling route and assists the stiffness-driven induction of lamellipodin. In this process, FAK and p130Cas transfer the stiffness of the surrounding matrix into internal stiffness of cells [104], which represents a potential mechanism for storing mechanical memories. The protrusion of lamellipodia and filopodia on the plasma membrane is decisive for different mechanisms, such as the migration of individual, mesenchymal or cancer cells [105]. The actin-binding protein lamellipodin is hypothesized to have a pivotal function in lamellipodium protrusion by transporting Ena/VASP proteins to the trailing plus ends of growing actin filaments and engaging with the WAVE regulatory complex, which activates the Arp2/3 complex, at the anterior margin. By counteracting abundant, disorganized retraction and membrane wave formation (ruffling), lamellipodin improves protrusion generation and the development of nascent adhesions [106]. Mechanistically, overexpression of lamellipodin elevated stiffness-induced expression of cell cycle protein D1 [107], while knockdown of lamellipodin diminished it, and triggered entry into the S phase and cell proliferation, pointing to a mechanosensitive cell cycle and subsequently triggering intracellular stiffness. The function of p130Cas as a molecular switch seems to be differently compared to talin-1. First of all, p130Cas has a role as an adaptor protein that acts before talin-1 comes into play at focal adhesions. The substrate p130Cas of the Src family kinase (SFK) has been seen to be phosphorylated and coupled with its Crk/CrkL effectors in clusters that serve as precursors for focal adhesions [108,109]. p130Cas is amongst the primary substrates for integrin-stimulated tyrosine phosphorylation [110,111,112]. The initial phospho-p130Cas clusters comprise integrin β1 that has an inactive, bent, closed state. On the molecular scale, p130Cas harbors an N-terminal SH3 domain, a four-helix bundle, and a C-terminal FAT domain, which are physically spaced apart from one another through unstructured regions and an SFK-SH3/SH2 binding site. The SH3 and FAT domains of p130Cas ensure its localization at focal adhesions [113,114], which can tether other focal adhesion proteins, such as vinculin, FAK, and paxillin as demonstrated in vitro assays [115,116,117]. In a subsequent step, the amount of phospho-p130Cas and total p130Cas is reduced due to the activation of integrin β1 key focal adhesion proteins, including vinculin, talin, kindlin, and paxillin, are enlisted. The formation of p130Cas clusters involves p130Cas, Crk/CrkL, SFKs, and Rac1, whereas vinculin is not necessary. Rac1 ensures positive coupling to p130Cas via reactive oxygen that is compensated by negative ubiquitin-proteasome system feedback. These findings suggest a two-stage model for focal adhesion formation, wherein clusters of phospho-p130Cas, effectors, and inactive integrin β1 propagate via positive feedback before activating integrins and enlisting key focal adhesion proteins. p130Cas and SFKs activate one another, with p130Cas tethering to SFKs and activating them, and SFKs phosphorylating p130Cas at up to 15 repeated YxxP motifs in the substrate domain (SD) sandwiched between the SH3 domain and the quadruple helix bundle [110,118]. The p130Cas SD undergoes fast phosphorylation upon cell adhesion [119,120,121]. The phosphorylation of p130Cas in its SD domain is stretch-dependent [108]. Thereby, p130Cas is able to convert force into a biochemical cue via the extension of the SD domain that leads to a priming to phosphorylation. This mechanical mechanism appears to be of a general nature in controlling intracellular signal transduction events. Phosphorylated pYxxP motifs of p130Cas can attach to specific SH2 domain proteins, such as the paralogs Crk and CrkL. Crk/CrkL, meanwhile, are able to attach to and stimulate several proteins, such as the guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) Rac1 DOCK180 [110,122,123,124,125,126]. After DOCK180 driven activation of Rac1, actin polymerization and lamellipodial protrusion is encouraged by Rac-1 via the WAVE/Arp2/3 complex, and triggers the formation of focal adhesion complexes according to undisclosed principles [127,128,129]. The role of mechanical signals from the TME in terms of their influence on the mechanical memory of cancer cells is discussed below.

4. Role of Microenvironmental Mechanical Cues on Mechanical Memory of Various Cancer Cell Types

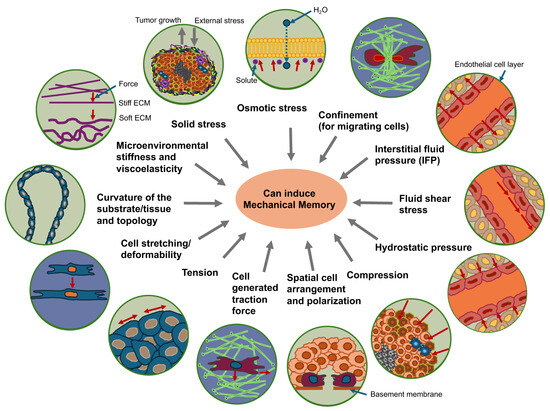

The most important question is what kind of mechanical signals can trigger mechanical memory in cancer cells that impacts their functional performance. It has been proven multiple times that the mechanical stiffness of the surrounding matrix can trigger a process of mechanical memory in cells (Figure 4). In addition to matrix stiffness of cancer cell surroundings, mechanical memory can be induced by cellular confinement affecting cancer cell migration, compressive stress that can lead via direct mechanotransduction to stretching/deformation of cells, cytoskeletal remodeling, altered gene expression, proliferation, migration/invasion or other effects via autocrine and paracrine signaling [130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137], fluid shear stress for cancer cells within the blood vessels, interstitial fluid pressure (IFP), hydrostatic pressure, and solid stress due to tumor growth and the reaction of tumor host tissue toward growth-dependent tumor extension (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Mechanical cues can trigger the mechanical memory function in cancer cells. Environmental stiffness and viscoelasticity, curvature and topology of the substrate, solid stress, osmotic stress, confinement of matrix migrating cells, cell stretching/deformability, cell generated traction forces, spatial arrangement and polarization, tension, fluid shear stress, hydrostatic pressure, interstitial fluid pressure (IFP) and compression can all trigger the induction of mechanical memory in cancer cells.

The localization of mechanosensitive ion channels on the cell surface often enables them to be the first molecules to perceive exterior physical signals and initiate intracellular biochemical cascades in a mechanism referred to as mechanotransduction [138,139,140]. Mechanosensitive ion channels ease the influx of Ca2+ into cells by a mechanism referred to as channel gating, enabling the perception of intricate physical signals and alterations inside the microenvironment. This process necessitates a specific threshold tension of the membrane to trigger a conformational switch from the closed to the open condition. The gating process may also rely on transmembrane voltage that is controlled through ion channels [141,142]. Mechanosensitive gating mechanisms can be roughly divided into two types. The first is direct mechanosensory perception, which is governed by physical modifications in the cell membrane, and the second is indirect mechanosensory perception, which is governed by intracellular signaling processes [138,139,143].

Compressive forces inside the primary tumor, fluid shear stress inside the blood vessels, and other mechanical cues that trigger local alterations in cell membrane curvature, composition, and tension can directly open mechanosensitive ion channels like Piezo1/2, Transient Receptor Potential Cation Channel Subfamily C Member 1 (TRPC1), and Transient Receptor Potential Cation Channel Subfamily V Member 4 (TRPV4) [143]. As an alternative, mechanosensitive molecules on the plasma membrane can indirectly induce the activation of mechanosensitive ion channels by a multi-step process that requires participation of a number of intermediate signaling molecules. This mechanism is usually based on the capacity of G protein-coupled receptors to sense alterations in the extracellular environment and induce a conformational switch in mechanosensitive ion channels like the transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily M member 7 (TRPM7) and TRPV4 [143]. Self-generated forces resulting from actomyosin contractility can also cause the activation of mechanosensitive ion channels within migrating cells [144]. For instance, tension in actin cytoskeletal scaffolds and increased signal transmission via integrins in cell-matrix interactions and cadherins in cell–cell interactions can indirectly impact the regulation of mechanosensitive ion channels [143]. In addition, the viscoelasticity of the microenvironment, microenvironmental matrix curvature and matrix topology can trigger mechanical memory as well as cell deformation via cell-stretching. Cell tension, cell generated traction force and the spatial arrangement and polarization of cells can all contribute to mechanical memory (Figure 4).

Surface curvature and matrix stiffness are two distinct concepts, though they can be related. Surface curvature refers to the physical shape of the matrix surface, while matrix stiffness is a material property that describes its resistance to deformation. For example, a cell on a stiff matrix might develop a more curved or smooth surface, while a cell on a soft matrix might develop a wrinkled surface. Stiffness can influence curvature: The stiffness of the matrix can influence the curvature of structures within or on it. For example, a cell’s nucleus might have a smooth, curved surface when on a stiff matrix but a wrinkled surface on a soft one. Surface curvature is directly related to matrix surface tension through the pressure jump across an interface, as described by the Young-Laplace equation, which connects surface tension γ and curvature κ to the pressure jump ΔP across a spherical interface: ΔP = 2γ/R, where R is the radius of curvature. The curvature determines the magnitude of the surface tension force, with more curved surfaces exhibiting higher stress.

How do these physical parameters influence the interfacial tension between the cell collective and matrix scaffold? Surface curvature affects interfacial tension by stretching tissue on convex surfaces and contracting it on concave surfaces, which can modify local cell density and trigger tissue movements. The surface tension of the matrix, which functions as a stretched elastic membrane, generates pressure that can propel the collective migration of cells [145]. These forces are coordinated through cell–cell and cell-matrix interactions to jointly control the shape, flow, and growth of the tissue. How can the surface curvature affect the interfacial tension? Firstly, the surface curvature impacts cell density. For instance, concave areas of the matrix decrease the surface area, resulting in an augmentation of cell density and crowding [146]. By contrast, convex areas enlarge the surface area, thereby reducing cell density and spreading the tissue. Secondly, surface curvature encourages pressure-based movements. In fact, the development of a meniscus, which is a curved interface between tissue and matrix, can generate hydrostatic pressure in the tissue. In conjunction with a mechanically induced reduction in friction at the interface between the cell and the matrix, this pressure is capable of serving as a driving force for collective cell migration [146]. Thirdly, surface tension links forces to cellular functions, with the curvature forming a physical boundary that connects forces to cellular processes including growth, cell shape, and the creation of cell patterns [147]. How can the matrix surface tension affect interfacial tension? Firstly, the matrix surface tension functions as an elastic membrane. Surface tension causes the tissue surface to function like a stretched elastic membrane, thereby keeping the total surface area of the tissue to a minimum. Secondly, the matrix surface tension establishes pressure gradients. For example, a depression in the tissue surface caused from a meniscus enhances the pressure in that area. Thirdly, it encourages collective movement, as the interaction of cell–cell forces such as contractility and cell-matrix adhesion can be conceptualized as interfacial tension. This joint force is a key contributor to collective cell movement and the flow of tissue. This implies that both the curvature and surface tension of the matrix are crucial physical characteristics that determine the performance of a collection of cells. They cooperate to govern the global shape and dynamics of the tissue, and impact processes such as fusion of tissues, spreading, and their development.

4.1. Impact of Mechanical Forces on Mechanical Memory of Cancer Cells

Mechanical forces, which can be extrinsic and/or intrinsic, challenge primary solid cancers over a wide spectrum of biological sizes and various different timescales. These timescales span from fast molecular-level processes that are implicated in perception and transmission to more slowly occurring and large-scale processes, such as clonal selection, epigenetic modifications, cancer cell invasion, metastasis, and immunological defense [148]. Forces acting outside a cell originate in the ambient surrounding tissue and exert pressure on the cancer cell. Cells produce their own forces, which are referred to as intrinsic forces and are also known as autotonic forces, that affect the structures in their vicinity. These forces differ from the inherent mechanical characteristics of a cell or tissue, such as the stiffness of the ECM, as these characteristics influence how the tissue is deformed in reaction to a specific mechanical force [149,150,151,152,153,154]. In general, the mechanical characteristics of a cell or tissue are inherent and robust. Typically, it takes minutes, hours, days, or weeks for them to change, and they can be easily manipulated experimentally, for example, by altering the biochemical crosslinking of the ECM. While the fibronectin-crosslinking can elevate the stiffness of the ECM [10], the enzymatic breakdown of the ECM scaffold by matrix-metalloproteinases, such as MMP-14 or collagenase III can reduce the stiffness by local softening surrounding migrating cells [155]. Nevertheless, fibronectin crosslinking can also lead to an acceleration of stress relaxation irrespective of the decrease in stiffness [156]. In contrast, mechanical forces take effect over very short periods of time, sometimes only a few pico- or milliseconds [157] at the single bond level. Moreover, the binding and release of molecules or the folding of biomolecules also takes place within this time frame. The stress relaxation time of a collagen I matrix, such as within the tumor microenvironment (TME), varies from seconds to hundreds of seconds, based on the specific architecture of the matrix, involving fibril sliding (0.3 to 1 s), interfibril interactions (90 s), and the occurrence of a proteoglycan matrix (200 s), which represents the collective nature of a whole network [158]. In general, there is a tendency for relaxation time to rise with the degree of structural organization, from individual molecules (nanoseconds) to fibrils (100 s) to whole tissues (minutes). In addition, the forces to which a cell or tissue is locally exposed can quickly fluctuate in direction or intensity, for example in the course of the migration of cancer cells across a matrix scaffold [159,160]. Investigations into force reactions are frequently more challenging to conduct and evaluate [161,162,163]. At the tissue scale, this can be extremely intricate, since mechanical forces develop over time and spatial scale as a tissue expands or shrinks.

How does a variation in matrix relaxation time impact the spread of cancer? The degradability of collagen gel leads to significant alterations in stress relaxation following collagenase exposure. In addition, the relaxation time until half the maximum force is attained proves to be a potent predictor of cell spreading, emphasizing the importance of stress relaxation as a key mechanosensory cue in degradable matrices [156]. MMP activity instantly causes mechanical alterations in the ECM, which are then sensed by cells. The cells reacted to these alterations in relaxation by changing how they spread and their focal adhesions. In 3D systems, degradability also refers to the temporal progression of microenvironmental space generated by cellular MMPs, which facilitates alterations in cell shape, growth, and motility. As a result, cells in degradable scaffolds often show improved spreading in comparison to non-degradable scaffolds owing to the physical constraint provided by non-degradable matrices [164].

Mechanical stresses are categorized based on the deformation they induce and can include compressive, tensile, shear, bending, or torsional stresses. Compressive stresses have the tendency to compact the material, while tensile stresses have the tendency to elongate (stretch) the material. Shear stresses cause shearing and happen when a tangential force is exerted parallel to the surface of an object, such as cells or tissues. In contrary, bending and torsional stresses result in curvature or distortion of the cells or tissue. Mechanical stresses are relevant in biological systems and develop jointly, as local tensile stresses are counterbalanced by neighboring compressive stresses inside a cell [165] or in a tissue [166]. Continuous dynamic compressive stresses are part of natural physiology and normal healthy tissue growth [167,168,169,170].

Within the TME, both cancer cells and host cells are exhibiting abnormal physical tissue properties, among them modified tissue structure, elevated stiffness, increased IFP, and solid stresses [161] (Figure 4). Under the straightforward analogy of a spring following Hooke’s law σ = E·ε, tumor growth and pressure on the surrounding TME with elastic modulus lead to deformation and a stress [171]. As a result, the host tissue yields an equal and opposite stress , that is defined in terms of externally imposed solid stress ( = ). This externally imposed stress, together with the growth-induced stress (), caused by mechanical reciprocal actions within the primary solid tumor, comprises the total solid stress transferred within the tumor [171].

The solid stresses are characterized by the mechanical forces transferred by the solid components of the tissue [161,162,172] and are completely different from the forces generated or transferred by fluids. Hydrostatic fluid pressure only shapes structures that expel water, like cell membranes (Figure 4). Cells are equipped with water channels that compensate for hydrostatic pressure over the membranes, so that the duration of the increased external pressure level results from the dynamics of the pressure increase and the relaxation rate achieved by the water channels. Nevertheless, relative to hydrostatic pressure, the implications of fluid flow have been more extensively investigated. Flowing fluids have been demonstrated to apply shear stress to the mechanosensors of endothelial and cancer cells, thereby influencing vascular viability and the metastasis of cancer [173,174]. In addition, solid stress, but not isotropic fluid pressure, can compact leaking blood and lymph vessels [175,176,177]. Cells moving within the crowded and frequently desmoplastic TME penetrate between cells by deforming themselves and through the structurally organized matrix [178,179]. In this process of restricted migration the cancer cells are also subjected to elevated compressive stresses, comparable to those imposed through increased solid-state stresses [180]. Nonetheless, these forces arise from movements caused by cells instead of external influences. There are, however, some biological events that are related to solid stress and restricted migration, such as epigenetic changes leading to reduced cell activity and dormancy or cell cycle arrest [181,182]. In addition, both confinement [183,184] and solid stress [161,172] have been widely reported in investigations where cells were entrapped in hydrogels that are either completely or partially non-degradable. In these types of models, cell movement is constrained because of the dense, porous matrix and cell compaction, preventing them from completely metabolizing or dissolving it [185]. When these cells multiply, they have to increase their volume, which causes them to press on the matrix, which results in the build-up of solid stresses [186].

4.2. Impact of the ECM Mechanics on Cancer Cell Mechanical Properties and Mechanical Memory

Similar to other cell types, cancer cells possess the capacity to adjust their (mechanical) properties to their mechanical environment, such as the stiffness, viscoelasticity and confinement of the nearby tissue like the ECM. Although stiffness has been selected as a mechanical characteristic in many cancer studies, it is not a good choice because stiffness is not constant in viscoelastic materials. Stiffness is time-dependent and impacted by strain-rate, materials history and temperature. For instance, the dissipation of energy due to structural alterations in a matrix is accountable for matrix softening. Conversely, the accumulation of residual stress in the matrix resulting from mutual interactions with cells leads to stiffening of the matrix. Both the migrating cell collectives and the ECM exhibit viscoelastic properties. The mechanical coupling of both systems and the interrelationship between their mechanical stores are interesting aspects to discuss. The mechanical coupling of migrating cell collectives and the viscoelastic ECM entails a dynamic, reciprocal transfer of force and deformation, in which cells restructure the matrix by exerting active forces like contractile forces (force transmission) that cause localized matrix restructuring. In turn, the matrix provides mechanical feedback. The alterations in the characteristics of the ECM, such as stiffness and topology, caused by cells function as mechanical signals that affect the cells and govern their direction of migration, velocity, and collective performance. There are also long-range effects. This coupled restructuring allows forces to be transmitted over long ranges across the matrix, thereby coordinating the behavior of cells that are far apart.

Due to their viscoelastic characteristics, i.e., their time-dependent mechanical response, which relies on the magnitude of the exerted force, both systems exhibit mechanical memory. Due to their elastic component, both the cells and the ECM react elastically when force is exerted and withstand sudden deformation. Hence, the cells and the ECM remember former forces by exhibiting elastic resistance to sudden alterations, but due to their viscous component, they tend to forget these forces over time because of viscous flow, which causes stress relaxation under constant strain and creep behavior under constant stress. This time-dependent response implies that they possess a memory of past mechanical stresses. The elastic component of the reaction mirrors recent forces, whereas the viscous component stands for history over longer periods of time. This interrelationship between their mechanical memories enables the transmission of long-range forces and the control of collective cell behavior via matrix restructuring. How are the mechanical memories of cells and the ECM connected? The interaction between the active mechanical memory of the cell collective and the passive viscoelastic memory of the ECM determines how forces are conveyed and how the whole system reacts to mechanical loads over time.

Is the matrix a stiffening/softening oscillator? The terminology “stiffening/softening oscillator” can be utilized to refer to a phenomenon in both cell mechanics and matrix mechanics. In cell-matrix interactions, it can characterize a process in which a cell-induced matrix initially softens and subsequently stiffens over time as a result of a cycle of matrix breakdown and reconstruction. In the early phases of interaction, there is an initial softening as cells can secrete enzymes that breakdown and thereby soften the ECM. Over time, progressive stiffening occurs, allowing the cells to reconstitute the matrix by deposition of increased collagen and other molecules. This can cause a significantly stiffer matrix, especially in the vicinity of the cells, as the fibers are more tightly packed and crosslinked. This whole cycle can be impacted through the mechanical tension on the matrix. A number of research findings indicate that synchronized mechanical oscillations between adjacent cells and the matrix may be a pivotal mechanism underlying how cells perceive their environment and uphold a tension set point [187]. In developing tissues, cells adjust the mechanical characteristics of their ECM in the presence of changing external loads to keep up a stress set point, but the mechanism involved remains unclear. It has been found that the set point represents a balance between cell-independent stress relaxation within the matrix and non-muscular myosin II-induced contraction of the cell. The matrix-dependent and cell-dependent phases display an oscillating tension component. Relaxation and renewed tension induce synchronization of mechanical oscillations in adjacent cells. It can be assumed that mechanical oscillation at the interface between the cell and the matrix is a core mechanism for the capacity of embryonic fibroblasts to perceive their mechanical surroundings, particularly the viscoelastic state of the relaxed tendon. This synchronized oscillating tension, engaging forces generated by the cells as well as external strain, assists the cells in sensing and reacting to tissue characteristics by forming a feedback circuit between the cells and the ECM [188]. The interaction of the pointed ends of extracellular collagen fibrils with the plasma membrane of fibroblasts to produce robust interfacial structures referred to as fibripositors occurs early in the development of mechanically stable tissue [188]. It can be assumed that a similar mechanism occurs in the TME with CAFs.

When cancer cells are subjected to a certain mechanical surrounding, they can alter their morphology, adhesion, and even gene expression to accommodate themselves more effectively. This adjustment can be maintained when the cells are transferred to a completely altered mechanical setting, which proves the existence of mechanical memory. An effective mechanism of mechanical memory is predicated on alterations in chromatin availability, which may be affected by mechanical forces and remain even when the forces are eliminated [189]. Activating and nuclear targeting of mechanosensitive proteins like Yes-associated protein/transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding motif (YAP/TAZ) [39], which can induce the expression of genes related to survival and migratory processes, provides another mechanism. Mechanical priming, in complementation to the retention of nuclear YAP, results in increased levels of microRNA-21, which remain after being grafted onto soft substrates, thereby keeping the mechanical memory [28]. It is supposed that mechanical memory has a major impact on cancer and its malignant progression. Hence, it can be postulated that mechanical memory is, in many ways, an important driving mechanism for the progression of cancer and may compromise cancer treatments. During cancer metastasis, cancer cells can “store and retrieve” the mechanical characteristics of the microenvironment of the primary tumor, for instance increased stiffness, enabling them to better withstand the stresses of metastasis and settle in remote organs (Table 1). In the case of resistance to medication, modifications in cell stiffness and other mechanical characteristics can influence the reciprocal reaction of cancer cells with medications and treatments, and possibly cause them to become resistant. Regarding the heterogeneity of cancer, mechanical memory may add to the multiplicity of cancer cells inside a tumor, increasing the difficulty of attacking all cancer cells in a single therapeutic approach.

Table 1.

Brief overview on selected important findings in mechanical memory identification in various (cancer) cell types.

Research findings indicate that mechanical memory is involved in the metastatic progression, whereby cells preserve adaptations that facilitate their survival and spreading to new sites. For instance, stiffness in breast cancer causes bone metastasis through the preservation of mechanical shaping [190]. Fibrotic matrix stiffness encourages pronounced metastatic phenotypes in cancer cells, which are retained after transfer to softer microenvironments like the bone marrow (Table 1). The sustenance of mechanical shaping is controlled by the Runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2), which belongs to the family of osteogenic transcription factors and is characterized as a key player in bone metastasis. As a mitotic marker, it maintains the accessibility of chromatin at target sites.

4.3. Impact of ECM-Supported Mechanical Memory on Cancer Treatment Evolves over the Course of the Disease

There is no doubt that mechanical memory can have an impact on cancer treatment and therefore probably holds enormous therapeutic potential that is only just beginning to be explored. Therefore, a deeper comprehension of mechanical memory mechanisms could provide new therapeutic approaches to combat cancer cells in a targeted and efficient manner by interrupting or modifying these memory circuits or even avoiding the development of mechanical memory. As mechanical signals change during the malignant progression of cancer, their influence on mechanical memory can change. Consequently, the impact of mechanical memory seems to be dependent on the metastatic step and cancer progression (Figure 5). In Figure 5, the mechanical inputs on cancer cells can be altered during the progression of cancer, such as an increase in ECM stiffness, cellular tension, cell and tissue compression, elevation in IFP, rise in cell–cell collisions during cancer expansion and elevation in fluid shear stress due to compressed cancer vessels for circulating tumor cells (CTCs).

Figure 5.

Mechanical inputs into cancer cells are s subject of change during the malignant progression of cancer. After mechanosensing of these mechanical cues through mechanoreceptors like integrins, ion channels (Piezo1 and TRPV4) and G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), such as GPR68. GPR68 (also synonymously referred to as OGR1) represents a G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) that functions as a coincidence sensor for both extracellular acid concentration and mechanical stress, coordinating these cues to modulate cellular response, notably within the TME. When the mechanosensing process has been started via signaling through mechanoreceptors, the mechanosensory molecules underneath the plasma membrane of cancer cells, comprising α-actinin, vinculin, talin, filamins and non-muscle myosin IIs, are mechanically altered. The inset illustrates how p130Cas interacts with varies molecules to perform different functions.

The alteration in mechanical inputs comes into play during the malignant progression of cancers, such as in cancer metastasis. Therefore, in the metastatic cascade, cancer cells experience various different mechanical cues over time and at the specific steps of the metastatic cascade that contribute finally to successful metastases formation as it is outlined below.

5. Potential Involvement of Mechanical Memory at the Different Steps of the Metastatic Cascade

The metastatic cascade comprises successive steps that contribute to the spread of cancer, commencing with the transformative process of a primary cancer into an invasive tissue-invading phenotype. This ultimately results in malignant cells passing into blood or lymph vessels via transendothelial migration, a process known as intravasation of cancer cell [197]. The possible impact of mechanical memory is envisioned at each step of the metastatic cascade (see Figure 6). The metastasis cascade begins with the spread of specific cancer cells from the primary tumor, which can be induced by a changed mechanical environment such as stiffness and viscoelasticity. It is hypothesized that the migration from the primary solid tumor, intravasation, extravasation, dormancy, and metastatic colonization of cancer cells are influenced by the preceding mechanical encounters of cancer cells in the primary TME. This not only means that cancer cells perceive and respond to mechanical cues, but also that they preserve the biophysical adaptations imposed on them by these physical stresses after migrating to a new environment. In the following the impact of mechanical cues including mechanical memory is presented for the sequential steps of cancer metastasis.

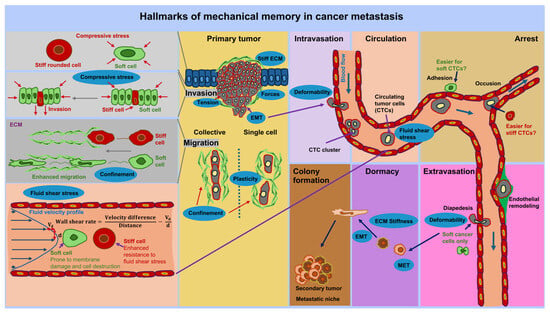

Figure 6.

The effect of mechanical memory at each step of the metastasis cascade is illustrated. The metastatic cascade starts at the primary solid tumor at which cancer cells can either spread as individual cells or a collection of cells out of the tumor’s boundary into the tumor microenvironment (TME). The migrating and invading cancer cells reach vessels, such as blood vessels, in which they transmigrate (intravasation). In the vascular system, they become circulatory tumor cells (CTCs) that are exposed to mechanical stresses, such as fluid shear stress. Within the blood vessels CTCs can aggregate and adhere to the endothelial lining of the vessels. Endothelial cells can be remodeled due to external cues and possible through CTCs. There may also be individual dormant CTCs that remain in a dormant state, adhering to endothelial cells. Thereby, single or aggregated CTCs persist in a rather dormant state. At same time, some CTCs can transmigrate through the endothelium and the vessel walls into a targeted tissue site, which is referred to as extravasation step. At targeted tissue site these cancer cells can become dormant or migrate directly to their targeted site where they can transit form the mesenchymal to the epithelial state. These cancer cells proliferate and colonize the targeted site to form secondary tumors, which is referred to as metastasis. Mechanical memory can play a role throughout the entire metastasis cascade, for example in the form of stiffness, forces, and confinement. The hallmarks of mechanical memory are marked as blue ovals. Mechanical signals at the different steps of metastasis influence the characteristics of cancer cells, such as cell shape, and their behavior. Mechanical signals can become mechanical memory after prolonged exposure and hence foster the progression of cancer metastasis.

5.1. Mechanical Conditions at the Primary Tumor

Solid malignant cancers display enhanced stiffness compared to healthy tissue or even benign tumors, such as those found in breast, pancreatic, liver, and prostate cancer [198,199,200,201] (see Table 2). It is noteworthy that the stiffness of cancers differs according to tissue type, depending on the stiffness of the normal surrounding tissue, varying between 1 kPa in the brain and 70 kPa in the bile ducts [161]. Compressive stress in kPa indicates how much force a material can withstand on a given surface area before it deforms or is damaged. A higher kPa value means that the material is stiffer and more resistant to pressure. A material with a compressive stress of 70 kPa is therefore significantly stiffer than one with 1 kPa. The conversion between the two units is: 1 mmHg = 0.133322368 kPa at 0 °C.

Table 2.

The stiffness of tumor tissue is generally increased compared to healthy tissue in various cancer types. However, there is an exception in glioblastoma. Moreover, the stiffness of the tumor tissue rises due to the grade of malignancy of the cancer. The individual values vary between studies depending on the experimental preparation of the samples and/or very different biophysical analysis techniques that cannot be directly compared with each other.

The composition of solid primary tumors and their associated TME is well comprehended. The TME contains cancer cells and stromal elements, comprising ECM, basement membrane, vasculature, immune cells, and fibroblasts (Figure 7). During the course of cancer development and its advancement, all of its constituents undergo alterations in their physical structures and functionalities [221,222,223]. In many types of cancer, with only a few exceptional cases, primary tumors are generally more mechanically stiff in comparison to the healthy tissue from which they originated [161,208,221]. Mechanical brain cartography revealed that glioblastomas consist of both stiff and soft areas, which implies a high degree of heterogeneity within the tumor [208].

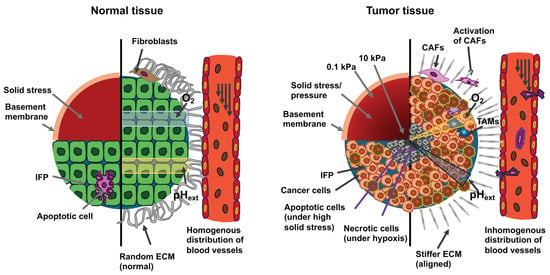

Figure 7.

The drawings illustrate cross-sections of normal tissue (left) and cancerous tissue (right). Cells in cancerous tissue are subjected to high solid stress from structural elements and interstitial fluid pressure (IFP). The upper left quadrant of the two cross sections displays the distribution of solid stress. The lower left quadrant displays the distribution of IFP. Tumor tissue exhibits higher stiffness with a gradient that declines from the tumor center to the circumference and a higher IFP compared to normal tissue. High solid stress in the range of 4 to15 mmHg promotes the motility of cancer cells, while solid stress above 37 mmHg stimulates the apoptosis of cancer cells. The right half of both cross-sections depicts the constituent cells and the mechanical/chemical cues within the microenvironment. Compared to normal cells, cancer cells exhibit aberrant shapes and unorganized structures. The ECM inside a solid tumor is stiffer, denser, more interconnected, and more oriented vertically to the margin of the tumor in comparison to the loose, relaxed and isotropic ECM present in healthy tissue. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) are also found within the tumor mass. The modified ECM promotes the development of tumors, invasion, migration, cancer metastasis, and the activation of cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs). Increased shear stress flow in the interstitial fluid of the primary tumor enhances the invasiveness and motility of cancer cells. Cancer cells can evade apoptosis, whereas normal cells are unable to escape it. The blood vessels in the primary tumor build a leaky and dendritic network that only penetrates the periphery of the primary tumor due to the strong limitation imposed by the center of the primary tumor. The hypoxia induced within the tumor by these abnormal blood vessels leads to an aberrant gradient of extracellular pH (pHext) and necrosis of the cancer cells. In contrary, in normal tissue, blood vessels can perfuse the entire tissue and generate normal oxygen/pHext amounts.

Stiffness levels were significantly decreased in glioblastomas, with a mean value of 1.32 ± 0.26 kPa in comparison to 1.54 ± 0.27 kPa in healthy tissue (p = 0.001) (Table 2). Nevertheless, some of the glioblastomas (5 out of 22) exhibited elevated stiffness [208]. Among the stiffer types of cancer are human breast tumors, which are five times stiffer compared to healthy tissue, with such increased stiffness positively associated with their malignancy [224]. The stiffness of human hepatic tissue is positively related to the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma, with a threshold value of 20 kPa [225]. In addition to general stiffening, another striking mechanical feature of cancerous tissue involves the heterogeneity of its intratumoral stiffness [226]. Measurement using ultrasound elastography reveals significant spatial differences in tissue stiffness within breast and liver cancers [227]. In biopsies of human breast tumors, the TME is seven times stiffer (E = 5.51 ± 1.70 kPa) than the center of the tumor (E = 0.74 ± 0.26 kPa), while the stiffness of healthy breast tissue ranges from 1.13 to 1.83 kPa, which leads to the concept of the nanomechanical signature of solid cancers [203]. Besides stiffness, the viscoelasticity of cancerous tissue also deviates from that of normal healthy tissue. For instance, in vivo measurements using magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) demonstrate that in humans, the fluidity of benign meningioma tissue exceeds that of aggressive glioblastoma tissue by a factor of 3.6. This solid-like nature of glioblastomas eases their aggressive spread to the neighboring tissue [228].

Moreover, similar to other tissues, the TME possesses complex mechanical properties, such as viscoelasticity, which is the load relaxation over time [229], and mechanical plasticity, which means irreversible deformation due to stress [185], which have been reported to impact the propagation or migration of cancer cells. ECM restructuring through cancer cells or activated stromal cells can alter the mechanical characteristics of the TME [230,231,232]. Stromal cells frequently release transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), which leads to increased accumulation and crosslinking of ECM constituents including collagen, fibronectin, hyaluronic acid and laminin [233,234,235,236,237,238]. In combination, enhanced ECM depositing and crosslinking increases the stiffness of the ECM, which impacts the phenotypes of the cancer cells [161]. Elevated stiffness stimulates the activation of fibroblasts and encourages myofibroblast phenotypes that are positive for alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA). α-SMA is encoded by Acta2 which is frequently coupled with the myofibroblast phenotype, that is triggered through the fibronectin isoform extradomain A fibronectin (EDA-FN) [239]. In contrary, in several fibrotic diseases, Acta2 and other contractile hallmarks are reduced, whereas EDA-FN secretion is elevated. Thus, the relationship is intricate and contextual, such as EDA-FN may promote the transition toward a contractile cellular phenotype. This creates a positive feedback circuit in which elevated levels of myofibroblast activation promote ECM secretion, ECM crosslinking, and contractility of myofibroblasts, leading to continued stiffening [240]. Myofibroblast-like cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are commonly regarded as cancer-promoting [241,242], however, some evidence suggests that they may also have anti-tumor effects according to fibroblast type and tissue context [243,244]. This is illustrated by a study that revealed hyaluronan secreted by CAFs has a tumor-promoting effect, whereas collagen I secreted by CAFs has a tumor-inhibiting effect [245]. The components and stiffness of the ECM may also have an implication for immune cells [246]. For instance, a collagen-rich, rigid ECM interferes efficiently with the infiltration of T-cells [247] and decrease the cytotoxic activity of them [248]. Nevertheless, it is uncertain whether increased ECM stiffness stimulates the polarization of M1 macrophages, which are pro-inflammatory and tumor-suppressing, or M2 macrophages, which are tumor-promoting [249,250]. Moreover, matrix stiffening decreases vascular proliferation and vascular integrity [251], and changes in the mechanosensory properties of endothelial cells via the Rho signaling route may account for vascular malfunction in the TME [15,252]. The stiffer microenvironment encircling primary solid cancers lead to the development of specific cancer cell phenotypes that can disseminate out of the primary cancer into the surrounding tissue. When cancer cells are exposed to increased stiffness in their primary cancer’s microenvironment beyond a certain threshold and/or for a certain duration, they can store this as mechanical memory. This acquired mechanical memory could help cancer cells to migrate efficiently to their target tissue for metastasis. Whether it also plays a role in selecting the target tissue for metastasis is still unclear, but it is quite possible. Moreover, this mechanical memory, a sustained adaptation of their cytoskeletal dynamics, improves their capacity to infiltrate and survive in new surroundings.

5.2. Cancer Cell Migration Through the ECM Microenvironment

The association between substrate stiffness and cancer cell migratory capacity is linked to the metastatic capacity of cancer cells, which is characterized by a mesenchymal or epithelial phenotype (Figure 4) [253]. Recently, an intriguing classification of cancer cells by Wang and Yan [254], which is presented in the following. Metastases are generally known to be accompanied by epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), which enables epithelial cancer cells to adopt mesenchymal characteristics and thereby achieve migratory capabilities [255,256]. Mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET) refers to the change in cancer cells from a mesenchymal-type to an epithelial-type form and restore proliferative capacity. Epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity (EMP) permits cancer cells to switch between several states of the epithelial-mesenchymal spectrum [257], which promotes the migration of cancer cells and their consecutive colonization of metastastic niches. The hysteresis of EMT concerns the retention of the mesenchymal state in mesenchymal cancer cells even after leaving the microenvironment that stimulates EMT [258]. The term hysteresis therefore denotes the phenomenon whereby the state of a system relies on its evolution/history, suggesting a type of memory process, similar to cellular memory, which may also be based on a mechanical memory in terms of increased stiffness. Hysteresis is linked to aggressive cancer and a worse prognosis [258]. The hybrid epithelial/mesenchymal phenotype is defined by cancer cells exhibiting both epithelial and mesenchymal characteristics. Cancer cells in this hybrid state tend to be extremely aggressive and are linked to the cancer stemness phenomenon [259]. On the basis of EMP, EMT hysteresis, and the hybrid epithelial/mesenchymal phenomena, a classification for cancer cells with EMP capability has been propounded [254]. This classification is intended to evaluate the performance of cancer cells throughout the spreading stage. This classification categorizes cancer cells with EMP potential into four groups, each with distinct biological properties and propagation characteristics, leading to different prognoses for the cancer. The first group comprises irreversible hysteresis-type cancer cells that can induce stochastic metastasis and display an oligometastatic and metachronous type of metastasis. The second group comprises weak hysteresis-type cancer cells that can give rise to distant metastases that are less effective. The third group covers highly hysteresis-type cancer cells that can take on a temporary hybrid epithelial/mesenchymal phenotype and are able to undergo effective metastasis. The fourth group encompasses stable cancer cells exhibiting a hybrid epithelial/mesenchymal phenotype, which tend to be highly aggressive and capable of metastasizing fast and widespread.