Abstract

While deep fertilization improves crop yields and fertilizer use efficiency, it alters crop growth and soil nutrient/moisture distribution, driving nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions—a potent greenhouse gas. However, conflicting evidence and the unknown effects of varying fertilizer placement depths in mechanized rapeseed fields leave the critical trade-off between productivity and emissions mitigation poorly understood. A 2-year field experiment (2019–2021) was conducted in the Yangtze River basin, China. The static closed chamber technique combined with gas chromatography was utilized to investigate the impacts of fertilizer placement depths (5 cm, 10 cm, and 15 cm, designated as D5, D10, and D15, respectively) on soil N2O emissions, with a no-fertilization treatment serving as the control. Results demonstrated that N2O fluxes under all treatments exhibited a rapid decline during the early growth stages of rapeseed, subsequently stabilizing at low levels; these dynamics were partially linked to soil temperature and soil water content (SWC). Specifically, N2O flux showed a significant but moderate exponential response to soil temperature and a weak quadratic trend with SWC. As fertilization depth increased, the richness and diversity of AOA, AOB, and nirK communities showed a numerical decline (p > 0.05). N2O emissions under D5 were on average 8.7% higher than D10 (p > 0.05), but were significantly 18.0% higher than D15 (p < 0.05). Yield-scaled N2O emissions under D10 were reduced by 12.7% and 22.3% relative to D5 and D15, respectively. Compared with D10 and D15, the N2O emission factor increased by 12.9% and 29.0% under D5, respectively (p < 0.05). The net ecosystem economic budget under D10 was 6.5% and 48.6% greater than that of D5 and D15, respectively. Considering crop yield, production costs, and carbon emission, a fertilizer placement depth of 10 cm is recommended as optimal. These findings offer valuable insights for mitigating N2O emissions and informing rational fertilization strategies in rapeseed cultivation.

1. Introduction

The issue of global warming, driven by greenhouse gas emissions, has emerged as a significant environmental challenge. Among these gases, nitrous oxide (N2O) is particularly noteworthy, because it has an atmospheric lifetime of approximately 120 years and a global warming potential 298 times that of CO2 across a 100-year period [1]. Beyond its role in climate change, N2O is a key ozone-depleting substance, making emission reduction critical. N2O comes primarily from agricultural soils, accounting for roughly 69% of human-induced N2O [2]. Fertilization is a primary driver of N2O emissions from agricultural soils, with fertilization-related soil N2O emissions constituting approximately 70% of total soil N2O emissions [3]. Concurrently, fertilization is essential for ensuring high and stable crop yields, being crucial for achieving national food security [4]. Consequently, the development and implementation of scientifically informed and optimized fertilization strategies that enhance crop productivity while minimizing N2O emissions are vital for both sustainable food production and environmental conservation.

The “4R” fertilization technology—comprising the right amount, type, timing, and placement of fertilizer—has been proposed and implemented in agricultural practices [5]. Presently, excessive fertilizer use is prevalent across farmlands in China, contributing significantly to both atmospheric pollution and non-point source pollution. In pursuit of sustainable agricultural development, the Chinese government has prioritized chemical fertilizer reduction in its annual ‘No. 1 Central Document’. Specifically, the ‘Action Plan for Zero Growth of Fertilizer Use’ launched in 2015 has guided the transition toward improved fertilizer use efficiency for major crops. Although reduced fertilization has been extensively implemented in agriculture, it may lead to a decreased crop production [6,7], thereby creating a tension between maintaining stable yields and achieving emission reductions. Deep fertilizer application, which involves placing fertilizer into deeper soil layers characterized by dense root systems and heightened root activity, has been identified as a cost-effective and efficient agronomic technique [8]. This method offers the dual benefits of fertilizer conservation and yield enhancement, positioning it as a pivotal technology in fertilizer reduction strategies [9]. Deep fertilization has been widely explored for its impact on crop productivity across various crops, including rice [10], maize [11], and wheat [12]. These investigations generally indicate that deep fertilizer application can augment crop productivity. Moreover, deep fertilizer placement influences crop growth dynamics [9], as well as the distribution and movement of soil nutrients and moisture [13], which in turn affect soil N2O emissions. Given the global imperative to mitigate climate change, considerable attention has been directed toward understanding how deep fertilizer application impacts N2O emissions in agricultural soils. Some researchers have reported that deep fertilizer application increases soil N2O emissions in rice fields [10] and dryland cropping systems, including maize, rapeseed, and wheat-corn-soybean rotations [14]. Conversely, other researchers have demonstrated that deep burial placement of fertilizer mitigates N2O emissions in rice [15], maize [16], and wheat fields [17]. Therefore, the current body of literature presents conflicting findings regarding how deep placement of fertilizer affects soil N2O emissions, underscoring the necessity for further empirical investigation in this domain.

Rapeseed represents one of the most significant oil crops worldwide and constitutes the largest oil crop cultivated in China. The advancement of rapeseed production within China is critical to ensuring a stable supply of edible oil. In 2023, the rapeseed cultivation area in China reached 7.5483 million hectares, accounting for 17.4% of the global rapeseed planting area [18]. The Yangtze River basin, as the principal rapeseed-producing region in China, predominantly cultivates winter rapeseed, with its planting area comprising over 85% of the national total. Prior research has demonstrated that winter rapeseed fields contribute substantially to soil N2O emissions, with emissions during the growing season accounting for 19.6% to 53.2% of annual soil N2O fluxes [19,20]. Consequently, there is a need to explore N2O emission reduction strategies from winter rapeseed cultivation. Existing studies have primarily concentrated on the types and quantities of fertilizers applied [21,22], with limited research addressing the impact of deep fertilizer placement on soil N2O emissions in rapeseed fields. Moreover, the influence of varying fertilization depths on N2O emissions remains unexplored. As widely recognized, the biological potential for N2O production and consumption is ultimately determined by the soil microbial community structure and functional gene abundance [19,20]. Specifically, the balance between nitrite reductase (nirK/nirS) and nitrous oxide reductase (nosZ) genes controls the N2O/(N2O + N2) product ratio [19,20]. However, it remains unclear how vertical spatial variations in fertilizer placement affect these genomic indicators and whether these microbial shifts align with surface gas fluxes in mechanized rapeseed systems.

Therefore, a 2-year field experiment was conducted employing static closed chamber technique coupled with gas chromatography to investigate the effects of varying fertilizer placement depths—defined as the subsurface banding of granular fertilizer—on soil N2O emissions in rapeseed fields. It was hypothesized that optimal deep fertilizer placement could reduce soil N2O emissions by altering nitrifying and denitrifying microorganisms while enhancing economic returns (e.g., increased rapeseed yields). This study aimed to (1) evaluate the impact of deep fertilizer placement on soil N2O emissions in winter rapeseed fields, and (2) determine the optimal fertilizer placement depth that balances rapeseed yield enhancement with N2O emissions reduction.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Site

A field experiment was conducted in Jianli County, Jingzhou City in Hubei Province in the Yangtze River basin (113°01′14′′ E, 29°48′47′′ N, altitude 29 m) from October 2019 to May 2021. Two adjacent but distinct experimental sites within Jianli County were utilized: a paddy field during the 2019–2020 period and dry land during the 2020–2021 period. The preceding crops for the winter rapeseed cultivation were rice in the 2019–2020 season and soybean in the 2020–2021 season [23]. The region has a mean annual sunshine duration of 2000 h, a mean yearly rainfall of 1226 mm, a mean temperature of 16.3 °C, and a frost-free period of 255 days. The soil was classified as sandy loam soil [23]. Soil physicochemical properties of the top 20 cm layer are presented in Table 1. Soil bulk density was determined by the cutting ring method. Total N was determined using the Kjeldahl method (K1160, Hanon Future Technology Group Co., Ltd., Jinan, China) after H2SO4-H2O2 digestion [24]. Total P was quantified using the molybdenum blue colorimetric method following the extraction of the samples with HClO4-H2SO4 [25] using a flame spectrophotometer (UV-1800PC, Shimadzu Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Total K was determined by flame photometer (Hitachi Z-2000, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) after NaOH fusion [25]. Soil pH was measured by a pH meter.

Table 1.

Soil physicochemical properties at the test site.

2.2. Experimental Design

Four treatments were designed: a control without fertilization (F0) and three fertilizer band placement depths at 5 cm (D5), 10 cm (D10), and 15 cm (D15). Granular compound fertilizer was applied via subsurface banding at the designated depths. Both deep fertilization and sowing were carried out using a 2BFQ-6 combined rapeseed seeder and deep fertilizer device developed by Huazhong Agricultural University (Wuhan, China), as described by Chen et al. [23]. Field verification was performed immediately after fertilization and sowing by excavating soil cross-sections (n = 5 per plot). The actual fertilizer placement depths were 5.1 ± 0.6 cm, 9.6 ± 0.5 cm, and 14.7 ± 0.7 cm for the D5, D10, and D15 treatments, respectively. These measurements confirmed that the treatments were statistically distinct and non-overlapping. Since the fertilizer was placed centrally within the rows [23], the lateral distance was mechanically fixed at 14 cm from the seed rows for all fertilization treatments, ensuring a consistent horizontal separation between seeds and fertilizer bands to avoid seedling toxicity. In our experiment, a randomized complete block design was employed in this study, with three replicates. Each plot, sized at 30 m × 2 m, was considered the experimental units for a replicate.

Rapeseed seeds of the cultivar ‘Huayouza 62’ were sown on 10 October 2019 in the 2019–2020 season and on 21 October 2020 in the 2020–2021 season. The seeding rate was 4.5 kg ha−1. For each plot, six planting rows, spacing 28 cm, were applied. All deep-fertilized treatments received 750 kg ha−1 of ‘Yishizhuang’—a rapeseed-specific slow-release fertilizer (N 25%, P2O5 7%, K2O 8%, and B ≥ 0.15%)—band-placed at sowing as a basal dose. Here, the nitrogen was provided in ammonium, nitrate, and amide forms. Phosphorus was applied as P2O5 derived from calcium magnesium phosphate and monoammonium phosphate. Potassium was supplied as K2O in the form of potassium chloride. No additional topdressing fertilization was administered during the growing period. Harvesting of the rapeseed crops occurred on 3 May 2020 and 2 May 2021, for the respective seasons. All other agronomic management practices followed the local standard procedures.

2.3. Measurements and Methods

2.3.1. Nitrous Oxide Flux Measurement

The static closed chamber technique combined with gas chromatography was used to quantify soil N2O fluxes, as described by Chen et al. [21]. The chamber apparatus comprised three parts: a base frame, a middle box, and a top box. The base, measuring 50 cm × 50 cm × 15 cm, was constructed from stainless steel and embedded to a depth of 10 cm into the soil after sowing. Its upper edge featured a groove designed for water-filling, thereby isolating the chamber’s internal environment prior to gas sampling. The middle box (50 cm × 50 cm × 70 cm) and the top box (50 cm × 50 cm × 50 cm) were fabricated from 6 mm-thick PVC and insulated with sponge and tinfoil to mitigate temperature fluctuations caused by solar radiation during sampling. A groove at the top of the middle box accommodated the top box, allowing adjustment according to crop height. An electric fan installed on the side of the top box facilitated air mixing within the chamber, while a thermometer positioned at the top recorded internal temperature. Gas sampling was performed at an average interval of every eight days during the seedling stage and every 17 days from flowering to maturity stage. The frequency was increased to capture emission peaks following fertilization and precipitation events [21], with measurements taken within three days after such events. Due to travel restrictions and laboratory closures during the COVID-19 pandemic, targeted high-frequency sampling immediately following all heavy rainfall events was not consistently feasible. However, efforts were made to maintain a regular monitoring schedule to capture the representative seasonal variations while adhering to safety protocols. Sampling was conducted during 9:00−11:00 am local time to capture a representative mean daily N2O flux value [26,27]. Gas was collected at 0, 10, 20, and 30 min following chamber closure. Syringes with a capacity of 60 mL and equipped with three-way valves were utilized to extract 50 mL gas samples four times per sampling event. These samples were stored and transported with 10 mL glass bottles, which were in pre-evacuated sealed with silicone rubber stoppers. N2O concentrations were analyzed in the laboratory via gas chromatography (GC; model 7890 A, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The static closed chamber method operates under the assumption that gas accumulation within the chamber, reflected by changes in N2O concentration over time, follows a linear trend during short measurement intervals. This assumption is valid only when high linearity is observed. To ensure data quality and avoid errors arising from gas leakage, inadequate mixing, insufficient equilibration time, or analytical inaccuracies, sample sets exhibiting a linear regression coefficient (R2) below 0.90 were excluded from analysis. N2O flux was subsequently determined using the calculation method outlined in Dong et al. [28].

Cumulative N2O emissions were calculated by linear interpolation and numerical integration between sample times [22]:

where C is cumulative N2O emissions, kg ha−1; Fi and Fi+1 are the N2O flux at the i and i + 1st sampling, μg m−2 h−1; i is the sampling time; n is the total number of sampling intervals; Di+1 − Di is the number of days between two adjacent sampling time, d; 24 is the conversion coefficient of day to hour; and 10−5 is the conversion coefficient of μg m−2 to kg ha−1.

Yield-scaled N2O emissions were calculated as the ratio of cumulative N2O emissions to rapeseed yield [11]:

where YN2O is yield-scaled N2O emissions, kg t−1; Y is rapeseed yield, kg ha−1; and 10−3 is the conversion coefficient of kg to t.

The N2O emission factor was determined following the procedure of Wu et al. [11] and Rychel et al. [17]:

where f is the N2O emission factor, %; CF and C0 are the cumulative N2O emissions during the entire growth period of rapeseed treated with fertilization and without fertilization, respectively, kg ha−1; and FN is the nitrogen application amount, kg ha−1. Here, the FN was 187.5 kg N ha−1 for all fertilized treatments.

2.3.2. Soil Parameters

Except for the 44th, 89th, and 101st days after sowing in 2019–2020, soil samples of the 0–10 cm soil layer, which reflected the most dynamic hydrological zone sensitive to evaporation, were collected at the initial, middle, and final points of each plot when sampling gas to measure soil water content (SWC, %). These three soil samples were combined as a replicate. SWC was measured gravimetrically by oven-drying soil samples at 105 °C to achieve constant weight. Soil temperature at a depth of 10 cm was recorded using a geothermometer during gas sampling events throughout the 2019–2020 and 2020–2021 rapeseed growing seasons.

At harvest, soil samples of 0–20 cm soil layer, which represented the entire plow layer, were taken at the initial, middle, and final points of each plot using a soil auger. To avoid the direct influence of localized nutrient concentrations from the fertilization bands, each soil core was collected from the midpoint between the plant row and the fertilization belt. The 0–20 cm continuous vertical cores ensured the inclusion of soil across all fertilization depths. A composite sample was created by combining these three soil samples as one replicate. Then, soil samples were crushed and passed through a 100-mesh sieve and dried at 55 °C to a constant weight. Soil total carbon (STCC) and nitrogen (STNC) contents were determined by an Elementar vario MACRO cube elemental analyzer (Langenselbold, Germany) via the dry combustion method [29].

To assess the overall nitrogen transformation potential within the primary root zone, 0–20 cm soil samples obtained at harvest were utilized to assess the functional genes associated with nitrifying and denitrifying microorganisms. Field-collected samples were transported in an ice box maintained at 4 °C and subsequently frozen at −20 °C in sterile centrifuge tubes in the laboratory for total soil DNA extraction. Quantification of functional genes related to nitrifying microorganisms—specifically ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA) and ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB)—and denitrifying microorganisms, characterized by the nitrite reductase gene (nirK), was conducted via real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) using an ABI7500 system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The evaluation of four α-diversity indices (Shannon/Simpson: species diversity; ACE/Chao: species richness) was performed for bacterial and fungal community diversity. Detailed information regarding primers, primer sequences, fragment lengths, and qPCR conditions for each gene is provided in Table 2. All procedures adhered to the methodology described by Xu et al. [19].

Table 2.

Amplification primers and reaction conditions for real-time quantitative PCR.

2.3.3. Crop Yield

At harvest, three representative square sections measuring 1.12 m by 1.12 m were systematically chosen in each plot to assess the rapeseed yield. Following sun-drying and threshing of the plants, seed yield was determined in accordance with Chen et al. [23]. The mean value obtained from these replicates was used to represent the yield for each treatment.

2.3.4. Net Ecosystem Economic Budget (NEEB) Calculation

The NEEB is an assessment indicator, which integrates crop yield, production costs, and greenhouse gas–related losses expressed as global warming potential (GWP). The NEEB thereby provides an integrated measure of the net ecological and economic benefits of agricultural management practices [15]. Incorporating NEEB into the analysis facilitates the identification of optimal trade-offs between yield enhancement and N2O emission reduction, and offers a more practice-oriented basis for determining appropriate fertilizer placement depths in winter rapeseed production. The NEEB was calculated as follows [15]:

where NEEB is net ecosystem economic budget, $ ha−1; Yc is rapeseed yield costs, which refer to the rapeseed yield multiplied by the corresponding market price, $ ha−1; Ac is agricultural activity costs, which include costs of pesticide, seed, fertilizer, machine, and labor, $ ha−1; GWPc is GWP cost, which is the product of carbon-trade price (15.12 $ t−1 CO2-eq.) and GWP [30]. Here, GWP (t ha−1) is the cumulative N2O emissions multiplied by its radiative forcing potential (298).

NEEB = Yc − Ac − GWPc

2.4. Statistical Analyses

Data were collected and processed using Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Variance analysis using a linear mixed-effects model (LMM) and regression analysis were conducted via PASW Statistics 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), with statistical significance determined at p < 0.05. Fertilization was defined as a fixed effect. To account for the variability introduced by different experimental years, sites, and pre-crops, the ‘Year-Site-Pre-crop’ combination was included as a random effect in the model. This statistical structure helps to partition the variance and more accurately evaluate the consistent effects of fertilization depth across different environments. In addition to null hypothesis significance testing, 95% confidence intervals were calculated to estimate the precision of the means for cumulative N2O emissions, seed yield, yield-scaled N2O emissions, and N2O emission factor. The Cohen’s d effect sizes were calculated to quantify the magnitude of differences between fertilizer placement depths, with d values of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 interpreted as small, medium, and large effects, respectively. Graphs were created with SigmaPlot 12.5 (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA) and OriginPro 2022 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA). Analyses of alpha diversity and relative abundance of AOA, AOB, and nirK genotype were conducted via the Miji I-Sanger cloud platform.

3. Results

3.1. Climate and Soil Variables

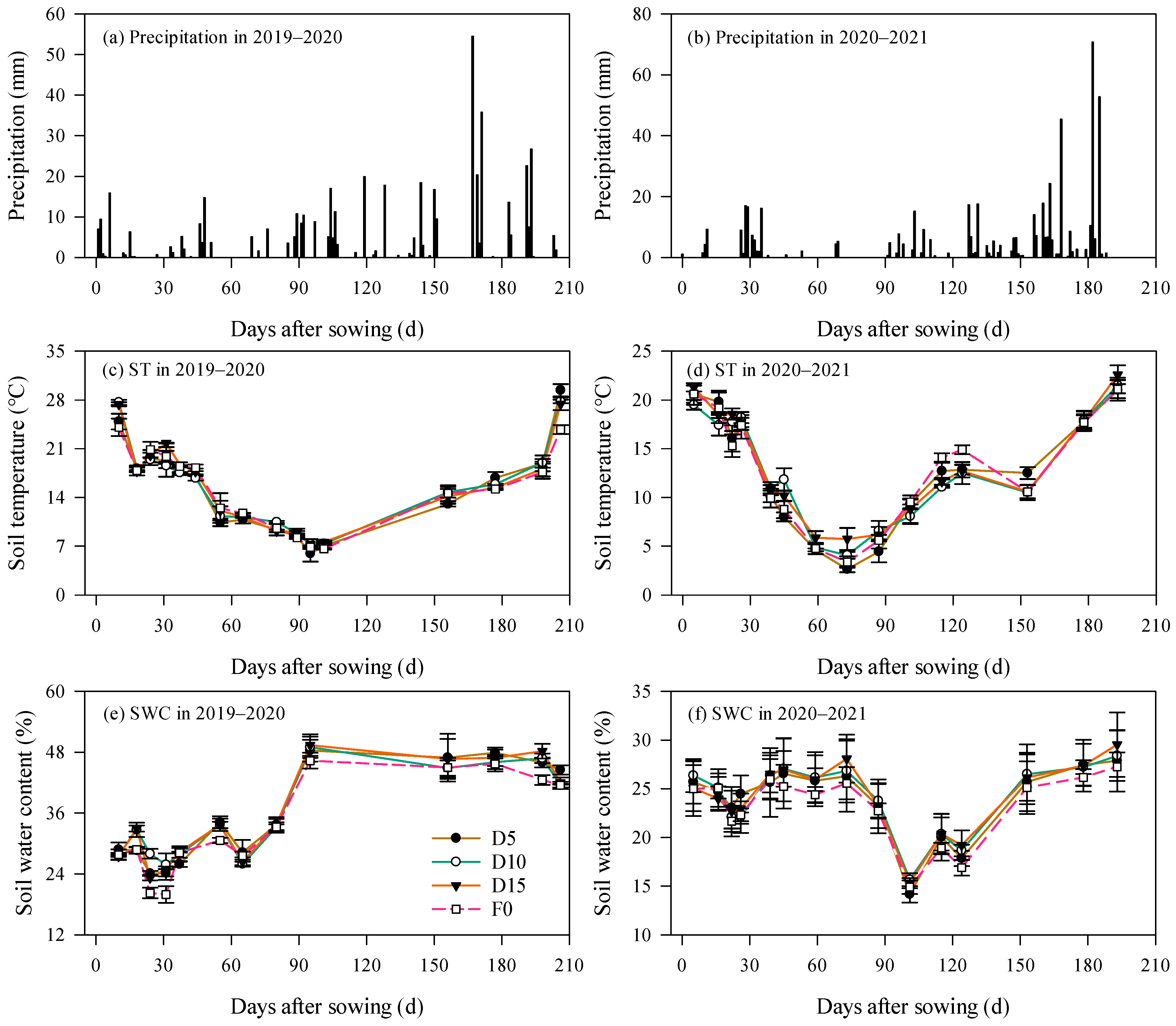

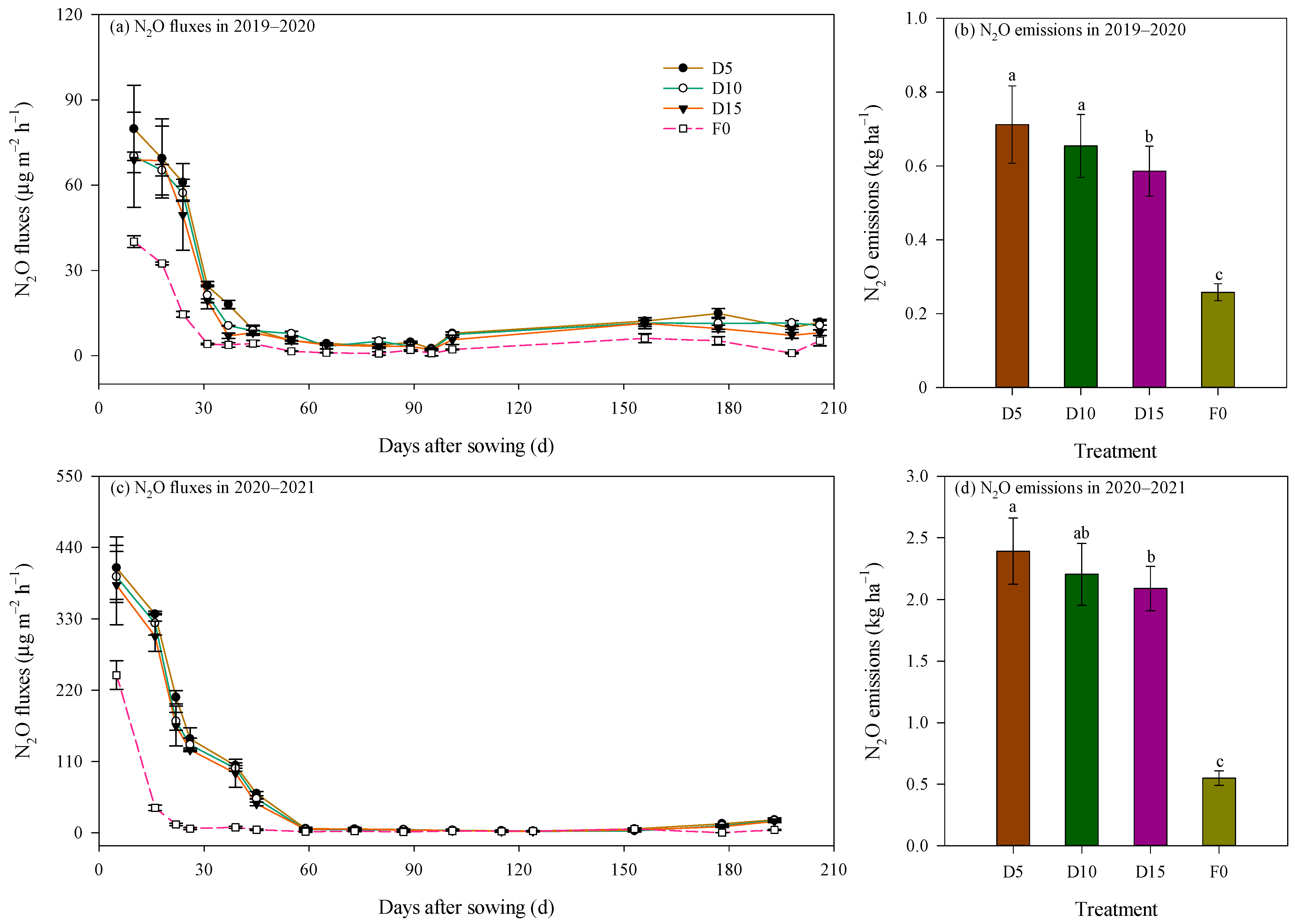

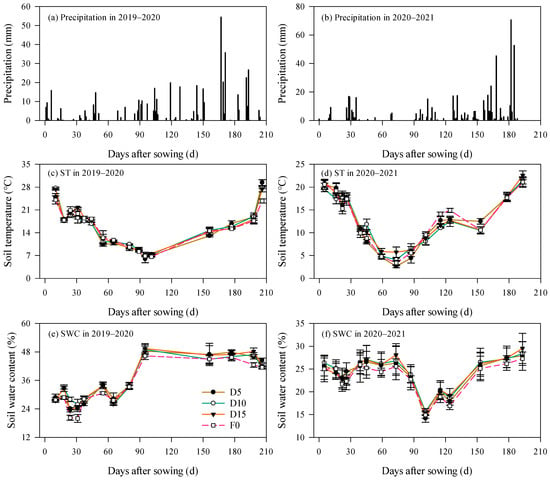

Figure 1 illustrates the dynamics of precipitation, soil temperature, and soil water content (SWC) across two rapeseed growing seasons. Total precipitation recorded during the 2020–2021 season amounted to 528.8 mm, representing a 10.2% increase relative to the 2019–2020 season. Precipitation was predominantly concentrated between March and May (Figure 1a,b), accounting for 51.2% and 57.9% of the total precipitation during the rapeseed growing periods in 2019–2020 and 2020–2021, respectively.

Figure 1.

Dynamics of precipitation, soil temperature (ST), and soil water content (SWC) under no fertilization (F0), fertilizer placement depth of 5 cm (D5), 10 cm (D10), and 15 cm (D15). Error bars represent standard errors.

Throughout the rapeseed growing seasons, soil temperature under different treatments generally exhibited a “V”-shaped pattern (Figure 1c,d). The minimum soil temperatures were observed 95 and 73 days after sowing (DAS) in the 2019–2020 and 2020–2021 seasons, respectively, with mean values of 6.8 °C and 3.9 °C on these dates. Soil temperatures were comparatively elevated during both the sowing period and at harvest. Specifically, in 2019–2020, the average soil temperature during sowing and at harvest was 26.0 °C (24.1–27.7 °C) and 27.1 °C (23.8–29.4 °C), respectively, corresponding to increases of 28.5% and 25.7% compared with the 2020–2021 season. Notably, differences of soil temperature among treatments were not significant (p > 0.05).

SWC measured at a 0–10 cm soil depth remained relatively low within the first 80 DAS in the 2019–2020 season, fluctuating between 19.9% and 34.1%. Beyond 80 DAS, SWC increased substantially, ranging from 41.5% to 49.4% (Figure 1e). In contrast, during the 2020–2021 season, SWC varied between 21.7% and 28.1% within the initial 73 DAS. Between 73 and 101 DAS, SWC exhibited a declining trend, reaching a minimum average of 15.0% (14.2–15.7%). Following 101 DAS, SWC across all treatments demonstrated an overall upward trajectory (Figure 1f), with the average SWC rising to 28.3% (27.3–29.5%).

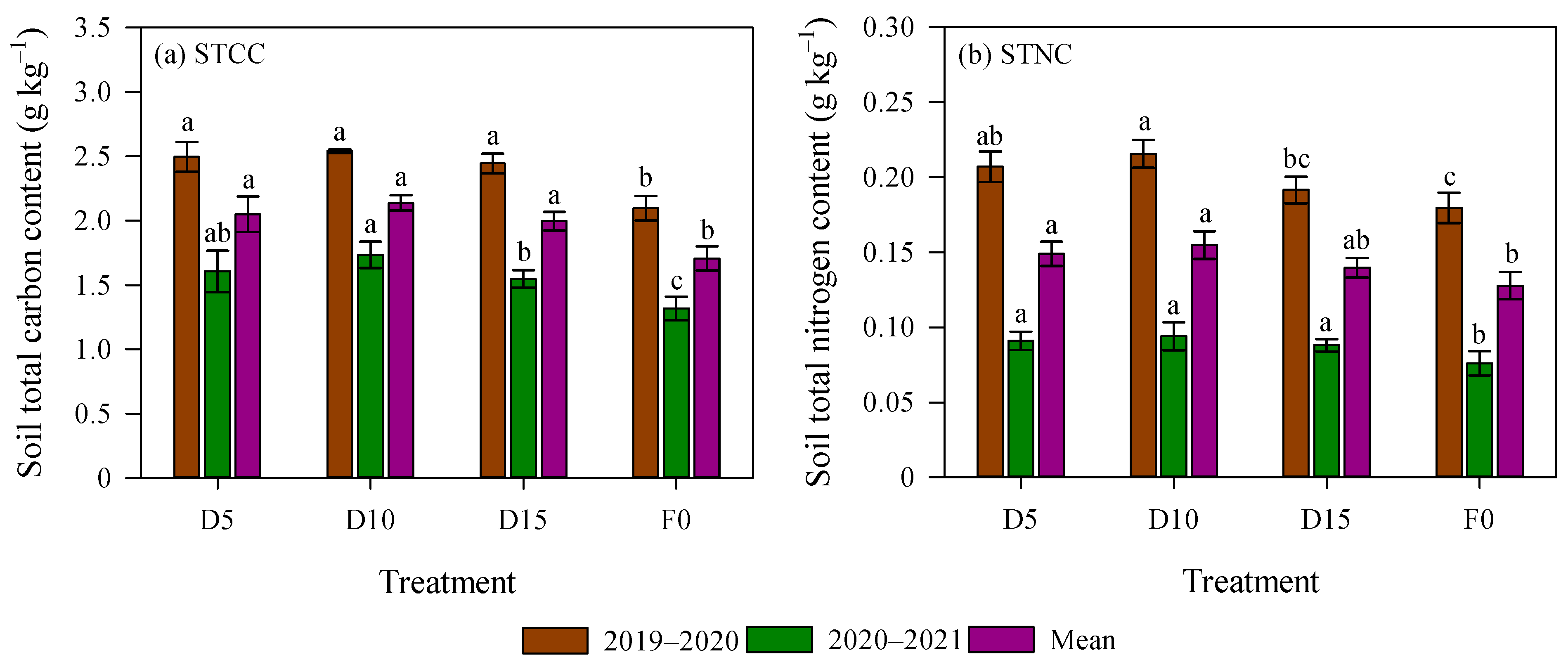

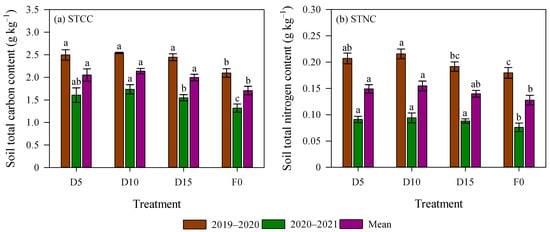

The growing season significantly influenced STCC and STNC (p < 0.05, Figure 2). Specifically, STCC and STNC in the 2019–2020 season were 1.55 and 2.28 times greater, respectively, than in the 2020–2021 season. Relative to the F0 treatment, STCC under deep fertilization treatment increased by 19.0% and 23.7% in the 2019–2020 and 2020–2021 seasons, respectively (p < 0.05). Additionally, in the 2020–2021 season, STNC under deep fertilizer application was significantly elevated by 19.7% than the F0 treatment. Regarding the effect of fertilizer placement depth, no significant differences were detected for STCC in 2019–2020 or for STNC in 2020–2021. However, STCC under D10 in 2020–2021 and STNC under D10 in 2019–2020 were significantly 12.1% and 12.6% higher, respectively, relative to the D15 treatment (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Soil total carbon content (STCC) and soil total nitrogen content (STNC) as affected by deep fertilizer application. Error bars represent standard errors. Different lowercase letters mean significant differences for each growing season at p < 0.05. Treatment abbreviations are described in Figure 1.

3.2. Diversity and Abundance of Nitrifier and Denitrifier

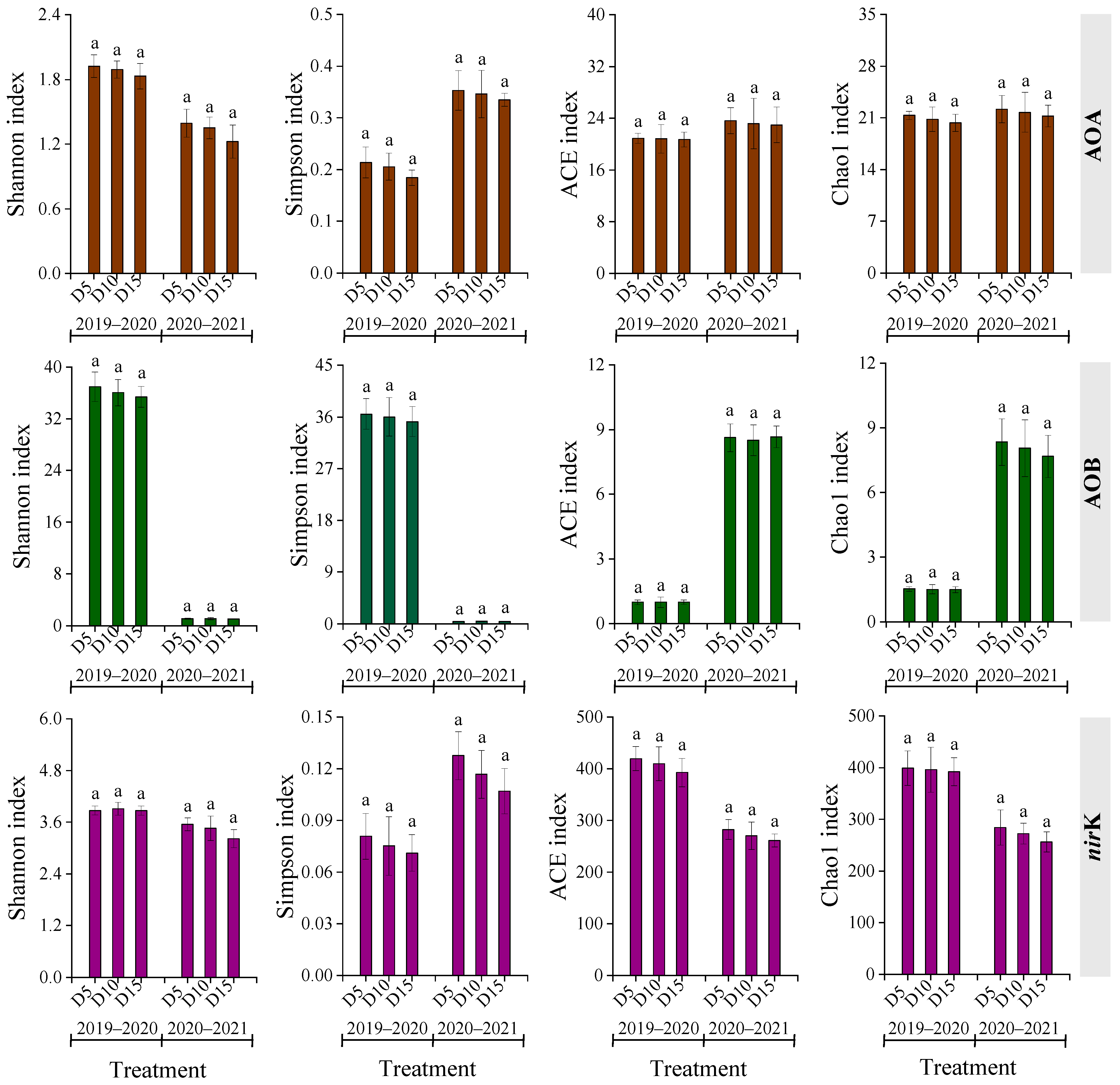

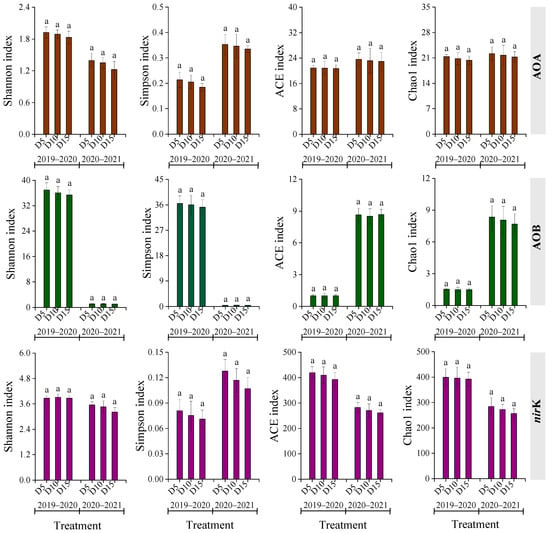

Alpha diversity of AOA, AOB, and nirK genotypes varied among treatments across two rapeseed growing seasons (Figure 3). Except for the ACE and Chao1 indices of AOA, the growing season significantly impacted the other diversities of AOA, AOB, and nirK genes (p < 0.05). A general trend of diversity indices following the order D5 > D10 > D15 was observed consistently across both seasons. Nonetheless, differences are not significant (p > 0.05).

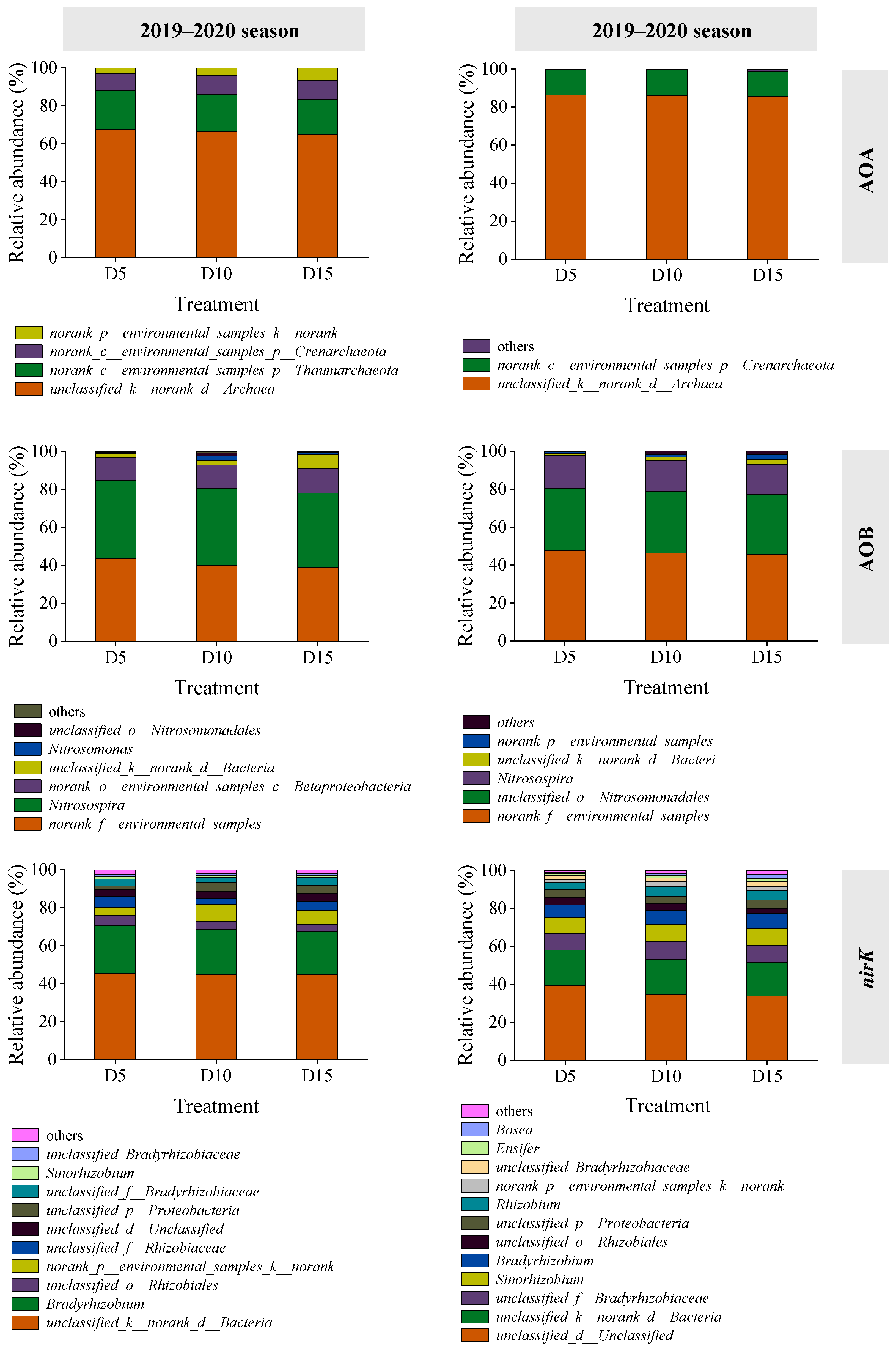

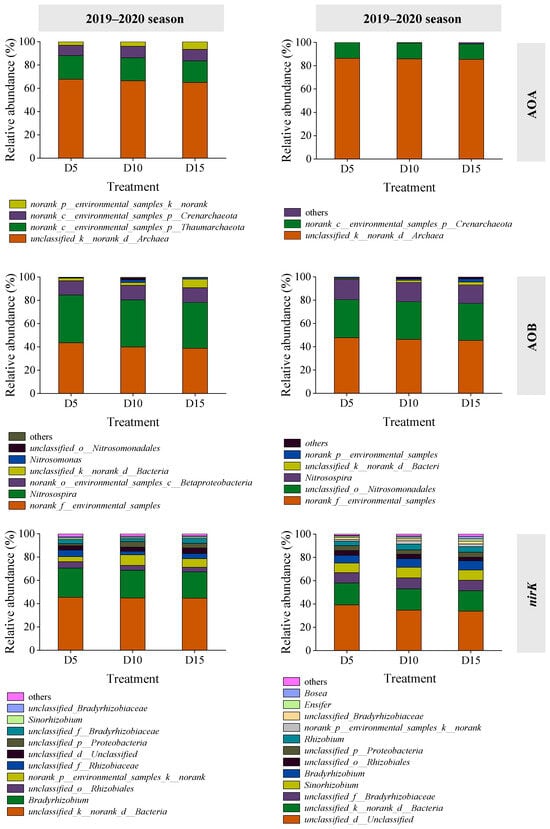

Four and three species or groups of AOA were identified in the 2019–2020 and 2020–2021 seasons, respectively (Figure 4). The dominant group was classified as Unclassified_k__norank_d__Archaea, representing 65.0–67.8% and 85.5–86.4% of the total AOA gene sequences in the respective seasons. The AOB community comprised seven species or groups in 2019–2020 and six in 2020–2021 (Figure 4). In 2019–2020, norank_f__environmental_samples and Nitrosospira were predominant, accounting for 38.8–43.6% and 39.4–41.0% of total AOB gene sequences, respectively. In 2020–2021, norank_f__environmental_samples and unclassified_o__Nitrosomonadales dominated, constituting 45.4–47.8% and 31.8–32.6% of the total AOB gene sequences, respectively.

Figure 4.

Relative abundance of AOA, AOB, and nirK genotype as affected by deep fertilizer application. Treatment abbreviations are described in Figure 1.

Regarding nirK genotypes, 11 and 13 species or groups were detected in the 2019–2020 and 2020–2021 seasons, respectively (Figure 4). The dominant groups in 2019–2020 were Unclassified_k__norank_d__Bacteria and Bradyrhizobium, accounting for 44.8–45.5% and 22.5–25.0% of total nirK gene sequences, respectively. In 2020–2021, Unclassified_d__Unclassified and Unclassified_k__norank_d__Bacteria were predominant, representing 33.7–39.1% and 17.6–18.8% of total nirK gene sequences, respectively. An increase in fertilization depth was associated with a slight decline in the dominant genera in AOA, AOB, and nirK communities; however, differences did not differ significantly (p > 0.05).

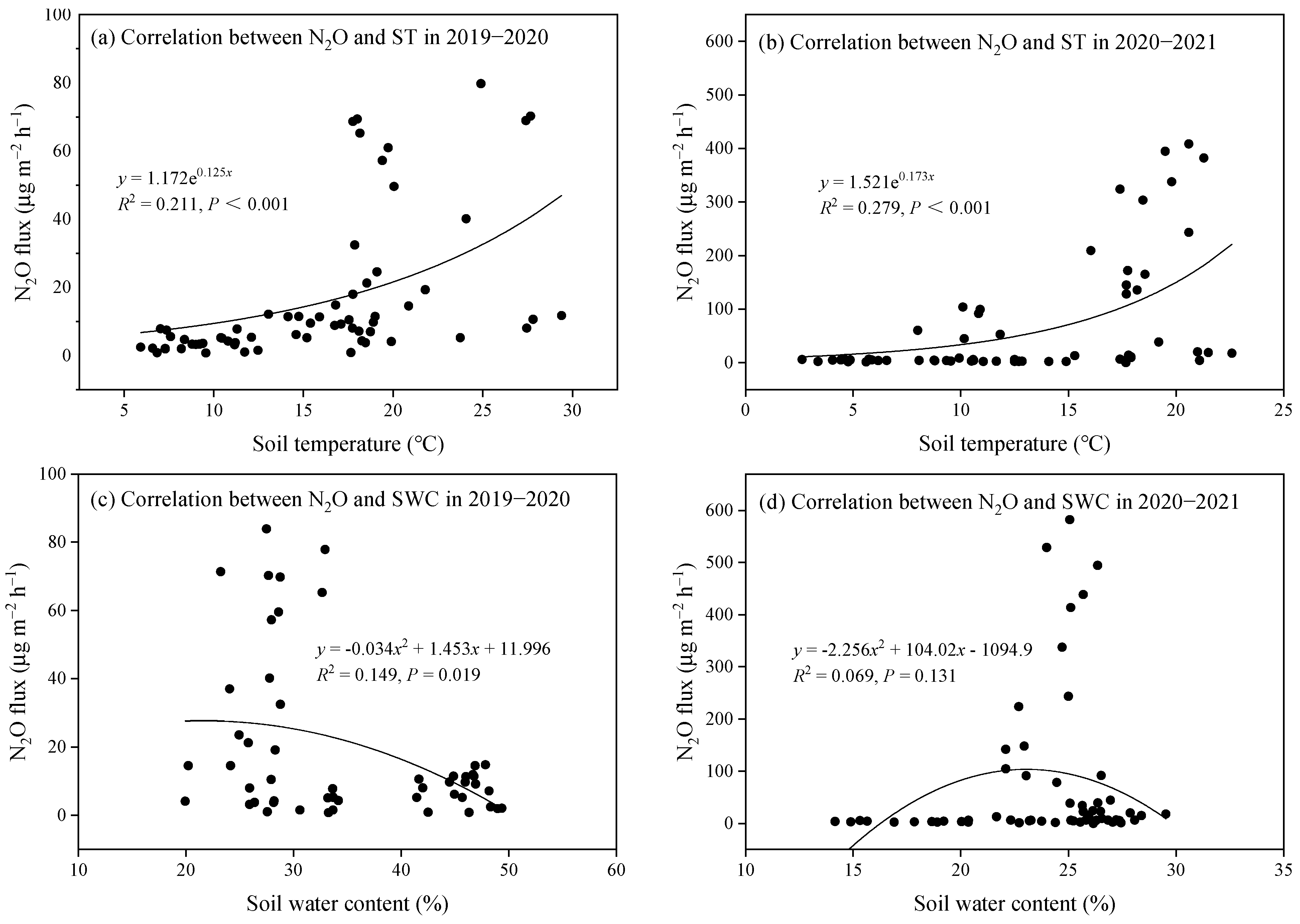

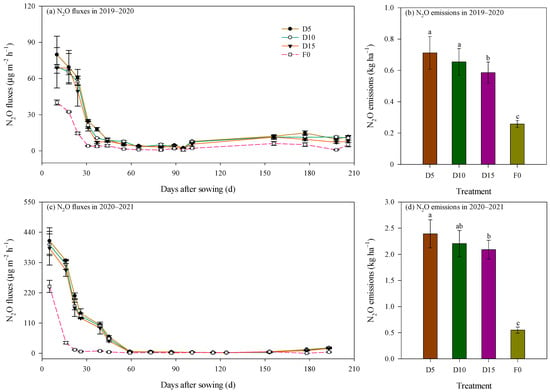

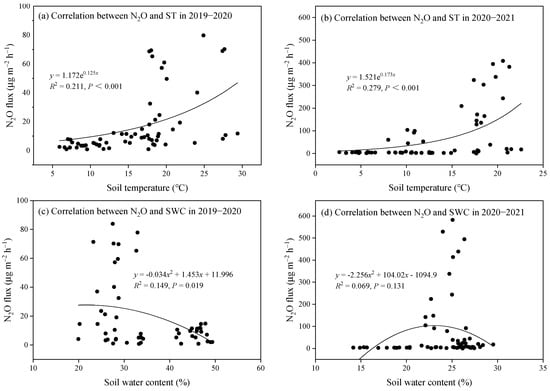

3.3. N2O Flux

Soil N2O flux in each treatment during the two growing seasons exhibited comparable temporal patterns: a rapid decline in N2O flux was detected during the early growth stages of rapeseed, followed by sustained low emission levels in the later stages (Figure 5). Specifically, in the 2019–2020 season, soil N2O flux decreased from a range of 40.12–79.78 μg m−2 h−1 to 1.56–7.78 μg m−2 h−1 within 55 DAS. In the 2020–2021 season, fluxes declined from 243.30–408.41 μg m−2 h−1 to 2.45–5.86 μg m−2 h−1 within 73 DAS. Correlation analysis revealed a significant but moderate exponential trend, where N2O flux increased with soil temperature (p < 0.001; Figure 6a,b). Additionally, N2O flux showed a significant but weak quadratic relationship with SWC during the 2019–2020 season (p = 0.019, R2 = 0.149; Figure 6c), indicating that SWC partially explained the temporal variation in N2O flux.

Figure 5.

Dynamics of N2O fluxes and cumulative N2O emissions as affected by deep fertilizer application. Error bars represent standard errors and 95% confidence intervals for N2O fluxes and N2O emissions, respectively. Treatment abbreviations and lowercase letters are described in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Figure 6.

Relationship between N2O flux with soil temperature (ST) and soil water content (SWC).

Mean N2O flux under fertilization treatments was significantly elevated, being 2.47 and 3.68 times greater than the F0 treatment during the 2019–2020 and 2020–2021 seasons, respectively (p < 0.01; Figure 5). The average N2O flux over the entire rapeseed growth period under the D5, D10, and D15 fertilization regimes was 21.17, 19.19, and 17.56 μg m−2 h−1, respectively, in 2019–2020. Corresponding values for the 2020–2021 season were notably higher, recorded at 88.79, 82.29, and 78.08 μg m−2 h−1, respectively.

3.4. Cumulative N2O Emissions, Yield-Scaled N2O Emissions, and N2O Emission Factor

Cumulative N2O emissions were recorded at 0.26–0.71 kg ha−1 in the 2019–2020 season and at 0.55–2.39 kg ha−1 in the 2020–2021 season (Figure 5b,d). Both the growing season and fertilization exerted obvious impacts on cumulative N2O emissions (p < 0.05; Table 3). Notably, cumulative N2O emissions in 2020–2021 were 3.11 times greater than those recorded in 2019–2020. The mixed-effects model revealed that the growing season accounted for 90.46% of the total variance in N2O emissions (Table 3). Treatments involving deep fertilization resulted in cumulative N2O emissions that were 3.28 times greater than the F0 treatment. In the 2019–2020 season, cumulative N2O emissions followed the pattern D5 = D10 > D15, whereas in 2020–2021, N2O emissions decreased with increasing fertilization depth, with a statistically significant difference between D5 and D15. Across both seasons, the D5 treatment exhibited an average increase of 8.7% and 18.0% in N2O emissions compared with the D10 and D15 treatments, respectively. The difference was significant between D5 and D15 treatments (p = 0.037). This reduction corresponded to a large effect size with Cohen’s d value of 3.55 in the 2019–2020 season and of 3.29 in the 2020–2021 season, indicating a substantial practical benefit of optimizing placement depth.

Table 3.

Summary of linear mixed-effects model results and variance partitioning for N2O emissions, seed yield, yield-scaled N2O emissions, N2O emission factor, and net ecosystem economic budget (NEEB).

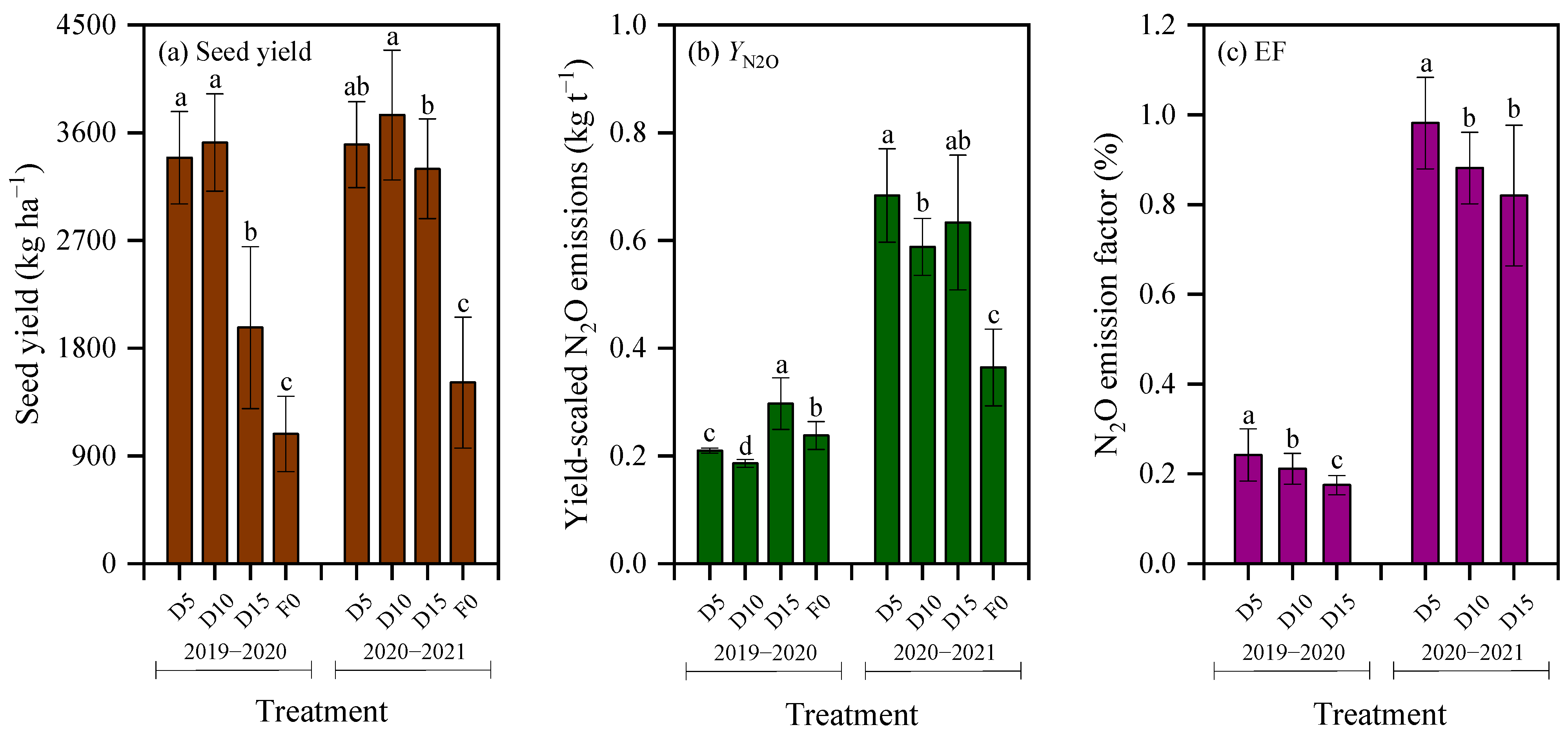

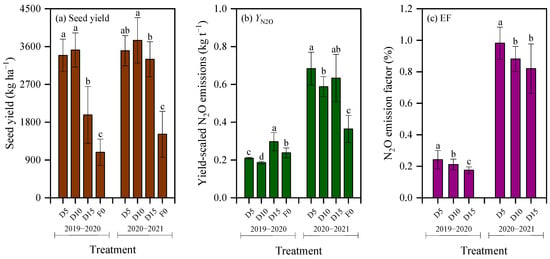

Seed yield under deep fertilization treatments produced yields 2.53 times greater than the F0 treatment (p < 0.01; Figure 7a). As reported previously [23], seed yield under the D5 and D10 treatments during the 2019–2020 season was 71.9% (Cohen’s d = 6.40) and 78.3% (Cohen’s d = 6.88) higher, respectively, compared with the D15 treatment (p < 0.01). In the 2020–2021 season, seed yield under the D10 treatment increased by 7.1% (Cohen’s d = 1.34) and 13.6% (Cohen’s d = 2.31) relative to the D5 and D15 treatments, respectively, and the difference was significant between D10 and D15 (p < 0.05).

Yield-scaled N2O emissions were significantly impacted by the growing season, which accounted for 84.42% of the total variance (Table 3). Yield-scaled N2O emissions in 2020–2021 were 2.52 times higher on average than those in 2019–2020 (Figure 7b). Yield-scaled N2O emissions in 2019–2020 followed the order D15 > F0 > D5 > D10, with obvious differences among treatments (p < 0.05; Figure 7b). Specifically, yield-scaled N2O emissions under the D10 treatment reduced by 11.4% and 37.4% relative to the D5 and D15 treatments, respectively. The effect size was large with Cohen’s d value of 9.61 between D10 and D5 treatments and of 8.05 between D10 and D15 treatments. Conversely, in 2020–2021, deep fertilization increased yield-scaled N2O emissions by 74.3% than the F0 treatment (p < 0.01). Within this season, the D10 treatment decreased yield-scaled N2O emissions by 13.9% and 7.1% relative to the D5 and D15 treatments, respectively, with corresponding Cohen’s d value of 3.30 and 1.17. The difference in yield-scaled N2O emissions was significant between D5 and D10 (p < 0.05; Figure 7b). Averaged over both seasons, yield-scaled N2O emissions under the D10 treatment reduced by 12.7% and 22.3%, relative to the D5 and D15 treatments, respectively.

The N2O emission factor in winter rapeseed fields ranged from 0.175% to 0.981% (Figure 7c), with both growing season and fertilization treatment significantly influencing this parameter (p < 0.01, Table 3). Notably, the growing season was the primary driver of variation, accounting for 98.80% of the total variance (Table 3); specifically, the N2O emission factor in 2020–2021 was 4.30-fold higher than that in 2019–2020. Among treatments, the D5 treatment consistently exhibited the highest N2O emission factor across both seasons. Compared to the D10 treatment, the N2O emission factor under the D5 treatment increased by 12.9% on average, with large effect sizes (Cohen’s d = 1.60 in 2019–2020 and 2.71 in 2020–2021). Relative to the D15 treatment, the N2O emission factor under the D5 treatment increased by an average of 29.0%, with large effect sizes (Cohen’s d = 3.81 in 2019–2020 and 3.03 in 2020–2021).

3.5. Net Ecosystem Economic Budget (NEEB)

The NEEB under different treatments across the two growing seasons of rapeseed are presented in Table 4. Deep fertilization significantly increased the NEEB (Table 3), with fertilized treatments averaging 2.75-fold higher than the F0 control. As fertilization depth increased, the NEEB first increased and then decreased, following the order: D10 > D5 > D15. Relative to the D5 and D15 treatments, the D10 treatment presented an increase in NEEB of 4.5% and 110.8% (Cohen’s d = 11.49) in the 2019–2020 season. In the 2020–2021 season, the increases were 8.5% and 16.6% (Cohen’s d = 3.26), respectively. The two-season average NEEB under D10 was 6.5% and 48.6% greater than that of D5 and D15 treatments, respectively.

Table 4.

Changes in net ecosystem economic budget as affected by deep fertilizer application.

4. Discussion

4.1. Characteristics of N2O Emissions in Rapeseed Fields

Soil N2O fluxes under different treatments exhibited a rapid decline during the initial stages of rapeseed growth, subsequently stabilizing at a low level (Figure 5). This temporal pattern aligns with prior observations [31], yet contrasts with findings by Tenuta et al. [22], who also examined gas fluxes in rapeseed cultivation systems. The reason for the observed flux dynamics in this study may be that peaks of N2O flux generally occur following fertilization and are often coincide with precipitation [11]. In this experiment, only basal fertilizer was applied, supplying an ample substrate for N2O generation during the early growth stage of rapeseed and providing sufficient nitrogen sources for soil nitrifying and denitrifying microbial communities. Furthermore, rainfall events (Figure 1) created favorable moisture conditions that enhanced nitrifying microbial activity, thereby contributing to the observed N2O flux peaks. As soil temperature decreased (Figure 1) and crop uptake of soil nutrients progressed, the availability of substrates for N2O production diminished, leading to a sustained reduction in N2O emissions. This trend is supported by the exponential increase in N2O flux with rising soil temperature (Figure 6), consistent with previous research [32]. Beyond 90 DAS, despite increases in soil temperature and moisture content (Figure 1)—conditions conducive to denitrification—the limited availability of substrates for N2O production resulted in persistently low flux levels. The discrepancies between the current findings and those of Tenuta et al. [22] may stem from differences in fertilizer type, fertilizer application methods, and climatic factors. These results further corroborate the pivotal role of fertilization in driving N2O production and emissions in agricultural soils by elevating soil inorganic nitrogen content [33]. Consequently, reducing basal fertilizer application rates and implementing top-dressing at various growth stages may effectively mitigate N2O emissions. As reported previously, a significant correlation linking N2O production rates to soil NO3−-N concentrations was proposed [34]. Unfortunately, soil inorganic nitrogen content across soil depths and temporal scales was not monitored to characterize soil fertility in this study, restricting the revelation of the seasonal variation characteristics of N2O flux. This represents a limitation of the present research and warrants further investigation in future studies.

Cumulative N2O emissions fluctuated between 0.26 and 0.71 kg ha−1 in the 2019–2020 season and between 0.55 and 2.39 kg ha−1 in the 2020–2021 season (Figure 5). These values are within the scope of prior studies [22,31]. Notably, cumulative N2O emissions were significantly elevated in the 2020–2021 season compared with 2019–2020. The difference is primarily attributed to the shift in preceding crops, meteorological conditions, and altered soil physical properties. The preceding crops differed between the two seasons, with rice (paddy field) and soybean (dry land) preceding the 2019–2020 and 2020–2021 seasons, respectively. Although the soil total N content was lower in 2020–2021 (Table 1), the preceding soybean residues—characterized by a low C:N ratio—likely promoted rapid mineralization, increasing the immediate availability of mineral nitrogen and dissolved organic carbon for nitrifiers and denitrifiers [35]. Additionally, precipitation in 2020–2021 was higher than in 2019–2020 (Figure 1), which facilitated greater N2O emissions from dryland soils. Conversely, in the 2019–2020 season, elevated soil moisture throughout most of the rapeseed growth period created anaerobic conditions, promoting the reduction of N2O to N2 and consequently reducing N2O emissions. It is important to note that our sampling frequency might have missed some short-term pulse fluxes typically triggered by heavy rainfall. Previous studies have shown that rain-induced pulses can contribute significantly to the cumulative emissions [11]. Due to the COVID-19 related lockdowns, our 8–17 days sampling interval may lead to an underestimation of the cumulative N2O emissions. However, all the treatments adopted the same sampling frequency, and the comparison results between the treatments remained reliable.

The N2O emission factor associated with winter rapeseed cultivation in this study ranged from 0.175% to 0.981% (Figure 7c), values that are lower than those documented by Merino et al. [31]. This discrepancy may be attributable to differences in rapeseed cultivars and geographic locations, both of which have been shown to significantly influence the N2O emission factor [36].

4.2. Responses of N2O Emissions from Rapeseed Fields to Fertilizer Placement Depth

Previous research has extensively examined the effects of fertilizer burial depths on rice [37], maize [38], rapeseed [23], and wheat [12]. These studies have consistently demonstrated that deep fertilization enhances crop yields. Optimal fertilization depths have been identified as 10 cm for rapeseed [23], 5 cm for rice [37], and 15 cm for maize [38]. Additionally, deep fertilization has been shown to mitigate nitrogen losses [39]. Specifically, Wu et al. [40] concluded that, relative to a 5 cm placement depth (D5), N2O and NH3 emissions from spring maize fields were significantly reduced by 5.6–61.0% and 26.9–56.0% when fertilizer was buried at 15 cm (D15) and 25 cm (D25), respectively. On a global scale, deep fertilizer application could potentially decrease N2O and NH3 emissions by 0.23 and 5.46 teragrams of nitrogen per year, respectively [40]. As an engineering approach, deep fertilizer placement enhances cost efficiency and fertilizer utilization in agricultural production and is widely adopted. Nevertheless, the dynamics of soil N2O emissions in winter rapeseed fields under deep fertilization remain insufficiently explored. Moreover, the optimal fertilization depth that simultaneously maximizes crop yield and minimizes N2O emissions has yet to be determined. Therefore, it is imperative to rigorously evaluate how deep fertilizer application influences N2O emissions in rapeseed fields. To better separate the treatment effects from environmental variability, a linear mixed-effects model (LMM) was employed in our study. The high conditional R2 values (0.86–0.99; Table 3) suggested that the LMM effectively partitioned the variance and provided a robust estimation of the depth effects across different seasons/sites.

Consistent with prior research [12,41], soil N2O emissions exhibited a progressively declining trend as fertilization depth increased in the current investigation (Figure 5). This phenomenon is primarily attributed to the physical and chemical mechanisms governing gas transport and transformation within the soil profile [11,42]. Previous studies revealed that N2O movement through the soil profile was influenced by SWC, soil temperature, and the soil’s physicochemical properties [11,43]. Deep-placed fertilizer relocates the site of N2O generation to deeper soil strata [44]. As hypothesized in previous research [11], the extended diffusion distance for N2O produced at greater soil depths increases its residence time in the soil, providing more opportunities for N2O to be further reduced to N2 by nitrous oxide reductase during its upward transport, thereby diminishing the surface N2O fluxes. While physical processes appear to be the dominant drivers in this study, the response of the microbial community provides important biological context. Soil N2O emissions arise chiefly through nitrification and denitrification, regulated by functional genes such as amoA (AOA and AOB) and nirK [45]. In this study, the richness and diversity of AOA, AOB, and nirK communities showed a numerical decline following the pattern D5 > D10 > D15 (p > 0.05; Figure 3). Similarly, increasing fertilization depth corresponded with a numerical reduction in the relative abundance of Nitrosospira and Nitrosomonas (Figure 4), which are key nitrifying bacteria involved in N2O production [46]. This downward trend of microbial communities, albeit non-significant, is consistent with the findings of Xu et al. [47], who reported that the abundances of Nitrosospira, AOA, and nirK genes are significantly and positively correlated with N2O emissions. This suggests that while the microbial population shifts in our study were subtle, they occurred in a direction that would theoretically favor reduced N2O production. Therefore, these slight biological changes, in conjunction with the dominant physical mitigation effects, collectively explain the observed decrease in N2O emissions under deep fertilization regimes. Furthermore, environmental conditions prevalent in the deep fertilizer band—such as high moisture and anaerobic microsites—may favor the activity of nosZ [48], which directly regulates the reduction of N2O to N2. Nevertheless, we did not quantify nosZ gene abundance in the current study. Future studies employing metagenomic approaches targeting nosZ clade I and II are needed to verify the specific biological contribution to this process.

Apart from the aforementioned physical and biological mechanisms, the reduction in surface N2O fluxes may also be regulated by the availability of nitrogen substrates in the reaction zone. It should be noted that nitrate leaching represents a significant competing pathway for nitrogen loss, particularly given the substantial precipitation (>500 mm) during the rapeseed growing season. Importantly, deeper fertilizer placement may theoretically increase the risk of nitrate leaching by positioning nitrogen closer to deeper soil horizons and potentially bypassing the dense surface root zone during early growth stages. While our study observed a reduction in soil N2O emissions with deeper fertilizer placement, this trend could be partially influenced by enhanced leaching rates at depth, which reduce the mineral nitrogen pool available for denitrification in the upper soil layers. During heavy rainfall periods (e.g., March–May), a portion of the mineral nitrogen might have leached into deeper soil layers beyond the measurement zone, thereby reducing the available substrate for denitrification and subsequent N2O production. Although the use of slow-release fertilizer in this experiment was intended to mitigate such risks by improving the synchrony between nitrogen supply and crop uptake, further research integrating both gaseous emissions and hydrological leaching is necessary to fully quantify the nitrogen mass balance in these systems.

This interplay between gaseous emissions and hydrological leaching ultimately shapes the overall soil nitrogen inventory. Soil nitrogen status further reflected the integrated impact of fertilization depth on nitrogen retention and loss. The potentially reduced nitrogen losses, attributed to the decreased ammonia volatilization and runoff under deep fertilization, likely contributed to the slightly greater STNC under D10 compared to D5 (p > 0.05; Figure 2b). Similar results were reported by Wu et al. [49], who found that localized nitrogen placement could maintain higher soil nitrogen stocks over time compared to surface broadcasting. Interestingly, the STNC of the D15 treatment was lower than that of the D5 and D10 treatments (Figure 2b). This might be because the D15 treatment induced root penetration, forming an efficient absorption network in the fertilized layer. The deep nitrogen was actively, efficiently, and continuously absorbed by the root system, and thus cannot be “retained” in large quantities in the soil.

The observed variations in N2O emissions and nitrogen status are fundamentally driven by the vertical heterogeneity of soil properties and microbial activities along the profile. Wu et al. [11] reported that shallower placement (D5 and D15) resulted in higher topsoil NO3−-N concentrations, whereas deeper placement (D25 and D35) shifted the mineral nitrogen pool to the 20–40 cm layer. Such vertical variations directly impacted N2O production and diffusion rates across the soil profile [11,17]. While our study captured the integrated surface N2O flux, the depth-specific physicochemical and microbial responses remain a ‘black box’ due to the lack of profile-scale measurements. Furthermore, although soil microbial communities are estimated to account for 41–68% of N2O variability [50], their localized activity around fertilizer ‘hotspots’ has rarely been assessed [11]. It should be noted that our 0–20 cm bulk sampling approach provided a representative assessment of the plow layer’s overall microbial potential; however, it might have diluted the intense, localized biological responses occurring immediately around the fertilizer bands at different depths. In this context, it must be recognized that surface N2O flux is the cumulative outcome of biological processes (nitrification and denitrification) occurring across diverse soil microsites. Consequently, the observed relationships between functional genes and N2O emissions in this study should be interpreted as a net ecosystem-level biological response to the physical placement of fertilizer, rather than a granular reflection of localized soil-microbe interactions at specific depths. To bridge this gap, future research should employ micro-scale sampling (e.g., at 2 cm intervals) and profile gas collection systems [51] to monitor N2O concentrations and microbial successions at multiple depths. Such granular insights, combined with measurements of soil nitrogen transformation rates [38], will be essential to fully unravel the mechanisms by which fertilization depth regulates N2O emissions.

4.3. Potential Implementation of Deep Fertilizer Placement Strategy for Rapeseed Production

Deep fertilizer placement markedly influenced rapeseed yield and fertilizer use efficiency, with the highest values observed under D10 [23]. As fertilization depth increased, a decline in soil N2O emissions was observed in the current study (Figure 5), suggesting that deep-band fertilizer application can mitigate nitrogen pollution in both ecosystems and the environment [11]. An integrated analysis of crop yield characteristics [23] and N2O emissions (Figure 5) across varying fertilization depths indicated that the D10 treatment exhibited the lowest yield-scaled N2O emissions (Figure 7b). When considering the fertilizer-induced N2O emissions, the D15 treatment had the minimum N2O emission factor, but it simultaneously had the lowest seed and oil yields of rapeseed [23]. Consequently, our results consistently identified the 10 cm depth as the optimal trade-off between crop productivity and N2O mitigation across the two growing seasons (Table 4), which are representative of the sandy loam soil in the Yangtze River basin. This recommendation aligns with previous studies in fine-textured soils [9], where subsurface placement effectively mitigates N losses by reducing surface ammonia volatilization and decoupling N availability from surface microbial hotspots. However, the applicability of these findings may be limited in coarse-textured sandy soils [52], where deeper placement could exacerbate nitrate leaching risks due to high hydraulic conductivity. Furthermore, under conditions of extreme waterlogging, the anaerobic zone might extend to the placement depth, potentially altering the N2O/(N2O + N2) product ratio [53]. Therefore, while the 10 cm placement is proposed as a ‘climate-smart’ management practice for rapeseed production in the Yangtze River basin, site-specific adjustments regarding soil texture and hydrological conditions remain necessary.

5. Conclusions

This study innovatively examined the impacts of fertilizer placement depths on soil N2O emissions in mechanized direct-seeded winter rapeseed fields. Fertilization practices obviously influenced soil N2O emissions and the functional genes associated with nitrifying and denitrifying microorganisms. Although soil N2O emissions with a fertilizer placement depth of 5 cm were on average higher than those of 10 cm, the difference was not statistically significant (p > 0.05). However, emissions with a fertilizer placement depth of 5 cm were significantly greater by 18.0% compared with those of 15 cm (p < 0.05). The fertilizer placement depth of 10 cm held the lowest yield-scaled N2O emissions. Compared with the fertilizer placement depths at 10 cm and 15 cm, the N2O emission factor with the fertilizer placement depth of 5 cm increased by 12.9% and 29.0%, respectively (p < 0.05), suggesting that deeper fertilizer placement effectively mitigates N2O emissions in rapeseed cultivation. Notably, a 10 cm fertilization depth exhibited the highest rapeseed yield while maintaining relatively low N2O emissions, thereby representing an environmentally sustainable fertilization approach. Future research should integrate high-resolution spatial sampling around fertilizer bands with profile gas and mineral nitrogen monitoring to unravel the micro-scale mechanisms of N2O dynamics. Additionally, simultaneous assessments of gaseous emissions and leaching losses across diverse soil types are required to establish a comprehensive nitrogen mass balance and develop refine, site-specific fertilization strategies for sustainable crop production.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.C., L.Z. and L.F.; Methodology, H.C.; Software, E.Z. and Y.H.; Validation, Y.H., Y.T., L.Z. and L.F.; Formal analysis, Y.H.; Investigation, Y.H., Y.T. and L.Z.; Data curation, E.Z.; Writing—original draft, H.C.; Writing—review & editing, E.Z., Y.H., Y.T., L.Z. and L.F.; Visualization, Y.T., L.Z. and L.F.; Supervision, E.Z., Y.T., L.Z. and L.F.; Funding acquisition, H.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Open Research Fund Program of State Key Laboratory of Eco-hydraulics in Northwest Arid Region, Xi’an University of Technology (2023KFKT-6), the Open Research Fund Program of the State Key Laboratory of Water Resources Engineering and Management (Wuhan University) (2023SWG07), the National Natural Science of China (52409072), and the Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2024NSFSC0980).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the first author or the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The Earth’s Energy Budget, Climate Feedbacks and Climate Sensitivity. In Climate Change 2021—The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 923–1054. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, N.; Jang, C.; Yang, W.H.; Guan, K.; DeLucia, E.H.; Lee, D. Spatial variability of agricultural soil carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide fluxes: Characterization and recommendations from spatially high-resolution, multi-year dataset. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 387, 109636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Yang, J.; Xu, R.; Lu, C.; Canadell, J.G.; Davidson, E.A.; Jackson, R.B.; Arneth, A.; Chang, J.; Ciais, P. Global soil nitrous oxide emissions since the preindustrial era estimated by an ensemble of terrestrial biosphere models: Magnitude, attribution, and uncertainty. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 640–659. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Bol, R.; Xia, L.; Xu, C.; Yuan, N.; Xu, X.; Wu, W.; Meng, F. Integrated farming optimization ensures high-yield crop production with decreased nitrogen leaching and improved soil fertility: The Findings from a 12-year experimental study. Field Crops Res. 2024, 318, 109572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muneer, M.A.; Afridi, M.S.; Saddique, M.A.B.; Chen, X.; Zaib-Un-Nisa; Yan, X.; Farooq, I.; Munir, M.Z.; Yang, W.; Ji, B.; et al. Nutrient stress signals: Elucidating morphological, physiological, and molecular responses of fruit trees to macronutrients deficiency and their management strategies. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 329, 112985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Reis Martins, M.; Ammann, C.; Boos, C.; Calanca, P.; Kiese, R.; Wolf, B.; Keel, S.G. Reducing N fertilization in the framework of the European farm to fork strategy under global change: Impacts on yields, N2O emissions and N leaching of temperate grasslands in the Alpine region. Agric. Syst. 2024, 219, 104036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, D.; Yan, J.; Zhu, J. Effect of a reduced fertilizer rate on the water quality of paddy fields and rice yields under fishpond effluent irrigation. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 231, 105999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Sun, H.; Liu, L.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Li, A.; Bai, Z.; Wang, G.; Liu, X.; Dong, H.; et al. Optimizing crop yields while minimizing environmental impact through deep placement of nitrogen fertilizer. J. Integr. Agric. 2025, 24, 36–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Liu, B.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Ren, T.; Cong, R.; Lu, J. Effect of depth of fertilizer banded-placement on growth, nutrient uptake and yield of oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.). Eur. J. Agron. 2015, 62, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Ahmad, S.; Liu, D.; Gao, S.; Wang, Y.; Tao, W.; Chen, L.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Li, G.; et al. Subsurface banding of blended controlled-release urea can optimize rice yields while minimizing yield-scaled greenhouse gas emissions. Crop J. 2023, 11, 914–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Chen, G.; Liu, F.; Cai, T.; Zhang, P.; Jia, Z. How does deep-band fertilizer placement reduce N2O emissions and increase maize yields? Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 322, 107672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, P.; Cai, T.; Jia, Z. Advantages of deep fertilizer placement in environmental footprints and net ecosystem economic benefits under the variation of precipitation year types from winter wheat fields. Field Crops Res. 2023, 303, 109142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, J.; He, R.; Hou, P.; Ding, C.; Ding, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, Z.; Tang, S.; Ding, C.; Chen, L.; et al. Combined controlled-released nitrogen fertilizers and deep placement effects of N leaching, rice yield and N recovery in machine-transplanted rice. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 265, 402–412. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Liao, Q.; Liao, Y. Response of area- and yield-scaled N2O emissions from croplands to deep fertilization: A meta-analysis of soil, climate, and management factors. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 4653–4661. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.Q.; Li, S.H.; Guo, L.G.; Cao, C.G.; Li, C.F.; Zhai, Z.B.; Zhou, J.Y.; Mei, Y.M.; Ke, H.J. Advantages of nitrogen fertilizer deep placement in greenhouse gas emissions and net ecosystem economic benefits from no-tillage paddy fields. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 263, 121322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Tan, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, P.; Mu, Y. Effect of fertilizer deep placement and nitrification inhibitor on N2O, NO, HONO, and NH3 emissions from a maize field in the North China Plain. Atmos. Environ. 2024, 334, 120684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rychel, V.; Meurer, K.H.E.; Ktterer, T. Deep N fertilizer placement mitigated N2O emissions in a Swedish field trial with cereals. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2020, 118, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT. FAO Statistics Division. 2024. Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/zh/#data/QC (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Xu, P.; Jiang, M.; Khan, I.; Shaaban, M.; Zhao, J.; Yang, T.; Hu, R. The effect of upland crop planting on field N2O emission from rice-growing seasons: A case study comparing rice-wheat and rice-rapeseed rotations. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 347, 108365. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, P.; Jiang, M.; Khan, I.; Zhou, M.; Shaaban, M.; Hu, R. Contrasting regulating effects of soil available nitrogen, carbon, and critical functional genes on soil N2O emissions between two rice-based rotations. Plant Soil 2023, 507, 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Gao, L.; Liao, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Xiao, W.; Wei, G.; Liao, Y. Effects of reduced and deep fertilizer on soil N2O emission and yield of winter rapeseed. Trans. CSAE 2020, 36, 80–87. [Google Scholar]

- Tenuta, M.; Gao, X.; Tiessen, K.H.D.; Baron, K.; Sparling, B. Placement and nitrogen source effects on N2O emissions for canola production in Manitoba. Agron. J. 2023, 115, 2369–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Gao, L.; Li, M.; Liao, Y.; Liao, Q. Fertilization depth effect on mechanized direct-seeded winter rapeseed yield and fertilizer use efficiency. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2023, 103, 2574–2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Shen, Y.; Kong, X.; Ge, B.; Sun, X.; Cao, M. Effects of diverse crop rotation sequences on rice growth, yield, and soil properties: A field study in Gewu Station. Plants 2024, 13, 3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; You, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Huang, H.; Ma, H.; He, Q.; Ming, A.; Huang, X. Soil microbial diversity and network complexity promote phosphorus transformation—A case of long-term mixed plantations of Eucalyptus and a nitrogen-fixing tree species. Biogeosciences 2025, 22, 4221–4239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkin, T.B.; Venterea, R.T. Chamber-based trace gas flux measurements. In Sampling Protocols; USDA-ARS: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; pp. 3-1–3-39. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, B.J.R.; Smith, K.A.; Flores, R.A.; Cardoso, A.S.; Oliveira, W.R.D.; Jantalia, C.P.; Boddey, R.M. Selection of the most suitable sampling time for static chambers for the estimation of daily mean N2O fluxes from soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2012, 46, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, D.; Yang, W.; Gao, M.; Gu, J.; Sun, H.; Kong, S.; Xu, H. Effects of pig manure compost application timing (spring/autumn) on N2O emissions and maize yields in Northeast China. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piikki, K.; Söderström, M.; Sommer, R.; Da Silva, M.; Munialo, S.; Abera, W. A boundary plane approach to map hotspots for achievable soil carbon sequestration and soil fertility improvement. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Fan, C.H.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Z.Z.; Sun, L.Y.; Xiong, Z.Q. Combined effects of nitrogen fertilization and biochar on the net global warming potential, greenhouse gas intensity and net ecosystem economic budget in intensive vegetable agriculture in southeastern China. Atmos. Environ. 2015, 100, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, P.; Artetxe, A.; Castellón, A.; Menéndez, S.; Aizpurua, A.; Estavillo, J.M. Warming potential of N2O emissions from rapeseed crop in Northern Spain. Soil Tillage Res. 2012, 123, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timilsina, A.; Oenema, O.; Luo, J.; Wang, Y.; Dong, W.; Pandey, B.; Bizimana, F.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, C.; Yadav, R.K.P.; et al. Plants are a natural source of nitrous oxide even in field conditions as explained by 15N site preference. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 805, 150262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trost, B.; Prochnow, A.; Meyer-Aurich, A.; Drastig, K.; Baumecker, M.; Ellmer, F. Effects of irrigation and nitrogen fertilization on the greenhouse gas emissions of a cropping system on a sandy soil in northeast Germany. Eur. J. Agron. 2016, 81, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, P.; Zhou, J.; Feng, L.; Jansen-Willems, A.B.; Xiong, Z. Pathways and controls of N2O production in greenhouse vegetable production soils. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2019, 55, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazula, M.J.; Lauer, J.G. Nitrous emission from arable soils in Germany—An evaluation of six long-term field experiments. J. Environ. Qual. 2023, 52, 1080–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, E.A.; Ruser, R. Nitrous Oxide Emissions from Arable Soils in Germany—An Evaluation of Six Long-Term Field Experiments. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2000, 163, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, P.; Yuan, W.; Li, G.; Petropoulos, E.; Xue, L.; Feng, Y.; Xue, L.; Yang, L.; Ding, Y. Deep fertilization with controlled release fertilizer for higher cereal yield and N utilization in paddies: The optimal fertilization depth. Agron. J. 2021, 113, 5027–5039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Ren, L.; Wang, J.; Liu, F.; Liu, G.; Li, H.; Zhang, P.; Jia, Z. Optimizing fertilization depth can promote sustainable development of dryland agriculture in the Loess Plateau region of China by improving crop production and reducing gas emissions. Plant Soil 2024, 499, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.M.M.; Gaihre, Y.K.; Islam, M.R.; Ahmed, M.N.; Akter, M.; Singh, U.; Sander, B.O. Mitigating greenhouse gas emissions from irrigated rice cultivation through improved fertilizer and water management. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 307, 114520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Wu, Q.; Huang, H.; Xie, L.; An, H.; Zhao, X.; Wang, F.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, R.; Bangura, K.; et al. Global meta-analysis and three-year field experiment shows that deep placement of fertilizer can enhance crop productivity and decrease gaseous nitrogen losses. Field Crops Res. 2024, 307, 109263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Pang, S.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Ma, R.; Lin, X.; Wang, D. Nitrogen losses trade-offs through layered fertilization to improve nitrogen nutrition status and net economic benefit in wheat-maize rotation system. Field Crops Res. 2024, 312, 109406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Rajendran, N.; Tenuta, M.; Dunmola, A.; Burton, D.L. Greenhouse gas accumulation in the soil profile is not always related to surface emissions in a prairie pothole agricultural landscape. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2014, 78, 805–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido-Moncada, M.; Petersen, S.O.; Clough, T.J.; Munkholm, L.J.; Squartini, A.; Longo, M.; Dal Ferro, N.; Morari, F. Soil pore network effects on the fate of nitrous oxide as influenced by soil compaction, depth and water potential. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2024, 197, 109536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoeven, E.; Decock, C.; Barthel, M.; Bertora, C.; Sacco, D.; Romani, M.; Sleutel, S.; Six, J. Nitrification and coupled nitrification-denitrification at shallow depths are responsible for early season N2O emissions under alternate wetting and drying management in an Italian rice paddy system. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 120, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, R.; Li, J.; Hu, B.; Chu, G. Mitigating N2O emission by synthetic inhibitors mixed with urea and cattle manure application via inhibiting ammonia-oxidizing bacteria, but not archaea, in a calcareous soil. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 273, 116478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Ling, Y.; Wang, H.; Chu, Z.; Yan, G.; Li, Z.; Wu, T. N2O emission in partial nitritation-anammox process. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2020, 31, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Ran, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Pan, H.; Guan, X.; Li, J.; Shi, J.; Dong, L.; et al. Warmer and drier conditions alter the nitrifier and denitrifier communities and reduce N2O emissions in fertilized vegetable soils. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 231, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keiluweit, M.; Nico, P.S.; Kleber, M.; Fendorf, S. Anaerobic microsites have an unaccounted role in soil carbon stabilization. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Huang, H.; Wang, Q.H.; Liu, Z.Y.; Pei, R.Z.; Wen, G.S.; Feng, J.H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, P.; Gao, Z.Q.; et al. Deep fertilization is more beneficial than enhanced efficiency fertilizer on crop productivity and environmental cost: Evidence from a global meta-analysis. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domeignoz-Horta, L.A.; Philippot, L.; Peyrard, C.; Bru, D.; Breuil, M.C.; Bizouard, F.; Justes, E.; Mary, B.; Léonard, J.; Spor, A. Peaks of in situ N2O emissions are influenced by N2O-producing and reducing microbial communities across arable soils. Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 24, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, P.; Ye, X.; Wei, L.; Li, S. Interactions between maize plants and nitrogen impact on soil profile dynamics and surface uptake of methane on a dryland farm. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 324, 107716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulpreet, S.; Eajaz, D.; Satinderpal, S.; Akash, S.; Lakesh, S.; Hardeep, S. Subsurface banding increases ammonia emissions under rainfed cotton in Florida sandy soils. Front. Agron. 2025, 7, 1625163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, W.; Gao, X.; Tenuta, M.; Gui, D.; Zeng, F. Relationship between soil profile accumulation and surface emission of N2O: Effects of soil moisture and fertilizer nitrogen. Biol. Fert. Soils 2019, 55, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.