Abstract

Nitrogen plays a critical role in regulating rice growth and stress resistance, yet its influence on heat tolerance at the seedling stage remains poorly understood. To clarify the physiological mechanisms involved, this study subjected rice seedlings to a transient range of temperature treatments (30, 35, 40, and 45 °C) under varying nitrogen levels. We systematically evaluated plant growth and analyzed key metabolic responses related to carbohydrates, phytohormones, and reactive oxygen species (ROS). The results demonstrated that temperatures of 40 °C and 45 °C significantly suppressed seedling growth, while elevated nitrogen supply effectively mitigated heat-induced damage, as evidenced by reduced leaf wilting and higher chlorophyll retention. Under high-temperature stress, seedlings receiving high nitrogen maintained superior carbohydrate reserves, higher levels of hormones such as zeatin ribosides, indole-3-acetic acid, and gibberellins, as well as a greater activity of key nitrogen metabolism enzymes compared to those under low nitrogen. Furthermore, high nitrogen enhanced the activity of antioxidant enzymes (superoxide dismutase and catalase) and significantly lowered the accumulation of malondialdehyde and hydrogen peroxide. Collectively, these findings indicate that appropriate nitrogen application enhances heat tolerance in rice seedlings through an integrated regulation of carbohydrate and hormone metabolism coupled with strengthened antioxidant capacity and improved ROS homeostasis.

1. Introduction

Rice, as one of the three major staple crops globally, plays a vital role in worldwide and regional food security systems [1,2]. Its stable production is directly linked to the food supply for billions of people. With only about 7% of the arable land around the world, China successfully feeds nearly 22% of the global population [3]. In developing countries across Asia and Africa, rice serves as a core crop for maintaining food supply and livelihood stability, where yield fluctuations directly affect local food security [4,5,6]. However, with ongoing socioeconomic development and continuous population growth, the global demand for higher rice yield per unit area is becoming increasingly urgent. It is projected that by the mid-21st century, global total food production must double to meet rising consumption demands [7,8]. Although hybrid rice technology has significantly enhanced the yield potential of rice, increasingly frequent extreme high-temperature events are severely constraining further yield improvements [9,10].

Heat stress has become one of the major abiotic threats to global agricultural production. In 2022, severe drought combined with extreme heat in Yangtze River Basin of China significantly reduced the seed setting rate of rice, leading to substantial yield losses [11,12,13]. Similarly, in 2025, extreme temperatures approaching 50 °C occurred in northern India, while countries in southeast Asia such as Thailand and Cambodia also experienced temperatures exceeding 44 °C. These conditions not only reduced rice yields but also notably deteriorated grain quality [14,15]. Concurrently, the duration of summer heat in south and west Asia has extended by 10–15 days compared to the normal range [16]. More critically, the frequency of extreme heat events continues to rise. For instance, in southern China, the recurrence interval of heat damage to rice has shortened from once per decade to once every few years [17]. Therefore, developing and promoting cultivation techniques for mitigating heat-related disasters in rice has become an urgent priority for safeguarding food security.

Numerous studies have confirmed that under high-temperature stress, thermolabile enzymes in rice are inactivated, reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulate excessively and induce programmed cell death (PCD) [18,19], while the photosynthetic process is inhibited, leading to a substantial accumulation of reduced electron acceptors [20]. When the ambient temperature exceeds the optimum by 5 °C or more, the integrity of plant organelles, cytoskeleton, and cell membranes is impaired, thereby activating an adaptive defense mechanism centered on ROS scavenging. This defense system consists of non-enzymatic antioxidants (such as carotenoids and anthocyanins) and enzymatic antioxidant components including catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), peroxidase (POD), etc. [21,22]. As critical osmoprotectants, proline and soluble sugars are integral to the plant non-enzymatic antioxidant system. Under abiotic stresses such as high temperature and drought, they not only serve as key osmoregulatory substances to maintain cellular homeostasis but also synergistically regulate ROS homeostasis through direct or indirect pathways [23,24]. Specifically, proline and soluble sugars can directly scavenge ROS such as hydroxyl radicals and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), while stabilizing cell membrane and organelle structures, thereby reducing excessive ROS generation at the source. Moreover, proline participates in stress signal transduction and can upregulate the activity of antioxidant enzymes such as SOD and CAT [25], while soluble sugars can enhance the function of the antioxidant system through related signaling pathways [26]. Together, they form an efficient antioxidant network in plants. To counteract the adverse impacts of extreme heat on rice yield, researchers have performed comprehensive studies on the physiological response mechanisms to high-temperature stress and practical mitigation techniques, thereby achieving substantial progress in this field. For instance, Guo et al. [27] identified key high-temperature tolerance genes that have been widely applied in rice stress-resistant breeding. The exogenous application of chemical regulators such as acid invertase [28], salicylic acid (SA) [29], abscisic acid (ABA) [30], and acetic acid [31] can effectively alleviate high-temperature-induced damage to rice spikelet development. Although significant progress has been made, the problem of yield loss due to extreme heat has not been fundamentally resolved, owing to considerable climatic variations across rice-growing regions, the limited adaptability of single prevention strategies, and the suddenness and unpredictability of heat stress events. Therefore, in-depth investigations into the mechanisms underlying high-temperature tolerance, coupled with the development and optimization of protective cultivation practices, remain a key priority for future research on rice stress resistance.

Nitrogen is an indispensable element for rice growth and development, synergistically enhancing yield, improving grain quality, and increasing stress resistance [32]. In yield formation, nitrogen determines the final productivity by regulating photosynthetic efficiency and dry matter accumulation [33]. Regarding grain quality, balanced nitrogen supply optimizes internal nutrient composition and starch granule properties, thereby ensuring favorable cooking, eating, and appearance traits [34]. Furthermore, appropriate nitrogen application improves plant vigor and enhances tolerance to abiotic stresses. Previous studies indicate that nitrogen influences crop responses to high-temperature stress. For instance, in maize, adequate nitrogen increases photosynthetic capacity and nitrogen assimilation efficiency under heat stress, particularly in heat-sensitive hybrids [35]. In rice, combined nitrogen application alleviates the adverse effects of high temperature during flowering by improving photosynthetic performance and antioxidant activity [36]. High nitrogen levels can also mitigate yield losses in super hybrid rice under heat stress by reducing spikelet degeneration [37]. Collectively, the regulatory role of nitrogen in plant thermotolerance varies depending on the crop species, temperature regimes, growth stages, and nitrogen levels. Currently, most studies have focused on the individual effects of nitrogen deficiency, nitrogen excess, or high-temperature stress on rice growth and physiology. However, research on the interactive effects of nitrogen and high temperature on physiological processes, such as growth, carbohydrate metabolism, and stress adaptation pathways, remains limited. To elucidate the physiological mechanisms underlying nitrogen-mediated heat tolerance in rice, this study implemented four nitrogen levels and four transient temperature treatments. We measured the chlorophyll content, contents of malondialdehyde (MDA), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and proline, activities of antioxidant enzyme and nitrogen metabolism enzyme activities, and contents of carbohydrates and phytohormones in rice leaves across all treatment combinations. There were two specific objectives: (1) to examine the effects of different nitrogen and temperature treatments on rice growth; and (2) to clarify the physiological mechanisms of nitrogen–temperature interactions in regulating heat responses by analyzing changes in carbohydrate metabolism, nitrogen metabolism enzyme activities, hormone status, and antioxidant responses.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

This study was conducted at the experimental station of the China National Rice Research Institute, Hangzhou, China. Yangdao 6 (Indica rice) was selected due to its comprehensive excellent performance in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River. Prior to sowing, seeds were soaked for 48 h at room temperature of approximately 25 °C and subsequently germinated for 24 h at 30 °C. Twenty to twenty-five seeds were sown per pot (30 cm height, 15 cm radius) and maintained in a greenhouse with a controlled temperature of 23/28 °C (day/night), a relative humidity of 70% and natural sunlight. At the 3–4 leaf stage, seedlings were thinned to six plants per pot with six biological replicates (six pots per treatment). Each pot received 2.5 g calcium superphosphate and 0.4 g potassium chloride as basal fertilizer.

2.2. Experimental Design

Four N application levels were established: 0 g (zero nitrogen, 0N), 0.1 g (low nitrogen, LN), 0.2 g (medium nitrogen, MN), and 0.3 g (high nitrogen, HN) per pot. Nitrogen was supplied as urea at the 3–4 leaf stage. Approximately two weeks later, after rice plants had adapted to the fertilizer and exhibited stable growth, they were transferred to individual artificial climate chambers for different high-temperature stress treatments. To elicit valid high-temperature stress responses, the chamber was maintained at constant temperatures of 30 °C, 35 °C, 40 °C, and 45 °C (relative humidity of 70%) for approximately 48 h. Specifically, 30 °C was designated as the normal-temperature control, and the selection of the other high-temperature gradients was grounded in our prior research [30] and preliminary experimental results. Plant samples were collected immediately post-temperature treatment.

2.3. Measurement of Rice Growth Index

Four clumps of rice plants were randomly selected for each treatment, and plant height was measured by a tape. Each plant was then separated, had their wilted or desiccated tissues removed, and put in a paper envelope. They were further oven-dried at 105 °C for 30 min to deactivate enzymes, which was followed by drying for approximately 48 h to constant weight at 75 °C. Additionally, phenotypic images were captured exclusively for seedlings subjected to the 45 °C heat stress treatment for 48 h.

2.4. Measurement of Carbohydrates Content

For carbohydrate analysis, 0.1 g of dry sample (passed through a 100-mesh sieve) from the youngest fully expanded leaves was weighed. The sample was added to 10 mL of 80% ethanol and incubated in an 80 °C water bath for 30 min. After cooling, the solution was centrifuged at 2000× g for 20 min. The supernatant was collected by filtration, and the residue was re-extracted twice identically. Finally, the supernatants were combined and the volume was adjusted to 30 mL in total. We added 10 mg of activated carbon to the supernatant and incubated it for 30 min for decolorization. Subsequently, a combination of 1 mL of the sample extract, 0.5 mL of an anthrone–ethyl acetate reagent, and 5 mL of concentrated sulfuric acid was added, which was followed by a 15-min water bath at 90 °C. The absorbance values at 620 nm of the compound were calculated after cooling. The total soluble sugar and starch contents were determined using a standard curve of sucrose [38]. Sucrose, glucose, and fructose were extracted using the same protocol as that for total soluble sugar extraction, while their concentrations were quantified following a slightly modified method described by Zhang [39]. The total non-structural carbohydrate (NSC) content was calculated as the sum of soluble sugar and starch contents.

2.5. Determination of Chlorophyll Content

For chlorophyll analysis, 1 g of fresh sample from the youngest fully expanded leaves was weighed. Leaves were cut into small pieces and mixed thoroughly, and an appropriate amount was weighed. Chlorophyll was extracted with 10 mL of 95% ethanol, and the mixture was stored in the dark until the leaves were completely decolorized. The extract absorbance was measured at 649 nm and 665 nm using a spectrophotometer (UV-4802, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) [40].

2.6. Nitrogen Metabolism Related Enzyme Activity Determination

Fresh leaves were washed with distilled water, drained, and cut into pieces. A 0.5 g leaf sample was weighed, and then 1 mL of 0.1 mol·L−1 phosphate buffer solution and 1 mL of 0.2 mol·L−1 potassium nitrate (KNO3) solution were added. The mixture was reacted at 37 °C in the dark for 1 h. Subsequently, 0.4 mL of 30% trichloroacetic acid was added and thoroughly mixed. Then, 1 mL aliquot of the reaction solution was taken, and 2 mL of 1% sulfanilamide solution and 2 mL of 0.2% α-naphthylamine solution were added sequentially, which was followed by a fully proceeded color reaction for 30 min. The activity of nitrate reductase (NR) activity was measured via the in vitro method [41]. Activity was expressed as µg NO2−·mg−1 protein·h−1. For glutamate synthase (GS) and glutamine oxoglutarate aminotransferase (GOGAT) activity, 0.5 g leaf was placed in a pre-cooled mortar and ground to a fine powder with sterile quartz sand. The extraction buffer contained 100 mmol·L−1 Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 1 mmol·L−1 MgCl2, 1 mmol·L−1 EDTA, and 10 mmol·L−1 2-mercaptoethanol. Homogenate was centrifuged at 13,000× g for 25 min, and then the supernatant was used for enzyme activity determination [42].

2.7. Antioxidant Enzyme Activity Measurement

A 0.2 g leaf tissue sample was weighed into a mortar, mixed with 5 mL 50 mmol·L−1 phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), and ground in an ice bath. The homogenate was transferred to a centrifuge tube and centrifuged at 10,000× g at 4 °C for 15 min. The supernatant (enzyme extract) was collected into a tube and stored at 0–4 °C. The SOD activity was measured via nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) photochemical reduction [43], while the activities of POD and CAT were measured with reference to the method of Maehly and Chance [44].

2.8. Malondialdehyde and Hydrogen Peroxide Determination

For MDA determination, 1 g rice leaf was ground with 10 mL 10% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and centrifuged at 4000× g for 10 min, after which the supernatant was retained. The MDA content was estimated using thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) [45]. For H2O2 determination, 0.2 g leaf sample was homogenized in 5 mL 10 mM 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole. After centrifugation at 10,000× g for 10 min, 2 mL of supernatant was taken, and 1 mL 0.1% titanium tetrachloride in 20% H2SO4 was added. The reaction mixture was centrifuged to remove insolubles. The absorbance was measured at 410 nm, and the H2O2 concentration was calculated by using a standard curve [46].

2.9. Proline Content Determination

Proline was measured with reference to the method of Nguyen et al. [47], and 0.5 g of fresh sample from the youngest fully expanded leaves was weighed. The sample was homogenized in 10 mL of 3% aqueous sulfosalicylic acid solution, which was followed by centrifugation at 3000 rpm. The supernatant was collected by filtration, after which a 2 mL aliquot of the supernatant was mixed thoroughly with 2 mL of acid ninhydrin reagent and 2 mL of glacial acetic acid. The mixture was incubated in a boiling water bath at 100 °C for 1 h. After cooling, 2 mL of toluene was added to extract the chromophore with toluene as the blank control. The extract absorbance was measured at 520 nm using a spectrophotometer (UV-4802, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan).

2.10. Phytohormones Content Determination

Phytohormone contents [indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), ABA, zeatin ribosides (ZRs), gibberellins (GAs)] were determined using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (China Agricultural University, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocols.

2.11. Statistical Analyses

An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was executed in the SPSS 20.0 statistical package (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). At least three experimental replicates were performed to ensure that the mean values and standard errors presented in the figures represent reliable data. Multiple comparison analysis was performed to determine the significance of differences under nitrogen or temperature treatments. Two-way ANOVA was used to analyze the main effects of nitrogen levels, temperature treatments and their interaction effects. Replicates were assigned as random effects, with temperature, nitrogen supply levels, and their interactive effects defined as fixed effects. Comparisons of the mean values were accomplished by the least significant difference (LSD) test at the 0.05 probability threshold.

3. Results

3.1. Nitrogen Supply Alleviates Heat Stress-Caused Damages in Rice Seedling Plants

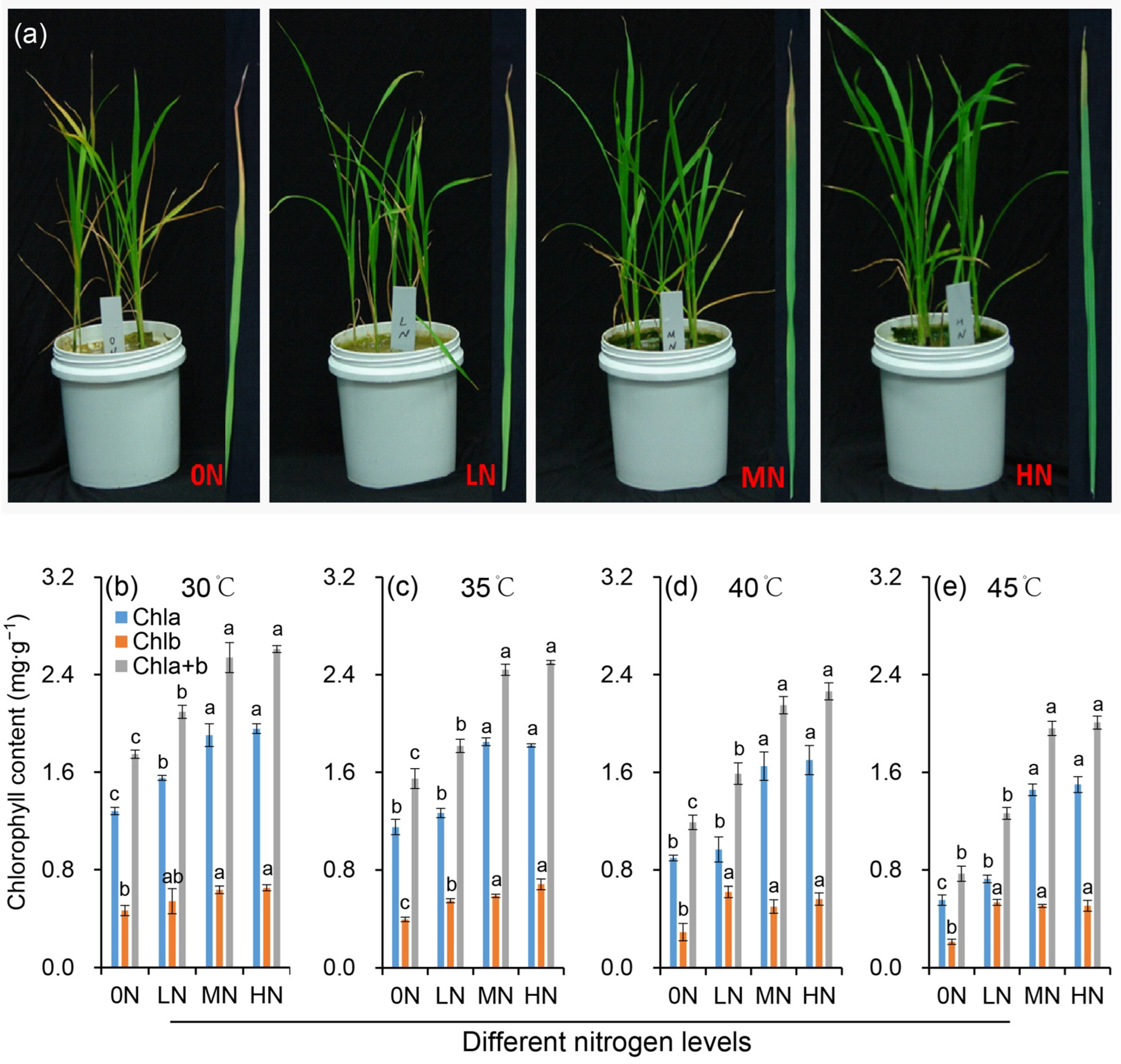

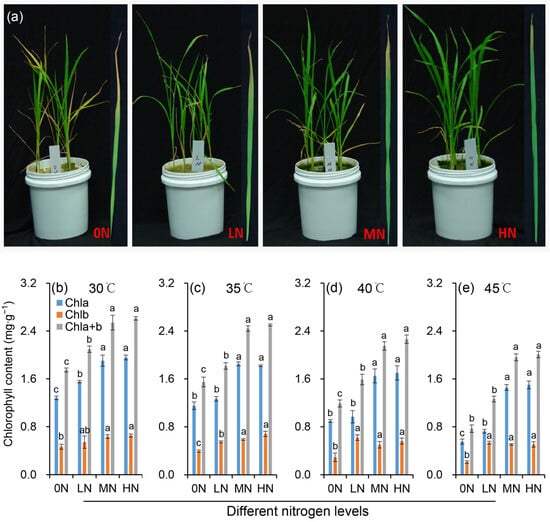

Compared to the constant 30 °C control, exposure to 35 °C did not significantly affect rice plant growth. However, growth was markedly impaired under heat stress of 40 °C (Figure 1a). Rice seedlings under 0N treatment exhibited typical symptoms of mineral nutrient deficiency, including young leaf chlorosis and growth retardation (Figure 1a), which aligns with the pivotal role of nitrogen in mediating plant nutrient homeostasis and morphogenetic processes. Moreover, they exhibited the greatest susceptibility to heat stress, as evidenced by pronounced leaf yellowing and senescence. Enhanced nitrogen supplies effectively mitigated heat stress damage. Specifically, under high temperatures, 0N plants lost turgor and prematurely failed to sustain normal growth, resulting in poor overall performance. In the LN treatment, significant leaf yellowing occurred due to reduced chlorophyll content. In contrast, plants receiving MN or HN treatments maintained light green coloration in nearly all leaves.

Figure 1.

Plant morphology (a) and chlorophyll contents (b–e) of rice plants under different nitrogen conditions when subjected to heat stress. Rice seedlings were subjected to the high temperature of 45 °C for 48 h, after which we captured phenotypic images. 0N, LN, MN and HN denote zero nitrogen, low nitrogen, medium nitrogen, and high nitrogen. Vertical bars denote ± standard deviations (n = 3). Different lowercase letters denote significant differences for the same index within the same temperature among different nitrogen treatments with a least significant difference (LSD) test at p ≤ 0.05.

Under normal temperature (30 °C), the chlorophyll content varied significantly with nitrogen level, showing an overall increase as the nitrogen supply rose. However, the difference between HN and MN treatments was not significant (Figure 1b–e). Heat stress induced a significant decrease in chlorophyll a content with the magnitude of reduction escalating at higher temperatures. This heat-induced decline in chlorophyll a was progressively alleviated with increasing nitrogen levels. The response patterns of chlorophyll b and chlorophyll (a+b) content to heat stress and nitrogen were consistent with those of chlorophyll a.

3.2. Nitrogen Application Affects the Dry Matter Consumption of Rice Seedlings Under Heat Stress

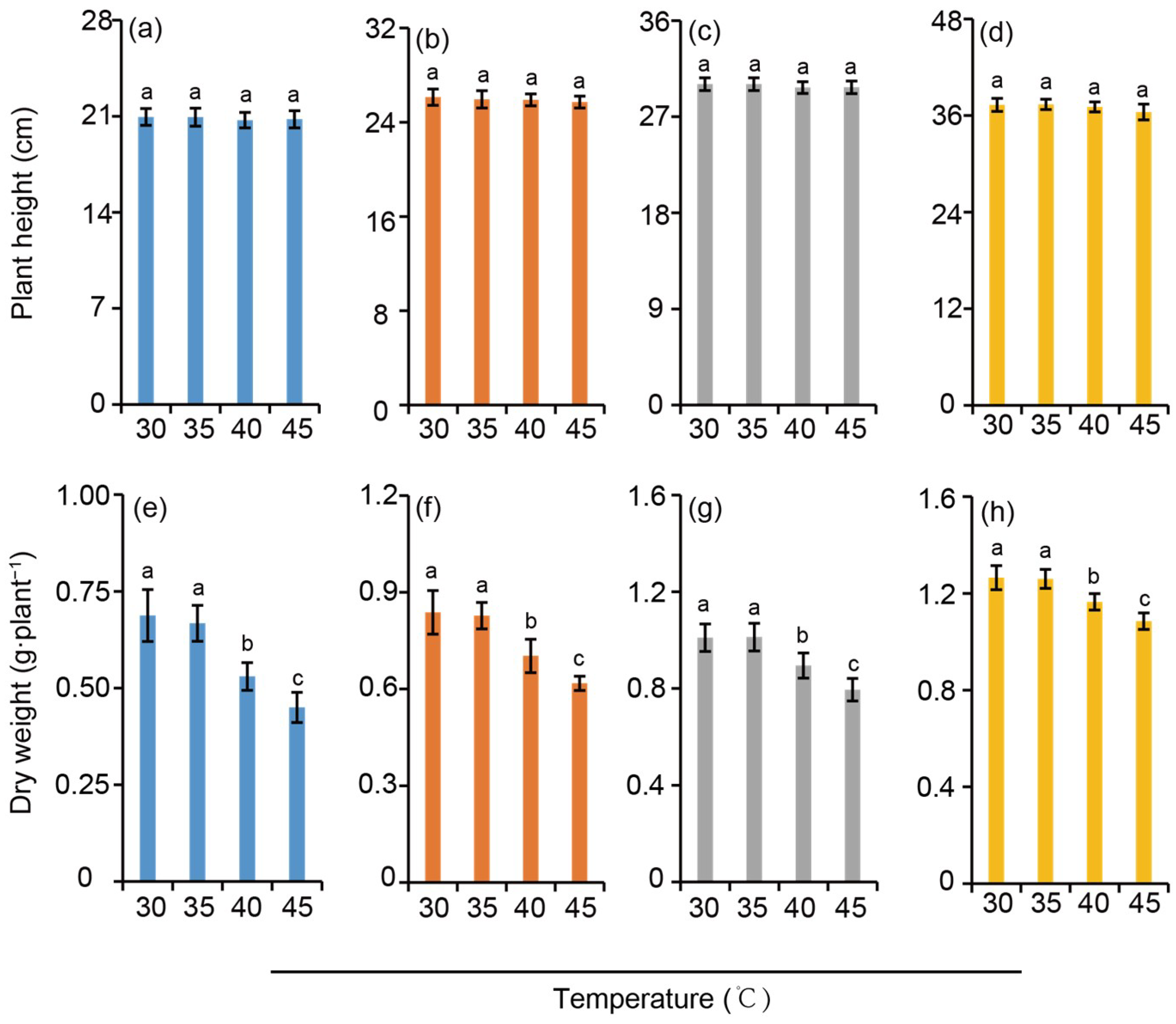

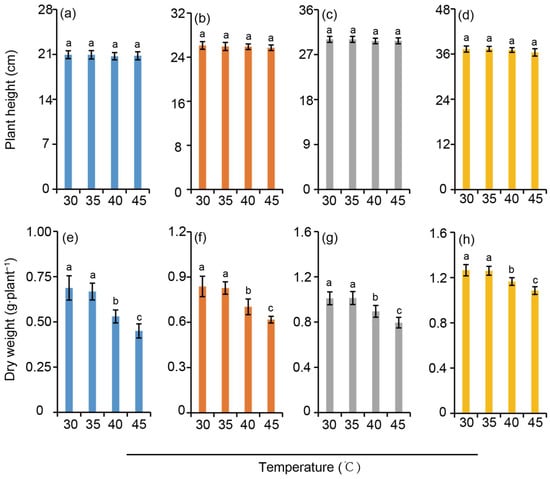

The plant height of rice seedlings increased with the rise of nitrogen level, showing a trend of HN > MN > LN > 0N. However, at the same nitrogen application level, the effect of temperature on rice plant height appeared to be not significant (Figure 2a–d). Similarly, the above-ground dry matter weight of rice increased with the elevation of nitrogen application levels. Compared with the 30 °C treatment, there was no significant difference in the above-ground dry weight of rice under the 35 °C treatment. In contrast, the above-ground dry weight decreased significantly under the high-temperature stress treatments of 40 °C and 45 °C with a greater reduction observed at the latter temperature. When comparing different nitrogen levels, the reduction amplitude of rice dry weight induced by high-temperature stress under the HN treatment displayed a significantly smaller reduction when compared to those under other nitrogen gradients, owing to its sufficient accumulation of organic matter in the early growth stage (Figure 2e–h). This result indirectly verifies that nitrogen supply can effectively alleviate the adverse effects of heat stress on dry matter accumulation in rice.

Figure 2.

Plant height (a–d) and above-ground dry weight (e–h) under different nitrogen conditions when subjected to heat stress. 0N, LN, MN and HN denote zero nitrogen, low nitrogen, medium nitrogen, and high nitrogen. Vertical bars denote ± standard deviations (n = 4). Different lowercase letters denote significant differences for the same nitrogen level among different temperature treatments with a least significant difference (LSD) test at p ≤ 0.05.

3.3. Nitrogen Influences Contents of MDA, H2O2 and Proline in Rice Seedling Plants Under Heat Stress

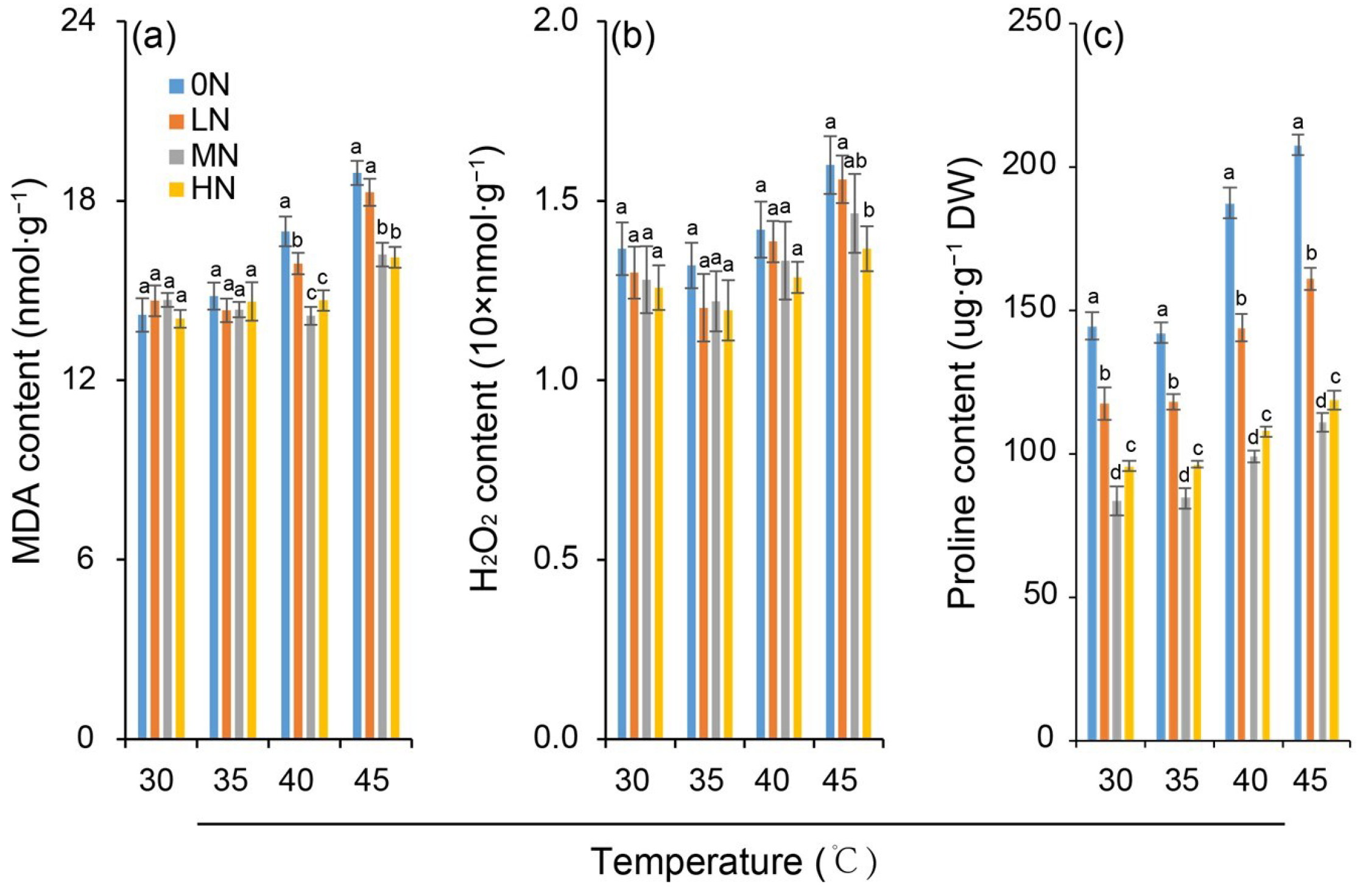

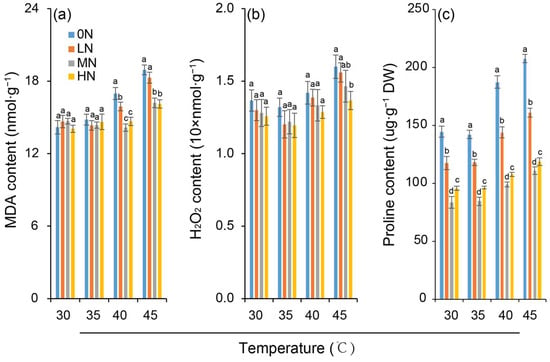

Leaf MDA and H2O2 contents did not differ significantly among nitrogen levels under the 30 °C control (Figure 3a,b). However, both were significantly influenced by high-temperature treatments. At 35 °C, the MDA and H2O2 contents remained comparable to the control, indicating no induction of lipid peroxidation damage to leaf cell membranes. However, both the MDA and H2O2 contents were significantly elevated subjected to heat stress of 40 °C and 45 °C at all nitrogen levels. The increase was greater at 45 °C than at 40 °C, suggesting intensified lipid peroxidation damage as the temperature increased. Crucially, under the same high-temperature stress, the extent of heat-induced peroxidation damage decreased with increasing nitrogen level, as reflected by progressively smaller increments in MDA and H2O2 contents.

Figure 3.

Variation in contents of malondialdehyde (MDA) (a), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (b) and proline (c) in rice plants under different nitrogen conditions when subjected to heat stress. 0N, LN, MN and HN denote zero nitrogen, low nitrogen, medium nitrogen, and high nitrogen. Vertical bars denote ± standard deviations (n = 3). Different lowercase letters denote significant differences for the same temperature among different nitrogen treatments with a least significant difference (LSD) test at p ≤ 0.05.

Under different nitrogen levels, the proline content in rice leaves varied (Figure 3c). At the same temperature, the proline content was the lowest under MN treatment, followed by HN, while it was relatively high under LN and 0N. At the same nitrogen level, the proline content in rice leaves increased with increasing temperature (30–45 °C). However, the temperature-induced increase in proline content under 40 °C and 45 °C was greater under 0N and LN treatments but smaller under MN and HN treatments.

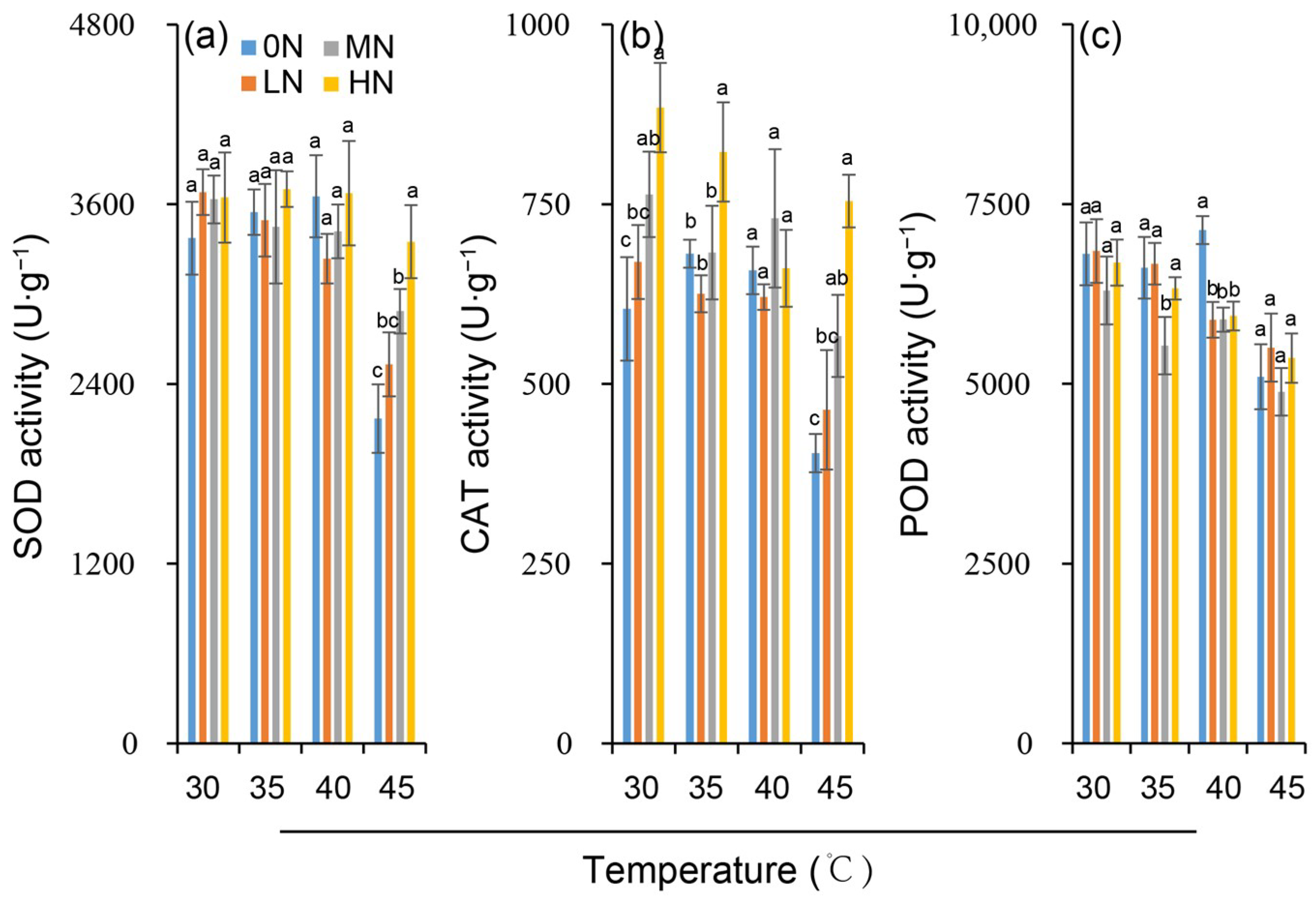

3.4. Heat Stress-Induced Oxidative Stress Is Alleviated by Nitrogen Supplementation Through Enhancing Antioxidant Capacity

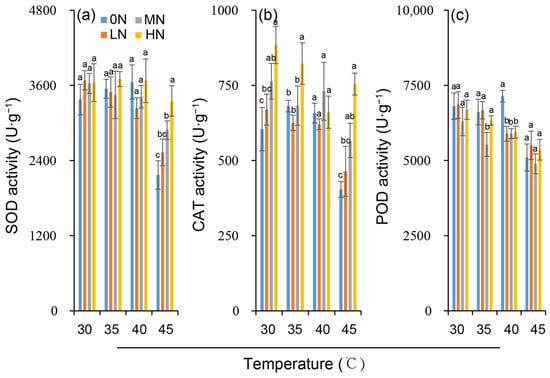

The activities of key antioxidant enzymes, SOD and POD, showed no significant variation across nitrogen levels under control temperature conditions of 30 °C. CAT activity, however, increased slightly with increasing nitrogen (Figure 4a–c). Exposure to 35 °C did not significantly alter SOD, POD, or CAT activities at any nitrogen level. In contrast, 40 °C and 45 °C treatments significantly decreased leaf the SOD, POD, and CAT activities with the degree of suppression dependent on both temperature and nitrogen level. At a given nitrogen level, the decrease in antioxidant enzyme activity was greater under 45 °C than under 40 °C. Notably, the heat-induced reduction in antioxidant enzyme activity was significantly slighter in the MN and HN treatments than in the 0N and LN treatments (Figure 4a–c).

Figure 4.

Variation in enzyme activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD) (a), catalase (CAT) (b) and peroxidase (POD) (c) in rice plants under different nitrogen conditions when subjected to heat stress. 0N, LN, MN and HN denote zero nitrogen, low nitrogen, medium nitrogen, and high nitrogen. Vertical bars denote ± standard deviations (n = 3). Different lowercase letters denote significant differences for the same temperature among different nitrogen treatments with a least significant difference (LSD) test at p ≤ 0.05.

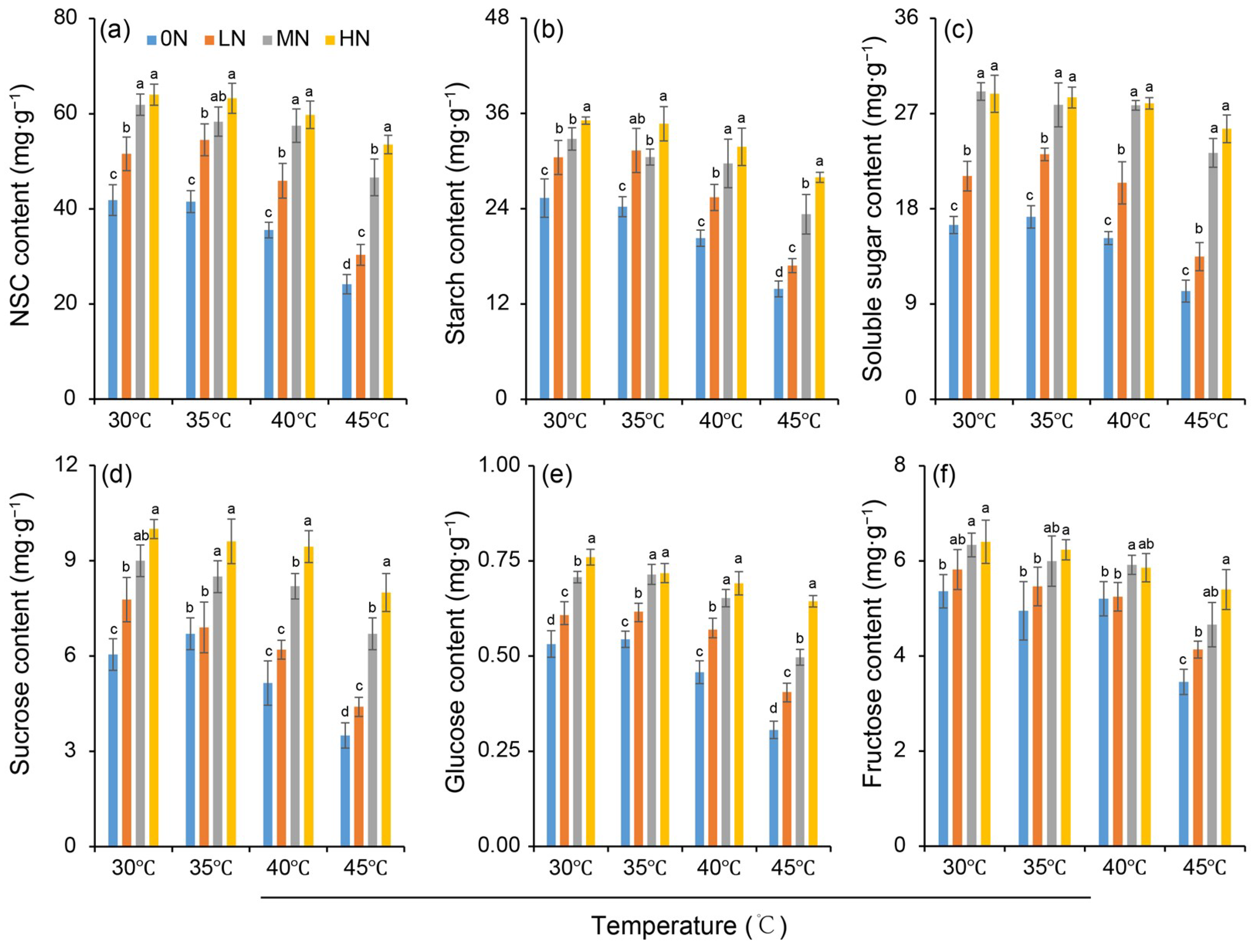

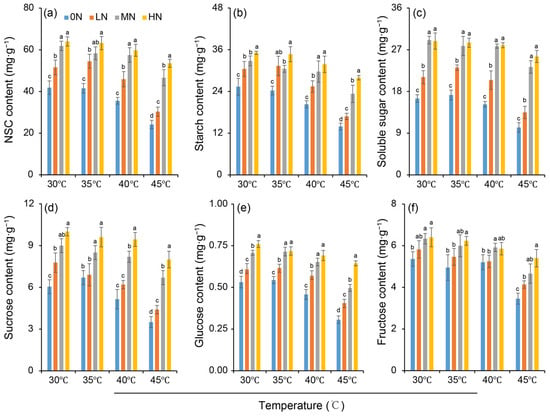

3.5. Nitrogen Regulates Carbohydrates Accumulation and Metabolism in Rice Seedling Plants Under Heat Stress

The NSC, starch, soluble sugar, sucrose, glucose and fructose content were affected by heat stress under different nitrogen conditions (Figure 5). It was found that these carbohydrate contents were increased as the nitrogen levels increased within the same temperature (Figure 5a–f). Compared to the 30 °C control, 35 °C had no significant impact on carbohydrate contents across nitrogen treatments. In contrast, high-temperature treatments (40 °C and 45 °C) significantly reduced the levels of all measured carbohydrates compared to the control. The reduction caused by 45 °C was more severe than that by 40 °C, and the extent of this heat-induced decrease was diminished by higher nitrogen inputs. While the fructose content exhibited a smaller response to nitrogen variation compared to other sugars, all carbohydrate fractions were sensitive to high-temperature stress.

Figure 5.

Variations in contents of non-structural carbohydrates (NSC) (a), starch (b), soluble sugar (c), sucrose (d), glucose (e) and fructose (f)_in rice plants under different nitrogen conditions when subjected to heat stress. 0N, LN, MN and HN denote zero nitrogen, low nitrogen, medium nitrogen, and high nitrogen. Vertical bars denote ± standard deviations (n = 3). Different lowercase letters denote significant differences for the same temperature among different nitrogen treatments with a least significant difference (LSD) test at p ≤ 0.05.

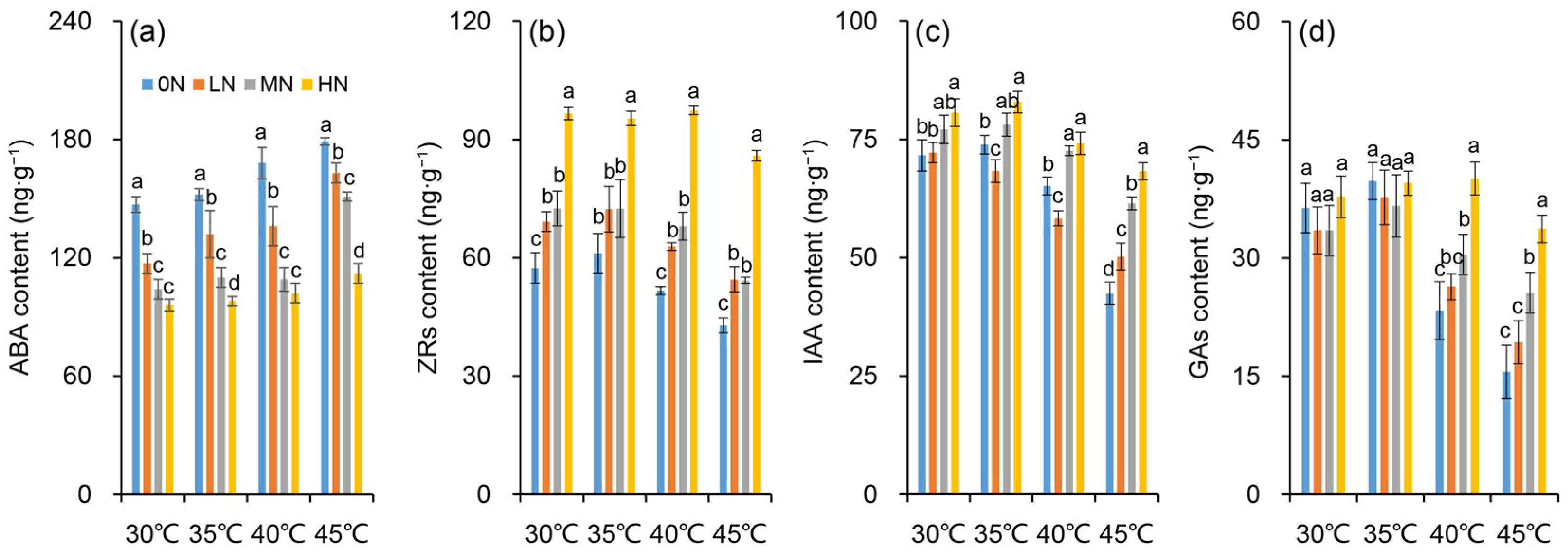

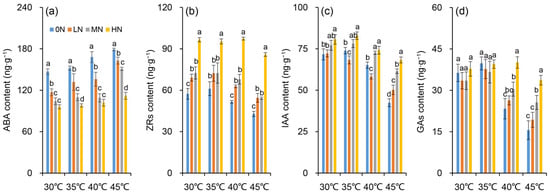

3.6. Nitrogen Regulate the Phytohormones Contents in Rice Seedling Plants Under Heat Stress

It was observed that the hormone contents varied among nitrogen levels under different temperatures. However, the change patterns differed among treatments and depend on hormones (Figure 6). The ABA content decreased obviously as the nitrogen level increased (Figure 6a). There were minor differences in the ABA contents between the MN and HN treatments at 30, 35, and 40 °C, while a notable difference was observed among all nitrogen treatments at 45 °C. In contrast, the IAA, ZR, and GA contents increased significantly with increasing nitrogen supply (Figure 6b–d). For ZR, the highest content was recorded in the HN treatment, which was significantly higher than that in the other treatments across all temperatures. The highest IAA content was also found in the HN treatment, but obvious differences among nitrogen treatments were only detected under the 45 °C condition. Regarding GA, there were almost no obvious differences among nitrogen levels at 30 and 35 °C. However, the highest GA content was observed in the HN treatment when subjected to heat stress of 40 and 45 °C, in which the content was significantly higher than those in the other nitrogen levels.

Figure 6.

Changes in contents of abscisic acid (ABA) (a), zeatin riboside (ZR) (b), indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) (c) and gibberellins (GAs) (d) in rice plants under different nitrogen conditions when subjected to heat stress. 0N, LN, MN and HN denote zero nitrogen, low nitrogen, medium nitrogen, and high nitrogen. Vertical bars denote ± standard deviations (n = 3). Different lowercase letters denote significant differences for the same temperature among different nitrogen treatments with a least significant difference (LSD) test at p ≤ 0.05.

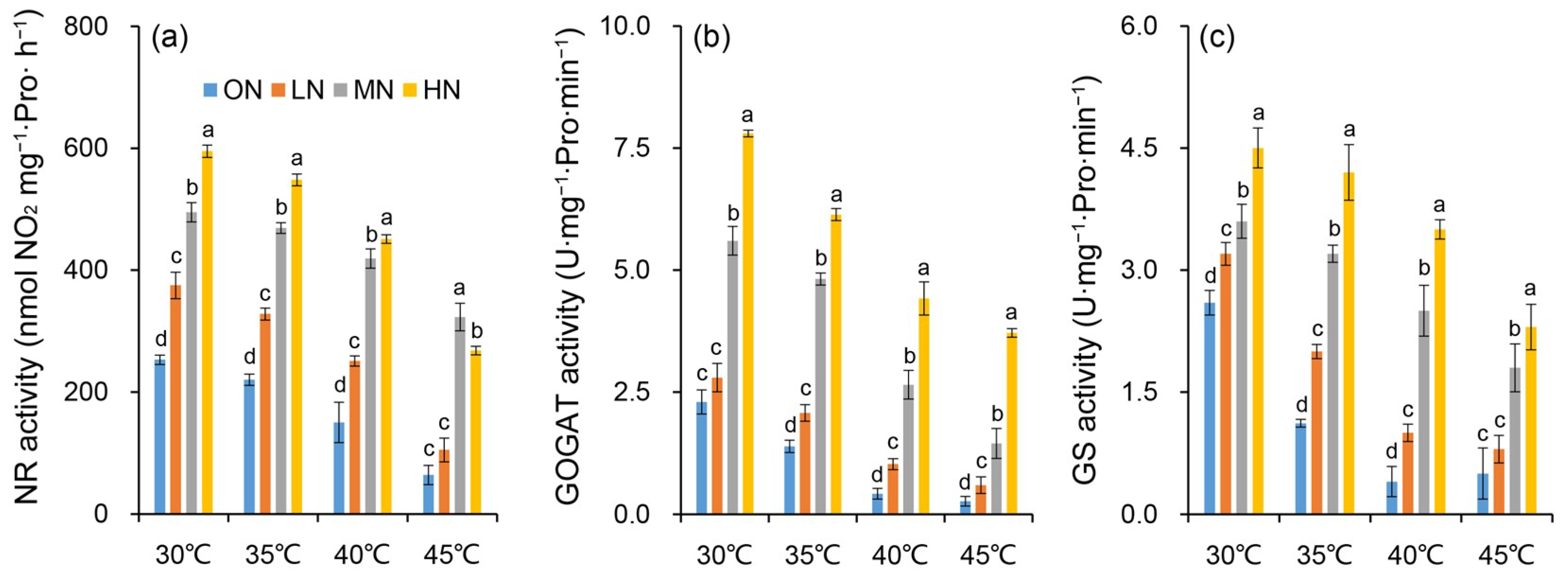

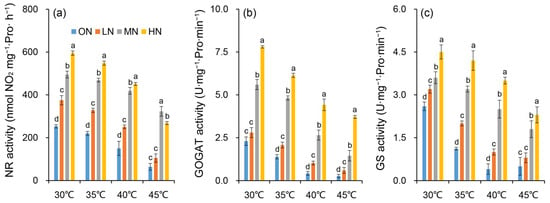

3.7. Nitrogen Application Protects Against Heat-Induced Reductions in the Activities of Nitrogen Metabolism Enzymes

The enzymatic activities of NR, GOGAT, and GS were affected by heat stress under different nitrogen conditions (Figure 7). Within the same temperature treatment, the activities of nitrogen metabolism-related enzymes in plants increased with elevated nitrogen levels. Specifically, leaf NR, GOGAT, and GS activities generally exhibited a significant increasing trend with higher nitrogen supply (Figure 7a–c). In contrast, within the same nitrogen level, nitrogen metabolism-related enzyme activities decreased significantly as the temperature increased. This phenomenon may be attributed to the disrupted three-dimensional spatial conformation of proteins or damaged amino acid composition of enzyme active sites under high temperatures (40 °C and 45 °C), thereby leading to a substantial reduction in enzymatic activity.

Figure 7.

Changes in activities of nitrate reductase (NR) (a), glutamine oxoglutarate aminotransferase (GOGAT) (b) and glutamate synthase (GS) (c) in rice plants under different nitrogen conditions when subjected to heat stress. 0N, LN, MN and HN denote zero nitrogen, low nitrogen, medium nitrogen, and high nitrogen. Vertical bars denote ± standard deviations (n = 3). Different lowercase letters denote significant differences for the same temperature among nitrogen treatments with a least significant difference (LSD) test at p ≤ 0.05.

3.8. Interaction Effect Between Nitrogen and Temperature Treatments on Physiological Parameters in Rice

Except for plant height, all other parameters (including chlorophyll content, dry matter weight, etc.) were significantly affected by temperature. This indicates that heat stress exerts a significant regulatory effect on most morphological and physiological indices of rice, while its impact on plant height is not significant. Similarly, the interaction effects of temperature × nitrogen on all other parameters reached significant (p < 0.05) or extremely significant (p < 0.01) levels. This indicates that the regulatory effect of nitrogen on rice physiological parameters varies with temperature conditions, and vice versa. The impact of high temperature is also dependent on nitrogen levels, suggesting that the two factors have an interactive regulatory relationship. The interaction effect of temperature × nitrogen on plant height was not significant (NS), which demonstrates that the influence of nitrogen on plant height is independent of temperature. In addition, temperature itself has no significant effect on plant height, indicating that plant height is solely regulated by nitrogen.

Notably, there were no significant responses in SOD activity and POD activity to nitrogen, while all other parameters were extremely significantly affected by nitrogen (p < 0.01). This indicates that nitrogen levels exert a strong regulatory effect on rice’s chlorophyll synthesis, biomass accumulation, antioxidant system (mainly CAT activity), carbon–nitrogen metabolism, and hormone levels, while their impact on the activity of SOD and POD enzymes is not obvious.

In summary, nitrogen can alter the response pattern of rice to high temperatures under heat stress by regulating pathways such as chlorophyll synthesis, antioxidant systems, and carbon–nitrogen metabolism (e.g., for parameters with significant interactions, including MDA, osmotic regulatory substances, and nitrogen metabolism enzymes) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Analysis of variance for the effect of nitrogen, temperature and their interactions on rice plant morphology and physiological parameters.

4. Discussion

Temperature is one of the most important environment factors affecting crop growth. High-temperature stress imposes a substantial threat to the productivity of cereal crops during both vegetative and reproductive stages. It can induce the accumulation of ROS, impair photosynthetic apparatus, disrupt carbon assimilation, and perturb phytohormone metabolism, collectively leading to respiratory imbalance [48]. Consistently, our results demonstrate that high temperatures significantly inhibit the growth of rice seedlings (Figure 1). This inhibition was evident not only in compromised plant phenotypes (Figure 1a) but also in a marked decrease in chlorophyll content coupled with significant increases in the levels of MDA and H2O2. Undoubtedly, the severity of high-temperature stress correlates strongly with the temperature magnitude. Notably, our findings reveal that nitrogen nutrition significantly mitigates high temperature-induced damage. With increasing nitrogen supply, the extent of reduction in both growth and physiological parameters under high-temperature stress (40 °C and 45 °C) was substantially alleviated (Figure 2). It is important to note that the regulatory role of nitrogen in plant responses to high-temperature stress remains contentious. Under conventional agronomic conditions, excessive nitrogen application can suppress rice development, often leading to excessive vegetative growth, heightened risks of delayed maturation and lodging at harvest, and ultimately compromised yield formation and stress resilience [49]. These issues are particularly pronounced under high-temperature environments. Conversely, high-temperature stress escalates plant respiration and metabolic consumption. In this context, an appropriately increased nitrogen supply may enhance thermotolerance [50]. In our study, a moderately elevated nitrogen level did not trigger the excessive vegetative growth of rice seedlings. Moreover, under temperature stress, rice plants receiving higher nitrogen exhibited significantly superior growth performance compared to those under lower nitrogen regimes.

Photosynthesis is one of the most physiologically sensitive processes to high temperatures [51,52] When temperatures exceed the optimal range by 10–15 °C, the photosynthetic electron transport chain and carbon assimilation processes are typically disrupted or impaired [53,54]. In this study, photosynthesis under high-temperature stress was significantly inhibited, as evidenced by substantial reductions in chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and total chlorophyll (a+b) content (Figure 1b–e). Moreover, the decline in chlorophyll content indicates an accelerated leaf senescence process, both of which are key factors limiting rice growth, development, and yield formation. Notably, nitrogen availability serves as a central regulatory factor in mitigating high-temperature stress. Under 0N conditions, plants exhibit typical chlorosis symptoms, highlighting the fundamental role of nitrogen in chlorophyll synthesis [55,56]. High-temperature stress (40 °C and 45 °C) further exacerbated this chlorosis. In contrast, increasing the nitrogen supply level gradually alleviated high-temperature-induced chlorophyll degradation. This protective effect of nitrogen aligns with the perspective that under stress conditions, nitrogen influences leaf photosynthesis more likely through regulating carbohydrate metabolism rather than directly altering leaf sensitivity to carbohydrates [57]. This mechanism may sustain the substrates and physiological processes required for maintaining chlorophyll structural integrity and functionality. Maintaining the stability of the photosynthetic system under high-temperature environments is crucial. Supporting evidence comes from studies showing that transgenic Arabidopsis expressing a thermostable Rubisco activase exhibited superior photosynthetic rates and recovery capacity after high-temperature stress compared to wild-type plants [58]. This finding suggests that enhancing the heat tolerance of photosynthesis-related enzymes is significant for improving crop stress resistance. This regulatory process may be associated with nitrogen levels, where nitrogen could influence protein stability or repair mechanisms, thereby affecting photosynthesis and subsequently modulating crop thermotolerance.

Nitrogen application mitigated high-temperature stress-induced chlorophyll degradation, which is a process that is directly regulated by oxidative stress caused by the excessive accumulation of ROS. High temperatures disrupt the dynamic balance between ROS production and scavenging in rice cells. On one hand, they accelerate electron leakage from the chloroplast electron transport chain. On the other hand, they promote a mitochondrial respiratory burst and activate NADPH oxidases on the cell membrane, leading to an excessive generation of ROS such as superoxide anion (O2−) and H2O2 [59]. Uncontrolled ROS bursts trigger membrane lipid peroxidation, resulting in a significant accumulation of MDA, which is a marker of membrane damage. Simultaneously, ROS attack chlorophyll molecules and photosynthetic apparatus proteins, ultimately causing chlorophyll degradation and impaired photosynthetic function [60]. The results of this study demonstrate that high-temperature stress significantly elevated MDA and H2O2 levels in plants, while nitrogen application suppressed their accumulation (Figure 3), aligning with previous research findings [61]. This inhibitory effect stems from nitrogen-enhanced antioxidant enzyme system activity. Under 45 °C high-temperature stress, nitrogen application notably increased the activities of SOD and CAT (Figure 4). Among these, SOD primarily catalyzes the disproportionation of superoxide anions to produce H2O2, while CAT, POD, and APX further decompose H2O2 into harmless water molecules [62]. Crucially, nitrogen application strengthens this antioxidant enzymatic reaction chain. For instance, studies have shown that nitrogen application under high-temperature stress can reduce the H2O2 content in rice leaves and grains by 30.3% and 45.3%, respectively [63], thereby maintaining cellular redox homeostasis through ROS scavenging mechanisms. This process prevents oxidative damage to biomacromolecules, promotes damage repair, and ensures cellular structural integrity [64]. This confirms that ROS homeostasis maintenance is a core mechanism through which nitrogen application enhances rice thermotolerance. Additionally, the nitrogen-mediated regulation of oxidative stress may interact with carbohydrate metabolism dynamics and phytohormone signaling pathways under high-temperature stress [65,66]. For example, nitrogen application can upregulate the expression of ROS-responsive transcription factors, which in turn co-regulate the expression levels of antioxidant genes and stress-related hormone (such as ABA and SA) biosynthesis genes [67,68]. This indicates that under high-temperature stress, nitrogen can optimize the resource allocation pattern of rice between defense activation and metabolic stability, constructing a multi-pathway synergistic regulatory network. Ultimately, this alleviates ROS-induced damage and sustains rice yield.

Compared to the LN and 0N treatments, nitrogen supplementation significantly increased the accumulation of carbohydrates in rice under both normal and high-temperature conditions, including NSC, soluble sugars, starch, sucrose, fructose, and glucose (Figure 5). This finding aligns with previous studies reporting that nitrogen application enhances ATP/ATPase activity while concurrently reducing the contents of MDA and H2O2 [41]. The accumulation of carbohydrates is attributed to three synergistic physiological mechanisms. Firstly, nitrogen improves photosynthetic efficiency by upregulating the activity of photosynthetic enzymes and promoting chloroplast development under favorable temperatures, thereby driving the processes of photosynthetic carbon fixation and assimilation [69,70]. Secondly, nitrogen maintains the structural and functional stability of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco) under heat stress, ensuring the integrity of the photosynthetic apparatus and the rate of carbon assimilation. Thirdly, nitrogen induces the expression of sucrose transporter genes, accelerating the transport of photosynthetic products to the grains [71,72]. Consequently, the accumulated carbohydrates exert threefold synergistic stress resistance effects: serving as energy substrates to support the repair of cellular metabolic damage, acting as osmoregulatory substances to maintain membrane stability, and directly or indirectly scavenging ROS to mitigate oxidative damage [73]. Through the coordinated regulation of carbon allocation under stress defense activation mechanisms, the aforementioned processes enhance the thermotolerance of rice, ultimately ensuring yield stability under the background of climate change.

The antagonistic dynamic changes in plant hormones under high-temperature stress, including an increase in ABA content and decreases in IAA, ZRs, and GAs content, jointly regulate the formation of heat tolerance in rice. The data from this study confirm that the ABA content is positively correlated with increasing temperature [74]. However, high-nitrogen treatment significantly suppressed ABA accumulation under high-temperature stress, suggesting that ABA primarily functions as a biomarker of stress damage in this process rather than serving as an effector of nitrogen-mediated thermotolerance [38]. This negative correlation between nitrogen and ABA exhibits cross-species conservation, as a similar nitrogen-regulated accumulation of ABA has also been observed in maize under low-temperature stress [75]. From a physiological mechanism perspective, high nitrogen counteracts the reductions in IAA, ZRs, and GAs levels induced by high temperatures (40 °C/45 °C, Figure 6) through three synergistic pathways: (1) activating ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco) activity and preserving chloroplast integrity to ensure photosynthetic efficiency [67,68]; (2) enhancing sucrose transporter activity to promote the efficient allocation of photosynthetic products [71,72]; and (3) strengthening the ROS scavenging system via carbohydrate-mediated antioxidant buffering [73]. Notably, hormones including IAA, ZRs, and GAs synergistically regulate the role of nitrogen in balancing plant growth and heat stress defense. The nitrogen-stabilized levels of these hormones promote cell elongation via GA signaling-mediated cell wall expansion, maintain meristematic activity through ZR-regulated cell cycle progression, and enhance sink organ photoassimilate accumulation via the IAA-mediated partitioning of photosynthetic products. Thereby, they coordinate carbon resource allocation between stress resistance and yield formation in rice [76]. The aforementioned hormone interactions ultimately demonstrate that nitrogen, as a core regulator of the hormonal signaling network, can reshape the adaptive response patterns of rice under extreme climatic conditions.

The core enzymatic pathway of nitrogen assimilation, comprising NR, GS, and GOGAT, has been well established [77]. In this pathway, NR reduces the nitrate nitrogen absorbed by plants into nitrite nitrogen, which is subsequently converted to ammonium nitrogen. GS catalyzes the initial reaction of ammonia fixation, combining ammonium nitrogen with glutamate to form glutamine. GOGAT then synthesizes glutamate using glutamine and α-ketoglutarate. Through the coordinated action of these enzymatic reactions, the efficient conversion of inorganic nitrogen to organic nitrogen is achieved, providing essential substrates for life processes such as protein synthesis. The results of this study indicate that high-temperature stress significantly inhibited the activities of these key nitrogen metabolism enzymes in rice seedlings (Figure 7). Crucially, nitrogen application effectively reversed this inhibitory effect with HN treatment showing particularly notable results, outperforming LN and MN treatments in terms of enzymatic activity recovery (Figure 7). This conclusion aligns with findings from Guo et al. [35] in related maize research, which demonstrated that under high-temperature stress, HN treatment resulted in significantly HN content in maize ear leaves compared to LN and MN treatments, along with markedly elevated activities of GS and GOGAT. Indeed, irrespective of temperature conditions, adequate nitrogen supply is a key factor in activating the activities of NR, GS, and GOGAT [78].

As central enzymes regulating nitrogen assimilation, the activities of NR, GS, and GOGAT directly determine the efficiency of nitrogen uptake and conversion in rice, thereby modulating the supply level of the organic nitrogen pool within the plant. This organic nitrogen pool serves as the material basis for synthesizing key enzymes involved in carbohydrate metabolism and phytohormone biosynthesis. Moreover, the synthesis of amino acids and nucleotides during nitrogen assimilation consumes photosynthetic products, allowing nitrogen assimilation to directly influence carbon allocation patterns within the plant [79]. Simultaneously, nitrogen assimilation products can function as efficient signaling molecules, regulating the synthesis and accumulation of phytohormones. This establishes an interactive feedback regulatory network among nitrogen status, carbohydrate metabolism, and hormone regulation within leaves [80,81,82]. In summary, this study confirms that under high-temperature stress, nitrogen regulates carbohydrate metabolism and hormone levels in rice seedlings by activating the activities of NR, GS, and GOGAT.

5. Conclusions

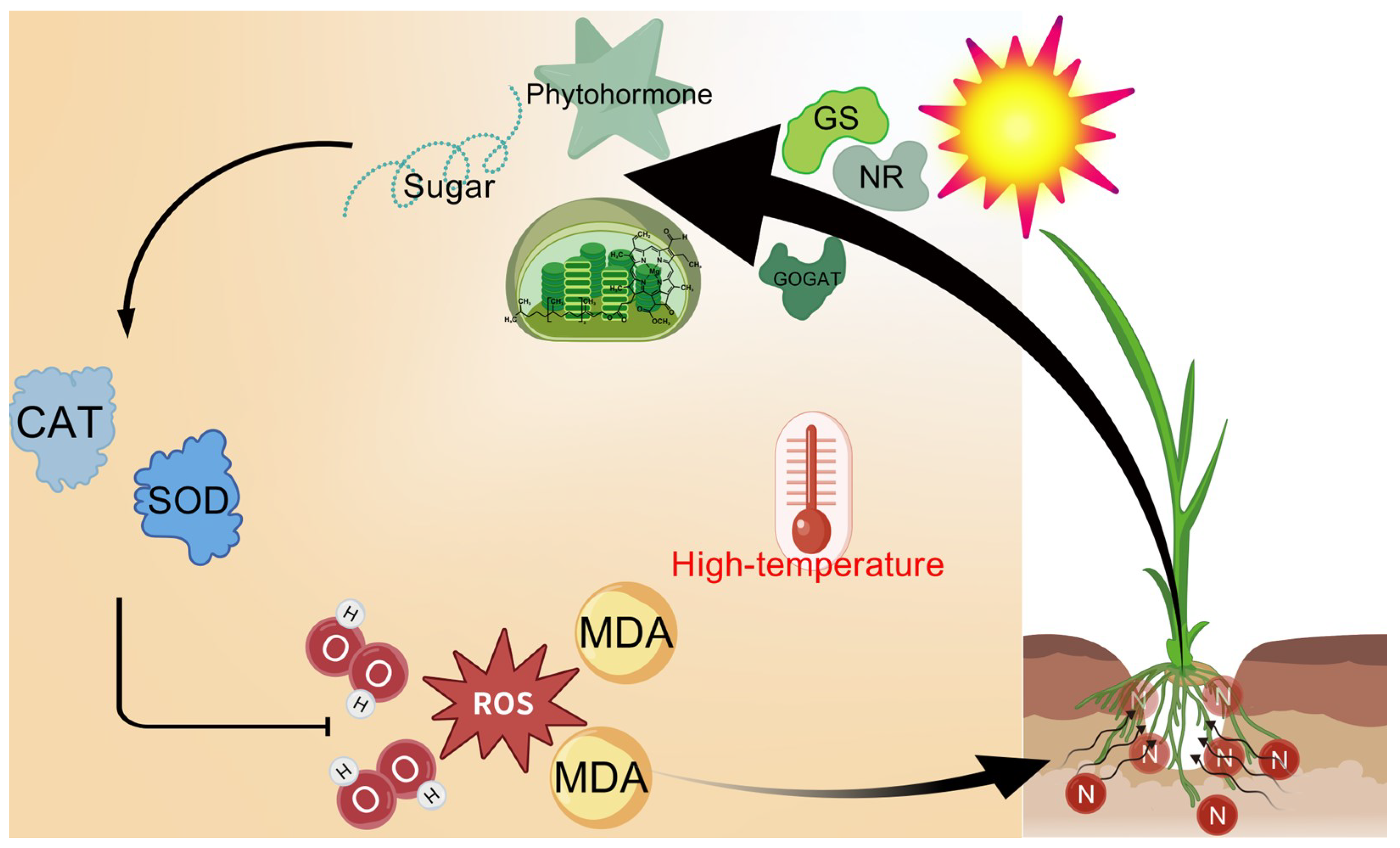

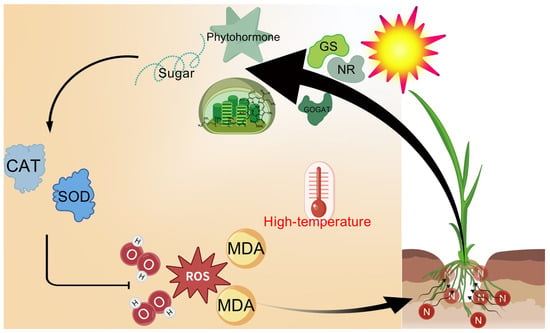

The results demonstrate that 30 °C is optimal for rice seedling growth, while 35 °C exhibits no significant adverse effects. In contrast, 40 °C and 45 °C heat stress severely inhibit growth, reducing yield-related traits and inducing leaf yellowing and senescence, with damage severity escalating at higher temperatures. Plants under 0N and LN treatments suffer the most severe impacts. Nitrogen supply effectively mitigates heat stress damage, and this mitigation effect strengthens with increasing nitrogen levels through multiple mechanisms: (1) maintaining chlorophyll content to alleviate photosynthetic decline; (2) enhancing antioxidant capacity to reduce MDA and H2O2 accumulation, where MN and HN treatments significantly counteract the heat-induced suppression of SOD, POD, and CAT activities under 40 °C/45 °C; (3) regulating carbohydrate metabolism to restore NSC, starch, and soluble sugar accumulation, ensuring energy supply; (4) balancing phytohormones by decreasing ABA and increasing IAA, ZR, and GAs; and (5) protecting the activity and structural stability of nitrogen metabolism enzymes (NR, GS, and GOGAT) to maintain nitrogen assimilation efficiency. As inferred from Figure 8, nitrogen alleviates heat injury by activating NR, GS, and GOGAT to coordinate carbohydrate metabolism and phytohormone dynamics, thereby enhancing antioxidant capacity and sustaining ROS homeostasis.

Figure 8.

Model of nitrogen alleviating heat injury on rice seedling plants. Heat stress induces severe damage to rice seedlings through a burst of reactive oxygen species (ROS), potentially leading to plant mortality. However, nitrogen supplementation enhances the activities of key nitrogen metabolism enzymes under such stress. This enhancement subsequently regulates carbohydrate metabolism and phytohormone homeostasis in the seedlings while simultaneously boosting antioxidant capacity, notably increasing the activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT). Collectively, these nitrogen-mediated responses effectively mitigate the excessive ROS accumulation triggered by heat stress, thereby alleviating heat-induced damage in rice plants. GOGAT, glutamine oxoglutarate aminotransferase; GS, glutamate synthase; MDA, malondialdehyde; NR, nitrate reductase.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.X. and G.F.; writing—original draft, J.L. and G.F.; formal analysis, J.L.; investigation, M.W. and J.Z.; methodology, M.W. and T.C.; software, J.Z. and W.W.; data curation, W.W. and Y.Z.; validation, Y.Z.; funding acquisition, T.C.; project administration, J.X.; writing—review and editing, J.X. and G.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the following grants: The National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFD1500400), the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Key Project LZ24C130005), the Zhejiang Provincial Key Agricultural Technologies Coordinated Promotion Program (2025ZDXT01-1), and the State Key Laboratory of Rice Biology and Breeding (2023ZZKT20404). We sincerely apologize to any colleagues whose relevant work could not be included in the references owing to space constraints.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rahman, A.N.M.R.; Zhang, J. Trends in rice research: 2030 and beyond. Food Energy Secur. 2022, 12, e390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvi, H.U.A.; Tahjib-Ul-Arif, M.; Azim, M.A.; Tumpa, T.A.; Tipu, M.M.H.; Najnine, F.; Dawood, M.F.A.; Skalicky, M.; Brestič, M. Rice and food security: Climate change implications and the future prospects for nutritional security. Food Energy Secur. 2022, 12, e430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Qu, J.; Maraseni, T.N.; Han, J.; Li, H.; Xu, L.; Tang, J.; Wu, D. Trends and magnitude of urban-rural food GHG inequalities over 33 years (1990–2022): Drivers, disparities, and future trends. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 506, 145476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Saito, K.; Oort, P.A.J.V.; Ittersum, M.K.V.; Peng, S.; Grassini, P. Intensifying rice production to reduce imports and land conversion in Africa. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quach, L.; Nguyen, Q.K.; Nguyen, Q.A.; Lan, L.T.T. Rice pest dataset supports the construction of smart farming systems. Data Brief 2024, 52, 110046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthayya, S.; Sugimoto, J.D.; Montgomery, S.; Maberly, G.F. An overview of global rice production, supply, trade, and consumption. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2014, 1324, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, D.K.; Mueller, N.D.; West, P.C.; Foley, J.A. Yield trends are insufficient to double global crop production by 2050. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janni, M.; Maestri, E.; Gulli, M.; Marmiroli, M.; Marmiroli, N. Plant responses to climate change, how global warming may impact on food security: A critical review. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1297569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, W.; Zhang, X.; Yang, J.; Impa, S.M.; Wang, D.; Lai, Y.; Yang, Z.; Xu, H.; Wu, J.; Zhang, J.; et al. Irrigating with cooler water does not reverse high temperature impact on grain yield and quality in hybrid rice. Crop J. 2023, 11, 904–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Li, X.; Schmidt, R.C.; Struik, P.C.; Yin, X.; Jagadish, S.K. Pollen germination and in vivo fertilization in response to high-temperature during flowering in hybrid and inbred rice. Plant Cell Environ. 2018, 41, 1287–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, Z.; Feng, K.; Ji, Y.; Xu, Y.; Tu, D.; Teng, B.; Liu, Q.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Strategies for indica rice adapted to high-temperature stress in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1081807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yan, R.; Wu, G.; Liu, Y.; Wang, M.; Zeng, N.; Jiang, F.; Wang, H.; He, W.; Wu, M.; et al. Unprecedented decline in photosynthesis caused by summer 2022 record-breaking compound drought-heatwave over Yangtze River Basin. Sci. Bull. 2023, 68, 2160–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S. Spatiotemporal Change of heat stress and its impacts on rice growth in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velivelli, S.; Satyanarayana, G.C.; Chowdary, J.S.; Srinivas, G.; Darshana, P.; Konda, G.; Attada, R.; Parekh, A.; Gnanaseelan, C. Surface air temperature variability over India in CMIP6 models during spring and early summer: After effect of El Niño. Clim. Dyn. 2025, 63, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhi, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Wen, Y.; Park, E.; Lee, J.; Wan, X.; Zhu, S.; et al. The characterization, mechanism, predictability, and impacts of the unprecedented 2023 Southeast Asia heatwave. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2024, 7, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, E.S.; Pal, J.S.; Eltahir, E.A.B. Deadly heat waves projected in the densely populated agricultural regions of South Asia. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1603322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Cai, W.; Chen, Y.; Liu, S.; Dong, W.; Zhang, H.; Yu, G.; Chen, Z.; He, H.; Guo, W.; et al. Severe summer heatwave and drought strongly reduced carbon uptake in Southern China. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 18813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Guan, X.; Zhou, L.; Asad, M.A.U.; Xu, Y.; Pan, G.; Cheng, F. ABA-triggered ROS burst in rice developing anthers is critical for tapetal programmed cell death induction and heat stress-induced pollen abortion. Plant Cell Environ. 2023, 46, 1453–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samat, A.T.; Soltabayeva, A.; Bekturova, A.; Zhanassova, K.; Auganova, D.; Masalimov, Z.; Srivastava, S.; Satkanov, M.; Kurmanbayeva, A. Plant responses to heat stress and advances in mitigation strategies. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1638213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, N. Fine tuning of ROS, redox and energy regulatory systems associated with the functions of chloroplasts and mitochondria in plants under heat stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Li, J.; Lin, X.; Wang, L.; Yang, X.; Xia, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, S.; Li, H.; Deng, X.; et al. Changes in plant anthocyanin levels in response to abiotic stresses: A meta-analysis. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2022, 16, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, V.D.; Harish; Singh, R.K.; Verma, K.K.; Sharma, L.; Quiroz-Figueroa, F.R.; Meena, M.; Gour, V.S.; Minkina, T.; Sushkova, S.; et al. Recent developments in enzymatic antioxidant defence mechanism in plants with special reference to abiotic stress. Biology 2021, 10, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzetti, M.; Funck, D.; Trovato, M. Proline and ROS: A unified mechanism in plant development and stress response? Plants 2025, 14, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Xie, K.; Hu, Q.; Wu, C.; Wang, Z.; Wang, W.; Xiong, D.; Huang, J.; Peng, S.; Cui, K. Alternate wetting and drying irrigation at tillering stage enhances the heat tolerance of rice by increasing sucrose and cytokinin content in panicles. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1598652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadarajah, K.K. ROS homeostasis in abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Tao, W.; Gao, H.; Chen, L.; Zhong, X.; Tang, M.; Gao, G.; Liang, T.; Zhang, X. Physiological traits, gene expression responses, and proteomics of rice varieties varying in heat stress tolerance at the flowering stage. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1489331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.Q.; Chen, Y.X.; Ju, Y.L.; Pan, C.Y.; Shan, J.X.; Ye, W.W.; Dong, N.Q.; Kan, Y.; Yang, Y.B.; Zhao, H.Y.; et al. Fine-tuning gibberellin improves rice alkali-thermal tolerance and yield. Nature 2025, 639, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Yu, P.; Fu, W.; Li, G.; Feng, B.; Chen, T.; Li, H.; Tao, L.; Fu, G. Acid invertase confers heat tolerance in rice plants by maintaining energy homoeostasis of spikelets. Plant Cell Environ. 2020, 43, 1273–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, B.; Zhang, C.; Chen, T.; Zhang, X.; Tao, L.; Fu, G. Salicylic acid reverses pollen abortion of rice caused by heat stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2018, 18, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, G.; Fu, W.; Feng, B.; Chen, T.; Peng, S.; Tao, L.; Fu, G. Abscisic acid negatively modulates heat tolerance in rolled leaf rice by increasing leaf temperature and regulating energy homeostasis. Rice 2020, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, Y.; Lin, J.; Feng, B.; Zhu, A.; Zhao, X.; Wang, D.; Zeng, Y.; Yang, H.; Wang, S.; et al. Acetate prevents pistil dysfunction in rice under heat stress by inducing methyl jasmonate and quercetin synthesis. J. Adv. Res. 2025, 78, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Qin, Y.; Lin, J.; Chen, T.; Li, S.; Chen, Y.; Xiong, J.; Fu, G. Unraveling the nexus of drought stress and rice physiology: Mechanisms, mitigation, and sustainable cultivation. Plant Stress. 2025, 17, 100973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Xu, C.; Tang, R.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, W.; Guan, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Ding, J.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Response of photosynthesis and chlorophyll fluorescence to nitrogen changes in rice with different nitrogen use efficiencies. Plants 2025, 14, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Jiang, X.; Xu, Z.; Chen, W.; Cheng, X.; Xu, H. Analysis of erect-panicle japonica rice in northern China: Yield, quality status, and quality improvement directions. Plants 2024, 13, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Wang, R.; Chen, C.; Yin, B.; Ding, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhao, M.; Zhou, B. Nitrogen supply mitigates heat stress on photosynthesis of maize (Zea mays L.) during early grain filling by improving nitrogen assimilation. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2024, 210, e12750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, C.; Xu, P.; He, Y.; Wang, H.; Ke, J.; He, H.; Wu, L. The application of mixed nitrogen increases photosynthetic and antioxidant capacity in rice (Oryza sativa) under heat stress at flowering stage. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2023, 45, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Deng, J.; Lu, J.; Wang, X.; Lu, B.; Tian, X.; Zhang, Y. High nitrogen levels alleviate yield loss of super hybrid rice caused by high temperatures during the flowering stage. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DuBois, M.; Gilles, K.A.; Hamilton, J.K.; Rebers, P.A.; Smith, F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal. Chem. 1956, 28, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Feng, B.; Chen, T.; Fu, W.; Li, H.; Li, G.; Jin, Q.; Tao, L.; Fu, G. Heat stress-reduced kernel weight in rice at anthesis is associated with impaired source-sink relationship and sugars allocation. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2018, 155, 718–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butnariu, M.; Coradini, C.Z. Evaluation of biologically active compounds from Calendula officinalis flowers using spectrophotometry. Chem. Cent. J. 2012, 6, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooda, V.; Sachdeva, V.; Chauhan, N. Nitrate quantification: Recent insights into enzyme-based methods. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2016, 35, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, S.; Guerriero, G.; Vona, V.; Rigano, V.D.M.; Carfagna, S.; Rigano, C. Glutamate synthase activities and protein changes in relation to nitrogen nutrition in barley: The dependence on different plastidic glucose-6P dehydrogenase isoforms. J. Exp. Bot. 2005, 56, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannopolitis, C.N.; Ries, S.K. Superoxide dismutases: I. Occurrence in higher plants. Plant Physiol. 1977, 59, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maehly, A.C.; Chance, B. The assay of catalases and peroxidases. Methods Biochem. Anal. 1954, 1, 357–424. [Google Scholar]

- Dhindsa, R.S.; Plumb-Dhindsa, P.; Thorpe, T.A. Leaf senescence: Correlated with increased levels of membrane permeability and lipid peroxidation, and decreased levels of superoxide dismutase and catalase. J. Exp. Bot. 1981, 32, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, T.; Frenkel, C. Involvement of hydrogen peroxide in the regulation of senescence in pear. Plant Physiol. 1977, 59, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.T.; Bhowmik, S.D.; Long, H.; Cheng, Y.; Mundree, S.; Hoang, L.T.M. Rapid accumulation of proline enhances salinity tolerance in Australian wild rice Oryza australiensis domin. Plants 2021, 10, 2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wang, H.; Li, H.; Feng, B.; Fu, W.; Ma, J.; Li, J.; Wu, Z.; Islam, M.R.; Chen, T.; et al. GRAIN SIZE ON CHROMOSOME 2 orchestrates phytohormone, sugar signaling and energy metabolism to confer thermal resistance in rice. Physiol. Plant. 2025, 177, e70113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Buresh, R.J.; Huang, J.; Zhong, X.; Zou, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, G.; Liu, Y.; Hu, R.; Tang, Q.; et al. Improving nitrogen fertilization in rice by site specific N management. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 30, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Chen, T.; Feng, B.; Peng, S.; Tao, L.; Fu, G. Respiration, rather than photosynthesis, determines rice yield loss under moderate high-temperature conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 678653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, N.; Hafeez, M.B.; Ghaffar, A.; Kausar, A.; Zeidi, M.A.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Farooq, M. Plant photosynthesis under heat stress: Effects and management. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2023, 206, 105178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatma, M.; Iqbal, N.; Sehar, Z.; Alyemeni, M.N.; Kaushik, P.; Khan, N.A.; Ahmad, P. Methyl jasmonate protects the PS II system by maintaining the stability of chloroplast D1 protein and accelerating enzymatic antioxidants in heat-stressed wheat plants. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, F.; Huang, J.; Cui, K.; Nie, L.; Shah, T.; Chen, C.; Wang, K. Impact of high-temperature stress on rice plant and its traits related to tolerance. J. Agric. Sci. 2011, 149, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, A.; Thomas, J.; Ali, H.H.; Zaheer, M.S.; Ahmad, N.; Pereira, A. High night temperature stress on rice (Oryza sativa)—Insights from phenomics to physiology. A review. Funct. Plant Biol. 2024, 51, FP24057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arambam, S.; Bokado, K.; Barkha. Role of nitrogen and silicon in improving growth, yield, and stress tolerance of rice (Oryza sativa L.): A review. Int. J. Agron. 2025, 8, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waraich, E.A.; Ahmad, R.; Halim, A.; Aziz, T. Alleviation of temperature stress by nutrient management in crop plants: A review. J. Soil. Sci. Plant Nut. 2012, 12, 221–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya, T.; Noguchi, K.; Terashima, I. Effect of nitrogen nutrition on the carbohydrate repression of photosynthesis in leaves of Phaseolus vulgaris L. J. Plant Res. 2010, 123, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Li, C.; Portis, A.R. Arabidopsis thaliana expressing a thermostable chimeric Rubisco activase exhibits enhanced growth and higher rates of photosynthesis at moderately high temperatures. Photosynth. Res. 2009, 100, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ji, P.; Liao, J.; Duan, X.; Luo, Z.; Yu, X.; Jiang, C.; Xu, C.; Yang, H.; Peng, B.; et al. CRISPR/Cas knockout of the NADPH oxidase gene OsRbohB reduces ROS overaccumulation and enhances heat stress tolerance in rice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 336–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Yin, T.; Ran, X.; Liu, W.; Shen, Y.; Guo, H.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, C.; Ding, Y.; Tang, S. Stimulus-responsive proteins involved in multi-process regulation of storage substance accumulation during rice grain filling under elevated temperature. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Peng, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, C.; Ran, X.; Shen, Y.; Liu, W.; Ding, Y.; et al. Nitrogen regulated reactive oxygen species metabolism of leaf and grain under elevated temperature during the grain-filling stage to stabilize rice substance accumulation. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2025, 229, 106037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wei, Y. Physiological and transcriptomic analysis of antioxidant mechanisms in sweet sorghum seedling leaves in response to single and combined drought and salinity stress. J. Plant Interact. 2022, 17, 1006–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Cao, X.; Wang, C.; Yue, L.; Chen, X.; Yang, H.; Le, X.; Zhao, X.; Wu, F.; Wang, Z.; et al. Nitrogen-doped carbon dots alleviate the damage from tomato bacterial wilt syndrome, Systemic acquired resistance activation and reactive oxygen species scavenging. Environ. Sci. Nano 2021, 8, 3806–3819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; He, T.; Farrar, S.; Ji, L.; Liu, T.; Ma, X. Antioxidants maintain cellular redox homeostasis by elimination of reactive oxygen species. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 44, 532–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.; Cao, X.; Zhang, M.; Wei, X.; Zhang, J.; Wan, X. Plant nitrogen availability and crosstalk with phytohormones signallings and their biotechnology breeding application in crops. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2023, 21, 1320–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, X.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Xia, H.; Du, W.; Fan, S.; Kong, L. Low-nitrogen stress stimulates lateral root initiation and nitrogen assimilation in wheat, Roles of phytohormone signaling. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2020, 40, 436–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Liang, X.; Wang, W.; Huo, Z.; Zhao, C. The research progress on the effects of phytohormones on nitrogen use efficiency in rice. Plants 2025, 14, 2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J. A starch- and ROS-regulating heat shock protein helps maintain male fertility in heat-stressed rice plants. Plant Physiol. 2023, 192, 2227–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Cui, K.; Wei, D.; Huang, J.; Xiang, J.; Nie, L. Relationships of non-structural carbohydrates accumulation and translocation with yield formation in rice recombinant inbred lines under two nitrogen levels. Physiol. Plant. 2011, 141, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, D.; Yu, T.; Ling, X.; Fahad, S.; Peng, S.; Li, Y.; Huang, J. Sufficient leaf transpiration and nonstructural carbohydrates are beneficial for high-temperature tolerance in three rice (Oryza sativa) cultivars and two nitrogen treatments. Funct. Plant Biol. 2015, 42, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoah, J.N.; Keitel, C.; Kaiser, B.N. Nitrogen deficiency identifies carbon metabolism pathways and root adaptation in maize. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2025, 31, 1089–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Hu, Q.; Shi, Y.; Cui, K.; Nie, L.; Huang, J.; Peng, S. Low nitrogen application enhances starch-metabolizing enzyme activity and improves accumulation and translocation of non-structural carbohydrates in rice stems. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Xu, Y.; Fu, W.; Li, H.; Li, G.; Li, J.; Wang, W.; Tao, L.; Chen, T.; Fu, G. RGA1 negatively regulates thermo-tolerance by affecting carbohydrate metabolism and the energy supply in rice. Rice 2023, 16, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.P.; Tripathi, D.K.; Palma, J.M.; Corpas, F.J. Editorial: ROS and phytohormones: Two ancient chemical players in new roles. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 216, 109149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soualiou, S.; Duan, F.; Li, X.; Zhou, W. Nitrogen supply alleviates cold stress by increasing photosynthesis and nitrogen assimilation in maize seedlings. J. Exp. Bot. 2023, 74, 3142–3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, L.; Pei, H.; Xu, Z. Low nitrogen stress stimulating the indole-3-acetic acid biosynthesis of Serratia sp. ZM is vital for the survival of the bacterium and its plant growth-promoting characteristic. Arch. Microbiol. 2017, 199, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishorekumar, R.; Bulle, M.; Wany, A.; Gupta, K.J. An overview of important enzymes involved in nitrogen assimilation of plants. Methods Mol. Biol. 2020, 2057, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar, K.; Ain, N.U.; Prasad, P.V.V.; Naz, M.; Aslam, M.M.; Djalovic, I.; Riaz, M.; Ahmad, S.; Varshney, R.K.; He, B.; et al. Physiological, molecular, and environmental insights into plant nitrogen uptake, and metabolism under abiotic stresses. Plant Genome 2024, 17, e20461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Gao, X.; Fan, W.; Fu, X. Optimizing carbon and nitrogen metabolism in plants: From fundamental principles to practical applications. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2025, 67, 1447–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Fan, X.; Miller, A.J. Plant nitrogen assimilation and use efficiency. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2012, 63, 153–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathee, L.; R, S.; Barman, D.; Adavi, S.B.; Jha, S.K.; Chinnusamy, V.; Datta, S. Nitrogen at the crossroads of light: Integration of light signalling and plant nitrogen metabolism. J. Exp. Bot. 2025, 76, 803–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zayed, O.; Hewedy, O.A.; Abdelmoteleb, A.; Ali, M.; Youssef, M.S.; Roumia, A.F.; Seymour, D.; Yuan, Z.C. Nitrogen journey in plants: From uptake to metabolism, stress response, and microbe interaction. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.