Abstract

Reductive soil disinfestation (RSD) is a promising strategy for mitigating soil degradation and enhancing soil health. While soil organic carbon (SOC) is crucial for soil fertility and climate regulation, the mechanisms underlying its stabilization via plant lignin and microbial humus in the RSD process remain elusive. Using a microcosm experiment, we investigated SOC dynamics by quantifying plant-derived (lignin phenols) and microbial-derived (amino sugars) C during RSD at key stages: initial (2 h), anaerobic (14 and 28 days), and aerobic (35 days). Concurrently, soil properties, microbial PLFA, and enzymatic activity were analyzed to elucidate underlying mechanisms. Over the initial 14 days, plant-derived C increased sharply by 61% before declining, yet still showed a 22% increase by the end of the RSD (35 days), a trend mirrored by bacterial-derived C. In contrast, fungal-derived C initially accumulated rapidly with a significant increase of 43%, then stabilized, and its proportion (21.63%) surpassed that of bacterial-derived C (5.56%). Over time, plant- (25.01% to 19.76%) and bacterial-derived C (7.81% to 5.56%) contributions to decreases in SOC, while fungal-derived C (about 21%) remained stable after day 14. This pattern is likely attributable to the initial anaerobic conditions, which caused a massive die-off of fungi and aerobic bacteria that utilize lignin and necromass, resulting in significant accumulation of both plant- and microbial-derived C. Subsequently, the proliferation of anaerobic bacteria consumed these plant- and bacterial-derived C sources in the soil, leading to their eventual decline. Key drivers of plant-derived C included soil pH, living fungi/bacteria, and β-1,4-glucosidase activity, whereas microbial-derived C depended on total nitrogen and living fungi. Our findings demonstrate that early SOC accumulation under RSD is driven by combined plant lignin and microbial necromass inputs, while fungal necromass becomes pivotal for long-term SOC stabilization, shaped by both abiotic and biotic factors.

1. Introduction

Increasing the sequestration and storage of soil organic carbon (SOC) in agricultural lands is crucial for maintaining and enhancing soil fertility, as well as for mitigating climate warming by reducing CO2 emissions [1,2,3]. However, due to land-use change, intensive agricultural practices, and associated disturbance and erosion, global farmland soils have lost an estimated 4.0 to 133 Pg C over 200 years [4]. China ranks among the most severely impacted nations, with over 40% of its land experiencing significant SOC depletion and a complex degradation syndrome involving salinization, acidification, and monocropping obstacles, especially in intensive farmland [5]. Although continuing substantial organic amendments can increase SOC concentration in intensive systems, it also transforms the soil into a significant source of greenhouse gases [6]. Consequently, enhancing SOC sequestration is equally as important as controlling multiple soil degradation within intensive agricultural systems.

Reductive soil disinfestation (RSD), a cost-effective and eco-friendly approach, has been widely adopted for ameliorating degraded soils (e.g., salinization, acidification, and soil-borne diseases) and sustaining crop production [7,8]. This method only requires simple soil operations, including the addition of fresh residues, water-flooding, and then plastic covering for about 2–3 weeks [9]. Beyond soil remediation, recent research indicates that RSD induces a negative priming effect and increases the abundance of hydrophobic and macromolecular organic components, thereby enhancing SOC storage [10,11]. However, the stability of SOC and its response to RSD, which are strongly associated with the components of SOC, remained unknown. To date, prevailing views hold that SOC is recognized as a complex mixture of plant- and microbial-derived C [12]. Current quantitative estimates suggest that microbial necromass is the direct source of as much as 30–80% of SOC, while plant-derived C can comprise between 20% and 70% of SOC, with variation observed across different ecosystems and soil types and depths [13,14,15]. Thus, identifying the dynamics of these two components’ attributes better serves our understanding of the primary mechanism of SOC sequestration and stabilization during RSD.

Plant residues drive soil microbes to assimilate C into biomass and then, through community succession, convert it into persistent necromass, which accumulates as recalcitrant SOC components that underpin long-term C stabilization [16]. As soil is water-flooded and plastic-mulched during RSD, substance addition can promote the aerobes to exhaust oxygen and create an anaerobic environment in which the facultative and obligate anaerobes thrive [9]. RSD is likely to increase the diversity of bacteria and decrease that of fungi because bacteria are positively sensitive to organic substrates while fungi show poor survival under an anaerobic condition [10]. Analysis of phospholipid fatty acids (PLFAs) found that the living fungi were depleted and living bacteria were shifted from aerobic to anaerobic taxa, resulting in increase in soil microbial biomass C under RSD [16]. Consistently, the specific microbial taxa prevailed after RSD, i.e., Clostridia and Bacillus in Firmicutes and Zopfiella and Chaetomium in Ascomycota, as bacterial taxa (e.g., Candidatus) and fungal taxa (e.g., Cercophora) were depleted [17,18]. Despite marked soil microbial population changes and community succession, little information is available on the dynamics of microbial-derived C and their contributions to SOC during RSD. Simultaneously, plant-derived C enters the soil along with its degradation through aggregate protection and adsorption onto soil minerals and is considered as important as that from microbial necromass, and in some cases, even more so [19]. Numerous studies have indicated that paddy soils are enriched with a greater proportion of plant-derived C, because of the retarded microbial decomposition under anaerobic conditions induced by the flooding of paddies [20]. However, Sokol et al. [21] observed that plant-derived C formation is controlled by the extracellular transformation of plant inputs (e.g., extracellular enzyme activities) and the depolymerization facilitates the formation of soil aggregates and organo-mineral complexes. Alongside the proliferation of anaerobic and facultative microorganisms, RSD stimulates the activity of extracellular enzymes such as β-xylosidase, cellobiohydrolase, and β-glucosidase, which are responsible for degrading lignocellulose and enhancing SOC concentration [10]. However, little information is available on the dynamics of plant-derived carbon and their contributions to SOC during RSD characterized by plant residue incorporation into anaerobic soil.

Therefore, this study employed a 35-day microcosm experiment to systematically investigate the dynamic processes and driving mechanisms through which plant residues and microbial necromass restructure SOC during RSD. Specifically, the experiment addressed two core questions: (i) the dynamics of plant- and microbial-derived C (using lignin phenols and amino sugars as biomarkers, respectively) and their quantitative contributions to SOC, and (ii) the linkages between these C dynamics and shifts in the living microbial community (assessed by PLFA profiling) as well as extracellular enzyme activities. We hypothesized that RSD would promote the accumulation of both C pools, but their contributions to SOC would shift dynamically throughout the process. The study would enhance our understanding of the pathways reshaping table SOC formation during RSD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Soil and Maize Straw Preparation

Soil was collected from an intensive plastic greenhouse (107°98′ E, 34°28′ N) in Yangling, Shaanxi, China. The field had been continuously cultivated with tomato for 8 years, resulting in severe salinization (electrical conductivity (EC) > 896 μS cm−1) and soil-borne diseases (Fusarium wilt caused by Fusarium oxysporum with 106 copies g−1 soil), due to the excessive application of animal manure (>30 Mg ha−1 yr−1) and chemical fertilizers (N, P, and K) (>1.5 Mg ha−1 yr−1) [10]. The soil was classified as Cumulic Haplustalf (USDA system) and Anthrosol (FAO system) with clay loam texture (33.5% clay, 38.6% silt, and 27.9% sand). Other soil properties were as follows: pH 7.96, SOC 9.96 g kg−1, total N 1.36 g kg−1, nitrate-N 219 mg kg−1, and Olsen-P 35.6 mg kg−1. The soil was air-dried, homogenized, and passed through an 8 mm sieve, then stored at room temperature under dry conditions until use. Maize straw used for RSD was taken from an adjacent maize field and contained 438 g C kg−1 and 9.17 g N kg−1. After transportation to the laboratory, soil samples were air-dried and ground to <2 mm, while maize straw was crushed into ~2 mm pieces.

2.2. Microcosm Design

An incubation experiment was conducted using twelve mason jars (diameter: 200 mm, height: 70 mm), each replicated with 600 g of soil amended with maize straw. Based on Lopes et al. [22], the straw was applied at a rate of 2%. The soils were completely submerged with water until a 2 cm water layer remained above the surface, and were then covered with plastic film. All jars were randomly arranged in an incubator maintained at 28 °C, a temperature that approximates the local mean summer temperature. The covers were maintained for 28 days to simulate field RSD conditions, followed by a 7-day uncovered, air-drying phase at the same temperature to simulate the pre-planting period. Destructive sampling was conducted at 2 h (initial stage), 14, 28, and 35 days with three replicates for each time point (2 h–14 d: rapid phase of soluble substrate utilization and the bacterial-dominated period; 14 d–28 d: fungal-mediated decomposition and the stabilization process of microbial-derived C; 28 d–35 d: dynamics of plant- and microbial-derived C after the soil environment converted to an aerobic state following the termination of RSD). All samples were immediately collected, homogenized, and divided into three portions. The first subsample was freeze-dried and stored at −80 °C for analyses of phospholipid fatty acids (PLFAs), amino sugar, and lignin monomer. The second part was sent to the lab by ice boxes and stored at 4 °C for determinations of soil enzyme activities. The third part was air-dried and ground to 2 mm and 0.15 mm for other soil property measurements. As soon as samples were collected at each time point, they were assayed for the target indicators to avoid any deviation caused by prolonged sample storage. During the analysis, a standard clay loam soil (GBW07408) with known SOC and total nitrogen (TN) concentrations and triplicate samples of each soil were employed for quality control.

2.3. Chemical Analysis

Air-dried soil samples were extracted with 1 M KCl solution and soil EC was determined by a DDS-11A conductivity meter (Shanghai Yidian Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) and pH by HQ40D pH meter (Hach Company, Loveland, CO, USA). The SOC was determined with the Walkley–Black method and soil TN was determined with the Kjeldahl method. All the above indices of soil physicochemical properties were determined as described by Bao [23].

For living microorganisms, the community composition was assessed with PLFA analysis. Briefly, the phospholipid fatty acids were extracted from 8 g (dry weight) frozen soil using a phosphorus buffer/CHCl3/CH3OH at a 0.8:1:2 ratio. After being subjected to methyl esterification and purification, PLFAs were quantified by using an Agilent 7890B gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Individual PLFA peaks were identified with a Microbial Identification System (MIDI Inc., Newark, DE, USA). The PLFA markers were identified for fungi (18:1w9c), bacteria (11:0, 12:0, 13:0, 14:0, 15:0, 16:1, 17:0; 18:1, 19:0, i15:0, a15:0, i16:0, a17:0, i17:0, 16:1ω7c, 18:1ω7c), aerobic bacteria (i-15:0, a-15:0, a-17:0, i-17:0, a-17:0), and anaerobic bacteria (14:1, 18:1ω7c, 15:1ω6c, 16:1ω7c, 16:1ω7t, 18:1ω9c, 18:1ω9t) [16]. The activities of soil β-glucosidase, cellobiohydrolase, and β-xylosiase were determined using the microplate fluorometry method [24].

Soil lignin monomer was quantified according to the method outlined by Hedges and Ertel [25]. The freeze-dried samples were digested with alkaline CuO in Teflon vessels under high pressure to breakdown lignin molecules into their monomer phenols. The C18 columns were used for collecting the lignin-derived phenols, which were eluted and derivatized with pyridine and N,O-bis trifluoroacetamide. The lignin-derived phenols were analyzed using an Agilent 7890B gas chromatograph equipped by a flame ionization detector and an HP-5 fused silica column (Agilent Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). Ethylvanillin was added before oxidation as an internal standard and phenylacetic acid was added before derivatization to determine the recovery efficiency of the lignin products. Lignin phenol concentration (Tlp) was computed through adding together the vanillyl monomer (V), syringyl monomer (S), and cinnamyl monomer (C). Soil V- and S-type units were quantified based on their respective aldehyde, ketone, and carboxylic acid derivatives [26]. Specifically, V-type units comprised vanillin, acetovanillone, and vanillic acid, while S-type units consisted of syringaldehyde, acetosyringone, and syringic acid. Soil C-type units consisted of p-coumaric and ferulic acids. Plant-derived C was calculated as follows:

Freeze-dried soil samples were hydrolyzed with 6 M HCl at 105 °C for 8 h to analyze amino sugar. The resulting solution was filtered, neutralized (pH 6.6–6.8), and centrifuged (1000 g, 10 min). The supernatant was lyophilized, and the residue was washed with methanol to recover amino sugars. Following addition of internal standard myoinositol, amino sugars were derivatized to aldononitrile derivatives [27]. Derivatized amino sugars were then acetylated with acetic anhydride (v:v, 1:1) in a dichloromethane atmosphere and quantified using an Agilent 7890B gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped by a flame ionization detector and an HP-5 fused silica column (25 m × 0.32 mm × 0.25 µm). Total amino sugar (Tas) concentration was computed by the sum of three components, i.e., glucosamine (GlcN), galactosamine (GalN) and muramic acid (MurA). Bacterial-derived C was estimated by multiplying muramic acid concentration by 45. Fungal-derived C was calculated by subtracting bacterial muramic acid from total glucosamine, based on the assumption of a 1:2 molar ratio of MueA to GlcN in bacterial cells [16]. Microbial-derived C was determined as the sum of fungal- and bacterial-derived C. Microbial-derived C was calculated as follows:

2.4. Statistical Analysis

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted, and the least significant difference (LSD) test was applied to identify the significant differences in the contributions of plant and microbial residue carbon to soil organic carbon as well as among various soil parameters at the significance level of p < 0.05. Polynomial regression analysis was employed to clarify the variation trends and rates of enzyme activities, plant- and microbial-derived C, and other related variables. Spearman’s correlation and Random Forest analysis were employed to identify the correlation and importance of different variables for dynamics of plant- and microbial-derived C. Heatmap was made by Heml 1.0.1 and other figures were made by Origin Pro2017 (Origin Lab, Northampton, MA, USA). Additionally, partial least squares path modeling (PLS-PM) were implemented in R (version 3.5.0) by using Mantel test within the “vegan” package to quantify the contributions of soil physicochemical, bacterial-derived C, fungal-derived C and plant-derived C to SOC. The best-fitting model was evaluated based on goodness-of-fit index, p value and R-squared using the maximum-likelihood estimation method.

3. Results

3.1. Dynamics of Soil Lignin Phenols and Its Fractions During RSD

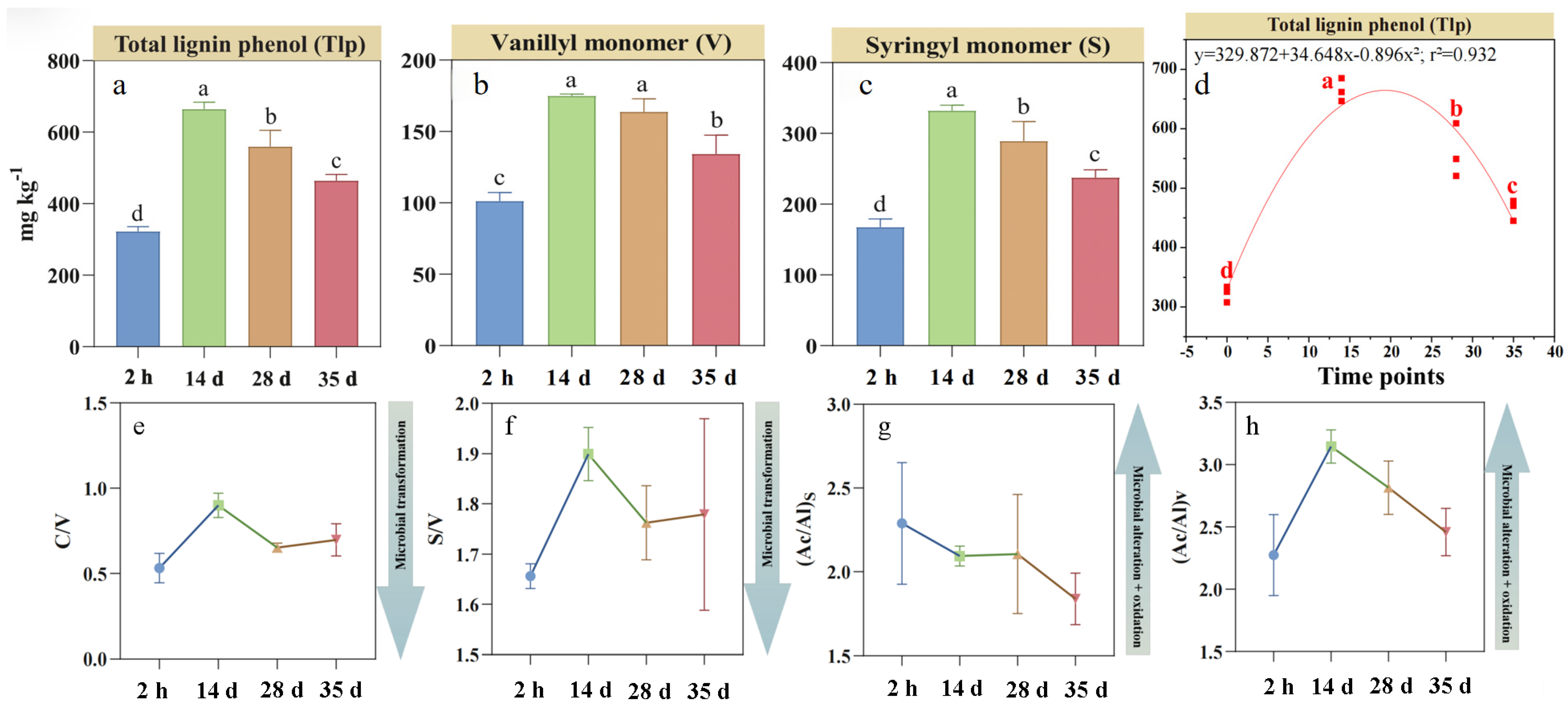

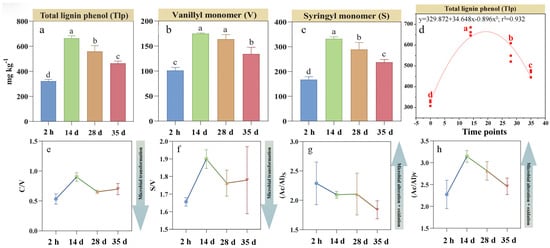

The concentration of soil lignin phenol and its fractions are shown in Figure 1. Compared to the initial 2 h measurement, soil Tlp concentration during RSD exhibited a 1.2-fold increase at days 14, followed by a decline to 38% until days 35 (Figure 1d). Concentrations of V-, S-, and C-type lignin units followed unimodal trends, peaking on day 14 before decreasing (Figure 1a–c). Notably, the sharp decline in V-type units was recorded between days 14 and 28, while C-type units decreased markedly from days 28 to 35. The C/V, S/V, and (Ac/Al)v ratios fluctuated during RSD with peaking at day 14, while the (Ac/Al)s ratios continuously decreased over the 35 days of incubation (Figure 1e–h).

Figure 1.

Changes in individual (a–c) and total (d) lignin phenols and acid/aldehyde ratios (e–h) in lignin monomers during reductive soil disinfestation. Different lowercase letters denote significant differences between soil treatments for each parameter. The values of the histogram are means, while error bars represent standard errors (n = 3).

3.2. Dynamics of Soil Amino Sugars and Its Fractions During RSD

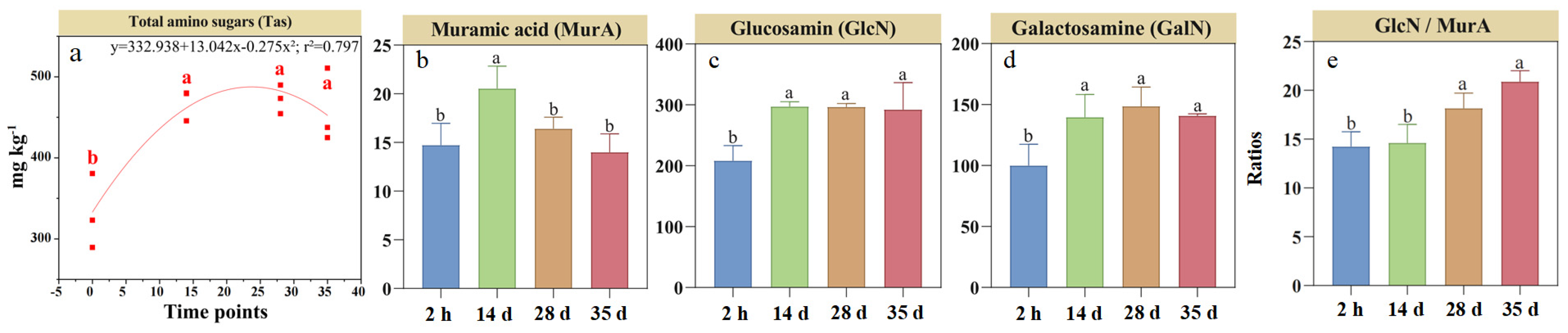

Distinct temporal patterns were observed in amino sugars and its components during RSD (Figure 2). Soil Tas concentration increased by 52% at day 14 compared to the initial 2 h measurement and remained stable until day 35 (Figure 2a). The concentration of MurA, a biomarker of bacterial necromass, increased by 42% by day 14 before declining by 7.1% by day 35 (Figure 2b). In contrast, soil GlcN (primarily fungal-derived) and GalN concentrations increased by 48% and 44%, respectively, by day 14 and remained stable thereafter (Figure 2c,d). Supporting this observation, the GalN/MurA ratio continuously increased by 42% until day 35 from the initial 2 h measurement (Figure 2e).

Figure 2.

Changes in total (a) and individual (b–d) soil amino sugar and muramic acid-to-glucosamine ratios (e) during reductive soil disinfestation. Different lowercase letters denote significant differences between soil treatments for each parameter. The values of the histogram are means, while error bars represent standard errors (n = 3).

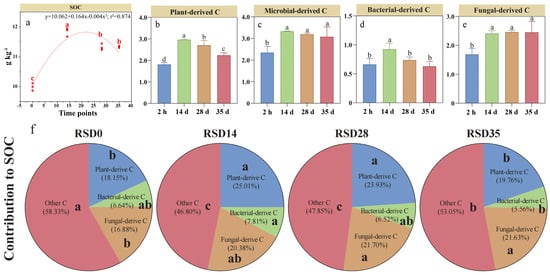

3.3. Dynamics of Microbial- and Plant-Derived C and Their Contributions to SOC During RSD

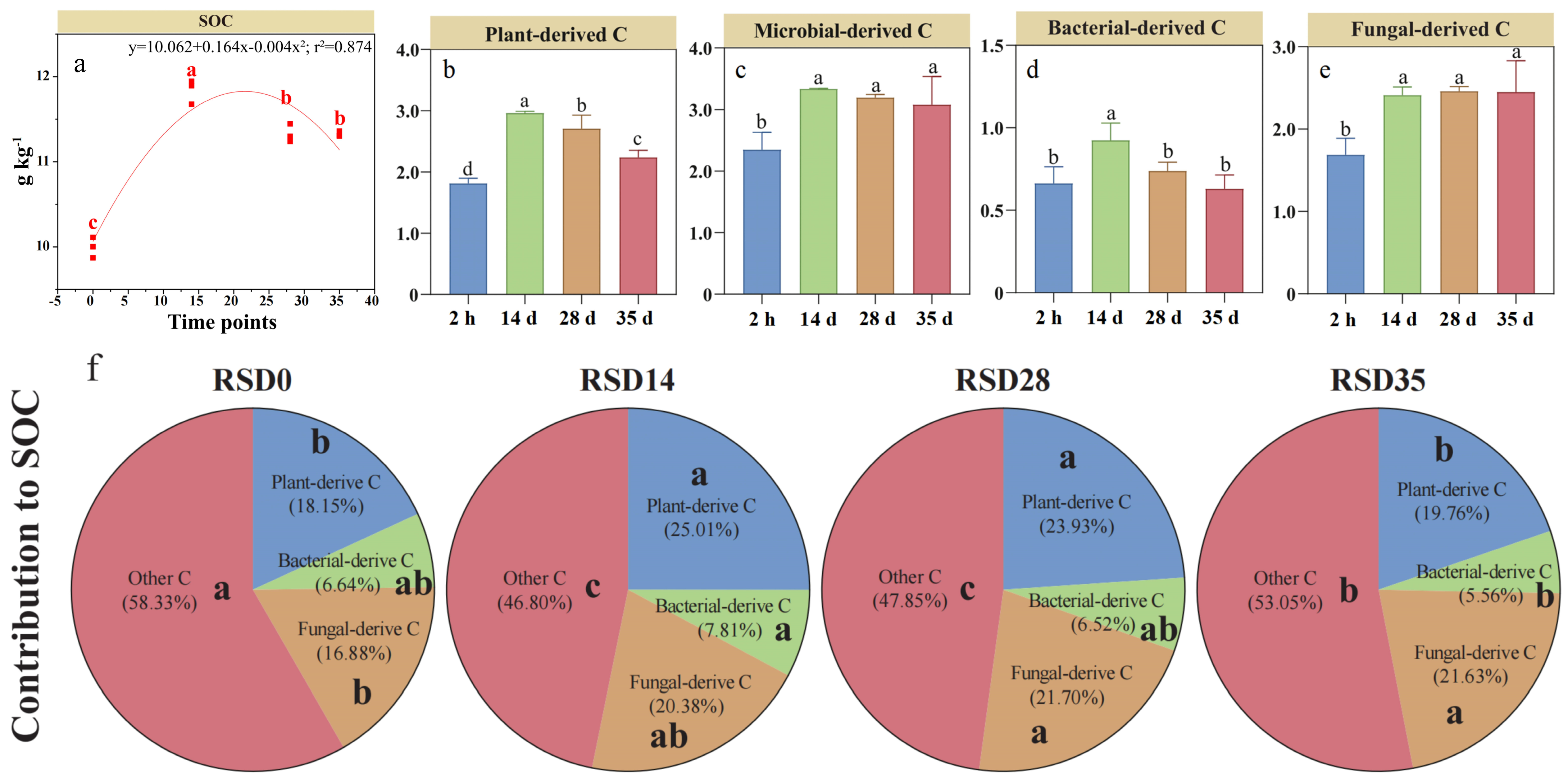

The SOC concentration increased by 18% by day 14 but decreased by 13% by day 35 relative to the 2 h measurement (Figure 3a). Plant-derived C concentration increased by 61% by day 14, but declined to a 22% increase by day 35 relative to the 2 h measurement (Figure 3b). However, microbial-derived C concentration increased by 49% at day 14 compared to the initial 2-h measurement and remained stable until day 35 (Figure 3c). Bacterial-derived C concentration initially increased by 33% by day 14 but continuously returned to baseline levels by day 35, whereas fungal-derived C followed a trend similar to microbial-derived C, increasing by 41–45% (Figure 3d,e). Overall, fungal-derived C was more than 2.7 times greater than bacterial-derived C during RSD. Plant- and microbial-derived C contributed 18–25% and 23–28%, respectively, to SOC. Notably, the contribution of fungal-derived C increased from 16.8% at the 2 h measurement to 20.4% by day 14 and remained stable thereafter (Figure 3f). However, the contribution of bacterial-derived C to SOC showed a weak change within 5.6–7.8% over the 35-day incubation.

Figure 3.

Changes in plant- (b) and microbial-derived C (c–e) and their contributions (f) to soil organic carbon (a) during reductive soil disinfestation. Different lowercase letters denote significant differences between soil treatments for each parameter. The values of the histogram are means, while error bars represent standard errors (n = 3).

3.4. Dynamics of Living Microorganisms and Activities of Extracellular Enzymes During RSD

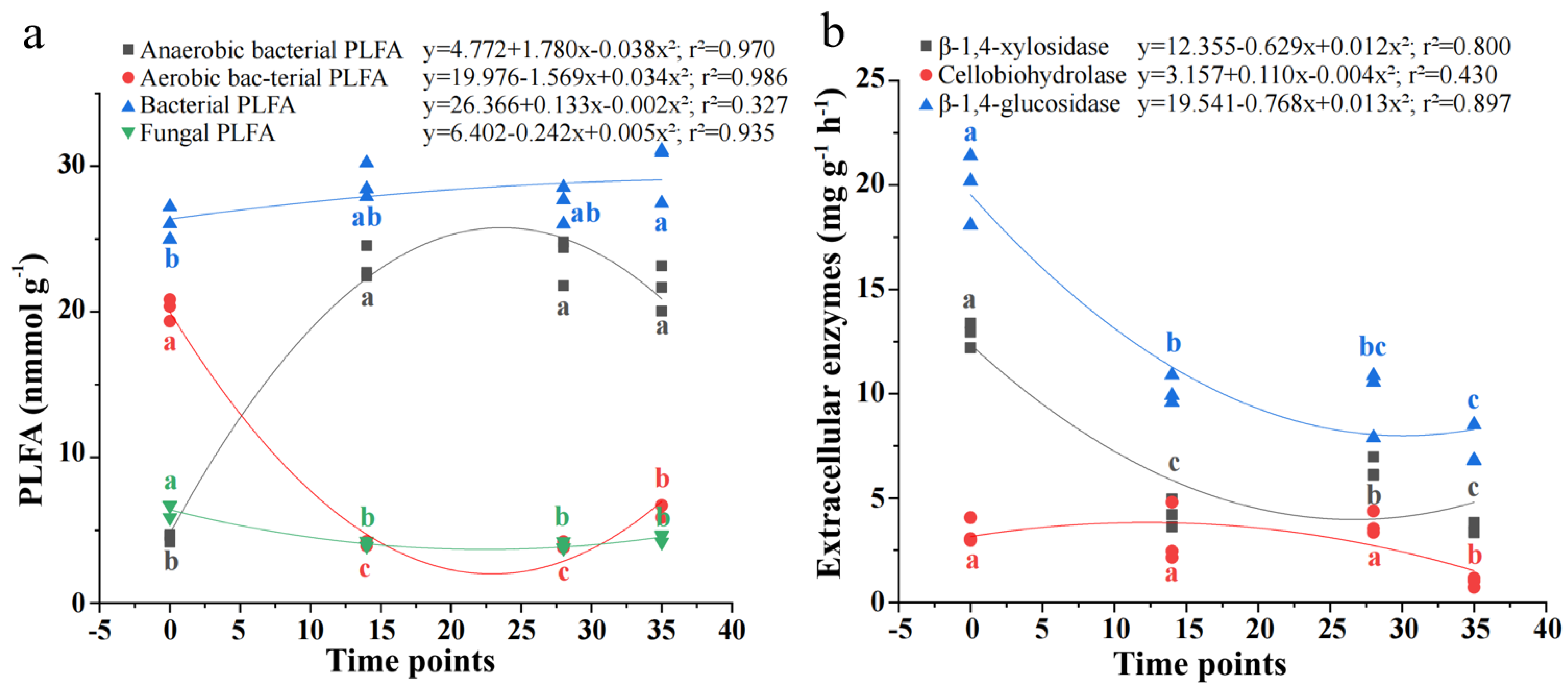

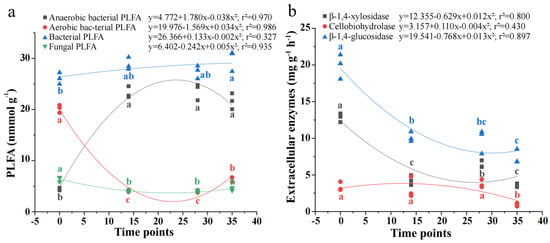

Figure 4 shows the concentration of microbial PLFA and activities of extracellular enzymes during RSD, with the fastest rates of change observed during the 2 h–14 d period. Until day 35, the concentration of bacterial PLFAs continuously increased by 14.5% relative to the 2 h measurement, consistent with the rise in anaerobic bacterial PLFAs (3.81-fold) and the decline in aerobic bacterial PLFAs (68.2%). In contrast, compared to the initial 2 h measurement, fungal PLFAs sharply decreased by 30.1% at day 14 and remained stable until day 35. The peak activities of soil extracellular enzymes occurred at just 2 h, but the sharp reductions in β-1,4-glucosidase and β-1,4-xylosidase were recorded within 14 days, whereas the sharp reduction in cellobiohydrolase was recorded between 28 and 35 days.

Figure 4.

Changes in abundances of bacterial and fungal PLFA (a) and activity of extracellular enzymes (b) during reductive soil disinfestation. Standard error is shown in parentheses (n = 3); Different lowercase letters denote significant differences between soil treatments for each parameter.

3.5. Divergent Controls on Plant- and Microbial-Derived C During RSD

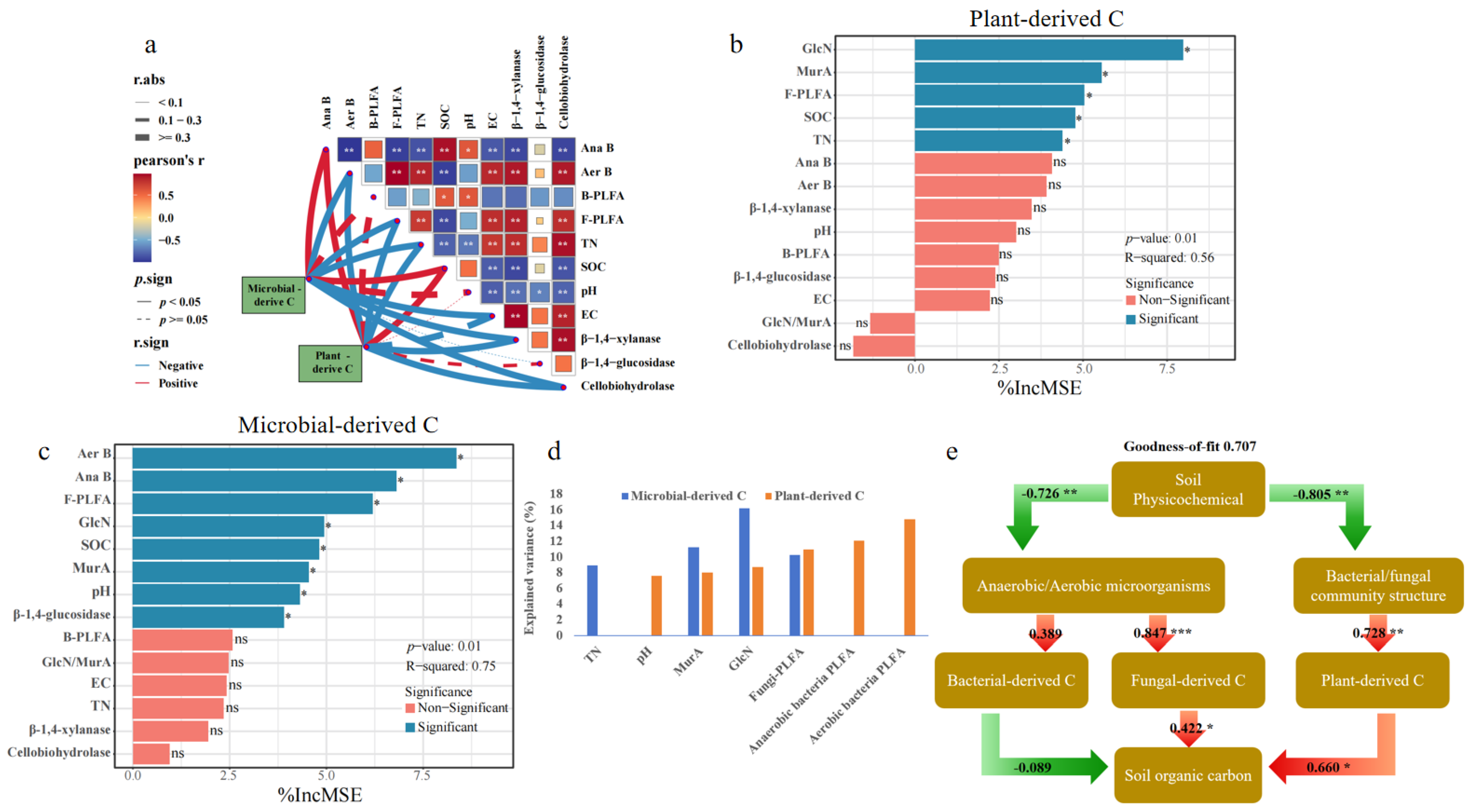

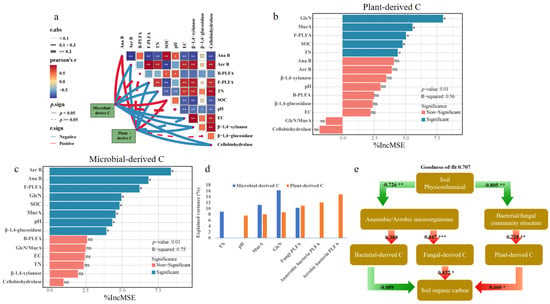

Eleven variables reflecting the effects of living microbe, extracellular enzymes, and soil basic properties (Figure S1) were used to explain the dynamics of plant- and microbial-derived C. Correlation analysis revealed that SOC concentration was positively related to both microbial- and plant-derived C (Figure 5a). Both plant- and microbial-derived C were negatively correlated with PLFAs of fungi and aerobic bacteria, while positively correlated with anaerobic bacterial PLFA (Figure 5a). Activities of both β-1,4-xylosidase and cellobiohydrolase showed the negative correlations with plant- and microbial-derived C. Among the soil properties, both TN concentration and EC were negatively related to plant- and microbial-derived C. These variables used in the random forest models explained 49.22% and 56.23% of the total variance of plant- and microbial-derived C during RSD, respectively. Plant-derived C accumulation was influenced by bacterial necromass (MurA, 8.03%), fungal necromass (GluN, 8.73%), soil chemical properties (pH, 7.62%), microbial PLFAs (fungi, 10.9%; anaerobic bacteria, 14.8%; aerobic bacteria, 12.1%), and extracellular enzymes (β-1,4-glucosidase, 6.92%) (Figure 5b,d). Bacterial (MurA, 11.2%) and fungal (GluN, 16.2%) necromass were responsible for bacterial-derived C dynamics, with soil TN (8.91%) and fungal PLFAs (10.2%) being key explanatory factors (Figure 5c,d). We further employed PLS-PM analysis to identify and quantify the linkages of SOC concentration to plant- and microbial-derived C and other variables (Figure 5e). Soil physicochemical characteristics had a direct impact on the bacterial/fungal community structure (path coefficient: −0.805; p < 0.01), which in turn exerted an indirect influence on plant-derived C (path coefficient: −0.609; p < 0.05) and SOC (path coefficient: 0.660; p < 0.05). Soil physicochemical characteristics directly affected the anaerobic/aerobic microorganisms (path coefficient: −0.726; p < 0.01), which in turn exerted an indirect influence on fungal-derived C (path coefficient: 0.847; p < 0.001) and SOC (path coefficient: 0.422; p < 0.05). The model accounts for 70.7% of the variance in SOC.

Figure 5.

Relationships between microbial-/plant-derived C and soil parameters (a,e) and their explained variance during reductive soil disinfestation as identified by the percentage increase in the mean squared error (MSE%) using random forests models (b–d). The following variables were included anaerobic bacteria (Ana B), aerobic bacteria (Aer B), fungal and bacterial (F-PLFA and B-PLFA), total N (TN). In the random forest model, * indicate p < 0.05, and ns indicates p > 0.05. The colors green and red indicate negative and positive effects, respectively. Path coefficients and coefficients of determination (R2) were calculated after 999 bootstraps, and significance levels are indicated by * (p < 0.05), ** (p < 0.01) and *** (p < 0.001). The goodness of fit (GoF) for the SOC was 0.707. Red arrows indicate positive correlations, and green arrows indicate negative correlations.

4. Discussion

In waterlogged soils, the enhancement of SOC stocks from straw return is facilitated by the constrained decomposition of substances and thus retention plant residue C, coupled with microbial succession and anoxia-induced shifts in metabolic activity [28]. In the present study, SOC concentration increased by 13–18% over the 35-day incubation period (Figure 3a), a result consistent with field-based observations reporting a 7.7% increase in SOC following RSD [10]. Notably, although SOC concentration exhibited only minor fluctuations from days 14 to 35 of RSD treatment, its constituent fractions derived from plant residues and microbial necromass displayed distinct dynamic patterns. These findings underscore the enhanced stability of the accumulated SOC under RSD, while also revealing that the dominant pathways of SOC formation undergo continuous shifts over time.

4.1. Dynamic of Soil Lignin Phenol and Plant-Derived C During RSD

Plant residues are key SOC precursors, with their incorporation enhancing plant-derived C (as lignin phenol) and thus increasing SOC [29]. Following RSD, soil Tlp concentration increased significantly within 14 days, indicating rapid conversion of added residues to plant-derived C (Figure 1 and Figure 3). A widely accepted fact is that lignocellulose requires depolymerization before conversion into plant-derived C [30]. Crop straw stimulates specific microorganisms to secrete extracellular enzymes for lignocellulose degradation, promoting plant-derived C compounds to soil minerals or within soil aggregates [24]. Residue incorporation typically stimulates soil lignocellulose-degrading enzymes under anoxia [31], consistent with a high cellobiohydrolase activity within 28 days, which suggested a continuously degradation of recalcitrant organic fraction in plant residues during RSD. Numerous studies have indicated that plant litter decomposition peaked within 3–7 days across an optimal field and incubation soil conditions, aligning with maximum enzyme activities [32]. In the present study, the activities of β-1,4-glucosidase and -xylosidase decreased continuously during RSD (Figure 4). Additionally, polynomial regression analysis indicated that the rapid breakdown of lignocellulose occurred primarily between 2 h and 14 days, which favored the plant-derived C formation during early RSD.

After days 14, plant-derived C declined progressively likely due to microbial decomposition. Straw return promotes large aggregates and associated C stabilization via particle aggregation [2]. Plant-derived C is preferentially protected within macroaggregates and its loading decreases with the decreasing size of particle fractions [29], indicating greater microbial accessibility. During RSD, temperatures reaching 50 °C under anaerobic conditions weaken chemical bonds and soften lignocellulose, facilitating microbial breakdown of V-, C-, and S-type lignin units by thermophilic anaerobes [10,33]. The greater reduction in typically more recalcitrant C-type lignin during days 14–35 highlights RSD’s degradation capacity. Within 14 days, the skyrocketed S/V and (Ac/Al)V ratios indicated a potential chemical oxidation. Upon soil rewetting, rapidly activated microbes drive a substantial production of hydroxyl radicals, thereby chemically breaking down complex substances into simpler forms [34]. By mediating reactive oxygen species production that preferentially oxidizes recalcitrant SOC components with low H/C ratios, soil rewetting works synergistically with extracellular enzymes to drive SOC degradation [35]. Thereby, the reactive oxygen species produced by soil rewetting caused by RSD should be identified in future study, which is important to clarify SOC dynamic. After 14 days, continuous S/V decline and reduced (Ad/Al) ratios demonstrate progressive anaerobic decomposition of plant-derived C during RSD [36].

4.2. Dynamic of Soil Amino Sugar and Microbial-Derived C During RSD

Microbial necromass plays a critical role in SOC sequestration in terrestrial ecosystems [37]. In this study, amino sugar concentrations increased sharply within the first 14 days following RSD and subsequently stabilized, a trend consistent with the dynamics of microbial-derived carbon. These results indicate rapid microbial necromass accumulation and the high stability of microbial-derived C. Plant residues stimulate soil microbes to assimilate carbon into biomass, which is subsequently transformed into persistent necromass along with community succession [29]. Polynomial regression analysis indicated that the synthesis rates of plant residues C and microbial residues C exhibited the fastest increase before 14 d, which also demonstrates that the early stage represents a key period for SOC accumulation. Typically, bacteria dominate the initial phase of decomposition, leading to rapid accumulation of bacterial necromass, whereas fungi become more influential in later stages [38]. Bacterial taxa, particularly those sensitive to fresh substrate inputs, thrived under RSD due to the incorporation of organic amendments [18,39]. During RSD, the total concentration of bacterial PLFAs increased, accompanied by a rise in anaerobic bacterial PLFAs and a decline in aerobic bacterial PLFAs, reflecting rapid bacterial community succession. The MurA, a major and quantitatively significant component of bacterial necromass, accumulated rapidly during the initial 14 days of the experiment, likely triggered by a large-scale die-off of aerobic bacteria in response to abrupt soil environmental changes. The subsequent gradual decline in MurA may be attributed to the relatively higher decomposability of bacterial necromass [40]. This decline in fungal PLFAs was likely driven by their high susceptibility to anaerobic stress, a response well reflected by the concurrent, substantial accumulation of the key fungal necromass constituents, GlcN and GalN (Figure 4). After this initial phase, both GlcN and GalN concentrations remained stable, underscoring the high biochemical stability of fungal residues. Two key mechanisms may explain the differential dynamics of bacterial and fungal necromass during RSD. First, bacterial residues primarily consist of discrete cells rich in peptidoglycan, whereas fungal residues form filamentous networks enriched with chitin [29]. The latter exhibits superior chemical and structural recalcitrance, leading to a slower decomposition rate. Second, the degradability of organic materials is closely linked to their C/N ratio [41]. Bacterial residues have a lower C/N ratio from 3 to 5 compared to fungal residues (>10), making their N more readily mineralizable. This facilitates microbial N availability without inducing immobilization, thereby accelerating bacterial necromass decomposition [42]. Together, these mechanisms support the observed pattern of an initial rise and subsequent decline in bacterial-derived C, contrasted with a steady accumulation of fungal-derived C during RSD (Figure 3).

4.3. Contribution of Plant- and Microbial-Derived C to SOC and Environmental Controls During RSD

By tracing plant and microbial residues, we demonstrated that RSD increased the combined contribution of microbial- and plant-derived carbon to SOC by 8.28–11.3% (Figure 3f), consistent with the overall SOC accumulation. Microbial-derived C contributed more (23.5–28.2%) than plant-derived C (18.1–25.0%) during RSD, though both were lower than values reported in paddy soils (28–36% and 35–54%), respectively [20,43]. Based on 13C labeling, microbial necromass had a mean residence time of 13.1 years, which was over twice shorter than plant litter [44], consistent with the faster decay of bacterial necromass observed here because of its higher decomposability than fungal residues. Climatic factors, particularly elevation, strongly influenced the microbial community structure and activity by regulating soil temperature and moisture, thereby affecting decomposition of both plant- and microbial-derived C [45]. In this study, the controlled anaerobic conditions created by RSD favored bacterial activity and enhanced the degradation of plant and microbial residues compared to typical paddy soil environments.

PLS-LM analysis further confirmed that soil physicochemical properties (i.e., pH and TN) significantly influenced the formation of fungal-derived C by regulating variations in the abundances of anaerobic/aerobic bacteria, as well as plant-derived C by modulating the abundances of bacteria/fungi (Figure 5e). This can be partly attributed to the preferential promotion of bacterial growth over fungal growth under higher pH conditions, thereby reducing fungal biomass and facilitating the incorporation of fungal necromass into stable SOC pools. Furthermore, plant-derived C was closely linked to the living biomass of soil bacteria and fungi, which itself was strongly associated with increased soil pH [45]. Previous studies have demonstrated that soil pH is a primary determinant of global soil microbial community structure, particularly driving bacterial community succession [46]. In the present study, the rise in pH supported the proliferation of anaerobic bacteria, which enhanced the anaerobic depolymerization of lignocellulose and contributed to the formation of plant-derived C. Moreover, higher pH values are indicative of weaker soil weathering and are generally associated with a greater abundance of pedogenic minerals such as montmorillonite, calcite, and illite [47]. These minerals contribute to the physicochemical protection of plant-derived carbon, promoting its persistence within the soil matrix [48]. Soil TN was identified as another key factor governing the formation of microbial-derived C, largely due to the relatively constrained C/N ratio characteristic of microbial biomass and necromass [49]. Nitrogen availability directly influences microbial growth and metabolic activity, thereby regulating the decomposition of plant residues [50]. During the initial phase of RSD, abundant N stimulated the succession of bacterial communities from aerobic to anaerobic taxa, enhancing the release of extracellular enzymes and thus facilitating the formation of plant-derived C. As the process continued, nitrogen limitation likely accelerated the degradation of nitrogen-rich bacterial necromass, favoring the relative retention of plant- and fungal-derived carbon in the SOC pool (Figure 3). Overall, throughout the RSD process, the observed increase in soil pH and decrease in TN collectively enhanced the contribution of plant and fungal residues to SOC sequestration, while simultaneously diminishing the role of bacterial necromass. In addition, the estimation of microbial necromass C in this study is based on well-established amino sugar biomarkers. However, the PLFA data were not used to explicitly partition the contributions of specific microbial taxa (e.g., Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria) to microbial necromass C. Although amino sugar biomarkers enabled this study to accurately characterize the temporal dynamics of plant and microbial necromass C and their contributions to the SOC pool, future research should integrate PLFA and other community functional indicators to more precisely elucidate the differential roles of distinct microbial groups in soil C sequestration, thereby deepening our understanding of the microbial C pump mechanism.

5. Conclusions

The dynamics of plant lignin and microbial necromass during RSD revealed a distinct temporal pattern in SOC accumulation. In the initial 14 days of RSD, the concentration of plant-derived C showed a marked increase, followed by a gradual decline until day 35. In contrast, microbial-derived C exhibited rapid accumulation during the first 14 days and subsequently stabilized until the end of the experimental period. Notably, while the contributions of both plant- and bacterial-derived C to SOC progressively decreased over time, fungal-derived C maintained a stable contribution after the initial 14 days. These results demonstrate that the early-phase SOC increase under RSD was driven by the combined accumulation of plant lignin and microbial necromass, whereas fungal necromass played a predominant role in sustaining SOC stabilization in the later stages. To our knowledge, this study provides the first comprehensive assessment of the temporal dynamics of plant- and microbial-derived C, highlighting the more critical role of fungal necromass in SOC persistence compared to plant lignin and bacterial necromass during RSD. These findings offer valuable insights into the mechanisms of SOC sequestration, emphasizing the importance of fungal necromass in SOC stabilization when RSD is employed for soil degradation remediation. However, given the inherent limitations of microcosm experiments, further validation is essential to confirm these observations through field-based studies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy16030351/s1, Figure S1: Changes in soil TN, pH, and EC during reductive soil disinfestation. Different lowercase letters denote significant differences between soil treatments for each parameter. Error bars represent standard errors (n = 3).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Y. and T.X.; methodology, J.Y.; software, X.W.; validation, Z.L.; formal analysis, P.S.; investigation, Y.Y.; resources, Z.L.; data curation, P.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Y. and X.W.; writing—review and editing, Y.C. and T.X.; visualization, J.Y. and T.X.; supervision, Y.Y.; project administration, Y.C. and T.X.; funding acquisition, Z.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Natural Science Basic Research Program of Shaanxi Province [2024JC-YBQN-0282], Technology Innovation Center for Land Engineering and Human Settlements, Shaanxi Land Engineering Construction Group Co., Ltd. and Xi’an Jiaotong University [2024WHZ2045], Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities [G2022KY05101] and Research and Development of Microorganism Fertilizer (Special project for ecology in Shaanxi Province: Grant No. 202202).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lal, R. Soil carbon sequestration impacts on global climate change and food security. Science 2004, 304, 1623–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.L.; Shar, A.G.; Li, S.; Chen, Y.L.; Shi, J.L.; Zhang, X.Y.; Tian, X.H. Effect of straw return mode on soil aggregation and aggregate carbon content in an annual maize wheat double cropping system. Soil Tillage Res. 2018, 175, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.W.I.; Torn, M.S.; Abiven, S.; Dittmar, T.; Guggenberger, G.; Janssens, I.A.; Kleber, M.; Kögel-Knabner, I.; Lehmann, J.; Manninget, D.A.C.; et al. Persistence of soil organic matter as an ecosystem property. Nature 2011, 478, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanderman, J.; Hengl, T.; Fiske, G.J. Soil carbon debt of 12,000 years of human land-use. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 9575–9580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delang, C.O. The consequences of soil degradation in China: A review. GeoScape 2018, 12, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, H.A.; Yuan, S.; Gao, W.; Tan, J.W.; Li, R.N.; Zhang, H.Z.; Huang, S.W. Changes in organic c stability within soil aggregates under different fertilization patterns in a greenhouse vegetable field. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 2758–2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, F.; Rao, D.; Yu, H.Y.; Han, Y.L.; Pan, G.W.; Hu, Z.S.; Teng, Y.; Lyu, F.; Yan, P.; Yang, H.; et al. Reductive soil disinfestation to improve soil properties in long-term tobacco cultivation. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2023, 12, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.L.; Liu, X.D.; Zhang, Z.R.; Shao, J.L.; Gao, Z.G.; Huang, Y.F. Effect of reductive soil disinfestation on melon fusarium wilt and soil metabolomics. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 23571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueki, A.; Kaku, N.; Ueki, K. Role of anaerobic bacteria in biological soil disinfestation for elimination of soil-borne plant pathogens in agriculture. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 6309–6318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.L.; Zhang, Y.H.; Li, C.; Xu, R.S.; Pei, Z.R.; Li, F.C.; Wu, Y.H.; Chen, F.; Liang, Y.R.; Li, Z.H.; et al. Linking soil organic carbon dynamics to microbial community and enzyme activities in degraded soil remediation by reductive soil disinfestation. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 189, 104931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.L.; Zhang, Y.H.; Xu, R.S.; Song, J.X.; Chen, A.L.; Chen, F.; Liang, Y.R.; Guo, D.; Tang, X.; Qin, Z.M.; et al. Short-term responses of soil organic carbon and chemical composition of particle-associated organic carbon to anaerobic soil disinfestation in degraded greenhouse soils. Land Degrad. Dev. 2023, 34, 4428–4440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.F.; Jackson, R.D.; DeLucia, E.H.; Tiedje, J.M.; Liang, C. The soil microbial carbon pump: From conceptual insights to empirical assessments. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 6032–6039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, C.; Schimel, J.P.; Jastrow, J.D. The importance of anabolism in microbial control over soil carbon storage. Nat. Microbiol. 2017, 2, 17105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, C.; Amelung, W.; Lehmann, J.; Kästner, M. Quantitative assessment of microbial necromass contribution to soil organic matter. Glob. Chang Biol. 2019, 25, 3578–3590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whalen, E.D.; Grandy, A.S.; Sokol, N.W.; Keiluweit, M.; Ernakovich, J.; Smith, R.G.; Frey, S.D. Clarifying the evidence for microbial- and plantderived soil organic matter, and the path toward a more quantitative understanding. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 7167–7185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.J.; Yan, J.T.; Wang, X.W.; She, P.T.; Li, Z.H.; Xu, R.S.; Chen, Y.L. Insights for soil improvements: Unraveling distinct mechanisms of microbial residue carbon accumulation under chemical and anaerobic soil disinfestation. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhou, X.; Jiang, A.Q.; Fan, J.Z.; Lan, T.; Zhang, J.B.; Cai, Z.C. Distinct impacts of reductive soil disinfestation and chemical soil disinfestation on soil fungal communities and memberships. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 7623–7634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, T.Z.; Yang, Y.J.; Cai, Z.C.; Ma, Y. The control of Fusarium oxysporum in soil treated with organic material under anaerobic condition is affected by liming and sulfate content. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2018, 54, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokol, N.W.; Bradford, M.A. Microbial formation of stable soil carbon is more efficient from belowground than aboveground input. Nat. Geosci. 2019, 12, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.B.; Hu, Y.J.; Xia, Y.H.; Zheng, S.M.; Ma, C.; Rui, Y.C.; He, H.B.; Huang, D.Y.; Zhang, Z.H.; Ge, T.D.; et al. Contrasting pathways of carbon sequestration in paddy and upland soils. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 2478–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokol, N.W.; Whalen, E.D.; Jilling, A.; Kallenbach, C.; Pett-Ridge, J.; Georgiouet, K. Global distribution, formation and fate of mineral-associated soil organic matter under a changing climate: A trait-based perspective. Funct. Ecol. 2022, 36, 1411–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, E.A.; Canedo, E.J.; Gomes, V.A.; Vieira, B.S.; Parreira, D.F.; Neves, W.S. Anaerobic soil disinfestation for the management of soilborne pathogens: A review. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2022, 174, 104408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.D. Soil Agricultural Chemical Analysis, 3rd ed.; China Agricultural Press: Beijing, China, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, W.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Gong, Q.L.; Zhai, B.N.; Li, Z.Y. Effects of cover crop in an apple orchard on microbial community composition, networks, and potential genes involved with degradation of crop residues in soil. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2018, 54, 743–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedges, J.I.; Ertel, J.R. Characterization of lignin by gas capillary chromatography of cupric oxide oxidation products. Anal. Chem. 1982, 54, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahri, H.; Rasse, D.P.; Rumpel, C.; Dignac, M.F.; Bardoux, G.; Mariotti, A. Lignin degradation during a laboratory incubation followed by 13C isotope analysis. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2008, 40, 1916–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Amelung, W. Gas chromatographic determination of muramic acid, glucosamine, mannosamine, and galactosamine in soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1996, 28, 1201–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Nakajima, T.; Mbonimpa, E.G.; Gautam, S.; Somireddy, U.R.; Kadono, A.; Lal, R.; Chintala, R.; Rafique, R.; Fausey, N. Long-term tillage and drainage influences on soil organic carbon dynamics, aggregate stability and corn yield. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2014, 60, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.T.; Zhang, X.C.; Li, Y.N.; Jiao, Y.P.; Fan, L.C.; Jiang, Y.J.; Qu, C.Y.; Filimonenko, E.; Jiang, Y.H.; Tian, X.H.; et al. Nitrogen fertilizer builds soil organic carbon under straw return mainly via microbial necromass formation. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2024, 188, 109223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angst, G.; Mueller, K.E.; Nierop, K.G.J.; Simpson, M.J. Plant-or microbial-derived? A review on the molecular composition of stabilized soil organic matter. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2021, 156, 108189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liang, C.; Wang, Y.Q.; Cheng, H.; An, S.S.; Chang, S.X. Soil extracellular enzyme stoichiometry reflects the shift from P-to N-limitation of microorganisms with grassland restoration. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 149, 107928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.L.; Yang, F.; Dong, J.J.; Shi, J.L.; Wang, S.X.; Zhao, H.L.; Zhou, L.Y.; Tian, X.H.; Wang, Y.H. Organic carbon mineralization and sequestration as affected by zn availability in a calcareous loamy clay soil amended with wheat straw: A short-term case study. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2020, 67, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, M.P.; Sánchez-Monedero, M.A.; Paredes, C.; Roig, A. Carbon mineralization from organic wastes at different composting stages during their incubation with soil. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 1998, 69, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Lu, Y.X.; Yang, J.G.; Du, F.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Yang, Y.H.; Yu, S.; Qin, S.P.; Fu, Q.L.; Rong, X.Y.; et al. Hydroxyl radical-driven oxidation as a key pathway for greenhouse gas production during soil drying-rewetting. Glob. Change Biol. 2025, 31, e70552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.H.; Zhu, K.C.; Wang, Z.Q.; Yang, H.Q.; Ni, Z.; Ding, Y.Y.; Zheng, Y.L.; Weng, J.Y.; Wang, Y.H.; Jia, H.Z. Abiotic processes dominate short-term carbon emissions in sandy soils following rewetting. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kögel, I. Estimation and decomposition pattern of the lignin component in forest humus layers. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1986, 18, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, X.Y.; Liu, J.J.; Liu, J.Y.; Han, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, H.Y.; Xu, M.P.; Yang, G.H.; Ren, C.J.; et al. The contribution of microbial necromass carbon to soil organic carbon in soil aggregates. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 190, 104985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, X.T.; Liu, J.X.; Liu, T.T.; Cheng, J.M.; Wei, G.H.; Lin, Y.B. Temporal and spatial succession and dynamics of soil fungal communities in restored grassland on the Loess Plateau in China. Land Degrad. Dev. 2019, 30, 1273–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.Q.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, J.B.; Cai, Z.C. Differential responses of soil bacterial community and functional diversity to reductive soil disinfestation and chemical soil disinfestation. Geoderma 2019, 348, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.R.; An, S.S.; Liang, C.; Liu, Y.; Kuzyakov, Y. Microbial necromass as the source of soil organic carbon in global ecosystems. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2021, 162, 108422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Ren, T.B.; Li, Y.S.; Chen, N.; Yin, Q.Y.; Li, M.S.; Liu, H.B.; Liu, G.S. Organic materials with high C/N ratio: More beneficial to soil improvement and soil health. Biotechnol. Lett. 2022, 44, 1415–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.J.; Cai, Y.H.; Wu, F.Z.; Zhang, J.Y.; Zhang, X.Y.; Ni, X.Y. Isotopic labeling evidence shows faster carbon release from microbial residues than plant litter. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 9, 104074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Morrissey, E.; Liu, Y.; Sun, L.; Qu, L.R.; Sang, C.P.; Zhang, H.; Li, G.C.; et al. Integrating microbial community properties, biomass and necromass to predict cropland soil organic carbon. ISME Commun. 2023, 3, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.B.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, X.M.; Chen, D.S.; Insam, H.; Koide, R.T.; Zhang, S.G. Effects of mixed-species litter on bacterial and fungal lignocellulose degradation functions during litter decomposition. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 141, 107690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.F.; Min, K.K.; Feng, K.; Xie, H.T.; He, H.B.; Zhang, X.D.; Deng, Y.; Liang, C. Microbial necromass contribution to soil carbon storage via community assembly processes. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 951, 175749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Redmile-Gordon, M.; Mortimer, M.; Cai, P.; Wu, Y.; Peacock, C.L.; Gao, C.H.; Huang, Q.Y. Extraction of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) from red soils (Ultisols). Soil Biol. Biochem. 2019, 135, 283–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.H.; Zhang, P.; He, C.; Yu, J.C.; Shi, Q.; Dahlgren, R.A.; Spencer, R.G.M.; Spencer, R.G.M.; Yang, Z.B.; Wang, J.J. Molecular signatures of soil-derived dissolved organic matter constrained by mineral weathering. Fundam. Res. 2022, 3, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newcomb, C.J.; Qafoku, N.P.; Grate, J.W.; Bailey, V.L.; De Yoreo, J.J. Developing a molecular picture of soil organic matter mineral interactions by quantifying organo-mineral binding. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ctrufo, M.F.; Ranalli, M.G.; Haddix, M.L.; Six, J.; Lugato, E. Soil carbon storage informed by particulate and mineral associated organic matter. Nat. Geosci. 2019, 12, 989–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.L.; Zhang, L.Y.; Li, J.; Huang, S.Y.; Wang, S.Y.; Zhao, Y.Z.; Zhou, W.; Ai, C. Nitrogen-shaped microbiotas with nutrient competition accelerate early-stage residue decomposition in agricultural soils. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 5793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.