Abstract

Slug herbivory is an important but poorly explored driver of plant defence and belowground multitrophic interactions. This study examined how aboveground feeding by Arion vulgaris and Deroceras reticulatum affects oxidative status, photosynthetic pigments, and volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions in cabbage (Brassica oleracea L. var. capitata), and whether these changes influence slug-parasitic nematodes. Slug feeding induced strong oxidative stress in leaves and roots, reflected by depletion of total ascorbate and glutathione contents and increased proportions of their oxidized forms, indicating a systemic redox imbalance. Photosynthetic pigments were also markedly affected, characterized by decreased chlorophylls and carotenoids and activation of the xanthophyll cycle towards more zeaxanthin, particularly in plants attacked by D. reticulatum. Headspace SPME–GC–MS analysis revealed tissue-specific, herbivory-induced shifts in VOC profiles. Based on these changes, three VOCs—3-phenylpropionitrile, allyl isothiocyanate, and 2-hexenal—were selected for chemotaxis assays. Behavioural experiments showed that VOC identity and nematode species markedly influenced motility and chemotactic responses. Phasmarhabditis papillosa exhibited the strongest attraction to 3-phenylpropionitrile, whereas allyl isothiocyanate acted as a weak repellent to P. papillosa, Oscheius myriophilus, and Oscheius onirici. In contrast, 2-hexenal elicited no consistent directional response. These results demonstrate that slug herbivory alters cabbage metabolism and volatile signalling, shaping species-specific nematode behaviour and highlighting its potential for sustainable slug management.

1. Introduction

Slugs are among the most damaging pests in European vegetable production, particularly in moist and temperate climates, where the Spanish slug (Arion vulgaris Moquin-Tandon) and the grey field slug (Deroceras reticulatum [Müller]) frequently cause severe losses in cabbage and other Brassica crops [1]. Control of these molluscs still relies mainly on metaldehyde and iron(III) phosphate baits, but metaldehyde contaminates aquatic ecosystems and poses risks to pets, wildlife, and earthworms [2]. Its use is therefore being restricted across the EU, increasing the need for environmentally safe alternatives. Biological control using slug-parasitic nematodes (SPNs), especially Phasmarhabditis hermaphrodita (Schneider) and related species, represents a promising strategy [3]. Improving the ecological performance of SPNs requires a deeper understanding of chemical cues that guide nematode movement in soil.

Plants under herbivore attack often emit volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that function as indirect defences by attracting predators or parasitoids of herbivores [4,5]. While early research focused on aboveground interactions, roots are in particular crucial for releasing VOCs that mediate plant–herbivore–nematode communication belowground [6,7]. Such VOCs may act as attractants, repellents, or toxicants and influence the foraging behaviour of soil-dwelling organisms, including parasitic nematodes [6]. Accurate identification of these compounds typically requires GC–MS combined with preconcentration approaches such as solid-phase microextraction (SPME) [6].

Systemic plant responses to herbivory include changes in the ascorbate–glutathione (ASC–GSH) cycle, which is central to cellular redox balance and detoxification of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [8,9]. The concentrations and redox states of ascorbate (ASC/dehydroascorbate) and glutathione (GSH/glutathione disulfide) are widely used indicators of oxidative stress [8]. Herbivory-induced oxidative pressure is also reflected in pigment changes, especially alterations in chlorophylls and carotenoids that contribute to photoprotection [10]. Although the ASC–GSH cycle is well documented in plant–insect systems, its relevance in plant responses to molluscan herbivory remains largely unknown. Unlike insect herbivory, molluscan feeding is characterized by extensive tissue abrasion, mucus deposition, and prolonged contact with plant surfaces, which may elicit distinct oxidative and chemical signalling responses.

Cabbage (Brassica oleracea L. var. capitata) is a representative Brassicaceae crop rich in sulphur-containing glucosinolates. Upon cell disruption, these compounds are hydrolysed by the endogenous enzyme myrosinase to produce isothiocyanates, nitriles, and other biologically active metabolites that contribute to defence against herbivores and pathogens [11]. Slugs feeding on Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. efficiently detoxify glucosinolate breakdown products by conjugating them with GSH via the mercapturic acid pathway, highlighting a strong biochemical interplay between molluscs and Brassicaceae secondary metabolism [12]. Sulphur-induced resistance (SIR), achieved through sulphate fertilization, has been associated with increases in thiols, glucosinolates and enhanced resistance to harmful organisms in Brassicaceae [13], though its impact on slug–plant–nematode interactions remains unexplored.

Recent work has shown that root VOCs induced by insect attack or mechanical damage can strongly influence the chemotaxis of both entomopathogenic and slug-parasitic nematodes. In Lactuca sativa L., root herbivory altered the ASC–GSH system and changed volatile emissions, with certain metabolites acting as nematode attractants or repellents [14]. In Brassica nigra (L.) K. Koch, sulphur-containing volatiles and glucosinolate breakdown products, including allyl isothiocyanate, sulphur volatiles, and aromatic nitriles, significantly shaped the behaviour of Phasmarhabditis papillosa Schneider, Oscheius myriophilus (Poinar), and O. onirici Torrini. Related research with synthetic Brassica volatiles further supports their importance for nematode navigation [15,16]. Slug-parasitic nematodes such as Phasmarhabditis spp. infect their hosts through natural openings or the body surface, release symbiotic bacteria that contribute to host mortality, and complete their development within the slug cadaver [3]. Host-seeking and infection efficiency depend strongly on chemical cues in the soil environment, making plant-derived volatiles potentially important mediators of these interactions. However, no study has investigated whether aboveground feeding by slugs, rather than insect herbivores, induces comparable belowground chemical signalling in cabbage.

Thus, key knowledge gaps remain regarding (i) whether slug feeding induces systemic antioxidative changes in cabbage, (ii) whether aboveground damage alters VOC profiles of leaves and roots, and (iii) whether slug-parasitic nematodes respond behaviourally to cabbage-specific volatiles such as aromatic nitriles (e.g., 3-phenylpropionitrile), isothiocyanates (e.g., allyl isothiocyanate) and green leaf volatiles (e.g., 2-hexenal).

In this study, we examined how slug feeding on the aboveground parts of B. oleracea var. capitata affects (i) the ASC–GSH system and photosynthetic pigments in leaves and roots, (ii) VOC emission profiles in shoots and roots, and (iii) chemotactic responses of three slug-parasitic nematodes (P. papillosa, O. myriophilus, and O. onirici) to selected cabbage-derived VOCs. We hypothesized that slug herbivory induces oxidative and sulphur-related metabolic shifts that modify cabbage volatile emissions and produce chemical cues that may enhance or inhibit SPN attraction.

By integrating plant physiology and antioxidant responses, analytical chemistry for volatile organic compound profiling, and nematode behaviour, this work identifies volatile metabolites with potential for improving semiochemical-based biological control strategies against slugs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Greenhouse Experiment, Slug Infestation, and Plant Sampling

In May 2024, a greenhouse experiment was established using 30 seedlings of cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata, cv. ‘Green Pearl 6640 F1’; Eurogarden d.o.o.). Each seedling was transplanted into a 3 L pot filled with Bio Plantella Universal substrate (Unichem d.o.o., Sinja Gorica, Slovenia). The experiment was conducted in a heated greenhouse at the Biotechnical Faculty, University of Ljubljana (Slovenia), where daytime conditions were maintained at 21 °C (RH 55%) and night-time conditions at 11 °C (RH 75%). Plants were watered every four days.

A total of 40 slugs were hand-collected from the grounds of the Biotechnical Faculty (46°04′ N, 14°31′ E; 299 m a.s.l.) and identified to species level using standard morphological keys [1]. The collection consisted of 20 Spanish slugs (A. vulgaris) and 20 grey field slugs (D. reticulatum). Ten cabbage plants were infested with A. vulgaris (two individuals per pot), ten with D. reticulatum (two individuals per pot), while the remaining ten pots served as uninfested controls. Following infestation, all pots were placed individually into Collapsible Insect Mesh Cages (model CIMC-WHT-SM; size 12 × 12 × 12 in; RSC; China International Marine Containers [CIMC], Shenzhen, China), which provide fine-mesh containment, a transparent viewing window, and a zipper opening, allowing controlled herbivory while preventing slug escape. Slug feeding was allowed to proceed freely for a fixed three-day period, and feeding damage was not quantified by leaf area removal but was visually confirmed on all infested plants.

The experiment concluded in June 2024 with the collection of plant material. From each pot, approximately 20 g of leaf tissue and 10 g of root tissue were harvested for biochemical and analytical procedures. Sampling followed the protocol of Tausz et al. [17], with minor modifications, including the use of freeze-dried material, adjusted sample mass, and modified extraction and centrifugation conditions. Plant material was collected on a clear, sunny day between 11:00 and 14:00 solar time to minimize diel variation in metabolite levels. Entire plants were carefully removed from the pots, and leaves and roots were separated and placed into individual paper sampling bags. Roots were briefly rinsed with distilled water to remove adhering soil. All samples were immediately placed on dry ice and subsequently stored at −80 °C.

Frozen tissues were freeze-dried using a Lyophilizer Alpha (Christ, Osterode am Harz, Germany) and homogenized to a fine powder with a TissueLyser II (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) prior to further biochemical analyses. The biochemical, pigment, and VOC analyses were conducted using ten biological replicates per treatment (n = 10 plants), with each biological replicate analysed for the full set of biochemical parameters.

2.2. Determination of Total and Reduced Ascorbic Acid

The contents of total ascorbic acid (tASC) and reduced ascorbic acid (rASC) were determined following the method of Tausz et al. [17], with slight modifications, including adjusted sample mass and extraction volumes. For each sample, 30 mg of freeze-dried plant material was weighed into glass tubes containing 3 mL of metaphosphoric acid (3%) and 60 mg of polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP, added 24 h in advance). Subsequently, samples were vortexed for 40 s and centrifuged for 15 min at 2800 rpm at 4 °C.

For quantification of tASC, 600 μL of the supernatant extract was transferred into dark microcentrifuge tubes, followed by the addition of 280 μL of 0.4 M TRIS buffer and 50 μL of 0.26 M dithiothreitol (DTT) solution. After vortexing, samples were incubated for 10 min in the dark on an orbital shaker to allow the reduction of dehydroascorbic acid (DHA). The reaction was terminated by adding 100 μL of orthophosphoric acid. Samples were vortexed again and centrifuged for 45 min at 12,000 rpm at 4 °C. The resulting supernatant was filtered through 0.45 μm PTFE syringe filters and transferred into HPLC vials for chromatographic analysis.

To quantify rASC, 600 μL of the extract was pipetted into dark microcentrifuge tubes, followed by 280 μL of 0.4 M TRIS buffer and 50 μL of double-distilled water. After vortexing, samples were incubated for 10 min in the dark on an orbital shaker. The reaction was stopped by adding 100 μL of orthophosphoric acid, vortexed briefly, and centrifuged for 45 min at 12,000 rpm at 4 °C. Supernatants were filtered through 0.45 μm PTFE filters and transferred into HPLC vials prior to analysis.

ASC was quantified using a modified isocratic reversed-phase HPLC method. Analyses were carried out on an HPLC Waters Alliance 2695 system equipped with a 2996 photodiode array (PDA) detector (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA). Separation was performed on a Phenomenex Synergy Hydro-RP 80 Å column (4 μm, 150 × 4.6 mm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA). The mobile phase consisted of 32.5 mM NaH2PO4 adjusted to pH 2.2, delivered isocratically at a flow rate of 0.5 mL min−1. Detection was set at 250 nm, and the total run time was 20 min. The identification of tASC and rASC was confirmed by comparing the retention time of the sample peak with the retention times of the standard peak (the standard was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, Hamburg, Germany). The standard curve covered the concentration range from 416 nmol/mL to 2489 nmol/mL ASC. The standards were prepared using the same procedure as the samples in which the tASC content was determined.

2.3. Extraction and Determination of Low-Molecular-Weight Thiols and Disulfides

The concentrations of cysteine, total glutathione (tGSH), and their oxidized forms—cystine and glutathione disulfide (GSSG)—were determined according to Kranner and Grill [18], with minor modifications. Freeze-dried plant material (40 mg) was weighed into glass tubes containing 60 mg of PVP and 2 mL of 0.1 M HCl (added 24 h in advance). Samples were vortexed for 40 s and centrifuged for 15 min at 2800 rpm and 4 °C, and the resulting supernatant was used for thiol and disulfide analysis.

For the determination of cysteine and tGSH, 400 μL of the extract was mixed with 600 μL of CHES buffer (pH 9.0) and 70 μL of 5 mM DTT. Samples were vortexed and incubated for 60 min in the dark. Then, 50 μL of 8 mM monobromobimane (mBBr) was added, followed by vortexing and an additional 15 min incubation in darkness. The reaction was terminated with 600 μL of 0.25% methanesulfonic acid. Samples were centrifuged for 45 min at 12,000 rpm at 4 °C, and the supernatants were transferred into dark HPLC vials. For oxidized thiols (cystine and GSSG), 400 μL of extract was combined with 600 μL of CHES buffer (pH 9.0) and 30 μL of 300 mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) to block free thiols. After vortexing, samples were incubated for 15 min in the dark. Excess NEM was removed by washing three times with 500 μL of toluene, each followed by vortexing and centrifugation (5 min, 3000 rpm). A 500 μL aliquot of the washed extract was then mixed with 50 μL of 5 mM DTT and incubated for 60 min in the dark. Subsequently, 30 μL of 8 mM mBBr was added, and samples were incubated for 15 min in the dark. The reaction was stopped with 430 μL of 0.25% methanesulfonic acid, centrifuged for 45 min at 12,000 rpm at 4 °C, and transferred to HPLC vials.

Thiols and disulfides were quantified using a Waters Alliance 2695 HPLC system equipped with a 2475 fluorescence detector (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA). Separation was performed on a Waters Grace Spherisorb ODS-2 column (2.5 μm, 250 × 4.6 mm). The mobile phase consisted of solvent A (double-distilled water with 5% methanol and 0.25% acetic acid, pH 3.9) and solvent B (90% methanol with 0.22% acetic acid, pH 3.9). The gradient elution program was: 0–20 min, 90% A/10% B; 20–30 min, 85% A/15% B; 30–35 min, 5% A/95% B; and 35–40 min, 90% A/10% B. The flow rate was set to 1.0 mL min−1, and the total run time was 40 min. The identification of cysteine, cystine, GSH, and GSSG was confirmed by comparing the retention times of the peaks of the samples with the retention times of the peaks of the cysteine and GSH standards (both standards were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, Germany). The cysteine standard curve covered the range from 1.42 nmol/mL to 19.88 nmol/mL, and the GSH standard curve covered the range from 2.79 nmol/mL to 39.18 nmol/mL. The standards were prepared according to the same procedure as the samples in which the cysteine and tGSH contents were determined.

2.4. Extraction and Determination of Photosynthetic Pigments

Photosynthetic pigments were extracted following the method of Tausz et al. [17] with minor modifications. Freeze-dried plant material (30 mg) was weighed into glass tubes, and 3 mL of 70% (v/v) acetone was added. Samples were vortexed for 40 s and centrifuged for 15 min at 2800 rpm at 4 °C. The supernatant was transferred to clean tubes, and the extraction procedure was repeated twice by adding an additional 3 mL of 70% acetone to the pellet, followed by vortexing and centrifugation. The supernatants from all three extraction steps were pooled and centrifuged again for 45 min at 2800 rpm at 4 °C to remove residual particulates. Aliquots for HPLC analysis were transferred into dark amber vials, while the remaining extracts were used for spectrophotometric quantification.

Chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, antheraxanthin, neoxanthin, violaxanthin, and zeaxanthin were separated and quantified using HPLC according to Tausz et al. [17]. Analyses were performed on a Waters Alliance 2695 system equipped with a 2996 photodiode array (PDA) detector. Pigments were separated on a Phenomenex SphereClone column (5 μm, 250 × 4.6 mm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) under a flow rate of 1.0 mL min−1 with a total run time of 35 min. Detection was carried out at 440 nm. The mobile phases consisted of solvent A (acetonitrile–doubly distilled water–methanol, 100:10:5, v/v/v) and solvent B (acetone–ethyl acetate, 2:1, v/v). The gradient elution program started at 10% B, increased linearly to 80% B within 17 min, was held for 5 min, and then returned to initial conditions over 5 min. The identification of chlorophylls (chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b) and xanthophylls (neoxanthin, lutein, violaxanthin, antheraxanthin, and zeaxanthin) was confirmed by comparing the retention times of the sample peaks with the retention times of the chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and xanthophyll standards (all standards were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, Germany). The chlorophyll a standard curve covered the range from 10 mg/L to 30 mg/L, the chlorophyll b standard curve covered the range from 4.17 mg/L to 12.5 mg/L, and the xanthophyll standard curve covered the range from 1 mg/L to 3 mg/L. Neoxanthin, lutein, violaxanthin, antheraxanthin, and zeaxanthin were quantified in the equivalent of the related compound xanthophyll, because their standards were not available.

Total chlorophylls and total carotenoids were quantified spectrophotometrically using a Varian Cary 50 Bio spectrophotometer (Varian, Palo Alto, CA, USA) following the method of Lichtenthaler and Buschmann [19]. Absorbance was measured at 470, 645, and 662 nm, and pigment concentrations were calculated using established extinction coefficients.

2.5. Headspace SPME–GC–MS Analysis of Volatile Organic Compounds

For VOC extraction, cabbage root or shoot tissues were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and finely ground using a pre-chilled ceramic mortar and pestle. Approximately 0.45–0.55 g of homogenized plant material was transferred into a 20 mL headspace vial, immediately sealed, and incubated at 50 °C for 30 min. The incubation temperature was selected based on preliminary trials showing the greatest differentiation in VOC profiles among control and herbivore-damaged plants. During incubation, a solid-phase microextraction (SPME) fibre coated with 100 μm polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS; Supelco, Bellefonte, PA, USA) was exposed to the headspace above the sample. Between analyses, the SPME fibre was conditioned in the GC inlet for 10 min to prevent analyte carryover.

Headspace VOCs were analysed using an Agilent 7890B gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany) coupled to an Agilent 5977B single-quadrupole mass spectrometer equipped with an electron ionization (EI) source. Separation was performed on a ZB-5HT-Inferno capillary column (5% diphenyl–95% dimethylpolysiloxane; 20 m × 0.18 mm i.d., 0.18 μm film thickness; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA). The oven temperature program started at 30 °C (5 min hold), followed by a ramp of 12 °C min−1 to 250 °C, with a final hold of 2 min. The injector was operated in splitless mode at 250 °C with a 200 kPa pressure surge lasting 1.5 min and was fitted with a dedicated 1 mm SPME glass liner (Supelco). Helium served as the carrier gas at a constant flow of 0.6 mL min−1. The transfer line temperature was maintained at 260 °C.

The EI ion source was operated at 230 °C with an ionization energy of 70 eV. Mass spectra were acquired over a scan range of 46–350 amu at a rate of 5 scans s−1. Chromatographic peaks were evaluated using Chromatographic peaks were evaluated using Agilent MassHunter Workstation Software (version B.07.00; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and compound identities were assigned based on mass spectral matching and retention characteristics. VOC data were evaluated semi-quantitatively based on relative peak areas rather than absolute concentrations normalized to internal standards.

2.6. Nematode Culturing, Maintenance, and Volatile Organic Compound Selection for Chemotaxis Assays

Native Slovenian populations of P. papillosa (GenBank: MT800511.1), O. myriophilus (GenBank: OP684306.1), and O. onirici (GenBank: PQ876382) were used in this study, as their presence in Slovenia has recently been confirmed [15]. Nematodes were propagated in vivo using freeze-killed Spanish slugs (A. vulgaris) as a host substrate. After a 10-day incubation period, infective juveniles (IJs) were isolated from the decomposed cadavers following a protocol adapted for slug-parasitic nematodes [15]. Briefly, cadaver material was homogenized, treated with 5% sodium hypochlorite to dissociate nematodes from host tissues, and subsequently rinsed twice with distilled water to remove residual debris.

Freshly extracted IJs were suspended in M9 buffer, an isotonic solution containing KH2PO4, Na2HPO4, NaCl, and NH4Cl, which is routinely used to maintain nematode viability and osmotic stability [15]. Nematode suspensions were stored at 4 °C until use. Prior to each experiment, viability was assessed by examining ~100 IJs under a stereomicroscope. Individuals were classified as viable if they displayed active movement, such as sinusoidal locomotion or twitching, when placed in a droplet of M9 buffer. Nematodes showing no movement or visible degeneration were considered non-viable. Only batches younger than two weeks and exhibiting >95% viability were used in chemotaxis assays to ensure consistent physiological performance.

Three volatile organic compounds (VOCs) were selected as test stimuli for chemotaxis trials based on the differential changes observed in our SPME–GC–MS analysis of cabbage tissues subjected to slug herbivory. Compounds were chosen according to the following criteria: (i) ecological relevance within Brassicaceae defence chemistry, (ii) consistent modulation by herbivore feeding, and (iii) reported or plausible involvement in belowground tritrophic interactions. The VOCs (obtained from Sigma–Aldrich, Germany) included the following:

(1) 3-phenylpropionitrile [3PPN] (PubChem CID: 7699), an aromatic nitrile produced via glucosinolate breakdown and strongly reduced in roots following A. vulgaris feeding;

(2) allyl isothiocyanate [AITC] (PubChem CID: 5971), a characteristic glucosinolate hydrolysis product whose emission decreased in the roots of both slug-infested treatments;

(3) 2-hexenal [2H] (PubChem CID: 5281168), a lipoxygenase-derived green-leaf aldehyde that was consistently lower in leaves of herbivore-damaged plants.

These compounds represent three major and biochemically distinct pathways of plant defence—the glucosinolate–nitrile pathway, the glucosinolate–isothiocyanate pathway, and the LOX-derived green-leaf volatile pathway [9]. All three showed strong, directionally consistent shifts in abundance following herbivore attack, suggesting that they may function as informative cues exploited by slug-parasitic nematodes during host-seeking. Each VOC was tested at a concentration of 0.03 ppm, corresponding to ecologically realistic levels commonly detected in the rhizosphere under biotic stress conditions [16].

2.7. Chemotaxis Assay

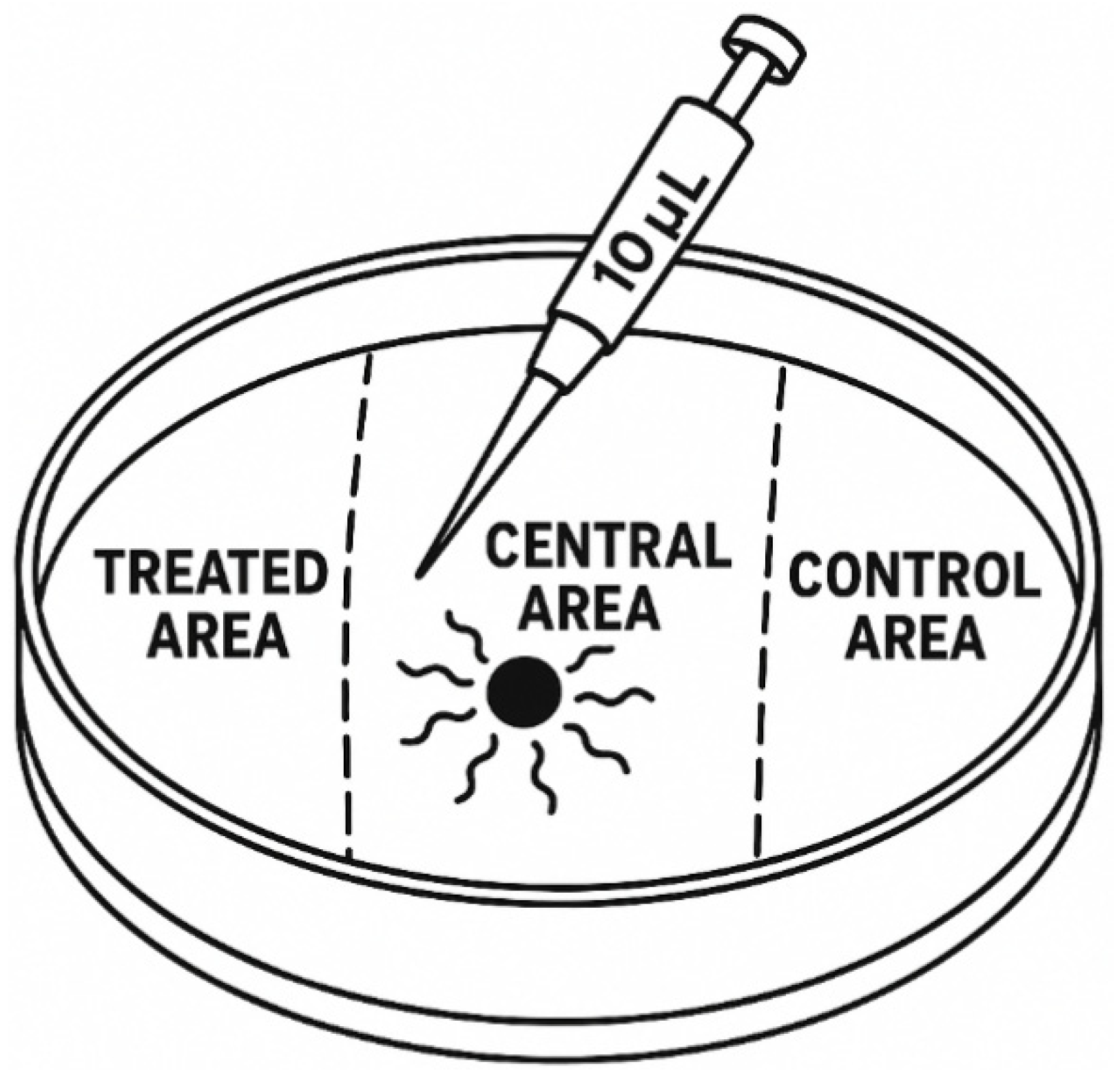

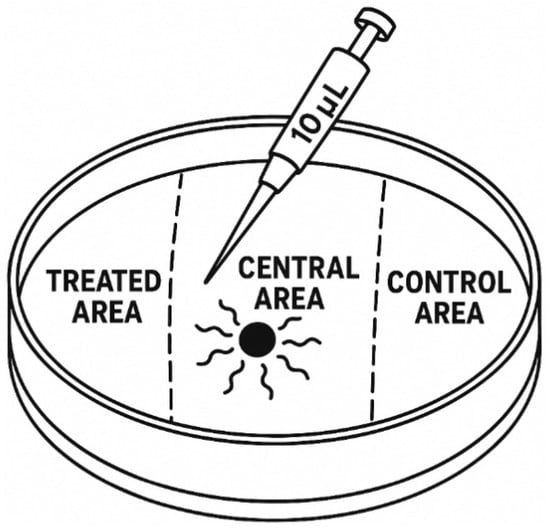

The chemotaxis assay was conducted following the protocol of Jagodič et al. [16], with modifications to suit slug-parasitic nematodes (Figure 1). Petri dishes (Ø 9 cm) were prepared with 25 mL of 1.6% technical agar (Biolife, Milan, Italy) containing 5 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0), 1 mM CaCl2, and 1 mM MgSO4. Each treatment consisted of ten replicates, and the full experiment was repeated three times to ensure reproducibility. To prevent volatile cross-contamination, only one VOC was tested per experimental series, and dishes were sealed with Parafilm™ (Bemis Company, Inc., Neenah, WI, USA) to confine the compound to the designated treatment zone.

Figure 1.

Experimental setup for chemotaxis assays. Each 9 cm polystyrene Petri dish was marked with three 1-cm reference zones on the underside: a central area located at the midpoint of the dish and two outer zones positioned 1.5 cm from the left and right edges (treated area and control area, respectively). For VOC treatments, 10 μL of the test compound was applied to the treated area, while 10 μL of 96% ethanol served as the solvent control in the control area. Afterward, 100 infective juveniles (IJs) suspended in 10 μL of M9 buffer were placed in the central area. In control assays, both the treated area and the control area received 10 μL of 96% ethanol to exclude VOC-driven chemotactic effects. This standardized layout ensured consistent spatial orientation and uniform application volumes across replicates, enabling accurate assessment of nematode behavioural responses.

All plates were placed in a climate-controlled chamber (RK-900 CH, Kambič Laboratory Equipment, Semič, Slovenia) set to 20 °C, 75% relative humidity, and complete darkness, representing belowground environmental conditions and minimizing unintended external cues. After a 24 h exposure period, plates were briefly transferred to −20 °C for 3 min to immobilize nematodes and preserve their positional distribution at the end of the assay.

Nematode distribution within the defined assay zones was quantified under a Nikon SMZ800N stereomicroscope (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a 4K UHD Multi-output HDMI Camera (XCAM4K8MPB) at 25× magnification. The chemotactic response was expressed using the Chemotaxis Index (CI), calculated according to Bargmann and Horvitz [20] and later adapted for nematode–VOC interactions by Jagodič et al. [16]:

CI = (% of IJs in the treated area − % of IJs in the control area)/100%

CI values ranged from 1.0 (indicating complete attraction) to −1.0 (indicating complete repulsion). Based on the calculated CI, compounds were classified as follows: attractants (CI ≥ 0.2), weak attractants (0.2 > CI ≥ 0.1), neutral (−0.1 ≤ CI < 0.1), weak repellents (−0.2 ≤ CI < −0.1), and repellents (CI ≤ −0.2) [16].

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Biochemical parameters (ASC forms, thiols, and related redox ratios) were analysed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with treatment (control, Arion vulgaris, and Deroceras reticulatum) as the fixed factor. Mean separation was performed using Duncan’s multiple range test, and differences were considered significant at p < 0.05. Data are presented as mean ± standard error (SE). Analyses were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Chemotaxis data were analysed at two levels. First, directional movement, defined as the proportion of infective juveniles migrating from the central area toward either the treated or control outer segments, was evaluated using ANOVA to test the effects of nematode species, VOC identity, and temporal and spatial replication. Second, chemotactic preference was quantified using the chemotaxis index (CI) [20] and analysed by ANOVA with nematode species, VOC identity, and their interaction as fixed effects; temporal and spatial replication were included as experimental factors. Following a significant ANOVA, mean separation for CI values was performed using Duncan’s multiple range test as an exploratory post hoc procedure (p < 0.05), consistent with our previous work [15]. Chemotaxis analyses were performed in Statgraphics Plus for Windows 4.0 (Statistical Graphics Corp., Rockville, MD, USA). Figures were prepared in Microsoft Excel 2010.

3. Results

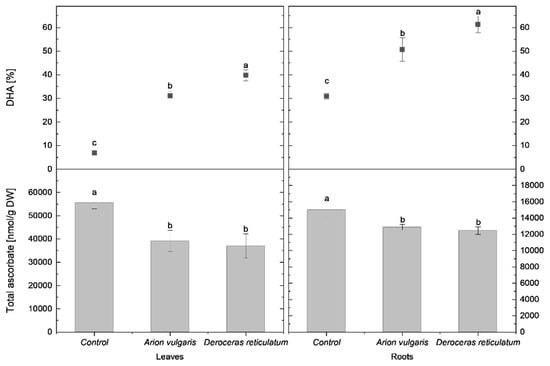

3.1. Effects of Slug Herbivory on Ascorbate Redox Status in Cabbage Leaves and Roots

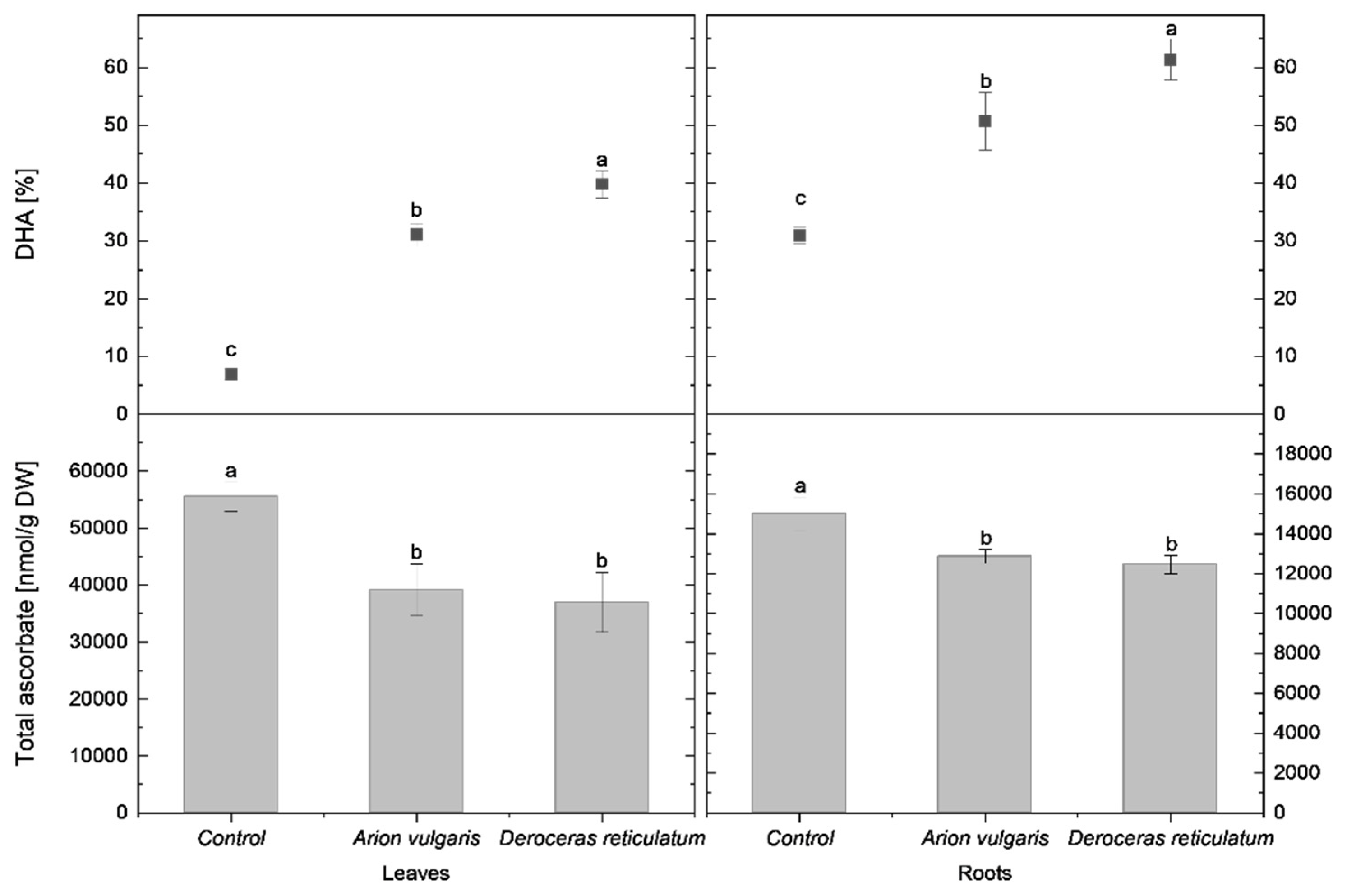

In control cabbage plants, tASC content in the leaves reached 55,520 nmol g−1 DW. This value was significantly lower in leaves of slug-infested cabbage, with concentrations decreasing to 39,143 nmol g−1 DW following A. vulgaris feeding and to 36,978.12 nmol g−1 DW after exposure to D. reticulatum. In parallel, the proportion of DHA differed significantly among all treatments. Control plants exhibited the lowest DHA proportion (7%), whereas leaves from plants infested by A. vulgaris and D. reticulatum showed markedly higher DHA levels (31% and 40%, respectively).

A similar but less pronounced reduction in total ascorbate was observed in the roots. Control plants contained 15,011 nmol g−1 DW of tASC, while roots of slug-infested cabbage showed significantly lower levels. Plants exposed to A. vulgaris contained 12,855 nmol g−1 DW, and those exposed to D. reticulatum contained 12,460 nmol g−1 DW. In contrast to tASC, DHA proportions in roots increased significantly in response to slug herbivory. The highest DHA proportion was detected in roots of plants infested by D. reticulatum (61%), followed by A. vulgaris (51%), whereas control plants exhibited a significantly lower DHA proportion (31%).

Detailed comparisons of tASC concentrations and DHA proportions in leaves and roots are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Total ascorbate content (nmol g−1 DW) and proportion of dehydroascorbate (DHA; % of total ascorbate) in the leaves and roots of control cabbage plants and plants infested by Arion vulgaris and Deroceras reticulatum. Bars represent mean values ± SE (n = 5). Different letters (a–c) indicate statistically significant differences among treatments (one-way ANOVA followed by Duncan’s multiple range test, p < 0.05).

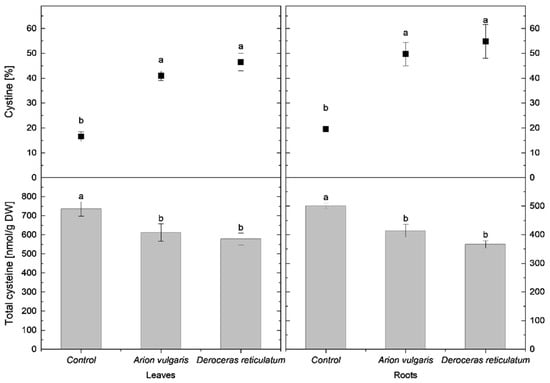

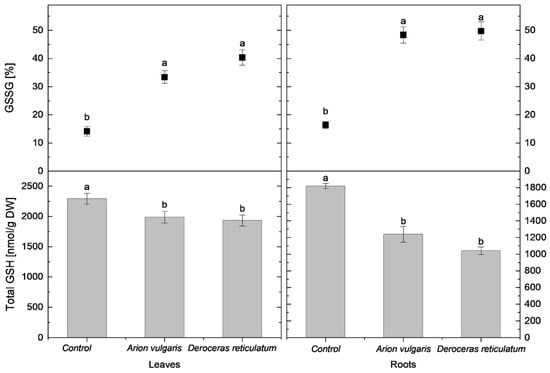

3.2. Effects of Slug Herbivory on Low-Molecular-Weight Thiols in Cabbage Leaves and Roots

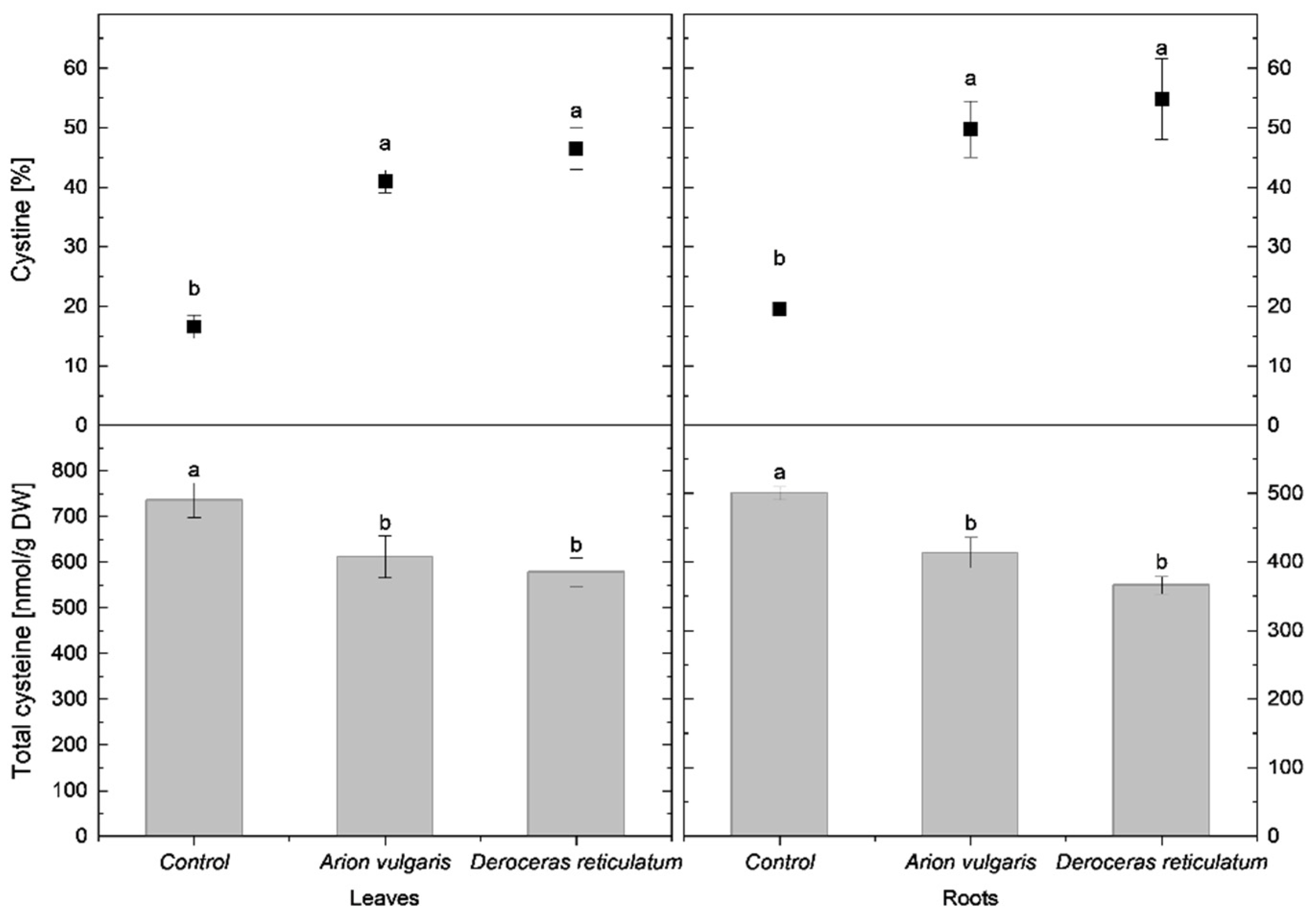

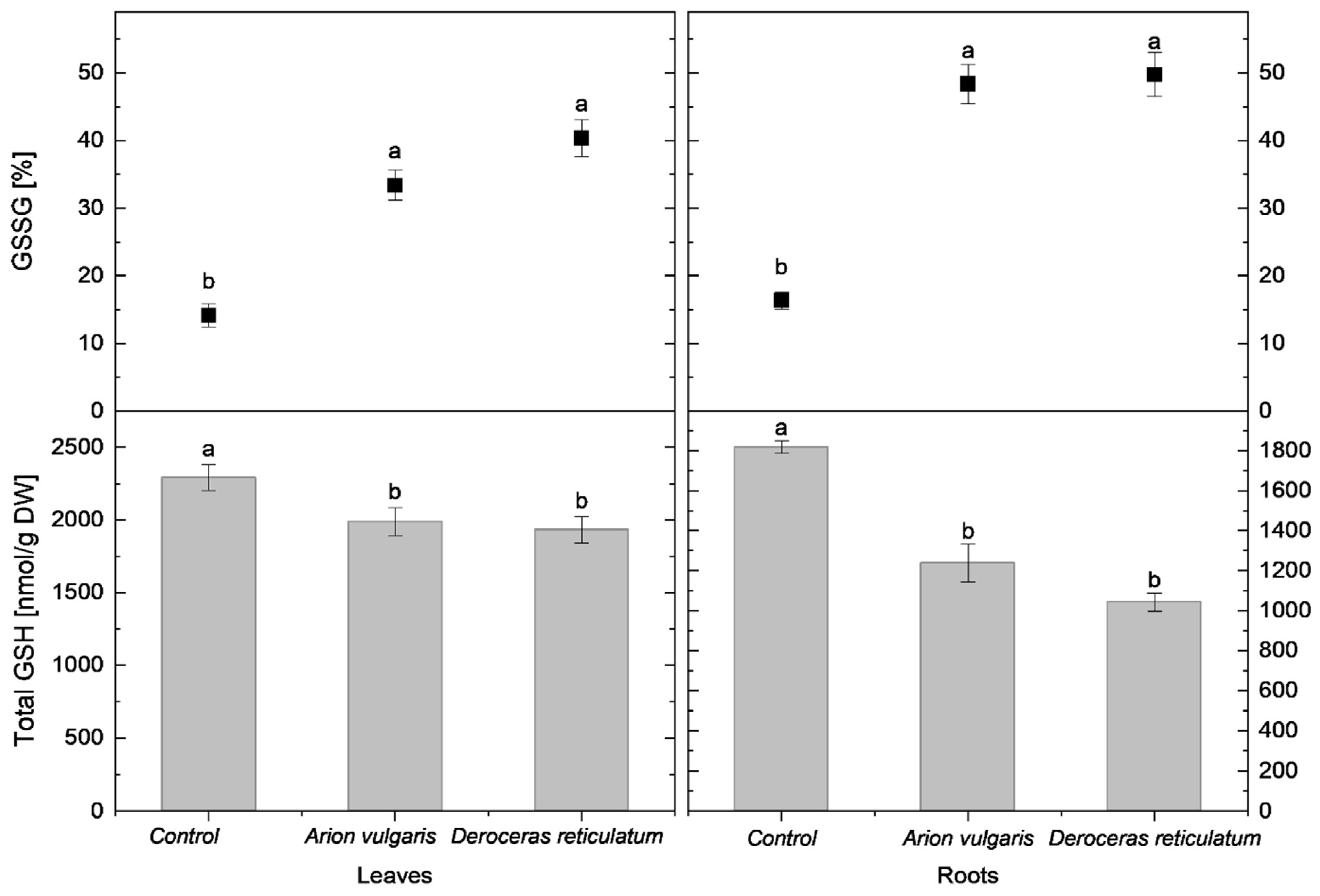

In cabbage leaves, cysteine concentration in control plants reached 735 nmol g−1 DW and was significantly higher than in slug-infested cabbage. Leaves of plants exposed to A. vulgaris contained 611 nmol g−1 DW of cysteine, while those exposed to D. reticulatum contained 578 nmol g−1 DW. A similar pattern was observed for tGSH. The highest tGSH content occurred in control leaves (2292 nmol g−1 DW), whereas significantly lower concentrations were measured in leaves damaged by A. vulgaris (1989 nmol g−1 DW) and D. reticulatum (1932 nmol g−1 DW).

In contrast to reduced thiols, the relative proportions of oxidized forms increased markedly following slug herbivory. The proportion of cystine in leaves was lowest in control plants (17%) and significantly higher in leaves exposed to A. vulgaris (41%) and D. reticulatum (47%). A similar trend was observed for oxidized glutathione (GSSG). It accounted for 14% in control plants and increased significantly to 33% in A. vulgaris-infested plants and 40% in D. reticulatum-infested plants.

Root tissues exhibited trends consistent with those observed in leaves. Control plants contained 500 nmol g−1 DW of cysteine, which was significantly higher than concentrations measured in roots exposed to A. vulgaris (413 nmol g−1 DW) and D. reticulatum (366 nmol g−1 DW). tGSH levels also differed significantly among all treatments, with the highest content in control roots (1819 nmol g−1 DW), followed by A. vulgaris (1237 nmol g−1 DW) and D. reticulatum (1041 nmol g−1 DW). The proportion of cystine increased significantly in slug-infested roots, reaching 50% in A. vulgaris-infested roots and 55% in D. reticulatum- infested roots, compared with 20% in controls. A parallel increase was observed for GSSG, rising to 48% in A. vulgaris-infested roots and 50% in D. reticulatum-infested roots, when compared to proportions of 16% in control roots.

Detailed data on cysteine concentrations are presented in Figure 3, while tGSH content and redox status are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Total cysteine content (nmol g−1 DW) and proportion of cystine (% of total cysteine) in the leaves and roots of control cabbage plants and plants infested by Arion vulgaris and Deroceras reticulatum. Bars represent mean values ± SE (n = 5). Different letters (a, b) indicate statistically significant differences among treatments (one-way ANOVA followed by Duncan’s multiple range test, p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Total glutathione content (tGSH; nmol g−1 DW) and proportion of oxidized glutathione (GSSG; % of tGSH) in the leaves and roots of control cabbage plants and plants infested by Arion vulgaris and Deroceras reticulatum. Bars represent mean values ± SE (n = 5). Different letters (a, b) indicate statistically significant differences among treatments (one-way ANOVA followed by Duncan’s multiple range test, p < 0.05).

3.3. Photosynthetic Pigments

Total chlorophyll content in cabbage leaves differed significantly among all experimental treatments. The highest total chlorophyll concentration was recorded in control plants (867.00 mg g−1 DW), followed by leaves of plants infested by A. vulgaris (665.65 mg g−1 DW) and D. reticulatum (552.93 mg g−1 DW). Similar trends were observed for both chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b. Control plants exhibited the highest levels of chlorophyll a (616.64 mg g−1 DW) and chlorophyll b (251.17 mg g−1 DW), whereas significantly lower concentrations were detected in plants exposed to A. vulgaris (chlorophyll a: 459.00 mg g−1 DW; chlorophyll b: 206.65 mg g−1 DW) and D. reticulatum (chlorophyll a: 375.48 mg g−1 DW; chlorophyll b: 177.46 mg g−1 DW). The chlorophyll a/b ratio was highest in control plants (2.47) and decreased significantly in slug-infested cabbage, reaching 2.22 in plants exposed to A. vulgaris and 2.12 in plants exposed to D. reticulatum.

Total carotenoid content also differed significantly among treatments. Control plants exhibited the highest carotenoid concentration (112.89 mg g−1 DW), followed by plants infested by A. vulgaris (90.46 mg g−1 DW) and D. reticulatum (82.14 mg g−1 DW).

Significant differences were detected for all quantified xanthophyll pigments. The concentrations of lutein, neoxanthin, and violaxanthin were highest in control plants (115.85, 38.60, and 47.69 mg g−1 DW, respectively), intermediate in leaves infested by A. vulgaris (lutein: 101.60 mg g−1 DW; neoxanthin: 23.82 mg g−1 DW; violaxanthin: 38.32 mg g−1 DW), and lowest in leaves infested by D. reticulatum (lutein: 94.23 mg g−1 DW; neoxanthin: 22.29 mg g−1 DW; violaxanthin: 34.77 mg g−1 DW). In contrast, the xanthophyll-cycle pigments antheraxanthin and zeaxanthin showed the opposite pattern, with significantly higher concentrations in slug-infested cabbage. The highest contents of both pigments were measured in leaves exposed to D. reticulatum (antheraxanthin: 11.93 mg g−1 DW; zeaxanthin: 9.96 mg g−1 DW; antheraxanthin and zeaxanthin, A + Z: 21.89 mg g−1 DW), followed by A. vulgaris (antheraxanthin: 11.09 mg g−1 DW; zeaxanthin: 9.76 mg g−1 DW; A + Z: 20.85 mg g−1 DW), while control plants contained the lowest levels (antheraxanthin: 9.03 mg g−1 DW; zeaxanthin: 9.36 mg g−1 DW; A + Z: 18.38 mg g−1 DW).

Detailed pigment profiles of cabbage leaves under control conditions and following slug herbivory are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Concentrations of photosynthetic pigments (mg g−1 DW) and relative percentage changes in the leaves of control Brassica oleracea plants and plants infested by Arion vulgaris and Deroceras reticulatum. Values followed by different letters indicate statistically significant differences among treatments (Duncan’s post hoc test, p < 0.05; n = 5).

3.4. Volatile Organic Compounds Emitted by Leaves and Roots of Slug-Infested Cabbage

SPME–GC–MS analysis revealed clear organ-specific changes in volatile organic compound (VOC) profiles of cabbage plants following slug herbivory (Table 2). Both aerial parts and roots emitted a diverse range of VOCs, including terpenoids, aldehydes, nitriles, and glucosinolate breakdown products, with distinct differences between control plants and plants infested by A. vulgaris or D. reticulatum.

Table 2.

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) detected by SPME–GC–MS in aerial parts (AP) and roots (R) of cabbage plants under control conditions and following herbivory by slugs. C = control plants; AV = plants infested with Arion vulgaris; DR = plants infested with Deroceras reticulatum. VOC occurrence is expressed semi-quantitatively based on relative peak areas: “−” indicates not detected; “+” indicates detected; “++” indicates a higher relative abundance (≥20% increase in peak area) compared to the other treatments within the same organ.

In aerial tissues, volatiles such as β-pinene, trans-β-ionone, 3,5-octadien-2-one, and 2-hexenal were detected across all treatments but generally occurred at lower relative levels in slug-infested plants. Among these, 2-hexenal was most abundant in control plants and consistently lower following feeding by both slug species. Root VOC profiles were dominated by sulphur-containing compounds and aromatic nitriles linked to glucosinolate metabolism. Allyl isothiocyanate, erucin, and 3-phenylpropionitrile were primarily detected in roots and showed pronounced treatment-dependent variation. Both allyl isothiocyanate and 3-phenylpropionitrile occurred at higher relative levels in control roots and declined following slug infestation, with species-specific differences between A. vulgaris and D. reticulatum.

Based on these patterns, three VOCs were selected for chemotaxis assays: 3-phenylpropionitrile, allyl isothiocyanate, and 2-hexenal. These compounds showed consistent, herbivory-induced modulation, represented distinct biochemical pathways and tissues, and clearly differentiated control from slug-infested cabbage plants, making them suitable candidates for assessing nematode chemotactic responses.

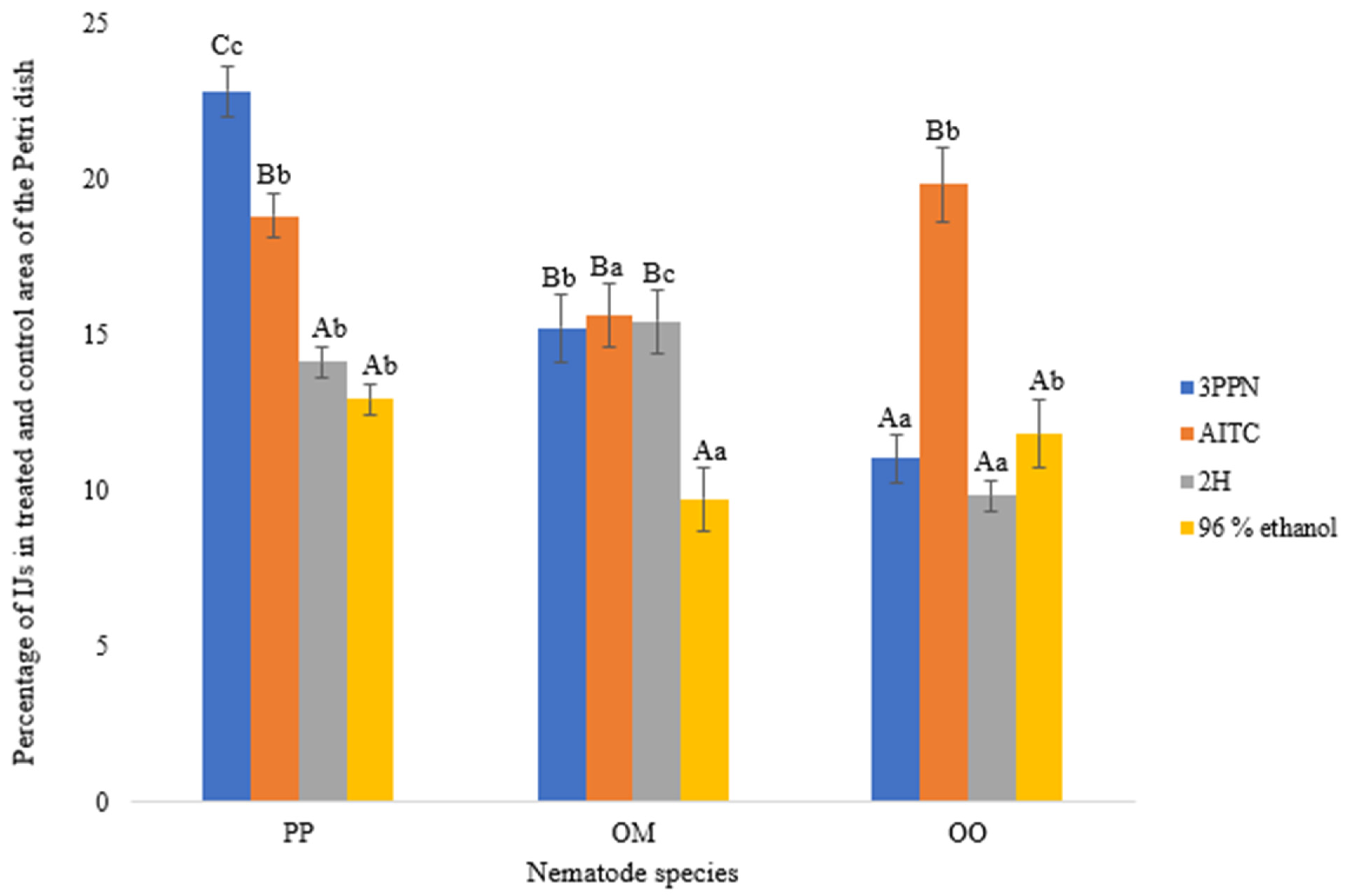

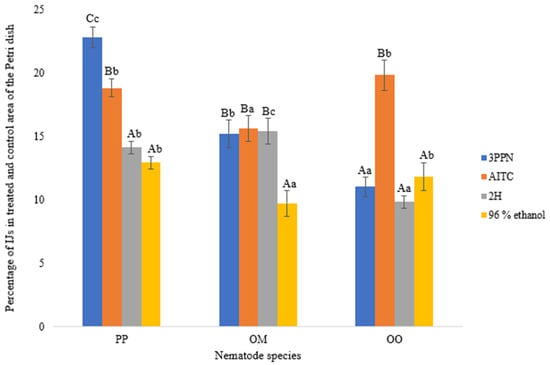

3.5. Nematode Motility

In this study, nematode motility was defined as the proportion of infective juveniles (IJs) migrating from the central area to the outer segments (treated and control areas; Figure 1). Analysis of variance showed that motility was significantly influenced by nematode species (F = 14.42, p = 0.0001) and VOC identity (F = 25.83, p = 0.0001) (Table 3). Temporal replication also contributed significantly (F = 8.66, p = 0.0001), whereas spatial replication had no effect (F = 1.43, p = 0.2399), indicating consistent within-plate conditions. A significant species × VOC interaction (F = 7.97, p = 0.0001) further demonstrated that motility responses depended on the specific nematode–compound combination.

Table 3.

ANOVA results for the directional movement of infective juveniles (IJs) from the inner to the outer segments of the Petri dish.

At 20 °C and a concentration of 0.03 ppm, nematode motility differed significantly among species and tested volatile organic compounds (Figure 5). Overall, P. papillosa (PP) exhibited the highest motility, followed by O. myriophilus (OM), while O. onirici (OO) consistently showed the lowest proportion of IJs migrating to the outer segments of the Petri dish.

Figure 5.

Percentage of infective juveniles (IJs) of different nematode species detected in the outer segments (treated and control areas) of the Petri dish after 24 h at 20 °C, following exposure to volatile organic compounds (VOCs) at a concentration of 0.03 ppm. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) among nematode species within the same VOC treatment, while capital letters indicate significant differences among VOC treatments within the same nematode species. The nematode species tested were PP = Phasmarhabditis papillosa, OM = Oscheius myriophilus, and OO = Oscheius onirici. The VOCs tested were 3PPN = 3-phenylpropionitrile, AITC = allyl isothiocyanate, and 2H = 2-hexenal; 96% ethanol served as the solvent control.

Among the tested compounds, 3-phenylpropionitrile (3PPN) induced the strongest motility response in P. papillosa, with more than 22% of IJs reaching the treated and control areas, significantly exceeding responses to the solvent control. Allyl isothiocyanate (AITC) also stimulated pronounced movement in P. papillosa, although to a lesser extent than 3PPN. In contrast, 2-hexenal (2H) elicited a moderate response, comparable to but still significantly higher than the ethanol control (Figure 5).

In O. myriophilus, motility responses were more balanced across VOC treatments. Both 3PPN and AITC induced similar levels of movement, whereas exposure to 2-hexenal resulted in slightly reduced motility. As observed for P. papillosa, all VOC treatments produced higher motility than the ethanol control, confirming a directed response to chemical cues.

Oscheius onirici displayed overall lower motility across all treatments. However, AITC triggered a significantly higher movement response compared to 3PPN, 2-hexenal, and the control, indicating compound-specific sensitivity in this species. The lowest motility values were consistently recorded under control conditions, demonstrating minimal random movement in the absence of VOC stimuli.

3.6. Chemotaxis Index

Chemotactic preference was evaluated using the chemotaxis index (CI) and analysed by ANOVA (Table 4). VOC identity showed a highly significant effect on CI (F = 254.87, p < 0.0001), indicating strong statistical evidence that nematode responses differed among compounds. Species also affected CI values (F = 8.67, p = 0.0002), and a significant species × VOC interaction was observed (F = 9.12, p < 0.0001), showing that the direction and magnitude of chemotaxis differed among nematode taxa depending on the compound tested. Temporal replication had a small but significant effect (F = 2.18, p = 0.0230), whereas spatial replication was not significant (F = 2.03, p = 0.1336).

Table 4.

Type III ANOVA for chemotaxis index (CI) values of infective juveniles (IJs) in response to volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Significant effects are shown for species, VOC identity, and their interaction; temporal and spatial replication were included as experimental factors.

The relatively low residual variance suggests that the statistical model captured a substantial proportion of the biologically relevant variation in nematode chemotaxis. Collectively, these results highlight the compound-specific and species-dependent nature of VOC-mediated nematode navigation, with VOC identity emerging as the primary driver of chemotactic behaviour under the experimental conditions tested.

The chemotaxis index (CI) values for three nematode species in response to 3-phenylpropionitrile (3PPN), allyl isothiocyanate (AITC), and 2-hexenal (2H) are summarized in Table 5. Overall, CI values indicated compound-specific and species-dependent chemotactic responses, with both attractive and repellent effects observed at the tested concentration (0.03 ppm).

Table 5.

Chemotaxis index (CI ± standard error) of three nematode species—P. papillosa (PP), O. myriophilus (OM), and O. onirici (OO)—in response to volatile organic compound (VOCs) tested at 0.03 ppm: 3-phenylpropionitrile (3PPN), allyl isothiocyanate (AITC), and 2-hexenal (2H). A 96% ethanol treatment served as the solvent control.

Phasmarhabditis papillosa exhibited the strongest attractant response to 3PPN (CI = 0.12 ± 0.01), classifying this compound as a weak attractant for this species. A similar but slightly lower positive response to 3PPN was observed in O. myriophilus (CI = 0.10 ± 0.01) and O. onirici (CI = 0.07 ± 0.01), indicating a consistent, albeit modest, attraction across all tested nematodes. In contrast, AITC elicited negative CI values in all species, with the strongest repellent effect observed in P. papillosa (CI = −0.16 ± 0.01), followed by O. myriophilus (CI = −0.10 ± 0.01) and O. onirici (CI = −0.08 ± 0.01), classifying AITC as a weak to moderate repellent.

Responses to 2-hexenal were generally weak and species-dependent. P. papillosa and O. myriophilus exhibited CI values close to zero (CI = 0.01 ± 0.01 and 0.03 ± 0.01, respectively), indicating no clear chemotactic effect, whereas O. onirici showed a slight repellent response (CI = −0.02 ± 0.01). The 96% ethanol control produced CI values ranging from −0.05 to −0.02, all within the “no effect” category, confirming that the solvent itself did not influence nematode movement.

4. Discussion

Plant–herbivore interactions are central drivers of ecological and evolutionary processes, and they frequently involve rapid reprogramming of plant metabolism after tissue injury [21]. Although research has historically emphasized insect herbivory, gastropods are also major crop pests, and their feeding, mucus deposition, and mechanical abrasion can elicit strong defence-related signalling [22]. Compared with insect herbivory, molluscan feeding represents a distinct mechanical and biochemical stress, involving extensive tissue abrasion, mucus secretion, and prolonged feeding bouts. These features may enhance oxidative pressure and alter the balance between glucosinolate hydrolysis products, potentially leading to systemic signalling patterns that differ from those typically described for insect-induced plant defences. Wounding and herbivory commonly induce reactive oxygen species (ROS), which act both as damaging agents and as signals that reconfigure antioxidant metabolism and downstream defences [8,9]. In this context, the ASC–GSH system represents a core redox hub that links ROS detoxification with redox-regulated defence pathways [8,9].

In our study, cabbage plants exposed to A. vulgaris and D. reticulatum showed a significant reduction in tASC in leaves, coupled with a strong increase in the DHA proportion, indicating a pronounced shift toward an oxidized ASC pool. Baseline leaf tASC values in control cabbage were within the range reported for Brassica tissues [23]. Ascorbate is increasingly recognized as a component of biotic-stress resistance through interactions with hormone and redox signalling networks, yet herbivory can cause either increases or decreases depending on the balance between synthesis, recycling, and oxidative consumption [24]. The response pattern—lower tASC and higher DHA—agrees with reports in other plant–herbivore systems where oxidative demand and/or limited recycling leads to net ascorbate depletion [25,26]. Mechanistically, severe oxidation can also drive irreversible losses through DHA breakdown and further degradation products [25]. Because the DHA/tASC ratio is widely used as an oxidative stress indicator, the elevated DHA fractions in slug-attacked plants strongly support the conclusion that slug feeding imposed substantial oxidative pressure [26].

Notably, we observed the same directional response in the roots, despite the absence of direct root feeding. This supports the view that antioxidant responses to aboveground herbivory can be systemic. ASC is enriched in phloem and can be transported from source leaves to sink organs, including roots [27]. The increased DHA proportion in roots, therefore, likely reflects systemic redox signalling and/or transport of oxidized/recycling-demanding pools rather than local mechanical injury. Similar systemic shifts in redox status have been linked to altered defence signalling and transcriptional control during stress responses [8].

Slug-infested cabbage also exhibited lower cysteine and tGSH in both leaves and roots, accompanied by markedly higher proportions of cystine and GSSG, consistent with strong oxidation of thiol pools. Baseline values in control plants were comparable to prior Brassica reports [28]. Because cysteine is a key precursor for GSH biosynthesis, parallel declines in cysteine and total GSH are expected when demand for redox buffering rises and/or when sulphur assimilation and thiol synthesis cannot match oxidative turnover [29]. The higher GSSG and cystine proportions in attacked plants represent a classic signature of oxidative stress and redox imbalance [29]. Similar shifts toward GSSG have been reported after herbivory in Arabidopsis and maize systems [30], supporting the interpretation that slug feeding triggers a defence state comparable—at least in redox terms—to chewing or sap-feeding insect attack.

The reduction in tGSH in roots again points to a systemic component of the response. GSH pools can be redistributed among organs and are tightly integrated with long-distance stress signalling [8]. Alternatively (or additionally), systemic stress can promote GSH consumption and degradation even in tissues not directly damaged [17]. Importantly, thiol metabolism is also functionally connected to Brassicaceae secondary metabolism: GSH is required for key steps in glucosinolate-related pathways, and GSH-deficient genotypes accumulate lower glucosinolate levels [31]. Therefore, the GSH depletion may have consequences not only for redox buffering but also for the plant’s capacity to sustain glucosinolate-based chemical defences.

Slug herbivory significantly reduced chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and total chlorophyll content, and decreased the chlorophyll a/b ratio, indicating impaired photosynthetic pigment status and likely stress on the photosynthetic apparatus. Declines in chlorophyll content are commonly reported under herbivore pressure and are frequently associated with oxidative damage and stress-induced chlorophyll catabolism [32]. Oxidative stress is also a recognized driver of chlorophyll degradation pathways [33]. The reduced chlorophyll a/b ratio further supports increased stress pressure, as altered antenna composition and pigment stoichiometry can reflect physiological adjustment under unfavourable conditions [34].

Carotenoids and xanthophylls also responded in a manner consistent with elevated oxidative and photoprotective demand. Total carotenoids declined in attacked plants, which may reflect consumption/oxidation and/or metabolic reallocation under stress [35]. Within the xanthophyll cycle, lower violaxanthin together with higher antheraxanthin and zeaxanthin is consistent with activation of photoprotective energy dissipation and an increased need to protect thylakoid membranes under stress [35]. This pattern matches broader interpretations that antheraxanthin/zeaxanthin accumulation increases when plants experience enhanced excitation pressure and ROS risk [14]. Taken together, pigments and the antioxidant redox pool converge on the same conclusion: slug herbivory imposed strong oxidative stress and triggered systemic defence-related metabolic adjustments.

SPME–GC–MS data demonstrated tissue-specific VOC shifts in both aerial parts and roots after slug herbivory. In Brassicaceae, this is expected because damage activates myrosinase-mediated hydrolysis of glucosinolates, producing isothiocyanates and nitriles that function in defence and signalling [15]. Our VOC table indicated that allyl isothiocyanate (AITC) and 3-phenylpropionitrile (3PPN) (root-associated glucosinolate breakdown products) and 2-hexenal (a typical green leaf volatile linked to LOX activity) were among the compounds showing clear, herbivory-associated differences. Root VOC changes following aboveground attack are also consistent with systemic defence signalling, which can modify root chemistry and exudate/volatile profiles even when roots are not directly damaged [6,7,16].

Behavioural assays showed that VOCs strongly influenced motility (movement from the central area toward outer segments), with significant effects of VOC identity and nematode species as well as a significant VOC × species interaction. This supports the concept that chemical cues stimulate host-search behaviour but that responses differ among taxa due to divergent sensory ecology [6,7]. Importantly, motility and chemotaxis index (CI) do not necessarily track together: increased movement can reflect general arousal/activation, whereas CI captures directional preference [16,20]. This distinction is useful for interpreting our results: while several VOCs increased the proportion of IJs reaching outer zones, CI values revealed that only some cues produced consistent attraction or repellency.

3PPN is a weak attractant, AITC is a weak repellent, and 2-hexenal is largely neutral for SPNs. At the tested concentration, 3PPN produced weak attraction across species (strongest in P. papillosa), whereas AITC acted as a weak repellent in all three nematodes, and 2-hexenal showed little to no directional effect (near-zero CI). These outcomes align well with prior evidence that Brassicaceae volatiles can serve as navigation signals for beneficial nematodes, but that their effects are compound- and species-specific [15,16]. Nitriles such as benzonitrile have previously been reported as attractive cues in some nematode–Brassica contexts [15], and our finding that 3PPN trends attractant is therefore consistent with nitriles acting as informative host/habitat signals. In contrast, the repellency of AITC is also biologically plausible: isothiocyanates are well known for broad bioactivity and are central to Brassica biofumigation effects against plant-parasitic nematodes [36,37]. Thus, AITC may represent a “defensive toxin cue” that discourages nematode movement toward high-exposure zones, even for beneficial or facultatively associated nematodes.

The largely neutral response to 2-hexenal suggests that, under our assay conditions, this green-leaf volatile is not a strong directional cue for these slug-parasitic nematodes. Green-leaf volatiles are often associated with mechanical damage and herbivory, and they can mediate trophic interactions in aboveground systems [38]. However, belowground nematode navigation may rely more strongly on sulphur-rich compounds, nitriles, CO2, and host-derived cues than on typical leaf aldehydes—especially for slug-associated nematodes in moist soil microhabitats [39]. This interpretation is also consistent with the idea that nematodes integrate multiple sensory channels and that single-compound signals can be weak unless presented in ecologically realistic blends [6,7].

Together, our data indicate that aboveground slug feeding triggers a systemic oxidative stress response and modifies both aerial and root volatile profiles in cabbage. The behavioural assays further show that slug-parasitic nematodes respond in a compound- and species-dependent manner: 3PPN has potential as an attractant cue, AITC is repellent, and 2-hexenal is largely non-informative at the tested dose. These findings support the broader concept of belowground multitrophic communication, where plant-derived volatiles can influence natural enemies and potentially be leveraged in pest management [6,15,16].

A limitation of the present study is that nematode chemotaxis was assessed under controlled laboratory conditions, which cannot fully replicate the physical and chemical complexity of field soils. VOC diffusion, persistence, and microbial transformation in natural soils may therefore modify the strength and spatial range of chemical cues perceived by nematodes. To strengthen ecological interpretation and application, future studies should (i) quantify actual feeding damage and/or mucus deposition to relate damage intensity to redox and VOC shifts [22], (ii) include time-series sampling because antioxidant and pigment responses are highly dynamic [17], (iii) measure enzymatic components of the ASC–GSH cycle (e.g., APX, DHAR, GR, GST) to mechanistically anchor redox shifts [8], and (iv) test VOC blends and soil-context delivery, since persistence and diffusion of VOCs depend strongly on soil physicochemical conditions and microbial degradation [9]. Finally, because Brassica breakdown products can be both attractive signals and toxicants, optimising concentrations and delivery modes will be essential to selectively enhance SPN recruitment without impairing their survival or performance.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that aboveground feeding by the slugs A. vulgaris and D. reticulatum induces a pronounced oxidative stress response in cabbage plants that extends systemically to the roots. Slug herbivory reduced total ascorbic acid (tASC) and glutathione (tGSH) pools while increasing the proportions of their oxidized forms (DHA, cystine, and GSSG) in both leaves and roots, indicating a shift toward a more oxidized redox state. In parallel, slug feeding reduced chlorophyll and carotenoid contents and altered xanthophyll-cycle composition, with decreased violaxanthin accompanied by increased antheraxanthin and zeaxanthin, consistent with enhanced photoprotective demand and stress-related pigment remodelling.

Slug herbivory also modified cabbage volatile profiles in an organ-specific manner, including changes in glucosinolate-derived compounds and green-leaf volatiles. Based on these VOC shifts, three representative compounds were selected for behavioural assays. Chemotaxis experiments conducted at 0.03 ppm and 20 °C showed compound- and species-dependent nematode responses: 3-phenylpropionitrile acted as a weak attractant (most pronounced in P. papillosa), allyl isothiocyanate consistently functioned as a weak repellent, and 2-hexenal was largely neutral. These findings highlight that nematode activation and directional preference are distinct behavioural endpoints and that Brassicaceae-derived VOCs may serve either as navigational cues or avoidance signals depending on compound identity.

Overall, our results link slug-induced systemic redox reconfiguration with altered plant volatile emissions and demonstrate that selected cabbage VOCs can modulate the behaviour of slug-parasitic nematodes. This supports the concept of belowground multitrophic signalling and identifies 3-phenylpropionitrile as a promising candidate for further evaluation as a semiochemical to enhance nematode recruitment, while underscoring the importance of optimising dose and delivery for bioactive compounds such as allyl isothiocyanate. Future studies should relate feeding intensity to biochemical and VOC dynamics, incorporate time-series sampling and antioxidant enzyme measurements, and test ecologically realistic VOC blends and soil-based delivery systems to assess persistence, diffusion, and net effects on nematode survival and biocontrol performance.

Author Contributions

Ž.L. and S.T. designed the project and conducted the chemotactic experiment; Ž.L. conducted the chemotactic assay; M.K. performed VOC analyses; J.S. and A.U.K. performed pigment and antioxidant analyses; Ž.L., S.T., M.K., J.S. and A.U.K. analysed the data and wrote the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was conducted within project J4-50135 and research programmes P4-0431, P1-0005, and P1-0164 funded by the Slovenian Research Agency. Part of this research was funded within Professional Tasks from the Field of Plant Protection, a program funded by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Food of the Phytosanitary Administration of the Republic of Slovenia.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks are given to Jaka Rupnik and Karolina Kralj for their technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rowson, B.; Turner, J.; Anderson, R.; Symondson, B. Slugs of Britain and Ireland; FSC Publications: Telford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Castle, G.D.; Mills, G.A.; Gravell, A.; Jones, L.; Townsend, I.; Cameron, D.G.; Fones, G.R. Review of the Molluscicide Metaldehyde in the Environment. Environ. Sci. Water Res. 2017, 3, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rae, R.; Sheehy, L.; McDonald-Howard, K. Thirty Years of Slug Control Using the Parasitic Nematode Phasmarhabditis hermaphrodita and Beyond. Pest Manag. Sci. 2023, 79, 3408–3424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takabayashi, J.; Dicke, M. Plant-carnivore mutualism through herbivore-induced carnivore attractants. Trends Plant Sci. 1996, 1, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turlings, T.C.J.; Erb, M. Tritrophic Interactions Mediated by Herbivore-Induced Plant Volatiles: Mechanisms, Ecological Relevance, and Application Potential. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2018, 63, 433–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmann, S.; Köllner, T.G.; Degenhardt, J.; Hiltpold, I.; Toepfer, S.; Kuhlmann, U.; Gershenzon, J.; Turlings, T.C.J. Recruitment of entomopathogenic nematodes by insect-damaged maize roots. Nature 2005, 434, 732–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, J.G.; Alborn, H.T.; Stelinski, L.L. Subterranean herbivore-induced volatiles released by citrus roots upon feeding by Diaprepes abbreviatus recruit entomopathogenic nematodes. J. Chem. Ecol. 2010, 36, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foyer, C.H.; Noctor, G. Ascorbate and Glutathione: The Heart of the Redox Hub. Plant Physiol. 2011, 155, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noctor, G.; Mhamdi, A.; Chaouch, S.; Han, Y.; Neukermans, J.; Marquez-García, B.; Queval, G.; Foyer, C.H. Glutathione in Plants: An Integrated Overview. Plant Cell Environ. 2012, 35, 454–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massacci, A.; Nabiev, S.M.; Pietrosanti, L.; Nematov, S.K.; Chernikova, T.N.; Thor, K.; Leipner, J. Response of the photosynthetic apparatus of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) to the onset of drought stress under field conditions studied by gas-exchange analysis and chlorophyll flourescence imaging. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2008, 46, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, R.J.; van Dam, N.M.; van Loon, J.J.A. Role of Glucosinolates in Insect–Plant Relationships and Multitrophic Interactions. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2009, 54, 57–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, K.L.; Kaestner, J.; Bodenhausen, N.; Schramm, K.; Paetz, C.; Vassão, D.G.; Reichelt, M.; von Knorre, D.; Bergelson, J.; Erb, M.; et al. The Role of Glucosinolates and the Jasmonic Acid Pathway in Resistance of Arabidopsis thaliana against Molluscan Herbivores. Mol. Ecol. 2014, 23, 1188–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloem, E.; Haneklaus, S.; Schnug, E. Milestones in plant sulfur research on sulfur-induced-resistance (SIR) in Europe. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 5, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laznik, Ž.; Križman, M.; Zekič, J.; Roškarič, M.; Trdan, S.; Urbanek Krajnc, A. The Role of Ascorbate–Glutathione System and Volatiles Emitted by Insect-Damaged Lettuce Roots as Navigation Signals for Insect and Slug Parasitic Nematodes. Insects 2023, 14, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laznik, Ž.; Tóth, T.; Ádám, S.; Trdan, S.; Majić, I.; Lakatos, T. Responses of Parasitic Nematodes to Volatile Organic Compounds Emitted by Brassica nigra Roots. Agronomy 2025, 15, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagodič, A.; Ipavec, N.; Trdan, S.; Laznik, Ž. Attraction Behaviors: Are Synthetic Volatiles, Typically Emitted by Insect-Damaged Brassica nigra Roots, Navigation Signals for Entomopathogenic Nematodes (Steinernema and Heterorhabditis)? BioControl 2017, 62, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tausz, M.; Wonisch, A.; Grill, D.; Morales, D.; Jimenez, M.S. Measuring antioxidants in tree species in the natural environment: From sampling to data evaluation. J. Exp. Bot. 2003, 54, 1505–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranner, I.; Grill, D. Content of Low-Molecular-Weight Thiols during the Imbibition of Pea Seeds. Physiol. Plant. 1993, 88, 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K.; Buschmann, C. Chlorophylls and Carotenoids: Measurement and Characterization by UV–VIS Spectroscopy. Curr. Protoc. Food Anal. Chem. 2001, 1, F4.3.1–F4.3.8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargmann, C.I.; Horvitz, H.R. Chemosensory Neurons with Overlapping Functions Direct Chemotaxis to Multiple Chemicals in C. elegans. Neuron 1991, 7, 729–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, B.; Zhang, G. Interactions between plants and herbivores: A review of plant defense. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2014, 34, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orrock, J.L. Exposure of unwounded plants to chemical cues associated with herbivores leads to exposure-dependent changes in subsequent herbivore attack. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e79900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhandari, S.R.; Kwak, J.H. Chemical composition and antioxidant activity in different tissues of Brassica vegetables. Molecules 2015, 20, 1228–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Gupta, R.; Shokat, S.; Iqbal, N.; Kocsy, G.; Pérez-Pérez, J.M.; Riyazuddin, R. Ascorbate, plant hormones and their interactions during plant responses to biotic stress. Physiol. Plant. 2024, 176, e14388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, J.L.; Felton, G.W. Foliar oxidative stress and insect herbivory: Primary compounds, secondary metabolites, and reactive oxygen species as components of induced resistance. J. Chem. Ecol. 1995, 21, 1511–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerchev, P.I.; Fenton, B.; Foyer, C.H.; Hancock, R.D. Infestation of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) by the peach-potato aphid (Myzus persicae Sulzer) alters cellular redox status and is influenced by ascorbate. Plant Cell Environ. 2012, 35, 430–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschi, V.R.; Tarlyn, N.M. L-Ascorbic acid is accumulated in source leaf phloem and transported to sink tissues in plants. Plant Physiol. 2002, 130, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Cui, J.; Luo, C.; Gao, L.; Chen, Y.; Shen, Z. Contribution of cell walls, nonprotein thiols, and organic acids to cadmium resistance in two cabbage varieties. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2013, 64, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zechmann, B. Subcellular roles of glutathione in mediating plant defense during biotic stress. Plants 2020, 9, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łukasik, I.; Wołoch, A.; Sytykiewicz, H.; Sprawka, I.; Goławska, S. Changes in the content of thiol compounds and the activity of glutathione S-transferase in maize seedlings in response to a rose-grass aphid infestation. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0221160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, B.; Wang, K.; Liang, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Yang, J. Transcriptome analysis of glutathione response: RNA-Seq provides insights into balance between antioxidant response and glucosinolate metabolism. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zahrani, W.; Bafeel, S.O.; El-Zohri, M. Jasmonates mediate plant defense responses to Spodoptera exigua herbivory in tomato and maize foliage. Plant Signal. Behav. 2020, 15, 1746898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, A.; Ito, H. Chlorophyll degradation and its physiological function. Plant Cell Physiol. 2025, 66, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonobe, R.; Yamashita, H.; Mihara, H.; Morita, A.; Ikka, T. Estimation of leaf chlorophyll a, b and carotenoid contents and their ratios using hyperspectral reflectance. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havaux, M. Carotenoid oxidation products as stress signals in plants. Plant J. 2014, 79, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anastasiadis, I.A.; Karanastasi, E. Factors affecting the efficacy of Brassica species and ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) on root-knot nematode infestation of tomato. Commun. Agric. Appl. Biol. Sci. 2011, 76, 333–340. [Google Scholar]

- Roubtsova, T.V.; Yakovleva, E.; Bostock, R.M.; Subbotin, S.A.; Kravchenko, A.N.; Borneman, J.; Becker, J.O. Effect of Broccoli (Brassica oleracea) Tissue, Incorporated at Different Depths in a Soil Column, on Meloidogyne incognita. J. Nematol. 2007, 39, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mostafa, S.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, W.; Jin, B. Plant responses to herbivory, wounding, and infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallem, E.A.; Dillman, A.R.; Hong, A.V.; Zhang, Y.; Yano, J.M.; DeMarco, S.F.; Sternberg, P.W. A Sensory Code for Host Seeking in Parasitic Nematodes. Curr. Biol. 2011, 21, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.