Abstract

Establishing shrub plantations on mobile sand dunes is an effective strategy to combat desertification in semi-arid regions. Herbaceous communities developing beneath these plantations enhance ecosystem stability and improve revegetation outcomes. This study investigated the structural responses of soil bacterial communities, key functional genes (nifH, amoA, and phoD), and plant–soil–microbe interactions across a herbaceous vegetation succession gradient (initiation, early, middle, and stable stages) under Caragana microphylla sand-fixation plantations in the sandy Horqin Grassland. The results revealed that plant species richness, diversity, and biomass increased progressively with succession. Concurrent improvements in soil nutrients (organic matter, nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium) and enzymatic activities (urease, protease, phosphatase, glucosidase, polyphenol oxidase, and dehydrogenase) were observed. The abundances of nifH, amoA, and phoD genes rose progressively with vegetation succession, contributing to enhanced soil nutrient levels. All dominant bacterial phyla and genera detected constituted shared taxa across successional stages, but their relative abundances shifted dynamically. Herbaceous succession facilitated rapid restoration of bacterial diversity, though structural recovery lagged, depending on the quantitative fluctuations of the dominant taxa. Soil pH, organic matter, electrical conductivity, total N, total P, available P, and available K all significantly influenced the soil bacterial community, with pH and organic matter being the most influential factors. These findings highlight plant–soil–microbe interactions as intrinsic drivers of vegetation succession in desertified ecosystems.

1. Introduction

Desertification, a global environmental challenge, primarily occurs in arid, semi-arid, and dry sub-humid regions as a consequence of unsustainable human socioeconomic activities and global climate change. It leads to ecological degradation, resource depletion, and local impoverishment, garnering worldwide attention [1]. The Horqin Sandy Land (also known as Horqin Grassland), spanning approximately 51,750 km2, is situated in the ecologically fragile semi-arid zone of Northeast China and serves as a significant traditional animal husbandry base. However, severe desertification has emerged since the 1970s due to overgrazing, excessive land reclamation, and unsustainable fuelwood harvesting under an arid and windy climate. Today, it ranks among China’s most severely desertified regions. Revegetation on desertified grasslands is a critical initial step for ecosystem restoration and has proven to be an effective desertification control strategy [2]. Consequently, extensive areas of tree, shrub, or semi-shrub sand-fixation vegetation have been established artificially on mobile and semi-mobile sand dunes in the Horqin Sandy Land over recent decades. These plantations play vital roles in sand stabilization, vegetation recovery, preventing windblown sand damage, and improving the local environment [3]. The ecological functions of these sand-fixation plantations vary depending on their type, age, and structure. Following establishment, greater focus should be directed towards their long-term stability and the sustainability of their protective functions.

Generally, moving sand dunes can be stabilized through plantation establishment within 3–5 years, leading to improved microenvironments. Subsequently, pioneer herbaceous species (short grasses and forbs) typically begin to colonize the area. The formation and succession of these herbaceous communities further enhance sand surface stabilization and promote water and soil conservation. Moreover, the rapid growth and turnover of herbaceous plants provide significant inputs of carbon (C), nitrogen (N), and other nutrients [3], contributing to soil property amelioration and soil microbial community recovery. However, degeneration of shrub or semi-shrub sand-fixation plantations (e.g., Caragana microphylla Lam., Artemisia halodendron Turcz., and Salix gordejevii Y. L. Chang et Skv.) often occurs 8–10 years after establishment. This decline is attributed to the biological and ecological limitations of the plant species under the inherently poor nutrient and arid sandy soil conditions, manifesting as growth stagnation, branch withering, and even whole-plant mortality. In such cases, if well-developed herbaceous communities have not established beneath the plantations, the previously fixed sand dunes risk becoming reactivated. Therefore, the herbaceous community plays a critical role in maintaining the long-term stability of sand-fixation plantations and restoring desertified ecosystems. Understanding the succession patterns of herbaceous communities under these plantations and their driving factors is essential for gaining deeper insights into ecological restoration processes and evaluating the effectiveness of vegetation restoration in degraded sandy land ecosystems.

Plant community succession is driven by internal forces arising from reciprocal interactions among plant populations, between plants, soil, and microbes (PSM), and among plants, animals, and microbes [4,5,6]. Among these, PSM interactions play a pivotal role at small scales. They influence soil physical, chemical, and microbiological properties, modulate nutrient and water availability, directly impact plant growth and development, regulate relationships among community components, and thereby drive continuous alterations in plant community structure and function, ultimately propelling succession [7,8]. Numerous PSM studies have focused on mechanisms underlying exotic species invasion, biodiversity maintenance, vegetation dynamics, and vegetation responses to global change [9,10,11,12]. Research demonstrates that both biotic (e.g., intra- and interspecific competition) and abiotic (e.g., resource availability) factors can significantly influence PSM interactions [6,13,14,15]. Mounting evidence underscores the fundamental role of PSM interactions in plant community assembly processes [16]. Therefore, a deeper understanding of the dynamics and underlying mechanisms of PSM interactions is essential to unravel the succession mechanisms of specific plant communities.

Soil microorganisms are considered an important driving factor for the succession of plant communities because they directly or indirectly participate in all ecological processes of soil nutrient cycles (especially C, N, P, and K) [17,18]. The composition and structure of soil microbial communities sensitively respond to environmental variations, and their dynamics are inevitably related to soil properties and vegetation succession. Han et al. (2025) reported that during alpine grassland restoration, both bacterial and fungal communities exhibit sensitivity to changes in plant biomass and diversity, with soil nutrient availability and microenvironmental conditions playing a significant role in structuring microbial composition [19]. Regarding sand dune vegetation succession, some studies have also shown that the composition, structure, and diversity of soil bacterial and fungal communities respond in coordination with vegetation development and are significantly influenced by soil physicochemical properties and enzymatic activity [4,20,21]. Studies suggest that the response of soil microbial community to plant–soil interaction can be expressed at functional gene, species, and community levels [22,23]. Earlier studies on the succession of vegetation generally focused on the relationship between plant and soil and confirmed that plant community development alters soil nutrient pool size, which in turn shapes the plant community, while the role of soil microbial community in the interaction and feedback between plant and soil is often overlooked or underestimated. However, many recent studies in microbial ecology have been conducted to demonstrate the functions of microbial communities in plant–soil systems [22,23,24].

This study investigated a chronosequence of herbaceous community succession beneath C. microphylla sand-fixation plantations within the Horqin Sandy Land desertification control demonstration area. We assessed plant species composition, soil properties, and soil bacterial community structure across different herbaceous community succession stages. The study aimed to (1) determine structural responses of the soil bacterial community to herbaceous succession, specifically tracking changes in the abundance of ammonia-oxidizing, N-fixing, and P-transforming bacteria; (2) explore interactions between soil properties and the bacterial community during succession; and (3) identify key factors shaping the bacterial community. We hypothesize that the abundance of soil bacterial communities, particularly those involved in N and P transformation, gradually increases along the successional stages; soil nutrients significantly influence the structural shifts in bacterial communities; and vegetation succession markedly affects the relative abundance of dominant bacterial taxonomic groups.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Location and Site Description

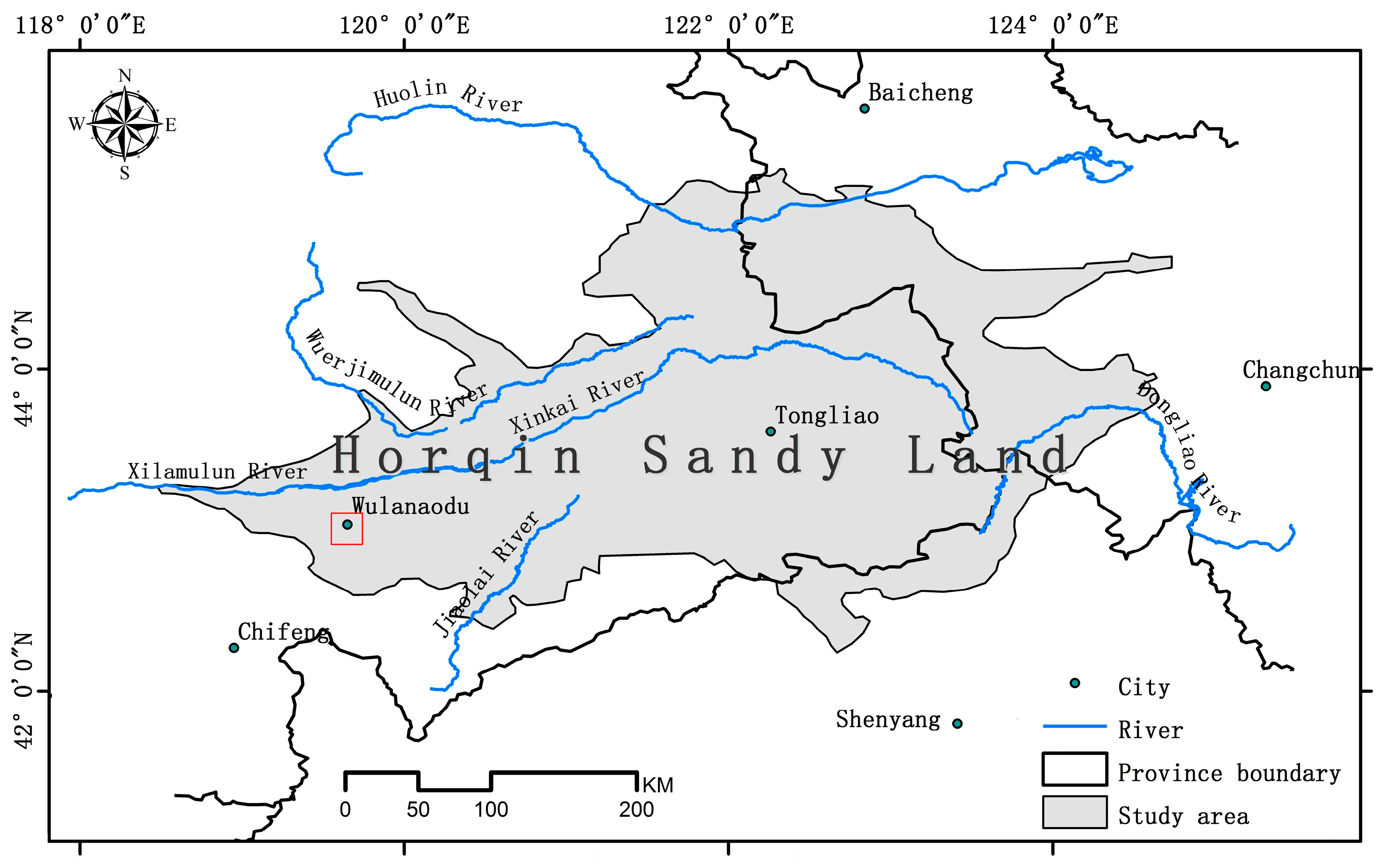

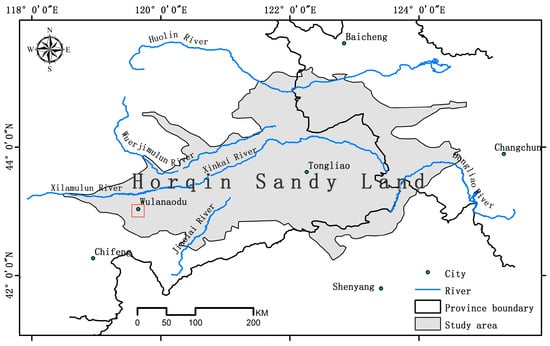

This study was conducted within the Horqin Sandy Land Desertification Control Demonstration Area, established by the Wulanaodu Desertification Combating Ecological Station, the Institute of Applied Ecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, beginning in 1981. The demonstration area is situated in the Wulanaodu region (43°03′ N, 119°38′ E) in the western Horqin Sandy Land, covering over 20 km2 (Figure 1). Historically, the landscape consisted of continuous mobile and semi-mobile sand dunes interspersed with interdune bottomlands. The region experiences a temperate continental semi-arid monsoon climate. Meteorological data from the Wulanaodu Weather Station indicate a mean annual temperature of 6.3 °C, a frost-free period of 130 days, and average annual precipitation of 340.5 mm (70–80% occurring May–September). Annual pan evaporation averages approximately 2500 mm. Prevailing winds average 4.5 m·s−1 with frequent spring/winter gales (>20 m·s−1). Soils are classified as Arenosols [25]. Original vegetation comprised Ulmus pumila-dominant open woodlands of the Mongolian flora, largely degraded during desertification. Current sandy land vegetation includes Caragana microphylla Lam., Salix microstachya Turcz., Artemisia halodendron Turcz., Agriophyllum squarrosum (L.) Moq., Bassia dasyphylla O. Kuntze, Cynachum sibiricum L., Lappula echinata Gilib., Artemisia scoparia Waldstein et Kitaibel, Geranium dahuricum DC., Cleistogens chinensis (Maxim.) Keng, and Setaria viridis (L.) Beauv. Native shrubs and semi-shrubs (e.g., C. microphylla, A. halodendron, and Hedysarum fruticosum Pall.) serve as pioneer species for dune stabilization. Since the 1980s, extensive sand-fixation plantations have been established using 1 m × 1 m straw checkerboard barriers followed by seeding/seedling planting. The entire demonstration area has been fenced with barbed wire post-revegetation.

Figure 1.

Study location (geographical location map was provided by Dr. Renhui Miao).

2.2. Experimental Design and Soil Sampling

A chronosequence of herbaceous community succession stages beneath sand-fixation plantations in the Wulanaodu demonstration area was selected for study. The stages comprised (1) the initiate stage (IS), an unvegetated mobile sand dune; (2) the early stage (ES), dominated by annual grasses; (3) the middle stage (MS), dominated by rhizomatous grasses; and (4) the stable stage (SS), dominated by bunchgrasses. Plant community surveys and soil sampling corresponding to these four stages were conducted in the following locations: unvegetated mobile sand dunes (IS), 10-year-old C. microphylla plantations (ES), 40-year-old C. microphylla plantations (MS), and natural U. pumila open forest (SS). The total vegetation coverage of IS, ES, MS, and SS was <5%, 50%, 70%, and 75%, respectively. ES and MS were all formed from revegetation via planting C. microphylla on similar moving sand dunes at different times, with the initial row spacing of 1 m × 1 m; SS originated from the spontaneous recovery after the enclosure of the desertified natural C. microphylla community in the demonstration area. Vegetation surveys and soil sample collection were conducted in August 2023, during early autumn and the most vigorous period of plant growth. Six spatially independent sitesper succession stages were established on different sand dunes as replicates. Within each site, one transect was established. Ten 1 m × 1 m quadrats spaced at 10 m intervals along the transects were used to record plant species composition, coverage, density, and above-ground biomass [26]. A total of 60 quadrats were surveyed per stage. Twenty soil subsamples (0−10 cm depth) were randomly collected within the plot using a shovel and composited into one bulk sample per site. Field-sieving through a 2 mm mesh was performed immediately after collection. Samples were placed in sterilized plastic ziplock bags. This yielded a total of 24 composite soil samples (4 stages × 6 sites). Each composite sample was split: one half was air-dried for physicochemical analysis; the other half was stored at −80 °C for DNA extraction and soil enzyme activity assays.

2.3. Soil Physicochemical Property and Enzymatic Activity Analysis

Soil moisture, pH, electrical conductivity (EC), organic matter (SOM), total N, P, and K, and available N (NH4+-N), P, and K were analyzed in the laboratory. Soil moisture was determined gravimetrically by oven-drying at 105 °C for 12 h. pH and EC were measured in soil–water suspensions (1:2.5 w/v for pH, 1:5 w/v for EC). SOM was quantified using the K2Cr2O7–H2SO4 oxidation method. Total N was determined by the semi-micro Kjeldahl method. Total P was measured using the acid digestion molybdate colorimetric method. Available P was extracted with 0.5 M NaHCO3 and measured using the molybdate ascorbic acid method. Total K and available K were determined by atomic absorption spectroscopy. Ammonium nitrogen (NH4+-N) was extracted from fresh soil with 1 M KCl solution and quantified using an automated discrete analyzer (CleverChem 380, Hamburg, Germany). All physicochemical analyses followed the procedures described by Lin (2004) [27].

The activities of four hydrolases (urease, alkaline phosphomonoesterase, protease, and β-glucosidase) and two oxidoreductases (polyphenol oxidase and dehydrogenase) related to soil carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus transformation were determined. Urease activity was determined according to Kandeler & Gerber (1988) [28]. Alkaline phosphomonoesterase activity was measured following Tabatabai (1982) [29]. Protease activity was assessed using the original method of Ladd & Butler (1972) [30]. Polyphenol oxidase activity was determined as described by Perucci et al. (2000) [31]. β-glucosidase activity was measured following Xu & Zheng (1986) [32]. Dehydrogenase activity was quantified according to ISSCAS (1985) [33]. Detailed procedures for all enzyme activity assays are provided in the Supplementary Materials and Methods (File S1).

2.4. Microbial 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing and Analysis of the Composition and Diversity of the Bacterial Community

Next-generation sequencing library preparation and Illumina MiSeq sequencing were performed by GENEWIZ, Inc. (Suzhou, China). The V3–V4 hypervariable regions of bacterial 16S rRNA genes were amplified. Bioinformatic processing used the QIIME pipeline (v1.9.1). Quality-filtered sequences were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at 97% similarity threshold using VSEARCH (v1.9.6). Representative sequences were taxonomically classified against the SILVA database using the RDP classifier. Bacterial taxonomy followed Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. Alpha diversity metrics (Chao1 richness, observed OTUs, Shannon diversity index, and Pielou’s evenness) were calculated in Mothur (v1.21.1). Beta diversity analysis employed hierarchical clustering (UPGMA) based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity. Raw sequence data are publicly accessible in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under BioProject PRJNA841013.

2.5. The Abundance of Soil Ammonia-Oxidizing, Nitrogen-Fixing, and Organic Phosphorus-Mineralizing Bacteria

Soil microbial DNA was extracted from IS, ES, MS, and SS sites using the FastDNA Spin Kit (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China). Functional gene abundances (nifH, amoA, and phoD) were quantified via real-time qPCR (Q5 System, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) to estimate the abundance of ammonia-oxidizing, nitrogen-fixing, and organic phosphorus-mineralizing bacteria, with the following primers: nifH: F1 (5′-TGCGAYCCSAARGCGAC-3′), R1 (5′-ATSGCCATCATYTCRCCGGA-3′) [34]; amoA: F2 (5′-GGGGTTTCTACTGGTGGT-3′), R2 (5′-CCCCTCKGSAAAGCCTTCTTC-3′) [35]; phoD: F3 (5′-TGGGAYGATCAYGARGT-3′), and R3 (5′-CTGSGCSAKSACRTTCCA-3′) [36]. Detailed protocols for sequencing, qPCR, and bioinformatics are provided in Supplementary Materials and Methods (File S1).

2.6. Data Analysis

Plant species abundance was quantified as density (number of individuals per m2 across all quadrats), frequency (percentage occurrence across quadrats), and average coverage. For each species, an importance value (IV) and relative dominance value (RDV) were calculated [37], where IV = RA + RC + RF (RA: relative abundance, RC: relative coverage, RF: relative frequency) and RDV = IV/∑IV. Soil properties, alpha diversity indices of bacterial communities, and the abundances of nifH, amoA, and phoD genes across different successional stages were examined using one-way ANOVA. Post hoc comparisons were performed with the least significant difference (LSD) test in SPSS (version 18.0), with statistical significance defined at p < 0.05. Differentiated bacterial taxa at each succession stage were identified via LEfSe (Linear Discriminant Analysis Effect Size) analysis, applying a significance threshold of 0.05 and an LDA effect size cutoff of 4. Relationships between soil bacterial community structure and environmental factors were assessed using redundancy analysis (RDA; CANOCO v5.0).

3. Results

3.1. Dynamics of Plant Species Composition Along Plant Community Succession

Following the fixation of mobile sand dunes by C. microphylla planting, annual plants gradually invaded, establishing an herbaceous community beneath the plantation. Both the coverage and biomass of this herbaceous community increased with plantation development. Average coverage reached 26.1% in the early stage (ES), 39.6% in the middle stage (MS), and 75.5% in the stable stage (SS). Similarly, average dry biomass increased from 49.2 g·m−2 (ES) to 186.1 g·m−2 (MS) and 548.4 g·m−2 (SS). Species richness showed an increasing trend across succession stages, rising from 20 species in ES to 36 species in SS (Table S1). Distinct dominant species characterized each stage. ES was dominated by Setaria viridis (L.) Beauv. (45.9% relative importance value), Chenopodium acuminatum Willd. (16.1%), and Eragrostis pilosa (L.) P.B. (13.1%); however, their dominance declined sharply in MS and SS. In MS, perennial rhizomatous grasses invaded and became dominant, primarily Pennisetum flaccidum Griseb. (44.0%), Corispermum thelegium Kitag. (18.2%), and Salsola collina Pall. (11.2%). SS (climax stage) was dominated by the perennial short-rhizome grass Agropyron cristatum (L.) Gaertner (36.0%), followed by P. flaccidum (13.5%) and S. viridis (19.0%).

3.2. Soil Properties

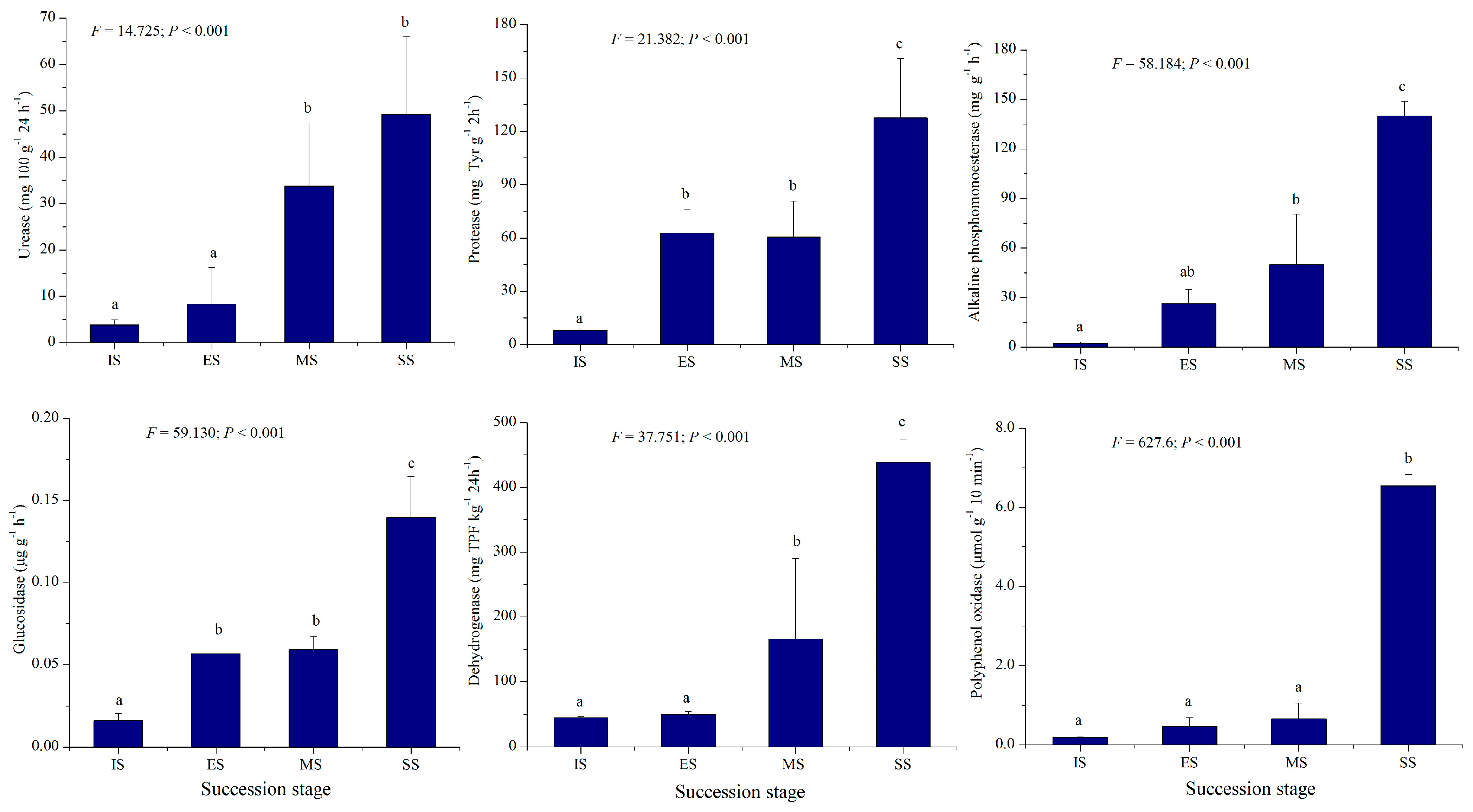

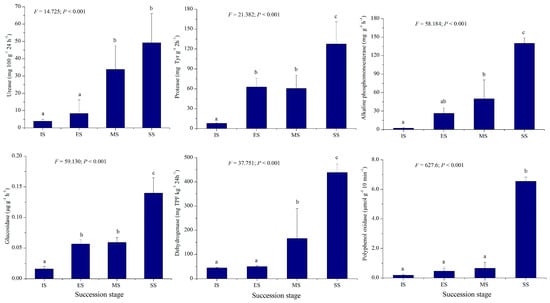

Table 1 presents soil moisture, pH, electrical conductivity, organic matter, total N, P, and K, NH4+-N, and available P and K values for IS, ES, MS, and SS. Significant differences (p < 0.001) were observed in all measured soil factors, except total K, across succession stages. Most soil indicators, especially total and available nutrients in vegetation-covered sites (ES, MS, SS), were higher than in IS and exhibited increasing trends along the successional gradient. The soil organic matter, total N, total P, NH4+-N, available P, and available K of SS were 1.73–34.20, 3.21–11.25, 2.00–9.33, 1.25–1.860, 1.27–5.02, and 0.98–3.08 times higher than those of other successional stages (Table 1). This indicates that herbaceous vegetation development under plantations contributed significantly to soil nutrient enrichment. Activities of six soil enzymes, i.e., urease, protease, alkaline phosphomonoesterase, glucosidase, polyphenol oxidase, and dehydrogenase, are shown in Figure 2. These enzymatic activities also differed significantly among succession stages (p < 0.001). The activities of the six soil enzymes of SS were 1.46–12.90, 2.11–15.94, 2.81–62.90, 2.36–9.73, 9.92–33.76, and 2.64–9.69 times higher than those of other successional stages, mirroring soil nutrient trends. Values were lowest at IS and peaked at SS. The above results indicate that vegetation development is closely correlated with soil nutrients and biological activity, demonstrating interaction and feedback mechanisms between them. Enhanced soil biological activity favors increased nutrient availability, thereby promoting plant growth and the invasion of new species. The increased complexity of plant communities and higher biomass, in turn, facilitates the accumulation of soil nutrients.

Table 1.

Dynamic changes in soil physicochemical properties across different successional stages.

Figure 2.

Soil enzymatic activities of different succession stages. IS: initiate stage, ES: early stage, MS: middle stage, SS: stable stage. Different letters indicate significant differences (LSD test, p < 0.05).

3.3. Composition of Soil Bacterial Communities Across Succession Stages

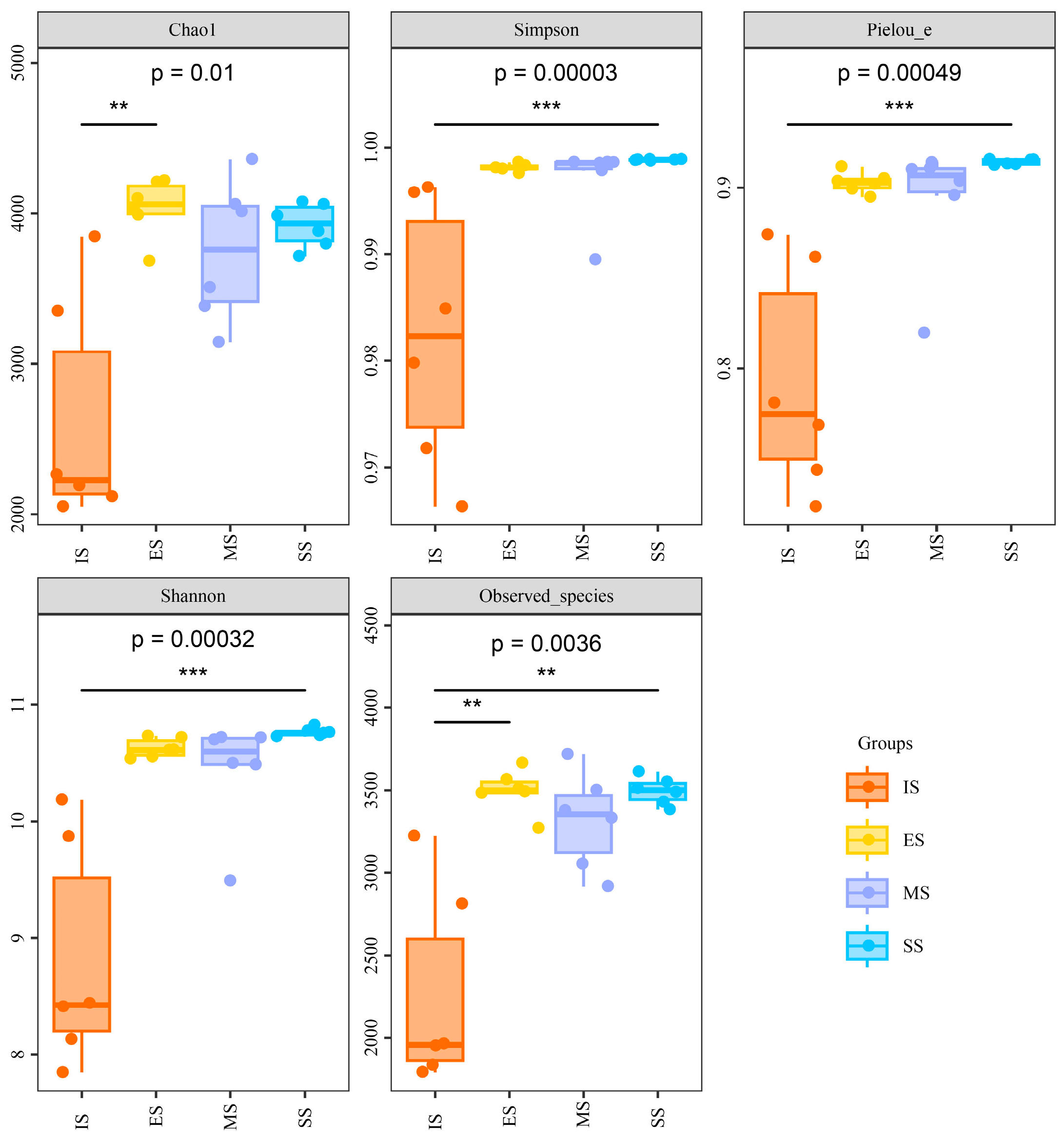

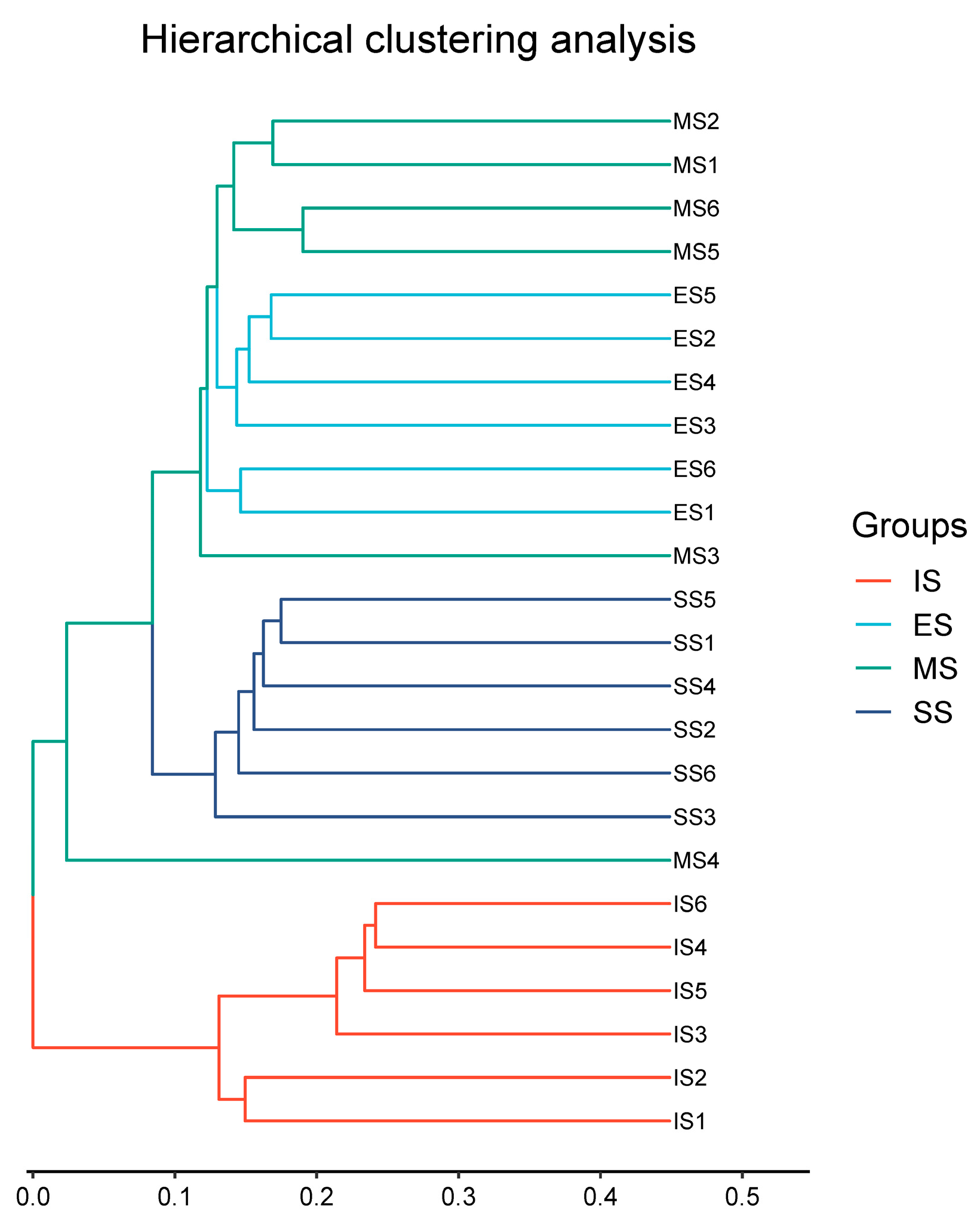

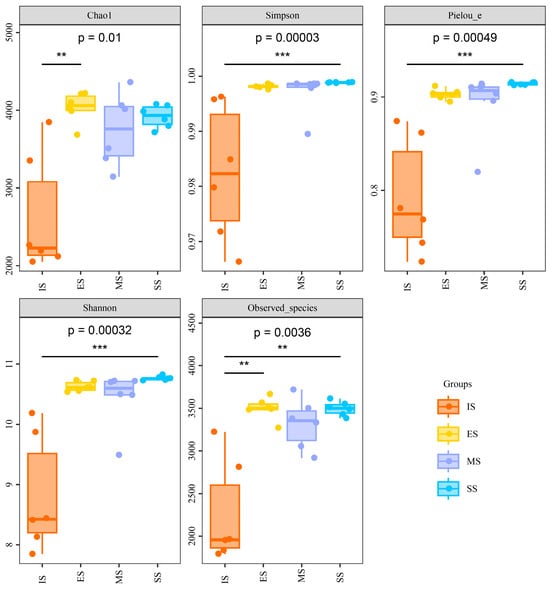

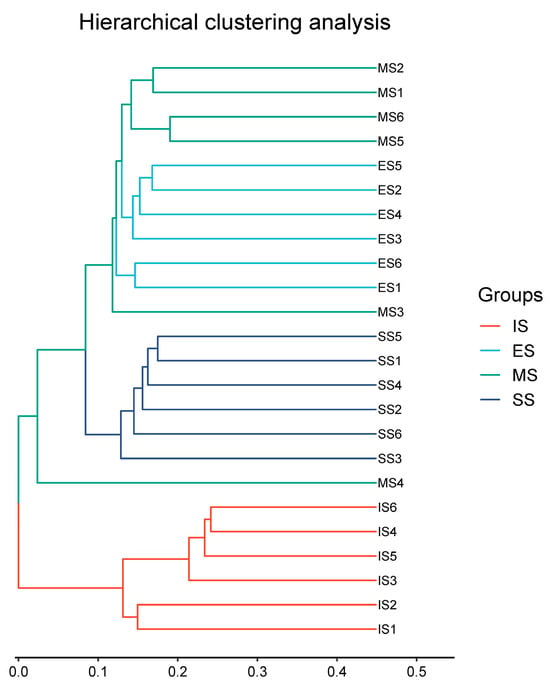

Soil genomic DNA was sequenced using an Illumina MiSeq high-throughput sequencing platform, yielding 1,153,233 high-quality 16S rRNA gene sequences. All rarefaction curves approached saturation at the sequencing depth (Figure S1), indicating sufficient sampling coverage to characterize bacterial community composition. Significant differences (p < 0.001) in α-diversity indices (Shannon–Wiener, Simpson, Chao1 richness, Pielou evenness, and observed species) were observed between IS and vegetation-covered sites (ES, MS, SS), though no significant differences emerged among ES, MS, and SS (Figure 3). All diversity indices showed significant correlations (p < 0.05) with soil pH, organic matter, NH4+-N, electrical conductivity (except Simpson and Pielou), soil moisture (except Simpson), and total/available P (except Simpson) (Table S2). No significant correlations were found with total N, total K, or available K. Hierarchical clustering analysis based on OTUs grouped the 24 samples into four distinct clusters (Figure 4). Samples predominantly clustered by successional stage, indicating significant divergence in soil bacterial community structure along the successional gradient.

Figure 3.

Alpha diversity indexes of soil bacterial communities of different succession stages. One-way ANOVA and multiple comparisons followed by LSD test are presented; **: p ≤ 0.01; ***: p ≤ 0.001. IS: initiate stage, ES: early stage, MS: middle stage, SS: stable stage.

Figure 4.

Hierarchical clustering analysis of different samples based on the structure of the soil bacteria community. IS: initiate stage, ES: early stage, MS: middle stage, SS: stable stage.

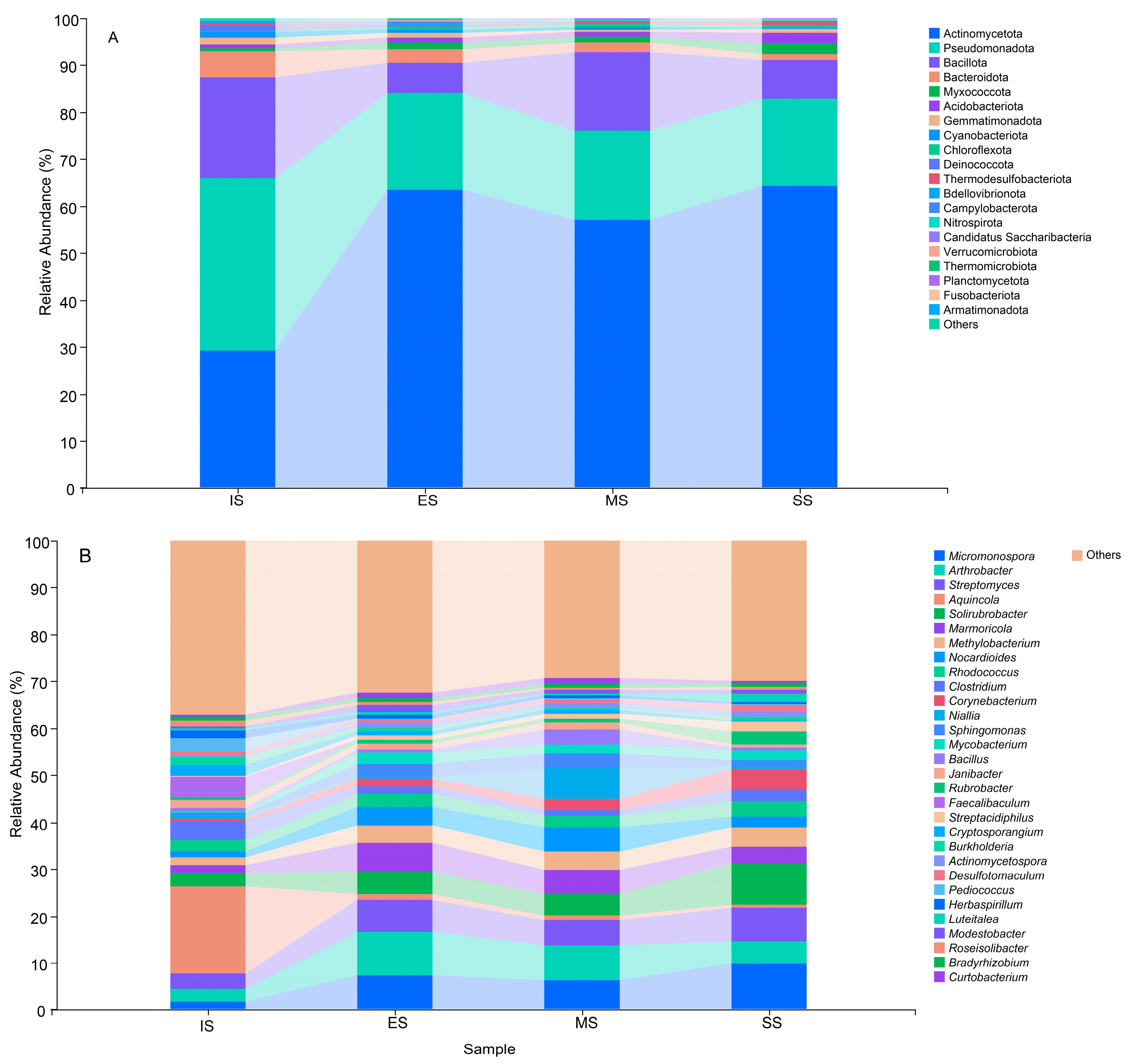

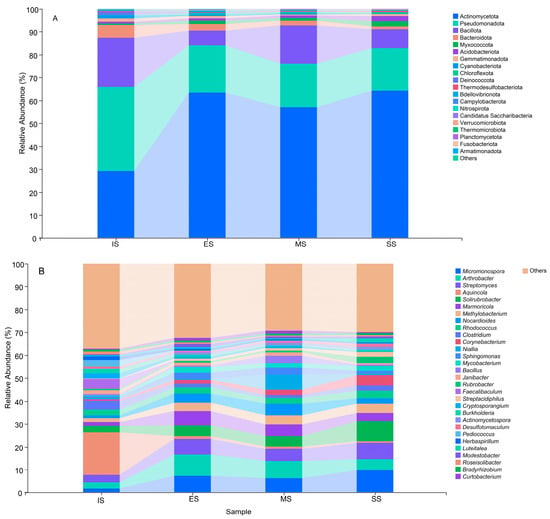

Actinomycetota, Pseudomonadota, Bacillota, Bacteroidota, Myxococcota, Acidobacteriota, Gemmatimonadota, and Cyanobacteriota constituted the dominant phyla (Figure 5A), with average relative abundances ranging from 29.28% to 64.20%, 18.70% to 36.63%, 6.56% to 21.41%, 1.32% to 5.55%, 0.73% to 2.30%, 0.82% to 2.15%, 0.58% to 1.38%, and 0.16% to 1.22%, respectively. Significant differences (p < 0.05) in the relative abundance of dominant phyla were observed across succession stages, except for Bacillota. Actinomycetota, Acidobacteriota, and Myxococcota generally increased along the successional gradient, while Pseudomonadota and Bacteroidota decreased. Figure 5B showed the relative abundances of the 30 most dominant genera. These genera comprised a shared core community across sites. However, significant differences (p < 0.05) in their relative abundances occurred between IS and vegetated succession stages (ES, MS, SS), except for Rhodococcus, Niallia, Bacillus, and Bradyrhizobium.

Figure 5.

Relative abundances of dominant bacterial phyla (A) and genera (B) of different succession stages. IS: initiate stage, ES: early stage, MS: middle stage, SS: stable stage.

Significant abundance differences were also detected among ES, MS, and SS for 20 bacterial genera. This phenomenon indicates that soil bacterial communities rapidly respond to herbaceous plant invasion into mobile sand dunes, with bacterial succession tightly coupled to herbaceous vegetation development. In IS, Aquincola (18.69%), Faecalibaculum (4.38%), Clostridium (3.89%), Pediococcus (3.03%), Solirubrobacter (2.93%), and Cryptosporangium (2.30%) were most abundant, but their relative abundances decreased significantly in vegetation-covered sites (ES, MS, SS). Conversely, multiple genera became dominant in vegetated sites, including Micromonospora (6.19–9.79%), Arthrobacter (4.80–9.44%), Streptomyces (5.28–7.15%), Solirubrobacter (4.49–8.83%), Marmoricola (3.62–6.15%), Methylobacterium (3.76–4.02%), Nocardioides (2.19–5.11%), Corynebacterium (1.74–4.54%), Sphingomonas (1.30–3.25%), Mycobacterium (1.74–2.38%), Streptacidiphilus (1.02–2.11%), and Actinomycetospora (1.04–1.24%). Shifts in the abundance of these genera altered soil bacterial community structure and likely contributed to herbaceous vegetation succession.

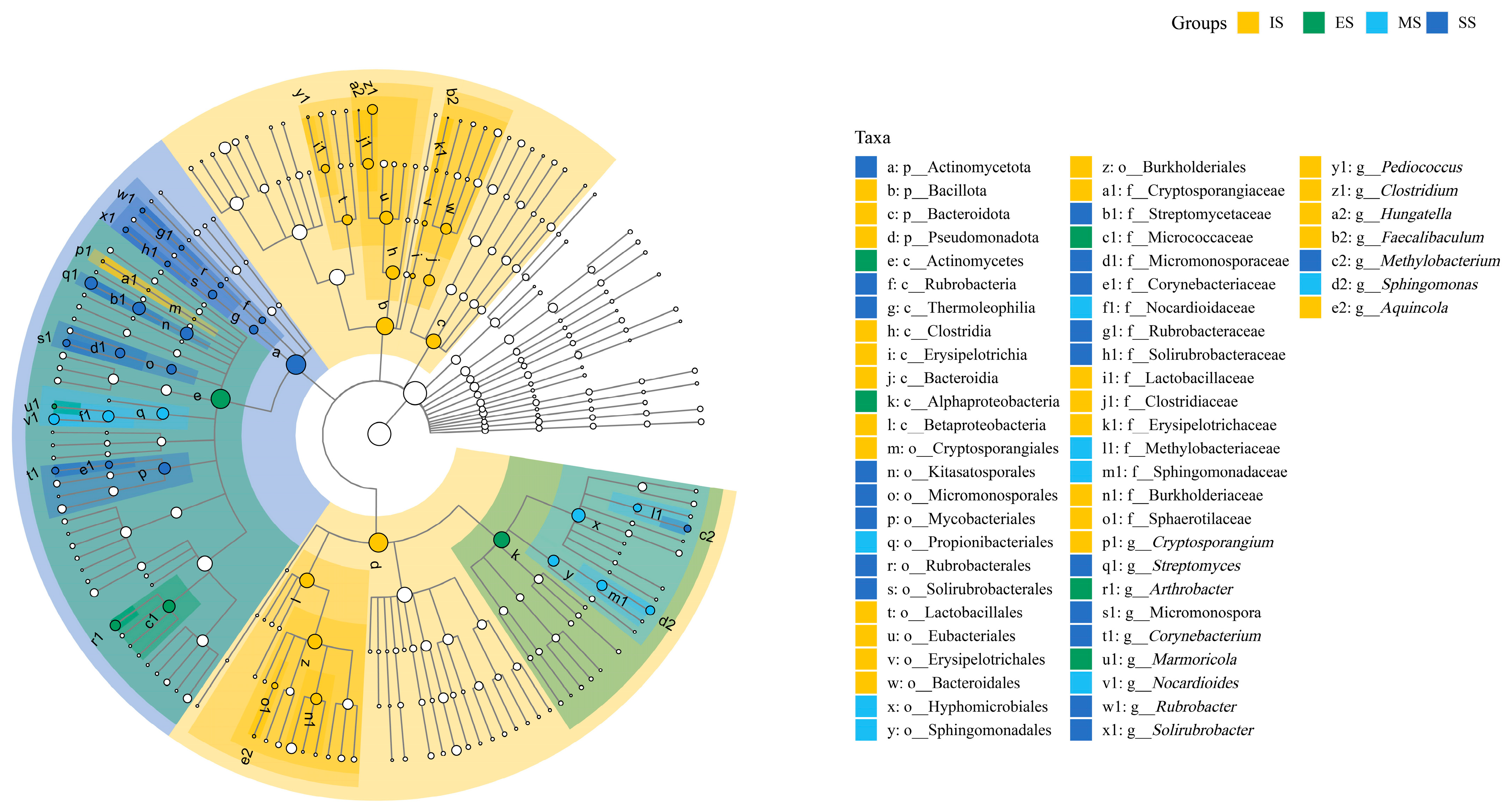

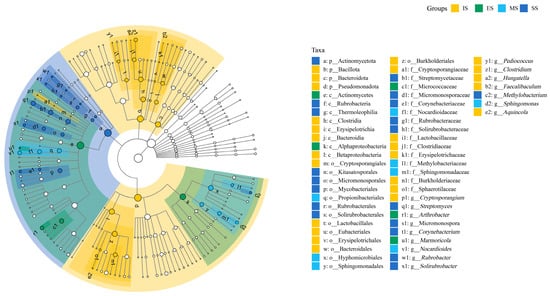

LEfSe analysis identified stage-specific bacterial taxa contributing significantly to structural variation in soil bacterial communities across herbaceous vegetation succession stages. Key biomarkers identified were (1) IS, including Cryptosporangiales (Cryptosporangiaceae and Cryptosporangium), Bacillota (Lactobacillales (Lactobacillaceae, and Pediococcus), Clostridia (Eubacteriales, Clostridiaceae, Clostridium, and Hungatella), Erysipelotrichales (Erysipelotrichaceae and Faecalibaculum), Bacteroidota (Bacteroidia, Bacteroidales), Pseudomonadota (Betaproteobacteria, Burkholderiales, Burkholderiaceae, Sphaerotilaceae, and Aquincola). (2) ES included Alphaproteobacteria, Actinomycetes, Micrococcaceae, Arthrobacter, and Marmoricola. (3) MS included Propionibacteriales (Nocardioidaceae and Nocardioides), Hyphomicrobiales (Methylobacteriaceae), and Sphingomonadales (Sphingomonadaceae and Sphingomonas). (4) SS included Actinomycetota, Kitasatosporales (Streptomycetaceae and Streptomyces), Micromonosporales (Micromonosporaceae and Micromonospora), Mycobacteriales (Corynebacteriaceae and Corynebacterium), Rubrobacteria (Rubrobacterales, Rubrobacteraceae, and Rubrobacter), Thermoleophilia (Solirubrobacterales, Solirubrobacteraceae, and Solirubrobacter), and Methylobacterium. The LEfSe results confirmed significant divergence in soil bacterial community structure across succession stages (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Significantly different taxa detected by LEfSe in different bacterial communities. A significance level of 0.05 was used for all of the biomarkers evaluated. Only taxa meeting an LDA significance threshold of >4 in soil abacterial communities are shown. IS: initiate stage, ES: early stage, MS: middle stage, SS: stable stage.

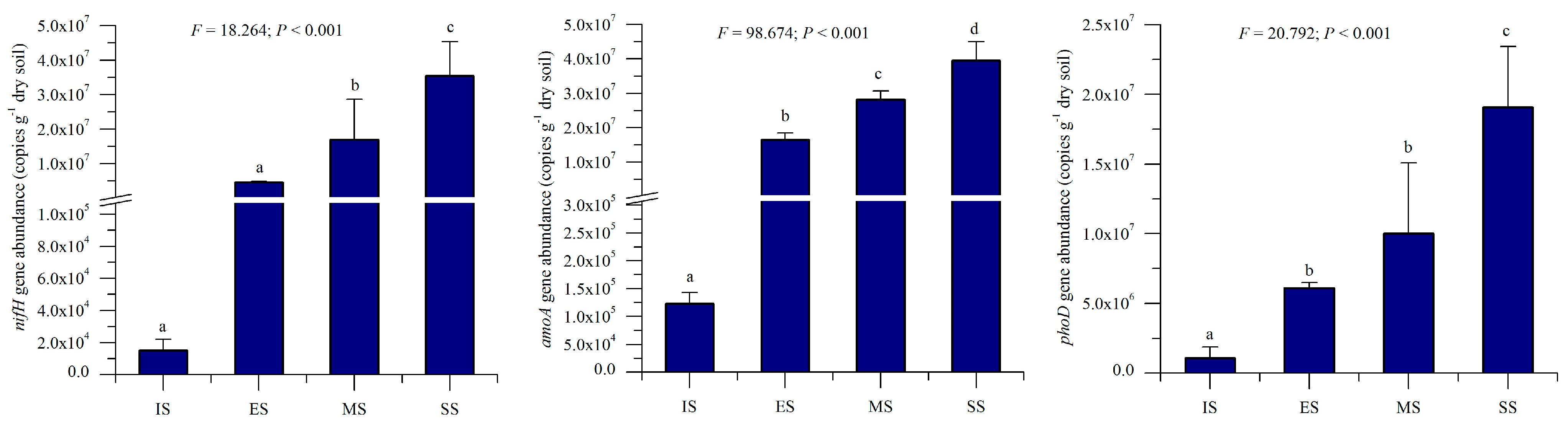

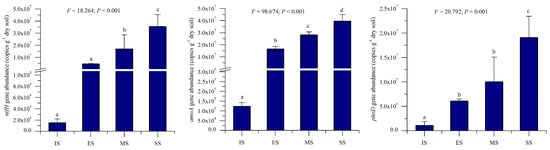

3.4. Response of nifH-, amoA-, and phoD-Harboring Microbe Abundance to Succession

Quantitative PCR determined abundances of nifH, amoA, and phoD genes across succession stages. All three genes exhibited increasing abundance trends along the successional gradient (Figure 7): nifH: 1.51 × 104 (IS) to 3.54 × 104 (SS) copies g−1 dry soil; amoA: 1.23 × 105 (IS) to 3.95 × 107 (SS) copies g−1 dry soil; and phoD: 1.08 × 106 (IS) to 1.91 × 107 (SS) copies g−1 dry soil. Abundances differed significantly among stages (p < 0.001), with herbaceous vegetation recovery driving substantial increases: nifH: 301.5× (ES), 1123.8× (MS), and 2337.9× (SS) higher than IS; amoA: 133.8× (ES), 229.4× (MS), and 321.6× (SS) higher; phoD: 5.6× (ES), 9.3× (MS), and 17.7× (SS) higher. These gene abundance trends mirrored those of soil properties and enzymatic activities. Correlation analysis revealed significant positive relationships (p < 0.05) between gene abundances and key soil parameters (pH, electrical conductivity, organic matter, total N, total P, available P, and available K (Pearson r = 0.459–0.953).

Figure 7.

Abundances of soil nifH, amoA, and phoD genes of different succession stages. IS: initiate stage, ES: early stage, MS: middle stage, SS: stable stage. Different letters indicate significant differences (LSD test, p < 0.05).

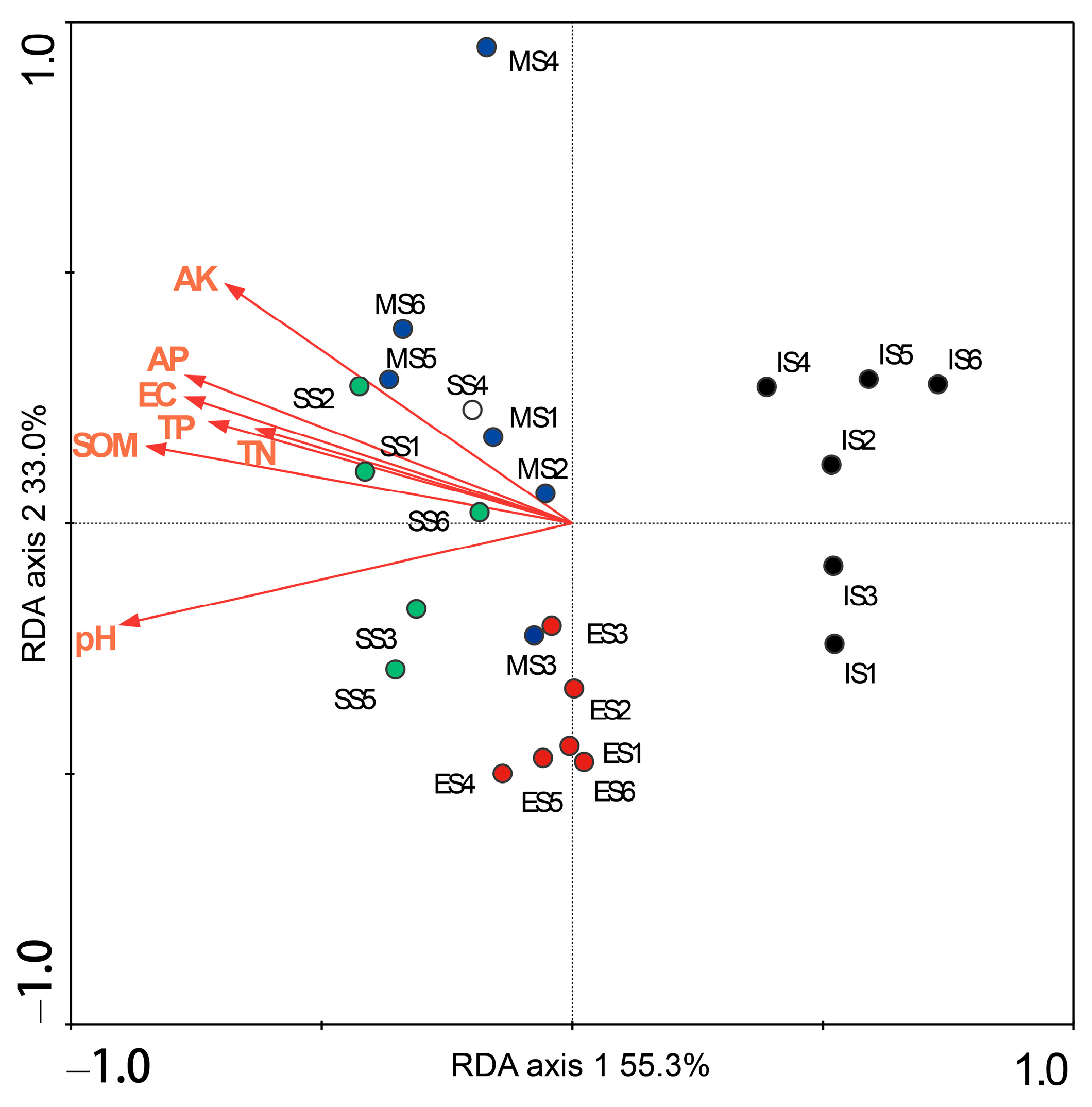

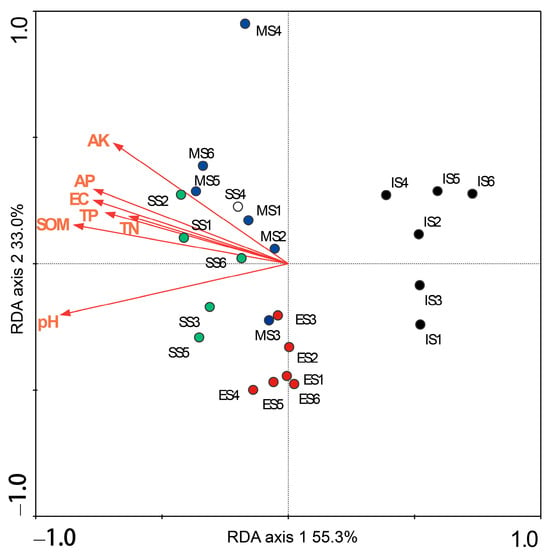

3.5. Relationship Between Bacterial Community Structure and Soil Properties

Redundancy analysis (RDA) was performed to identify soil properties significantly influencing the bacterial community structure. The analyzed properties included soil moisture, pH, electrical conductivity, organic matter, total N, total P, available N, available P, and available K. The first two RDA axes collectively explained 88.3% of the variation in bacterial community structure, with the first axis accounting for 55.3% and the second axis accounting for 33.0% (Figure 8). Monte Carlo permutation tests indicated that soil pH, organic matter, electrical conductivity, total N, total P, available P, and available K all exerted significant effects on the bacterial community (p < 0.05). These significant variables individually explained 25%, 22%, 19%, 15%, 18%, 19%, and 18% of the variance, respectively. In the RDA ordination plot (Figure 8), samples from different succession sites were distinctly separated, primarily occupying different regions of the ordination space. Furthermore, samples from the same site tended to cluster together. This spatial distribution pattern, consistent with the results of hierarchical clustering analysis (Figure 4), clearly demonstrates the distinct shifts in soil bacterial community structure along the vegetation succession gradient.

Figure 8.

Redundancy analysis between the structure of bacterial communities and soil properties. SOM: organic matter, EC: electrical conductivity, TN: total nitrogen, TP: total phosphorus, AP: available phosphorus, AK: available potassium. IS: initiate stage, ES: early stage, MS: middle stage, SS: stable stage.

4. Discussion

4.1. Impact of Grassland Desertification on Vegetation and Promoting Effect of Shrub Sand-Fixation on the Succession of Herbaceous Vegetation

In this study, the moving sand land was formerly natural grassland dominated by perennial grasses (e.g., A. cristatum and P. flaccidum) and sparsely distributed elms (U. pumila). This sparse woodland steppe represents the native vegetation type of the Horqin Sandy Land [37]. Land desertification, primarily driven by aeolian soil erosion and deposition, led to vegetation loss and soil degradation. This degradation stemmed from physical damage to plant roots and seedlings, combined with the removal of nutrient-rich fine soil particles and litter by strong winds during spring and winter [3]. These processes progressively transformed the land into mobile sand dunes. Herbaceous plants generally struggle to colonize mobile sand dunes due to soil instability and the absence of protective native vegetation. Concurrently, severe nutrient loss, particularly organic matter and nitrogen, creates unfavorable conditions for the growth and proliferation of many soil bacterial species, thereby altering the diversity and composition of the soil bacterial community [20]. During revegetation, the establishment of C. microphylla sand-fixation plantations facilitates the gradual stabilization of moving sand dunes. This stabilization reduces wind velocity and surface albedo while redistributing near-surface heat and water. The improved habitat serves as an essential prerequisite for herbaceous plant invasion. However, during the early succession stage, the sandy soil remained loose, unstable, and extremely low in organic matter, creating conditions unsuitable for the survival of most native plants. Only a few nutrient-poor adaptive, drought-resistant, and sand burial-tolerant annual species, such as Agriophyllum arenarium Bieb., Setaria viridis (L.) Beauv., Chenopodium acuminatum Willd, Cynanchum sibiricum R. BR., and Eragrostis Pilosa (L.) P.B., could establish and complete their life cycles (Table S1). Consequently, herbaceous community diversity, abundance, coverage, and biomass were all very low. The invasion of these pioneer species further stabilizes mobile surface soil through root systems and enhances soil properties. Their rapid growth and mortality increase soil organic matter input [20], gradually facilitating herbaceous community reformation and succession beneath the sand-fixation plantation.

Throughout succession, diversity, coverage, abundance, and biomass exhibited continuous increases. Perennial rhizomatous and short-rhizomatous grasses sequentially invaded, eventually becoming dominant components of the herbaceous community, a pattern consistent with Zhang et al. (2005) [37]. Annual plants characterized the early succession stage, exhibiting rapid life cycles, strong resource acquisition, but low environmental resistance. In contrast, perennial herbs dominated the stable succession stage, demonstrating greater resistance and resilience to environmental disturbance. This progression reflects niche differentiation driven by interspecific competition, which progressively shapes soil nutrient acquisition strategies [38].

4.2. Coordinated Responses of Soil Physicochemical Properties and Biological Activity in the Process of Herbaceous Vegetation Succession

Herbaceous community succession progressed concurrently with improvements in soil physical, chemical, and biological properties. Soil pH, electrical conductivity, nutrient levels (organic matter, N, P, and K), and enzymatic activities all increased along the successional gradient (Table 1; Figure 2). Revegetation-induced nutrient accumulation is influenced by multiple biotic and abiotic factors. As C. microphylla plantations developed, expanding shrub crowns captured greater amounts of litter and nutrient-rich, fine-particle dust. Concurrently, N-fixation (by soil azotobacter or plant–microbe symbionts) and N-mineralization from litter decomposition contributed to soil N enrichment [21]. Herbaceous plant invasions generated substantial net primary productivity, while plant residues provided significant inputs of organic matter, N, P, and K [4]. Consequently, the shrub–grass association in revegetated sandy lands significantly enhanced nutrient cycling and promoted biological productivity within this sandy grassland system. Soil enzymes, being highly sensitive to environmental changes and strongly correlated with soil fertility, serve as reliable indicators for assessing the impacts of degradation, restoration, and land management on soil quality. In this study, activities of urease, protease, alkaline phosphomonoesterase, glucosidase, polyphenol oxidase, and dehydrogenase all increased throughout herbaceous succession, mirroring trends in soil nutrients (Figure 2). This rise in enzymatic activity indicates accelerated mineralization of soil organic matter and enhanced cycling of key nutrients (e.g., N and P).

Overall, herbaceous community succession beneath sand-fixation plantations is intrinsically linked to soil properties and microbial abundance. Herbaceous plants colonizing these habitats enhance soil conditions and increase microbial populations; in turn, the improved soil environment supports greater plant survival. Plants initially respond to environmental changes at physiological and biochemical levels, subsequently influencing overall growth processes. They adapt to soil heterogeneity by modifying root morphology, spatial distribution patterns, and adjusting water/nutrient uptake rates. Furthermore, soil properties and key functional microbial groups (ammonia-oxidizing, N-fixing, and organic phosphorus-mineralizing bacteria) critically influence succession by affecting individual plant growth and community biomass, establishing plant–microbe symbioses that enhance plant stress resistance, and increasing soil biological activity [39]. Thus, plant–soil–microbe interactions and feedback loops constitute the fundamental drivers of herbaceous succession. These dynamics can modulate soil attributes and water/nutrient availability, influence individual plant development, and alter intra- and interspecific relationships within plant communities, and, ultimately, propel continuous structural and functional reorganization of the plant community [6,8,40,41].

4.3. Structural Responses of Soil Bacterial Community to Herbaceous Succession

Soil microorganisms are key drivers of plant community succession, directly or indirectly participating in nearly all ecological processes, particularly nutrient cycling and energy conversion [15,42,43]. They play central roles in biogeochemical transformations of soil C, N, P, and K. Soil microbial community structure exhibits distinct spatiotemporal shifts during vegetation succession, inevitably influencing vegetation composition and soil properties [44]. This study examined structural responses of soil bacterial communities to herbaceous succession, hypothesizing differences in diversity, composition, and structure across successional stages. Despite large overlaps in shared OTUs among succession stages, seven dominant phyla (Actinomycetota, Pseudomonadota, Bacillota, Bacteroidota, Myxococcota, and Acidobacteriota) were ubiquitous. However, significant differences emerged in the relative abundances of the most dominant phyla across stages. Similarly, while dominant genera (e.g., Micromonospora, Arthrobacter, Streptomyces, Solirubrobacter, Marmoricola, Methylobacterium, Nocardioides, and Corynebacterium) were shared, their relative abundances also differed significantly across stages.

Alpha diversity indices were significantly higher in vegetation-covered sites than in mobile sand land. But, no significant differences occurred among the vegetation-covered sites themselves. This phenomenon suggests that while the core taxonomic composition of soil bacterial communities in mobile sand land can recover rapidly, restoring community structure is a slower process driven primarily by shifts in the relative abundances of dominant taxa. Bacterial communities responded quantitatively to herbaceous vegetation succession because their fundamental taxonomic composition remained largely unchanged. This observation likely indicates the presence of resilient native species that can maintain compositional stability amid environmental fluctuations. Subsequent structural reorganization is driven by asymmetric population growth responses to shifts in vegetation and soil conditions. Supporting this, Jangid et al. (2011) identified land use history, rather than contemporary vegetation or soil properties, as the primary determinant of microbial community composition [45]. They also observed that disturbed communities can gradually revert toward their original states over time. Similarly, Suleiman et al. (2013) demonstrated persistent legacy effects of historical land use on present-day microbial community structure, noting that regional climatic factors may ultimately govern core community composition [46]. Consequently, secondary succession of herbaceous vegetation and associated soil changes exerted minimal influence on dominant bacterial taxa. LEfSe analysis revealed quantitative dynamics of dominant bacterial groups across succession stages. These differentially abundant taxa, highly sensitive to vegetation and soil gradients, constituted key drivers of structural shifts in the bacterial community.

Microorganisms drive soil organic matter mineralization through extracellular enzyme secretion. Enzymatic activities are strongly dependent on microbial biomass and metabolic rates. Consequently, elevated enzyme activities and organic matter content typically correspond to higher microbial abundance. While most soil bacterial taxa contribute minimally to core ecosystem functions, key functional groups, such as N-fixing, nitrifying, and organic P-mineralizing bacteria, play critical roles. These groups directly regulate soil nutrient inputs, nutrient availability, litter decomposition rates, and plant stress tolerance. The amoA, nifH, and phoD genes encode essential enzymes for nutrient cycling: ammonia monooxygenase (amoA), nitrogenase (nifH), and alkaline phosphatase (phoD), respectively [47,48,49,50]. These enzymes catalyze transformations governing N/P bioavailability. This study observed increasing abundances of all three genes along the successional gradient (Figure 7), indicating the enhanced populations of N-fixing, ammonium-oxidizing, and organic P-mineralizing bacteria and the elevated potential bioavailability of soil N/P compounds. Dominant soil amoA carriers in the revegetation area near sampling sites mainly belonged to Nitrosospira (including Cluster 3a and Cluster 6) [21]. Dominant soil nifH-carrying N-fixing genera included Skermanella, Bradyrhizobium, Azospirillum, Azohydromonas, and Mesorhizobium [51]. Dominant phoD carriers included Streptomycetaceae, Bradyrhizobium, Kribbella, and Steroidobacte [52].

4.4. Relationship Between Soil Properties and Bacterial Community During Succession

Soil constitutes the living environment for bacteria, and variations in soil properties can directly drive shifts in bacterial community structure. The RDA results in this study demonstrated that soil factors (including pH, organic matter, electrical conductivity, total N, total P, available P, and available K) significantly influenced soil bacterial community structure (Figure 8). Among these, pH and organic matter emerged as the most significant drivers, explaining 25% and 22% of the variance, respectively. Previous studies consistently report soil pH as a primary driver of bacterial community structure across geographic scales and in arable land [36,53,54]. Mendes et al. (2015) further indicated a correlation between pH and bacterial community structure during land use changes in the southeastern Amazon region [55]. The significant influence of pH likely stems from two factors: (1) its integration with other soil properties and (2) its profound effect on bacterial sensitivity to environmental change, where even slight pH variations can induce microbial stress [41,44]. Soil organic C, N, and P serve as essential nutrients for bacterial survival. Their gradual increase during vegetation succession generally promotes the growth of all bacterial groups. However, due to intra- and interspecific competition, the quantitative responses of dominant taxa to soil nutrients vary, leading to asymmetric changes in their relative abundances and, consequently, shifts in overall community structure [20]. Overall, while dominant bacterial taxa showed quantitative responses to soil improvement, the main components of the dominant soil bacterial taxa along the herbaceous plant community succession under sand-fixation plantations were only marginally affected.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated plant species composition, soil properties, and soil bacterial community structure across different stages of herbaceous community succession. Plant species richness, diversity, and biomass all increased gradually along the successional sequence. Soil nutrients (organic matter, N, P, and K) and enzymatic activities (urease, protease, alkaline phosphomonoesterase, glucosidase, polyphenol oxidase, and dehydrogenase) collectively improved. The abundances of the amoA, nifH, and phoD genes increased progressively throughout vegetation succession, contributing to the enhancement of soil nutrient levels. The process of herbaceous community succession was closely coupled with improvements in soil properties. All detected dominant bacterial phyla (e.g., Actinomycetota, Pseudomonadota, Bacillota, Bacteroidota, and Myxococcota) and genera (e.g., Micromonospora, Arthrobacter, Streptomyces, Solirubrobacter, Marmoricola, Methylobacterium, Nocardioides, and Corynebacterium) constituted shared taxa across successional stages, although their relative abundances varied. The invasion of annual plants into moving sand dunes significantly increased soil bacterial community diversity indices; however, these indices changed only slightly during subsequent herbaceous community succession. While the basic composition of the soil bacterial community in moving sand dunes could be readily and rapidly restored towards its original state, the restoration of its structure was a slow process, primarily dependent on quantitative shifts (increases and decreases) among dominant taxa. Soil pH, organic matter, electrical conductivity, total N and P, and available P and K all significantly influenced the soil bacterial community, with pH and organic matter being the most important factors. The interactive relationships among plants, soil, and microbes constituted the underlying mechanisms driving herbaceous community succession within the sand-fixation plantation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy16030342/s1, File S1: Supplementary Materials and Methods [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,56]; Figure S1: Rarefaction curves of soil bacterial high-throughput sequencing at different successional stages; Table S1: Compositions of plant communities and their relative importance values at different succession stages. Table S2: Correlations between the indices of α-diversity of bacterial community and soil properties.

Author Contributions

C.C. (Cong Chen): writing—original draft, investigation, resources, and data curation. Y.Z.: methodology and resources. Z.C.: investigation. C.C. (Chengyou Cao): writing—review and editing, writing—original draft, conceptualization, project administration, and data curation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42277467) and the Construction Project of Liaoning Provincial Key Laboratory, China (2022JH13/10200026).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Wulanaodu Desertification Combating Ecological Station, Institute of Applied Ecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, for providing experimental and relevant support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Araujo, A.S.F.; de Medeiros, E.V.; da Costa, D.P.; Pereira, A.P.D.; Mendes, L.W. From desertification to restoration in the Brazilian semiarid region: Unveiling the potential of land restoration on soil microbial properties. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, R.H.; Jiang, D.M.; Musa, A.; Zhou, Q.L.; Guo, M.X.; Wang, Y.C. Effectiveness of shrub planting and grazing exclusion on degraded sandy grassland restoration in Horqin sandy land in Inner Mongolia. Ecol. Eng. 2015, 74, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.L.; Zhou, R.L.; Su, Y.Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, L.Y.; Drake, S. Shrub facilitation of desert land restoration in the Horqin Sand Land of Inner Mongolia. Ecol. Eng. 2007, 31, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, L.; Zhou, M.; Zhao, K.; Hong, G.; Li, Z.; Liu, L.; Gao, X.; Li, Z.; Li, F. Soil microbial communities and their relationship with soil nutrients in different density Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica plantations in the Mu Us Sandy Land. Forests 2025, 16, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, J.K.; Schweitzer, J.A. The rise of plant-soil feedback in ecology and evolution. Funct. Ecol. 2016, 30, 1030–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dostal, P. The temporal development of plant-soil feedback is contingent on competition and nutrient availability contexts. Oecologia 2021, 196, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marasco, R.; Ramond, J.B.; Van Goethem, M.W.; Rossi, F.; Daffonchio, D. Diamonds in the rough: Dryland microorganisms are ecological engineers to restore degraded land and mitigate desertification. Microb. Biotechnol. 2023, 16, 1603–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.A.; Klironomos, J. Mechanisms of plant-soil feedback, interactions among biotic and abiotic drivers. New Phytol. 2019, 222, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.A.; Collins, S.L.; Rudgers, J.A. Connecting plant-soil feedbacks to long-term stability in a desert grassland. Ecology 2019, 100, e02756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, T.A.F.; de Andrade, L.A.; Freitas, H.; Sandim, A.D. Biological invasion influences the outcome of plant-soil feedback in the invasive plant species from Brazilian semi-arid. Microb. Ecol. 2018, 76, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gundale, M.J.; Kardol, P. Multi-dimensionality as a path forward in plant-soil feedback research. J. Ecol. 2021, 109, 3446–3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rillig, M.C.; Ryo, M.; Lehmann, A.; Aguilar-Trigueros, C.A.; Buchert, S.; Wulf, A.; Iwasaki, A.; Roy, J.; Yang, G.W. The role of multiple global change factors in driving soil functions and microbial biodiversity. Science 2019, 366, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Long, J.R.; Fry, E.L.; Veen, G.F.; Kardol, P. Why are plant–soil feedbacks so unpredictable, and what to do about it? Funct. Ecol. 2019, 33, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekberg, Y.; Bever, J.D.; Bunn, R.A.; Callaway, R.M.; Hart, M.M.; Kivlin, S.N.; Klironomos, J.; Larkin, B.G.; Maron, J.L.; Reinhart, K.O.; et al. Relative importance of competition and plant–soil feedback, their synergy, context dependency and implications for coexistence. Ecol. Lett. 2018, 21, 1268–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araujo, A.S.F.; Zhao, T.C.; Pellizzer, E.P.; de Medeiros, E.V.; da Costa, D.P.; Mendes, L.W.; Melo, V.M.M.; Pereira, A.P.D.; Salles, J.F. Restoration strategies shape ecological processes driving dominant and rare bacterial communities in soils under desertification in the Brazilian semiarid. J. Environ. Manag. 2026, 397, 128351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- In ’t Zand, D.; Herben, T.; van den Brink, A.; Visser, E.J.W.; de Kroon, H. Species abundance fluctuations over 31 years are associated with plant-soil feedback in a species-rich mountain meadow. J. Ecol. 2021, 109, 1511–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Zhai, J.; He, M.; Ma, R.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Guo, J.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Bai, J. Linking soil properties and bacterial communities with organic matter carbon during vegetation succession. Plants 2025, 14, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, A.S.F.; de Medeiros, E.V.; da Costa, D.P.; Mendes, L.W.; Cherubin, M.R.; Neto, F.D.; Beirigo, R.M.; Lambais, G.R.; Melo, V.M.M.; Nobrega, G.G.; et al. Caatinga Microbiome Initiative: Disentangling the soil microbiome across areas under desertification and restoration in the Brazilian drylands. Restor. Ecol. 2025, 33, e14298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Liang, D.; Zhou, W.; Xu, Q.; Xiang, M.; Gu, Y.; Siddique, K.H.M. Soil, plant, and microorganism interactions drive secondary succession in alpine grassland restoration. Plants 2024, 13, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, Z. Successions of bacterial and fungal communities in biological soil crust under sand-fixation plantation in Horqin Sandy Land, Northeast China. Forests 2024, 15, 1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, L.; Liang, C.P.; Feng, S.W.; Cao, C.Y. Effects of artificial sand-fixing plantations on ammonia-oxidizing bacterial community in Horqin Sand Land. Chin. J. Ecol. 2019, 38, 3235–3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koorem, K.; Snoek, B.L.; Bloem, J.; Geisen, S.; Kostenko, O.; Manrubia, M.; Ramirez, K.S.; Weser, C.; Wilschut, R.A.; van der Putten, W.H. Community-level interactions between plants and soil biota during range expansion. J. Ecol. 2020, 108, 1860–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trivedi, C.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Hamonts, K.; Lai, K.T.; Reich, P.B.; Singh, B.K. Losses in microbial functional diversity reduce the rate of key soil processes. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2019, 135, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippot, L.; Chenu, C.; Kappler, A.; Rillig, M.C.; Fierer, N. The interplay between microbial communities and soil properties. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 22, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; FAO/IUSS Working Group WRB. World Reference Base for Soil Resources 2006; World Soil Resources Reports; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2006; Volume 103. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.M.; Shou, W.K.; Qian, J.Q.; Wu, J.; Busso, C.A.; Hou, X.Z. Level of habitat fragmentation determines its non-linear relationships with plant species richness, frequency and density at desertified grasslands in Inner Mongolia, China. J. Plant Ecol. 2019, 11, 866–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.Y. Guidance of Soil Science Experiment; China Forestry Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2004; pp. 45–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kandeler, E.; Gerber, H. Short-term assay of soil urease activity using colorimetric determination of ammonium. Biol. Fertil. Soils 1988, 6, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabatabai, M.A. Soil enzymes. In Methods of Soil Analysis; Page, A.L., Millar, E.M., Keeney, D.R., Eds.; ASA and SSSA: Madison, WI, USA, 1982; pp. 501–538. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd, J.N.; Butler, J.H.A. Short-term assays of soil proteolytic enzyme activities using proteins and dipeptide derivatives as substrates. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1972, 4, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perucci, P.; Casucc, C.; Dumontet, S. An improved method to evaluate the o-diphenol oxidase activity of soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2000, 32, 1927–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.H.; Zheng, H.Y. Manual of Analytical Methods of Soil Microorganism; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 1986; pp. 266–269. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Soil Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences (ISSCAS). Methods on Soil Microorganism Study; Science Press: Beijing, China, 1985; pp. 260–275. [Google Scholar]

- Poly, F.; Ranjard, L.; Nazaret, S.; Gourbière, F.; Monrozier, L.J. Comparison of nifH gene pools in soils and soil microenvironments with contrasting properties. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 67, 2255–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotthauwe, J.H.; Witzel, K.P.; Liesack, W. The ammonia monooxygenase structural gene amoA as a functional marker, Molecular fine-scale analysis of natural ammonia-oxidizing populations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997, 63, 4704–4712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragot, S.A.; Kertesz, M.A.; Bünemann, E.K. phoD alkaline phosphatase gene diversity in soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 7281–7289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, X.; Drake, S. Community succession along a chronosequence of vegetation restoration on sand dunes in Horqin Sandy Land. J. Arid Environ. 2005, 62, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Long, J.R.; Heinen, R.; Jongen, R.; Hannula, S.E.; Huberty, M.; Kielak, A.M.; Steinauer, K.; Bezemer, T.M. How plant-soil feedbacks influence the next generation of plants. Ecol. Res. 2021, 36, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagg, C.; Schlaeppi, K.; Banerjee, S.; Kuramae, E.E.; van der Heijden, M.G.A. Fungal-bacterial diversity and microbiome complexity predict ecosystem functioning. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldorfová, A.; Knobová, P.; Münzbergová, Z. Plant-soil feedback contributes to predicting plant invasiveness of 68 alien plant species differing in invasive status. Oikos 2020, 129, 1257–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Y.; Ai, Z.M.; Xu, H.W.; Liu, H.F.; Wang, G.L.; Deng, L.; Liu, G.B.; Xue, S. Plant-microbial feedback in secondary succession of semiarid grasslands. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 760, 143389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleine, C.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Diruggiero, J.; Guirado, E.; Harfouche, A.L.; Perez-Fernandez, C.; Singh, B.K.; Selbmann, L.; Egidi, E. Dryland microbiomes reveal community adaptations to desertification and climate change. ISME J. 2024, 18, wrae056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawi, F. How Can we stabilize soil using microbial communities and mitigate desertification? Sustainability 2023, 15, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, Z.B.; Feng, S.W.; Wang, T.T.; Ren, Q. Soil bacterial community responses to revegetation of moving sand dune in semi-arid grassland. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 6217–6228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangid, K.; Williams, M.A.; Franzluebbers, A.J.; Schmidt, T.M.; Coleman, D.C.; Whitman, W.B. Land-use history has a stronger impact on soil microbial community composition than aboveground vegetation and soil properties. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 2184–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleiman, A.K.A.; Manoeli, L.; Boldo, J.T.; Pereira, M.G.; Roesch, L.F.W. Shifts in soil bacterial community after eight years of land-use change. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 36, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junier, P.; Molina, V.; Dorador, C.; Hadas, O.; Kim, O.S.; Junier, T.; Witzel, K.P.; Imhoff, J.F. Phylogenetic and functional marker genes to study ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms (AOM) in the environment. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 85, 425–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragot, S.A.; Huguenin-Elie, O.; Kertesz, M.A.; Frossard, E.; Bunemann, E.K. Total and active microbial communities and phoD as affected by phosphate depletion and pH in soil. Plant Soil 2016, 408, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, B.L.; Cheesman, A.W.; Condron, L.M.; Reitzel, K.; Richardson, A.E. Introduction to the special issue, developments in soil organic phosphorus cycling in natural and agricultural ecosystems. Geoderma 2015, 257, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehr, J.P.; Jenkins, B.D.; Short, S.M.; Steward, G.F. Nitrogenase gene diversity and microbial community structure, a cross-system comparison. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 5, 539–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cui, Y.N.; Cao, C.Y. Effects of revegetation on soil nitrogen-fixation and carbon-fixation microbial communities in the Horqin Sandy Land, China. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2024, 35, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.N.; Cui, Z.B.; Cao, C.Y. Sand-fixation plantation type affects soil phosphorus transformation microbial community in a revegetation area of Horqin Sandy Land, Northeast China. Ecol. Eng. 2022, 180, 106644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.J.; Xia, Y.H.; Sun, Q.; Liu, K.P.; Chen, X.B.; Ge, T.D.; Zhu, B.L.; Zhu, Z.K.; Zhang, Z.H.; Su, Y.R. Effects of long-term fertilization on phoD-harboring bacterial community in karst soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 628–629, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakelin, S.A.; Macdonald, L.M.; Rogers, S.L.; Gregg, A.L.; Bolger, T.P.; Baldock, J.A. Habitat selective factors influencing the structural composition and functional capacity of microbial communities in agricultural soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2008, 40, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, L.W.; Brossi, M.J.D.; Kuramae, E.E.; Tsai, S.M. Land-use system shapes soil bacterial communities in Southeastern Amazon region. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 2015, 95, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.Y.; Jiang, D.M.; Teng, X.H.; Jiang, Y.; Liang, W.J.; Cui, Z.B. Soil chemical and microbiological properties along a chronosequence of Caragana microphylla Lam. plantations in the Horqin Sandy Land of Northeast China. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2008, 40, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.