Abstract

Brazil nut (Bertholletia excelsa Bonpl.) is a major non-timber forest product in the Amazon, supporting extractivist communities in Brazil, Bolivia, and Peru and contribute to forest conservation. Unlike other extractive products, Brazil nut production has not declined under commercial use and is recognized for its socioeconomic and environmental importance. Precision agriculture has been transformed by the use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and artificial intelligence (AI), which enable monitoring efficiency and yield estimation in several crops, including the Brazil nut. This study assessed the potential of using UAV-based imagery combined with YOLOv8 object detection model to identify and quantify Brazil nut fruits in a native forest fragment in eastern Acre, Brazil. A UAV was used to capture canopy images of 20 trees with varying diameters at breast height. Images were manually annotated and used to train the YOLOv8 with an 80/20 split for training and validation/testing. Model performance was evaluated using precision, recall, F1-score, and mean Average Precision (mAP). The model achieved recall above 90%, with an F1-score of 0.88, despite challenges from canopy complexity and partial occlusion. These results indicate that UAV-based imagery combined with AI detection provides an approach for estimating Brazil nut yield, reducing manual effort and improving market strategies for extractivist communities. This technology supports sustainable forest management and socioeconomic development in the Amazon.

1. Introduction

The Brazil nut (Bertholletia excelsa Bonpl.) is one of the most economically important native tree species in the Amazon forest. It ranks first among carbon-sequestering and third in biomass storage [1]. Its seeds are widely traded in local, regional, and international markets, making extractivism a key source of income for thousands of families through the Amazon region [2]. Beyond its economic importance, Brazil nut extraction contributes to forest conservation by maintaining native vegetation and reducing deforestation [3].

The exploitation of native stands is considered an important strategy for both forest conservation and socioeconomic development [3]. Moreover, the species shows potential for reforestation projects due to its high tolerance to regional climatic conditions [1]. The Brazil nut value chain sustains more than 60,000 families of Indigenous and traditional farmers and is supported by over 100 third-sector organizations, most of which are dedicated to primary processing. Despite being the main non-timber forest product of the Amazon, this chain still presents pre-capitalist labor relations and regional market monopolies [4].

Bertholletia excelsa is an equatorial species that can reach heights of up to 60 m. It belongs to the Lecythidaceae family and is the only species of the genus Bertholletia [5,6]. Its primary product of commercial interest is the edible nut, although its durable wood and fruit husks, used in infusions, also have value [3]. Between January and November 2024, Brazil nut exports reached approximately USD 9.6 million, while national production reached 35,351 tons, generating an estimated value of BRL 172,252,000.00 [7].

The accurate detection and quantification of Brazil nut kernels in the canopy is essential for pricing Brazil nut kernels. Yield estimation is influenced by seasonal variation, climatic factors, and management factors [2,8], especially in dense forest areas [9,10]. Traditional methods require significant manual effort and time [11], limiting their applicability in large monitoring. In this context, technological advances in precision agriculture have introduced unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and artificial intelligence (AI) as tools for crop monitoring and yield prediction, enabling more precise and efficient assessment of individual tree productivity [12,13]. These tools not only allow fruit identification and counting but also generate georeferenced data [14], which supports the long-term monitoring of collection areas and evaluation of productive potential [15]. This information contributes to decision-making [16] by allowing specialists to more accurately estimate the volume available for commercialization and to adjust prices according to real market supply, reducing the risks of under- or overvaluation. Moreover, these technologies enable high-resolution image acquisition and automated fruit detection, improving efficiency and reducing costs [17,18]. Recent studies have demonstrated their effectiveness in tropical forests [19,20], highlighting their potential for the real-time monitoring of species and for optimizing production logistics [21]. For example, Xiong et al. [22] applied convolutional neural networks to UAV imagery for tree crown identification in tropical forests. Similarly, Almeida et al. [17] demonstrated that multispectral sensors combined with deep learning algorithms produced robust outcomes in tree counting, even in complex environments like the Amazon.

Despite these advances, challenges persist in adapting these methods to unmanaged forest areas, where dense canopies and occlusion hinder accurate detection [23]. This study investigates the effectiveness of using UAV imagery combined with a YOLO object detection model to detect and quantify Brazil nut fruits in native forest areas in eastern Acre, Brazil. The approach aims to improve traditional labor-intensive methods by providing more accurate harvest estimates and supporting sustainable forest management. The reliable production estimation is essential for planning harvest and pricing strategies, as current practices often rely on approximate predictions. Manual fruit counting in dense forest environments is time-consuming and prone to error, limiting its use for large-scale monitoring. To address these challenges, a dataset was created from UAV imagery to enable automated detection and quantification of Brazil nut fruits under natural conditions. This dataset provides a base for applying object detection models to improve efficiency and accuracy in yield estimation. In this context, the main contributions of this study are as follows: creating a UAV-based dataset of Brazil nut tree canopies for fruit detection in native Amazonian forests; assessing the feasibility of using an object detection network to identify and quantify Brazil nut burrs from UAV imagery; and analyzing the detection performance under real-world conditions, considering challenges such as canopy complexity and partial occlusion.

2. Materials and Methods

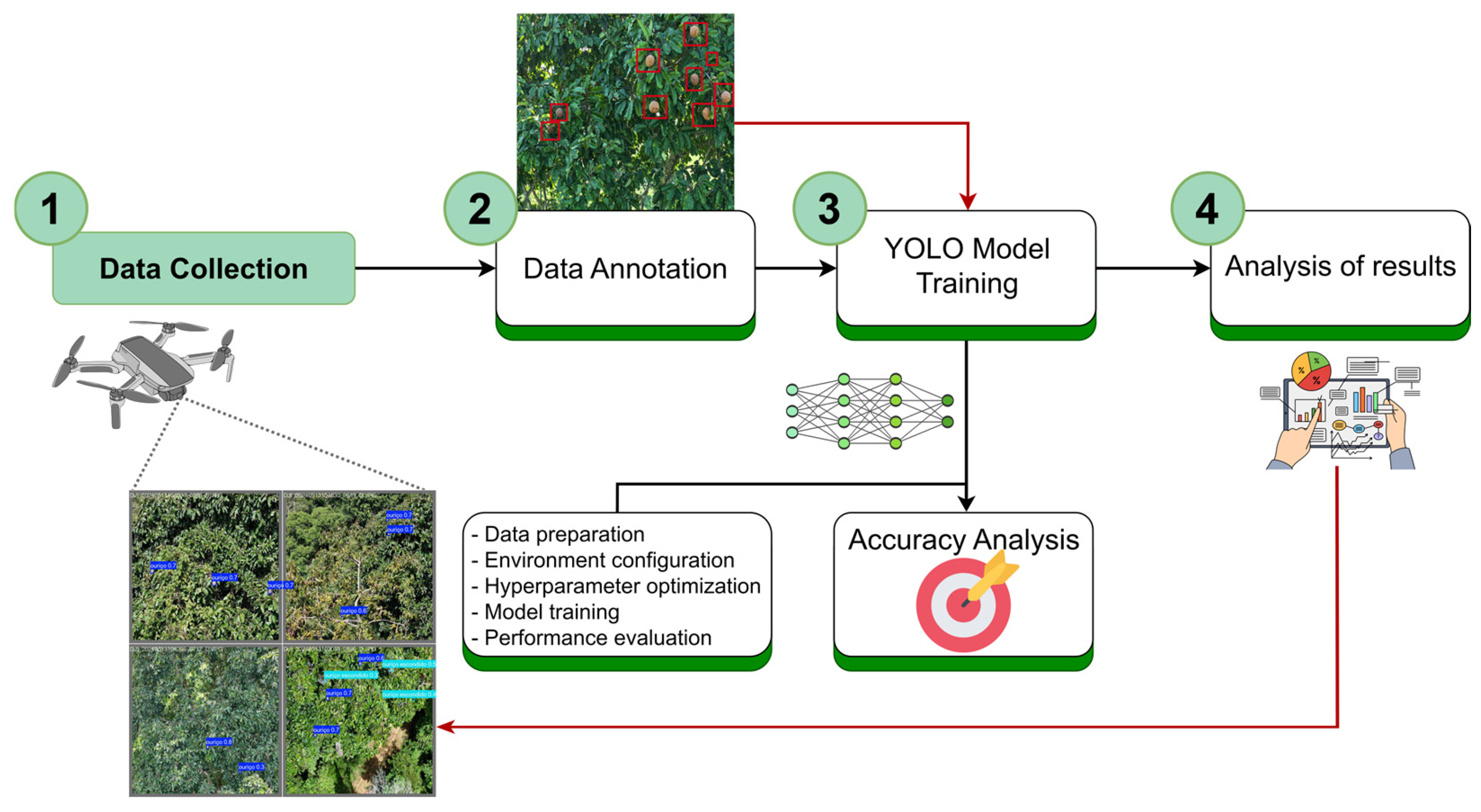

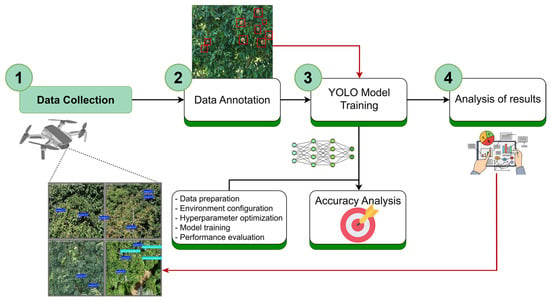

The workflow adopted in this study is presented in Figure 1. The pipeline is composed of four main steps: (1) data collection using a UAV; (2) data annotation and dataset preparation; (3) YOLO model training; and (4) performance analysis of the trained model. Each step is described in the following subsections.

Figure 1.

Workflow for Brazil nut detection in imagery acquired from unmanned aerial vehicles using YOLOv8: (1) data collection; (2) data annotation; (3) model training; and (4) performance analysis.

2.1. Dataset Description

A dataset was created from UAV imagery to enable automated detection and quantification of Brazil nut fruits under natural conditions.

2.1.1. Study Area

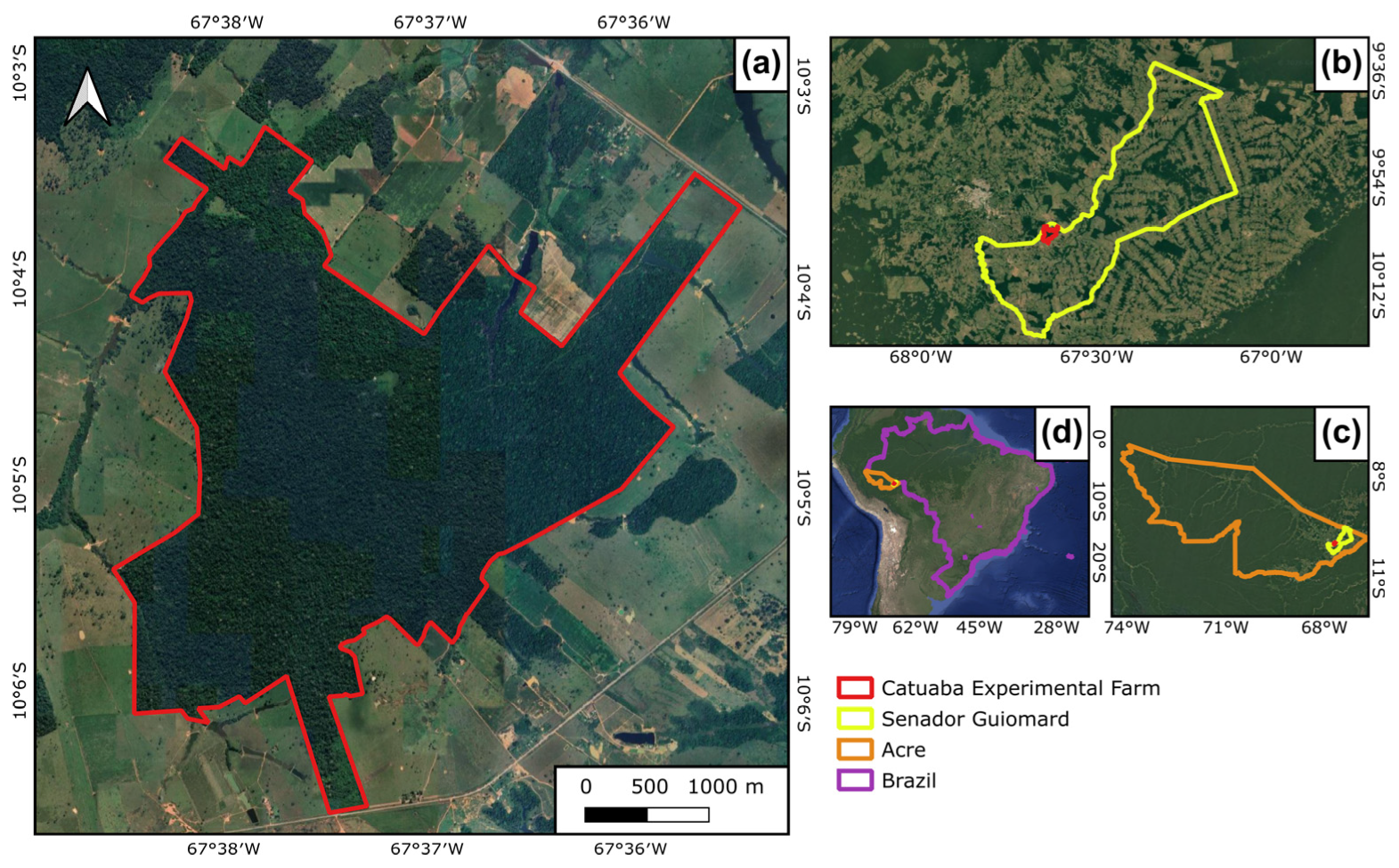

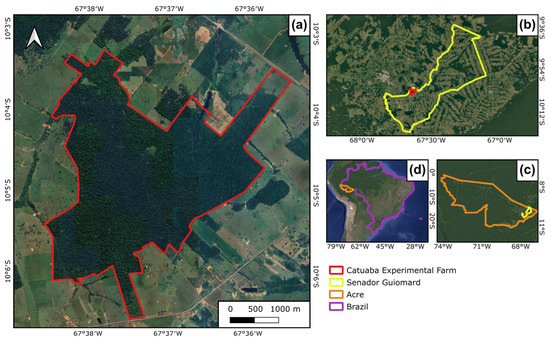

The study was conducted in a forest fragment at the Catuaba Experimental Farm (FE) of the Federal University of Acre, located in the municipality of Senador Guiomard, eastern Acre (10°04′ S 67°37′ W, Figure 2). The farm covers approximately 850 hectares. The regional climate has two distinct seasons: a rainy season from October to April and a dry season from April to October, with precipitation occurring during about 75% of the year. The mean annual temperature ranges from 22 to 24 °C, and mean annual precipitation is 1973 mm [24].

Figure 2.

Location of the study area at the Catuaba Experimental Farm: (a) study site; (b) municipality of Senador Guiomard; (c) Acre Sate; (d) Brazil.

2.1.2. Data Collection

A DJI Mavic 3 Pro (DJI, Shenzhen, China) was used for image acquisition. The UAV is equipped with three imaging sensors: a Hasselblad camera (CMOS 4/3, 20 MP), a medium telephoto camera (CMOS 1/1.3″, 48 MP), and a telephoto camera (CMOS 1/2″, 12 MP) [25]. The flights were manually operated between 8:00 and 11:00 to capture images of Bertholletia excelsa canopies at upper, middle, and, when possible, lower levels.

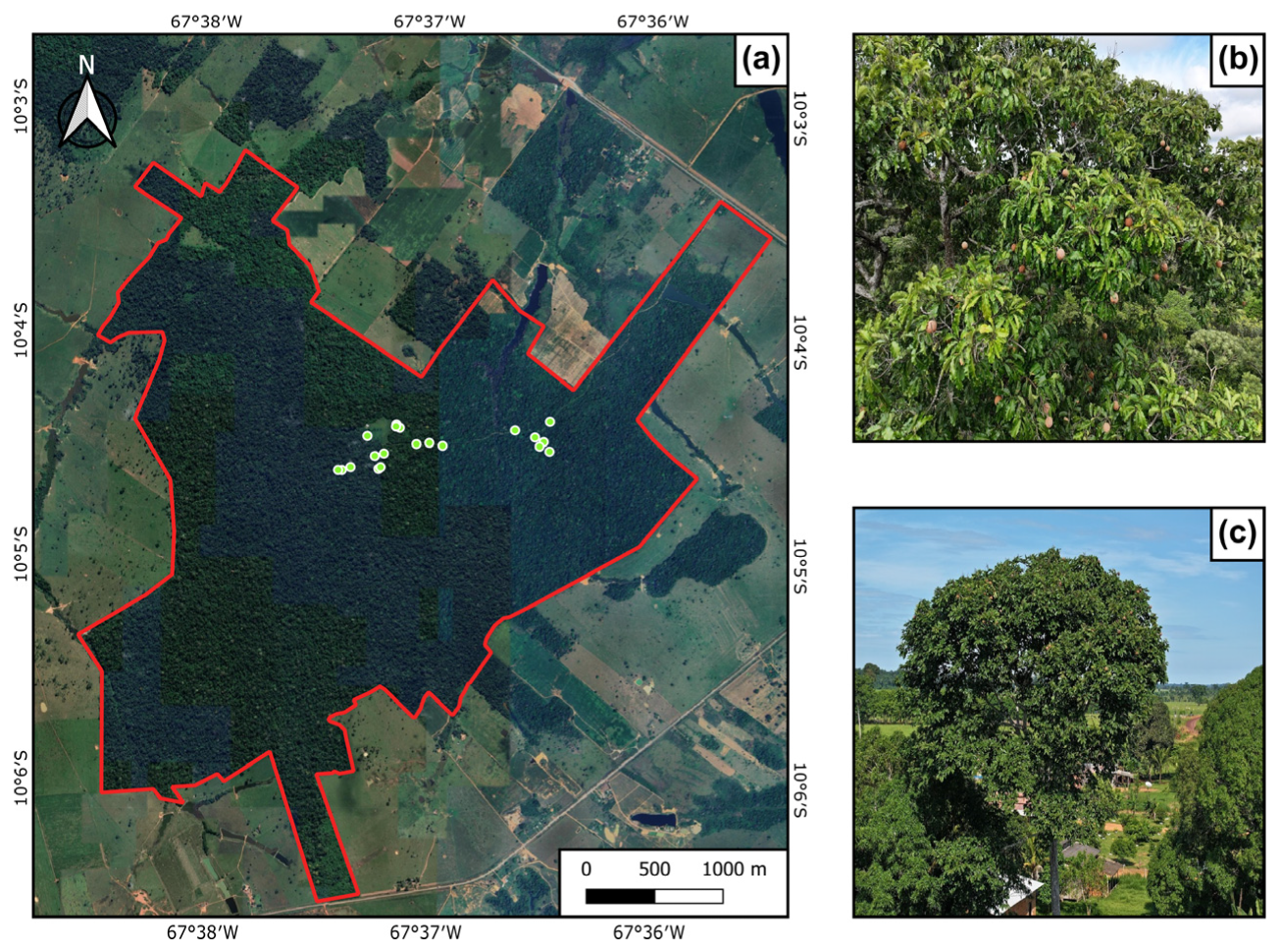

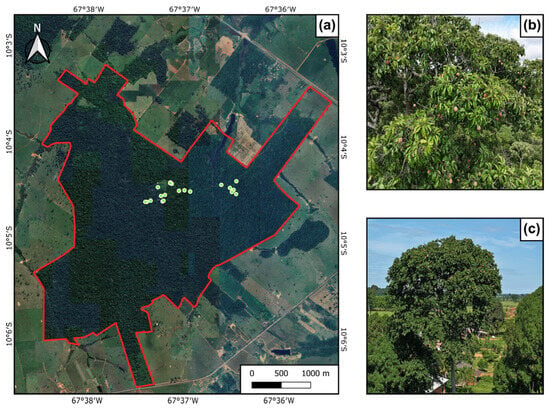

Twenty Brazil nut trees were selected based on canopy exposure to ensure sufficient crown visibility (Figure 3a). For each tree (Figure 3c), its coordinates and diameter at breast height (DBH) were recorded, ranging from 1.76 to 5.40 m. Flight surveys covered the upper, middle, and lower canopy portions at orbital distances of 4–8 m from the crown, as presented in Figure 3b. As in most cases, neighboring trees obstructed the lower canopy, and images were collected only when visibility conditions permitted.

Figure 3.

Distribution of sampled individuals at Catuaba Experimental Farm (a), representative canopy image acquired with UAV (b), and Brazil nut tree photograph (c).

2.1.3. Data Augmentation and Data Annotation

After image selection, 875 photographs were chosen based on clarity, fruit visibility, and low noise. Images were selected to represent real-world challenges such as partial occlusion caused by overlapping branches and leaves. Lighting conditions varied due to natural illumination changes during morning flights, introducing shadows and bright spots.

To increase dataset diversity and reduce overfitting, data augmentation techniques were applied, including image rotation at different angles, noise addition, sharpness variation, zooming, and cropping [26]. Processing was performed in Google Colab, resulting in a final dataset of 2000 images for training. Original UAV images (4032 × 3024 pixels) were resized to 640 × 640 pixels to standardize inputs and avoid confusion during training [27]. Annotation was performed using Make Sense AI (https://www.makesense.ai/, accessed on 20 June 2024), labeling fruits as “burr” class with bounding boxes, as shown in Figure 4. The tool allows us to export annotations in a YOLO-compatible format, compatible for model training.

Figure 4.

Annotation of the “burr” class of Bertholletia excelsa fruits using Make Sense Ai.

2.2. Model Description

The YOLOv8 [28] model was trained on the annotated dataset, using the Ultralytics framework (PyTorch 2.6.0) in a Python 3.13 environment managed with Anaconda 2023.07 (Anaconda, Inc., 2023). GPU acceleration was enabled through the CUDA Toolkit (version 11.2). The Ultralytics package was installed from the official repository, and training was executed with the standard YOLOv8 CLI. Training data were organized in YOLO format, with images and label files stored in separate directories. Additional packages included OpenCV for image processing [29], NumPy for array manipulation [30], Pandas for data handling [31], Matplotlib 3.9.2 [32], Seaborn 0.13.2 [33], and Scikit-learn [34] for metric computation.

YOLOv8 was selected because it was widely adopted and well-documented at the time of experimentation, offering improvements over previous YOLO versions in detection accuracy and computational efficiency [35]. Although newer versions have since been introduced with incremental performance gains, YOLOv8 remains a strong baseline for feasibility studies and provides a practical balance between accuracy and resource requirements for UAV-based applications. Some studies have also reported that YOLOv8 provided a competitive or better performance when compared to newer versions in using UAV-based imagery applications in forestry and agronomy contexts [36,37].

2.3. Model Training and Evaluation

The dataset was split into training (80%), validation (10%), and testing (10%) sets, corresponding to 1600 images for training and 400 for validation and testing. Model training was executed for 300 epochs with patience set to 300 to prevent early stopping. Table 1 summarizes the training parameters used.

Table 1.

Parameters used in YOLOv8 model training.

Model performance was evaluated using the validation set, comparing predictions with annotated ground-truth labels and by analyzing the confusion matrix [38]. The performance metrics included precision, recall, F1-score, and mean Average Precision (mAP) [39]. Precision measures the proportion of correct predictions among all predicted detections, while recall measures the proportion of actual objects correctly detected. The F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a balanced measure of accuracy, and mAP was calculated at different Intersection over Union (IoU) thresholds to assess overall detection performance.

3. Results

3.1. Detection Results

Table 2 summarizes the classification performance for the detection of Brazil nut burrs. The model correctly identified 2371 burrs (true positives), while 427 false positives and 259 false negatives were recorded. Based on these values, the normalized confusion matrix indicates that 90% of the burrs were correctly detected, with 10% missed or incorrectly predicted. Precision was 0.847, meaning that 84.7% of the predicted burs were correct, while recall reached 0.902, indicating that 90.2% of actual burrs were detected. The F1-score was 0.874, confirming strong overall performance. Most errors were due to false positives and missed detections, likely caused by canopy density and partial burr occlusion. True negatives were not applicable because the YOLO model was trained for single-class detection.

Table 2.

Performance metrics for Brazil nut fruit (burr) detection using the YOLOv8 model.

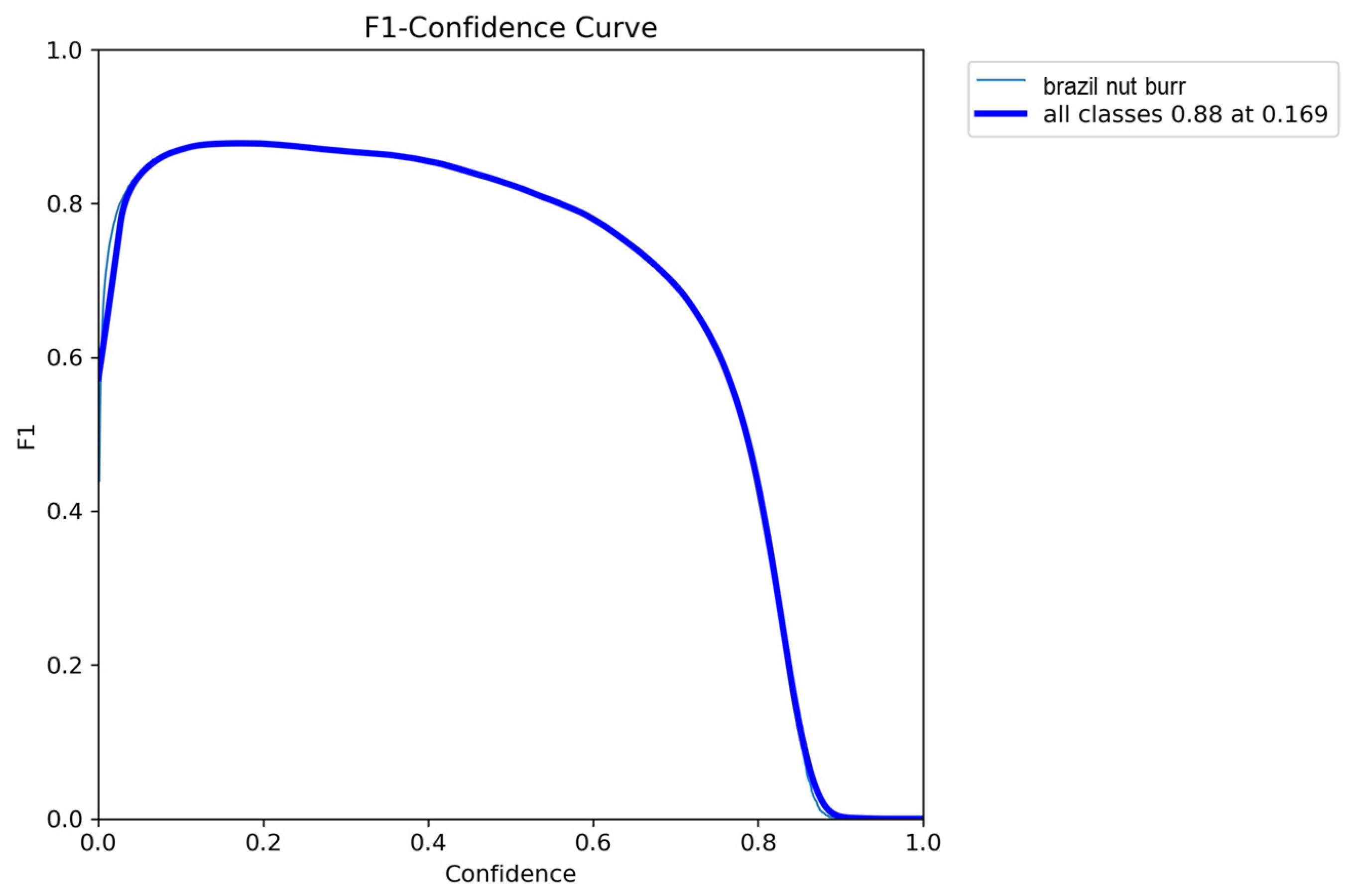

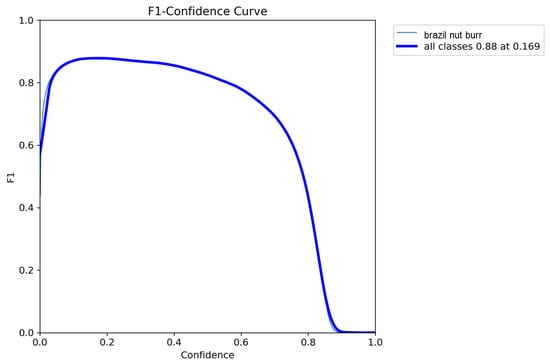

The F1–confidence curve (Figure 5) shows how the F1-score varies with prediction confidence. The burr class reached an F1-score of 0.88 at a confidence of 16.9%, indicating relatively low confidence but high precision. The curve shows a rapid initial increase in F1-score, stabilizing near 0.88, before declining at higher thresholds. These results identify the optimal confidence threshold for balancing precision and recall in Brazil nut burr detection.

Figure 5.

F1–confidence curve for the “burr” class.

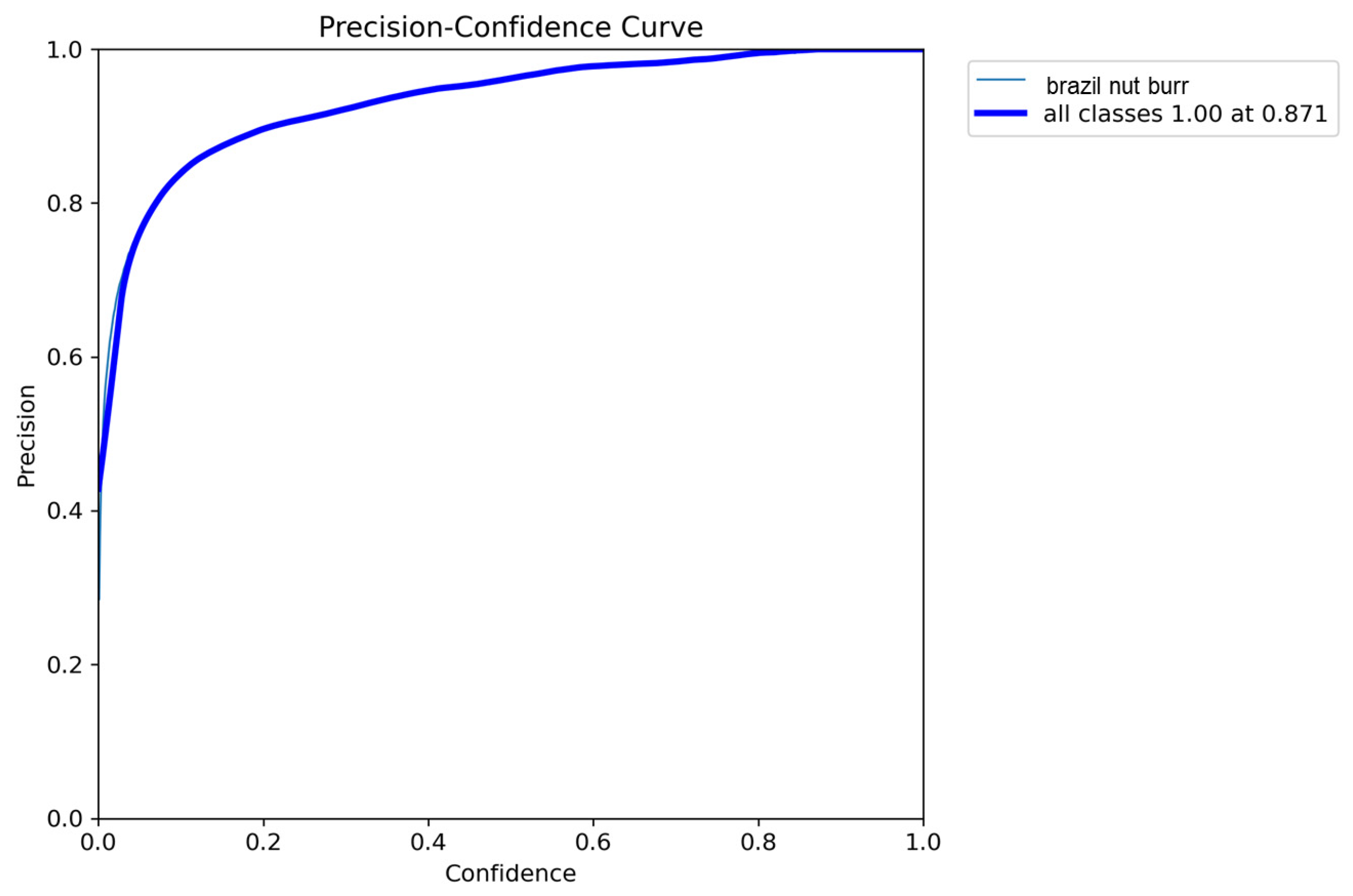

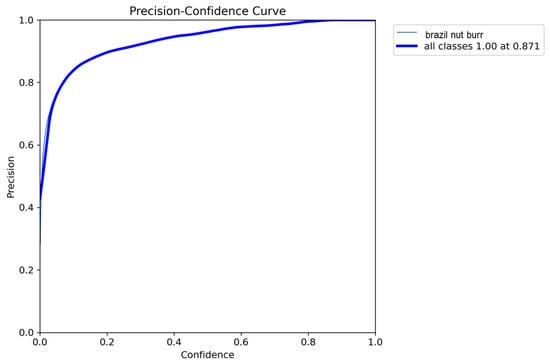

The precision–confidence curve (Figure 6) indicates that precision approached 1.0 at a confidence threshold of 0.871, remaining stable at higher confidence levels. This suggests indicate that the model achieves reliable detections when using a cutoff near this threshold.

Figure 6.

Precision–confidence curve for Brazil nut fruit detection.

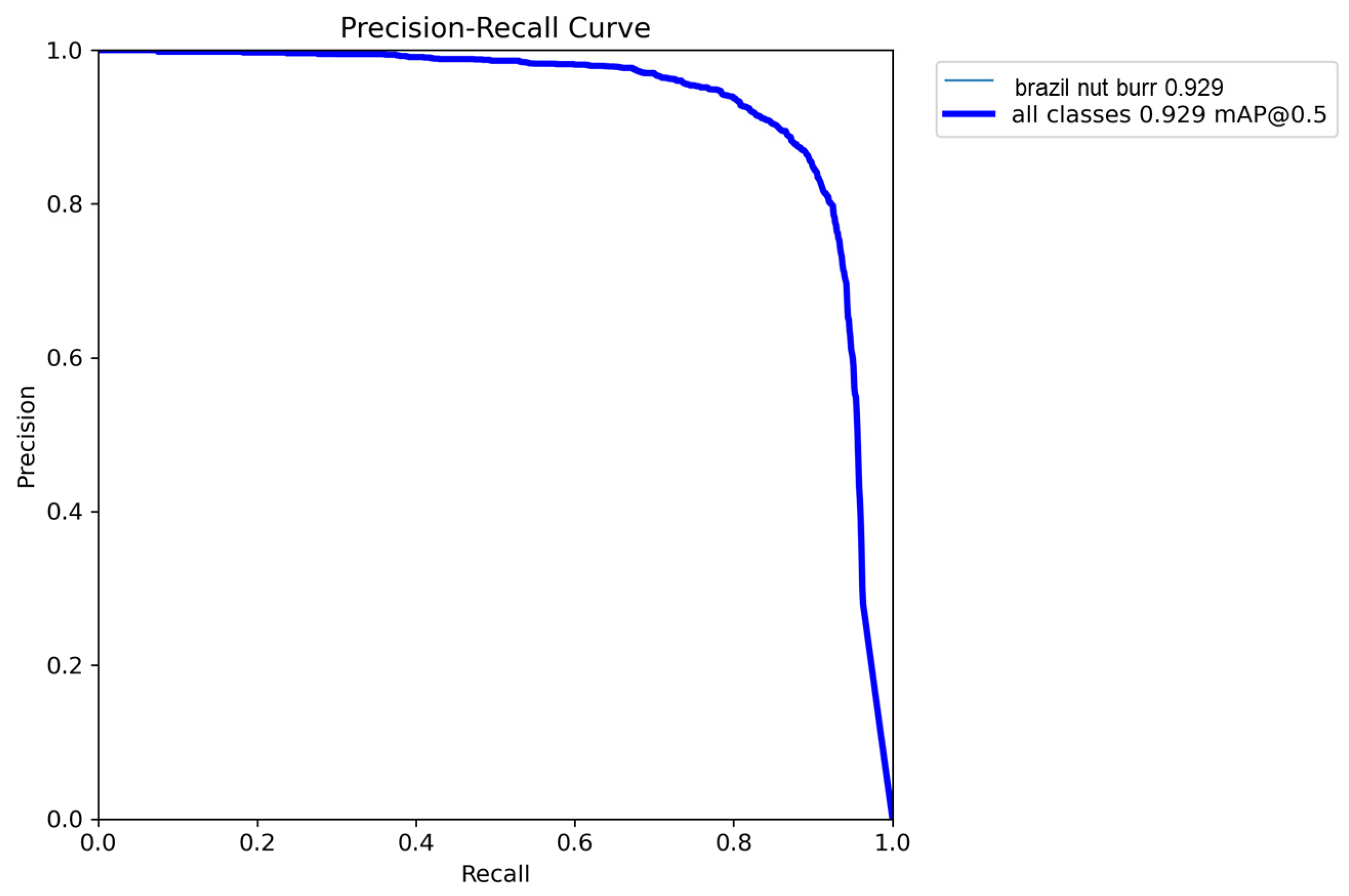

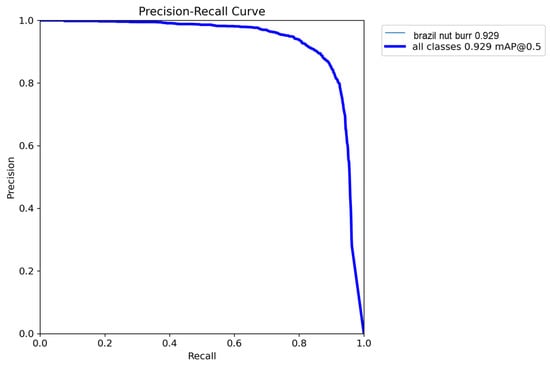

The precision–recall curve (Figure 7) presents the trade-off between precision and recall at different thresholds. It demonstrates a performance balance, with the model reaching 92.9% at the mAP@0.5 threshold.

Figure 7.

Precision–recall curve for the “burr” class.

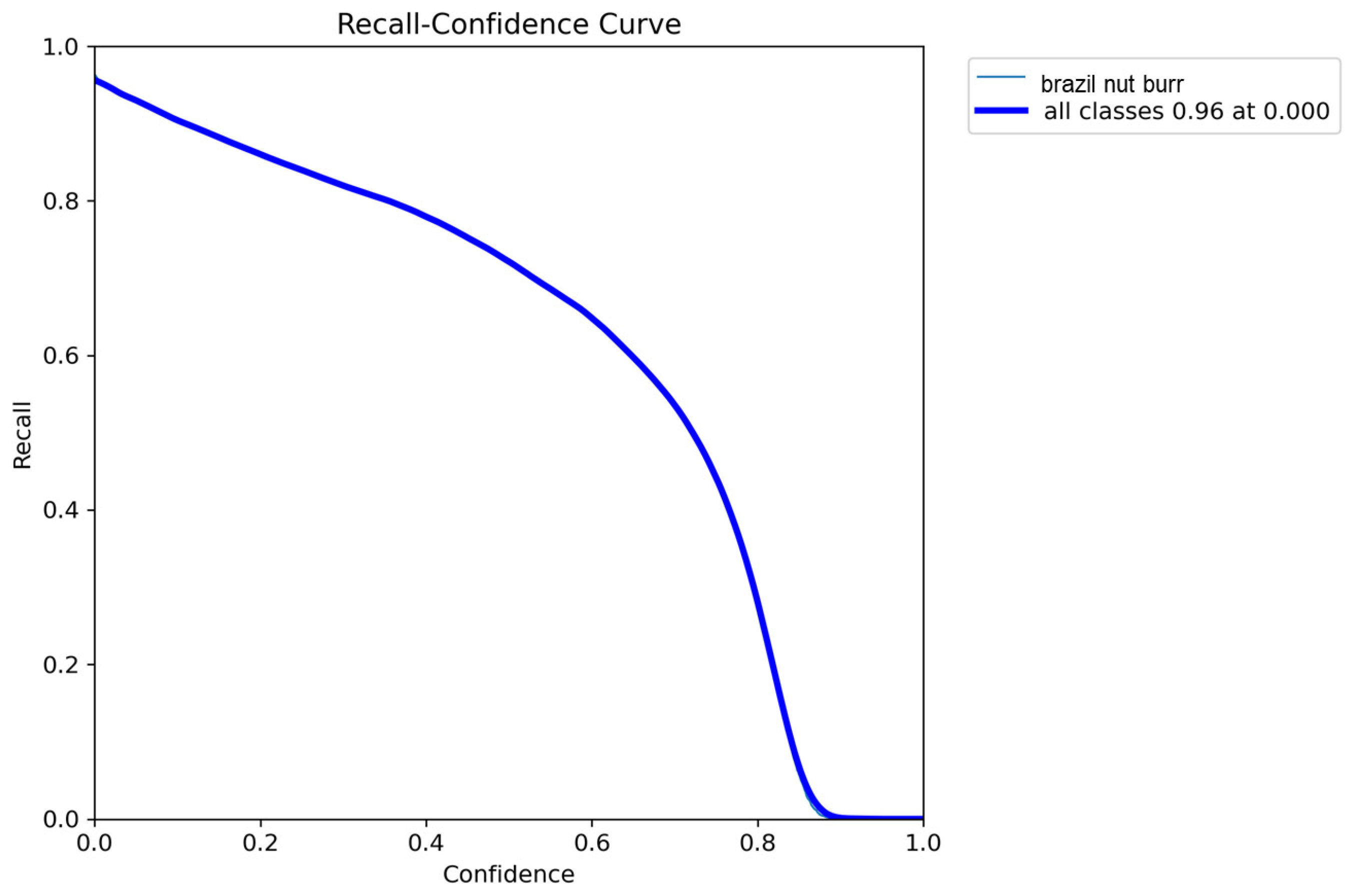

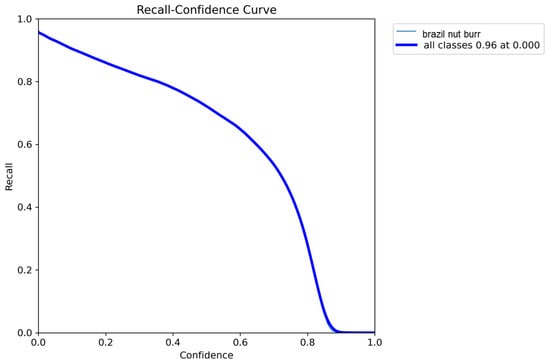

The recall–confidence curve (Figure 8) shows how recall changes with prediction confidence. Recall was highest (0.95) at low confidence levels and decreased gradually as confidence increased, approaching zero near the maximum threshold. These results demonstrate that the model achieves high recall at lower confidence levels, reflecting greater sensitivity in detecting Brazil nut fruits.

Figure 8.

Recall–confidence curve for the “burr” class.

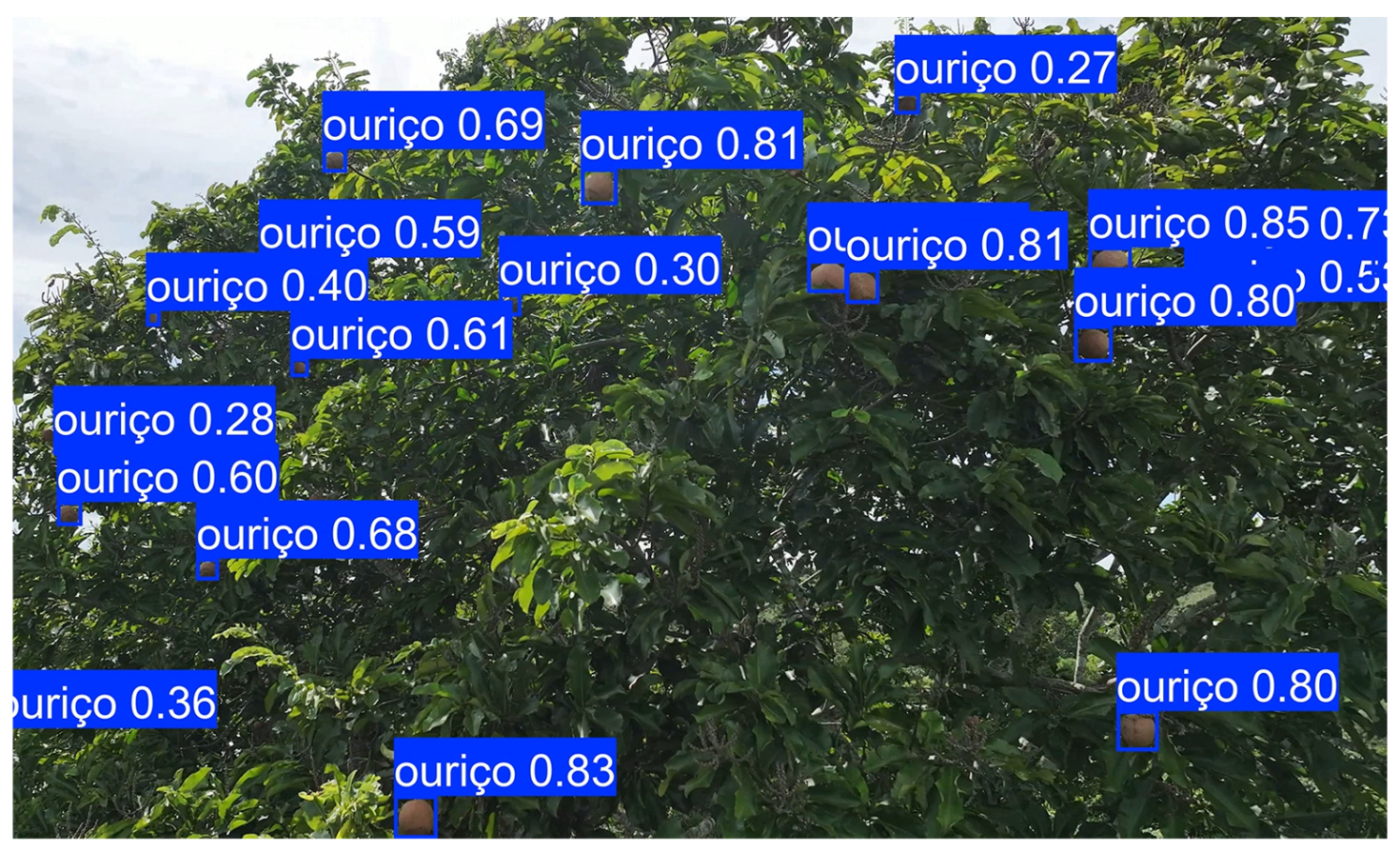

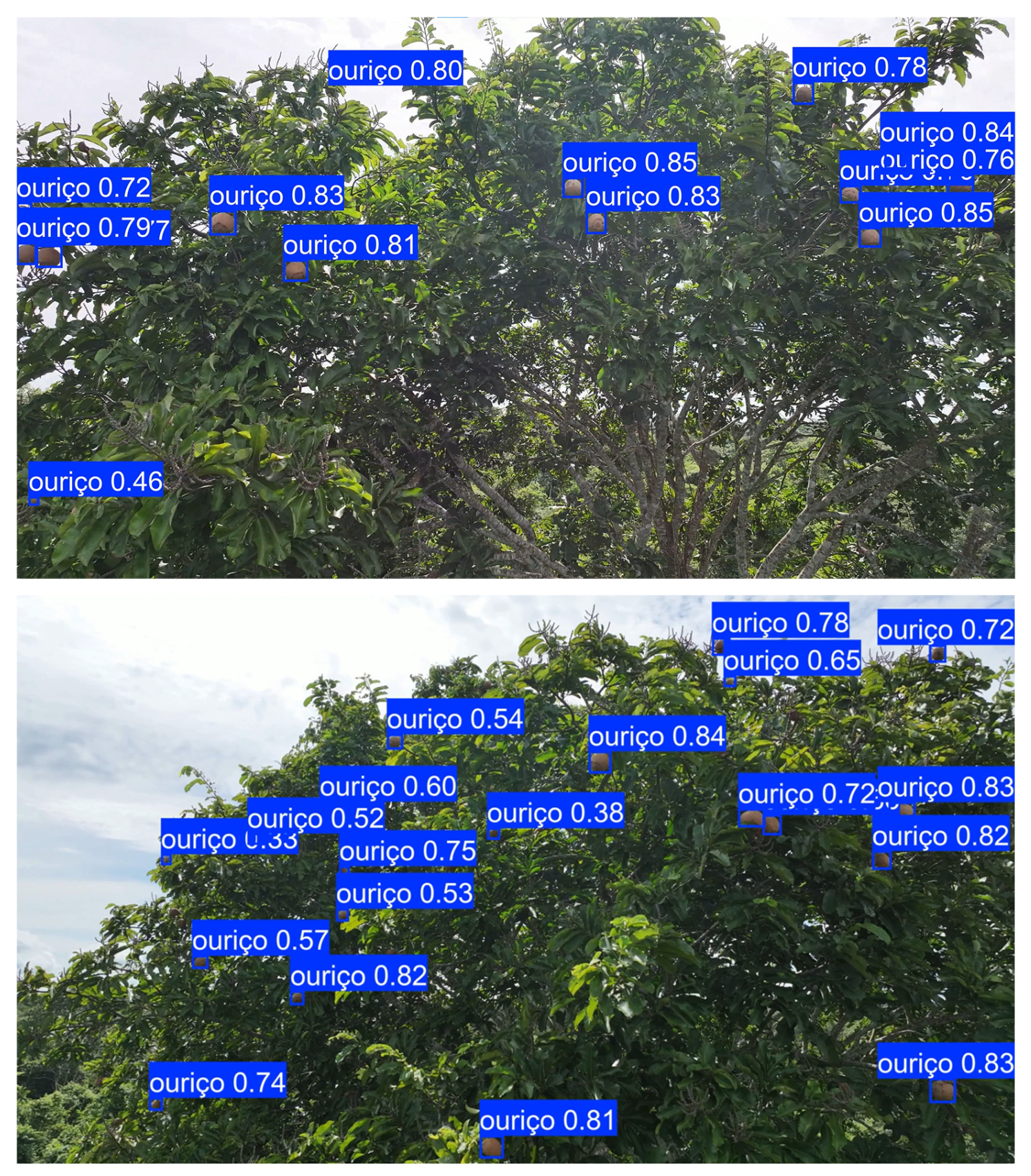

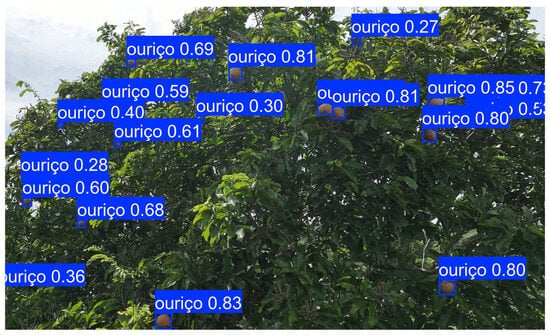

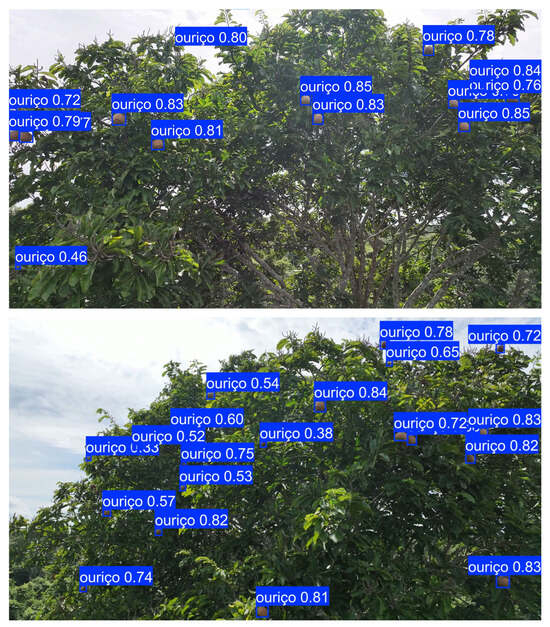

3.2. Visualization

The YOLOv8 model successfully detected Brazil nut fruits in UAV-based images, as illustrated in Figure 9. Visual inspection confirmed that most fruits were correctly identified, although some misclassifications occurred between the “burr” class and background elements. Figure 9 also shows that most occluded burrs were correctly detected even when partially covered by leaves of overlapping with other burrs, demonstrating the model’s ability to handle challenging conditions. Nevertheless, some under-detection cases are also observed.

Figure 9.

Examples of model predictions on field images showing detected Brazil nut burrs (“ouriço” in Portuguese) and the detection confidence.

4. Discussion

Seasonal changes in leaf coloration and branch structure in Brazil nut trees can interfere with detection accuracy. Data were collected during the dry season to minimize weather-related constraints, although seasonal variability remains an important consideration for future dataset expansion. Similar challenges have been reported in studies of forest species identification using canopy images. Veras et al. [40] observed that convolutional networks applied to multi-temporal UAV imagery still produced misclassification during the dry season, despite achieving a mean accuracy of 99%. These seasonal patterns suggest that incorporating images from different seasons can improve species identification and detection performance by increasing dataset variability. Gao and Zhang [41] also demonstrated that customized datasets with more background variability and lighting could help reduce confusion between target objects and non-fruit elements.

Partial occlusion is another challenge in species with clustered fruits, as it affects segmentation methods that may merge continuous husks. This makes object detection more suitable for yield estimation. This was demonstrated in chestnut trees (Castanea sativa Mill.); Carneiro et al. [42] compared segmentation networks (U-Net, LinkNet, PSPNet) with YOLOv8m on UAV RGB images for chestnut burr detection and concluded that object detection provided more operationally reliable results. Adão et al. [43] used Xception (IoU ≈ 0.54) to segment chestnut burr areas in terrestrial images. Similar conclusions were drawn by Arakawa et al. [44], who used YOLOv4 on UAV imagery and achieved an IoU of 84.27% and an RMSE of 6.3 fruits per tree. Comba et al. [45] reported an accuracy of 92.3% using U-Net on multispectral UAV images. These results are in line with the ones obtained in complex canopies such as Brazil nut trees, where variations in lighting, flight height and canopy occlusion explain confidence losses. This validates the prioritization of object detection for counting while maintaining segmentation as a complementary approach (e.g., for point cloud projection).

The performance obtained in this study was superior to that reported by Li et al. [46], who achieved a mAP of 80.4% for citrus fruits using an improved YOLOv7. This highlights the effectiveness of YOLOv8 in high-visibility scenarios and suggests that the model has a strong potential for detecting Brazil nut fruits under similar conditions. However, challenges remain when fruits are partially occluded. Yang et al. [47] pointed out that algorithmic adjustments are necessary to address occlusion in apple detection, which aligns with the difficulties observed in this study. Zheng et al. [27] showed that a proposed YOLO model achieved good recall and precision, whereas YOLOv4-Tiny reached high recall but low precision. In citrus detection, Ang et al. [39] reported that experiments with YOLOv8 achieved 91.47% precision, only 2.14% lower than the improved version. The recall values obtained in this study are slightly higher than those reported by Ang et al. [39], who achieved 89.29%. These results indicate that performance improvements do not always require major architectural changes and meaningful gains can be obtained through parameter adjustments. Another important factor in forest environments is crown leaf density, which can cause confusion in object identification. Zheng et al. [48] highlighted that dense foliage increases misclassification risk in jujube detection, a condition similar to Brazil nut canopies, where fruit visibility varies among individuals and canopy conditions.

The results confirm that UAV imagery combined with YOLOv8 is a practical approach for estimating Brazil nut yield under natural forest conditions. However, improvements are needed to increase confidence in predictions and address occlusion issues. While the model achieved high precision and recall (Table 2), the impact of errors differs in practice. False negatives (missed detections) can lead to underestimation of fruit production, affecting pricing strategies, harvest planning, and potentially reducing income for extractivists. On the other hand, false positives (incorrect detections) have the potential to inflate estimates, which could result in market oversupply and price reductions. Understanding these trade-offs is essential for applying detection results to real-world harvest planning. Integrating UAV-based detection into yield estimation can help anticipate production variability and negotiate fair prices, reducing reliance on manual or inexistent surveys or subjective estimates. This approach supports more transparent and efficient market strategies for extractivist communities.

Beyond fruit detection, UAVs offer multiple opportunities for Brazil nut tree monitoring and management. Photogrammetric techniques and LiDAR-based approaches can generate three-dimensional models of tree canopies [49,50], enabling the extraction of structural metrics such as canopy height, crown diameter, and volume [51]. These parameters are useful for assessing tree growth, biomass accumulation, and long-term forest dynamics [52]. Multi-temporal UAV surveys can track changes in canopy architecture, supporting studies on phenology and productivity trends [53,54]. The integration of multispectral imagery provides additional inputs into tree health by estimating biophysical indicators such as leaf area index [55], chlorophyll content, and stress-related indices. These metrics can complement geometric data to evaluate vigor and detect early signs of disease or nutrient deficiency [54]. When combined with yield records, these datasets can be used to develop predictive models linking canopy structure and physiological traits to fruit production. Such models would enable more accurate yield forecasting and resource planning.

Future research should explore the creation of UAV-based datasets that include geometric and spectral features, coupled with ground-truth yield measurements [56]. These datasets could support machine learning frameworks for multi-variable prediction for non-timber products [49]. Additionally, integrating LiDAR or photogrammetric point clouds with multispectral data may improve biomass estimation and carbon stock assessments, contributing to climate monitoring and sustainable forest management [57,58]. Beyond dataset expansion, future work should also include comparative studies using different object detection architectures. While this study focused on evaluate the feasibility of applying YOLOv8 to UAV imagery for Brazil nut detection, benchmarking multiple models would provide a deeper understanding of their strengths and limitations under natural forest conditions, which could assist in identifying the most suitable architectures for improving detection accuracy and operational efficiency in complex environments.

5. Conclusions

This study evaluated the use of UAV imagery combined with the YOLOv8 object detection model to monitor Brazil nut fruit production in a native forest fragment in eastern Acre, Brazil. The approach achieved satisfactory performance for precision, recall, and mAP, despite challenges such as canopy complexity and partial occlusion.

The results indicate that UAV-based detection can reduce the need for labor-intensive surveys and provide more accurate yield estimates, supporting better pricing strategies for extractivist communities. Although the model performed well under visible conditions, improvements are needed to address low-confidence predictions and occlusion. Future work should focus on expanding datasets to include seasonal variability, integrating multispectral or LiDAR data, and exploring hybrid detection-segmentation approaches to improve accuracy in dense forest environments.

Therefore, the integration of UAVs and AI-based detection represents a solution for precision management of non-timber forest products, contributing to sustainable forest use and socioeconomic development in the Amazon for communities that rely on Brazil nuts as a source of livelihood.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.P.d.C. and Q.S.B.; methodology, H.P.d.C. and Q.S.B.; software, H.P.d.C.; validation, H.P.d.C., Q.S.B. and L.P.; formal analysis, L.F.; investigation, H.P.d.C., Q.S.B., E.J.L.F., L.F.d.S., B.T.d.A. and E.G.C.; resources, E.J.L.F. and L.P.; data curation, N.M.M.R., L.F.d.S., B.T.d.A. and E.G.C.; writing—original draft preparation, H.P.d.C. and L.F.; writing—review and editing, L.P., E.J.L.F., Q.S.B. and N.M.M.R.; visualization, L.F. and H.P.d.C.; supervision, L.P.; project administration, H.P.d.C. and L.P.; funding acquisition, E.J.L.F. and L.P. † The contribution of R.d.M.P. was completed prior to his passing and is included in memoriam. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request. The dataset used in this study is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.18393379 (accessed on 23 January 2026).

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted as part of an undergraduate research project, with support from the State Funding Agency of Acre (FAPAC) and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq). The authors would like to express their gratitude to Romário de Mesquita Pinheiro for his involvement in the project, as well as for his assistance and participation in the laboratory activities. We also thank all individuals who contributed to this study. L.F. and L.P. would like to acknowledge the support through National Funds by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT), under the projects UID/04033/2025: Centre for the Research and Technology of Agro-Environmental and Biological Sciences (https://doi.org/10.54499/UID/04033/2025 (accessed on 23 January 2026)) and LA/P/0126/2020 (https://doi.org/10.54499/LA/P/0126/2020 (accessed on 23 January 2026)). During the preparation of this work AI tools was used to improve the clarity and polish the language of certain sections in the manuscript. After using these tools, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- da Costa, K.C.P.; de Carvalho Gonçalves, J.F.; Gonçalves, A.L.; da Rocha Nina Junior, A.; Jaquetti, R.K.; de Souza, V.F.; de Carvalho, J.C.; Fernandes, A.V.; Rodrigues, J.K.; de Oliveira Nascimento, G.; et al. Advances in Brazil Nut Tree Ecophysiology: Linking Abiotic Factors to Tree Growth and Fruit Production. Curr. For. Rep. 2022, 8, 90–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, R.d.M.; Ferreira, E.J.L.; Barros, Q.d.S.; Gadotti, G.I.; Alechandre, A.; Lima, J.M.T. Physical Characterization and Dimensional Analysis of Brazil Nut Seeds: Implications for Germination, Post-Harvest and Optimization of Industrial Processing. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2024, 67, e24240111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadt, L.H.O.; Kainer, K.A.; Staudhammer, C.L.; Serrano, R.O.P. Sustainable Forest Use in Brazilian Extractive Reserves: Natural Regeneration of Brazil Nut in Exploited Populations. Biol. Conserv. 2008, 141, 332–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariosa, P.H.; Pereira, H.d.S.; Kluczkovski, A.M.; Vinhote, M.L.A. Agroindustrial Cooperatives in the Brazilian Nuts Value Chain: A New Extractive Paradigm in the Amazon. Rev. Econ. Sociol. Rural 2024, 62, e277617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, T.C.V.; Silva, K.E. da Valoração do trabalho agroextrativista de produtos da sociobiodiversidade na Amazônia: Atividade de coleta da castanha-do-Brasil na reserva extrativista Chico Mendes, Acre, Brasil. Acta Sci. Hum. Soc. Sci. 2023, 45, e69247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, L.S.; Santana, C.S.; de Pinho, C.L.C.; Coutinho, L.S.; Plácido, G.R.; Resende, O.; Hendges, M.V.; Oliveira, D.E.C. De O Contexto Da Cadeia Produtiva Da Castanha-Do-Brasil No Período de 2017 a 2021. Obs. Econ. Latinoam. 2023, 21, 9218–9230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE—Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. PEVS—Produção de Extração Vegetal e Da Silvicultura. 2023. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/economicas/agricultura-e-pecuaria/9105-producao-da-extracao-vegetal-e-da-silvicultura.html?=&t=destaques (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Scoles, R.; Gribel, R. The Regeneration of Brazil Nut Trees in Relation to Nut Harvest Intensity in the Trombetas River Valley of Northern Amazonia, Brazil. For. Ecol. Manag. 2012, 265, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, M.; Guariguata, M.R.; Chiriboga-Arroyo, F.; Quaedvlieg, J.; Vargas Quispe, F.M.; Arroyo Quispe, E.; García Roca, M.R.; Corvera-Gomringer, R.; Kettle, C.J. Forest Degradation and Inter-Annual Tree Level Brazil Nut Production in the Peruvian Amazon. Front. For. Glob. Change 2021, 3, 525533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjos, L.J.S.; Gonçalves, G.S.R.; Dutra, V.A.B.; Rosa, A.G.; Santos, L.B.; Barros, M.N.R.; de Souza, E.B.; Toledo, P.M. de Brazil Nut Journey under Future Climate Change in Amazon. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0312308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertwell, T.D.; Kainer, K.A.; Cropper, W.P., Jr.; Staudhammer, C.L.; de Oliveira Wadt, L.H. Are Brazil Nut Populations Threatened by Fruit Harvest? Biotropica 2018, 50, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogili, U.R.; Deepak, B.B.V.L. Review on Application of Drone Systems in Precision Agriculture. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2018, 133, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, W.H.; Steppe, K. Perspectives for Remote Sensing with Unmanned Aerial Vehicles in Precision Agriculture. Trends Plant Sci. 2019, 24, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sa, I.; Ge, Z.; Dayoub, F.; Upcroft, B.; Perez, T.; McCool, C. DeepFruits: A Fruit Detection System Using Deep Neural Networks. Sensors 2016, 16, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Sánchez, J.; Peña, J.M.; de Castro, A.I.; López-Granados, F. Multi-Temporal Mapping of the Vegetation Fraction in Early-Season Wheat Fields Using Images from UAV. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2014, 103, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pádua, L.; Vanko, J.; Hruška, J.; Adão, T.; Sousa, J.J.; Peres, E.; Morais, R. UAS, Sensors, and Data Processing in Agroforestry: A Review towards Practical Applications. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2017, 38, 2349–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, D.R.A.; Broadbent, E.N.; Zambrano, A.M.A.; Wilkinson, B.E.; Ferreira, M.E.; Chazdon, R.; Meli, P.; Gorgens, E.B.; Silva, C.A.; Stark, S.C.; et al. Monitoring the Structure of Forest Restoration Plantations with a Drone-Lidar System. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2019, 79, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, F.d.O.; Araki, H. Detecção de Palmeiras Em Imagens Aéreas: Análise Multiescala e Avaliação Da Sanidade. Contrib. A LAS Cienc. Soc. 2024, 17, e5453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.P.; Lotte, R.G.; D’Elia, F.V.; Stamatopoulos, C.; Kim, D.-H.; Benjamin, A.R. Accurate Mapping of Brazil Nut Trees (Bertholletia excelsa) in Amazonian Forests Using WorldView-3 Satellite Images and Convolutional Neural Networks. Ecol. Inform. 2021, 63, 101302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiefer, F.; Kattenborn, T.; Frick, A.; Frey, J.; Schall, P.; Koch, B.; Schmidtlein, S. Mapping Forest Tree Species in High Resolution UAV-Based RGB-Imagery by Means of Convolutional Neural Networks. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 170, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, Y.; Dennis, R.; Elgazzar, K. Yield Estimation and Visualization Solution for Precision Agriculture. Sensors 2021, 21, 6657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Lan, Y. Precision Detection of Dense Litchi Fruit in UAV Images Based on Improved YOLOv5 Model. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anushi; Jain, S.; Bhujel, S.; Shrivastava, U.; Rishabh; Mohapatra, A.; Rimpika; Mishra, G. Advancements in Drone Technology for Fruit Crop Management: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Environ. Clim. Change 2023, 13, 4367–4378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, C. De o Clima do Estado do Acre; IMAC: Rio Branco, Brazil, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Peter, N.R.; Raja, N.R.; Rengarajan, J.; Radhakrishnan Pillai, A.; Kondusamy, A.; Saravanan, A.K.; Changaramkumarath Paran, B.; Kumar Lal, K. A Comprehensive Study on Ecological Insights of Ulva lactuca Seaweed Bloom in a Lagoon along the Southeast Coast of India. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2024, 248, 106964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Tang, R.; Mu, J.; Niu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Chen, Z. A Lightweight Grape Detection Model in Natural Environments Based on an Enhanced YOLOv8 Framework. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1407839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Hu, Y.; Yang, H.; Qiao, Y.; Huang, Y. A Real-Time Winter Jujubes Detection Approach Based on Improved YOLOv4. In 2nd International Conference on Signal Image Processing and Communication (ICSIPC 2022); SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2022; Volume 12246, pp. 506–511. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. In 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Bradski, G. The Opencv Library. Dr. Dobb’s J. Softw. Tools Prof. Program. 2000, 25, 120–123. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, C.R.; Millman, K.J.; van der Walt, S.J.; Gommers, R.; Virtanen, P.; Cournapeau, D.; Wieser, E.; Taylor, J.; Berg, S.; Smith, N.J.; et al. Array Programming with NumPy. Nature 2020, 585, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, W. Data Structures for Statistical Computing in Python. In Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference, Austin, Texas, 28 June–3 July 2010; van der Walt, S., Millman, J., Eds.; SciPy: Austin, TX, USA, 2010; pp. 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.D. Matplotlib: A 2D Graphics Environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2007, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waskom, M.L. Seaborn: Statistical Data Visualization. J. Open Source Softw. 2021, 6, 3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-Learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, M.; Jing, J.; Dou, S.; Du, J.; Wang, R.; Yan, J.; Song, Y.; Mei, Z. Deriving Early Citrus Fruit Yield Estimation by Combining Multiple Growing Period Data and Improved YOLOv8 Modeling. Sensors 2025, 25, 4718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Yuan, D.; Zhao, M.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, L.; Fan, Y.; Liang, G.; Zhou, Y. Camellia Oleifera Tree Detection and Counting Based on UAV RGB Image and YOLOv8. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Sun, X.; Yang, K.; He, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, B.; Wang, F.; Liu, H. A Lightweight Wheat Ear Counting Model in UAV Images Based on Improved YOLOv8. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1536017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Hou, Y.; Cui, T.; Li, H.; Shangguan, F.; Cao, L. YOLOv8-CML: A Lightweight Target Detection Method for Color-Changing Melon Ripening in Intelligent Agriculture. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ang, G.; Zhiwei, T.; Wei, M.; Yuepeng, S.; Longlong, R.; Yuliang, F.; Jianping, Q.; Lijia, X. Fruits Hidden by Green: An Improved YOLOV8n for Detection of Young Citrus in Lush Citrus Trees. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1375118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veras, H.F.P.; Ferreira, M.P.; da Cunha Neto, E.M.; Figueiredo, E.O.; Corte, A.P.D.; Sanquetta, C.R. Fusing Multi-Season UAS Images with Convolutional Neural Networks to Map Tree Species in Amazonian Forests. Ecol. Inform. 2022, 71, 101815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Zhang, Y. Detection of Fruit Using YOLOv8-Based Single Stage Detectors. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. (IJACSA) 2023, 14, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, G.A.; Santos, J.; Sousa, J.J.; Cunha, A.; Pádua, L. Chestnut Burr Segmentation for Yield Estimation Using UAV-Based Imagery and Deep Learning. Drones 2024, 8, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adão, T.; Pádua, L.; Pinho, T.M.; Hruška, J.; Sousa, A.; Sousa, J.J.; Morais, R.; Peres, E. Multi-purpose chestnut clusters detection using deep learning: A preliminary approach. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2019, XLII-3-W8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arakawa, T.; Tanaka, T.S.T.; Kamio, S. Detection of On-Tree Chestnut Fruits Using Deep Learning and RGB Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Imagery for Estimation of Yield and Fruit Load. Agron. J. 2024, 116, 973–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comba, L.; Biglia, A.; Sopegno, A.; Grella, M.; Dicembrini, E.; Ricauda Aimonino, D.; Gay, P. Convolutional Neural Network Based Detection of Chestnut Burrs in UAV Aerial Imagery. In AIIA 2022: Biosystems Engineering Towards the Green Deal; Ferro, V., Giordano, G., Orlando, S., Vallone, M., Cascone, G., Porto, S.M.C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 501–508. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhu, X.; Tian, X.; Jin, G. Research on Identification and Detection Fruits of Citrus Canopy Based on Yolovs. 2023. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4498586 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Yang, H.; Wu, J.; Liang, A.; Wang, S.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, N.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Qiu, J. Fruit Recognition, Task Plan, and Control for Apple Harvesting Robots. Rev. Bras. Eng. Agrícola Ambient. 2024, 28, e277280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Hu, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Hu, X.; Huang, Y. Real-Time Detection of Winter Jujubes Based on Improved YOLOX-Nano Network. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corte, A.P.D.; Souza, D.V.; Rex, F.E.; Sanquetta, C.R.; Mohan, M.; Silva, C.A.; Zambrano, A.M.A.; Prata, G.; Alves de Almeida, D.R.; Trautenmüller, J.W.; et al. Forest Inventory with High-Density UAV-Lidar: Machine Learning Approaches for Predicting Individual Tree Attributes. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 179, 105815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, Q.S.; d’ Oliveira, M.V.N.; da Silva, E.F.; Görgens, E.B.; de Mendonça, A.R.; da Silva, G.F.; Reis, C.R.; Gomes, L.F.; de Carvalho, A.L.; de Oliveira, E.K.B.; et al. Indicators for Monitoring Reduced Impact Logging in the Brazilian Amazon Derived from Airborne Laser Scanning Technology. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 82, 102654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veras, H.F.P.; Neto, E.M.d.C.; Brasil, I.D.S.; Madi, J.P.S.; Araujo, E.C.G.; Camaño, J.D.Z.; Figueiredo, E.O.; Papa, D.d.A.; Ferreira, M.P.; Corte, A.P.D.; et al. Estimating tree volume based on crown mapping by UAV pictures in the Amazon Forest. Sci. Electron. Arch. 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berra, E.F.; Gaulton, R.; Barr, S. Assessing Spring Phenology of a Temperate Woodland: A Multiscale Comparison of Ground, Unmanned Aerial Vehicle and Landsat Satellite Observations. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 223, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambertini, A.; Mandanici, E.; Tini, M.A.; Vittuari, L. Technical Challenges for Multi-Temporal and Multi-Sensor Image Processing Surveyed by UAV for Mapping and Monitoring in Precision Agriculture. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pádua, L.; Marques, P.; Martins, L.; Sousa, A.; Peres, E.; Sousa, J.J. Monitoring of Chestnut Trees Using Machine Learning Techniques Applied to UAV-Based Multispectral Data. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pádua, L.; Chiroque-Solano, P.M.; Marques, P.; Sousa, J.J.; Peres, E. Mapping the Leaf Area Index of Castanea Sativa Miller Using UAV-Based Multispectral and Geometrical Data. Drones 2022, 6, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierdicca, R.; Nepi, L.; Mancini, A.; Malinverni, E.S.; Balestra, M. Uav4tree: Deep learning-based system for automatic classification of tree species using RGB optical images obtained by an unmanned aerial vehicle. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2023, X-1-W1-2023, 1089–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messinger, M.; Asner, G.P.; Silman, M. Rapid Assessments of Amazon Forest Structure and Biomass Using Small Unmanned Aerial Systems. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaglio Laurin, G.; Chen, Q.; Lindsell, J.A.; Coomes, D.A.; Frate, F.D.; Guerriero, L.; Pirotti, F.; Valentini, R. Above Ground Biomass Estimation in an African Tropical Forest with Lidar and Hyperspectral Data. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2014, 89, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.