Air and Spray Pattern Characterization of Multi-Fan Autonomous Unmanned Ground Vehicle Sprayer Adapted for Modern Orchard Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

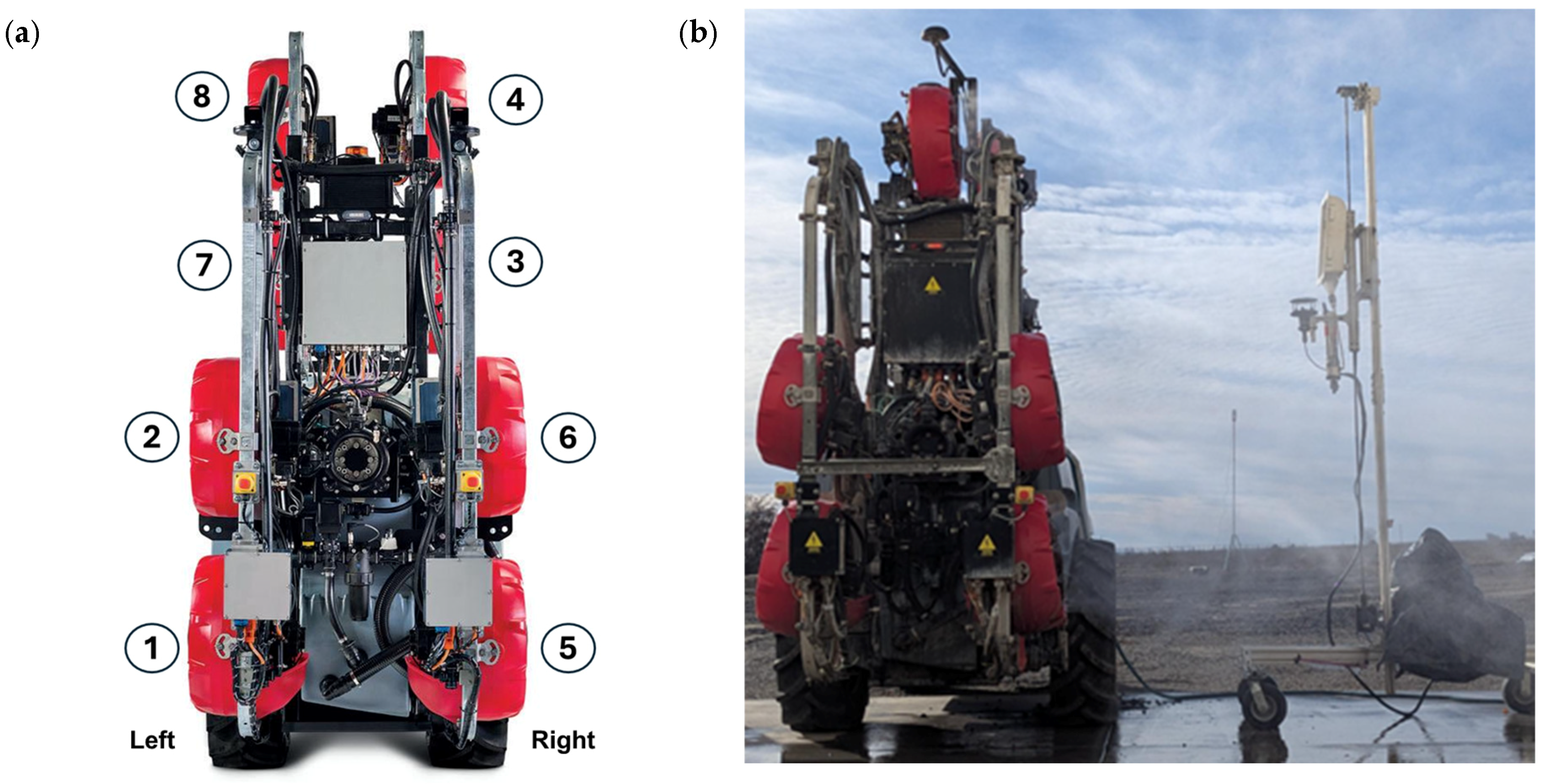

2.1. Sprayer Unit

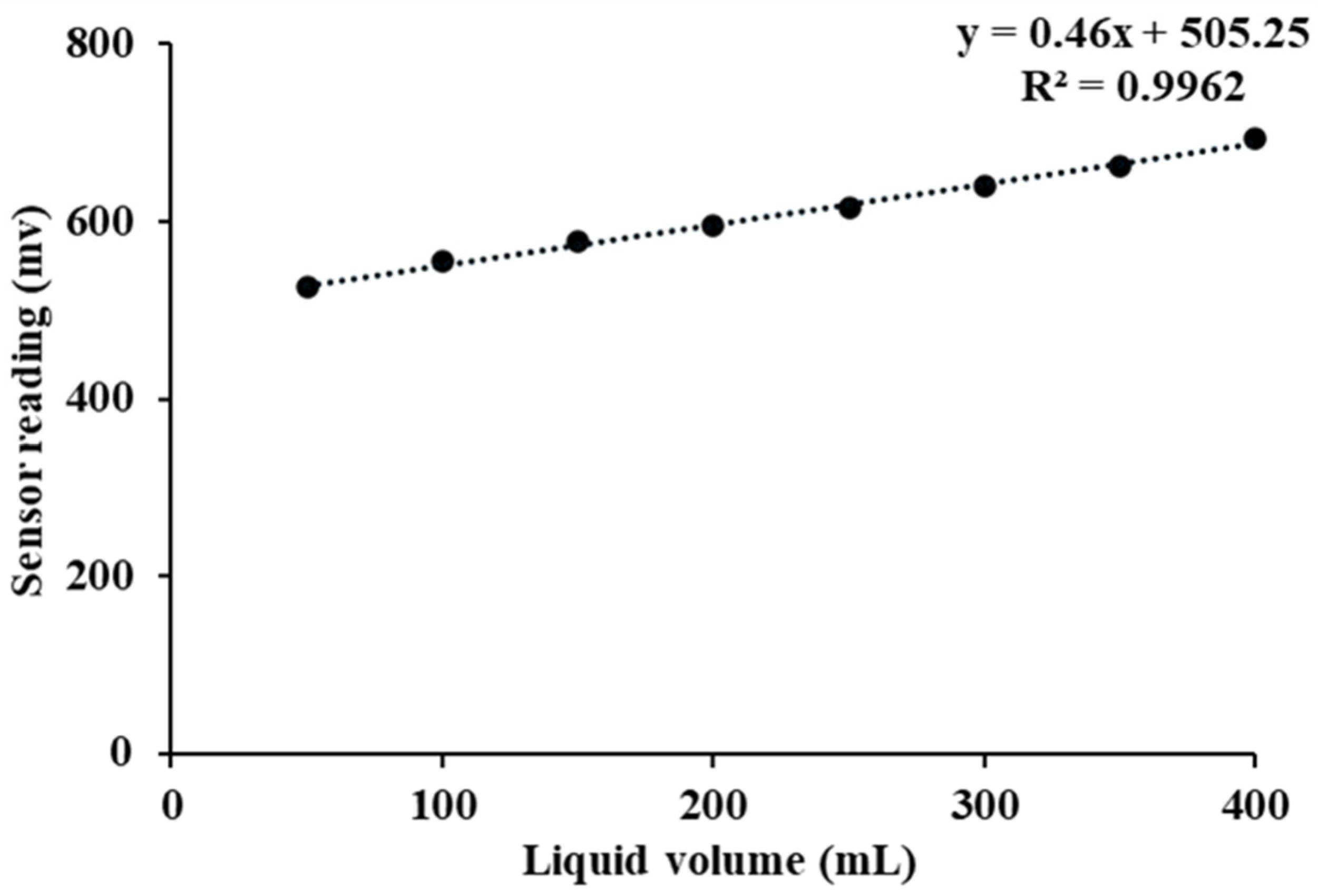

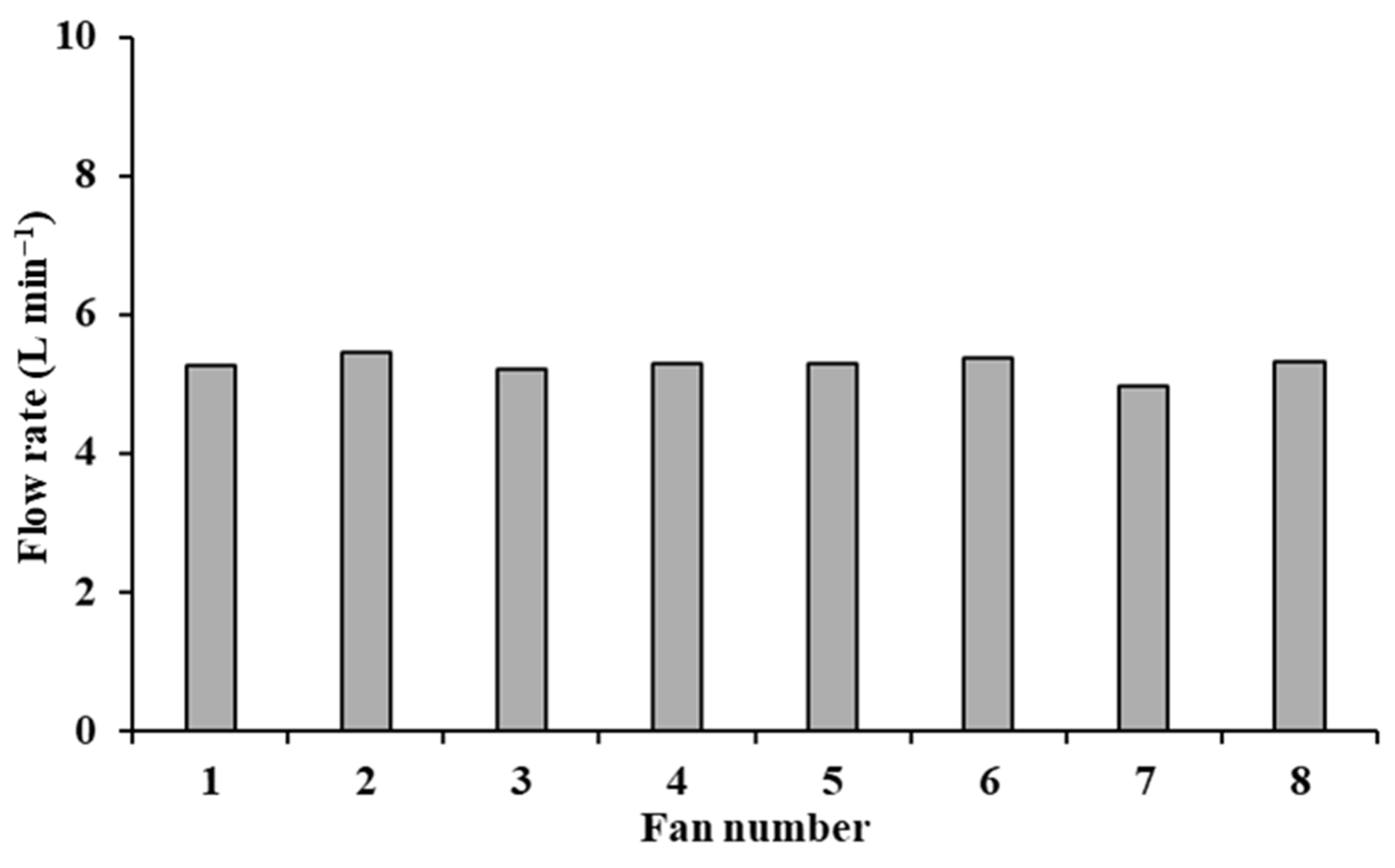

2.2. Flow Rate Measurements

2.3. Sprayer Air Velocity and Spray Delivery Patterns Assessment

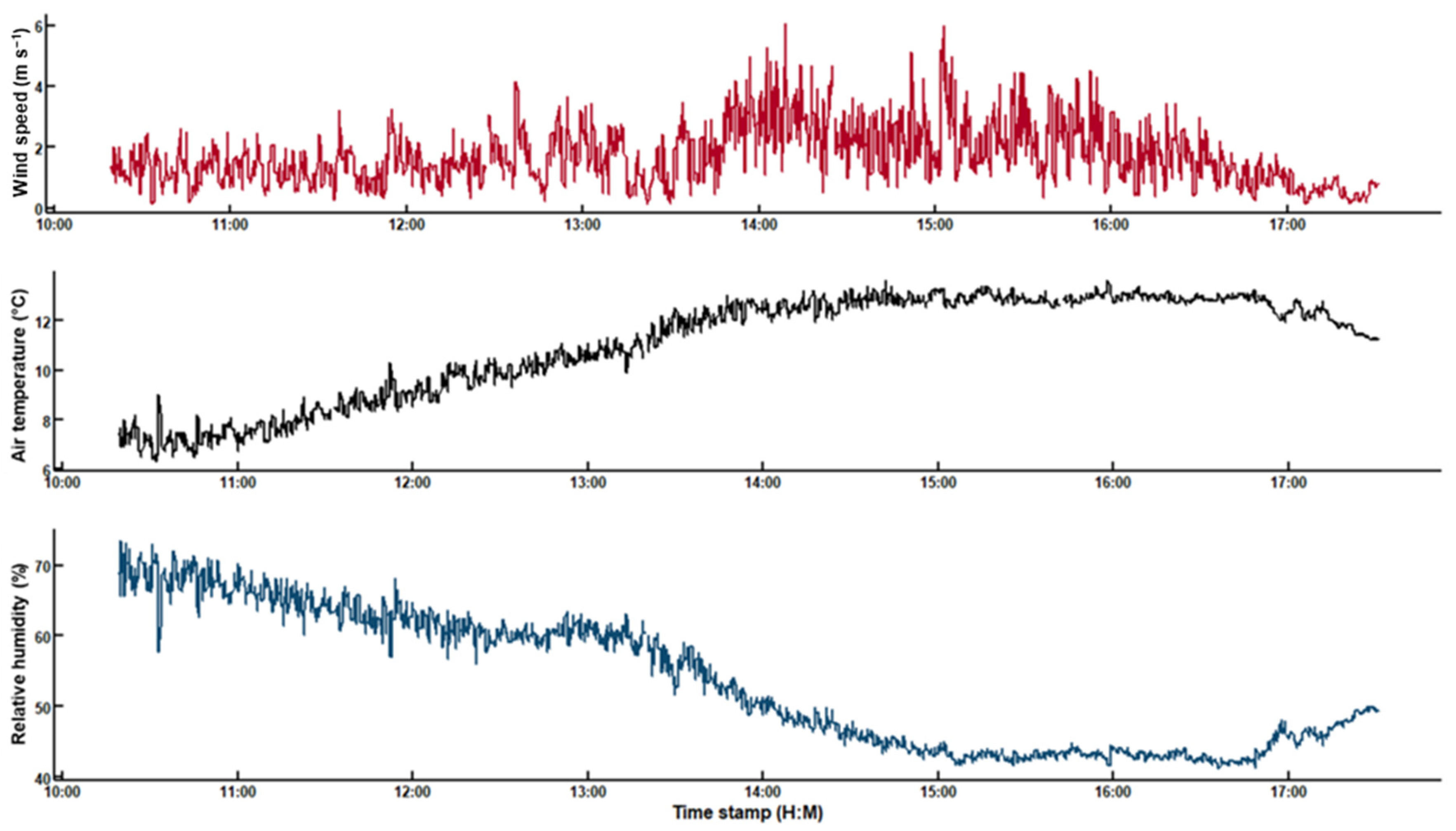

2.4. Weather Parameters

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Nozzle Flowrate Measurements

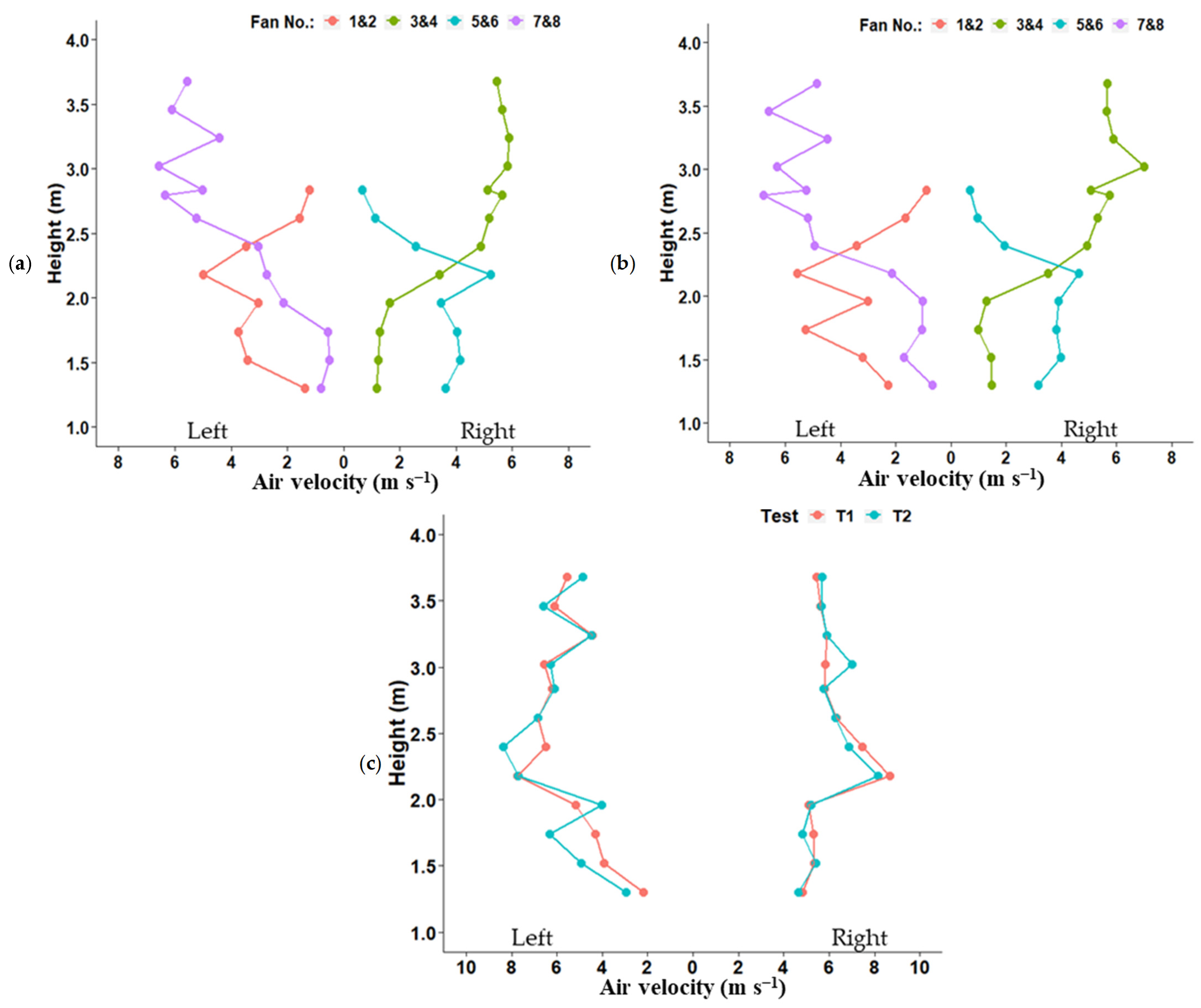

3.2. Air Velocity Patterns

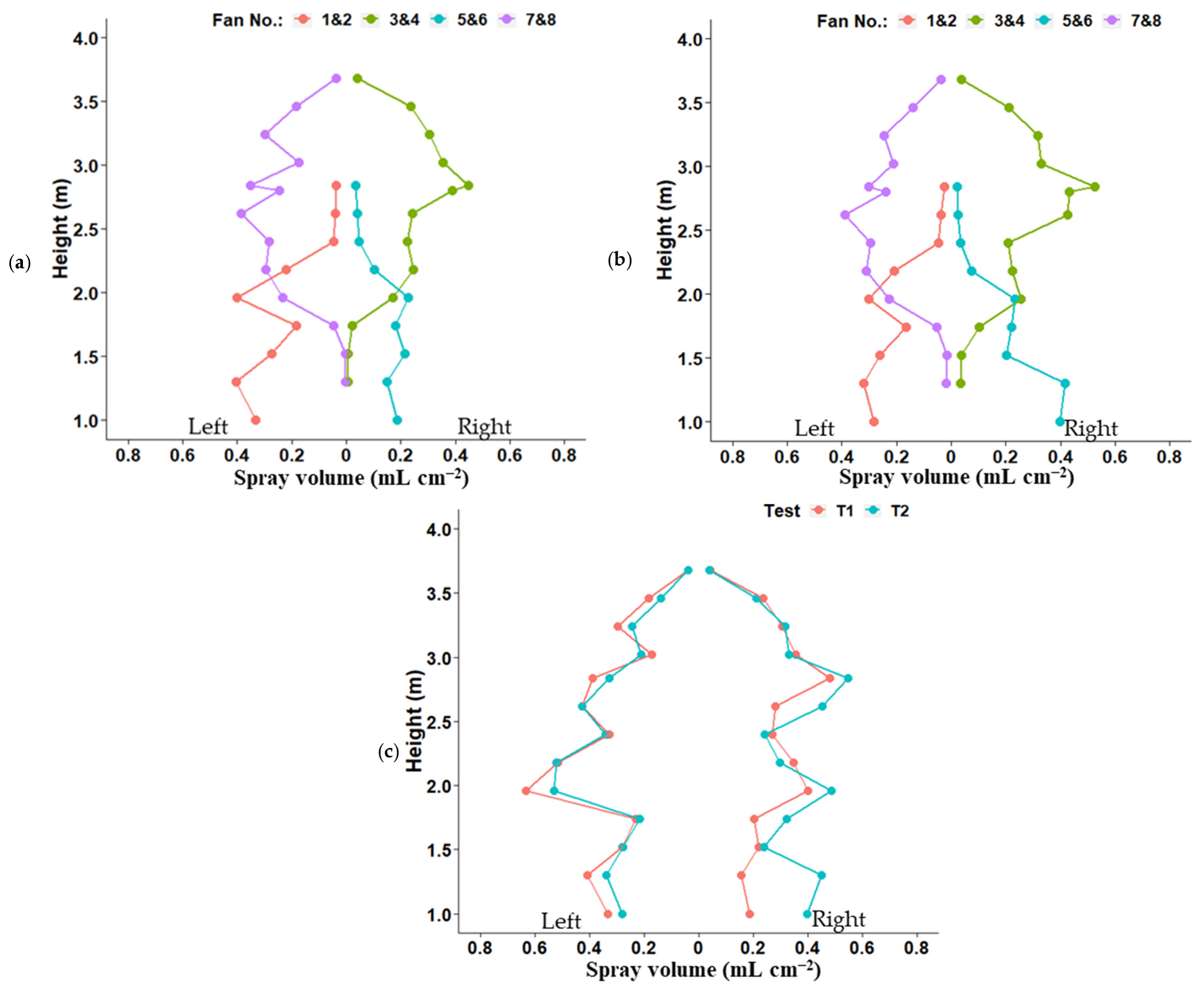

3.3. Spray Delivery Patterns

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- USDA-NAAS. Apple Utilized Production in Oregon and Washington. Press Release-National Agricultural Statistics Service. 5 May 2025. Available online: https://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/Idaho/Publications/Census_Press_Releases/2025/FRUIT.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Rathnayake, A.P.; Chandel, A.K.; Schrader, M.J.; Hoheisel, G.A.; Khot, L.R. Spray Patterns and Perceptive Canopy Interaction Assessment of Commercial Airblast Sprayers Used in Pacific Northwest Perennial Specialty Crop Production. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 184, 106097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, A. The History and Application of the High-Density Orchard System. Master’s Thesis, California State University, Chico, CA, USA, May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, L.; Mahdi, S.S. Variable Rate Technology and Variable Rate Application. In Satellite Farming: An Information and Technology Based Agriculture; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Saleem, S.R.; Zaman, Q.U.; Schumann, A.W.; Naqvi, S.M.Z.A. Variable Rate Technologies: Development, Adaptation, and Opportunities in Agriculture. In Precision Agriculture; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 103–122. [Google Scholar]

- Bhalekar, D.G.; Parray, R.A.; Mani, I.; Kushwaha, H.; Khura, T.K.; Sarkar, S.K.; Lande, S.D.; Verma, M.K. Ultrasonic Sensor-Based Automatic Control Volume Sprayer for Pesticides and Growth Regulators Application in Vineyards. Smart Agric. Technol. 2023, 4, 100232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taseer, A.; Han, X. Advancements in Variable Rate Spraying for Precise Spray Requirements in Precision Agriculture Using Unmanned Aerial Spraying Systems: A Review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 219, 108841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paunović, G.; Veljkovic, B.; Ilić, R.; Bošković-Rakočević, L. Economic Analysis of Pear Orchard Establishment. Acta Agric. Serbica 2018, 23, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roettele, M.; Laabs, V.; Rutherford, S. The Importance of Sprayer Inspections in the EU from a Chemical Industry Perspective. SPISE 2018, 7, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Sahni, R.K.; Ranjan, R.; Hoheisel, G.A.; Khot, L.R.; Beers, E.H.; Grieshop, M.J. Pneumatic Spray Delivery-Based Solid Set Canopy Delivery System for Oblique Banded Leaf Roller and Codling Moth Control in a High-Density Modern Apple Orchard. Pest Manag. Sci. 2022, 78, 4793–4801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalekar, D.G.; Sahni, R.K.; Schrader, M.J.; Khot, L.R. Pneumatic Spray Delivery-Based Fixed Spray System Configuration Optimization for Efficient Agrochemical Application in Modern Vineyards. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 4044–4054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrader, M.J.; Bhalekar, D.G.; Sahni, R.K.; Khot, L.R. Unmanned Aerial Sprayers: Evaluating Platform Configurations and Flight Patterns for Effective Chemical Applications in Modern Vineyards. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 11, 101033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, C.; Xue, C.; Zhang, L.; Song, C.; Kaousar, R.; Wang, G.; Lan, Y. Effects of Different Spray Parameters of Plant Protection UAV on the Deposition Characteristics of Droplets in Apple Trees. Crop Prot. 2024, 184, 106835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, Y.; He, X.; Song, J.; Zeng, A.; Wu, Z.; Tian, L. Assessment of Spray Deposition and Losses in the Apple Orchard from Agricultural Unmanned Aerial Vehicle in China. In Proceedings of the 2018 ASABE Annual International Meeting, Detroit, MI, USA, 29 July–1 August 2018; ASABE: St. Joseph, MI, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Han, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wongsuk, S.; Li, Y.; Wu, X.; He, X. Spray Performance Evaluation of a Six-Rotor Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Sprayer for Pesticide Application Using an Orchard Operation Mode in Apple Orchards. Pest Manag. Sci. 2022, 78, 2449–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Dolma, S.; Fatima, N. An Autonomous Unmanned Ground Vehicle: A Technology-Driven Approach for Spraying Agro-Chemicals in Agricultural Crops. Environ. Ecol. 2024, 42, 1069–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Xue, X.; Salcedo, R.; Zhang, Z.; Gil, E.; Sun, Y.; Li, Q.; Shen, J.; He, Q.; Dou, Q.; et al. Key Technologies for an Orchard Variable-Rate Sprayer: Current Status and Future Prospects. Agronomy 2022, 13, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Song, J.; Qi, P.; Yuan, C.; Wu, H.; Zhang, L.; Liu, W.; Liu, Y.; He, X. Design and Development of Orchard Autonomous Navigation Spray System. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 960686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, B.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Luo, X.; Zhang, G.; Huang, H.; Wu, X.; Bao, K.; Peng, M. Design of an Automatic Navigation and Operation System for a Crawler-Based Orchard Sprayer Using GNSS Positioning. Agronomy 2024, 14, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochan, K.; Khan, A.; Elsayed, I.; Suthar, B.; Seneviratne, L.; Hussain, I. Advancements in Precision Spraying of Agricultural Robots: A Comprehensive Review. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 129447–129483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoheisel, G.A.; Bhalekar, D.G.; Gorthi, S.; Khot, L.R. Automated Single-Row Multi-Fan Sprayer Optimization for Efficient Spray Application in Modern Apple Orchards. In Precision Agriculture ′25; Wageningen Academic: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2025; p. 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çomaklı, M.; Sayıncı, B. A Novel Image-Based Method for Measuring Spray Pattern Distribution in a Mechanical Patternator. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 5682-1:2017; Equipment for Crop Protection—Spraying Equipment Part 1: Test Methods for Sprayer Nozzles. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/60053.html (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Bahlol, H.Y.; Chandel, A.K.; Hoheisel, G.A.; Khot, L.R. Smart Spray Analytical System for Orchard Sprayer Calibration: A Proof-of-Concept and Preliminary Results. Trans. ASABE 2020, 63, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WindSonic1 2-D Sonic Wind Sensor with RS-232 Output; Product Manual-Campbell Scientific Inc.: Logan, UT, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.campbellsci.com/windsonic1 (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- ISO 24253-1:2015; Crop Protection Equipment—Spray Deposition Test for Field Crop Part 1: Measurement in a Horizontal Plane. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/60051.html (accessed on 19 December 2025).

- Farooq, M.; Landers, A.J. Interactive Effects of Air, Liquid and Canopies on Spray Patterns of Axial-Flow Sprayers. In Proceedings of the 2004 ASAE Annual Meeting, St. Joseph, MI, USA, 1–4 August 2004; ASABE: St. Joseph, MI, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gil Moya, E.; Landers, A.; Gallart González-Palacio, M.; Llorens Calveras, J. Development of Two Portable Patternators to Improve Drift Control and Operator Training in the Operation of Vineyard Sprayers. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2013, 11, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Bahlol, H.Y.; Chandel, A.K.; Hoheisel, G.A.; Khot, L.R. The Smart Spray Analytical System: Developing Understanding of Output Air-Assist and Spray Patterns from Orchard Sprayers. Crop Prot. 2020, 127, 104977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felsot, A.S.; Unsworth, J.B.; Linders, J.B.; Roberts, G.; Rautman, D.; Harris, C.; Carazo, E. Agrochemical Spray Drift: Assessment and Mitigation—A Review. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part B 2010, 46, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amogi, B.R.; Khot, L.R.; Patel, J.V.; Hill, S. Localized Weather Forecast Guided Spray Application Advisory Web Tool for the US Pacific Northwest. In Precision Agriculture ′25; Wageningen Academic: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 792–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallis, A.; Clements, J.; Sazo, M.M.; Kahlke, C.; Lewis, K.; Kon, T.; Gonzalez, L.; Jiang, Y.; Robinson, T. Digital Technologies for Precision Apple Crop Load Management (PACMAN) Part I. N. Y. Fruit Q. 2023, 31, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, C.; Kumar, S.K.; He, L. Integrating Computer Vision and Precision Sprayers for Targeted Green Fruit Chemical Thinning. Precis. Agric. 2025, 26, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fan | Position | Orientation | Nozzle Flow Rate (L min−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown | Yellow | |||

| 1 | Bottom | Left | 0.39 ± 0.04 | 0.67 ± 0.04 |

| 2 | Bottom | Left | 0.41 ± 0.03 | 0.69 ± 0.02 |

| 3 | Top | Right | 0.38 ± 0.03 | 0.67 ± 0.03 |

| 4 | Top | Right | 0.41 ± 0.04 | 0.66 ± 0.04 |

| 5 | Bottom | Right | 0.38 ± 0.01 | 0.68 ± 0.03 |

| 6 | Bottom | Right | 0.38 ± 0.04 | 0.70 ± 0.02 |

| 7 | Top | Left | 0.33 ± 0.03 | 0.67 ± 0.02 |

| 8 | Top | Left | 0.41 ± 0.03 | 0.66 ± 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bhalekar, D.G.; Umani, K.; Gorthi, S.; Hoheisel, G.-A.; Khot, L.R. Air and Spray Pattern Characterization of Multi-Fan Autonomous Unmanned Ground Vehicle Sprayer Adapted for Modern Orchard Systems. Agronomy 2026, 16, 344. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030344

Bhalekar DG, Umani K, Gorthi S, Hoheisel G-A, Khot LR. Air and Spray Pattern Characterization of Multi-Fan Autonomous Unmanned Ground Vehicle Sprayer Adapted for Modern Orchard Systems. Agronomy. 2026; 16(3):344. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030344

Chicago/Turabian StyleBhalekar, Dattatray G., Kingsley Umani, Srikanth Gorthi, Gwen-Alyn Hoheisel, and Lav R. Khot. 2026. "Air and Spray Pattern Characterization of Multi-Fan Autonomous Unmanned Ground Vehicle Sprayer Adapted for Modern Orchard Systems" Agronomy 16, no. 3: 344. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030344

APA StyleBhalekar, D. G., Umani, K., Gorthi, S., Hoheisel, G.-A., & Khot, L. R. (2026). Air and Spray Pattern Characterization of Multi-Fan Autonomous Unmanned Ground Vehicle Sprayer Adapted for Modern Orchard Systems. Agronomy, 16(3), 344. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030344