Abstract

Identifying plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria tolerant to saline–alkali conditions is critical for developing effective microbial agents and multi-strategy approaches to remediate saline–alkali soil. Two salt–alkali-tolerant bacterial strains—phosphorus-solubilizing Bacillus pumilus JL-C and cellulose-decomposing B. halotolerans XW-3—were isolated from saline–alkali soil, with both exhibiting multiple plant-growth-promoting properties, including nitrogen fixation and the generation of indole-3-acetic acid, siderophores, and 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase. Alfalfa pot experiments were conducted under four treatments: a control, the strain JL-C treatment, the strain XW-3 treatment, and a co-inoculation treatment (JL-C/XW-3), all mixed with corn straw and applied to the saline–alkali soil. The results demonstrated that the co-inoculation treatment yielded the most significant growth-promoting effects on alfalfa, showing enhanced antioxidant enzyme activities; increased contents of proline, soluble sugar, and protein; reduced malondialdehyde content; lowered pH and electrical conductivity; elevated activities of key enzymes; and increased levels of available nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and organic matter content in the soil. The pot experiments were confirmed by field experiments. The results of 16S rRNA high-throughput sequencing revealed changes in the bacterial community composition in the alfalfa rhizosphere, showing shifts in the relative abundance of several bacterial taxa often reported as plant-associated or potentially beneficial. This study establishes a combined remediation strategy for saline–alkali soil utilizing complex microbial agents and corn straw.

1. Introduction

As the levels of soil decomposition and the coverage of salinized soil are increasing, the effective agricultural land is substantially decreasing. Salinized soil compaction leads to decreased contents of soil nutrients and organic matter, significantly impairing plants’ ability to absorb nutrients and thereby inhibiting crop growth [1,2]. As land resources are inefficiently utilized and human livelihoods are adversely affected, it is therefore necessary to address the soil salinization issue.

Traditional physical and chemical soil improvement methods can improve soil properties in the short term. However, these approaches not only involve high costs but also pose significant environmental risks, potentially triggering secondary pollution and associated environmental problems. Considering these environmental risks, developing environmentally friendly and sustainable biological improvement technologies has become an important research focus in the field. Li et al. [3] have reported that planting salt-tolerant plants can effectively increase the content of readily available nutrients and organic matter in saline–alkali soils while reducing soil salinity. Experimental evidence indicates that planting salt-tolerant crops, through harvesting and mowing, can reduce soil salinity and increase the agricultural productivity of saline–alkali land. Ning et al. [4] have isolated a potential salt-tolerant growth-promoting bacterium, Enterobacter asburiae D2, from rhizosphere soil, which was shown to mitigate the adverse effects of salt stress on rice, thereby promoting rice growth. Furthermore, post-inoculation, significant increases were observed in plant height, root length, chlorophyll content, and proline (Pro) content. Moreover, applying green manure and microbial inoculants promotes the proliferation of soil microorganisms and the formation of organic matter in saline–alkali soils, thereby improving soil fertility and enhancing its physicochemical properties [4].

As a natural organic fertilizer resource, corn straw has demonstrated multiple significant benefits when appropriately managed. On the one hand, it can reduce air pollution caused by traditional burning methods, thereby reducing environmental pollution. On the other hand, returning corn straw to the soil plays an important role in soil improvement. Previous studies have demonstrated that when crushed corn straw is buried into the soil, the soil structure can be altered by the change in physical (i.e., increasing soil moisture, reducing soil bulk density, and increasing soil porosity) and chemical (i.e., improving soil fertility and reducing soil salinity) properties [5,6]. Furthermore, corn straw is decomposed into plant-available substances by soil microorganisms, ultimately enhancing the contents of nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and organic matter in the soil [7]. In addition, corn straw returning also has been shown to increase crop yields. For example, He et al. [8] investigated the effects of dynamic nitrogen application combined with straw incorporation on soil properties, rice yield, and grain quality through a 3-year trial conducted across different regions. The results indicate that dynamic nitrogen application under straw incorporation significantly improved soil properties, thereby enhancing rice yields. Multi-year average data revealed that the straw-returning treatment not only resulted in higher yield than the conventional control but also exhibited a higher effective tillering rate, panicle number, and grain number per panicle in rice. Collectively, these findings indicate that straw-returning has become an important strategy for improving soil quality and enhancing soil fertility in agricultural systems [8].

Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.), a perennial leguminous plant, exhibits strong adaptability and can survive under adverse environmental conditions such as drought and salinization. Owing to its advantages, including a high nutritional value and high yield, alfalfa is widely cultivated as a major forage crop worldwide, with a global cropping area exceeding 40 million hectares [9]. Alfalfa plants possess well-developed root systems that can loosen the soil while absorbing soil nutrients, coupled with high water update capacity and nitrogen-fixing capacities. Furthermore, alfalfa is commonly used to enhance soil nitrogen cycling and improve soil fertility [10,11]. In addition, alfalfa exhibits tolerance to abiotic stresses such as salinity, drought, and low temperatures. Therefore, alfalfa is commonly used as a model plant for improving saline–alkali soils. For example, alfalfa increased the organic carbon content in saline soils by more than 50%, which was mainly driven by two mechanisms, i.e., the nitrogen-fixing activity of alfalfa roots and the decomposition of alfalfa litter, which served as a major source of soil organic matter [12,13].

Plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) are soil bacteria inhabiting the plant rhizosphere and have been extensively studied for their roles in enhancing plant stress resistance under adverse conditions. They promote plant growth through various mechanisms, such as phosphorus solubilization, nitrogen fixation, potassium mobilization, and indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) secretion [14]. These substances not only reduce soil salinity by decreasing salt ions like Na+ but also significantly enhance the soil physicochemical properties and microbial community structure. Furthermore, PGPR can produce a variety of secondary metabolites, antibiotics, hydrolases, and cellulases to contribute to plant abiotic stress tolerance [15]. For example, it has been demonstrated that saline–alkali stress significantly increases soil electrical conductivity (EC), pH, and total salt content while markedly reducing soil organic matter and ammonium nitrogen levels, whereas the application of the microbial inoculant mitigates these adverse effects of saline–alkali stress, resulting in significantly enhanced crop yields [16]. Similarly, it has been reported that under salt stress, application of salt-tolerant PGPR significantly promotes maize seedling growth; increases the soil enzyme activity; and elevates the soil total nitrogen, organic carbon, microbial carbon, and nitrogen content [17]. Concurrently, it reduces soil salt concentrations, indicating that salt-tolerant PGPR enhance maize seedling salt tolerance by directly or indirectly improving the rhizosphere soil environment [17]. Collectively, these studies demonstrate that PGPR can increase soil nutrient availability, mitigate saline–alkali stress, and regulate soil microbial communities, thereby enhancing plant nutrient uptake and promoting growth [15,16].

In summary, previous studies on saline–alkali soil remediation using PGPR or corn straw amendments have largely focused on the effects of single-function strains or corn straw return alone, lacking systematic designs and mechanistic validations of multi-functional microbial consortia synergizing the corn straw decomposition and plant-growth-promoting effect. To address this research gap, our study was designed to answer a core scientific question: how can we achieve integrated and sustainable improvement of the physical, chemical, and biological properties of saline–alkali soil by constructing a synergistic “microbe–corn straw–plant” system with complementary functions and efficient material cycling?

To date, the ongoing expansion of saline soils and the consequent shrinkage of arable land not only hinder crop growth but also pose a major constraint on global agricultural productivity. Therefore, there is an urgent need to alleviate soil salinization to ensure sustainable agricultural production. In this study, a combined remediation strategy, i.e., composite microbial agents and corn straw, was developed to enhance the synergistic interactions between microorganisms, corn straw, and crops. The aims of this study were to explore the mechanisms underlying the alleviating effects of this strategy on saline–alkali stress on plants, to investigate the alteration in the microbial community composition of the plant rhizosphere, and to improve the quality of saline–alkali soil. Based on this integrated approach, this study proposed and constructed a tripartite synergistic remediation framework: saline–alkali-tolerant multifunctional microbial consortium, corn straw, and alfalfa. In this framework, corn straw serves as both a carbon carrier and a physical amendment, while the cellulose-decomposing and phosphate-solubilizing bacteria act as the primary functional drivers, facilitating the transformation and supply of key nutrients, such as carbon and phosphorus. Together with alfalfa’s nitrogen fixation in roots, the material cycling and energy flow is formed in this integrated system, ultimately achieving the simultaneous mitigation of saline–alkali stressors and systematic enhancement of soil ecological functions. This study not only provides a practical multi-strategy approach for saline–alkali soil remediation but also offers a designable and testable theoretical model for soil bioremediation from the perspective of ecological interactions.

The novelty of this study is primarily reflected in the following aspects: (1) Shifting from “single function” to “system integration” in the application of bacterial taxa. Multifunctional bacterial strains—the phosphate-solubilizing bacterial strain JL-C and the cellulose-decomposing bacterial strain XW-3, both isolated from saline–alkali soil—were identified and selected for use in this study. They simultaneously enable phosphorus activation, carbon supply, and multiple plant-growth-promoting functions such as IAA and siderophore production, thereby overcoming the functional limitations of single-strain inoculants. (2) A change from “simple addition” to “mechanism-driven approach” in the experimental strategy. Through targeted corn straw decomposition by the cellulose-decomposing bacterial strain, a positive feedback cycle of “straw decomposition → carbon release → microbial activation → nutrient transformation” was established. This not only improved the soil structure but also enabled continuous resource flow within the system. (3) Establishment of a “plant–microbe–soil” positive feedback system. Using nitrogen-fixing alfalfa as the plant component, a symbiotic remediation model integrating plant residue–decomposing microorganisms and plant growth–promoting microorganisms was established, which significantly enhanced the system stability and remediation efficiency in the saline–alkali environment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Plants, Soil Samples, and Site

Seeds of alfalfa (mean seed weight of 0.0013 g) were obtained from Qingdao Seed Industry (Qingdao, China). The saline–alkali soil samples used in this study were collected in Zhenlai County, Baicheng City, Jilin Province, China (123°11′30″ E, 45°46′2″ N; altitude of 140 m), which is characterized by a temperate continental monsoon climate. The region had a mean annual temperature of 4.9 °C, annual sunshine duration of 2914 h, and mean annual precipitation of 402 mm.

2.2. Screening and Identification of Salt–Alkali-Tolerant Plant-Growth-Promoting Bacteria

The rhizosphere soil samples collected for strain isolation were immediately placed in sterile plastic bags, transported to the laboratory in a cooling container, and stored at 4 °C until further processing. All subsequent procedures were performed under aseptic conditions, e.g., removing plant residues, stones, and other impurities. Saline–alkali soil was mixed with sterile water at a ratio of 1:10, homogenized, and allowed to stand for 10 min at room temperature. The soil suspension was then inoculated into saline–alkali LB medium (containing yeast extract 5 g L−1, sodium chloride 15 g L−1, tryptone 10 g L−1, agar 15 g L−1; pH 9.0) and cultured at 37 °C and 180 rpm for 1 d. Salt–alkali-tolerant bacteria were isolated and purified on saline–alkali LB medium using the gradient dilution method until pure cultures were obtained and subsequently preserved in glycerol at −80 °C for further analysis. All chemicals used in the experiments were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

The bacterial colony morphology, Gram staining, starch hydrolysis, gelatin liquefaction, Voges–Proskauer (V-P) test, and catalase activity were assessed for each strain. The salt–alkali-tolerant strains were spread onto the LB medium with 10 g L−1 NaCl and a pH of 7.0, 8.0, 9.0, 10.0, or 11.0. These strains were also spread onto the LB medium with pH 7.0 and NaCl concentrations of 1%, 2%, 3%, 4%, or 5%. All chemicals used in the experiments were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All cultures were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h to determine the alkali tolerance and salt tolerance of the strains. Bacterial genomic DNA was extracted using the Bacterial Genomic DNA Extraction Kit from TIANGEN Biotech (Beijing) Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). The bacterial 16S rRNA gene was PCR-amplified using universal primers 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1492R (5′-GGCTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′). The PCR products were sent to Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) for sequencing. The 16S rRNA gene sequences of the bacterial strains were compared with reference sequences and deposited with the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/; accessed on 1 December 2023).

The plant-growth-promoting capabilities of the bacterial strains were evaluated using established assays. Phosphorus solubilization was measured using the National Botanical Research Institute’s Phosphate (NBRIP) growth medium [18]. Cellulose decomposition was detected by the cellulose Congo red agar assay [19]. Siderophore production was determined via the chrome azurol S (CAS) assay [20]. IAA production was determined by the Salkowski reaction [21]. Nitrogen fixation was tested using Ashby’s nitrogen-free medium [22]. The extraction and enzymatic activity of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate (ACC) deaminase were performed using the ACC deaminase activity assay [23].

2.3. Alfalfa Pot Experiments

Plastic pots of 15 cm (height) × 10 cm (diameter) were sterilized with 75% ethanol, air-dried, filled with 1 kg of saline–alkali soil, and sown with a total of 50 alfalfa seeds per pot. Due to the relatively low germination rate of alfalfa seeds in saline–alkali soil, 50 seeds were sown per pot based on preliminary experiments. Through thinning, uniform distribution and comparable growth vigor of the seedlings within each pot were ensured, with a final density of 10 plants per pot. Soil samples for the pot experiment were collected from the saline–alkali field using a multi-point mixing method at a depth of 0–20 cm. The soil was air-dried in a cool, ventilated place; manually crushed; and passed through a 2 mm sieve. The soil was subjected to a homogenization pretreatment, and the basic physicochemical properties were determined. Three bacterial suspensions were prepared, including Bacillus pumilus JL-C, B. halotolerans XW-3, and their composite (JL-C:XW-3 = 2:1), with the viable cell density adjusted to 2 × 108 cfu mL−1. Bacterial cells were collected by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 2 min and subsequently mixed with 0.3 g of fulvic acid as a carrier and 15 g of crushed corn straw. The corn straw was ground to a particle size of ≤2.0 cm. The pot experiments included four groups: control (CK), strain JL-C treatment, XW-3 treatment, and the composite treatment of JL-C and XW-3 (JL-C/XW-3). The CK contained only crushed corn straw, whereas the experimental groups were supplemented with the mixture of bacterial agent and fulvic acid. Each treatment included 3 biological replicates, and all treatments were randomly arranged and maintained under natural light for 21 d. The temperature was maintained at approximately 20 ± 3 °C, with an average photoperiod of 14 h. Irrigation was carried out using reverse-osmosis-purified water to eliminate the influence of differences in external water quality on soil and plants.

2.4. Determination of Growth, Physiological, and Biochemical Attributes of Alfalfa

At the end of the alfalfa pot experiments, the rhizosphere soil was carefully collected from the roots after the roots were gently washed and blotted dry to remove surface moisture. The lengths of the aboveground and belowground plant parts of alfalfa were then measured. The physiological and biochemical properties of the plants, i.e., the enzymatic activities of catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and peroxidase (POD), as well as the levels of Pro, malondialdehyde (MDA), and soluble protein and sugar, were determined according to previously reported methods [24].

2.5. Determination of Soil Physiological and Biochemical Properties and Enzyme Activities

The Soil pH; EC; contents of available nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and organic matter; and enzymatic activities of urease, sucrase, alkaline phosphatase, and cellulase were determined as previously reported [25].

2.6. Alfalfa Field Experiments

To verify the alfalfa pot experiments, the field experiments were conducted in Zhenlai County, Baicheng City, Jilin Province, China. Eight treatments were established: control (CK, with no corn straw or fulvic acid); corn straw treatment; JL-C treatment; combined corn straw and JL-C (corn straw/JL-C) treatment; XW-3 treatment; combined corn straw and XW-3 (corn straw/XW-3) treatment; combined JL-C and XW-3 (JL-C/XW-3) treatment; and combined corn straw, JL-C, and XW-3 (corn straw/JL-C/XW-3) treatment. A completely randomized design was employed using 10 m × 10 m plots, with three biological replicates per treatment. Corn straw was evenly incorporated into the top 0–10 cm soil at a rate of 1.8 kg m−2. Alfalfa seeds were sown evenly at a rate of 13 g m−2. The microbial agents were prepared as described in Section 2.3 and applied to the soil at a rate of 0.036 kg m−2. At 30 d after sowing, soil and plant samples were collected randomly from each plot using the five-point sampling method. All alfalfa and soil attributes were measured according to the methods described in Section 2.4 and Section 2.5, respectively.

2.7. Effects of Combined Remediation Method on Rhizobacterial Community of Saline–Alkali Soil

2.7.1. Soil DNA Extraction and Amplification of 16S rRNA

Rhizosphere saline–alkali soil samples were collected from the CK group and the corn straw/JL-C/XW-3 group 30 d after sowing in the alfalfa field experiment. Each treatment included 3 biological replicates. The soil samples were sent to Personalbio Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China) for the analysis of microbial diversity using the Illumina MiSeq sequencing platform. The total genomic DNA was extracted from soil sample (~0.2 g) using the OMGA Soil DNA Kit (D5635-02, Omega Bio-Tek, Norcross, GA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The DNA integrity was assessed by 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis (DYY-6C, Liuyi Instrument, Beijing, China), and the DNA concentration was measured using a NanoDrop NC2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The V3–V4 hypervariable region of the bacterial 16S rRNA (~468 bp) was amplified using barcoded primers 338F (5′-barcode+ACTCTACGGAGGCAGCA-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′). PCR reactions were performed in a 25 µL mixture containing 0.25 µL of Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB, M0491L), 5 µL of 5× Reaction Buffer, 5 µL of 5× High GC Buffer, 2 µL of dNTPs (10 mM), 2 µL of template DNA, 1 µL each of forward and reverse primers (10 µM), and 8.75 µL of nuclease-free water. The thermal cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 98 °C for 5 min; 25 cycles of 98 °C for 30 s, 53 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 45 s; and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. Negative controls (no DNA template) and positive controls (DNA from a known bacterial strain) were included in each PCR run to monitor the contamination and amplification efficiency.

2.7.2. Library Preparation and Sequencing

The PCR products were purified by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis and recovered using the Axygen Gel Extraction Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Sequencing libraries were constructed using the Illumina TruSeq Nano DNA LT Library Prep Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, including end repair, A-tailing, adapter ligation, and PCR enrichment. The library quality was assessed using an Agilent High Sensitivity DNA Kit on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Quantification was performed using the Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit (P7589, Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Qualified libraries with concentrations ≥ 2 nM were pooled in equimolar amounts. Paired-end sequencing (2 × 250 bp) was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform using the NovaSeq 6000 SP Reagent Kit (500 cycles; Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The final loading concentration was adjusted to 15 pM. The original DNA sequencing data were deposited to NCBI database under BioProject accession PRJNA1405079.

2.7.3. Bioinformatics Processing

Raw sequencing data were processed using QIIME2 (version 2019.4). Primer sequences were removed with cutadapt. Quality filtering, denoising, merging of paired-end reads, and chimera removal were performed using the DADA2 plugin. Sequences were clustered into Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) at 100% similarity. ASVs with an abundance lower than 0.001% of the total sequences across all samples were removed as rare taxa. Taxonomic assignment was performed against the SILVA reference database (release 138) using the classify-sklearn method.

2.7.4. Microbial Community Analysis

The sequencing depth in the field experiment was evaluated using rarefaction curves. Using QIIME (version 2019.4), random subsampling was performed based on the total sequence count of each sample in the ASV abundance matrix at various sequencing depths. Rarefaction curves were plotted with the number of sequences sampled at each depth against the corresponding number of ASVs. Alpha diversity indices, including Chao1, Observed_species, Shannon, Simpson, and Pielou’s evenness, were calculated after rarefying all the samples to the minimum sequencing depth; the Kruskal–Wallis test was used to determine statistical significance. When significant differences were identified, pairwise comparisons were conducted using Dunn’s post hoc test. The beta diversity was assessed using Bray–Curtis distances and visualized via principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) and hierarchical clustering analysis. Based on the taxonomic assignment of ASVs, the taxonomic composition of each sample at different classification levels was summarized and bar plots were then generated using R software (v3.2.0). Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) was used to test for significant differences in community structure between the groups. Linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) was applied to identify differentially abundant taxa.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 26.0. Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). An independent samples t-test was used to compare the differences between the two groups, whereas one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was performed to compare the differences between multiple groups. The significance level was set at p ≤ 0.05. Graphs were generated with GraphPad Prism 10.2.

3. Results

3.1. Screening and Identification of Salt–Alkali-Tolerant Bacterial Strains

Salt-tolerant bacterial strains were inoculated onto NBRIP medium and Congo red medium to screen for phosphate-solubilizing bacteria and cellulose-decomposing bacteria, respectively. A total of seven salt-tolerant phosphate-solubilizing strains and five salt-tolerant cellulose-decomposing strains were initially obtained. Based on further evaluation of their salt–alkali tolerance and plant-growth-promoting effects, two bacterial strains (JL-C and XW-3) exhibiting multiple growth-promoting functions were selected for further analysis. Taxonomic identification was performed based on morphological characteristics, 16S rRNA gene sequences, and physiological and biochemical attributes. The results indicate that both strains were rod-shaped and were positive for the Gram staining, starch hydrolysis test, gelatin liquefaction test, V-P test, and catalase activity (Table 1). Both strains exhibited tolerance to 50 g L–1 NaCl, while strains JL-C and XW-3 maintained growth at pH 11.0 and pH 10.0, respectively. In addition, both strains produced siderophores, IAA, and ACC deaminase. Strain JL-C exhibited phosphorus-solubilizing ability and showed the highest 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity (99.9%) to B. pumilus VLP6 and was therefore designated as B. pumilus JL-C (GenBank accession OR888714). Strain XW-3 displayed cellulose-decomposing ability and showed the highest 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity (100%) to B. halotolerans HFBPR26 and was therefore designated as B. halotolerans XW-3 (GenBank accession OR888715).

Table 1.

Bacterial identification and plant-growth-promoting ability assessment of strains Bacillus pumilus JL-C and B. halotolerans XW-3. Symbols “+” and “−” indicate positive and negative, respectively.

3.2. Effects of Different Bacterial Treatments on Growth, Physiological, and Biochemical Attributes of Alfalfa

At 21 d after sowing, the potted alfalfa plants in the JL-C/XW-3 treatment group exhibited the greatest growth for both the aboveground and belowground growth compared with those in the CK and single-strain treatment groups. The aboveground and belowground plant heights of the JL-C/XW-3 group reached 8.31 and 7.52 cm, representing increases of 42.54% and 142.58% compared with the CK group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effects of different treatments on the growth attributes of alfalfa. Different superscript letters in the same row indicate significant differences between the groups (p ≤ 0.05; one-way ANOVA).

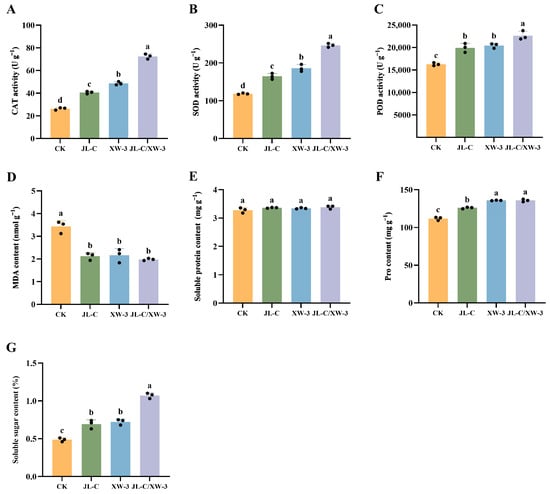

SOD, POD, and CAT all belong to the plant antioxidant enzyme system, and their activities are closely associated with plant stress tolerance, while MDA content is a key attribute of the degree of plant oxidative damage. The activities of CAT, SOD, and POD in the JL-C/XW-3 group were 74.58 U g−1, 246.71 U g−1, and 23752.89 U g−1, respectively. These values were significantly higher than those in the other three treatment groups. Compared with the CK group, the activities of CAT, SOD, and POD increased by 175.00%, 108.12%, and 258.06%, respectively (Figure 1A–C). The activities of CAT, SOD, and POD in the JL-C/XW-3 group were significantly higher than those in the other three groups, increasing by 175.00%, 108.12%, and 258.06%, respectively, compared with the CK group (Figure 1A–C). In contrast, the MDA content decreased in all three groups treated with microbial agents, either individual strains or combined, with no significant differences observed between the three groups (Figure 1D); the level of MDA was increased to 2.02 nmol g–1, which was an increase of 35.26% compared with the CK group (3.12 nmol g−1). These results indicate that the application of the microbial agents probably reduced membrane lipid peroxidation in the alfalfa. No significant difference was observed in the soluble protein content across all four groups (Figure 1E). The proline and soluble sugar contents reached their peak values of 135.82 mg g−1 and 1.07% under the JL-C/XW-3 treatment, marking increases of 21.43% and 122.92% over the CK group, respectively (Figure 1F,G). Overall, these results indicate that the application of the combined microbial agents improved the growth, physiological, and biochemical parameters of the potted alfalfa plants.

Figure 1.

Physiological and biochemical attributes of alfalfa plants in the pot experiments, showing CAT activity (A), SOD activity (B), POD activity (C), MDA content (D), soluble protein content (E), proline (Pro) content (F), and soluble sugar content (G). Different lowercase letters a, b, c, and d indicate significant differences between the groups (p ≤ 0.05; one-way ANOVA). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 independent biological replicates). Individual data points are shown as black dots.

3.3. Effects of Different Bacterial Treatments on Soil Physiological and Biochemical Attributes

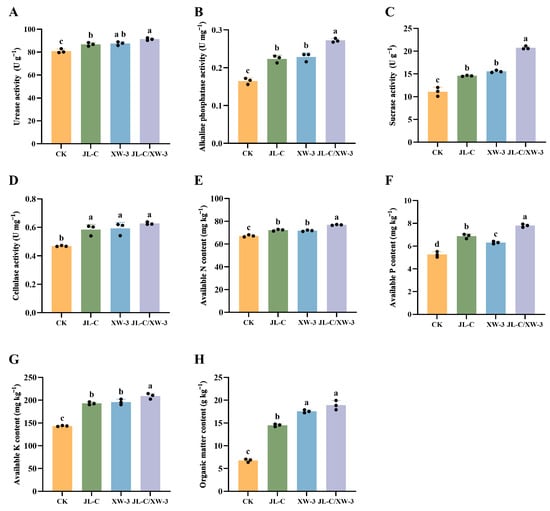

In the soil of all three groups treated with microbial agents, either with individual strains or combined, both the soil pH and EC were lower than those in the CK group (Table 3). Compared with the CK group, the JL-C/XW-3 group showed the greatest reductions in pH and EC, by 2.56% and 36.25%, respectively, while the enzymatic activities of urease, alkaline phosphatase, sucrase, and cellulase, which are four attributes of soil biological activity, increased by 12.86%, 68.75%, 87.11%, and 34.78%, respectively (Figure 2A–D). Furthermore, the contents of soil available nitrogen, available phosphorus, available potassium, and organic matter were 14.28%, 48.29%, 45.31%, and 178.20% higher than those in the CK group, respectively (Figure 2E–H). These results suggest that applying composite microbial agents significantly enhanced these soil physiological and biochemical properties and was associated with alleviation of saline–alkali-induced salt stress in alfalfa.

Table 3.

Effects of different bacterial treatments on soil properties. Different superscript letters in the same row indicate significant differences between the groups (p ≤ 0.05; one-way ANOVA).

Figure 2.

Physiological and biochemical attributes of soil in alfalfa pot experiments, showing urease activity (A), alkaline phosphatase activity (B), sucrase activity (C), cellulase activity (D), available nitrogen content (E), available phosphorus content (F), available potassium content (G), and organic matter content (H). Different lowercase letters a, b, c, and d indicate significant differences between the groups (p ≤ 0.05; one-way ANOVA). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 independent biological replicates). Individual data points are shown as black dots.

3.4. Effects of Different Bacterial Treatments on Physiological and Biochemical Attributes of Alfalfa in the Field Experiments

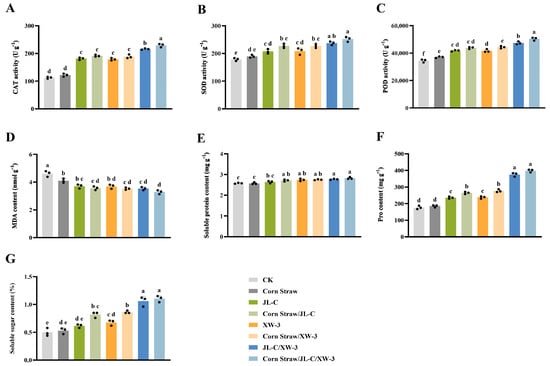

In the field experiment, the corn straw/JL-C/XW-3 treatment significantly enhanced the enzymatic activities of CAT, SOD, and POD in the alfalfa plants at 30 d after sowing compared with the CK group. The activities reached 229.46 U g−1, 251 U g−1, and 54,474 U g−1, representing increases of 103.55%, 40.49%, and 76.96%, respectively (Figure 3A–C). The MDA content was the lowest in the corn straw/JL-C/XW-3 group (Figure 3D). Furthermore, the three osmotic adjustment substances, i.e., soluble protein, Pro, and soluble sugar, showed increases of 7.39%, 125.71%, and 124.49%, respectively, compared with the CK group (Figure 3E–G).

Figure 3.

Physiological and biochemical attributes of alfalfa in the field experiments, showing the CAT activity (A), SOD activity (B), POD activity (C), MDA content (D), soluble protein content (E), Pro content (F), and soluble sugar content (G). Different lowercase letters a, b, c, d, e, and f indicate significant differences between the groups (p ≤ 0.05; one-way ANOVA). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 independent biological replicates). Individual data points are shown as black dots.

3.5. Effects of Different Bacterial Treatments on Soil Physiological and Biochemical Attributes in Alfalfa Field Experiments

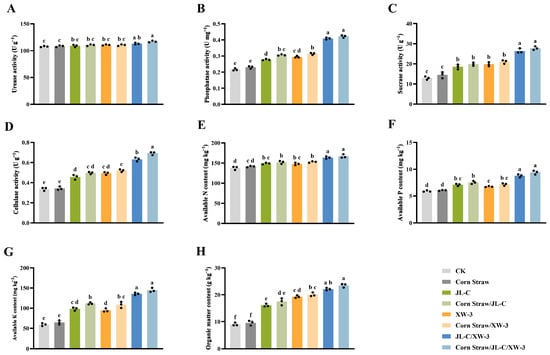

Application of single-strain agents or corn straw reduced the soil pH and EC, while the combined treatment of two microbial agents and corn straw resulted in the greatest reduction in the soil pH and EC (Table 4). In the corn straw/JL-C/XW-3 treatment group, the enzymatic activities of urease, sucrase, phosphatase, and cellulase were significantly enhanced compared with the control. The activities reached 117.03 U g−1, 27.77 U g−1, 0.42 U mg−1, and 0.69 U g−1, respectively, representing increases of 8.63%, 114.61%, 100.00%, and 109.09% (Figure 4A–D). The contents of available nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and organic matter reached 166.70 mg kg−1, 9.41 mg kg−1, 144.63 mg kg−1, and 23.51 g kg−1, respectively, increasing by 20.36%, 56.31%, 143.90%, and 161.22%, respectively, compared with the CK group (Figure 4E–H).

Table 4.

Effects of different biological agents on the soil properties in the alfalfa field experiment. Different superscript letters in the same row indicate significant differences between the groups (p ≤ 0.05; one-way ANOVA).

Figure 4.

Physiological and biochemical attributes of soil in the alfalfa field experiments, showing the urease activity (A), phosphatase activity (B), sucrase activity (C), cellulase activity (D), available nitrogen content (E), available phosphorus content (F), available potassium content (G), and organic matter content (H). Different lowercase letters a, b, c, d, e, and f indicate significant differences between the groups (p ≤ 0.05; one-way ANOVA). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 independent biological replicates). Individual data points are shown as black dots.

3.6. Effects of Different Bacterial Treatments on Soil Microorganisms in the Alfalfa Field Experiments

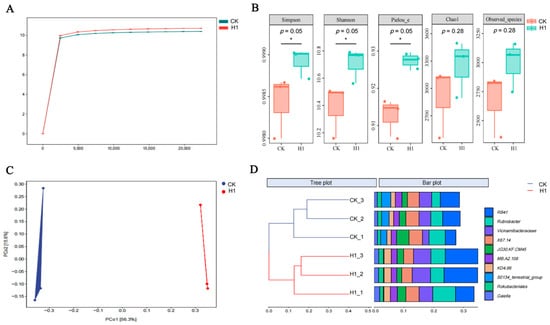

A rarefaction curve analysis was performed on the Shannon index of soil microorganisms. The results showed that as the number of sequenced reads increased, the Shannon index gradually leveled off and eventually reached a plateau (Figure 5A), suggesting that the sequencing depth sufficiently captured the bacterial community structure in the rhizosphere soil and the sequencing data were highly reliable and suitable for further analysis. The 16S rRNA sequences of B. pumilus and B. halotolerans were subjected to alignment with the OUT/ASV sequences derived from soil microbial diversity analysis (Tables S1 and S2, respectively).

Figure 5.

Effects of combined remediation (corn straw/JL-C/XW-3 treatment) on the soil microbial diversity and community composition in the alfalfa field experiments. CK, the control group; H1, the corn straw/JL-C/XW-3 group. (A) Rarefaction curves of the Shannon index. (B) Soil microbial α-diversity indices. Asterisks indicate significant differences based on the Kruskal–Wallis H test (* p ≤ 0.05). (C) Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) based on the Bray–Curtis distance. (D) Hierarchical clustering dendrogram based on the Bray–Curtis distance. Both the PCoA and clustering analysis revealed significant separation in community structure between the treatment and CK groups (PERMANOVA; p < 0.05).

Compared with the control group, the Chao1 and Observed_species indices of the corn straw/JL-C/XW-3 group showed an increasing trend in species richness, although the changes were not statistically significant (p = 0.28; Figure 5B), whereas the Simpson, Shannon, and Pielou_e indices indicate that the corn straw/JL-C/XW-3 group exhibited a significantly higher microbial community diversity and a more even species distribution (p = 0.05), which was associated with a more balanced community structure and stabilized soil microenvironment. The beta diversity analysis further revealed inter-group differences. PCoA showed clear separation between the samples from the corn straw/JL-C/XW-3 treatment group and the CK in the coordinate space (Figure 5C). Consistent with this, hierarchical clustering analysis based on the Bray–Curtis distance demonstrated that all the samples were distinctly clustered into two major groups corresponding to the CK and H1 (corn straw/JL-C/XW-3) treatment groups, respectively (Figure 5D). This pattern indicates high consistency between the biological replicates within each group and significant differences between the groups, strongly suggesting that the combined treatment with microbial consortia and corn straw serves as a key driver altering the rhizosphere bacterial community structure. In summary, this combined remediation strategy significantly enhanced the diversity and evenness of the soil microbial community, thereby driving a shift in community composition. Its mechanism of action focused more on optimizing the community structure rather than simply increasing the species richness.

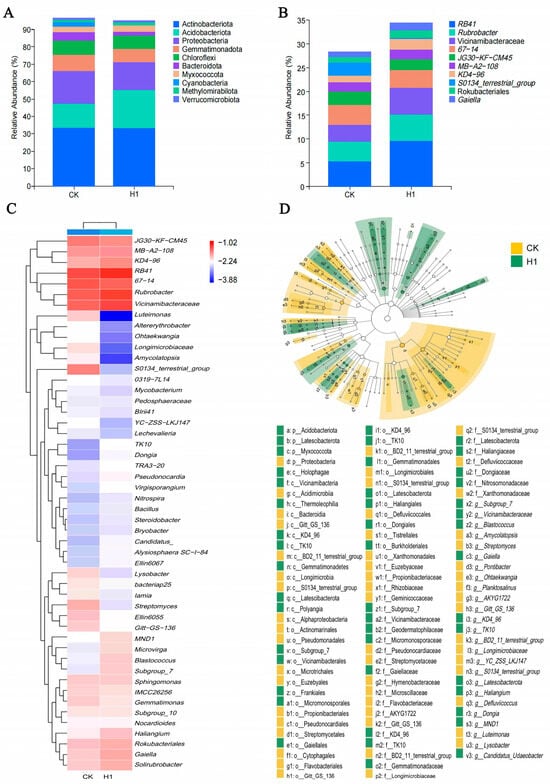

Among the top 10 most abundant bacterial phyla in the corn straw/JL-C/XW-3 group, the relative abundances of Acidobacteriota, Myxococcota, Methylomirabilota, and Verrucomicrobiota increased, whereas those of Actinobacteriota, Proteobacteria, Gemmatimonadota, Bacteroidota, Chloroflexi, and Cyanobacteria decreased (Figure 6A). Among the top 10 most abundant bacterial taxa at the genus levels, RB41 exhibited the highest abundance in the rhizosphere soil (Figure 6B). The relative abundances of Rubrobacter, Vicinamibacteraceae, MB-A2-108 (Actinobacteriota), KD4-96 (Chloroflexi), Rokubacteriales, and Gaiella were elevated, whereas they were decreased in 67-14 (Bacteroidota), JG30-KF-CM45 (Pseudomonadota), and S0134_terrestrial_group (Acidobacteria). The heatmap analysis revealed the co-enrichment of Vicinamibacteraceae, Gaiella, Haliangium, and Dongia in the treatment group (Figure 6C). These four microbial groups represent organic matter decomposers, photoheterotrophic bacteria, and predatory regulators. Their synchronous increase was likely driven by the combined remediation treatment, thereby contributing to the formation of a more stable rhizosphere micro-ecosystem. The LEfSe analysis revealed that the biomarker taxa specific to the combined remediation treatment group were broadly distributed across multiple phylogenetic branches within phyla of Acidobacteriota, Myxococcota, and Latescibacterota (Figure 6D). These results suggest that the treatment likely exerted a widespread positive selection pressure on the microorganisms belonging to these phyla.

Figure 6.

Effects of combined remediation (corn straw/JL-C/XW-3 treatment) on the abundance, structure, and biomarkers of the microbial community in the alfalfa field experiments. CK, the control group; H1, the corn straw/JL-C/XW-3 group. (A) Composition at the phylum level. (B) Composition at the genus level. Only the top 10 most relatively abundant taxa are shown based on the Kruskal–Wallis H test (p < 0.05). The composition at the class level is provided in Figure S1. (C) Hierarchical clustering heatmap of bacterial abundance at the genus level based on the Kruskal–Wallis H test (p < 0.05). Hierarchical clustering heatmap of bacterial abundance at the phylum and class levels are provided in Figures S2 and S3, respectively. (D) LEfSe analysis of the microbial community, showing the taxonomic hierarchy of major taxonomic units from phylum to genus (displayed from the inner to the outer rings) in the sample communities with a Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) score > 2.0. The taxonomic hierarchy from phylum to genus is displayed from the inner to outer circles. The colored nodes represent taxa with significant differences, and the node size corresponds to the mean relative abundance.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of the Combined Remediation Method on Saline–Alkali Soil

The synergistic effects of combined microbial inoculants and corn straw address issues in saline–alkali soils such as high salinity and alkalinity, nutrient deficiency, and soil compaction. On the one hand, corn straw could contribute to the physical improvement of saline–alkali soils by loosening the soil to alleviate soil compaction, thereby enhancing the water retention and aeration capacity [26]. Furthermore, applying corn straw to soil increases the soil organic matter content [7]. Moreover, the organic matter content is positively correlated with the soil fertility status [27,28]. On the other hand, corn straw can be decomposed by the salt–alkali-tolerant, cellulose-decomposing strain XW-3 into organic acids, which potentially reduces the pH of saline–alkali soils. This process may provide organic matter and a suitable soil environment for phosphate-solubilizing bacteria or other PGPR.

The phosphorus content is a reliable attribute of soil nutrient availability. In saline–alkali soils, phosphorus is primarily present as insoluble phosphates, which can be converted by phosphate-solubilizing bacteria into plant-available forms [29]. Myxococcota are considered plant-beneficial bacteria, producing secondary metabolites, suppressing pathogens, and enhancing plant stress resistance [30], and their relative abundances are positively correlated with the total organic acid content in the soil [31]. Our results suggest that the application of the consortia microbial agents with corn straw modified the microbial community structure in the saline–alkali soil, potentially leading to an enrichment of Myxococcota in the alfalfa rhizosphere. Given its known functions in cellulose decomposition, nutrient enhancement, and promoting network stability, this shift suggests a potential mechanistic link to soil improvement [32]. Functioning as a core taxon at the genus level in saline–alkali soils, RB41 (Acidobacteriota) mitigates salt stress through the regulation of soil physiological and biochemical properties [33]. It also stabilizes the microbial community by suppressing pathogenic bacteria such as Fusarium and Humicola, thereby enhancing the stability and resilience of the microbial community [34]. Vicinamibacteraceae (Acidobacteriota) is potentially involved in soil pH regulation, with its relative abundance correlated with pH variation; Vicinamibacteraceae function as a group of straw-decomposing bacteria, promoting corn straw decomposition and organic matter accumulation, ultimately improving the soil structure, nutrient availability, and ecological function in saline–alkali environments [35,36,37]. KD4-96 (Chloroflexi) serves as a key hub taxon at the genus level, stabilizing the microbial network through extensive connections and participating in carbon and phosphate cycling and heavy metal biotransformation [38,39]. Rubrobacter and Gaiella, both in the phylum Actinomycetota, contribute distinctly to soil amelioration, while Rubrobacter mitigates salinity–alkalinity stress by contributing to nutrient cycling and enhancing microbial community resilience, thereby alleviating soil pH imbalance and nutrient deficiency [40].

In summary, the combined remediation method altered the microbial community structure, resulting in enhanced soil enzyme activity, a more stable and balanced rhizosphere microbial community, and greater relative abundances of corn-straw-decomposing microorganisms, thereby potentially improving the utilization efficiency of soil nutrients.

4.2. Plant-Growth-Promoting Effects of the Combined Remediation Approach

Our study suggested that the integrated remediation approach could effectively address the limitations of individual amendment methods, including the extended remediation period associated with straw incorporation and the limited growth-promoting and colonization abilities of single-strain inoculants. Furthermore, the major physiological and biochemical parameters of soil and alfalfa under the integrated approach (corn straw/JL-C/XW-3) surpassed those in treatments involving combined bacterial inoculants, single bacterial strains with corn straw, individual bacterial strains, and corn straw alone. This comprehensive improvement indicates a potentially positive synergistic effect between the microbial inoculants and corn straw.

Studies have shown that a combined remediation approach enhances plant resistance to saline–alkali stress. For example, the application of compound microbial inoculants significantly mitigated saline–alkali stress in wheat, with significant increases in Pro, total soluble sugar, soil organic matter, and antioxidant enzyme activity [41]. These studies are consistent with our findings, suggesting that the combined application of microbial inoculants and corn straw could result in increased Pro, soluble protein, and soluble sugar content, thereby reducing oxidative damage in alfalfa caused by saline–alkali stress and consequently promoting plant growth.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the co-application of low-temperature-decomposing bacteria and corn straw significantly reduced the soil pH and EC in saline–alkali soils while increasing rice yields [42]. Microorganisms can promote the plant uptake of ions in the soil, leading to a decrease in EC [43]. In our study, the synergistic effect of corn straw and compound microbial inoculants could reduce the pH and EC of the saline–alkali soil, mitigating Na+-induced stress in the rhizosphere and alleviating osmotic stress. Furthermore, the combined remediation approach enhanced soil enzyme activities and improved nutrient availability, enhancing the availability of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium to plants. In addition to their capabilities in phosphorus solubilization and cellulose decomposition, both strains of JL-C and XW-3 exhibited a range of plant-growth-promoting traits, such as the production of siderophores, IAA, and ACC deaminase. These results suggest that these traits could collectively enhance plant biomass accumulation. Moreover, they could enhance the alfalfa antioxidant defense capacity and increase the intracellular osmotic pressure, thereby potentially alleviating saline–alkali stress.

The combined remediation strategy also enhanced the relative abundances of beneficial bacteria in the alfalfa rhizosphere. Acidobacteriota is a common and relatively dominant bacterial phylum in saline–alkali environments, possessing a diverse genetic repertoire for plant growth promotion. The environmental functions of this phylum include nitrogen fixation, phosphate solubilization, and potassium mobilization, which directly enhance plant nutrient acquisition [44]. Moreover, this phylum can produce exopolysaccharides, siderophores, and phytohormones (e.g., auxins and cytokinins), thereby resulting in direct growth-promoting effects [45,46]. By forming stable biofilms on root surfaces, they efficiently colonize the rhizosphere, suppress potential pathogens through competitive interactions, and enhance plant–microbe interactions [47]. Their metabolic activities also contribute to the maintenance of soil physiological and biochemical homeostasis, enabling adaptation to diverse pH conditions. As core functional members of the Acidobacteriota, both groups of RB41 and KD4-96 enhance soil nutrient availability and reduce pathogen pressure on plants through their roles in carbon cycling and nutrient transformation [48]. This optimization of the soil microenvironment could indirectly facilitate plant establishment and growth, which, in turn, improves plant adaptive capacity to saline–alkali and other decomposed conditions [49]. These two taxa contribute to microbial community homeostasis and regulate soil physicochemical and enzymatic balances, ultimately maintaining overall soil health [50]. Previous studies have demonstrated that an increase in the relative abundance of Vicinamibacteraceae is correlated with improved root growth and plant biomass [51]. Our results demonstrate that the combined remediation method of both bacteria and corn straw could improve the rhizosphere microbial community in saline–alkali soil, resulting in a shift in microbial community structure and thereby leading to an increased soil enzyme activity and a more stable, balanced microenvironment. In summary, the proliferation of beneficial rhizobacteria likely represents a key mechanism through which the complex microbial agents enhance alfalfa growth and alleviate soil stress under saline–alkali conditions.

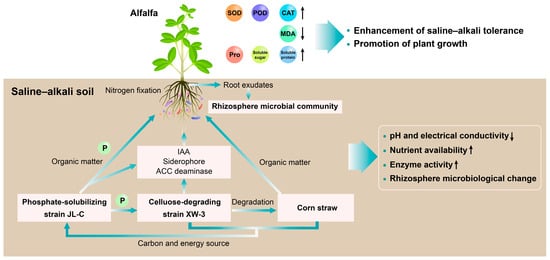

This study demonstrates the dynamic nature of the remediation process based on the consortia microbial agents (Figure 7). The effects of this integrated strategy do not represent a linear improvement but are centered on the activation and enhancement of the plant’s physiological stress-resistance system as the core feedback node. The initial improvement in soil and microorganisms (external drivers) directly contributes to significant enhancements in plant physiological health (internal responses) by alleviating stress and providing nutrients. In turn, healthy plants transform into the “vitality engine” of the system, providing sustained energy and carbon sources into the microbial community through enhanced photosynthetic carbon fixation and root secretion functions, thereby driving the optimization of the microbial community structure and functional improvement through positive feedback. As a result, the three components—improving soil, optimizing microorganisms, and strengthening plants—are tightly coupled through the three aforementioned cycles, forming a self-sustaining and even self-reinforcing positive feedback system for ecological restoration.

Figure 7.

Potential effects of the combined remediation strategy on plant growth promotion and saline–alkali soil improvement.

The limitations of this study are noted. It is important to further explore the long-term effects of the combined remediation strategy, and the community stability still requires continuous monitoring. Future work could integrate metagenomics and labeling techniques to analyze the operational mechanisms of this synergistic system across larger spatiotemporal scales and explore its compatibility with different crop plants.

5. Conclusions

This study systematically investigated the efficacy and underlying mechanisms of a combined remediation strategy, integrating consortia microbial inoculants with corn straw, for saline–alkali soil improvement and alfalfa growth promotion. We utilized both pot and field experiments in conjunction with soil physicochemical analysis, plant physiological assays, and high-throughput microbial sequencing. The results demonstrate that this approach significantly enhanced the soil properties, including the pH, EC, nutrient availability, and enzyme activities, while reshaping the rhizosphere microbial community structure and enriching various functionally beneficial microbial taxa. These microorganisms potentially contribute to straw decomposition, nutrient cycling, and microbial network stability, thereby providing a microecological basis for the sustained improvement of the soil environment. Concurrently, the strategy significantly alleviated salt–alkali stress in alfalfa by increasing the levels of osmoregulatory substances, enhancing antioxidant enzyme activities, and reducing MDA accumulation, thereby enhancing plant stress tolerance. Furthermore, the consortia microbial inoculants promoted alfalfa growth performance through both direct and indirect mechanisms, including the production of IAA, siderophores, and ACC deaminase. This study demonstrates that the integrated strategy exhibits multi-level synergistic effects on both soil amelioration and plant growth promotion, potentially contributing to a positive feedback cycle of “soil improvement–microbial community optimization–plant growth enhancement–ecosystem stabilization.” This approach demonstrates substantial potential for agricultural application value and broad potential for agricultural implementation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded from https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy16030318/s1: Figure S1. Relative abundance of the soil microbial community at the class level; Figure S2. Hierarchical clustering heatmap of the bacterial abundance at the phylum level; Figure S3. Hierarchical clustering heatmap of the bacterial abundance at the class level; Table S1. Alignment similarity analysis between Bacillus pumilus 16S rRNA sequences and soil-derived OTUs/ASVs; Table S2. Alignment similarity analysis between Bacillus halotolerans 16S rRNA sequences and soil-derived OTUs/ASVs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.W., F.S., and X.C.; methodology, H.F., Y.W., F.S., and X.C.; software, W.L.; validation, Y.W.; formal analysis, W.L., H.F., Y.Z., Z.C., F.S., and X.C.; investigation, W.L.; resources, Y.Z.; data curation, Z.C.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.W., F.S., and X.C.; writing—review and editing, Y.W., F.S., and X.C.; visualization, Z.C.; supervision, Y.Z.; project administration, X.C. and F.S.; funding acquisition, Y.W., Y.Z., Z.C., and X.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Department of Science and Technology, Jilin Province, China (20230101192JC). F.J.S. was supported by Educational and Professional Leave at Georgia Gwinnett College during the course of this work.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in the NCBI database under BioProject accession PRJNA1405079.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Guo, L.; Nie, Z.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, S.; An, F.; Zhang, L.; Tóth, T.; Yang, F.; Wang, Z. Effects of different organic amendments on soil improvement, bacterial composition, and functional diversity in saline–sodic soil. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakeel, A. Potassium–sodium interactions in soil and plant under saline-sodic conditions. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2013, 176, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Shao, T.Y.; Zhou, Y.J.; Cao, Y.C.; Hu, H.Y.; Sun, Q.K.; Long, X.H.; Yue, Y.; Gao, X.M.; Rengel, Z. Effects of planting Melia azedarach L. on soil properties and microbial community in saline-alkali soil. Land Degrad. Dev. 2021, 32, 2951–2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Z.; Lin, K.; Gao, M.; Han, X.; Guan, Q.; Ji, X.; Yu, S.; Lu, L. Mitigation of Salt Stress in Rice by the Halotolerant Plant Growth-Promoting Bacterium Enterobacter asburiae D2. J. Xenobiotics 2024, 14, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.D.; Yi, S.J.; Ma, Y.C. Effects of Straw Mulching on Soil Temperature and Maize Growth in Northeast China. Teh. Vjesn.-Tech. Gaz. 2022, 29, 1805–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.J.; Liu, H.G.; Wang, T.G.; Gong, P.; Li, P.F.; Li, L.; Bai, Z.T. Deep vertical rotary tillage depths improved soil conditions and cotton yield for saline farmland in South Xinjiang. Eur. J. Agron. 2024, 156, 127166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xu, Y.J.; Gao, H.J.; Mao, J.D.; Chu, W.Y.; Thompson, M.L. Biochemical stabilization of soil organic matter in straw-amended, anaerobic and aerobic soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 625, 1065–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Li, C.; Yao, L.; Cui, H.Y.; Tian, Y.J.; Sun, X.; Yu, T.H.; He, J.Q.; Wang, S. Effects of dynamic nitrogen application on rice yield and quality under straw returning conditions. Environ. Res. 2023, 243, 117857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.C.; Zhang, R.Y.; Wang, R.J.; Wu, D.W.; Dai, S.F.; Wang, Z.B.; Chen, T.; Mao, H.M.; Li, Q. Responses of nutrient utilization, rumen fermentation and microorganisms to different roughage of dairy buffaloes. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucciarelli, B.; Xu, Z.; Ao, S.; Cao, Y.; Monteros, M.J.; Topp, C.N.; Samac, D.A. Phenotyping seedlings for selection of root system architecture in alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). Plant Methods 2021, 17, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Wu, J.; Ru, L.; Chang, H. Characteristics of soil nitrogen and nitrogen cycling microbial communities in different alfalfa planting years. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2023, 69, 3087–3101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.P.; Shi, W.J. Cotton/halophytes intercropping decreases salt accumulation and improves soil physicochemical properties and crop productivity in saline-alkali soils under mulched drip irrigation: A three-year field experiment. Field Crops Res. 2021, 262, 108027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, T.Y.; Qian, R.; Guo, Z.C.; Huang, X.J.; Peng, X.H. Soil pore structure shaped compositions and structures of soil microbial community during 13 C-labelled maize straw decomposition. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 204, 105746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, D.R.; Rathore, A.P.; Sharma, S. Effect of halotolerant plant growth promoting rhizobacteria inoculation on soil microbial community structure and nutrients. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2020, 150, 103461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, S.; Naqqash, T.; Nawaz, M.S.; Laraib, I.; Siddique, M.J.; Zia, R.; Mirza, M.S.; Imran, A. Rhizosphere Engineering with Plant Growth-Promoting Microorganisms for Agriculture and Ecological Sustainability. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 617157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.K.; Zhang, C.C.; Nai, G.J.; Ma, L.; Lai, Y.; Pu, Z.H.; Ma, S.Y.; Li, S. Microbial Inoculant GB03 Increased the Yield and Quality of Grape Fruit Under Salt-Alkali Stress by Changing Rhizosphere Microbial Communities. Foods 2025, 14, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.Y.; Yu, X.F.; Gao, J.L.; Qu, J.W.; Borjigin, Q.; Meng, T.T.; Li, D.B. Using Klebsiella sp. and Pseudomonas sp. to Study the Mechanism of Improving Maize Seedling Growth Under Saline Stress. Plants 2025, 14, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J. Screening of Functional Strains Resistant to Salt-Alkali and Their Effects on the Growth of Leymus chinensis and Soil Environment. Master’s Thesis, Jilin Agricultural University, Changchun, China, 1 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dobrzynski, J.; Wróbel, B.; Górska, E.B. Cellulolytic Properties of a Potentially Lignocellulose-Degrading Bacillus sp. 8E1A Strain Isolated from Bulk Soil. Agronomy 2022, 12, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.F.R.; Sousa, E.; Resende, D. A Practical Toolkit for the Detection, Isolation, Quantification, and Characterization of Siderophores and Metallophores in Microorganisms. Acs Omega 2024, 9, 26863–26877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yin, P.L.; Ling, J.H.; Peng, G.; Kai, Y.Y.; Lin, J.; Xiang, Z. Identification and growth promotion analysis of a salt-alkali tolerant endophyte strain isolated from Lespedeza daurica. Microbiol. China 2023, 50, 218–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, R.; Yao, F.; Yang, Y.; Hou, K.; Feng, D.; Wu, W. Screening and Plant Growth Promoting of Grow-promoting Bacteria in Rhizosphere Bacteria of Angelica dahurica var. formosana. Biotechnol. Bull. 2022, 38, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrose, D.M.; Glick, B.R. Methods for isolating and characterizing ACC deaminase-containing plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Physiol. Plant. 2003, 118, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.H.; Gong, P.B.; Chen, C.L. Plant Physiological and Biochemical Experimental Techniques. In Principles and Techniques of Plant Physiological Biochemical Experiment, 1st ed.; Li, H.H., Su, Q., Zhao, S.J., Zhang, W.H., Eds.; Higher Education Press: Beijing, China, 2000; Volume 2, pp. 164–261. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.R.; Tian, K. Experimental Tutorial of Soil Science, 1st ed.; China Forestry Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2011; pp. 56–88. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.H.; Lei, Z.C.; Luo, X.F.; Wang, D.M.; Li, L.; Li, A. Biological Degradation and Transformation Characteristics of Total Petroleum Hydrocarbons by Oil Degradation Bacteria Adsorbed on Modified Straw. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 10921–10928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feller, C.; Blanchart, E.; Bernoux, M.; Lal, R.; Manlay, R. Soil fertility concepts over the past two centuries: The importance attributed to soil organic matter in developed and developing countries. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2012, 58, S3–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mtambanengwe, F.; Mapfumo, P. Organic matter management as an underlying cause for soil fertility gradients on smallholder farms in Zimbabwe. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosystems 2005, 73, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.Q.; Zhao, Y.; Fan, Y.Y.; Lu, Q.A.; Li, M.X.; Wei, Q.B.; Zhao, Y.; Cao, Z.Y.; Wei, Z.M. Impact of phosphate-solubilizing bacteria inoculation methods on phosphorus transformation and long-term utilization in composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 241, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.W.; Zhang, X.L.; Gong, S.W.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Y.W.; Yang, X.D.; Niu, W.Q. Micro/nanobubble-oxygenated drip irrigation under excessive irrigation conditions improves tomato yield in mildly saline soils by regulating rhizosphere and root endophytic bacterial communities. Soil Tillage Res. 2025, 253, 106635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Yue, H.; Tan, R.; Ding, Z.; Chen, G.; Zhang, S.; Li, Z.; Proshad, R.; Cheng, X.; Zhao, Z. Remediation effects of humic acid and hydroxyapatite on cadmium-contaminated alkaline wheat soil and its microbial community response: A field trial. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.Y.; Xu, L.N.; Yuan, Y.F.; Guo, X.; Li, W.; Guo, S.X. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi alter microbiome structure of rhizosphere soil to enhance Festuca elata tolerance to Cd. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 204, 105735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupwayi, N.Z.; Hao, X.Y.; Gorzelak, M.A. Divergent responses of the native grassland soil microbiome to heavy grazing between spring and fall. Microbiology 2024, 170, 001517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, N.; Song, X.S.; Song, R.Q.; Yin, D.C.; Deng, X. Diversity and structure of the microbial community in rhizosphere soil of Fritillaria ussuriensis at different health levels. PeerJ 2022, 10, e12778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.L.; Hu, X.Y.; Liu, X.W.; Zhang, P.L.; Yang, S.C.; Xia, F.Q. Bioorganic Fertilizer Can Improve Potato Yield by Replacing Fertilizer with Isonitrogenous Content to Improve Microbial Community Composition. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.Z.; Wang, S.Y.; Zhang, M.L.; Zeng, L.; Zhang, L.Y.; Huang, S.Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhou, W.; Ai, C. Nitrogen Application and Rhizosphere Effect Exert Opposite Effects on Key Straw-Decomposing Microorganisms in Straw-Amended Soil. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.J.; Zhou, S.X.; Xiao, Y.P.; Zhang, T.; Tao, X.Y.; Shi, K.Z.; Lu, Y.X.; Yang, Y.Q.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, T. Exploring the microbial ecosystem of Berchemia polyphylla var. leioclada: A comprehensive analysis of endophytes and rhizospheric soil microorganisms. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1338956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.J.; Peng, W.X.; Du, H.; Song, T.Q.; Zeng, F.P.; Wang, F. Effect of Different Grain for Green Approaches on Soil Bacterial Community in a Karst Region. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 577242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.L.; Zheng, Z.K.; Ma, L.Y.; Wang, H.M.; Wang, X.J.; Zhu, F.; Xue, S.G.; Srivastava, P.; Sapsford, D.J. Polymetallic contamination drives indigenous microbial community assembly dominated by stochastic processes at Pb-Zn smelting sites. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 947, 174575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, D.D.; Jiang, F.F.; Lin, W.H.; Tian, Z.; Wu, N.N.; Feng, X.X.; Chen, T.; Nan, Z.B. Effects of Drought on the Growth of Lespedeza davurica through the Alteration of Soil Microbial Communities and Nutrient Availability. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, U.B.; Malviya, D.; Singh, S.; Singh, P.; Ghatak, A.; Imran, M.; Rai, J.P.; Singh, R.K.; Manna, M.C.; Sharma, A.K.; et al. Salt-Tolerant Compatible Microbial Inoculants Modulate Physio-Biochemical Responses Enhance Plant Growth, Zn Biofortification and Yield of Wheat Grown in Saline-Sodic Soil. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. Effects of Direct Straw Returning in Winter on Soil Properties and Rice Growth. Master’s Thesis, Tianjin University, Tianjin, China, 1 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tejada, M.; Gonzalez, J.L. Beet vinasse applied to wheat under dryland conditions affects soil properties and yield. Eur. J. Agron. 2005, 23, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, O.S.; Fernandes, A.S.; Tupy, S.M.; Ferreira, T.G.; Almeida, L.N.; Creevey, C.J.; Santana, M.F. Insights into plant interactions and the biogeochemical role of the globally widespread Acidobacteriota phylum. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2024, 192, 109369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.Q.; Kang, P.; Qu, X.; Zhang, H.X.; Li, X.R. Response of the soil bacterial community to seasonal variations and land reclamation in a desert grassland. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 165, 112227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.M.; Qi, L.H.; Zhou, W.Q.; Yang, J.J.; Zhang, X.G.; Chen, F.Y.; Zhu, Y.L.; Guan, C.F.; Yang, S.H. The effect and mechanism of exogenous P on the efficiency of microbial-assisted alfalfa remediation of Cu-contaminated soil. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 115503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.Y.; Li, J.F.; Gao, L.H.; Tian, Y.Q. Comprehensive evaluation of effects of various carbon-rich amendments on overall soil quality and crop productivity in degraded soils. Geoderma 2023, 436, 116529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, B.W.; Li, J.H.; Koch, B.J.; Blazewicz, S.J.; Dijkstra, P.; Hayer, M.; Hofmockel, K.S.; Liu, X.J.A.; Mau, R.L.; Morrissey, E.M.; et al. Nutrients cause consolidation of soil carbon flux to small proportion of bacterial community. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.Y.; Wei, H.W.; Qi, D.Q.; Li, W.W.; Dong, Y.; Duan, F.A.; Ni, S.Q. Continuous planting American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius L.) caused soil acidification and bacterial and fungal communities’ changes. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, W.J.; Liu, Y.E.; Hu, J.; Luo, Z.F.; Zhang, J.X.; Wang, Y. Effects of Years of Operation of Photovoltaic Panels on the Composition and Diversity of Soil Bacterial Communities in Rocky Desertification Areas. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.L.; Chu, Y.N.; Jia, Y.H.; Yue, H.Y.; Han, Z.H.; Wang, Y. Changes to bacterial communities and soil metabolites in an apple orchard as a legacy effect of different intercropping plants and soil management practices. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 956840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.