Abstract

Soil salinization is a major threat to agricultural sustainability. Poly-gamma-glutamic acid (γ-PGA), a biopolymer produced by microbial fermentation, has received attention as a biostimulant due to its positive effects on crop performance. However, the function of γ-PGA in crop salt stress tolerance and its effect on the rhizosphere are unclear. This study explores the effects of γ-PGA application on rhizosphere soil nutrients and the soil–physical environment and examines the salt tolerance response of maize seedlings grown in saline–alkali soil under such an application regime. The results show a significant promotion of maize seedling growth and of nutrient accumulation with γ-PGA application under salt stress; plant dry weight, stem diameter, and plant height increased 121%, 39.5%, 18.4%, respectively, and shoot accumulation of nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and carbon increased by 1.38, 2.11, 1.50, and 1.36 times, respectively, under an optimal-concentration γ-PGA treatment (5.34 mg kg−1 (12 kg ha−1)) compared with the control. γ-PGA treatment significantly decreased rhizospheric pH and soil electrical conductivity and significantly increased nutrient availability in the rhizosphere, especially available nitrogen (AN) and available potassium (AK). Compared with the control, AN, available phosphorus (AP), and AK increased by 13.9%, 7.70%, and 17.7%, respectively, under an optimal concentration treatment with γ-PGA. γ-PGA application also significantly increased the activities of urease, acid phosphatase, alkaline phosphatase, dehydrogenase, and cellulose in rhizosphere soil by 35.5–39.3%, 35.4–39.3%, 5.59–8.85%, 18.9–19.8%, and 19.2–47.0%, respectively. γ-PGA application significantly decreased Na+ concentration and increased K+ concentration in shoots, resulting in a lowering of the Na+/K+ ratio by 30.5% and an increase in soluble sugar and soluble protein contents. Therefore, rhizosphere application of water-soluble and biodegradable γ-PGA facilitates the creation of an optimized rhizospheric environment for maize seedling and overcomes osmotic and ionic stresses, offering possibilities for future use in drip-irrigation systems in the cultivation of crops on saline-alkali land.

1. Introduction

Currently, approximately 1 billion ha of the global land surface are affected by salinisation, representing roughly 7% of the Earth’s total land area [1]. The majority of these saline-affected regions originate from natural geological and geochemical processes, such as coastal saline-alkali land, whereas secondary salinization, primarily induced by anthropogenic activities such as improper irrigation and inadequate drainage, impacts approximately 30% of the world’s irrigated croplands [2]. As the global population expands and food demand increases, the need to reduce soil-salinity stress and strengthen crop salt resistance while securing crop yields has grown increasingly critical [3]. The most significant grain crop in China is corn, which is not well-adapted to saline soils and readily suffers reduced nutrient absorption, stunted growth and development, and decreased yield [4]. When the salt–alkali content in soil exceeds 0.2–0.25%, corn becomes highly susceptible to damage [5]. One important component of this is osmotic stress, which impairs root water uptake and induces ionic toxicities, compromising crop yield and nutrient absorption more generally [6]. Adaptive strategies to such stresses include the excretion or sequestration of toxic ions, and the enhanced biosynthesis of compatible solutes that serve as osmotic regulators [7]. The response of maize to salt stress is multi-faceted and complex, primarily driven by osmotic effects and ionic toxicity. These primary effects manifest as physiological drought due to a decrease in soil water potential, and the excess absorption and accumulation of Na+, and to a lesser extent Cl−, ions by the roots [8]. Subsequently, these initial stresses trigger a range of secondary effects, including nutrient imbalances (e.g., a suppression of tissue K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+), reduced photo-synthetic efficiency, growth inhibition, and ultimately, yield losses [9]. Therefore, it is essential to carefully adjust fertilization protocols on saline soils in order to reduce the harm that salt causes to maize.

Physical soil properties play a crucial role in regulating soil moisture, fertility, heat flow and storage, as well as gas generation and diffusion. They also affect numerous chemical and biological processes in soil. By contrast, soil nutrient status directly influences the growth and distribution of plants [10]. In saline–alkali soils, soil salinity significantly reduces the availability of both nutrients and water [10,11]. Overall, osmotic and ionic stress inhibit primary metabolism, disrupt cell membrane integrity, and lead to inhibition of photosynthesis [11]. The regulation of ion transporters to exclude toxic Na+/Cl− and retain essential K+ is important, in addition to the osmotic aspects mentioned above [12]. Maintaining high sufficient levels of tissue K+ is regarded as critical to salt tolerance [13,14]. Identifying methods or chemical agents that can amend the physical, chemical, and biological properties of soil, in particular rhizosphere soil, to create a suitable environment for root growth and simultaneously enhance plant salt tolerance, is therefore an important goal, in order to ensure sustainable grain production on saline-alkali soils.

γ-polyglutamic acid (γ-PGA) is a water-soluble and biodegradable polyamino acid composed of L-/D-glutamic acid (L-/D-Glu) monomers linked via γ-amide bonds, which is biosynthesised by Bacillus subtilis [15]. Endowed with outstanding chelating capacity, inherent biodegradability, and eco-friendliness, γ-PGA exhibits considerable application potential and broad prospects in the agricultural sector. Previous studies have shown that γ-PGA and other polyamino acids can enhance the nutrient absorption capacity of plants and promote the growth and yield of food crops in conventional farmland soil and economic crops in problematic soils (including saline–alkali soils) [16]. However, there are very few reports on the relationship between γ-PGA and nutrient contents and enzyme activities in the rhizosphere soil of saline-alkali land or on the effects of γ-PGA on the salt tolerance of major cereal crops such as maize. As soil enzyme activity varies with environmental factors, γ-PGA may affect rhizosphere soil nutrient availability by affecting rhizosphere enzyme activity, thus affecting crop growth. For example, soil acid phosphatase can release phosphate by hydrolysing phosphate bonds in phosphate groups of organic molecules, and urease promotes the release of ammonium nitrogen (NH4+) from urea, thus alleviating salt stress in maize [17]. As exposited above, the primary mechanisms underlying plant salt tolerance involve the synergistic regulation of ionic homeostasis (e.g., by maintaining a low Na+/K+ ratio) and osmotic adjustment (via accumulating soluble sugars or proline), which, together, can alleviate the dual stresses of ion toxicity and water deficit [18]. Previous studies have pointed to the ability of exogenous γ-PGA to enhance soil nutrient availability and promote crop growth [19]. Additionally, some biopolymers, such as chitosan and alginate, can also promote plant growth and even enhance a crop’s ability to resist abiotic stress [20]. Therefore, the influence of root zone application of γ-PGA on plant salt-tolerance pathways may include two aspects: (1) regulation of the physical, chemical, and biological properties of the soil (especially the rhizosphere soil), and (2) plant physiological regulation, such as through ion balance and osmotic regulation [21].

Soil salinity severely constrains plant growth and substantially impairs crop productivity [22]. Therefore, enhancing crop salt tolerance and constructing a nutrient-rich, functional rhizosphere represent critical strategies for improving crop production on saline soils. Of special concern is the seedling stage in crops such as maize, during which higher salt sensitivity is common [23]. The present study focuses on the effects of γ-PGA, at different application doses, on the health status of rhizosphere soil under salt stress, the nutrient absorption of maize seedlings, and ion balance as well as osmotic regulation, with the goal of furthering our understanding of salt-tolerance mechanisms and mitigation strategies in maize and to provide theoretical support for the promotion of technologies that create a suitable rhizospheric environment in saline-alkali soils. Based on the above background and research gaps, we propose the central hypothesis: Exogenous rhizosphere application of γ-PGA enhances salt tolerance and growth in maize seedlings under saline-alkali stress through two synergistic pathways: (1) improving rhizospheric soil properties to elevate soil fertility and nutrient bioavailability; (2) mitigating salt-induced osmotic and ionic stresses by maintaining ionic balance and promoting osmotic adjustment in maize.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials and Maize Cultivation Conditions

The pot culture experiment was conducted in the greenhouse of the Nanjing Institute of Soil Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS). The dimensions of the pots used were as follows: 20 cm long, 6 cm wide, and 25 cm high. The experimental soil used was collected from a 0–20 cm depth in a maize field located in typical coastal zone of Dafeng District, Yancheng City, Jiangsu Province, China (33°01′40″ N, 120°81′88″ E). This region directly adjoins the Yellow Sea, a major marginal sea bordering mainland of eastern China. Among China’s coastal regions, Jiangsu Province has been experiencing an increasing severity of soil salinization in recent years [24]. The formation of saline soils is primarily attributed to the accumulation of soluble salts originating from rainfall, rock weathering, wind deposition, as well as anthropogenic activities. The soil was air-dried and, after removal of roots and gravel, was passed through a 2.0 mm sieve and mixed. Specifically, no sterilization or microbial inactivation treatments (e.g., autoclaving, gamma-irradiation) were applied during soil preparation, ensuring the retention of the native microbiome from the original agricultural saline field. The soil texture was saline–alkali soil, and the major properties were: soil electrical conductivity (EC) 0.51 mS cm−1; pH 8.47; total nitrogen (TN) 1.02 g kg−1; available phosphorus (AP) 45.8 mg kg−1; available potassium (AK) 66.3 mg kg−1; soil organic carbon (SOC) 8.81 g kg−1. The maize variety Suyu 10 is a new maize hybrid bred by the Agricultural Science and Technology Institute of Yanjing District of Jiangsu Province. γ-PGA was purchased from Hanxing Biotechnology (Nanjing) Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China). The γ-PGA products used had an average molecular weight of 100–500 kDa and a purity of 15% (w/w). As the purity of such products currently available on the market varies considerably, the γ-PGA concentrations used in the experiments were converted and presented based on the pure concentration (100% w/w).

2.2. Experimental Design

Each pot contained 4 kg of dry soil. Fertilizers were thoroughly mixed in the soil at the equivalent of 42.8 mg N kg−1 (210 kg ha−1), 3.96 mg P2O5 kg−1 (75 kg ha−1), and 31.2 mg K2O kg−1 (135 kg ha−1). Four γ-PGA treatments were prepared: 0 mg kg−1 (CK, 0 kg ha−1), a low concentration of 2.67 mg kg−1 (6 kg ha−1), a medium concentration of 5.34 mg kg−1 (12 kg ha−1), and a high concentration of 10.7 mg kg−1 (24 kg ha−1) [25]. Each process was repeated three times. Two disinfected and germinated maize seeds were disinfected and then sown in each pot. On the day of sowing, γ-PGA was dissolved in sterile distilled water and was applied by a syringe uniformly onto the soil surface in a circle approximately 1 cm from the base of each germinated seeds, ensuring the solution infiltrated the rhizosphere soil without direct contact with the seeds. The irrigation water used was sterile distilled water, with a pH of 6.8–7.0, EC < 0.01 mS cm−1, and no detectable Na+, K+, or other major ions (determined via ICP-OES). The irrigation was applied on a daily basis to maintain 60% of the field water holding capacity to maintain the normal growth of maize seedlings, using distilled water [26]. The weeds from each pot were eliminated manually.

2.3. Soil and Plant Sampling

Soil and plant samples were obtained on day 35 after sowing. Soil samples with a depth of 20 cm from the soil surface (30–50 g) were taken for subsequent testing. Each soil sample was divided into two parts, one sample was used to determine soil enzyme activity, and the other part was used to determine soil physical and chemical properties. The above ground biomass was collected by severing at the base of the corn stalk. The root was manually separated from the potting soil and washed clean with distilled water.

2.4. Soil Physicochemical Property Determination

Soil pH was measured in a 1:2.5 soil-water suspension using a pH meter (PHS-3C, INESA Scientific, Shanghai, China). The soil electrical conductivity (EC) was measured with a soil and water suspension of 1:5 using a glass electrode (DDS-11A, Shanghai, China). Cation exchange capacity (CEC) was determined by the EDTA-NH4OAc exchange method [27] SOC was determined by K2Cr2O7-H2SO4 digestion [28]. TN was analysed using the Kjeldahl digestion procedure [29]. Available nitrogen (AN) was determined using the alkaline dissolution diffusion method [30]. AP was determined by extraction with NaHCO3 [31]. The microwave-accelerated reaction system (CEM, Matthews, NC, USA) was used to digest soil samples with HNO3-H2O2. Total P and K concentrations in the digested solutions were then determined by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICPOES, OPTIMA 3300 DV, Perkin–Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.5. Soil Enzyme Activity Determination

Soil enzymatic activities, including the activities of cellulose and urease related to the C and N cycles, acid alkaline phosphatase activities related to the P cycle, and dehydrogenase activity, representing overall soil microbial activity, were determined [32]. In detail, soil urease activity was determined with the phenol–hypochlorite colorimetric method [33]. Cellulose activity was assayed with the method of 3, 5 dinitrosalicylic acid colorimetry [34]. Measurements of acidic and alkaline phosphatase activities were carried out using p-nitrophenyl phosphate disodium salt (PNPP) as the substrate, and the measurement of dehydrogenase activity was carried out using 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) as the substrate, according to the Tabatabai method [33].

2.6. Soil Quality Evaluation

The soil quality index (SQI) was used to evaluate soil quality under γ-PGA amendment, and each soil physicochemical property was firstly converted to a value ranging from 0 to 1, using one of the equations below. Soil properties were divided into two groups, as follows: if a parameter increased with soil quality, then a score of “more is better” was used and Equation (1) was applied (e.g., SOC). Otherwise, a score of “less is better” was used and Equation (2) was applied (e.g., EC, in our case) [35]:

where Li is the linear score of parameters from 0 to 1; x, Xmax and Xmin denote the measured value, maximum, and minimum of the index, respectively.

Then, the SQI was estimated with the SQI-area approach, which involves evaluating the radar diagram area generated by all soil indices [35]:

where n is the sum number of indices.

2.7. Measurement of Plant Growth Attributes

After the plants were rinsed with deionized water during sampling, surface water was thoroughly removed with absorbent paper. A calibrated meter rod was used to measure plant height. Stem thickness was measured with vernier calipers. The treated plant samples were divided into shoot and root systems and weighed for fresh weight, respectively. Each part of the plant was subjected to 105 °C for 30 min to stop all enzyme activity, then dried at 70 °C for 12 h to constant weight, and then to obtain the dry weight was recorded [36].

2.8. Elemental Ion Contents in Maize Plants

Dry shoot samples were ground and sieved through a 0.25 mm mesh. A 1 g aliquot of the homogenized dry sample was digested in a mixed solution of H2SO4 and H2O2 at a 5:2, volume ratio, followed by TN determination via the Kjeldahl method [37]. A 1-g aliquot of the homogenised dry sample was digested with a mixture of HNO3 and H2O2 (v/v 3:1) using a microwave-accelerated reaction system (CEM, Matthews, NC, USA) following a two-step program (ramped to 120 °C for 5 min, then 180 °C for 15–20 min), and the concentrations of total P, K, and Na in the digested solutions were determined by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES, OPTIMA 3300 DV, Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) [38].

2.9. Soluble Sugar and Soluble Protein Contents

Plant soluble protein content was evaluated using the Coomassie brilliant blue G-250 dyeing method [39]. Briefly, an aliquot of 0.1 mL of the diluted sample extract was mixed with 5.0 mL of the G-250 reagent. Following a 2–5 min incubation at room temperature, the absorbance was measured at 595 nm. Protein concentration was quantified against a standard curve prepared with bovine serum albumin (BSA). Plant soluble sugar content was measured with the Anthrone colorimetric method [40]. Briefly, 0.1 g of ground maize shoot samples were extracted with 5 mL of 80% ethanol in a 80 °C water bath for 30 min. After centrifugation at 8000× g for 10 min, the supernatant was collected. A 0.5 mL aliquot of the supernatant was mixed with 3 mL of anthrone reagent, and the mixture was heated in a boiling water bath for 10 min. After cooling to room temperature, the absorbance was measured at 620 nm. The soluble sugar concentration was calculated based on a standard curve prepared with glucose.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

The assumptions of the normality and homogeneity of variances were evaluated for each dataset. For this purpose, statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS Statistics software (Version 21.0, SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA), then the Shapiro–Wilk test was applied to the model residuals to assess normality, and Levene’s test was performed to verify the homogeneity of variances. Only the features that met both criteria (p > 0.05 in both tests) were considered valid for the analyses of variance (ANOVA). The Duncan test was used to determine significant differences among the treatments, values are the means ± SD (n = 3), and different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among the four treatments. All the figures were drawn by Origin 2021.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of γ-PGA on Physicochemical Properties of Rhizosphere Soil

The physicochemical properties of rhizosphere soil showed significant improvement under the γ-PGA treatment (Table 1) compared with those in the CK group. γ-PGA application significantly decreased the pH value and EC of the rhizosphere compared with CK, i.e., pH in 2.67 mg kg−1, 5.34 mg kg−1 and 10.7 mg kg−1 treatments decreased by 0.67%, 0.88%, and 1.08%, respectively (Table 1), while EC decreased by 2.47%, 6.01%, and 5.91%, respectively (Table 1). Compared with the control treatment, the γ-PGA treatment increased the CEC and SOC of the rhizosphere soil, but the difference was not significant. γ-PGA treatments significantly increased the TN and TP in the rhizosphere soil by 5.29% to 8.13% and 1.26% to 2.56%, respectively (Table 1). Compared with CK, available nitrogen (AN), available phosphorus (AP), and available potassium (AK) contents in the rhizosphere soil demonstrated varying degrees of improvement among all γ-PGA treatments. Moreover, all γ-PGA treatments for AN, medium concentration for AP, as well as low concentration and medium concentration for AK exhibited significant differences compared to the control. Among them, medium concentration treatment significantly increased AN, AP, and AK, compared with CK by 13.9%, 7.70%, and 17.7%, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Properties of rhizosphere soil in each treatment.

3.2. Effects of γ-PGA Enzyme Activity in Rhizosphere Soil

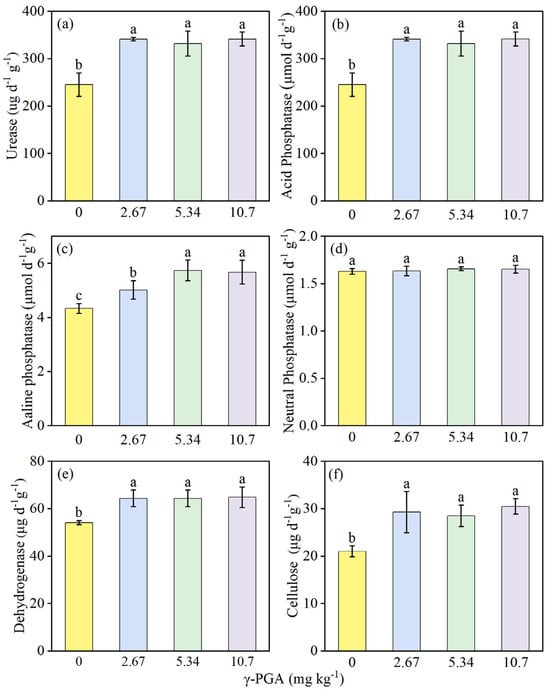

The effect of various γ-PGA application levels on rhizosphere soil enzyme activity indices (urease, acid phosphatase, alkaline phosphatase, dehydrogenase, and cellulose activity) showed significant promotional effects (Figure 1). Except for neutral phosphatase activity, γ-PGA treatment produced significant increase compared with CK treatment (Figure 1d). γ-PGA application increased the activities of urease, acid phosphatase, alkaline phosphatase, dehydrogenase and cellulose detected in rhizosphere soil, by 35.5–39.3%, 35.4–39.3%, 5.59–8.85%, 18.9–19.8%, and 19.2–47.0%, respectively (Figure 1a,b,e,f and Figure 2a).

Figure 1.

Urease activity (a), acid phosphatase activity (b), alkaline phosphatase activity (c), neutral phosphatase activity (d), dehydrogenase activity (e), and cellulose activity (f) in soil under various γ-PGA application levels. Values are means ± SD, n = 3. The Duncan’s test was used to determine significant differences among the treatments. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among the four treatments following analysis of variance (ANOVA), p < 0.05. 0 mg kg−1: CK, 0 kg ha−1; 2.67 mg kg−1: low concentration, 6 kg ha−1; 5.34 mg kg−1: medium concentration, 12 kg ha−1; 10.7 mg kg−1: high concentration, 24 kg ha−1. Rhizosphere soil samples were obtained on day 35 after maize seed sowing.

3.3. Effects of γ-PGA on the Rhizosphere Soil Quality Index

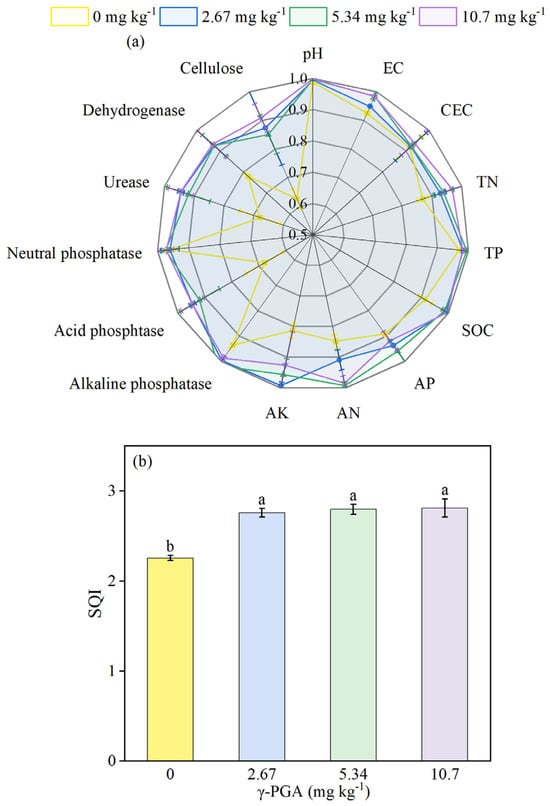

Figure 2a shows the general improvement of the rhizosphere soil properties by γ-PGA application compared with CK, using a method of re-standardising all indicators. Among all indicators related to soil quality, the most significant improvements resulting from γ-PGA application were in rhizosphere soil enzyme activities and available nutrients, and particularly the significant increase in urease, acid phosphatase, dehydrogenase, and cellulose activity (Figure 1a,b,e,f and Figure 2a), AN, and AK (Figure 2a, Table 1). The significant reduction of rhizosphere pH value and EC resulting from γ-PGA application also contributed to the improvement of the rhizosphere environment (Figure 2a, Table 1). As an indicator of quantitative assessment of soil quality, SQI was included in our study, to characterise the quantitative effect of γ-PGA addition on rhizosphere soil quality. γ-PGA application overall significantly increased the SQI in the low concentration, medium concentration, and high concentration, by 22.2%, 23.5%, and 24.1%, respectively (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Radar graph for the soil indicator scores under various γ-PGA application levels (a), and overall soil quality index (SQI) in response to various γ-PGA application levels (b). EC: electrical conductivity; CEC: cation exchange capacity; TN: total nitrogen; TP: total phosphorus; SOC: soil organic carbon; AN: available nitrogen; AP: available phosphorus; AK: available potassium. Values are means ± SD, n = 3. The Duncan’s test was used to determine significant differences among the treatments. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among the four treatments, following analysis of variance (ANOVA), p < 0.05. 0 mg kg−1: CK, 0 kg ha−1; 2.67 mg kg−1: low concentration, 6 kg ha−1; 5.34 mg kg−1: medium concentration, 12 kg ha−1; 10.7 mg kg−1: high concentration, 24 kg ha−1. Rhizosphere soil samples were obtained on day 35 after maize-seed sowing.

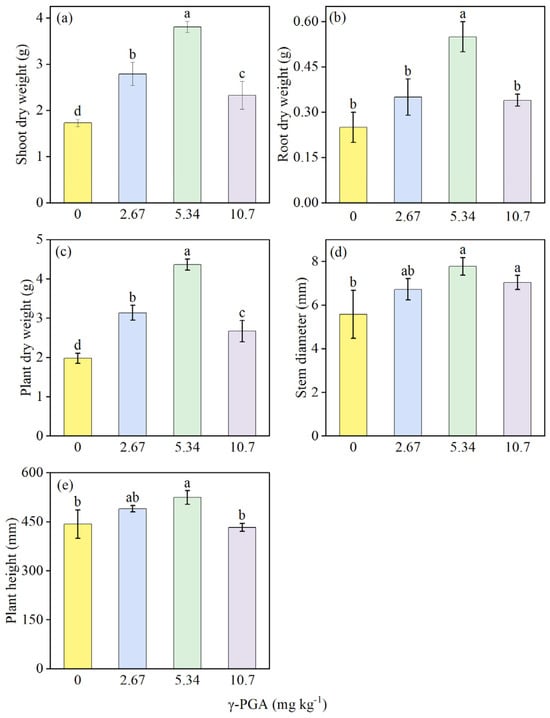

3.4. Effects of γ-PGA on Shoot and Root Growth

Different γ-PGA dosages showed various improvement ranges compared to CK treatment under salinity stress (Figure 3). All parameters tested showed an increasing trend, followed by a decrease, as the γ-PGA dose increased. Among all treatments, medium concentration demonstrated clear advantages and all growth indicators were improved significantly when compared to CK. Shoot dry weight, root dry weight, plant dry weight, steam diameter, and plant height significantly increased, by 120% (Figure 3a), 121% (Figure 3b), 121% (Figure 3c), 39.5% (Figure 3d), and 18.4% (Figure 3e), respectively, under the medium concentration treatment. However, although the high-concentration group showed significant increases compared to CK in shoot dry weight, plant dry weight and stem diameter, while root dry weight increase was not significant, and a slight inhibitory effect was observed on the height of maize plants in the seedling stage (Figure 3e).

Figure 3.

Shoot dry weight (a) root dry weight (b) plant dry weight (c), stem diameter (d) and plant height (e) under various γ-PGA application levels. Values are means ± SD, n = 3. The Duncan’s test was used to determine significant differences among the treatments. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among the four treatments, following analysis of variance (ANOVA), p < 0.05. 0 mg kg−1: CK, 0 kg ha−1; 2.67 mg kg−1: low concentration, 6 kg ha−1; 5.34 mg kg−1: medium concentration, 12 kg ha−1; 10.7 mg kg−1: high concentration, 24 kg ha−1. Plant samples were obtained on day 35 after maize seed sowing.

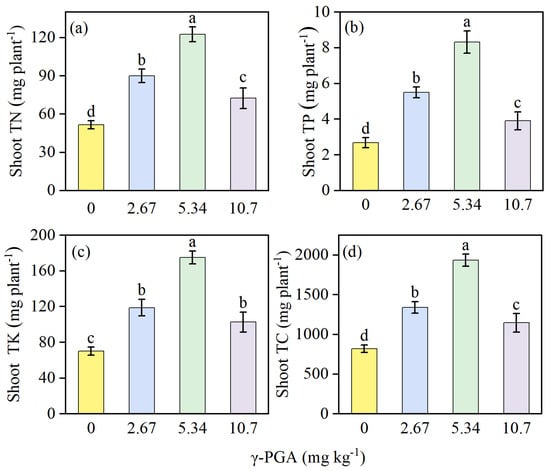

3.5. Effects of γ-PGA on Shoot Nutrient Accumulation

Nutrient accumulation in shoots showed significant improvement under all γ-PGA treatments (Figure 4) compared with the CK group. For shoot, TN, TP, TK, and TC, the treatments showed a trend of 5.34 mg kg−1 > 2.67 mg kg−1 > 10.7 mg kg−1 > CK. The 2.67 mg kg−1 treatment significantly increased the accumulation of TN, TP, TK, and TC, by 1.38 (Figure 4a), 2.11 (Figure 4b), 1.50 (Figure 4c), and 1.36 (Figure 4d) times, respectively, compared with the CK treatment.

Figure 4.

The shoot TN (a), TP (b), TK (c) and the TC (d) under various γ-PGA application levels. TN, total nitrogen; TP, total phosphorus; TK, total potassium; TC, total carbon. Values are means ± SD, n = 3. The Duncan’s test was used to determine significant differences among the treatments. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among the four treatments, following analysis of variance (ANOVA), p < 0.05. 0 mg kg−1: CK, 0 kg ha−1; 2.67 mg kg−1: low concentration, 6 kg ha−1; 5.34 mg kg−1: medium concentration, 12 kg ha−1; 10.7 mg kg−1: high concentration, 24 kg ha−1. Plant samples were obtained on day 35 after maize seed sowing.

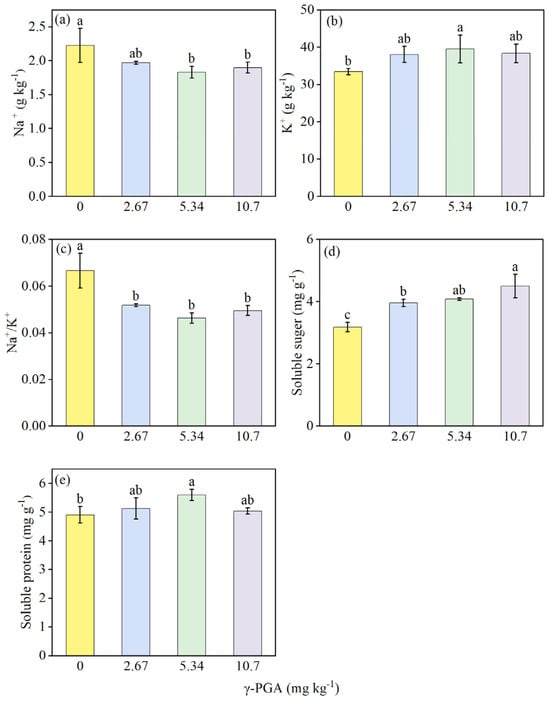

3.6. Effects of γ-PGA on the Accumulation of Shoot Osmotic Substances

The addition of γ-PGA reduced the Na+ level (Figure 5a) while increasing K+ accumulation (Figure 5b), resulting in a significant decrease in the Na+/K+ ratio (Figure 5c) compared with the CK treatment. The medium concentration treatment showed the maximum decrease in Na+ concentration (by 17.8%) and increase in the K+ concentration (by 18.3%) in shoots, resulting in a lowering of the Na+/K+ ratio by 30.5% (Figure 5c) compared with the CK treatment. γ-PGA application increased soluble sugar content (Figure 5d) and soluble protein content, by 24.3–41.3% and 2.71–14.1%, respectively (Figure 5e), and medium concentration had the most significant effect on soluble protein content among all treatments (Figure 5e).

Figure 5.

Shoot Na+ (a), K+ (b), Na+/K+ (c), soluble sugar (d), and soluble protein (e) under various γ-PGA application levels. Values are means ± SD, n = 3. The Duncan’s test was used to determine significant differences among the treatments. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among the four treatments, following analysis of variance (ANOVA), p < 0.05. 0 mg kg−1: CK, 0 kg ha−1; 2.67 mg kg−1: low concentration, 6 kg ha−1; 5.34 mg kg−1: medium concentration, 12 kg ha−1; 10.7 mg kg−1: high concentration, 24 kg ha−1. Plant samples were obtained on day 35 after maize seed sowing.

4. Discussion

4.1. Exogenous Application of γ-PGA Enhances Maize Tolerance to Salt Stress

The remediation of saline–alkali soil is an urgent and complex challenge that requires integrated approaches to address both immediate salinity stress and long-term soil health. Traditional methods, such as organic amendment application, leaching, and chemical amendments, have been widely used but often suffer from limitations, including high water and resource consumption, slow response times, and potential secondary pollution [41,42]. By contrast, rhizosphere microzone modification offers a targeted and efficient strategy by focusing on the immediate optimization of the root environment, where plant–microbe–soil interactions are most critical [43].

Rhizosphere modification presents an environmentally friendly and efficient strategy to mitigate plant salt stress. This approach encompasses the application of organic amendments, plan-growth-promoting bacteria, and microbial inoculants, often synergistically combined with drip irrigation technology. Such integrated methods not only alleviate the physiological challenges faced by plants in saline environments but also foster ecological balance and sustainable agricultural development [44]. The key advantage of rhizosphere regulation lies in its superior precision and efficiency. Unlike amendments targeting all soil profiles, which require large quantities of water, organic matter, or physical and chemical amendments, the application of γ-PGA directly altered the physicochemical and biological properties of the root–soil interface, enabling rapid alleviation of salinity stress on seedlings [42,45].

Our study demonstrates that exogenous γ-PGA application significantly enhanced the growth of maize seedlings under saline-alkaline stress conditions (Figure 3). This improvement in plant biomass was directly correlated with several key physiological adaptations observed in our maize samples. Notably, prior research has reported that exogenous γ-PGA alleviates salt stress in wheat seedlings by modulating ion balance and the antioxidant system, with similar trends of reduced Na+ accumulation and enhanced nutrient uptake-consistent with our findings in maize [21]. In field experiments where γ-PGA was applied to wheat, grain yield was 7.17% higher compared to a urea control [46]. Our results show that plant dry weight (Figure 3) and shoot TN, TP, TK, and TC contents (Figure 4) are all significantly improved by γ-PGA. While previous studies [47,48] have confirmed γ-PGA’s salt stress-alleviating effects via ion homeostasis, water retention, and soil amelioration, our work is the first to systematically link γ-PGA application to the synergistic improvement of the 5 key rhizosphere enzymes (urease, acid phosphatase, alkaline phosphatase, dehydrogenase and cellulose, involved in C, N, P cycling) and SQI in saline-alkaline soils. We would further verify this mechanism under practical surface drip irrigation, filling the research gap in γ-PGA’s regulation of rhizosphere functional enzyme networks for salt tolerance in maize. Furthermore, we found that applying γ-PGA through simulated drip irrigation could significantly improve the quality of the rhizosphere soil (Figure 2b), and, by regulating ion balance in plant tissues and the content of osmotic regulatory substances (Figure 5), it could alleviate salt and alkali stress. This has not been reported in other studies on the application of γ-PGA to date. Collectively, the improvements induced by γ-PGA, the amelioration of the soil environment, enhanced nutrient status, regulated ion homeostasis, and increased osmotic adjustment capacity work in concert to confer the observed enhanced salt tolerance in maize seedlings.

4.2. Improvement in γ-PGA on Soil Physicochemical Properties and Quality Index

Salt-affected soils typically exhibit a combination of salt stress, high pH, low SOC, and limited nutrient availability [49]. These conditions collectively reduce soil productivity and compromise crop yield [50]. Our data show that the addition of γ-PGA has a significant regulatory effect on soil pH and EC (Table 1). This effect is likely due to the γ-PGA molecular chain, rich in free carboxyl groups (-COOH), which can dissociate H+ ions into the soil solution, counteracting soil alkalinity [47]. Furthermore, γ-PGA can bind to soil carboxyl groups and chelate cations like Na+ and Cl−, thereby reducing soil electrical conductivity [48]. This may also partially explain why PGA might promote the ionic balance of plants and reduce the sodium ion content in the rhizosphere soil, alleviating salt stress.

In terms of the impact of γ-PGA treatment on rhizosphere nutrient contents, although γ-PGA has no impact on TP and TK, it significantly improved soil TN and available nutrients in our study (Table 1). Our data show that γ-PGA treatment increases the TN content in the rhizosphere soil. This promoting effect might be attributed to enhanced absorption of water by the root system, which, through mass flow, increases N transport (such as for NO3− and NH4+ ions) from the non-root-zone soil to the root zone. However, due to the limited absorption rate of the root system, some nitrogen might be accumulated in the root zone [51]. Our results show that γ-PGA significantly increased nutrient availability. γ-PGA treatment significantly increased AN, AP, and AK content in the rhizosphere soil by 6.65–13.9%, 3.09–7.70% and 14.0–22.2% (Table 1). The improvement of soil nutrient availability is closely related to enzyme activity. As urease and phosphatase directly participate in nutrient mineralization, the increase in their activity leads to enhanced N and P mineralization [52]. Dehydrogenase regulates organic matter conversion efficiency by influencing the humification process [53]. Cellulase can improve carbon-use efficiency [54]. We show that γ-PGA treatment significantly increased the activities of urease, acid phosphatase, alkaline phosphatase, dehydrogenase, and cellulose in leaves, by 35.5–39.3%, 35.4–39.3%, 5.59–8.85%, 18.9–19.8%, and 19.2–47.0%, respectively (Figure 1a,b,e,f and Figure 2a). This promoting effect might be attributed to: (1) the strong hydrophilicity of γ-PGA, which improves soil water retention [55] by providing a persistent water film that facilitates enzymatic reactions in the rhizosphere environment; (2) an adjustment in soil pH toward a more optimal range for enzyme activity through carboxyl group dissociation [56]; (3) improvement in ion balance: chelation of Na+ in soil reduces ionic strength and alleviates salt-induced inhibition of enzyme proteins [57].

The potential of the application of γ-PGA has gained rising attention due to its ability to enhance soil fertility and microbial activity [58]. With the addition of γ-PGA to the rhizosphere, SQI significantly improved (Figure 2b), although there was no significant difference among varying doses of γ-PGA, indicating that the effect of γ-PGA on soil nutrient transformation and enzyme activity might be a longer-term process rather than a transient effect, likely attributable to the fact that soils act as a complex buffering systems, possessing robust homeostasis mechanisms and resilience to disturbances [59]. Consistent with our findings, recent studies have also confirmed γ-PGA’s role in alleviating salt and osmotic stress in saline environments. Liu et al. [49] reported that γ-PGA biopreparation ameliorated coastal saline soil by reducing soil EC and improving nutrient availability, which aligns with our observations of decreased rhizospheric pH, EC and increased AN, AK contents. Ma et al. [50] further demonstrated that γ-PGA enhances maize salt resistance by enriching salt-tolerant plant-growth-promoting bacteria (PGPBs) in the rhizosphere and improving osmotic/ionic stress tolerance, supporting our conclusion that γ-PGA optimizes the rhizosphere microenvironment. Zeng et al. [60] further verified that γ-PGA synergises with plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) to enrich rhizospheric Firmicutes (e.g., Bacillus_firmus_g_Bacillus, Bacillus_selenatarsenatis) and core functional taxa, enhance microbial network connectivity, and promote the secretion of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), 1-aminocyclo-propane-1-carboxylate (ACC) deaminase, and extracellular polysaccharides. This synergy not only boosts maize’s absorption of N and P but also reduces leaf Na+ accumulation by 59.43% under high salt stress, thereby improving salt tolerance, consistent with our findings regarding rhizosphere optimization, ion balance regulation, and enhanced nutrient availability. Likely, therefore, γ-PGA could be safely applied to saline–alkali land on a long-term, continuous basis. We suggest that γ-PGA application to the rhizosphere soil can create a more beneficial rhizosphere environment, characterised by relatively low pH, low EC, high nutrient availability, as well as high enzyme activities in the saline–alkaline soil. Since the maintenance and enhancement of soil health is especially important in long-term contexts, it is necessary to study the effects of γ-PGA on soil quality indices at different spatio-temporal scales in the future, to align with common long-term management approaches such as drip-irrigation technology.

4.3. Roles of γ-PGA in Alleviating Osmotic and Ionic Stress Damage in Maize Seedlings

Application of γ-PGA significantly enhanced the growth of maize seedlings under saline-alkaline stress (Figure 3). This improvement in plant biomass can be attributed to the amelioration of soil conditions (Table 1), which in turn promoted greater nutrient accumulation in roots (Figure 4), balanced ion homeostasis, and enhanced osmotic adjustment (Figure 5).

In this study, γ-PGA significantly increased root biomass (Figure 3b), to 2.21 times that of CK, thus promoting the size and overall surface area of roots, thereby enhancing the ability to absorb nutrients (Figure 4), and, consequently, promoting shoot growth (Figure 3a). Beyond its established functions as a metabolite and nutrient [56], γ-PGA was recently observed to significantly accelerate nitrogen metabolism in Chinese cabbage [61]. When applied to soil, γ-PGA undergoes decomposition into low-molecular-weight substances, such as Glu or polypeptides, ultimately mineralising into inorganic N and C [62]. It is well-established that Glu can be absorbed by plants in its molecular form [63] and plays a pivotal role in plant C and N metabolism [64,65,66]. Research indicates that external L-Glu, across a broad concentration range (50 µM to 50 mM), can inhibit primary root growth while simultaneously promoting lateral root branching in Arabidopsis, potentially increasing root density in glutamate-rich soil patches [64,67]. Consequently, the increased plant root biomass observed under γ-PGA treatment (Figure 3b) might be directly attributed to the degradation products of L-Glu in the soil. Although these growth-promoting effects should be experimentally validated. Future studies are crucial to elucidate how γ-PGA precisely affects root growth and whether its impact mirrors that of L-Glu.

Furthermore, excessive Na+ accumulation constitutes another major growth threat under salt stress. This excess Na+ disrupts membrane selectivity for crucial nutrient uptake (e.g., K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+), leading to mineral homeostasis disruption and subsequent ionic toxicity [68,69]. The protective role of K+, in particular, under conditions of salinity and other ionic and osmotic stresses, is well established [70,71]. Our study shows that γ-PGA treatment significantly reduces Na+ levels in corn seedlings (Figure 5a), while increasing K+ levels (Figure 5b), hereby lowering tissue Na+/K+ ratio (Figure 5c). The increase in K+ in the shoot of the maize seedlings may be attributed to the enhanced availability of soil AK in the rhizosphere due to γ-PGA application (Table 1). Furthermore, the effective regulation of ionic balance by γ-PGA likely constitutes the primary mechanism underlying the improved salt tolerance observed in maize seedlings. Under salt stress, plants typically accumulate osmolytes, such as proline, proteins, and soluble carbohydrates, to counteract osmotic imbalance [72]. C and N metabolism of maize seedling were both clearly affected by γ-PGA, as evidenced by elevated soluble sugar (Figure 5d) and free amino acid contents (Figure 5e) in plants grown with γ-PGA amendment. These findings are consistent with previous studies which found that other biological stimulants and salt-stress mitigators such as melatonin can significantly increase the content of soluble protein and free amino acids in maize seedling leaves [72]. Under salt stress, γ-PGA improves ion balance and the accumulation of osmotic products in maize seedlings, key mechanisms in maize adaptation and tolerance under salt stress. Expect of ion balance and osmotic regulation, regulation of antioxidant system (superoxide dismutase, catalase, peroxidase activities), as well as oxidative stress indicators (malondialdehyde, hydrogen peroxide) are both important plant-physiological regulations for alleviation of salt damage stress. Subsequently, a control without salinity treatments should be incorporated to distinguish and elucidate the underlying mechanisms by which γ-PGA supplementation alleviates maize salt stress, rather than merely promoting growth, which would help distinguish general growth promotion from salt-specific effects. These indicators would be investigated in the subsequent research to provide more information of the comprehensive mechanism.

4.4. Potential Physiological Mechanisms of γ-PGA in Regulating Maize Salt Tolerance

As a water-soluble, biodegradable biopolymer acting primarily via rhizosphere contact, γ-PGA is inferred to enhance maize salt tolerance through rhizosphere-centered regulatory effects. It can be degraded into glutamic acid and small peptides in the rhizosphere [62], which may act as signals to promote lateral root and root hair development [64,67]. This root morphological optimization improves water/nutrient absorption, synergising with enhanced rhizosphere nutrient availability (our key observation, Table 1) to alleviate nutrient deficiency in salt soil. Additionally, γ-PGA’s rhizosphere-modulating effects (e.g., reduced salinity) may indirectly regulate membrane transporters (e.g., Na+/H+ antiporters) [68,69] to maintain ionic homeostasis (lower shoot Na+/K+ ratio, our observation, Figure 5c). It may also promote osmoprotectants accumulation and coordinate antioxidant enzyme (e.g., SOD, CAT) activity to mitigate salt-induced oxidative damage [21,50]. Existing biostimulant research also suggests γ-PGA may regulate auxin/abscisic acid signaling in a dose-dependent manner to modulate stress tolerance, though excessive concentrations may disrupt hormone balance [20]. These mechanisms are inferred from γ-PGA’s rhizosphere-localized action, existing literature, and the deduction from our observations; precise pathways await future targeted validation.

5. Conclusions

This study revealed that root-zone application of γ-PGA with an optimal content of 12 kg ha−1 (100% w/w) effectively mitigates salt stress, and significantly promotes the growth and nutrient accumulations of maize seedling. γ-PGA treatment creates a more favourable rhizosphere environment by significantly decreasing soil pH and EC, increasing the availabilities of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, increasing the activities of urease, acid phosphatase, alkaline phosphatase, dehydrogenase, and cellulose, as well as improving the rhizosphere soil quality index. Furthermore, the addition of γ-PGA significantly reduced the Na+/K+ ratio in maize shoots, while maintaining ion balance and promoting the osmotic regulation of soluble sugars and soluble proteins. The effect of γ-PGA on soil nutrient transformation and enzyme activity is persistent within the experimental timeframe, rather than transient. However, its long-term effect in saline–alkaline soils remains to be further verified through extended field trials. Therefore, rhizosphere application of γ-PGA presents a promising and practical strategy for enhancing crop production in saline–alkali lands on an ongoing basis, particularly when integrated with methodologies such as drip irrigation.

Author Contributions

X.L. Writing—original draft and editing, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Y.L. Writing—review and editing, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. X.D. Writing—review and editing, Investigation. W.S. Writing—review and editing, Validation, Supervision. H.J.K. Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely acknowledge the contributions of the Institute of Western Agricultural, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences for their financial support. We thank the anonymous reviewers and the editors for their suggestions, which substantially improved the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Chen, L.; Zhou, G.; Feng, B.; Wang, C.; Luo, Y.; Li, F.; Shen, C.; Ma, D.H.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J. Saline-alkali land reclamation boosts topsoil carbon storage by preferentially accumulating plant-derived carbon. Sci. Bull. 2024, 69, 2948–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanin, M.; Ebel, C.; Ngom, M.; Laplaze, L.; Masmoudi, K. New Insights on Plant Salt Tolerance Mechanisms and Their Potential Use for Breeding. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javed, S.; Shahzad, S.; Ashraf, M.; Kausar, R.; Arif, M.; Albasher, G.; Rizwana, H.; Shakoor, A. Interactive effect of different salinity sources and their formulations on plant growth, ionic homeostasis and seed quality of maize. Chemosphere 2022, 291, 132678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Guo, Y. Unraveling salt stress signaling in plants. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2018, 60, 796–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, E.; Hoffman, G.; Chaba, G.; Poss, A.; Shannon, M. Salt sensitivity of corn at various growth stages. Irrig. Sci. 1983, 4, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Li, R.; Dong, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, B.; Ren, H.; Yao, H.; Wang, Z.; Liu, P. Maize (Zea mays L.) responses to salt stress in terms of root anatomy, respiration and antioxidative enzyme activity. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Xue, R. Effect of Alternate Sprinkler Irrigation with Saline and Fresh Water on Soil Water–Salt Transport and Corn Growth. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Bai, T.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Ci, J.; Ren, X.; Zang, Z.; Ma, C.; Xiong, R.; Song, X.; et al. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Salt Tolerance in Maize: A Combined Transcriptome and Metabolome Analysis. Plants 2025, 14, 2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maimaiti, A.; Gu, W.; Yu, D.; Guan, Y.; Qu, J.; Qin, T.; Wang, H.; Ren, J.; Zheng, H.; Wu, P. Dynamic molecular regulation of salt stress responses in maize (Zea mays L.) seedlings. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1535943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alletto, L.; Cueff, S.; Bréchemier, J.; Lachaussée, M.; Derrouch, D.; Page, A.; Gleizes, B.; Perrin, P.; Bustillo, V. Physical properties of soils under conservation agriculture: A multi-site experiment on five soil types in south-western France. Geoderma 2022, 428, 116228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhou, W. Drip irrigation in agricultural saline-alkali land controls soil salinity and improves crop yield: Evidence from a global meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 880, 163226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Liu, X.; Song, S.; Lu, W.; Yang, X.; Ma, Y.; Yang, Y. Regulation of ion homeostasis for salinity tolerance in plants. Plant Physiol. 2022, 59, 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvin, K.; Nahar, K.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Bhuyan, M.; Mohsin, S.; Fujita, M. Exogenous vanillic acid enhances salt tolerance of tomato: Insight into plant antioxidant defense and glyoxalase systems. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 150, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coskun, D.; Britto, D.; Jean, Y.; Kabir, I.; Tolay, I.; Torun, A.; Kronzucker, H. K+ efflux and retention in response to NaCl stress do not predict salt tolerance in contrasting genotypes of rice (Oryza sativa L.). PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e57767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, I.; Van, Y. The production of poly- (γ-glutamic acid) from microorganisms and its various applications. Bioresour. Technol. 2001, 79, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, X.; Gao, D.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Wei, Z.; Shi, Y. Effects of poly-γ-glutamic acid (γ-PGA) on plant growth and its distribution in a controlled plant-soil system. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, T.; Huang, Y.; Xie, X.; Huo, X.; Shahid, M.; Tian, L.; Lan, T.; Jin, J. Rice SST Variation Shapes the Rhizosphere Bacterial Community, Conferring Tolerance to Salt Stress through Regulating Soil Metabolites. mSystems 2020, 5, 00721-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Ye, J.; Yin, L.; Li, G.; Deng, X.; Wang, S. Exogenous Melatonin Improves Salt Tolerance by Mitigating Osmotic, Ion, and Oxidative Stresses in Maize Seedlings. Agronomy 2020, 10, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, N.; Zhang, H.; Li, S.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, J.; Sun, L.; Lv, W. Effects of application rates of poly-γ-glutamic acid on vegetable growth and soil bacterial community structure. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2020, 147, 103405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moenne, A.; González, A. Chitosan-, alginate- carrageenan-derived oligosaccharides stimulate defense against biotic and abiotic stresses, and growth in plants: A historical perspective. Carbohydr. Res. 2021, 503, 108298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Yang, N.; Zhu, C.; Gan, L. Exogenously applied poly-γ-glutamic acid alleviates salt stress in wheat seedlings by modulating ion balance and the antioxidant system. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 6592–6598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singhal, R.; Saha, D.; Skalicky, M.; Mishra, U.; Chauhan, J.; Behera, L.; Lenka, D.; Chand, S.; Kumar, V.; Dey, P.; et al. Crucial Cell Signaling Compounds Crosstalk and Integrative Multi-Omics Techniques for Salinity Stress Tolerance in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 670369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, M.; Sagar, A.; Mia, M.; Tania, S. Mitigation of Salinity-Induced Growth Inhibition of Maize by Seed Priming and Exogenous Application of Salicylic Acid. J. Agric. Ecol. Res. Int. 2023, 24, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xie, W.; Yang, J.; Yao, R.; Wang, X.; Li, W. Effect of Different Fertilization Measures on Soil Salinity and Nutrients in Salt-Affected Soils. Water 2023, 15, 3274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, B.; Shi, W.; Wang, Y. Poly-γ-glutamic acid enhanced the yield and photosynthesis of soybeans by adjusting soil aggregates and water distribution. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024, 104, 6884–6892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; He, Q.; Zhou, G. Sequence of Changes in Maize Responding to Soil Water Deficit and Related Critical Thresholds. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Zhang, P.; Xu, J.; Liu, B.; Zhang, L.; Du, X.; Bai, J. Rapid determination of soil cation exchange capacity using a cation exchange capacity pretreatment system and a Kjeldahl apparatus. Geophys. Geochem. Explor. 2023, 47, 458–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkley, A. An Examination of Methods for Determining Organic Carbon and Nitrogen in Soils. J. Agric. Sci. 1935, 25, 598–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, D.; Yan, X.; Jia, L.; Chen, N.; Liu, J.; Zhao, P.; Zhou, L.; Cao, Q. Effect of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium ferti-lization management on soil properties and leaf traits and yield of Sapindus mukorossi. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1300683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulvaney, R.; Khan, S. Diffusion Methods to Determine Different Forms of Nitrogen in Soil Hydrolysates. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2001, 65, 1284–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S. Estimation of Available Phosphorus in Soils by Extraction with Sodium Bicarbonate; U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Wolinska, A.; Stepniewsk, Z. Dehydrogenase Activity in the Soil Environment. In Dehydrogenases; InTech: Houston, TX, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabatabai, M.; Bremner, J. Assay of urease activity in soils. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 1972, 4, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.; Blum, R.; Glennon, W.; Burton, A. Measurement of carboxymethyl cellulase activity. Anal. Biochem. 1960, 1, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzyakov, Y.; Gunina, A.; Zamanian, K.; Tian, J.; Luo, Y.; Xu, X.; Yudina, A.; Aponte, H.; Alharbi, H.; Ovsepyan, L.; et al. New approaches for evaluation of soil health, sensitivity and resistance to degradation. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 2020, 7, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Li, P.; Gong, S.; Yang, L.; Wen, L.; Hou, M. Defense Responses in Rice Induced by Silicon Amendment against Infestation by the Leaf Folder Cnaphalocrocis medinalis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, D.; Sommers, L.E. Determination of total nitrogen in soils by an improved automated Dumas method. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 1980, 11, 1097–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golijan Pantović, J.; Vasić, V.; Jevtić, M.; Kostić, A. Determination of P, K and Mg content in maize seed subjected to the accelerating ageing test. J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2022, 23, 1123–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.S. Experimental Principle and Technology of Plant Physiology and Biochemistry; Higher Education Press: Beijing, China, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Batlle-Sales, J. Salt-affected soils: A sustainability challenge in a changing world. Ital. J. Agron. 2023, 18, 2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K. Microbial and Enzyme Activities of Saline and Sodic Soils. Land Degrad. Dev. 2015, 27, 706–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Sun, H.; Guo, H.; Song, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ruan, Y.; Xu, Q.; Huang, Q.; Shen, Q.; et al. Synthetic community derived from grafted watermelon rhizosphere provides protection for ungrafted watermelon against Fusarium oxysporum via microbial synergistic effects. Microbiome 2024, 12, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunita, K.; Mishra, I.; Mishra, J.; Prakash, J.; Arora, N. Secondary Metabolites From Halotolerant Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria for Ameliorating Salinity Stress in Plants. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 567768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Li, Y.; Zhang, N.; Wu, Y.; Ou, X. Poly-glutamic acid mitigates the negative effects of salt stress on wheat seedlings by regulating the photosynthetic performance, water physiology, antioxidant metabolism and ion homeostasis. Plant Soil Environ. 2024, 70, 454–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Wan, C.; Xu, X.; Feng, X.; Xu, H. Effect of poly (γ-glutamic acid) on wheat productivity, nitrogen use efficiency and soil microbes. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2013, 13, 744–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Chen, L.; Hamoud, Y.; Zheng, J.; Chang, T.; Ali, J.; Huang, H.; Shaghaleh, H. Ameliorative effect of poly-γ-glutamic acid biopreparation on coastal saline soil. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Xiao, N.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, P.; Deng, X.; Wei, J.; Li, P.; Xia, T. Poly-γ-glutamic acid could enhance the salt resistance of maize by collectively increasing the osmotic, ion, and oxidative stresses resistance and enriching the salt-tolerant PGPBs in rhizosphere soil. Plant Soil 2025, 515, 1179–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Shao, G.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, K.; Lu, J.; Wang, Z.; Wu, S.; Xu, D. Influences of soil and biochar properties and amount of biochar and fertilizer on the performance of biochar in improving plant photosynthetic rate: A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Agron. 2021, 130, 126345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Li, Y.; Guan, X.; Ma, S.; Cui, H.; Liu, L.; Li, Y. The impact of salt-tolerant plants on soil nutrients and microbial communities in soda saline-alkali lands of the Songnen plain. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1592834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Moral Torres, F.; Hernández Maqueda, R.; Meca Abad, D. Enhancing Root Distribution, Nitrogen, and Water Use Efficiency in Greenhouse Tomato Crops Using Nanobubbles. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K. Biochar Amendments for Soil Restoration: Impacts on Nutrient Dynamics and Microbial Activity. Environments 2025, 12, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, K.; Goraj, W.; Kuźniar, A.; Kruczyńska, A.; Sochaczewska, A.; Słomczewski, A.; Wolińska, A. Exploring the Synergy between Humic Acid Substances, Dehydrogenase Activity and Soil Fertility. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.; Morais, M.; Mandelli, F.; Lima, E.; Miyamoto, R.; Higasi, P.; Araujo, E.; Paixão, D.; Júnior, J.; Motta, M.; et al. A metagenomic ‘dark matter’ enzyme catalyses oxidative cellulose conversion. Nature 2025, 639, 1076–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bijanzadeh, E.; Naderi, R.; Egan, T. Exogenous application of humic acid and salicylic acid to alleviate seedling drought stress in two corn (Zea mays L.) hybrids. J. Plant Nutr. 2019, 42, 1483–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staunton, S.; Pistocchi, C. Isotopic exchangeability reveals that soil phosphate is mobilised by carboxylate anions, whereas acidification had the reverse effect. Soil 2025, 11, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Xu, H.; Zhang, D.; Feng, S. Chelation and nanoparticle delivery of monomeric dopamine to increase plant salt stress resistance. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, S.; Ge, F.; Xu, Y.; Sun, Q.; Xie, F.; Ren, Y.; Du, J.; Chu, C.; Xu, B.; Li, W. Effects of γ-PGA application on soil physical and chemical properties, rhizosphere microbial community structure and metabolic function of urban abandoned land. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1534505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Li, G.; Wang, S.; Dai, Z. Effect of sesame cake fertilizer with γ-PGA on soil nutrient, water and nitrogen use efficiency. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Hou, Y.; Ao, C.; Huang, J. Effects of PGPR and γ-PGA on maize growth and rhizosphere microbial community in saline soil. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 295, 108736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Lei, P.; Feng, X.; Xu, X.; Liang, J.; Chi, B.; Xu, H. Calcium involved in the poly (γ-glutamic acid)-mediated promotion of Chinese cabbage nitrogen metabolism. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 80, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Dong, G.; Zhang, C.; Ren, Y.; Qu, Y.; Chen, W. Calcium regulates glutamate dehydrogenase and poly-γ-glutamic acid synthesis in Bacillus natto. Biotechnol. Lett. 2015, 38, 673–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipson, D.; Raab, T.; Schmidt, S.; Monson, R. Variation in competitive abilities of plants and microbes for specific amino acid. Biol. Fert. Soils 1999, 29, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, P.; Miflin, B. Glutamate synthase and the synthesis of glutamate in plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2003, 41, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, V.; Ajami, A. Glutamate: An Amino Acid of Particular Distinction. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 892S–900S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glass, A.; Britto, D.; Kaiser, B.; Kinghorn, J.; Kronzucker, H.; Kumar, A.; Okamoto, M.; Rawat, S.; Siddiqi, M.; Unkles, S.; et al. The regulation of nitrate and ammonium transport systems in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Liu, L.; Remans, T.; Tester, M.; Forde, B. Evidence that l -Glutamate Can Act as an Exogenous Signal to Modulate Root Growth and Branching in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2006, 47, 1045–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronzucker, H.; Coskun, D.; Schulze, L.; Wong, J.; Britto, D. Sodium as nutrient and toxicant. Plant Soil 2013, 369, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronzucker, H.; Britto, D. Sodium transport in plants: A critical review. New Phytol. 2011, 189, 54–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczerba, W.; Britto, D.; Kronzucker, H. K+ transport in plants: Physiology and molecular biology. J. Plant Physiol. 2009, 166, 447–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britto, D.; Coskun, D.; Kronzucker, H. Potassium physiology from Archean to Holocene: A higher-plant perspective. J. Plant Physiol. 2021, 262, 153432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wang, J.; Shi, S.; Huang, L.; Zhu, M.; Li, F. Exogenous melatonin ameliorates salinity-induced oxidative stress and improves photosynthetic capacity in sweet corn seedlings. Photosynthetica 2021, 59, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.